Abstract

High levels of proteinuria predict renal deterioration, suggesting that interventions to reduce proteinuria may postpone the development of severe renal impairment. This multicenter Canadian trial evaluated whether supramaximal dosages of candesartan would reduce proteinuria to a greater extent than the maximum approved antihypertensive dosage. The authors randomly assigned 269 patients who had persistent proteinuria (≥1 g/d) despite 7 wk of treatment with the highest approved dosage of candesartan (16 mg/d) to 16, 64, or 128 mg/d candesartan for 30 wk. The median serum creatinine level was 130.0 μmol/L (1.47 mg/dl), and the median urinary protein excretion was 2.66 g/d; most (53.9%) patients had diabetic nephropathy. The mean difference of the percentage change in proteinuria for patients receiving 128 mg/d candesartan compared with those receiving 16 mg/d candesartan was −33.05% (95% confidence interval −45.70 to −17.44; P < 0.0001). Reductions in BP were not different across the three treatment groups. Elevated serum potassium levels (K+ > 5.5 mEq/L) led to the early withdrawal of 11 patients, but there were no dosage-related increases in adverse events. In conclusion, proteinuria that persists despite treatment with the maximum recommended dosage of candesartan can be reduced by increasing the dosage of candesartan further, but serum potassium levels should be monitored during treatment.

Proteinuria has been a marker of kidney disease; however, recent research has shown that both renal and cardiovascular outcomes seem to correlate with the pretreatment levels of proteinuria and with the reduction of proteinuria with treatment.1–4 Reduction of BP lowers proteinuria, but the use of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or an angiotensin type 1 receptor blocker (ARB) reduces both proteinuria and the rate of deterioration of renal function beyond those seen with equivalent BP reduction from conventional antihypertensive agents1,4; however, a secondary analysis from the Reduction of Endpoints in NIDDM with Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan (RENAAL) study showed that reduction in BP and proteinuria may occur discordantly and that residual albuminuria, despite optimal reduction of BP, is a risk factor for developing ESRD.5

Angiotensin II mediates hemodynamic effects as well as inflammation and fibrosis in the kidney, heart, and vasculature.6 Benefit beyond the hemodynamic effects of an ACEI or an ARB has been seen in the treatment of heart failure.7 Maximal antifibrotic benefit in the kidney seems to require dosages much higher than antihypertensive dosages,8,9 perhaps because there are many more angiotensin type 1 receptors in the kidney and blocking all of them takes a dosage greater than that needed for BP reduction. In the past few years, clinical nephrologists have attempted to lower proteinuria with high dosages or combinations of ACEIs and ARBs. Weinberg et al.10,11 showed better percentage reductions of proteinuria with increasing dosages of candesartan; maximum percentage reductions reached 75 to 80% in these case series with treatment in excess of 128 mg/d candesartan. A small study (32 patients) by Schmeider et al.12 reported a difference in proteinuria reduction between candesartan 32 and 64 mg when compared with proteinuria levels on previous therapy.

Previous studies evaluating high-dosage ARBs in patients with diabetes and microalbuminuria have had inconsistent results.13,14 High dosages of irbesartan have resulted in a small additional reduction in proteinuria, whereas high dosages of valsartan did not show any statistically significant additional reduction of proteinuria in patients with diabetes and proteinuria <1 g/d.

For better understanding of the potential benefits and risks of using dosages of candesartan greater than those recommended for hypertension or heart failure treatment, the Supra Maximal Atacand Renal Trial (SMART) was designed to assess the effects of supramaximal dosages of candesartan compared with the highest approved antihypertensive dosage of candesartan in Canada (16 mg/d at the time the study was initiated) in patients with primary glomerular diseases, diabetes, or hypertensive glomerulosclerosis and persistent proteinuria ≥1 g/d (despite treatment with candesartan 16 mg/d).

RESULTS

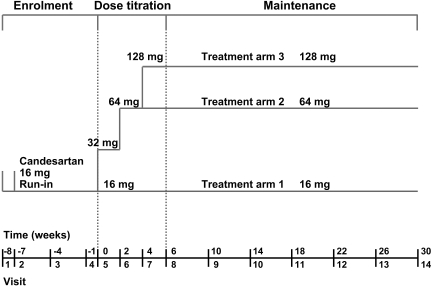

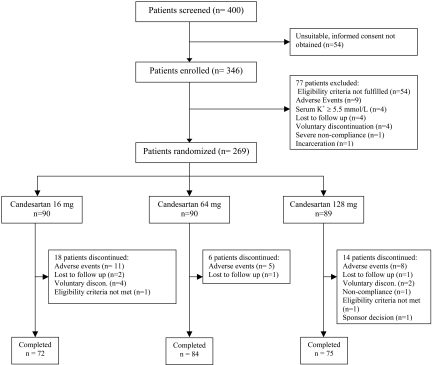

A total of 400 patients were screened; 346 were enrolled in the study (Figure 1) and placed on candesartan 16 mg for 7 wk (Figure 2). The 269 patients who continued to have persistent proteinuria ≥1 g/d and meet other study eligibility criteria after the run-in period were randomly assigned. The baseline characteristics of the randomly assigned patients were similar in the three groups (Table 1). The study was completed by 72, 84, and 75 patients in the candesartan 16, 64, and 128 mg/d groups, respectively.

