Abstract

Tubulointerstitial injury leading to fibrosis is a common pathway of many renal diseases. During this type of injury, modeled by unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO), cells undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process that is mediated by various cytokines that modulate the biology of extracellular matrix proteins. Here, we studied the tubulointerstitial nephritis antigen (TINag), a tubular basement membrane protein, in the UUO model of tubulointerstitial injury. We observed upregulation of type IV collagen but downregulation of both laminin and TINag in obstructed kidneys. TINag downregulation was a result of oxidative stress; in the proximal tubular epithelial cell line HK-2, TINag expression and its promoter activity decreased after treatment with H2O2. We identified multiple CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β (C/EBP-β) motifs in the TINag promoter and observed that oxidant stress perturbed interactions between TINag DNA and C/EBP-β protein. Oxidant stress reduced nuclear translocation of C/EBP-β in HK-2 cells, which was restored by antioxidants. In addition, overexpression of C/EBP-β restored the H2O2-induced reduction of TINag promoter activity and expression. Furthermore, in vivo, renal obstruction reduced nuclear expression of C/EBP-β. Cells grown on a TINag substratum maintained their normal epithelial phenotype and cytoskeletal organization, similar to those grown on type IV collagen, and demonstrated reduced synthesis of fibronectin. Taken together, these findings suggest that altered interactions between C/EBP-β and TINag play a critical role in the pathophysiology of renal injury after obstruction.

Tubulointerstitial injury invariably occurs in many forms of chronic progressive renal diseases, irrespective of the fact that the primary target of the assault is confined to glomerular, tubular, interstitial, or vascular compartments of the kidney.1 Expected, the injury to the last three compartments can be readily envisioned to lead to chronic progressive tubulointerstitial fibrosis by a wide variety of mechanisms; however, very often a sustained glomerular injury, even manifesting as a proteinuria alone, has been seen to be associated with tubulointerstitial fibrosis with a proportionate decline in renal functions.2–4 Chronic tubulointerstitial injury implies a loss of tubules accompanied with fibrosis related to excessive synthesis of extracellular matrix (ECM) by the interstitial cells.5,6 Recently emerged is another novel biologic precept, which suggests that such an injury may in part be due to the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of tubular cells after their migration through the tubular basement membrane (TBM) into the interstitium.7–9 Here, the ECM proteins that are affected include collagens, laminins, entactin, fibronectin, and osteopontin. Type IV collagen, laminin, and entactin are integral parts of the TBMs.10 Tubulointerstitial nephritis antigen (TINag) is another integral component of the TBM whose relevance in tubulointerstitial diseases remains largely unexplored.11–13

The TINag is an approximately 58-kD glycoprotein, and it was discovered in transplant patients with progressive tubulointerstitial nephritis that had circulating anti-TBM antibodies.12–14 Its selective expression in cortical TBMs suggests that it may contribute to certain specific structural/functional properties of the TBMs. A few reports suggested that TINag may promote cell adhesion by interacting with type IV collagen and laminin.15 Because TINag can also interact with certain integrins, such as α3β1/αvβ3, it may play a role in the biology of tubular cells that are intricately linked to the pathogenesis of tubulointerstitial diseases.16 Among various models of tubulointerstitial diseases, the widely studied one includes unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) model.17 This model is a good prototypic example that attests to the notion of EMT in chronic progressive renal diseases with increased expression of certain TBM-ECM glycoproteins (type IV collagen and laminin).7,8,18 Because TINag was originally incriminated in the pathogenesis of tubulointerstitial diseases,12,13 studies were initiated to examine its status in UUO model and to delineate various transcriptional versus translational mechanisms that modulate its biology.

RESULTS

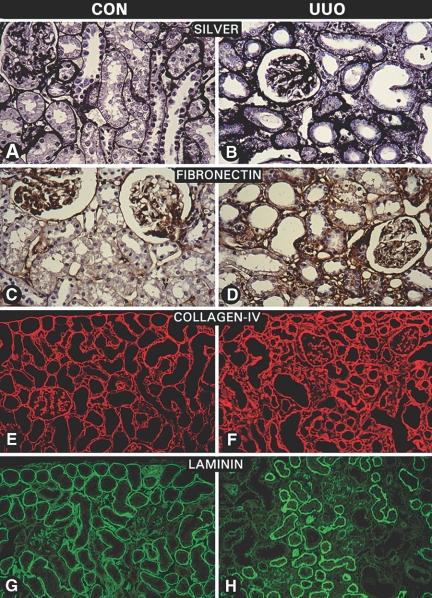

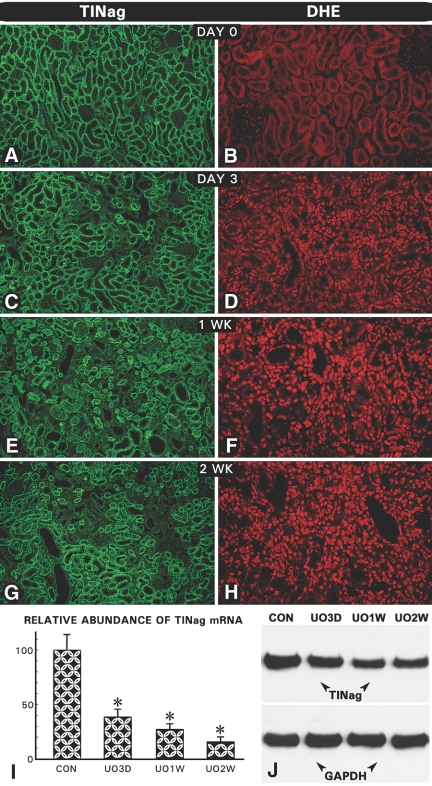

Morphologic Changes and Status of ECM Proteins Relative to TINag Expression in Kidneys of UUO Rats

Tubulointerstitial fibrosis is characteristically seen after 2 to 3 wk in the UUO animal model,17–19 and similar observations were made in this study as highlighted by silver staining of kidney sections (Figure 1, B versus A). Among the ECM proteins, the expression of fibronectin and type IV collagen was increased in the interstitial compartment and TBMs, respectively (Figure 1, D versus C, and F versus E), whereas there was a focal loss of laminin in regions with interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (Figure 1, H versus G). The in situ TINag protein expression was not observed in glomeruli, and it decreased progressively 3, 7, and 14 d after ligation in the TBMs (Figure 2, C, E, and G), compared with the control at day 0 (Figure 2A). Expression was undetectable in atrophic or dilated tubules (Figure 2G). Similarly, the TINag mRNA and protein expression was decreased progressively (Figure 2, I and J). The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression was unchanged. These changes were associated with gradual increase in dihydroethidium (DHE) nuclear staining, suggesting that the nascent oxygen radicals (e.g., O2·−) were generated during the course of UUO and bound to DNA to yield fluorophore staining (Figure 2, D, F, and H versus B). To delineate mechanisms that could establish a relationship between the altered TINag expression and oxidant stress, we performed studies using a HK-2 proximal tubular epithelial cell line.

Figure 1.

Morphologic changes and expression of ECM proteins after UUO. (A and B) Silver methenamine staining showed a notable expansion of the interstitial compartment and thickening of the TBM in UUO rats. (C through F) Expression of fibronectin and type IV collagen was increased, whereas no significant change was observed in the glomerular compartment after 2 to 3 wk of UUO. (G and H) Expression of laminin was decreased in regions showing interstitial fibrosis and in areas with tubular atrophy and dilation.

Figure 2.

Sequential changes in expression of TINag and DHE staining after UUO. (A, C, E, and G) TINag expression decreased progressively 3, 7, and 14 d after UUO. No expression was seen in tubules that underwent atrophy and dilation at 2 to 4 wk. Expression of TINag was absent in the glomeruli of both control and UUO rats. (I and J) TINag mRNA and protein expression also decreased progressively. Expression of GAPDH remained unchanged. (B, D, F, and H) A progressive increase in the DHE nuclear staining was observed from day 3 onward in UUO rats (n = 5; P < 0.001).

