Abstract

This study examined the relationship between paternal alcoholism and toddler behavior problems from 18 to 36 months of age, as well as the potential moderating effects of 12-month infant–mother attachment security on this relationship. Children with alcoholic fathers had higher levels of internalizing and externalizing behavior than children of nonalcoholic fathers. Simple effects testing of an interaction effect of child age, group, and attachment security with mothers on externalizing behavior suggested that at 24 and 36 months of age mother–infant attachment security moderated the relationship between alcohol group status and externalizing behavior. Namely, within the alcohol group, those children with secure relationships with their mothers had significantly lower externalizing than insecure children of alcoholics. A similar pattern was noted for internalizing behavior at 36 months of age. Implications for intervention are discussed.

The toddler and preschool years are a time of rapid child development. From the ages of 2 to 3 years children begin to develop inhibitory control abilities that are reflective of their temperaments and parental socialization (Emde, Biringen, Clyman, & Oppenheim, 1991; Kopp, 1982; Rothbart, 1989). There is an increasing shift from parental control to child self-control. Developmentally, it is a time for increasing autonomy and often willfulness on the part of the child. It is during these “terrible twos” that parents often begin to identify behavior problems in their children. Researchers have found that normative increases in externalizing behavior can be expected in the toddler years and then decreases from 3 to 4 years of age (Cummings, Iannotti, & Zahn-Waxler, 1989; Nagin & Tremblay, 1999; Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby, & Nagin, 2003). Although some of these behaviors are developmentally appropriate, others can be viewed as the precursors to later maladaptive behavior. In fact, as early as preschool, moderate to severe behavior problems have been shown to be resistant to change and predictive of later dysfunction (Campbell, 1995). Such early behavior problems have been shown to negatively affect peer relations, a child’s developing sense of self, academic and family functioning, and to have long-lasting effects on the child (Campbell, 1990, 1995). Children of alcoholics may be particularly vulnerable to such behavioral difficulties.

It is well established that children of alcoholics are at both biological and environmental risk for a myriad of social, emotional, and behavioral problems (e.g., Carbonneau et al., 1998; Clark et al., 1997; Johnson, Leonard, & Jacob, 1989; Leonard et al., 2000; Poon, Ellis, Fitzgerald, & Zucker, 2000). Whereas most of the literature focuses on older children of alcoholics, who are prone to substance abuse and antisocial behavior, recent research has called for an increased focus on the problems of early childhood. The few studies that have done so have found preschool age children of alcoholics to be at risk for temperamental difficulties and externalizing behavior problems (Puttler, Zucker, Fitzgerald, & Bingham, 1998). In addition, children with alcoholic fathers have been found to exhibit higher internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, negative emotionality, and noncompliance (boys only) as early as 18 months of age (Edwards, Eiden, & Leonard, in press; Edwards, Leonard, & Eiden, 2001; Eiden, Edwards, & Leonard, 2002; Eiden, Leonard, & Morrisey, 2001). However, although children raised in alcoholic families are at risk for developmental maladaptation, there is a considerable degree of heterogeneity in psychosocial consequences, suggesting the potential for resilience (Johnson, Sher, & Rolf, 1991). Resilience has been defined as a “dynamic process wherein individuals display positive adaptation despite experiences of significant adversity or trauma” (Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000, p. 858). In early childhood, one area of positive adaptation is the development of a secure attachment relationship with the primary caregiver. Thus, in considering such resilience in the toddler years, the mother–child attachment relationship is a crucial area of focus.

The attachment relationship that the child forms with his or her parents in the first year of life serves as a foundation for exploration and developing mastery as a toddler (Edwards, 1996; Jacobwitz, Morgan, Kretchmar, & Morgan, 1992). Secure attachment is built from a caregiving environment characterized by parental responsiveness, sensitivity, and consistency (Ainsworth & Wittig, 1969). Secure children develop a sense that the world is predictable and that their needs will be met and their anxieties soothed. Secure relationships form a mutually cooperative system between parent and child, and it is this positive reciprocal orientation that opens the child to the positive socializing influence of the parent (Maccoby, 1984; Maccoby & Martin, 1983) and to more successful parental discipline as the child ages (Grusec & Goodnow, 1994). The endurance of this positive relationship then promotes optimal psychosocial development within the context of the family system. Conversely, children with insecure attachments have been found to be at an increased risk for poor peer relationships, behavior problems, and emotional difficulties (e.g., DeVito & Hopkins, 2001; Easterbrooks, Biesecker, & Lyons-Ruth, 2000; Greenberg, Speltz, DeKlyen, & Jones, 2001; Sroufe, Carlson, & Shulman, 1993).

