The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has concluded that an effective public health system must work collaboratively with the entire community, including political, legal, and governmental processes.1 Correspondingly, legal structures and the authority vested in health agencies and other partners within the public health system are quintessential to improving the public's health.2

Although federal and state public health laws have been extensively studied during the past 20 years, less attention has been directed to the broad range of local public health regulations in the United States. In view of the decentralized nature of public health law,3 local health entities (e.g., boards of health, city councils, or county councils) can be expected to have a significant impact on community health status,4 but existing scholarly work on local public health law has thus far largely focused on specific topics such as firearms,5 housing,6 or smoking regulations.7

More than 18,000 local jurisdictions (e.g., counties, cities, boroughs, and special districts) exist in the U.S., each of which may have some legal authority (albeit minimal in some cases) to regulate in the interests of protecting the public's health.8 Local conditions and problems often stimulate local governments to adopt and promulgate rules and ordinances to address the pressing health concerns of a given community. Some local health issues such as food handling are common across many local governments, but are handled differently depending on multiple factors, including rural or urban setting, population size, local governance, extent of home rule, and existence and powers of boards of health. Other health issues (e.g., physical activity,9 outside burning,10 and smoking11) are uniquely addressed at the local level in ways that contrast with federal or state approaches.

Local governments address public health issues through regulations based on the extent of authority bestowed by the state. “Home rule” statutes authorize local governments, depending on their size, class, and other factors, to directly address specific local public health issues through local laws.12 Forty-eight states have constitutional or statutory home-rule law.11 At times, local ordinances fill gaps in federal or state public health laws by addressing critical areas of public health concern not otherwise regulated.13 In some jurisdictions, innovative local public health legal approaches have “trickled up” to the state level as seen prominently in the areas of tobacco control14 and firearms.15 In other jurisdictions, where state law preempts local ordinances, local governments may be obligated to carry out state health regulations while adapting them to address local needs and priorities.16

FINDINGS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR LOCAL PUBLIC HEALTH POLICY AND PRACTICE

This installment of Law and the Public's Health reports on the initial findings of a project supported by The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation entitled “Building the Base for a Research Agenda on Local Public Health Authority.” Through this project, we seek to assess the major themes, legal approaches, and effectiveness of local law as a tool to improve public health. The ultimate goals are to (1) create a database of local public health ordinances in key program areas, (2) facilitate an understanding of relationships between local and state public health laws, and (3) establish a platform for future studies on local public health law.

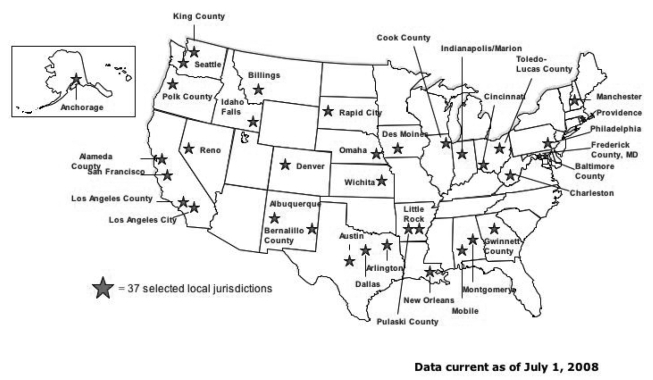

Our initial phase focused on understanding the scope and breadth of local ordinances. We researched ordinances of approximately 50 municipalities of various sizes and locations using online research engines, including Municode.com, Amlegal.com, LexisNexis, and other Web-based resources (e.g., city government websites). Based on our review of these municipalities' laws, we extrapolated common public health-related topics and themes under a broad conception of “public health” proffered by the IOM as “what we, as a society, do collectively to assure the conditions for people to be healthy.”1 From this initial review, we selected 37 geographically dispersed local jurisdictions with populations ranging from roughly 51,000 to 9.5 million for further study of the public health themes within their ordinances (Figure).

Figure.

