Introduction

Currently, the diagnostic armamentarium of clinical cardiology lacks the ability to reliably identify the most frequent source of myocardial infarction, the inflammatory plaque [22]. The majority of infarcts are triggered by acute thrombotic closure of the coronary artery after a thin, fibrous cap ruptures and the thrombogenic core is exposed to blood. Often, these rupture prone lesions do not narrow the vessel lumen more then 50% [9], are therefore judged non-significant on x-ray coronary angiography, and do not receive the necessary therapeutic attention. The inflammatory plaque has been a target of intense scrutiny in cardiovascular molecular imaging research, because detection and treatment could significantly reduce the burden of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Molecular imaging has the potential to result in much earlier detection of subtle disease, assess prognosis and monitor therapeutic intervention [16, 40]. Several recent reviews have comprehensively examined the role of molecular imaging in cardiovascular disease and the interested reader is referred to these papers [14, 35]. In this manuscript we review recent advances in molecular imaging of vascular targets, focusing in particular on optical (fluorescence) and MR imaging techniques.

Optical and MR Imaging

MRI and fluorescence imaging have several attractive attributes that have driven the development of molecular imaging strategies for these modalities. First, no radiation is involved in either technique, which facilitates frequent and serial studies without imposing potentially hazardous radiation exposure on the patient. MRI provides high resolution images of the vessel wall with unsurpassed soft tissue contrast. MRI can be used to distinguish components of certain atherosclerotic plaques, such as those in the carotids, including their lipid cores and fibrous caps [37, 45]. In addition, the use of angiographic and phase contrast techniques allows MRI to assess the anatomical and physiological significance of plaque in the vessel wall.

Two groups of imaging agent are frequently used for vascular molecular MRI, magnetic nanoparticles (MNP) with a detection limit in the low nanomolar range, and novel gadolinium constructs in which large payloads of Gadolinium are loaded into a variety of delivery vehicles including liposomes, micelles and lipoproteins. The technology underlying MNP is extensively reviewed in this supplement in the article by Sosnovik and colleagues, and that of novel gadolinium based constructs by Waters and Wickline.

Clinical translation of vascular fluorescence imaging is still at an early stage, however, development of intravascular fluorescence catheters and sensitive detection systems may open this field in the near future [41, 46]. Currently, fluorescence imaging is a powerful technique in preclinical research, allowing one to obtain cellular and molecular information with microscopic resolution using invasive techniques. Completely noninvasive fluorescence molecular tomography (FMT) complements microscopy and provides 3D sub-millimeter resolution by capitalizing on the deep tissue penetration capabilities of NIR fluorescence. Current FMT has an in vivo detection limit of 1 picomol fluorochrome (10 nM) [25] and has recently been performed successfully in the heart in live mice with healing myocardial infarcts [24, 34]. Intravital microscopy [27] and fluorescence microscopy of tissue sections deliver molecular information on cellular and subcellular level [13, 15, 23].

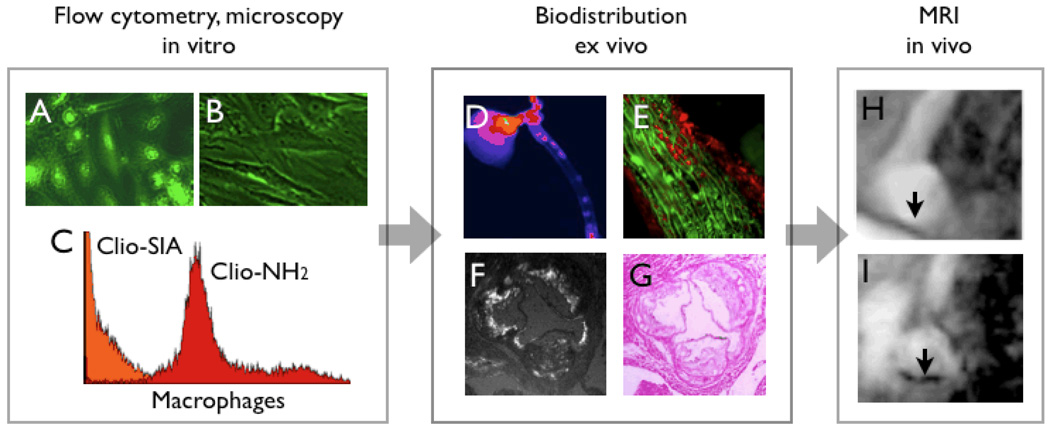

Hybrid magneto-fluorescent imaging agents have recently been developed for cardiovascular imaging [15, 23, 24]. While the ultimate clinical goal of developing a novel imaging agent may be in-vivo detection by MRI, derivatisation with fluorochromes enables probe validation by fluorescent microscopy and flow cytometry techniques (Fig. 1). In addition, ex vivo fluorescent imaging of target tissue or excised organs provides a fast and cost-effective step before embarking on sophisticated MRI to assess the in-vivo performance of a candidate probe (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Role of NIR fluorochromes in agent development and validation.

