Abstract

We examined the longitudinal pathways from marijuana use in the familial environment (parents and siblings) and non-familial environment (peers and significant other), throughout adolescence and young adulthood, to the participants’ own marijuana use in their fourth decade of life (n = 586). Longitudinal pathways to marijuana use were assessed using structural equation modeling. Familial factors were mediated by non-familial factors; sibling marijuana use also had a direct effect on the participants’ marijuana use. In the non-familial environment, significant other marijuana use had only a direct effect, while peer marijuana use had direct as well as indirect effects on the participants’ marijuana use. Results illustrate the importance of both modeling and selection effects in contributing to marijuana use. Regarding prevention and treatment, this study suggests the need to consider aspects of familial and non-familial social environments.

INTRODUCTION

Marijuana use has been consistently associated with poor physical health1–4 as well as impaired psychological functioning,.5–10 and is thus a serious public health problem. To further study this matter, the current research attempts to identify several psychosocial antecedents of marijuana use in adulthood. More specifically, we examine the extent to which marijuana use by four types of influential people (ie, parents, siblings, peers, and significant others), from adolescence (mean age 14) through early adulthood (mean age 27), predicts one’s own marijuana use in the fourth decade of life (assessed at mean ages of 32 and 37). An understanding of the longitudinal interpersonal influences on, and stability of, marijuana use is essential to expand efforts to prevent its use by adolescents.

According to Family Interactional Theory (FIT),11 there are two types of social environments that may affect marijuana use: “familial” and “non-familial.” Familial relationships refer to relationships the individual does not choose—in this case, parents and siblings. Parents and siblings may encourage certain types of relationships and discourage other types of relationships. Non-familial relationships refer to relationships the individual does choose; peers and significant others represent types of non-familial relationships. According to FIT, the effect of the familial environment (ie, parental and sibling marijuana use) on the participant’s marijuana use is indirect. Parents and siblings influence the individual in part by influencing the non-familial environment. Furthermore, in line with FIT, sibling marijuana use has a direct effect on the participant’s marijuana use as a result of the participant modeling the drug use of his/her siblings.12 Moreover, individuals may select peers and partners who have similar characteristics to themselves and to individuals in their homes (eg, siblings). This has been referred to in the literature as assortative peer and partner selection.11 Finally, FIT postulates that peers and partners each have a direct effect on the individual’s use of marijuana. The current study further serves the purpose of examining the respective influence of the two types of social environments on marijuana use.

Based on the literature and theoretical considerations, we postulate an association between marijuana use by both familial and non-familial others in one’s life and one’s own marijuana use. Across a number of studies, researchers have established a consistent association between others’ illegal drug use (ie, significant others, peers, parents, and siblings) and the participant’s own marijuana and other illegal drug use.13–24 In the familial domain, a number of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, employing samples of varying ethnicities, have found that adolescents whose parents and/or siblings use marijuana or other illegal drugs are more likely to use marijuana or other illegal drugs themselves.13–21 Similar findings have been obtained in the more limited research conducted on young adult samples.22–28

Additionally, a small number of studies have been conducted on the more long-term implications of adolescent exposure to marijuana use in the familial domain measured in adolescence. For instance, one study 25 found that parental factors at age 17 (including parental marijuana use) predicted frequency of marijuana use at age 21.

In the non-familial domain, both adolescents and young adults who have substance-using peers demonstrate a greater probability of concurrent substance use themselves.26–30 Among significant others, several studies have found marijuana use by the spouse to be highly associated with the participant’s own use, in cross-sectional as well as longitudinal designs.19,31

Although the literature has consistently established an association between marijuana use and other illegal drug use in the familial and non-familial environments with one’s own marijuana and other illegal drug use, there is some question as to the respective pathways from drug use in each environment to the participant’s own marijuana use. This is particularly true of familial drug use. Some studies have discerned a direct relationship between familial and self drug use, including marijuana.16 However, according to FIT,11 and as supported by empirical findings,.32 the influence of familial drug use on the participant’s drug use may not be direct, but instead mediated by the greater likelihood that youths whose parents and/or siblings use illegal drugs are more likely to select peers or significant others who use illegal drugs.