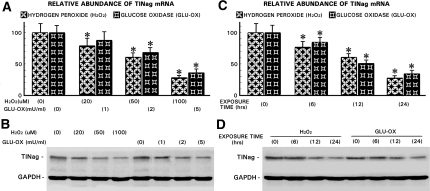

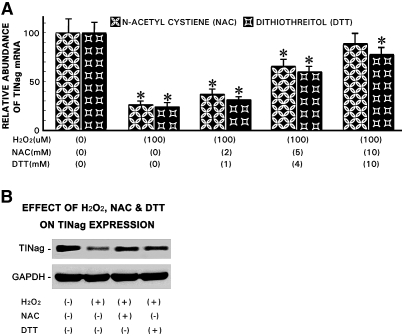

Oxidant Stress Decreases Expression of TINag Protein and mRNA in HK-2 Cells

A dosage-dependent decrease in TINag expression was observed in HK-2 cells treated with H2O2 (0 to 100 μM) and glucose oxidase (0 to 5 mU/ml), and the reduction was progressive over a period of 24 h (Figure 3). At 24 h, TINag expression was reduced to approximately 30% at concentrations of 100 μM and 5 mU/ml for H2O2 and glucose oxidase, respectively. At these optimal concentrations and timely exposure of H2O2, the cell viability remained >95%. For the specificity of the effect of oxygen radicals on TINag expression, cells were incubated with either N-acetyl cysteine (NAC; 0 to 10 mM) or dithiothreitol (DTT; 0 to 10 mM) for 1 h before H2O2 exposure. The treatment of both of the antioxidants (NAC and DTT) led to a significant amelioration of the O2·−-mediated reduction of TINag expression (Figure 4). Amelioration with NAC seemed to be relatively more effective.

Figure 3.

Oxidant stress decreases expression of TINag protein and mRNA in HK-2 cells. (A and B) A dosage-dependent decrease in TINag mRNA and protein expression was observed in HK-2 cells treated with H2O2 (0 to 100 μM) or glucose oxidase (GLU-OX; 0 to 5 mU/ml). GAPDH expression was unaffected. (C and D) Similarly, a progressive decrease of TINag mRNA and protein expression was observed with increasing duration of HK-2 cells exposure to H2O2 or GLU-OX, whereas GAPDH was unaffected. Treatment with H2O2 was relatively more effective in reducing TINag expression (n = 5; P < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Amelioration of oxidant stress on TINag expression with NAC or DTT treatment. (A and B) Both NAC (0 to 10 mM) and DTT (0 to 10 mM) normalized TINag mRNA and protein expression in a dosage-dependent manner in HK-2 cells that underwent oxidant stress with 100 μM H2O2. Amelioration was relatively more effective with NAC treatment (n = 5; P < 0.001).

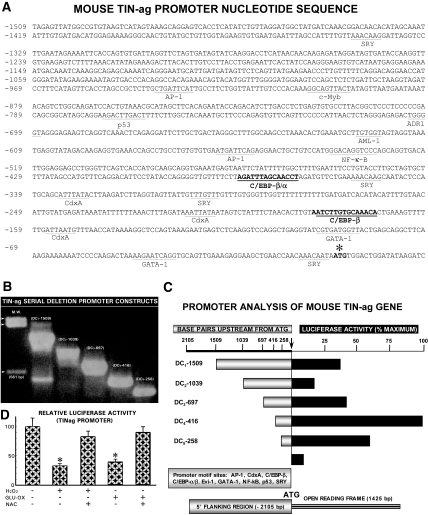

Oxidative Stress Decreases Promoter Activity of Mouse TINag via C/EBP-β Binding Motif

TINag promoter analyses revealed three CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β (C/EBP-β) motifs, two of which localized within the −400 bp flanking the open reading frame. In addition, a number of other important motifs (e.g., ectopic viral integration site I encoded factor) were found (Figure 5A). To investigate the transcriptional regulation of TINag, we generated various deletion constructs (DC1 through DC5) in pGL3 basic vector (Figure 5B). Their analyses indicated that the basal reporter luciferase activity was mainly confined to the DC4 and DC5 constructs, which included two C/EBP-β motifs (Figure 5C). Luciferase activity was reduced in all of the deletion constructs (DC1 through DC5) but more so in DC4 and DC5 containing binding sites for C/EBP-β upon exposure of HK-2 cells to H2O2 or glucose oxidase. Thus, for further studies, the DC4 construct was used. Luciferase activity was largely restored by exposure of cells to antioxidant NAC (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Oxidative stress decreases promoter activity of mouse TINag. (A) The isolated 2-kb promoter fragment of TINag revealed multiple motifs, including two C/EBP-β and GATA-1 motifs localized within the 400-bp flanking the open reading frame. (B) Various deletion constructs (DC1 through DC5) with varying size (258 through 1509 bp) inserts subcloned into pGL3 basic vector. (C) Luciferase activity in various deletion constructs (DC1 through DC5), the highest activity being confined to the DC4. (D) Oxidant stress induced either by H2O2 or GLU-OX considerably reduced promoter activity in DC4-transfected HK-2 cells, and it was largely restored after NAC treatment (n = 5; P < 0.001).

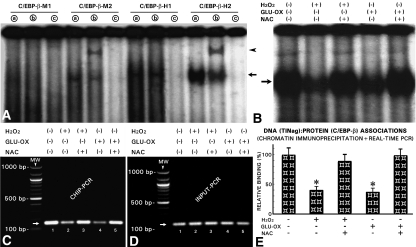

Emphasis was placed on C/EBP-β binding motifs because their sequences (NKNTTGCNYA AYNN) are present in various ECM genes and they regulate their transcription.20,21 Conceivably, C/EBP-β could modulate the regulation of TINag as well because its expression has been reported to be influenced by oxidative stress.22 We synthesized four 30 mer-oligos inclusive of putative C/EBP-β binding motifs specific to murine (C/EBP-β-M1 and C/EBP-β-M2) and human (C/EBP-β-H1 and C/EBP-β-H2). The electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) revealed binding with the nucleoproteins when we used C/EBP-β-M2, C/EBP-β-H1, and C/EBP-β-H2, as indicated by the presence of a high molecular band (Figure 6A, lanes a, arrow). Use of anti–C/EBP-β antibody resulted in a shift of DNA–protein complexes to higher position and yielded a distinct band (Figure 6A, lanes b, arrowhead); however, this supershifted band was visualized only when we used C/EBP-β-M2 and C/EBP-β-H2 oligos, suggesting that the TINag promoter activity relevant to oxidant stress is confined to its immediate 5′-flanking region. To test this contention, we used either C/EBP-β-M2 or C/EBP-β-H2 oligo in experiments in which cells had undergone oxidant stress. By EMSA, we observed a decrease in the intensity of the shifted bands compared with the control (Figure 6B, arrow, lanes 2 and 4 versus 1). The band intensity was restored to normal levels with NAC treatment (Figure 6B, lanes 3 and 5 versus 1, arrow).

Figure 6.

Oxidative stress decreases promoter activity of mouse TINag via C/EBP-β–binding motif. (A) EMSAs revealed formation of DNA (TINag)–protein (transcription factor) complexes when oligos with consensus sequences of C/EBP-β motifs specific to murine (C/EBP-β-M2) and human (C/EBP-β-H1 and C/EBP-β-H2) were used, as indicated by the visualization of a high molecular band (lanes a, arrow). The C/EBP-β-M1 oligo did not yield any high molecular weight band. Immunoprecipitation of oligo/nuclear extract with anti–C/EBP-β antibody resulted in a shift of the DNA–protein complexes to higher position, and a distinct supershifted band was visualized (lanes b, arrowhead). This band was visualized only with C/EBP-β-M2 and C/EBP-β-H2 oligos. No high molecular weight band was observed when 10× excess unlabeled oligos were used (lanes c). (B) EMSA revealed a reduction in the intensity of shifted band in cells treated either with H2O2 or GLU-OX (lanes 2 and 4 versus 1, arrow). The reduced band intensity was restored with the treatment of NAC (lanes 3 and 5). (C) ChIP-PCR procedures revealed perturbed DNA–protein interactions by the oxidant stress, as revealed by the reduced intensity of the PCR band (lanes 2 and 4 versus 1, arrow). NAC treatment restored these interactions (lanes 3 and 5). (D) No change was observed in INPUT-PCR. (E) Quantification of DNA–protein associations, as assessed by real-time qPCR analyses, confirmed the reduction in such associations with H2O2 and GLUC-OX and normalization with NAC treatment (n = 5; P < 0.001).

To confirm perturbation in DNA–protein interactions by oxidant stress we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) followed by PCR. We subjected immuoprecipitated DNA (TINag)–protein (C/EBP-β) complexes with anti–C/EBP-β antibody to PCR using specific primers spanning −684 to −532 bp of the TINag, with the yield of an approximately 150-bp product (Figure 6C, lane 1, arrow). The band intensity was reduced in cells treated with H2O2 and glucose oxidase (Figure 6C, lanes 2 and 4). This decrease was largely normalized with NAC treatment (Figure 6C, lanes 3 and 5). Band intensities were similar in input-PCR analyses for different variables (Figure 6D, lanes 1 through 5, arrow). Quantification of DNA–protein associations was assessed by real-time quantitative (qPCR) analyses. The results confirmed the qualitative observations that a reduction in DNA–protein associations occurs under oxidant stress, and the NAC treatment normalizes these interactions (Figure 6E).