Figure 1.

Study design for the trial.

Figure 2.

Patient flow chart and outcomes.

Table 1.

Patient demographics at randomization visita

| Demographic | 16 mg/d (n = 90) | 64 mg/d (n = 90) | 128 mg/d (n = 89) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr; mean ± SD) | 56.5 ± 12.2 | 54.8 ± 12.4 | 54.6 ± 12.6 |

| Male gender (%) | 80.0 | 77.8 | 80.9 |

| Weight (kg; mean ± SD) | 92.5 ± 20.5 | 89.7 ± 19.3 | 93.5 ± 19.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2; mean ± SD) | 31.6 ± 6.2 | 31.6 ± 6.4 | 32.2 ± 6.3 |

| SBP (mmHg; mean ± SD) | 133.3 ± 13.9 | 132.5 ± 16.0 | 131.7 ± 14.2 |

| DBP (mmHg; mean ± SD) | 76.9 ± 10.2 | 78.5 ± 9.5 | 76.9 ± 9.0 |

| Pulse (bpm; mean ± SD) | 73.6 ± 9.9 | 70.2 ± 10.4 | 70.8 ± 10.4 |

| Race (%) | |||

| white | 83.3 | 91.1 | 75.3 |

| black | 3.3 | 2.2 | 5.6 |

| Asian | 10.0 | 5.6 | 12.4 |

| other | 3.3 | 1.1 | 6.7 |

| Renal disease diagnosis (%) | |||

| primary glomerular disease | 30.0 | 37.8 | 32.6 |

| hypertensive nephrosclerosis | 14.4 | 10.0 | 13.5 |

| diabetic nephropathy | 55.6 | 52.2 | 53.9 |

| Previous use of ACEI or ARB (%) | |||

| ACEI | 49.4 | 42.2 | 41.0 |

| ACEI and ARB | 25.8 | 18.1 | 19.3 |

| ARB | 22.5 | 39.8 | 37.3 |

| Time from onset of disease (%) | |||

| 0 to 5 yr | 66.7 | 67.8 | 59.8 |

| >5 yr | 33.3 | 32.2 | 40.4 |

| Degree of proteinuria (%) | |||

| 1 to 3 g/d | 57.8 | 57.8 | 56.2 |

| >3 g/d | 42.2 | 42.2 | 43.8 |

BMI, body mass index.

Primary End Point

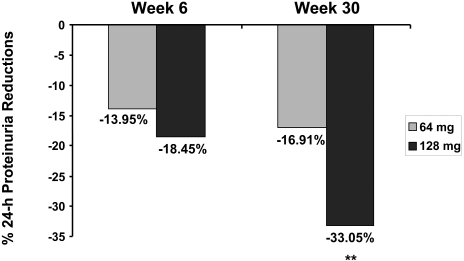

The geometric mean of the 24-h urine protein excretion was 2.85 g/d at randomization and 1.79 g/d at completion for the candesartan 128-mg group; this represents a mean percentage change, compared with the 16-mg group, of −33.05% (95% confidence interval [CI] −45.70 to −17.44; P < 0.0001; Figure 3). When the change in systolic BP (SBP) from randomization to completion was used as a covariate in this analysis (in addition to center and baseline levels of proteinuria), the mean percentage change for the candesartan 128-mg group compared with the 16-mg group was −30.06 (95% CI −43.30 to −13.72]; P = 0.0002). Furthermore, the mean change in the per-protocol population treated with 128 compared with 16 mg was −44.34% (95% CI −58.01 to −26.25]; P < 0.0001). The geometric mean of the 24-h urine protein excretion was 2.83 g/d at randomization and 2.20 g/d at completion for the candesartan 64-mg group; the mean percentage change as compared with the 16-mg group was −16.91% (95% CI −32.7 to −2.7]; P = 0.0492, NS adjusted for two comparisons). The mean percentage change in proteinuria was −7.49% in the candesartan 16-mg group from randomization to completion (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Percentage reduction in 24-h proteinuria at weeks 6 and 30 by candesartan dosage. Number of patients for 64-mg treatment arm were 88 and for the 128-mg treatment arm were 82 and 83 for weeks 6 and 30, respectively. **P < 0.0001

Table 2.

