Abstract

Vaccines directed toward individual strains of highly-variable viruses like influenza lose efficacy when the circulating viruses no longer resemble the vaccine isolate. Historically, inclusion of more than one isolate per subtype of influenza has been limited by the need to include large doses of antigen with typical protein-based vaccine approaches and by concerns that an immunodominant response to one antigen will limit the response to closely related antigens. Here we provide proof of principle demonstrating that a multi-valent vaccine directed against multiple influenza A virus hemagglutinins (HAs) can elicit broad, neutralizing immunity against multiple strains within a single influenza subtype (H3). We employed a DNA vaccine to direct immunity toward the HA component alone, and a live attenuated influenza virus (LAIV) to assess immunity against the whole virus. Delivery of either HA-DNA or LAIV yielded broad protective immunity across multiple antigenic clusters, including heterologous strains, that was similar to the combined immunity of each antigen assessed separately. Priming with HA-DNA followed by an LAIV boost strengthened and broadened the antibody response toward all three H3 HAs. This prime:boost multi-valent approach was thus able to elicit immunity against multiple strains within the H3 subtype without evidence of immune interference between closely related antigens. Although the trivalent vaccine described here is not a universal vaccine, since protection was limited to circulating viruses from about a two decade period, these data suggest that full protection within a subtype is possible using this approach with multiple antigens from current and predicted future influenza strains.

Keywords: Influenza, DNA Vaccine, Hemagglutinin

1. Introduction

There is a significant unmet need for novel vaccination strategies that can elicit broad, immunity against pleiomorphic and rapidly evolving viruses including HIV, influenza [1], and rotavirus [2]. One potential approach is to simultaneously target multiple variants of a specific pathogen in an effort to stimulate immunity against a broad spectrum of epitopes. Using variations on this model, vaccines have been successfully developed against select bacterial and viral pathogens, including pneumococcus [3] and human papillomavirus (HPV) [4]. However, the concern has been expressed that competition between antigens may reduce the efficacy of vaccines containing multiple epitopes [5]. This issue was directly addressed in HPV vaccine recipients where ≥ 99.5% seroconversion was seen against all four vaccine strains [6]. Immunity towards a single component of the quadrivalent vaccine (HPV16) was not compromised compared to that induced using a monovalent preparation [7]. However, suboptimal seroconversion for two of four vaccine constituents included in an experimental vaccine against Dengue virus provides a recent example where immune interference proved problematic [8]. This concern is magnified when consideration is given to targeting closely related antigens within an antigenic group rather than different serotypes as is done in the pneumococcal and HPV examples above. Strategies to overcome this potential obstacle are being considered in the development of vaccines against the highly diverse pathogen HIV [9].

Influenza virus is a negative-sense RNA virus with a genome encoded on 8 segments. The major surface glycoproteins are hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), and stimulation of neutralizing antibodies directed toward the HA remains the focus of most vaccines developed against this virus [10]. Vaccines against influenza have historically demonstrated moderate efficacy and effectiveness when circulating strains closely match the vaccine strain [11], but responses to the vaccine are greatly compromised when there is not a close match [12]. Despite the use of these vaccines, influenza is responsible for 3–5 million severe illnesses and 250–500,000 deaths annually in the industrialized world alone [13]. Current influenza vaccines include a single isolate of three antigenically distinct influenza virus subtypes, two influenza A virus strains (H1N1 and H3N2), and a single influenza B virus isolate. Annual reformulation in an attempt to antigenically match the circulating strain for each of the three subtypes is a time-consuming process that is susceptible to many different forms of failure [14].

In order to address the problems of antigenic drift and annual vaccine reformulation, we developed the hypothesis that a vaccine incorporating multiple HA variants within a single subtype could elicit broad immunity against this subtype. In order for this approach to be efficacious, each strain would have to elicit an immune response in the context of simultaneous administration with multiple closely related strains similar to that seen when each is administered alone. In addition, a delivery method that was not limited by total antigen load, as are protein-based influenza vaccines, would be required. Therefore we focused these preliminary studies on DNA vaccination and use of live, attenuated strains since antigens from many viruses can theoretically be delivered in a small volume using these vehicles.

To provide proof of concept that our multi-valent approach was feasible, we chose to target the H3 HA. Viruses of the H3N2 subtype began circulating in humans in 1968 [15], and are more likely to cause hospitalizations and deaths than viruses of the H1N1 and B subtypes [16–18]. This has resulted in extensive characterization of the evolution of the H3 HA [19,20], which was recently mapped antigenically [21]. H3N2 strains from this subtype’s first 30+ years of circulation thus represent an excellent population against which to test our hypothesis. Here we report that a multi-valent vaccine can elicit broad immunity within an HA subtype, without evidence of immune interference, providing the first evidence that a universal vaccine can be developed using this strategy. These findings have significant implications for development of future vaccines against both seasonal and pandemic influenza, as well as other highly variable pathogens [22].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mice

Adult (6–8-week-old) female C57BL/6 and BALB/cJ mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and housed in groups of four to five as described previously [23]. All animal experiments were performed following the guidelines established by the Animal Care and Use committee at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (Memphis, TN).

2.2. Cloning individual H3 HAs into plasmids

Influenza HA genes were cloned into pHW2000 using BsmBI (New England Bio Labs, Beverly, MA) as described previously [24]. HAs from human H3N2 influenza virus isolates A/Hong Kong/1/68 (HK68, GenBank accession number AF348176), A/Victoria/3/75 (VI75, V01098), and A/Leningrad/6/86 (LE86, DQ508849) were individually cloned into pHW2000 for use in DNA vaccination and creation of reassortant viruses. In addition, the following H3 HAs were individually cloned into pHW2000 for creation of reassortant viruses: A/Port Chalmers/1/73 (PC73, CY009348), A/Texas/1/77 (TX77, AF450246), A/Memphis/6/86 (ME86, M21648), A/Memphis/7/90 (ME90, CY008740), A/Beijing/353/89 (BE89, AF008684), A/Beijing/32/92 (BE92, AF008812), A/Wuhan/359/95 (WU95, AY661190), and A/Sydney/5/97 (SY97, AF180584).

2.3. Construction of 1:1:6 Reassortant Viruses

Reassortant viruses expressing homologous (HK68, VI75, and LE86) and heterologous (PC73, TX77, ME86, ME90, BE89, BE92, WU95, and SY97) H3 HAs were created as described previously [25] using plasmids for A/PR/8/34 PB1, PB2, PA, NP, M, and NS genes (kindly provided by Erich Hoffmann and Robert G. Webster). The NA component used for creation of these viruses was from the SY97 H3N2 influenza isolate (AJ291403). HAs for all viruses matched the corresponding GenBank sequences designated for the HA1, with the exception of ME86, which differed at P13L (C38T) and E27K (A78G, G79A). Rescued viruses were propagated in 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs and characterized in MDCK cells (TCID50) and in mice (MID50 and MLD50) (Table 1). These viruses grew to similar titers at 37°C in MDCK cells but, as expected, most were limited in their growth in vivo, due to the fact that highly glycoslated H3 HAs grow poorly in mice [26].

Table 1.

Properties of reassortant influenza viruses expressing H3 HAs

| H3N2 Isolate | Abbreviation (Cluster)a | Titer (Log10 TCID50/mLb) | Infectivity (MID50c) | Lethality (MLD50c) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/Hong Kong/1/68 | HK68 (HK68) | 8.00 | −1.25 | 5.50 |

| A/Port Chalmers/1/73 | PC73 (EN72) | 8.63 | −1.00 | NDd |

| A/Victoria/3/75 | VI75 (VI75) | 9.25 | 0.38 | 7.50 |

| A/Texas/1/77 | TX77 (TX77) | 8.38 | 3.00 | ND |

| A/Leningrad/360/86 | LE86 (BK79) | 8.63 | 3.38 | 7.63 |

| A/Memphis/6/86 | ME86 (BK79) | 7.63 | 1.75 | 6.63 |

| A/Memphis/7/90 | ME90 (SI87) | 8.50 | 3.00 | ND |

| A/Beijing/353/89 | BE89 (BE89) | 7.63 | 1.75 | ND |

| A/Beijing/32/92 | BE92 (BE92) | 8.63 | 3.38 | ND |

| A/Wuhan/359/95 | WU95 (WU95) | 8.63 | 3.38 | ND |

| A/Sydney/5/97 | SY97 (SY97) | 8.50 | 6.00 | >7.50 |

See Fig. 1 for definition of clusters

In MDCK cells at 37°C

Expressed as Log10 TCID50/mL

ND = Not determined

2.4. Creation of HA-expressing LAIV

Reverse genetics was used to create LAIV incorporating two internal genes (PB1; CY009450 and PB2; CY009451) from A/PR/8/34 with specific mutations that encode a temperature-sensitive (ts)/attenuated (att) phenotype, as described [27]. The PB1 gene used for virus creation differed from the GenBank sequence at positions S393P (T1180C) and R563I (G1688T). The mutated plasmids for PB1 (K391E, A1171G and A1173G; E581G, A1742G and G1743A; A661T, G1981A) and PB2 (N265S, A794G) were created using site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). LAIV incorporated in the multi-valent vaccine were created using the NA gene from the HK68 H3N2 influenza isolate (AF348184). Sequence analyses confirmed the genetic makeup of the viruses, and all LAIV exhibited the expected greater than 2-log difference in growth between 33°C and 37°C (Table 2), that is characteristic of the ts phenotype [27]. The att phenotype was confirmed in the ferret model using a prototype reassortant virus created on the LAIV backbone (HK68/SYts).

