Abstract

A number of studies have shown that placental insufficiency affects embryonic patterning of the kidney and leads to a decreased number of functioning nephrons in adulthood; however, there is circumstantial evidence that placental insufficiency may also affect renal medullary growth, which could account for cases of unexplained renal medullary dysplasia and for abnormalities in renal function among infants who had experienced intrauterine growth retardation. We observed that mice with late gestational placental insufficiency associated with genetic loss of Cited1 expression in the placenta had renal medullary dysplasia. This was not caused by lower urinary tract obstruction or by defects in branching of the ureteric bud during early nephrogenesis but was associated with decreased tissue oxygenation and increased apoptosis in the expanding renal medulla. Loss of placental Cited1 was required for Cited1 mutants to develop renal dysplasia, and this was not dependent on alterations in embryonic Cited1 expression. Taken together, these findings suggest that renal medullary dysplasia in Cited1 mutant mice is a direct consequence of decreased tissue oxygenation resulting from placental insufficiency.

Placental insufficiency is the most common cause of intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) in the United States and is associated with increased perinatal mortality and a variety of common diseases with onset in adult life.1–3 IUGR results from compensatory changes in the fetal circulation in response to placental insufficiency, with shunting of blood toward the brain, away from other nonessential organs.4 The kidney is particularly sensitive to the effects of placental insufficiency during late gestation, when it undergoes rapid growth.5,6 This is thought to explain the epidemiologic and experimental data linking IUGR with reduced nephron numbers in adults3; however, the renal medulla undergoes rapid expansion during late gestation,5 suggesting that intrauterine growth of this structure may also be susceptible to the effects of placental insufficiency. There is circumstantial evidence to support this hypothesis. For example, guinea pigs with IUGR have reduced renal medullary surface areas,7 whereas human fetuses with IUGR have increased renal medullary echogenicity that could result from decreased tissue oxygenation.8–10 This may be of clinical importance because many patients with congenital renal malformations have unexplained renal medullary dysplasia,11 which could result from IUGR-dependent effects on growth and patterning of the medulla. Furthermore, abnormal growth of the renal medulla could account for abnormalities in urine-concentrating capacity in infants with IUGR.12 Despite this, little attention has been given to the effects of placental insufficiency on embryonic development of the renal medulla.

Cited1 is a non-DNA binding transcriptional co-factor that is expressed in the developing heart, liver, and trophectoderm-derived cells of the placenta13,14 and is restricted to the condensed metanephric mesenchyme in the embryonic kidney.15 Cited1 null mice have abnormalities in mammary gland maturation16 but are born without evidence of IUGR or developmental defects on a mixed or 129/SvJ strain background15; however, Cited1 null mice on a C57Bl/6 background have abnormal organization of the placental labyrinth, promoting late gestational placental insufficiency with IUGR.13 A proportion of female Cited1 heterozygous mutants also show evidence of IUGR. This occurs because Cited1 is expressed in trophectoderm-derived cells of the placenta and is located on the X chromosome,17 and paternally inherited X chromosomes are inactivated in the placenta18; therefore, female Cited1 heterozygotes with a paternally inherited wild type X chromosome are Cited1 null in the placenta and heterozygous in the embryo, whereas female Cited1 heterozygotes with a maternally inherited wild-type X chromosome are Cited1 heterozygous in the placenta and embryo. Comparative analysis of female Cited1 heterozygotes with paternally versus maternally inherited wild type X chromosomes shows that IUGR results from placental insufficiency and not loss of embryonic Cited1 expression.

In this article, we show that IUGR associated with loss of placental Cited1 promotes abnormal patterning of the renal medulla. Comparative analysis of female Cited1 heterozygotes with paternal versus maternally inherited wild type X chromosomes indicates that this effect is independent of changes in embryonic Cited1 expression. These findings provide the first direct evidence that placental insufficiency promotes renal medullary dysplasia.

