Abstract

Introduction

This research has considered current developments in the provision of services for people with long-term conditions within the NHS of England. Community Matrons are being employed and by adopting a case management approach they are aiming to improve patient care and reduce their demands for acute hospital care.

Description

Qualitative research was undertaken to explore experiences of community matrons and service leads on the development, implementation and provision of services for people with long-term conditions.

Conclusions

This research provides evidence of what is being done to meet the challenge of long-term conditions and provides lessons for similar challenges and service development for different areas of care and in other countries. Continual system and role change has had effects on service delivery and on the whole care. These effects relate to; defining the role of community matron and structure of service, training staff, identifying patients, providing infrastructure, demonstrating benefits, identifying gaps in services, ability to reduce avoidable admissions and identifying the advantages and difficulties of the role.

Discussion

All of these aspects should be used to inform future development.

Keywords: service development, case management, community matrons, innovation forum, long-term conditions

Introduction

In common with its counterparts in other Western nations, England is facing a rise in the proportion of its population who are elderly. It has been estimated that by 2026, 20% of its population will be aged 65 or over and between 1995 and 2025 the number aged over 80 will increase by 50% and over 90 by 100% [1, 2]. Such a demographic switch has implications for the National Health Service (NHS, see Box 1) of England and the government’s policy response is to promote an increase in services that prevent or delay a person’s need for acute hospital care by increasing the range of services available for providing care in the community [3, 4].

Box 1.

| The English National Health Service was created in 1948 and is committed to providing good healthcare available to all. The National Health Service is publicly funded and as such is politically accountable to the United Kingdom Government in England. The United Kingdom Government department responsible for the National Health Service is the Department of Health which is headed by the Secretary of State. The National Health Service Website gives more details on the three core principles that guide the service; |

| 1. that it meet the needs of everyone, |

| 2. that it be free at the point of delivery, and |

| 3. that it be based on clinical need, not ability to pay. |

| The Department of Health controls 10 Strategic Health Authorities in England which are responsible for implementing national policy and directives in their region and the strategic supervision of services. Services are commissioned at a local level by organisations such as Primary Care Trusts, NHS Hospital Trusts and NHS Care Trusts. Most funds are held by the Primary Care Trusts who commission services such as General Practise, Optometry, Dentistry and Hospitals. |

The Department of Health report “Supporting people with long-term conditions: liberating the talents of nurses who care for people with long-term conditions” [5] focuses on the patient with the most complex needs. The report states that patients with highly complex or long-term needs often have reactive, uncoordinated care punctuated by frequent unplanned admissions to hospital. In addition, a small percentage of individuals with chronic conditions are highly intensive users of acute services; 10% of inpatients admitted with a long-term condition account for 55% of inpatient days and 5% for 40% of inpatient days [6, 7]. Patients may receive care in response to a crisis or untoward event but have little preventative intervention in-between. Issues can also arise when many professionals are involved in care but no one person has overall responsibility for considering all of their health and social care needs and ensuring that these needs are met. This may involve coordinating equipment and resources needed to care for patients at home, prescribing medicines, meeting social care needs and specialist care.

In keeping with its aim of switching the focus of care from acute hospital to community based sources, the Department of Health’s response to such concerns has been to encourage health care providers to redesign their services for managing long-term conditions and to employ Community Matrons [8]. The aim is that by adopting a case management approach, Community Matrons will allow more patients with complex needs to remain at home longer for their care.

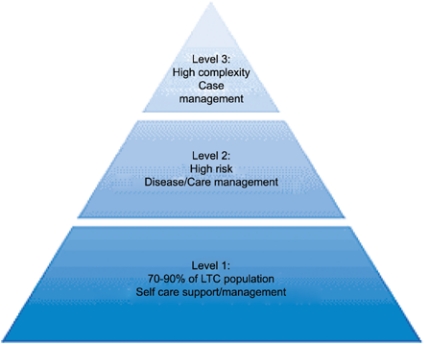

The revised approach to managing patients with long-term conditions in England is based upon the US model of Evercare [9, 10]. The model used in NHS policy documents to ‘classify’ patients with long-term conditions according to their needs is shown in Figure 1. Level 1 includes 70–80% of the long-term conditions population that can be supported through self care and play an active role in managing their conditions. Level 2 is the population at high risk who may require disease care management from multidisciplinary teams. The highest level of complexity is level 3: this is the target group for case management care by Community Matrons.

