Abstract

The present study determined the effect of maternal nicotine exposure during the early developmental period on AT1R and AT2R mRNA and protein abundance in the rat brain. Pregnant rats of day-4 gestation were implanted with osmotic minipumps that delivered nicotine at a dose rate of 6 mg/kg/day for 28 days. Neither fetal nor offspring brain weight was significantly altered by the nicotine treatment. Nicotine significantly increased brain AT1R in fetuses at gestation 15 and 21 days and decreased central AT2R at gestation day 21. In the offspring, perinatal nicotine significantly increased brain AT1R protein in males but not females at 30 days, and increased it in both males and females at 5-month-old. AT2R protein levels were significantly decreased by nicotine in both male and female offspring regardless of ages. Whereas brain AT1R mRNA abundance did not change during postnatal development, AT2R mRNA levels in both sexes significantly decreased in 5-month-old, as compared with 30-day-old offspring. Nicotine significantly increased brain AT1R mRNA in the female offspring. In contrast, it decreased AT2R mRNA in the brain to the same extent in males and females. In control offspring, there was a developmental increase in the AT1R/AT2R mRNA ratio in the brain of adult animals, which was significantly up-regulated in nicotine-treated animals with females being more prominent than males. The results demonstrate that perinatal nicotine exposure alters AT1R and AT2R gene expression pattern in the developing brain and suggest maternal smoking-mediated pathophysiological consequences related to brain RAS development in postnatal life.

Keywords: Nicotine, Brain, AT1/AT2 ratio, Fetus, Offspring

1. Introduction

Cigarette smoking and nicotine exposure during pregnancy is one of important environmental insults that cause fetal growth restriction in humans as well as in experimental animals (Mochizuki et al., 1985; Slotkin, 1998; Winzer-Serhan, 2008). Nicotine as a principal psychoactive component in tobacco can penetrate through the placental barrier, concentrate in fetal tissues (Ankarberg et al., 2001; Dempsey and Benowitz, 2001), and affect fetal growth, including fetal brain development.

The brain has its own local renin-angiotensin system (RAS) that plays a key role in the regulation of cardiovascular responses, body fluid homeostasis, and neuroendocrine function (Fitzsimons, 1998; Paul et al., 2006). Angiotensin II (Ang II) is the most active peptide in physiological function of the RAS through acting on the two major subtypes of Ang II receptors, AT1R and AT2R, in the brain (Kottenberg-Assenmacher et al., 2008; Fitzsimons, 1998). Previous studies have demonstrated that exposure to nicotine during the early developmental period affects expression of nicotinic and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain, and induces behavioral changes as well as learning performance (Ankarberg et al., 2001; Falk et al., 2005). In addition, adverse intrauterine environment, including maternal malnutrition and exposure to drugs or chemicals, can affect expression of AT1R and AT2R in the peripheral organs, tissues, or systems in the fetus at late gestation (Dodic et al., 2001, 2002). However, it is unknown whether and to what extent nicotine administration in maternal animal during prenatal and early postnatal stages can alter AT1R and AT2R expression pattern in the brain. Therefore, in the present study, we determined the effect of exposure of maternal nicotine during the early developmental periods on AT1R and AT2R mRNA and protein abundance in the brain of both fetuses and offspring in rats. Given that previous studies have shown gender-differences in fetal programming of adult disease (Woods, 2007; Bae et al., 2005; do Carmo Pinho Franco et al., 2003), both male and female offspring were included in the experiments.