Map of the U.S., 37 selected municipalities for local public health policy study

RESULTS

Recurrent public health topics in municipal ordinances

Based on extensive review of the 37 selected municipalities, we identified 22 public health topics that recurred to varying degrees in many municipal codes. These recurring health topics included: air quality, alcoholic beverages, animals, cemeteries and burials, childcare centers, communicable diseases, emergency medical services and ambulances, fair and affordable housing, firearms and dangerous weapons, food, garbage collection and disposal, housing and building codes, mass gatherings, massage establishments, noise, nuisances, pest control, sewer systems, smoking, swimming pools and spas, tobacco, and water wells.

The most predominant issues among these 22 public health topics regulated by the municipalities were garbage collection and disposal, animals, and sewer systems. Less frequently regulated topics included mass gatherings, fair and affordable housing, and water wells.

Scope of public health topics among municipal ordinances

For any particular public health topic, the scope, breadth, and content of ordinances vary widely across jurisdictions. The diversity of the scope of municipalities' ordinances is illustrated through their communicable disease control provisions, which 24% of the municipalities addressed in their codes. Billings, Montana, features three codes pertaining to communicable disease: quarantine, reporting, and cost.17 In contrast, Dallas, Texas, has 26 ordinances concerning the regulation of communicable disease.18 A Wichita, Kansas, ordinance simply specifies that state law governs communicable and infectious diseases.19

Local public health laws concerning the regulation of food exemplify the complexity of evaluating the ordinances across jurisdictions. Among the municipalities included in the study, 62% have ordinances regulating food. This category encompassed an array of topics that we grouped into five subcategories: (1) food handlers and distribution; (2) mobile food units; (3) restaurant licensing, inspections, and sanitation; (4) milk; and (5) meat. Providence, Rhode Island, features ordinances addressing four of the five categories (mobile food units; restaurant licensing, inspections, and sanitation; milk; and meat).20 Albuquerque, New Mexico, has ordinances pertaining to three of the five categories (mobile food units; restaurant licensing, inspections, and sanitation; and meat).21 Reno, Nevada, however, addresses only one topic (food handlers and distribution) through a single ordinance.22

Population size: a factor in public health issues addressed by municipal ordinances

To determine if population size correlates with municipalities' regulations on a specific health topic via an ordinance, we grouped jurisdictions according to size within three categories: (1) small = 22 municipalities with populations ≤500,000; (2) medium = eight municipalities with populations between 500,001 and 999,999; and (3) large = 10 municipalities with populations ≥1 million.

Among small jurisdictions, the most frequently regulated public health topics were garbage collection and disposal (with 86% of the municipalities regulating), followed by alcoholic beverages, animals, and sewer systems, each with 77% of the municipalities regulating. Among medium municipalities, the most predominant topics were nuisances and garbage collection and disposal, each with 100% of the municipalities, followed by noise and swimming pools and spas, each with 88% of the municipalities. The most frequently regulated topics by large municipalities were animals (100% of the municipalities), followed by garbage collection and disposal, noise, and tobacco, each with 85% of the municipalities.

We also researched the most commonly regulated public health topic among all three size categories. The topic of garbage collection and disposal was the most frequently regulated health topic, with 90% among the three population categories, followed closely by animals with 81%. By size categories, the municipalities regulating garbage collection and disposal were 86% of small municipalities, 88% of medium municipalities, and 85% of large municipalities, as noted previously. Concerning the topic of animals, the category numbers were 77% of small municipalities, 75% of medium municipalities, and 100% of large municipalities that regulate locally through their ordinances. The topic of noise was regulated by 76% of the municipalities. However, the percentages of municipalities regulating noise varied, from 54% of small municipalities to 88% of medium municipalities and 85% of large municipalities.

Alternatively, the least frequently regulated health topics had a wider variance of coverage among the population categories. For instance, 40% of small municipalities regulated childcare centers, but only 12% of medium and 14% of large municipalities regulated childcare centers. The same percentages existed among the categories under the topic of emergency medical services and ambulances. This suggests that less populated municipalities may regulate childcare centers and emergency medical services and ambulances more frequently than municipalities with larger populations (at least through their municipal codes).

