Abstract

Viruses deliver their genome into host cells where they subsequently replicate and multiply. A variety of relevant strategies have evolved by which viruses gain intracellular access and utilize cellular machinery for the synthesis of their genome. Therefore, the viral journey provides insight into the cell’s trafficking machinery and how it can be best exploited to improve nonviral gene delivery systems. This review summarizes viral internalization pathways and intracellular trafficking of viruses, with an emphasis on the endosomal escape processes of nonenveloped viruses. Intracellular events from viral entry through nuclear delivery of the viral complementary DNA are also discussed.

Key words: escape process, nuclear delivery, uptake mechanism, virus

INTRODUCTION

Viruses are considered smart living organisms because they have the ability to invade intracellular organelles and effectively infect host cells. Once viruses enter the body of a potential host, they penetrate mucus layers, move through the bloodstream, disperse with the help of motile cells and neuronal pathways, and replicate in living host cells (1). To multiply, viruses must successfully deliver their genome into host cells and use their intracellular machinery for replication. Efficient viral infection is achieved depending on the following sequence of events: (a) binding to cell surface receptors, (b) internalization pathways into cells, (c) escape from endocytic vesicles, and (d) nuclear delivery of the genome. Depending on the type of virus, simple or complex, different strategies mediate an efficient infection as a result of their interaction with cells during their journey. Simple viruses use a most efficient method of releasing their genome into the cytosol: It crosses the plasma membrane after the viruses bind to specific cell surface receptors (2). In the case of complex viruses, they enter cells by classical endocytosis. After internalization, complex viruses that are localized in endosomes can escape endocytic vesicles under suitable conditions, as they have developed ways to mediate their escape. The escape strategies employed by viruses depend on the type of virus. Enveloped viruses fuse with endosomal membranes, whereas nonenveloped viruses lyse or form pores to release the viral genome (3). Thus, an elegant strategy has evolved, whereby viruses avoid lysosomal degradation, which is a dead end for many particles in a classic endocytic pathway. As a result of their communication with cells, complex viruses have developed other ways to exploit nonclassic endocytosis, such as a unique caveolar pathway to move into the cell. This internalization route is comprised of a neutral pH compartment, which allows viruses to avoid degradation at low pH. Interestingly, this internalization pathway also mediates trafficking of viruses, such as Simian virus 40 (SV40), to intracellular organelles, including the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), before the viral genome enters the nucleus (4). Therefore, it is evident that viral evolution over millions of years has resulted in the acquisition of strategies whereby viruses utilize and control cell functions.

In this review, we briefly discuss the mechanisms of cellular uptake of viruses and endosomal escape with particular emphasis on nonenveloped viruses. In addition, we discuss the intracellular trafficking and nuclear entry of SV40. Viruses are valuable models of cellular entry and intracellular trafficking pathways. Therefore, viruses provide information that can be used to improve nonviral gene delivery systems.

RECEPTORS AND CORECEPTORS

To infect, viruses must first bind to the cell surface. The molecules to which viruses bind encompass a wide variety of different proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates (1). Some of them function as attachment factors or true receptors. Attachment factors enable viruses to bind and to concentrate on the cell surface. These interactions are relatively nonspecific and do not induce conformational changes in the viruses (5). For example, some molecules that act as attachment factors for initial contacts of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) are mannose binding C-type lectin, the dendritic cell-specific intracellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-3-grabbing nonintegrin, and the liver and lymph node-specific ICAM-3-grabbing nonintegrin (1). Unlike attachment factors, receptors not only bind viruses but also actively promote their entry into cells. Binding to receptors on the plasma membrane is the first step in viral infection and is usually highly specific (5). A study of diversity of viral receptors shows that viruses use a variety of receptors to target select cells (Table I). In addition, receptors that viruses use for internalization are either primary receptors or coreceptors. For example, sialic acid has been identified as a primary receptor for many viruses, such as Ad8 (8), Ad37 (8), Jamestown Canyon (JC) virus (22), AAV5 (26), BK virus (22), and murine polyoma virus (22,51). Viruses such as human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) and dengue virus have different receptors for their internalization depending on the cell types. The initial event in HCMV infection in fibroblast cells is its attachment to extracellular heparan sulfate proteoglycans as a cellular receptor (17). In addition, this receptor is also utilized by dengue envelope protein to bind to target nondendritic cells (14). Interestingly, binding to leptin is required for HCMV and dengue virus to infect dendritic cells (15,18). These data indicate that receptors for mediating infection of human cytomegalovirus and dengue virus are cell type dependent.

Table I.

Biochemical and Cell Biological Features of Viral Infection

| Family | Virus example | Characteristic | Genome | Size (nm) | Receptor | Uptake route | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenoviridae | Ad2, Ad5 | Nonenveloped | dsDNA | 80–110 | CAR, coreceptor: αvβ5 integrin | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (6,7) |

| Adenoviridae | Ad8, Ad37 | Nonenveloped | dsDNA | 80–110 | α(2,3)-linked sialic acid | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (8) |

| Asfarviridae | African swine fever virus | Enveloped | dsDNA | 175–215 | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (9) | |

| Filoviridae | Ebolavirus | Enveloped | ssRNA(−) | 80 | Folate receptor-α, lectin | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (10,11) |

| Flaviviridae | Hepatitis C virus | Enveloped | ssRNA(+) | 50 | CD81, SR-B, lectin | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (12) |

| Flaviviridae | Tick-borne encephalitis virus | Enveloped | ssRNA | 40–60 | HSPG | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (13) |

| Flaviviridae | Dengue virus | Enveloped | ssRNA(+) | 40–60 | Lectin, HSPG | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (14,15) |

| Hepadnaviridae | HBE | Enveloped | dsDNA | 40–48 | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (16) | |

| Herpesviridae | HCMV | Enveloped | dsDNA | 100–110 | HSPG, lectin | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (17,18) |

| Orthomyxoviridae | Influenza A virus | Enveloped | ssRNA(−) | 80–120 | Sialic acid | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (3,19) |

| Papillomaviridae | HPVs | Nonenveloped | dsDNA | 40–55 | HSPG, α6β4 integrin | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (20,21) |