Children of alcoholics, theorized to be prone to behavioral dysregulation, are particularly at risk for the development of such behavior problems (Tarter, 1988). However, perhaps within the context of a secure mother–infant attachment relationship, these outcomes can be avoided. In a study of resilience in children of alcoholics, Werner (1986) found that the quality of caretaking that children received in the first years of life was associated with child outcome at age 18 in alcoholic families. Children who received more attention from caregivers in infancy, had no prolonged separations from caregivers, and whose mothers had no additional births during the first 2 years of life (all variables associated with attachment) had fewer coping problems as adolescents. Results from other studies examining parenting in alcoholic families as a possible protective factor have been mixed (Curran & Chassin, 1996; Hussong & Chassin, 1997). However, these studies examined such processes in older children, an age at which peers may be a more salient socializing force than parents. No study to date has examined parenting and resilience among children of alcoholic families as they grow from toddlerhood into the preschool years. In considering the issue of resilience among children of alcoholics, the development of a secure attachment with the nonalcoholic parent may itself be reflective of resilience. That is, children of alcoholic fathers who have successfully negotiated this salient developmental task of infancy may be viewed as being resilient in the face of multiple, nested risk factors characteristic of alcoholic families, such as increased marital conflict, parental psychopathology, and difficult child temperament. On the other hand, a secure attachment relationship with the nonalcoholic parent may also be viewed as a protective factor that may modify the negative effects of being in an alcoholic family. “A protective factor is one that modifies the effect of risk in a positive direction” (Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000, p. 858). Although it may be argued that a secure attachment relationship with a primary caregiver may have positive effects for all children, the modifying effect of a protective factor may only be apparent in the presence of adversity or risk (Rutter, 1987; Werner, 1986). In other words, children with secure attachments with mothers may display lower levels of behavior problems compared to children with insecure attachments with mothers. However, in the context of a high-risk design, both children experiencing low family risk and children experiencing high family risk but having a salient protective factor may display similar low levels of behavior problems. The main effect of being a child of an alcoholic father may thus be modified such that the association between fathers’ alcoholism and child behavior problems may vary as a function of child’s attachment security with the nonalcoholic parent.

In the current study, we examined attachment with mothers at 12 months of age as a potential protective factor in the development of behavior problems across time from 18 to 36 months of age in children of alcoholic fathers. We hypothesized that (a) children of alcoholic fathers will exhibit higher externalizing and internalizing behavior problems that increase with age compared to children of nonalcoholic fathers, and (b) the presence of a secure attachment relationship with mothers during infancy will moderate the effect of fathers’ alcoholism on toddler behavior problems. More specifically, we hypothesized that within the alcoholic group, children with a secure infant–mother attachment pattern would have lower levels of behavior problems compared to children with an insecure infant–mother attachment pattern. Given the expectation that children in the nonalcoholic group will have generally low levels of behavior problems, we did not expect evidence of a protective effect or a significant difference between children with secure versus insecure attachments within this group. With the expected emergence of behavior problems in the toddler to preschool ages, the focus of this study was on mother reported child behavior problems at 18, 24, and 36 months of age.

Method

Participants

The participants were 176 families with 12-month-old infants (89 girls, 87 boys)who volunteered for an ongoing longitudinal study of parenting and infant development and completed attachment assessments at 12 months of infant age and had complete data at all three time periods. Families were classified as being in one of two major groups: the nonalcoholic group (n = 94), and the father alcoholic group (n = 82). The original group consisted of 191 families, 4 of these families did not participate in the 24-month assessment and 11 additional families did not participate in the 36-month assessment and thus were dropped from analyses. The majority of the mothers in the study were Caucasian (94%), 4% were African American, and 2% were Hispanic or Native American. Similarly, the majority of fathers were Caucasian (90%), 7% were African American, and 2% were Hispanic or Native American. The majority of the mothers had a post high school education such as an associate or vocational degree (31%) or were college graduates (27%). There were very few who were not high school graduates (2%). The educational level of the fathers was similar, with 33% receiving a college degree and 18% receiving some post high school education. Only 5% had not graduated from high school. All of the mothers were residing with the father of the infant in the study. Most of the parents were married to each other (88%), about 11% had never been married, and 1% had previously been married. Mothers’ ages ranged from 19 to 41 (M = 30.7, SD = 4.46) and fathers’ ages ranged from 21 to 58 (M = 32.95, SD = 5.94). About 62% of the mothers and 92% of the fathers were working outside the home at the time of the 12-month assessment, with very similar percentages working at the 18 month assessment (66% of mothers, 92% of fathers).

Procedures

The names and addresses of these families were obtained from New York State birth records for Erie County. These birth records were preselected to exclude families with premature (gestational age ≤ 35 weeks), or low birth weight infants (birth weight < 2500 g), maternal age of less than 19 or greater than 40 at the time of the infant’s birth, plural births (e.g., twins), and infants with congenital anomalies, palsies, or drug withdrawal symptoms. Introductory letters were sent to a large number of families (n = 13,657) who met the above-mentioned basic eligibility criteria. Each letter included a form that all families were asked to complete and return. Approximately 25% of these families completed the form and, of these, 3,422 replies (96%) indicated an interest in the study. Respondents were compared to the overall population with respect to information collected on the birth records. These analyses indicated a slight tendency for infants of responders to have higher birth weight (M = 3511 vs. 3473 g). Responders were also more likely to be Caucasian (88% of total births vs. 91% of responders), have higher educational levels, and have a female infant. These differences were significant given the very large sample size, even though the effect sizes were small (effect size < .22 in all analyses).

Parents who indicated an interest in the study were screened by telephone with regard to sociodemographics and further eligibility criteria. Initial inclusion criteria consisted of both parents cohabiting since the infants’ birth until the time of recruitment, the target infant being the youngest child in the family, mother was not pregnant at time of recruitment, no mother–infant separations for over a week, parents were the primary caregivers, and the infant did not have any major medical problems. These criteria were important to control because each of these has the potential to markedly alter parent–infant interactions. Additional inclusion criteria were utilized to minimize the possibility that any observed infant behaviors could be the result of prenatal exposure to drugs or heavy alcohol use. These additional criteria were that there could be no maternal drug use during pregnancy or in the past year except for mild marijuana use (no more than twice during pregnancy), mothers average daily ethanol consumption was 0.50 oz. or less and she did not engage in binge drinking (five or more drinks per occasion) during pregnancy. During the phone screen, mothers were administered the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) for alcoholism with regard to their partners’ drinking (Andreason, Rice, Endicott, Reich, & Coryell, 1986) and mother and fathers were screened with regard to their own alcohol use, problems, and treatment.