Another health topic that showed variance among the population categories was firearms and dangerous weapons. Twenty-two percent of small municipalities regulated firearms and dangerous weapons, but 50% of medium and 57% of large municipalities directly regulated the same topic. This suggests that population size may be a contributing factor in public health topics regulated by municipal codes due to distinct needs of urban population centers.

Our initial results illustrate an array of common public health themes addressed across municipalities of varying size and location in the U.S. However, our existing review of municipal ordinances has not fully explored the content of these ordinances in great depth. In a forthcoming phase of this project, we plan to more completely characterize and describe the content of select ordinances to ascertain key differences and the reasons underlying these differences. We anticipate that detailed examination of the ordinances may reveal some additional similarities and differences in policy and regulatory approaches.

Authority of local public health departments to enforce municipal ordinances

Under basic principles of administrative law, the power to both set and enforce standards is dependent on the existence of a governmental entity with delegated legislative authority and the power to act. Thus, the nature and scope of enforceable municipal public health ordinances are related to the existence of local health departments or boards of health. Municipalities in our study assign public health-related authority to a variety of local governmental departments or agencies. Twenty (54%) of these municipalities have local health departments or boards of health. While the specific organization of local agencies has not been studied closely, 21 (57%) of the municipalities have separate local sanitation, environmental health, or environmental services departments. Cities without municipal health departments may fall within the jurisdiction of county or state health agencies.

Further research is needed to discern the degree to which responsibility for public health functions is assigned to additional agencies and departments, as well as to measure variation in approaches to delegating and exercising governmental powers and the potential advantages or disadvantages of specific organizational structures. Our future studies will characterize the degree to which various types of entities are empowered to create and enforce regulations concerning public health issues as distinct from ordinances passed by elected officials within a municipality.

DISCUSSION

Relationship of state and local public health laws

At this stage of our research, it is unclear whether local ordinances take up public health issues that state governments fail to address in an attempt to supplement state public health powers, or whether they represent acts of local governments that are independent of state influence. In the next phase of our study, we will attempt to address these and other questions by assessing the relationships between various municipal ordinances and corresponding state laws.11 We anticipate finding numerous instances in which local ordinances fill gaps in state public health law by addressing critical areas of public health concern not otherwise regulated, using a limited number of jurisdictions of various size and location for detailed analysis. For example, a court upheld a Columbus, Ohio, ordinance banning indoor smoking in restaurants, bars, and places of employment, because the state's no-smoking ban did not regulate smoking in those locations.23 Similarly, the Ohio Supreme Court upheld a Cincinnati, Ohio, ordinance limiting firearms possession.24 In both instances, municipal ordinances arguably filled gaps in existing state regulatory schemes.

State law may also preempt specific topics, requiring municipal governments to adhere to state mandates.8 For example, the Texas Supreme Court struck down a Dallas zoning ordinance targeting alcohol-related businesses because the ordinance was preempted by state law.25 In some instances, municipal regulations may mirror state statutes.8 Alternatively, municipal ordinances may differ in small but meaningful ways, adapting state statutes to address local needs and priorities.17 For example, a New Jersey court recently upheld a Hackettstown, New Jersey, ordinance regulating noise that was more restrictive than the state noise abatement law.26 Though subject to additional research and review, our initial results provide a platform for future assessment of major themes, legal approaches, and the effectiveness of local law as a tool to improve public health.

Implications for public health policy and practice

Local ordinances hold important implications for public health policies and practices impacting the daily lives of residents in communities, towns, cities, and counties across the U.S. To understand the effects and development of local policies and the legal landscape underlying these ordinances, we have initially examined public health ordinances in a wide spectrum of municipalities. The second phase of the project will analyze the relationship between local and state legislation, which is conjectured to strongly influence local legislation. Just as state courts construing state laws fill gaps through interpretation or develop responses to state-specific concerns, understanding municipalities' ordinances, the relationship between the state and local government, as well as the partnerships within state public health systems is key to developing a base for strengthening the quality of local public health laws and the utility of public health ordinances. Local public health advocates can use this information to enhance efforts to improve and protect the public's health.

