Abstract

Excessive reactive oxygen species play a key role in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy, but to what extent these result from increased generation, impaired antioxidant systems, or both is incompletely understood. Here, we report the expression, localization, and activity of the antioxidant thioredoxin and its endogenous inhibitor thioredoxin interacting protein (TxnIP) in vivo and in vitro. In normal human and rat kidneys, expression of TxnIP mRNA and protein was most abundant in the glomeruli and distal nephron (distal convoluted tubule and collecting ducts). In contrast, thioredoxin mRNA and protein localized to the renal cortex, particularly within the proximal tubules and to a lesser extent in the distal nephron. Induction of diabetes in rats increased expression of TxnIP but not thioredoxin mRNA. Kidneys from patients with diabetic nephropathy had significantly higher levels of TxnIP than control kidneys, but thioredoxin expression did not differ. In vitro, high glucose increased TxnIP expression in mesangial, NRK (proximal tubule), and MDCK (distal tubule/collecting duct) cells, and decreased the expression of thioredoxin in mesangial and MDCK cells. Knockdown of TxnIP with small interference RNA suggested that TxnIP mediates the glucose-induced impairment of thioredoxin activity. Knockdown of TxnIP also abrogated both glucose-induced 3H-proline incorporation (a marker of collagen production) and oxidative stress. Taken together, these findings suggest that impaired thiol reductive capacity contributes to the generation of reactive oxygen species in diabetes in a site- and cell-specific manner.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated as a normal by-product of aerobic metabolism. Their presence leads to the oxidative modification of macromolecules including proteins, DNA, and lipids that impair function and contribute to physiologic aging.1 In addition, there is an evolving consensus that excessive bioavailability of ROS, referred to as oxidative stress, may be a major contributor to a number of chronic disease processes, including diabetes1 and diabetic nephropathy (DN) in particular.2 Indeed, it was proposed that the increased glycolytic flux during hyperglycemia gives rise to excessive superoxide production, resulting in oxidative stress and tissue injury that ultimately lead to the long-term complications of diabetes.3

To counteract the potential injurious effects of oxidative stress, mammalian cells have a wide array of antioxidant defense systems that remove ROS, repair oxidized molecules, and target those that have been irretrievably damaged for degradation. The sulfur-containing amino acid residues cysteine and methionine are especially sensitive to oxidative stress, even in the setting of mild ROS exposure4; however, although common, oxidation of the sulfydryl groups on these amino acids is unique in that oxidative changes can be enzymatically repaired by a number of highly expressed thiol-reducing systems that include the thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems.5

During the reduction of disulphide groups, thioredoxin (Trx) itself becomes oxidized, requiring reduction by thioredoxin reductase to restore its activity.6 In addition to this redox process, the activity of thioredoxin is modulated by an endogenous inhibitor, thioredoxin interacting protein (TxnIP). This small, 38–amino acid protein, also known as thioredoxin-binding protein-2 (TBP-2), was originally named vitamin D upregulated protein-1 (VDUP-1), after its identification in HL-60 cells after 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 stimulation.7 More recently, using a microarray-based approach, TxnIP was also found to be upregulated by high glucose, initially in fibroblasts8 but later also reported in mesangial,9,10 proximal tubular,11 vascular smooth muscle,12 and islet β cells.13,14

Indicative of its potential importance, overexpression of thioredoxin in transgenic mice was shown to attenuate the development of DN15; however, despite the propitious nature of these experimental findings, several key issues remain unanswered. For instance, although high glucose augments TxnIP expression, its effects on Trx are uncertain. This is particularly relevant with regard to the antioxidant activity of the thioredoxin system because if high glucose also induces a parallel increase in Trx expression, then any detrimental effects of TxnIP overexpression would be negated. Moreover, the site-specific distribution and relative abundance of both TxnIP and Trx have not yet been determined in the in vivo setting in DN; neither has its relevance to human disease. Accordingly, in this study, we first sought to examine the localization and expression of Trx and TxnIP in a rodent model and then to investigate their expression in human disease and to determine the contribution of these changes to oxidative stress and extracellular matrix production.

RESULTS

Animal Characteristics

Long-Term Diabetes.

Renal expression and localization of TxnIP and Trx were studied in female heterozygous TGR(mRen-2)27 rats made diabetic with streptozotocin (STZ) for 16 wk. Plasma glucose and hemoglobin A1c confirmed the presence of diabetes in all STZ-treated rats. Albumin excretion rate was higher in diabetic compared with nondiabetic animals (Table 1) as was urinary 8-hydroxy-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), a marker of oxidative stress (Table 1). Diabetic TGR(mRen-2)27 rats showed histologic evidence of renal injury with glomerulosclerosis (Table 1), tubulointerstitial fibrosis (Table 1), and arteriolar hyalinosis.

Table 1.

Animal characteristics of control and diabetic TGR(mRen-2)27 ratsa

| Characteristic | Control | Diabetic |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | 289 ± 17 | 271 ± 6 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 204 ± 14 | 201 ± 7 |

| Plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 6.1 ± 0.2 | 32.3 ± 0.4b |

| HbA1c (%) | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 10.7 ± 0.5b |

| AER (mg/d) | 0.89 ×/÷ 1.30 | 3.68 ×/÷ 1.40c |

| 8-OHdG (ng/24 h) | 290 ± 29 | 1664 ± 161b |

| Glomerulosclerosis index (AU) | 0.96 ± 0.05 | 1.33 ± 0.03c |

| Tubulointerstitial fibrosis (% area) | 0.860 ± 0.004 | 5.240 ± 1.490d |

Data are means ± SEM except albumin excretion rate (AER), which is expressed as geometric mean ×/÷ tolerance factor. AU, arbitrary units; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; SBP, systolic BP.

P < 0.0001.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.05.

Short-Term Diabetes.

To investigate the time course of diabetes-associated changes, we also studied animals with 3 wk of STZ-induced diabetes, before the development of fibrosis and albuminuria. When compared with age-matched nondiabetic controls, urinary 8-OHdG was increased in diabetic rats (urinary 8-OHdG [ng/24 h]: control 559 ± 50; diabetes 1585 ± 140; P < 0.0001).

TxnIP and Trx Localization in Rat and Human Kidneys

TxnIP.