2. Results

2.1. Brain weight

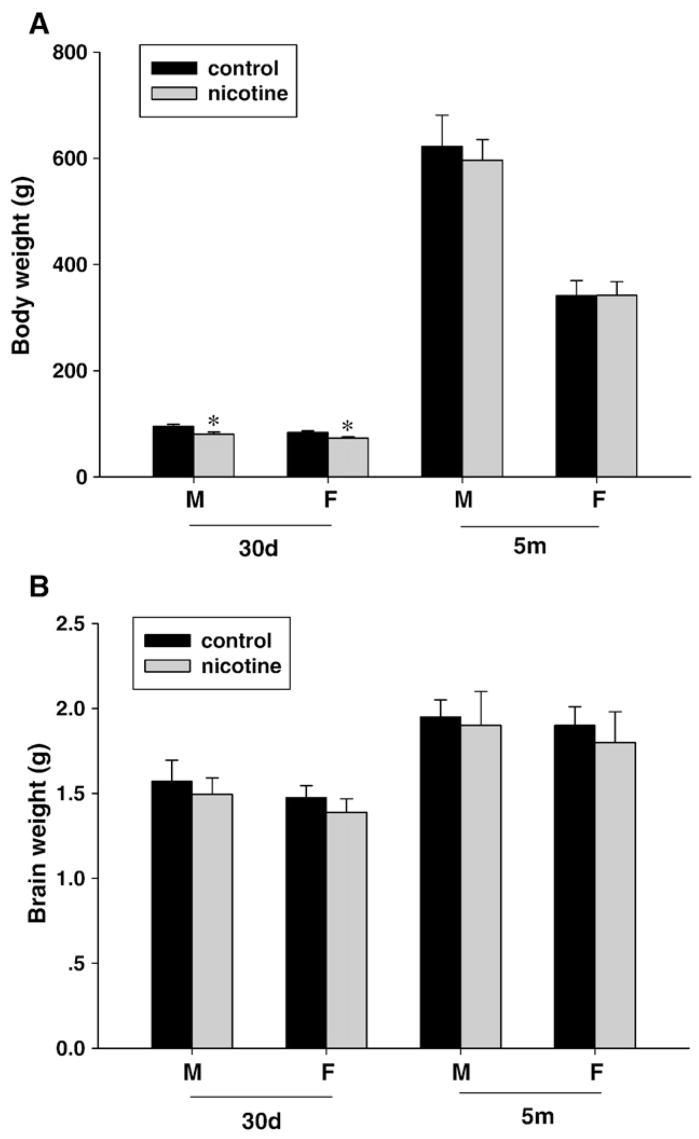

Maternal exposure to nicotine during pregnancy and lactation had no effect on brain weight of offspring at ages of 30-day-old and 5-month-old, regardless of sex (Fig. 1). Although body weight of both male and female offspring at 30-day-old was significantly lower in nicotine-treated animals than those of control, there was no significant difference in body weight in either male or female offspring at 5-month-old between control and nicotine-treated animals (P>0.05) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of maternal nicotine administration on body (A) and brain (B) weight in the offspring at 30-day-old (30d) and 5-month-old (5m). m: male; f: female. *P<0.01, nicotine treatment vs. control.

