Abstract

Wnts compose a family of signaling proteins that play an essential role in kidney development, but their expression in adult kidney is thought to be silenced. Here, we analyzed the expression and regulation of Wnts and their receptors and antagonists in normal and fibrotic kidneys after obstructive injury. In the normal mouse kidney, the vast majority of 19 different Wnts and 10 frizzled receptor genes was expressed at various levels. After unilateral ureteral obstruction, all members of the Wnt family except Wnt5b, Wnt8b, and Wnt9b were upregulated in the fibrotic kidney with distinct dynamics. In addition, the expression of most Fzd receptors and Wnt antagonists was also induced. Obstructive injury led to a dramatic accumulation of β-catenin in the cytoplasm and nuclei of renal tubular epithelial cells, indicating activation of the canonical pathway of Wnt signaling. Numerous Wnt/β-catenin target genes (c-Myc, Twist, lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1, and fibronectin) were induced, and their expression was closely correlated with renal β-catenin abundance. Delivery of the Wnt antagonist Dickkopf-1 gene significantly reduced renal β-catenin accumulation and inhibited the expression of Wnt/β-catenin target genes. Furthermore, gene therapy with Dickkopf-1 inhibited myofibroblast activation; suppressed expression of fibroblast-specific protein 1, type I collagen, and fibronectin; and reduced total collagen content in the model of obstructive nephropathy. In summary, these results establish a role for Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis and identify this pathway as a potential therapeutic target.

The Wnt family of secreted signaling proteins plays an essential role in organogenesis, tissue homeostasis, and tumor formation.1–4 Aberrant regulation of Wnt signaling has been implicated in the pathogenesis of many human diseases in diverse types of tissues.3,4 Wnt proteins transmit their signal across the plasma membrane through interacting with serpentine receptors, the Frizzled (Fzd) family of proteins, and co-receptors, members of the LDL receptor–related protein (LRP5/6). Upon binding to their receptors, Wnt proteins induce a series of downstream signaling events involving Disheveled (Dvl), axin, adenomatosis polyposis coli, and glycogen synthase kinase 3β, resulting in dephosphorylation of β-catenin. This leads to the stabilization of β-catenin, rendering it to translocate into the nuclei, where it binds to T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor (LEF) to stimulate the transcription of Wnt target genes.5–7 In addition to this canonical pathway, Wnt proteins may exert their activities through numerous β-catenin–independent, noncanonical intracellular signaling routes.8

Both Wnts and Fzd receptors are encoded by multiple, distinct genes, creating a complex network of signaling system with enormous degree of diversity as well as redundancy. At least 19 distinct Wnt proteins and 10 different Fzd receptors have been identified in mouse9,10 (see The Wnt Homepage http://www.stanford.edu/∼rnusse/wntwindow.html).Not surprising, Wnt signaling is tightly regulated in a multitude of ways. There are several secreted antagonists of Wnt signaling, including soluble Frizzled-related protein (sFRP), Wnt inhibitory factor, and a family of Dickkopf (DKK) proteins.1,5 Of them, DKK proteins are unique in that they specifically inhibit the canonical Wnt signal pathway by binding to the LRP5/6 component of the receptor complex.11,12

Wnt/β-catenin signaling has been shown to play a role in kidney development and diseases. Wnt4 and Wnt9b are highly expressed in the early stage during kidney development and are functionally important for nephron formation.13,14 In adult kidney, however, Wnt signaling seems to be silenced.14–16 Dysregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling occurs in certain types of kidney diseases, including obstructive nephropathy.17,18 These observations clearly suggest a potential role of Wnt signaling in mammalian nephrogenesis, tissue homeostasis, and pathogenesis of kidney diseases; however, the expression of 19 Wnts and 10 Fzd receptors in adult kidney remains to be determined. Furthermore, their regulation and function in the evolution of chronic kidney diseases are poorly understood.

In this study, we performed a comprehensive analysis of the expression and regulation of Wnts and their receptors and antagonists in normal and fibrotic kidneys after obstructive injury. Our data indicate that the majority of Wnts and Fzd receptors are upregulated in diseased kidney, which leads to a dramatic accumulation of β-catenin, resulting in induction of the Wnt/β-catenin target genes. Furthermore, we show that delivery of Wnt antagonist DKK1 gene reduces β-catenin accumulation and attenuates renal interstitial fibrosis in a mouse model of obstructive nephropathy. These studies establish a critical role of hyperactive Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis and present a novel target for therapeutic intervention of fibrotic kidney diseases.

RESULTS

Expression of Wnt Genes in Normal and Fibrotic Kidneys

We first performed a systematic analysis of the mRNA expression of all Wnt genes in normal mouse kidney by the reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT-PCR) approach. As shown in Figure 1A, the vast majority of 19 Wnts, except Wnt3a, Wnt8a, and Wnt10b, were expressed at different levels in mouse adult kidney. In the absence of RT, no PCR product was detected, suggesting the specificity of Wnt expression. We next investigated the regulation of Wnt expression during the course of renal interstitial fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO). As shown in Figure 1B, the steady-state mRNA levels of most Wnt genes were increased at different time points after UUO. The actual values of renal mRNA levels of various Wnts are presented in the Supplemental Table 1. On the basis of the characteristic features of Wnt regulation, four dynamic patterns of Wnt expression during the process of renal fibrosis could be classified. As presented in Figure 1C, there were only three Wnts, including Wnt5b, Wnt8b, and Wnt9b, whose expression was unaltered throughout the course of renal fibrogenesis after UUO. Wnt1, Wnt7a, and Wnt7b displayed a similar expression pattern, with a peak induction at 7 d after obstructive injury, followed by declining in mRNA levels. The expression of five other Wnts, including Wnt2b, Wnt3, Wnt5a, Wnt9a, and Wnt16, was initially increased up to 7 d and sustained thereafter. The remaining eight members of Wnt family shared a comparable induction dynamic, with a continuous increase in mRNA expression during the entire experimental period. Of interest, there was no single Wnt whose expression was suppressed in the fibrotic kidney after UUO.

Figure 1.