1A & B: fluorescence microscopy of endothelial cells which have been incubated with a targeted magnetofluorescent nanoparticle (A). The uptake can be competetively inhibited (B), which demonstrates specificity of a candidate agent.

1C: Incubation of murine peritoneal macrophages with magnetofluorescent nanoparticles with different surface modifications. Through small molecule surface modifications, it is possible to completely re-direct MNP from macrophages (red) to endothelial cells (orange).

1D: Fluorescence reflectance imaging of an excised aorta, after injection of magnetofluorescent nanoparticles into a mouse model with atherosclerosis. This approach allows for rapid and cost-effective analysis of agent performance.

1E–F: Fluorescent properties of nanoparticles allow for microscopic analysis of uptake. In 1E, uptake of the nanoparticle (red channel in fluorescence microscopy) into smooth muscle cells (green, immunoreactive staining for alpha actin) of the media underneath a plaque is shown. F & G demonstrate uptake into plaques in the aortic root of an apoE−/− mouse.

1H&I: Finally, more time- and costintensive in vivo vascular imaging demonstrates uptake of nanoparticles in T2* weighted gradient echo imaging of the aortic arch (I) [15].

Magnetic nanoparticles

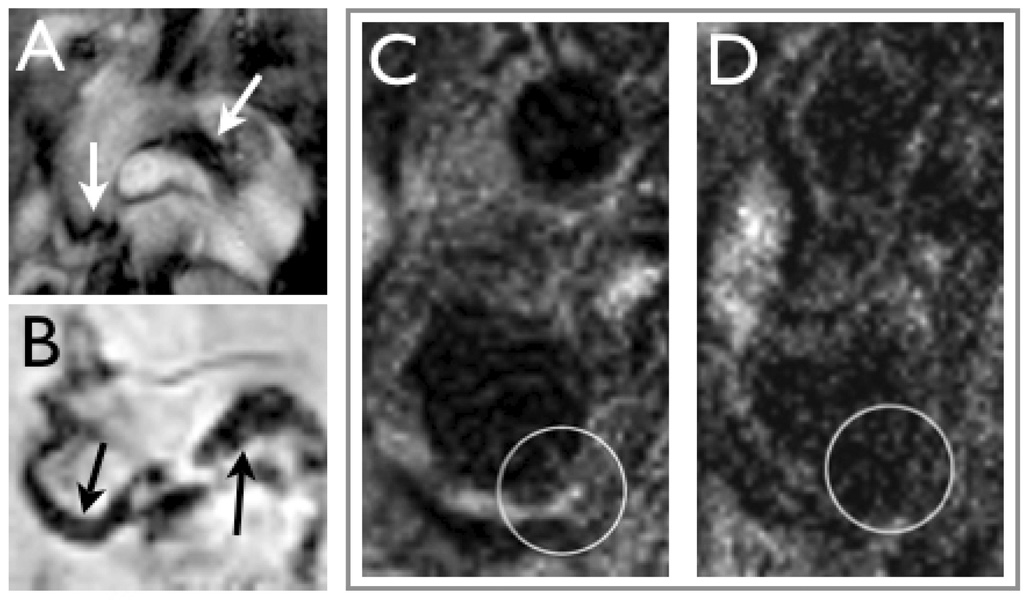

The largest preclinical and early clinical experience to date in the imaging of plaque macrophages has been with carbohydrate coated magnetic nanoparticles. Phagocytic ingestion of these nanoparticles by macrophages (and to lesser degree other cells) is a measure of plaque inflammation, and has been imaged in mice Fig (2A, B) [15, 21], large animal models such as rabbits [31, 32], and in human carotid arterial plaques (Fig 2C, D) [18, 38]. In a study using the hybrid magnetofluorescent nanoparticle CLIO-Cy5.5 in cholesterol fed apoE−/− mice, the exact cellular distribution of the nanoparticles has recently been characterized [15]. While the majority of CLIO-Cy5.5 was taken up by plaque macrophages, activated smooth muscle and endothelial cells also ingested the probe to a lesser degree [15]. A good correlation between in-vivo visualization of nanoparticles and the histological presence of macrophages has also consistently been found in large animal models and human trials [15, 18, 31, 32, 38].

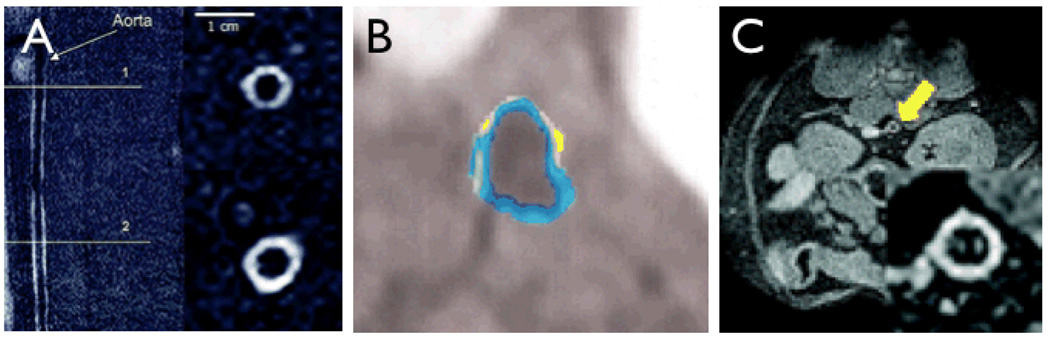

Figure 2. Macrophage imaging with magnetic nanoparticles.