Proteinuria results in g/d and percentage change at various dosages of candesartana

| Urinary Protein Valuesb | 16 mg | 64 mg | 128 mg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomization (SEM) | 2.80 ± 0.07 | 2.83 ± 0.06 | 2.85 ± 0.07 |

| Completion | 2.59 ± 0.08 | 2.20 ± 0.08 | 1.79 ± 0.11 |

| Δ Randomization (%) | −7.49 ± 5.69 | −22.23 ± 6.17 | −36.95 ± 7.05 |

| Δ versus 16 mg | NA | −16.91 | −33.05 |

Analysis of covariance model with center and proteinuria at baseline as covariates.

Geometric means were used to calculate the urinary protein values, because these values are presented as a percentage change.

Proteinuria, as measured on spot urine samples, was significantly reduced for the candesartan 128-mg dosage at week 30 for the urine albumin:creatinine ratio (−29.77%; 95% CI −44.43 to −11.24; P = 0.003) and urine protein:creatinine ratio (−33.4%; 95% CI −45.58 to −18.50; P = 0.0001) but not for the candesartan 64-mg dosage when compared with the effect in the active control group (candesartan 16 mg).

The degree of proteinuria at randomization seemed to influence the response to treatment. Candesartan 128 mg reduced proteinuria by −43.62% (95% CI −58.78 to −22.90; P = 0.0001) in patients with proteinuria between 1 and 3 g/d and by −25.29% (95% CI −45.46 to 2.32; P = 0.037) in those with >3 g/d when compared with the effect in the active control group (candesartan 16 mg). In neither stratum was proteinuria reduced significantly in the candesartan 64-mg treatment group (−16 and −15% in the 1 to 3 and >3 g/d strata, respectively). A post hoc analysis demonstrated that the reduction of proteinuria was similar in both patients with and without diabetes.

Secondary End Points

Serum creatinine levels increased by 7.85, 8.82, and 6.74% in the 16-, 64-, and 128-mg dosage groups, respectively, from randomization to the end of active dosage treatment (Table 3). The changes seen for the candesartan 64- or 128-mg dosage were not significantly different compared with the candesartan 16-mg dosage. Similarly, there were no significant changes in estimated GFR (eGFR) in the three treatment groups (Table 3). There was no significant change in urine sodium content in any group.

Table 3.

Secondary objectives: Change in renal functiona

| Parameter | 16 mg/d | 64 mg/d | 128 mg/d |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum creatinine level (μmol/L; geometric mean ± SEM) | |||

| randomization | 127.00 ± 0.05 | 119.00 ± 0.04 | 135.00 ± 0.05 |

| completion | 137.00 ± 0.05 | 129.00 ± 0.04 | 144.00 ± 0.05 |

| % change | 7.85 ± 1.69 | 8.82 ± 1.69 | 6.74 ± 1.84 |

| treatment comparison with 16 mg | 0.83 (−4.34 to 6.27) | −0.62 (−5.67 to 4.69) | |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2; geometric mean ± SEM) | |||

| randomization | 52.00 ± 0.06 | 55.00 ± 0.05 | 49.00 ± 0.05 |

| completion | 47.00 ± 0.06 | 50.00 ± 0.05 | 45.00 ± 0.05 |

| % change | −8.50 ± 2.00 | −9.50 ± 2.00 | −7.50 ± 2.10 |

| treatment comparison with 16 mg | 1.09 (−6.92 to 5.10) | −0.86 (−5.04 to 7.12) | |

| Serum potassium levels (mmol/L; mean ± SD) | |||

| randomization | 4.47 ± 0.54 | 4.54 ± 0.57 | 4.45 ± 0.46 |

| completion | 4.43 ± 0.47 | 4.57 ± 0.64 | 4.56 ± 0.57 |

| change | 0.00 ± 0.36 | 0.05 ± 0.54 | 0.13 ± 0.44 |

| Urine sodium content (mmol/d; mean ± SD) | |||

| randomization | 226.50 ± 83.70 | 229.90 ± 93.40 | 233.40 ± 61.80 |

| completion | 224.00 ± 80.70 | 221.60 ± 81.60 | 200.50 ± 58.00 |

| change | 6.70 ± 77.50 | −12.20 ± 71.60 | −18.50 ± 68.10 |

Analysis of covariance model with center and baseline measure as covariates.