There has also been little work on the more longer-term influences of marijuana use in either the familial or the non-familial environment. More specifically, there is a dearth of research focusing on how marijuana use in either the familial or the non-familial environment influences the participant’s marijuana use beyond the twenties.

The current study thus serves to address this gap in the literature: a) on the longitudinal mechanisms underlying marijuana use beyond the twenties; b) by assessing the marijuana use of a sample of respondents in their fourth decade of life (age = 35); and c) by examining the relationship between self marijuana use and both familial and non-familial marijuana use, assessed beginning in adolescence through young adulthood. In doing so, we also endeavor to disentangle the various longitudinal interpersonal influences on marijuana use in adulthood.

Based on FIT, we hypothesized that marijuana use in the familial environment is related to marijuana use in the non-familial environment, which, in turn, is associated with the participant’s own use of marijuana.We also hypothesized that there are direct paths between sibling, peer, and significant other marijuana use and the participant’s own use of marijuana.

METHODS

Sample

The data for the participants in this study came from a residentially based random sample residing in one of two upstate New York counties who had been assessed for drug use first in 1983. The sample was based on an earlier study using maternal interviews in 1975. The original maternal/youth study was designed to assess problem behavior among youngsters. The 1983 sample (n=756) is the base from which the current sample was drawn.

The sampled families were generally representative of the population of families in Albany and Saratoga, two upstate New York counties,with respect to gender, family intactness, family income, and education. Albany County was identified as one of the poorest counties in the New York State, and adjacent Saratoga County as one of the wealthiest. These were chosen for study by means of a sample survey. Primary sampling units were created from enumeration districts and block groups, which, when taken together, comprised the entire area and population of the target counties. The primary sampling units in each county were stratified by urban/rural status, the proportion of Whites, and median income. A systematic sample of primary sampling units in each county was then drawn with probability proportional to the number of households, and probabilities equal for members of all strata. Segments of blocks were then selected with probability proportional to size (number of households), and each was surveyed in the field with a proportion of the households being selected according to the predetermined sampling ratio. Address lists were compiled in this process, and interviewers were sent to the selected addresses. Those households with at least one child between the ages of 1–10 years were qualified for the study. In each qualified household, the interviewer, by use of a set of Kish Tables, randomly selected one child from those in the appropriate age range.30

There was a close match of the participants on family income, maternal education, and family structure with the 1980 survey conducted by the U.S. Bureau of Census. For example, 75% of the children lived with married parents, and 19% lived with a mother who was not currently married; the census figures were 79% and 17%, respectively. Interviews of both mothers and youths were conducted in 1983 (T2, n = 756), 1985–1986 (T3, n = 739), and 1992 (T4, n = 750). Three more interviews of the second generation were conducted in 1997 (T5, n = 749), 2002 (T6, n = 673), and 2007 (T7, n = 606). Some of the participants who were not interviewed in previous years were interviewed in later waves. Retention rate has been over 95% until the most of the recent follow-ups, when it was 80%. Five percent refused to participate. Due to budget constraints, we were unable to interview the remaining 15%. The mean ages (SDs) of participants at the follow-up interviews were 14.05 (2.80) at T2, 16.26 (2.81) at T3, 22.28 (2.82) at T4, 26.99 (2.80) at T5, 31.90 (2.83) at T6, and 37.10 (2.84) at T7. The analyses for the current paper (n = 586) were based on those participants who completed both T6 and T7 interviews. In addition, the participants had to have completed the marijuana questions at both waves. The resulting number of participants was 586, which comprised 96% of those who were interviewed at T7. These participants were predominantly White (92%). Fifty-seven percent of the sample was female and 43% was male. We compared the participants who were present at T6 and T7 with the participants who were not present. The findings indicated that there were no differences between these two groups on the following measures: mean sibling marijuana use from T2–T4 (t = 0.32, p > 0.05), peer marijuana use at T5 (t = 1.90, p > 0.05), and significant other marijuana use at T5 (t=−1.53, p > 0.05). Extensively trained and supervised lay interviewers administered the interviews in private. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants and their mothers in 1983, 1986, and 1992, and from the participants only in 1997, 2002 and 2007. Approval for the use of human subjects was authorized by the Institutional Review Board of New York University School of Medicine. Additional information regarding the study methodology is available from prior publications.33

Measures

Measurement of Parental Marijuana Use History

Parental marijuana use history was assessed at T6. The respondent was asked the following question, “How much of the time when you were growing up did you have a parent (or step-parent) who smoked marijuana?” Answer options ranged from 1 (“not at all”) to 4 (“6 or more years”).