Oxidative Stress Perturbs Expression and Nuclear Translocation of C/EBP-β in Tubular Cells

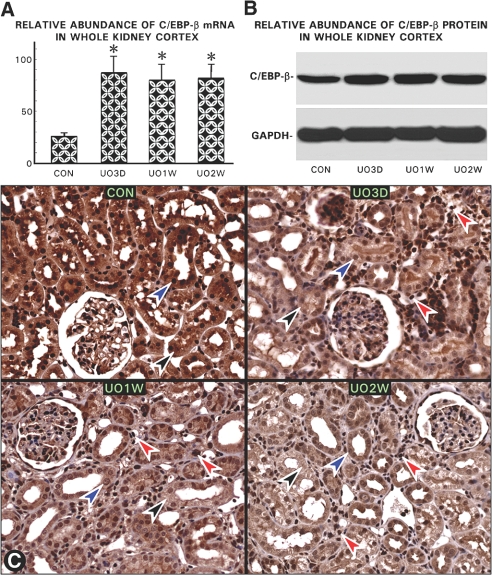

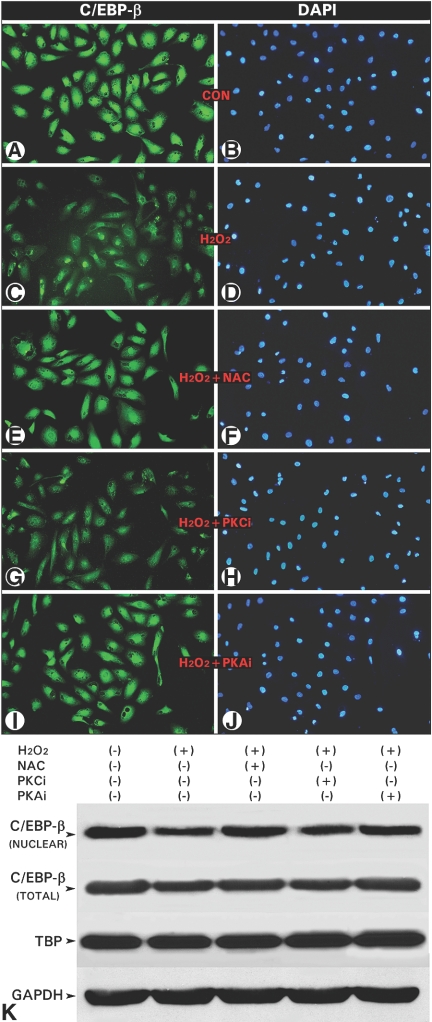

Both the mRNA and protein expression of C/EBP-β was increased in the renal cortex of the UUO kidneys at day 3, and it was sustained for 2 to 3 wk (Figure 7, A and B); however, by in situ immunohistochemical analyses, a progressive decrease in the C/EBP-β expression was noted in the cytoplasm (black arrowheads) and more so in the nuclei (blue arrowheads) of the cortical tubules in UUO kidneys commencing from day 3 onward (Figure 7C). During this time frame, there was a marked infiltration of leukocytes (Figure 7C, red arrowheads) with intense nuclear immunoreactivity, suggesting that increase in the C/EBP-β expression in the whole cortical homogenate may be attributable to the influxed inflammatory cells rather than its increase in the tubular cells. To confirm this contention, we exposed HK-2 cells to H2O2 and treated them with either NAC or inhibitors of protein kinase C (PKCi) or PKA (PKAi) and then stained them with anti–C/EBP-β and DAPI. The H2O2 exposure reduced nuclear fluorescence for C/EBP-β (Figure 8, C versus A), which was restored with NAC and PKAi treatments (Figure 8, E and I), whereas PKCi had no effect (Figure 8G). Immunoblot analyses showed a decreased C/EBP-β nuclear expression with H2O2 with a minimal effect on the total cellular expression, suggesting a reduced phosphorylation and consequential nuclear translocation under states of oxidant stress (Figure 8K). Similar to the observations made in in situ cellular immunofluorescence studies, the NAC and PKAi restored nuclear translocation, whereas PKCi had a minimal effect (Figure 8K). The cytosolic GAPDH and nuclear expression of TATA binding protein were unchanged.

Figure 7.

Oxidative stress perturbs expression and nuclear translocation of C/EBP-β in tubular cells. (A and B) An abrupt increase in the C/EBP-β mRNA and protein expression was observed in UUO kidneys at day 3, and it remained elevated up to 2 to 4 wk. GAPDH expression was unaltered. (C) By in situ immunohistochemical analyses, a progressive decrease in the C/EBP-β expression was noted in the cytoplasm (black arrowheads) but remarkably more so in the nuclei (blue arrowheads) of the tubules in UUO kidneys from day 3 onward compared with control; however, during the time frame of UUO, there was a marked infiltration of leukocytes (red arrowheads) with a marked immunoreactivity in their nuclei, suggesting that increase in the C/EBP-β mRNA or protein expression in the whole cortical homogenate (A and B) is most likely related to the influx of inflammatory cells (n = 5; P < 0.001).

Figure 8.

Oxidative stress inhibits nuclear translocation of C/EBP-β in HK-2 cells. (A through D) A reduced anti–C/EBP-β immunoreactivity was seen in the nuclei of cells treated with 100 μM H2O2. (E through J) The reduced C/EBP-β immunoreactivity was normalized with the treatment of NAC or PKAi. PKCi had no ameliorative effect in cells treated with H2O2. (K) Western blot analyses indicated that various treatments had a marginal effect on the expression of total C/EBP-β expression; however, its phosphorylation and subsequent nuclear translocation were inhibited by H2O2, which was normalized by NAC and PKAi. The expressions of GAPDH and TATA-binding protein (TBP) were unaltered.