Table 2.

Properties of reassortant LAIV expressing H3 HAs

| Temperature-Sensitive Phenotype of LAIV in vitro | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus Strains | Titer (Log10 TCID50/mLa at 37°C) | Titer (Log10 TCID50/mLa at 33°C) | ||||||||

| HK68 HA, SY97 NA (HK68/SYts) | <4.50 | 9.00 | ||||||||

| HK68 HA, HK68 NA (HK68/HKts) | <4.50 | 9.20 | ||||||||

| VI75 HA, HK68 NA (VI75/HKts) | 5.50 | 9.30 | ||||||||

| LE86 HA, HK68 NA (LE86/HKts) | 5.25 | 9.10 | ||||||||

| Attenuated Phenotype of HK68/SYtsin vivob | ||||||||||

| Weight (g) (Change from Day 0) | Temperature (\C) (Change from Day 0) | Day 3 Viral Titersc (Log10 TCID50/mL) | ||||||||

| Day 0 | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 0 | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Nasal Wash | Lung | |

| Ferret 1 | 671 | 673 (+2) | 728 (+57) | 767 (+96) | 37.7 | 38.3 (+0.6) | 38.6 (+0.9) | 37.8 (+0.1) | 4.63 | <1.00 |

| Ferret 2 | 933 | 915 (−18) | 961 (+28) | 979 (+46) | 38.3 | 38.2 (−0.1) | 38.0 (−0.3) | 37.8 (−0.5) | 4.63 | <1.00 |

TCID50 determined using MDCK cells

Ferrets inoculated with 108.0 TCID50 HK68/SYts in 1 mL i.n.

Values reported as for virus grown in MDCK cells at 33\C

2.5. Gene gun inoculation

2.4 μg total DNA content per mg gold was loaded onto the gold particles, which were administered using a Helios gene gun (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) as described [23]. Individual HA-encoding plasmids were administered at a concentration of 0.8 μg DNA per mg gold (2.4 μg per mg gold when all three were administered simultaneously). When HAs were delivered independently, 1.6 μg pHW2000 per mg gold was added to maintain a total DNA content of 2.4 μg per mg gold. Vector control mice received 2.4 μg pHW2000 per mg gold. DNA vaccines were administered at four-week intervals, and three weeks after a third exposure to DNA, mice were challenged with 102 MID50 reassortant influenza viruses delivered in a 100 μL volume, and lung viral titers were quantitated 3 days later.

2.6. LAIV inoculation

Mice were inoculated with 104 to 107 TCID50 (33°C) H3 HA-expressing LAIV (Table 2) in a 50 μL volume. Prior to LAIV inoculation, some mice were divided into groups that received DNA as a prime (either 2.4 μg pHW2000 or 0.8 μg HK68 + 0.8 μg VI75 + 0.8 μg LE86). Mice were primed with DNA on day 0, and boosted with LAIV on day 21. Four weeks after LAIV inoculation, mice were challenged with 104 MID50 reassortant influenza viruses delivered in a 100 μL volume, and lung viral titers were quantitated 3 days later. For challenges using the higher dose of virus (104 MID50), we elected to use ME86 as our sole representative of the BK79 cluster, because the infectious dose for this virus was 2 logs lower than that determined for LE86 (Table 1) and similar reactivities of these two isolates were observed in all other assays. This interesting difference in infectivity may be due to a single amino acid difference (position 138 of the HA1) between these two viruses at a site that has been mapped to the receptor-binding pocket [28].

2.7. Immune Assays

Reassortant viruses expressing homologous and heterologous H3 HAs and SY97 NA were used as antigens for ELISA as described previously [23]. RDE- (Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corp., Westbury, NY) treated sera starting at dilutions of 1:50 (DNA alone) or 1:500 (DNA + LAIV) were tested for presence of influenza-specific IgM, IgG (γ-specific), IgG (H+L), IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, or IgG3 using AP-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL). Reciprocal serum antibody titers were calculated at 50% maximal binding. Individual sera with starting dilution OD405 values that were less than 4 times the OD405 of negative control sera were assigned a titer equivalent to the respective starting dilution.

RDE-treated sera were also analyzed for influenza-reactive antibody using standard HI titer and microneutralization assays. For HI assays [29], chicken red blood cells were used, and titers are reported as the reciprocal of the final serum dilution that inhibited hemagglutination. A titer of less than 10 (starting serum dilution) was assigned for serum samples that did not inhibit hemagglutination. For microneutralization assays [30], MDCK cells were inoculated with serum:virus mixtures, and a pool of mouse monoclonal antibodies specific for influenza A virus nucleoprotein (kindly provided by Robert G. Webster) was used to detect infection of MDCK cells by the virus. Microneutralization titers are reported as the reciprocal of the final serum dilution that neutralizes virus to a level below one-half of the OD492 seen in virus control wells, and a titer of less than 10 (starting serum dilution) was assigned to sera that did not neutralize virus.

2.8. Lung viral titers

Three days after challenge with reassortant influenza viruses expressing homologous and heterologous H3 HAs, viral titers were determined as described previously [23]. MDCK monolayers were inoculated with 100 μL lung homogenates diluted 10-fold in MDCK infection media (10−2 through 10−7 TCID50/mL). Cells were observed for cytopathic effect, and infection within individual wells was confirmed using a standard hemagglutination assay. Individual lung titers are expressed as a ratio using the mean titer for control mice, and the ratio reported for lungs with no detectable virus was 0.1.

2.9. T cell assays

C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with 106 TCID50 (33°C) of viruses expressing HK68 HA and HK68 NA on either a PR8WT or PR8ts backbone in a 30 μL volume i.n. Virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses were analyzed 10 days later by flow cytometry. For peptide stimulation-cytokine (PepC) assays, lymphocytes were first incubated with the indicated peptide at 1 μM for 5 h in the presence of 10 μg/ml brefeldin A, fixed with formaldehyde, and stained with CD8 allophycocyanin (clone 53-6.7; BD Pharmingen), IFN-γ PE (BD Pharmingen), and TNF-α FITC (BD Pharmingen). The established influenza epitopes tested were DbNP366–374, DbPA224–233, DbPB1-F262–70, KbPB1703–711, KbNS2114–121, KbNP217–225, and Kb/DbPB2196–210 [31]. Autofluorescence was gated out using the FL3 channel. The data were acquired on a BD Biosciences FACSCalibur and analyzed using CellQuest software.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Comparison of antibody and viral lung titers between groups was done using analysis of variance (ANOVA). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant for these comparisons. SigmaStat for Windows (SysStat Software, Inc., V 3.11) was utilized for all statistical analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Broad immunity can be induced using a multi-valent DNA vaccine approach

