Abstract

Milk-alkali syndrome (MAS) consists of hypercalcemia, various degrees of renal failure, and metabolic alkalosis due to ingestion of large amounts of calcium and absorbable alkali. This syndrome was first identified after medical treatment of peptic ulcer disease with milk and alkali was widely adopted at the beginning of the 20th century. With the introduction of histamine2 blockers and proton pump inhibitors, the occurrence of MAS became rare; however, a resurgence of MAS has been witnessed because of the wide availability and increasing use of calcium carbonate, mostly for osteoporosis prevention. The aim of this review was to determine the incidence, pathogenesis, histologic findings, diagnosis, and clinical course of MAS. A MEDLINE search was performed with the keyword milk-alkali syndrome using the PubMed search engine. All relevant English language articles were reviewed. The exact pathomechanism of MAS remains uncertain, but a unique interplay between hypercalcemia and alkalosis in the kidneys seems to lead to a self-reinforcing cycle, resulting in the clinical picture of MAS. Treatment is supportive and involves hydration and withdrawal of the offending agents. Physicians and the public need to be aware of the potential adverse effects of ingesting excessive amounts of calcium carbonate.

GFR = glomerular filtration rate; MAS = milk-alkali syndrome; 1,25-OH vitamin D = 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; PTH = parathyroid hormone

Milk-alkali syndrome (MAS) consists of hypercalcemia, various degrees of renal failure, and metabolic alkalosis as a result of ingestion of large amounts of calcium and absorbable alkali. This syndrome was discovered in the 1930s after treatment of peptic ulcer disease with milk and sodium bicarbonate had become common.1 Initially considered a rare condition, MAS is now believed to be the third most common cause of in-hospital hypercalcemia, after hyperparathyroidism and malignant neoplasms.2 As newer treatments of peptic ulcer disease were introduced, calcium carbonate became the predominant source of calcium and alkali.3 Hypercalcemia can be severe. Renal failure is generally reversible, but impairment in renal function may persist in some cases.

The aim of this review was to determine the incidence, pathogenesis, histologic findings, diagnosis, and clinical course of MAS. A MEDLINE search was performed with the keyword milk-alkali syndrome using the PubMed search engine. All relevant English language articles were reviewed.

REPORT OF A CASE

A 47-year-old woman was referred to the emergency department because of abnormal laboratory results. The patient had undergone routine laboratory work performed before elective neck surgery for cervical stenosis. The following abnormalities were found (reference ranges shown parenthetically): creatinine, 7.2 mg/dL (0.6-1.0 mg/dL); serum urea nitrogen, 50 mg/dL (7-18 mg/dL); total calcium, 21.1 mg/dL (7.7-10.3 mg/dL); bicarbonate, 43 mEq/L (21-32 mEq/L); phosphate, 2.6 mg/dL (2.5-4.9 mg/dL); ionized calcium, 10.04 mg/dL (4.80-5.60 mg/dL); sodium, 133 mEq/L (136-145 mEq/L); and venous serum pH, 7.52 (7.35-7.38). The patient reported recent memory impairment and profound fatigue. She was taking calcium carbonate (1000 mg) plus vitamin D (400 U) twice daily. The patient had no medical or family history of renal failure. She had a history of bulimia but claimed to be in remission. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit, and aggressive hydration was initiated. On the basis of the laboratory findings and clinical picture, MAS was diagnosed.

On further questioning, the patient admitted to perhaps taking more calcium than she should have. The patient was self-medicating with additional antacids (calcium carbonate [Tums, GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC]) besides her twice daily calcium supplements with vitamin D because of occasional heartburn and because she believed more calcium was good for her bones.

HISTORY

Milk-alkali treatment of peptic ulcer disease was developed in early 1910 by Sippy,4 who subsequently published his landmark article. Sippy proposed that gastric acidity was the fueling force behind chronic ulcer disease. His therapy was designed to protect the ulcer from gastric juice corrosion until the ulcer was healed. Bedrest was required for approximately 4 weeks. Every hour throughout the day, 90 mL of a mixture of milk and cream was administered orally. Halfway between feedings and every half hour after the last meal, substantial amounts of alkali (0.65-2.00 g of heavy calcined magnesia [magnesium oxide], sodium bicarbonate, and bismuth subcarbonate) were administered. Occasionally, doses of up to 6.5 g of sodium bicarbonate were given every hour. Sippy reported an excellent response to this regimen, even in cases of ulcer disease recurrent for years with resulting high-grade pyloric obstruction. Milk-alkali therapy shortly became the standard for ulcer treatment.