| Papovaviridae | JC virus | Nonenveloped | dsDNA | 40–50 | Sialic acid GT1b, coreceptor: 5HT-2a | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (22) |

| Parvoviridae | AAV-2 | Nonenveloped | ssDNA | 20–25 | HSPG, coreceptor: HFGFR I, αvβ5 | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (23–25) |

| Parvoviridae | AAV-5 | Nonenveloped | ssDNA | 20–25 | α(2,3)-linked sialic acid | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (26) |

| Parvoviridae | Minute virus of mice | Nonenveloped | ssDNA | 20–26 | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (27) | |

| Parvoviridae | Canine parvovirus | Nonenveloped | ssDNA | 20–26 | 40- and 42-kDa glycoprotein | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (28) |

| Picornaviridae | Parechovirus type 1 | Nonenveloped | ssRNA(+) | 30–60 | αvβ3 integrin, αvβ1 integrin | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (29,30) |

| Picornaviridae | Minor human rhinoviruses (HRV-2) | Nonenveloped | ssRNA(+) | 30 | LDL | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (31) |

| Poxyviridae | Vaccinia virus | Enveloped | dsDNA | 250–360 | 32 kDa protein | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (32,33) |

| Reoviridae | Reovirus | Nonenveloped | dsRNA | 60–80 | JAMs | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (34) |

| Retroviridae | Avian leukosis sarcoma virus | Enveloped | ssRNA(+) | Tissue necrosis factor-related protein | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (35,36) | |

| Rhabdoviridae | Rabies virus | Enveloped | ssRNA(−) | 45–100 | Acetylcholine, NCAM | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (3,37) |

| Rhabdoviridae | VSV | Enveloped | ssRNA(−) | 70 | Phosphatidylserine | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (2,38) |

| Togaviridae | Sindbis virus | Enveloped | ssRNA | 70 | HSPG | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (39,40) |

| Alphaviridae | Semliki forest virus | Enveloped | RNA(+) | 50–70 | CD155, HLA-A, HLA-B, murine H-2d | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (39,41) |

| Togaviridae | Rubella virus | Enveloped | ssRNA(+) | 50–60 | Phospholipids and glycolipids | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | (42,43) |

| Papillomaviridae | Papillomavirus (HPV-31) | Nonenveloped | dsDNA | 50–55 | Unknown | Caveolar endocytosis | (44) |

| Papovaviridae | BK virus | Nonenveloped | dsDNA | 45–55 | α(2,3)−linked sialic acid GD1b, GT1b | Caveolar endocytosis | (22) |

| Paramyxoviridae | NDV | Enveloped | ssRNA(−) | 150–300 | Beta-anomer of sialic acid | Caveolar endocytosis | (45,46) |

| Paramyxoviridae | RSV | Enveloped | ssRNA(−) | 125–250 | Unknown | Caveolar endocytosis | (47) |

| Picornaviridae | Coxsackie B viruses | Nonenveloped | ssRNA(+) | 20–30 | CAR, coreceptor: DAF | Caveolar endocytosis | (5,48,49) |

| Picornaviridae | EV1 | Nonenveloped | ssRNA(+) | 24–30 | α2β1 integrin VLA-2 | Caveolar endocytosis | (50) |

| Polyomaviridae | SV40 | Nonenveloped | dsDNA | 45–50 | GM1 ganglioside | Caveolar endocytosis | (22) |

| Polyomaviridae | Murine polyoma virus | Nonenveloped | dsDNA | 40–50 | Sialic acid, GM1, GD1a, GT1b | Caveolar endocytosis | (22,51) |

| Herpesviridae | HSV-1 | Enveloped | dsDNA | 100–110 | HVEA, HSPG, nectin-1α, nectin-1β | Fusion with plasma membrane | (52) |

| Herpesviridae | Epstein barr virus | Enveloped | dsDNA | 120–220 | CD21, CR2 | Fusion with plasma membrane | (53,54) |

| Paramyxoviridae | HPIV-3 | Enveloped | ssRNA(−) | 125–250 | HSPG, sialic acid | Fusion with plasma membrane | (55) |

| Paramyxoviridae | Measles virus | Enveloped | ssRNA(−) | 125–250 | SLAM | Fusion with plasma membrane | (56,57) |

| Paramyxoviridae | Sendai virus | Enveloped | ssRNA(−) | 125–250 | Sialic acid | Fusion with plasma membrane | (58) |

| Paramyxoviridae | NDV | Enveloped | ssRNA(−) | 150–300 | Beta-anomer of sialic acid | Fusion with plasma membrane | (59) |

| Paramyxoviridae | RSV | Enveloped | ssRNA(−) | 125–250 | Unknown | Fusion with plasma membrane | (60) |

| Retroviridae | HIV-1 | Enveloped | ssRNA(+) | 120 | CD4 coreceptors: CCR5, CXCR4 | Fusion with plasma membrane | (2,61) |

| Retroviridae | Murine leukemia virus (MLV) | Enveloped | ssRNA(+) | 90 | CAT1 | Fusion with plasma membrane | (2,62) |

| Arenaviridae | LCMV | Enveloped | ssRNA(−) | 110–130 | Alpha-dystroglycan | Microfilament-independent pathway | (63,64) |

| Adenoviridae | Ad2 | Nonenveloped | dsDNA | 80–110 | CAR, coreceptor: αvβ5 integrin | Macropinocytosis | (7,65) |

| Orthomyxoviridae | Influenza virus | Enveloped | ssRNA(−) | 80–120 | Sialic acid | Clathrin-independent pathway | (3,66) |

| Picornaviridae | Poliovirus | Nonenveloped | ssRNA(+) | 22–30 | Ig-family | Dynamin-independent pathway | (67) |

| Picornaviridae | Major HRVs (HRV-14) | Nonenveloped | ssRNA(+) | 25–30 | ICAM-1 | Dynamin-independent pathway | (68,69) |

| Picornaviridae | EV11 | Nonenveloped | ssRNA(+) | 24–30 | DAF | Lipid-raft-dependent pathway | (70) |

| Reoviridae | Rotavirus | Nonenveloped | dsRNA | 60–80 | α2β1& αvβ3 integrin, Hsc70 | Ca(2+)-dependent endocytosis | (71–73) |