2A: In vivo bright-blood aortic MR images of representative apoE−/− mice. Twenty-four hours following 15 mg Fe/kg of MNP injection, T2*-weighted gradient echo imaging was performed in a 9.4-T MR scanner.

Strong focal signal loss was observed in the aortic root and transverse aortic arch (arrows) [15].

2B: Ex vivo 14-T high-resolution aortic MRI of representative apoE−/− mouse that received MNP. Focal MRI signal loss was noted in the aortic root and transverse arch, similar to the in vivo images (arrows) [15].

2C&D: MRI of a carotid artery containing atherosclerotic plaques (circle) before (C) and after injection of MNP (D) in a patient [18].

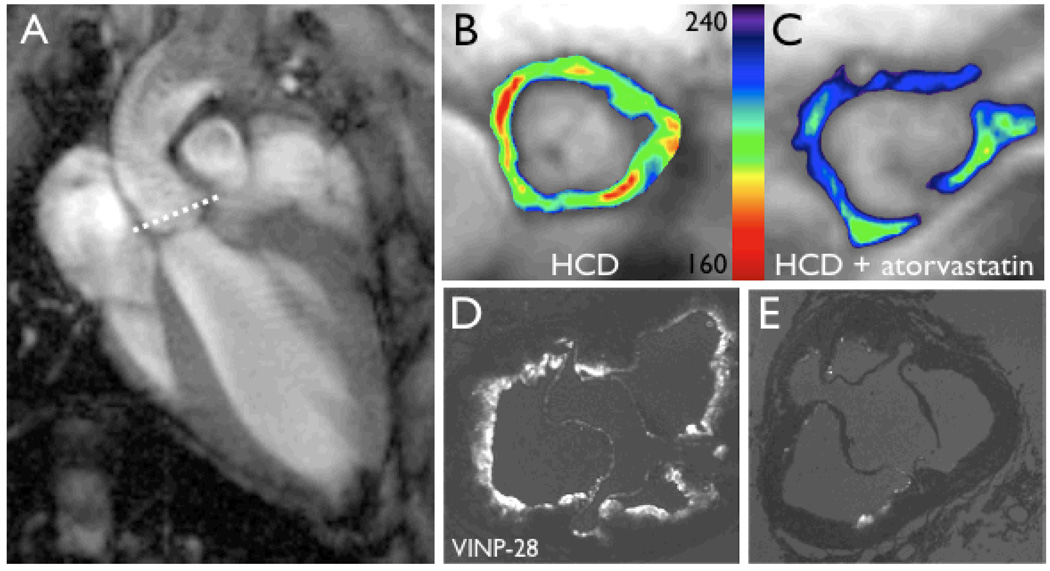

In the era of personalized and preventive medicine, one of the primary goals of molecular imaging is the detection of subclinical or early disease [40]. The development of probes for detection of endothelial adhesion molecules such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) [17, 23, 39] is thus of significant importance, since these targets are expressed early on in disease progression. VCAM-1 is expressed on activated endothelial cells, macrophages and smooth muscle cells and participates in the inflammatory initiation and progression of atherosclerotic plaques [7, 26]. Adhesion molecules mediate the recruitment of leukocytes to the plaque while facilitating their transmigration into the nascent atheromata [19]. Several generations of VCAM-1 targeted MR probes have thus been developed, using the magneto-fluorescent nanoparticle CLIO-Cy5.5 as a platform. The first of these agents used a VCAM-1 targeted antibody as an affinity ligand [39], followed by a cyclic peptide to bind to VCAM-1 [17]. Recently, a phage-derived linear peptide was employed to synthesize a 3rd generation probe with superior target affinity [23]. The major advance in this developmental effort is the increasing number of affinity ligands that were attached to one nanoparticle. Steric chemical constrains limited the number of antibodies to one or two per MNP, and was increased to 4 ligands in the case of the cyclic peptide. The surface of the most advanced version was decorated with as many as 20 peptides, thereby increasing target affinity substantially. The experience with the linear peptide based MNP strongly illustrates the potential of molecular MRI. VCAM-1 expression could be successfully imaged in the aortic roots of living apoE−/− mice using this probe (Fig. 3) [23]. In addition, the effect of statin treatment on VCAM-1 expression was detected in-vivo by demonstrating decreased probe accumulation in the aortic wall (Fig. 3B–E) [23]. This VCAM-1 sensing MNP thus detected a sparsely expressed target, and also demonstrated adequate dynamic range to detect a treatment effect. Another adhesion molecule, E-selectin (CD62E, endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule 1) is upregulated on endothelium by cytokines like IL-1β or TNFa, and imaging E-selectin may thus also provide a method of determining the activation state of the endothelium. Reynolds et al. targeted E-selectin with magnetofluorescent nanoparticles decorated with anti–murine monoclonal antibody to image an inflamed ear mouse model [29]. Funovics et al. have recently designed a MNP by attaching an E-selectin binding peptide to a CLIO nanoparticle at high valency (30 peptides/nanoparticle) [11]. To demonstrate the specificity in vivo, they employed a novel method consisting of the co-injection of a Cy5.5 labeled E-selectin MNP and a Cy3 labeled control MNP, and demonstrated a high ratio of Cy5.5 to Cy3 fluorescence.

