Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To determine the risk of congenital cardiac abnormalities associated with use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) during pregnancy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS: We conducted a retrospective review of the medical records of all pregnant women presenting at Mayo Clinic's site in Rochester, MN, from January 1, 1993, to July 15, 2005, and identified 25,214 deliveries. A total of 808 mothers were treated with SSRIs at some point during their pregnancy. We reviewed the medical records of the newborns exposed to SSRIs during pregnancy to analyze their outcomes, specifically for congenital heart disease and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn.

RESULTS: Of the study patients, 808 (3.2%) took an SSRI at some point during the antenatal period. Of the 25,214 deliveries, 208 newborns (0.8%) were diagnosed as having congenital heart disease. Of the 808 women exposed to SSRI during pregnancy, 3 (0.4%) had congenital heart disease compared with 205 (0.8%) of the 24,406 women not exposed to an SSRI (P=.23). Of the total number of deliveries, 16 newborns were diagnosed as having persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn, none of whom had exposure to SSRIs (P>.99).

CONCLUSION: Our data are reassuring regarding the safety of using SSRIs during pregnancy.

Of the 808 women who took a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor during pregnancy, 3 (0.4%) had congenital heart disease; of the 25,214 deliveries, 208 newborns (0.8%) were diagnosed as having congenital heart disease; these findings reconfirm the safety of these drugs for pregnant women.

CHD = congenital heart disease; PPHN = persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; VSD = ventricular septal defect

Recent data indicate that approximately 10% to 15% of women will have depression at some point during pregnancy or the postpartum period.1,2 Untreated depression during pregnancy may lead to poor outcomes, including low birth weight, preterm delivery, or lower Apgar scores; poor prenatal care; failure to recognize or report signs of labor; and an increased risk of fetal abuse, neonaticide, or suicide.1,2 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the first-line pharmacotherapy for depression, and SSRI use during pregnancy has been well documented.

Overall, data regarding the use of SSRIs during pregnancy have been reassuring. Most studies3-9 have reported relatively consistent findings on the adverse effects of SSRI use during pregnancy, which include neonatal withdrawal syndrome, low birth weight, and preterm birth. Many studies10-12 have indicated no major fetal malformations higher than the baseline population risk of 1% to 3% with use of SSRIs during pregnancy. One study13 has indicated increased risks for specific defects, whereas another study14 noted an association between overall SSRI use during pregnancy and 3 distinct types of birth defects.

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is recognized in approximately 0.4% to 1% of all live births,15-17 and several studies have suggested that use of an SSRI, particularly paroxetine, may be associated with an increased risk of CHD. In particular, ventricular septal defects (VSDs) have been associated with use of paroxetine during the first trimester,18-22 although a recent meta-analysis23 that reviewed both previously published and unpublished data did not confirm this association. One report20 showed a dose response in neonates exposed to paroxetine during the first trimester; infants exposed to paroxetine at dosages greater than 25 mg/d had an increased risk of major malformation or major cardiac malformation, whereas those exposed to lower dosages had no increased risk above baseline. Finally, a recent report24 showed an increased risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) associated with late-pregnancy exposure to SSRIs.

Because recent reports have shown an increased risk of VSD and PPHN in neonates exposed to SSRIs in utero, we sought to determine whether use of SSRIs during the prenatal period was associated with CHD and PPHN.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

After Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approval, we conducted a retrospective cohort study examining all obstetric deliveries at Mayo Clinic's site in Rochester, MN, from January 1, 1993, to July 15, 2005. The Division of Obstetrics prospectively maintains an obstetric deliveries database that was used to aid with our medical record review. We identified 25,214 deliveries during that period.

Measurement of Exposures

Of the total number of deliveries, 808 mothers were prescribed SSRIs—fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram, and venlafaxine—at some point during their pregnancy. Venlafaxine, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, was included in this analysis because its mechanism of inhibition in the reuptake of serotonin is similar to that of SSRIs. The obstetric database listed the medications a woman took during her pregnancy. Each case was then confirmed by review of each individual medical record. Pregnant women with a documented medication list during their pregnancy that included an SSRI or who were given at least 1 SSRI prescription during their pregnancy were selected as the exposed group, whereas the remaining 24,406 women were considered unexposed.

Timing of the initial SSRI exposure was divided into the following categories: conception, discontinuation because of a positive pregnancy test result, first trimester, second trimester, and third trimester. Timing refers to when the mother and fetus were first exposed to the SSRI. Patients were placed into only 1 of these categories; for instance, if a woman had been taking an SSRI at conception but discontinued taking the drug when she learned of the pregnancy, she would be classified only in the discontinuation due to a positive pregnancy test result category. Trimesters were divided using standard obstetric classification: first trimester, 0 to 13 weeks; second trimester, 14 to 26 weeks; and third trimester, 27 weeks through delivery.

