Abstract

Objective To assess the effects of social deprivation on survival after cardiac surgery and to examine the influence of potentially modifiable risk factors.

Design Analysis of prospectively collected data. Prognostic models used to examine the additional effect of social deprivation on the end points.

Setting Birmingham and north west England.

Participants 44 902 adults undergoing cardiac surgery, 1997-2007.

Main outcome measures Social deprivation with census based 2001 Carstairs scores. All cause mortality in hospital and at mid-term follow-up.

Results In hospital mortality for all cardiac procedures was 3.25% and mid-term follow-up (median 1887 days; range 1180-2725 days) mortality was 12.4%. Multivariable analysis identified social deprivation as an independent predictor of mid-term mortality (hazard ratio 1.024, 95% confidence interval 1.015 to 1.033; P<0.001). Smoking (P<0.001), body mass index (BMI, P<0.001), and diabetes (P<0.001) were associated with social deprivation. Smoking at time of surgery (1.294, 1.191 to 1.407, P<0.001) and diabetes (1.305, 1.217 to 1.399, P<0.001) were independent predictors of mid-term mortality. The relation between BMI and mid-term mortality was non-linear and risks were higher in the extremes of BMI (P<0.001). Adjustment for smoking, BMI, and diabetes reduced but did not eliminate the effects of social deprivation on mid-term mortality (1.017, 1.007 to 1.026, P<0.001).

Conclusions Smoking, extremes of BMI, and diabetes, which are potentially modifiable risk factors associated with social deprivation, are responsible for a significant reduction in survival after surgery, but even after adjustment for these variables social deprivation remains a significant independent predictor of increased risk of mortality.

Introduction

The link between poverty, socioeconomic inequalities, and increased mortality is well established,1 2 3 4 but the extent to which such inequalities can be modified is unknown. Cardiovascular disease is the commonest cause of premature death in the Western world and is closely related to socioeconomic deprivation.5 6 7 8 Cardiac surgery offers several procedures that are known to carry considerable prognostic benefit, particularly coronary artery and heart valve surgery in the presence of severe symptomatic valvular abnormalities.9 10 We examined whether this prognostic benefit applies across the socioeconomic spectrum.

Methods

Patient population

We reviewed data from the cardiac surgical databases of QuORU (the quality and outcomes research unit) and NWQIP (the north west quality improvement programme in cardiac interventions), which hold prospectively collected clinical information on all adults undergoing cardiac surgery in Birmingham and the north west of England. The data were acquired prospectively as part of the patient’s hospital admission and are based on the minimal dataset defined by the Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland11 with some customised additions. We excluded patients undergoing surgery requiring circulatory arrest, distal aortic surgery, transplantation, surgery for thoracic trauma, adult congenital surgery, surgery for acquired ventricular septal defect, and salvage operations as these are relatively uncommon and higher risk procedures. The study population comprised 44 902 patients undergoing cardiac surgery between 1 January 1997 and 31 December 2007. Social deprivation was calculated for all patients from their home postcode with the 2001 Carstairs scores.12 These scores, based on the 2001 census data for England and Wales, range from −5.71 (least deprived) to 21.39 (most deprived). We classified patients into three groups according to their self reported smoking status: “current smokers” for patients smoking up to or including a week before surgery, “ex-smokers” for those who discontinued smoking habits any time before surgery, and “never smoked.” Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2.

Aims of the study

We examined the influence on social deprivation on survival after cardiac surgery, identified clinical factors associated with social deprivation, and assessed whether adjustment for these factors influences the effect of social deprivation on outcomes.

Study end points

In hospital mortality was recorded locally. We used the central cardiac audit database, which is linked to the Office for National Statistics, to check this status and provide survival data after discharge (census date 1 December 2007 for QuORU and 1 July 2007 for NWQIP). In hospital mortality was defined as death at any time after surgery during the hospital admission.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data are expressed as medians and interquartile ranges. The level of significance (α) was set at 0.05 (two sided).