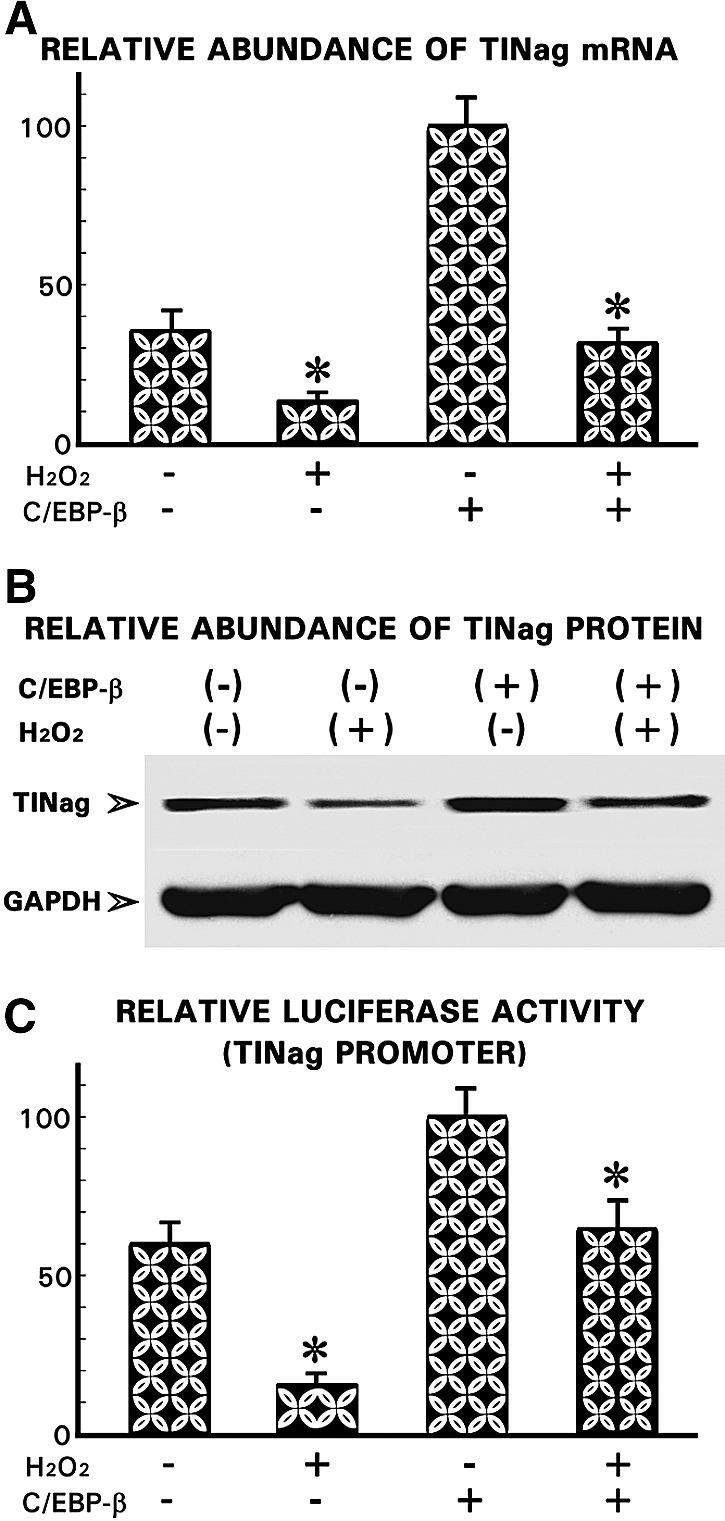

Effect of Overexpression of C/EBP-β on TINag Expression

Because a parallelism is seen in the expression profiles of TINag and C/EBP-β, it led us to investigate whether C/EBP-β overexpression would have a reversal effect on TINag expression. Transfection of pCMV6-XL4-C/EBP-β into HK-2 cells led to an approximately three-fold increase of TINag expression (Figures 9, A and B). Also, the transfected cells treated with H202 had an approximately two-fold higher TINag expression than nontransfected cells, suggesting that the C/EBP-β has a certain degree of protective effect. Similarly, there was an approximately two-fold increase in luciferase activity upon co-transfection of pCMV6-XL4-C/EBP-β and pGL3-DC4-416 into HK-2 cells (Figure 9C). In addition, there was an approximately four-fold increase in the promoter activity in co-transfected cells exposed to H2O2, compared with cells transfected with pGL3-DC4-416 alone (Figure 9C), suggesting a relationship between the C/EBP-β and TINag expression.

Figure 9.

Effect of overexpression of C/EBP-β on TINag expression. (A and B) Transfection of C/EBP-β into HK-2 cells led to a remarkable increase of TINag mRNA and protein expression under basal conditions. Also, the C/EBP-β–transfected cells treated with H2O2 had TINag expression similar to untreated cells under basal conditions. (C) The transfection of C/EBP-β led to a normalization of the TINag promoter activity in cells subjected to oxidant stress with H2O2 (n = 5; P < 0.001).

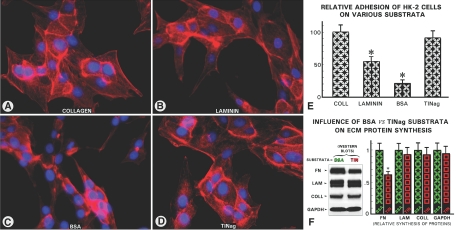

TINag Promotes Adhesion of HK-2 Cells and Maintains Organized Cellular Actin Cytoskeleton

Conceivably, one of the major factors that maintain typical epithelial phenotype and normal cytoskeletal organization of tubular cells is the integrity of ECM along with its integral proteins, such as TINag, modulating its adhesive properties. In view of this, adhesion of HK-2 cells on the TINag substratum was investigated and compared with type IV collagen, laminin, and BSA. The BSA-coated culture dishes revealed poor adherence, and the cells had rounded or spindle-shaped morphology. The F-actin stress fibers were condensed, and the cells exhibited poor cytoskeletal organization (Figure 10, C and E). Type IV collagen–coated dishes exhibited flattened cellular morphology with good adhesion and fine F-actin cytoskeletal organization (Figure 10, A and E). TINag yielded a similar degree of adhesion and F-actin organization. The cells maintained their typical flattened morphology and had well-preserved fine organization of stress fibers as seen with type IV collagen (Figure 10, D and E). Interestingly, the fibronectin synthesis was markedly reduced, whereas type IV collagen and laminin synthesis was marginally affected (Figure 10F). The degree of laminin adhesive effect was approximately 50% of the type IV collagen or TINag and had intermediate morphology characteristics and cytoskeletal organization (Figure 10, B and E), suggesting that TINag and type IV collagen have similar modulatory effects.

Figure 10.

TINag promotes adhesion of HK-2 cells and maintains organized cellular actin cytoskeleton and reduces fibronectin synthesis. (A through D) More than 90% of the cells plated on dishes coated with type IV collagen or TINag had flattened morphology with fine F-actin stress fibers and cytoskeletal organization. With laminin, approximately 50% of the cells retained the same phenotypic characteristics as those seen with type IV collagen and TINag. The culture dishes coated with BSA revealed cells with round- or spindle-shaped morphology. The F-actin stress fibers were condensed, and their fine organization was not readily discernible. (E) Enumeration of the attached versus detached cells after 24 h of plating revealed that TINag and type IV collagen exerted similar adhesive effect, whereas BSA exhibited poor adhesiveness and laminin with intermediate properties. (F) Western blot analysis of extracts from cells grown on TINag-coated dishes revealed a significant decrease in the fibronectin synthesis, whereas the synthesis of type IV collagen and laminin was minimally affected as compared with the cells harvested from dishes coated with BSA (n = 5; P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

UUO is a well-established model of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. It is characterized by increased accumulation of ECM glycoproteins, including type IV collagen, laminin, entactin, and fibronectin.17–19 Likewise, in this study, increased expression of type IV collagen and of fibronectin was observed (Figure 1); however, in contrast to previous reports, the expression of laminin was found to be focally decreased in regions where tubules had undergone dilation and atrophy (Figure 1). Similarly, TINag was found to be decreased after UUO (Figure 2); however, the reduction was disproportionately pronounced compared with laminin. Such differential alterations among ECM proteins may be related to their biochemical and biophysical characteristics (e.g., type IV collagen being relatively resistant to degradation compared with other ECM proteins).13 Another possibility is that TINag protein having cathepsin-like domain could exert a differential “dissolving or depolymerizing effect” on other matrix proteins.13 This is unlikely because TINag itself is reduced, which may be related to the oxidant stress as evidenced by increased nuclear DHE staining (Figure 2), which is also seen in other renal diseases.23 Previous observations showing an increase of oxidative stress modulating extracellular signal–related signaling pathway during UUO would be supportive of our studies.24,25 In any instance, the selective effect on ECM proteins (collagen versus laminin versus TINag) can be readily envisioned because differential susceptibility of various preformed proteins to oxidative damage by oxygen radicals has been well described in ECM-producing tumor.26 Also, in line with this contention are our in vitro studies on HK-2 cells that indicated that the oxidant stress also leads to a decreased expression of de novo synthesized TINag (Figures 3 and 4). This effect seems to be specific because antioxidants such as NAC and DTT largely restored the TINag expression (Figures 3 and 4). Here the distinction needs to be made about the effect of oxygen radicals on preformed versus de novo synthesized proteins, because in the latter case, the issue of various transcriptional versus translational mechanisms modulating TINag pathobiology needs to be addressed.

To investigate such mechanism(s), we performed TINag promoter analysis (Figure 5). The promoter activity was mainly confined to approximately −500 bp flanking the open reading frame, and it was adversely affected by the oxidant treatment. Interestingly, many of the critical motifs (e.g., C/EBP-β) that conceivably modulate TINag transcription are confined within the −500-bp region (Figure 5). C/EBP-β is a transcription factor that regulates expression of several genes by interacting with their regulatory domains of promoters and/or enhancers of target genes, including the ECM proteins.20–22 To establish a relationship between TINag and C/EBP-β, we performed in vitro studies using EMSA/Chip assays. They revealed that there are indeed specific DNA–protein interactions between the TINag and C/EBP-β (Figure 6). The results that these in vitro interactions are perturbed by oxidant stress and then largely restored by antioxidants suggest that TINag and C/EBP-β are relevant to the pathogenesis of UUO. This contention is supported by our in vivo studies.