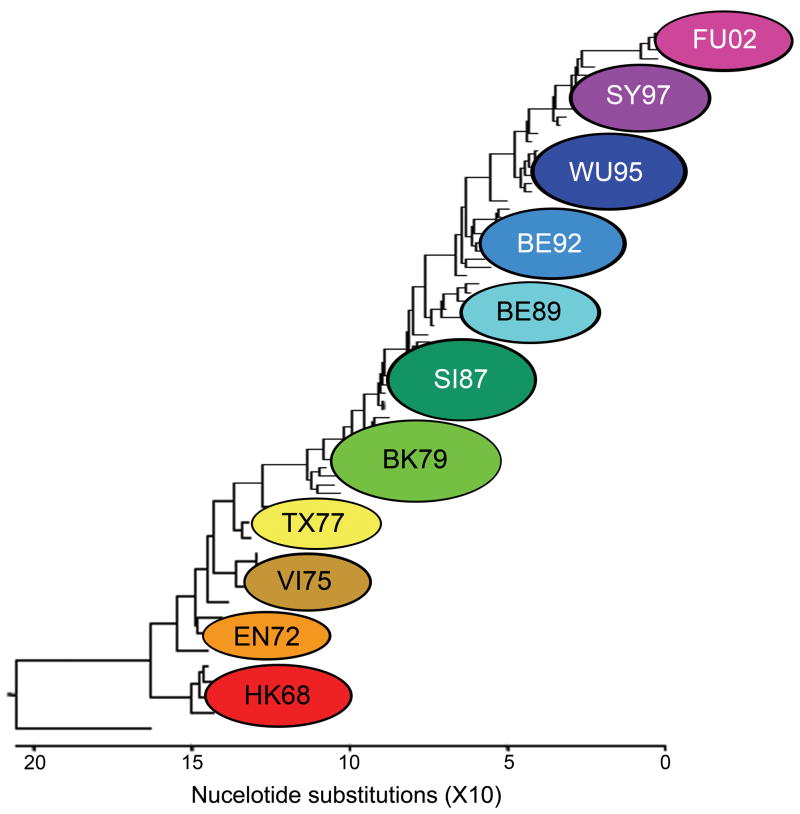

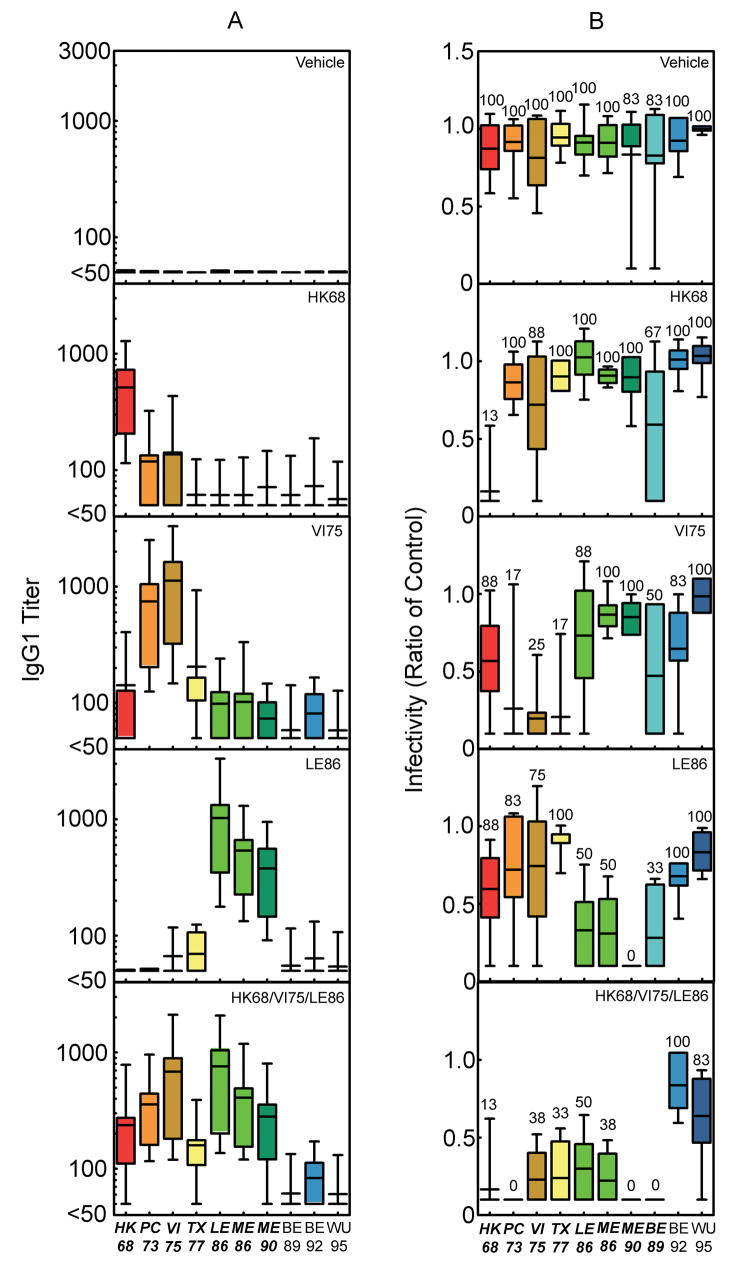

To prove the concept that simultaneous delivery of multiple HAs can induce neutralizing immunity against a broad array of influenza virus HAs of the H3 subtype, we first evaluated the multi-valent concept using a DNA vaccine approach. This vaccination regimen was used to allow for an assessment of HA-specific immune induction without confounding immunity from other influenza virus proteins. Individual HA-expressing plasmids were administered either alone or simultaneously as a mixture containing three distinct H3 HAs (Table 1; HK68, VI75, and LE86). These three strains were selected as they represent alternating clusters from the first 5 antigenic clusters of the H3 HA that appeared after the virus began circulating in humans (Fig. 1). Antigenicity and protective immunity induced after vaccination were tested using individual influenza viruses that expressed HAs representing antigenic clusters defined by Smith et al. [21]: HK68, EN72 (represented by PC73), VI75, TX77, BK79 (represented by LE86 and ME86), SI87 (represented by ME90), BE89, BE92, and WU95 (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Since vaccination using this delivery method is known to induce primarily IgG1 expression [23,32], immunity toward these H3 HA-expressing viruses was reported as influenza-specific IgG1 antibody titers 14 days after a tertiary exposure to plasmid DNA (Fig. 2A). Animals inoculated with a single influenza HA (HK68 or VI75 or LE86) demonstrated influenza-specific IgG1 antibodies against homologous HAs, as well as the heterologous H3 HAs extending out to one antigenic cluster distant from the vaccine strains. Delivery of all three HAs simultaneously (HK68/VI75/LE86) resulted in broad IgG1 expression against homologous and heterologous H3 HAs that included reactivity with all groups observed when the HAs were delivered individually. These data demonstrate that humoral immunity against both homologous and heterologous H3 HAs can be induced through simultaneous inoculation with multiple HAs without evidence of immune interference.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of H3 HA isolates representing clusters from HK68 through A/Fujian/411/02 (FU02). Clusters are derived from matching antigenic data by method of Smith et al. [21]. The tree was generated using the ClustalV method (DNAStar software) and rooted to the H3-expressing virus A/duck/Ukraine/1/63.

Figure 2.

IgG1 antibody and protective immune responses detected after vaccination of BALB/cJ mice with DNA alone. (a) Influenza-reactive antibodies of the IgG1 isotype were detected 14 days after tertiary exposure to the plasmid DNA indicated in each panel. The bars represent the mean ± standard deviation for IgG1 antibodies that reacted with viruses expressing the individual H3 HAs indicated on the x-axis. The number of mice represented by the individual bars are as follows: vehicle, n = 82; HK68, n = 70; VI75, n = 70; LE86, n = 69; and HK68/VI75/LE86, n = 85. Sera from all of the mice in each group were tested against each of the viruses expressing the individual H3 HAs indicated on the x-axis. (b) Infectivity for mice challenged 21 days after tertiary exposure to the plasmid DNA is indicated in each panel. The bars represent the mean ± standard deviation for the lung viral titers detected three days after challenge (102 MID50) with viruses expressing the individual H3 HAs indicated on the x-axis. Lung titers from individual mice are represented as a ratio calculated using the mean lung viral titer from mice in the control group challenged with the corresponding viruses. The ratio reported for lungs with no detectable virus is 0.1. The number above the individual bars indicates the percent of mice with detectable virus in their lungs 3 days after challenge. For each virus indicated on the x-axis, 6 mice were challenged per vaccine group, with the exception of the mice challenged with viruses expressing HK68, VI75, LE86, and ME86 (n = 8). Bolding and italics indicate where differences in the antibody or lung virus titers for the group vaccinated with HK68/VI75/LE86 achieved a level of statistical significance (P<0.05 by ANOVA) compared with the corresponding DNA vehicle recipients. In no cases did titers after delivery of HK68/VI75/LE86 differ significantly when compared to delivery of H3 HA’s individually (p > 0.05).

To test the ability of this DNA vaccine-induced humoral immunity to protect against viral challenge, mice were inoculated with reassortant viruses (102 MID50) expressing homologous and heterologous H3 HAs (Fig. 2B). In concordance with our reported IgG1 expression, protection against viruses expressing homologous HAs and heterologous HAs located at a distance of one antigenic cluster was observed when mice were vaccinated with the HAs delivered individually. When all three H3 HAs were delivered simultaneously, protective immunity against homologous and heterologous HAs matched that of the combined protection for the HAs delivered separately. In addition, this strong, broadly cross-protective immunity extended to a further antigenic cluster represented by BE89, a result superior to that predicted by the IgG1 antibody response detected after any individual HA vaccine (Fig. 2A). Thus, HA-specific immunity induced by a multi-valent DNA vaccine yielded protection against sublethal challenge with a wide range of homologous and heterologous H3 HAs that was equivalent or superior to the combined coverage of 3 separate vaccines when their results were considered together.