| gangliosides, N-linked glycoproteins |

dsDNA single-stranded DNA, AAV-2 adeno-associated virus-2, HRV-2 human rhinoviruses type 2, HPIV-3 human parainfluenza virus-3, Ad2 adenovirus type 2, ssRNA single stranded RNA, CD81 cluster of differentiation 81, SR-B scavenger receptor class B, HSPG heparan sulfate proteoglycan, HBE hepatitis B virus, HCMV human cytomegalovirus, HPVs human papillomaviruses, JC Jamestown Canyon, NCAM neural cell adhesion molecule, JAMs junctional adhesion molecules, LDL low-density lipoproteins, VSV vesicular stomatitis virus, CD155 cluster of differentiation 155, HLA-A human leukocyte antigens A, HLA-B human leukocyte antigens B, murine H-2d, HPV-31 human papillomavirus type 31, NDV Newcastle disease virus, RSV respiratory syncytial virus, CAR coxsackie–adenovirus receptor, DAF decay accelerating factor, VLA-2 very late antigen 2, EV1 echovirus 1, SV40 Simian virus 40, HSV-1 herpes simplex virus type 1, HVEA herpesvirus entry mediator A, CD21 cluster of differentiation 21, CR2 complement receptor 2, SLAM signaling lymphocyte activation molecule, CD4 cluster of differentiation 4, CCR5 chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 5, CXCR4 chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4, LCMV lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, ICAM-1 intracellular adhesion molecule 1, EV11 echovirus 11, Hsc70 70-kD heat shock cognate protein

In many cases, the signals from activation of primary receptors are not sufficient to stimulate viral entry. Thus, viruses recruit and activate coreceptors at the cell surface for their internalization. In general, coreceptors have lower affinities for binding constants of as low as millimolar compared with primary receptors, so they act after binding to primary receptors to enhance their binding strength (74). Some viruses that use coreceptors are JC virus (22), Coxsakie B viruses (49), and HIV-1 (61). In addition, cellular signal molecules also can be activated and used by viruses as coreceptors. For example, as a coreceptor, many viruses use an integrin signal such as Ad2 and Ad5 (7), human papillomavirus (21), parechovirus (29,30), echovirus 1 (50), and rotavirus (71–73). Kinases are also used to accommodate internalization of viruses, as at least five different kinases are required and activated for internalization of SV40 into cells. In addition, inhibition of tyrosine kinase significantly reduces its infection (75). Accordingly, viruses associate with either a variety of receptors or coreceptors to initiate intracellular signaling for their successful infection.

UPTAKE MECHANISM

Endocytosis is a fundamental process by which macromolecules are taken into cells. There are several endocytic routes by which viruses are internalized into cells: clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolar endocytosis, and clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocytosis. In addition, some viruses enter cells through direct fusion with the plasma membrane. To discover the diversity of mechanisms by which viruses are internalized into cells, we gathered information and summarized it in Table I.

Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is the major cellular entry pathway for many viruses (Table I). Several viruses are also internalized via caveolar endocytosis, while other viruses fuse directly to the plasma membrane. In addition, a few viruses are taken up into cells via clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocytosis (Table I). Thus, these data indicate that the diversity of viral entry pathways is limited. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is the best-characterized endocytic pathway. Generally, the binding of a ligand to a specific receptor results in the clustering of the ligand-receptor complexes in coated pits on the plasma membrane. The coated pits then invaginate and pinch off from the plasma membrane to form intracellular clathrin-coated vesicles. Depolimerization of these vesicles results in early endosomes, which fuse with each other to form late endosomes that further fuse with lysosomes (76). Molecules that are internalized via clathrin-mediated endocytosis rapidly experience a decline in pH from neutral to a pH of approximately 6 in the early endosomes. Molecules then traffic to the late endosomes and are ultimately degraded in lysosomes, which have a pH of approximately 5 (76). Although lysosomes are a dead end for many molecules that are internalized into the cells via this route, in the case of viruses, they have the ability to avoid lysosomal degradation, as they can escape from the endosomes to the cytosol.

Caveolar Endocytosis

Role of Viral Size in Caveolar Endocytosis

The number of viruses that enter cells via caveolar endocytosis as an alternative uptake pathway is less than that using clathrin-mediated endocytosis (Table I). Most of these viruses are nonenveloped and are less than 55 nm. Evidently, the actual size of a single flask-shaped caveolae is very small (60–80 nm; 77) to allow the accommodation of nonenveloped viruses. Thus, these viruses, of less than 55 nm in diameter, are internalized via caveolar endocytosis. However, large viruses, such as Newcastle disease virus (NDV) and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which are approximately ∼300 and ∼250 nm in diameter, respectively (Table I), are also internalized into cells through small vesicle caveolae (46,47). Therefore, internalization by caveolae most likely is not restricted by size. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that large latex beads preferentially enter cells via caveolar endocytosis (78). Therefore, the size dependence of internalization via caveolar endocytosis remains questionable. Alternatively, the binding of viruses to their receptors in caveolae may accommodate internalization. The target molecule of NDV is sialic acid which in fact is a known receptor in the caveolae vesicle (79). It is also well documented that several proteins other than sialic acid are expressed in the caveolae, such as the folic acid receptor, GPI anchor, gp60, autocrine motility factor receptor, interleukin-2 receptor, GM1 gangliosides, α2β1-integrin, platelet-derived growth factor, epidermal growth factor, bradykinin, and the cholecystokinin receptor (79,80). At this stage, although the cell surface receptor molecule that mediates caveolar endocytosis of RSV is yet to be identified, RSV may target an unidentified molecule in the caveolae. Presumably, binding of viruses such as NDV and RSV to their protein receptors in the caveolae can facilitate their internalization into cells.

Caveolae-Mediated Transcytosis

Internalization via caveolar endocytosis is considered a unique pathway. This caveolae-mediated pathway involves important transport processes, most notably transcytosis (77). Transcytosis is the process by which macromolecules, such as immunoglobulin and albumin, internalized within caveolae are transported from the apical side of endothelial cells to the basal side or are transported in the reverse direction. This strategy is used by cells to selectively move macromolecules between two environments (81). Thus, caveolar endocytosis overcomes the endothelial barrier by means of transcytosis, thereby delivering the carrier from the apical to the basolateral side.