There was no significant difference among the three treatment groups for serum potassium concentration (4.43 ± 0.47, 4.57 ± 0.64, and 4.56 ± 0.57 mmol/L for the 16-, 64-, and 128-mg candesartan groups, respectively) at the end of active treatment; neither was there a difference in the change in serum potassium levels. The mean percentage reduction in plasma aldosterone level in the candesartan 128-mg treatment group was significantly different compared with the response in the candesartan 16-mg group from randomization to completion (−18.96%; 95% CI −30.52 to −5.47; P = 0.0077). Only in the candesartan 128-mg group was there a significant correlation between the change in plasma aldosterone level and the change in 24-h urine protein content (r = 0.37, P = 0.0087).

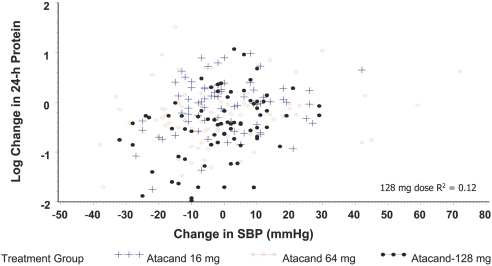

Neither systolic nor diastolic BP (DBP) was statistically different across the three groups at randomization; at completion, there was a NS difference across the three treatment groups when baseline value and center were included as covariates (Table 4). BP decreases in the candesartan 64- and 128-mg groups were NS (Table 4); there was no correlation between the changes in BP and the changes in 24-h urine protein excretion (Figure 4). The correlation coefficient was 0.35 for the candesartan 128-mg group (P = 0.188 versus 16 mg). There was no significant difference in pulse rate at randomization or completion across the three groups.

Table 4.

BP and pulse rate at enrolment, randomization, and completion in the three treatment groupsa

| Parameter | 16 mg/d | 64 mg/d | 128 mg/d |

|---|---|---|---|

| SBP (mmHg) | |||

| enrollment | 142.0 ± 19.5 | 136.2 ± 15.7 | 141.2 ± 18.3 |

| randomization | 134.1 ± 15.1 | 134.9 ± 15.1 | 134.8 ± 14.5 |

| completion | 133.4 ± 15.3 | 131.5 ± 20.0 | 130.3 ± 17.0 |

| Δrandomizationb | −0.6 ± 11.6 | −3.3 ± 18.6 | −4.0 ± 12.4 |

| DBP (mmHg) | |||

| enrollment | 79.9 ± 10.1 | 77.8 ± 8.3 | 82.9 ± 10.3 |

| randomization | 75.7 ± 8.0 | 77.7 ± 9.1 | 79.7 ± 8.3 |

| completion | 75.4 ± 9.5 | 76.5 ± 10.1 | 75.7 ± 9.7 |

| Δrandomizationb | −0.6 ± 8.6 | −0.8 ± 9.3 | −3.8 ± 7.8 |

| Pulse (bpm) | |||

| enrollment | 71.7 ± 10.0 | 69.4 ± 10.4 | 69.6 ± 11.0 |

| randomization | 72.7 ± 9.9 | 70.5 ± 11.7 | 72.2 ± 11.8 |

| completion | 71.9 ± 10.3 | 69.3 ± 11.9 | 69.8 ± 10.5 |

| Δrandomizationb | −1.1 ± 10.2 | −1.0 ± 10.5 | −1.7 ± 10.6 |

Data are means ± SD.

All measures are P > 0.05 when high dosages are compared with 16 mg/d. Model includes baseline measure and center as covariates.

Figure 4.

Correlation between changes in SBP and changes in proteinuria.

Safety

No patients died during the study. During the randomized phase of the study, there were 32 serious adverse events reported by 24 patients. Twenty-four patients discontinued participation as a result of adverse events (Table 5). Eleven patients were discontinued as a result of elevations in serum potassium levels >5.5 mmol/L; this occurred in four, four, and three patients, respectively, in the three treatment groups. One patient in the 16-mg group and two patients in the 128-mg group (neither had been titrated to 128 mg) were discontinued as a result of an elevated serum creatinine level. Two other patients in the candesartan 16-mg group were discontinued as a result of renal problems: One patient developed acute renal failure after an episode of status asthmaticus, and one patient developed crescentic glomerulonephritis superimposed on his original IgA nephropathy. One patient was discontinued as a result of hypotension, and one was discontinued as a result of hypertension. The most frequent adverse events were peripheral edema, nasopharyngitis, fatigue, and headache. Peripheral edema seemed to occur less often as the dosage of candesartan increased (22.2, 18.9, and 12.4%, respectively).

Table 5.