Expression of Wnt genes in normal and fibrotic mouse kidneys. (A) Representative RT-PCR results show the expression of different Wnt genes in normal mouse kidney. In the absence of RT, no PCR product was detected, suggesting the specificity. (B) Representative RT-PCR results demonstrate the steady-state levels of renal Wnt mRNA at different time points after UUO as indicated. Numbers (1, 2, and 3) indicate each individual animal in a given group. (C) Graphic presentation shows the distinct, dynamic pattern of Wnt regulation in the fibrotic kidney. Different Wnts with similar dynamic pattern after injury were grouped. The actual values of relative mRNA levels (fold induction over sham controls) are presented in Supplemental Table 1.

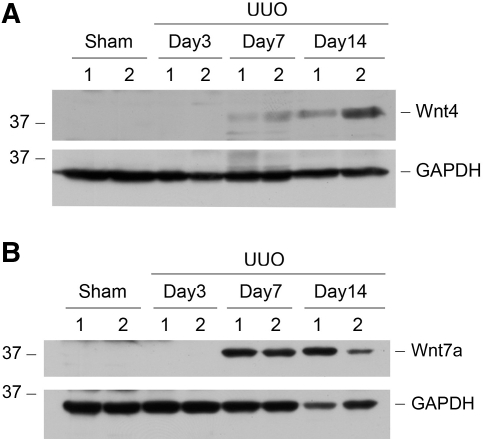

Wnt protein was also upregulated in the fibrotic kidney. Figure 2 shows the protein levels of Wnt4 and Wnt7a at different time points after UUO. Similar to their mRNA, substantial increase in renal Wnt4 and Wnt7a protein abundance was evident in a time-dependent manner. Of note, Wnt4 and Wnt7a protein also exhibited distinct patterns of induction dynamics (Figure 2). To address whether Wnt induction is a general phenomenon in renal fibrogenesis, we also examined Wnt expression in a mouse model of adriamycin nephropathy. As presented in Supplemental Figure 1, the expression of many Wnts was also upregulated in diseased kidney at 5 wk after injection of adriamycin, a time point when significant glomerular and interstitial fibrosis is evident.19

Figure 2.

Induction of renal Wnt4 and Wnt7a protein expression after obstructive injury. Whole-kidney homogenates were prepared at different time points after UUO as indicated and immunoblotted with antibodies against Wnt4, Wnt7a, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), respectively. Numbers (1 and 2) indicate each individual animal in a given group.

Regulation of Wnt Receptors and Antagonists

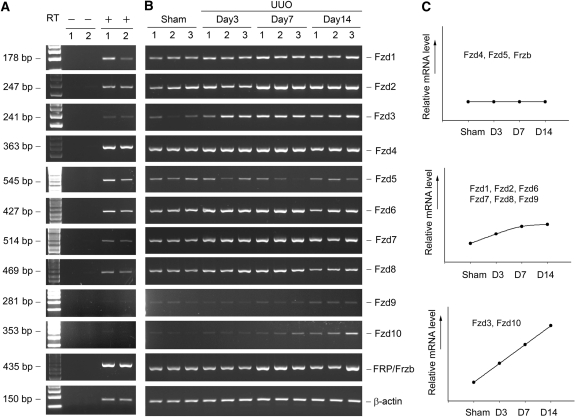

We next examined the expression of the Fzd receptor genes in mouse kidney. As shown in Figure 3A, except for Fzd10, the mRNA of all Fzd genes (Fzd1 through 9) could be detectable in mouse adult kidney by the RT-PCR approach, albeit different in abundance. Figure 3B shows the representative RT-PCR results of renal Fzd mRNA levels at different time points after UUO. The actual values of relative Fzd mRNA levels are presented in Supplemental Table 2. As shown in Figure 3C, the expression of Fzd4 and Fzd5 was not changed throughout the period of the experiments. Fzd1, Fzd2, Fzd6, Fzd7, Fzd8, and Fzd9, however, were moderately induced, whereas the expression of Fzd3 and Fzd10 genes was significantly upregulated (Figure 3C). Once again, none of the Fzd genes was repressed in fibrotic kidney after obstructive injury. sFRP (or Frzb), a Wnt antagonist, was not significantly changed throughout the experiments (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Regulation of the Fzd receptor genes in normal and fibrotic kidneys. (A) Representative RT-PCR results show the expression of different Fzd receptor genes in mouse kidney. In the absence of RT, no PCR product was detected, suggesting the specificity. (B) Representative RT-PCR results demonstrate the steady-state levels of renal Fzd mRNA at different time points after UUO as indicated. Numbers (1, 2, and 3) indicate each individual animal. (C) Graphic presentation shows the dynamic pattern of Fzd regulation in the fibrotic kidney. Different Fzd receptors with similar expression pattern after injury were grouped. The actual values of relative mRNA levels (fold induction over sham controls) are presented in Supplemental Table 2.

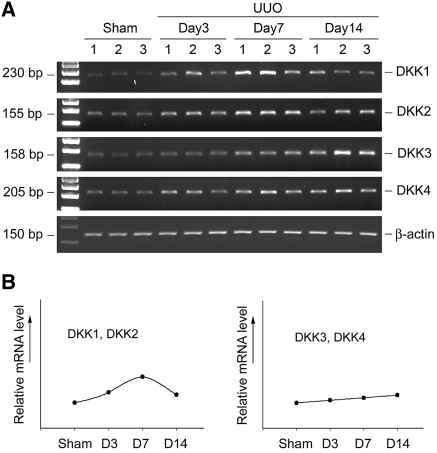

We further investigated the expression of a family of Wnt antagonist DKK genes in normal and fibrotic kidneys. Figure 4A shows the representative RT-PCR results of the steady-state levels of various DKK mRNA at different time points after UUO. All four members of the DKK family proteins were expressed in normal mouse kidney, and their mRNA levels were moderately increased after ureteral obstruction (Figure 4A). Analysis of the expression dynamics revealed that DKK1 and DKK2 expression peaked at 7 d after UUO and declined thereafter, whereas the abundances of DKK3 and DKK4 mRNA were induced slightly and gradually throughout the experiments (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Expression of Wnt antagonists in obstructive nephropathy. (A) Representative RT-PCR results demonstrate the steady-state levels of various Dickkopf (DKK1 through 4) mRNA at different time points after UUO as indicated. Numbers (1, 2, and 3) indicate each individual animal. (B) Graphic presentation shows the dynamic pattern of DKK regulation in the fibrotic kidney. DKKs with similar expression pattern after injury were grouped.