Families meeting the basic inclusion criteria were assigned to one of two groups (nonalcoholic, father alcoholic) on the basis of parental phone screens and questionnaires administered prior to the first visit. Mothers in both groups scored below 3 on an alcohol screening measure (Chan, Welte, & Russell, 1993), were not heavy drinking (average daily ethanol consumption < 1.00 oz.), did not acknowledge binge drinking, and did not meet DSM-IV criteria for abuse or dependence. Fathers in the nonalcoholic group did not meet RDC criteria for alcoholism according to maternal report, did not acknowledge having a problem with alcohol, had never been in treatment, and had alcohol related problems in fewer than two areas in the past year and three areas in his lifetime according to responses on a screening interview based on the University of Michigan Composite Diagnostic Index (UM-CIDI; Anthony, Warner, & Kessler, 1994). Alcohol problem areas assessed include alcohol interfering with the marital relationship or parenting, causing legal problems or hazardous behavior, developing a tolerance to alcohol, or experiencing withdrawal symptoms from alcohol. A family could be classified in the father alcoholic group by meeting any one of the following three criteria: (a) the father met RDC criteria for alcoholism according to maternal report; (b) he acknowledged having a problem with alcohol or having been in treatment for alcoholism, was currently drinking, and had at least one alcohol-related problem in the past year; or (c) he indicated having alcohol-related problems in three or more areas in the past year or met DSM-IV criteria for abuse or dependence in the past year. Because we had a large pool of families potentially eligible for the nonalcoholic group, alcoholic and nonalcoholic families were matched on race/ethnicity, maternal education, child gender, parity, and marital status.

To date, families have been asked to visit the Institute at five different infant ages (12, 18, 24, and 36 months and upon entry into kindergarten) with three visits at each age. Two weeks before each visit, parents were sent a packet of questionnaires, one for each parent. Both parents were asked to complete the questionnaires independently and return them in sealed envelopes at the first visit. Extensive observational assessments with both parents were conducted at each age. Coding of observational data from subsequent visits is ongoing as are assessments at 5–6 years of child age. This paper focuses on the 12-month mother–infant attachment assessment, which has been completed and coded for the entire sample, and 18-, 24-, and 36-month questionnaire assessments.

Measures

Parental alcohol use

Although parental alcohol abuse and dependence problems were partially assessed from the screening interview, self-report versions with more detailed questions were used to enhance the alcohol data and check for consistent reporting. A self-report instrument based on the UM-CIDI (Anthony et al., 1994; Kessler et al., 1996) interview was used to assess alcohol abuse and dependence. Several questions of the instrument were reworded to inquire as to “how many times” a problem had been experienced, as opposed to whether it happened “very often.” For questions reworded in this way, subjects had to endorse three or more problems in the past year for the item to be counted in the diagnosis. DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence diagnoses for current alcohol problems (in the past year) were used to assign final diagnostic group status.

Child behavior

Behavior problems at 18, 24, and 36 months were assessed with the 2-to 3-year-old version of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1992). The CBCL is a widely used measure of children’s behavioral/emotional problems. It consists of 100 items on a 3-point response scale ranging from not true to very true, with some open-ended items designed to elicit detailed information about a particular problem behavior. The behavior ratings yield two broad-band dimensions of internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Higher scores indicate more toddler behavior problems. Although the CBCL had not yet been extended to 18-month-olds at the time of the assessments, it had demonstrated validity for 24-month-olds. Since then, an 18-month version has been developed with no significant differences from the 24-month version (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000). The CBCL has well-established psychometric properties and allows for identification of internalizing and externalizing problem behavior syndromes (Achenbach, 1992). In the present study, internal consistencies were .80 and .84 for the internalizing and externalizing sub-scales. Because of concerns about the accuracy of alcoholic fathers’ reports of their children, maternal reports of child behavior were used for all analyses.

Mother–infant attachment

The Ainsworth Strange Situation paradigm (Ainsworth & Wittig, 1969), a 21-min videotaped, structured laboratory separation–reunion procedure was used to examine mother–infant attachment at 12 months of infant age. The procedure consists of seven 3-min episodes that occur in a fixed order and are designed to induce increasing levels of stress in the infant so as to activate the attachment system. In each episode, the infant’s behavior is rated along six dimensions using 7-point scales. The ratings are used to classify the infants into three major categories: secure, insecure-avoidant, and insecure-resistant. In addition to these three classifications, the coding scheme has been extended to include an additional pattern that is especially prevalent in high-risk infants, the disorganized (D) pattern (Main & Solomon, 1990). The D classification is considered to be an insecure pattern with behaviors representing a collapse of organized behavior in response to stress of separation, resulting from fear or apprehension in the parent’s presence.