In 1923, Hardt and Rivers5 at Mayo Clinic described the toxic adverse effects of Sippy's regimen, particularly in patients who required higher doses of alkali to control stomach acidity. Those patients would develop distaste for milk and experience headaches, irritability, dizziness, and occasionally nausea or vomiting. Three years earlier, MacCallum et al6 induced severe alkalosis and “gastric tetany” in dogs, leading to convulsions and death by mechanical pyloric obstruction. Administering sodium chloride prolonged the animals' lives. Hardt and Rivers found that patients who showed signs of toxemia were azotemic and had high serum bicarbonate levels. Although serum pH was not measured, the authors speculated that individuals had severe alkalemia, similar to that induced in animals by MacCallum et al. Preexistent renal failure and male sex seemed to be risk factors. The symptoms almost invariably disappeared within 24 to 48 hours after discontinuation of oral alkali. Serum calcium levels were not measured.

In 1936, Cope1 described several adverse effects of calcium carbonate-containing alkali therapy. He commonly found hypercalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, hypermagnesemia, azotemia, and increased bicarbonate levels in patients who had toxic symptoms. The symptoms and electrolyte abnormalities resolved with discontinuation of the antacid therapy. Renal function impairment persisted for weeks in some cases. The author expressed a strong belief that excessive calcium ingestion cannot be the sole cause of hypercalcemia: “It seems probable, therefore, that the renal impairment first occurs and that this renders the kidney unable to excrete sufficiently rapidly all the calcium, which continues to be absorbed from the gut.”

In 1949, Burnett et al7 described a “milk and alkali syndrome” in a report of 6 male patients treated with milk and absorbable alkali (usually sodium bicarbonate) for peptic ulcer disease. The common findings were hypercalcemia without hypercalciuria or hypophosphatemia, normal alkaline phosphatase level, alkalosis, renal insufficiency, corneal calcium deposits (band keratopathy), or other calcinosis (subcutaneous tissue, lung, falx cerebri, and lymph nodes). Except for renal failure, the majority of symptoms resolved shortly after discontinuation of the antacid therapy. Most of the patients developed chronic renal failure, and 4 died. The poor prognosis was strikingly different from the overall good outcome of the patients described by Cope.1 The authors concurred with Cope's theory that kidney damage resulted from excessive intake of calcium and alkali, which subsequently led to inability to excrete calcium and hypercalcemia.

In 1957, Wenger et al8 reviewed a series of 35 patients who had evidence of MAS among 3300 hospitalized patients with ulcers during a 10-year period. Similar to the Cope report, the patients had a good prognosis and fully recovered. No patient had persistent renal failure. The authors concluded that MAS is uncommon and generally reversible.

In 1963, Punsar and Somer9 reexamined all previously reported cases of MAS and, based on the chronicity of symptoms and prognosis, differentiated 2 forms: Burnett syndrome (chronic) and Cope syndrome (acute). Burnett syndrome is a chronic irreversible condition in which band keratopathy or other metastatic calcification was commonly seen. The most common symptoms in both forms were anorexia, dizziness, headache, confusion, psychosis, and dry mouth. Pruritus and pyuria were common in Burnett syndrome. Preexisting renal disease was observed in up to one-third of cases of Burnett syndrome. Hypercalcemia was present in all cases. Hyposthenuria was common. Urinary calcium excretion was generally normal. Among patients with Burnett syndrome, band keratopathy was seen in approximately 85% and nephrocalcinosis in more than 60%. The hallmark of Cope syndrome was an overall good prognosis, whereas mortality due to chronic renal failure was common in patients with Burnett syndrome. Before the widespread availability of parathyroid hormone (PTH) assays, differentiating between hyperparathyroidism and MAS was difficult and often was based on the clinical response to a diet low in calcium and absorbable alkali10,11 or on evidence of osteosclerosis.9

INCIDENCE

In the first decades after the discovery of MAS, reports on the incidence in patients treated by the Sippy program varied widely, from 2% to 18%.12-15 Individual variations in the amount of ingested alkali may provide an explanation for this phenomenon.16 The mortality rate in the early days of MAS was reported to be 4.4%.13

In their original study, Wenger et al8 found that the incidence of MAS among hospitalized patients with peptic ulcer disease was approximately 1%. After the clinical introduction of nonabsorbable alkali and histamine2 blockers, the incidence of MAS decreased substantially.17 In the 1970s and 1980s, MAS was considered responsible for less than 1% to 2% of hypercalcemia.2,18