Measurement of Sibling Marijuana Use

Sibling marijuana use was assessed from T2–T4. For sibling marijuana use at each point in time, we asked the respondent to specify how many of his or her siblings used marijuana more than once a month. We calculated the mean scores of sibling marijuana use from T2–T4.

Measurement of Peer and Significant Other Marijuana Use

We measured peer and significant other marijuana use at T5. We asked the participant how many of his/her friends smoked marijuana at least once a month on average. The measure had a scale ranging from 1 (“none”) to 4 (“most”). For significant other marijuana use, we asked about the frequency of marijuana use by the respondent’s significant other. The options on this scale ranged from 1 (“never”) to 4 (“several times a month or more”).

Measurement of Participant’s Marijuana Use

Each participant’s marijuana use was assessed at T6 and at T7. At both time waves, we asked the respondent to indicate how many times, over the past two months, he or she had used marijuana. Options ranged from 1 (“not at all”) to 7 (“every day”).

Further descriptions of the measures can be found in Brook et al.11 These measures have proven to be stable over time and to predict psychopathology.34

Analysis

Using the LISREL VIII structural equation program,35 we tested the conceptual model presented in Figure 1. In order to account for the influences of the youths’ gender and age and paternal educational level on the structural models, we used partial covariance matrices as the input matrices, which were created by statistically partialing out the effects of these demographic factors on each of the original manifest variables. Fewer than 5% of the participants had missing values on one or more of the independent variables. For those participants with missing data, we used the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) approach to missing values. We then employed maximum likelihood methods to estimate the models by using LISREL VIII. We chose two indices of fit to assess the fit of the models: the LISREL goodness of fit index (GFI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). For the nested models, we used chi-square tests to determine the improvement of the model at each incremental step. The correlations among the variables derived from the covariance matrices are available from the authors upon request.

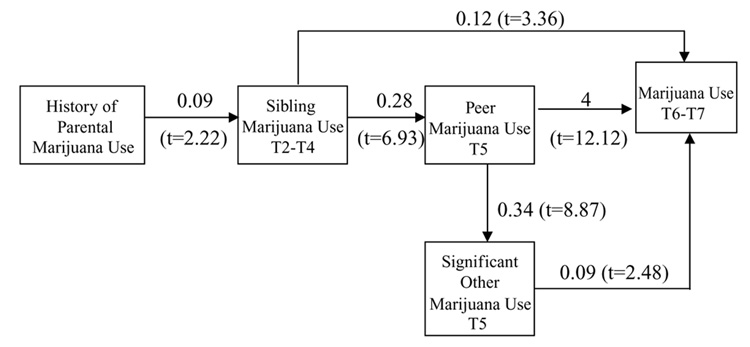

FIGURE 1.

Pathways to marijuana use in the fourth decade of life. 1. GFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.03. 2. Age, gender, and parental educational level were statistically controlled. 3. All pathways depicted were statistically significant (p < .05).

As covariates, we included the participant’s gender, age, and parental educational level. Gender was effect-coded (1 = male; 0 = female) such that positive gender coefficients indicated higher levels of the criterion for males and negative coefficients represented higher levels for females.

RESULTS

Figure 1 presents the final model with the standardized regression coefficients; larger standardized regression coefficients reflect a stronger association among the latent variables. The following indices of fit were obtained: GFI = 0.99 and RMSEA = 0.03. These results reflect a satisfactory model fit. As noted in Figure 1, the model depicted the following statistically significant paths:

a history of parental marijuana use had a path to sibling marijuana use (β = 0.09; t = 2.22), which in turn had a path to adult marijuana use at T6–T7 (β = 0.12; t = 3.36);

sibling marijuana use had a direct path to peer marijuana use (β = 0.28; t = 6.93);

peer marijuana use had a direct path to significant other marijuana use (β = 0.34; t = 8.87), as well as a direct path to adult marijuana use at T6–T7 (β = 0.46; t = 12.12);

significant other marijuana use had a direct path to adult marijuana use at T6–T7 (β = 0.09; t = 2.48).