RESULTS

Cited1C57Bl/6 Null Mice Have Renal Medullary Dysplasia

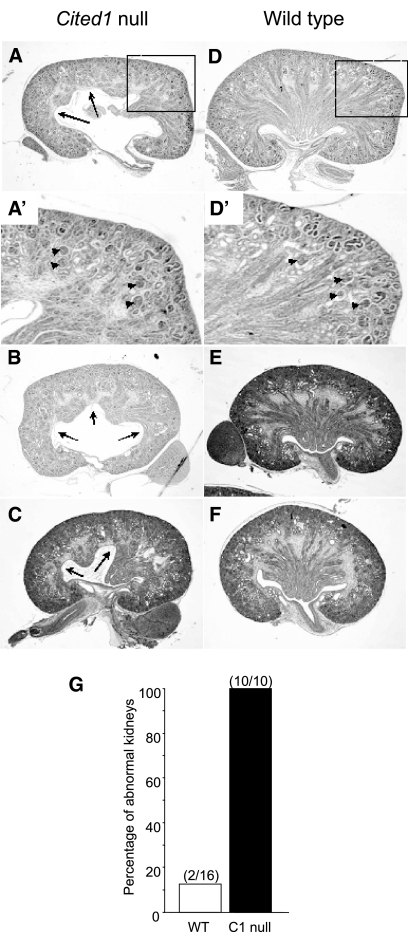

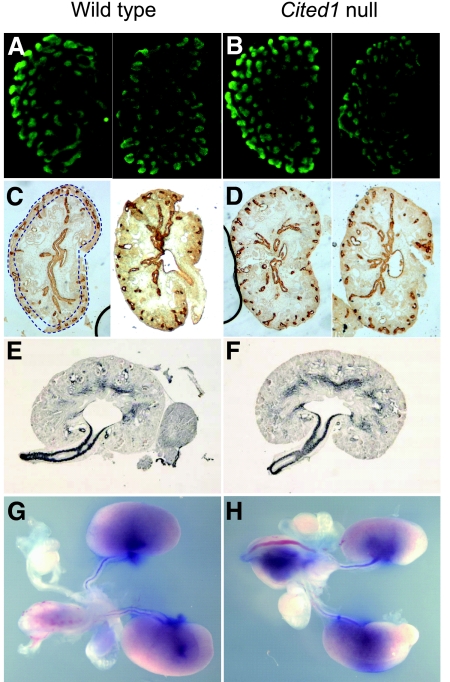

Cited1 null mice on a C57Bl/6 background (Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice) have renal medullary dysplasia that is apparent from embryonic day postcoitus 17.5 (E17.5). Renal dysplasia is bilateral and associated with disorganized growth and patterning of the renal medulla during late gestation when compared with wild type littermate controls (E18.5; Figure 1, A through F). Ten of 10 kidneys from five Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice had variable, disorganized expansion of the renal medulla, whereas only two of 16 kidneys (both from the same mouse) from eight wild-type littermates had mild medullary dysplasia (Figure 1G). Cortical thickness and glomerular numbers, indicators of nephron patterning, were normal for this stage of development (Figure 1, A′ and D′). To evaluate this further, we looked for evidence of abnormal ureteric bud (UB) branching in Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice earlier in development. There was no reduction in UB branching in metanephroi isolated from E12.5 Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice and grown in culture for 3 d (wild type [n = 5], UB tips (mean ± SEM) 63.2 ± 5.6, Cited1C57Bl/6 null [n = 4], UB tips 73.5 ± 9.9; t test, P > 0.05 versus wild-type; Figure 2, A and B). Furthermore, no reduction in UB tips was detected by Calbindin D28K staining in the outer nephrogenic zone of E15.5 kidneys from Cited1C57Bl/6 null embryos (wild type [n = 6], UB tips 22.1 ± 0.82, Cited1C57Bl/6 null [n = 3], 24.7 ± 0.82; t test, P > 0.05 versus wild-type; Figure 2, C and D). These findings indicate that renal medullary dysplasia in Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice does not result from a defect in UB branching. We therefore looked for evidence of ureteric obstruction in Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice, because this could account for renal dysplasia later in gestation. There was no pelvicaliceal dilation or abnormal ureteric muscularization (α-smooth muscle actin expression) in E16.5 kidneys before renal medullary dysplasia is apparent (Figure 2, E and F). Furthermore, analysis of E18.5 kidneys showed no evidence of ureteric obstruction: There was free flow of methylene blue down the ureter after injection into the renal pelvis in four of four wild-type and four of four Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice evaluated (Figure 2, G and H). Taken together, these studies indicate that Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice have renal medullary dysplasia that does not result from defects in UB branching or lower urinary tract obstruction.

Figure 1.

Renal medullary dysplasia in E18.5 Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice. (A through C) Cited1C57Bl/6 null kidneys have renal medullary dysplasia associated with disorganized expansion of the medulla into the renal pelvis (arrows). (D through F) Wild-type kidneys are shown for comparison. Boxes in A and D indicate enlarged insets. (A′ and D′) Insets showing normal cortical thickness and nephronic patterning in Cited1C57Bl/6 null and wild-type kidneys. (G) Frequency of renal medullary dysplasia in E18.5 kidneys from five Cited1C57Bl/6 null and eight wild-type male littermates (kidney numbers). Magnification, ×100.

Figure 2.

UB branching and patency in Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice. (A and B) Whole-mount preparations of cultured metanephroi isolated from two E12.5 wild-type (A) and two Cited1C57Bl/6 null (B) embryos, cultured for 3 d and stained using anti–Calbindin D28K antibodies (a UB marker). (C and D) Calbindin D28K staining of E15.5 kidneys from two wild-type (C) and two Cited1C57Bl/6 null (D) embryos. Dotted blue lines in C illustrate outer nephrogenic zone areas used to count Calbindin D28K–positive UB tips. (E and F) Sections through the renal pelvis of E16.5 kidneys from wild-type (E) and Cited1C57Bl/6 null (F) mice stained for α-smooth muscle actin. (G and H) Representative images illustrating methylene blue dye passage down the ureters of E18.5 wild-type (G) and Cited1C57Bl/6 (H) null mice after injection into the renal pelvis. Images obtained using a dissecting microscope. Magnification, ×100 in A through F; ×10 in G and H.

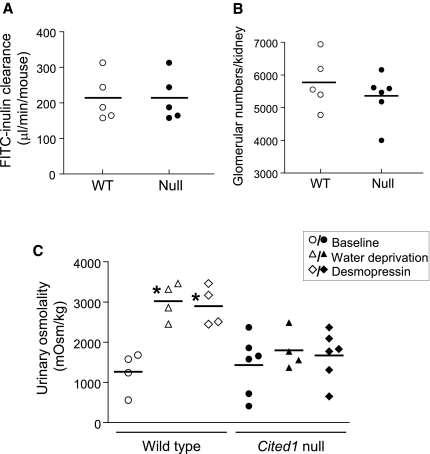

Renal Function in Adult Cited1C57Bl/6 Null Mice

To determine whether this embryonic defect affects renal function, we evaluated renal histology, glomerular number, and GFR in adult male Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice (age 53.6 ± 3.3 wk) and wild-type littermates (age 50.3 ± 3.0 wk). There were no obvious differences in renal structure (M.P.d.C., data not shown) or GFR between wild-type and Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice (Figure 3A). There was a minor reduction in glomerular numbers in Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice, but this difference failed to reach statistical significance (Figure 3B). There was, however, a urine-concentrating defect in Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice: Whereas baseline urinary osmolality was similar to wild-type mice, there was a reduction in urinary osmolality in response to water deprivation or treatment with desmopressin in Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice (Figure 3C). This is consistent with a defect in renal medullary function in Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice.

Figure 3.

Renal function in adult Cited1C57Bl/6 mutant mice. (A through C) GFR (measured by FITC-inulin clearance in μl/min per mouse; A), glomerular counts (direct counting of glomeruli after acid digestion of the kidneys; B), and urine-concentrating capacity (spot urine osmolality in mOsm/kg; C) were determined in adult male wild-type (WT) and Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice. Samples were obtained from controls with free access to water, after 23 h of water deprivation and after intraperitoneal injection with 1 ng/g desmopressin intraperitoneally. Individual data points with mean vales shown. Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA, *P < 0.05 versus WT controls. No significant differences were detected between glomerular counts or GFR between genotypes.