Figure 1.

The NHS and Social Care Long-Term Conditions Model [8].

NHS Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) are responsible for recruiting Community Matrons. However, in implementing the revised approach to care, PCTs must work in collaboration with their Local Authority partners, given the complex nature of care required by patients with long-term conditions. In England, Local Authorities are responsible for delivering services for social care.

The research described in this paper investigated the implementation of the Community Matron model of care in one such health and social care partnership in North West England. Key challenges that they needed to address in implementing this model of care were:

Defining the case management role;

Involving users in service redesign;

Identifying and involving key stakeholders;

Redesigning the wider workforce to encompass the community matron role;

Increasing skills of the workforce;

Identifying and preparing supervisors and clinical mentors;

Establishing systems to support case management by community matrons.

Background

The health and social care partnership of agencies covered by this research is a member of the Innovation Forum. The Innovation Forum is an initiative supported by the English Department of Health and Office of the Deputy Prime Minister and it represents a collaboration of nine Local Authorities and their primary care and acute trust health partners [11]. Each of the nine Innovation Forum ‘sites’ had the aim of improving services and bringing about a 20% reduction in the unscheduled use of acute beds by older people (aged over 75) through a range of service developments. In the setting for this research, these developments included services for managing long-term conditions, services for preventing falls, for reducing delays in transfers from acute hospital based care, and providing a Single Point of Access to hospital emergency services.

The local Innovation Forum partners provided funds for a two-year programme of applied research to support service development and independent evaluation. This aspect of the research considered service developments for long-term conditions and their evaluation.

Problem Statement

The research investigated the development and implementation of case management for people with long-term conditions by community matrons within one of the national Innovation Forum pilot sites in the UK. When the research commenced the site included one Local Authority and three PCTs but due to mergers the number of participating PCTs had reduced to two by the end of the research. However, the geographic coverage of the research setting remained constant throughout.

Theory and methods

The objectives of the research were:

To identify and describe the structure of services and issues faced in their development;

To gather information on the strengths, gaps, overlaps and opportunities of service provision, and the educational preparation of community matrons;

To identify future developments for the provision of services for people with long-term conditions.

Qualitative research was undertaken to explore experiences of the development, implementation and provision of services for people with long-term conditions by Primary Care Trusts. An iterative approach was used involving qualitative semi-structured interviews of key stakeholders and providers, including community matrons (during the early stages of the initiative and around one year later), documentary analysis, clinical data analysis and two action learning events at the beginning of the project in year 1 and at the end of the project, year 2. Participants were invited to raise and update issues on development, operation and provision of services for people with long-term conditions from their own perspectives so that the interviews covered what they deemed to be important.

Convenience samples of staff were involved in the initial and follow-up semi-structured interviews, and comprised community matrons who participated in group interviews and key stakeholders who were managers or service/project leads responsible for the development, implementation and provision of services for people with long-term conditions by community matrons across the area. The managers and project leads were approached first and provided with information about the research and asked whether they would be willing to participate. Once they were interviewed they ensured access to the community matrons.

Documents pertaining to the services were provided by each stakeholder and field notes were recorded to supplement the interviews. Semi-structured taped group interviews were undertaken with the community matrons at a time and location that was convenient for them and with their permission. The interviews obtained the key information listed below, and captured local factors allowing comparison across the area and lessons to be shared for future developments.

Information was collected during the interviews on subjects such as:

Biography, professional background, previous practice history, experience, and qualifications in order to ascertain how community matrons were being prepared to work in the role and how they had come to the role;

Education and professional training, time and methods. This indicated how the workforce was being developed and trained to take on the role;

Views on the 57 competencies for Long Term Conditions Case Management [12] to see how these were being gained alongside the role and its development and to ascertain how supervisors and clinical mentors were being identified and prepared to support the training needs of the matrons;

Community Matron role, experience and expectations and difference between these, difficulties, strengths and opportunities, collaboration and awareness by others. This indicated how the wider workforce was being redesigned to encompass the community matron role and how key stakeholders were being identified and involved in development;

Case management and the needs of the patients, service gaps. This information was gathered to indicate how the case management role was being defined and its evolution and how systems and infrastructure were being established to support case management by community matrons;

Identifying patients for casework, criteria and referrals, data and information on initial caseload and ongoing assessment. This was in order to show how the population at risk were being identified, also how outcomes/success and patient and carer satisfaction were being measured and users were being involved in service redesign.