An examination of the total effects of each variable estimated in the analysis of marijuana use at T6–T7 helps in the interpretation of the structural coefficients. Table 1 presents the standardized total effects analyses. The t values of the total effects of a history of parental marijuana use, sibling marijuana use, peer marijuana use, and significant other marijuana use on the participant’s own marijuana use at T6–T7 were statistically significant (each p <0.05). Peer marijuana use had the largest total effect on the participant’s marijuana use.

TABLE 1.

Predictors of Marijuana Use in the Fourth Decade of Life

| Independent variables | Marijuana use at T6–T7 β(t statistic) |

|---|---|

| History of parental marijuana use | 0.02 (2.10)* |

| Sibling marijuana use T2–T4 | 0.26 (6.45)† |

| Peer marijuana use T5 | 0.49 (13.66)† |

| Significant other marijuana use T5 | 0.09 (2.48)* |

Age, gender, and parental educational level were statistically controlled. Mean ages are as follows: 14.0 years (T2); 16.3 years (T3); 22.3 years (T4); 27.0 years (T5); 31.9 years (T6); 37.1 years (T7).

p < 0.05

p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Our hypothesis regarding the direct and indirect influences of marijuana use within the familial and non-familial environments was partially borne out. The central findings of this study are that earlier marijuana use within the familial environment (ie, parental and sibling marijuana use) was related to marijuana use in the non-familial environment (ie, among one’s peers and/or significant other), which in turn was related to the participants’ marijuana use in the fourth decade of life. Specifically, the influence of earlier parental marijuana use on their offspring’s later marijuana use as an adult was mediated through sibling marijuana use, which in turn was related to peer and significant other marijuana use. In addition, aspects of the familial environment (sibling marijuana use) and the non-familial environment (peer and significant other marijuana use) had direct effects on the participants’ marijuana use in the fourth decade of life. Another contribution of the present research is the role of peer marijuana use as a mediating factor. Peer marijuana use serves to mediate familial factors, predict significant other marijuana use, and be a direct link with the participant’s own marijuana use.

Consistency with Previous Research

Consistent with the literature, our results regarding the non-familial environment indicate a direct longitudinal relationship between peer marijuana use and one’s own marijuana use. The link between peer and participants’ marijuana and other illegal drug use is consistently maintained for adolescent.14,26–27 as well as young adult29,30 samples. The current longitudinal study is, therefore, in accord with prior investigators’ findings. Moreover, our results extend previous findings over a longer longitudinal time span, extending them to an older participant age (mean age, collapsed across two outcome assessments, = 34.5). Our study, then, serves to further emphasize the importance of the impact of the peer network in young adulthood on the individual’s marijuana use over time. Peer marijuana use was the strongest predictor of the participant’s marijuana use. Indeed, having friends who used marijuana had a greater influence on the individual’s use than did marijuana use among his or her significant other or family members.

Second, our finding of a direct longitudinal effect of the significant other’s marijuana use on the participant’s own marijuana use is likewise in line with earlier research; other investigators have found a direct relationship between the significant other’s marijuana use and one’s own marijuana use, in cross-sectional as well as short-term longitudinal studies.19,31

The longitudinal relationship between non-familial marijuana use and the participant’s own marijuana use indicates substantial modeling effects of the non-familial environment on marijuana use. This modeling effect is in accord with FIT, which emphasizes the role of peers and the significant other in serving as models for drug behavior, including marijuana use. However, as noted above, the relationship of peer marijuana use to the participant’s marijuana use, as compared to the influence of the significant other, appears to be larger.