The first author and two research assistants, who were blind to group status, were responsible for coding all the Strange Situations, with consultation on difficult to code tapes provided by the second author. The second author was originally trained in coding Strange Situations by Douglas Teti, with training on D coding provided by Dante Cicchetti, with follow-up training by Alan Sroufe and Elizabeth Carlson. The first author was trained by Alan Sroufe and Elizabeth Carlson, and both authors achieved reliability on the standard test offered through the University of Minnesota. Interrater reliability was established between the first author and each research assistant on 15% of the tapes (n = 24). Individual dyads used for reliability were selected randomly and included all four classifications. The mean interrater reliability using Pearson’s r was .76 on the Strange Situation rating scales and .81 for the Disorganization scale score. Interrater agreement on the four attachment classifications was 93%. Of the 94 mother–infant dyads from the nonalcoholic group who completed the Strange Situation, 70% were classified as secure, 9% were classified as avoidant, 15% as resistant, and 6% as disorganized. Of the 82 mother–infant dyads from the father alcoholic group who completed the Strange Situation, 64% were classified as secure, 13% were classified as avoidant, 13% as resistant, and 10% as disorganized. Two mother–infant attachment groups: secure (B)and insecure (A, C, and D combined)were used for all further analyses.

Results

Demographic differences

Analyses of variance were used to examine alcohol group differences on variables including family income, parental education, parental age, and the number of hours each parent worked outside the home when the infant was 12 months of age. These analyses yielded no group differences on any of the demographic variables other than fathers’ education, F (1, 204) = 13.2, p < .001. Alcoholic fathers were less educated (M = 13.29, SD = 1.85) compared to those in the nonalcoholic group (M= 14.43, SD= 2.62). However, fathers’ education was not associated with child behavior problems or mother–infant attachment behavior. Because of the possibility that fathers’educational level was a consequence of the developmental precursors of alcoholism and it was not related to dependent variables, we did not utilize it as a covariate in the group comparisons.

Age and alcohol group differences in behavior problems

The next set of analyses tested our first hypothesis by examining age and group differences in maternal reports of child behavior problems. Means, standard deviations, and the percentage of children perceived to have clinically significant behavior problems in families with alcoholic and nonalcoholic fathers are shown in Table 1. Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine changes in child behavior problems over time. To examine possible gender differences in child behavior problems, child age was the within-subjects factor and alcohol group status and child gender were the between-subjects factors. Internalizing behavior problems were the dependent variables in the first ANOVA and externalizing behavior problems were the dependent variables in the second. Univariate effects for all analyses are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

T-score means, standard deviations, and percentage of children in the clinical range for internalizing and externalizing behavior in families with alcoholic and nonalcoholic fathers

| Alcoholic |

Nonalcoholic |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | In Clinical Range (%) | M | SD | In Clinical Range (%) | |

| Internalizing behavior | ||||||

| 18 Months | 47.02 | 9.29 | 1 | 44.62 | 8.63 | 1 |

| 24 Months | 47.91 | 8.52 | 2 | 46.80 | 8.26 | 2 |

| 36 Months | 50.20a | 8.82 | 10 | 47.11b | 8.35 | 2 |

| Externalizing behavior | ||||||

| 18 Months | 49.60 | 8.80 | 4 | 47.58 | 8.11 | 1 |

| 24 Months | 51.04a | 9.21 | 6 | 48.35b | 7.91 | 1 |

| 36 Months | 50.46a | 8.57 | 5 | 48.01b | 9.05 | 0 |

Note: Means with different subscripts are significantly different (p < .05) within age. Standardized t scores are reported for ease of clinical interpretation, although raw scores were used in the analyses. CBCL internalizing and externalizing t scores higher than 63 are considered to be in the clinical range.

Table 2.

Univariate effects for mother and father reports of child behavior problems

| Mother Externalizing |

Mother Internalizing |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | F | p | F | p | |

| Age × Group × Gender ANOVA | |||||

| Age | 2, 176 | 3.30 | <.05 | 11.44 | <.001 |

| Group | 1, 176 | 4.92 | <.05 | 4.21 | <.05 |

| Gender | 1, 176 | 1.95 | .16 | 0.40 | .53 |

| Age × Group × Gender | 2, 176 | 0.34 | .71 | 0.12 | .88 |

| Age × Group × Security ANOVA | |||||

| Age | 2, 176 | 2.27 | .11 | 11.52 | <.001 |

| Group | 1, 176 | 5.10 | <.05 | 4.68 | <.05 |

| Security | 1, 176 | 4.91 | <.05 | 8.25 | <.01 |

| Age × Group × Security | 2, 176 | 4.14 | <.05 | 2.40 | .09 |

A main effect of age was found for mothers’ reports of externalizing and internalizing behavior as hypothesized. Internalizing behavior was perceived to increase over time, while externalizing behavior increased from 18 to 24 months of child age and then did not change significantly from 24 to 36 months of age. In addition, as expected, a main effect of group was found for mothers’ reports of child externalizing and internalizing behavior, such that children with alcoholic fathers were perceived to have more behavior problems than children of non alcoholic parents. No gender or interaction effects were found.

Moderating effects of attachment on behavior problems

Second, we hypothesized that mother–infant attachment security would moderate the relationship between fathers’ alcoholism and child behavior problems, such that among children of alcoholic fathers, those with insecure mother–infant attachments would have higher problem behavior scores that increase with age than securely attached children of alcoholics. Thus, we hypothesized the presence of an interaction of child age, alcohol group status, and mother–infant attachment security (secure vs. insecure) on behavior problems.