All initial interviews were conducted at an early stage of development of the service over a period of seven months, from January to July 2006. Follow-up interviews were conducted from March to July 2007 and revisited the above topics and established how aspects had changed since the initial interviews. A full suite of questions used in the interviews is available from the lead author. Ideas for establishing routine evaluation and audit of patients and carers experiences of care, satisfaction and suggestions for development or improvement of services as part of usual care were shared at the end of the interviews and during the Action Learning Events (see below).

Interviews were transcribed and analysed using content analysis and themes identified. Documentary evidence, field notes of meetings and service lead interviews were also analysed and supplemented the interview data to provide a descriptive context for structures, processes and outcomes of services and clients with long-term conditions. The validity of the themes was assured during the interviews by verifying data with participants, checking the lines of enquiry used where appropriate and questions were fully explored. A reliability check was undertaken across the themes generated from the content analysis by two members of the research team and theme headings were agreed by consensus and discussion.

The two action learning events were arranged by the sponsor and held at the beginning of data collection in year 1 (January 2006) and at the end of the project in July 2007 [13]. Participants comprised a convenience sample of health and social care providers and managers representing key organisations including social services, acute and primary care trusts and voluntary organisations.

Results

Interviews were conducted with the following numbers of community matrons:

Primary Care Trust 1; initial n=11, follow-up n=7; Primary Care Trust 2; initial n=3, follow-up n=11.

The numbers of interviews with service leads were—initial n=4, follow-up n=3.

Numbers of participants at the Action Learning Events were—Event 1 n=15; Event 2 n=20.

The findings of this work provide key lessons for service development and integrated care, not just in long-term conditions but also other areas of care. Frequent changes to the system the matrons work in and changes in the function of the role had an effect on how the service was delivered. Implications of these changes for the ‘whole system’ related to; defining role and structure of service, training staff, identifying patients, providing infrastructure, demonstrating benefits, identifying gaps in services, ability to reduce avoidable hospital admissions and identifying advantages and difficulties of the role. Individual aspects are considered below.

Defining role and structure of service

The appointment of community matrons was part of local developments for supporting people with long-term conditions as part of the Innovation Forum initiative and in keeping with government policy. The matrons were predominantly appointed internally from community nursing within the Primary Care Trusts; they comprised mainly district nurses and practice nurses. Importantly no additional sources of funding were available to backfill vacancies within district nursing services causing extra pressures on the system. It was also proposed to recruit professionals allied to medicine as community matrons in future. Both Primary Care Trusts had recruitment targets of approximately 15 Whole Time Equivalent community matrons by March 2007 but these targets had not been met due to difficulties faced in recruitment and retention which were issues often highlighted in interview. There were concerns raised about stress related illness and absence, thought to be due to the pressures of the role. There were changes in staffing at all levels from baseline to follow-up. The appointments were part of pilots and were for the short term in the first instance, which did not aid this situation.

Many matrons felt they were working in short staffed conditions and were covering others matron’s patients due to short staffing and sickness. Plans were in place to increase the number of community matrons and collect evidence on the effectiveness of their role to support recruitment. The matrons felt they were losing the ability to be able to review, monitor and follow-up patients due to being short staffed. This had resulted in a reduction in their regular contacts with patients as they had to respond to crises rather than proactive care. They thought this made them less able to support people at home, keep clients out of hospital or enable people to be discharged early.

Training staff

Matrons were highly experienced which was crucial in their new role. The community matrons were required to achieve 57 competencies, which included some skills they had previously achieved [12]. Formal training on the competencies was being undertaken through university courses. Their knowledge, learning and experience were being shared across their local teams and larger networks with whom they regularly met. Some elements of the training were felt to be a duplication of that completed before and previous experience and no prior accreditation was allowed.