Discontinuations as a result of adverse events occurring after randomization

| Adverse Event | 16 mg/d | 64 mg/d | 128 mg/d |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elevated serum potassium (>5.5 mmol/L) | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Elevated serum creatinine | 1 | 2 | |

| Renal problems | |||

| acute renal failure | 1 | ||

| crescentic glomerulonephritis | 1 | ||

| Angina | 1 | ||

| Myalgia | 1 | ||

| Erosive esophagitis | 1 | ||

| Bladder infection, fever | 1 | ||

| Hypotension | 1 | ||

| Irregular heart rate, edema, worsening of hypertension | 2 | ||

| Dyspnea, pain, headache, rhinorrhea | 1 | ||

| Total | 11 | 5 | 8 |

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that using the ARB candesartan at the dosage of 128 mg/d, a dosage much higher than the maximum dosage recommended for the treatment of hypertension or heart failure, results in a further significant reduction in urinary protein excretion. When the study was planned and initiated, 16 mg of candesartan was the maximum approved dosage for the treatment of hypertension in Canada; hence, candesartan 16 mg was the active control in this study. Because this study tested two treatments (64 and 128 mg) versus 16 mg active control, the level of significance had to be reduced to P < 0.025, otherwise the candesartan 64-mg treatment would have been significantly better than candesartan 16 mg. The additional antiproteinuric effect of high-dosage candesartan is independent of BP reduction. The antiproteinuric effect of candesartan 128 mg was consistently observed in the 1- to 3- and >3-g/d groups and in the patient groups with and without diabetes.

Proteinuria has generally been used as a marker for the severity of renal disease. Recently, proteinuria was demonstrated to be a risk marker for cardiovascular disease. A secondary analysis of the RENAAL study that used losartan up to the maximum recommended antihypertensive dosage for the treatment of patients with diabetic nephropathy showed that cardiovascular outcomes, as well as renal outcomes, were related to both the degree of proteinuria at initiation of treatment and the percentage reduction of proteinuria after 6 mo of treatment.3–5 These subanalyses demonstrated that the response to losartan could be discordant and that those who responded with a reduction of albuminuria had better outcomes, independent of BP reductions. This finding leads to the hypothesis that purposefully aiming for lower levels of proteinuria with blockade of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system may lead to improved cardiovascular outcomes. The Renoprotection of Optimal Antiproteinuric Doses (ROAD) study15 demonstrated that higher, compared with lower, dosages of ACEI or ARB in patients with nephropathy and without diabetes led to a reduction of proteinuria and to a reduction of renal end points as well. It is not yet known whether the ability to reduce proteinuria further with a supramaximal dosage of candesartan could result in further reduction in cardiovascular as well as renal outcomes for patients with diabetic or nondiabetic nephropathy.

In 2005, a small study evaluated the effect of candesartan 32 and 64 mg in 32 patients (24 had glomerulonephritis, and five had diabetes) with proteinuria and an average protein excretion of 2.35 g/d at enrollment; the primary outcome was the change in proteinuria from enrollment (at which time patients could be on any ACEI or ARB for a minimum of 3 mo) to the evaluation performed after the patients had been on the randomized dosage for 8 wk. That study demonstrated no additional effect of candesartan 32 mg over the patients’ previous ACEI and ARB treatment, whereas candesartan 64 mg lowered proteinuria 42% from the level at enrollment; however, that study was small with a high risk for a type 1 error and no predetermined sample size estimate.12 Also, the 8-wk duration may not have been long enough to assess the total effect of the interventions. In the SMART, the use of an active control arm of candesartan 16 mg demonstrated that during the subsequent 30 wk after randomization, there was an additional reduction in proteinuria for which the analysis of the other treatments needed to control; therefore, in the study by Schmeider et al.,12 the effect of candesartan 32 mg may have actually been greater given a longer study duration and hence the effect of candesartan 64 mg would have been different.

Previous controlled trials with high dosages of ARBs have given inconclusive results. One trial using a crossover design included 52 patients with type 2 diabetes and <1 g/d albuminuria (measured after patients had been free of antihypertensive medication for 8 wk). The patients were treated with irbesartan at dosages of 300, 600, and 900 mg/d for 10-wk treatment periods each in a crossover design.13 The reductions in BP were similar across the three dosages, and urinary albumin excretion fell 52, 49, and 59%, respectively, from the drug-free baseline (P < 0.01); therefore, increasing the daily irbesartan dosage to three times the recommended dosage reduced urinary albumin excretion an additional absolute amount of 7%, whereas in our study, candesartan 128 mg resulted in an additional 33% absolute reduction in proteinuria. In another recent trial using high-dose ARB therapy, the Diovan Reduction Of Proteinutria (DROP) study reported the randomization of 391 patients with diabetic nephropathy and an albuminuria rate of 20 to 700 μg/min (maximum of approximately 900 mg/d) to valsartan 160, 320, or 640 mg/d.14 The DBP was significantly lower in the group treated with the valsartan 640-mg dosage. Although each of the three dosage levels of valsartan reduced proteinuria significantly compared with the drug-free baseline, there was no increased effect of the 320- or 640-mg dosage compared with the 160-mg dosage; therefore, the three largest studies that evaluated the effect of high dosages of ARBs on proteinuria used different incremental dosages of different ARBs in populations of patients with different glomerular diseases with different ranges of proteinuria. This study used a mix of patients, although the majority had type 2 diabetes and the other trials had only patients with type 2 diabetes. In this study, only patients who continued to have ≥1 g/d proteinuria while on standardized ARB treatment were included, whereas the patients in the other trials had a lesser degree of proteinuria and started from a baseline therapy that lacked any inhibitor of the renin-angiotensin system. BP control in this trial was very good compared with that in the DROP study, perhaps because we did not stop antihypertensive treatment in our patients before randomization.

