While protein film voltammetry (PFV) frequently makes use of pyrolytic graphite edge (PGE) electrodes as a suitable surface for the study of biological macromolecules,1 few studies have reported the comparison of PFV as a function of electrode material, with the notable exception of blue copper protein azurin.2 Here we report that upon PGE electrodes, bacterial cytochromes c551 (cyts c) and mitochondrial cyt c can undergo a spontaneous chemical reaction at neutral pH values, which we describe in terms of the loss of the methionine ligand of the heme iron. Additionally, the native conformation of the bacterial cyts c can be studied in the same experiment. These data contrast with reports of cyts c electrochemistry that utilize alkanethiol modified gold electrodes,3 which do not show the spontaneous lower-potential product. Further, by comparison with horse heart cyt c, we show that there is a systematic reciprocal correlation of the relative stability of the Met-Fe interaction, and the propensity for generation of a stable, low-potential form of cyts c at the PGE electrode.

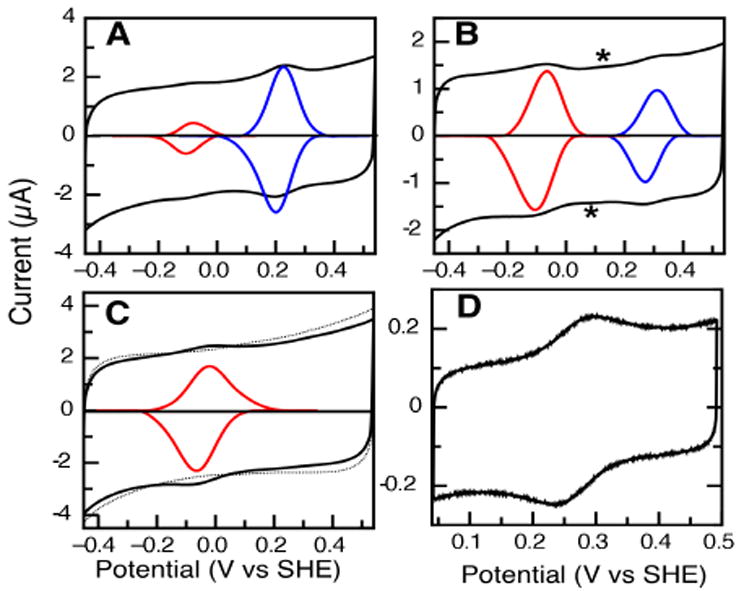

Monoheme, Class I ferricytochromes c were studied by direct adsorption upon a freshly polished, chilled PGE electrode, and subjected to PFV. Figure 1 illustrates that for a series of analogous cyts c, the PFV experiment revealed not one electrochemical response, but two: a pair of reversible voltammetric features at approximately +250 mV, the typical cyt c Fe(II/III) couple, and a lower potential feature at approximately -100 mV (vs SHE). Baseline-subtracted data for these features are shown in the insets of Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Typical PFV data for cyts c from (A) HT, (B) PA, and (C) HH collected for identical conditions at PGE electrodes. Raw data are shown in the solid black line, the inset data are baseline-subtracted, to highlight the different populations of low potential (red) and higher potential forms for the cytochrome (blue). Background features of the PGE electrode are indicated by an asterisk (*). All data were collected at pH 6.0 (phosphate/citrate buffer), 200 mM NaCl, scan rate = 200 mV/s, temperature = 10°C. (D) Bulk-phase voltammogram of HH cyt c at a PGE electrode. Experimental parameters: scan rate = 20 mV/s, temperature = 20 °C, pH 8.0, 5 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl.

As shown in Table 1, the higher potential redox couples (Figure 1, blue traces) measured here with PGE electrodes agree with previous measurements conducted using gold self-assembled monolayer-modified gold electrodes (Au-SAMs) for cyt c551 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) and cyt c552 from Hydrogenobacter thermophilus (HT). For example, HT wild-type cyt c shows a modest shift (25 mV) downward in potential when comparing PGE to Au-SAM measurements, and the PA cyt c measurements are identical within experimental uncertainty.3 Thus, part of the PFV response indicates the anticipated Fe(II/III) couple, though it is clear that the horse heart (HH) cyt c results differ (Figure 1C), showing a lower potential signal at the PGE electrode only.

Table 1.

| Native |

Met-loss |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Em (mV) | ΔEm | Em (mV) | ΔEm |

| HT WT | 211 ± 1 | n.a. | -110 ± 1 | n.a. |

| Q64N | 217 ± 1 | +6 | -103 ± 2 | +7 |

| Q64V | 189 ± 1 | -22 | -102 ± 2 | +8 |

| Q64Y | 177 ± 3 | -34 | -104 ± 2 | +6 |

| Unfolded WTa | n.d. | -- | -74 ± 4 | +36 |

| PA WT | 277 ± 1 | n.a. | -89 ± 2 | n.a |

| N64Q | 252 ± 1 | -25 | -83 ± 2 | +6 |

| N64V | 223 ± 1 | -55 | -85 ± 2 | +5 |

| Unfolded WTb | n.d. | -- | -91 ± 5 | |

| HH WT | 260 ± 5 | n.a. | -52 ± 1 | n.a. |

| Unfoldeda | n.d. | -- | -62 ± 1 | -10 |

Midpoint potentials of native and Met-loss form, collected at pH 6.0, 10°C. The listed value is the average of at least three trials and error is given as the standard deviation.

