Abstract

Background

Family risk analysis can provide an improved understanding of the association between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), attending to the comorbidity with conduct disorder (CD).

Methods

We compared rates of psychiatric disorders in relatives of 78 control probands without ODD and CD (Control, N=265), relatives of 10 control probands with ODD and without CD (ODD, N=37), relatives of 19 ADHD probands without ODD and CD (ADHD, N=71), relatives of 38 ADHD probands with ODD and without CD (ADHD+ODD, N=130), and relatives of 50 ADHD probands with ODD and CD (ADHD+ODD+CD, N=170).

Results

Rates of ADHD were significantly higher in all three ADHD groups compared to the Control group, while rates of ODD were significantly higher in all three ODD groups compared to the Control group. Evidence for co-segregation was found in the ADHD+ODD group. Rates of mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and addictions in the relatives were significantly elevated only in the ADHD+ODD+CD group.

Conclusions

ADHD and ODD are familial disorders, and ADHD plus ODD outside the context of CD may mark a familial subtype of ADHD. ODD and CD confer different familial risks, providing further support for the hypothesis that ODD and CD are separate disorders.

Keywords: ADHD, oppositional defiant, conduct, family risk

INTRODUCTION

Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) is the most common comorbidity of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Studies have shown that as many as 65% of youth with ADHD have ODD (Biederman et al., 1996b; Kadesjo and Gillberg, 2001; Kadesjo et al., 2003). The behaviors characterizing ODD -- temper outbursts, persistent stubbornness, resistance to directions, unwillingness to compromise with adults or peers, deliberate or persistent testing of limits, and verbal (and minor physical) aggression -- compound the difficulties of children with ADHD (Biederman et al., 1987; Biederman et al., 1991).

Yet, despite the high overlap between these disorders, there has been little investigation of ODD comorbid with ADHD (Loeber et al., 2000). Also, because ODD has been studied largely within the context of conduct disorder (CD), almost nothing is known about ODD proper. This is an important issue considering that a majority of children with ODD do not have CD and may not progress to CD in later years (Hinshaw et al., 1993; Lahey and Loeber, 1994; Biederman et al., 1996b). Furthermore, as shown by Greene and colleagues (2002), ODD is associated with substantial morbidity and significant family and social dysfunction, even when considered outside the context of CD, stressing the importance of disentangling the relationships between ADHD and ODD outside the context of CD.

One useful approach to evaluate the association between ADHD and ODD is to examine the familial transmission of these disorders. Familial risk analyses can address whether the aggregation of two disorders through families is compatible with various models of familial transmission as delineated by Pauls and colleagues (1986a; 1986; 1986b). While disruptive and antisocial behavior has been shown to aggregate in families (Loney et al., 1997; Lahey et al., 1998; Farrington et al., 2001), these models can help in disentangling the patterns of familial transmission of several disorders such as ADHD, ODD, and CD. Although these models have successfully clarified patterns of familial transmission between ADHD and CD (Faraone et al., 1998; Faraone et al., 2000), they have not been previously used to examine the association between ADHD and ODD.

An improved understanding of the nature of the association between ADHD and ODD has important scientific and clinical implications. It is possible that the abnormal behavioral and emotional difficulties seen in children with ODD might contribute to such youths being incorrectly classified as ADHD. Conversely, since oppositional behavior is so prevalent in youths with ADHD, such behavior might reflect ADHD and not a separate disorder. Since ADHD and ODD are each morbid psychiatric disorders, clarifying the overlap between them would assist in the development of appropriate interventions to help specifically target the needs of children with these clinical presentations.

The main purpose of this study was to use familial risk analysis to examine the association between ADHD and ODD while addressing the comorbidity with CD. Familial risk analysis examines rates of disorders in the relatives of probands with and without the disorders of interest in order to understand patterns of familial transmission. Co-segregation, the tendency for disorders to be inherited together, identifies the disorders of interest as a family subtype as opposed to independently transmitted. Previously, we have parsed the familial associations of ADHD and CD in a series of papers that suggested ADHD+CD is a distinct familial subtype of ADHD (Faraone et al., 1991; Faraone et al., 1997; Faraone et al., 2000). The current work extends this line of research by assessing the familial transmission of ODD when it occurs outside the context of CD. We tested three competing hypotheses: 1) ADHD and ODD are independently transmitted in families; 2) ODD plus ADHD represents a distinct subtype of ADHD; and 3) ADHD and ODD represent variable expressions of the same underlying risk factors. In addition, we further examined family risks by comparing the rates of mood, anxiety, and substance dependence in relatives of probands with and without ADHD, ODD, and CD. To the best of our knowledge this represents the first attempt at elucidating the familial association between ADHD and ODD.

METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were derived from a longitudinal case-control family study of boys with ADHD (Biederman et al., 1992; Biederman et al., 1996a; Biederman et al., 2006). At baseline, we ascertained male Caucasian subjects aged 6–17 years with (N=140) and without (N=120) DSM-III-R ADHD from pediatric and psychiatric clinics. Previously, this sample was followed-up at one year and four years after baseline. The present study reports on the ten-year follow-up of this sample, where 112 ADHD and 105 control probands were successfully re-ascertained. Details on attrition are provided in a previous publication (Biederman et al., 2006). Briefly, the rate of successful follow-up did not differ between the groups and there were no significant differences between those successfully followed up and those lost to follow-up on age, GAF score, familial intactness, ascertainment source, or psychiatric outcomes. At the 10-year follow-up, probands with ADHD were younger, had lower family socioeconomic status, and had higher lifetime rates of all psychiatric disorders compared to controls (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and psychiatric outcomes in ADHD and control probands at the 10-year follow-up. Mean±SD or N (%)

| Controls (N=105) | ADHD (N=112) | Test Statistic | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 22.8 ± 4.0 | 21.6 ± 3.3 | t(215)=2.27 | 0.02 |

| Family socioeconomic status | 1.4 ±0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | z=−2.63 | 0.009 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 18 (17) | 88 (79) | χ2(1)=81.84 | <0.001 |

| Conduct disorder | 17 (16) | 55 (49) | χ2(1)=26.48 | <0.001 |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 9 (10) | 27 (29) | χ2(1)=10.91 | 0.001 |

| Alcohol or drug dependence | 23 (22) | 38 (34) | χ2(1)=3.88 | 0.05 |

| Major depressive disorder | 10 (10) | 51 (46) | χ2(1)=34.78 | <0.001 |

| Bipolar disorder | 4 (4) | 39 (35) | χ2(1)=32.80 | <0.001 |

| Multiple (≥2) anxiety disorders | 14 (13) | 48 (43) | χ2(1)=23.15 | <0.001 |

For this analysis, probands were stratified according to ADHD ascertainment status, ODD diagnosis, and CD diagnosis (Table 2). Groups with fewer than 10 probands were dropped from this analysis (9 controls with CD, 8 controls with ODD and CD, and 5 ADHD probands with CD only). Therefore, the final sample consisted of 107 ADHD and 88 control probands and their first-degree relatives (N=371 and N=302, respectively). Parents were assessed at baseline only, while the siblings were assessed at baseline (N=218), one-year follow-up (N=227), four-year follow-up (N=247), and ten-year follow-up (N=271). Nearly all siblings were assessed at the ten-year follow-up (96%, N=271), while 4% were not (4-year follow-up, N=9; 1-year follow-up, N=2; baseline, N=1).

Table 2.

Demographics of families defined by proband diagnoses.

| Controls | ODD | ADHD | ADHD+ODD | ADHD+ODD+CD | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Age (Years) |

N | Age (Years) |

N | Age (Years) |

N | Age (Years) |

N | Age (Years) | Test statistic |

p-value | |

| Age at last assessment | ||||||||||||

| Probands | 78 | 22.4±3.9 | 10 | 23.7±3.6 | 19 | 22.0±3.4 | 38 | 21.4±3.1 | 50 | 21.6±3.4 | F(4,190)=1.25 | 0.29 |

| Mothers | 78 | 41.1±4.9 | 10 | 39.7±5.4 | 19 | 40.3±5.2 | 38 | 39.9±5.6 | 50 | 39.2±4.9 | F(4,190)=1.18 | 0.32 |

| Fathers | 77 | 43.4±5.4 | 10 | 41.8±6.8 | 19 | 42.5±6.4 | 38 | 43.3±5.4 | 50 | 42.9±6.8 | F(4,189)=0.25 | 0.91 |

| Siblings | 110 | 21.9±7.2 | 17 | 20.8±8.6 | 33 | 21.7±6.9 | 54 | 22.9±8.5 | 70 | 22.7±6.7 | F(4,171)=0.19 | 0.95 |

| Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | ||||||||

| Family socioeconomic status | 1.3±0.6 | 1.6±0.7 | 1.8±0.8* | 1.6±0.8 | 1.9±1.0** | χ2(4)=16.38 | 0.002 | |||||

p=0.008 vs. Controls

p<0.001 vs. Controls

As described previously (Biederman et al., 1992; Biederman et al., 1996a; Biederman et al., 2006), at baseline, 1-year follow-up, and 4-year follow-up, diagnostic assessments of ADHD were based on the K-SADS-E (Epidemiologic 4th Version) (Orvaschel and Puig-Antich, 1987). Parents and adult offspring provided written informed consent to participate, and parents also provided consent for offspring under the age of 18. Children and adolescents provided written assent to participate. The human research committee at Massachusetts General Hospital approved this study.