Transcytosis of viruses occurs widely in many polarized epithelial cell types. This process is rapid and viruses transcytose from apical to basolateral of the epithelial cells without infection (82). Examples of viruses that transcytose the epithelial cells are poliovirus, HIV, and vesicular stomatitis viruses. Poliovirus is thought to cross epithelial M cells that are scattered in the epithelial sheet covering the lymphoid follicles of Peyer’s patches before it reaches the intestine. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that poliovirus transcytoses from the apical to the basolateral compartment of M-like cells (83). These cells contain monolayers of polarized Caco-2 enterocytes cocultured with lymphocytes isolated from Peyer’s patches. Translocated poliovirus from the apical side may infect enterocytes through the basolateral side of M cells. Infected cells would then liberate virions from their apical face in the intestinal lumen (83). In the case of transcytosis by HIV-1, the virus is delivered to the basolateral side of the epithelium HEC-1 cells where it can spread into the submucosa (84). For HIV, transcytosis is receptor-mediated, in which its receptor is identified as galactosyl-ceramide. To traverse the epithelial cells, HIV requires intact microtubules and remains infectious after passage (84). Reportedly, the membrane glycoprotein G of vesicular stomatitis virus is transfected into the apical membrane of Madin–Darby canine kidney cells that are transcytosed through the endosomal compartment to the basolateral plasma membrane (85). Although some G proteins are also trafficked into lysosomes for degradation at higher temperature, this organelle is not an important kinetic intermediate in the transcytosis route, because transcytosis of G protein is still taking place. In addition, the process occurs after most of the G protein is transported to the basolateral membrane (85). Further study shows an absence of any involvement of the Golgi complex in transcytosis, indicating that the Golgi complex is not a part of the trafficking of G protein to reach the basolateral membrane (86). The intracellular trafficking of viral transcytosis is yet to be clarified as to how they traverse to the basolateral side of the epithelial layer.

Recently, an electron microscopy study by Schnitzer demonstrated that transcytosis actually occurs in the endothelium. In this study, an antibody specific for a caveolar membrane protein, TX 3.833, translocated across endothelial cells (77). In addition, these investigators confirmed that binding of albumin to its receptor, gp60, initiates transport across a continuous endothelium via caveolae-mediated transcytosis (87).

Direct Fusion with the Plasma Membrane

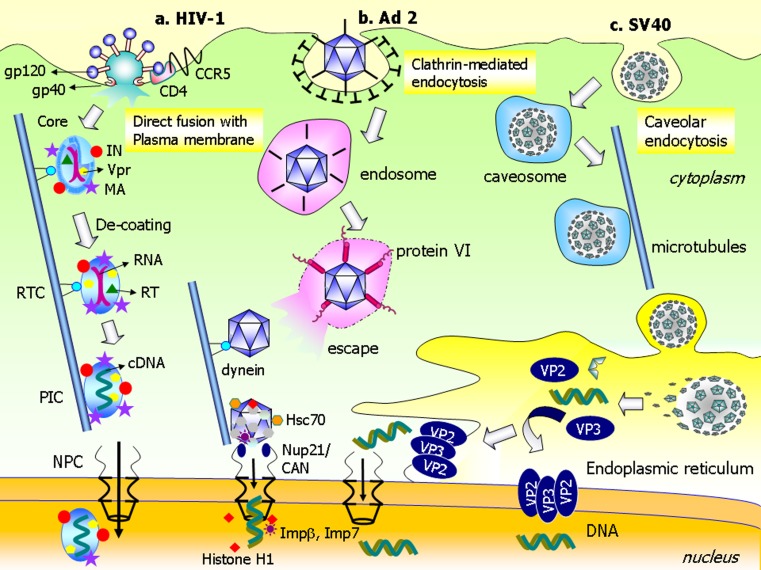

In the case of direct membrane fusion, viruses enter cells via fusion with the plasma membrane at neutral pH. This route, which is used only by enveloped viruses, is the most efficient way to deliver viral DNA or RNA to the cytosol (2). During the internalization process, enveloped viruses fuse with the plasma membrane after fusion-promoting viral proteins are recognized by specific cell surface receptors. This process is limited to some species of retroviridae, paramyxoviridae, and herpesviridae, as listed in Table I. The fusion mechanism of HIV-1 is well-characterized. HIV-1 has two glycoproteins on its surface—gp120 and gp41—that facilitate cellular uptake (61). When gp120 binds to the primary receptor, CD4, it undergoes a conformational change that allows the virus to associate with its coreceptors, which are the chemokine receptors CCR5 and CXCR4 (61; Fig. 1). The interaction between gp120 and either CCR5 or CXCR4 leads to insertion of gp41 into the plasma membrane. In membrane fusion, gp41 plays an important role because it contains a hydrophobic fusion peptide at its N terminus region. Fusion between HIV-1 and plasma membrane leads to the release of RNA into the cytoplasm (61).

Fig. 1.

Selected mechanisms of intracellular trafficking and nuclear delivery of VIRAL genome. a Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) enters cells via direct fusion with the plasma membrane. gp120 binds to the primary receptor, CD4, and undergoes a conformational change that allows the HIV-1 to associate with its coreceptor, CCR5. This interaction leads to insertion of gp41 into the plasma membrane to mediate fusion. The core is then internalized into the cytoplasm. The capsid core binds dynein and moves along microtubules toward the nucleus. During trafficking, decoating of the capsid results in formation of the reverse transcription complex (RTC). The RNA is converted into complementary DNA by reverse transcriptase (RT) in the preintegration complex (PIC). Matrix protein (MA), integrase (IN), and/or Vpr protein mediate delivery of PIC across the NPC into the nucleus. b After adenovirus type 2 (Ad2) is internalized through clathrin-mediated endocytosis; fiberless Ad2 is entrapped in the endosomes. Protein VI of the Ad capsid causes membrane disintegration and allows Ad to escape the endosomes via detergent-like mechanisms. Ad moves along the microtubules toward the nucleus via interactions with dynein. The Ad capsid is then transported to the NPC where it directly attaches to Nup21/CAN. The Ad–NPC interaction recruits the heat shock protein, Hsc70, and the nuclear histone H1 and H1 import factors, importin β and importin 7. These factors facilitate decoating of Ad and delivery of viral genomic DNA into the nucleus. c SV40 is taken up by cells via caveolar endocytosis and, subsequently, is entrapped in the caveosomes. SV40 traffics to the ER along microtubules. Once inside the ER, the capsid is decoated by ER-resident molecular chaperones. This process leads to dissociation of capsid proteins, in particular VP2 and VP3. These proteins oligomerize and insert into the membrane to facilitate escape of genomic DNA from the ER into the cytoplasm via pore-formation mechanisms. Nuclear delivery of genomic DNA probably occurs in two ways. The genomic DNA is imported to the nucleus from the cytosol after escaping the ER. Another possibility is that the DNA is delivered directly into the nucleus across the ER membrane