In 2006, Beall et al3 described the “modern version” of MAS. During the past 20 years, a reemergence of MAS has been noted with different demographics and clinical backgrounds. Calcium carbonate is the primary source of calcium and alkali. The increased use of calcium carbonate in postmenopausal women, patients receiving long-term corticosteroid therapy, and patients with renal failure, as well as the wide availability of nonabsorbable alkali, histamine2 blockers, and proton pump inhibitors, has changed the profile of the typical patient with MAS. The male prevalence observed in the original MAS is no longer seen. Hyperphosphatemia is rare, reflecting the less prevalent consumption of large quantities of milk and dairy products and the phosphate-binding properties of calcium carbonate. Because of its resurgence, MAS is now considered the third most common cause of hypercalcemia, after hyperparathyroidism and malignant neoplasms, with a prevalence of 9% to 12% among hospitalized patients with hypercalcemia.2,19 Among the subset of patients with severe hypercalcemia (total calcium level >14 mg/dL), MAS is more prevalent than malignant neoplasms.19 Increased availability of over-the-counter calcium carbonate supplements and greater awareness of osteoporosis among medical professionals and consumers likely contribute to this trend.3 In a study by Kapsner et al,20 more than 20% of heart transplant recipients taking calcium carbonate (8-12 g) daily for corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis prevention developed hypercalcemia. Half of the patients with hypercalcemia had alkalosis.

An unusual form of MAS has been described in the Far East in betel nut chewers.21-23 The lime paste (calcium oxide and calcium hydroxide) ingested during betel nut chewing serves as a source of calcium and alkali. The incidence of MAS among betel nut chewers is unknown.

Several cases of MAS have also been described in pregnant women.24,25

PATHOGENESIS

Despite extensive clinical experience, scant data are available on the pathogenesis of MAS. Throughout the years, several contributing factors have been proposed, including loss of gastric juice, preexisting renal disease, insufficient chloride intake, hemorrhage, anemia, impaired liver function, and warm weather.16,26-31 Ingestion of excessive quantities of calcium and absorbable alkali is a prerequisite for establishing the diagnosis. What constitutes “excessive” is unclear but generally indicates at least 4 to 5 g of calcium carbonate daily.32,33 However, ingesting large amounts of alkali and calcium alone does not result in alkalosis and hypercalcemia, respectively. McGee et al34 administered 1.3 to 2.0 g of a mixture of calcium carbonate and magnesium oxide hourly from 7 am to 9 pm for 8 days to 17 individuals with healthy kidneys. No significant changes in serum bicarbonate levels were observed. The authors speculated that hypochloremia and dehydration were key factors in the development of alkalosis.35 In the first reports of toxicity due to the Sippy program, Hardt and Rivers5 noted a definite correlation between the incidence of alkalosis and the presence of kidney disease. Subsequent reports confirmed that preexisting renal disease seemed to be a predisposing factor.20,26,27,36 However, it is widely recognized that MAS can develop without renal impairment.37 Furthermore, even in patients with impaired renal function, large amounts of absorbable alkali do not lead to alkalosis in most individuals.14,38,39 Some authors found no preexisting kidney disease in most of their patients with MAS.1,15 Underlying renal disease does not seem to be a prerequisite but rather a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of MAS.

For hypercalcemia to develop, calcium intake must be excessive, but inability to excrete the excess calcium is also an essential part of the process. Because the skeletal system does not have unlimited calcium buffer capacity, tight regulation of calcium absorption from the small intestine and excretion by the kidneys are paramount to maintain serum calcium levels. Individual variations in the buffering capacity of bone may also have a role in the susceptibility to development of hypercalcemia.40

The role of vitamin D and PTH in MAS is unclear. Limited data suggest that 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25-OH vitamin D; also known as calcitriol) and PTH levels are suppressed in MAS.19,41-43 However, the extent of suppression varies, and calcitriol levels may remain well within the reference range.44 Increased intake of calcium results in decreased 25-hydroxylation of vitamin D by the kidneys, which leads to a marked decrease of fractional calcium absorption in the small intestine. Besides this active regulated mechanism, nonsaturable passive diffusion occurs. Individual variability of calcium absorption varies widely. In certain individuals, high urinary calcium excretion indicative of high intestinal absorption persists despite continuous calcium ingestion and suppressed 1,25-OH vitamin D levels.44,45 Under normal conditions, renal calcium excretion is a close reflection of calcium absorption.17,46 These “hyperabsorbers” readily excrete the excess calcium as long as their excretory capability is unaffected. However, if large quantities of calcium are continuously ingested and the renal excretory capacity is blocked, hypercalcemia may be a predictable result.32 Failure to fully suppress calcitriol levels may contribute to development of MAS in a subset of individuals with high oral calcium intake.40 The inability of some individuals to properly suppress 1,25-OH vitamin D levels, despite high calcium intake and absorption from the gut, has been well documented.47