Follow-up Assessment Procedures

Lifetime psychiatric assessments at the ten-year follow-up relied on the K-SADS-E (Epidemiologic Version) (Orvaschel, 1994) for subjects younger than 18 years of age and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (First et al., 1997) (supplemented with modules from the K-SADS-E to assess childhood diagnoses) for subjects 18 years of age and older. Only 10% of probands (20/195) and 12% of relatives (82/673) were younger than 18 years of age at this assessment. We conducted direct interviews with subjects and indirect interviews with their mothers (i.e., mothers completed the interview about their offspring). We combined data from direct and indirect interviews by considering a diagnostic criterion positive if it was endorsed in either interview.

The interviewers were blind to the subject's ascertainment group, the ascertainment site, and all prior assessments. The interviewers had undergraduate degrees in psychology and were extensively trained. First, they underwent several weeks of classroom style training, learning interview mechanics, diagnostic criteria and coding algorithms. Then, they observed interviews by experienced raters and clinicians. They subsequently conducted at least six practice (non-study) interviews and at least three study interviews while being observed by senior interviewers. Trainees were not permitted to conduct interviews independently until they executed at least three interviews that achieved perfect diagnostic agreement with an observing senior interviewer. The principal investigator (JB) supervised the interviewers throughout the study. We computed kappa coefficients of agreement by having experienced, board certified child and adult psychiatrists and licensed clinical psychologists diagnose subjects from audio taped interviews. Based on 500 assessments from interviews of children and adults, the median kappa coefficient was 0.98. Kappa coefficients for individual diagnoses included: ADHD (0.88), CD (1.0), major depression (1.0), mania (0.95), separation anxiety (1.0), agoraphobia (1.0), panic (0.95), and substance use disorder (1.0).

We considered a disorder positive if DSM-IV diagnostic criteria were unequivocally met. A committee of board-certified child and adult psychiatrists who were blind to the subject's ADHD status, referral source, and all other data resolved diagnostic uncertainties. Diagnoses presented for review were considered positive only when the committee determined that diagnostic criteria were met to a clinically meaningful degree. We estimated the reliability of the diagnostic review process by computing kappa coefficients of agreement for clinician reviewers. For these diagnoses, the median reliability between individual clinicians and the review committee assigned diagnoses was 0.87. Kappa coefficients for individual diagnoses included: ADHD (1.0), CD (1.0), major depression (1.0), mania (0.78), separation anxiety (0.89), agoraphobia (.80), panic (.77), and substance use disorder (1.0).

Consistent with prior research (Gershon et al., 1982; Weissman et al., 1984) and our previous assessments, major depressive disorder was considered positive only if associated with severe impairment. Socioeconomic status (SES) was measured using the 5-point Hollingshead scale (Hollingshead, 1975).

Statistical Analysis

Relatives of probands were grouped according to the probands’ diagnoses of disruptive behavior disorders. Age and SES of probands and relatives were compared between the resulting five groups (Controls, ODD, ADHD, ADHD+ODD, and ADHD+ODD+CD). Controlling for any demographic confounds, rates of disruptive behavior disorders and other comorbidities were compared between the five groups of relatives. Linear regression was used to test age, ordered logistic regression was used to test SES, and logistic regression was used to test diagnoses. Analysis of alcohol and drug dependence was restricted to relatives fourteen years of age and older. To account for the non-independence of family members, we used the Huber correction (Huber, 1967) to produce robust variances for all statistical tests. All tests were two-tailed with alpha set at 0.05.