To examine whether infant attachment security with mothers moderated the association between fathers’ alcoholism and child behavior problems, a repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted with first internalizing and then externalizing behavior problems as the dependent variables, child age as the within-subjects factor, and alcohol group status and mother–infant attachment security as the between-subjects factors.

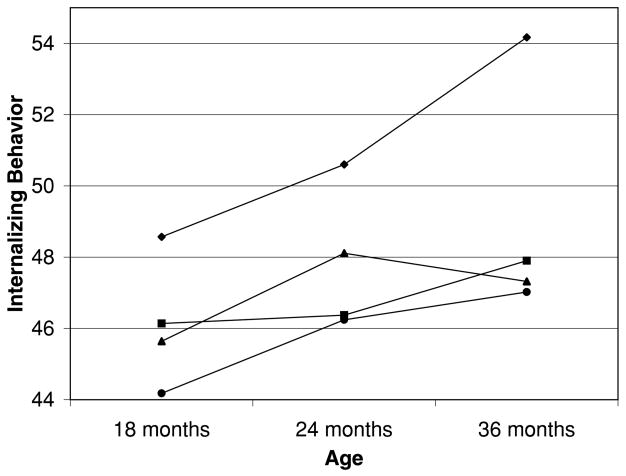

Internalizing behavior

Again, significant main effects of age and group were found for mothers’ reports of child internalizing behavior, such that internalizing behavior increased over time and children in the father alcoholic group were perceived to have more problems than children in the nonalcoholic group based on simple effects analyses. A significant mother–infant attachment security main effect was also found, such that internalizing behavior was reported to be higher in children with an insecure mother–infant attachment relationship than in children with secure attachments. The age by group by mother–infant attachment security interaction was only marginally significant, F (2, 176)= 2.40, p = .095, demonstrating a pattern similar to that found for externalizing behavior described below (see Figures 1 and 2). Notably, there was a sharp increase in mother reported internalizing behavior among 36-month-old children of alcoholics with insecure mother–infant attachments. Because of this increase, we examined internalizing behavior separately at 36 months of age using ANOVA. This analysis indicated that there was a significant group by mother–infant attachment security interaction at 36 months, F (2, 176) = 4.34, p < .05. Mothers of insecurely attached infants reported significantly higher child internalizing problems than mothers in the three other groups (whose scores did not differ significantly from one another) at 36 months of child age. This suggests a protective effect of 12-month mother–infant attachment security at 36 months of age in the father alcoholic group (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The interaction of age, group, and mother–infant attachment security on internalizing behavior t scores; (◆) insecure, alcoholic group; (■) secure, alcoholic group; (▲) insecure, nonalcoholic group; (●) secure, nonalcoholic group.

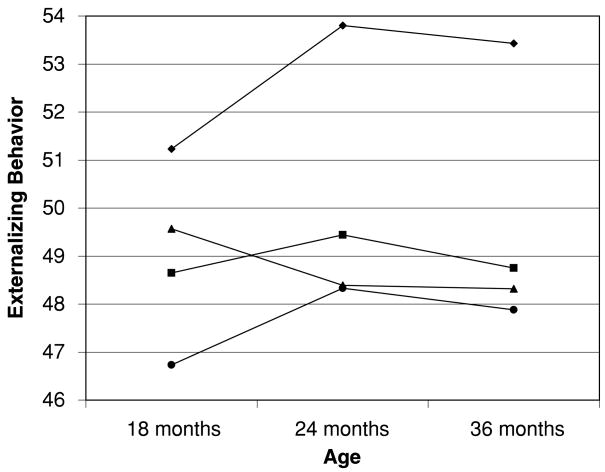

Figure 2.

The interaction of age, group, and mother–infant attachment security on externalizing behavior t scores; (◆) insecure, alcoholic group; (■) secure, alcoholic group; (▲) insecure, nonalcoholic group; (●) secure, nonalcoholic group.

Externalizing behavior

Finally, we tested our hypothesis that among children of alcoholic fathers, security of attachment with mothers would serve as a protective factor against the development of externalizing behavior problems. Results from this ANOVA yielded a significant Age × Group × Mother–Infant attachment security interaction effect for child externalizing behavior problems as reported by mothers.1 Analyses of simple effects indicated that insecure children of alcoholic fathers had significantly higher levels of externalizing behavior than secure children from nonalcoholic families at 18 months of infant age and significantly higher levels of externalizing behavior than all other groups at 24 and 36 months of child age. As hypothesized, a secure mother–infant attachment relationship seemed to serve as a protective factor against the development of externalizing behavior problems among children of alcoholic fathers. Children of alcoholic fathers who had a secure attachment relationship with their mothers had significantly lower levels of externalizing behavior problems than children of alcoholic fathers with insecure mother–infant attachments. Children with secure attachments with mothers and children with nonalcoholic fathers (regardless of attachment security)were not significantly different from each other (see Figure 2). Insecure children of alcoholic fathers and secure children of nonalcoholic fathers had a significant increase in externalizing behavior from 18 to 24 months of age. Again, there were no significant changes in externalizing behavior from 24 to 36 months in any of the groups, but the overall level of externalizing behavior was quite different.