Although controversial (as previously discussed), preexistent renal insufficiency has been implicated in the pathogenesis of MAS. Medications that interfere with calcium excretion have also been considered risk factors. Thiazides decrease calcium excretion by inhibiting the thiazide-sensitive sodium chloride cotransporter and promote intravascular depletion and alkalemia.48-50 It is well recognized that alkalosis decreases calcium excretion by increasing its tubular reabsorption.51,52 The mechanism seems to be PTH independent.51 However, hypercalcemia impairs the kidneys' ability to excrete excess bicarbonate, possibly closing a vicious cycle that in susceptible individuals may lead to severe hypercalcemia and renal failure. The increased serum calcium level causes afferent arteriole constriction and reduction in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR).53,54 Also, hypercalcemia has a well-known natriuretic and diuretic effect, presumably by activating the calcium-sensing receptor, and leads to intravascular depletion.55,56 Aspiration of gastric content to control acidity in the original Sippy regimen can further exacerbate intravascular depletion, as does hypercalcemia-induced renal hyposthenuria.56,57 The resulting GFR reduction further limits excretion of bicarbonate and calcium. The increasing serum calcium level propagates the toxic effects of calcium on the kidneys. Long-term exposure to high calcium levels can result in nephrocalcinosis, tubular necrosis, and other structural changes.58 An alkalotic environment is known to facilitate calcium precipitation.9,59 Aging results in a decreased capacity to handle excess calcium, probably because of decreased renal function and down-regulation of the calcium-sensing receptor in chronic renal disease, and may predispose patients to developing hypercalcemia.40,60 Hypokalemia due to gastric suctioning and vomiting may have an additional renal deleterious effect. The combination of calcium and absorbable alkali seems to be necessary for the development of MAS. Absorbable alkali alone does not produce alkalosis. Even large administered amounts of sodium bicarbonate are readily excreted by the kidneys without persistent alkalemia. This has been well documented in humans and animals.61-63

The PTH level should be depressed by the high serum calcium level in patients with MAS. However, data are limited. Occasional reports showed inappropriately elevated PTH levels.33,64 In at least some of those cases, use of C-terminal assays to measure PTH levels in the setting of renal failure could explain the high levels. Decreasing serum calcium levels have been contemplated as the cause of high PTH levels even if the patient is still hypercalcemic.64 Data to support this theory are lacking, but a similar phenomenon has been observed in hypercalcemia seen in the polyuric phase of rhabdomyolysis.65 Intact PTH measurements generally reveal appropriately suppressed hormone levels,2 but available data are scant. The low serum PTH level further contributes to alkalemia by increasing urinary resorption of bicarbonate.66,67 Temporary hypocalcemia is not unusual after treatment of MAS and likely reflects a suppressed PTH level.2

HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS

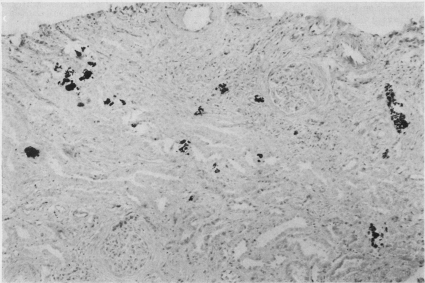

The available data on pathologic changes in the kidneys determined by biopsy and autopsy are limited. Burnett et al7 described nephrocalcinosis during the single autopsy performed in their series. Other autopsy reports described partial to complete glomerulus hyalinization, thickening of the Bowman capsule, tubular atrophy, vascular changes, and diffuse lymphocytic infiltration.68-70 Extensive calcification of convoluted renal tubular cells and the tubular lamina was described as a striking feature.68 Scholz and Keating10 reported a case of focal calcification in the renal tubules that was apparent on a kidney biopsy specimen from a patient with MAS. Randall et al71 reported findings on kidney biopsy specimens from 2 patients. Tubular epithelium degeneration and granular (presumably calcium laden) material in and around the collecting tubules, as well as hyalinization of several glomeruli and thickening of the basement membrane, were described. In 1976, Junor and Catto72 reported a series of 3 cases in which kidney biopsy specimens showed focal calcium deposition within and adjacent to the renal tubules (Figure 1). Some correlation was found between the amount of calcium deposition and renal outcome. The 2 patients with persistent renal impairment had more prominent calcium deposition, as well as interstitial fibrosis, areas of inflammatory changes, and periglomerular fibrosis. The authors concluded that prognosis depends on the severity of the histologic changes apparent on the biopsy specimens and noted that calcium deposition in the kidneys is not usually seen radiographically.

FIGURE.

