Introduction

Proteins are interfacially active molecules; a statement that is demonstrated easily by the spontaneous accumulation of proteins at interfaces.1–4 Why do proteins show the propensity to adsorb to interfaces and why do they adsorb so tenaciously? For some proteins, the tendency to adsorb is due to the nature of side chains present on the surface of the protein. Protein is an amphoteric polyelectrolyte.5 Its amino acids have different characteristics: some are apolar and like to be buried inside the protein globule, whereas others are polar and charged and are often found on the outside protein surface. A strong, long-ranged electrostatic attraction between a charged adsorbent and oppositely charged amino acid side chains will lead to a significant free energy change favoring the adsorption process. In other cases, the interfacial activity of the protein may be driven by its marginal structural stability.6 The compactness of the native structure of the protein is due to the optimal amount of apolar amino acid residues. The stability of such a structure depends on the combination of hydrophobic interactions between the hydrophobic side chains, hydrogen bonds between the neighboring side chains and along the polypeptide chains, and the Coulomb interactions between charged residues and van der Waals interactions. An adsorbent surface can “compete” for the same interactions and minimize the total free energy of the system by unfolding the protein structure: the adsorption process may result in a surface-induced protein denaturation.7,8 Elements of the secondary structure of the protein (α helix and β sheet) together with the supersecondary motifs form a compact globular domain. Some proteins are built from more than one domain. In a multidomain protein, it is possible that one domain will dominate the adsorption property of the whole macromolecule at a particular type of interface. For example, acid-pretreated antibodies bind with their constant fragments to a hydrophobic surface.9

In order to completely characterize and predict protein adsorption, one would like to have a quantitative description of adsorption. This description is typically obtained by measuring the adsorption isotherm, adsorption and desorption kinetics, conformation of adsorbed proteins, number and character of protein segments in contact with the surface, and other physical parameters related to the adsorbed protein layer, such as layer thickness and refractive index. This article describes a selected set of techniques and protocols that will provide answers about the mechanism of protein adsorption onto and desorption from surfaces. The reader is referred to the specialized monographs1–4 and a review 10 on protein adsorption for a more comprehensive coverage of various aspects of protein–surface interactions.

Description of Protein Adsorption

A. Adsorption Isotherms

The adsorption isotherm is a function that relates the measured adsorbed amount of a protein (per unit area), Γp, to the solution concentration of protein, cp. Typically, Γp increases sharply at low solution concentrations of protein and levels off at higher protein concentrations approaching a limiting Γp value. The existence of a Γp adsorption “plateau” has been interpreted as a sign that the adsorbing surface is “saturated” with protein molecules; any further increase in the solution protein concentration typically does not affect Γp. The amount of adsorbed protein at the “plateau” of the adsorption isotherm is often close to the amount that can fit into a closed-packed monolayer; hence, the notion of a saturating monolayer coverage is often applied to protein adsorption.

Under ideal conditions, the shape of the adsorption isotherm can provide information about the affinity between protein and surface. The evaluation of the affinity, however, does require a model for the protein–surface interactions; a model from which the adsorption isotherm function, Γp(cp), can be derived and compared with the experimental results. Most experimentally measured protein adsorption isotherms may not be the true equilibrium isotherms.1,2,11 It may take a relatively long time for a protein adsorbing to a surface to reach true equilibrium. Other processes, such as protein conformational change, may run concurrently with the adsorption process and affect the adsorbed amount. Hence, the information contained in the adsorption isotherm may not refer to identical molecules. The existence of several protein conformers in solution, each with slightly different adsorptivity, may result in an isotherm that will reflect the competition between conformers for a limited adsorption surface area.

1. Adsorption to Two-Dimensional Lattice of Binding Sites

It has been shown that a protein molecule adsorbing to a solid surface with immobilized alkyl residues will bind multivalently to several residues at the same time.12,13 The contact points with alkyl residues can be considered as individual binding sites situated in either a homogeneous or a heterogeneous two-dimensional lattice.14 In principle, therefore, the amount of adsorbed protein under standard conditions also depends on the surface concentration of binding sites on the solid phase. On the basis of multivalence, which implies a specific geometry of sites, protein adsorption on such tailor-made lattices has been compared to a molecular recognition process.15

Terminologically, just as a coenzyme is viewed as being a small entity, i.e., a ligand in binding to a macromolecular enzyme, a protein can be similarly viewed as being a small entity, i.e., a ligand in comparison to the large macroscopic solid surface it is being adsorbed to. For simplicity, therefore, protein molecules in protein adsorption studies (adsorbates) have been defined as ligands,12,16

To account for the two fundamental parameters governing protein adsorption on natural and artificial surfaces, one may distinguish two categories of protein adsorption isotherms: (a) a lattice site binding function and (b) a bulk ligand binding function.15,17,18 Equations describing these binding functions have been derived previously and are similar power functions as is the Hill equation.17,18

The lattice site binding function governs the binding of an immobilized residue, constituting a surface lattice site, to a complementary site (patch, pocket) on the protein adsorbed from the bulk solution. The more lattice sites that interact simultaneously with a protein molecule, the higher the affinity of binding will be.19 Protein adsorption, therefore, increases as a function of the surface concentration of lattice sites (at a constant equilibrium concentration of free bulk protein) according to Eq.(1)12,13,17:

| (1) |

where θs is the fractional saturation of binding units with protein on the adsorbent as a function of the surface concentration of lattice sites in a binding unit. ΓsRes is the surface concentration of lattice sites (i.e., immobilized residues), KS is the lattice site adsorption constant, and ns is the lattice site adsorption coefficient. For the case ns = 1, Eq. (1) reduces to a rectangular hyperbola. Saturation of binding occurs when the complementary binding sites of the protein in a binding unit on the adsorbent surface cannot accommodate further lattice sites.17 The corresponding half-saturation constant KS,0.5 relates to KS according to KS, 0.5 = (Ks)1/ns.12,16

The bulk ligand (i.e., protein) binding function, which corresponds to a classical protein adsorption isotherm, can be described by Eq. (2) 13,16,17:

| (2) |

where θB is the fractional saturation of binding units on the surface at a constant lattice site concentration with the bulk protein as independent variable, Cp is the bulk protein concentration at equilibrium, KB is the bulk-ligand adsorption constant, and nB is the bulk-ligand adsorption coefficient. For the case nB = 1, Eq.(2) also reduces to a rectangular hyperbola. Saturation occurs when the solid phase surface cannot accommodate additional protein molecules. The half-saturation constant KB,0.5 in this case relates to KB according to KB,0.5 = (KB)1/nB.12,15,16

B. Adsorption Kinetics

The basic parameter of any adsorption kinetics is the number of protein molecules adsorbed per unit area in any increment of time, dΓp/dt. It is generally accepted that the adsorption/desorption process comprises the following subprocesses: transport toward the interface, attachment at the interface, detachment from the interface, and transport away from the interface.2

Each of these steps can, in principle, determine the overall rate of the adsorption process. Hence, one needs to design the adsorption kinetics experiment in which only one of the four steps will dominate. For example, transport of protein from solution toward the interface will usually occur by diffusion or by a combination of convective–diffusive processes. At low protein concentration, the rate of transport may be slower than the rate of actual attachment of protein to the surface. As a result, the measured adsorption kinetics may only contain information about the transport and not about the actual attachment kinetics.

C. Single Protein vs Multiprotein Adsorption

It is not unlikely that more than one type of protein is present in solution. This situation is common for all body fluids. In a multiprotein adsorption, differences between the interactions of each protein with adsorbing surface, as well as lateral protein–protein interactions, will determine the outcome of the adsorption. The competitive nature of the protein–surface interactions often result in transient dominance of one protein over others.20 The solution protein exchange with a surface protein may be direct or through an adsorption site made available transiently by desorption of an adsorbed protein. Models for such protein–protein exchange usually involve a notion of monolayer coverage based on the assumption that a finite surface capacity exists for each competing species.