The C/EBP-β expression was increased in the cortical homogenates on day 3 onward after UUO (Figure 7). A similar increase was also reported in one of the previous studies27; however, in situ expression of C/EBP-β was decreased in the cytoplasmic and more so in the nuclear compartment of renal tubules in our studies (Figure 7). It is conceivable that the increased expression of C/EBP-β observed previously may be due to the influxed inflammatory cells expressing this transcription factor. To address this issue, in vitro experiments in HK-2 cells were carried out. The C/EBP-β was seen localized both in the cytoplasm and nucleus but predominantly in the latter in control cells (Figure 8). The nuclear expression of C/EBP-β was largely lost with H2O2 treatment, whereas cytoplasmic staining persisted, suggesting that the oxidative stress interferes in its translocation into the nucleus. The immunoblot analyses indicating a C/EBP-β reduction in the nuclear fraction and restoration by NAC antioxidant confirmed the observations made in morphologic studies. To reinforce the observations of perturbed C/EBP-β expression and localization, we performed nuclear binding/translocation studies inhibiting its phosphorylation coupled with oxidant stress. It is known that the DNA-binding activity of C/EBP-β and its translocation are regulated by a multitude of factors, especially the phosphorylation of a given amino acid residue by various kinases (e.g., mitogen-activated protein kinase, PKC, PKA).28–31 These studies also indicate that phosphorylation of a particular amino acid by PKA versus PKC differentially modulates the activity of C/EBP-β and thereby exerts distinct biologic effects. A similar scenario applies to our studies in which a decreased phosphorylation and hence nuclear translocation of C/EBP-β induced by oxidative stress were restored by PKA inhibitor, whereas PKC inhibitor had a minimal effect. Taking into account our in vivo and in vitro data (Figures 7 and 8), it is likely that oxidative stress inhibited the transactivation of C/EBP-β by interfering PKA pathway in UUO. Given that C/EBP-β modulates the activity of various genes that are involved in diverse biologic processes,22,32,33 it is conceivable that its biology and that of the TINag are interlinked.

Such a link is conceivable because overexpression of C/EBP-β led to several-fold upregulation of TINag, which was dampened by H2O2 (Figure 9). Interestingly, with dual transfection of TINag-DC4 and C/EBP-β constructs, the promoter activity doubled in parallel with the increase in TINag expression, thus suggesting a functional relationship between these two macromolecules. A final lingering question—whether TINag has any relevance to EMT—needs to be addressed in the context of tubulointerstitial fibrosis.5–8 EMT implies a phenotypic change with rearrangement of F-actin fibers, loss of cell basement membrane adhesion, increased cell migration, and invasion into the interstitium.9 The process is augmented by increased activity of TGF-β and matrix metalloproteinases.7 The latter apparently cause degradation of TBMs with migration of phenotypically altered epithelia (myofibroblasts?) into the interstitium, where TGF-β would induce accelerated fibrosis.5 In support of this notion are previous gene disruption studies with bone morphogenic protein 7, a competitor of TGF-β, in which reversal of the scaring and EMT response was seen with its administration or overexpression in UUO and other models of renal fibrosing injury.34–36 This may mean that TBM integrity is essential to maintain a normal epithelial phenotype and cell–matrix adhesion involving integrins, thereby preventing cellular migration into the interstitium. Thus, with the downregulation of TBM components, there is a likelihood of perturbation in adhesion and phenotypic characteristics of epithelia.7,37 To address this question, we assessed adhesive characteristics of HK-2 cell grown on different substrata. The characteristics of the cells grown on TINag substrata were comparable with that of type IV collagen but had reduced fibronectin synthesis (Figure 10), suggesting that TINag is essential to the biology of renal tubular cells, and its deficiency could contribute to their altered phenotype and an exaggerated EMT response typical of UUO. Moreover, the decreased synthesis of fibronectin in the presence of TINag would be supportive of this notion.

In summary, the TINag seems to be relevant to the pathobiology of UUO, and its transcriptional modulation by C/EBP-β may be another potential mechanism pertinent to the induction of renal fibrosis that would be applicable to various tubulointerstitial diseases.

CONCISE METHODS

Animal Model System

A total of 48 8-wk-old Sprague-Dawley female rats were used. All animal procedures used in this study were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Northwestern University. Under Avertin anesthesia (200 mg/kg intraperitoneally), a midline abdominal incision was made and the left ureter was dissected out. The ureter was ligated at approximately 1 cm below the renal hilum with 3-0 silk suture. The abdominal wound was closed, and rats returned to the cages after an injection of Buprenex (0.01 mg/kg subcutaneously). Control rats underwent abdominal incision and approximation with no ligation of the ureter. Rats were maintained in the animal facility with access to water and rat food ad libitum. They were killed in batches of six at 3, 7, 14, and 21 d after ureteral ligation. Both left and right kidneys were used for various morphologic and biochemical studies. The right kidney from the rats that had undergone left unilateral ligation also served as another control.

Kidney Morphology Studies

For assessment of histologic changes, two to three approximately 1-mm-thick slices of the kidney from its mid transverse section were made. They were either snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen–chilled isopentene and embedded in 22-oxacalcitol (OCT) compound for immunofluorescence studies or immersed in 10% formaldehyde fixative. After fixation, the kidney slices were processed for routine hematoxylin and eosin or silver staining and immunohistochemistry.

For immunofluorescence studies, 4-μM-thick cryostat sections were prepared, air-dried for 4 to 6 h, equilibrated with PBS for 5 to 10 min, and then incubated with the polyclonal anti-TINag antibody at 37°C for 1 h. This antibody was raised against a peptide, whose sequence was derived from the N-terminus of TINag with >80% homology across various mammalian species. The sections were washed twice with PBS and re-incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody conjugated with FITC (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 37°C for another hour. After a drop of buffered glycerol was placing, the sections were coverslip mounted and examined with a Zeiss microscope equipped with UV epi-illumination (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc., Thornwood, NY).

For silver staining, 4-μm-thick paraffin sections were prepared, deparaffinized, hydrated, and then fixed in 0.5% periodic acid. After washing with distilled water, the sections were immersed in silver methenamine solution (2.2% methenamine and 0.22% silver nitrate in 45 mM borate buffer [pH 8.2]) at 70°C for 1 h, after which the sections were stained with 0.2% gold chloride at 22°C for 1 min. After dehydrating and placement of a drop of Permount, the sections were coverslip mounted and examined.

For immunohistochemical studies Avidin-Biotin Complex method (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was used. Four-micrometer-thick sections were deparaffinized and hydrated in graded series of decreasing concentrations of ethanol. The section were treated with 0.3% H2O2 followed by incubation with 5% normal goat serum in PBS. They were then incubated with either rabbit anti–collagen IV (Chemicon) or anti–C/EBP-β (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; and Cell Signaling Technologies Inc., Danvers, MA) at 4°C for 12 h. After washing thrice with PBS, the sections were successively incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG and streptavidin conjugated with horseradish peroxidase, each for 30 min at 22°C. The sections were then treated with SIGMAFAST 3′,3′-diaminobenzidene solution (0.7 mg/ml, urea H2O2 0.67 mg/ml and 60 mM Tris-HCl buffer [pH 7.6]) for 2 to 10 min at 22°C to develop the horseradish peroxidase reaction product, and they were counterstained with hematoxylin. After dehydration, the sections were coverslip mounted and examined.

In Situ Morphologic Detection of Reactive Oxygen Species

Intracellular generation of oxygen species (O2·−) was assessed using DHE (Sigma-Aldrich), which reacts with O2·− to generate ethidium bromide that binds to nuclear DNA and yields red fluorescence. Approximately 4-μM-thick cryostat sections were prepared from freshly harvested kidneys from control and UUO rats. They were air-dried for 2 h and equilibrated with PBS for 10 min. They were then incubated with 1 μM DHE solution in PBS buffer in a light-protected humidified chamber at 37°C for 45 min. They were washed twice with PBS, and after placement of a drop of buffered glycerol, the sections were coverslip mounted and examined with a Zeiss fluorescence microscope.

Biochemical Studies on UUO Kidneys

The kidneys were minced into 1-mm3 pieces, homogenized, and extracted with 0.1 M Tris HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 6 M guanidinium HCl and a mixture of protease inhibitors (0.02% NaN3, 10 mM ɛ-amino-n-caproic acid, 5 mM N-ethymaleimide, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) for 12 h at 4°C with vigorous shaking. The extract was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min, and the supernatant was saved. The supernatant was precipitated with 10 vol of absolute ethanol at −20°C for 12 h. The precipitate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min, and the pellet was washed with 80% ethanol and dissolved in PBS buffer containing 8 M urea with protease inhibitors as indicated previously. After measurement of the protein concentration, the samples were stored at −70°C until further use. The sample containing equal amounts of proteins from control versus UUO kidneys was subjected to SDS-PAGE analyses. Western blots were prepared by transferring the proteins onto nitrocellulose membranes and probed with rabbit anti-TINag antibodies, after which the autoradiograms of the blots were prepared using Enhanced Chemiluminescence system (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) per the manufacturer's instructions. The anti-GAPDH (Santa-Cruz Biotechnology) served as the loading control.38

For assessment of the expression of C/EBP-β, rat kidney cortices were homogenized in a lysis buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% DOC, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitors as indicated previously. Equal amounts (50 μg) of the tissue lysates from control and UUO rat kidneys were used for 10% SDS-PAGE, and proteins were electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. The Western blots were then probed with rabbit anti–C/EBP-β antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and autoradiograms were prepared.