Kidney biopsy specimen from patient with milk-alkali syndrome (Von Kassa stain, original magnification ×150). Calcium deposits are stained black by silver nitrate. Adapted from J Clin Pathol,72 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

DIAGNOSIS AND CLINICAL COURSE

The diagnosis of MAS requires a history of excessive calcium and absorbable alkali ingestion and findings of hypercalcemia, metabolic alkalosis, and variable degrees of renal impairment. The symptoms may develop within several days to several weeks and months after the start of therapy with absorbable alkali and calcium. Three forms of MAS have been described: acute, subacute (Cope syndrome), and chronic (Burnett syndrome).9 Because overlap among the 3 forms is substantial, they should be considered a continuum. The first symptoms may occur within a few days. Nausea, vomiting, anorexia, distaste for milk, headache, dizziness, vertigo, apathy, and confusion are early signs of toxemia.32 Muscle aches, psychosis, tremor, polyuria, polydipsia, pruritus, and abnormal calcifications are typical of the chronic phase.7,11 Ocular calcification is a classic physical sign that consists of keratopathy and calcium deposits in the conjunctiva. Keratopathy can be mistaken for arcus senilis.9 On closer inspection, individual minute corneal calcifications can generally be distinguished.70 The nasal and temporal areas of the circle contain the greatest concentration of calcium.70 Renal calcinosis is not uncommon (see “Histologic Findings” section). Other less common sites of metastatic calcification have been described, including periarticular tissue,71 subcutaneous tissue,73 central nervous system,70 liver,74 adrenal,74 bone,9 and lungs.70 A case was described in 1993 in which discovery of bilateral breast calcifications in a patient led to the diagnosis of MAS.43

Withdrawal of the offending agents generally leads to quick resolution of the symptoms, except for renal failure, which invariably improves but does not always resolve completely.7 Keratopathy and conjunctival calcium deposits can be reversible.9,75 Hypercalcemia is always present and may be severe. The combination of an elevated serum bicarbonate level and alkalotic pH in the setting of renal failure always places MAS high on the differential diagnosis. A low to normal phosphate level is usually seen in the modern form of MAS as opposed to hyperphosphatemia, which was the norm in the classic syndrome. Levels of 1,25-OH vitamin D and intact PTH are generally suppressed. In less typical cases of MAS, the PTH level may need to be measured to exclude primary hyperparathyroidism. Conversely, misdiagnosing MAS as primary hyperparathyroidism was common in the past and likely still happens today. In a study by Beall and Scofield,2 approximately 10% of patients with MAS underwent unnecessary parathyroid exploration. Obtaining accurate medication and diet histories is paramount to establishing the correct diagnosis. Unusual sources of calcium, such as cheese, have been reported occasionally, especially in patients with pica or bulimia.76 Evidence of resorptive bone disease and renal stones, as well as failure to respond to withdrawal of calcium and alkali, strongly suggests hyperparathyroidism or some other etiology.32 However, hypercalcemia in advanced cases of MAS may be slow to resolve. As previously mentioned, PTH levels have been occasionally elevated in patients with MAS, and coexistence of hyperparathyroidism and MAS may need to be considered.

Supportive therapy and hydration after withdrawal of the offending agent are generally sufficient treatment in most cases. Recovery from the acute form usually occurs within 1 or 2 days. With the chronic form, symptomatic improvement is a slower process. In refractory cases, hemodialysis may occasionally be necessary. Furosemide may be used to enhance calciuresis. Administering bisphosphonates to patients with MAS has been reported,19 but no data are available to support the theory that bisphosphonates alter outcome. Hypercalcemia generally resolves within several days, although some evidence suggests that serum calcium levels can be elevated up to 6 months.64 Temporary hypocalcemia, which can be severe and symptomatic, is not unusual and may require replacement therapy.2 Slow recovery of the serum PTH level is likely responsible for this phenomenon. In some cases, the PTH level has been noted to increase by more than 1 order of magnitude as the serum calcium level decreases below physiologic levels.

CONCLUSION

The resurgence of MAS in the current era is a result of increased osteoporosis awareness and routine use of calcium supplements for prevention. The public needs to be educated about calcium supplementation and the potential adverse effects if the recommended dosage is exceeded. Daily elemental calcium intake of no more than 2 g is considered safe.2,77 However, even doses lower than 2 g daily may result in MAS if additional predisposing factors are present. Muldowney and Mazbar78 described a patient with bulimia who developed MAS by taking about 1.7 g of calcium daily. Reducing daily calcium intake or close monitoring may be prudent in patients taking thiazides,79,80 patients who have preexisting renal failure, or those who experience concurrent vomiting (bulimia or hyperemesis of pregnancy).76,78,81,82 Patients with bulimia seem to be particularly vulnerable because of the frequent combination of vomiting, diuretic use, and deviant eating habits.76,78 In these susceptible patient groups, supplementing calcium in a form that contains no absorbable alkali is probably a safer choice.2

The exact pathomechanism of MAS remains uncertain, but a unique interplay between hypercalcemia and alkalosis in the kidneys seems to lead to a self-reinforcing cycle, resulting in the clinical picture of MAS. Treatment is supportive and involves hydration and withdrawal of the offending agents. Physicians and the public need to be aware of the potential adverse effects of ingesting excessive amounts of calcium carbonate.