3.2. LAIV can be used in a multi-valent vaccine

Having shown that a multi-valent DNA vaccine directed against the HA alone could elicit broad immunity within the H3 subtype, we next assessed whether similar results could be achieved using a multi-valent LAIV vaccine. LAIV strains were created using a 6-gene A/PR/8/34 background mutated to achieve temperature-sensitivity and attenuation (Table 2) [27]. Initial studies conducted using a dose of 107 TCID50 LAIV per mouse demonstrated induction of IgG1 expression that was consistently superior to that seen with DNA vaccination alone (Fig. S1). To avoid toxicity induced with this high dose of LAIV, we repeated the experiment with lower doses (Fig. S2). The dose of LAIV that induced optimal antigenicity with no overt illness was 106 TCID50, which was used for all further studies. Additional characterization of humoral and cellular responses to inoculation with 106 TCID50 LAIV was performed, and compared to responses seen after delivery of 106 TCID50 WT virus (Fig. S3). Immune responses were in general somewhat lower after LAIV inoculation than after infection with WT virus, but influenza-specific T cells and antibodies representing multiple IgG subclasses including IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG3 were induced by LAIV. These data demonstrate that viruses created on the LAIV backbone are able to elicit functional humoral and cellular responses, without evidence of the morbidity seen after WT virus delivery.

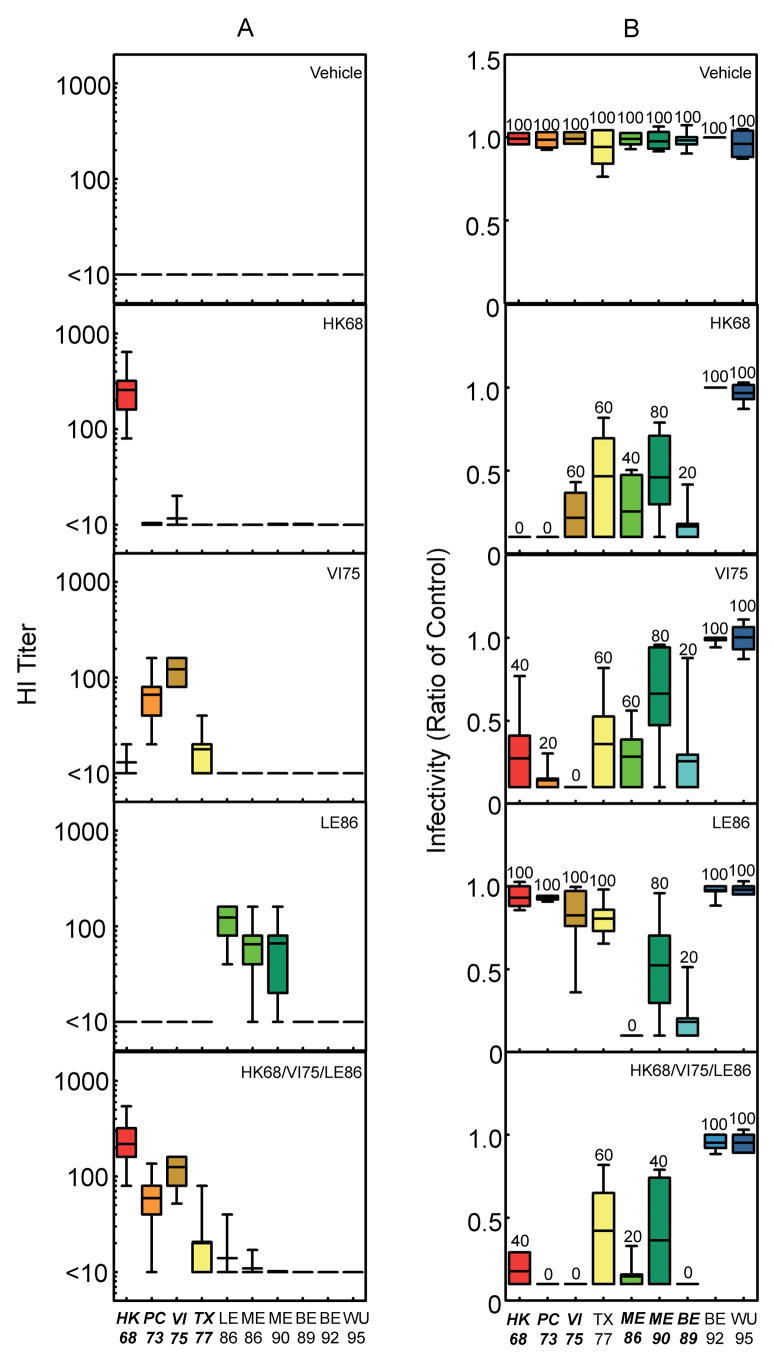

After optimizing and characterizing the humoral and cellular immune responses to H3 HA-expressing LAIV, we designed an experiment to assess the potential for LAIV to act as a vehicle for HA delivery in our multi-valent vaccine approach. For these studies, mice were mock-primed with DNA vehicle, and boosted i.n. with LAIV expressing HK68, VI75, or LE86 HAs either alone or combined. As a control for LAIV inoculation, mice received allantoic fluid from eggs that were mock infected. IgG1antibody titers detected by ELISA were extremely high against all strains tested through the SY97 cluster (Fig. S1 and data not shown) and may have represented antibody directed against other components of the virus. Thus, HI titer was used to directly measure the induction of HA-specific antibodies, as this assay allowed for discrimination between responses to viruses expressing homologous and heterologous H3 HAs (Fig. 3A). In order to discriminate between groups in the challenge model, a higher dose of challenge virus (104 MID50) than in the DNA vaccination experiments (102 MID50) was utilized for LAIV studies after preliminary studies demonstrated complete neutralization against strains through WU95 at the lower dose (data not shown). Delivery of individual HA-expressing LAIV after priming with DNA vehicle yielded anti-sera specific for viruses expressing homologous HAs, with reactivity toward heterologous HAs evident (Fig 3A). Delivery of all three LAIV isolates simultaneously did not consistently induce antibodies directed toward viruses expressing homologous (LE86) and a related heterologous (ME86) HA, as detected using HI (despite high titers to these strains by ELISA; Fig. S1 and data not shown). However, even with suboptimal humoral immunity as measured by HI, protection against challenge with both homologous and heterologous H3 HA-expressing viruses (104 MID50) was observed through the BE89 cluster (Fig. 3B). Thus, recipients of LAIV were protected against infection with a range of viruses exhibiting more breadth than could be predicted using HI titers when either a single LAIV or multiple LAIVs were administered.

Figure 3.

HI titer and protective immune responses detected after vaccination of BALB/cJ mice with pHW2000 + LAIV. (a) Influenza-reactive antibodies present in serum 21 days after exposure to pHW2000 DNA delivered as a prime and HA-expressing LAIV delivered as a boost. The individual LAIV inoculated are indicated in the panels, which show HA-specific antibody expression reported as HI titer. The bars represent the mean ± standard deviation of the HI titer observed after interaction of sera with viruses expressing the individual H3 HAs indicated on the x-axis. The number of mice represented by the individual bars are as follows: allantoic fluid, n = 53; HK68, n = 50; VI75, n = 50; LE86, n = 50; and HK68/VI75/LE86, n = 56. Sera from all of the mice in each group were tested against each of the viruses expressing the individual H3 HAs indicated on the x-axis. (b) Infectivity for mice challenged 28 days after exposure to the LAIV indicated in each panel. The bars represent the mean ± standard deviation for the lung viral titers detected three days after challenge (104 MID50) with viruses expressing the individual H3 HAs indicated on the x-axis. Lung titers from individual mice are represented as a ratio calculated using the mean lung viral titer from mice in the control group challenged with the corresponding viruses. The ratio reported for lungs with no detectable virus is 0.1. The number above the individual bars indicates the percent of mice with detectable virus in their lungs 3 days after challenge. For each virus indicated on the x-axis, 5 mice were challenged per vaccine group, with the exception of mice challenged with TX77, BE92, and WU95 after priming with pHW2000 and boosting with Allantoic Fluid (n = 4 per group). Italics indicate where difference in antibody and lung virus titers for the group vaccinated with HK68/VI75/LE86 achieved a level of statistical significance (P<0.05 by ANOVA) compared with allantoic fluid recipients. In no cases did titers after delivery of all three LAIV simultaneously (HK68/VI75/LE86) differ significantly when compared to delivery of H3 HA’s individually (p > 0.05).