RESULTS

Comparisons were made between relatives of 78 control probands without ODD and CD (Controls, N=265), relatives of 10 control probands with ODD and without CD (ODD, N=37), relatives of 19 ADHD probands without ODD and CD (ADHD, N=71), relatives of 38 ADHD probands with ODD and without CD (ADHD+ODD, N=130), and relatives of 50 ADHD probands with ODD and CD (ADHD+ODD+CD, N=170). 11% of control probands (10/88) had ODD. Of ADHD probands, 82% had ODD (88/107) and 47% had conduct disorder (50/107). The ADHD and ADHD+ODD+CD groups had a significantly lower mean SES (i.e., higher Hollingshead’s score) compared to the Controls (Table 2). Therefore, pairwise comparisons between Controls and the ADHD and ADHD+ODD+CD groups controlled for SES. No differences were found in the age of probands or relatives.

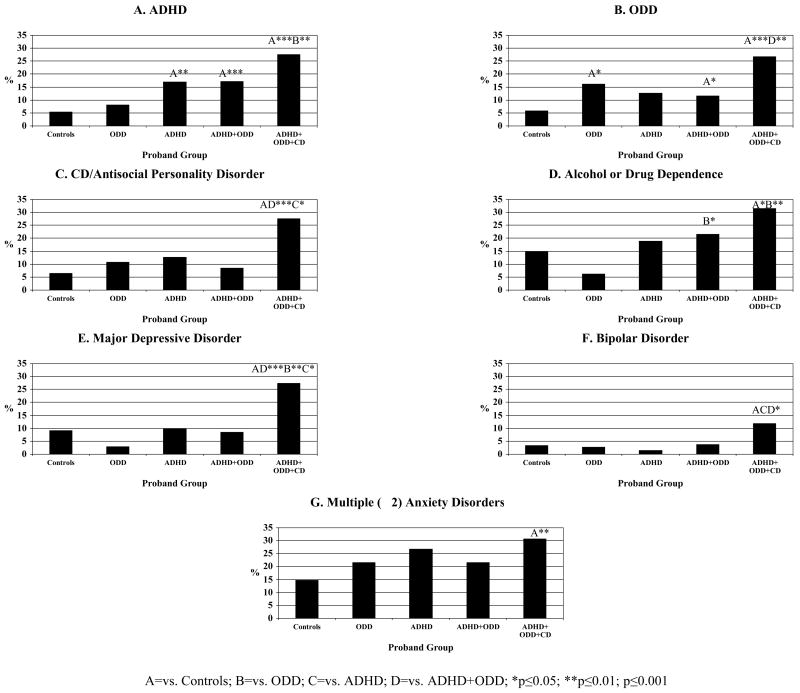

Disruptive Behavior Disorders in Relatives

All three ADHD groups had significantly higher rates of ADHD (ADHD+ODD+CD=27.5%, OR=1.6 [1.3,1.9], p<0.001; ADHD+ODD=17.2%, OR=1.5 [1.2,2.0], p<0.001; ADHD=16.9%, OR=2.0 [1.2,3.1], p=0.004) compared to the Control group (5.4%, Figure 1A), and the ADHD+ODD+CD group had a significantly higher rate of ADHD compared to the ODD group (8.1%, OR=1.6 [1.2,2.3], p=0.004). Similarly, rates of ODD were significantly higher in all three ODD groups (ADHD+ODD+CD=26.8%, OR=1.5 [1.3,1.8], p<0.001; ADHD+ODD=11.6%, OR=1.3 [1.0,1.7], p=0.04; ODD=16.2%, OR=3.2 [1.1,8.9], p=0.03) compared to the Control group (5.8%, Figure 1B), and the ADHD+ODD+CD group had significantly higher rates of ODD compared to the ADHD+ODD group (11.6%, OR=2.8 [1.5,5.3], p=0.002). The ADHD+ODD+CD group also had significantly higher rates of CD or antisocial personality disorder (27.6%, Figure 1C) compared to Controls and the two other ADHD groups (ADHD+ODD=8.5%, OR=4.1 [1.7,9.8], p=0.001; ADHD=12.7%, OR=1.6 [1.1,2.4], p=0.02; Controls=6.4%, OR=1.4 [1.2,1.6], p<0.001). Because ADHD alone in the proband did not increase the risk for ODD in the relatives, and ODD alone in the proband did not increase the risk for ADHD in the relatives, we can rule out the hypothesis of variable expressivity. The hypotheses of independent transmission and family subtype are still viable because all of the ADHD groups had elevated rates of ADHD and all of the ODD groups had elevated rates of ODD.

Figure 1.

