Abstract

BACKGROUND

The aims of the study were to identify pathways from parent marijuana use to child problem behavior and parent-child relationships, and to evaluate whether effects of an earlier prevention program delivered to parents when they themselves were early adolescents would have a protective effect on these relationships one generation later.

METHODS

Structural equation models were applied to the data of a second generation study of a drug abuse prevention trial. Models assessed whether there were sustained marijuana prevention effects on adults who had at least one school-age child at the end of the emerging adulthood period (age 26, N=257), and whether these effects mediated subsequent parent-child relationships and child impulsivity when parents were between the ages of 28 and 34.

RESULTS

Participants originally assigned to the program group used significantly less marijuana in early adulthood than did controls. In turn, parental marijuana use was positively related to child impulsivity and negatively to parental warmth, but not significantly related to parental aggression.

CONCLUSIONS

Results suggest both a direct relationship from parental marijuana use to child impulsivity, as well as indirect relationships through parent-child interactions. Results also strongly support a role for early adolescent prevention programs for drug use, both for participants’ own long-term benefit, as well as for the benefit of their future children.

Keywords: Marijuana, Impulsivity, Prevention, Parent-Child Relationships, Intergenerational

1. Introduction

Internationally, marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004; Smart and Ogborne, 2000). This is of substantial public health concern due in large part to the significant negative psychosocial consequences, as well as increased susceptibility to chronic pulmonary problems and cancers of the head, neck, and lung, that occur later in life as a result of use (Chacko et al., 2006; Mehra et al., 2006). Marijuana use that persists into adulthood is of additional concern due to a well-established link between parents’ substance use and negative outcomes among their children. Much of this research on the intergenerational transmission of problem behavior connects family history of substance use to the development of child substance use problems (Brook et al., 1990; Chassin et al., 1996; Giancola and Parker, 2001; Hoffmann and Su, 1998; Jacob and Leonard, 1994; Hopfer et al., 2003; Orford and Velleman, 1990; Schuckit and Smith, 1996, 2000; Windle, 2000).

Studies have also demonstrated associations among parental substance use and other child outcomes including physical, cognitive, academic, and social-emotional adjustment (Conners et al., 2004; Hawkins et al., 1992). Here, much of the focus has been on parent alcohol abuse and child behavior problems (Cuijpers et al., 1999; Elkins et al., 2004; Finn et al., 1997; Haugland, 2003; Jansen et al., 1995; Malone et al., 2002; Pihl and Bruce, 1995; Sher, 1997; West and Prinz, 1987). However, less consistent are findings regarding the link between parent illicit drug use and youth behavioral adjustment, with inconsistencies potentially due to heterogeneity of the substances under investigation (Fals-Stewart et al., 2004; Stanger et al., 1999).

A small number of studies have focused on parental use of marijuana and child social and behavioral development. Here, some have focused on links between prenatal exposure to marijuana and future child adjustment (Day et al., 2006; Leech et al., 2006; Wills et al., 1994) where others have demonstrated associations between postnatal parental marijuana use and the intergenerational transmission of angry behavior, temper tantrums, negative mood, and self-esteem problems (Brook et al., 2007; Brook et al., 2002). Given that marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004), clarifying the negative impacts of parental use on children is critical to understanding the perpetuation and potential prevention of inter-generational behavior problems.

Since inter-generational problems appear to accrue from drug use, it is logical to continue to elucidate the mechanisms through which these problems are transmitted and whether early prevention efforts, particularly those that focus on drug use in the parent, can alter the trajectory of child behavior problems (Brook et al., 2007). Among the mechanisms through which problem behavior may be transmitted from parent to child are direct links from parent drug use and their children’s adjustment. The predictive relationship is assumed to operate as either a modeling effect of negative behavior or an inability to function adequately as a parent when misusing drugs. One study reported that mothers with drug problems were more likely to be emotionally disengaged and unresponsive with their children compared to non-drug-using mothers, suggesting a behavioral modeling effect (Gottwald and Thurman 1994).

Alternatively, parent drug use may affect personal characteristics including greater tolerance for deviance and/or negative parent-child relationship (Wills, Schreibman et al., 1994). Kandel (1990) demonstrated a significant negative relationship between the severity of drug problems and the quality of relationships (less child supervision, more punitive discipline, less positive involvement with the child) between parents and their children aged 6 and over. Negative parent-child relationships, in turn, could potentially influence child behavior. For example, parental permissiveness has been linked to low child self-regulation (Patock-Peckham et al., 2001), and parental aggression (i.e., corporal punishment) has been linked to poor emotional and behavioral adjustment, particularly for those children who did not experience a warm and supportive family environment (Aucoin et al., 2006).

Child impulsivity is one important domain of behavioral development that has received recent research attention. Child impulsivity has been associated with the development of multiple social, emotional, and behavioral problems (Lynam, 1996; Newman and Wallace, 1993; Wills, Vaccaro et al., 1994). Impulsivity, or, conversely, impulse control, is a heterogeneous construct generally thought to be comprised of disinhibition, novelty seeking, (lack of) premeditation, sensation seeking, and (lack of) perseverance (Depue and Collins, 1999; Whiteside and Lynam, 2001; Zukerman, 1994). It is also among the diagnostic criteria for a wide array of disorders, including antisocial disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, borderline personality disorder, bulimia nervosa, dementia, mania, and substance use disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Thus, it appears that impulsivity contributes to a diverse range of behavior problems that may appear in childhood and extend into adulthood.

Findings from studies on intergenerational relationships between parental substance use, parent-child relationships, and child behavior suggest at least two avenues in need of study (Brook et al., 2007). One is to determine how far back the parental substance use behavior represents a predictor of future parental and child behavior. The other is whether early preventive interventions delivered to parents before they were parents can disrupt intergenerational transmission of problem behavior. Thus, the current study had two aims. The first was to elucidate whether the pathway to child problems directly occurred through parent drug use, or whether the pathway was more indirect, from drug use to parent-child relationship, to child impulsivity. The second was to evaluate whether effects of an earlier prevention program on parents when they themselves were early adolescents, could have an impact on this relationship. To this end we developed and tested a structural model in which early intervention in adolescence (ages 12 and 13) was predictive of lower marijuana use as parents in early adulthood (age 26). In turn, it was hypothesized that marijuana use among parents was negatively related to parental warmth, positively related to parental aggression and rejection, and positively related to impulsive behavior in their children when parents were between the ages of 28 to 34. Finally, it was hypothesized that there would be a significant indirect effect of the intervention on child impulsivity and parent-child relationship through its effects on marijuana use in early adulthood.