D. Adsorbent Surfaces and the Role of Water

Protein–surface interactions are influenced by the physical state of both the adsorbent and the solution environment. The important factors, including surface energy, its polar and nonpolar contributions, surface charge, and surface roughness, all have to be considered in defining the role of the solid–solution interface. The use of well-defined surfaces with a known surface density of protein-binding sites helps in the interpretation of protein interracial characteristics. In all studies, the surface for protein adsorption will have to be characterized thoroughly, or even engineered specifically to fit the aim of the study. Adsorbents with immobilized protein-binding residues are particularly suitable for fundamental protein adsorption studies. In contrast to model surfaces, “real” surfaces, even when they are not characterized rigorously, are more interesting from a practical point of view.

Most surfaces acquire electric charge when exposed to ionic solution. Although a charged protein is expected to prefer adsorption onto an oppositely charged surface, the osmotic pressure of counterions, the desolvation of the charged groups, and burying of the charges into a low dielectric medium may, in fact, oppose adsorption. Considered alone, electrostatic interactions may not fully account for the attachment of proteins to a charged interface.

Similar to the role that they play in maintaining the compactness of protein structure, hydrophobic interactions between an adsorbent surface and protein are of utmost importance. Proteins with a significant fraction of solution-exposed hydrophobic residues will tend to adsorb strongly to hydrophobic adsorbents. In some cases, dehydration of the hydrophobic surface of an adsorbent alone may tip the adsorption-free energy balance in favor of strong adsorption.

III. Review of Methods for Studying Protein Adsorption

A. Solution Depletion Technique

Solution depletion is one of the simplest methods to study protein adsorption. One measures a concentration change in bulk solution prior to and after adsorption, Δcp. In the solution depletion technique, any protein concentration change is attributed to the adsorbed layer, i.e., Γp = ΔcpV/Atot, where V is the total volume of protein solution and Atot is the total area available for adsorption. Choices of protein concentration measuring technique are numerous: UV absorption, fluorescence, colorimetric methods, and many other, including the use of radioisotope-labeled or fluorescently labeled proteins. The solution depletion method requires a high surface area material such as beaded and particulate adsorbents (see Section IV,B,1).

Chromatographic adsorption media are generally in a particulate or beaded form. For example, 4% porous agarose beads (Sepharose 4B) have a surface area of ca. 8 m2/ml of packed gel available for protein adsorption.17 For ground quartz glass powder of a mean particle diameter of ca. 15 µm, a specific surface area of ca. 7 m2/g has been determined by the BET-isotherm method with N2 (H. P. Jennissen and A. Remberg, 1993, unpublished). Both types of adsorbents can be modified further chemically for protein adsorption studies.

In principle, protein adsorption on particulate or beaded materials can be measured either by zonal chromatography or by batch methods. Both methods lead to comparable results.17 Such chromatographic methods, with the exception of complex competitive analytical chromatographic systems of the zonal and the continuous type,21 are generally only applicable to low-affinity adsorption systems.17 These systems will therefore not be treated here. Because protein adsorption to natural and artificial surfaces is generally of high affinity, simple chromatographic methods developed for the measurement of such interactions will be treated. One should, however, keep in mind that the column in such high-affinity chromatographic systems is washed with buffer after the protein adsorption step so that the free equilibrium bulk concentration of the protein is not clearly defined. This effect generally has little influence on the adsorbed amount of protein so that valuable information on the adsorptive behavior of proteins and surfaces is nevertheless obtained.

Batch methods, however, are especially suited for measuring both high- and low-affinity protein–surface interactions under equilibrium conditions. Because batch methods involve stirring with the aim of suspending the particles in the stirred protein solution, they are best suited for beaded low-density materials (e.g., gel beads). If the particle size is too large or the density is too high (glass, inorganic material, or metal powders), very high stirring rates may have to be employed with the danger of protein denaturation (“egg-beater effect”). If the surface of the particles is too irregular (e.g., with sharp edges) the “egg-beater effect” will be increased. The methods reported in Section IV,B,1 have been tested extensively with agarose beads (Sepharose 4B) and proteins varying in size from calmodulin (17 kDa) to phosphorylase kinase (1.2 MDa). Under the conditions described, no significant denaturation of these proteins was detected.

Batch methods are very well suited for the determination of adsorption and desorption isotherms, including adsorption hysteresis,16,22 and also for monitoring sorption kinetics23 of proteins on particulate or beaded materials. Such studies are generally hampered by complicated sampling procedures usually involving centrifugation steps to obtain a bead-free supernatant. In addition to the long time intervals needed for centrifugation, this separation method may also influence the equilibrium by concentrating effects beads finally localized in the pellet. A novel method, described in Section IV,B,1, was developed to circumvent centrifugation.12

B. Optical Techniques

In the category of optical techniques, the most commonly used ones are ellipsometry,24 variable angle reflectometry,25 and surface plasmon resonance.26 In ellipsometry, polarized light is reflected obliquely from the interface under investigation. Optical properties of the reflecting surface can be determined from changes in the phase and amplitude of the reflected polarized light. When an adsorbed protein layer is present at the interface, these changes can be related to the thickness and the refractive index of the layer. The method of ellipsometry has been used extensively for in situ, real time single protein adsorption studies.27–29 The method of variable angle reflectometry25 is somewhat similar to ellipsometry. The method involves measurements of reflection coefficients of the polarized beam at angles of incidence in the vicinity of the Brewster angle. The technique of surface plasmon resonance (SPR) is described elsewhere in this volume.29a

C. Spectroscopic Techniques

Whereas optical techniques rely mostly on the interactions between light and an adsorbed protein layer, spectroscopic techniques for protein adsorption studies depend on the interaction of photons with some parts of the adsorbed protein molecules. The magnitude of the spectroscopic signal can often be related to the amount of adsorbed proteins, whereas at the same time spectral information can yield information on the conformation of adsorbed proteins. Fluorescence spectroscopy, infrared absorption (IR), Raman scattering, and circular dichroism (CD) are examples from this category of techniques. Surface-sensitive spectroscopic techniques require that the photons are (mostly) interacting with adsorbed protein molecules and much less so with bulk solution dissolved proteins. The use of surface-sensitive spectroscopic techniques in protein adsorption has been reviewed.7

Fluorescence emission spectroscopy offers a great specificity and sensitivity in protein studies. It can utilize both intrinsic protein fluorescence and a variety of extrinsic fluorophores attached to protein molecules.30,31 Many variants of fluorescence spectroscopy used to study proteins in solution can be applied to protein molecules adsorbed at interfaces. The most common way to achieve a surface sensitivity is to excite adsorbed protein fluorescence with an evanescent surface wave generated by the total internal reflection of the excitation beam.32,33 The technique of total, internal reflection fluorescence spectroscopy (TIRF), described in detail in Section IV,C, is often used to study kinetics of protein adsorption.33–35

In IR spectroscopy the spectral region between 1100 and 1700 cm−1 can provide information on global properties of the polypeptide conformation. In fact, it was one of the earliest methods employed to study the secondary structure of proteins.36 The so-called amide I band, located in the wavenumber region approximately between 1600 and 1700 cm−1 (i.e., at wavelengths around 6 µm), is the most frequently studied parameter in protein IR studies. This characteristic band primarily represents the C = O stretching vibrations of this chemical group in the protein backbone. The frequency of this vibration depends on the nature of the hydrogen bonding in which the C = O group participates, which makes it highly sensitive to the secondary structure adopted by the polypeptide chain, e.g., α helices, β sheets, turns, and random coil structures, and thus provides “fingerprints” for protein secondary structure elements.37 In addition to “classical” ATR-IR spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared reflection absorption spectroscopy (FT-IRAS) and Fourier transform-attenuated total reflection infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) are used commonly in protein adsorption studies. ATR-FTIR examples include studies of the adsorbed amount of plasma protein onto surfaces of different commercial polymers38–40 and studies of secondary structure alterations in adsorbed proteins after being subjected to different sorbents41–44 and protein aggregation.45,46

Autoradiography and Microscopic Techniques

The use of radioisotope-labeled proteins in protein adsorption studies is very common. The detection of adsorbed protein utilizes radioisotope counting or autoradiography. The latter method can provide spatially resolved information about adsorbed proteins on a micron-sized scale.

Almost all of the techniques described earlier will average over many thousands, if not millions, of adsorbed protein molecules. Hence, the local distribution of adsorbed protein molecules is unknown. Spatial information about adsorbed species requires some form of high-resolution microscopy. The scanning force microscopy technique can be applied to dynamically image protein adsorption or record the topography of an adsorbed protein layer.47 Advances in near-field scanning optical microscopy (NSOM) and the capability of single molecule detection, including monitoring spectroscopic properties of a single adsorbed protein molecule,48 have promising potential for protein adsorption studies.