Activation of Wnt/β-Catenin Canonical Pathway in Obstructive Nephropathy

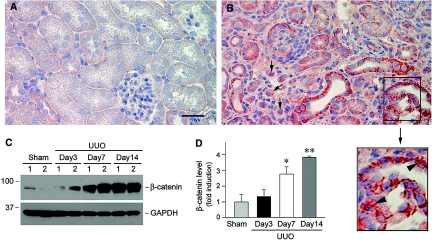

To examine the functional consequence of Wnt regulation in renal fibrosis, we next sought to investigate the activation of β-catenin, the principal mediator of the canonical pathway of Wnt signaling. Figure 5, A and B, demonstrated the expression and localization of β-catenin protein in normal and obstructed kidney at 7 d after UUO. Compared with the sham controls, β-catenin protein was clearly upregulated predominantly in renal tubules of the obstructed kidney, as shown by immunohistochemical staining. Besides at the sites of cell–cell adhesions, β-catenin was localized in the cytoplasm and the nuclei of tubular epithelial cells (Figure 5B, boxed area). Of note, β-catenin–positive cells were also observed in the interstitium (Figure 5B, arrows). Judging from the shape and size of the nuclei, it is likely that these interstitial β-catenin–positive cells were the estranged tubular cells. Western blot analysis also revealed a dramatic increase in renal β-catenin abundance after obstructive injury (Figure 5C). Relative β-catenin levels were increased by approximately four-fold over the sham controls at 14 d after UUO (Figure 5D), suggesting that induction of Wnt expression would result in an accumulation of β-catenin in fibrotic kidney.

Figure 5.

Activation of the Wnt/β-catenin canonical pathway in obstructive nephropathy. (A and B) Representative micrographs demonstrate the accumulation and localization of β-catenin in fibrotic kidney. Kidneys from sham (A) and UUO for 7 d (B) were stained immunohistochemically for β-catenin protein. Bar = 40 μm. Arrows indicate β-catenin–positive cells in the interstitium. Arrowheads in the enlarged box area indicate positive nuclear staining. (C and D) Western blot analysis shows a dramatic increase in renal β-catenin abundance after obstructive injury. Representative Western blot (C) and quantitative data (D) are presented. Relative β-catenin levels (fold induction over sham controls) were reported after normalizing with GAPDH. Data are means ± SEM of five animals per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus sham controls.

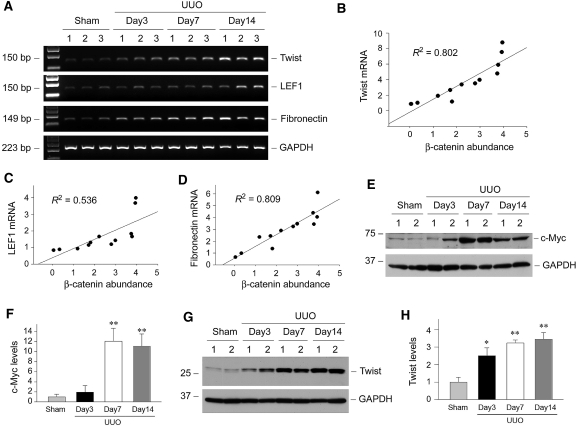

We further studied the expression of several putative target genes of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in obstructive nephropathy. As shown in Figure 6A, numerous widely known Wnt/β-catenin target genes, including Twist, LEF1, and fibronectin, were upregulated in the obstructed kidney in a time-dependent manner. The steady-state mRNA levels of these genes were closely correlated with the abundance of renal β-catenin throughout the experiments (Figure 6, B through D). In addition, c-Myc and Twist proteins were dramatically increased in the kidney after obstructive injury (Figure 6, E through H).

Figure 6.

Expression of Wnt/β-catenin target genes in obstructive nephropathy. (A) RT-PCR analysis shows the induction of putative Wnt/β-catenin target genes in the obstructed kidney at different time points after UUO. (B through D) Linear regression shows a close correlation between renal Twist (B), LEF1 (C), and fibronectin (D) mRNA levels and β-catenin abundance (arbitrary units). The correlation coefficients (R2) are shown. (E through H) Western blot analyses demonstrate a dramatic increase in renal c-Myc and Twist protein abundance after obstructive injury. Representative Western blot (E and G) and quantitative data (F and H) are presented. Relative c-Myc and Twist protein levels (fold induction over sham controls) are reported after normalization with GAPDH. Data are means ± SEM of five animals per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus sham controls.

DKK1 Gene Therapy Blocks Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling

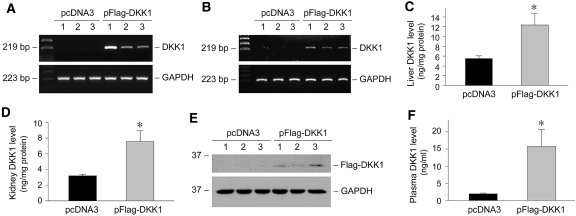

To block Wnt signaling, we used a hydrodynamic-based gene delivery approach20,21 by intravenous injection of naked plasmid vector encoding DKK1, a secreted Wnt antagonist that specifically blocks the canonical pathway of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. As shown in Figure 7, A and B, delivery of DKK1 gene by this approach resulted in substantial expression of exogenous DKK1 transgene in liver and kidney, as revealed by RT-PCR analysis using human-specific primers. Quantitative ELISA that detects both human and endogenous mouse DKK1 also showed an increased DKK1 protein in liver and kidney after plasmid injection (Figure 7, C and D). Similarly, human Flag-tagged DKK1 protein was detectable in kidney with specific anti-Flag antibody (Figure E). Because it is a secreted protein, circulating DKK1 level also elevated markedly after plasmid injection (Figure 7F).

Figure 7.