Discussion

As expected, and consistent with previous literature, young children with alcoholic fathers had higher levels of internalizing and externalizing behavior than children of nonalcoholic fathers. In a sample slightly older than our own, Puttler et al. (1998) found that 3- to 8-year-old children of alcoholic fathers had higher levels of behavior problems than children from nonalcoholic families. Similar findings have been found for both preadolescent and adolescent children of alcoholics (Chassin, Rogosch, & Barrera, 1991; Jacob & Leonard, 1986), suggesting the presence of a possible behavior problem trajectory for these children. Thus, children with higher levels of externalizing and internalizing behavior problems at 18 months of age in the present study may be at increased risk for later, more significant psychosocial problems by school age and adolescence. Children with clinically significant levels of externalizing behavior at an early age may be particularly at risk. Such children are considered “early starters” (Patterson, Capaldi, & Bank, 1991), the name given to a developmental pattern of externalizing behavior with early onset and high continuity throughout childhood. Although these children generally start with milder forms of aggressive and noncompliant behavior, their conduct problems tend to become more serious over time (McMahon, 1994), and may lead to adolescent antisocial behavior. Few studies have specifically examined the development of internalizing behavior problems among children of alcoholics. The ability to track these children as they age from 18 months on is a strength of the current project and will add to our understanding of behavior problems in families with alcoholic fathers.

We hypothesized that infant attachment security with mothers would act as a protective factor against the risk associated with fathers’ alcoholism. Results indicate that among alcoholic families, those with a secure infant–mother attachment relationship at 12 months of age had infants with fewer externalizing behavior problems at 24 and 36 months of age than those with insecure infant–mother attachments. A similar pattern was found for internalizing behavior problems at 36 months of age. Thus, mother–infant attachment appears to serve as a protective factor in alcoholic families, moderating the relationship between paternal alcoholism and child behavior. Few previous studies have examined potential protective factors among children of alcoholics, making comparisons with previous studies difficult. However, our results are generally supportive of Werner’s (1986) study reporting that the association between parental alcoholism and child outcome in adolescence was moderated by the quality of caretaking that children received in the first years of life. Results were also reflective of El-Sheikh and Buckhalt’s (2003) recent study of child adjustment in alcoholic families. They, too, found that mother–child attachment acted as a protective factor in alcoholic families. As in the present study, this effect was only apparent in the high-risk (alcoholic family) group, wherein mother–child attachment moderated the relationship between problem drinking and child social and behavioral functioning of 6- to 12-year-olds.

Other studies of high-risk families have also identified secure mother–infant attachment as a protective factor (Morisset, Barnard, Greenberg, Booth, & Spieker, 1990; Rutter, 1987); however, the mechanism by which mother–infant attachment security enables such resilience is unclear. The link between mother–infant attachment security and behavior problems has been hypothesized to occur via developing child self-regulation. In very young children, behavior problems are typically the result of deficits in self-control (Campbell, 2002). In toddlers, self-regulation is an evolving function of both child and parental influences formed in the context of the mother–infant attachment relationship. In secure relationships, it is theorized that negative emotions are soothed and managed by supportive caregivers’ guidance and nurturance and do not become overwhelming to the children (Thompson, 1994). Thus, gradually children learn to regulate their own emotions through this example. Children of unresponsive or inconsistent parents, however, may learn to under-or overregulate their emotions, possibly leading to later internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (Sroufe, 1988). Further, Davies and Cummings’ (1994) suggest that children experience less anxiety and frustration in the context of an emotionally secure family environment and are thus less prone to disruptive behavior. Maternal responsiveness and mother–infant mutual positive affect, qualities associated with attachment security, have also been found to be associated with increased toddler empathy and compliance (Kochanska, Forman, & Coy, 1999), as well as conscience development in the early school years (Kochanska & Murray, 2000). Thus, among infant children of alcoholic fathers, those with secure attachment relationships with their mothers may have increased behavioral regulation capabilities placing them at lower risk for the development of maladaptive behavior patterns.

However, it is important to note that such individual risk factors are nested within a high-risk environment (Loukas, Zucker, Fitzgerald, & Krull, 2003; Zucker, Wong, Puttler, & Fitzgerald, 2002). Alcoholic families have been characterized as being high in marital conflict, antisocial behavior, and depression, all of which have been shown to have a deleterious effect on parent–child relations and may in turn have an effect on the development of child behavior problems (Edwards et al., 2001; Eiden, Chavez, & Leonard, 1999; Eiden et al., 2002; Loukas et al., 2003; Puttler et al., 1998). However, examining additional mediators and moderators of the relationship between paternal alcoholism and child behavior problems was outside the scope of the current paper.

There are some limitations to the present study. This study utilized self-reports of paternal alcohol problems and maternal reports of child behavior problems, which could be considered a study liability. However, it should be noted that the self-report information on alcohol problems was corroborated by the spouse in the initial screening interview. Further, it has been found that parent report on childhood behavior is predictive of later objective outcomes in children and thus may be viewed as a valid means of assessment (Stanger, Mac-Donald, McConaughy, & Achenbach, 1996). In addition, although deriving our sample from birth records has important advantages over newspaper or clinic-based samples, it should be noted that there are also limitations. The response rate to our open letter of recruitment was slightly above 25%. This raises the possibility that respondents to our recruitment may have been a biased group. Further, it should be noted that as a community sample, levels of average daily ethanol consumption by parents in this study (range = 0.14–5.73, M = 1.43 for alcoholic group) were significantly lower than ethanol consumption reported in treated and untreated clinical samples (Babor, Kranzler, & Lauerman, 1989, M = 9.94; Jacob & Krahn, 1987, M = 6.47; York & Welte, 1994, M = 11.65). Further, child internalizing and externalizing behavior in this study were also identified at largely subclinical levels. As a consequence, we would view our assessment of the association between fathers’ alcoholism and child behavior problems to be conservative.

