SYNOPSIS

Objective

Some studies show an association between asthma and obesity, but it is unknown whether exposure to mold will increase the risk of asthma attacks among obese people. This study examined whether obese adults have a higher risk of asthma attacks than non-obese adults when exposed to indoor mold.

Methods

We used data from the 2005 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System to conduct a cross-sectional analysis among 9,668 respondents who reported exposure to indoor mold.

Results

With exposure to indoor mold, weighted prevalence of asthma attacks among obese respondents was 11.4% (95% confidence interval [CI] 6.0, 20.6], which was 2.3 times as high as among the exposed non-obese respondents (5.0%, 95% CI 2.8, 8.8). This ratio was almost the same as the ratio of 2.0:1 between the obese respondents (5.7%, 95% CI 4.6, 7.2) and the non-obese respondents (2.8%, 95% CI 2.3, 3.9) when neither group had exposure to mold. The odds ratio of asthma attack among obese people was 3.10 (95% CI 1.10, 8.67) for those with exposure to mold and 2.21 (95% CI 1.54, 3.17) for those without exposure to mold after adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and smoking status.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that obese adults who have been exposed to indoor mold may not necessarily have a higher risk of asthma attack than obese adults who have not been exposed, even though obesity and exposure to indoor mold are both major risk factors for asthma attack. Medical professionals should not only incorporate weight-control or weight-reduction measures as the components of asthma treatment plans, but also advise asthma patients to avoid exposure to indoor mold.

Indoor molds are colonies of different species of fungi that grow in damp houses at normal room temperature. Exposure to airborne molds or mold spores may contribute to various respiratory health problems, including pneumonia and hypersensitivity pneumonitis.1 Many studies have also found that clinically verified cases of asthma, as well as self-reported cases of physician-diagnosed asthma, were associated with mold and dampness indoors.2–5

Obesity has become an increasingly prevalent health problem in many developed and developing countries in the last two decades.6–8 In the United States and its territories, the prevalence of obesity (based on self-reports) doubled from 1990 to 2002 (from 11.6% to 22.1%).9

Asthma is also a prevalent health problem among developed countries. Based on the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the self-reported prevalence of asthma among adults in 2006 was 8.4%.10 An association between obesity and asthma has been reported in many studies,11–14 although considerable debate remains about the existence of the association and its meaning.15–17 Conceivably, additional studies from different perspectives will help us understand more about the relationship between asthma and obesity.

Asthma is a respiratory disease characterized by airway obstruction and bronchial hyper-responsiveness. Patients may have no asthma-related symptoms during certain periods of time until another attack occurs. An asthma attack can be triggered by many factors such as infections, exposure to mold, and pollens.18–21 Although reports have demonstrated that exposure to molds is associated with the development of asthma,2–5 the hypothesis that molds or fungi contribute to asthma development and trigger asthma attack is still controversial.22 More studies with stronger evidence are needed to support this hypothesis. Furthermore, although evidence shows that obesity is associated with asthma,11–14 it is unclear whether obese adults have a higher risk of triggering an asthma attack than non-obese adults when exposed to indoor mold, and whether there is a biologic plausibility for the potential interaction between obesity and mold as it relates to asthma attacks. In this study, we used data from the 2005 BRFSS to examine whether there is a higher risk for initiating asthma attacks among obese adults than among non-obese adults when both populations are exposed to indoor mold.

METHODS

BRFSS, the world's largest standardized, state-based telephone survey, collects data on health risks and health conditions or chronic diseases (e.g., adult asthma and obesity) from noninstitutionalized adults aged 18 years and older in U.S. states and territories. The characteristics and advanced survey design of the BRFSS have been described elsewhere.23,24 Detailed information about the BRFSS can be accessed from http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.htm, and all questionnaires can be accessed from http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfssQuest.