Expression of exogenous DKK1 after gene therapy. (A and B) RT-PCR analysis demonstrates the expression of exogenous DKK1 gene in liver (A) and kidney (B) after plasmid injection. Total RNA was prepared from liver and kidney at 16 h after DKK1 plasmid injected and subjected to RT-PCR analysis for human DKK1 expression. Numbers (1, 2, and 3) indicate each individual animal in a given group. (C and D) ELISA analysis shows an increased DKK1 protein in liver (C) and kidney (D) after gene delivery. DKK1 protein levels in liver and kidney homogenates were expressed as ng/mg total protein. *P < 0.05 versus pcDNA3 controls (n = 4 to 5). (E) Western blot analysis demonstrates renal expression of exogenous DKK1 protein. Kidney homogenates were immunoblotted with anti-Flag and anti-GAPDH antibodies, respectively. (F) ELISA analysis shows an increased DKK1 protein in the circulation after gene delivery. Plasma samples were collected from the mice at 16 h after DKK1 plasmid injection, and DKK1 protein levels were expressed as ng/ml. *P < 0.05 versus pcDNA3 controls (n = 3).

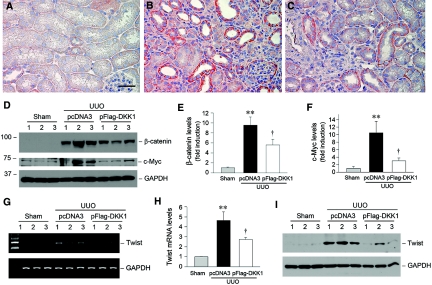

We found that delivery of DKK1 gene significantly inhibited the stabilization and accumulation of β-catenin in obstructed kidneys (Figure 8, A through C). Compared with the empty vector controls (Figure 8B), renal β-catenin protein, as shown by immunohistochemical staining, was reduced after exogenous DKK1 expression (Figure 8C). Consistent with a decreased β-catenin level, the numbers of cells with positive cytoplasmic and nuclear staining of β-catenin were reduced as well. Western blot analysis also showed that delivery of DKK1 gene reduced renal β-catenin abundance after obstructive injury (Figure 8, D and E). Furthermore, ectopic expression of DKK1 significantly inhibited the expression of several Wnt/β-catenin target genes such as c-Myc and Twist (Figure 8). Hence, DKK1 gene therapy effectively impedes the canonical pathway of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in diseased kidney.

Figure 8.

Delivery of DKK1 gene blocks Wnt/β-catenin signaling in obstructive nephropathy. (A through C) Representative micrographs demonstrate renal β-catenin expression and localization in sham mice (A), mice that underwent UUO and were administered an injection of pcDNA3 (B), and mice that underwent UUO and were administered an injection of pFlag-DKK1 plasmid (C). Bar = 40 μm. (D through F) Representative Western blots (D) and quantitative data (E and F) show that delivery of DKK1 gene reduced renal β-catenin and c-Myc abundance after obstructive injury. **P < 0.01 versus sham controls; †P < 0.05 versus pcDNA3 (n = 4 to 5). (G through I) DKK1 gene therapy suppresses Twist mRNA (G and H) and protein (I) expression in obstructed kidney. Representative RT-PCR (G) and Western blot (I) results and quantitative data (H) are presented. **P < 0.01 versus sham controls; †P < 0.05 versus pcDNA3 (n = 4 to 5).

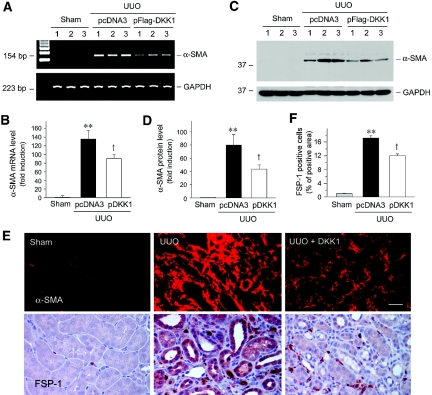

Blockade of Wnt Signaling Inhibits Renal α-Smooth Muscle Actin and Fibroblast-Specific Protein 1 Expression after Obstructive Injury

We next examined the effects of blockade of Wnt signaling on myofibroblast activation in the evolution of interstitial fibrosis after obstructive injury. As shown in Figure 9, A and B, UUO caused a dramatic induction of the mRNA expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), the molecular signature of myofibroblasts; however, delivery of DKK1 gene significantly suppressed renal α-SMA mRNA expression after injury. Ectopic expression of DKK1 also inhibited α-SMA protein expression in obstructed kidney (Figure 9, C and D). Similar results were obtained when the kidney sections were immunostained with antibody against α-SMA (Figure 9E).

Figure 9.

Blockade of Wnt signaling by DKK1 inhibits α-SMA and FSP-1 expression in the obstructed kidney. (A and B) Representative RT-PCR analysis (A) and quantitative data (B) show that delivery of DKK1 gene suppressed renal α-SMA mRNA expression after obstructive injury. (C and D) Representative Western blot (C) and quantitative data (D) demonstrate that DKK1 suppressed renal α-SMA protein expression after obstructive injury. Numbers (1, 2, and 3) denote each individual animal in a given group. Relative α-SMA mRNA (B) or protein (D) levels (fold induction over sham controls) were reported after normalization with GAPDH, respectively. **P < 0.01 versus sham controls; †P < 0.05 versus pcDNA3 (n = 4 to 5). (E) Representative micrographs demonstrate α-SMA protein localization by immunofluorescence staining and FSP-1 protein by immunohistochemical staining in different groups as indicated. Bar = 40 μm. (F) Quantitative determination of FSP-1 expression in different groups as indicated. **P < 0.01 versus sham controls; †P < 0.05 versus pcDNA3 (n = 4 to 5).

We also investigated the expression of fibroblast-specific protein 1 (FSP-1), also known as S100A4 protein, which is normally expressed in fibroblasts but not epithelia.22 As shown in Figure 9E, very few FSP-1–positive cells were detected in the interstitium of normal kidney, as shown by immunohistochemical staining. Obstructive injury apparently caused a marked induction of FSP-1 expression, and an increased number of interstitial and tubular epithelial cells became positive for FSP-1 staining; however, delivery of DKK1 gene not only reduced the overall numbers of renal FSP-1–positive cells (Figure 9F) but also particularly inhibited tubular expression of FSP-1 (Figure 9E).