Measurement of Outcomes

Adverse effects assessed in this study were CHD, VSD, and PPHN. Congenital heart disease is defined as an abnormality in cardiocirculatory structure or function that is present at birth, even if it is discovered much later. A wide range of abnormalities and syndromes are included in this definition. A VSD is defined as a hole in the septum between the ventricles of the heart. Heart disease diagnosed immediately after birth and during the time before discharge home was included for this analysis. Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn is defined as failure of the normal circulatory transition that occurs after birth. This syndrome is characterized by marked pulmonary hypertension that causes hypoxemia and right-to-left extrapulmonary shunting of blood. By definition, PPHN is diagnosed postnatally.

Infant outcomes are listed as part of the obstetric database. The database was searched for any of these diagnoses and confirmed by individual medical record review.

Statistical Analyses

Characteristics of the study population were summarized using total number and percentages or medians and inter-quartile ranges, as appropriate. Median dosages of SSRIs by timing of prescription were compared using Kruskal-Wallis tests, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to determine whether dosage of the various SSRI prescriptions differed between preconception prescription dosages and dosages in the first or second and third trimesters. Fisher exact tests were used to determine whether the proportion of CHD outcomes differed between those who took SSRIs compared with those who did not. All analyses were conducted using JMP 7.0.1 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All tests were 2-sided, and P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

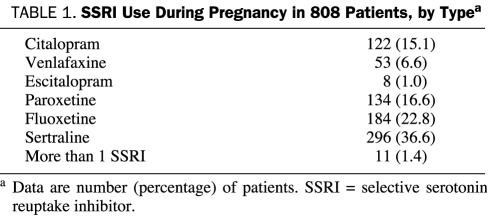

Sertraline was the most frequently prescribed SSRI (36.6% of all SSRI exposures), with fluoxetine, paroxetine, citalopram, venlafaxine, and escitalopram in declining order (Table 1). Of the 25,214 deliveries, 208 newborns were diagnosed as having CHD, a rate of 0.8%.

TABLE 1.

SSRI Use During Pregnancy in 808 Patients, by Typea

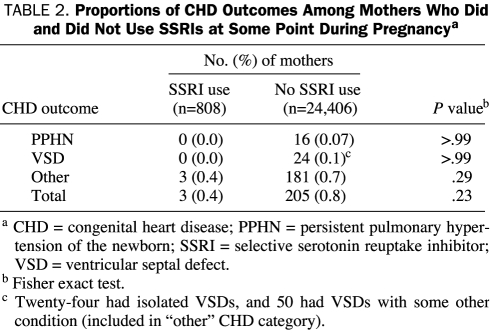

Only 3 of the 208 newborns who were diagnosed as having CHD had exposure to SSRIs in utero. The prevalence of CHD was similar in neonates born to mothers who used SSRIs at any point during their pregnancy (0.4%) compared with mothers who did not (0.8%; P=.23) (Table 2). Of the 25,214 deliveries, 16 newborns were diagnosed as having PPHN; however, none had known exposure to SSRIs (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Proportions of CHD Outcomes Among Mothers Who Did and Did Not Use SSRIs at Some Point During Pregnancya

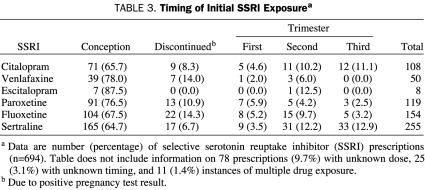

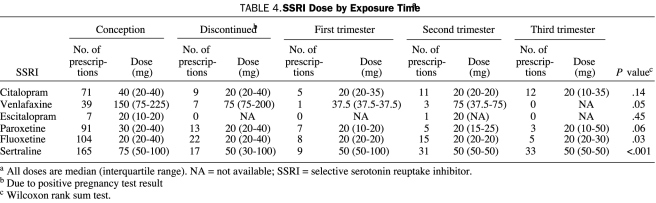

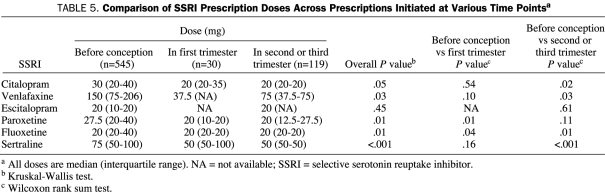

We also reviewed dose and timing of SSRI use during pregnancy. In fetuses exposed to an SSRI in which dose and timing data were available (n=694), 545 (78.5%) of the exposures occurred at conception. Overall, 68 of the 545 women discontinued use of their SSRI, leaving 477 (87.5%) who continued taking the SSRI after learning of their pregnancy (Table 3). The range of doses and the median dose of each SSRI at each exposure point are shown in Table 4. The median doses of fluoxetine (P=.03) and sertraline (P<.001) differed by exposure time. Table 5 shows the comparison between mean SSRI doses initiated before conception, in the first trimester, and in the second and third trimesters. The median doses of several SSRIs (citalopram, venlafaxine, fluoxetine, and sertraline) were significantly lower when prescribed during the second and third trimesters compared with the doses given before conception (Table 5).