33P in situ hybridization demonstrated TxnIP gene expression in both cortex and medulla of rat kidneys (Figure 1). Light microscopic examination of emulsion-dipped sections revealed that TxnIP mRNA was most abundantly expressed in the glomeruli and in the distal nephron in rat kidney (Figure 2, A, B, D, and E), with a similar distribution of TxnIP protein confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

In situ hybridization for TxnIP and Trx in control and diabetic TGR(mRen-2)27 rat kidneys. (A through D) 33P autoradiographs for TxnIP from control (A) and diabetic TGR(mRen-2)27 (B) rats and for Trx from control (C) and diabetic TGR(mRen-2)27 (D) rats. Magnitude of transcript expression is indicated semiquantitatively in the pseudocolorized computer images (blue, nil; green, low; yellow, moderate; red, high). TxnIP mRNA was localized predominantly to the outer cortex and medulla in control rats, with increased expression noted in a similar distribution in diabetic animals. Trx expression showed a predominance within the cortex that was unaffected by diabetes. Magnification, ×4.

Figure 2.

(A through F) Representative photomicrographs of 33P in situ hybridization for TxnIP (A, B, D, and E) and Trx (C and F) from control (A through C) and diabetic (D through F) TGR(mRen-2)27 rats. (G and H) Sense control from nondiabetic TGR(mRen-2)27 rats. TxnIP mRNA is noted predominantly in glomeruli and distal nephron structures. Trx mRNA is present in both glomerular and tubulointerstitial compartments, although particularly prominent in proximal tubules. Magnification, ×400.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry for TxnIP in diabetic TGR(mRen-2)27 rat kidney confirming protein expression primarily within the glomerulus and distal nephron. Magnification, ×400.

Digoxigenin in situ hybridization for TxnIP mRNA in human nephrectomy tissue showed the same distribution of TxnIP mRNA as seen in rat kidneys (Figure 4A). To determine more precisely the site-specific distribution of TxnIP in the distal nephron, we performed serial sectioning that combined digoxigenin in situ hybridization with immunostaining for the nephron segment–specific markers aquaporin 2 (AQP2; collecting duct) and thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl co-transporter (TSC; distal convoluted tubule). With this technique, abundant TxnIP transcript was noted in both collecting ducts and distal convoluted tubules (Figure 4, A through C).

Figure 4.

(A through F) Localization of TxnIP (A through C) and Trx (D through F) in human kidney tissue using nephron segment-specific markers (thiazide-sensitive NaCl co-transporter [B and E] to identify distal convoluted tubules [labeled D in figure] and AQP2 [C and F] to stain collecting ducts [labeled CD in figure]). (A) TxnIP was identified by in situ hybridization and was expressed in glomeruli, distal convoluted tubules, collecting ducts, and also the endothelium of arterioles (arrow). (D) Trx was labeled by immunohistochemistry and was expressed throughout the kidney cortex with greater abundance in proximal tubules (labeled P in figure) than collecting ducts, distal convoluted tubules, or glomeruli. Magnification, ×160.

Trx.

Contrasting the distribution of TxnIP, Trx gene expression was confined to the cortex with expression levels higher in the inner compared with the outer region (Figure 1) and with light microscopy of emulsion-dipped sections showing Trx transcript ubiquitously expressed in all structures within the kidney cortex of the rat (Figure 2, C and F). Similar findings were noted in human kidney biopsies in which immunostaining for Trx confirmed widespread expression of the protein, particularly within the proximal tubules and to a lesser extent in distal convoluted tubules (TSC positive) and collecting ducts (AQP2 positive; Figure 4, D through F).

Experimental DN

TxnIP and Trx in Long-Term Diabetes.

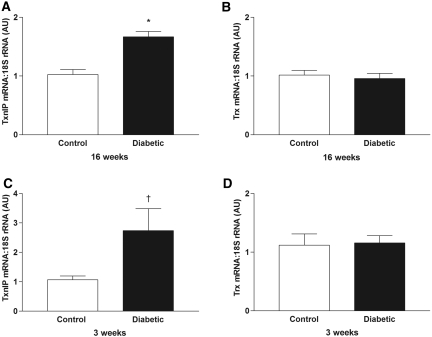

Examination of kidney in situ hybridization autoradiographs from animals with long-term diabetes (16 wk) suggested that TxnIP expression was increased compared with control TGR(mRen-2)27 rats (Figure 1). To investigate this further, we performed quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR (RTQ-PCR) on these tissues and confirmed an increase in TxnIP mRNA with diabetes. In contrast, no difference in Trx expression was noted between diabetic and nondiabetic animals (Figure 5, A and B).

Figure 5.

(A through D) RTQ-PCR for TxnIP (A and C) and Trx (B and D) in kidneys from control and diabetic TGR(mRen-2)27 rats after diabetes for 16 wk (A and B) and 3 wk (C and D). AU, arbitrary units (values normalized to the control groups). *P < 0.001; †P < 0.05.

To determine whether the changes in TxnIP mRNA associated with diabetes reflected changes in the cortex and/or medulla, we performed quantitative autoradiography for TxnIP and Trx. TxnIP mRNA was significantly increased in the cortex but not the medulla of diabetic animals (TxnIP IOD [nCi/g] × proportional area [PA] cortex: control 82.7 ± 10.9, diabetes 131.5 ± 13.0 [P < 0.02]; medulla: control 173.1 ± 37.4, diabetes 189.0 ± 30.1 [P = 0.74]). Within the kidney medulla, although no overall difference in the magnitude of TxnIP expression was found between control and diabetic animals, TxnIP mRNA seemed to be notably increased within the region of the corticomedullary junction in diabetic animals (Figure 1).

For Trx, no difference was noted between control and diabetic animals by quantitative in situ hybridization, with expression confined to the cortex in both groups (Trx IOD [nCi/g] × PA cortex: control 52.8 ± 9.8, diabetes 57.6 ± 8.7; P = 0.73).

TxnIP and Trx in Short-Term Diabetes.

To determine whether changes in renal TxnIP expression in diabetes were confined to animals with long-term diabetes, we also examined kidney tissue from animals with short-term (3 wk) disease. As seen with longer duration diabetes, TxnIP mRNA was significantly increased after 3 wk, with no change in Trx indicating that upregulation of TxnIP transcript expression is an early feature of experimental diabetes (Figure 5, C and D). We did not observe a relationship between TxnIP and Trx expression and any areas of focal injury in diabetic TGR(mRen-2)27 rats.