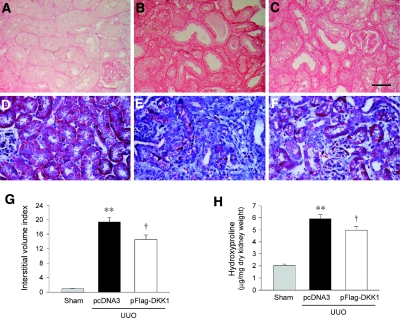

Blockade of Wnt Signaling Reduces Renal Fibrosis and Inhibits Interstitial Matrix Production

Figure 10 shows that inhibition of Wnt signaling by DKK1 attenuated renal interstitial fibrosis after UUO. Picrosirius red and Masson trichrome staining revealed a reduced interstitial injury and collagen deposition in the obstructed kidney after ectopic expression of exogenous DKK1 (Figure 10, A through F). This reduction of collagen deposition was associated with a decreased renal interstitial volume in the obstructed kidney after exogenous DKK1 expression (Figure 10G). Biochemical analysis of tissue hydroxyproline content demonstrated that blockade of Wnt signaling by DKK1 attenuated total collagen in the obstructed kidney, compared with controls (Figure 10H).

Figure 10.

Inhibition of Wnt signaling by DKK1 reduces renal interstitial injury and total collagen deposition after UUO. (A through F) Kidney sections were stained with Picrosirius red (A through C) and Masson trichrome (D through F) for assessment of collagen deposition. Representative micrographs from different groups as indicated are shown. (A and D) Sham controls. (B and E) Mice that underwent UUO and were administered an injection of pcDNA3. (C and F) Mice that underwent UUO and were administered an injection of pFlag-DKK1. Bar = 40 μm. (G) Graphic presentation shows renal interstitial volume in different groups as indicated. (H) DKK1 treatment reduced tissue hydroxyproline content in the obstructed kidney. Tissue hydroxyproline was expressed μg/mg dry kidney weight. **P < 0.01 versus sham controls; †P < 0.05 versus pcDNA3 (n = 4 to 5).

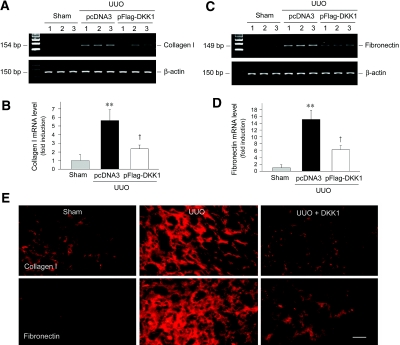

We then investigated the expression of type I collagen and fibronectin, two major components of interstitial matrix. As shown in Figure 11, A through D, obstructive injury induced a marked increase in the mRNA levels of type I collagen and fibronectin, and delivery of DKK1 gene significantly suppressed the expression of these matrix components. Similar results on type I collagen and fibronectin expression were also obtained by immunofluorescence staining. It seems clear that blocking the canonical pathway of Wnt/β-catenin signaling inhibits interstitial matrix gene expression and attenuates renal fibrotic lesions.

Figure 11.

Blockade of Wnt signaling by DKK1 inhibits type I collagen and fibronectin expression in obstructive nephropathy. (A and C) Representative RT-PCR analysis of renal mRNA levels of type I collagen (A) and fibronectin (C) in different treatment groups as indicated. Numbers (1, 2, and 3) denote each individual animal in a given group. (B and D) Graphic presentation of the mRNA levels of type I collagen (B) and fibronectin (D) in different groups. Relative mRNA levels were calculated and are expressed as fold induction over sham controls (value = 1.0) after normalization with β-actin. **P < 0.01 versus sham controls; †P < 0.05 versus pcDNA3 (n = 4 to 5). (E) Representative micrographs demonstrate type I collagen and fibronectin localization by immunofluorescence staining in different groups as indicated. Bar = 40 μm.

DISCUSSION

The results reported here represent the first systematic analysis of the expression and regulation of all members of the Wnt family and their Fzd receptor genes in normal and fibrotic kidneys. We demonstrate that Wnt upregulation after chronic renal injury leads to accumulation of β-catenin and induces the expression of its downstream target genes. Furthermore, blockade of the canonical pathway of Wnt signaling by DKK1 inhibits interstitial matrix gene expression and attenuates collagen deposition and tissue scarring. Our studies suggest that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling is hyperactive and detrimental in the evolution of renal interstitial fibrosis. These findings provide significant insights into the role and mechanisms of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in renal fibrogenesis and offer a new strategy in developing therapeutic modalities for the treatment of fibrotic kidney diseases.

Wnt/β-catenin signaling is generally considered to be silenced in adult tissues.1,5,16 It seems clear, however, that the vast majority of the members of both Wnt and Fzd receptor family genes are expressed at different levels in mouse adult kidney. This somewhat surprising finding suggests that Wnt signaling is important in the maintenance of renal cell and tissue homeostasis under normal physiologic conditions. Besides the well-characterized canonical pathway,5,9 in which β-catenin is the principal mediator, Wnt signals can be transmitted through several additional intracellular, β-catenin–independent, noncanonical pathways, in which the Wnt/Ca2+ and Wnt/planar cell polarity (PCP) routes are best described.8 In the Wnt/Ca2+ pathway, Wnts bind to Fzd receptor to activate Dvl; however, this results in an increase in intracellular Ca2+ and activation of protein kinase C and calmodulin kinase II.23,24 Functionally, activation of the Wnt/Ca2+ pathway may antagonize the Wnt/β-catenin signaling, providing a negative feedback mechanism.25 The Wnt/PCP pathway uses Fzd and Dvl as well but does not lead to β-catenin stabilization or Ca2+ influx in regulating the generation of PCP.26,27 The noncanonical pathways are often operated in response to distinct group of Wnt ligands and Fzd receptors, such as Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt11, and Fzd2 through 410,23; therefore, although the role of specific Wnts and Fzd receptors in normal kidney remains to be determined, in view of the expression pattern of different Wnts and Fzd receptor, we can speculate that both canonical and noncanonical pathways of Wnt signaling are at work, ensuring a functional multiplicity and signal output homeostasis under normal circumstances. It is becoming apparent that the relative silence of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in adult kidney does not represent a lack of Wnt expression but might in fact result from a balance of the expression between the stimulatory and inhibitory Wnt and Fzd genes,28 as well as the constitutive expression of various Wnt antagonists.