Figure 3. In vivo imaging of VCAM-1 expression.

3A: The aortic root was chosen as an imaging region because it is an area with high plaque burden in apoE−/− mice, provides unique landmarks for exact slice repositioning in repetitive imaging studies, and sports excellent image contrast, because the aortic wall is surrounded by flowing blood.

3B & C: The treatment effect of statins on VCAM-1 expression was detected by non-invasive imaging after injection of a VCAM-1 targeted nanoparticle.

3D & E: Fluorescence microscopy corresponding to MRI shown in B & C [23].

Apoptosis plays an important role in the biology of atherosclerosis plaques, and cardiomyocyte apoptosis has been successfully imaged by MRI in mice in vivo using a magnetofluorescent annexin [36]. The role of this probe in the assessment of vulnerable plaque, however, remains to be defined.

Fluorescence imaging of proteolytic enzyme activity

Given the key role of proteases (in particular MMP and cathepsins) in the rupture of vulnerable plaques, several protease-activated optical imaging agents have been developed. In one of the first studies, a protease–activatable fluorescence sensor based on a polymeric scaffold that allows imaging of pan-cathepsin activity (pH dependent cleavage of cathepsins B > S,L,K) was employed [5]. The fully assembled scaffold of this agent consists of near infrared fluorochromes grafted onto a partially methoxypegylated poly-L-lysine. Proteolytic cleavage of the scaffold released the fluorochromes and results in extensive fluorescence generation (de-quenching) [42].

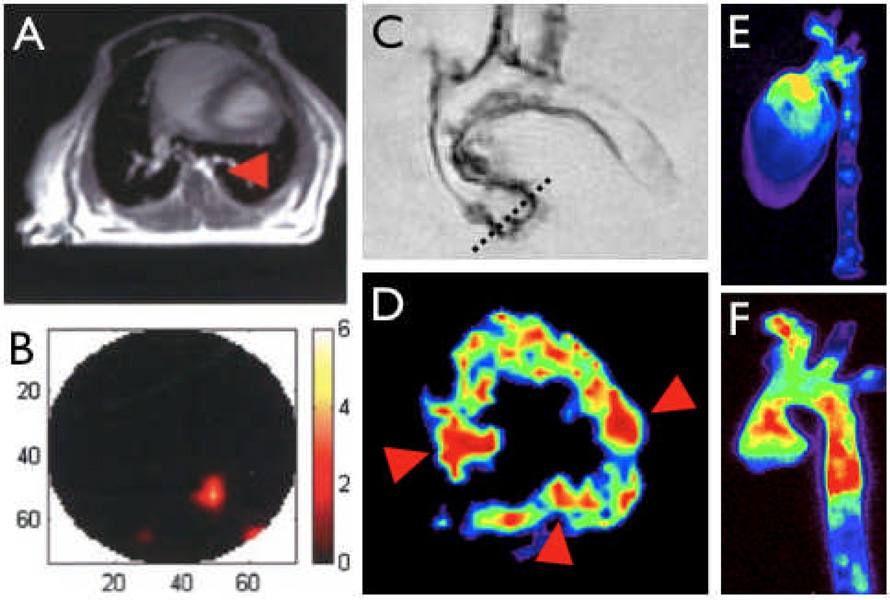

This agent has been used to image inflammation in macrophage and cathepsin rich atherosclerotic lesions by noninvasive fluorescence mediated tomography (Fig. 4A) [5]. Probe activation could also eventually be detected by using intravascular NIRF catheters during cardiac catheterization [46], or non-invasively in carotid arteries. Recently, NIRF substrates for gelatinases (MMP-2/gelatinase-A and MMP-9/gelatinase-B) [8] and cathepsin K [13] have been employed to image atherosclerotic apoE−/− mice, using a similar strategy of probe activation. In addition, an activatable probe was developed to selectively target cathepsin S [12].

Figure 4. Hybrid imaging.

4A&B: Image co-registration using MRI and FMT combine the excellent anatomical detail in MR imaging (A, arowhead depicts descending thoracic aorta) with the sensitive detection of optical reporters in FMT [41].

4C–F: Combination of multiple molecular imaging agents in consecutive sessions or simultaneous imaging enable interrogation of complex biological systems. In C, an excised aorta from an apoE−/− mouse injected with a VCAM-1 targeted MNP is shown. The dotted line outlines slice positioning for color coded T2 weighted short axis MRI of the aortic root (D), which shows enhanced uptake in the valve commissures (arrowheads). E & F show fluorescence reflectance imaging after injection of a macrophage-avid nanoparticle and a protease activatable agent [1].