In the 2005 BRFSS, two states (Maryland and Texas) participated in the optional survey module regarding the quality of indoor air. Respondents were asked, “Do you currently have mold in your home on an area greater than the size of a dollar bill?” In the core question section of the questionnaire, respondents were asked, “Have you EVER been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professional that you had asthma?” Respondents who answered “yes” were considered to have lifetime asthma. Respondents were also asked in the optional module on asthma history (included by all 50 states), “During the past 12 months, have you had an episode of asthma or an asthma attack?” We considered a respondent to have had an incident of asthma attack only if she/he responded positively to both questions.

We used self-reported heights and weights to calculate the body mass index (BMI) in kilograms/meters2 (kg/m2). The respondent was classified as obese if the BMI was ≥30 kg/m2 and non-obese if the BMI was <30 kg/m2. We used BMI as a dichotomized variable in our models for the simplicity in presenting our analysis results. To validate our models that used dichotomized BMI, we also used BMI as a continuous variable in our logistic regression models.

In all, 9,668 respondents aged 18 years or older from Maryland or Texas who answered the question regarding exposure to indoor mold and the two questions regarding asthma were included in our study. Other states were not selected because they did not have complete data for both mold exposure and asthma attack.

The Council of American Survey Research Organizations' response rates in the 2005 BRFSS were 37.6% for Maryland and 45.2% for Texas. The cooperation rates were 67.0% for Maryland and 67.9% for Texas. The cooperation rate reflects all completed interviews among the number of contacted eligible respondents in the BRFSS.

To determine whether obese people exposed to indoor mold had a higher risk of asthma attack than non-obese people, we divided the data into two subsets: exposure to indoor mold and no exposure to indoor mold (each group included obese and non-obese respondents). The first group (exposure to mold) had 525 respondents and the second group (no exposure) had 9,143 respondents.

The weighted prevalence of asthma attack was calculated separately for the two subgroups by exposure to indoor mold, age, sex, race/ethnicity, obesity, and smoking. The association of asthma attack caused by obesity, mold exposure, and other risk factors was tested using the Chi-square or Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test of association. The odds of asthma attack with exposure to indoor mold were examined by using adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) obtained from univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses conducted separately on the two datasets. We used the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test for our regression models. We adjusted the same covariates in our regression models using BMI as a continuous variable as for those using a dichotomized one. The value of continuous BMI variable was divided by 10 for each record used in those models.

Because of the complex sampling design in the BRFSS, we used SUDAAN25 to calculate the weighted prevalence of asthma attack and standard error to adjust for the effects of sampling bias, weights, and design effects.

RESULTS

The weighted prevalence of exposure to indoor mold was 5.6% (95% confidence interval [CI] 4.9, 6.4; n=9,668) among all respondents from both states. The overall prevalence of obesity was 26.6% (95% CI 25.3, 28.0; n=9,079). The prevalence of lifetime asthma was 11.7% (95% CI 10.8, 12.7; n=9,647) among all respondents. The overall prevalence of an asthma attack was 3.7% (95% CI 3.2, 4.3; n=9,079), with an estimate of 6.2% (95% CI 5.0, 7.7; n=2,350) for obese respondents and 3.0% (95% CI 2.4, 3.6; n=6,729) for non-obese respondents.

The prevalence of asthma attack was 7.3% (95% CI 4.7, 11.2) among people exposed to indoor mold (n=525), which was slightly more than twice the prevalence among people without such exposure (3.5%, 95% CI 3.0, 4.1; n=9,143) (Table 1). Among non-obese respondents, the prevalence of asthma attacks (5.0%, 95% CI 2.8, 8.8) with exposure to indoor mold was 1.8 times as high as for those without exposure (2.8%, 95% CI 2.3, 3.9). Among obese respondents, the prevalence of asthma attacks (11.4%, 95% CI 6.0, 20.6) with exposure to indoor mold was twice as high as the prevalence without exposure (5.7%, 95% CI 4.6, 7.2). In other words, exposure to indoor mold increased the risk of asthma attack by 100.0% among obese respondents and almost 80.0% among non-obese respondents. Among those without exposure to indoor mold, obese respondents had a rate of asthma attack that was twice that of non-obese respondents (5.7% vs. 2.8%, p=0.0001). Among people with exposure to mold, the prevalence of asthma attacks was 2.3 times as high among obese respondents as among non-obese respondents (11.4% vs. 5.0%, p=0.1012). In other words, those who were obese had a 100.0% increase in asthma attacks among people without mold exposure and a 130% increase in asthma attacks among people with mold exposure.