“…well for me you feel completely out of your comfort zone, everything that you, you feel like a student nurse again in lots of ways, because there is so much to learn and like I say, you feel like you need to know it all, right now and that’s quite hard.”

Identifying and accessing mentors for training and development needs was on a good will basis only, which caused difficulties but mentorship was thought to be an important part of the training.

A key area of support has been regular meetings and contact between the matrons themselves. The community matrons in Primary Care Trust 1 comprise one team across the Trust and meet monthly. Attendance at the meeting is however, a challenge due to staff shortage and clients’ needs taking priority. Network and team meetings are important for sharing experience and knowledge and to prevent matrons feeling isolated while they are developing the new role. Mentorship was viewed as important as was the opportunity to meet, share knowledge and learn about clients with complex cases. At the follow-up, the previously useful network meetings had ceased due to work pressures. These meetings were thought to be useful not only clinically but also provided an overview and update on strategy.

At follow-up the matrons reported that the initial challenges of balancing identifying caseload and completing training had changed to balancing their case loads, and developing their service.

Identifying patients

The information and data needed to accurately identify possible patients for caseload was difficult to obtain and keep up to date. Matrons were resisting pressure to increase numbers on an average caseload as they felt this would defeat the purpose of the role.

Variable inclusion criteria for caseloads existed across Primary Care Trusts highlighting the need to share experience and learning as service evolves.

The role of community matrons was evolving across the area and the inclusion criteria for clients seen in each area varied slightly according to their long-term conditions. There were criteria in place used in order to identify those at risk; these were often used in conjunction with personal knowledge of practice nurses and GPs.

“Well you can’t rely on one individual way of doing it we find because you’re not getting the whole picture. We are having to look wider really and look at surgery data as well as the stuff you get from the Primary Care Trust.”

These criteria were better established across the cohort at the time of the follow-up interviews and were being formally used in Primary Care Trust 1 (see Table 1). All cohorts were in the process of refining their caseloads and some groups were using the Kings’ Fund Patients at Risk of Readmission (PARR) data and its later version of Patients at Risk of Readmission 2 [14–16]. Referrals to the service were being prioritised according to the needs of the patients.

Table 1.

Criteria for caseload (Primary Care Trust 1)

| • Over 18 years of age |

| • 2 or more unplanned admissions in last 12 months |

| • 2 or more long term conditions or other health problems |

| • Poly pharmacy (4 or more medications as per National Service Framework 2001) [1] |

| • 4–5 consultations with General Practitioner in last 6 months regarding long term conditions |

| • Other risk factors that health or social care practitioners may be concerned about i.e. death of carer |

| NB. 3 or 4 of the above should trigger an assessment for case management |

| Other areas for consideration |

| • 2 or more Accident & Emergency attendances in previous 6 months |

| • Significant impairment of 1 or more Activity of Daily Living |

| • Patients whose hospital admission exceeds 1 month |

| • Patients with high intensity care packages |

| • More than 2 falls in previous 2 months |

| • Recent exacerbation or deterioration in previous 3 months |

| • Cognitively impaired and living alone |

| Exclusion criteria |

| • Patients with acute mental health problems |

| • Patients who refuse the service |

| • Primary cause of referral is alcohol problem |

| • Needs already adequately met by case management by other professional |

Generally those clients with complex needs who were frequently seen by General Practitioners or admitted to hospital, were judged as level 3 and requiring case management were eligible to be seen by community matrons. Matrons were reviewing who should be in their caseloads, those currently at a 50% Patients At Risk of Readmission (PARR) score were included but there was the question of whether to broaden this to those at 60 or 70% PARR as well. Matrons and service leads acknowledged that they were learning as the role and services evolved and that experiences and learning could be shared with the cohort and more widely. The Action Learning Events had assisted with this.

An important aspect of the role was considered the rapport and relationships built up with clients and carers. Matrons felt they provided a first point of call for clients. This meant appropriate care could be delivered rapidly and the needs of clients met appropriately. Matrons felt that their interventions could prevent inappropriate visits to General Practitioners or Accident and Emergency departments. Matrons felt that as the role became more established possible admissions to hospital could be prevented thus supporting the targets of the Innovation Forum.