Rates of disorders in first-degree relatives

Comorbidity, or lack thereof, of ADHD and ODD in relatives of probands with ADHD+ODD will determine which hypothesis of familial transmission outside the context of CD is the best fit. In the ADHD+ODD group, ODD was significantly more common in relatives with ADHD than without ADHD (40.9% versus 4.7%, OR=14.0 [4.1,47.2], p<0.001), signaling co-segregation of the two disorders in this group of families. Therefore, we can rule out the hypothesis of independent transmission. There was no evidence for nonrandom mating in the ADHD+ODD group (both p=1.00 for ADHD mother with ODD father and ODD mother with ADHD father using Fisher’s exact test). Because the comorbidity in the ADHD+ODD group was not due to the assortative mating of parents with ADHD and ODD, we can accept family subtype as the best fitting hypothesis.

Other Disorders in Relatives

The ADHD+ODD+CD group had significantly higher rates of alcohol or drug dependence (Figure 1D, 31.5% versus ODD=6.2%, OR=1.9 [1.2,3.0], p=0.005; Controls=15.0%, OR=1.2 [1.0,1.3], p=0.05), major depressive disorder (Figure 1E, 27.4% versus ADHD+ODD=8.5%, OR=4.1 [2.0,8.3], p<0.001; ADHD=10.0%, OR=1.8 [1.1,3.1], p=0.03; ODD=2.8%, OR=2.4 [1.3,4.3], p=0.005; Controls=9.1%, OR=1.3 [1.1,1.5], p<0.001), bipolar disorder (Figure 1F, 11.8% versus ADHD+ODD=3.8%, OR=3.4 [1.0,10.8], p=0.04; ADHD=1.4%, OR=3.1 [1,1,8.3], p=0.03; Controls=3.4%, OR=1.3 [1.0,1.6], p=0.02), multiple (≥2) anxiety disorders (Figure 1G, 30.6% versus Controls=14.7%, OR=1.2 [1.1,1.4], p=0.002). In addition, the ADHD+ODD group had a significantly higher rate of alcohol or drug dependence compared to the ODD group (21.5% versus 6.2%%, OR=2.0 [1.0,4.1], p=0.05) but did not differ significantly from the Controls.

DISCUSSION

Familial risk analysis was used to examine the association between ADHD and ODD using data from a large sample of ADHD male probands, non-ADHD comparisons, and their first-degree relatives. Compared with relatives of control probands, relatives of ADHD probands were at significantly greater risk for ADHD irrespective of the probands’ comorbidity with ODD or CD. Likewise, relatives of probands with ODD were at greater risk for ODD compared with relatives of controls, irrespective of proband ADHD or CD status. Co-segregation of ADHD and ODD was found outside the context of CD in the relatives of probands with ADHD and ODD. The risk for CD or antisocial personality disorder was identified only in relatives of the probands with CD. Relatives of probands with CD were also the only group at increased risk for mood and anxiety disorders and addictions. These findings suggest that ADHD plus ODD outside the context of CD may be a family subtype of ADHD and further support the hypothesis that there is a form of ODD that should be considered distinct from CD.

The finding that ADHD is robustly familial within and outside the context of ODD and CD in the probands is consistent with a large body of literature documenting that ADHD is a familial disorder with genetic influences (Biederman et al., 1992; Biederman et al., 1995; Faraone et al., 2005). For example, Biederman and colleagues (1992) previously documented a five-fold increased risk for ADHD in first-degree relatives of boys and girls with ADHD (Biederman et al., 1992). Studies of adults with ADHD document that 55% of their offspring have ADHD (Biederman et al., 1995; Faraone and Doyle, 2001). Likewise, the risk for ODD in relatives of probands with ODD was significantly greater than the risk in relatives of control probands, irrespective of comorbidity with ADHD or CD, indicating that ODD is also a familial disorder. These findings support the hypothesis that children with ADHD and ODD suffer from both disorders and not one or the other. That is, specific familial risks for each disorder provide validity for the distinctness of ADHD and ODD diagnoses.

We found that relatives of ADHD probands were are at significant risk for ODD only if the proband also has ODD, therefore ruling out the hypothesis of variable expressivity. Following the logic of Pauls et al. (1986a; 1986; 1986b), this finding could indicate that either a) the observed comorbidity between ADHD and ODD is an artifact or b) that ADHD plus ODD is a familially distinct condition. To compare these two hypotheses, we tested for co-segregation in families with a proband with ADHD plus ODD. If the comorbidity observed in probands was an artifact of referral bias, we should not observe co-segregation (i.e., comorbidity) among the relatives. Thus, our finding of co-segregation of ADHD and ODD rules out the hypothesis of independent transmission and supports the hypothesis that ADHD comorbid with ODD represents a distinct familial subtype. However, because the rates of ODD in relatives of ADHD probands without ODD were twice as high as those of relatives of control probands, it is possible that the variable expression of a common underlying risk factor accounted for the observed link between ADHD and ODD. Our sample may have been too small to detect differences between these groups. More work is needed to further examine these results.