One of the striking observations in this study is the concurrent induction of multiple Wnt genes in the fibrotic kidney after obstructive injury. In fact, except for Wnt5b, Wnt8b, and Wnt9b, all members of Wnt family genes were upregulated, albeit divergent in induction dynamics (Figure 1). In addition, the expression of numerous Fzd receptor genes was induced (Figure 3). Perhaps unexpected, there is no single gene among both Wnt and Fzd receptor families whose expression was suppressed during the entire experimental period. This suggests that most members of Wnt family proteins are responsive positively to injurious stimuli after UUO. Although such a reexpression or induction of the embryonic genes after injury is not without precedent, the observation that 16 of 19 Wnt genes were induced concurrently in a particular setting of disease is astonishing. Naturally, induction of Wnt and Fzd genes would lead to the stabilization and accumulation of β-catenin, the mediator of the Wnt canonical pathway,29 by preventing its phosphorylation and degradation via β-transducin repeat-containing protein–mediated ubiquitination.1,5 Indeed, despite that Wnt ant-agonists DKK1 through 4 were slightly induced (Figure 4), β-catenin protein is markedly increased and predominantly localized in the cytoplasm and nuclei of tubular epithelial cells (Figure 5), indicative of a prevailed Wnt/β-catenin signaling in diseased kidney.

It should be pointed out that we do not know the sources and localization of Wnts in vivo in this study, because of the lack of specific and workable antibodies against many vertebrate Wnt proteins in immunohistochemical studies. A previous in situ hybridization study showed that Wnt4 mRNA expression was induced in collecting duct epithelium and in activated interstitial myofibroblasts after various injuries.18 Because Wnt is a secreted protein, cells may readily access and respond to Wnts in the extracellular mellitus in an autocrine or paracrine manner, regardless of the sources. Because tubular epithelial cells express the majority of Fzd receptors in vitro (data not shown), it is plausible to assume that they could be the main targets of Wnt signaling in diseased kidney. This notion is supported by the observation that β-catenin was primarily activated in tubular epithelium after obstructive injury (Figure 5).

The ultimate responses of Wnt/β-catenin signaling ought to reflect on regulating particular gene expression. In that regard, numerous target genes downstream of Wnt/β-catenin have been characterized in diverse types of cells. On the basis of previous reports in other biologic systems,30–33 we identified several putative target genes of Wnt/β-catenin in fibrotic kidney, including Twist, LEF1, fibronectin, and c-Myc. The expression of these genes is closely correlated with β-catenin abundance in vivo (Figure 6) and is inhibited specifically after Wnt signaling is blocked with DKK1 (Figures 8 and 11). Among these genes, Twist, a transcription factor of the basic helix-loop-helix class, has been shown to play a pivotal role in mediating epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in different circumstances.30 Twist not only is able to repress E-cadherin gene transcription by binding to the E-boxes in its promoter region but also induces the de novo expression of mesenchymal markers.34,35 In view of the importance of tubular EMT in the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis,36,37 Twist may function as a critical mediator of Wnt/β-catenin in promoting EMT and renal fibrogenesis. Of note, Wnt/β-catenin signaling may be amplified in diseased kidney because one of its targets is LEF1,31 the DNA-binding transcription factor that interacts with β-catenin, leading to the formation of a trans-activating protein complex. As another direct target of Wnt/β-catenin,33 the significance of an increased fibronectin expression in the evolution of renal fibrosis can be easily envisioned. Notably, the expression of c-Myc, a widely known target of Wnt/β-catenin that is implicated in regulating cell proliferation,1,3,32 is not exactly correlated with β-catenin levels (Figure 6). The reason behind this discrepancy is unknown, but it could suggest that a certain group of Wnts, such as Wnt1, Wnt7a, and Wnt7b, which share a similar expression pattern with c-Myc after UUO, might be responsible specifically for c-Myc induction in diseased kidney. It should be noted that we cannot exclude the possibility that other transcription factors may also participate in the regulation of Wnt target genes in fibrotic kidney in vivo. More studies are clearly needed in the area.

Our study also suggests that targeting Wnt/β-catenin signaling might be an effective strategy to hinder the progression of renal interstitial fibrosis. Delivery of exogenous DKK1 via naked plasmid injection led to substantial expression of exogenous DKK1 in kidney as well as in liver (Figure 7). Because it is a secreted protein, exogenous DKK1 produced in kidney in situ and/or from liver via circulation presumably can access to and target the hyperactive Wnt signaling in diseased kidney. This results in a reduction of β-catenin accumulation and suppression of Wnt/β-catenin target genes in fibrotic kidney, leading to a reduction of renal matrix deposition and fibrosis. This conclusion is also substantiated by a previous report demonstrating that administration of recombinant sFRP4 protein was able to ameliorate renal fibrotic lesions.17 It is worthwhile to stress that DKK proteins as Wnt antagonists are unique because they specifically block Wnt ligands binding to LRP5/6, the co-receptors that are obligatory for transmitting the canonical pathway of Wnt/β-catenin signaling11,12; therefore, our observation that DKK1 inhibits renal fibrosis clearly underscores a pivotal role of the canonical pathway of a hyperactive Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the pathogenesis of renal interstitial fibrosis.