Within the familial environment, the pathways demonstrated in the current study from sibling marijuana use to the participant’s marijuana use—with sibling marijuana use demonstrating direct as well as indirect paths—serve to buttress prior research. Though prior studies have found considerable concordance between sibling and participant drug use,17–19,21–23,28 researchers have rarely examined the specific pathways through which this concordance comes about. Our findings indicate that sibling marijuana use may not only directly affect the participant’s marijuana use, but, over time, has an indirect effect as well. As regards indirect effects, the individual is more likely to associate with peers who smoke marijuana if he or she has siblings who smoke marijuana. This finding reflects both the modeling effects of sibling marijuana use (in the direct effect of sibling marijuana use on the participant’s marijuana use) and assortative peer selection (in the relation between sibling marijuana smoking and peer marijuana smoking).

Last, the indirect effect of parental marijuana use seen here supports some prior work, but is not entirely consistent with other research. That is, the literature on the effect of parental marijuana and other illegal drug use on the participant’s own marijuana and other illegal drug use is somewhat inconsistent. Some studies, conducted on adolescent samples, have found direct effects of parental marijuana and other illegal drug use on the offspring’s marijuana use.14,20 Other studies, conversely, have obtained results similar to ours, whereby parental influence in this regard is indirect, and, although significant, relatively weak compared with the influence of other domains studied in this research.36 One interpretation of these findings is that parental effects are stronger in adolescence than in adulthood, as the non-familial environment becomes more prominent in the individual’s life by their 30s. These results may also account for our finding that parental marijuana use had a direct effect on sibling marijuana use, but an indirect effect on the participant’s marijuana use at a later age. Consequently, when describing the effects of parental marijuana use, one may have to examine the parental effects in the context of the developmental stage of the individual.

Although the effect of parental marijuana use on the participant’s marijuana use is indirect, parental marijuana use is of significance nonetheless. As noted by FIT, parents wield an influence on marijuana use in their offspring in part by influencing the non-familial environment. In this study, this non-familial environment includes the individual’s peers and significant other. Marijuana use by parents is a prominent factor contributing to the participant’s marijuana use. Moreover, the influence of the familial environment does not disappear over time, but is quite long-lasting, extending up to a mean age of 37 in the current study, and perhaps longer.

By way of summary, there is differential importance of two developmental mechanisms, modeling and selection, in explaining the participant’s marijuana use. Modeling is important in both familial and non-familial settings. Thus, the participants may imitate their parents’, siblings’, peers’, and partner’s marijuana use. The mechanism of selection is significant in understanding peers’ and partner’s influences on the adult marijuana use. In contrast, selection is relatively unimportant in explaining the effects of familial marijuana use. Prior research has found prevalence rates of marijuana use to be greater in males than in females.37 These results were supported in the current study as well, as males reported significantly greater levels of marijuana use than females. However, the specific mechanisms underlying marijuana use assessed here were similar for males and females. This implies that prevention and treatment programs may focus on similar mechanisms for males and females while still being sensitive to the fact that males are more likely to use marijuana than females.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample was predominantly White and included few minority group members. Future research should be undertaken to assess the generalizibility of these findings to other racial and ethnic groups. Second, although we employ structural equation modeling and our latent constructs are ordered temporally, we are limited in our ability to make inferences of a causal nature. Our study, then, assesses only several of the important influences on marijuana use, rather than taking into account the full constellation of factors (eg, genetic factors involved, peer network during adolescence, and the broader social context out of which marijuana use arises). Third, we do not have data on the age of the participants’ siblings. Future research would benefit from including as the age of the participants’ siblings in the analyses, as age of their siblings might affect the results. Fourth, peer and self marijuana use were assessed differently. However, the findings were highly significant. If identical measures had been used, the results may have been even stronger. Nevertheless, future research should attempt to use similar measures.

The current study, nonetheless, represents a distinct contribution to the literature with respect to the older age of the sample (ie, in the fourth decade of life) in the context of an extended time frame. Moreover, the study has highlighted the various pathways from marijuana use in the familial and non-familial environments to the participant’s marijuana use. The results of the study have important implications for prevention and treatment.