Renal Medullary Dysplasia in Cited1C57Bl/6 Heterozygotes with Placental Insufficiency

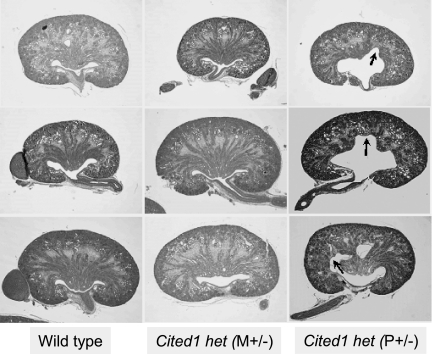

Late gestational renal medullary dysplasia is difficult to explain on the basis of the expression of Cited1 during nephrogenesis, because Cited1 expression is restricted to the outer nephrogenic zone in the developing kidney.15 An alternative explanation is that it results from the placental insufficiency described in Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice.13 Mice characterized in this article include a subset of the total Cited1C57Bl/6 mutant embryos reported by Rodriguez et al.13 Fetal weights in E18.5 Cited1C57Bl/6 null embryos with renal medullary dysplasia were lower than those of their wild-type littermates (wild-type [n = 8; mean ± SEM] 1.1850 ± 0.0350 g, Cited1C57Bl/6 null [n = 5] 1.0010 ± 0.0149 g; t test, P < 0.05 versus wild-type). This indicates that Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice used for our studies have IUGR and suggests that renal medullary dysplasia could result from placental insufficiency. To address this, we compared E18.5 kidneys from female Cited1P+/− heterozygotes with a paternally inherited wild-type X chromosome (they do not express Cited1 in the placenta and have IUGR) with female Cited1M+/− heterozygotes with a maternally inherited wild-type X chromosome (they express Cited1 in the placenta and do not have IUGR13). Fetal weights in Cited1P+/− mutants were lower than those of wild-type mice (Cited1P+/− mutants [n = 4] 0.9160 ± 0.0364 g; t test, P < 0.05 versus wild-type mice above), indicating that these Cited1P+/− mice have IUGR. Unlike Cited1M+/− mice, E18.5 Cited1P+/− kidneys have renal medullary dysplasia (Figure 4). Because Cited1 is detected equally in E18.5 kidneys from female Cited1C57Bl/6 heterozygotes with or without placental insufficiency (Supplemental Figure 1), this suggests that placental insufficiency and not the loss of renal Cited1 causes renal medullary dysplasia in Cited1C57Bl/6 mutant mice.

Figure 4.

Renal patterning defects in female Cited1C57Bl/6 heterozygotes. Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections through the renal pelvis of E18.5 embryonic kidneys from female Cited1C57Bl/6 mutants. Female Cited1C57Bl/6 heterozygotes with P+/− (with placental insufficiency) but not M+/− (without placental insufficiency) wild-type X chromosomes have abnormal organization and expansion of the renal medulla into the pelvis (arrows). Wild-type female littermate kidneys are shown from comparison. Magnification, ×100.

Cited1C57Bl/6 Mutants Have Increased Renal Medullary Apoptosis

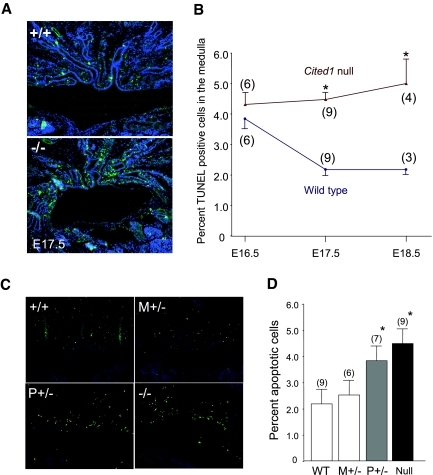

To explore the mechanisms mediating this effect, we evaluated apoptosis in the kidneys of Cited1C57Bl/6 mutant mice. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated digoxigenin-deoxyuridine nick-end labeling (TUNEL)-positive, mainly nontubular interstitial cells were detected in the renal medulla of wild-type mice at E17.5 and increased in Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice at E17.5 and E18.5 (Figure 5, A and B). This was not associated with alterations in cell proliferation, because proliferating (PCNA and phospho-histone H3 positive) cells are virtually undetectable in the medulla during this period in wild-type and Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice (S.C.B., data not shown). Renal medullary apoptosis was increased in Cited1P+/− mutants with placental insufficiency, whereas embryonic kidneys from Cited1M+/− mutants (with normal placental function) were indistinguishable from wild-type controls (Figure 5, C and D); therefore, placental insufficiency is associated with increased medullary apoptosis whether the embryos are heterozygous or null for Cited1, indicating that this apoptotic response is unrelated to the level of Cited1 expression in Cited1C57Bl/6 mutant embryos

Figure 5.

Apoptosis in renal medullas of Cited1C57Bl/6 mutant mice with placental insufficiency. (A) Representative images showing TUNEL staining for apoptotic nuclei in E17.5 embryonic kidneys from wild type (+/+) and Cited1 null (−/−) embryonic kidneys. (B) Graph indicates mean ± SEM apoptotic indices in embryonic kidneys isolated at E16.5, E17.5, and E18.5 from wild type and Cited1 null embryos (mouse numbers). Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA, *P < 0.05 versus wild-type controls. (C) Representative images showing TUNEL staining of E17.5 embryonic kidneys from wild-type, Cited1C57Bl/6 null, and Cited1C57Bl/6 heterozygotes with M+/− (no placental insufficiency) and P+/− (with placental insufficiency) wild-type X chromosomes. (D) Graph illustrates mean ± SEM apoptotic indices in the renal medullas of E17.5 kidneys from the same genotypes (mouse numbers). ANOVA, *P < 0.05 versus WT controls. Magnification, ×400.