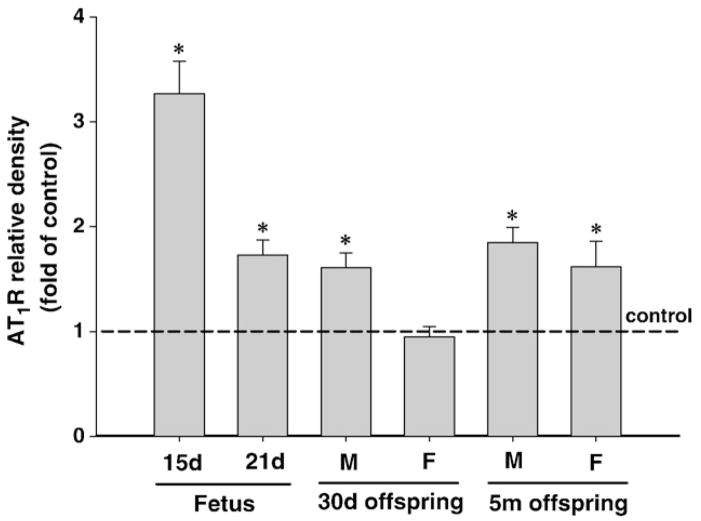

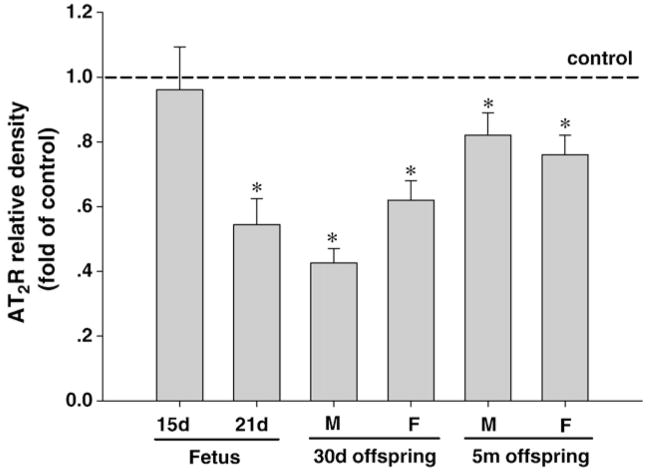

2.2. Brain AT1R and AT2R protein

Maternal nicotine administration significantly increased AT1R protein abundance in the fetal brain at 15-day and 21-day of gestation (Fig. 2). However, there was a significant reduction in the extent of nicotine-induced increase in AT1R in 21-day fetal brain as compared with that of 15-day brain (Fig. 2). In contrast to AT1R, nicotine had no effect on AT2R protein abundance in 15-day fetal brain, but significantly decreased it in 21-day fetal brain (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Effect of maternal nicotine administration on brain AT1R protein abundance in the fetus and offspring. GD 15, GD 30: gestation day 15, 30. 30d: 30-day-old, 5m: 5-month-old. M: male; F: female. *P<0.05, nicotine treatment vs. control.

Fig. 3.

Effect of maternal nicotine administration on brain AT2R protein abundance in the fetus and offspring. GD 15, GD 30: gestation day 15, 30. 30d: 30-day-old, 5m: 5-month-old. M: male; F: female. *P<0.05, nicotine treatment vs. control.

In male offspring, perinatal nicotine exposure caused a significant increase of AT1R protein abundance in the brain to the same extent at 30-day-old and 5-month-old, which was not significantly different from that seen in 21-day fetal brain (Fig. 2). In females, nicotine had no effect on AT1R at 30-day-old but increased it at 5-month-old to the similar extent seen in male offspring (Fig. 2). Unlike AT1R, perinatal nicotine exposure resulted in significant decreases in AT2R protein abundance in the brain of offspring at both 30-day-old and 5-month old (Fig. 3). Whereas no significant sex dichotomy was observed in the nicotine’s effects, it appears there was a partial recovery of nicotine’s effect on AT2R in male offspring during postnatal development (Fig. 3).