3.3. Multi-valent vaccine using a prime:boost approach

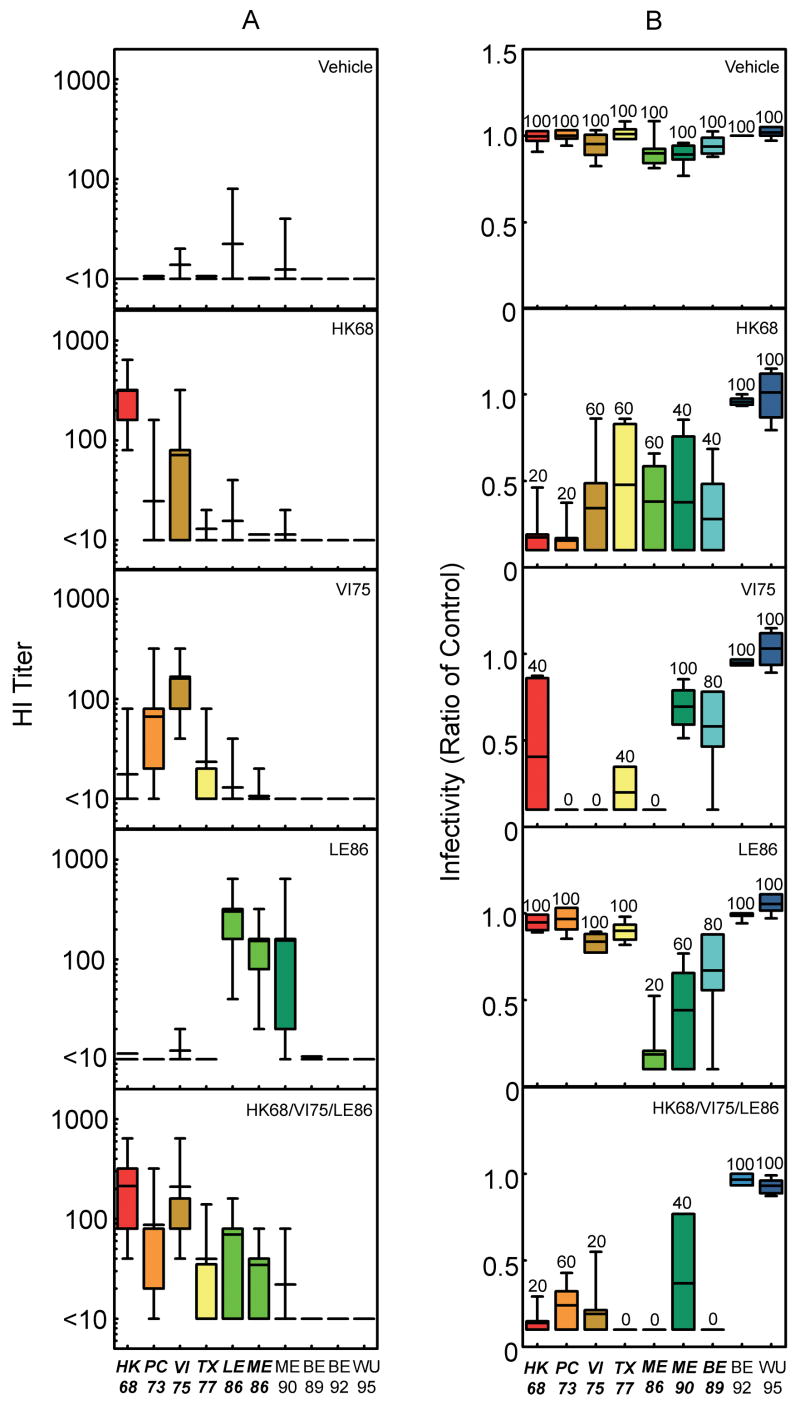

In order to test the effect of a multi-valent DNA prime on the multi-valent LAIV boost, immunization and challenge using the LAIV delivery method was repeated with HK68/VI75/LE86 DNA delivered as a prime (Fig. 4). In this experiment, the most noticeable benefit of HA-DNA priming was that the breadth of detectable humoral immunity was improved relative to LAIV. Specifically, antibodies toward viruses expressing TX77, LE86, and ME86 were more consistently measured in the group that received HK68/HKts + VI75/HKts + LE86/HKts after priming with HK68/VI75/LE86 DNA, than the group that was primed with DNA vehicle (compare Figs. 3A and 4A). Protection observed after challenge with the higher virus dose (104 MID50; Fig. 4B) once again demonstrated vaccine-induced immunity against homologous and heterologous HAs through the BE89 HA cluster. Thus, while humoral immunity detected after HK68/VI75/LE86 HA-DNA priming (Fig. 4A) was superior to that seen after priming with DNA vehicle (Fig. 3A), as measured by HI, delivery of three H3 HAs simultaneously in LAIV form was protective against infection through the BE89 cluster, encompassing approximately 20 years of H3 HA evolution.

Figure 4.

HI titer and protective immune responses detected after vaccination of BALB/cJ mice with HK68/VI75/LE86 + LAIV. (a) Influenza-reactive antibodies present in serum 21 days after exposure to HA administered in a prime:boost manner, with HK68/VI75/LE86 DNA serving as the prime and the individual LAIV noted in the panels serving as the boost, were measured using HI. The bars represent the mean ± standard deviation of the HI titer observed after mixing sera with viruses expressing the individual H3 HAs indicated on the x-axis. The number of mice represented by the individual bars are as follows: allantoic fluid, n = 50; HK68, n = 50; VI75, n = 50; LE86, n = 50; and HK68/VI75/LE86, n = 55. Sera from all of the mice in each group were tested against each of the viruses expressing the individual H3 HAs indicated on the x-axis. (b) Infectivity for mice challenged 28 days after exposure to the LAIV indicated in each panel. The bars represent the mean ± standard deviation for the lung viral titers detected three days after challenge (104 MID50) with viruses expressing the individual H3 HAs indicated on the x-axis. Lung titers from individual mice are represented as a ratio calculated using the mean lung viral titer from mice in the control group challenged with the corresponding viruses. The ratio reported for lungs with no detectable virus is 0.1. The number above the individual bars indicates the percent of mice with detectable virus in their lungs 3 days after challenge. For each virus indicated on the x-axis, 5 mice were challenged per vaccine group, with the exception of the group challenged with BE89 after priming with HK68/VI75/LE86 DNA and boosting with HK68/VI75/LE86 LAIV (n = 4). Bolding and italics indicate where difference in antibody and lung virus titers for the group vaccinated with HK68/VI75/LE86 achieved a level of statistical significance (P<0.05 by ANOVA) compared with allantoic fluid recipients. In no cases did titers after delivery of all three LAIV simultaneously (HK68/VI75/LE86) differ significantly when compared to delivery of H3 HA’s individually (p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

We postulated that broad, neutralizing immunity against a specific influenza subtype such as H3 can be induced by simultaneous inoculation with multiple HAs. If viable, this approach offers a potential solution to the challenges presented by antigenic drift, and could eliminate the need for annual prognostication and repeated yearly re-vaccination. Our data provide proof of concept for this approach. Delivery of multiple antigens together yielded broad humoral and protective immunity within the subtype. The utilization of strategies known to induce heterovariant protection allowed us to provide coverage for more than 20 years of virus evolution with only 3 vaccine strains. Because this heterovariant immunity extended two full antigenic clusters forward in evolutionary time beyond the strains included in the vaccine (SI87 and BE89) and one antigenic cluster beyond detection of antibody (BE89), the effects of antigenic drift would be minimized. We propose that the vaccine strategy described here has potential to increase the breadth of immunity currently achieved with annual influenza vaccine programs, with theoretical potential for development of a universal vaccine against influenza virus.

In the short term, our data suggest that targeting types or subtypes where multiple related lineages or strains circulate using a multi-antigen approach and delivery methods that provide heterovariant immunity may provide protection for several years beyond the single season. Current examples where this might be valuable are influenza B viruses and H5N1 avian influenza strains. Circulating strains of influenza B viruses derive from two distinct lineages, and the antigenic diversity of these strains is more limited than with influenza A viruses [33]. The recurring problem of improper prediction of the dominant circulating lineage, which was most recently seen in the 2007–08 influenza season [34], is further complicated by evidence that isolates from each of the two lineages can co-circulate during a single season [35]. Similarly, multiple different clades of H5N1 viruses are entering the human population [36], making it increasingly difficult to predict which isolates to include in early vaccine formulations against pandemic influenza. A multi-valent vaccine developed against multiple influenza B virus strains/lineages might provide durable protection for many years, allowing this antigen to be split out from the annual re-formulation process and simplifying seasonal vaccine production. A multi-valent vaccine could also be developed against the avian subtype most likely to cause a pandemic, H5N1, or against multiple potentially pandemic HA subtypes [37]. In the medium to long term, development of the ability to predict potential drift strains would allow their inclusion in a multi-valent vaccine prior to their emergence, further extending the effective lifespan of the vaccine or resulting in a universal vaccine if all potential epitopes can be defined and included.