TxnIP and Trx mRNA in Human DN

Having found increased TxnIP mRNA in experimental diabetes, we determined whether expression was also increased in human disease. Biopsy tissue from six patients with thin membrane nephropathy (TMN) was used to represent control tissue. Sufficient good-quality RNA (OD260/280 >1.5) was available to determine expression of TxnIP in four samples and Trx in three samples (with one sample used for both genes of interest). The clinical characteristics of patients with TMN are shown in Table 2. Two patients had hypertension, and both were treated with calcium channel blockers. None of the patients were treated with agents that block the renin-angiotensin system, and none of the patients had diabetes. The clinical characteristics of patients with DN were previously reported.16 When compared with control tissue, TxnIP mRNA levels were seven-fold higher in DN biopsies (n = 27) with no difference in Trx expression detected (Figure 6, A and C).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients with TMN from whom renal biopsy tissue was obtaineda

| Biopsy | Age (yr) | Gender | Serum Creatinine (μmol/L) | Urine Protein (g/d) | Urinary RBC (×106/L) | Hypertension |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1b,c | 27 | F | 65 | 0.00 | 89 | No |

| 2b | 49 | F | 95 | 0.00 | 65 | No |

| 3b | 61 | M | 87 | 0.00 | 65 | No |

| 4b | 57 | M | 96 | 0.15 | 50 | Yes |

| 5c | 62 | M | 118 | 0.32 | 38 | Yes |

| 6c | 44 | F | 84 | 0.00 | 45 | No |

RBC, red blood cells.

Biopsies used to determine TxnIP gene expression.

Biopsies used to determine Trx expression.

Figure 6.

(A through D) RTQ-PCR for TxnIP (A and B) and Trx (C and D) in biopsy samples from patients with DN and either TMN or nephrectomy (Nx) control. Values normalized to the control groups.

To confirm the finding of increased TxnIP expression in human DN, we also performed RTQ-PCR in mRNA extracted from renal biopsies from six additional patients with DN and compared them with normal kidney tissue taken from the opposite pole of kidneys from patients undergoing nephrectomy for tumor (n = 6). These experiments confirmed increased TxnIP expression in human DN (Figure 6B). In this cohort, Trx mRNA in diabetic biopsies showed a trend to be lower than in control nephrectomy tissue (Figure 6D), although, given the site-specific distribution of Trx within the kidney, this may reflect the difference in specimen types.

Effect of High Glucose on TxnIP and Trx Expression in Cultured Cells

In light of the site-specific differences in distribution of TxnIP and Trx mRNA, we determined the effect of high glucose on gene expression in three different cell types, with distinct phenotypic features representative of different nephron segments. Exposing cultured cells to 25 mM glucose for 48 h caused an increase in TxnIP expression in mesangial, NRK (proximal tubule), and MDCK (distal tubule/collecting duct) cells compared with 5.6 mM glucose (Figure 7). In contrast, incubation of cells in the presence of 25 mM glucose caused a decrease in Trx mRNA in mesangial and MDCK cells and did not have a significant effect in NRK cells (Figure 7). Mannitol had no effect on TxnIP or Trx expression.

Figure 7.

RTQ-PCR for TxnIP (A, C, and E) and Trx (B, D, and F) in cultured mesangial (A and B), MDCK (C and D) and NRK cells (E and F) incubated in the presence of 5.6 or 25.0 mM glucose or 5.6 mM glucose + 19.4 mM mannitol. Mean of three to five experiments. *P < 0.01 versus 5.6 mM glucose, †P < 0.0001 versus 5.6 mM glucose.

TxnIP Interference and Trx Activity, Oxidative Stress, and Extracellular Matrix

Having demonstrated increased TxnIP expression in experimental and human DN and in response to high glucose, we went on to determine the effect of silencing it with small interference RNA (siRNA).

Trx Activity.

As would be expected from the increase in TxnIP (but not Trx) mRNA with high glucose, the biologic activity of Trx, as assessed by insulin disulfide reduction assay, was reduced after 48 h of exposure to high glucose. Preincubation of mesangial cells with TxnIP siRNA attenuated the effect of high glucose on Trx activity, whereas scrambled siRNA was without effect (Figure 8, A and B). A similar reduction in Trx activity was also observed with TxnIP siRNA in NRK cells (Figure 8C). A reduction in TxnIP protein expression with siRNA was confirmed in cultured mesangial cells by immunoblotting (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 8.

Effect of TxnIP siRNA in mesangial and NRK cells. (A) Preincubation of mesangial cells with siRNA against TxnIP ameliorated the increase in TxnIP mRNA induced by 25 mM glucose. (B and C) Trx activity in mesangial cells (B) and NRK cells (C), determined by insulin disulfide reduction assay, was reduced in the presence of 25 mM glucose. Preincubation of cells with TxnIP siRNA completely abrogated the decrease in Trx activity. Scrambled siRNA was without effect. Mean of three experiments. Values normalized to 5.6 mM glucose. *P < 0.001 versus 5.6 mM glucose; †P < 0.001 versus 25 mM glucose (control); ‡P < 0.001 versus TxnIP siRNA; §P < 0.01 versus TxnIP siRNA.

TxnIP siRNA Abrogates Oxidative Stress and 3H-Proline Incorporation.

Mesangial and NRK cells incubated in high glucose showed evidence of both oxidative stress, as demonstrated by increased CFDA fluorescence, and increased 3H-proline incorporation, suggestive of increased collagen production. Preincubation of mesangial cells and NRK cells with TxnIP siRNA abrogated both the high glucose–induced oxidative stress and 3H-proline incorporation, with no effect of scrambled siRNA (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

CFDA fluorescence and 3H proline incorporation in cultured mesangial and NRK cells. (A through D) Representative flow cytometry histograms of CFDA fluorescence (CFDA-A) in cultured mesangial cells incubated with 5.6 mM glucose (A), 25 mM glucose (B), 25 mM glucose + TxnIP siRNA (C) and 25 mM glucose + scrambled siRNA (D). (E and F) CFDA fluorescence in cultured mesangial (E) and NRK (F) cells. (G and H) 3H proline incorporation in cultured mesangial (G) and NRK (H) cells. Mean of three experiments. *P < 0.001 versus 5.6 mM glucose, †P < 0.01 versus 25 mM glucose (control), ‡P < 0.001 versus TxnIP siRNA, §P < 0.001 versus 25 mM glucose (control).

DISCUSSION

Although defense against oxidative stress is required by all mammalian cells, expression of Trx and TxnIP in the kidney was not ubiquitous. Furthermore, although Trx and TxnIP are viewed as closely interacting molecular entities, their site-specific patterns of distribution were quite different. Particularly striking was the abundance of medullary TxnIP gene expression in the absence of detectable Trx mRNA. Even within the cortex, the pattern of distribution for these two transcripts was dissimilar, with Trx most abundant in the inner cortex and in proximal tubules, whereas TxnIP was most easily detected in the distal nephron in the outer cortex. Indeed, not only were their patterns of distribution different in vivo but also the response to high glucose in vitro varied according to cell type. In this study, three cell types were used: Sprague-Dawley rat mesangial cells, normal rat kidney proximal tubular epithelial cells (NRK), and a canine cell line with a distal tubular/collecting duct phenotype (MDCK). Whereas high glucose increased TxnIP mRNA in all three cell types, Trx was reduced in mesangial and MDCK cells but unchanged in NRK cells. This latter finding in conjunction with the substantial contribution of proximal tubules to the mass of the kidney cortex may explain why no change in cortical Trx mRNA was found in the experimental setting, contrasting the in vivo changes in TxnIP expression.