CONCISE METHODS

Animals

Male CD-1 mice that weighed approximately 18 to 22 g were purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley (Indianapolis, IN). UUO was performed using an established protocol, as described previously.38 Sham-operated mice were used as normal controls. At different time points after surgery, groups of mice (n = 5) were killed and kidneys were removed for various analyses. For delivery of human DKK1 gene, naked DKK1 expression plasmid (pFlag-DKK1; provided by Dr. Xi He, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA)11 was injected intravenously at 1 mg/kg body wt before (day −1) UUO, by use of a hydrodynamics-based in vivo gene transfer approach, as described previously.20,21 Control UUO mice were administered an injection of empty vector pcDNA3 plasmid in an identical manner. Mouse model of adriamycin nephropathy was established according to the protocol described previously.19 Briefly, male BALB/c mice (Harlan Sprague-Dawley) were administered via tail vein an injection of adriamycin (doxorubicin hydrochloride; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 10 mg/kg body wt. Mice were killed at 5 wk after adriamycin injection, and kidney tissue was collected for various analyses. Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pittsburgh.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared from kidney tissue by using TRIzol reagent, according to the protocol specified by the manufacturer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After reverse transcription of the RNA, cDNA was used as a template in PCR reactions using gene-specific primer pairs. Approximately 25 to 30 cycles for amplification in the linear range were used. Some experiments were performed without addition of RT. After quantification of band intensities by using densitometry, the relative steady-state levels of mRNA were calculated after normalizing to β-actin or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The sequences of the primer sets are given in the Supplemental Table 3.

Western Blot Analysis

The preparation of kidney tissue homogenates and Western blot analysis of protein expression were carried out by using routine procedures as described previously.39 The primary antibodies were obtained from the following sources: Anti-Wnt4 (AF475; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN); anti-Wnt7a (sc-26361), anti–c-Myc (sc-764), and anti-Twist (sc-15393; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); anti–β-catenin (cat. no. 610154; BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA); anti-Flag (M2; F3165) and anti–α-SMA (clone 1A4) (Sigma); and anti–glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Ambion, Austin, TX).

Immunohistochemical and Immunofluorescence Staining

Immunohistochemical staining of kidney sections was performed by an established protocol.40 Paraffin-embedded sections were stained with polyclonal rabbit anti–β-catenin antibody (ab-15180; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and polyclonal rabbit anti-S100A4 (FSP-1) antibody (A5114; DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) using the Vector M.O.M. immunodetection kit, according to the protocol specified by the manufacturer (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Indirect immunofluorescence staining was carried out according to established procedures.39 Briefly, kidney cryosections were incubated with specific primary antibodies against α-SMA, collagen I (cat. no. 1310-01; Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL), and fibronectin (cat. no. 610078; BD Transduction Laboratories), respectively, followed by staining with cyanine Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Slides were viewed with a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope equipped with a digital camera (Melville, NY). Nonimmune normal control IgG was used to replace the primary antibody as negative control, and no staining occurred. Quantification of the staining was carried out by a grid counting–based, computer-aided morphometric analysis, as described previously.41

Quantitative Determination of DKK1 Protein Levels

DKK1 protein levels in plasma and tissues were determined quantitatively by an ELISA using a specific DKK1 detection kit (R&D Systems). This ELISA kit detects both human (exogenous) and mouse endogenous DKK1 protein. Plasma samples were collected from mice that were administered an injection of either pFlag-DKK1 expression vector or pcDNA3 plasmid. For determining tissue DKK1 levels, liver and kidney from mice were homogenized in the extraction buffer containing 20 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.5), 2 M NaCl, 0.1% Tween-80, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM PMSF, as described previously.42 After centrifugation at 19,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, the supernatant was recovered for DKK1 assay, according to the protocol specified by the manufacturer. Total protein levels were determined using a bicinconinic acid protein assay kit (Sigma).

Picrosirius Red Staining and Morphometric Analysis

For evaluation of the collagen deposition, 3-μm sections of paraffin-embedded tissue were stained with the picrosirius red. Sections were deparaffinized by baking at 55°C for 1 h, hydrated, and stained with picrosirius red solution (0.1% sirius red in saturated picric acid) for 18 h, followed by treatment with 0.01 N HCl for 2 min, dehydration, and coverslip mounting. Masson trichrome staining was carried out by routine procedures. Stained sections were examined by Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope equipped with a digital camera (Melville, NY). For estimation of interstitial volume, computer-aided morphometric analysis on Picrosirius red–stained sections was performed, as described previously.40 Briefly, a grid containing 117 (13 × 9) sampling points was superimposed on images of cortical high-power field (×400). The number of grid points overlying interstitial space (interstitial volume index) was counted and expressed as a percentage of all sampling points. For each kidney, 10 randomly selected, nonoverlapping fields were analyzed in a blinded manner.

Quantitative Determination of Tissue Hydroxyproline Content

For quantitative measurement of collagen deposition in the kidney, total tissue collagen was estimated by biochemical analysis of the hydroxyproline in the hydrolysates extracted from kidney samples. This assay is based on the observation that essentially all of the hydroxyproline in animal tissues is found in collagen. Briefly, kidney samples were dried at 110°C for 48 h and then accurately weighed. Dry kidney was hydrolyzed in sealed, oxygen-purged glass ampoules containing 2 ml of 6 N HCl at 110°C for 24 h. Hydroxyproline content in the hydrolysates was chemically quantified according to the techniques previously described.38,43 Tissue hydroxyproline content was expressed as μg/mg dry kidney weight.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was carried out using SigmaStat software (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA). Comparison between groups was made using one-way ANOVA followed by Student-Newman-Kuels test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants DK061408, DK064005, and DK071040.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at http://www.jasn.org/.