Historically, there are several instances, most prior to our current understanding of antigenic drift and shift, where influenza vaccines have included more than a single isolate from a subtype. For example, antigenic drift in the 1940s led to the designation of the new H1N1 strain as A1 to distinguish it from the previously circulating strain named A, and vaccines containing both antigens were formulated and studied. Efficacy and effectiveness of early polyvalent vaccines were inconsistent, with some generating immunity equivalent to that of monovalent preparations [12,38,39] and others failing to do so [40–42]. In some cases the decreased immunity of the polyvalent preparations was attributed to the need to reduce the antigen content to accommodate multiple strains [42]. Increased knowledge of influenza evolution and antigenic drift led to recommendations in the early 1970s limiting the included strains to only those currently circulating, in an effort to increase the potency toward these individual components by increasing the antigenic mass [43,44]. Using assays to quantitate hemagglutinin content in vaccines [45,46], assessments of reactogenicity versus antigenicity were performed to balance maximum antigen content with maximum tolerated side effects [47,48]. As a result, trivalent influenza vaccines are now typically formulated using 15 μg per HA (45 μg total HA content) [49,50]. The narrow antigenic specificity of unadjuvanted protein-based vaccines coupled with the limits on total antigen load that can be accommodated led us to utilize alternative routes of delivery in this study.

As proof of concept, we used two vehicles for influenza HA delivery to explore the multi-valent approach. Vaccines delivered using DNA-based approaches have shown efficacy in small animal models [51] but, with some notable exceptions [52], have not translated well into humans [53]. However, there is mounting evidence, including the results presented here, that indicate that using DNA as a prime in prime:boost vaccine regimens improves immunity [54], especially when multiple antigens are delivered simultaneously [55–57]. The second vehicle we used for HA delivery was LAIV. LAIVs are currently approved by the FDA for use in individuals aged 2–49 [58] and have shown significant efficacy and effectiveness against both homologous [59] as well as some heterologous [60,61] HAs. In a previous study examining LAIV in the mouse model, two inoculations with greater than 107 TCID50 elicited antibody responses against A/Leningrad/134/57, but the inoculation of this high dose was associated with morbidity and mortality [62]. We saw similar effects at this dose (Fig. S2). Studies in both ferrets and humans report monovalent LAIV preparations containing 107.6–109.0 TCID50 show increased incidence of febrile responses [63–65], and similar to our results, the human studies report elimination of the adverse effect after a one log reduction in the inoculation dose [64,65].

One interesting finding from the data presented here is the reduced immunogenicity against one of three vaccine components (LE86) when all three were delivered simultaneously in LAIV form. Antigenic competition from multi-valent vaccines remains a significant concern [6–8], and these data may be evidence of direct competition. However, this may be specific to LE86 in the mouse model as WT virus expressing this HA replicated poorly compared to others such as ME86. Priming with HA-DNA overcame the potential competition, but this issue will require further attention in more complex situations where more than 3 HAs are incorporated in a single vaccine. In addition, the poorly understood phenomenon of original antigenic sin remains a concern when closely related HA antigens are delivered in a sequential manner [66–68]. It is possible this phenomenon was avoided in this study due to the simultaneous delivery of the antigens; original antigenic sin is typically seen in animal models with sequential exposure to antigens. In addition, the data presented here clearly demonstrate that LAIV has the ability to not only stimulate antibodies, but also T cells, and this enhancement in T cell immunity and its potential to aid heterovariant immunity may provide an added benefit for LAIV in a universal vaccine beyond the outcome parameters assessed here [69]. Finally, evidence for protection in the absence of detectable antibody (BE89 cluster) provides another example of the significant gap in our knowledge of immune correlates of protection against influenza virus [70–72]. Identification of more relevant correlates of protective immunity will allow us to more adequately define the true breadth of immunity induced in this and similarly designed studies.

We have demonstrated that heterovariant immunity toward the influenza virus HA of a specific subtype (H3) can be induced using DNA and LAIV delivery vehicles, as a proof of concept that a multi-valent approach can provide the broad immunity desired for vaccines against seasonal and pandemic influenza. However, the implications of this work are broader than these two vaccine vehicles. In addition to DNA and LAIV, testing other vaccine platforms including inactivated influenza vaccines, viral vectors for HA delivery, or recombinant HA proteins in a multi-valent regimen alone or in combination would be predicted to yield similar results. Recent evidence demonstrating that heterologous immunity can be induced using a monovalent H5 influenza vaccine in the context of a novel adjuvant system [73], further expands the repertoire of influenza vaccine formulations that could be tested using this approach. Early studies with alum as an adjuvant for influenza vaccines also detected the anticipated heterologous cross-reactivity in the context of a dose-sparing regimen [74,75], features that might help overcome the unattractive features of unadjuvanted protein vaccines. We propose that the breadth of immunity induced using the vaccine regimen described here hints at potential application of this technology toward other influenza HAs (including influenza B virus and H5N1), the dominant circulating strains of which are currently difficult to predict. That 3 strains were able to protect against more than 20 years of HA evolution promises that a finite number of vaccine constructs could protect against many potential circulating variants. Application of this strategy to other highly variable viruses such as HIV may yield similar breakthroughs in our ability to protect against continuously evolving pathogens.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. IgG1 antibody responses after vaccination of BALB/cJ mice with DNA, LAIV, or DNA + LAIV. Influenza-reactive antibodies of the IgG1 isotype were detected 14 days after tertiary exposure to plasmid DNA indicated on the x-axis, or 21 days after exposure to LAIV (107 TCID50) indicated on the x-axis. Reactivity was detected using HK68/SY- (A), VI75/SY- (B), or LE86/SY- (C) coated plates. The individual bars in the graphs represent the mean ± standard deviation for the following number of mice per group for DNA: vehicle, n = 82; HK68, n = 70; VI75, n = 70; LE86, n = 69; and HK68/VI75/LE86, n = 85. The individual bars in the graphs represent the mean ± standard deviation for the following number of mice per group for pHW2000 + LAIV (LAIV): HK68/HKts, n = 3; VI75/HKts, n = 5; LE86/HKts, n = 5; and HK68/HKts + VI75/HKts + LE86/HKts, n = 4. The individual bars in the graphs represent the mean ± standard deviation for the following number of mice per group for HK68/VI75/LE86 + LAIV (DNA + LAIV): HK68/HKts, n = 16; VI75/HKts, n = 19; LE86/HKts, n = 20; and HK68/HKts + VI75/HKts + LE86/HKts, n = 17. Responses to both LAIV alone and DNA + LAIV were significantly greater (p < 0.05 by ANOVA) than corresponding responses to DNA alone for all groups measured; there were no statistically significant differences between LAIV and DNA + LAIV groups.

Figure S2. Dose response for LAIV expressing HK68 or LE86 HA. BALB/cJ mice (n = 5 per group) were inoculated with 104–107 TCID50 (33°C) LAIV expressing HK68 HA or LE86 HA, and weights are reported as the mean percent initial body weight for the group (A). Influenza-reactive antibodies present in sera 21 days after inoculation were detected using HI (B). For each group used in sera HI titer analyses, n = 5, with the exception of the group inoculated with 107 TCID50 HK68/HKts (n = 3).

Figure S3. Responses of C57BL/6 mice to inoculation with HK68/HKwt (n = 5) or HK68/HKts (n = 5). Mice were inoculated with 106 TCID50 (33°C) HK68/HKwt or HK68/HKts, and weights are reported as the mean percent initial body weight for each group(A). Influenza-reactive humoral immune response, as measured using HI, microneutralization, and isotype-specific ELISA are reported (B). Influenza peptide-specific T cell responses present in the BAL and spleen are reported as the total number of cells specific for the peptides indicated on the x-axis (C) and the percent of the peptide-specific cells that were TNF-α/IFN-γ positive (D). The percent of cells that are TNF-α/IFN-γ positive is in part a measure of cell quality and has been associated with the efficacy of memory responses [76].