The analysis was conducted in two stages. Firstly, we examined whether deprivation, as described by the Carstairs score, was predictive of mortality in hospital and in longer term follow-up. Secondly, after identifying current and past smoking behaviour, body mass index, and diabetes as clinical factors associated with social deprivation, we examined the degree to which these mediated any excess mortality associated with deprivation.

The risk profile in cardiac surgery is commonly assessed with the European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation (EuroSCORE),13 which contains variables such as age, sex, and ventricular function known to influence outcomes. We developed prognostic models to examine whether there was an additional effect of social deprivation on all cause in hospital mortality and mid-term survival. In these models we added type of surgical procedure and surgeon (as a random effect/grouped frailty) to the (log) EuroSCORE value as patient level covariates. The EuroSCORE was log transformed (log EuroSCORE) as this achieved a substantial (nominally significant) improvement in model fit, as judged by the Aikaike’s information criterion.

We identified further factors associated with deprivation and included these in further models to explore the extent to which these measures described the risks associated with deprivation. We examined candidate continuous variables (BMI, social deprivation) for linearity in predictive response. In univariate analyses we established whether the untransformed variable predicted the outcome. We used Aikaike’s information criterion to identify appropriate transformation or, when these were superior, a restricted cubic spline. When these were significantly superior to alternative functional forms, we fitted a restricted cubic spline with 5 knots. We explored the extent to which the number of knots affected the model fit.

We used backwards stepwise selection to identify a parsimonious predictive model, excluding candidate explanatory variables when they did not improve the model fit. The criterion for consideration and inclusion in the model was P≤0.05.

Categorical models for in hospital mortality were conducted with PROC GLIMMIX in SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Time to event analyses were conducted with Cox constant proportional hazards models with approximate grouped frailty, in the statistical package R, using a gamma distribution for the frailty term.14 We explored alternative distributional forms for the frailty term

Data on EuroSCORE, Carstairs score, diabetes, type of surgery, sex, and consultant or centre were available for all patients. Data were unavailable on smoking in 53 patients, hypertension in 43, age in 45, and BMI in 480. Data on in hospital death were missing for one patient and on time to death for mid-term analysis for 1625.

Results

The study population comprised 44 902 patients (32 889 male), who received procedures at five different hospitals from 51 surgeons. The median age was 65 (interquartile range 58-71). Diabetes (type 1 or 2) was present in 7363 (16.4%) patients and hypertension in 24 010 (53.5%). At the time of surgery 9803 (21.9%) patients were current smokers, 21 697 (48.4%) were ex-smokers, and 13 349 (29.8%) had never smoked. Medians were 27 (25-30) for BMI, 4 (2-6) for EuroSCORE, and −0.54 (−2.19-2.27) for Carstairs score. Table 1 summarises the type of cardiac surgery.

Table 1.

Summary of cardiac procedures

| Cardiac procedures* | No (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 44 902 (100.00) |

| CABG | 32 005 (71.28) |

| Valve(s) only | 6765 (15.07) |

| CABG + valve(s) | 4092 (9.11) |

| CABG + other | 585 (1.30) |

| Valve(s) + other | 479 (1.07) |

| CABG + valve(s) + other | 179 (0.40) |

| Other | 797 (1.77) |

CABG=coronary artery bypass surgery.

*Valve refers to heart valve repair or replacement. Other refers to concomitant atrial fibrillation ablation, left ventricular aneurysmectomy, atrial septal defect repair, or closure of patent foramen ovale.

In hospital mortality

The all cause in hospital mortality was 3.3% (1461/44 902). In the initial multivariable analysis EuroSCORE, type of surgery and social deprivation were all independent predictors of in hospital mortality (table 2).

Table 2.