2. Method

2.1. Research and measurement designs

Data for this study were collected as part of a long-term follow-up of a large drug abuse prevention trial (the Midwestern Prevention Project, MPP) that was initiated in Kansas City, Missouri in 1984 and Indianapolis, Indiana in 1987 (Johnson et al., 1990; Pentz et al., 1989). The data for this study were derived from a panel of students who represented 96% of enrolled students in eight middle schools in Kansas City. The pool of schools was selected for the panel on the basis of clear feeder patterns to high school and administrators’ willingness to change existing school schedules, given that the study began after the school year had started and educational planning was already in place. Eight schools from this pool, which represented all middle schools (four in a grade 6–8 configuration, four in a grade 7–9 configuration) in two of 15 school districts, were demographically matched by school configuration, feeder patterns, and demographic characteristics in pairs and then randomly assigned to a program or delayed program (control) condition. Students in the entering grade (6 or 7) served as the panel. All students in program schools received a multi-component, community-based drug prevention program, STAR, which was implemented during the first 5 years and ended when students graduated from high school. Details of research methods and intervention are described elsewhere (Johnson et al., 1990; Pentz et al., 1989). STAR is a nationally recognized evidence-based program for substance abuse prevention (Mihalic et al., 2001).

Students were measured at baseline, 6 months, annual follow-ups through high school, and every 18 months thereafter. The longitudinal measurement design for this study included 16 waves of data collection across four theoretically distinct developmental periods over 18 years, from ages 12 through 30. The first three waves of data constituted middle school/junior high. These time points included a 6th/7th-grade pretest (depending upon when participants began participation), 6th/7th-grade posttest, and 7th/8th-grade 1-year follow-up. The next four waves of data collection represented high school. These time points included 8th/9th-, 9th/10th-, 10th/11th-, and 11th/12th-grade follow-ups. Participants were then followed up when they were approximately 19, 20, 21, 22, and 24 years of age. These five time points represent the period of emerging adulthood when many young adults are attending college or initiating a career (Arnett, 2006). Finally, participants were surveyed at ages 26, 27, 28–30 and 30–34. These four time points represent early adulthood.

2.2. Adult Follow-up Sample

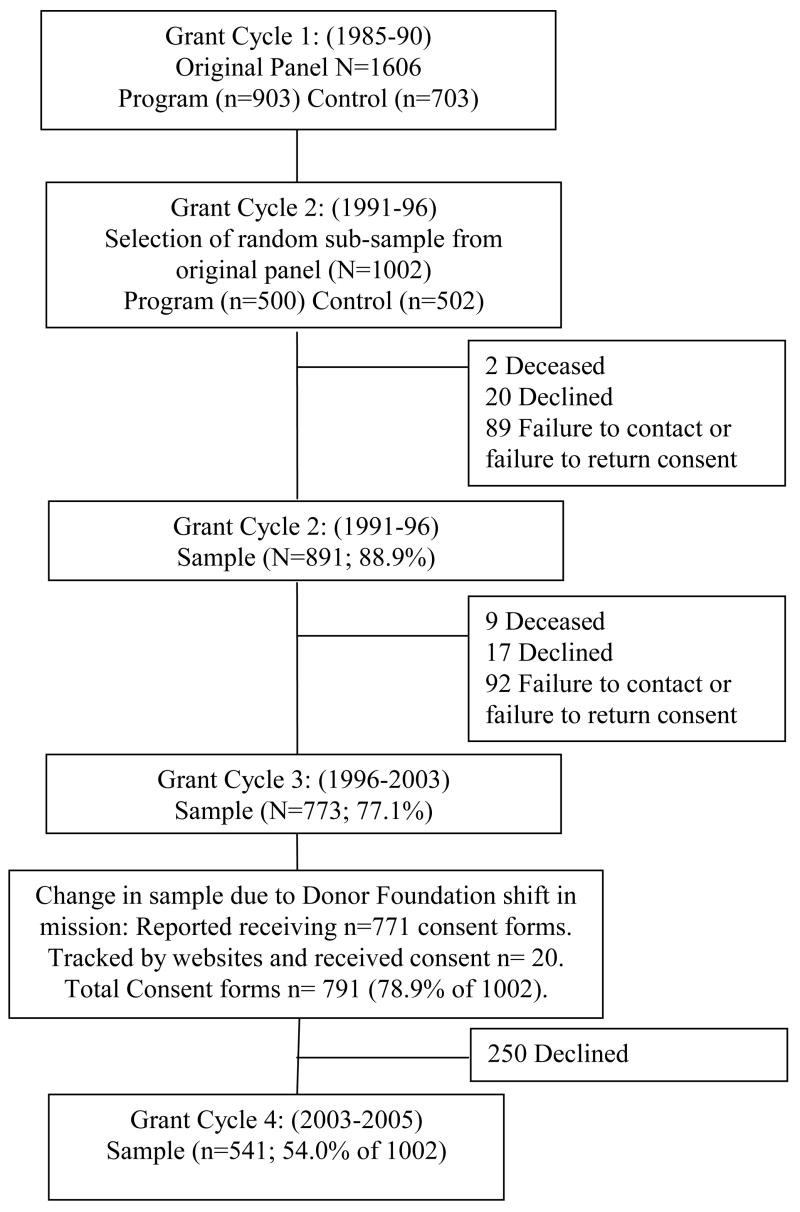

Details of samples for this study have been reported previously, both for the original sample of 50 schools (e.g., Pentz et al., 1989), as well as for the original panel of 1,606 that was imbedded in the 50 schools and followed through the end of high school (Johnson et al., 1990). All participants attended public schools. Demographic characteristics of the panel were representative of the population in the Kansas City area at the initiation of the study in 1984 (Johnson et al., 1990; Bureau of Census, 1983). Previous reports of this sample have shown no differences in demographic characteristics or by experimental group at baseline, with the exception that there were more 7th graders in the program group than in the control group, reflecting natural variations in school and grade size (Pentz et al., 1989). Figure 1 illustrates the history of the MPP project.

Figure 1.