The results of the present study underscore the increased prevalence of behavior problems in children of alcoholics compared to a matched group of children of nonalcoholics and identify secure mother–infant attachment as a protective factor for toddlers in alcoholic families. These findings are encouraging in terms of potential intervention efforts with these children. Prevention programs aimed at improving the quality of the relationship with the nonalcoholic parent may be effective at protecting the child against socioemotional maladaptation resulting from fathers’ alcoholism (see Erickson & Egeland, 2004). Interventions for this population may be particularly crucial as deficits in behavioral regulation, reflective of a genetic liability, are often present in children of alcoholics (Tarter, 1988; Tarter, Kabene, Escallier, Laird, & Jacob, 1990). Such dysregulation may negatively impact the children’s ease in developing secure parent–child attachments (Kochanska, 1998). Many studies have successfully demonstrated an ability to improve parenting quality and child behavior in other high-risk groups (Van den Boom, 1994, 1995; Webster-Stratton, 1994). By using these techniques with children of alcoholics, child resilience can be maximized. Further, by targeting at-risk toddlers before the emergence of significant, clinical problems, intervention is likely to be more cost effective, briefer, less intensive, and more likely to succeed than interventions conducted once disturbances crystallize in children and problems become more resistant to change (Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the parents and infants who participated in this study and the research staff who were responsible for conducting numerous assessments with these families. This study was made possible by grants from NIAAA(1RO1 AA-10042-01A1) and NIDA (1K21DA00231-01A1).

Footnotes

It should be noted that, when this interaction was examined with fathers’ ratings of children’s externalizing behavior, it was also significant and showed a very similar pattern of scores, suggesting the result is more than a maternal perceptual bias.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/2–3 and 1992 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for ASEBA Preschool Forms and Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Wittig BA. Attachment and exploratory behavior of one year olds in a strange situation. In: Foss BM, editor. Determinants of infant behavior. Vol. 4. London: Methuen; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Andreason NC, Rice J, Endicott J, Reich T, Coryell W. The family history approach to diagnosis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:421–429. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800050019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony JC, Warner LA, Kessler RC. Comparative epidemiology of dependence on tobacco, alcohol, controlled substances, and inhalants: Basic findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1994;2:244–268. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Kranzler HR, Lauerman RJ. Early detection of harmful alcohol consumption: Comparison of clinical, laboratory, and self-report screening procedures. Addictive Behavior. 1989;14:139–157. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB. Behavior problems in preschool children: Clinical and developmental issues. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB. Behavior problems in preschool children: A review of recent research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1995;36:113–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB. Behavior problems in preschool children: Clinical and developmental issues. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonneau R, Tremblay RE, Vitaro F, Dobkin PL, Saucier JF, Pihl RO. Paternal alcoholism, paternal absence and the development of problem behaviors in boys from age six to twelve years. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:387–398. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan AWK, Welte JW, Russell M. Screening for heavy drinking/alcoholism by the TWEAK test. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1993;17:463. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Rogosch G, Barrera M. Substance use and symptomatology among adolescent children of alcoholics. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:449–463. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Moss HB, Kirisci L, Mezzich AC, Miles R, Ott P. Psychopathology in pre-adolescent sons of fathers with substance use disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:495–502. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT, Campbell SB. Developmental psychopathology and family process. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Iannotti RJ, Zahn-Waxler C. Aggression between peers in early childhood: Individual continuity and developmental change. Child Development. 1989;60:887–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb03521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Chassin L. Longitudinal study of parenting as a protective factor for children of alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57:305–313. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: A emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVito C, Hopkins J. Attachment, parenting, and marital dissatisfaction as predictors of disruptive behavior in preschoolers. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:215–231. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrooks MA, Biesecker G, Lyons-Ruth K. Infancy predictors of emotional availability in middle childhood: The roles of attachment security and maternal depressive symptomatology. Attachment and Human Development. 2000;2:170–187. doi: 10.1080/14616730050085545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards CP. Parenting toddlers. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol. 1. Children and parenting. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards EP, Eiden RD, Leonard KE. Impact of fathers’ alcoholism and associated risk factors on parent–infant attachment stability from 12 to 18 months. Journal of Infant Mental Health. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20027. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards EP, Leonard KE, Eiden RD. Temperament and behavioral problems among infants in alcoholic families. Journal of Infant Mental Health. 2001;22:374–392. doi: 10.1002/imhj.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Chavez F, Leonard KE. Parent–infant interactions in alcoholic and control families. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:745–762. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Edwards EP, Leonard KE. Mother–infant and father–infant attachment among alcoholic families. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:253–378. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402002043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Leonard KE, Morrisey S. Paternal alcoholism and toddler noncompliance. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:1621–1633. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Buckhalt JA. Parental problem drinking and children’s adjustment: Attachment and family functioning as moderators and mediators of risk. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:510–520. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emde RN, Biringen Z, Clyman RB, Oppenheim D. The moral self of infancy: Affective core and procedural knowledge. Developmental Review. 1991;11:251–270. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson MF, Egeland B. Linking theory and research to practice: The Minnesota Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children and the STEEP™program. Clinical Psychologist. 2004;8:5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Speltz ML, DeKlyen M, Jones K. Correlates of clinic referral for early conduct problems: Variable- and person-oriented approaches. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:255–276. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusec JE, Goodnow JJ. Summing up and looking to the future. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Chassin L. Substance use initiation among adolescent children of alcoholics: Testing protective factors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:272–279. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Krahn GL. The classification of behavioral observation codes in studies of family interaction. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1987;49:677–687. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Leonard KE. Psychosocial functioning in children of alcoholic fathers, depressed fathers, and control fathers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1986;47:373–380. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1986.47.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobwitz D, Morgan E, Kretchmar M, Morgan Y. The transmission of mother–child boundary disturbances across three generations. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;3:513–527. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S, Leonard KE, Jacob T. Drinking, drinking styles, and drug use in children of alcoholics, depressives, and controls. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:427–431. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Sher KJ, Rolf JE. Models of vulnerability to psychopathology in children of alcoholics: An overview. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1991;15:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Edlund MJ, Frank RG, Leaf PJ. The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: Implications for prevention and service utilization. Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66:17–31. doi: 10.1037/h0080151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Mother–child relationship, child fearfulness, and emerging attachment: A short-term longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:480–490. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Forman DR, Coy KC. Implications of the mother–child relationship in infancy socialization in the second year of life. Infant Behavior and Development. 1999;22:249–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray KT. Mother–child mutually responsive orientation and conscience development: From toddler to early school age. Child Development. 2000;71:417–431. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB. Antecedents of self-regulation: A developmental perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:199–214. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Eiden RD, Wong MM, Zucker RA, Puttler LI, Fitzgerald HE, et al. Developmental perspectives on risk and vulnerability in alcoholic families. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:238–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A, Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE, Krull JL. Developmental trajectories of disruptive behavior problems among sons of alcoholics: Effects of parent psychopathology, family conflict, and child undercontrol. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:119–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D. The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:857–885. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400004156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. Socialization and developmental change. Child Development. 1984;55:317–328. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby E, Martin J. Socialization in contexts of the family: Parent–child interaction. In: Hetherington EM, editor. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, Personality, and Social Development. 4. New York: Wiley; 1983. pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Solomon J. Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. In: Greenberg MT, Cicchetti D, editors. Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation series on mental health and development. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990. pp. 121–160. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon R. Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of externalizing problems in children: The role of longitudinal data. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:901–917. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.5.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisset CT, Barnard KE, Greenberg MT, Booth CL, Spieker SJ. Environmental influence on early language development: The context of social risk. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2:127–149. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS, Tremblay R. Trajectories of boys’ physical aggression, opposition, and hyperactivity on the path to physically violent and non-violent juvenile delinquency. Child Development. 1999;70:1181–1196. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Capaldi D, Bank L. An early starter model for predicting delinquency. In: Pepler DJ, Rubin KH, editors. The development and treatment of childhood aggression. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 139–168. [Google Scholar]