Predictors of in hospital mortality

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Multivariable non-linear mixed model* | ||

| Intercept | 0.001 (0.000 to 0.001) | <0.001 |

| Log EuroSCORE† | 8.822 (7.701 to 10.107) | <0.001 |

| CABG | 1 | |

| CABG + other | 1.271 (0.938 to 1.721) | <0.122 |

| CABG + valve(s) | 1.331 (1.147 to 1.545) | <0.001 |

| CABG + valve(s) + other | 2.189 (1.422 to 3.371) | <0.001 |

| Other | 1.897 (1.464 to 2.457) | <0.001 |

| Valve(s) only | 0.788 (0.675 to 0.919) | <0.003 |

| Valve(s) + other | 1.369 (0.962 to 1.949) | 0.081 |

| Carstairs score‡ | 1.029 (1.011 to 1.048) | <0.002 |

| Multivariable non-linear mixed model plus predictors of social deprivation*§ | ||

| Intercept | 0.005 (0.002 to 0.010) | <0.001 |

| Log EuroSCORE† | 8.532 (7.429 to 9.797) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.167 (1.010 to 1.347) | <0.036 |

| CABG | 1 | |

| CABG + other | 1.284 (0.947 to 1.741) | <0.108 |

| CABG + valve(s) | 1.300 (1.118 to 1.511) | <0.001 |

| CABG + valve(s) + other | 2.232 (1.447 to 3.444) | <0.001 |

| Other | 1.740 (1.323 to 2.289) | <0.001 |

| Valve(s) only | 0.743 (0.633 to 0.872) | <0.001 |

| Valve(s) + other | 1.343 (0.942 to 1.916) | 0.103 |

| Carstairs score‡ | 1.025 (1.006 to 1.043) | 0.009 |

| BMI | 0.924 (0.900 to 0.950) | <0.001 |

| BMI 1¶ | 1.000 (1.000 to 1.000) | <0.707 |

| BMI 2¶ | 1.003 (1.001 to 1.006) | <0.010 |

| BMI 3¶ | 0.994 (0.987 to 1.000) | <0.050 |

CABG=coronary artery bypass grafting (reference procedure); BMI=body mass index.

*Includes consultant surgeons as random effects (P=0.004).

†Odds ratio represents change in 1 natural log transformed EuroSCORE point.

‡Odds ratio represents change in 1 untransformed Carstairs score point.

§Smoking behaviour, diabetes, and BMI (all related to deprivation) added as additional candidate explanatory variables, although smoking behaviour did not improve model fit and so was excluded in stepwise selection process.

¶Higher order terms from fitting restricted cubic spline with 5 knots to describe effects of BMI as non-linear function. Knots for restricted cubic spline for BMI placed at 21.1, 24.9, 27.2, 29.8, and 35.38.

Survival analysis

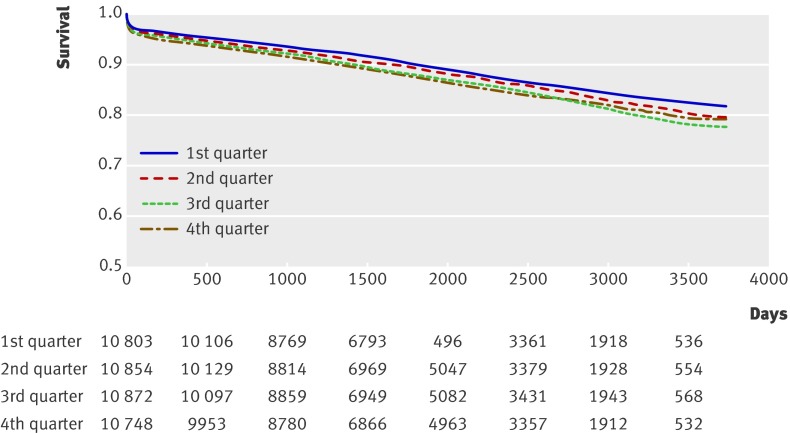

The median follow-up was 5.2 years (1887 days, interquartile range 1180-2725 days), and 5563 patients died during follow-up (12.4%). In the initial multivariable analysis EuroSCORE, type of surgical procedure, and social deprivation were all independent predictors for reduced long term survival. There was a 2.4% increased risk of mortality for each point increment in Carstairs score (table 3, fig 1).