Fusion and multiplex molecular imaging

Optical imaging modalities such as FMT [41] could benefit from integration with an anatomical imaging modality such as MRI or CT. Similar as in PET-CT or PET-MRI, anatomical detail can be used for more accurate reconstruction or molecular information. Secondly, visualization of molecular information onto anatomic maps affords maximum information content. Hybrid probes with reporter capabilities in 2 or more imaging modalities, e.g. nanoparticles with an iron oxide core for T2* weighted MRI which are derivatized with fluorochromes and/or PET tracers (64Cu, 18F), may further enhance the utility of these integrated imaging systems.

The combination of several molecular probes with different targets within one imaging session may be particularly valuable for solving complex basic research and clinical problems. Multispectral optical imaging is supported by fluorochromes which are excited at distinct and different wavelengths and imaging systems such as FMT and fluorescence microscopes with multi-channel capabilities. Using a panel of molecular imaging agents enables interrogation of integrated biological sytems, for instance by simultaneous imaging of macrophage phagocytic and proteolytic activity [24]. In a study aiming to investigate aortic valve degeneration, expression of VCAM-1, macrophage recruitment, protease activity and early calcification was investigated with a multiplex imaging approach (Fig. 4B) [1].

Gadolinium based probes

Beyond the conventional lanthanide chelates with rapid distribution and renal clearance, a number of newer Gd containing compounds have been described recently. Gadofluorine is a fluorinated chelate of gadolinium which is more lipophilic and has a longer circulation half-life. In a rabbit model of atherosclerosis, gadoflourine accumulated preferentially in lipid rich atherosclerotic plaques (Fig. 5A) [3, 33]. A gadolinium containing liposome targeted to the αvβ3 integrin has been used to image local increase in angiogenesis in a rabbit model of atherosclerosis (Fig. 5B) [43]. A theranostic approach that combined anti-angiogenic therapy with imaging has also been described, which was achieved by incorporation of the anti-angiogenic agent fumagillin into the liposome [44]. Subsequently, a decreased uptake of the probe indicated reduced plaque angiogenesis. Recombinant HDL-like nanoparticles containing Gadolinium have been proposed as a platform for molecular MRI of atherosclerosis [10], and have been shown to accumulate in atherosclerotic plaques (Figure 5C). The rate of uptake of HDL-like nanoparticles into the plaques of apoE−/− mice was correlated to the lipid and macrophage content of the plaque. Plaques with a high macrophage density tended to accumulate the probe quicker than those with a low macrophage content [10]. Plaque macrophages in apoE−/− mice have also been targeted with a gadolinium containing micelle decorated with an antibody targeted to the macrophage scavenger receptor [2, 20].

Figure 5. Atherosclerosis imaging with Gadolinium based probes.

5A: Detection of lipid-rich atherosclerotic plaques in a rabbit model with gadofluorine [33].

5B: Imaging of angiogenesis in atherosclerosis with a Gadolinium containing liposome which is targeted to the αvβ3 integrin [43].

5C: In a rabbit model of atherosclerosis, lipid-rich plaques take up recombinant HDL-like nanoparticles and are detected by MRI [10].