IV. Protocols for Protein Adsorption Studies

The following sections contain a set of protocols used by the authors in studying protein adsorption. The reader is referred to the original papers for additional information not included due to space limitations. Some of the following protocols are applied to a particular protein; they can be applied to other proteins with minimum modifications.

A. Protocols for Protein Labeling and Surface Modifications

The radioisotope of iodine (125I) is often selected as a probe for the quantitative determination of the amount of protein adsorbed to the various types of surfaces for several reasons: elemental iodine is chemically reactive; it can be bonded covalently to protein; an iodine atom is relatively small, so it is expected to have minimal influence on protein properties; radiation from 125I is detected easily; and handling of 125I can be made reasonably safe.

125I emits strong γ-radiation with the energy of 35 keV during its conversion to 125Te.49 The half-life of the radioisotope (59.6 days) gives a good balance between the efficiency of radioactivity detection and safety.

1. Protein Labeling with 125I Using Iodine Monochloride

There are several chemical routes to label protein with 125I. Typically, an oxidant incorporates 125I into a protein molecule by replacing the hydrogen at the o-position of the tyrosine benzene ring with 125I. Commonly used oxidants are iodine monochloride, ICl, and chloramine-T. The ICl protocol for labeling fibrinogen using the modified procedure from McFarlane50 is given later. This reaction is considered to be much more gentle compared to the chloramine-T method; the ICl method has been shown to minimize damage to the fibrinogen molecule.51

A 2-ml solution of 5 mg/ml fibrinogen (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) in pH 9.0 glycine buffer, freshly made 25 µl of 1 mM ICl in pH 8.5 glycine buffer, and 1 mCi of Na125I (carrier free, 97%, Amersham Life Science, Cleveland, OH) are mixed together. The iodination reaction takes place at 4° for 1 hr. The reaction mixture is eluted through a PD-10 minicolumn (Pharmacia Piscataway, NJ) with 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), and a 2-ml fraction is collected after the first eluted 2.5 ml. The protein concentration is determined by measuring the UV absorption at 280 nm using the extinction coefficient of 513,400 cm−1 M−1.52.52

The degree of fibrinogen labeling is computed from the protein and protein-bound 125I concentrations. Total 125I in protein solution is determined by measuring solution radioactivity and comparing it with the 125I standard (i.e., Na125I solution). The amount of free 125I present in 125I-labeled fibrinogen solution is determined using protein precipitation in trichloroacetic acid (TCA, Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The control sample is made of a mixture of 45 µl of bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution (20 mg/ml), 50 µl of PBS, and 5 µl of 125I-labeled fibrinogen solution. The test sample is prepared from 45 µl of BSA solution (20 mg/ml), 50 µl of TCA (20% solution), and 5 µl of 125I-labeled fibrinogen solution. Both samples are centrifuged at 15,000 rpm in a minicentrifuge (Model 235A, Fisher) for 10 min. Five microliters of both the control sample and the supernatant of the precipitated test sample are counted for γ-radiation using the γ-counter (Model 170M, Beckman Instruments). The ratio of radioactivity in the supernatant of the precipitated sample to that in the control sample should be less than 0.05, i.e., less than 5% of total 125I is free in the solution.

2. Protein Labeling with 1251 Using Chloramine-T

If a higher degree of protein labeling is required, the chloramine-T method can be used. The following protocol is shown applied to the labeling of bovine serum albumin.49 An aliquot of NaI25I solution amounting to a 0.3 mCi radioactivity (a few microliters at most) is added to a 0.5-ml solution of 1.5 mg/ml BSA (fraction V, ICN, Costa Mesa, CA). Subsequently, 50 µl of freshly prepared 4 mg/ml chloramine-T (Kodak, Rochester, NY) solution made in deionized water is added and allowed to react under gentle mixing for 1 min. Immediately thereafter, 50 µl of a 4.8-mg/ml sodium metabisulfite (Na2S2O3, Mallinckrodt, Phillipsburg, NJ) solution is added to the mixture to stop the oxidation reaction. Free 125I is removed as described in Section IV,A,1 or by passing the mixture through two Sephadex G-25 minicolumns (ca. 6 cm long, 1 cm in diameter) packed with a coarse grade resin of Sephadex G-25 (Pharmacia) under a centrifugation force of 40g. Each of these columns will accommodate about half the sample volume (0.3 ml). Free 125I in the protein fraction can be determined using the TCA precipitation protocol (see Section IV,A,1).

3. Protein Labeling with Fluorescein Isothiocyanate

Many protein molecules contain one or several tyrosine, tryptophan, or phenylalanine residues that are intrinsically fluorescent in UV.31 The applications of protein intrinsic fluorescence in the adsorption experiments are technically limited by the short wavelengths of excitation and emission and by the low quantum yields.53 Because of that limitation, labeling of proteins with extrinsic fluorescent probes is a common practice.54

In the protocol that follows, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) is used as a model fluorescent label for human serum albumin (HSA). Isothiocyanate moiety reacts selectively with the amine groups of protein, although it is also known to react reversibly with thiols and the phenol groups of tyrosine.54 The FITC reaction with proteins generally gives a satisfactory yield and is quite a simple procedure. The dye has a high absorbance and emits strong fluorescence in aqueous solution. The fluorescein absorption band matches the wavelength of the commonly used Ar+ ion on laser line at 488 nm. FITC is readily water soluble, and the isothiocyanate group is reasonably stable in most buffer solutions for proteins.

The labeling of human serum albumin (ICN) with FITC (Isomer I, Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI) follows the method of Coons et al.55 Sixty milligrams of HSA is dissolved in 3 ml of carbonate–bicarbonate buffer (CBB, 0.1 M, pH 9.2). Of the freshly made FITC solution (1 mg/ml) in CBB, 0.6 ml is added to the HSA solution and the reaction is allowed to take place at room temperature for 3 hr. The protein–FITC mixture is then loaded on a PD-10 minicolumn (Pharmacia). The column is eluted with PBS (0.01 M, pH 7.4). The first colored fraction (protein-dye conjugate) is collected and its absorption at 280 (A280) and 494 (A494) nm is measured by a UV–visible spectrophotometer. The molar concentrations of FITC, cFITC, and HSA, cHSA, are determined as

| (3) |

and

| (4) |

where εFITC and εHSA are the extinction coefficients of FITC (76,000 cm−1 M−1)54 and HSA (35,279 cm−1 M−1),52 respectively. A constant, 0.308, is the ratio of FITC absorption at 280 nm to that at 494 nm. The degree of labeling (cFITC/cHSA) is typically around unity.

A similar protocol can be used to label other proteins. The degree of labeling can be adjusted by changing the protein/dye molar ratio in the reaction mixture. The final result, however, will vary from protein to protein because it will depend on the number of reactive amine groups at pH 9.2 and their accessibility.