Tissue Hypoxia in Cited1C57Bl/6 Mutants with Placental Insufficiency

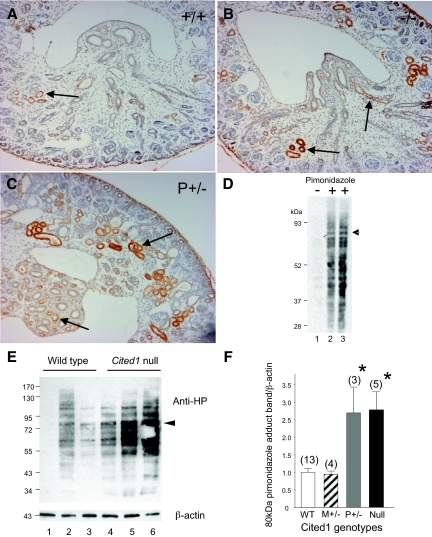

Apoptosis may be triggered by decreased tissue oxygenation associated with placental insufficiency.19,20 We therefore compared tissue oxygenation in embryonic kidneys of wild-type and Cited1C57Bl/6 mice with placental insufficiency. Hypoxia (oxygen tensions <10 mmHg) can be detected by analyzing bioreductive protein adducts of pimonidazole in embryonic tissues after intraperitoneal injection of pregnant dams.21 Using this approach, we were able to detect pimonidazole adducts in renal tubules at the corticomedullary junction, the tip of the renal medulla, and ureteric epithelium by immunohistochemical staining of E17.5 wild-type embryonic kidneys after maternal injection of pimonidazole but not in uninjected controls (Supplemental Figure 2). Comparison of E17.5 kidneys from wild-type and Cited1C57Bl/6 mutants showed increased pimonidazole-adduct formation at the corticomedullary junction and within the renal medulla of mutants with placental insufficiency (Figure 6, A through C). Analysis of pimonidazole adducts in E17.5 kidneys by Western blot revealed multiple bands only detectable after maternal injection of pimonidazole (Figure 6D). Intensity of these bands was increased in Cited1C57Bl/6 null kidneys (Figure 6E). For semiquantitative analysis, we performed densitometry on a defined 80-kD band that is distinct from other bands and detected in all of the lysates (Figure 6, D and E, arrows). The 80-kD pimonidazole band intensity was increased Cited1C57Bl/6 null and Cited1P+/− mice compared with wild-type and Cited1M+/− littermates (Figure 6F), indicating that there is decreased oxygenation of the embryonic kidneys from Cited1C57Bl/6 mutants with placental insufficiency.

Figure 6.

Renal hypoxia in Cited1C57Bl/6 mutant mice with placental insufficiency. (A through C) Representative immunohistochemical staining for pimonidazole adducts in transverse sections through E17.5 kidneys from Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice (−/−) and Cited1P+/− female heterozygotes with placental insufficiency (P+/−), compared with wild-type female (+/+) mice derived from the same litter. Tissue preparation and immunohistochemical staining were performed simultaneously under identical conditions on all three sections. Arrows indicate staining for pimonidazole adducts in inner and outer medullas. (D) Immunoblot for pimonidazole adducts in E17.5 kidney lysates obtained from wild-type embryos with or without maternal pimonidazole 2 h before killing, as indicated. Lanes 1 and 3, 10 mg of protein; lane 2, 5 mg of protein. (E) Representative Western blot illustrating changes in density of pimonidazole adduct protein bands in E17.5 kidney lysates obtained from wild-type and Cited1C57Bl/6 null embryos derived from the same litter. Arrows indicate the distinctive approximately 80-kD band that is used for quantitative densitometry. β-Actin control shown. (F) Semiquantitative analysis of E17.5 kidney pimonidazole adduct immunoblots from wild type (WT), Cited1C57Bl/6 null, and Cited1C57Bl/6 heterozygotes with M+/− and P+/− wild-type X chromosomes. Densitometry of conserved 80-kD pimonidazole adduct band corrected for β-actin loading. Each litter (n = 5) was evaluated on individual blots, and results were normalized to WT controls to correct for between-litter variations. Data are means ± SEM (mouse numbers). Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA, *P < 0.05 versus WT and Cited1M+/− controls. Magnification, ×200.

DISCUSSION

Mice with placental insufficiency associated with genetic loss of Cited1 in the placenta have renal medullary dysplasia that is first apparent during late gestation. These dysplastic changes are not caused by abnormal UB branching or lower urinary tract obstruction but are associated with decreased oxygenation and increased apoptosis in the renal medulla, which are detected only in late gestation (from E17.5). Furthermore, renal dysplasia occurs only in Cited1C57Bl/6 mutants with placental insufficiency and is not dependent on alterations in embryonic Cited1 expression. Taken together, these studies suggest that renal dysplasia is a direct consequence of decreased tissue oxygenation resulting from late gestational placental insufficiency in Cited1C57Bl/6 mutant mice. These findings provide the first direct evidence that placental insufficiency promotes renal medullary dysplasia and suggest a novel genetic model that could be used to explore the fetal mechanisms regulating renal patterning defects associated with placental insufficiency.

Our studies were performed with Cited1 mutant mice on a C57Bl/6 strain background and contrast with earlier observations indicating that renal development is normal in Cited1 null mice on a 129/Svj background.15 This is notable because Cited1 null mice on the 129/Svj background do not have placental insufficiency or IUGR.13 The explanation for this is unclear but presumably results from strain-dependent genetic modifiers.22 Important, however, is that these findings demonstrate an association between renal dysplasia and placental insufficiency in Cited1C57Bl/6 mutant mice. The time course over which this occurs (from E17.5) parallels the time course of IUGR in Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice.13 Furthermore, as Cited1 is an X-linked, paternally imprinted gene,17 comparative analysis of female Cited1C57Bl/6 heterozygotes with paternally versus maternally inherited wild-type X chromosomes indicates that renal dysplasia is associated with placental insufficiency whether the embryos are heterozygous or null for Cited1. This indicates that renal dysplasia does not depend on alteration in embryonic Cited1 expression and suggests that placental insufficiency plays a direct role in promoting renal patterning defects in these mice.