The finding that antisocial, mood, anxiety, and addictive disorders in relatives selectively aggregated in probands with CD and not in probands with ODD supports the hypothesis that ODD and CD are separate and distinct entities. These family aggregation results extend previous phenomenological and follow-up findings that support the hypothesis that ODD is a heterogeneous disorder separate from CD (Biederman et al., 1996b; Greene et al., 2002). Taken together, these findings should discourage the practice of lumping together ODD and CD in clinical and research studies of disruptive behavior disorders. The familial association between CD with mood, anxiety, antisocial, and addictive disorders is also consistent with a body of literature documenting robust associations among CD, BPD, anxiety, and addictive disorders in probands and families (Wozniak et al., 2001; Wozniak et al., 2002; Biederman et al., 2003; Rende et al., 2007; Wilens et al., 2007). Recently, Bittner and colleagues (2007) found that childhood anxiety disorders were predictors of a range of psychiatric disorders in adolescence, including ADHD and CD. These findings, combined with our results showing an increased risk for anxiety disorders in relatives of probands with ADHD+ODD+CD, suggest that more work should be done to understand the possible mediating effect of anxiety on the development of disruptive behavior disorders as well as the familial transmission of anxiety and disruptive behavior disorders.

Our findings must be viewed in the context of some methodological limitations. Because the sample consisted of referred youth, findings may not generalize to community samples. Referred cases have potentially more comorbidity (Berkson, 1946), which could explain why 82% of probands with ADHD in this analysis had ODD or ODD+CD at the 10-year follow-up. The high comorbidity in probands could have an effect on the rates and patterns of disorders in the relatives. Because probands were boys, future studies should examine familial transmission in girls, particularly because girls with CD are known to have different patterns of comorbidity with ADHD (Loeber and Keenan, 1994), depression (Nottelmann and Jensen, 1995), and substance use (Whitmore et al., 1997). Also, since the sample was comprised of largely Caucasian youth, these findings may not generalize to other populations. Because our ODD and ADHD groups were relatively small, pairwise comparisons with these groups had limited power. Not all siblings had passed through the age of risk for some disorders, which may have led to an under-representation of psychopathology in relatives of the probands. Likewise, while probands and their siblings were assessed at baseline and follow-up assessments, parents were assessed only at baseline. Thus, it is possible that additional cases of disorders emerged in the parents during the ten-year follow-up period. However, parents had already passed the age of risk for disruptive behavior disorders.

The ICD-10 Diagnostic Criteria for Research (World Health Organization, 1993) defines ODD as a subtype of CD. Specifically, youth who have a few ODD symptoms and a few CD symptoms would not meet criteria for a DSM-IV diagnosis but could receive an ICD-10 diagnosis of ODD. Rowe et al. (2007) concluded that youth that met ICD-10 but not DSM-IV criteria were substantially impaired. The ICD-10 and DSM-IV classification systems could therefore render different patterns of familial transmission of ODD and CD. For example, in addition to more cases of ODD, the ICD-10 nosology may lead to a familial risk pattern more akin to variable expressivity. Probands with ODD defined by ICD-10 may have relatives with higher rates of CD because the ODD defined by ICD-10 may have included CD symptoms.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that ADHD and ODD are familial disorders, and ADHD plus ODD outside the context of CD is a family subtype. In addition, CD and ODD confer very different familial risks, providing further support for the hypothesis that ODD and CD are separate disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grant R01HD036317-10 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Dr. Biederman) and by grant support from Shire LPC (Dr. Mick).

None

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

Mr. Carter R. Petty has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Monuteaux has nothing to disclose.

Ms. Samantha Hughes has nothing to disclose.

Ms. Jacqueline Small has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Stephen V. Faraone has had an advisory or consulting relationship with the following pharmaceutical companies: McNeil Pediatrics and Shire Pharmaceutical Development.

Dr. Joseph Biederman is currently a consultant/advisory board member for the following pharmaceutical companies: Janssen, McNeil, Novartis, and Shire.

Dr. Joseph Biederman is currently a speaker for the following speaker’s bureaus: Janssen, McNeil, Novartis, Shire, and UCB Pharma, Inc.