Consort table representing the history of the MPP adult follow-up sample.

At the beginning of each grant cycle, participants were re-consented. By design, 1,002 (500 intervention and 502 control) of the original 1,606 participants were randomly selected for the next cycle for follow-up into adulthood. The target sample size of approximately 1,000 was determined by power calculations (estimating maintenance of a 10% net effect and effect size of .80) and budget considerations for tracking costs. Three major criteria were used to generate the adult follow-up sample: 1) at least one complete survey measurement in each developmental period leading up to the adult follow-up (baseline, and at least one in middle school, and one in high school); 2) weighting so that initial panel representation of race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and original school of origin was retained; and 3) equal sample sizes for program and control groups.

In the second five year cycle of follow-up into adulthood, 891 of 1002 randomly selected participants, or 88.9%, of the panel was retained (of the remainder, 2 were deceased, 20 or 2% declined to continue assessment, and 89 or 8.9% were equally distributed between failure to contact and failure to turn in surveys after 4 attempts). Data regarding those who were randomly selected and who declined to participate are no longer available. In the next five year follow-up period, 773 or 77.1% of the original panel participated (of the remaining 229, 11 total were deceased, 37 total declined to continue assessment, and 181 were unable to be contacted or failed to turn in surveys after four attempts).

In the fourth and final cycle, a shift in mission of the original data collection contractor required that USC absorb data collection responsibilities. By prior arrangement, under the terms of a U.S. Certificate of Confidentiality and a legal agreement required by the contractor, the contractor did not release information for follow-up to USC, but mailed a one-time general letter and new consent form to participants requesting that they contact USC directly themselves. The letter was sent to 791 individuals with last known contact information before the contractor closed operations. Of these, 250 or 31.6% declined to continue measurement under new arrangements or did not respond, and the remainder returned consents to continue participation under new data collector arrangements.

This process reduced the pool of participants to 541, which represents 68.4% of those contacted, or 54.0% of the original tracked panel of 1,002. Of these 541, 257 (47.5%) reported having index children at least 3 years of age during either the 2000–2003 or 2003–2005 waves of data collection and responded to the supplemental parental-report surveys of child behavior. It is these participants that make up the current sample. We chose a minimum age of three for index children based on the age at which impulse control has been shown to be an important determinant of school readiness (Blair, 2002), as well as the age standardization of the measures used. Of the 257 index children (control = 126, intervention = 131), 52.1% were female (control = 55.6%, intervention = 48.9%) and the mean age was 6.92 years (control = 7.36, intervention 6.50). All procedures were approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board.

2.3. Intervention Components

The MPP is a comprehensive, multi-faceted (school program, parent program, community organization, health policy, and mass media) program for adolescent drug use prevention. A comprehensive description of the MPP is provided in previous studies and in Blueprints, a manual for model programs (Mihalic et al., 2001). Two of the components, the school program and the parent program, focused directly on youth. The school program focused directly on teaching adolescents skills in decision-making, peer pressure avoidance, correction of perceived social norms, and friendship choice related to prevention of drug use. The parent program focused on developing positive parent-child communication, rule and norm setting, monitoring, and support of prevention practices related to drug use prevention. Previous studies demonstrated program effects on long-term prevention of marijuana use in adolescents, and promoting parent-child communication and support skills in parents (Pentz et al., 1989; Riggs et al., 2006).

2.4. Measures

As part of the long-term follow-up of the study, parents were asked to respond to mailed surveys of their health behavior. Among the questions asked at every wave were items asking about substance use. Marijuana use items (2 items; frequency of marijuana use in the past month and week) were on a 7-point scale with 0 = never, 1 = one time, 2 = 2–4 times, 3 = 5–10 times, 4 = 11–20 times, 5 = 21–100 times, and 6 = more than 100 times, and were based on two national drug use surveys (Johnston et al., 2004; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1999).

Beginning in the last two waves of data collection (2000–2003 and 2003–2005), participants completed supplemental surveys that assessed the health behavior of their index child 3 years of age or older. Child impulsivity items were drawn from the parent self-report version of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach and Edelbrock, 1983) and the Conners’ Rating Scales (Conners et al., 1998). Factor analyses demonstrated that eight items loaded on an impulsivity factor with loadings greater than .40 for only that factor (e.g., is always “on the go” or acts as if driven by a motor, hard to control, runs about or climbs excessively, excitable/impulsive, distractible, short attention span). Items in these scales were on a 4-point Likert scale with responses ranging from “Not True at All” to “Very Much True.”

Items assessing parent-child relationship were adapted from the short form of the Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire (PARQ; Rohner et al., 1991). This version of the PARQ consists of 15 items scaled from 1 (almost never true) to 4 (almost always true). Factor analyses on these items yielded three factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and for which item loadings for each item were greater than .40 for only one factor. These three factors corresponded to three of the five scales from the original PARQ: 1) Parental Warmth (5 items, e.g. feel close to my child, make it easy for my child to confide in me), 2) Parental Aggression (2 items, hurt my child’s feelings, punish my child when I am angry), 3) Parental Rejection (3 items, e.g. my child is a burden to me, I resent my child).

2.5. Data analytic strategy

The design of the structural model being tested included four waves of data collection. First, parents’ weekly and monthly marijuana use, gender, ethnicity, and intervention condition were assessed at baseline. Parents’ marijuana use was then reassessed at age 26, the first wave of data collection in early adulthood. Finally, parents completed a supplemental survey beginning in the last two waves of data collection (ages 28–34). In the cases where parents completed surveys for their child at both waves, only data from the first wave were assessed.

Previous studies of missingness and attrition in this data set have shown that while there have been slight decreases in representation of African-Americans, males, and cigarette users over time, there have been no interactions with experimental group (e.g. Fan et al., 2002). For this study, analyses of attrition and missingness were conducted at critical points in our evaluation design. First, baseline descriptive comparisons were made between the tracked (n = 1,002) and non-tracked (n = 604) participants. Second, among the 1,002 tracked participants, baseline descriptive statistics were conducted for those participants who did (n=257) and did not (n = 745) complete parent surveys. Third, among the 1,002 tracked participants, baseline comparisons were conducted between the 541 (54.0 %) participants who consented following the shift in original data collection contractor mission versus those 461 (46.0%) who did not. Finally, among the 541 participants who consented, comparisons were made between those 257 (47.5%) participants who completed child surveys at either the 2000–2003 or 2003–2005 waves, and those 284 (52.5%) who did not.