4. Chemical Modification of Silica Surfaces

In any surface modification it is absolutely critical to start the chemical reaction with a clean surface. The following surface modification protocols are shown applied to flat fused silica plates or glass beads. Identical protocols can be applied to oxidized silicon wafers. The fused silica plates (ESCO Products, Oak Ridge, NJ) or glass bead (diameter 5–50 µm, Duke Scientific, Palo Alto, CA) surfaces are first cleaned by submerging them in piranha solution (70% H2SO4: 30% H2O2) for 15 min and subsequently rinsed thoroughly with deionized water. After drying in a vacuum desiccator, the surfaces are further cleaned with a radio-frequency generated oxygen plasma (200 mTorr, 50 W) (PLASMOD, Tegal Corp., Richmond, CA) for 2 min. An alternative cleaning procedure consists of immersing the silica plates (or beads) in hot chromosulfuric acid at 80° for 30 min, rinsing the surfaces thoroughly with deionized water and drying them in a vacuum desiccator. The cleanliness of flat silica surfaces can be verified by measuring the water contact angle either by a sessile drop or by the Wilhelmy plate technique.56 The clean silica surface should be fully wettable.

a. APS SILANIZATION

In the surface modification with 3-aminopropyltriethoxy silane (APS, Aldrich), the silica surfaces are reacted with a fresh ethanol solution of APS [5%(v/v) APS, 5% (v/v) deionized water, and 90%(v/v) absolute ethanol] for 30 min at room temperature, followed by rinsing thoroughly with deionized water and with absolute ethanol two times and by subsequent curing in the vacuum oven, which has been flushed with nitrogen three times at 80° overnight.

b. DDS SILANIZATION

In the surface modification with dimethyldichlorosilane (DDS, United Chemical Technologies, Bristol, PA), the silica surfaces are reacted with a freshly prepared dry toluene solution of DDS [10% (v/v) DDS and 90% (v/v) toluene] for 30 min at room temperature. The slides are then rinsed consecutively with absolute ethanol three times, with deionized water five times, and with ethanol again followed by curing in the vacuum oven (see earlier discussion). In both cases the silanized silica slides are stored at room temperature and used within 72 hr.

c. GPS SILANIZATION

In the surface modification with 3-glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane (GPS, United Chemical Technologies), the surfaces are placed in an Erlenmeyer wide-mouthed reaction vessel to which 1% (v/v) GPS and 0.2% (v/v) triethylamine in dry toluene is added. The vessel needs to be equipped with a CaC12 drying tube and is suspended in a heated water bath, where it is heated to 70° for 8 hr, stirred overnight at room temperature, and heated another 8 hr before washing with toluene and acetone. The GPS-modified silica surfaces are then dried in a vacuum oven.

d. LIGAND IMMOBILIZATION TO MODIFIED SILICA SURFACES

It is sometimes of interest to measure binding of protein from solution onto a surface that carries a particular ligand. Both APS- and GPS-modified silica can further be used to immobilize various ligands. In the case of APS-modified silica, the terminal surface group is an amine moiety that reacts with the isothiocyanate group, N-hydroxysuccinimide ester, and many other groups.57 The APS-modified surfaces can also be “activated” with a cross-linker such as glutaraldehyde. The GPS-modified surface contains terminal epoxide groups that react with primary amines or sulfhydryls or it can be activated further with a cross-linker such as 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole (CDI). The reader is referred to specialized monographs that contain a large number of protocols for ligand and protein immobilization to surfaces.57–59

B. Protocols for Protein Adsorption Experiments

1. Adsorption Experiments Using High Surface Area Adsorbents

The following four protocols show the use of high surface area adsorbents. In each protocol the protein concentration in solution needs to be determined after adsorption took place. Protein concentration can be measured directly, according to the method of Lowry et al.,60 by measuring the UV absorbance or fluorescence of the protein, using 125I or FITC labels, or, in the case of adsorption of enzymes, by measuring the enzymatic activity of the protein.

a. SATURATING SAMPLE-LOAD COLUMN METHOD

This method can be employed for all sorts of gel particles (low density) and also for glass, inorganic material, or metal powders. The saturation sample-load method should be employed if one wants to compare the absolute capacity of different gels or powders at a defined bulk protein concentration. Methods employed for the measurement of adsorption of the enzyme phosphorylase b to butyl-Sepharose 4B particles at 5°, described briefly later, can be found in more detail elsewhere.12,16,23 Before use, the protein, e.g., phosphorylase b, is dialyzed extensively against the adsorption buffer (buffer A containing 10 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane/maleate, 5 mM dithioerythreitol, 1.1 M ammonium sulfate, 20% sucrose, pH 7.0).16 Sucrose is included in buffer A to minimize nonspecific adsorption to the agarose gel backbone. Before adsorption the substituted beaded or particulate adsorbent is equilibrated with adsorption buffer. Low-volume Plexiglas columns (1 cm i.d. × 12 cm height) containing 1–3 ml packed gel or larger volume columns (with a large cross section for fast flow) with the dimensions 2 cm i.d. × 15 cm height filled with 10–20 ml packed gel can be employed. A purified protein solution (phosphorylase b) or a crude extract is applied by pump or gravity to the columns until no more enzyme is adsorbed, i.e., until the protein concentration in the run-through is identical to that in the applied sample. The columns are then washed with a 10- to 50-fold buffer volume until significant protein can no longer be detected in the run-through. The elution of protein is either accomplished by specific affinity agents, salts,61 or, for protein balance studies, by denaturants, e.g., urea, SDS applied to the column in buffer. The adsorbed amount of protein is calculated from difference measurements of the amount applied and the amount in the run-through or by elution of the adsorbed protein by a strong denaturing detergent mixture such as 0.1 M NaOH, 1% SDS and subsequent determination of the protein amount in this eluent.

b. LIMITED SAMPLE-LOAD COLUMN METHOD

This method can also be employed for all sorts of gel particles and for glass, inorganic material, or metal powders. The limited sample-load method is a good screening procedure for a series of adsorbents or protein samples. In this method a defined amount of protein (e.g., 1 mg) in a defined sample volume is applied to each column under identical conditions. The applied nonsaturating amount is dimensioned so as to be 100% adsorbed (i.e., no protein in run-through) on an adsorbent displaying the expected maximal affinity and capacity. The method allows a comparison of relative adsorption capacities and affinities of adsorbents on a quantitative chromatographic basis. This method, employed for quantitative evaluation of the adsorption of calmodulin, fibrinogen, and peptides to beaded agarose adsorbents of varying hydrophobicity, is exemplified next.

In the case of calmodulin quantitative adsorption, chromatography is performed on a column (0.9 × 12 cm) containing 2 ml of packed gel of various alkyl agaroses. The gel is washed and equilibrated with 20 volumes of buffer B (20 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.0). One milligram of purified calmodulin is applied to a sample volume of 1 ml (in buffer B) and 1-ml fractions are collected. The column is then washed with 9 ml buffer B and then with 9 ml buffer C (= buffer B + 0.3 M NaCl). The adsorbed calmodulin is eluted with buffer D [20 mM Tris-HCl, 0.3 M NaCl, 10 mM ethylene glycol bis(β-aminoethyl ether) N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, i.e., EGTA, pH 7.0]. The EGTA chelates the calmodulin-bound Ca2+, thereby changing the conformation of calmodulin to a more hydrophilic species leading to elution. For quantifying tightly bound, i.e., “irreversibly bound,” calmodulin on highly hydrophobic columns elution is continued with 7.5 M urea and finally with 1% SDS added to the adsorption buffer.62

Quantitative hydrophobic adsorption chromatography of fibrinogen is performed on the same column type containing 2 ml of packed gel. The gel is washed and equilibrated with 20 volumes buffer E (50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4). As sample 1 mg purified fibrinogen is applied in a volume of 1 ml (in buffer E) and 1.5-ml fractions are collected. The column is then washed with 15 ml buffer E and eluted with 7.5 M urea and at high hydrophobicity of the gel with 1% SDS.62

Quantitative hydrophobic adsorption chromatography of a tripeptide, Trp–Trp–Trp (Paesel & Lorei, Frankfurt, 98.5% purity) is performed on a column (0.9 × 12 cm) containing 2 ml of packed gel. The gel is washed and equilibrated with 20 volumes buffer F (1 mM sodium β-glycerophosphate, pH 7.0). As sample 1 mg Trp-tripeptide is applied in a volume of 1 ml (in buffer F) and 1.5-ml fractions are collected. The column is then washed with 15 ml buffer F and eluted with 1% SDS.62 Calmodulin, fibrinogen, and the tripeptide in the obtained fractions are measured directly according to the method of Lowry et al.60 employing BSA or the Trp-tripeptide as standard.