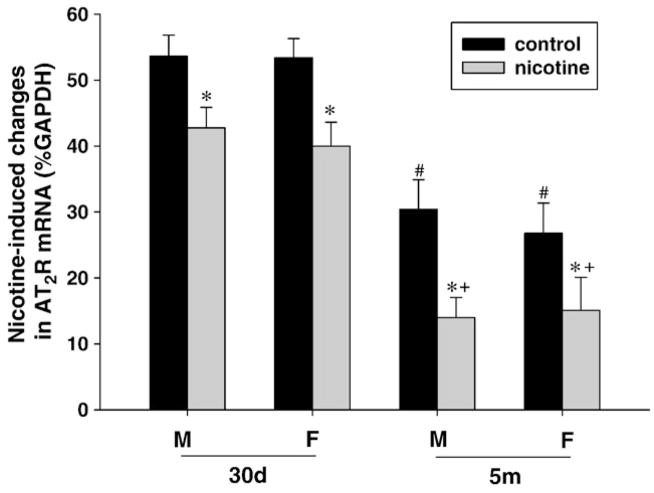

2.3. Brain AT1R and AT2R mRNA levels

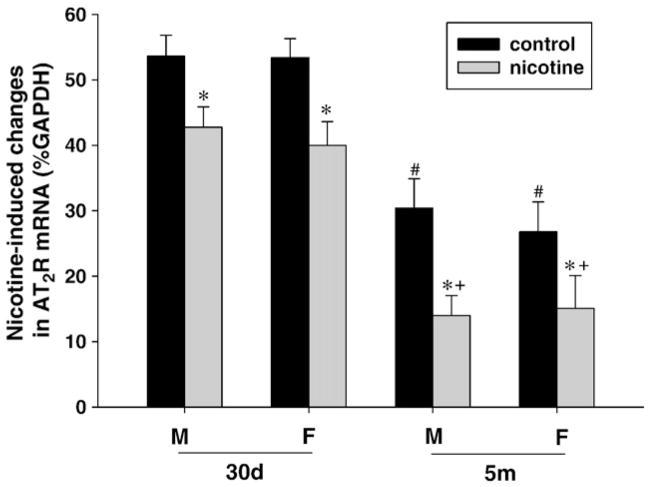

In control animals, brain AT1R mRNA levels were not significantly changed during postnatal development in either male or female offspring (Fig. 4). Perinatal nicotine exposure caused a significant increase in AT1R mRNA in the brain of both male and female offspring with the effect on females being more prominent (Fig. 4). Additionally, the effect of nicotine on brain AT1R mRNA was further increased at 5-month-old as compared with 30-day-old offspring, regardless of sex (Fig. 4). Unlike AT1R mRNA, brain AT2R mRNA of both male and female offspring showed a significant decrease during postnatal development in control animals (Fig. 5). In contrast to the finding with AT1R mRNA, perinatal nicotine exposure resulted in a significant decrease in AT2R mRNA abundance in the brain of both male and female offspring (Fig. 5). Whereas no sex dimorphism was observed in the nicotine’s effect, postnatal development significantly increased the extent of nicotine-induced decrease in AT2R mRNA in the brain in both sexes (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Effect of maternal nicotine administration on brain AT1R mRNA levels in the offspring at 30-day-old (30d) and 5-month-old (5m). M: male; F: female. *P<0.05, nicotine treatment vs. control; +P<0.01, male vs. female in nicotine treated groups; #P<0.05, 30d vs. 5m in nicotine treated groups.

Fig. 5.

Effect of maternal nicotine administration on brain AT2R mRNA levels in the offspring at 30-day-old (30d) and 5-month-old (5m). M: male; F: female. *P<0.05, nicotine treatment vs. control; +P<0.05, 30d vs. 5m in nicotine treated groups; #P<0.05, 30d vs. 5m in the control groups.

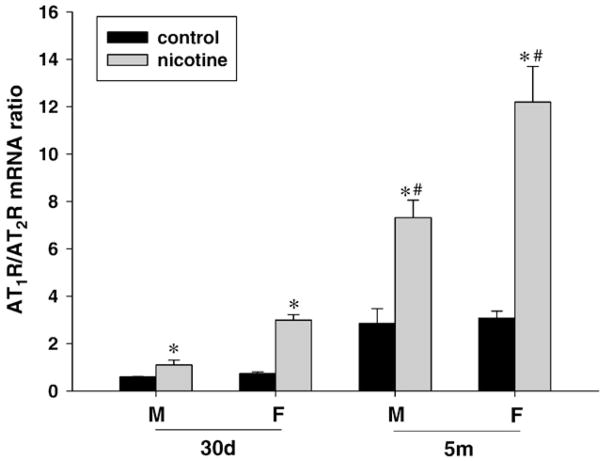

Fig. 6 shows the AT1R/AT2R mRNA ratio in the brain of control and nicotine-treated offspring. In control animals, there was a significant increase in the AT1R/AT2R mRNA ratio in the brain at 5-month-old as compared with 30-day-old offspring in both males and females. Nicotine treatment significantly increased the AT1R/AT2R mRNA ratio and the higher effect was observed in females. Additionally, the effect of nicotine was further increased at 5-month-old as compared with 30-day-old offspring, regardless of sex.

Fig. 6.

Effect of maternal nicotine administration on brain AT1R/AT2R mRNA ratio in the offspring at 30-day-old (30d) and 5-month-old (5m). M: male; F: female. *P<0.01, nicotine treatment vs. control. #P<0.01, 30d vs. 5m in nicotine treated groups.

3. Discussion

The present study demonstrated that exposure to nicotine during pregnancy altered expression of brain Ang II receptors in the fetus, and perinatal nicotine increased AT1R, and decreased AT2R in the brain of the offspring. These findings provide new information that exposure to maternal smoking or nicotine at the early developmental stage could remodel development of the central receptors of the RAS.