Implications for Prevention and Treatment

The respective pathways of influence of marijuana use within the non-familial and familial environments carry important implications for prevention and treatment. The direct effect of peer and significant other marijuana use over time on one’s own marijuana use reflects not only a short-term modeling influence of the non-familial environment, but an enduring one as well. It follows that adults whose peers and/or significant others smoke marijuana are at risk not only for the development or continuation of marijuana use themselves, but for use which can continue for a number of years. Prevention efforts, therefore, should focus on the social networks of young adults as a locus through which long-lasting marijuana habits are formed. In treatment, as well, clinicians should be cognizant that as long as the marijuana user is embedded in a peer group in which marijuana use is the norm or has a significant other who uses marijuana, he or she may remain at risk.

The effect of marijuana use in the familial environment suggests that parents and siblings serve as important role models for marijuana use. Not only does sibling marijuana use in adolescence and the early twenties directly predict the participant’s marijuana use in the thirties, it is in part through the marijuana use of those in the familial environment that individuals choose to associate with peers and significant others who smoke marijuana family members may supply the individual with marijuana as well. There is, then, a substantial public health incentive not only to teach parents to refrain from marijuana use themselves, but also for parents to take an active role in encouraging their children to choose friends and partners who do not engage in marijuana use. Clearly, then, those engaged in prevention and treatment efforts would be advised to take a comprehensive view of the social environments of marijuana users and potential marijuana users. To the extent that there is marijuana use in either the familial or non-familial environment, there is an increased likelihood of marijuana use by the individual. Both the familial and non-familial environments, therefore, need to be addressed in the prevention and treatment programs. The efficacy of such an approach should be assessed in future prevention and treatment studies.

Whether direct or indirect, the influence of familial and non-familial environments on marijuana use is highlighted, as well, by the longitudinal nature of our study. Marijuana use in either environment through adolescence and the twenties was associated with marijuana use years later, in the thirties. This further points to the importance of trying to ensure that the social environments of adolescents are free of marijuana use. Marijuana use in either the familial or non-familial environments may have an effect on the individual’s marijuana use that lasts for many years.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by grants #5K05 DA00244 and #5R01 DA003188 from the National Institute of Drug Abuse, Bethesda, Md., and grant #5R01 CA094845 from the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md., all awarded to Dr. Judith S. Brook.