TABLE 3.

Timing of Initial SSRI Exposurea

TABLE 4.

SSRI Dose by Exposure Timea

TABLE 5.

Comparison of SSRI Prescription Doses Across Prescriptions Initiated at Various Time Pointsa

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of major depressive disorders during pregnancy or the postpartum period is estimated to be between 10% and 15%.1,2 For the treatment of depression, SSRIs are the first-line pharmacotherapy. Antenatal and postpartum depression is a major concern for the health of both the mother and the newborn.

Several studies18-22 have shown an increased risk of VSDs in neonates exposed to paroxetine during the first trimester. This finding led the US Food and Drug Administration to advise women to avoid paroxetine during pregnancy if possible and to change pregnancy labeling from a category C to D. Paroxetine is the only SSRI whose pregnancy category labeling has changed. However, a recent meta-analysis23 that reviewed both previously published and unpublished data noted no association between paroxetine and cardiovascular defects.

In our study, 134 of the SSRI-treated mothers took paroxetine. None of the paroxetine-exposed newborns were diagnosed as having VSDs. In reviewing the 119 cases of paroxetine use during pregnancy for which all data were available, the average dose was 31.55 mg, with most exposures (76.47%) occurring at conception and continuing throughout pregnancy.

We found that SSRI use during the prenatal period is relatively low, occuring in 3.2% of our study population. We noted that doses of prescribed SSRIs are significantly lower if initiated during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy compared with those prescribed at the time of conception. This finding may demonstrate that some physicians may be hesitant to prescribe higher doses of SSRIs to pregnant women. It also raises the question of whether the doses prescribed later in pregnancy are clinically useful.

In light of this and other research, important clinical questions include whom to treat and how to formulate an informed consent discussion. An informed consent discussion should include the risks of depression during pregnancy, nonpharmacological treatment options for depression, possible risks of SSRI exposure to the fetus, potential adverse effects to the mother, and benefits of SSRI use for treatment of depression. The patient's ultimate decision and the reason for her decision should also be discussed. Treatment is a personal decision between the patient and physician, with the balance weighing toward the patient's decision. Furthermore, physicians should have a similar discussion with all women of reproductive age when considering treatment with an SSRI because most of our patients were taking SSRIs at the time of conception. Accumulating data demonstrate the safety of SSRI use during pregnancy in terms of congenital defects; SSRIs should be considered for use during pregnancy when the benefit of treatment outweighs the estimated risk posed by medication exposure.

Our study has several strengths. We reviewed data throughout several years at a single medical center. In addition, the obstetrics database used is prospectively maintained. Although this is a tertiary medical facility, most of the obstetrics population is community based. We reviewed all pregnancies during this period, which certainly decreased our selection bias and allowed us to look at prescription practices. Because drug exposure information in our data was not based on a patient's memory, there is no possibility of recall bias.

Limitations of our study should not be overlooked. We did not review demographic or clinical information, including use of other prescription or nonprescription drugs, tobacco use, or alcohol use, that may affect fetal outcomes. Determining adherence to prescribed SSRI therapy during pregnancy is problematic. A patient who had SSRI use documented or prescribed during pregnancy but who did not ingest the SSRI would be misclassified as an exposure. Our data were taken from physician prescriptions rather than pharmacy records; the former may document an increased risk of nonadherence. Furthermore, we did not review the actual amount of time the fetus was exposed to an SSRI.

The ability to diagnose these disorders is also a concern; although PPHN would be diagnosed soon after birth, a small VSD may be undetected. Therefore, we may have underestimated the total number of heart defects. However, our overall rate of 0.8% is similar to previous CHD estimates of 0.4% to 1.0%,15-17 suggesting that we did not miss large numbers of outcomes.

Finally, we were attempting to study an association between a rare exposure (SSRI use during pregnancy) and a rare outcome (CHD in newborns), and, despite the large sample size, the study was underpowered to detect small associations. However, assuming an overall exposure rate to SSRIs of 3.2%, we had 80% power to detect an odds ratio of 2.4 with this sample size. An odds ratio of 2.4 would have represented an increased rate of CHD of 1.9% in SSRI-exposed newborns compared with a baseline rate of 0.8% in infants not exposed to SSRIs. We cannot rule out the possibility that the risk may have been lower, but our data suggest no increased risk in SSRI-exposed newborns.