CASE OUTCOME

Our patient's hypercalcemia resolved within 72 hours. Transiently, she had mild hypocalcemia, with a total calcium level of 6.9 mg/dL. As expected, her intact PTH level was suppressed at 10 pg/mL (reference range, 10-65 pg/mL). Her 25-OH cholecalciferol level was normal at 44 ng/mL (reference range, 20-100 ng/mL), and her 25-OH ergocalciferol level was undetectable, ruling out vitamin D toxic effects. After 1 week, the patient's creatinine level stabilized at 1.4 mg/dL and remained in that range at follow-up a few weeks later. The estimated GFR was 47 mL/min, consistent with persistent mild renal insufficiency. The patient was counseled on the nature of her condition, and she was advised to avoid taking excessive amounts of calcium. In the following months her serum creatinine normalized, and she remained asymptomatic.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cope CL. Base changes in the alkalosis produced by the treatment of gastric ulcer with alkalies. Clin Sci. 1936;2:287-300 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beall DP, Scofield RH. Milk-alkali syndrome associated with calcium carbonate consumption: report of 7 patients with parathyroid hormone levels and an estimate of prevalence among patients hospitalized with hypercalcemia. Medicine (Baltimore) 1995;74(2):89-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beall DP, Henslee HB, Webb HR, Scofield RH. Milk-alkali syndrome: a historical review and description of the modern version of the syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 2006;331(5):233-242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sippy BW. Gastric and duodenal ulcer: medical cure by an efficient removal of gastric juice corrosion. JAMA 1915;64:1625-1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardt LL, Rivers AB. Toxic manifestations following the alkaline treatment of peptic ulcer. Arch Intern Med. 1923;31(2):171-180 [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacCallum WG, Lintz J, Vermilye HN, Leggett TH, Boas E. The effect of pyloric obstruction in relation to gastric tetany. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1920;31:1 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnett CH, Commons RR, Albright F, Howare JE. Hypercalcemia without hypercalciuria or hyperphosphatemia, calcinosis and renal insufficiency: syndrome following the prolonged intake of milk and alkali. N Engl J Med. 1949;240(20):787-794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wenger J, Kirsner JB, Palmer WL. The milk-alkali syndrome: hypercalcemia, alkalosis and azotemia following calcium carbonate and milk therapy of peptic ulcer. Gastroenterology 1957;33(5):745-769 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Punsar S, Somer T. The milk alkali syndrome: a report of three illustrative cases and a review of the literature. Acta Med Scand 1963;173(4):435-449 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scholz DA, Keating FR., Jr Milk-alkali syndrome: review of 8 cases. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1955;95(3):460-468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Texter EC, Jr, Laureta HC. The milk-alkali syndrome. Am J Dig Dis. 1966;11(5):413-418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rafsky HA, Schwartz L, Kruger AW. The relation of alkalosis to peptic ulcer. JAMA 1932November5;99:1582 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooke AM. Alkalosis occurring in the alkaline treatment of peptic ulcers. Q J Med. 1932;1(4):527-541 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirsner JB, Palmer WL. Alkalosis complicating the Sippy treatment of peptic ulcer: an analysis of one hundred and thirty-five episodes. Arch Intern Med. 1942;69(5):789-807 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gatewood WE, Gaebler OH, Muntwyler E, Myers VC. Alkalosis in patients with peptic ulcer. Arch Intern Med. 1928;42(1):79-105 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jephers H, Lerner HH. The syndrome of alkalosis complicating the treatment of peptic ulcer: report of cases with review of the pathogenesis, clinical aspects and treatment. N Engl J Med. 1936;214:1236-1244 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuman CA, Jones HW., III The ‘milk-alkali’ syndrome: two case reports with discussion of pathogenesis. Q J Med. 1985;55(217):119-126 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jamieson MJ. Hypercalcaemia. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;290(6465):378-382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Picolos MK, Lavis VR, Orlander PR. Milk-alkali syndrome is a major cause of hypercalcaemia among non-end-stage renal disease (non-ESRD) inpatients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2005;63(5):566-576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kapsner P, Langsdorf L, Marcus R, Kraemer FB, Hoffman AR. Milk-alkali syndrome in patients treated with calcium carbonate after cardiac transplantation. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146(10):1965-1968 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin SH, Lin YF, Cheema-Dhadli S, Davids MR, Halperin ML. Hypercalcaemia and metabolic alkalosis with betel nut chewing: emphasis on its integrative pathophysiology. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17(5):708-714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu KD, Chuang RB, Wu FL, Hsu WA, Jan IS, Tsai KS. The milk-alkali syndrome caused by betelnuts in oyster shell paste. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1996;34(6):741-745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norton SA. Betel: consumption and consequences. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998:38(1):81-88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Picolos MK, Sims CR, Mastrobattista JM, Carroll MA, Lavis VR. Milk-alkali syndrome in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(5, pt 2):1201-1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ennen CS, Magann EF. Milk-alkali syndrome presenting as acute renal insufficiency during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(3, pt 2):785-786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisele CW. Changes in acid-base balance during alkali treatment for peptic ulcer. Arch Intern Med. 1939;63(6):1048-1067 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilkinson SA, Jordan SM. Significance of alkalosis in treatment of peptic ulcer. Am J Dig Dis Nutrition 1934;1(6):509-512 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frouin A. L'action des chlorures de l'alimentation sur la sécrétion gastrique. Presse Méd 1922;30:1906 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bockus HL, Bank J. Alkalosis and duodenal ulcer. Med Clin North Am. 1932;16:143 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hubble D. Correspondence. Lancet 1935September14;2:634 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sippe C. Dangers of indiscriminate alkali therapy. M J Australia 1935April20;1:48s [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orwoll ES. The milk-alkali syndrome: current concepts. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97(2):242-248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newmark K, Nugent P. Milk-alkali syndrome: a consequence of chronic antacid abuse. Postgrad Med. 1993;93(6):149-150, 156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGee LC, Martin JE, Jr, Levy F, Purdum RB. The influence of alkalis on renal function. Am J Digest Dis. 1939;6:186 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirsner JB, Palmer WL. The role of chlorides in alkalosis: following the administration of calcium carbonate. JAMA 1941;116:384-389 [Google Scholar]