Footnotes

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fliegel SE, Roth MD, Kleerup EC, Barsky SH, Simmons MS, Tashkin D. Tracheobronchial histopathology in habitual smokers of cocaine, marijuana, and/or tobacco. Chest. 1997;112:319–326. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth MD, Arora A, Barsky SH, et al. Airway inflammation in young marijuana smokers and tobacco smoke. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:928–937. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.3.9701026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor DR, Fergusson DM, Milne BJ, et al. A longitudinal study of the effects of tobacco and cannabis exposure on lung function in young adults. Addiction. 2002;97:1055–1061. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor DR, Poulton R, Moffitt TE, Ramankutty P, Sears MR. The respiratory effects of cannabis dependence in young adults. Addiction. 2000;95:1669–1677. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951116697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brook DW, Brook JS, Zhang C, Cohen P, Whiteman M. Drug use and the risk of major depressive disorder, alcohol dependence, and substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:1039–1044. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C, Wagner FA, Anthony JC. Marijuana use and the risk of major depressive episode: Epidemiological evidence from the United States National Comorbidity Survey. Soc Psychiatry and Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37:199–206. doi: 10.1007/s00127-002-0541-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M. The relationship between cannabis use, depression and anxiety among Australian adults: Findings from the National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Soc Psychiatry and Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36:219–227. doi: 10.1007/s001270170052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell N. Cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence and young adulthood. Addiction. 2002;97:1123–1135. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman AS, Terras A, Zhu W, McCallum J. Depression, negative self-image, and suicidal attempts as effects of substance use and substance dependence. J Addict Dis. 2004;23:55–69. doi: 10.1300/J069v23n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Os J, Bak M, Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Verdoux H. Cannabis use and psychosis: A longitudinal population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:319–327. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brook JS, Brook DW, Gordon AS, Whiteman M, Cohen P. The psychosocial etiology of adolescent drug use: A family interactional approach. Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr. 1990;116:111–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrews JA, Hops H, Duncan SC. Adolescent modeling of parent substance use: The moderating effect of the relationship with the parent. J Fam Psychol. 1997;11:259–270. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.11.3.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bahr SJ, Hoffman JP, Yang X. Parental and peer influences on the risk of adolescent drug use. J Prim Prev. 2005;26:529–551. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-0014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brook JS, Brook DW, Arencibia-Mireles O, Richter L, Whiteman M. Risk factors for adolescent marijuana use across cultures and across time. J Genet Psychol. 2001;162:357–374. doi: 10.1080/00221320109597489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brook JS, Brook DW, De La Rosa M, Whiteman M, Johnson E, Montoya I. Adolescent illegal drug use: The impact of personality, family, and environmental factors. J Behav Med. 2001;24:183–203. doi: 10.1023/a:1010714715534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duncan TE, Duncan SE, Hops H. The role of parents and older siblings in predicting adolescent substance use: Modeling development via structural equation latent growth modeling. J Fam Psychol. 1996;10:158–172. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Hops H, Stoolmiller M. An analysis of the relationship between parent and adolescent marijuana use via generalized estimating equation methodology. Multivariate Behavi Res. 1995;30:317–339. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3003_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hopfer CJ, Stallings MC, Hewitt JK, Crowley TJ. Family transmission of marijuana use, abuse, and dependence. J Am Acad Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:834–841. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046874.56865.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King KA, Vidourek RA, Wagner D. Effect of parent drug use and parent-child time spent together on adolescent involvement in alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. J Marriage Fam. 2003;3:171–176. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maes HH, Woodard CE, Murrelle L, et al. Tobacco, alcohol and drug use in eight- to sixteen-year-old twins: The Virginia Twin Study of Adolescent Behavioral Development. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:293–305. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brook JS, Brook DW, Whiteman M. Older sibling correlates of younger sibling drug use in the context of parent-child relations. Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr. 1999;125:451–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kendler KS, Prescott CA. Cannabis use, abuse, and dependence in a population-based sample of female twins. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1016–1022. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Neale MC, Prescott CA. Illicit psychoactive substance use, heavy use, abuse, and dependence in a U.S. population-based sample of male twins. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:261–269. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morojele NK, Brook JS. Adolescent precursors of marijuana and other illicit drug use among adult initiators. J Genet Psychol. 2001;162:430–450. doi: 10.1080/00221320109597494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beyers JM, Toumbourou JW, Catalano RF, Arthur MW, Hawkins JD. A cross-national comparison of risk and protective factors for adolescent substance use: The United States and Australia. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hussong AM, Hicks RE. Affect and peer context interactively impact adolescent substance use. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2003;31:413–426. doi: 10.1023/a:1023843618887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Windle M. Parental, sibling, and peer influences on adolescent substance use and alcohol problems. Appl Dev Sci. 2000;4:98–110. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrews JA, Tildesley E, Hops H, Fuzhong L. The influence of peers on young adult substance use. Health Psychol. 2002;21:349–357. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Sydow K, Lieb R, Pfister H, Hoefler M, Wittchen HU. What predicts incident use of cannabis and progression to abuse and dependence? A four-year prospective examination of risk factors in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;68:49–64. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leonard KE, Homish GG. Changes in marijuana use over the transition into marriage. J Drug Issues. 2005;35:409–429. doi: 10.1177/002204260503500209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bahr SJ, Maughan SL, Marcos AC, Li B. Family, religiosity, and the risk of adolescent drug use. J Marriage Fam. 1998;60:979–992. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen P, Cohen J. Life values and adolescent mental health. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum Associates; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brook JS, Kessler RC, Cohen P. The onset of marijuana use from preadolescence and early adolescence to young adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11:901–914. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL 8: Structural equation modeling with the SIMPLIS command language. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffman JP, Su SS. Parental substance use disorder, mediating variables and adolescent drug use: A non-recursive model. Addiction. 1998;93:1351–1364. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93913516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merline AC, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Substance use among adults 35 years of age: Prevalence, adulthood predictors, and impact of adolescent substance use. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:96–102. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]