Midpoint potential (Em) was determined in pH 6.0 citrate + KPi, 30°C, plus 8M GdnHCl.

Midpoint potential (Em) was determined in pH 6.0 citrate/KPi, 10°C, 8M GdnHCl.

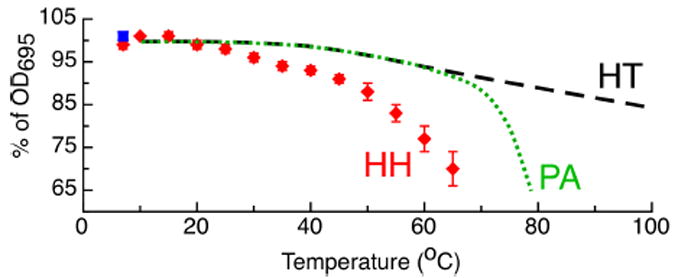

All of the His/Met ligated c-type cytochromes studied here at graphitic electrodes show the existence of the lower-potential form, and HH cyt c yields essentially 100% of the lower-potential signal. Similar PFV studies using PGE to interrogate cyts c6 (from A. thaliana and P. laminosum) have revealed an unknown signal that mirrors the lower-potential couples reported here.4 Our observation of similar, lower-potential couples in different His/Met cyts c suggests that a similar state of cyt c can be attained at PGE electrodes, regardless of the source of the cyt c. We hypothesize that the extent to which the lower-potential form is present at the electrode correlates with the propensity for the loss of the Met-ligand, i.e., the lower-potential signal corresponds to a “Met-loss form” of each cyt c. In this model, the extent to which the Met-loss form is observed will scale inversely with the stability of the Fe-Met interaction. While the bond strength of the Fe-Met bond is unknown presently, the intensity of the 695 nm visible absorption band of ferric cyts c can be used as an approximate indicator of the stability of the Fe-Met interaction; loss of intensity of the band has been interpreted as the loss of the Met ligand.5 We have repeated literature reports5 of the heat-induced loss of the 695 nm band for HH cyt c as a way of approximating the relative stability of the Fe-Met bond, and compared this with previously published data for the PA and HT proteins.6 As shown in Figure 2, the HH cyt c has the least stable Met-Fe interaction (while PA is more stable and HT the most stable). Thus, we surmise that low-potential form observed in Figure 1 (red inset) is due to a similar Met-loss form of each cyt c.

Figure 2.

Percent intensity of the 695 nm absorption band for HH cyt c (red diamonds) which can be regained by cooling the sample (blue square). Representative data for PA and HT are taken from Ref. 6.

We have found that generation of the Met-loss form is induced by adsorption upon PGE specifically. In contrast to the PFV experiments conducted in an immobilized mode, the bulk phase voltammetry of HH cyt c yields the normal, higher potential form over a limited scan range (Figure 1D, and Ref 7). As shown in Figure 1D, HH cyt c reveals a typical potential of +260 mV when in the bulk phase. In comparison with Figure 1C, it is clear that the adsorbed vs. bulk phase voltammetry changes the observation of the Met-loss product drastically. The generation of the Met-loss form may be tied to the specific range of potential used: while in the immobilized mode the conversion of HH cyt c to the Met-loss form is complete, in the bulk-phase experiment, some of the Met-loss product can be observed by using an expanded scan range (Figure S1). The normal form of HH cyt c does not adsorb onto PGE significantly, while the lower-potential form does.

To determine that our presumed Met-loss form does not represent entirely unfolded cyts c, we have pursued several lines of inquiry. First, we compared the Met-loss potentials with values for cyts c that are chemically unfolded with guanidine hydrochloride (Gdn) (Table 1). The chemically unfolded cytochromes are likely to have retained the proximal His ligand,8 and for chemically unfolded cyts c, we observe only a low potential signal at PGE (Table 1). For each protein, the data on chemically unfolded forms are similar to the respective Met-loss form; but notably for HT and HH proteins, the data are not identical to the Met-loss form. Further, we have found that the difference in potential between chemical unfolding and PGE-induced loss of the Met ligand is unlikely to be due to the high ionic strength associated with high Gdn concentrations. As Figure S2 shows, molar concentrations of salt (NaCl) have minimal impact upon the observed potentials of either the normal form or the Met-loss form. We have also investigated mutations in 64 position (PA numbering scheme) that are known to interact with the Met ligand.6 We observed that mutation of the 64 position significantly perturbs the potential of the normal FeIII/II couple (ΔEm values, Table 1), in correspondence with previous studies,6 but that there is minimal change upon the Met-loss form potential, indicating that the Met-donating loop is no longer contributing the coordination environment.