Providing infrastructure

A further challenge the matrons considered they faced was the lack of infrastructure to support their role. They cited a need for a budget and resources to help shift the emphasis from the acute to the non-acute sector and support the new way of working.

Both matrons and service leads in the follow-up interviews expressed the need for organisational and systematic support that was currently lacking. In the wider health community, community matrons felt they were perceived as a ‘quick fix’, a ‘miracle service’ or ‘the golden bullet’, expected to be ‘all singing’ and ‘all dancing’ with no resources and few matrons in post. The initial expectations that other professionals had of community matrons were thought to be unrealistic which made initial service development difficult. Other professionals had different ideas of what the matrons were there to do. The matrons, despite being experienced nurses, were undertaking new training and acquiring skills while in post. Some thought they would provide extra support in the practice setting and doing jobs such as taking blood samples. Others thought that they were ‘the bosses of the district nurses’. This is changing as their impacts and outcomes for patients become evident and levels of trust are increasing. Matrons and other professionals were becoming more aware of their role as the service developed and they were more able to demonstrate their impact and convey what they were doing with the role to other professionals. The impacts and outcomes for patients became more evident and levels of trust with other professionals increased.

“I think maybe 12 months down the line when we have all fulfilled our university commitments and we have done the clinical assessments and you know we have got our feet under the table more, and we are sort of more in tune with dealing with the clinical aspects of our role more and we have got the education and knowledge behind that we will probably be feeling more comfortable than we do now.”

Matrons thought that there was no infrastructure in place and that a whole system approach for case management of people with long-term conditions did not exist which prevented them from transferring their clients to other services or providers.

“We will be prevented from preventing admissions because the infrastructure isn’t there.”

The matrons were working at capacity and needed to be able to move clients from level 3 of the above diagram to level 2 (see Figure 1). Matrons were aware of the requirement for other providers to take over when their client’s needs changed and ‘step down’ care would be suitable. Care pathways formation and signposting could assist with this.

“…working with patients is fabulous, and we actually feel we are making huge inroads and we have had some very, very positive comments haven’t we?... from carers and the patients, I think like anything new a lot of the red tape that surrounds it is the hard part and getting yourself known and accepted and I think we have all come from posts where we were well known and trusted and to find yourself in a position where you have to, to build up this reputation.”

“…I was working at quite a high level of autonomy so when I have come out of practice its been very restricted in some areas, I was used to doing a lot more prescribing than currently doing and ordering tests and medications, following quite a lot of work up, as I say its building up these relationships with other people and they then understand the levels that you can work at”.

The other elements of infrastructure matrons judged as requiring development were both information sharing and administrative support. They cited difficulties in gathering information about patients on their caseload, accessing data systems where data were held and having to duplicate the recording of patient information because of the use of paper systems of recording. Capturing data on patient satisfaction with services and outcomes was not routinely collated which has implications for demonstrating benefit to others.

Demonstrating benefits

It was viewed by matrons that caseloads were appropriate and clients seen were benefiting from the service but little or no standardised information was routinely recorded on patient satisfaction and outcomes or carers experiences of the service. Efforts were made to suggest and put in place outcome measures that the matrons could undertake during practice but these were not adopted during the research. This was due to the ongoing pressures the matrons were facing which limited their capacity to take on anything new and monitor their outcomes routinely. This represented a large gap in their data and limited their ability to demonstrate the differences that were being made for patients.

Identifying gaps in services

Provision of services and meeting the needs of elderly mentally ill patients, with dementia or depression, the elderly in nursing homes, people who used alcohol and the availability of social services’ care packages were areas identified as gaps at the time of the initial interviews. There was no change in this view at follow-up. It was also appreciated that patients at level 3, ‘high intensity users’ requiring case management were being seen and that possibly future, more preventive work should focus on those at level 2 requiring care management. Work was planned to be undertaken on early discharge of older people from acute care with community matrons working in conjunction with rapid response teams. Matrons identified gaps for people with short-term care needs and end of life care as warranting particular attention. Obtaining equipment for some patients proved difficult particularly if they were non-cancer patients due to inequity in funding streams. Community matrons wanted a budget that would enable them to obtain key equipment for clients quickly and easily. Possible developments suggested included having access to health care assistants to routinely monitor clients and report any changes to the matrons, and having predictive criteria to detect patients at end of life in order to prevent exacerbations or admission to hospital.