In addition, comparisons were made between participants who agreed to follow-up in grant cycle 4 and participants who declined further participation. First, a general linear model (Proc GLM; SAS Institute, 2005) controlling for gender, grade, and ethnicity compared those participants who consented and those who declined to consent on baseline weekly and monthly marijuana use. Then, a general linear model controlling for gender, grade, ethnicity, and baseline marijuana use, compared those participants who consented and those who declined to consent on weekly and monthly marijuana use in emerging adulthood. Consent by intervention condition interaction terms were also entered into these models in order to determine whether any relationship between consent status and marijuana use differed by intervention condition. These analyses allow for the determination of whether those who consented to grant cycle 4 follow-up were less likely to use marijuana at baseline and in emerging adulthood (representing differences in intervention effect). A logistic regression (Proc Logistic; SAS Institute, 2005) model was then used to determine whether those who provided cycle 4 consent differed in marital status from those who did not. These analyses allow for the determination of whether those who consented were more likely to be married and potentially more likely to have children.

Final comparisons were conducted to assess whether involvement in the STAR Program may have influenced other important variables that, in turn, could have been influencing parenting practices. The first utilized general linear models (Proc GLM; SAS Institute, 2005), controlling for gender, grade, ethnicity, and baseline marijuana use, to test whether those participants who eventually became parents demonstrated lower rates of weekly or monthly marijuana use in emerging adulthood (prior to completing parent surveys) than those who remained non-parents. Parental status by intervention condition interaction terms were entered into the model in order to determine whether any relationship between parental status and marijuana use differed by intervention condition. These analyses allow the determination of whether those who eventually became parents were less likely to use marijuana, and whether this differed by intervention condition. The second comparison utilized logistic regression (Proc Logistic; SAS Institute, 2005) to determine if intervention condition influenced marital status, which may, in turn, have influenced the likelihood of having a child.

Main study analyses proceeded in two steps. First, a measurement model was constructed in which all variables were allowed to correlate. Standardized regression weights provided indicators of latent constructs for marijuana use (weekly and monthly use items from the main survey), and impulsivity and parent-child relationships (items from the parent supplemental survey). Second, a structural model was constructed based on results from the measurement model. Indicators of latent constructs were retained for the structural model if their factor loadings were greater than .35. Both the measurement and structural models were evaluated with the structural equation modeling approach using AMOS 5.0 (Arbuckle, 2003), with full information maximum-likelihood (FIML) missing data imputation.

3. Results

3.1. Analyses of Participant Characteristics by Missingness and Attrition

Analyses of participant characteristics by missingness and attrition demonstrated some differences between the tracked (n = 1,002) and non-tracked (n = 604) participants. There were significant differences in baseline weekly and monthly marijuana use such that the tracked participants (Weekly X = .09, SD = .02; Monthly X = .10, SD = .02) used significantly less (Weekly, F = 6.28, p < .05; Monthly, F = 8.13, p < .01) marijuana at baseline than did non-tracked participants (Weekly X = .15, SD = .02; Monthly X = .18, SD = .03). Intervention condition by tracked versus non-tracked participant interactions (Weekly, F = 3.12, p < .10; Monthly, F = 3.86, p < .05) indicate that these differences were due to the tracked control participants using significantly less marijuana (Weekly X = .07, SD = .02; Monthly X = .07, SD = .03) at baseline than non-tracked control participants (Weekly X = .16, SD = .03; Monthly X = .21, SD = .04). Tracked intervention participants (Weekly X = .11, SD = .02; Monthly X = .13, SD = .03) did not demonstrate significant differences in marijuana use compared to non-tracked intervention participants (Weekly X = .13, SD = .02; Monthly X = .16, SD = .03). Baseline differences in marijuana use by tracked versus non-tracked participants is a finding consistent with other long-term drug use survey studies (e.g., Newcomb, 1997; Orlando et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2006) and reported previously for earlier waves on our study (Fan et al., 2002), although such differences have not been typically found by intervention and control groups.

Baseline descriptive statistics for participants who did (n=257) and did not (n = 745) complete parent surveys are listed in Table 1. Those who completed parent reports of child behavior were significantly more likely to be female for both the intervention and control conditions. Those in the control group who did not complete the parent survey were also more likely to be white than those in the control group who completed the survey. The two groups did not significantly differ in proportion of intervention/control membership or rates of baseline marijuana use.

Table 1.

Baseline sample descriptive statistics of those who did and did not complete parent surveys (total n = 1002).

| Completed Parent Survey n = 257(25.6%) | No Parent Survey n = 745(74.4%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention 131(51.0%) | Control 126(49.0%) | Intervention 369(49.5%) | Control 376(50.5%) | |

| Female (%) | 67.9 | 65.0 | 43.9*** | 44.9*** |

| White (%) | 88.5 | 71.4 | 85.6 | 80.3* |

| Weekly Use × (SE) | .13(.04) | .08(.03) | .12(.03) | .09(.02) |

| Monthly Use × (SE) | .17(.05) | .08(.03) | .15(.03) | .10(.03) |

Note: Marijuana means adjusted for sex and ethnicity; 0 = never used, 1 = used at least once.

= p < .001;

= p < .05.

Comparisons between the 541 (54.0 %) participants who re-consented for grant cycle 4, following the shift in original data collection contractor mission, versus those 461 (46.0%) who did not, demonstrated that re-consented participants were significantly (OR = 2.26; 95% CI = 1.75–2.91) more likely to be female (59.3%) than non-consented participants (39.3%). There were no significant differences in ethnic group participation, and no significant differences were reported in weekly or monthly marijuana use, or intervention condition.

Among the 541 participants who re-consented for grant cycle 4, comparisons were made between those 257 (47.5%) parents who completed child surveys at either the 2000–2003 or 2003–2005 waves, and those 284 (52.5%) who did not. These comparisons demonstrated that that re-consented participants who completed parent surveys were significantly more likely (OR = 1.78; 95% CI = 1.25–2.52) to be female (66.5%) than those re-consented participants who did not (52.8%). Again, there were no significant differences in ethnic group participation, reported weekly or monthly marijuana use, or intervention condition.