We have considered that the observed Met-loss form might be indicative of an “alkaline-transition” characterized by loss of the Met ligand and binding of an alternative endogenous ligand at the heme iron.9-11 However, the Met-loss form described here displays a potential approximately 100 mV more positive than the alkaline conformers reported for yeast iso-1-cyts c.9,10 The pH dependence of Em for the Met-loss form (shown for PA cyt c in Figure S3) is also distinct from that observed for the alkaline conformation of yeast iso-1-cyt c.9,10 Further, the PA and HT cyts c lack the Lys residues on the Met-donating loop thought to contribute the nitrogenous ligand of the alkaline conformer, and there is no evidence for the swapping of an unidentified nitrogen-based ligand to unfolded PA cyt c551.12 Finally, addition of exogenous imidazole to the Met-loss form results in a strong, negative shift of Em (−140 mV), suggesting that for the Met-loss couple, the heme iron possesses an exchangeable sixth ligand, e.g., water (Figure S4). The aggregate of these data indicate that when adsorbed on PGE, His/Met cyts c undergo a similar (yet different) reaction to the generation of alkaline conformers.

Thus, we have shown that while PGE is deemed a biologically “friendly” electrode surface,1 it has the ability to interact with His/Met-ligated cyts c to promote the loss of the relatively labile Met ligand, and result in a lower potential form of the cyt c. These data evoke the recent demonstration that interaction of mitochondrial cyt c with phospholipids such as cardiolipin can also dramatically lower the cyt c reduction potential by hundreds of millivolts.13 In this way, PGE appears to provide a good mimic of the interaction of cyts c with biological membranes, and thus PFV provides insight into the dynamic character of cyt c physiology.

Supplementary Material

Complete experimental protocols, voltammograms showing the bulk-phase response of HH cyt c, the impact of ionic strength, exogenous ligand and pH dependencies.

Acknowledgments

SJE and TY acknowledge the support of the National Science Foundation (CAREER-MCB0546323); KLB thanks the National Institutes of Health (GM63170).

References

- 1.(a) Armstrong FA, Heering HA, Hirst J. Chem Soc Rev. 1997;26:169–179. [Google Scholar]; (b) Armstrong FA, Wilson GS. Electrochim Acta. 2000;45:2623–2645. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Jeuken LJC, van Vliet P, Verbeet MP, Camba R, McEvoy JP, Armstrong FA, Canters GW. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:12186–112194. [Google Scholar]; (b) Davis JJ, Bruce D, Canters GW, Crozier J, Hill HA. Chem Comm. 2003;7:576–577. doi: 10.1039/b211246a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Foord JS, McEvoy JP. Electrochim Acta. 2005;50:2933–2941. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Ye T, Kaur R, Wen X, Bren KL, Elliott SJ. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:8999–9006. doi: 10.1021/ic051003l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Michel LV, Ye T, Bowman SEJ, Levin BD, Hahn MA, Russell BS, Elliott SJ, Bren KL. Biochemistry. 2007;46:11753–11760. doi: 10.1021/bi701177j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Worrall JAR, Schlarb-Ridley BG, Reda T, Marcaida MJ, Moorlen RJ, Wastl J, Hirst J, Bendall DS, Luisi BF, Howe CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9468–9475. doi: 10.1021/ja072346g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schejter A, George P. Biochemistry. 1964;3:1045–1049. doi: 10.1021/bi00896a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamamoto Y, Terui N, Tachiiri N, Minakawa K, Matsuo H, Kameda T, Hasegawa J, Sambongi Y, Uchiyama S, Kobayashi Y, Igarashi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:11574–11575. doi: 10.1021/ja025597s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armstrong FA, Bond AM, Hill HAO, Oliver BN, Psalti ISM. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:9185–9189. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Elove GA, Bhuyan AK, Roder H. Biochemistry. 1992;33:6925–6935. doi: 10.1021/bi00188a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tezcan FA, Winkler JR, Gray HB. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:13383–13388. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barker PD, Mauk AG. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:3619–3624. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosell FI, Ferrer JC, Mauk AG. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:11234–11245. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson MT, Greenwood MT. Cytochrome c: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 1996:611–634. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gianni S, Travaglini-Allocateli C, Cutruzzolla F, Brunori M, Shastry MCR, Roder H. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:1145–1152. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00689-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basova LV, Kurnikov IV, Wang L, Ritov VB, Belikova NA, Vlasova II, Pacheco AA, Winnica DE, Peterson J, Bayir H, Waldeck DH, Kagan VE. Biochemistry. 2007;46:3423–3434. doi: 10.1021/bi061854k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Complete experimental protocols, voltammograms showing the bulk-phase response of HH cyt c, the impact of ionic strength, exogenous ligand and pH dependencies.