Avoidable admissions

The prevention of unnecessary hospital admissions for people with long-term conditions was judged a key aim for Primary Care Trusts. Ongoing and regular communication with patients and families to keep them informed was seen as crucial if admissions were to be avoided. The matrons felt they were avoiding admissions and enabling patients to be discharged out of hospital quicker. However, this was anecdotal and not based on routine evaluation of client information. They also judged that some patients do require hospital admission and the aim for them would be a reduction in their length of stay. Matrons stated they need a range of community services to be able to keep people safely at home which could mean practical help for patients to be available. They highlighted the need for meeting social and health needs together, for example, if a client has problems with vision and they are forgetful with medication, social services could undertake a ‘safe and well’ check or medication prompt. Matrons felt that it was often the small ‘day-to-day’ things, which were important and made a big difference to the wellbeing of their clients. A generic worker role, such as Health Care Assistants, could be useful in meeting this need by providing support and help to clients with activities of daily living.

Identify the advantages of the role

The role of community matrons was identified as providing high intensity care for clients and meeting previously unmet needs and so had many advantages. These included:

Providing case management for people with specific long-term conditions, which include those with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, diabetes, Coronary Heart Disease, arthritis, asthma and stroke;

Providing a key point of contact for people at a less severe stage of their condition;

Building up a relationship and trust with patients;

Being able to cross professional boundaries and follow patients through systems, for example, into secondary care which assists with communication;

Proactive and preventative work with patients.

Matrons have knowledge of local services and access to networks of professionals, which they can draw on. Due to their continuing relationship with clients they can detect subtle changes in their condition and pre-empt any deterioration or exacerbation and take preventive action.

“Having that level of relationship with them and their families … is just fantastic and you do get to know them so well, that you can spot the little changes, you can be one step ahead of the game and also working across settings as well, I love it.”

“ …because they have never had anybody involved like this before, they had to think well should I bother the General Practitioner, no I won’t do it today, yes I will its got really bad now and they leave it until the last minute, hopefully they contact us straight away when they are feeling [poorly].”

Matrons have an holistic approach to case management and health and social care, for example, putting people in contact with those that can help patients with financial problems.

Identify the difficulties of the role

Initially the pilot nature of the appointment of community matrons was a concern and may have been responsible for some community matrons moving to other non-community matron posts.

“…since we have come into post we have now been told that basically it is a pilot and we have got 6 months to prove ourselves.”

This situation had improved by the time of the follow-up interviews and action learning events although merger of Primary Care Trusts and management changes was still a source of uncertainty.

Matrons and leads were undergoing high levels of scrutiny, which created pressure. Both the managers and community matrons felt under scrutiny when first appointed especially as patients and health professionals were not familiar with the title or their role. It was appreciated that community matrons were part of the wider network of services and professionals targeting the management of long-term conditions but support from General Practitioners and other professionals was essential. They expected in the future that patients would be referred directly to them rather than having to screen and identify potential patients from General Practitioner practice databases which they had to do initially to establish their case loads for case management. The unpredictable nature of the workload was highlighted because clients are kept on a caseload and can become ‘active’ at any time. This can happen with many clients at the same time, for example those with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease symptoms exacerbated by the weather.

Future developments

Formation and development of care pathways and associated standards of care were planned, as well as an audit to show clear evidence of outcomes of case management as part of a whole infrastructure of services.

It was generally viewed that caseloads were appropriate and that the clients seen were benefiting from the service. Matrons thought that there were still people with long-term conditions with unmet needs that they had not been in contact with, particularly in rural areas. This was anecdotal and accurate information on clients with unmet needs would need to be obtained. The pilot nature of the community matron initiative in the area meant they were restricted to covering a restricted geographic area of the Trust and a number of General Practitioner practices, compared to those in other areas that had managed to cover clients from all practices. It was noted that only when patients come into contact with health and social care services can they be detected.