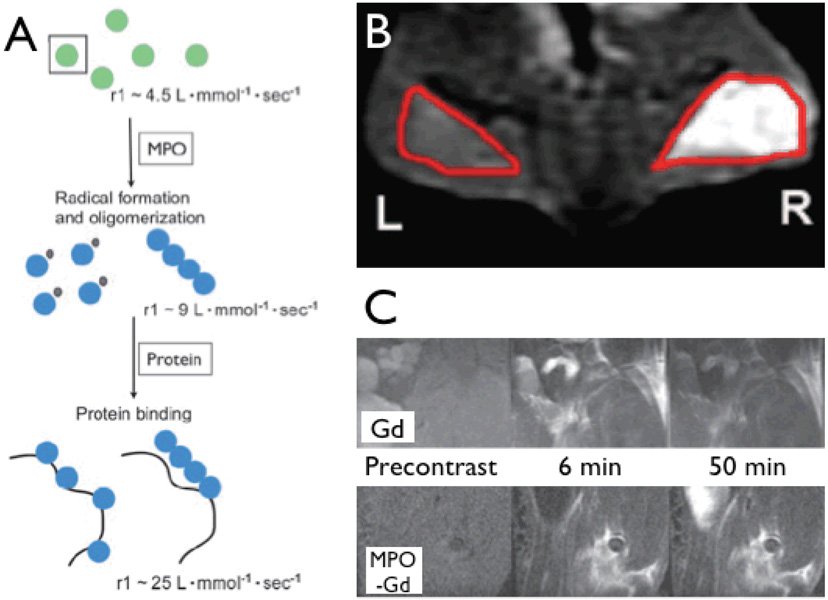

Recently, Chen et al. reported on the use of a Gd containing myeloperoxidase sensitive imaging agent (gadolinium-5-hydroxytryptamide-DOTA or gadolinium-bis-5-hydroxytryptamide-DTPA) [6]. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) is primarily produced by neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages and is abundant in atherosclerotic lesions. Indeed, plasma levels of MPO have been used as a biomarker for prognosis [4]. Myeloperoxidase induces oligomerization of the substrate in addition to local incorporation into proteins, both increasing R1 relaxivity and trapping end-products locally. Combined, these mechanisms result in higher high target-to-background ratios (Fig. 6A). Using a murine model of MPO-containing matrigel implantation and myositis, the strategy was successfully applied for in-vivo imaging (Fig. 6B, C) [6], and has recently been applied to image inflamed atherosclerotic lesions in a rabbit model [30]. Another approach based on iron oxide nanoparticles and magnetisation switch effects has also been described [28]. Ongoing investigation in animal models of atherosclerosis and vasculitis will determine the utility of these MPO sensors for vascular targets.

Figure 6. Imaging of myeloperoxidase activity.

6A: Mechanisms of action for myeloperoxidase (MPO)-sensitive contrast agents. After activation by myeloperoxidase, imaging agents are radicalized to form oligomers. Blue spheres indicate the formation of myeloperoxidase-activated complexes. The oligomers have a higher T1 relaxivity and exhibit slower wash out kinetics due to cross linking with matrix proteins.

6B: Coronal 1.5Tesla fat-saturated MR images after injection with bis-5-HT-DTPA. The right side (R) contains human myeloperoxidase embedded in a basement membrane matrix gel and the left side (L) contains only the basement membrane matrix gel. Note that there is a substantial increase in contrast material enhancement on the right side of the mice. Red outlines indicate the regions of the implants.

6C: Sagittal 4.7-T fat-saturated MR images in mice with LPS-induced myositis. Mice were injected with Gd-DTPA (Gd, upper panel), which was used as a control, and Gd-5-HT-DOTA (MPO-Gd, lower panel). A washout of contrast material enhancement can be seen in Gd injected mice at 50 minutes, however, a noticeable increase in contrast material enhancement could still be seen at 50 minutes in MPO-Gd injected mice [6].

Outlook

Within the near future, we will witness a change of paradigm in vascular imaging, which is empowered by advances in imaging technology and reporters probes. Instead of simply following the physical distribution of established contrast agents as is current clinical standard in x-ray coronary angiography, we will have the opportunity to noninvasively image biological processes such as enzyme and cellular activity, and interaction with cell surface markers. These advancements open up new avenues in basic cardiovascular research and will speed up the pace of discovery. Clinical translation of these strategies will ultimately lead to more timely and precise diagnostics, and thereby enable personalized and preventive medicine.

Acknowledgments

Support Sources: RO1-HL078641 (RW), UO1-HL080731 (RW), D.W. Reynolds foundation (RW), K08 HL079984 (DS)