Oxidative stress is viewed as playing a critical role in the pathogenesis of both the micro- and macrovascular complications of diabetes.3,17 This paradigm is based on the knowledge that increased intracellular glucose leads to the overproduction of superoxide by the mitochondrial electron-transport chain and increased formation of secondary ROS.3 The activity of antioxidant systems is accordingly an important defense against ROS-associated cell injury. For instance, in nondiabetic animals in which increased ROS are formed as a consequence of ischemia reperfusion injury in the heart18 and in response to photic injury in the retina,19 activity of the thioredoxin system is increased and plays an important role in tissue protection; however, in contrast to these adaptive responses, this study shows that the diabetic context is characterized by a paradoxic reduction in the activity of the thioredoxin system as a consequence of overexpression of its inhibitor TxnIP.

In the kidneys of diabetic rats, TxnIP mRNA was most notably increased in the cortex and also the corticomedullary junction within the outer stripe of the outer medulla. This region of the kidney contains the medullary rays that receive oxygen-poor blood from the venous vasa recta20 and seems to be particularly vulnerable to ischemia in the diabetic setting.21 Indeed, like other genes that are overexpressed at the outer stripe of the outer medulla in the diabetic kidney, such as TGF-β inducible gene-H3 (βig-H3),22 TxnIP is also increased by hypoxia23 as well as by high glucose, suggesting that hyperglycemia and hypoxia together contribute to TxnIP overexpression in the diabetic kidney.

Changes in TxnIP expression were associated not only with increased oxidative stress but also with excessive matrix production, a key factor in the evolution of the glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis that characterize diabetic kidney disease. The findings are consistent with a previous report that TxnIP mRNA is upregulated in the kidneys of STZ-diabetic mice24 and complement a study that demonstrated both an increase in TxnIP expression in muscle biopsies of patients with type 2 diabetes and a role for the protein in regulating glucose uptake.25

In contrast to the irreversible chemical transformations that occur with most other biologic molecules, oxidation of the amino acid cysteine is reversible. Reduction of the resultant disulphide bond to two sulfydryl groups is readily achieved by thioredoxin through binding via its active Cys-Gly-Pro-Cys site.6,26 The activity of Trx is functionally regulated by an endogenous inhibitor TxnIP,27,28 which impedes its activity by interacting directly with its catalytic site.28 In this study, we found that attenuating the diabetes-associated increase in TxnIP by siRNA markedly reduced CFDA fluorescence, suggesting that overexpression of TxnIP is a major contributor to hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress in kidney cells.

The elaboration of increased quantities of extracellular matrix is a hallmark of the diabetic state that has been shown to have a pivotal role in the development of renal dysfunction in DN.29 In this study we have also shown that 3H-proline incorporation, an estimate of collagen production, is induced by high glucose and can be abrogated by siRNA-mediated knockdown of TxnIP overexpression. In these studies, the in vitro effects of high glucose and TxnIP siRNA were assessed only at a single time point, and this may explain the relative effects of TxnIP siRNA on the magnitude of change in gene and protein expression and Trx activity observed in mesangial cells.

In both experimental animals and humans, early diabetes is characterized by a hypertrophic phase with glomerular hyperfiltration and normal kidney structure.30 In some patients and some experimental animal models, renal changes evolve further to a later phase of overt DN with proteinuria, declining renal function, glomerulosclerosis, and tubulointerstitial fibrosis.30 We compared biopsy tissue from patients with DN and TMN and nephrectomy tissue, taking advantage of recent developments in molecular biology that enable the reliable assessment of gene expression in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded archival tissues.31 This study thus differs from a previous report9 in several ways that include both the use of human tissue from patients with established DN and the determination of the site specificity of expression in the kidneys of rodents with advanced DN.

In summary, high glucose leads to an impairment of the Trx system, as a consequence of multiple changes that include increased expression of the endogenous Trx inhibitor, TxnIP, and reduced Trx activity. These findings implicate transcriptional changes as a key component to the accumulation of ROS in diabetes. The recent description of a specific DNA enzyme to downregulate TxnIP expression in the postmyocardial infarction setting suggests the potential to also modulate this pathway in vivo in diabetes.32

CONCISE METHODS

Animals

Study 1.

Eight-week-old female, heterozygous (mRen-2)27 rats (St. Vincent's Hospital Animal House, Melbourne, Australia) were assigned to receive either 55 mg/kg STZ (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) diluted in 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 4.5; diabetic n = 10) or citrate buffer alone (nondiabetic n = 9) by tail-vein injection after an overnight fast. All rats were maintained for 16 wk after STZ injection. They received normal rat chow, drinking water ad libitum and were housed in a stable environment maintained at 22 ± 1°C with a 12-h light/dark cycle.

Each week, rats were weighed and their blood glucose levels were measured (Accu-check Advantage II Blood Glucose Monitor; Roche Diagnostics, Castle Hill, NSW, Australia), and only STZ-treated animals with blood glucose >15 mmol/L were considered diabetic. Every 4 wk, systolic BP was determined in preheated conscious rats via tail-cuff plethysmography33 using a noninvasive BP controller and Powerlab (AD instruments, NSW, Australia). Hemoglobin A1c was measured by HPLC at the end of the study. Diabetic rats received a daily injection of insulin (2 to 4 U intraperitoneally; Humulin NPH; Eli Lilly and Co., Indianapolis, IN) to reduce mortality and to promote weight gain. For estimation of urine albumin excretion, rats were individually housed in metabolic cages for 24 h after 2 to 3 h of habituation. Animals continued to have free access to tap water and standard laboratory diet during this period. After 24 h in metabolic cages, an aliquot of urine (5 ml) was collected from the 24-h urine sample and stored at −20°C for subsequent analysis. Urine albumin excretion was determined by double-antibody RIA as previously reported.34 Urinary 8-OHdG was determined by ELISA (Oxis International Inc., Foster City, CA). Experimental procedures adhered to the guidelines of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia's Code for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes and were approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of St. Vincent's Hospital.

Study 2.

To determine the time course for TxnIP and Trx expression, we also performed real-time PCR on kidney homogenates after 3 wk of diabetes. For these experiments male heterozygous TGR (mRen-2)27 rats received a tail-vein injection of STZ (diabetic n = 10) or citrate buffer alone (control n = 8) as described already and were followed for 21 d.