Cell Culture Studies

HK-2 cells were obtained from ATCC (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) and grown in a keratinocyte serum-free medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in the presence of 5 ng/ml recombinant EGF and 0.05 mg/ml bovine pituitary extract. Approximately 1 × 106 cells per well in a six-well culture plate or 1 × 105 cells per well in a Lab-Tek-8 chambers slide (Nalge Nunc, Rochester, NY) were maintained for 24 h at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. The cells were then either directly exposed to H2O2 (0 to 100 μM) for 24 h or after 1 h of treatment with NAC (0 to 10 mM), DTT (0 to 100 μM), PKC inhibitor Calphostin C (0.02 μM), or PKA inhibitor H89 (0.2 μM). The cells were processed for expression and immunofluorescence studies. The cells were fixed in cold methanol at −20°C for 5 min and then immersed in PBS solution containing 1% BSA for 30 min followed by incubation with rabbit polyclonal anti-C/EBP-β antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 37°C for 1 h. The cells were then washed twice with PBS and incubated with anti-rabbit IgG antibody conjugated with FITC at 37°C for 1 h. They were briefly washed with PBS and after placement of a drop of buffered glycerol coverslip mounted and then examined with a fluorescence scope. The cells were stained with DAPI for outlining of the nuclei.

The cells were also processed after treatment of H2O2 for Western blot analysis to assess the expression of TINag or C/EBP-β as described previously. In a separate experiment, the cells were also transfected with either pCMV6-XL4-C/EBP-β (Origene Technologies, Rockville, MD) or empty vector by using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) for assessment of whether C/EBP-β affects the expression of TINag after H2O2 treatment.

Gene Expression Studies

Total RNA was extracted from kidneys and HK-2 cells (experimental versus control), as described previously.14 It was then treated with RNase-free DNase (1 U/μl) in the presence of ribonuclease inhibitor (1 U/μl) and RNase-free glycogen (0.1 μg/μl). The RNA was ethanol-precipitated and suspended in DEPC-treated autoclaved water, and its concentration was adjusted to 0.5 μg/μl. Two micrograms of total RNA was then reverse-transcribed by using Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen; 25 U/μl) and 24-mer oligo(dt) as the primer. The synthesized cDNA was precipitated and analyzed in a sequence detection system (Model 7000; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) by using specific TINag primers and Absolute qPCR SYBR Green Mixes (ABgene, Rochester, NY), as described previously.38 The specific TINag primers for real-time qPCR were as follows: 5′-GCACACTGAGAGGAGCACAA-3′ (sense, rat) and 5′-TAGCCATTCTCTCCCCATGA-3′ (antisense, rat) and 5′-CGAAAGCTTCAGACACATGC-3′ (sense, human) and 5′-TTTCTTTCTGCCCTTGTGCT-3′ (antisense, human). The relative abundance of mRNAs was standardized with 18S mRNA as the invariant control, and the respective sense and antisense primers were as follows: 5′-AAACGGCTACCACATCCAAG-3′ and 5′-CCTCCAATGGATCCTCGTTA-3′.

Isolation of 5′ Flanking Region of TINag Transcript and Generation of Reporter Constructs

An approximately 2-kb DNA fragment flanking the 5′ region was isolated from the mouse Sca-I genomic library (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Mountain View, CA) by using adapter AP-2 primer and a TINag-specific antisense primer (5′-ATCCAGTCCACATTATTGTTTGTTGG-3′, +13 to −13 nt). The DNA fragment was cloned in pCR 2.1 vector (Invitrogen) and used as a template for generation of serial-deletion PCR products by using a common antisense primer 5′-GGGGGGGGTACCTATTGTTTGTTGGTTC-3′ (0 to −16 nt) and the following sense primers: 5′-GGGGGTACCGTAACATTGTATGAGATA-3′ (−256 to −238 nt), pGL3-DC5; 5′-GGGGGTACCCAGGACATTCCTATACCA-3′ (−416 to −398, nt), pGL3-DC4; 5′-GGGGGTACCGAGAAGTCAGGTCAAACT-3′ (−696 to −678 nt), pGL3-DC3; 5′-GGGGGTACCCCACAGGCCACAGAAACAGT-3′ (−1038 to −1018 nt), pGL3-DC2; and ′-GGGGGGGGTACCAGAGTTATGGCCGTGTAAGG-3′ (−1510 to −1490 nt), pGL3-DC1.

A KpnI site, GGTACC (italicized), was included in the primers. These five PCR products (256, 416, 696, 1038, and 1510 bp) were cloned into pCR2.1, then subcloned into pGL3-basic vector (Promega, Madison, WI) for promoter analyses. These deletion constructs were designated as DC1 through DC5, as depicted in Figure 5. The identity of PCR products was confirmed by nucleotide sequencing. Transcription factor–binding motifs and promoter predication were delineated by using the following web site: http://motif.genome.ad.jp. Because the two critical C/EBP-β–binding sites were found to be almost similar in location in the TINag promoter −650 bp upstream of the initiation codon in mouse, rat, and human species and included TATA box and GATA-binding factor 1 motifs, the transfection studies were carried out mainly with deletion constructs pGL3-DC4 and pGL3-DC-5; however, all of the constructs (pGL3-DC1 through pGL3-DC5) were used initially to assess the basal promoter activity after H2O2 exposure.

Transfection of Cells and Luciferase Assays

HK-2 cells (ATCC) (1 × 106 cells) were seeded in a six-well culture plate in DMEM and maintained to achieve approximately 80% confluence. Transfection was carried out by using 10 μl of Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) and 3 μg of reporter pGL3-DC1 through pGL3-DC5 plasmid constructs. Co-transfection of 1 μg of pSV-β-galactosidase was used as optimized equalization control for transfection efficiency. Assays for both luciferase and β-galactosidase activity were performed by using Luciferase (Promega) and Luminescent detection (Clontech) kits, respectively. The activity of promoter-relative light units was defined as luciferase activity/β-galactosidase activity. For assessment of the effect of oxidative stress on the promoter activity of TINag, the medium was replaced with opti-MEM (Invitrogen) containing various concentrations of H2O2 24 h before determination.

Preparation of Cytoplasmic and Nuclear Extracts

For preparation of nuclear extract, HK-2 cells were harvested from 100-mm Petri dishes by scraping with a rubber policeman followed by washing with ice-cold PBS three times and pelleted at 500 × g at 4°C. The pelleted cells (1E + 06 cells) were resuspended in 100 μl of Sucrose buffer (0.32 M Sucrose, 10 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.0], 3 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgOAc, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM DTT, and 0.5 mM PMSF). The nuclei were spun down for 5 min at 1500 × g at 4°C, and cytoplasmic fractions in the supernatants were collected for Western blot analysis. The nuclear pellet was washed with 1 ml of Sucrose Buffer (without NP-40) and mixed gently by a pipette with a wide-bore tip. They were recentrifuged at 1500 × g at 4°C for 5 min and supernatant aspirated. The pelleted nuclei (0.5E + 06 nuclei) were then resuspended in 50 μl of low-salt buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 25% glycerol [vol/vol], 0.5 mM DTT, and 0.5 mM PMSF) by finger tapping the Eppendorf tube. To this, an equal volume of high-salt buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9]; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 800 mM KCl; 0.2 mM EDTA; 25% glycerol [vol/vol]; 1% NP-40; 0.5 mM DTT; 0.5 mM PMSF; and 4.0 μg/ml leupeptin, aprotinin, and pepstatin) was added very slowly while mixing with a wide-bore pipette. The samples were incubated for 30 to 45 min at 4°C while rotating on a orbital shaker. The nuclear extracts and the supernatants were separated by centrifuging at 14,000 × g for 15 min. The concentration of nuclear protein was measured, and samples were stored at −70°C to be used later for EMSA studies. The GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and TATA-binding protein (Abcam)38,39 antibodies were used as cytosolic and nuclear loading controls, respectively.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