In the control offspring, the brain/body weight ratio was reduced from 30-day-old to 5-month-old, the brain/body weight ratio was not changed between the control and nicotine treated groups, which agrees with previous studies (Lv et al., 2008; Mann et al., 1988). Although the brain weight was not significantly changed by perinatal exposure to nicotine, the body weight of the offspring at 30 days after birth was significantly reduced compared to the control, indicating fetal growth restriction during the early development, and which was consistent with others’ and our previous studies in the fetus (Slotkin, 1998; Lawrence et al., 2008; Mochizuki et al, 1985; Winzer-Serhan, 2008; Bassi et al., 1984; Lv et al., 2008; Mao et al., 2008a). Notably, 5 months after birth, the body weight of the offspring exposed to perinatal nicotine was the same as that of the control, demonstrating a catch-up growth (Thureen, 2007; Lévy-Marchal and Czernichow, 2006). The results suggest that catch up growth mainly occurred after neonate period in the offspring exposed to perinatal nicotine.

Despite this is a novel finding that prenatal nicotine could alter expression of both AT1R and AT2R in the fetal brain at different gestational time, a question raised immediately was if there would be any long-term consequence for the change of the fetal RAS during the early developmental stage, or, would further development after birth or catch-up growth after neonate period be helpful to correct the altered AT1R or AT2R in the brain of the young rats? In the present study, we showed that the altered expression of the brain Ang II receptors not only in the 30-day-old, but also in the 5-month-old adult offspring. In general, AT1R increase, and AT2R decrease in the body, are time-dependent during development around birth (Fitzsimons, 1998). Prenatal nicotine significantly enhanced AT1R protein, not AT2R, in the fetal brain at gestational age 15 days, and the highest increase of AT1R protein was detected at 66% gestation. Moderate increase of AT1R protein was observed from gestational day 21 to 5-month-old with exception for the female at 30-day-old. However, brain AT2R protein was markedly reduced from gestation day 21 to 5-month-old regardless of sex. The results provide new information in several lines: First, the brain AT1R during in utero development is relatively sensitive to environmental factors such as exposure to nicotine since the changes of this subtype appeared early; Second, following the highest increase of AT1R at gestation day 15, the moderate increase at similar levels from gestation day 21 to adult stage could mean that the effect of nicotine impacted more on fetal life, and/or there may be adaptation to nicotine effects from the term during development; Third, there was gender difference for AT1R, not AT2R protein expression affected by perinatal nicotine at translational level.

Analysis demonstrated that brain AT1R mRNA in the offspring brain remained unchanged from the age of 30-day-old, while AT2R mRNA expression was significantly reduced in the control. This developmental pattern is consistent with previous report (Fitzsimons, 1998). Previous studies reported that the RAS plays an important role in physiological functions (Fitzsimons, 1998; Paul et al., 2006). Recent progress has been made to demonstrate that the development of the RAS could be affected by multiple factors during pregnancy. For instance, dexamethasone administered in pregnancy could increase the levels of fetal AT1R and AT2R mRNA in late gestation in sheep (Dodic et al., 2001, 2002). The changes of Ang II receptors during early development could influence postnatal life. In determination of environmental effects on the development of the brain RAS, the present study was the first to find that perinatal nicotine affects the expression of central Ang II receptors. Our new data suggest that maternal smoking or exposure to nicotine could affect the development of brain Ang II receptors, and that influence persisted into adult life. Considering that both mRNA and protein of AT2R were changed in the brain of the offspring, the effect of exposure to nicotine during the early developmental period on central AT2R may be at its transcriptional and translational level. In comparison, AT1R mRNA, not protein, was all changed at both neonate and adult stages, nicotine effects could be mainly at transcriptional level on AT1R.

Notably, a significant increase of AT1R/AT2R mRNA ratio in the offspring was noted in the present study. A number of studies have shown that central physiological and pathophysiological actions of Ang II mainly depend on AT1R (Fitzsimons, 1998; Paul et al., 2006), and balance between AT1R and AT2R can influence health and diseases (Siragy et al., 2007; Siragy and Xue, 2008). An absolute increase of brain AT1R, and decrease of AT2R, were noted at transcriptional and translational level. Since the ratio of AT1R/AT2R mRNA also was increased in the offspring with perinatal history of exposure to nicotine, this caused a relatively further increase of AT1R in the brain. In the present study, the increase of AT1R mRNA, and decrease of AT2R mRNA, at 5-month-old were higher than that at 30-day-old, indicating an age difference for nicotine effects in fetal origins. This also can explain the age difference of AT1R/AT2R mRNA ratio between the neonate and adult. Whether those absolute or relative increase of brain AT1R and decrease of AT2R contribute to diseases need further studies.