References

- 1.Aikawa E, Nahrendorf M, Sosnovik D, Lok VM, Jaffer FA, Aikawa M, Weissleder R. Multimodality molecular imaging identifies proteolytic and osteogenic activities in early aortic valve disease. Circulation. 2007;115:377–386. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.654913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amirbekian V, Lipinski MJ, Briley-Saebo KC, Amirbekian S, Aguinaldo JG, Weinreb DB, Vucic E, Frias JC, Hyafil F, Mani V, Fisher EA, Fayad ZA. Detecting and assessing macrophages in vivo to evaluate atherosclerosis noninvasively using molecular MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:961–966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606281104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barkhausen J, Ebert W, Heyer C, Debatin JF, Weinmann HJ. Detection of atherosclerotic plaque with Gadofluorine-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2003;108:605–609. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000079099.36306.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan ML, Penn MS, Van Lente F, Nambi V, Shishehbor MH, Aviles RJ, Goormastic M, Pepoy ML, McErlean ES, Topol EJ, Nissen SE, Hazen SL. Prognostic value of myeloperoxidase in patients with chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1595–1604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J, Tung CH, Mahmood U, Ntziachristos V, Gyurko R, Fishman MC, Huang PL, Weissleder R. In vivo imaging of proteolytic activity in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:2766–2771. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000017860.20619.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen JW, Querol Sans M, Bogdanov A, Jr, Weissleder R. Imaging of myeloperoxidase in mice by using novel amplifiable paramagnetic substrates. Radiology. 2006;240:473–481. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2402050994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cybulsky MI, Gimbrone MA., Jr Endothelial expression of a mononuclear leukocyte adhesion molecule during atherogenesis. Science. 1991;251:788–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1990440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deguchi JO, Aikawa M, Tung CH, Aikawa E, Kim DE, Ntziachristos V, Weissleder R, Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: visualizing matrix metalloproteinase action in macrophages in vivo. Circulation. 2006;114:55–62. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.619056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falk E, Shah PK, Fuster V. Coronary plaque disruption. Circulation. 1995;92:657–671. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frias JC, Williams KJ, Fisher EA, Fayad ZA. Recombinant HDL-like nanoparticles: a specific contrast agent for MRI of atherosclerotic plaques. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:16316–16317. doi: 10.1021/ja044911a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funovics M, Montet X, Reynolds F, Weissleder R, Josephson L. Nanoparticles for the optical imaging of tumor E-selectin. Neoplasia. 2005;7:904–911. doi: 10.1593/neo.05352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galande AK, Hilderbrand SA, Weissleder R, Tung CH. Enzyme-targeted fluorescent imaging probes on a multiple antigenic peptide core. J Med Chem. 2006;49:4715–4720. doi: 10.1021/jm051001a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaffer FA, Kim DE, Quinti L, Tung CH, Aikawa E, Pande AN, Kohler RH, Shi GP, Libby P, Weissleder R. Optical visualization of cathepsin K activity in atherosclerosis with a novel, protease-activatable fluorescence sensor. Circulation. 2007;115:2292–2298. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.660340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaffer FA, Libby P, Weissleder R. Molecular and cellular imaging of atherosclerosis: emerging applications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1328–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaffer FA, Nahrendorf M, Sosnovik D, Kelly KA, Aikawa E, Weissleder R. Cellular imaging of inflammation in atherosclerosis using magnetofluorescent nanomaterials. Mol Imaging. 2006;5:85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaffer FA, Weissleder R. Molecular imaging in the clinical arena. Jama. 2005;293:855–862. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.7.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly KA, Allport JR, Tsourkas A, Shinde-Patil VR, Josephson L, Weissleder R. Detection of vascular adhesion molecule-1 expression using a novel multimodal nanoparticle. Circ Res. 2005;96:327–336. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000155722.17881.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kooi ME, Cappendijk VC, Cleutjens KB, Kessels AG, Kitslaar PJ, Borgers M, Frederik PM, Daemen MJ, van Engelshoven JM. Accumulation of ultrasmall superparamagnetic particles of iron oxide in human atherosclerotic plaques can be detected by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2003;107:2453–2458. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000068315.98705.CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420:868–874. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipinski MJ, Amirbekian V, Frias JC, Aguinaldo JG, Mani V, Briley-Saebo KC, Fuster V, Fallon JT, Fisher EA, Fayad ZA. MRI to detect atherosclerosis with gadolinium-containing immunomicelles targeting the macrophage scavenger receptor. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:601–610. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Litovsky S, Madjid M, Zarrabi A, Casscells SW, Willerson JT, Naghavi M. Superparamagnetic iron oxide-based method for quantifying recruitment of monocytes to mouse atherosclerotic lesions in vivo: enhancement by tissue necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1beta, and interferon-gamma. Circulation. 2003;107:1545–1549. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000055323.57885.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naghavi M, Libby P, Falk E, Casscells SW, Litovsky S, Rumberger J, Badimon JJ, Stefanadis C, Moreno P, Pasterkamp G, Fayad Z, Stone PH, Waxman S, Raggi P, Madjid M, Zarrabi A, Burke A, Yuan C, Fitzgerald PJ, Siscovick DS, de Korte CL, Aikawa M, Airaksinen KE, Assmann G, Becker CR, Chesebro JH, Farb A, Galis ZS, Jackson C, Jang IK, Koenig W, Lodder RA, March K, Demirovic J, Navab M, Priori SG, Rekhter MD, Bahr R, Grundy SM, Mehran R, Colombo A, Boerwinkle E, Ballantyne C, Insull W, Jr, Schwartz RS, Vogel R, Serruys PW, Hansson GK, Faxon DP, Kaul S, Drexler H, Greenland P, Muller JE, Virmani R, Ridker PM, Zipes DP, Shah PK, Willerson JT. From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient: a call for new definitions and risk assessment strategies: Part II. Circulation. 2003;108:1772–1778. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000087481.55887.C9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nahrendorf M, Jaffer FA, Kelly KA, Sosnovik DE, Aikawa E, Libby P, Weissleder R. Noninvasive vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 imaging identifies inflammatory activation of cells in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2006;114:1504–1511. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.646380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nahrendorf M, Sosnovik DE, Waterman P, Swirski FK, Pande AN, Aikawa E, Figueiredo JL, Pittet MJ, Weissleder R. Dual channel optical tomographic imaging of leukocyte recruitment and protease activity in the healing myocardial infarct. Circ Res. 2007;100:1218–1225. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000265064.46075.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ntziachristos V, Tung CH, Bremer C, Weissleder R. Fluorescence molecular tomography resolves protease activity in vivo. Nat Med. 2002;8:757–760. doi: 10.1038/nm729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Brien KD, Allen MD, McDonald TO, Chait A, Harlan JM, Fishbein D, McCarty J, Ferguson M, Hudkins K, Benjamin CD, et al. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 is expressed in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques. Implications for the mode of progression of advanced coronary atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:945–951. doi: 10.1172/JCI116670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pande AN, Kohler RH, Aikawa E, Weissleder R, Jaffer FA. Detection of macrophage activity in atherosclerosis in vivo using multichannel, high-resolution laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. J Biomed Opt. 2006;11:021009. doi: 10.1117/1.2186337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perez JM, Simeone J, Tsourkas A, Josephson L, Weissleder R. Peroxidase substrate nanosensors for MR imaging. Nano Letters. 2003;4:119–122. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reynolds PR, Larkman DJ, Haskard DO, Hajnal JV, Kennea NL, George AJ, Edwards AD. Detection of vascular expression of E-selectin in vivo with MR imaging. Radiology. 2006;241:469–476. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2412050490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ronald J, Chen JW, Rogers K, Querol M, Bogdanov A, Rutt B, Weissleder R. Molecular imaging of myeloperoxidase activity in rabbit atherosclerotic plaques. Big Island, HI: Abstract, Society of Molecular Imaging; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruehm SG, Corot C, Vogt P, Kolb S, Debatin JF. Magnetic resonance imaging of atherosclerotic plaque with ultrasmall superparamagnetic particles of iron oxide in hyperlipidemic rabbits. Circulation. 2001;103:415–422. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmitz SA, Coupland SE, Gust R, Winterhalter S, Wagner S, Kresse M, Semmler W, Wolf KJ. Superparamagnetic iron oxide-enhanced MRI of atherosclerotic plaques in Watanabe hereditable hyperlipidemic rabbits. Invest Radiol. 2000;35:460–471. doi: 10.1097/00004424-200008000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sirol M, Itskovich VV, Mani V, Aguinaldo JG, Fallon JT, Misselwitz B, Weinmann HJ, Fuster V, Toussaint JF, Fayad ZA. Lipid-rich atherosclerotic plaques detected by gadofluorine-enhanced in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2004;109:2890–2896. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129310.17277.E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sosnovik DE, Nahrendorf M, Deliolanis N, Novikov M, Aikawa E, Josephson L, Rosenzweig A, Weissleder R, Ntziachristos V. Fluorescence tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of myocardial macrophage infiltration in infarcted myocardium in vivo. Circulation. 2007;115:1384–1391. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.663351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sosnovik DE, Nahrendorf M, Weissleder R. Molecular magnetic resonance imaging in cardiovascular medicine. Circulation. 2007;115:2076–2086. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.658930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sosnovik DE, Schellenberger EA, Nahrendorf M, Novikov MS, Matsui T, Dai G, Reynolds F, Grazette L, Rosenzweig A, Weissleder R, Josephson L. Magnetic resonance imaging of cardiomyocyte apoptosis with a novel magneto-optical nanoparticle. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:718–724. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toussaint JF, LaMuraglia GM, Southern JF, Fuster V, Kantor HL. Magnetic resonance images lipid, fibrous, calcified, hemorrhagic, and thrombotic components of human atherosclerosis in vivo. Circulation. 1996;94:932–938. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.5.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trivedi RA, JM UK-I, Graves MJ, Cross JJ, Horsley J, Goddard MJ, Skepper JN, Quartey G, Warburton E, Joubert I, Wang L, Kirkpatrick PJ, Brown J, Gillard JH. In vivo detection of macrophages in human carotid atheroma: temporal dependence of ultrasmall superparamagnetic particles of iron oxide-enhanced MRI. Stroke. 2004;35:1631–1635. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000131268.50418.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsourkas A, Shinde-Patil VR, Kelly KA, Patel P, Wolley A, Allport JR, Weissleder R. In vivo imaging of activated endothelium using an anti-VCAM-1 magnetooptical probe. Bioconjug Chem. 2005;16:576–581. doi: 10.1021/bc050002e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weissleder R. Molecular imaging in cancer. Science. 2006;312:1168–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.1125949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weissleder R, Ntziachristos V. Shedding light onto live molecular targets. Nat Med. 2003;9:123–128. doi: 10.1038/nm0103-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weissleder R, Tung CH, Mahmood U, Bogdanov A., Jr In vivo imaging of tumors with protease-activated near-infrared fluorescent probes. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:375–378. doi: 10.1038/7933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winter PM, Morawski AM, Caruthers SD, Fuhrhop RW, Zhang H, Williams TA, Allen JS, Lacy EK, Robertson JD, Lanza GM, Wickline SA. Molecular imaging of angiogenesis in early-stage atherosclerosis with alpha(v)beta3-integrin-targeted nanoparticles. Circulation. 2003;108:2270–2274. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093185.16083.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winter PM, Neubauer AM, Caruthers SD, Harris TD, Robertson JD, Williams TA, Schmieder AH, Hu G, Allen JS, Lacy EK, Zhang H, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Endothelial alpha(v)beta3 integrin-targeted fumagillin nanoparticles inhibit angiogenesis in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2103–2109. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000235724.11299.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan C, Mitsumori LM, Ferguson MS, Polissar NL, Echelard D, Ortiz G, Small R, Davies JW, Kerwin WS, Hatsukami TS. In vivo accuracy of multispectral magnetic resonance imaging for identifying lipid-rich necrotic cores and intraplaque hemorrhage in advanced human carotid plaques. Circulation. 2001;104:2051–2056. doi: 10.1161/hc4201.097839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu B, Jaffer FA, Ntziachristos V, Weissleder R. Development of a near infrared fluorescence catheter: operating characteristics and feasibility for atherosclerotic plaque detection. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2005:2701–2707. [Google Scholar]