Table 3.

Predictors of mid-term mortality

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Multivariable frailty model* | ||

| Log EuroSCORE† | 3.649 (3.447 to 3.863) | <0.001 |

| CABG | 1 | |

| CABG + other | 0.944 (0.783 to 1.137) | 0.540 |

| CABG + valve(s) | 1.243 (1.149 to 1.345) | <0.001 |

| CABG + valve(s) + other | 1.163 (0.842 to 1.605) | 0.36 |

| Other | 0.979 (0.820 to 1.170) | 0.82 |

| Valve(s) only | 0.902 (0.838 to 0.972) | <0.007 |

| Valve(s) + other | 0.903 (0.713 to 1.143) | 0.39 |

| Carstairs score‡ | 1.024 (1.015 to 1.033) | <0.001 |

| Multivariable frailty model plus predictors of social deprivation* | ||

| Log EuroSCORE† | 3.525 (3.327 to 3.736) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.305 (1.217 to 1.399) | <0.001 |

| CABG | 1 | |

| CABG + other | 0.952 (0.790 to 1.147) | 0.6 |

| CABG + valve(s) | 1.246 (1.150 to 1.350) | <0.001 |

| CABG + valve(s) + other | 1.228 (0.889 to 1.696) | 0.21 |

| Other | 0.973 (0.807 to 1.174) | 0.78 |

| Valve(s) only | 0.919 (0.851 to 0.993) | 0.032 |

| Valve(s) + other | 0.930 (0.734 to 1.177) | 0.540 |

| Carstairs score‡ | 1.017 (1.007 to 1.026) | <0.001 |

| Current smoker | 1.294 (1.191 to 1.407) | <0.001 |

| Ex-smoker | 1.245 (1.165 to 1.330) | <0.001 |

| BMI | 0.941 (0.928 to 0.954) | <0.001 |

| BMI 1§ | 1.000 (1.000 to 1.000) | 0.56 |

| BMI 2§ | 1.003 (1.001 to 1.004) | <0.001 |

| BMI 3§ | 0.994 (0.991 to 0.998) | <0.001 |

CABG=coronary artery bypass grafting (reference procedure); BMI=body mass index.

*Includes consultant surgeon as frailty term (P<0.0001).

†Hazard ratio represents change in 1 natural log transformed EuroSCORE point.

‡Hazard ratio represents change in 1 untransformed Carstairs score point.

§Higher order terms from fitting restricted cubic spline with 5 knots to describe effects of BMI as non-linear function. Knots for restricted cubic spline for BMI were placed at 21.1, 24.9, 27.2, 29.8, and 35.38.

Fig 1 Survival curves for quarters of social deprivation (Carstairs scores). First quarter least deprived, fourth quarter most deprived

Factors associated with social deprivation

Additional multivariable analysis identified that deprivation was associated with smoking, extremes of BMI, and diabetes, in addition to EuroSCORE, and type of procedure (table 4). The final multivariable model for in hospital mortality included BMI, diabetes, smoking, and social deprivation (table 2).

Table 4.