Clathrin- and Caveolae-Independent Pathways

Some viruses are internalized into cells by clathrin- and caveolae-independent pathways such as dynamin-independent, microfilament-independent, clathrin-independent, lipid raft-dependent, and macropinocytotic pathways. Poliovirus and human rhinovirus type 14 (HRV14) are taken up by a dynamin-independent pathway (67,69). After internalization, these viruses are trapped in vesicles that do not contain dynamin. Dynamin is a large GTPase that plays a key role in “pinching off” coated vesicles to form coated pits during classical clathrin-mediated endocytosis (67). Although this vesicle is lacking in dynamin, they also can be pinched from the plasma membrane and can then transport poliovirus and HRV14 to the endosomes. In general, influenza virus is taken up through clathrin-mediated endocytosis (3,19). However, there are exceptional cases where viruses are internalized via clathrin-independent endocytosis (66). Adenovirus 2 (Ad2) is internalized mostly through clathrin-mediated endocytosis, after it activates αv integrin coreceptors as a result of the binding of Ad2 to its primary receptor (88). The uptake of Ad2 by this route requires a large GTPase dynamin, PI3K, small GTPases Rac1 and Cdc42, and also Rab5 (88). A second endocytic process which induced the uptake of Ad is macropinocytosis. These two different uptake processes of Ad2 occur simultaneously in cells and together are associated with viral infection (65,88). The uptake of Ad2 via macropinocytosis also requires integrins and small G proteins of the Rho family with additional signals from protein kinase C and F-actin, but not dynamin (88). Macropinocytosis, per se, is not required for the uptake of Ad into epithelial cells, but it appears to be a productive entry pathway of Ad when artificially targeted to the high-affinity Fcγ receptor CD64 of hematopoietic cells lacking coxsackievirus–adenovirus receptor (CAR; 88). Another virus that is internalized into cells via a clathrin- and caveolae-independent pathway is echovirus 11 (EV11) in which lipid rafts are used to achieve intracellular internalization after recognition of EV11 by its receptor, decay accelerating factor (DAF; 70). Collectively, these data suggest a variety of uptake pathways that occur by a clathrin- and caveolae-independent mechanism. However, this mechanism has not been well characterized, most likely because no specific inhibitor is currently available.

ENDOSOMAL ESCAPE

After viruses are internalized into cells via the endocytic pathways, they must escape from the endosome to the cytosol. Basically, viruses are divided into two types: enveloped viruses and nonenveloped viruses. The mechanism of escape depends on the type of virus. Enveloped viruses utilize membrane fusion to cross the membrane barrier and reach the cytoplasm. Nonenveloped viruses use a mechanism of membrane disruption or pore formation to escape the endosomes (3).

Fusion-Dependent Mechanism

Escape of enveloped viruses requires fusion between the viral envelope and the endosomal membrane. Fusion-related events occur in the endocytic vesicles and are mediated by fusion proteins. In the low-pH environment of endosomes, fusion proteins undergo conformational changes, such that exposed hydrophobic residues are inserted into and subsequently fuse with the membrane bilayer, enabling cytosolic translocation of the viral genome (89).

Fusion proteins are classified as class I and class II based on the protein structure that results from conformational rearrangement after the fusion process occurs (89). Fusion protein of this class I protein is trimeric in both their prefusion and postfusion conformations, in which it forms α-helical coils postfusion. A prototypical class I fusion protein is the influenza virus protein hemagglutinin (HA). In the acidic environment of the endosomes, HA mediates the fusion of the viral and endosomal membranes. During this process, HA undergoes significant structural transitions. In common with other type I viral fusion proteins, HA is a trimer that exhibits no fusion activity unless the biosynthetic precursor HA0 is cleaved into the HA1 and HA2 polypeptides (89,90). Other fusogenic proteins of class I include the following: F1 protein, GP2 protein, TM protein, and S2 protein from simian virus 5 (91), ebola virus (92), moloney murine leukemia virus (93), and mouse hepatitis virus (94). As opposed to class I, class II fusion proteins undergo an oligomeric rearrangement during fusion, converting from the prefusion dimer to a more stable homotrimer. Formation of the inserted homotrimer to the endosomal membrane is required for a class II fusion protein in which a trimer of hairpins forms a β-structure (89). The class II fusion protein is found in flaviviruses such as Tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) with E protein as its fusogenic protein (95). In low pH compartments, the TBEV E–E homodimers dissociate, resulting in disassembly of the icosahedral scaffold followed by a reorganization into E protein inserted in the membrane to mediate fusion (95). Another fusion protein in class II is the E1 protein that is found in alphaviruses such as the semliki forest virus (96).

Fusion-Independent Mechanisms

Unlike enveloped viruses, nonenveloped viruses have to escape from the endosomes via fusion-independent mechanisms. There are two alternative mechanisms proposed for escape via the fusion-independent mechanism. Those are membrane disruption via a carpet-like mechanism and transmembrane pore formation via a barrel-stave mechanism (97). These two mechanisms follow a different concept. In the carpet mechanism, the peptides are in contact with the lipid head group during the entire process of membrane permeation and do not insert into the hydrophobic core of the membrane (97). With a barrel-stave mechanism, the peptides insert into the hydrophobic core of the membrane to form transmembrane pores (97,98).