Renal medullary dysplasia has been described in a number of other mutant mouse lines. Unlike Cited1C57Bl/6 mutant mice, renal medullary dysplasia is often associated with overt defects in UB branching (Igf-1, Fgf-7, and Fgf-10 null mice23–25) or results from defects in postnatal growth and maturation of the renal medulla (angiotensinogen, Ang-1a/1b receptor, Nfat-5, and Aqp-2 null mice26–29). Glipican-3 mutant mice develop late gestational cystic dysplasia of the renal medulla.30 Like Cited1, Glipican-3 is an X-linked gene, and the renal phenotype of Glipican-3 null mice becomes progressively more severe as the mutation is backcrossed onto the C57Bl/6 background. Furthermore, these mice do not have overt UB branching defects, but, unlike Cited1C57Bl/6 mutants, they have a generalized increase in proliferation and apoptosis of UB epithelium that can be detected from E12.5 and is thought to account for the cystic dysplastic phenotype in the mice.30,31 Mice with germ-line deletion of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p57KIP2 also have a defect in renal medullary expansion and patterning that is first detectable in late gestation.32 There are no data to indicate whether this is associated with abnormalities in UB branching or proliferation; however, like Cited1 and Glipican-3, p57KIP2 is a paternally imprinted gene,33 and loss of placental p57KIP2 expression in p57KIP2 null mice and in female p57KIP2 heterozygotes with a paternally inherited wild-type allele is associated with placental insufficiency and late gestational IUGR.32,33 Furthermore, perinatal mortality associated with IUGR in p57KIP2 mutants is higher on a C57Bl/6 than on a mixed genetic background.32 This suggests that placental insufficiency could be the common underlying mechanism mediating renal medullary dysplasia in both Cited1 and p57KIP2 mutants on a C57Bl/6 background; however, p57KIP2 null mice have placental overgrowth and develop hypertension with a preeclampsia-like syndrome during pregnancy.34 This contrasts with Cited1C57Bl/6 mutants in which placental size is normal.13 Furthermore, we found no evidence that Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice developed hypertension during pregnancy (Supplemental Figure 3); therefore, although renal patterning defects may be similar, the mechanism of placental insufficiency and its impact on maternal physiology and fetal growth in the two mouse lines is likely to be different.

Our findings contrast with observations that have linked placental insufficiency with reduced nephron numbers in adults.3 This is thought to occur as decreased nutrition and/or oxygenation of the developing kidney interferes with the burst of nephron growth that occurs during the latter part of gestation. Our studies show that Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice have a minor decrease in glomerular numbers compared with their wild-type littermates, but this difference does not reach the level of statistical significance. We used a direct maceration/counting method to evaluate glomerular numbers. This is an established technique that produced reproducible results in our hands15 but lacked sensitivity to detect minor differences in glomerular numbers35; therefore, it is possible we may have failed to detect a minor, although significant, reduction in nephron numbers in Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice. Nevertheless, unlike other models of placental insufficiency, the dominant abnormality seen in Cited1C57Bl/6 mutant mice is renal medullary dysplasia. The explanation for this dominant effect on renal medullary patterning is unclear but is likely to reflect differences in severity and/or timing of placental insufficiency compared with other models. This could be relevant to human disease, because it suggests that differences in severity and/or timing of placental insufficiency could have distinct effects on fetal growth and renal patterning.

The impact of this patterning defect on the structure and function of the adult kidney in Cited1C57Bl/6 null mice was less pronounced than we expected. There was no significant alteration in renal structure, glomerular numbers, or GFR, and although urine-concentrating capacity was diminished, Cited1 mutants maintained urinary osmolalities that are sufficient to sustain life. This suggests that decreased urine-concentrating capacity results from subtle abnormalities in organization of the renal tubules/interstitium and vasa recta that affect medullary function without disrupting overall structure. This discrepancy between medullary defects in fetal and adult kidneys may result from selection bias if mice that die postnatally have more severe renal dysplasia than the survivors. This is consistent with the variable penetrance of renal dysplasia seen in Cited1C57Bl/6 null embryos; however, we were unable to test this hypothesis because the majority of Cited1C57Bl/6 mutants with placental insufficiency that die cannot be analyzed because death occurs within a few hours of birth.13 An alternative explanation for our findings is that much of the structural defect that is apparent in utero is lost postnatally. This would occur if postnatal expansion of the medulla progresses normally in Cited1C57Bl/6 mutants despite an initial delay in patterning of the medulla in utero. On this basis, persistent abnormalities in organization of the renal medulla might result from a developmental delay in renal medullary growth, whereas gross defects in medullary patterning are lost by the time the surviving mice reach adulthood.

Finally, our studies show that there is increased apoptosis and decreased oxygenation of the renal medulla in Cited1C57Bl/6 mutants with placental insufficiency. A number of other models of IUGR showed increased apoptosis in growth restricted organs.19,20,36–39 This is thought to result from nutritional and/or oxygen deficiency promoting stress-induced proapoptotic responses. Previous studies also showed increased apoptosis in the renal medullary interstitium of human embryonic kidneys with medullary dysplasia40,41; therefore, our studies suggest that placental insufficiency causes renal medullary dysplasia by promoting hypoxia-induced apoptosis at a critical stage of renal medullary development.

CONCISE METHODS

Mouse Line and Breeding Strategies

We maintain a colony of Cited1 mutants (Cited1tm1Dunw)13 on a pure C57Bl/6 background (after backcrossing seven generations). These are referred to as Cited1C57Bl/6 mice in the text. Because both Cited1C57Bl/6 null and P+/− female heterozygotes have reduced viability,13 we maintain this colony by breeding wild-type C57Bl/6 females with Cited1C57Bl/6 null males. Comparison between Cited1C57Bl/6 null and wild-type mice (both adult and embryonic studies) was performed on offspring derived from crossing Cited1C57Bl/6 heterozygous females with wild-type males. Comparison between female Cited1C57Bl/6 heterozygotes with paternal (Cited1P+/− with placental insufficiency) and maternal (Cited1M+/− with normal placental function) inherited wild-type X chromosomes was performed on offspring from female Cited1M+/− heterozygotes to limit potentially confounding effects of maternal genotype on embryonic growth. These were mated either with wild-type males (expected genotypes 25% female Cited1P+/−, 25% wild type female, 25% wild-type male, and 25% null male) or Cited1C57Bl/6 null males (expected genotypes 25% female Cited1M+/− without placental insufficiency, 25% null female, 25% null male, and 25% wild-type male). The main analysis involved side-by-side comparison between female Cited1P+/− and Cited1M+/− heterozygotes, but other expected genotypes provided internal controls for each litter. Timed pregnancies were performed with the morning of the vaginal plug counted as 0.5 d post coitus (referred to as E0.5). Embryonic heads and adult tails were used for genotyping using primers to detect Cited1 mutant alleles and the Y and X chromosome–specific forms of smooth muscle cells for sex determination in embryos.13,42