Dr. Eric Mick receives/d grant support, is/has been a speaker for, or is/has been on the advisory board for the following sources: McNeil Pediatrics and Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Shire and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

Dr. Stephen V. Faraone receives research support from the following sources: McNeil Pediatrics, Shire Laboratories, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of Child Health and Development and the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke.

Dr. Joseph Biederman is currently receiving research support from the following sources: Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Co., Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., McNeil, Otsuka, Shire, NIMH, and NICHD

In previous years, Dr. Joseph Biederman received research support, consultation fees, or speaker’s fees for/from the following additional sources: Abbott, AstraZeneca, Celltech, Cephalon, Eli Lilly and Co., Esai, Forest, Glaxo, Gliatech, NARSAD, New River, NIDA, Novartis, Noven, Neurosearch, Pfizer, Pharmacia, The Prechter Foundation, The Stanley Foundation, and Wyeth.

Carter R. Petty, M.A. - Statistical analyses, first draft of paper, literature search

Michael C. Monuteaux, Sc.D. - designed study, wrote protocol, managed data collection

Eric Mick, Sc.D. - managed analyses

Samantha Hughes, B.A. - literature search, referencing

Jacqueline Small, B.A. - literature search, referencing

Stephen V. Faraone. Ph.D. - designed study, wrote protocol, managed data collection

Joseph Biederman, M.D. - designed study, wrote protocol, managed data collection

All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Berkson J. Limitations of the application of fourfold table analysis to hospital data. Biometrics Bulletin. 1946;2:47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone S, Milberger S, Guite J, Mick E, Chen L, Mennin D, Marrs A, Ouellette C, Moore P, Spencer T, Norman D, Wilens T, Kraus I, Perrin J. A prospective 4-year follow-up study of attention-deficit hyperactivity and related disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996a;53:437–46. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830050073012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Keenan K, Benjamin J, Krifcher B, Moore C, Sprich-Buckminster S, Ugaglia K, Jellinek MS, Steingard R, Spencer T, Norman D, Kolodny R, Kraus I, Perrin J, Keller MB, Tsuang MT. Further evidence for family-genetic risk factors in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Patterns of comorbidity in probands and relatives in psychiatrically and pediatrically referred samples. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:728–38. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820090056010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Mick E, Spencer T, Wilens T, Keily K, Guite J, Ablon S, Reed ED, Warburton R. High risk for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among children of parents with childhood onset of the disorder: A pilot study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:431–435. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Milberger S, Garcia Jetton J, Chen L, Mick E, Greene R, Russell RL. Is childhood oppositional defiant disorder a precursor to adolescent conduct disorder? Findings from a four-year follow-up study of children with ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996b;35:1193–1204. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199609000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Mick E, Wozniak J, Monuteaux M, Galdo M, Faraone S. Can a subtype of conduct disorder linked to bipolar disorder be identified? Integration of findings from the Massachusetts General Hospital Pediatric Psychopharmacology Research Program. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;53:952–960. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Monuteaux M, Mick E, Spencer T, Wilens T, Silva J, Snyder L, Faraone SV. Young Adult Outcome of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Controlled 10 year Prospective Follow-Up Study. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:167–179. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Munir K, Knee D. Conduct and oppositional disorder in clinically referred children with attention deficit disorder: A controlled family study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1987;26:724–727. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198709000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Newcorn J, Sprich S. Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with conduct, depressive, anxiety, and other disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:564–577. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.5.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittner A, Egger HL, Erkanli A, Jane Costello E, Foley DL, Angold A. What do childhood anxiety disorders predict? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:1174–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone S, Biederman J, Garcia Jetton J, Tsuang M. Attention deficit disorder and conduct disorder: Longitudinal evidence for a familial subtype. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:291–300. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone S, Biederman J, Mennin D, Russell R, Tsuang M. Familial subtypes of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A 4-year follow-up study of children from antisocial-ADHD families. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;39:1045–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Keenan K, Tsuang MT. Separation of DSM-III attention deficit disorder and conduct disorder: Evidence from a family-genetic study of American child psychiatric patients. Psychological Medicine. 1991;21:109–121. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700014707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Monuteaux MC. Attention-deficit disorder and conduct disorder in girls: evidence for a familial subtype. Biological Psychiatry. 2000;48:21–29. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00230-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Doyle AE. The nature and heritability of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2001;10:299–316. viii–ix. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Perlis RH, Doyle AE, Smoller JW, Goralnick J, Holmgren MA, Sklar P. Molecular genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:1313–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP, Jolliffe D, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Kalb LM. The concentration of offenders in families, and family criminality in the prediction of boys' delinquency. J Adolesc. 2001;24:579–96. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gershon ES, Hamovit J, Guroff JJ, Dibble E, Leckman JF, Sceery W, Targum SD, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Goldin LR, Bunney WE., Jr A family study of schizoaffective, bipolar I, bipolar II, unipolar, and normal control probands. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1982;39:1157–67. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290100031006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene RW, Biederman J, Zerwas S, Monuteaux MC, Goring JC, Faraone SV. Psychiatric comorbidity, family dysfunction, and social impairment in referred youth with oppositional defiant disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1214–24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw S, Lahey B, Hart E. Issues of taxonomy and comorbidity in the development of Conduct Disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four Factor Index of Social Status. New Haven: Yale Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Huber PJ. The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under non-standard conditions. Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability. 1967;1:221–233. [Google Scholar]