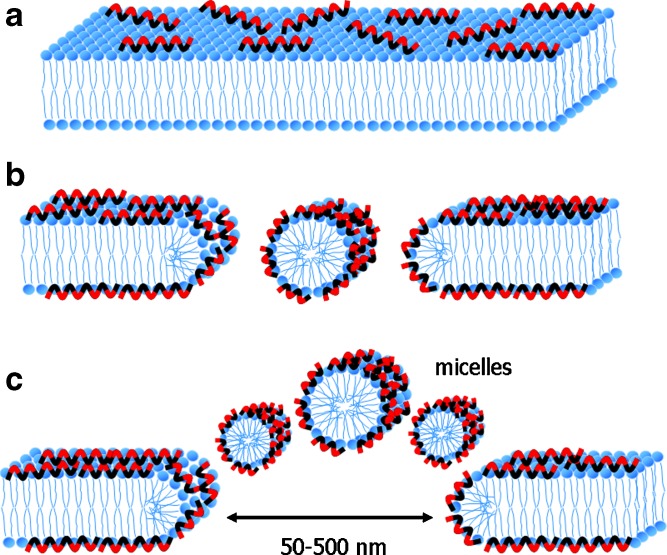

Membrane Disruption

An earlier study proposed a mechanism of membrane disruption that is known as the “carpet mechanism” (99). In this mechanism, peptides initially bind onto the surface of the membrane, cover it in a carpet-like manner, and lead to membrane disruption (Fig. 2). An electrostatic interaction is essential to initiate binding between the peptides and the target membrane, whereas a specific structure upon its binding to the membrane is not required (97,98). Four steps are proposed for this model: (a) Positively charged peptide monomers initially bind to negatively charged phospholipids. (b) The peptide monomers are aligned on the surface of membrane so that their hydrophilic group faces the phospholipid head groups or water molecules. Membrane permeation is induced by either surface covering of the membrane with the peptide monomers or, alternatively, an association between membrane-bound peptides forming a localized carpet. However, high local concentration on the surface of the membrane is required to induce membrane permeation. (c) The hydrophobic group of peptides reorientates toward the hydrophobic core of the membrane. (d) The membrane disintegrates when the lipid bilayer is disrupted leading to micellization (97,98). The carpet model mechanism is characterized by a general disruption of the bilayer in a detergent-like manner, eventually leading to the formation of micelles at high peptide concentrations. Therefore, the carpet mechanism is also known as a detergent-like mechanism (100).

Fig. 2.

A model of a carpet-like mechanism for membrane disruption. In this model, the peptides disrupt the membrane by covering the lipid membrane with an extensive layer of peptide. a The peptides electrostatically bind to the surface of lipid membrane so that hydrophobic groups of peptides face the membrane and their hydrophilic groups face water molecules. Hydrophobic groups of the peptide are shown colored black and hydrophilic groups of the peptide are shown colored red. b, c After local high concentration of peptides occurs on the surface of phospholipids, membrane permeation is triggered. Lipid membranes are then disintegrated leading to micellization. At this stage, a transient hole is formed before the membrane is thoroughly disintegrated (97,98). The size of the transient hole that forms in this mechanism can be exemplified by lytic activity of the flock house virus. The γ1 peptide of this virus induces transient holes of approximately 50–500 nm (100)

Some viruses, such as adenovirus group C, adenovirus group B, papillomavirus, and HRV14, disrupt endosomal membranes via a detergent-like mechanism (Table II). Reportedly, the penton base of Ad is the substance responsible for membrane disruption (101). Recently, protein VI has been shown to play a role in membrane disruption, as it has membrane lytic activity (102). In the low-pH environment of endosomes, the N-terminal amphipathic α-helix of protein VI undergoes a conformational change from its buried position within hexon-protein VI at neutral pH. The exposed protein VI is then inserted into the endosomal membrane. This interaction leads to a dissolution of the endosomal membrane, mediating the release of genomic DNA. The detergent-like activity of protein VI was demonstrated by observing the deletion of the amphipathic sequence from protein VI, VIΔ54, and resulted in a complete loss of membrane lytic activity at pH 5.5 (102). Because various Ad, such as Ad2 and Ad5, also contain protein VI, it is probable that they also have membrane lytic activity (102).

Table II.

List of Viruses with Fusion-Independent Escape Mechanism for Infection

| Family | Example | Type | Genome | Molecule | Trigger | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenoviridae | Ad group C | Nonenveloped | dsDNA | Protein VI | Low pH | Detergent-like | (102) |

| Adenoviridae | Ad group D (Ad37) | Nonenveloped | dsDNA | Fiber | Unknown | Detergent-like | (103) |

| Papillomaviridae | Papillomavirus | Nonenveloped | dsDNA | L2 | Low pH | Detergent-like | (105) |

| Picornaviridae | HRV14 | Nonenveloped | ssRNA(+) | VP1, VP4 | Detergent-like | (106) | |

| Nodaviridae | Flock house virus | Nonenveloped | ssRNA(+) | γ1 | Detergent-like | (100) | |

| Picornaviridae | HRV2 | Nonenveloped | ssRNA(+) | VP1 | Pore formation | (108) | |

| Picornaviridae | Poliovirus | Nonenveloped | ssRNA(+) | VP4 | Pore formation | (110,111) | |

| Parvoviridae | Parvovirus | Nonenveloped | ssDNA | PLA2 | Low pH | Pore formation | (112) |

| Reoviridae | Reovirus | Nonenveloped | dsRNA | μ1N | Pore formation | (114) | |

| Reoviridae | BDV | Nonenveloped | ssRNA(+) | Pep46 | Pore formation | (115) | |

| Reoviridae | BTV | Nonenveloped | dsRNA | VP5 | Pore formation | (116) | |

| Reoviridae | Rotavirus | Nonenveloped | dsRNA | VP5 | Pore formation | (118) |

HRV14 human rhinoviruses type 14, HRV2 human rhinoviruses type 2, Ad37 adenovirus type 37, BDV bursal disease virus, BTV bluetongue virus, PLA2 phospholipase A2