Preparation of Renal Tissue and Quantification of UB Tips and Glomerular Numbers

Kidneys isolated from E15.5 to E18.5 embryos were fixed for 1 to 2 h in 10% formalin at 4°C before processing and mounting in paraffin. Serial sagittal sections (5 μM) were cut on Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher, PA) and evaluated under an inverted microscope: Only sections cut through the medulla (assessed from appearance of the renal pelvis and/or evidence of longitudinal sectioning through proximal collecting ducts) were used for subsequent analysis. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and immunohistochemical and TUNEL assays were performed as outlined in TUNEL Staining and Assessment of Apoptotic Indices. Staining for pimonidazole protein adducts was performed on transverse sections through the renal medullas of E17.5 embryos. For quantification of UB tips in E15.5 kidneys, Calbindin D28K–positive UB tips were counted in the outer nephrogenic zone by a blinded observer (M.P.d.C.). Sections (5 μM) were evaluated every 10th section around the future medulla (as determined by the presence of proximal ureteric stalks), and results are expressed as the mean of at least three values (three to six sections counted per kidney). Glomeruli were counted in adult kidneys using a direct maceration/counting method, as described previously.15 For this, kidneys were minced into 2-mm cubes, and the fragments were incubated in 5 ml of 6 M HCl at 37°C for 90 min. Tissue was homogenized through repeated pipetting, and 25 ml of water was added. After overnight incubation at 4°C, glomeruli in 5 × 1 ml of this solution were counted in a 35-mm counting dish (cat. no. 174926; Nalgen, RI). Total glomerular number per kidney was extrapolated mathematically from the mean of these five counts. For metanephric organ cultures, E12.5 kidneys were isolated and grown for 3 d on Transwell filters, as described previously.15 Filters were fixed in cold methanol for 10 min before immunostaining, as outlined in Immunohistochemistry. Individual Calbindin D28K UB tips were counted directly from photomicrographs by a blinded observer (M.P.d.C.).

Assessment of Ureter Patency

E18.5 kidneys, ureters, and bladder were isolated en block, and the renal pelvises were punctured with a 30-G needle and injected manually with 10 mg/ml methylene blue at approximately 100 μl/min, as described previously.43 Images of whole-mount preparations illustrate dye passage along the ureter.

Assessment of Tissue Oxygenation

Renal tissue oxygenation (oxygen tensions <10 mmHg) was evaluated by detecting bioreductive protein adducts of pimonidazole hydrochloride (Hypoxyprobe; Millipore, Billerica, MA) in embryonic tissues after intraperitoneal injection of pregnant dams, as described previously.21 For this, E17.5 pregnant dams were injected with 60 mg/kg pimonidazole 2 h before dissection. Mothers were killed by cervical dislocation after isofluorane, the uterus was isolated, and embryos were dissected while maintained in ice-cold PBS to minimize postmortem formation of new pimonidazole adducts. For prevention of variability in postmortem effects between littermates, embryonic kidneys isolated from each litter were kept in ice-cold PBS until all of the embryos had been dissected and then were simultaneously snap-frozen for Western blot analysis or fixed in ice-cold 10% formalin for 2 h for immunohistochemical analysis, as outlined in Immunohistochemistry. For Western blot analysis, snap-frozen kidneys were lysed in RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS) and 10 μg of lysate protein separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and probed with FITC-conjugated mouse anti–Hypoxyprobe-1 followed by a secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated mouse anti-FITC (both antibodies from Chemicon). After development of the films, membranes were stripped and reprobed with mouse anti–β-actin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) as a control for protein loading. Quantification of pimonidazole adducts was performed by densitometry of the constant 80-kD protein band, expressed as the ratio of band density to the β-actin control. Results were normalized to the wild-type littermate controls for each of the litters to allow for between-litter variations.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue sections were deparaffinized, and antigen retrieval was performed by heating slides in sodium citrate buffer (Biogenex, San Roman, CA). Sections were blocked with avidin/biotin blocking reagents (Vectastain kit) followed by block for nonspecific antibody binding using mouse-on-mouse (MOM) blocking reagent (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) or 10% goat serum in PBS for rabbit primary antibodies. In addition, 0.5% hydrogen peroxide was added to inhibit endogenous peroxidases. Primary antibodies were incubated in the respective blocking reagents and detected using species specific biotinylated antibodies and the ABC system (Vector Laboratories) or HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. α-Smooth muscle actin was detected using mouse anti–α-smooth muscle actin (Dako M0851; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) incubated at 1:50 in MOM diluent for 1 h at room temperature. Pimonidazole adducts were detected using FITC-conjugated Hypoxyprobe-1 mouse mAb (Chemicon 90531) in MOM diluent for 30 min at room temperature and detected using HRP-conjugated mouse anti-FITC mAb (Chemicon 90532). Calbindin D28K was detected using rabbit ant[an]Calbindin D28K (Calbiochem PC-2532; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) at 1:100 overnight at 4°C. For immunofluorescence analysis of Calbindin D28K expression in cultured metanephroi, methanol fixed explants were incubated with the same primary antibody overnight in Tris-buffered saline (25 mM Tris base with 100 mM NaCl) with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) with 10% goat serum, washed three times for 1 h in TBST the following day, and incubated with Cy2-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson Immunological Research 711225152; JAX, West Grove, PA) at 1:50 in TBST without serum for an additional hour before washing and mounting with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories).