Clinical predictors of social deprivation

| Variable | Estimate* (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Current smoker | 0.9172 (0.8356 to 0.9989) | <0.001 |

| Ex-smoker | 0.2946 (0.2287 to 0.3605) | <0.001 |

| Never smoked† | 0 | |

| CABG† | 0 | |

| CABG + other | 0.0873 (−0.1556 to 0.3302) | 0.481 |

| CABG + valve(s) | −0.2114 (−0.3132 to −0.1097) | <0.001 |

| CABG + valve(s) + other | −0.5406 (−0.9751 to −0.1062) | 0.015 |

| Other | 0.1151 (−0.1011 to 0.3313) | 0.297 |

| Valve(s) only | −0.1427 (−0.2285 to −0.05683) | 0.001 |

| Valve(s) + other | −0.2386 (−0.5067 to 0.0294) | 0.081 |

| Log Euroscore | 0.07098 (0.02499 to 0.117) | 0.003 |

| Diabetes | 0.6437 (0.5687 to 0.7188) | <0.001 |

| BMI | −0.07049 (−0.08712 to −0.05386) | <0.001 |

| BMI 1‡ | −0.00008 (−0.00015 to −0.00001) | 0.017 |

| BMI 2‡ | 0.006199 (0.004857 to 0.007542) | <0.001 |

| BMI 3‡ | −0.01247 (−0.01578 to −0.00916) | <0.001 |

*Estimate indicates the actual effect of the variable on Carstairs score.

†Reference variable.

‡Higher order terms from fitting restricted cubic spline with 5 knots to describe effects of BMI as non-linear function. Knots for restricted cubic spline for BMI placed at 21.1, 24.9, 27.2, 29.8, and 35.38 (kg/m2).

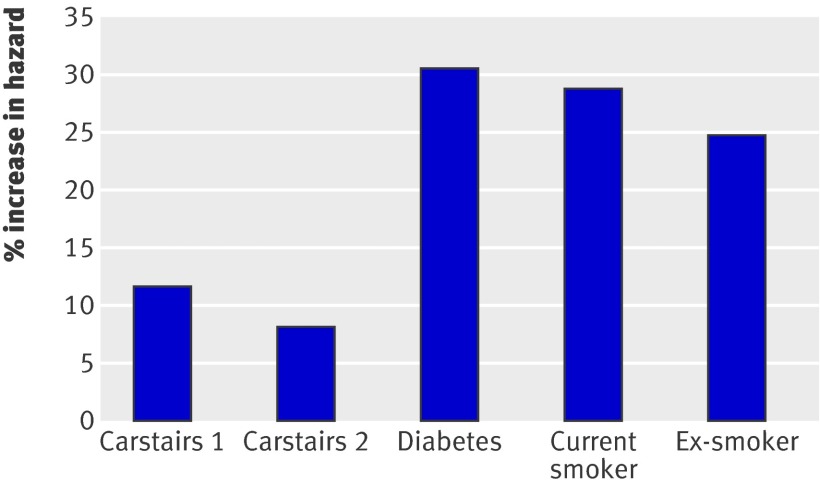

The inclusion of BMI, diabetes, and smoking in the multivariable model for mid-term survival led to a reduction in the risk of mortality because of social deprivation from 2.4% to 1.7% for each point increment in Carstairs score, resulting in an overall reduction in mortality of 29%. In this model, diabetes carried a 31% increased risk and smoking a 29% increased risk of death (table 3, fig 2). Figure 3 shows the non-linear effects of varying BMI on the risk of mid-term mortality, where lower and higher BMI both carry increased risk, with approximate 95% confidence intervals. There were no first order statistical interactions between the Carstairs score and the other included patient level covariates.

Fig 2 Percentage increase in hazard of death during mid-term follow-up. Carstairs 1: increased risk for 5 point increment in Carstairs score when diabetes, smoking, and BMI are not included in model. Carstairs 2: increased risk for 5 point increment in Carstairs score when diabetes, smoking, and BMI are included in model

Fig 3 Non-linear effects of varying BMI on risk of mid-term mortality, with approximate 95% confidence intervals

Discussion

Social deprivation has a substantial independent adverse effect on survival in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Smoking, extremes of BMI, and diabetes were strongly associated with social deprivation, but even after we adjusted for these factors deprivation remained a predictor of reduced survival in hospital and at mid-term. Our study included a large number of patients undergoing cardiac surgery, selected from five participating centres and treated by several surgeons, which taken together are probably representative of patients and practice in the United Kingdom and other similar health systems. We are not aware of previous studies investigating the influence of social deprivation on mid-term outcomes after cardiac surgery.