AT1R/AT2R mRNA ratio was greater in the female than that of the male offspring in the nicotine treated groups. Although both increase of AT1R mRNA and decrease of AT2R mRNA contributed to a higher ratio in the female, the former was critical to the higher ratio in the present study. Previous studies demonstrated the gender dimorphism in fetal programming of adult diseases (Woods, 2007; Bae et al., 2005; do Carmo Pinho Franco et al., 2003). For example, malnutrition and administration of glucocorticoid could reduce nephron numbers in the kidney in male offspring in a gender-dependent manner (McMullen and Langly-Evans, 2005; Woods et al., 2005). In the present study, the female offspring showed greater increase of brain AT1R mRNA than that of the male, although its protein expression under condition of nicotine treatment was relatively suppressed compared to the male. This suppression was observed in 30-day-old neonate rats, not 5-month-old adults. Thus, hormonal causes could be a reasonable explanation for the change and gender difference at translational level. However, transcriptional alterations in AT1R mRNA may be linked to sex difference at original cellular or molecular factors that contribute to the gender difference at gene level in response to the perinatal nicotine. This also opens new opportunities for further studies. In addition, the present study focused on influence of perinatal exposure to nicotine on development of brain AT1R and AT2R at different ages. The results warrant further studies of AT1aR and AT1bR at specific brain regions in future.

In conclusion, in spite of catch-up growth in the offspring following perinatal exposure to nicotine, the altered Ang II receptors in the brain were not corrected in the catch-up growth. Notably, exposure to nicotine affected brain AT1R/AT2R not only at fetal stage, the changed expression of Ang II receptors also was found in the brain of the adult offspring. To our knowledge, this was the first report to show that perinatal exposure to nicotine affected the RAS development in the fetal brain, and remodeled AT1R/AT2R expression and its ratio in the offspring brain. Considering that the central RAS also plays an important role in physiological and pathophysiological regulations in the body, the findings in the present study provide new information for RAS-mediated mechanisms in the control of physiological functions and disease development in prenatal and postnatal life. These findings also open new opportunities for further investigation of local RAS and its subtypes of receptors at special areas or pathways in the brain related to clinical and experimental diseases.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Animals and experiments

Pregnant Sprague–Dawley rats were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Portage, MI). Nicotine was administrated through osmotic minipumps implanted subcutaneously as described previously (Xiao et al., 2008; Mao et al., 2008b). On the fourth day of pregnancy, rats were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine and an incision was made on the back to insert osmotic minipumps (Type 2ML4, Alza Corp., Palo Alto, CA). The incision was closed with sutures. Half of pregnant rats were implanted with the minipumps containing nicotine at a concentration of 102 mg/ml, and the other half were implanted with the minipumps containing 0.9% NaCl, served as the control. The flow rate of the minipumps was 60 μl/day, which delivered a dose of 2.1 mg nicotine per day. In rats of 350 g body weight, this corresponds to a dose rate of 6 mg/kg/day, which closely resembles those occurring in moderate to heavy human smokers (Slotkin 1998; Lichtensteiger et al., 1988). The delivery period for the pumps is 28-day, and thus nicotine delivery continued after birth until postnatal day 10.

Some pregnant rats of control and nicotine-treated groups (n=5 litters, each group) were killed at gestation days 15 and 21, respectively, and fetal brains were removed immediately. Other animals were allowed to give birth naturally. As previously reported (Xiao et al., 2007) the nicotine treatment did not affect the litter size and the length of gestation, and all of the pregnancies reached their full term. Pups born to the dams were kept with their mothers until weaning, after which male and female pups were separated and transferred to cages where they were housed in groups of two. Male and female offspring were killed at ages of 30-day-old and 5-month-old, respectively, and the brains were removed immediately. Brain and body weights were obtained. All procedures and protocols used in the present study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees and followed the guidelines by the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory.