No significant differences appeared between those participants who re-consented to follow-up in grant cycle 4 and those who declined cycle 4 participation in either weekly (Consented; X = 0.08, SD = .02: Declined; X = 0.09, SD = .02) or monthly (Consented; X = 0.10, SD = .02: Declined; X = 0.10, SD = .03) marijuana use at baseline, or weekly (Consented; X = 1.30, SD = .06: Declined; X = 1.30, SD = .08) or monthly (Consented; X = 1.48, SD = .08: Declined; X = 1.52, SD = .10) marijuana use in emerging adulthood. In addition, there was no consent status by intervention condition interaction at baseline (Weekly: F = 0.62, p = n.s.; Monthly: F = 0.41, p = n.s.) or emerging adulthood (Weekly: F = 0.14, p = n.s.; Monthly: F = 0.54, p = n.s.). Consent status was not related to marital status (OR = 0.73; 95% CI = 0.49–1.09) and there was no consent status by intervention condition interaction effect. In total, these results suggest that the follow-up sample of 541 were not significantly different from the 250 who declined re-consent.

Finally, comparisons made in emerging adulthood between those participants who eventually became parents and those who did not become parents demonstrated no significant differences in weekly (parents; X = 1.30, SD = .05: non-parents; X = 1.34, SD = .09) or monthly (parents; X = 1.49, SD = .07: non-parents; X = 1.48, SD = .13) marijuana use in emerging adulthood. Furthermore, there was no significant parental status by intervention condition interaction. In addition, there were no significant differences between intervention and control conditions in parental status (OR = 0.71; 95% CI = 0.47–1.06), and no significant condition by parent status interaction emerged. Thus, it appears that those who had children were neither more likely to have been low users or better responders to the STAR intervention than adults with no index age children, nor were they more likely to be married. However, the power associated with the small size of this particular sub-sample rendered such differences difficult to detect.

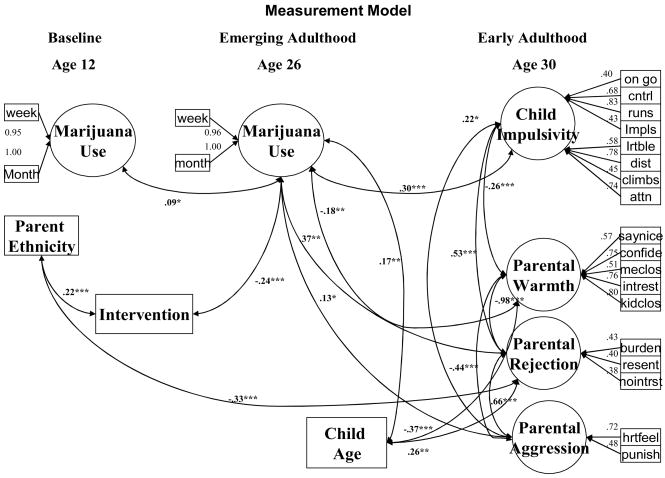

3.1. Measurement Model

Figure 2 (X2=411.2, df = 264; CFI = .940; RMSEA = .047) illustrates a measurement model. For the sake of clarity, only significant pathways at the p < .05 level are presented in Figure 2. Of the covariates, parent ethnicity was related to intervention condition such that there were more non-white participants in the intervention condition, and parent rejection such that non-white parents were less likely to report parental rejection of their child. Intervention condition was related to early adulthood marijuana use such that MPP participants used significantly less marijuana as adults. Baseline marijuana use was positively related to early adulthood marijuana use. Finally, early adulthood marijuana use was negatively related to parental warmth, and positively related to child age, parental aggression and rejection, as well as child impulsivity. Child age was positively correlated with parental rejection and negatively correlated with parental warmth. Finally, significant correlations were found among all three parent-child relationship styles and child impulsivity. Parental rejection and parental warmth were very highly correlated (−.98). Therefore, it appears that instead of loading on two separate factors representing parental warmth and rejection, these items represented a single higher order factor. Based on these results, warmth and rejection items were combined to form a single factor, termed parental warmth, with two indicators: a positively scaled score of warmth (5 items) and a negatively scaled score of rejection (3 items).

Figure 2.

Measurement model of baseline marijuana use to marijuana use in emerging adulthood to parent-child relationships and child impulsivity in early adulthood.

Note: Only Significant Paths Illustrated

N = 257, Chi-Square (264) = 411.2

CFI = .940, RMSEA = .047

*** = p < .001, ** = p < .01, *= p < .05.

Parent and Child Gender not significantly related to any variables in the model

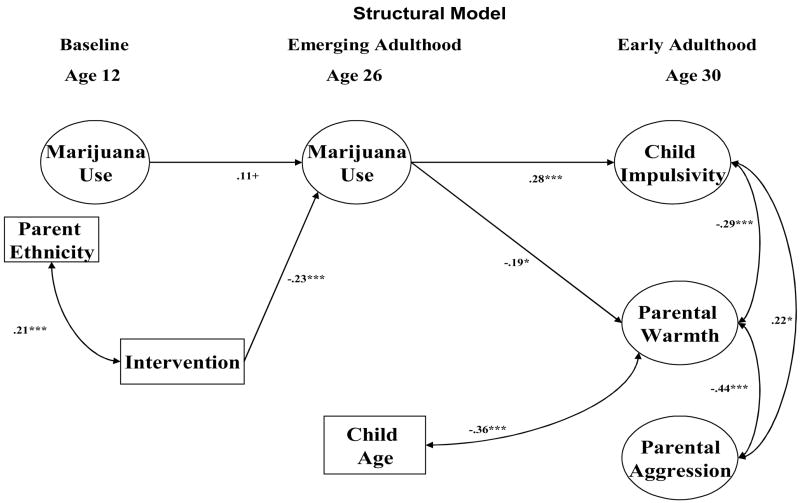

3.2. Hypothesized Structural Model

The structural model consists of all relations significant in the measurement model at the p < .05 level. Figure 3 (X2= 392.3, df = 258; CFI = .950; RMSEA = .045) demonstrates the results of the structural model. For the sake of clarity, only significant relationships are illustrated. The structural model demonstrated good fit (CFI ≥ .950, RMSEA < .05) and tested a) the direct effects of the MPP on marijuana use in the first wave of data collection in early adulthood while covarying for ethnicity and baseline marijuana use, and b) marijuana use in early adulthood on later parent-child relationship and child impulsivity. As hypothesized, and as can be seen in Figure 3, parents who participated in the MPP demonstrated significantly less marijuana use in the first year of early adulthood. Also as hypothesized, marijuana use in the first wave of early adulthood was related to parent reports of higher child impulsivity and lower parental warmth. Sobel test for indirect effects demonstrated a significant indirect effect of the MPP on child impulsivity (z = −2.80, p < .01) and on parent warmth (z = 2.06, p < .05).