Little or no information was routinely collected on clients’ experience of services and their satisfaction or their carers. Informal feedback was gathered but this was not standardised and was anecdotal. This feedback could be formally captured and a method developed that could be incorporated by the matrons themselves during practice. When asked in the follow-up interviews the matrons felt that positive developments have been made, and that the role has made a difference to patients but routine evidence was needed. Visible success with patients has bought respect from other professionals. In Primary Care Trust 1 some General Practitioners had initially expressed mixed views about the role and benefits of community matrons but had not wanted matrons to be moved once they had been established.

Stakeholders and participants in the Action Learning Events recommended a broader focus on managing long-term conditions as part of a whole system, which included General Practitioners, Community Matrons, Allied Health Professionals and other therapists. Case management could be provided by a range of people within teams for people with certain conditions. It was thought community matrons were more generic and case managed people with a wider range of conditions, more complex cases and co-morbidities than other case managers.

Discussion

The development of a long-term conditions service was a response to findings in national policy and literature [5–8] and in particular the targets of the Innovation Forum. Findings of the research illustrate the nature of service development in one Innovation Forum pilot area. The role of community matrons has to be part of a whole system of care with elements of both health and social care properly supported by administration. Reliable and efficient information and communication systems need to be established for improved efficiency. This took time to become part of the service but was becoming more widespread during the time of the research.

Matrons felt they have a positive impact for individual clients, which also benefitted the wider health and social care system in areas such as reducing inappropriate admissions, medicines management and reducing General Practitioner visits. Consistent quantitative data on clients with long-term conditions needs to be routinely collected and analysed to inform future developments and establish evidence on effectiveness. Clients’ experiences of services and their satisfaction also need to be routinely collected and analysed to establish evidence of effectiveness and inform future service developments. This is best established during the initial development so that it becomes part of the role. Monitoring was neglected at the start of service development due to pressures of setting up and designing the service itself.

The demands of training and development were intensive especially at the start of the service. The character of the matrons themselves was key to the success of the service and its evolution. They worked hard to establish themselves and their service in the health and social care community, which was a key aim of the policy and did this without infrastructure being in place or administrative support.

Recommendations for service delivery and change come out of this research. There needs to be an increased awareness of the role of community matrons in the case management of people with long-term conditions with other members of the primary health care team, secondary care, social services, voluntary organisations and the wider public, and concurs with other research [17].

Previous findings and the experiences of those at the forefront of service development should be used to inform future development. Results indicated that in this example services for people with a long-term condition could be improved by:

Improved communication and awareness to facilitate integrated care and the continued achievement of Innovations Forum targets and the reduction in unnecessary hospital admissions;

Improved infrastructure—information systems, administration support and generic workers;

Inclusive approaches to care needs—Joint working and increased communication across individuals and providers;

Having generic health and social care workers who are able to work across organisational boundaries. Provision of generic workers across health and social care could increase the effectiveness of service provision along with increased access to ‘step down’ and social care beds;

Better identification of people with long-term conditions who may not be current service users and may be otherwise missed;

Predictive tools for caseload identification early in a patients care needs

Increased targets (include those people further down the triangle) supported by increased staffing.

Conclusion

The development of services takes time and a high level of capacity and adequate provision should be made for a service to evolve and become established. Allowing time to learn from the process of development, continual communication between stakeholders and increasing awareness of the service with others are all important to develop an effective service. Case management should be fully consolidated within a wider infrastructure of services so that it can be fully effective. This includes administrative and information support as well as support from other care roles.

Community matrons found it hard to meet the many demands involved with service development. The demands of their new role, leading on service development, identifying their caseload and developing their practice alongside their education and training was difficult and made more challenging because of the high profile of the role and Innovation Forum targets and scrutiny from others. Changes in the system such as the merger of the organisations and changes made to the role had negative implications for service delivery in this example. The continual changes made integrating the service into the wider system difficult due to lack of understanding of the role, which in turn caused the matrons to feel less able to refer their clients to other services. To increase understanding of the role impacts and outcomes of case management need to be demonstrated with systematic and routine evaluation of patient outcomes. This monitoring should be developed as early as possible in service development so that it is accepted as a routine part of the role. The capacity for routine evaluation should be just as important as service development and training as it forms evidence of effectiveness. Items to monitor include rates of hospital admission and any changes from baseline, patient and carer satisfaction and number of bed days saved. Sharing knowledge and experience should lead to a shared vision and model of provision across the area with agreed care pathways that could be routinely audited and common criteria to allow a consistent view and comparison of impacts and outcomes across the area.