Table 1.

Distribution of asthma attack by demography and risk factors, BRFSS 2005

aUnweighted sample size (sample sizes vary due to missing information)

bWeighted prevalence

BRFSS = Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

CI = confidence interval

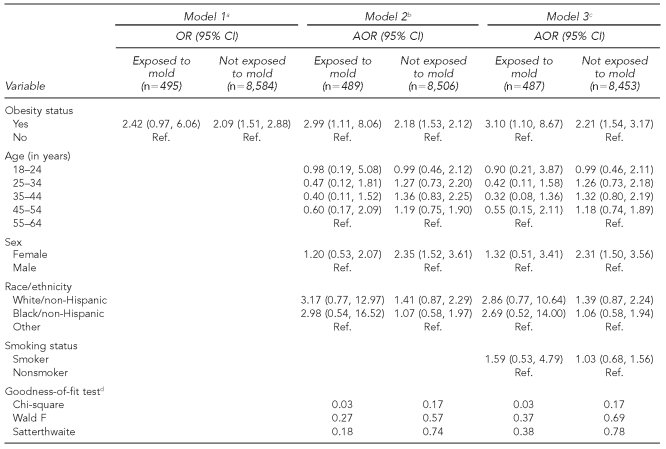

With exposure to indoor mold, the OR for asthma attack among obese people was 2.42 (95% CI 0.97, 6.06) (Table 2); the AOR of this event among obese people was 2.99 (95% CI 1.11, 8.06) after adjusting for age, sex, and race/ethnicity, and 3.10 (95% CI 1.10, 8.67) after adjusting for these three variables plus smoking status. In all cases, non-obese respondents were the referent group.

Table 2.

Odds ratio of asthma attack with and without exposure to indoor mold for adults ≥18 years of age

aOdds ratio without adjustment

bAOR adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity

cAOR adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and smoking

dHosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test

OR = odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

AOR = adjusted odds ratio

Ref. = referent group

Without exposure to indoor mold, the OR of asthma attack among obese respondents was 2.09 (95% CI 1.51, 2.88) when non-obese respondents were the referent group. The AOR among obese respondents was 2.18 (95% CI 1.58, 2.12) after adjusting for age, sex, and race/ethnicity, and 2.21 (95% CI 1.54, 3.17) after additional adjustment for smoking status, with non-obese respondents as the referent group.

The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test showed that the p-values for both Wald F and Satterthwaite F were large (p>0.05). Therefore, our null hypothesis was not rejected and our models were a good fit for the data. In addition, in our logistic regression models using BMI as a continuous variable, we found that with exposure to indoor mold, the OR for asthma attack among obese respondents was 1.78 (95% CI 1.03, 3.07); after adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and smoking, the AOR among obese respondents was 1.79 (95% CI 1.08, 2.98); without exposure to indoor mold, the OR of asthma attack among obese respondents was 1.56 (95% CI 1.29, 1.88); and after adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and smoking, the AOR among obese respondents was 1.58 (95% CI 1.31, 1.90). Similar results were found whether we used BMI as a continuous or a dichotomized variable. This suggests that using BMI as a dichotomized variable in our models was valid.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study using data from the BRFSS to evaluate the likelihood of asthma attack among obese and non-obese adults exposed to indoor mold. Previous studies have demonstrated that asthma is associated with obesity.11–17 But there is also some debate about the existence of the association and its meaning.15–17 Our findings show that the risk of asthma attacks among obese people is higher than in non-obese people with or without exposure to indoor mold. With exposure, the ratio was 2.3:1; without exposure it was 2.0:1. This further confirms the association of asthma with obesity.