EMSA was performed as described previously.40 Briefly, single-stranded oligos, sense, and complimentary oligos were custom synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. The 30-mer sense oligo sequence of murine “putative” C/EBP-β–binding motifs were as follows: GTTTTCTTAGATTTAGCAACCTAGATGTTC (−384 to −371, C/EBP-β-M1) and CTTGTATTATCTTGTGCAAACACTGAAAGT (−184 to −171, C/EBP-β-M2). The sense oligo sequences of human putative C/EBP-β–binding motif were as follows: TAGGGTTGGAGTTATGAAATAGTCTGGGAA (−1097 to −1084, C/EBP-β-H1) and CAGGGAATTTCTTGCTGAATTAGGTTCCAC (−635 to −622, C/EBP-β-H2). The sense and complimentary oligomers (50 pmol) in a volume of 50 μl were annealed in 1× annealing buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA) by boiling for 10 min followed by slow cooling to 22°C for 3 h. The double-stranded probe (10 pmol) was end-labeled by γP32-ATP using T4-poly nucleotide kinase (Promega). The unlabeled double-stranded oligonucleotides were used for competition assays as well as served as controls. For EMSA, binding reaction was carried out for 30 min at 22°C in 20 μl of reaction mixture containing 1× binding buffer (50 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.0], 750 mM KCl, 2.5 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton-X 100, 62.5% glycerol [vol/vol], 1 mM DTT), 1 to 3 μg/μl poly-(dI-dC), 1 pmol/μl labeled DNA probe, and 10 μg of nuclear proteins. The last were prepared as described already from HK-2 subjected to various treatments (H2O2 [0 to 100 μM], glucose oxidase [0 to 5 mU/ml], and NAC [0 to 10 mM]) for 24 h. For specificity competition EMSA, 50-fold excess of unlabeled oligos were used. For supershift EMSA, anti–C/EBP-β antibody was used at a concentration of 1 μg/20 μl in the reaction mixture containing oligos and the nuclear extract. The samples were subjected to 7.5% nondenaturing PAGE, and the gels were dried and autoradiograms were prepared.

ChIP Assay

Approximately 1 × 106 HK-2 serum-starved cells grown to 80% confluence and individually treated with H2O2, glucose oxidase, or NAC were used for binding of C/EBP-β transcription factor. The cross-linking of nuclear protein and DNA was achieved by directly immersing the cells in culture dishes in 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min at 37°C. The ChIP assay was carried out by following the protocol of Hatzis and Talianidis41 with certain modifications. Briefly, cross-linking of DNA and protein was carried out by adding 1% formaldehyde directly to the cell medium and incubating for 30 min. The cross-linking reaction was terminated by adding 0.125 M glycine for 5 min. The cells maintained in 60-mm Petri dishes were then washed with ice-cold PBS followed by scraping with a rubber policeman and then pelleted by centrifuging at 500 × g for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in 10 vol of swelling buffer (25 mM HEPES [pH 7.8], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10m M KCL, 0.1% NP-40, 1 mM DTT, and 0.5 mM PMSF) and incubated on ice for 10 min. The cellular nuclei were pelleted by centrifuging at 1000 × g for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in 500 μl of sonication buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 140 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 0.5 mM PMSF) and incubated on ice for 10 min and sonicated to yield DNA fragments of 200 to 1000 bp. The sonicated material was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min to remove the insoluble debris. BSA (1 mg/ml) was added to the supernatant containing soluble chromatin. The soluble chromatin was precleared by incubating with Protein-A Sepharose/ssDNA for 2 h at 4°C. Samples were centrifuged and 50 μl of aliquot was kept as input DNA and the rest were processed for immunoprecipitation with anti–C/EBP-β antibody followed by incubation with Protein-A Sepharose beads. The samples with no antibody were used as a negative control. The beads were centrifuged and washed twice first with 1 ml of low-salt sonication buffer and then with 1 ml of high-salt wash buffer (sonication wash buffer A with 500 mM NaCl). They were rewashed twice with 1 ml of wash buffer B (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 250 mM LiCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.5 mM PMSF) and twice with 1 ml of Tris-EDTA buffer. The samples were then eluted by addition of 400 μl of elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, and 50 mM NaHCO3) and then incubated at 65°C for 10 min. After addition of 20 μl of 4 M NaCl, the samples were further incubated at 65°C for 6 h for de–cross-linking. Similarly, samples of input DNA were de–cross-linked. One microliter of DNAse-free RNAse A (10 mg/ml) was added and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. This was followed by addition of 2 μl of Proteinase K (10 mg/ml) and 4 μl of 0.5 M EDTA, and samples were incubated at 42°C for 2 h. After phenol/chloroform extraction and addition of 1 μl of glycogen (20 mg/ml), the DNA was precipitated with 40 μl of 3 M sodium acetate and 1 ml of ethanol. The precipitates of ChIP and INPUT samples were resuspended in 100 μl of 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and used for real-time qPCR analyses. The sense and antisense primer pairs for TINag were TGCTAAGCAGGGACTCAGG (−684 to −665) and AAATCATGCCCAGTCACACA (−551 to −532). They were used for PCR analyses with expected product size of 152 bp, which would encompass the promoter region containing C/EBP-β motifs.

Isolation of TINag-His Fusion Protein

Using TINag-pBlueScript (KS+) plasmid as template available in our laboratory,14 a PCR product encompassing full-length TINag was amplified by using sense (5′-GGCAGGGGATCCTGGACTGAATATAAGATC-3′) and antisense (5′-GGCAGGCTCGAGTGGATCATCTGAACTTGT-3′) primers. The latter included 5′-flanking GC clamps and internal respective BamH I and XhoI enzyme restriction sites (italicized). After restriction enzyme digestion, the PCR product was gel purified and ligated into BamH I and XhoI digested pET-21a vector (Novagen, Madison, WI) carrying a C-terminal His-Tag. The plasmid constructs were sequenced to ensure proper in-frame ligation, polymerase fidelity, and their 5′ and 3′ end orientation. After transformation into BL21 (DE3, pLysS; Novagen) bacterial host, appropriate clones carrying the plasmid and inserts were identified. They were used for generation of recombinant TINag by allowing the culture to achieve an A600 of 0.6 and then inducing it with 1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside for 4 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000 × g. The fusion protein was extracted and purified by nickel-charged column affinity chromatography under denaturing conditions as per the manufacturer's instructions (Novagen). Various eluted fractions were collected, and the ones with high content of proteins were pooled and successively dialyzed against 0.1 M PBS containing decreasing concentrations of 6 M 0.01 M urea and protease inhibitors and then against 0.01 acetic acid. Identity and purity of the isolated TINag were assessed by SDS-PAGE and peptide sequence analysis.

Cell Adhesion Assays and Actin Cytoskeleton Organization

Polystyrene 60-mm sterile Petri dishes were coated with filter-sterilized recombinant TINag (10 μg/ml) or type IV collagen (Sigma-Aldrich) or laminin or BSA. The Petri dishes containing approximately 2 ml of each of the proteins were left in culture hood under ultraviolet illumination at 22°C for 12 h. Thereafter, the excess solution was suctioned off, and Petri dishes were filled with another approximately 2 ml of heat-denatured 2% BSA for 60 min to block the uncoated surface. The dishes were then rinsed thrice with PBS followed by once with culture medium, 5 min each. After suctioning off the medium, the dishes were allowed to dry in the culture hood and used for adhesion assays and evaluation of cytoskeletal organization.

For adhesion assays, HK-2 cells were grown in 100-mm Petri dishes to 80% confluence. They were labeled with 100 μCi of [35Ss methionine/5 ml in keratinocyte serum-free medium for 12 h. The medium was removed and cells were rinsed twice with PBS and then harvested by treating with 0.05% trypsin/0.53 mM EDTA solution. The cells were collected by centrifuging at 400 × g for 1 min. They were washed with serum-free medium and recentrifuged and suspended in a cell adhesion binding buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 100 μM MgCl2, 100 μM MnCl2, 100 μM CaCl2, and 1 mg/ml BSA; http://www.glycotech.com/protocols/Proto8.html).42

After assessment of the viability (>95%) with Trypan blue exclusion method, approximately 2.5 × 105 labeled cells/ml medium were seeded onto 60-mm coated dishes as described already and allowed to adhere at 37°C for 3 h. Nonadherent cells were removed by gentle washing with the medium. Adherent cells were solubilized with 1 ml of 0.5 M NaOH + 1% SDS and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min. An aliquot of the supernatant was saved to determine the incorporated radioactivity in the adherent cells. The experiments were performed five times, and the results are expressed as average radioactivity per dish.

For assessment of the influence of various ECM proteins (recombinant TINag, type IV collagen, and laminin from EHS) on the actin cytoskeleton organization, approximately 2.5 × 105 HK-2 unlabeled cells were seeded onto 60-mm coated Petri dishes in serum-free medium as described already. They were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a humidified incubator. They were then fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde at 22°C for 15 min. After a brief PBS wash, the cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 4 min. The cells were washed twice with PBS and then immersed in a PBS solution containing 3% BSA at 22°C for 30 min. They were then stained with 100 nM of Phalloidin-Alexa568 in PBS containing 1% of BSA (Invitrogen) at 22°C for 30 min, counterstained with 300 nM DAPI at 22°C for 1 min and briefly washed with PBS. After placement of a drop of Antifade solution (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), the cells were coverslip mounted and examined with a fluorescent scope.