Acknowledgments

The community matrons and service leads who participated in this research project are thanked for their valuable inputs and support. Cheshire County Council is thanked for providing the funds to undertake the study.

Contributor Information

Michelle Russell, Research Institute for Public Policy and Management, Keele University, Keele, Staffordshire, ST5 5BG, UK.

Brenda Roe, Evidence-based Practice Research Centre, Faculty of Health, Edge Hill University, St Helens Road, Ormskirk, Lancashire, L39 4QP, UK.

Roger Beech, Research Institute for Life Course Studies, Keele University, Keele, Staffordshire, ST5 5BG, UK.

Wanda Russell, Research Institute for Public Policy and Management, Keele University, Keele, Staffordshire, ST5 5BG, UK.

Autobiographical Note

Michelle Russell previously worked as a Research Assistant in the area of Health Services Research at Keele University and now is working for a Primary Care Trust in the UK National Health Service.

Reviewers

Jane Melvin, BSc (Hons) RNA, Managing Director, CareMax Limited, Runcorn, Cheshire, UK

Cheryl Amoroso, MPH, BSc, Director of Electronic Medical Records and Informatics Program, Partners In Health, Rwinkwavu Hospital, Rwanda

References

- 1.Department of Health. National service framework for older people. London: Department of Health; 2001. Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4003066 [cited 2009 Jan 28] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wannless D. Securing good care for older people: taking a long-term view. London: Kings Fund; 2006. (Wanless Social Care Review. Kings Fund Report). Available from: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/health_topics/responses_to_the.html. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health. A new ambition for old age: next steps in implementing the National Service Framework for Older People. London: Department of Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robertson G, Gilliard J, Williams C. Promoting independence: “The long marathon to achieving choice and control for older people”. London: Department of Health/Care Service Improvement Partnership; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health. Supporting people with long-term conditions: liberating the talents of nurses who care for people with long-term conditions. London: Department of Health; 2005. Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4102469 [cited 2009 Jan 28] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hudson B. Sea change or quick fix? Policy on long-term conditions in England. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2005;13(4):378–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Health. Improving chronic disease management. London: The Stationery Office; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health. Supporting people with long-term conditions: an NHS and social care model to support local innovation and integration. London: Department of Health; 2005. Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4100252 [cited 2009 Jan 28] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boaden R, Dusheiko M, Gravelle H, Parker S, Pickard S, Roland M, et al. Evercare Evaluation Interim Report: implications for supporting people with long-term conditions in the NHS. Manchester: National Primary Care Research and Development Centre; 2005. Available from: http://www.npcrdc.ac.uk/Publications/evercare%20report1.pdf [cited 2008 Jun] [Google Scholar]

- 10.EverCare. Evercare; 2003. Adapting the EverCare Programme for the National Health Service. Available from: http://www.natpact.nhs.uk/uploads/commissioning/evercareprog.doc [cited 2008 Jun] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health. Speech by Stephen Ladyman MP, Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Community, 18th March 2004: Innovation Forum Launch. London: Department of Health; 2004. Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/News/Speeches/Speecheslist/DH_4077578 [cited 2008 Dec] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NHS Modernisation Agency; Skills for Health. Case management competencies framework for the care of people with long-term conditions. London: Department of Health; 2005. Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4118101 [cited Nov] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brockbank A, McGill I. The action learning handbook: powerful techniques for education, professional development and training. Abingdon, Oxon: RoutledgeFalmer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kings Fund. PARRs (Patients at risk of readmission) London: Kings’ Fund; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kings Fund. Combined Predictive Risk Model, PARR+ (Feb 2006) London: Kings Fund; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Billings J, Dixon J, Mijanovich T, Wennberg D. Case finding for patients at risk of readmission to hospital: development of an algorithm to identify high risk patients. British Medical Journal. 2006 Aug 12;333(7563):32–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38870.657917.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Board M, Symons M. Community matron role development through action learning. Primary Health Care. 2007;17(8):19–22. [Google Scholar]