Why obese people have a higher risk of asthma attack has not been clearly established. Some studies indicate that people with asthma are far more likely to be obese than people without asthma, and this leads to a debate about whether asthma increases the risk of obesity or vice versa. More studies are needed to solve this debate. Regardless of how the issue is resolved, the finding in our study—that with exposures to indoor mold, the prevalence of asthma attack among obese people is twice as high as that among non-obese people—suggests that health or medical professionals, while treating asthma patients, should offer advice to help them control or reduce their weight and avoid exposure to indoor mold.

In our study, the ratio of asthma attack between those exposed to indoor mold and the unexposed was 2.0:1 among obese people and 1.8:1 among non-obese people, which are almost the same ratios when considering the margin of error. Because obesity increased the prevalence of asthma attack by about 100% to 130%, and exposure to mold increased it by about 80% to 100%, we were expecting the prevalence of asthma attack among obese respondents exposed to indoor mold to be about four times as high as among non-obese respondents without exposure. Instead, the prevalence (11.4%) of asthma attack among obese respondents with exposure to mold was only twice as high as that of obese respondents without exposure (5.7%). This ratio was almost the same (2.3:1) as that for the obese vs. the non-obese respondents among those with exposure to indoor mold when considering the margin of error. Therefore, we could not conclude that obese respondents had a higher risk of asthma attack than non-obese respondents when both were exposed to mold.

Limitations

Some studies have demonstrated the association of mold exposure with the exacerbation of asthma caused by allergies.26–29 Because mold is a general term for all species of molds, some of them (probably most of them) may not have the allergens that lead to initiation and even exacerbation of asthma. In addition, there are two types of asthma: allergic and nonallergic. Nonallergic asthma may not be triggered or exacerbated in patients exposed to the molds with the specific allergens that could lead to exacerbation of allergic asthma. In this study, the data collected on mold and asthma in the BRFSS did not allow us to discern the species of molds nor the types of asthma. This is one of the important limitations that we should consider while interpreting our data.

Other limitations should also be considered. The BRFSS is a telephone survey that excludes people with no telephones, which may result in sampling bias. All of the data in the survey were self-reported and may be subject to recall bias. There were no data on dosage or time regarding exposure to indoor mold; similarly, information about the severity of the asthma was not available. Another concern is that the sample of those with exposure to indoor mold was much smaller than that without exposure to indoor mold, which may have led to erroneous conclusions because of sampling bias. Furthermore, we could not consider the effect of geography in our regression analysis because we had data from only two states. We were able to consider the effect of season on exposure to mold and asthma attack, but we did not include it in our regression models because we did not find that it had a statistically significant effect. Finally, because this was a cross-sectional study, and given the limitations of the data, we cannot infer causation until further study is conducted.

CONCLUSION

Our study suggests that obese adults may not necessarily have a higher risk of asthma attack than non-obese adults who are exposed to indoor mold, even though both obesity and exposure to indoor mold were associated with an increased risk of asthma attack among all adults in this study. We found that obesity increased the prevalence of asthma attack by about 100% to 130%, and exposure to mold increased the prevalence of this event by about 80% to 100%. Therefore, medical professionals should not only advise asthma patients to incorporate measures of weight control or weight reduction as one component of their treatment plan, but should also advise them to avoid exposure to indoor mold.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System coordinators from Maryland and Texas and the members of the Survey Operation Team in the Behavioral Surveillance Branch, National Center for Chronic Diseases/Division for Adult and Community Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for their help in collecting the data used in the analysis.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Menzies D, Bourbeau J. Building-related illnesses. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1524–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711203372107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burr ML, Mullins J, Merrett TG, Stott NC. Indoor moulds and asthma. J R Soc Health. 1988;108:99–101. doi: 10.1177/146642408810800311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dales RE, Burnett R, Zwanenburg H. Adverse health effects among adults exposed to home dampness and molds. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143:505–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pirhonen I, Nevalainen A, Husman T, Pekkanen J. Home dampness, moulds and their influence on respiratory infections and symptoms in adults in Finland. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:2618–22. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09122618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zock JP, Jarvis D, Luczynska C, Sunyer J, Burney P. Housing characteristics, reported mold exposure, and asthma in the European Community Respiratory Health Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:285–92. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.126383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conway B, Rene A. Obesity as a disease: no lightweight matter. Obes Rev. 2004;5:145–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodman E, Daniels SR, Morrison JA, Huang B, Dolan LM. Contrasting prevalence of and demographic disparities in the World Health Organization and National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III definitions of metabolic syndrome among adolescents. J Pediatr. 2004;145:445–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.State-specific prevalence of obesity among adults—United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(36):985–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Nationwide (states, DC, and territories) obesity: by body mass index. 2007 Apr 12. [cited 2008 Dec 2]. Available from: URL: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/BRFSS/display.asp?cat=OB&yr=2002&qkey=4409&state=US.