4.2. Western immunoblotting

Brains were homogenized in a lysis buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl, 10 mM EDTA, 0.1% Tween-20, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, and 5 μg/ml aprotinin, pH 7.4. Homogenates were ultrasonicated in ice and then centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min at 10,000 g. Supernatants were collected and protein was determined using a protein assay kit from Bio-Rad. Samples with equal protein were loaded and separated on 10% SDS-PAGE. The membranes were treated with a Tris-buffered saline solution containing 5% dry-milk on a gentle shaker for 1 h, followed by incubation with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against AT1R or AT2R (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Santa Cruz, CA) overnight at 4 °C. Then membranes were incubated with a secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody. Proteins were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence reagents, and blots were exposed to Hyperfilm. GAPDH (the primary antibody from Millipore, working concentration: 1:1000) was blotted in the same membrane as an internal control for normalizing the relative density. Results were analyzed and quantified with the Kodak electrophoresis documentation and analysis system and Kodak ID image analysis software.

4.3. Real-time RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from the brain using TRIzol reagents (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA). PCR was performed in triplicate. mRNA abundance of AT1R and AT2R was determined by real-time RT-PCR using Icycler Thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The primer sequences for rat AT1R are: forward 5′-CGGCCTTCGGATAACATGA-3′, and reverse 5′-CCTGTCACTCCACCTCAAAACA-3′; and for rat AT2R: forward 5′-CAATCTGGCTGTGGCTGACTT-3′, and reverse 5′-TGCACATCACAGGTCCAAAGA-3′. Real-time RT-PCR was performed in a final volume of 25 μl. Each PCR reaction mixture consisted of 600 nM of primers, 33 U of M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI), and iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) containing 0.625 U Taq polymerase, 400 μM each of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP, 100 mM KCl, 16.6 mM ammonium sulfate, 40 mM Tris–HCl, 6 mM MgSO4, SYBR Green I, 20 nM fluoresein and stabilizers. RT-PCR was performed under the following conditions: 42 °C for 30 min, 95 °C for 15 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 20 s, 52 °C for 1 min. GAPDH was used as an internal reference and serial dilutions of the positive control were performed on each plate to create a standard curve. The amount of target gene was normalized to the reference GAPDH to obtain the relative threshold cycle.

4.4. Statistics

Data were expressed as means±SEM. Statistical significance (P<0.05) was determined using repeated measures of ANOVA and post-hoc test (Tukey’s test).

Acknowledgments

C. Mao and H. Zhang contributed equally to this work. This work was supported in part by National Natural Science Foundation (No: 30570915, No: 30871400), Jiangsu Natural Science Key Grant (BK2006703), Jiangsu High Education NSF (08KJB320013), Suzhou Key Lab Grant (SZS0602), Suda Program Project Grant (No. 90134602), Suzhou International Cooperation Grant (N2134703), Suda Medical Key Grant (EE134704), and US National Institutes of Health grants HL82779 (LZ) and HL83966 (LZ).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues.

Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited.