High-dosage therapy with candesartan was well tolerated, with only 11 (4.1%) patients requiring discontinuation from the study as a result of high serum potassium levels (defined as serum K+ > 5.5 mmol/L in this study). This may have been due to the exclusion of patients with a serum K+ level ≥ 5.5 mmol/L at baseline or on more than one occasion in the 6 mo before visit 1. In an observational study of >12,500 patients who had type 2 diabetes and were followed for 3 yr, the prevalence of a serum potassium level > 5.5 mmol/L was 4% in patients with diabetic (proteinuric) nephropathy and an eGFR > 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2; the prevalence of the high serum potassium level rose to 8% in patients with type 2 diabetes and a GFR between 45 and 59 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (only 49% of this cohort had proteinuria).16 Therefore the patients who had diabetes and were recruited for the SMART likely represented the majority of patients with diabetic nephropathy and the discontinuation of 4.1% of patients with a serum K level > 5.5 mmol/L is not excessive compared with the prevalence rates of high serum K levels in that population of patients. With biochemical monitoring and appropriate dietary counseling as needed, this study has demonstrated that a broad range of patients with proteinuria can benefit from high-dosage candesartan treatment in a safe manner.

In summary, in this trial of patients with persistent proteinuria ≥ 1 g/d despite treatment with candesartan 16 mg/d and good BP control, treatment with candesartan at dosages four and eight times the originally recommended daily dosage of 16 mg resulted in an additional 33% reduction in proteinuria (with candesartan 128 mg/d); however, because better reduction in proteinuria may result in better renal and cardiovascular outcomes for high-risk patients with proteinuria, more studies are required to find the optimal dosage for reduction of proteinuria and to explore the effects of that dosage on renal as well as cardiovascular outcome end points.

CONCISE METHODS

Study Design

This prospective, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled, parallel-group study was conducted at 29 nephrology centers and clinics in Canada. It was developed by the steering committee (E.B., N.M., and P.R.d.C.) in collaboration with AstraZeneca Canada and managed and coordinated by the steering committee and AstraZeneca Canada. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the research ethics boards at each of the academic centers and by IRB Services (Aurora, Canada) for those community centers. The main database and data handling was supported by AstraZeneca Canada. The statistical analyses were predetermined by the steering committee and performed by the statistician at AstraZeneca Canada in collaboration with the steering committee. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. E.B. and the steering committee prepared the manuscript.

Selection and Description of Participants

Eligible patients were men or women who were aged 18 to 80 yr and provided written informed consent. The eligible patients had primary glomerular disease that was not currently being treated with any disease-specific treatment, diabetic nephropathy or hypertensive nephrosclerosis, and a urine protein measurement of ≥1 g/d on at least two occasions in the previous 6 mo. Patients could not be taking immunosuppressant drugs, corticosteroids, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Patients were required to have stable hypertension defined as no new antihypertensive medications started within 6 wk of visit 1. Patients taking ACEIs or ARBs must have been doing so for a minimum period of 3 mo before visit 1. SBP must have been <170 and DBP <100 mmHg with the use of antihypertensive medications. Exclusion criteria were the presence of known or suspected secondary hypertension including bilateral renal artery stenosis or unilateral renal artery stenosis to a solitary kidney, pregnancy, a serum creatinine level >300 μmol/L or an eGFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (abridged Modification of Diet in Renal Disease [MDRD] equation), presence of polycystic kidney disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, polyarteritis nodosa, amyloidosis or myeloma, or a serum potassium level ≥5.5 mmol/L at baseline or on more than one occasion in the 6 mo before visit 1.