Tissue Preparation

Rats were anesthetized (Nembutal 60 mg/kg body wt intraperitoneally; Boehringer-Ingelheim, North Ryde, NSW, Australia). The left renal artery was clamped, and the kidney was removed, decapsulated, weighed, and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen before storage at −80°C for subsequent molecular biologic analysis. The right renal artery was clamped, and the kidney was removed, decapsulated, sliced transversely, and immersed in 10% neutral buffered formalin overnight. Tissues were routinely processed, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned.

Glomerulosclerosis and Tubulointerstitial Fibrosis

Glomerulosclerosis index and tubulointerstitial fibrosis were determined in rat kidney sections stained with periodic acid Schiff and Masson modified trichrome, respectively. Glomerulosclerosis index was determined using a semiquantitative method, and tubulointerstitial fibrosis was estimated using computer-assisted image analysis as described previously.35

33P In Situ Hybridization

Synthesis of riboprobes and in situ hybridization were performed as described previously.36 Briefly, 33P-labeled antisense RNA probes for TxnIP and Trx were generated by in vitro transcription (Promega, Madison, WI) from linearized templates. Primers were designed using Oligo 6 primer design software (Molecular Biology Insight, Cascade, CO). Two rat TxnIP probes were generated by RT-PCR, using rat kidney cDNA as template, to span the regions 1481 through 2004 (forward primer CGCCTCTGACTCCACA, reverse primer GCAAATAACGGGTTCTC) and 2008 through 2384 (forward primer ACCCGTTATTTCCGTGTGACTC, reverse primer TCCATCAGTGTTAGGGCATCTC) of the rat TxnIP sequence (accession no. NM_001008767). Similarly, two rat Trx probes were generated to span the regions 46 through 212 (forward primer CTGCCGAAACTCGTGTG, reverse primer GAAAGAAGGGCTTGATCATT) and 206 through 364 (forward primer CCCTTCTTTCATTCCCTC, reverse primer GTTAGCACCAGAGAACTCCC) of rat Trx (accession no. NM_053800). Purified riboprobe length was adjusted to approximately 150 bases by alkaline hydrolysis. In situ hybridization was performed on 4-μm-thick sections of formaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded kidney tissue. Briefly, tissue sections were dewaxed in histolene, rehydrated in graded ethanol, and microwaved in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) on medium-high (600 to 700 W) for 6 + 5 min.37 Sections were washed in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, and washed again in phosphate buffer and milliQ water. After equilibration in P buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.2] and 5 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]), slides were incubated with 125 μg/ml Pronase E (Sigma) in P buffer (pH 7.2), refixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, rinsed in milliQ water, dehydrated in 70% ethanol, and air dried.

Hybridization of the riboprobe to the pretreated tissue was performed overnight at 60°C in 50% formamide-humidified chambers, as described previously.38 Sense probes were used on an additional set of tissue sections as controls for nonspecific binding. After hybridization, slides were washed, incubated with RNase A, dehydrated in graded ethanol, air dried, and exposed to Kodak Biomax MR autoradiographic film (Kodak, Rochester, NY) for 3 d. Subsequently, slides were dipped in Amersham LM-1 nuclear emulsion (Buckinghamshire, Amersham, UK), stored in a light-free box with desiccant at 4°C for 3 wk and developed in Ilford Phenisol, fixed with Ilford Hypam (Ilford, Mobberley, UK), and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for examination under light microscopy.

Digoxigenin In Situ Hybridization

Digoxigenin in situ hybridization was performed in human kidney nephrectomy tissue using a cocktail of two riboprobes for human TxnIP mRNA. Riboprobes for human TxnIP were generated using cultured human mesangial cell RNA with primer sequences as follows: Human TxnIP-1 forward primer TTCATGCCACCACCGACTTA and reverse primer AACCTTGAAAAGCTTACGCCAG (accession no. XM_002093, spanning region 1427 through 1840) and human TxnIP-2 forward primer TGCCCCACCAAAGGTCTTAA and reverse primer TGGCAGTATTTGGAGGTTCTGA (accession no. XM_002093, spanning region 2151 through 2557). The cDNAs were inserted into pGEM-T easy, and sequencing was performed to confirm identity of the sequences and the orientation of the sequences in the vector. Templates for the preparation of riboprobes were made by restriction enzyme digestion with Sal 1 and runoff transcripts incorporating DIG-UTP were made using T7 RNA polymerase.

Briefly, 4-μm-thick sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded human kidney tissue were dewaxed, microwaved, and postfixed as described already. After rinsing in Tris/EDTA buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.2] and 5 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]), slides were incubated with 0.5 μg/ml proteinase K (Roche) in Tris/EDTA for 30 min at 37°C before inactivation of proteinase K in glycine 2 mg/ml for 5 min at room temperature. Tissues were then refixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and washed with 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer and milliQ water. Sections were prehybridized at 37°C for 1 h in hybridization buffer containing 50% formamide, 5× SSC, 2% blocking reagent (Roche), 0.1% lauroyl-sarcosine, and 0.02% SDS. Hybridization was performed overnight at 50°C in hybridization buffer containing the digoxigenin-labeled probe in 50% formamide-humidified chambers. Slides were washed in 2× SSC at 37°C for 15 min, treated with 150 μg/ml ribonuclease (RNase) A (Sigma), and washed again in graded SSC. The hybridized digoxigenin riboprobe was detected with alkaline phosphatase–coupled anti-digoxigenin antibody (Roche).

Quantitative Autoradiography

Quantitative in situ hybridization by autoradiographic film densitometry, which permits the assessment of gene expression equivalent to Northern blot analysis, was used to determine the magnitude of gene expression.39,40 In brief, film densitometry of autoradiographic images was performed by computer-assisted image analysis as previously reported41 using a microcomputer imaging device (Imaging Research, St. Catherine's, Ontario, Canada). Autoradiographic images were placed on a uniformly illuminating fluorescence light box (Northern Light Precision Luminator model C60; Imaging Research) and captured using a videocamera connected to an IBM AT computer with a 512 × 512-pixel array imaging board with 256 gray levels. The outline of either the kidney cortex or the medulla (excluding the papilla) was defined by interactive tracing. After appropriate calibration by constructing a curve of OD versus radioactivity, quantification of digitized autoradiographic images was performed using microcomputer imaging device software.