TUNEL Staining and Assessment of Apoptotic Indices

We used an FITC-labeling in situ TUNEL detection kit (Roche 11684795910 Roche Laboratories, Ontario, CA) to detect apoptotic cells in embryonic renal medullas. Briefly, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized and treated with 20 μg/ml Proteinase K for 15 min at room temperature, and apoptosis-associated 3′ hydroxyl-DNA terminal overhangs were labeled by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–dependent incorporation of FITC-conjugated nucleotides. Slides were mounted in medium containing 4′-6′ diamino-2-phenyllindole (DAPI) to label nuclei (Vector Laboratories). Apoptotic indices were evaluated by epifluorescence microscopy. For this, a blinded observer (S.C.B.) determined the total number of FITC-positive nuclei out of approximately 800 DAPI-positive nuclei in the medulla and inner cortex of sections cut through the renal pelvis. Results were expressed as the percentage of FITC/TUNEL positive to total DAPI staining nuclei.

Renal Function Tests

GFR was determined by plasma clearance kinetics of FITC after a single bolus intravenous injection of FITC-inulin (Sigma), as described previously.44 Urine-concentrating capacity was determined by collecting spot urine samples for osmolality before (10:00 am), after 23 h of water deprivation, or 4 h after water deprivation and intraperitoneal injection of 1 ng/g desmopressin (Sigma). Urine samples were prepared and osmolalities were measured using the Advanced Micro Osmometer Model 3300 (Advanced Instruments, Norwood, MA) as described previously.45

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by t test for paired group comparisons or one-way ANOVA for comparison between multiple groups using Bonferroni correction or post hoc, pair-wise, between-group comparisons for sample sizes of five or more per group. Smaller sample sizes (four or fewer per group) were compared using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA test with Siegel (Bonferroni) correction for post hoc pair-wise contrasts. The minimal level of significance was set at P < 0.05, and statistical analyses were performed using Analyze-It 1.73 for Microsoft Excel.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 DK61558 and P50 DK39261 (M.P.d.C.) and T32 HD007502 (S.C.B.), a Westfield-Belconnen Fellowship (D.B.S.), a Pfizer Foundation Australia Senior Research Fellowship (S.L.D.), and a NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (S.L.D.).

We thank Robert Lane for helpful advice and comments, Zhonghua Qi from the Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Core at Vanderbilt for performing the FITC-inulin clearance studies, and Annabelle Scott for technical assistance.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at http://www.jasn.org/.