In the examples of quantitative analytical chromatography given earlier, the experiments can be performed at room temperature, good flow is usually achieved by gravity, and only a fresh, nonregenerated gel should be employed for each experiment.62

c. BATCH DEPLETION METHOD: ADSORPTION

In the batch adsorption method, the nonadsorbed protein is typically separated from adsorbed protein by a centrifugation process.22 A faster sampling method was developed to circumvent the slow centrifugation step.12 The decisive components that make this method a simple procedure are easy to make: (a) stainless-steel sampling tips for disposable syringes and (b) thermostatted beakers of volumes varying from 20 to 500 ml, which allow magnetic stirring of the contents. The top end of the sampling tip (diameter 7 mm15) is constructed similar to a column adapter and is covered by a stainless-steel grid (screen) with a pore size of ca. 10–20 µm soldered to the steel adapter so as to exclude the gel beads or particulate adsorbent material during sampling. The bottom end of the sampling tip corresponds to that part of a hypodermic needle (cannula) that fits onto a syringe. Gel beads/particle-free buffer can now be aspirated directly form the particle suspension being stirred in the thermostatted beaker. The aspirated sample volume can be varied from 100 to 3000 µl, but should be held small compared to the total volume of the stirred gel suspension so that an influence on the bead concentration remains negligible. The very short sampling time of 3–5 sec allows a sampling time resolution of ca. 10 sec23 in kinetic studies with two persons sampling. Often the measurement of such high-resolution kinetics is not necessary. However, the monitoring of low-resolution kinetics is essential for establishing the existence of equilibrium in the case of adsorption and desorption isotherms.16

In the batch method, the procedure used for determining the protein concentration is of prime importance for the sensitivity of the method and the range of the isotherm. In the case of phosphorylase b, three methods were employed. Protein determinations according to Lowry12,60 can be performed reliably in volumes of ca. 500 µl down to ca. 5–10 µg/ml. The catalytic activity of phosphorylase b allows the determination of the enzyme to concentrations of 2–3 µg/ml in very small sample volumes down to 50 µl.16 A radioactive labeling of protein allows protein determinations in the range of 200–500 ng/ml.12,16 Somewhat lower sensitivity is expected for proteins labeled with FITC.

In typical adsorption isotherms on the beaded alkyl agarose adsorbent (alkyl-Sepharose 4B) the free concentration of phosphorylase b at apparent equilibrium16 is usually between 0.05 and 0.5 mg/ml. The adsorbed amount of protein is calculated from the difference between the initial and the final protein concentration, i.e., from Δcp. A parallel experiment with control gel (unsubstituted Sepharose 4B) yields the amount of nonspecifically adsorbed protein, which is subtracted. Volume changes due to sampling have to be considered in these calculations. The amount of adsorbed protein is expressed in milligrams per milliliter of packed adsorbent or per meter squared surface area.12,17 The calculated amount of enzyme corresponds to the amount that can be released from the gel in the presence of 0.1 M NaOH, 1% SDS.16 A new incubation mixture is usually employed for each measurement, i.e., for each data point on an adsorption isotherm or kinetics plot.

Before measuring the actual adsorption isotherm, the adsorption kinetics should be determined in the protein concentration range that the isotherm is expected to cover. This is important for guaranteeing that equilibrium is being obtained for all isotherm points. The adsorption time curve is determined by adding 0.5–1.5 ml of equilibrated packed Sepharose measured in a thermostatted, graduated column61 to 20 ml of buffer containing phosphorylase b in an initial concentration of approximately 0.01–1.5 mg/ml. The adsorption isotherm can be calculated directly from such adsorption time curves. Once the latter is known, the isotherms can be determined by only measuring the time end points of adsorption at equilibrium. The incubation mixture of 20 ml is stirred in a thermostatted Plexiglas beaker (2.5 cm i.d. × 9 cm, stirring bar 1.5 cm) until equilibrium is reached. A homogeneous incubation mixture is usually obtained when the speed of the stirring bar exceeds 150 rpm. For a good mixing, speeds of 500–700 rpm are generally recommended. Alternatively, incubation beakers of 60 ml volume (beaker size 3.5 cm i.d × 9 cm, stirring bar 3 cm, stirring velocity 450 rev/min) may be employed. The capacity of the adsorbent for the protein ligand in these systems is independent of the stirring rate. Examination of the substituted Sepharose under a phase microscope (Leitz) demonstrated that stirring at 700 rpm for 2 hr (20-ml beaker) did not lead to fragmentation of the beads. Samples of 0.2–0.5 ml gel-free buffer are obtained by suction with a disposable 2-ml plastic syringe through a stainless-steel sampling tip (pore diameter of steel grid 20 µm, see earlier) that excludes the Sepharose 4B spheres (bead diameter ca. 40–190 µm, Pharmacia). After each sampling procedure, the steel grid is washed by pressing 2–4 ml of H2O, 0.5 M NaCl, H2O, and, finally, acetone, respectively, through the grid with the syringe. The grid is then removed and dried in a stream of pressurized air and is ready for reuse. The washing and drying procedure of the sampling tip takes about 1 min. A fresh disposable syringe is employed for each sample.

d. BATCH REPLETION METHOD: DESORPTION

When protein desorption is measured by dilution experiments, as is described in this section, then the protein concentration in the bulk solution increases in time (after addition of loaded gel) through dissociation from the solid surface until a new equilibrium is reached (repletion). Because the amount of protein released from such a surface is usually very small,16 sensitive methods of detection have to be applied in order to measure the new equilibrium concentration of protein. In general, only an isotope-labeling procedure (e.g., 3H, 125I) allows reliable determinations of the protein concentration in desorption experiments. Should such a labeling procedure be chosen, then it is essential to make any dilution of the specific radioactivity of the labeled protein only with cold-labeled protein and not with unlabeled protein.16 This procedure avoids the generation of two different protein populations, i.e., heterogeneity, in the adsorption–desorption mixture.

Before measuring the actual desorption isotherm, the desorption kinetics should be determined in the selected protein concentration range to ensure attainment of equilibrium. In measuring desorption by dilution, the adsorbent gel is first loaded with protein in an adsorption experiment (60–90 min). At apparent equilibrium, the gel loaded with protein is isolated from the bulk buffer solution (time, 10–20 min) by first removing the buffer carefully with the sampling tip and then applying the gel slurry for further concentration to a small thermostatted, graduated column that is allowed to run “dry” by gravity. In this way, the liquid phase is effectively removed from the gel (= loaded gel), which can then be diluted into a beaker for desorption measurements. As shown previously, the concentration of gel beads in this way has no measurable effect on the attained adsorption equilibrium.16 The protein is in the adsorbed state on the gel prior to dilution for a maximal time of 70–100 min. For the following dilutions of the gel volume by factors of 1:10 to 1:100, the freshly loaded gel (0.5–2.0 ml packed gel) is blown from the small column into a fresh protein-free buffer solution stirred in a thermostatted beaker of 2.5 cm i.d. (20 ml) or 3.5 cm i.d. (60 ml) as described previously.16 For high dilutions (e.g., 1:500 and 1:1000), a thermostatted 500-ml beaker (10 cm i.d. × 14 cm, stirring bar 8 cm, 200 rpm) is employed. An equally efficient mixing of the agarose buffer suspension is obtained at 700 (beaker 2.0 cm i.d.), 450 (beaker 3.5 cm i.d.), and 200 (beaker 10 cm i.d.) rpm. Under these conditions the desorption rate is independent of the stirring velocity.

After dilution of the protein-loaded gel into the buffer solution the desorption mixture is incubated for 90–120 rain until a new apparent equilibrium is reached (time independence). Samples of 1–3 ml are taken at regular intervals during this time using the steel grid method (sampling tip) for protein concentration determination assay such as radioactivity counting. As control unsubstituted Sepharose 4B is incubated for 90 min prior to dilution with a concentration of free protein, so chosen for adsorption, that a time-independent concentration of free protein, comparable to that obtained with the substituted gel at desorption equilibrium, is obtained.16 The amount of adsorbed protein is then calculated as described earlier.

2. Adsorption Experiments Using Flat Surface Adsorbents

The following protocols describe the use of flat, low surface area, fused silica in protein adsorption experiments. The advantage of flat silica is that its surface can be modified chemically (see Section IV,A,4) to carry a specific chemical group, immobilized ligand, or another protein. Together with similarly modified, smooth silicon wafers, these surfaces can be used in ellipsometry and atomic force microscope protein adsorption studies. Transparent flat silica surfaces are also needed for evanescent wave fluorescence spectroscopy (see Section IV,C). Due to the small surface area of flat surfaces, the solution depletion methods cannot be used at all and the detection of adsorbed protein has to be carried out directly on the flat adsorbent.

a. RADIOLABELED PROTEIN ADSORPTION ONTO A FLAT SILICA SURFACE

Fused silica plates small enough to fit into the counting chamber of a γ-counter (2.5 × 0.9 × 0.1 cm, area 5.2 cm2) are cut with a diamond saw (Buehler) and their sides are polished. The plates are cleaned and modified chemically as desired. The adsorption chambers are prepared from a glass tube (1.0 cm i.d.). The length of the chamber is chosen so that it can accommodate three small plates. One end of the glass tube is drawn to allow 3/16-inch i.d. plastic tubing to fit tightly: the tubing leads to a waste container. The other end is fitted with a rubber stopper pierced with a 1:1/2-inch 18-gange syringe needle. When joined with a three-way stopcock, the addition of protein and buffer solutions to the adsorption chamber is easy.