Figure 3.

Direct effects model of baseline marijuana use to marijuana use in emerging adulthood to parent-child relationships and child impulsivity in early adulthood.

N = 257, Chi-Square (258) = 392.3

CFI = .950, RMSEA = .045

*** = p < .001, ** = p < .01, *= p < .05.

4. Discussion

This study follows recommendations from previous studies on the parent drug use-child behavior relationship that prevention effects should be examined for their potential to affect intergenerational behaviors. Although a number of prevention programs have demonstrated short-term change in marijuana use, few have demonstrated the ability to sustain these effects over time. In this study, intervention group differences at the commencement of early adulthood can be interpreted as the sustained impact of the MPP on adult marijuana use. Lower levels of marijuana use in early adulthood were then directly related to lower levels of impulsivity in parents’ children. Tests for indirect program effects on child impulsivity through parental marijuana use were also significant, suggesting that the MPP intervention contributed to lower levels of impulsivity in the children of original participants.

Lower levels of parental marijuana use were also positively related to a warm parent-child relationship and a significant indirect intervention effect was found for parental warmth through early adult marijuana use. In turn, parental warmth was negatively related to child impulsivity. Future studies with sufficient waves of child measurement might examine whether this pattern of results represents a sequential mediational relationship, whereby marijuana use affects later parental warmth, and parental warmth affects later lower child impulsivity (Pentz, 2004). There is already some epidemiological research to support these cross-generation temporal relationships (e.g., Brook et al., 1990).

The focus on early prevention efforts in adolescence is important due in part to patterns of adult (including parent) drug use often being resistant to change once established. Thus, efforts to treat adult users to benefit children might be expensive, time-consuming, and limited in effectiveness compared to other methods of intervention. Early prevention is also important due to parents’ key role as the primary socializing forces in the rapid social-emotional development that occurs early in the lives of their child. Study results suggest that parents who use marijuana may be less likely to be able to promote optimal development for reasons including emotional unavailability, negative parent-child relationships, and/or poor modeling behavior.

The current population-based study also supplements previous studies that typically focused on the links between substance use and child outcomes in clinical samples (Barnard and McKeganey, 2004). Although an area of significant research importance, a focus solely on clinical populations makes generalization to a broader population difficult. Further, previous research has focused primarily on intergenerational transmission of alcohol-related behavior (Griesler and Kandel, 1998; Hussong et al., 1998; Merline et al., 2004; Weiner et al., 2001), whereas the current study supports a role for parental marijuana use in the development of child impulsivity.

Relationships among marijuana use prevention, parent-child relationship, and youth impulsivity are also notable due to the important role that impulsivity plays in the development of serious problems later on in adolescence. Future investigations that track these youth into adolescence may prove informative in determining whether the more impulsive youth involved in the study are more likely to develop serious emotional (e.g. depression/anxiety) and/or behavioral (e.g. conduct or substance use) problems.

These results and implications should be considered in terms of study limitations. One is the size and demographic characteristics of the adult follow-up sample, which could conceivably affect population representativeness, external validity, and power to detect intervention differences. By design, sample size for long-term follow-up was determined by power estimates for maintenance of program effect, and constrained by the considerable costs of long-term follow-up of a panel. Power was predetermined on a sample of 1,002, but there was still sufficient power to detect program effects on marijuana use on the follow-up sample, although the sample size and skewness does not enable reliable comparisons across different sub-groups, including gender and ethnicity. Thus, results of this study could be considered generalizable to adults with children who are the typical respondents in longitudinal household studies of self and child health behavior. Similar panel sampling strategies have been used in other long-term substance use and health behavior studies (Hawkins et al., 2005; Orlando et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2006).

Second, as is the case with all longitudinal studies of this duration, there were some issues with data missingness, attrition, and differential rates of baseline marijuana use in the tracked vs. non-tracked control group, all of which can affect the internal validity of the study. By the last wave of the study, which was limited by lack of researcher access to participant information, study participants represented 54.0% of the original 1,002 tracked panel. However, several subgroup comparisons suggest that internal validity was not affected, and yielded few differences. One notable difference was that non-tracked participants showed less marijuana use at baseline compared to those who were in the final tracked sample. Since there were no such differences for the program group, the pattern of results suggests that if internal validity was somewhat affected, it would be in the direction of a Type II error, producing an underestimate of program effects, rather than an overestimate. It should be noted that the follow-up and retention rates in this study exceed those in similar long-term substance use epidemiology and prevention studies with similar survey methodologies (e.g., Hawkins et al., 2005, 57.4% from grade 5 to age 21; Orlando et al., 2005, 43.6% at 16 year follow-up, Spoth et al., 2004, 45.6% at 6 year follow-up, and Sun et al., 2006, 46.0% at 5 year follow-up). This can be compared to the present study follow-ups of 88.9%, 77.1%, and 54.0% at 10, 15, and 20 year follow-ups, respectively. Taken together, these findings suggest that the program effects can be considered relatively robust and internally valid.

Of additional note is that the sample became disproportionately female over time. However, it is unclear how parent gender might influence reports of parent-child relationships and child behavior. On the one hand, gender might affect perceptions and, therefore, reports of behavior. On the other hand, it is conceivable that since mothers may spend more time in child-rearing, interaction, and observation of their children, they may provide more reliable reports of parent-child relationships and behavior than others. These questions should receive more attention in future research.

A third limitation is that we were limited to evaluating parent-child relationships and child impulsivity within a single wave. Therefore, we could not assess the longitudinal nature of this association. Future research could extend this research, also with cross-lagged models, to help determine whether the drug use, parenting, and child problem behavior relationships are reciprocal over time.