Predictors of in hospital mortality

Hospital mortality after cardiac surgery depends on several well known clinical factors. These are used in various risk stratification scoring systems to evaluate the patients’ operative risk of death, of which the EuroSCORE is the most widely used in Europe.13 This scoring system, however, does not contain diabetes or obesity as risk factors. In the initial multivariable model for in hospital mortality, social deprivation had a small but significant negative influence on mortality. Smoking, diabetes, and BMI were strongly associated with social deprivation and when they were introduced in the analysis as potential predictive variables the effect of social deprivation was largely retained.

Predictors of mid-term mortality

The EuroSCORE has also been shown to be a strong predictor of long term survival after cardiac surgery,11 15 16 and our report confirms this finding. We found that social deprivation was an additional strong predictor of mortality, even when we introduced smoking, diabetes, and BMI in the analysis. The most deprived patients also present to surgery with a higher risk profile.

Smoking and body mass index

Obesity, defined as a BMI >30, is a documented risk factor for cardiac surgery17 and both smoking and obesity contribute to health related inequalities across the socioeconomic spectrum in population based studies.4 7 We identified exposure to smoking as having a significant, additional adverse effect on mid-term survival after cardiac surgery: the additional risk of death after cardiac surgery was 29% for patients smoking at time of surgery and 25% for ex-smokers.

The relation between BMI and survival in our study was non-linear, as previously shown by others,17 and risks were higher in the extremes of BMI, with minimum risks occurring near a BMI of 27.

Obesity is a major healthcare problem both in the United States, where 65% of adults are overweight or obese,18 and England. The link between obesity and social deprivation is well established,19 and the adverse effects of high BMI on survival in the general population have been previously reported.20 Epidemiological data suggest that the problem of obesity is spreading across socioeconomic boundaries,21 and in time this could potentially lead to a reduction in the benefits of cardiac surgery for all patients. The current “epidemic” of obesity has been related to changes in type of work, leisure, and transport and the availability of different foodstuffs—the so called “obesogenic environment.”22 The quality of physical environment also affects physical activity levels and obesity.23 The World Health Organization has issued recommendations on prevention and management of the obesity epidemics.24

In our report low BMI also predicted reduced mid-term survival after surgery, in accordance with previous longitudinal reports25 and post-interventional cardiology studies.26 Our data, however, do not allow an in depth analysis of the mechanisms underlying these findings. Most chronic diseases tend to cause loss of weight, and in some patients low BMI could be a marker of end stage cardiovascular disease. An inverse relation between body weight and smoking has been shown previously,25 and the increased mortality in patients with low BMI in our study might be explained, at least in part, by the effects of smoking related diseases. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes among patients with cardiovascular disease undergoing cardiac surgery is high and its link with obesity is well known.11 27

Diabetes

Diabetes, which is not included in the EuroSCORE, was linked with social deprivation and was associated with a 31% additional risk of death after cardiac surgery. The outcome of cardiac surgery in people with diabetes is worse than in those without,11 28 and it is known that people with diabetes have an increased perioperative and late mortality.29 Although there are well known genetic non-modifiable risk factors for the development of diabetes, recent trials have shown that pharmacological and lifestyle interventions can reduce its incidence in high risk populations.30

Cardiovascular disease is progressive, so given the success of the National Service Framework for Coronary Heart Disease29 in building infrastructure and services in England, this raises the question of whether the observed differences are related to targeting of resources, access to services, and education or to an understanding of how to engage with and benefit from available healthcare facilities.