- 36.French JK, Holdaway IM, Williams LC. Milk alkali syndrome following over-the-counter antacid self-medication. N Z Med J 1986;99:322-323 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wildman HA. Chloride metabolism and alkalosis in the alkali treatment of peptic ulcer. Arch Intern Med. 1929;43(5):615-632 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jordan SM. Calcium, chloride and carbon dioxide content of venous blood in cases of gastroduodenal ulcer treated with alkalis. JAMA 1926;87(4):1906 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oakley WM. Alkalosis arising in the treatment of peptic ulcer. Lancet 1935July27;2:187 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Felsenfeld AJ, Levine BS. Milk alkali syndrome and the dynamics of calcium homeostasis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006July;1(4):641-654 Epub 2006 Apr 26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dorsch TR. The milk-alkali syndrome, vitamin D, and parathyroid hormone [letter]. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105(5):800-801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spital A, Freedman Z. Severe hypercalcemia in a woman with renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;26(4):674-677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abreo K, Adlakha A, Kilpatrick S, Flanagan R, Webb R, Shakamuri S. The milk-alkali syndrome: a reversible form of acute renal failure. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:1005-1010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adams ND, Gray RW, Lemann J., Jr The effects of oral CaCO3 loading and dietary calcium deprivation on plasma 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D concentrations in healthy adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1979;48(6):1008-1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vincent PC, Radcliff FJ. The effect of large doses of calcium carbonate on serum and urinary calcium. Am J Dig Dis. 1966;11(4):286-295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sutton RAL, Diks JH. Renal handling of calcium, phosphate, and magnesium. In: Brenner BM, Rector FC, Jr, eds. The Kidney Vol 1 2nd ed.Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1981:551-618 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Broadus AE, Insogna KL, Lang R, Ellison AF, Dreyer BE. Evidence for disordered control of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D production in absorptive hypercalciuria. N Engl J Med. 1984;311(2):73-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nijenhuis T, Vallon V, van der Kemp AW, Loffing J, Hoedenerop JG, Bindels RJ. Enhanced passive Ca2+ reabsorption and reduced Mg2+ channel abundance explains thiazide-induced hypocalciuria and hypomagnesemia. J Clin Invest 2005June;115(6):1651-1658 Epub 2005 May 12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Greger R. New insights into the molecular mechanism of the action of diuretics [editorial]. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14(3):536-540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sebastian A. Thiazides and bone [editorial]. Am J Med. 2000;109(5):429-430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sutton RA, Wong NL, Dirks JH. Effects of metabolic acidosis and alkalosis on sodium and calcium transport in the dog kidney. Kidney Int. 1979;15(5):520-533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peraino RA, Suki WN. Urine HCO3 augments renal Ca 2+ absorption independent of systemic acid-base changes. Am J Physiol. 1980;238(5):F394-F398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benabe JE, Martinez-Maldonado M. Hypercalcemic nephropathy. Arch Intern Med. 1978;138(5):777-779 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Humes HD, Ichikawa I, Troy JL, Brenner BM. Evidence for a parathyroid hormone-dependent influence of calcium on the glomerular ultrafiltration coefficient. J Clin Invest 1978;61(1):32-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown EM. Physiology and pathophysiology of the extracellular calcium sensing receptor. Am J Med. 1999;106(2):238-253 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beck N, Singh H, Reed SW, Murdaugh HV, Davis BB. Pathogenic role of cyclic AMP in the impairment of urinary concentrating ability in acute hypercalcemia. J Clin Invest 1974;54(5):1049-1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zeffren JL, Heineman HO. Reversible defect in renal concentrating mechanism in patients with hypercalcemia. Am J Med. 1962July;33:54-63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ganote CE, Philipsborn DS, Chen E, Carone FA. Acute calcium nephrotoxicity: an electron microscopical and semiquantitative light microscopical study. Arch Pathol. 