Biopsy Study

Renal tissue was obtained from biopsy samples stored from a study in which histology and clinical data were previously reported.16 In brief, patients with type 2 diabetes and evidence of proteinuria but no retinopathy underwent percutaneous needle biopsy of the kidney to assess renal histology. Of the reported cohort, 27 randomly selected biopsies that demonstrated classical changes of DN and the relevant clinical data were studied. Control tissue was obtained from six patients with TMN. To confirm findings from the initial biopsy studies, we also performed RTQ-PCR on kidney biopsies from six patients with DN and compared them with kidney tissue from patients who had undergone nephrectomy for tumor with tissue removed from the opposite pole (n = 6). Kidney tissue was formalin-fixed and embedded in paraffin before sectioning. All patients gave informed consent, and the study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The studies were approved by the Human Ethics Review Committee of the Alfred Group of Hospitals, Prahran, Australia.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry for TxnIP and Trx protein was performed in rat and human kidney, respectively, using polyclonal rabbit anti–VDUP-1 (Zymed, San Francisco, CA) and polyclonal rabbit anti-Trx1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), each diluted 1:100 in PBS. Identification of different segments of the distal nephron was performed with specific antisera in consecutively cut kidney sections. For identification of collecting ducts, sections were stained with anti-AQP2 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA),42,43 and distal convoluted tubules were identified with a rabbit polyclonal antibody to TSC (Chemicon, Temecula, CA).44,45 Immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously46 except that microwave antigen retrieval was not used on TxnIP-labeled sections. Incubation with PBS instead of primary antiserum served as the negative control. For secondary antibody labeling, sections were incubated with Envision+ System labeled polymer-horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). Finally, sections were labeled with Liquid Diaminobenzidine and Substrate Chromogen System (DakoCytomation) before counterstaining in Mayer's hematoxylin.

In Vitro Studies

To explore further the role of the diabetes-associated changes in TxnIP that we found in vivo, we examined the effects of high glucose on cultured Sprague-Dawley rat mesangial cells, NRK cells, and MDCK cells. Cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), streptomycin (100 g/ml), penicillin (100 U/ml), and 2 mM glutamine at 37°C in 95% air/5% CO2 as previously reported.47 Cells from passage 5 through 10 were cultured in either DMEM (which contains 5.6 mM glucose) or DMEM supplemented with an additional 19.4 mM glucose (final concentration of glucose 25 mM) for 48 h. Mannitol (19.4 mM) added to DMEM served as the osmotic control.

RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

Gene expression was determined in frozen rat kidney tissue, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded human biopsy tissue, and cultured cell extracts. Frozen rat kidney tissue, stored at −80°C, was homogenized (Polytron, Kinematica Gmbh, Littau, Switzerland), and total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Total RNA (4 μg) was treated with RQ1 DNAse (1 U/μl; Promega) to remove genomic DNA. RNA was extracted from human biopsies in paraffin blocks by the phenol-chloroform method.31 In brief, 4-μm sections were immersed in xylene; washed in 100% ethanol; resuspended in lysis buffer containing 10 mmol/L Tris/HCl (pH 8.0), 0.1 mmol/L EDTA (pH 8.0), 2% SDS (pH 7.3), and 500 μg/ml proteinase K; and incubated at 60°C. Water saturated phenol and chloroform (200 μl) was added to each sample before centrifugation for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed, and an additional chloroform/phenol extraction was performed followed by an additional chloroform extraction before precipitation in isopropanol. After washing, RNA was resuspended in RNase-free (DEPC) water and stored at −80°C. RNA was reverse-transcribed with 1 μl of random hexamers (2 μg/μl) and 8 μl of DEPC-treated water and incubated for 5 min at 70°C. After cooling on ice, 5 μl of 5× AMV reaction buffer, 2.5 μl of 10 mM dNTP mix, 0.5 μl of RNase inhibitor (40 U/μl; Roche), 0.5 μl of AMV reverse transcriptase (25 U/μl; Roche) and 4.5 μl of DEPC water were added. The reaction mixture was incubated for 60 min and the cDNA samples were stored at −20 °C until further analysis.

For in vitro experiments, RNA isolation and DNase treatment of cultured cell extracts was performed using RNAspin Mini (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). DNase-treated RNA (4 μg) was reverse-transcribed in a final volume of 25 μl using 0.5 μl AMV-RT (Roche) in the manufacturer's buffer containing 1 mmol/L dNTPs, 0.5 μl RNase inhibitor (Roche), and 2 μg random hexamers (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany).

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

Measurement of TxnIP and Trx gene expression was performed on an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. SYBR green chemistry was used for TxnIP and rat Trx, and a Taqman probe was used for human Trx. Sequence-specific primers were designed to span exon-exon boundaries using Primer Express 1.5 (Applied Biosystems). Primers were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, and fluorescence probes were obtained from Applied Biosystems. Ribosomal 18S with the fluorescence reporter dye [vic] on the 5′ end and a nonfluorescent quencher [MGB] on the 3′ end (Applied Biosystems) was used as the endogenous control. Primer and probe sequences were as follows: 18S forward TCGAGGCCCTGTAATTGGAA and reverse CCCTCCAATGGATCCTCGTT, probe AGTCCACTTTAAATCCTT; rat TxnIP forward CCGCTCGAATCGACAGAAAA, reverse CGGGCCACAATAGCTGCTTT; rat Trx, forward ACGTGGATGACTGCCAGGAT and reverse AGGTCGGCATGCATTTGACT; human TxnIP, forward GGCACCTGTGTCTGCTAAAA and reverse CGGGAACATGTATTCTCAAA; human Trx, forward GTCAGACTCCAGCAGCCAAGA and reverse TTATCACCTGCAGCGTCCAA, probe TGAAGCAGATCGAGAGCA; dog (MDCK cells) TxnIP, forward CAGCTCTGAAATGAGTTGGATAGATC, reverse CCATATAGCAAGGAGGAGCTTCTG; dog Trx, forward GTGCTCTGGTGAATGTTTTTG and reverse ACTGAGGAAACAAGCCTGAACTCT. Experiments were performed in triplicate (duplicate for human biopsy studies) and data analyses were performed using Applied Biosystems Comparative CT method.

siRNA-Mediated Gene Knockdown

Mesangial and NRK cells were transfected (Lipofectamine 2000; Invitrogen) with 100 pM siRNA for selectively silencing TxnIP (rACAGACUUCGGAGUACCUGdTT), as previously reported.12 Cells were transfected with TxnIP siRNA for 24 h, before supplementation of medium with 19.4 mM glucose (final concentration of glucose 25 mM) for an additional 48 h. Knockdown of gene expression was confirmed by quantitative PCR as indicated already. Scrambled RNAi was used as control.