Although the endosomal escape mechanism of Adenovirus 7 (Ad7) is the same detergent-like mechanism of Ad2, Ad7 escapes from lysosomes, rather than from endosomes, by using different key molecules. Ad7 escapes from the lysosomes with a fiber by enhancing the lytic activity (103). Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that compaction of DNA with the fiber peptide enhanced gene expression is accomplished by improving the efficiency of endosomal escape (104). Papillomavirus has a detergent-like mechanisms. The L2 peptide is a key molecule in this mechanism (105). The escape mechanism of HRV14, which is a member of the picornaviridae family, is also similar to that of adenovirus (106). In addition, γ1 peptide of flock house virus exhibited desorption in a membrane model (DPPC/DPPS = 4:1) in a quartz crystal microbalance experiment, indicating lysis of the phospholipids membrane after interaction with the γ1 peptide (100). The γ1 peptide induces transient holes of approximately 50–500 nm, as observed with scanning force microscope. It is hypothesized that the holes in the membrane are observed before the membrane disintegrates to a micelle form (100). Thus, these holes may enable the translocation of the viral genome to the cytosol prior to completion of membrane lysis. These results suggest that a detergent-like mechanism allows for partial disruption of the membrane to mediate the cytosolic release of the viral genome. Apparently, γ1 is able to bind to the membrane surface, forms mixed lipid/peptide micelles that desorb from the surface, and then passes through holes inside the membrane.

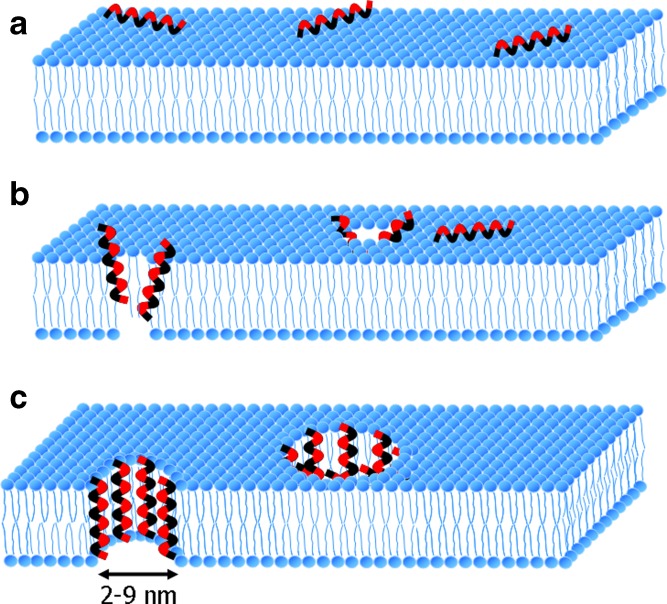

Pore Formation

Pore formation is another mechanism that is employed by nonenveloped viruses. The most widely accepted mechanism for pore formation is the barrel-stave mechanism (107). In this mechanism, transmembrane pores are formed in the interior regions of the membrane by bundles of amphipathic α-helices. In addition, their hydrophobic groups interact with the lipid core of the membrane and their hydrophilic groups face each other (Fig. 3; 97,98). Four major steps are involved in this mechanism: (a) The peptide monomers bind to the membrane in an α-helical structure. (b) The peptide monomers recognize each other in the membrane-bound state at low surface density of bound peptides. (c) Helices insert into the hydrophobic core of the membrane. (d) Recruitment of additional monomers occurs progressively to increase the pore size. Binding of the peptide monomers is essential on the surface of the membranes rather than that of a single peptide monomer. The use of peptide monomers facilitates direct contact between the peptides and the fatty acyl region of a lipid bilayer by hydrogen bonding. These hydrophobic interactions are the driving force for stimulating peptide–membrane binding. Thus, the electrostatic charge of peptides is not responsible for initiating peptide–membrane binding (97,98).

Fig. 3.

A model of a barrel-stave mechanism for transmembrane formation. a In this model, the peptides first assemble in the surface of the membrane and peptide monomers bind to the membrane in an α-helical structure. b Amphiphatic α-helical peptides insert into the membrane bilayer. The hydrophobic peptide groups of peptides align with the lipid core of the membrane and the hydrophilic peptide regions form the interior region of the pore. c Additional monomers are recruited to increase pore size (97,98). Hydrophobic groups of the peptide are shown in black, whereas hydrophilic groups of the peptide are shown in red. The formed pores in this mechanism are less than 10 nm in diameter, as shown by μ1N, pep46, and VP1 as peptides of reovirus (114), bursal disease virus (115), and HRV2 (108), respectively

Some viruses, such as picornaviridae, parvoviridae, and reoviridae, utilize this strategy (Table II). Picornaviruses are nonenveloped viruses with a single positive strand (sense) RNA genome. After being internalized into cells by receptor-mediated endocytosis, human rhinovirus type 2 (HRV2), a picornaviridae, becomes entrapped in early endosomes (106). During a structural modification of the capsid in a low pH compartment, HRV2 loses its innermost capsid protein, VP4, followed by exposure of the amphiphilic N terminus of VP1 (108). The VP1 peptide is a key molecule that disrupts the endosomal membrane by pore formation to release their genome (109). This fact is supported by the observation that the release of 10-kDa biotin-dextran from endosomes is loaded with this peptide to a substantially higher degree than dextran of 70 kDa (109). It has been suggested that the viral capsid becomes hydrophobic due to exposure of the N terminus of VP1. The VP1 at the fivefold axis of symmetry is then inserted into the endosomal membrane resulting in pores of around 10 Å in diameter. These pores are presumably used by RNA for entry into the cytosol, but they are too small for 70-kDa dextran to pass through (109). Poliovirus is also a member of the Picornaviridae family that escapes from the endosome via pore formation, allowing the release of the RNA into the cytosol. Receptor binding of poliovirus promotes conformational rearrangements of the capsid that expose the N terminus of the capsid protein, VP1, and release the myristoylated autocleavage peptide, VP4, which has a clear role in the pore formation process. It was demonstrated that pores are formed when VP4 of wild-type poliovirus is inserted into the cellular membrane. In addition, in contrast to infection by wild-type viruses, 4028T.G mutant viruses are unable to induce cytoplasmic delivery of RNA (110,111). This mutant 4028T.G contains a glycine substitution at threonine-28 of VP4. Furthermore, analysis of these mutants with lipid bilayers demonstrates that they are unable to form pores to facilitate cytoplasmic delivery (110). Thus, the data suggest that VP4 sequences prominently contribute to the pore formation. Collectively, the key molecules involved in pore formation for endosomal escape of picornaviruses are different in that HRV2 and poliovirus use VP1 and VP4 as a key molecule, respectively.