Enrollment, Randomization, and Treatment

Patients were evaluated at the enrollment visit. When they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, they underwent clinical and laboratory evaluation. No urine assessment was done at this visit. When they met the laboratory enrollment criteria, they were seen 1 wk later at visit 2. At that visit, their previous ARB and/or ACEI treatment was discontinued and all patients received open-label candesartan (Atacand; AstraZeneca, Mississauga, Canada) 16 mg/d for 7 wk. At visit 4, patients completed two 24-h urine collections and had baseline laboratory evaluations performed. One week later, at visit 5, patients who continued to have a urine protein excretion >1 g/d and meet other study eligibility criteria were randomly assigned, using an interactive voice response system, to receive either candesartan 16, 64, or 128 mg/d. The patients’ allocation was blocked with a block size of 3 in a 1:1:1 ratio; patients were stratified according to degree of proteinuria as >3 g/d or between 1 and 3 g/d. Forced titration of candesartan dosage was undertaken during the next 6 wk, with laboratory and clinical evaluation of the patient every 2 wk; randomized treatment continued for an additional 24 wk with clinical and laboratory evaluations every 4 wk. Patients underwent their final clinical and laboratory evaluations at visit 14, after 30 wk total on randomized therapy. A final safety and laboratory evaluation was completed for all patients 2 wk after cessation of randomized treatment (visit 15, week 32). Additional antihypertensive medications, excluding ACEIs, ARBs, or nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, could be added to randomized treatment at the discretion of the treating physician to reduce BP to the target of 125/75 mmHg. Two 24-h urine collections were completed before randomization (visit 4), at the end of dosage titration (visit 8), and at week 30 (visit 14); spot urine samples were collected at all visits between the end of dosage titration and completion for analysis of albumin-to-creatinine and protein-to-creatinine ratios. Compliance was checked at every visit by pill counts with patients continuing only when compliance was between 80 and 120%.

End Points

The primary end point was the percentage change in 24-h urine protein content from randomization (week 0, visit 5, at which time all patients were receiving candesartan 16 mg) to week 30 as compared with the change in 24-h urine protein content in the 16-mg group from randomization to the end of treatment. Secondary outcomes included effects on renal function as measured by serum creatinine levels and eGFR, BP, and the safety of high-dosage candesartan.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis of the primary and secondary variables, 24-h urine protein content and BP change from randomization, and serum creatinine levels was performed using an analysis of covariance with CIs for the difference in score between treatments via a mixed model and an unstructured variance-covariance matrix. The statistical model included center as a random covariate and severity of disease at baseline. The analysis of the 24-h urine protein content and the secondary analysis of the serum creatinine level was therefore performed on visit 14 or last observation carried forward. With the exception of BP, all primary and secondary variables were log-transformed (natural logarithms) for comparison and back-transformed for the results presentation. Residual analysis showed no deviation from statistical normality. Descriptive statistics included geometric means and SEMs in the log scale for individual treatments and for the change from randomization, the geometric mean percentage change and the SEM.

All statistical tests were two-sided, and 97.5% CIs were constructed for the primary and secondary variables and presented as 95% adjusted. Any comparison was declared significant at P < 0.025 as a means to adjust for two treatment comparisons. The candesartan 16-mg treatment group served as an active treatment group for the treatment comparisons. Comparisons were done for the intention-to-treat groups. Because of the inherent variation in urinary protein excretion, two 24-h urine collections for protein were performed, and analysis was performed using the higher of the two values.

The sample size estimation was based on unpublished data from a pilot study using higher than approved dosages of candesartan in a group of patients with persistent proteinuria. It was assumed that the 24-h urine protein excretion followed an approximately normal distribution, that the mean treatment difference (1.27 g) and data dispersion (SD 2.66) between the 16- and the 64-mg group would be of the same magnitude as in the unpublished study. This also provided a moderate mean candesartan effect size of 0.47 for this standard and high ARB dosage. Under these conditions, at least 71 completed patients (89 randomly assigned assuming a 30% dropout rate) would be needed per treatment arm to obtain statistical significance. This comparison also assumes an 80% chance of finding differences (if they clinically exist), a 0.05 probability of a type I error, and a two-sided statistical test. No statistical interim analysis was planned, and none was performed.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of AstraZeneca Canada for support and funding of this study, including S. Escobedo, M. Bukoski, A. Dziarmaga, and A. Ljunggren from AstraZeneca Global. AstraZeneca Canada also assisted the planning committee with statistical expertise in the design and analysis of the study. We also thank the SMART investigators for invaluable assistance in the implementation of this study: E. Burgess, Calgary; N. Muirhead, London; P. Rene de Cotret, Québec; B. Barrett, St. John's; G. Pylypchuk, Saskatoon; D. Garceau, Ste Foy; S. Jolly, Kitchener; A. Steele, Courtice; G. Wu, Mississauga; B. Nathoo, Richmond Hill; A. Chiu, Vancouver; S. Tobe, Toronto; R. Ting, Scarborough; J. Roscoe, Scarborough; R. Tremblay, Laval; M. Parmar, Timmins; V. Pichette, Montreal; T. Keough-Ryan, Halifax; S. Cournoyer, Greenfield Park; A. McMahon, Edmonton; B. Penner, Winnipeg; L. Roy, Montreal; P. Watson, Thunder Bay; R. Goluch, Sudbury; D. Birbrager, Oshawa; D. Kates, Kelowna; M. Berall, Weston; D. Sapir, Oakville; and P. McFarlane, Toronto.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This trial has been registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT00242346).