- Kadesjo B, Gillberg C. The comorbidity of ADHD in the general population of Swedish school-age children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42:487–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadesjo C, Hagglof B, Kadesjo B, Gillberg C. Attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder with and without oppositional defiant disorder in 3- to 7-year-old children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45:693–9. doi: 10.1017/s0012162203001282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey B, Loeber R, Quay H, Applegate B, Shaffer D, Waldman I, Hart E, McBurnett K, Frick P, Jensen P, Dulcan M, Canino G, Bird H. Validity of DSM-IV subtypes of conduct disorder based on age of onset. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:435–442. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199804000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Loeber R. Framework for A Developmental Model of Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder. In: Routh DK, editor. Disruptive Behavior Disorders in Childhood. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 139–180. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Burke JD, Lahey BB, Winters A, Zera M. Oppositional defiant and conduct disorder: a review of the past 10 years, part I. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:1468–84. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200012000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Keenan K. The interaction between conduct disorder and its comorbid conditions: Effects of age and gender. Clinical Psychology Review. 1994;14:497–523. [Google Scholar]

- Loney J, Paternite C, Schwartz J, Roberts M. Associations between clinic-referred boys and their fathers on childhood inattention-overactivity and aggression dimensions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25:499–509. doi: 10.1023/a:1022689832635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nottelmann ED, Jensen PS. Comorbidity of disorders in children and adolescents: Developmental perspectives. Advances in Clinical Child Psychology. 1995;17:109–155. [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H. Schedule for Affective Disorder and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children Epidemiologic Version. 5. Ft. Lauderdale: Nova Southeastern University, Center for Psychological Studies; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H, Puig-Antich J. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children: Epidemiologic Version. Fort Lauderdale, FL: Nova University; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Pauls DL, Hurst CR, Kruger SD, Leckman JF, Kidd KK, Cohen DJ. Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome and attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity: Evidence against a genetic relationship. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986a;43:1177–1179. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800120063012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauls DL, Leckman JF. The inheritance of Gilles de la Tourette's Syndrome and associated behaviors: Evidence for autosomal dominant transmission. New England Journal of Medicine. 1986;315:993–997. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198610163151604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauls DL, Towbin KE, Leckman JF, Zahner GE, Cohen DJ. Gilles de la Tourette's Syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder: Evidence supporting a genetic relationship. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986b;43:1180–1182. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800120066013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rende R, Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Iyengar S, Keller M. Childhood-onset bipolar disorder: Evidence for increased familial loading of psychiatric illness. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:197–204. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000246069.85577.9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe R, Maughan B, Costello EJ, Angold A. Defining oppositional defiant disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:1309–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Leckman JF, Merikangas KR, Gammon GD, Prusoff BA. Depression and anxiety disorders in parents and children: Results from the Yale Family Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1984;41:845–852. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790200027004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore EA, Mikulich SK, Thompson LL, Riggs PD, Aarons GA, Crowley TJ. Influences on adolescent substance dependence: conduct disorder, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and gender. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;47:87–97. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens T, Biederman J, Adamson JJ, Monuteaux M, Henin A, Sgambati S, Santry A, Faraone SV. Association of bipolar and substance use disorders in parents of adolescents with bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:129–34. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioral disorders: Diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak J, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Blier H, Monuteaux MC. Heterogeneity of childhood conduct disorder: further evidence of a subtype of conduct disorder linked to bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2001;64:121–31. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak J, Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Richards J, Faraone SV. Parsing the comorbidity between bipolar disorder and anxiety disorders: A familial risk analysis. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2002;12:101–111. doi: 10.1089/104454602760219144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]