Three silica plates are placed in each chamber and the chamber is prewetted with buffer solution. The buffer is drained and 10 ml of 125I-labeled protein solution is injected slowly, completely filling the chamber. Different concentrations of protein are used in each chamber: the 125I-labeled protein concentration is set as needed for an adsorption isotherm determination. Adsorption is allowed to proceed for 30 min after which each chamber is flushed with 6 volumes of buffer and drained. Each plate is removed carefully, placed in a capped scintillation vial, and counted for 1 min in a γ-counter (Model 170M, Beckman Instruments). One-hundred microliter aliquots of each 125I-labeled protein solution are counted separately. Counts obtained from the 125I-labeled protein solution are used to construct a calibration curve (i.e., radioactivity counts vs protein amount) from which the amount of adsorbed protein is calculated.53 The protocol can also be applied to study adsorption of one 125I-labeled protein from a multiprotein solution mixture.

b. AUTORADIOGRAPHY AND PROTEIN ADSORPTION FROM FLOWING SOLUTION

In some applications one is interested in protein adsorption taking place from a flowing rather than from a quiescent solution. When protein adsorption takes place in a narrow and long flow chamber the adsorbed amount will not be the same at the beginning and at the end of the chamber even if the adsorbing surface is identical everywhere in the chamber. This effect is due to the depletion of protein along the flow direction. The interplay between the flow and the adsorption is even more complex in the case of adsorption from the multiprotein solution. In such cases one needs to record the protein-adsorbed amount at each surface position along the flow direction. One way of achieving this spatial resolution is to use 125I-labeled protein and autoradiography.63 A simple protein adsorption experiment that employs a dual rectangular channel flow cell and adsorbed protein detection using autoradiography is described. A schematic of the autoradiography flow cell can be found in Lin et al.64 The cell support is made of a poly(methyl methylacrylate) (PMMA) block (dimensions: 2.54 × 2.54 × 7.62 cm) with dual ports. A surface-modified silica plate (dimensions: 0.1 × 2.54 × 7.62 cm) serves as the other interior surface. A gasket of silicone sheet (0.05 cm thick) is placed between the PMMA block and the silica plate. The silicone rubber gasket defines the dimensions of the flow channel: 0.05 × 0.5 × 6 cm. The dual-flow channel cell is assembled using two aluminum plates and six screws to provide a water-tight sealing. Prior to the protein adsorption experiment, both the channels are filled with buffer solution.

In the actual experiment the protein adsorption is started by flowing the protein solution through the first channel of the flow cell with a given flow rate. In the present example, a 0.4-mg/ml solution of 125I-labeled low-density lipoprotein, [125I]LDL, is used and the flow is 0.84 ml/min. After a desired period of time, the flow is switched to the buffer solution to remove the unbound proteins from the flow cell and allow for desorption. At the end of the adsorption–desorption cycle, 3 ml of 0.6% glutaraldehyde in buffer solution is introduced into the flow channel to fix the adsorbed protein molecules for 5 min. The flow channel is then emptied by introducing the air. Subsequently, another adsorption–desorption experiment is carried out in the second flow channel using the same surface. The flow cell is disassembled and the surface with fixed adsorbed protein is subjected to autoradiography. A DDS-treated silica plate with a set of known amounts of [125I]LDL is prepared separately to serve as an autoradiography calibration standard for the quantification of adsorbed protein. The known amounts of [125I]LDL are applied as small droplets to the DDS-treated plate and dried completely.

The autoradiographs are obtained using 5 × 7-inch photosensitive film (X-OMAT AR, Kodak, Rochester, NY) in a light-tight cassette. Both plates are covered with Scotch tape to avoid the contamination of film. The two plates are placed in a polyethylene bag and are brought in contact with an autoradiographic film. The film is exposed to the samples at low temperature (−70°) for 21 days. No intensifying screen is used as it degrades the spatial resolution of the autoradiographs. After a desired exposure time (typically 2–3 weeks), the exposed film is processed in an automated developer system.

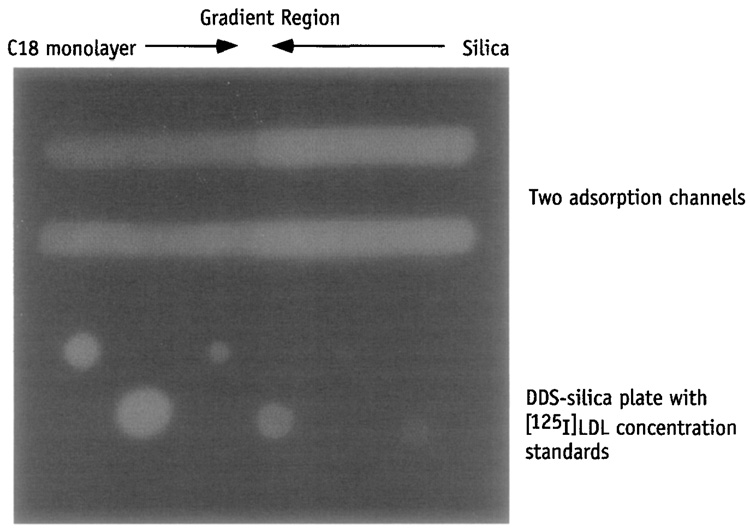

The optical density of the developed film can be recorded by any good quality imaging densitometer. The densitometer is first used to record the light source and then the autoradiographs of adsorbed protein and calibration plates. An example of a digitized autoradiography image of [125I]LDL adsorbed along a C18 silica gradient surface65 (upper half, Fig. 1) and of a plate with protein standards (lower half, Fig. 1) is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Autoradiograph of [125I]LDL adsorbed along the C18 silica gradient surface in two adsorption channels (top) and a DDS silica plate with [125I]LDL standards (bottom).

The integrated optical density, IOD, of each protein spot on the calibration plate is computed as a sum of background-subtracted optical density, ODcal:

| (5) |

measured at each individual “pixel” of the spot using the Beer–Lambert equation, where Int is the intensity of the light transmitted through the autoradiograph to the individual pixel of the CCD camera in the area of the protein spot, Into is the intensity of the light source reaching the camera pixel without the autoradiograph, and the subscripts “spot” and “back” represent the contribution from the protein spot area and background, respectively. Using this method, IOD of each protein standard is determined first. From the IOD of the standards, a calibrating relationship between the amount of protein (in mass per area unit) and IOD per pixel (in counts) is obtained. Using this calibration curve, the adsorbed amount of protein found in each channel is then calculated as a function of the gradient position. The adsorbed amount can also be presented as a two-dimensional map. Similar experiments, each performed with a different protein concentration, can be used to construct an adsorption isotherm for any given position on the adsorbent surface.