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert G. Webster for providing both mouse monoclonal antibodies against influenza A virus nucleoprotein and, along with Erich Hoffmann, A/PR/8/34 plasmids used to create viruses by reverse genetics. We also thank the Hartwell Center for providing sequence analyses, and the animal resource center at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. This work was supported by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

V.C.H. and J.A.M. conceived the concept and wrote the manuscript. V.C.H. and P.G.T. designed and performed experiments for assessment of humoral and cellular immunity used to directly compare responses to HK68/HKwt and HK68/HKts. V.C.H. designed and performed all other experiments.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Karlsson Hedestam GB, Fouchier RA, Phogat S, Burton DR, Sodroski J, Wyatt RT. The challenges of eliciting neutralizing antibodies to HIV-1 and to influenza virus. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6(2):143–55. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crawford SE, Estes MK, Ciarlet M, Barone C, O’Neal CM, Cohen J, et al. Heterotypic protection and induction of a broad heterotypic neutralization response by rotavirus-like particles. J Virol. 1999;73(6):4813–22. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4813-4822.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black S, Shinefield H, Fireman B, Lewis E, Ray P, Hansen JR, et al. Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children. Northern California Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19(3):187–95. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200003000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(5):1167–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI28607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brody NI, Siskind GW. Studies on antigenic competition. J Exp Med. 1969;130(4):821–32. doi: 10.1084/jem.130.4.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reisinger KS, Block SL, Lazcano-Ponce E, Samakoses R, Esser MT, Erick J, et al. Safety and persistent immunogenicity of a quadrivalent human papillomavirus types 6, 11, 16, 18 L1 virus-like particle vaccine in preadolescents and adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(3):201–9. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000253970.29190.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garland SM, Steben M, Hernandez-Avila M, Koutsky LA, Wheeler CM, Perez G, et al. Noninferiority of antibody response to human papillomavirus type 16 in subjects vaccinated with monovalent and quadrivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccines. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14(6):792–5. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00478-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun W, Nisalak A, Gettayacamin M, Eckels KH, Putnak JR, Vaughn DW, et al. Protection of Rhesus monkeys against dengue virus challenge after tetravalent live attenuated dengue virus vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(12):1658–65. doi: 10.1086/503372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhan X, Martin LN, Slobod KS, Coleclough C, Lockey TD, Brown SA, et al. Multi-envelope HIV-1 vaccine devoid of SIV components controls disease in macaques challenged with heterologous pathogenic SHIV. Vaccine. 2005;23(46–47):5306–20. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huber VC, McCullers JA. FluBlok, a recombinant influenza vaccine. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2008;10(1):75–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meiklejohn G. Viral respiratory disease at Lowry Air Force Base in Denver, 1952–1982. J Infect Dis. 1983;148(5):775–84. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.5.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francis T, Salk JE, Quilligan JJ. Experience with Vaccination Against Influenza in the Spring of 1947: A Preliminary Report. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1947;37(8):1013–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.37.8.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stohr K. Preventing and treating influenza. BMJ. 2003;326(7401):1223–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7401.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerdil C. The annual production cycle for influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2003;21(16):1776–9. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cockburn WC, Delon PJ, Ferreira W. Origin and progress of the 1968–69 Hong Kong influenza epidemic. Bull World Health Organ. 1969;41(3):345–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Cox N, Anderson LJ, et al. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;289(2):179–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Bridges CB, Cox NJ, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA. 2004;292(11):1333–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.11.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simonsen L, Fukuda K, Schonberger LB, Cox NJ. The impact of influenza epidemics on hospitalizations. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(3):831–7. doi: 10.1086/315320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bush RM, Fitch WM, Bender CA, Cox NJ. Positive selection on the H3 hemagglutinin gene of human influenza virus A. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16(11):1457–65. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knossow M, Skehel JJ. Variation and infectivity neutralization in influenza. Immunology. 2006;119(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02421.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith DJ, Lapedes AS, de Jong JC, Bestebroer TM, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus AD, et al. Mapping the antigenic and genetic evolution of influenza virus. Science. 2004;305(5682):371–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1097211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCullers JA. Influenza mutations: trying to hit a moving target. Fut Virol. 2006;1(3):255–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huber VC, McKeon RM, Brackin MN, Miller LA, Keating R, Brown SA, et al. Distinct contributions of vaccine-induced immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgG2a antibodies to protective immunity against influenza. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13(9):981–90. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00156-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffmann E, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y, Hobom G, Webster RG. A DNA transfection system for generation of influenza A virus from eight plasmids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(11):6108–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100133697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffmann E, Krauss S, Perez D, Webby R, Webster RG. Eight-plasmid system for rapid generation of influenza virus vaccines. Vaccine. 2002;20(25–26):3165–70. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00268-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vigerust DJ, Ulett KB, Boyd KL, Madsen J, Hawgood S, McCullers JA. N-linked glycosylation attenuates H3N2 influenza viruses. J Virol. 2007;81(16):8593–600. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00769-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin H, Zhou H, Lu B, Kemble G. Imparting temperature sensitivity and attenuation in ferrets to A/Puerto Rico/8/34 influenza virus by transferring the genetic signature for temperature sensitivity from cold-adapted A/Ann Arbor/6/60. J Virol. 2004;78(2):995–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.2.995-998.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matrosovich MN, Gambaryan AS, Teneberg S, Piskarev VE, Yamnikova SS, Lvov DK, et al. Avian influenza A viruses differ from human viruses by recognition of sialyloligosaccharides and gangliosides and by a higher conservation of the HA receptor-binding site. Virology. 1997;233(1):224–34. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Committee on Standard Serological Procedures in Influenza Studies. An agglutination-inhibition test proposed as a standard of reference in influenza diagnostic studies. J Immunol. 1950;65(3):347–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huber VC, McCullers JA. Live attenuated influenza vaccine is safe and immunogenic in immunocompromised ferrets. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(5):677–84. doi: 10.1086/500247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas PG, Brown SA, Keating R, Yue W, Morris MY, So J, et al. Hidden epitopes emerge in secondary influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses. J Immunol. 2007;178(5):3091–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feltquate DM, Heaney S, Webster RG, Robinson HL. Different T helper cell types and antibody isotypes generated by saline and gene gun DNA immunization. J Immunol. 1997;158(5):2278–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCullers JA, Wang GC, He S, Webster RG. Reassortment and insertion-deletion are strategies for the evolution of influenza B viruses in nature. J Virol. 1999;73(9):7343–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7343-7348.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: influenza activity--United States, September 30, 2007-February 9, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(7):179–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanegae Y, Sugita S, Endo A, Ishida M, Senya S, Osako K, et al. Evolutionary pattern of the hemagglutinin gene of influenza B viruses isolated in Japan: cocirculating lineages in the same epidemic season. J Virol. 1990;64(6):2860–5. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.2860-2865.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu WL, Chen Y, Wang P, Song W, Lau SY, Rayner JM, et al. Antigenic profile of avian H5N1 viruses in Asia from 2002 to 2007. J Virol. 2008;82(4):1798–807. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02256-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huber VC, McCullers JA. Vaccines against pandemic influenza: what can be done before the next pandemic? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(10 Suppl):S113–S117. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318168b749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blow RJ. Polyvalent influenza vaccine in general practice. Br Med J. 1964;2(5414):943. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5414.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hennessy AV, Davenport FM. Relative antigenic potency in man of polyvalent influenza virus vaccines containing isolated hemagglutinins or intact viruses. J Immunol. 1966;97(2):235–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hennessy AV, Davenport FM. Vaccination of infants against influenza with polyvalent influenza hemagglutinin. JAMA. 1967;200(10):896–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laxdal OE, Evans GE, Braaten V, Robertson HE. Acute respiratory infectinos in children. II. A trial of polyvalent virus vaccine. Can Med Assoc J. 1964;90:15–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maynard JE, Dull HB, Hanson ML, Feltz ET, Berger R, Hammes L. Evaluation of monovalent and polyvalent influenza vaccines during an epidemic of type A2 and B influenza. Am J Epidemiol. 1968;87(1):148–57. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eickhoff TC. Immunization against influenza: rationale and recommendations. J Infect Dis. 1971;123(4):446–54. doi: 10.1093/infdis/123.4.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salk J, Salk D. Control of influenza and poliomyelitis with killed virus vaccines. Science. 