A fourth consideration is whether the present study’s intervention findings on long-term marijuana use are unique, a question which could relate to external validity of prevention program effects, both in terms of this program’s replication, as well as effects of other prevention programs. At least two factors mitigate this possibility. One is that, while not part of this study, a planned replication conducted in Indianapolis has shown similar effects on marijuana use, suggesting that there is external validity to program replication (Chou et al., 1998). The second is that other prevention programs may not have had as long a follow-up as reported in this study or may have focused on other drug use outcomes. Thus, direct comparison of external validity to other prevention programs is more difficult. For example, long-term effects of one drug prevention study to age 21 showed dissipation of effects by age 21 (Orlando et al., 2005). Another study showed a non-significant trend toward maintenance of effects by age 21, however, the intervention in this case was a general competency intervention aimed at children (not adolescents) and outcomes were measured differently (Hawkins et al., 2005). Regardless, differences among studies highlight the need for more replication, with long-term follow-up, and more standard measures of drug use outcomes, including marijuana use.

Despite these limitations, the current study supports the implementation of evidence-based substance abuse prevention programs in early adolescence. Such programs may have long-term and collateral benefits of preventing drug use and related problem behaviors across generations of adolescents, their parents, adolescents as they become adults, and their own children. Future research should further examine whether these collateral benefits extend to the second generation of children whose prevented impulsivity may protect them against the development of drug use later on. Collateral benefits should also be examined in terms of whether child social and academic competencies are also altered from parents’ earlier prevention exposure. Finally, econometric analyses of the cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness of drug abuse prevention programs should include indices of collateral and cross-generational benefits.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Nathaniel R. Riggs, University of Southern California, Institute for Prevention Research, 1000 S. Fremont Ave., Unit #8, Alhambra, CA 91803, Email: nriggs@usc.edu, Phone: 626-457-6687

Mary Ann Pentz, University of Southern California, Institute for Prevention Research, 1000 S. Fremont Ave., Unit #8, Alhambra, CA 91803.

Chih-Ping Chou, University of Southern California, Institute for Prevention Research, 1000 S. Fremont Ave., Unit #8, Alhambra, CA 91803.

References

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: APA; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos 5.0 Update to the Amos User’s Guide. Smallwaters Corporation; Chicago IL: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: Understanding the new way of coming of age. In: Arnett JJ, Tanner JL, editors. Emerging Adults in America: coming of Age in the 21st Century. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2006. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Aucoin KJ, Frick PJ, Bodin SD. Corporal punishment and child adjustment. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2006;27:527–541. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard M, McKeganey N. The impact of parental problem drug use on children: what is the problem and what can be done to help? Addiction. 2004;99:552–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C. School readiness: integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of children’s functioning at school entry. Am Psychol. 2002;57:111–127. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, Gordon AS, Whiteman M, Cohen P. The psychosocial etiology of adolescent drug use: a family interactional approach. Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr. 1990;116 (Whole No. 2) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Ning Y, Balka EB, Brook DW, Lubliner EH, Rosenberg G. Grandmother and parent influences on child self-esteem. Pediatrics. 2007;119:444–451. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Zheng L. Intergenerational transmission of risks for problem behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2002;30:65–76. doi: 10.1023/a:1014283116104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Census, 1983. Census Tract Kansas City, MO-KS: Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area. US Dept. of Commerce Publication PHC 80–2–200; 1980 census of population and housing. [Google Scholar]

- Chacko JA, Heiner JG, Siu W, Macy M, Terris MK. Association between marijuana use and transitional cell carcinoma. Urology. 2006;67:100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Curran PJ, Hussong AM, Colder CR. The relation of parent alcoholism to adolescent substance use: a longitudinal follow-up study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:70–80. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou C-P, Montgomery SB, Pentz MA, Rohrbach LA, Johnson CA, Flay BR, MacKinnon D. Effects of a community-based prevention program on decreasing drug use in high risk adolescents. Am J Pub Health. 1998;88:944–948. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.6.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2003. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004;53(SS–2) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners NA, Bradley RH, Mansell LW, Liu JY, Roberts TJ, Brugdorf K, Herrell JM. Children of mothers with serious substance abuse problems: an accumulation of risks. Am J Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:85–100. doi: 10.1081/ada-120029867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK, Parker JD, Sitarenios G, Epstein JN. The revised Conners’ Parent Rating Scale (CPRS-R): factor structure, reliability, and criterion validity. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1998;26:257–268. doi: 10.1023/a:1022602400621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Langendoen Y, Bijl RV. Psychiatric disorders in adult children of problem drinkers: prevalence, first onset and comparison with other risk factors. Addiction. 1999;10:1489–1498. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.941014895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day NL, Goldschmidt L, Thomas CA. Prenatal marijuana exposure contributes to the prediction of marijuana use at age 14. Addiction. 2006;101:1313–1322. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Collins PF. Neurobiology of the structure of personality: dopamine, facilitation of incentive motivation, and extroversion. Behav Brain Sci. 1999;22:491–569. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99002046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins IJ, McGue M, Malone S, Iacono WG. The effect of parent alcohol and drug disorders on adolescent personality. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:670–676. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Kelley ML, Fincham FD, Golden J, Logsdon T. Emotional and behavioral problems of children living with drug-abusing fathers: comparisons with children living with alcohol-abusing and non-substance-abusing fathers. J Family Psychol. 2004;18:319–330. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan AZ, Pentz MA, Dwyer J, Bernstein K, Li C. Attrition in a longitudinal drug abuse prevention study. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2002;4:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Finn P, Sharkansky E, Viken R, West R, Sandy J, Befferd G. Heterogeneity in the families of sons of alcoholics: the impact of familial vulnerability type on offspring characteristics. J Abnorm Psychol. 1997;106:26–36. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesler PC, Kandel DB. The impact of maternal drinking during and after pregnancy on the drinking of adolescent offspring. J Stud Alcohol. 1998;59:292–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Parker AM. A six-year prospective study of pathways toward drug use in adolescent boys with and without a family history of a substance use disorder. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:166–178. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugland BS. Paternal alcohol abuse: Relationship between child adjustment, parent characteristics, and family functioning. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2003;34:127–146. doi: 10.1023/a:1027394024574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: implications for substance abuse prevention. Psych Bull. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Kosterman R, Catalano RF, Hill KG, Abbott RD. Promoting positive adult functioning through social development intervention in childhood: long-term effects from the Seattle Social Development Project. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:25–31. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JP, Su SS. Parent substance use disorder, mediating variables and adolescent drug use: a non-recursive model. Addiction. 1998;93:1351–1364. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93913516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopfer CJ, Stallings MC, Hewitt JK, Crowley TJ. Family transmission of marijuana use, abuse, and dependence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:834–841. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046874.56865.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Curran PJ, Chassin L. Pathways of risk for accelerated heavy alcohol use among adolescent children of alcoholic parents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1998;26:453–466. doi: 10.1023/a:1022699701996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Leonard K. Family and peer influences in the development of adolescent alcohol abuse. In: Zucker R, Boyd G, Howard J, editors. Development of Alcohol Problems: Exploring the Biopsychosocial Matrix of Risk (NIAAA Monograph No. 26) Bethesda, MD: NIAAA; 1994. pp. 123–156. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen RE, Fitzgerald HE, Ham HP, Zucker RA. Pathways into risk: temperament and behavior problems in three- to five-year-old sons of alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:501–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CA, Pentz MA, Weber MD, Dwyer JH, MacKinnon DP, Flay BR, Baer NA, Hansen WB. The relative effectiveness of comprehensive community programming for drug abuse prevention with risk and low risk adolescents. J Consult Clin Psych. 1990;58:4047–4056. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Secondary school students. NIH Publication No. 04-5507. I. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2004. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D. Parenting styles, drug use and children’s adjustment in families of young adults. J Marriage Fam. 1990;52:183–196. [Google Scholar]