C. Protocols for Using Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence Spectroscopy

1. Intrinsic Protein Fluorescence TIRF Experiments

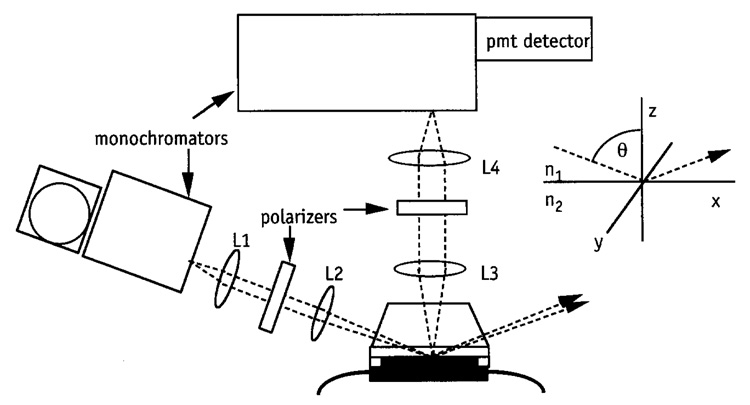

Among the techniques that provide information about the conformational state of protein molecules, fluorescence spectroscopy can be applied to both solution and adsorbed protein molecules.7 A variant of fluorescence spectroscopy for interracial studies, the total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) technique, is based on the phenomenon of total internal reflection: when an incident light beam impinges on the planar interface at an angle (Θi) greater than the critical angle (Θc), the beam is totally reflected. In the case when the interface is the one between the solid (refractive index, n1) and the solution (refractive index, n2), the totally reflected light creates an evanescent surface electromagnetic wave in the solution, thereby selectively exciting molecules that are close to the interface. The intensity (I) of the evanescent wave is a function of the distance (z) from the interface into the solution:

| (6) |

where Io is the intensity of the electromagnetic wave right at the interface and dp is the characteristic decaying distance, or so-called penetration depth of the evanescent wave, and it is related to the optical properties of the two phases:

| (7) |

where λo is the wavelength of the incident light in vacuum.

Although most of the protein adsorption TIRF studies are performed using fluorescently labeled proteins, it is also possible to utilize the intrinsic fluorescence of the tryptophan residues in UV.8,33 Advantages of intrinsic protein fluorescence spectroscopy are that the tryptophanyl fluorescence emission is sensitive to changes of protein conformation and that no labeling is required. The schematic of the UV TIRF apparatus is given in Fig. 2. The excitation light source is a 300-W high-pressure Xe lamp (R300-3, ILC Technology). The wavelength of excitation is selected by a monochromator (0.1 m, f/4.2, H10 1200 UV, ISA Inc.). The light is pseudo-collimated by a lens [L1, focal length (f.l.) 8 cm] and passed through a polarizer. The beam is typically polarized vertically with respect to the incident plane. The focused beam (L2, f.l. 10 cm) is directed normal to the face of the 70°-cut dovetail-fused silica prism where it totally reflects at the interface between the sorbent surface and the solution. The adsorbent surface consists of a quartz slide, which is optically coupled to the prism using glycerol. The quartz surface exposed to the protein solution can be modified chemically. A silicon rubber gasket is used to separate the slide from a black-anodized aluminum support creating a flow-through space, which is filled with solutions. Solutions are injected into the cell using syringes and the flow rate is controlled by a syringe pump. Fluorescence emitted from the interface is collected through the prism, collimated by a lens (L3, f.l. 3 cm), focused by another lens (L4, f.l. 9 cm) onto the slit of the emission monochromator (0.64 m, f/5.2, HR-640, ISA Inc., Metuchen, NJ), and subsequently detected by a cooled photomultiplier tube (R928, Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ). The photomultiplier signal is sent into a photon counter (SR 400, Stanford Research, Sunnyvale, CA) controlled by a PC computer for fluorescence emission measurements and data acquisition. Final alignment of the TIRF setup is performed by optimizing the fluorescent signal emitted from a cell filled with a solution that generates a high fluorescence. In addition to optimizing the fluorescent signal, accurate measurements require a low background light intensity. The background intensity can be lowered by shielding the pathway from the cell to the emission monochromator, by placing a cutoff filter in the excitation pathway, which will reduce the light intensity at emission wavelengths, and by performing experiments in the dark.

FIG. 2.

Schematic drawing of the UV TIRF setup. (Inset) Coordinate system. The solid/liquid interface is within the xy plane. The excitation beam is polarized normal to the plane of incidence (xz plane) and is incident at the solid/liquid interface at an angle, Θ, measured from the normal to the interface. Redrawn after J. Buijs and V. Hlady, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 190, 171 (1997).

2. Calibration of TIRF Using Fluorescence Standards

To quantify the adsorbed amount of proteins, the fluorescence intensity has to be calibrated. One method to perform such a calibration is by using standard fluorescence solutions.8,53 In general, the fluorescence intensity emitted by molecules excited by the evanescent wave is proportional to the probability of absorption, characterized by its extinction coefficient, ε, the fluorescence quantum yield, ϕ, the concentration of molecules, c, multiplied by the intensity of the evanescent wave, I. Both the concentration and the intensity are a function of the distance from the interface into the cell, z. The observed fluorescence signal, S, is written as

| (8) |

where f is an instrumental factor, which accounts for efficiency of fluorescence detection. The instrumental factor, f, is calibrated using a set of standard fluorescence solutions.53 In the UV range the TIRF set-up is typically calibrated by recording the fluorescence intensities of a number of tryptophan solutions with different concentrations. A suitable tryptophan solution is, for example, prepared using l-5-hydroxytryptophan (TRP). The fluorescence intensity of standard solutions emanates from adsorbed and nonadsorbed molecules in the evanescent field and from the fluorescence excited by scattered light. By increasing the fluorophore concentration, a point is reached for which the scattered light is entirely absorbed by solution molecules. After that point is reached, the fluorescence from nonadsorbed fluorophores present in the volume excited by the evanescent surface wave increases linearly with concentration. This linear increase, which reflects the increment in the measured fluorescence signal per increment in concentration (in units of absorption) of TRP solutions, is directly used to convert the fluorescence signal from adsorbed proteins into surface concentrations. The conversion is performed by normalizing, i.e., dividing, the fluorescence signal from an adsorbed protein layer to the fluorescence signals obtained from standard TRP solutions. The fluorescence of TRP emanates from molecules in solution, which are excited by the evanescent wave, and is derived by integration of the observed fluorescence signal, S. Because the size of an adsorbed protein is approximately two orders of magnitude less than the penetration depth of the evanescent wave, the protein concentration profile is considered as a quantity equal to the surface concentration, Γp, positioned at z = 0. After rewriting the normalized fluorescence intensity the surface concentration is expressed as

| (9) |

where the subscripts p and t refer to quantities of the protein and tryptophan standards, respectively. The remaining unknown parameters are the fluorescence quantum yields. Their ratio, ϕt/ϕp, is established from the ratio of the fluorescence intensity increments per unit of absorption for the respective bulk solutions.8 Note that the quantum yield of fluorophores is sensitive to its environment, and therefore, the fluorescence intensity in bulk solution can differ from that in the adsorbed state.

3. Protein Adsorption Kinetics Experiments Using TIRF

Before a protein adsorption measurement is started, the sensitivity of the TIRF setup is calibrated using three tryptophan solutions with increasing concentrations, thus providing the value for ΔSt/Δ(ctεt) in Eq. (9). After the cell is rinsed with water and the last tryptophan solution is removed, the cell is filled with a buffer solution and the background signal intensity at the relevant emission wavelengths are recorded. Protein solutions flow through the cell at a desired flow rate. The adsorption kinetics are followed by monitoring the fluorescence signal at the emission wavelengths for a desired period of time. In the case of intrinsic protein fluorescence the emission wavelength is typically recorded at 340 nm. The fluorescence signal during the desorption part of the experiment is followed for a desired period of time while a buffer solution is flowing through the cell. The adsorption–desorption cycle is then repeated with another protein concentration using either the same or a pristine adsorbent surface.