Western Blotting

Mesangial cells were transfected with TxnIP siRNA for 24 h, before supplementation of the medium with 19.4 mM glucose for an additional 48 h as described already. Protein was isolated from cultured cell extracts, after washing in PBS, with Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) containing 1 mM PMSF. Protein concentration was determined by Bio-Rad DC Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). SDS-PAGE was performed after loading gels with 50 μg of protein. Immunoblotting on nitrocellulose membranes was performed with either polyclonal rabbit anti–VDUP-1 (Zymed, San Francisco, CA) at a concentration of 1 μg/ml or mouse monoclonal anti–β-actin (1:1000; Abcam). After incubation with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies (Bio-Rad), proteins were detected by the ECL system (Amersham). Densitometry of protein bands was performed using ImageJ 1.40 (National Institutes of Health: http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Thioredoxin Activity

To determine whether changes in TxnIP mRNA were associated with changes in the biologic action of this enzyme system, thioredoxin activity was measured using the insulin disulfide reduction assay, as described previously.48 Cultured mesangial and NRK cells were incubated with TxnIP siRNA or scrambled RNAi for 24 h before supplementation of the culture medium with an additional 19.4 mM glucose for 48 h as outlined already. For determination of thioredoxin activity, 40 μl of reaction mixture (200 μl of HEPES buffer, 40 μl of EDTA, 40 μl of NADPH, and 500 μl of insulin) was added to cellular protein extracts and incubated at 37°C for 20 min after the addition of 10 μl of bovine thioredoxin reductase (American Diagnostica, Greenwich, CT). The reaction was then terminated by adding 500 μl of stop buffer (0.4 mg/ml DTNB/6M guanidine HCl in 0.2 M Tris-HCl), after which absorption at 412 nm was measured on a Thermomax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

ROS Formation

The intracellular formation of ROS was detected using the fluorescence probe 5-(and 6)chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA; Molecular Probes), as described previously.49 In brief, hydrogen peroxide and peroxidases oxidize the intracellular DCFH to the fluorescence compound 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein. Cells were incubated with TxnIP or scrambled siRNA, as described already. After 48 h of exposure to 25 mM glucose or normal culture medium, cells were washed, trypsinized, resuspended in PBS, loaded with 10 μM CM-H2DCFDA, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The measurement of intracellular ROS was performed on 10,000 cells through a flow cytometer (BD Immunocytometry Systems, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Flow cytometry data were analyzed using WinMDI 2.9 (Scripps Institute, La Jolla, CA).

3H Proline Incorporation

For determination of 3H-proline incorporation, mesangial and NRK cells were transfected with 100 pM TxnIP siRNA or scrambled RNAi for 24 h. After this, DMEM was supplemented with 0.5% BSA and 150 μM l-ascorbic acid alone or with the addition of 19.4 mM glucose. Cells were incubated in the presence of [3H]-proline (1 μCi/well) for an additional 48 h. Cells were harvested, washed four times with PBS then twice with 10% TCA before being solubilized in 1 M NaOH, and then neutralized with 1 M HCl. Incorporation of exogenous [3H]-proline (L-[2,3,4,5-3H]-proline; Amersham Biosciences) was then measured using a liquid scintillation counter (Wallac 1410; Amersham).

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM unless otherwise stated. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA for more than two groups, t test for comparison of two groups, and Mann Whitney U test for nonparametric data. Albuminuria was skew distributed and was analyzed after log transformation and presented as geometric means ×/÷ tolerance factors. All statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism 3.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Pacheco, J. Court, L. DiRago, S. Glowacka, and S. Advani for excellent technical assistance. K.A.C. was supported by a TACTICS scholarship (Canada), a National Health and Medical Research Council Neil Hamilton Fairley scholarship (440712), and a RACP Pfizer overseas grant.

This work was presented in abstract form at the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology, October 31–November 5, 2007.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