Limitations of the study

The mortality data presented refer to all cause mortality and do not allow an in depth analysis of the relations between causes of death and risk factors associated with social deprivation. We used Carstairs scores to evaluate social deprivation based on district of residence, derived from census and postcode data. While such measures have limitations, the Carstairs deprivation index has been shown to perform well particularly in explaining variations in health inequalities.12 The data on smoking in our database represent a temporal snapshot of this habit at the time of surgery. We have no data to validate the compliance of non-smokers at the time of surgery, neither have we information on smoking habits after surgery for all patients. Our study was based on several datasets; in future better linkage of patients’ data could allow a better understanding of the impact of several risk factors, and trialling targeted intervention in socially deprived populations might show that outcomes are really modifiable. Finally, in the current dataset we cannot examine any additional prognostic information related to ethnicity and its relation with social deprivation.

In summary, people from deprived socioeconomic groups not only have a shorter life expectancy but also spend a greater proportion of their lives affected by disability or illness.2 Cardiac surgical procedures are generally performed for symptomatic relief or prognostic benefit, and usually both. We have raised the concern that the effect of proved healthcare interventions might not be equally distributed across socioeconomic boundaries. We have identified some important modifiable clinical factors that if addressed might substantially reduce the adverse effects of social deprivation on mid-term survival after cardiac surgery, pointing to the need for comprehensive rehabilitation programmes before and after surgery that include aggressive smoking cessation, nutritional, and behavioural support.

Even after correction for smoking history, BMI, and diabetes, however, the influence of social deprivation on survival remained predictive, indicating that some additional factors related to deprivation might influence outcome. In the face of easy access to effective health care the real challenge lies in developing a coherent health conscious approach to education and to the environment. This is essential to maximise the benefits of expensive and complex healthcare interventions such as cardiac surgery.

What is already known on this topic

The link between poverty, socioeconomic inequalities, and increased mortality is well established

Cardiovascular disease is a common cause of premature death in the West

Cardiac surgery offers a range of operations to improve prognosis

What this study adds

Social deprivation reduces the prognostic benefits of cardiac surgery

Addressing issues of smoking obesity and diabetes could reduce the negative impact of social deprivation on outcome after cardiac surgery

We thank Matthew Shaw and Vivian Barnet for their help in data collection and analysis.

The following consultant surgeons participated in this study:

North West Quality Improvement Programme in Cardiac Interventions—John Au, Colin Campbell, John Carey, John Chalmers, Walid Dhimis, Abdul Deiraniya, Andrew Duncan, Brian Fabri, Elaine Griffiths, Geir Grotte, Ragheb Hasan, Tim Hooper, Mark Jones, Daniel Keenan, Neeraj Mediratta, Russell Millner, Nick Odom, Brian Prendergast, Mark Pullan, Abbas Rashid, Franco Sogliani, Paul Waterworth, and Nizar Yonan. Narinda Bhatnagar, Albert Fagan, Bob Lawson, Udin Nkere, Peter O’Keefe, Richard Page, Ian Weir, and David Sharpe left the collaboration during the study period.

Quality and Outcomes Research Unit—Robert S Bonser, Timothy R Graham, Stephen J Rooney, Jorge Mascaro, and Ian C Wilson.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study. NF conducted the statistical analyses. DP is the guarantor

Funding: No funding.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:b902

References

- 1.Department of Health and Social Services. Inequalities in health: report of a research working group (the Black report). London: DHSS, 1980.

- 2.Acheson D. Independent inquiry into inequalities in health. London: Stationery Office, 1998.