For assessment of the effect of TINag substratum on the synthesis of various ECM proteins HK-2 cells (1 × 107) were seeded onto TINag- or BSA-coated 60-mm Petri dishes in a keratinocyte serum-free medium. They were allowed to achieve approximately 80% confluence for 48 h in a humidified incubator at 37°C. After a brief PBS wash, the cells were scrapped from the dishes and processed for SDS-PAGE and Western blot analyses, as described already. The autoradiograms were scanned, and average band density from five experiments was determined. The synthesis of various ECM proteins was expressed relative to the BSA control with the band density designated as 1.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK28492 and DK60635.

We thank Dr. Elisabeth I. Wallner for carefully editing the manuscript.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

P.X. and L.S. contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Norman JT, Fine LG: Progressive renal disease: Fibroblasts, extracellular matrix, and integrins. Exp Nephrol 7: 167–177, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarawal A, Nath KA: Effect of proteinuria on renal interstitium: Effects of nitrogen metabolism. Am J Nephrol 13: 376–384, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbate M, Zoja C, Remuzzi G: How does proteinuria cause progressive renal damage? J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2974–2984, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nath KA: Tubulointerstitial changes as a major determinant in the progression of renal damage. Am J Kidney Dis 20: 1–17, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bottinger EP: TGF-β in renal injury and disease. Semin Nephrol 27: 309–320, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neilson EG: Mechanisms of disease: Fibroblasts—A new look at an old problem. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2: 101–108, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalluri R, Neilson EG: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Invest 112: 1776–1784, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zavadil J, Böttinger EP: TGF-β and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions. Oncogene 24: 5764–5774, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeisberg M, Maeshima Y, Mosterman B, Kalluri R: Renal fibrosis: Extracellular matrix microenvironment regulates migratory behavior of activated tubular epithelial cells. Am J Pathol 160: 2001–2008, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrahamson DR, Leardkamolkarn V: Development of kidney tubular basement membranes. Kidney Int 39: 382–393, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergstein J, Litman N: Interstitial nephritis with anti-tubular-basement-membrane antibody. N Engl J Med 292: 875–878, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fliger FD, Wieslander J, Brentens JR, Andres GA, Butkowski RJ: Identification of a target antigen in human anti-tubular basement membrane nephritis. Kidney Int 31: 800–807, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butkowski RJ, Langevald JP, Wieslander J, Brentjens JR, Andres GA: Characterization of a tubular basement membrane component reactive with autoantibodies associated with tubulointerstitial nephritis. J Biol Chem 265: 21091–21098, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanwar YS, Kumar A, Yang Q, Tian Y, Wada J, Kashihara N, Wallner EI: Tubulointerstitial nephritis antigen: an extracellular matrix protein that selectively regulates tubulogenesis vs glomerulogenesis during mammalian renal development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96: 11323–13328, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalfa TA, Thull JD, Butkowski RJ, Charonis AS: Tubulointerstitial nephritis antigen interacts with laminin and type IV collagen and promotes cell adhesion. J Biol Chem 269: 1654–1659, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Krishnamurti U, Wayner EA, Michael AF, Charonis AS: Receptors in proximal tubular epithelial cells for tubulointerstitial nephritis antigen. Kidney Int 49: 153–157, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klahr S, Morrissey J: Obstructive nephropathy and renal fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F861–F875, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bascands JL, Schanstra JP: Obstructive nephropathy: Insights from genetically engineered animals. Kidney Int 68: 925–927, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright EJ, McCaffrey TA, Robertson AP, Vaughan ED Jr, Felsen D: Chronic unilateral obstruction is associated with interstitial fibrosis and tubular expression of transforming growth factor-β. Lab Invest 74: 528–537, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houglum K, Buck M, Adir V, Chojkier M: LAP (NF-IL6) transactivates the collagen alpha 1(I) gene from a 5′ regulatory region. J Clin Invest 94: 808–814, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirfel J, Kelter M, Cancela LM, Price PA, Schule R: Identification of a novel negative retinoic acid responsive element in the promoter of the human matrix Gla protein gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94: 2227–2232, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramji DP, Foka P: CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins: Structure, function and regulation. Biochem J 365: 561–575, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swaminathan S, Shah SV: Novel approaches targeted toward oxidative stress for the treatment of chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 17: 143–148, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawada N, Moriyama T, Ando A, Fukunaga M, Miyata T, Kurokawa K, Imai E, Hori M: Increased oxidative stress in mouse kidneys with unilateral ureteral obstruction. Kidney Int 56: 1004–1013, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pat B, Yang T, Kong C, Watters D, Johnson DW, Gobe G: Activation of ERK in renal fibrosis after unilateral ureteral obstruction: modulation by antioxidants. Kidney Int 67: 931–943, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riedle B, Kerjaschki D: Reactive oxygen species cause direct damage of Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm matrix. Am J Pathol 151: 215–231, 1997 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silverstein DM, Travis BR, Thornhill BA, Schurr JS, Kolls JK, Leung JC, Chevalier RL: Altered expression of immune modulator and structural genes in neonatal unilateral ureteral obstruction. Kidney Int 64: 25–35, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakajima T, Kinoshita S, Sasagawa T, Sasaki K, Naruto M, Kishimoto T, Akira S: Phosphorylation at threonine-235 by a ras-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade is essential for transcription factor NF-IL6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90: 2207–2211, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trautwein C, Caelles C, vander Geer P, Hunter T, Karin M, Chojkier M: Transactivation by NF-IL6/LAP is enhanced by phosphorylation of its activation domain. Nature (London) 364: 544–547, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trautwein C, van der Geer P, Karin M, Hunter T, Chojkier M: Protein kinase A and C site-specific phosphorylations of LAP (NF-IL6) modulates its binding affinity to DNA recognition elements. J Clin Invest 93: 2554–2561, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chinery R, Brockman JA, Dransfield DT, Coffey RJ: Antioxidant-induced nuclear translocation of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta: A critical role for protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of Ser299. J Biol Chem 272: 30356–30361, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cortés-Canteli M, Pignatelli M, Santos A, Perez-Castillo A: CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta plays a regulatory role in differentiation and apoptosis of neuroblastoma cells. J Biol Chem 277: 5460–5467, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu S, Yoon K, Sterneck E, Johnson PF, Smart RC: CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-beta is a mediator of keratinocyte survival and skin tumorigenesis involving oncogenic Ras signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 207–212, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato M, Muragaki Y, Saika S, Roberts AB, Ooshima A: Targeted disruption of TGF-beta1/Smad3 signaling protects against renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction. J Clin Invest 112: 1486–1494, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeisberg M, Bottiglio C, Kumar N, Maeshima Y, Strutz F, Muller GA, Kalluri R: BMP-7 inhibits progression of chronic renal fibrosis associated with two genetic mouse models. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F1060–F1067, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang S, de Caestecker M, Kopp J, Mitu G, Lapage J, Hirschberg R: Renal BMP-7 protects against diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2504–2512, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White LR, Blanchette JB, Ren L, Awn A, Trpkov K, Muruve DA: The characterization of α5-integrin expression on tubular epithelium during renal injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F567–F576, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun L, Xie P, Wada J, Kashihara N, Liu F-U, Zhao Y, Kumar D, Chugh SS, Danesh FR, Kanwar YS: Rap1bGTPase ameliorates glucose-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 2293–2301, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meltser I, Tahera Y, Simpson E, Hultcrantz M, Charitidi K, Gustafsson JA, Canlon B: Estrogen receptor-β protects against acoustic trauma in mice. J Clin Invest 118: 1563–1570, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nayak B, Xie P, Akagi S, Yang Q, Sun L, Wada J, Thakur A, Danesh FR, Chugh SS, Kanwar YS: Modulation of renal-specific oxido-reductase/myo-inositol oxygenase by high-glucose ambience. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 17952–17957, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hatzis P, Talianidis I: Regulatory mechanisms controlling human hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α gene expression. Mol Cell Biol 21: 7320–7330, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wayner EA, Orlando RA, Cheresh DA: Integrin αVβ3 and αVβ5 contribute to cell attachment to vitronectin but differentially distribute on the cell surface. J Cell Biol 113: 919–929, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]