1975;99(12):650-657 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parfitt AM. Soft-tissue calcification in uremia. Arch Intern Med. 1969;124(5):544-546 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mathias RS, Nguyen HT, Zhang MY, Portale AA. Reduced expression of the renal calcium-sensing receptor in rats with experimental chronic renal insufficiency. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9(11):2067-2074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Goidsenhoven GM, Gray OV, Price AV, Sanderson PH. The effect of prolonged administration of large doses of sodium bicarbonate in man. Clin Sci (Lond) 1954;13(3):383-401 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sanderson PH. Renal response to massive alkali loading in the human subject. In: Lewis AAG, Wolstenholme GEW, eds. Ciba Foundation Symposium on the Kidney Boston, MA: Little Brown & Co; 1954:165-176 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seldin DW, Rector FC., Jr The generation and maintenance of metabolic alkalosis. Kidney Int. 1972;1(5):306-321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carroll PR, Clark OH. Milk alkali syndrome: does it exist and can it be differentiated from primary hyperparathyroidism? Ann Surg. 1983;197(4):427-433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Llach F, Felsenfeld AJ, Haussler MR. The pathophysiology of altered calcium metabolism in rhabdomyolysis-induced acute renal failure: interactions of parathyroid hormone, 25-hydroxycholecaciferol, and 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol. N Engl J Med. 1981;305(3):117-123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Muldowney FP, Carroll DV, Donohoe JF, Freaney R. Correction of renal bicarbonate wastage by parathyroidectomy: implications in acid-base homeostasis. Q J Med. 1971;40(160):487-498 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nordin BE. The effect of intravenous parathyroid extract on urinary pH, bicarbonate and electrolyte excretion. Clin Sci. 1960May;19:311-319 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wermer P, Kuschner M, Riley EA. Reversible metastatic calcification associated with excessive milk and alkali intake. Am J Med. 1953;14(1):108-115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Holten C, Lundbaek K. Renal insufficiency and severe calcinosis due to excessive alkali intake. Acta Med Scand 1955;151(3):177-183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dufault FX, Jr, Tobias GJ. Potentially reversible renal failure following excessive calcium and alkali intake in peptic ulcer therapy. Am J Med. 1954;16(2):231-236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Randall RE, Jr, Strauss MB, McNeely WF. The milk-alkali syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1961;107(2):163-181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Junor BJ, Catto GR. Renal biopsy in the milk-alkali syndrome. J Clin Pathol. 1976;29(12):1074-1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Snapper I, Bradley WG, Wilson VE. Metastatic calcification and nephrocalcinosis from medical treatment of peptic ulcer. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1954;93(6):807-817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kyle LH. Differentiation of hyperparathyroidism and the milk-alkali (Burnett) syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1954;251(26):1035-1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wenger J, Kirsner JB, Palmer WL. The milk-alkali syndrome: hypercalcemia, alkalosis and temporary renal insufficiency during milk-antacid therapy for peptic ulcer. Am J Med. 1958;24(2):161-163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kallner G, Karlsson H. Recurrent factitious hypercalcemia. Am J Med. 1987;82(3):536-538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Whiting SJ, Wood R, Kim K. Calcium supplementation. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 1997;9(4):187-192 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Muldowney WP, Mazbar SA. Rolaids-yogurt syndrome: a 1990s version of milk-alkali syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;27(2):270-272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gora ML, Seth SK, Bay WK, Visconti JA. Milk-alkali syndrome associated with use of chlorothiazide and calcium carbonate. Clin Pharm 1989;8(3):227-229 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jenkins JK, Best TR, Nicks SA, Murphy FY, Bussell KL, Vesely DL. Milk-alkali syndrome with a serum calcium level of 22 mg/dL and J waves on the ECG. South Med J 1987;80(11):1444-1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ullian ME, Linas SL. The milk-alkali syndrome in pregnancy: case report. Miner Electrolyte Metab 1988;14(4):208-210 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gordon MV, McMahon LP, Hamblin PS. Life-threatening milk-alkali syndrome resulting from antacid ingestion during pregnancy. Med J Aust. 2005;182(7):350-351 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]