- 3.Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE, Cavelaars AE, Groenhof F, Geurts JJ. Socioeconomic inequalities in morbidity and mortality in western Europe. The EU Working Group on Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health. Lancet 1997;349:1655-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AJ, Schaap MM, Menvielle G, Leinsalu M, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2468-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Vinogradova Y, Robson J, Minhas R, Sheikh A, et al. Predicting cardiovascular risk in England and Wales: prospective derivation and validation of QRISK2. BMJ 2008;336:1475-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marmot MG, Rose G, Shipley M, Hamilton PJ. Employment grade and coronary heart disease in British civil servants. J Epidemiol Community Health 1978;32:244-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pekkanen J, Tuomilehto J, Uutela A, Vartiainen E, Nissinen A. Social class, health behaviour, and mortality among men and women in eastern Finland. BMJ 1995;311:589-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tunstall-Pedoe H, Woodward M. By neglecting deprivation, cardiovascular risk scoring will exacerbate social gradients in disease. Heart 2006;92:307-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonow RO, Carabello B, de Leon AC Jr, Edmunds LH Jr, Fedderly BJ, Freed MD, et al. Guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease). Circulation 1998;98:1949-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yusuf S, Zucker D, Peduzzi P, Fisher LD, Takaro T, Kennedy JW, et al. Effect of coronary artery bypass graft surgery on survival: overview of 10-year results from randomised trials by the Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery Trialists Collaboration. Lancet 1994;344:563-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keogh B, Kinsman R. Fifth national adult cardiac surgical database report 2003. Reading: Deandrite Clinical Systems, 2004.

- 12.Morgan O, Baker A. Measuring deprivation in England and Wales using 2001 Carstairs scores. Health Stat Q 2006;31:28-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nashef SA, Roques F, Michel P, Gauducheau E, Lemeshow S, Salamon R. European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation (EuroSCORE). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1999;16:9-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Team RDC. A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2004.

- 15.Pagano D, Howell NJ, Freemantle N, Cunningham D, Bonser RS, Graham TR, et al. Bleeding in cardiac surgery: the use of aprotinin does not affect survival. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;135:495-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toumpoulis IK, Anagnostopoulos CE, Toumpoulis SK, DeRose JJ, Swistel DG. EuroSCORE predicts long-term mortality after heart valve surgery. Annals of Thoracic Surgery 2005;79:1902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner BD, Grunwald GK, Rumsfeld JS, Hill JO, Ho PM, Wyatt HR, et al. Relationship of body mass index with outcomes after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;84:10-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill JO, Peters JC. Environmental contributions to the obesity epidemic. Science 1998;280:1371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sobal J, Stunkard AJ. Socioeconomic status and obesity: a review of the literature. Psychol Bull 1989;105:260-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simopoulos AP, Van Itallie TB. Body weight, health, and longevity. Ann Intern Med 1984;100:285-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang VW, Lauderdale DS. Income disparities in body mass index and obesity in the United States, 1971-2002. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:2122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Government Office for Science. Foresight: tackling obesities: future Choices—project report. London: Department of Innovation Universities and Skills, 2007www.foresight.gov.uk/OurWork/ActiveProjects/Obesity/KeyInfo/Index.asp.

- 23.Ellaway A, Macintyre S, Bonnefoy X. Graffiti, greenery, and obesity in adults: secondary analysis of European cross sectional survey. BMJ 2005;331:611-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO. Obesity: preventing and managing the world epidemics. Geneva: WHO, 1998.

- 25.Wannamethee G, Shaper AG. Body weight and mortality in middle aged British men: impact of smoking. BMJ 1989;299:1497-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gruberg L, Weissman NJ, Waksman R, Fuchs S, Deible R, Pinnow EE, et al. The impact of obesity on the short-term and long-term outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: the obesity paradox? J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:578-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romao I, Roth J. Genetic and environmental interactions in obesity and type 2 diabetes. J Am Diet Assoc 2008;108(suppl 1):S24-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seven-year outcome in the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation (BARI) by treatment and diabetic status. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:1122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galinanes M, Fowler AG. Role of clinical pathologies in myocardial injury following ischaemia and reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res 2004;61:512-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delahanty LM, Nathan DM. Implications of the diabetes prevention program and Look AHEAD clinical trials for lifestyle interventions. J Am Diet Assoc 2008;108(suppl 1):S66-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]