- Poon E, Ellis DA, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Intellectual, cognitive, and academic performance among sons of alcoholics during the early school years: Differences related to subtypes of familial alcoholism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:1020–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puttler LI, Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE, Bingham CR. Behavioral outcomes among children of alcoholics during the early and middle childhood years: Familial subtype variations. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:1962–1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK. Biological processes in temperament. In: Kohnstamm GA, Bates JA, Rothbart MK, editors. Temperament in childhood. New York: Wiley; 1989. pp. 77–110. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987;147:598–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby EM, Nagin DS. Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA. The role of infant attachment in development. In: Belsky J, Nezworski T, editors. Clinical Implications of attachment. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. pp. 18–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Carlson E, Shulman S. Individuals in relationships: Development from infancy through adolescence. In: Funder DC, Parke RD, editors. Studying lives through time: Personality and development. APA science volumes. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1993. pp. 315–342. [Google Scholar]

- Stanger C, MacDonald VV, McConaughy SH, Achenbach TM. Predictors of cross-informant syndromes among children and youths referred for mental health services. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1996;24:597–614. doi: 10.1007/BF01670102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE. Are there inherited behavioral traits that predispose to substance abuse? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:189–196. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Kabene M, Escallier EA, Laird SB, Jacob T. Temperament deviation and risk for alcoholism. Alcohol Clinical and Experimental Research. 1990;14:380–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1990.tb00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. In: Fox NA, editor. The development of emotion regulation: Biological and behavioral considerations. Vol. 59. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development; 1994. pp. 25–52. (2–3, Serial No. 240) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Boom DC. The influence of temperament and mothering on attachment and exploration: An experimental manipulation of sensitive responsiveness among lower-class mothers with irritable infants. Child Development. 1994;65:1798–1816. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Boom DC. Do first-year intervention effects endure? Follow-up during toddlerhood of a sample of Dutch irritable infants. Child Development. 1995;66:1798–1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. Advancing videotape parent training: A comparison study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:583–593. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.3.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner EE. Resilient offspring of alcoholics: A longitudinal study from birth to age 18. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1986;47:34–40. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1986.47.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York JL, Welte JW. Gender comparisons of alcohol consumption in alcoholic and nonalcoholic populations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:743–750. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Wong MM, Puttler LI, Fitzgerald HE. Resilience and vulnerability among sons of alcoholics: Relationship to developmental outcomes between early childhood and adolescence. In: Luthar S, editor. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 76–103. [Google Scholar]