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System: prevalence and trends data: nationwide (states, DC, and territories)—2006 asthma. [cited 2008 Jul 22]. Available from: URL: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/display.asp?cat=AS&yr=2006&qkey=4416&state=US.

- 11.Akerman MJ, Calacanis CM, Madsen MK. Relationship between asthma severity and obesity. J Asthma. 2004;41:521–6. doi: 10.1081/jas-120037651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Dales R, Jiang Y. The association between obesity and asthma is stronger in nonallergic than allergic adults. Chest. 2006;130:890–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.3.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kronander UN, Falkenberg M, Zetterstrom O. Prevalence and incidence of asthma related to waist circumference and BMI in a Swedish community sample. Respir Med. 2004;98:1108–16. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaheen SO. Obesity and asthma: cause for concern? Clin Exp Allergy. 1999;29:291–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plumb J, Brawer R, Brisbon N. The interplay of obesity and asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2007;7:385–9. doi: 10.1007/s11882-007-0058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brenner JS, Kelly CS, Wenger AD, Brich SM, Morrow AL. Asthma and obesity in adolescents: is there an association? J Asthma. 2001;38:509–15. doi: 10.1081/jas-100105872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.To T, Vydykhan TN, Dell S, Tassoudji M, Harris JK. Is obesity associated with asthma in young children? J Pediatr. 2004;144:162–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gern JE, Lemanske RF., Jr. Infectious triggers of pediatric asthma. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2003;50:555–75. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(03)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacDowell AL, Bacharier LB. Infectious triggers of asthma. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2005;25:45–66. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mo F, Robinson C, Choi BC, Li FC. Analysis of prevalence, triggers, risk factors and the related socio-economic effects of childhood asthma in the Student Lung Health Survey (SLHS) database, Canada 1996. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2003;15:349–58. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2003.15.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spector SL. Common triggers of asthma. Postgrad Med. 1991;90:50–2. 55–9. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1991.11701032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Portnoy JM, Barnes CS, Kennedy K. Importance of mold allergy in asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2008;8:71–8. doi: 10.1007/s11882-008-0013-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mokdad AH, Stroup DF, Giles WH. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Team. Public health surveillance for behavioral risk factors in a changing environment. Recommendations from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Team. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-9):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Remington PL, Smith MY, Williamson DF, Anda RF, Gentry EM, Hogelin GC. Design, characteristics, and usefulness of state-based behavioral risk factor surveillance: 1981–87. Public Health Rep. 1988;103:366–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN: Version 2.0. Research Triangle Park (NC): Research Triangle Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niedoszytko M, Chelminska M, Jassem E, Czestochowska E. Association between sensitization to Aureobasidium pullulans (Pullularia sp) and severity of asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;98:153–6. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60688-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Douwes J, Pearce N. Invited commentary: is indoor mold exposure a risk factor for asthma? Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:203–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garrett MH, Rayment PR, Hooper MA, Abramson MJ, Hooper BM. Indoor airborne fungal spores, house dampness and associations with environmental factors and respiratory health in children. Clin Exp Allergy. 1998;28:459–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1998.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zureik M, Neukirch C, Leynaert B, Liard R, Bousquet J, Neukirch F. Sensitisation to airborne moulds and severity of asthma: cross sectional study from European Community Respiratory Health Survey. BMJ. 2002;325:411–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7361.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]