See related editorial, “Drug Dosing for Renoprotection: Maybe It's Time for a Drug Efficacy-Safety Score?” on pages 688–689.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, deZeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving H-H, Remuzzi G, Snapinn SM, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S, RENAAL Study Investigators: Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 345: 861–869, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Mosconi L, Pisoni R, Remuzzi G: Urinary protein excretion rate is the best independent predictor of ESRF in non-diabetic proteinuric chronic nephropathies. “Gruppo Italiano di Studi Epidemiologici in Nefrologia” (GISEN). Kidney Int 53: 1209–1216, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Zeeuw D, Remuzzi G, Parving H-H, Keane WF, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S, Snapinn S, Cooper ME, Mitch WE, Brenner BM: Albuminuria, a therapeutic target for cardiovascular protection in type 2 diabetic patients with nephropathy. Circulation 110: 921–927, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Zeeuw D, Remuzzi G, Parving H-H, Keane WF, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S, Snapinn S, Cooper ME, Mitch WE, Brenner BM: Proteinuria, a target for renoprotection in patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy: Lessons from RENAAL. Kidney Int 65: 2309–2320, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eijkelkamp WBA, Zhang Z, Remuzzi G, Parving H-H, Cooper ME, Keane WF, Shahinfar S, Gleim GW, Weir MR, Brenner BM, de Zeeuw D: Albuminuria is a target for renoprotective therapy independent from blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy: Post hoc analysis from the Reduction of Endpoints in NIDDM with Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan (RENAAL) trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1540–1546, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dzau VJ, Antman EM, Black HR, Hayes DL, Manson J, Plutzky J, Popma JJ, Stevenson W: The cardiovascular disease continuum validated: Clinical evidence of improved outcomes. Part I: Pathophysiology and clinical trial evidence (risk factors through stable coronary artery disease). Circulation 114: 2850–2870, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Jessup M, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Michl K, Oates JA, Rahko PS, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Yancy CW, Antman EM, Smith SC Jr, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Jacobs AK, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B, American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American College of Chest Physicians, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation; Heart Rhythm Society: ACC/AHA 2005 Guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update 2001 Guidelines for the evaluation and management of heart failure): Developed in collaboration with the American College of Cheat Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 112: e154–e235, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolf G, Ritz E: Combination therapy with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers to halt progression of chronic renal disease: pathophysiology and indications. Kidney Int 67: 799–812, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu C, Gong R, Rifai A, Tolbert EM, Dworkin LD: Long-term, high-dosage candesartan suppresses inflammation and injury in chronic kidney disease: Nonhemodynamic renal protection. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 750–759, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinberg MS, Weinberg AJ, Cord R, Zappe DH: The effect of high-dose angiotensin II receptor blockade beyond maximal recommended doses in reducing urinary protein excretion. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 2[Suppl 1]: S196–S198, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinberg AJ, Zappe DH, Ramadugu R, Weinberg MS: Long-term safety of high-dose angiotensin receptor blocker therapy in hypertensive patients with chronic kidney disease. J Hypertens 24 [Suppl 1]: S95–S99, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmieder RE, Klingbeil AU, Fleischmann EH, Veelken R, Delles C: Additional antiproteinuric effect of ultrahigh dose candesartan: A double-blind, randomised, prospective study. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 3038–3045, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossing K, Schjoedt KJ, Jensen BR, Boomsma F, Parving H-H: Enhanced renoprotective effects of ultrahigh doses of irbesartan in patients with type 2 diabetes and microalbuminuria. Kidney Int 68: 1190–1198, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollenberg NK, Parving H-H, Viberti G, Remuzzi G, Ritter S, Zelenkofske S, Kandra A, Daley WL, Rocha R: Albuminuria response to very high-dose valsartan in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Hypertens 25: 1921–1926, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hou FF, Zhang D, Chen PY, Zhang WR, Liang M, Guo ZJ, Jiang JP: Renoprotection of Optimal Antiproteinuric Doses (ROAD) study: A randomized controlled study of benazepril and losartan in chronic renal insufficiency. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1889–1898, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel UD, Young EW, Ojo AO, Hayward RA: CKD progression and mortality among older patients with diabetes. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 406–414, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]