References

- 1.Clevers H: Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell 127: 469–480, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinto D, Clevers H: Wnt control of stem cells and differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. Exp Cell Res 306: 357–363, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson MD, Monga SP: WNT/beta-catenin signaling in liver health and disease. Hepatology 45: 1298–1305, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fodde R, Brabletz T: Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in cancer stemness and malignant behavior. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19: 150–158, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang H, He X: Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: new (and old) players and new insights. Curr Opin Cell Biol 20: 119–125, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White BD, Nguyen NK, Moon RT: Wnt signaling: It gets more humorous with age. Curr Biol 17: R923–R925, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macdonald BT, Semenov MV, He X: SnapShot: Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Cell 131: 1204, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Semenov MV, Habas R, Macdonald BT, He X: SnapShot: Noncanonical Wnt signaling pathways. Cell 131: 1378, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moon RT, Kohn AD, De Ferrari GV, Kaykas A: WNT and beta-catenin signalling: Diseases and therapies. Nat Rev Genet 5: 691–701, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeng G, Awan F, Otruba W, Muller P, Apte U, Tan X, Gandhi C, Demetris AJ, Monga SP: Wnt'er in liver: Expression of Wnt and frizzled genes in mouse. Hepatology 45: 195–204, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Semenov MV, Tamai K, Brott BK, Kuhl M, Sokol S, He X: Head inducer Dickkopf-1 is a ligand for Wnt coreceptor LRP6. Curr Biol 11: 951–961, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niehrs C: Function and biological roles of the Dickkopf family of Wnt modulators. Oncogene 25: 7469–7481, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroll TJ, Park JS, Hayashi S, Majumdar A, McMahon AP: Wnt9b plays a central role in the regulation of mesenchymal to epithelial transitions underlying organogenesis of the mammalian urogenital system. Dev Cell 9: 283–292, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iglesias DM, Hueber PA, Chu L, Campbell R, Patenaude AM, Dziarmaga AJ, Quinlan J, Mohamed O, Dufort D, Goodyer PR: Canonical WNT signaling during kidney development. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F494–F500, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Major MB, Camp ND, Berndt JD, Yi X, Goldenberg SJ, Hubbert C, Biechele TL, Gingras AC, Zheng N, Maccoss MJ, Angers S, Moon RT: Wilms tumor suppressor WTX negatively regulates WNT/beta-catenin signaling. Science 316: 1043–1046, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He X: Cilia put a brake on Wnt signalling. Nat Cell Biol 10: 11–13, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Surendran K, Schiavi S, Hruska KA: Wnt-dependent beta-catenin signaling is activated after unilateral ureteral obstruction, and recombinant secreted frizzled-related protein 4 alters the progression of renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2373–2384, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Surendran K, McCaul SP, Simon TC: A role for Wnt-4 in renal fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F431–F441, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Wang YP, Tay YC, Harris DC: Progressive adriamycin nephropathy in mice: Sequence of histologic and immunohistochemical events. Kidney Int 58: 1797–1804, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai C, Yang J, Bastacky S, Xia J, Li Y, Liu Y: Intravenous administration of hepatocyte growth factor gene ameliorates diabetic nephropathy in mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 2637–2647, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai C, Yang J, Liu Y: Single injection of naked plasmid encoding hepatocyte growth factor prevents cell death and ameliorates acute renal failure in mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 411–422, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strutz F, Okada H, Lo CW, Danoff T, Carone RL, Tomaszewski JE, Neilson EG: Identification and characterization of a fibroblast marker: FSP1. J Cell Biol 130: 393–405, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuhl M, Sheldahl LC, Park M, Miller JR, Moon RT: The Wnt/Ca2+ pathway: A new vertebrate Wnt signaling pathway takes shape. Trends Genet 16: 279–283, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slusarski DC, Yang-Snyder J, Busa WB, Moon RT: Modulation of embryonic intracellular Ca2+ signaling by Wnt-5A. Dev Biol 182: 114–120, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torres MA, Yang-Snyder JA, Purcell SM, DeMarais AA, McGrew LL, Moon RT: Activities of the Wnt-1 class of secreted signaling factors are antagonized by the Wnt-5A class and by a dominant negative cadherin in early Xenopus development. J Cell Biol 133: 1123–1137, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adler PN, Lee H: Frizzled signaling and cell-cell interactions in planar polarity. Curr Opin Cell Biol 13: 635–640, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fanto M, McNeill H: Planar polarity from flies to vertebrates. J Cell Sci 117: 527–533, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peifer M, Polakis P: Wnt signaling in oncogenesis and embryogenesis: A look outside the nucleus. Science 287: 1606–1609, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harris TJ, Peifer M: Decisions, decisions: Beta-catenin chooses between adhesion and transcription. Trends Cell Biol 15: 234–237, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howe LR, Watanabe O, Leonard J, Brown AM: Twist is up-regulated in response to Wnt1 and inhibits mouse mammary cell differentiation. Cancer Res 63: 1906–1913, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hovanes K, Li TW, Munguia JE, Truong T, Milovanovic T, Lawrence Marsh J, Holcombe RF, Waterman ML: Beta-catenin-sensitive isoforms of lymphoid enhancer factor-1 are selectively expressed in colon cancer. Nat Genet 28: 53–57, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He TC, Sparks AB, Rago C, Hermeking H, Zawel L, da Costa LT, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW: Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science 281: 1509–1512, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Langhe SP, Sala FG, Del Moral PM, Fairbanks TJ, Yamada KM, Warburton D, Burns RC, Bellusci S: Dickkopf-1 (DKK1) reveals that fibronectin is a major target of Wnt signaling in branching morphogenesis of the mouse embryonic lung. Dev Biol 277: 316–331, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C, Savagner P, Gitelman I, Richardson A, Weinberg RA: Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell 117: 927–939, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kida Y, Asahina K, Teraoka H, Gitelman I, Sato T: Twist relates to tubular epithelial-mesenchymal transition and interstitial fibrogenesis in the obstructed kidney. J Histochem Cytochem 55: 661–673, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Y: Epithelial to mesenchymal transition in renal fibrogenesis: Pathologic significance, molecular mechanism, and therapeutic intervention. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1–12, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalluri R, Neilson EG: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Invest 112: 1776–1784, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang J, Dai C, Liu Y: Hepatocyte growth factor gene therapy and angiotensin II blockade synergistically attenuate renal interstitial fibrosis in mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 2464–2477, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang J, Liu Y: Blockage of tubular epithelial to myofibroblast transition by hepatocyte growth factor prevents renal interstitial fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 96–107, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan X, Li Y, Liu Y: Paricalcitol attenuates renal interstitial fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 3382–3393, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan X, Wen X, Liu Y: Paricalcitol inhibits renal inflammation by promoting vitamin D receptor-mediated sequestration of NF-κB signaling. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1741–1752, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang J, Chen S, Huang L, Michalopoulos GK, Liu Y: Sustained expression of naked plasmid DNA encoding hepatocyte growth factor in mice promotes liver and overall body growth. Hepatology 33: 848–859, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Englert JM, Hanford LE, Kaminski N, Tobolewski JM, Tan RJ, Fattman CL, Ramsgaard L, Richards TJ, Loutaev I, Nawroth PP, Kasper M, Bierhaus A, Oury TD: A role for the receptor for advanced glycation end products in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol 172: 583–591, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.