A.A. and R.E.G. contributed equally to this work.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at http://www.jasn.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vaughan M: Oxidative modification of macromolecules. J Biol Chem 272: 18513, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forbes JM, Coughlan MT, Cooper ME: Oxidative stress as a major culprit in kidney disease in diabetes. Diabetes 57: 1446–1454, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brownlee M: The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes, 54: 1615–1625, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berlett BS, Stadtman ER: Protein oxidation in aging, disease, and oxidative stress. J Biol Chem 272: 20313–20316, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamawaki H, Berk BC: Thioredoxin: A multifunctional antioxidant enzyme in kidney, heart and vessels. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 14: 149–153, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World CJ, Yamawaki H, Berk BC: Thioredoxin in the cardiovascular system. J Mol Med 84: 997–1003, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen KS, DeLuca HF: Isolation and characterization of a novel cDNA from HL-60 cells treated with 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-3. Biochim Biophys Acta 1219: 26–32, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirota T, Okano T, Kokame K, Shirotani-Ikejima H, Miyata T, Fukada Y: Glucose down-regulates Per1 and Per2 mRNA levels and induces circadian gene expression in cultured Rat-1 fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 277: 44244–44251, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi T, Uehara S, Ikeda T, Itadani H, Kotani H: Vitamin D3 up-regulated protein-1 regulates collagen expression in mesangial cells. Kidney Int 64: 1632–1642, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng DW, Jiang Y, Shalev A, Kowluru R, Crook ED, Singh LP: An analysis of high glucose and glucosamine-induced gene expression and oxidative stress in renal mesangial cells. Arch Physiol Biochem 112: 189–218, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qi W, Chen X, Gilbert RE, Zhang Y, Waltham M, Schache M, Kelly DJ, Pollock CA: High glucose-induced thioredoxin-interacting protein in renal proximal tubule cells is independent of transforming growth factor-beta1. Am J Pathol 171: 744–754, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulze PC, Yoshioka J, Takahashi T, He Z, King GL, Lee RT: Hyperglycemia promotes oxidative stress through inhibition of thioredoxin function by thioredoxin-interacting protein. J Biol Chem 279: 30369–30374, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minn AH, Hafele C, Shalev A: Thioredoxin-interacting protein is stimulated by glucose through a carbohydrate response element and induces beta-cell apoptosis. Endocrinology 146: 2397–2405, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen J, Saxena G, Mungrue IN, Lusis AJ, Shalev A: Thioredoxin-interacting protein: A critical link between glucose toxicity and beta-cell apoptosis. Diabetes 57: 938–944, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamada Y, Miyata S, Nii-Kono T, Kitazawa R, Kitazawa S, Higo S, Fukunaga M, Ueyama S, Nakamura H, Yodoi J, Fukagawa M, Kasuga M: Overexpression of thioredoxin1 in transgenic mice suppresses development of diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1547–1557, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christensen PK, Larsen S, Horn T, Olsen S, Parving HH: Renal function and structure in albuminuric type 2 diabetic patients without retinopathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 16: 2337–2347, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baynes JW, Thorpe SR: Role of oxidative stress in diabetic complications: A new perspective on an old paradigm. Diabetes 48: 1–9, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turoczi T, Chang VW, Engelman RM, Maulik N, Ho YS, Das DK: Thioredoxin redox signaling in the ischemic heart: an insight with transgenic mice overexpressing Trx1. J Mol Cell Cardiol 35: 695–704, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanito M, Masutani H, Nakamura H, Ohira A, Yodoi J: Cytoprotective effect of thioredoxin against retinal photic injury in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43: 1162–1167, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang W, Edwards A: Oxygen transport across vasa recta in the renal medulla. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H1042–H1055, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ries M, Basseau F, Tyndal B, Jones R, Deminiere C, Catargi B, Combe C, Moonen CW, Grenier N: Renal diffusion and BOLD MRI in experimental diabetic nephropathy: Blood oxygen level-dependent. J Magn Reson Imaging 17: 104–113, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilbert RE, Wilkinson-Berka JL, Johnson DW, Cox A, Soulis T, Wu LL, Kelly DJ, Jerums G, Pollock CA, Cooper ME: Renal expression of transforming growth factor-beta inducible gene-h3 (beta ig-h3) in normal and diabetic rats. Kidney Int 54: 1052–1062, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Jan S, Le Meur N, Cazes A, Philippe J, Le Cunff M, Leger J, Corvol P, Germain S: Characterization of the expression of the hypoxia-induced genes neuritin, TXNIP and IGFBP3 in cancer. FEBS Lett 580: 3395–3400, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamada Y, Fukagawa M: A possible role of thioredoxin interacting protein in the pathogenesis of streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy. Kobe J Med Sci 53: 53–61, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parikh H, Carlsson E, Chutkow WA, Johansson LE, Storgaard H, Poulsen P, Saxena R, Ladd C, Schulze PC, Mazzini MJ, Jensen CB, Krook A, Bjornholm M, Tornqvist H, Zierath JR, Ridderstrale M, Altshuler D, Lee RT, Vaag A, Groop LC, Mootha VK: TXNIP regulates peripheral glucose metabolism in humans. PLoS Med 4: e158, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berndt C, Lillig CH, Holmgren A: Thiol-based mechanisms of the thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems: Implications for diseases in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1227–H1236, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Junn E, Han SH, Im JY, Yang Y, Cho EW, Um HD, Kim DK, Lee KW, Han PL, Rhee SG, Choi I: Vitamin D3 up-regulated protein 1 mediates oxidative stress via suppressing the thioredoxin function. J Immunol 164: 6287–6295, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishiyama A, Matsui M, Iwata S, Hirota K, Masutani H, Nakamura H, Takagi Y, Sono H, Gon Y, Yodoi J: Identification of thioredoxin-binding protein-2/vitamin D(3) up-regulated protein 1 as a negative regulator of thioredoxin function and expression. J Biol Chem 274: 21645–21650, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mauer SM: Structural-functional correlations of diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 45: 612–622, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mogensen CE, Schmitz O: The diabetic kidney: from hyperfiltration and microalbuminuria to end-stage renal failure. Med Clin North Am 72: 1465–1492, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Specht K, Richter T, Muller U, Walch A, Werner M, Hofler H: Quantitative gene expression analysis in microdissected archival formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tumor tissue. Am J Pathol 158: 419–429, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiang G, Seki T, Schuster MD, Witkowski P, Boyle AJ, See F, Martens TP, Kocher A, Sondermeijer H, Krum H, Itescu S: Catalytic degradation of vitamin D up-regulated protein 1 mRNA enhances cardiomyocytesurvival and prevents left ventricular remodeling after myocardial ischemia. J Biol Chem 280: 39394–39402, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bunag RD: Validation in awake rats of a tail-cuff method for measuring systolic pressure. J Appl Physiol 34: 279–282, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jerums G, Allen TJ, Cooper ME: Triphasic changes in selectivity with increasing proteinuria in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 6: 772–779, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelly DJ, Zhang Y, Moe G, Naik G, Gilbert RE: Aliskiren, a novel renin inhibitor, is renoprotective in a model of advanced diabetic nephropathy in rats. Diabetologia 50: 2398–2404, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilbert RE, Cox A, Wu LL, Allen TJ, Hulthen UL, Jerums G, Cooper ME: Expression of transforming growth factor-beta1 and type IV collagen in the renal tubulointerstitium in experimental diabetes: effects of ACE inhibition. Diabetes 47: 414–422, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sibony M, Commo F, Callard P, Gasc JM: Enhancement of mRNA in situ hybridization signal by microwave heating. Lab Invest 73: 586–591, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rumble JR, Cooper ME, Soulis T, Cox A, Wu L, Youssef S, Jasik M, Jerums G, Gilbert RE: Vascular hypertrophy in experimental diabetes: Role of advanced glycation end products. J Clin Invest 99: 1016–1027, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Advani A, Kelly DJ, Advani SL, Cox AJ, Thai K, Zhang Y, White KE, Gow RM, Marshall SM, Steer BM, Marsden PA, Rakoczy PE, Gilbert RE: Role of VEGF in maintaining renal structure and function under normotensive and hypertensive conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 14448–14453, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilbert RE, Wu LL, Kelly DJ, Cox A, Wilkinson-Berka JL, Johnston CI, Cooper ME: Pathological expression of renin and angiotensin II in the renal tubule after subtotal nephrectomy: Implications for the pathogenesis of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Am J Pathol 155: 429–440, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baskin DG, Stahl WL: Fundamentals of quantitative autoradiography by computer densitometry for in situ hybridization, with emphasis on 33P. J Histochem Cytochem 41: 1767–1776, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vekaria RM, Shirley DG, Sevigny J, Unwin RJ: Immunolocalization of ectonucleotidases along the rat nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F550–F560, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tajika Y, Matsuzaki T, Suzuki T, Aoki T, Hagiwara H, Tanaka S, Kominami E, Takata K: Immunohistochemical characterization of the intracellular pool of water channel aquaporin-2 in the rat kidney. Anat Sci Int 77: 189–195, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loffing J, Vallon V, Loffing-Cueni D, Aregger F, Richter K, Pietri L, Bloch-Faure M, Hoenderop JG, Shull GE, Meneton P, Kaissling B: Altered renal distal tubule structure and renal Na(+) and Ca(2+) handling in a mouse model for Gitelman's syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 2276–2288, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ellison DH: The thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter and human disease: Reemergence of an old player. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 538–540, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelly DJ, Chanty A, Gow RM, Zhang Y, Gilbert RE: Protein kinase Cbeta inhibition attenuates osteopontin expression, macrophage recruitment, and tubulointerstitial injury in advanced experimental diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1654–1660, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ingram AJ, Ly H, Thai K, Kang MJ, Scholey JW: Mesangial cell signaling cascades in response to mechanical strain and glucose. Kidney Int 56: 1721–1728, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holmgren A, Bjornstedt M: Thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Methods Enzymol 252: 199–208, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Djordjevic T, BelAiba RS, Bonello S, Pfeilschifter J, Hess J, Gorlach A: Human urotensin II is a novel activator of NADPH oxidase in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 519–525, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.