Footnotes

This research was supported by The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation project # ID63386. The authors thank George (P.J.) Wakefield at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, for his editing and formatting assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine, Committee on Assuring the Health of the Public in the 21st Century. The future of the public's health in the 21st century. Washington: National Academies Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker EL, Potter MA, Jones DL, Mercer SL, Cioffi JP, Green LW, et al. The public health infrastructure and our nation's health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:303–18. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gostin LO. Public health law reform. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1365–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanarek N, Stanley J, Bialek R. Local public health agency performance and community health status. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2006;12:522–7. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200611000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Carroll PW, Loftin C, Waller JB, Jr, McDowall D, Bukoff A, Scott RO, et al. Preventing homicide: an evaluation of the efficacy of a Detroit gun ordinance. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:576–81. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.5.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winslow C-EA, Twichell AA, Allen RH, Ascher CS, Marquette B, McDougal MS, et al. The improvement of local housing regulations under the law: an exploration of essential principles. Am J Public Health. 1942;32:1263–77. doi: 10.2105/ajph.32.11.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moskowitz JM, Lin Z, Hudes ES. The impact of workplace smoking ordinances in California on smoking cessation. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:757–61. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.5.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diller P. Intrastate preemption. Boston University Law Rev. 2007;87:1113–76. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Librett JJ, Yore MM, Schmid TL. Local ordinances that promote physical activity: a survey of municipal policies. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1399–403. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burning ordinance. Huntingdon, Pennsylvania. [cited 2008 Dec 30]. Available from: URL: http://www.township.north-huntingdon.pa.us/local_ordinances.htm.

- 11.Barron DJ. Reclaiming home rule. Harvard Law Rev. 2003;116:2255–386. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grad FP. The public health law manual. Washington: American Public Health Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Handler AS, Turnock BJ. Local health department effectiveness in addressing the core functions of public health: essential ingredients. J Public Health Policy. 1996;17:460–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novotny TE, Romano RA, Davis RM, Mills SL. The public health practice of tobacco control: lessons learned and directions for the states in the 1990s. Annu Rev Public Health. 1992;13:287–318. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.13.050192.001443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vernick JS, Teret SP. New courtroom strategies regarding firearms: tort litigation against firearm manufacturers and constitutional challenges to gun laws. Houston Law Rev. 1999;36:1713–54. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorovitz E, Mosher J, Pertschuk M. Preemption or prevention?: lessons from efforts to control firearms, alcohol, and tobacco. J Public Health Policy. 1998;19:36–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Billings, Montana, communicable diseases code. Ch. 15, art. 15-200, §§15-201 to 203.

- 18.Dallas, Texas, health and sanitation code. Vol. 1 ch. 19, art. IV and IVA. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wichita, Kansas, code. Title 7, ch. 7.04, §7.04.070.

- 20.Providence, Rhode Island, food and food products code. Ch. 10, art. II, §10-30; art. III; art. V.

- 21.Albuquerque, New Mexico, health, safety, and sanitation code. Ch. 9, art. 6, pt. 1–5.

- 22.Reno, Nevada, health and sanitation code. Part 2, title 10, ch. 10.06.

- 23.Traditions Tavern v. City of Columbus. 870 N.E.2d 1197 (Ohio Ct. App. 2006)

- 24. City of Cincinnati v. Baskin, 859 N.E.2d 514 (Ohio 2005)

- 25. Dallas Merchant's and Concessionaire's Association v. City of Dallas, 852 S.W.2d 489 (Texas 1993)

- 26. New Jersey v. Krause, 945 A.2d 116 (N.J. Super. 2008)