References

- 1.Henriksen T, Clausen T: The fetal origins hypothesis: Placental insufficiency and inheritance versus maternal malnutrition in well-nourished populations. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 81: 112–114, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eleftheriades M, Creatsas G, Nicolaides K: Fetal growth restriction and postnatal development. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1092: 319–330, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker DJ, Bagby SP: Developmental antecedents of cardiovascular disease: A historical perspective. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2537–2544, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Godfrey KM: The role of the placenta in fetal programming: A review. Placenta 23[Suppl A]: S20–S27, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cebrian C, Borodo K, Charles N, Herzlinger DA: Morphometric index of the developing murine kidney. Dev Dyn 231: 601–608, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertram JF, Young RJ, Spencer K, Gordon I: Quantitative analysis of the developing rat kidney: Absolute and relative volumes and growth curves. Anat Rec 258: 128–135, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briscoe TA, Rehn AE, Dieni S, Duncan JR, Wlodek ME, Owens JA, Rees SM: Cardiovascular and renal disease in the adolescent guinea pig after chronic placental insufficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol 191: 847–855, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suranyi A, Pal A, Streitman K, Pinter S, Kovacs L: Fetal renal hyperechogenicity in pathological pregnancies. J Perinat Med 25: 274–279, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suranyi A, Streitman K, Pal A, Nyari T, Retz C, Foidart JM, Schaaps JP, Kovacs L: Fetal renal artery flow and renal echogenicity in the chronically hypoxic state. Pediatr Nephrol 14: 393–399, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiara A, Chirico G, Comelli L, De Vecchi E, Rondini G: Increased renal echogenicity in the neonate. Early Hum Dev 22: 29–37, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pohl M, Bhatnagar V, Mendoza SA, Nigam SK: Toward an etiological classification of developmental disorders of the kidney and upper urinary tract. Kidney Int 61: 10–19, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson D, Weiner CP, Nakamura KT, Robillard JE: Effect of intrauterine growth retardation on renal function on day one of life. Am J Perinatol 7: 343–346, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez TA, Sparrow DB, Scott AN, Withington SL, Preis JI, Michalicek J, Clements M, Tsang TE, Shioda T, Beddington RS, Dunwoodie SL: Cited1 is required in trophoblasts for placental development and for embryo growth and survival. Mol Cell Biol 24: 228–244, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunwoodie SL, Rodriguez TA, Beddington RS: Msg1 and Mrg1, founding members of a gene family, show distinct patterns of gene expression during mouse embryogenesis. Mech Dev 72: 27–40, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyle S, Shioda T, Perantoni AO, de Caestecker M: Cited1 and Cited2 are differentially expressed in the developing kidney but are not required for nephrogenesis. Dev Dyn 236: 2321–2330, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howlin J, McBryan J, Napoletano S, Lambe T, McArdle E, Shioda T, Martin F: CITED1 homozygous null mice display aberrant pubertal mammary ductal morphogenesis. Oncogene 25: 1532–1542, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenner MH, Parrish JE, Boyd Y, Reed V, MacDonald M, Nelson DL, Isselbacher KJ, Shioda T: MSG1 (melanocyte-specific gene 1): Mapping to chromosome Xq13.1, genomic organization, and promoter analysis. Genomics 51: 401–407, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papaioannou VE, West JD: Relationship between the parental origin of the X chromosomes, embryonic cell lineage and X chromosome expression in mice. Genet Res 37: 183–197, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lane RH, Ramirez RJ, Tsirka AE, Kloesz JL, McLaughlin MK, Gruetzmacher EM, Devaskar SU: Uteroplacental insufficiency lowers the threshold towards hypoxia-induced cerebral apoptosis in growth-retarded fetal rats. Brain Res 895: 186–193, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burke C, Sinclair K, Cowin G, Rose S, Pat B, Gobe G, Colditz P: Intrauterine growth restriction due to uteroplacental vascular insufficiency leads to increased hypoxia-induced cerebral apoptosis in newborn piglets. Brain Res 1098: 19–25, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nanka O, Valasek P, Dvorakova M, Grim M: Experimental hypoxia and embryonic angiogenesis. Dev Dyn 235: 723–733, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linder CC: Genetic variables that influence phenotype. ILAR J 47: 1321–1340, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogers SA, Powell-Braxton L, Hammerman MR: Insulin-like growth factor I regulates renal development in rodents. Dev Genet 24: 293–298, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohuchi H, Hori Y, Yamasaki M, Harada H, Sekine K, Kato S, Itoh N: FGF10 acts as a major ligand for FGF receptor 2 IIIb in mouse multi-organ development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 277: 643–649, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiao J, Uzzo R, Obara-Ishihara T, Degenstein L, Fuchs E, Herzlinger D: FGF-7 modulates ureteric bud growth and nephron number in the developing kidney. Development 126: 547–554, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niimura F, Labosky PA, Kakuchi J, Okubo S, Yoshida H, Oikawa T, Ichiki T, Naftilan AJ, Fogo A, Inagami T, et al.: Gene targeting in mice reveals a requirement for angiotensin in the development and maintenance of kidney morphology and growth factor regulation. J Clin Invest 96: 2947–2954, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsuchida S, Matsusaka T, Chen X, Okubo S, Niimura F, Nishimura H, Fogo A, Utsunomiya H, Inagami T, Ichikawa I: Murine double nullizygotes of the angiotensin type 1A and 1B receptor genes duplicate severe abnormal phenotypes of angiotensinogen nullizygotes. J Clin Invest 101: 755–760, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez-Rodriguez C, Antos CL, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Lin F, Novobrantseva TI, Bronson RT, Igarashi P, Rao A, Olson EN: Loss of NFAT5 results in renal atrophy and lack of tonicity-responsive gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 2392–2397, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang B, Gillespie A, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Verkman AS: Neonatal mortality in an aquaporin-2 knock-in mouse model of recessive nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Biol Chem 276: 2775–2779, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cano-Gauci DF, Song HH, Yang H, McKerlie C, Choo B, Shi W, Pullano R, Piscione TD, Grisaru S, Soon S, Sedlackova L, Tanswell AK, Mak TW, Yeger H, Lockwood GA, Rosenblum ND, Filmus J: Glypican-3-deficient mice exhibit developmental overgrowth and some of the abnormalities typical of Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome. J Cell Biol 146: 255–264, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grisaru S, Cano-Gauci D, Tee J, Filmus J, Rosenblum ND: Glypican-3 modulates BMP- and FGF-mediated effects during renal branching morphogenesis. Dev Biol 231: 31–46, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang P, Liegeois NJ, Wong C, Finegold M, Hou H, Thompson JC, Silverman A, Harper JW, DePinho RA, Elledge SJ: Altered cell differentiation and proliferation in mice lacking p57KIP2 indicates a role in Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Nature 387: 151–158, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsuoka S, Thompson JS, Edwards MC, Bartletta JM, Grundy P, Kalikin LM, Harper JW, Elledge SJ, Feinberg AP: Imprinting of the gene encoding a human cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, p57KIP2, on chromosome 11p15. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93: 3026–3030, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanayama N, Takahashi K, Matsuura T, Sugimura M, Kobayashi T, Moniwa N, Tomita M, Nakayama K: Deficiency in p57Kip2 expression induces preeclampsia-like symptoms in mice. Mol Hum Reprod 8: 1129–1135, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bertram JF: Counting in the kidney. Kidney Int 59: 792–796, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baserga M, Hale MA, Ke X, Wang ZM, Yu X, Callaway CW, McKnight RA, Lane RH: Uteroplacental insufficiency increases p53 phosphorylation without triggering the p53-MDM2 functional circuit response in the IUGR rat kidney. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R412[en[R418, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baserga M, Bertolotto C, Maclennan NK, Hsu JL, Pham T, Laksana GS, Lane RH: Uteroplacental insufficiency decreases small intestine growth and alters apoptotic homeostasis in term intrauterine growth retarded rats. Early Hum Dev 79: 93–105, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyatt MA, Gopalakrishnan GS, Bispham J, Gentili S, McMillen IC, Rhind SM, Rae MT, Kyle CE, Brooks AN, Jones C, Budge H, Walker D, Stephenson T, Symonds ME: Maternal nutrient restriction in early pregnancy programs hepatic mRNA expression of growth-related genes and liver size in adult male sheep. J Endocrinol 192: 87–97, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pham TD, MacLennan NK, Chiu CT, Laksana GS, Hsu JL, Lane RH: Uteroplacental insufficiency increases apoptosis and alters p53 gene methylation in the full-term IUGR rat kidney. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 285: R962–R970, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winyard PJ, Nauta J, Lirenman DS, Hardman P, Sams VR, Risdon RA, Woolf AS: Deregulation of cell survival in cystic and dysplastic renal development. Kidney Int 49: 135–146, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Winyard PJ, Risdon RA, Sams VR, Dressler GR, Woolf AS: The PAX2 tanscription factor is expressed in cystic and hyperproliferative dysplastic epithelia in human kidney malformations. J Clin Invest 98: 451–459, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mroz K, Carrel L, Hunt PA: Germ cell development in the XXY mouse: Evidence that X chromosome reactivation is independent of sexual differentiation. Dev Biol 207: 229–238, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu OH, Murawski IJ, Myburgh DB, Gupta IR: Overexpression of RET leads to vesicoureteric reflux in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F1123–F1130, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qi Z, Whitt I, Mehta A, Jin J, Zhao M, Harris RC, Fogo AB, Breyer MD: Serial determination of glomerular filtration rate in conscious mice using FITC-inulin clearance. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F590–F596, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moeckel GW, Zhang L, Chen X, Rossini M, Zent R, Pozzi A: Role of integrin alpha1beta1 in the regulation of renal medullary osmolyte concentration. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F223–F231, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]