CONCLUSION

Overall, we noted no association between CHD or PPHN and SSRI use during pregnancy, and we were able to add to the growing field of evidence demonstrating the safety of using SSRIs during pregnancy. Although a randomized controlled trial is the definitive tool to aid with resolution of the issue of whether CHD is associated with SSRI use during pregnancy, ethical issues arise when considering a randomized controlled trial on potential adverse fetal outcomes of SSRI use during pregnancy. Additional large-scale, population-based cohort studies may be the only alternative. Until more definitive conclusions are available, increased fetal and newborn monitoring should be considered. We noted a statistically significant difference in the doses of SSRIs prescribed during the second and third trimesters compared with the doses used before conception. This finding may be attributable to the hesitancy of physicians to prescribe SSRIs during pregnancy. Nonetheless, physicians should use caution in prescribing SSRIs to pregnant women if the doses are not clinically useful.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 160th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 21, 2007; San Diego, CA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burt VK, Hendrick VC. Clinical Manual of Women's Mental Health Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2005:37-60 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nonacs R, Viguera AC, Cohen LS. Psychiatric aspects of pregnancy. In: Kornstein SG, Clayton AH, eds. Women's Mental Health: A Comprehensive Textbook New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002:70-84 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koren G, Matsui D, Einarson A, Knoppert D, Steiner M. Is maternal use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the third trimester of pregnancy harmful to neonates? CMAJ 2005;172(11):1457-1459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chambers CD, Johnson KA, Dick LN, Felix RJ, Jones KL. Birth outcomes in pregnant women taking fluoxetine. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(14):1010-1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nordeng H, Lindemann R, Perminov KV, Reikvam A. Neonatal withdrawal syndrome after in utero exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Acta Paediatr. 2001;90(3):288-291 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanz EJ, De-las-Cuevas C, Kiuru A, Bate A, Edwards R. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnant women and neonatal withdrawal syndrome: a database analysis. Lancet 2005;365(9458):482-487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeskind PS, Stephens LE. Maternal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use during pregnancy and newborn neurobehavior. Obstet Gynecol Survey 2004;59(8):564-566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casper RC, Fleisher BE, Lee-Ancajas JC, et al. Follow-up of children of depressed mothers exposed or not exposed to antidepressant drugs during pregnancy. J Pediatr. 2003;142(4):402-408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laine K, Heikkinen T, Ekblad U, Kero P. Effects of exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy on serotonergic symptoms in newborns and cord blood monoamine and prolactin concentrations. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60(7):720-726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Einarson TR, Einarson A. Newer antidepressants in pregnancy and rates of major malformations: a meta-analysis of prospective comparative studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(12):823-827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malm H, Klaukka T, Neuvonen PJ. Risks associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(6):1289-1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen SW, Yang Q, Garner P, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(4):961-966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louik C, Lin AE, Werler MM, Hernández-Díaz S, Mitchell AA. First-trimester use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(26):2675-2683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alwan S, Reefhuis J, Rasmussen SA, Olney RS, Friedman JM, National Birth Defects Prevention Study Use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(26):2684-2692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenthal G. Prevalence of congenital heart disease. In: Garson A, Bricker JT, Fisher DJ, Neish SR, eds. The Science and Practice of Pediatric Cardiology Vol 2 2nd ed.Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1998:1083-1105 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferencz C, Rubin JD, McCarter RJ, et al. Congenital heart disease: prevalence at livebirth: the Baltimore-Washington Infant Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121(1):31-36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marelli AJ, Mackie AS, Ionescu-Ittu R, Rahme E, Pilote L. Congenital heart disease in the general population: changing prevalence and age distribution. Circulation 2007January16;115(2):163-172 Epub 2007 Jan 8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paxil [package insert] Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bar-Oz B, Einarson T, Einarson A, et al. Paroxetine and congenital malformations: meta-analysis and consideration of potential confounding factors. Clin Ther. 2007;29(5):918-926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bérard A, Ramos E, Rey E, Blais L, St-André M, Oraichi D. First trimester exposure to paroxetine and risk of cardiac malformations in infants: the importance of dosage. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2007;80(1):18-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cole JA, Ephross SA, Cosmatos IS, Walker AM. Paroxetine in the first trimester and the prevalence of congenital malformations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(10):1075-1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Källén BA, Otterblad Olausson P. Maternal use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in early pregnancy and infant congenital malformations. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2007;79(4):301-308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Einarson A, Pistelli A, DeSantis M, et al. Evaluation of the risk of congenital cardiovascular defects associated with use of paroxetine during pregnancy [published corrections appear in Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(6): 777 and 2008;165(9):1208] Am J Psychiatry. 2008June;165(6):749-752 Epub 2008 Apr 1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chambers CD, Hernandez-Diaz S, Van Marter LJ, et al. Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(6):579-587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]