- Leech SL, Larkby CA, Day R, Day NL. Predictors and correlates of high levels of depression and anxiety symptoms among children at age 10. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:223–230. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000184930.18552.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR. Early identification of chronic offenders: who is the fledgling psychopath? Psych Bull. 1996;120:209–234. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Drinks of the father: father’s maximum number of drinks consumed predicts externalizing disorders, substance use, and substance use disorders in preadolescent and adolescent offspring. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1823–1832. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000042222.59908.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehra R, Moore MR, Crothers K, Tetrault J, Fiellin DA. The association between marijuana smoking and lung cancer: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1359–1367. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.13.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merline AC, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Substance use among adults 35 years of age: prevalence, adulthood predictors, and impact of adolescent substance use. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:96–102. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalic S, Irwin K, Elliott D, Fagan A, Hansen D. Blueprints for Violence Prevention. Rockville, MD: Juvenile Justice Clearinghouse; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD. Psychosocial predictors and consequences of drug use: A developmental perspective within a prospective study. J Addict Dis. 1997;16:51–89. doi: 10.1300/J069v16n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman JP, Wallace JF. Divergent pathways to deficient self-regulation: implications for disinhibitory psychopathology in children. Clin Psychol Rev. 1993;13:699–720. [Google Scholar]

- Orford J, Velleman R. Offspring of parents with drinking problems: drinking and drug-taking as young adults. Br J Addict. 1990;85:779–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb01691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando M, Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Klein DJ. Concurrent use of alcohol and cigarettes from adolescence to young adulthood: An Examination of developmental trajectories and outcomes. Sub Use & Misuse. 2005;40:1051–1069. doi: 10.1081/JA-200030789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, Cheong J, Balhorn ME, Nagoshi CT. A social learning perspective: a model of parenting styles, self-regulation, perceived drinking control, and alcohol use problems. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1284–1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentz MA. Form follows function: designs for prevention effectiveness and diffusion research. Prev Sci. 2004;5:23–29. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013978.00943.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentz MA, Dwyer JH, MacKinnon DP, Flay BR, Hansen WB, Wang EI, Johnson CA. A multicommunity trial for primary prevention of adolescent drug abuse. JAMA. 1989;261:3259–3266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihl R, Bruce K. Cognitive impairment in children of alcoholics. Alcohol Health Res World. 1995;19:142–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottwald SR, Thurman SK. The effects of prenatal cocaine exposure on mother–infant interaction and infant arousal in the newborn period. Top Early Child Spec. 1994;14:217–231. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs NR, Elfenbaum P, Pentz MA. Parent program component analysis in a drug abuse prevention trial. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP, Saavedra JM, Granum EO. Handbook for the study of parental acceptance and rejection. Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut, Center for the Study of Parental Acceptance and Rejection; 1991. Parental acceptance–rejection questionnaire: test manual; pp. 17–48. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. SAS Statistical Software. 9.1. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C, Azevedo K. Brief family intervention effects on adolescent substance initiation: school-level growth curve analyses 6 years following baseline. J Consult & Clin Psych. 2004;72:535–542. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2003 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Publication No. SMA 04-3964. Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL. An 8-year follow-up of 450 sons of alcoholic and control subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;1157:1881–1883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030020005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL. The relationships of a family history of alcohol dependence, a low level of response to alcohol and six domains of life functioning to the development of AUD. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:827–835. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ. Psychological characteristics of children of alcoholics. Alcohol Health Res World. 1997;21:247–2545. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart RG, Ogborne AC. Drug use and drinking among students in 36 countries. Addict Behav. 2000;25:455–460. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanger C, Higgins ST, Bickel WK, Elk R, Grabowski J, Schmitz J, Amass L, Kirby KC, Seracini AM. Behavioral and emotional problems among children of cocaine- and opiate-dependent parents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:421–428. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199904000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Skara S, Sun P, Dent CW, Sussman Project Towards No Drug Abuse: Long-term substance use outcomes evaluation. Prev Med. 2006;42:188–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1998 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. 1999 Retrieved March 25, 2008 from http://ncadi.samhsa.gov/govstudy/bkd376/TableofContents.aspx.

- Weiner MD, Pentz MA, Turner GE, Dwyer JH. From early to late adolescence: alcohol use and anger relationships. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28:450–457. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00200-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MO, Prinz RJ. Parent alcoholism and childhood psychopathology. Psych Bull. 1987;102:204–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Pers Indiv Differ. 2001;30:669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Schreibman D, Benson G, Vaccaro D. Impact of parental substance use on adolescents: a test of a mediational model. J Pediatr Psychol. 1994;19:537–555. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/19.5.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Vaccaro D, McNamara G. Novelty seeking, risk taking, and related constructs as predictors of adolescent substance use: an application of Cloninger’s theory. J Subst Abuse. 1994;6:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. Parent, sibling, and peer influences on adolescent substance use and alcohol problems. Appl Dev Sci. 2000;4:98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]