1977;195(4281):834–47. doi: 10.1126/science.320661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schild GC, Wood JM, Newman RW. A single-radial-immunodiffusion technique for the assay of influenza haemagglutinin antigen. Proposals for an assay method for the haemagglutinin content of influenza vaccines. Bull World Health Organ. 1975;52(2):223–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wood JM, Schild GC, Newman RW, Seagroatt V. An improved single-radial-immunodiffusion technique for the assay of influenza haemagglutinin antigen: application for potency determinations of inactivated whole virus and subunit vaccines. J Biol Stand. 1977;5(3):237–47. doi: 10.1016/s0092-1157(77)80008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gross PA, Quinnan GV, Gaerlan PF, Denning CR, Davis A, Lazicki M, et al. Potential for single high-dose influenza immunization in unprimed children. Pediatrics. 1982;70(6):982–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Antibody responses and reactogenicity of graded doses of inactivated influenza A/New Jersey/76 whole-virus vaccine in humans. J Infect Dis. 1977;136(Suppl):S475–S483. doi: 10.1093/infdis/136.supplement_3.s475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.La Montagne, Noble GR, Quinnan GV, Curlin GT, Blackwelder WC, Smith JI, et al. Summary of clinical trials of inactivated influenza vaccine - 1978. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5(4):723–36. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.4.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quinnan GV, Schooley R, Dolin R, Ennis FA, Gross P, Gwaltney JM. Serologic responses and systemic reactions in adults after vaccination with monovalent A/USSR/77 and trivalent A/USSR/77, A/Texas/77, B/Hong Kong/72 influenza vaccines. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5(4):748–57. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.4.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fynan EF, Webster RG, Fuller DH, Haynes JR, Santoro JC, Robinson HL. DNA vaccines: protective immunizations by parenteral, mucosal, and gene-gun inoculations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(24):11478–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drape RJ, Macklin MD, Barr LJ, Jones S, Haynes JR, Dean HJ. Epidermal DNA vaccine for influenza is immunogenic in humans. Vaccine. 2006;24(21):4475–81. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Donnelly JJ, Wahren B, Liu MA. DNA vaccines: progress and challenges. J Immunol. 2005;175(2):633–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berzofsky JA, Ahlers JD, Belyakov IM. Strategies for designing and optimizing new generation vaccines. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1(3):209–19. doi: 10.1038/35105075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hurwitz JL, Slobod KS, Lockey TD, Wang S, Chou TH, Lu S. Application of the polyvalent approach to HIV-1 vaccine development. Curr Drug Targets Infect Disord. 2005;5(2):143–56. doi: 10.2174/1568005054201517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hurwitz JL, Zhan X, Brown SA, Bonsignori M, Stambas J, Lockey TD, et al. HIV-1 vaccine development: tackling virus diversity with a multi-envelope cocktail. Front Biosci. 2008;13:609–20. doi: 10.2741/2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sandstrom E, Nilsson C, Hejdeman B, Brave A, Bratt G, Robb M, et al. Broad immunogenicity of a multigene, multiclade HIV-1 DNA vaccine boosted with heterologous HIV-1 recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(10):1482–90. doi: 10.1086/592507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Expansion of Use of Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine (FluMist) to Children Aged 2–4 Years and Other FluMist Changes for the 2007–08 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(46):1217–9. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Manzoli L, Schioppa F, Boccia A, Villari P. The efficacy of influenza vaccine for healthy children: a meta-analysis evaluating potential sources of variation in efficacy estimates including study quality. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(2):97–106. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000253053.01151.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Belshe RB, Gruber WC, Mendelman PM, Cho I, Reisinger K, Block SL, et al. Efficacy of vaccination with live attenuated, cold-adapted, trivalent, intranasal influenza virus vaccine against a variant (A/Sydney) not contained in the vaccine. J Pediatr. 2000;136(2):168–75. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(00)70097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Halloran ME, Piedra PA, Longini IM, Jr, Gaglani MJ, Schmotzer B, Fewlass C, et al. Efficacy of trivalent, cold-adapted, influenza virus vaccine against influenza A (Fujian), a drift variant, during 2003–2004. Vaccine. 2007;25(20):4038–45. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wareing MD, Tannock GA. Route of administration is the prime determinant of IgA and IgG2a responses in the respiratory tract of mice to the cold-adapted live attenuated influenza A donor strain A/Leningrad/134/17/57. Vaccine. 2003;21(23):3097–100. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jin H, Manetz S, Leininger J, Luke C, Subbarao K, Murphy B, et al. Toxicological evaluation of live attenuated, cold-adapted H5N1 vaccines in ferrets. Vaccine. 2007;25(52):8664–72. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Betts RF, Douglas RG, Jr, Maassab HF, DeBorde DC, Clements ML, Murphy BR. Analysis of virus and host factors in a study of A/Peking/2/79 (H3N2) cold-adapted vaccine recombinant in which vaccine-associated illness occurred in normal volunteers. J Med Virol. 1988;26(2):175–83. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890260209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Murphy BR, Holley HP, Jr, Berquist EJ, Levine MM, Spring SB, Maassab HF, et al. Cold-adapted variants of influenza A virus: evaluation in adult seronegative volunteers of A/Scotland/840/74 and A/Victoria/3/75 cold-adapted recombinants derived from the cold-adapted A/Ann Arbor/6/60 strain. Infect Immun. 1979;23(2):253–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.2.253-259.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Webster RG. Original antigenic sin in ferrets: the response to sequential infections with influenza viruses. J Immunol. 1966;97(2):177–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fazekas de SG, Webster RG. Disquisitions of Original Antigenic Sin. I. Evidence in man. J Exp Med. 1966;124(3):331–45. doi: 10.1084/jem.124.3.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fazekas de SG, Webster RG. Disquisitions on Original Antigenic Sin. II. Proof in lower creatures. J Exp Med. 1966;124(3):347–61. doi: 10.1084/jem.124.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Powell TJ, Strutt T, Reome J, Hollenbaugh JA, Roberts AD, Woodland DL, et al. Priming with cold-adapted influenza A does not prevent infection but elicits long-lived protection against supralethal challenge with heterosubtypic virus. J Immunol. 2007;178(2):1030–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eichelberger M, Golding H, Hess M, Weir J, Subbarao K, Luke CJ, et al. FDA/NIH/WHO public workshop on immune correlates of protection against influenza A viruses in support of pandemic vaccine development, Bethesda, Maryland, US, December 10–11, 2007. Vaccine. 2008;26(34):4299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rimmelzwaan GF, McElhaney JE. Correlates of protection: Novel generations of influenza vaccines. Vaccine. 2008;26S:D41–D44. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Plotkin SA. Vaccines: correlates of vaccine-induced immunity. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(3):401–9. doi: 10.1086/589862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baras B, Stittelaar KJ, Simon JH, Thoolen RJ, Mossman SP, Pistoor FH, et al. Cross-Protection against Lethal H5N1 Challenge in Ferrets with an Adjuvanted Pandemic Influenza Vaccine. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(1):e1401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Potter CW, Jennings R, McLaren C, Edey D, Stuart-Harris CH, Brady M. A new surface-antigen-adsorbed influenza virus vaccine. II. Studies in a volunteer group. J Hyg (Lond) 1975;75(3):353–62. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400024414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Potter CW, Jennings R, Phair JP, Clarke A, Stuart-Harris CH. Dose-response relationship after immunization of volunteers with a new, surface-antigen-adsorbed influenza virus vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1977;135(3):423–31. doi: 10.1093/infdis/135.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.La Gruta NL, Turner SJ, Doherty PC. Hierarchies in cytokine expression profiles for acute and resolving influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses: correlation of cytokine profile and TCR avidity. J Immunol. 2004;172(9):5553–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. IgG1 antibody responses after vaccination of BALB/cJ mice with DNA, LAIV, or DNA + LAIV. Influenza-reactive antibodies of the IgG1 isotype were detected 14 days after tertiary exposure to plasmid DNA indicated on the x-axis, or 21 days after exposure to LAIV (107 TCID50) indicated on the x-axis. Reactivity was detected using HK68/SY- (A), VI75/SY- (B), or LE86/SY- (C) coated plates. The individual bars in the graphs represent the mean ± standard deviation for the following number of mice per group for DNA: vehicle, n = 82; HK68, n = 70; VI75, n = 70; LE86, n = 69; and HK68/VI75/LE86, n = 85. The individual bars in the graphs represent the mean ± standard deviation for the following number of mice per group for pHW2000 + LAIV (LAIV): HK68/HKts, n = 3; VI75/HKts, n = 5; LE86/HKts, n = 5; and HK68/HKts + VI75/HKts + LE86/HKts, n = 4. The individual bars in the graphs represent the mean ± standard deviation for the following number of mice per group for HK68/VI75/LE86 + LAIV (DNA + LAIV): HK68/HKts, n = 16; VI75/HKts, n = 19; LE86/HKts, n = 20; and HK68/HKts + VI75/HKts + LE86/HKts, n = 17. Responses to both LAIV alone and DNA + LAIV were significantly greater (p < 0.05 by ANOVA) than corresponding responses to DNA alone for all groups measured; there were no statistically significant differences between LAIV and DNA + LAIV groups.

Figure S2. Dose response for LAIV expressing HK68 or LE86 HA. BALB/cJ mice (n = 5 per group) were inoculated with 104–107 TCID50 (33°C) LAIV expressing HK68 HA or LE86 HA, and weights are reported as the mean percent initial body weight for the group (A). Influenza-reactive antibodies present in sera 21 days after inoculation were detected using HI (B). For each group used in sera HI titer analyses, n = 5, with the exception of the group inoculated with 107 TCID50 HK68/HKts (n = 3).

Figure S3. Responses of C57BL/6 mice to inoculation with HK68/HKwt (n = 5) or HK68/HKts (n = 5). Mice were inoculated with 106 TCID50 (33°C) HK68/HKwt or HK68/HKts, and weights are reported as the mean percent initial body weight for each group(A). Influenza-reactive humoral immune response, as measured using HI, microneutralization, and isotype-specific ELISA are reported (B). Influenza peptide-specific T cell responses present in the BAL and spleen are reported as the total number of cells specific for the peptides indicated on the x-axis (C) and the percent of the peptide-specific cells that were TNF-α/IFN-γ positive (D). The percent of cells that are TNF-α/IFN-γ positive is in part a measure of cell quality and has been associated with the efficacy of memory responses [76].