4. Fluorescence Emission Spectra and Quenching Experiments

In addition to providing information about Γp, the fluorescence emission from adsorbed protein can also be interpreted with respect to the conformation of adsorbed molecules by examining the fluorescence emission spectra and studying the solvent accessibility of the fluorophore in the protein by fluorescence quenching experiments. With the protein molecules still adsorbed on the surface, the fluorescence emission intensity is recorded as a function of the emission wavelength. The wavelength of maximum fluorescence intensity depends on the energy dissipation between excitation and emission of the fluorophore. Fluorescence emission spectra of the tryptophanyl residue in proteins are very sensitive to the polarity of its local surrounding. Usually, a more polar local environment results in a larger energy dissipation of the excited state and thus in a red-shifted emission maximum wavelength. A tryptophanyl residue surrounded by water has an emission maximum at 348 nm, whereas the tryptophanyl fluorescence maximum inside protein structures varies from 308 nm for azurin to 352 nm for glucagon.30 The shift in the emission maximum wave-length is sometimes difficult to interpret because a change in the local environment of the fluorophore can alter the duration between excitation and emission as well as the amount of energy dissipation per time unit. Nevertheless, fluorescence emission differences between solution and adsorbed protein can be used as an indication for structural changes in the local surrounding of the fluorescent reporter group.8

Quenching of fluorescence occurs when a quencher collides with the excited fluorophore group, thereby adsorbing the energy of the excited state. As quenching occurs on molecular contact between the quencher and the fluorescent group, this process yields information on the accessibility of fluorophores for the quencher and, hence, about the permeability of protein molecule. A large amount of organic or inorganic molecules can act as quenchers.30 One should take into account that the action of charged quenchers is also affected by electrostatic interactions. Collisional quenching of fluorescence is described by the Stern–Volmer equation:

| (10) |

where Fo and F are the fluorescence intensities in the absence and presence of quencher, respectively, Q is the concentration of the quencher, and K the Stern–Volmer quenching constant. By plotting the ratio Fo/F against the concentration of the quencher, a linear relation should be obtained for collisional quenching, and the Stern–Volmer quenching constant, K, indicates how accessible the fluorophore is. The quenching experiment is performed by injecting buffer solutions with increasing concentrations of the quencher while measuring the fluorescence intensity at the maximum emission wavelength. The adsorbed protein quenching is compared with the quenching of the same protein in bulk solution or at some other standard conditions. As desorption of proteins from the surface might occur, the fluorescence intensity of the sample without the presence of a quencher in the buffer solution is measured between the quenched fluorescence intensity measurements.

References

- 1.Andrade JD. In: Surface and Interfacial Aspects of Biomedical Polymers. 2. Protein Adsorption. Andrade JD, editor. New York: Plenum Press; 1985. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrade JD, Hlady V. Adv. Polym. Sci. 1986;79:1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malmsten M, editor. Biopolymer at Interfaces. New York: Dekker; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brash JL, Wojciechowski PW, editors. Interfacial Phenomena and Bioproducts. New York: Dekker; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Branden C, Tooze J. Introduction to Protein Structure. New York: Garland Publishing; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haynes CA, Norde W. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1995;169:313. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hlady V, Buijs J. In: Biopolymer at Interfaces. Malmsten M, editor. New York: Dekker; 1998. p. 181. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buijs J, Hlady V. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997;190:171. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1997.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang I-N, Herron JN. Langmuir. 1995;11:2083. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramsden JJ. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1993;27:41. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500002900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jennissen HP. In: Surface and Interracial Aspects of Biomedical Polymers. Andrade JD, editor. Vol. 2. New York: Plenum Press; 1985. p. 295. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jennissen HP. Biochemistry. 1976;15:5683. doi: 10.1021/bi00671a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jennissen HP. Hoppe-Seyler’s Z. Physiol. Chem. 1976;359:1201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jennissen HP. J. Chromatogr. 1979;159:71. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)98547-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jennissen HP. Makromol. Chem., Macromol. Syrup. 1988;17:111. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jennissen HP, Botzet G. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1979;1:171. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jennissen HP. J. Chromatogr. 1981;215:73. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jennissen HP, Botzet G. J. Mol. Recogn. 1993;6:117. doi: 10.1002/jmr.300060304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jennissen HP. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 1981;19:377. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(81)90025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuypers PA, Willems GM, Hemker HC, Hermens WT. Makromol. Chem. Macromol. Syrnp. 1988;17:155. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaiken IM. J. Chromatogr. 1986;376:11. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)80821-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hlady V, Furedi-Milhofer H. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1979;69:460. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jennissen HP. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1986;111:570. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson HG. A User’s Guide to Ellipsometry. San Diego: Academic Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaaf P, Dejardin P, Schmitt A. Langmuir. 1987;3:3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies J, editor. Surface Analytical Techniques for Probing Biomaterial Processes. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cuypers PA. Ph.D. Thesis. Limburg: Rijksuniversiteit Limburg; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuypers PA, Willems GM, Hemker HC, Hermens WT. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1987;516:224. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb33045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malmsten M. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1995;172:106. [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Myszka DG, Wood SJ, Biere AL. Methods in Enzymology. 1999;309(25) doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)09027-8. (this volume) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. New York: Plenum Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Demchenko AP. In: Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Lakowicz JR, editor. Vol. 3. New York: Plenum Press; 1992. p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Axelrod D, Burghardt TP, Thompson NL. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng. 1984;13:247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.13.060184.001335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hlady V, Van Wagenen RA, Andrade JD. In: Surface and Interracial Aspects of Biomedical Polymers. Andrade JD, editor. Vol. 2. New York: Plenum Press; 1985. p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson NL, Burghardt TP, Axelrod D. Biophys. J. 1981;33:435. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(81)84905-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lok BK, Cheng Y-L, Robertson CR. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1983;91:104. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elliott M, Ambrose EJ. Nature. 1950;165:921. doi: 10.1038/165921a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levitt M, Greer J. J. Mol. Biol. 1977;114:181. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90207-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leiniger RI, Fink DJ, Gendreau RM, Hutson TM, Jakobsen RJ. Trans. Am. Artif. Intern. Organs. 1983;29:152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chittur KK, Fink DJ, Leininger RI, Hutson TB. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1986;11:419. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fink DJ, Hutson TB, Chittur KK, Gendreau RM. Anal. Biochem. 1987;165:147. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeon JS, Sperline RP, Raghavan S. Appl. Spectrosc. 1992;46:1644. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buijs J, Norde W, Lichtenbelt JWT. Langmuir. 1996;12:1605. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng S-S, Chittur KK, Sukenik CN, Culp LA, Lewandowska K. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1994;162:135. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Müller M, Werner C, Grundke K, Eichhorn KJ, Jacobash HJ. Mikrochim. Acta. 1997;14:671. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ball A, Jones RAL. Langmuir. 1995;11:3542. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bauer HH, Muller M, Goette J, Merkle HP, Fringeli UP. Biochemistry. 1994;33:12276. doi: 10.1021/bi00206a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ho C-H, Britt DW, Hlady V. J. Mol. Recogn. 1996;9:444. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1352(199634/12)9:5/6<444::aid-jmr281>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Macklin JJ, Trautman JK, Harris TD, Brus LE. Science. 1996;272:255. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tollefen DM, Feagler JR, Majerus PWJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1971;246:2646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McFarlane AS. J. Clin. Invest. 1963;42:346. doi: 10.1172/JCI104721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ardaillou N, Larrieu MJ. Thrombosis Res. 1974;5:327. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(74)90171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haeberli A. Human Protein Data. Weinheim: VCH Verlags; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hlady V, Reinecke DR, Andrade JD. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1986;11:555. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haugland RP. Handbook of Fluorescent Probes and Research Chemicals. 5th ed. Eugene, OR: Molecular Probes; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coons AM, Crech HJ, Jones RN, Berliner EJ. J. Immunol. 1942;45:159. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Andrade JD, Smith LM, Gregonis DE. In: Surface and Interfacial Aspects of Biomedical Polymers. Andrade JD, editor. Vol. 1. New York: Plenum Press; 1985. p. 249. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hermanson GT. Bioconjugate Techniques. San Diego: Academic Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hermanson GT, Mallia AK, Smith PK. Immobilized Affinity Ligand Techniques. San Diego: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wong SS. Chemistry of Protein Conjugations and Cross-Linking. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. J. Biol. Chem. 195l;193:265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jennissen HP, Heilmeyer LMG., Jr Biochemistry. 1975;147:754. doi: 10.1021/bi00675a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jennissen HP, Demirolgou A. J. Chromatogr. 1992;597:93. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(92)80099-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hahn E. Am. Lab. 1983 July;:64. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lin Y-S, Hlady V, Janatova J. Biomaterials. 1992;13:61. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(92)90100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.The so-called “gradient” surface was originally designed as an experimental tool to investigate the effect of protein-binding residue surface density in a single protein adsorption experiment.66 In Fig. 1, [125I]LDL adsorption onto an octadecyldimethylsilyl (C18)-silica gradient surface is shown: approximately one-half of the silica plate is fully covered with C18 residues and the other half of the silica plate is left unmodified with a short gradient of C18 chain surface density in between the two halves.

- 66.Elwing H, Welin S, Askendahl A, Nilsson U, Lundström I. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1987;119:203. [Google Scholar]