In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright

References

- Ankarberg E, Fredriksson A, Eriksson P. Neurobehavioral defects in adult mice neonatally exposed to nicotine: changes in nicotine-induced behavior and maze learning performance. Behav Brain Res. 2001;123:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00207-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae S, Gilbert RD, Ducsay CA, Zhang LB. Prenatal cocaine exposure increases heart susceptibility to ischemia/reperfusion injury in adult male but not female rats. J Physiol. 2005;565:149–158. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.082701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi JA, Rosso P, Moessinger AC. Fetal growth retardation due to maternal tobacco smoke exposure in the rat. Pediatr Res. 1984;18:127–130. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198402000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey DA, Benowitz NL. Risks and benefits of nicotine to aid smoking cessation in pregnancy. Drug Saf. 2001;24:277–322. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200124040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- do Carmo Pinho Franco M, Nigro D, Fortes ZB, Tostes RCA, Carvalho MHC, Lucas SRR. Intrauterine undernutrition —renal and vascular origin of hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:228–234. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00541-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodic M, Baird R, Hantzis V. Organs/systems potentially involved in one model of programmed hypertension in sheep. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2001;28:952–956. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2001.03556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodic M, Abouantou T, O’Connor A. Programming effects of short prenatal exposure to dexamethasone in sheep. Hypertension. 2002;40:729–734. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000036455.62159.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk L, Nordberg A, Seiger Å, Kjældgaard A, Hellström-Lindahl E. Smoking during early pregnancy affects the expression pattern of both nicotinic and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in human first trimester brainstem and cerebellum. Neuroscience. 2005;132:389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons JT. Angiotensin, thirst, and sodium appetite. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:583–686. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.3.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottenberg-Assenmacher E, Massoudy P, Jakob H, Philipp T, Peters J. Chronic AT1-receptor blockade does not alter cerebral oxygen supply/demand ratio during cardiopulmonary bypass in hypertensive patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52(1):73–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence J, Xiao DL, Xue Q, Zhang LB. Prenatal nicotine exposure increases heart susceptibility to ischemia/reperfusion injury in adult offspring. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:331–341. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.132175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévy-Marchal C, Czernichow P. Small for gestational age and the metabolic syndrome: which mechanism is suggested by epidemiological and clinical studies? Horm Res. 2006;65:123–130. doi: 10.1159/000091517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtensteiger W, Ribary U, Schlumpf M. Prenatal adverse effects of nicotine on the developing brain. Prog Brain Res. 1988;73:137–157. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)60502-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv JX, Mao CP, Zhu LY, Zhang H, Hui PP, Xu FC, Liu YJ, Zhang LB, Xu ZC. The effect of prenatal nicotine on expression of nicotine receptor subunits in the fetal brain. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29:722–726. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann MD, Glickman SE, Towe AL. Brain/body relations among myomorph rodents. Brain Behav Evol. 1988;31:111–124. doi: 10.1159/000116579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao CP, Yuan X, Lv JX, Xu ZC. Prenatal exposure to nicotine with associated in utero hypoxia decreased fetal brain muscarinic mRNA in the rat. Brain Res. 2008a;1189:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao CP, Yuan X, Zhang H, Lv JX, Guan JC, Miao LY, Chen LQ, Zhang YY, Zhang LB, Xu ZC. The effect of prenatal nicotine on mRNA of central cholinergic markers and hematological parameters in rat fetuses. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2008b;26(5):467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen S, Langly-Evans SC. Sex-specific effects of prenatal low-protein and carbenoxolone exposure on renal angiotensin receptor expression in rats. Hypertension. 2005;46:1374–1380. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000188702.96256.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki M, Maruo T, Masuko K. Mechanism of foetal growth retardation caused by smoking during pregnancy. Acta Physiol Hung. 1985;65:295–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul M, Mehr AP, Kreutz R. Physiology of local renin-angiotensin systems. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:747–803. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siragy HM, Xue C. Local renal aldosterone production induces inflammation and matrix formation in kidneys of diabetic rats. Exp Physiol. 2008:22. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.042085. Electronic publication ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siragy HM, Inagami T, Carey RM. NO and cGMP mediate angiotensin AT2 receptor-induced renal renin inhibition in young rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R1461–R1467. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00014.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA. Fetal nicotine or cocaine exposure: which one is worse? Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:931–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thureen PJ. The neonatologist’s dilemma: catch-up growth or beneficial undernutrition in very low birth weight infants—what are optimal growth rates? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:S152–S154. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000302962.08794.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzer-Serhan UH. Long-term consequences of maternal smoking and developmental chronic nicotine exposure. Front Biosci. 2008;13:636–649. doi: 10.2741/2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods LL. Maternal nutrition and predisposition to later kidney disease. Curr Drug Targets. 2007;8(8):906–913. doi: 10.2174/138945007781386875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods LL, Ingelfinger JR, Rasch R. Modest maternal protein restriction fails to program adult hypertension in female rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R1131–R1136. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00037.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao DL, Huang XH, Lawrence J, Zhang LB. Fetal and neonatal nicotine exposure differentially regulates vascular contractility in adult male and female offspring. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:654–661. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.113332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao DL, Xu ZC, Huang XH, Zhang LB. Prenatal gender-related nicotine exposure increases blood pressure response to angiotensin II in adult offspring. Hypertension. 2008;51:1239–1247. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.106203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]