Canine parvovirus (CPV), a member of the Parvoviridae family, induces pore formation to mediate the release single-stranded DNA with phospholipase A2 (PLA2) as a key molecule (112). This PLA2-like domain is found in the N terminus of VP1 (N-VP1), and its activity is triggered by an acidic environment. N-VP1 is internal in the parvovirus capsid and becomes exposed during endocytic entry of CPV. This PLA2-like domain is also found in the amino acid sequence of N-VP1 in several parvoviruses (113). CPV escapes from endosomes through pores, as demonstrated by cointernalization of small dextrans and the virus to detect changes in membrane permeability (112). When rhodamine-labeled dextrans (molecular weight (MW) 3,000 or 10,000) were coendocytosed with CPV, the MW 3,000 dextran translocated to the cytoplasm, whereas the MW 10,000 dextran was unable to escape from endosomal membranes in both the absence and presence of CPV (112). An earlier study also showed that the endosomal membrane retained alpha-sarcin when coendocytosed with CPV (28).

The size of the pore formed in the endosomal membrane of PLA2 is not known. However, some viruses of the Reoviridae family, such as reovirus and bursal disease, provide information about the size of the formed pores. Reovirus produces a myristoylated peptide—μ1N—that can induce size-selective membrane pores (114). The membrane-perforation activity of the virus assayed in vitro by lysis of red blood cell (RBC) membranes resulted in osmotic hemolysis of RBC membranes, after formation of small size-selective pores in the membrane. The pore formed by μ1N is approximately one tenth the diameter of the reovirus—in the range of 4–9 nm (114). In addition, bursal disease virus can disrupt cell membranes via pep46 (a 46-amino acid amphiphilic peptide) and its release from viruses is promoted by low calcium concentrations (115). Pep46 then induces pore formation in the endosomal membrane. Furthermore, the pore-forming domain of pep46 is located in the N terminus moiety (pep22) and the pore-formation process is associated with cis–trans-praline isomerization of peptides in the membranes. The formed pores visualized by electron cryomicroscopy were less than 10 nm in diameter (115). This observation suggests that release of the genome into the cytoplasm is sufficient after the virus is uncoated. It is also probable that, in addition to pore formation, the membrane undergoes additional degradation through physical (osmotic pressure) or biochemical (degradation enzymes) processes that mediate release of the viral genome.

Other viruses of the Reoviridae family that have similar molecular determinants of pore formation are bluetongue virus (BTV) and rotavirus. Bluetongue virus consists of two major structural proteins: VP2 (110 kDa) and VP5 (60 kDa). However, the peptide that causes membrane destabilization due to pore formation for core access to the cytoplasm is VP5 (116). After internalization of BTV into cells via clathrin-mediated endocytosis, VP2 is degraded and VP5 is left exposed in the endosomes. VP5 has two amphipathic helices in the coiled-coil domain that mediate insertion into the lipid membrane bilayer. In contrast to synthetic peptides that contain only hydrophobic residue, a more basic amphipathic synthetic peptide (aa 1 to 20) caused substantial release of lactate dehydrogenase. This result suggests that the basic amphipathic residue is important for interactions with membrane-penetrating peptides. Although the precise mechanism of membrane translocation remains unclear, it is probable that VP5 works synergistically with Mg+2 ions, as this ion causes the capsids to expand slightly around the fivefold pore axes. This expansion is followed by opening of the fivefold pore, which becomes an exit site for the viral genome, so that it can enter the cytoplasm (117). Another virus from the Reoviridae family that uses VP5 as a key molecule for genomic endosomal escape is rotavirus (118). Proteases cleave the rotavirus VP4 spike protein into VP5* fragments and trigger them to selectively permeabilize membranes. Interestingly, in contrast to other membrane-permeabilizing peptides, VP5* induction did not result in bacterial lysis, suggesting a pore-forming function for VP5* membrane interactions (118). Size selectivity of VP5* permeabilization was demonstrated in a study that VP5* permeabilized liposomes to 376-Da carboxyfluorescein but not to 4-kDa fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran. In addition, VP5* proteins permeabilize liposomes and cell membranes containing a hydrophobic domain (HD; residues 385 to 404). Permeability is abolished by both C-terminal truncations that remove a conserved GGA motif (residues 399 to 401) and by site-directed mutagenesis of the HD (118). Therefore, VP5* may play a role in endosomal escape via pore formation.

NUCLEAR DELIVERY

Nuclear Delivery of Adenovirus

After escaping to the cytosol, Ad traffics along microtubules toward the nucleus. Binding of Ad to microtubules is facilitated by interactions with dynein (119), a molecule that drives motility toward the microtubule organizing center (120). Ad then is disassembled in the cytoplasm with the aid of some cellular proteins to release the DNA genome before it translocates to the nucleoplasm, Firstly, the Ad docks to the nuclear pore complex (NPC) protein CAN/Nup214, which is located at cytoplasmic filaments (121). This Ad–NPC interaction recruits a series of disassembly factors to the cytoplasm such as the molecular chaperon Hsc70, the nuclear histone H1 and H1 import factors, importin β, and importin 7 into the cytosol (122). Basically, the nuclear histone H1 locates in the nucleus, but it leaves the nucleus and binds the Ad2 hexon protein at cytoplasmic filaments to facilitate the disassembly of the capsid of Ad. Hsc70 then triggers decoating of the capsid and release of DNA in which the DNA is exposed near the opening of the NPC to allow nuclear import (88). The translocation step of DNA from the cytoplasm to the nucleus remains to be poorly understood, and it is possible that the DNA might enter the nucleus by passive diffusion (88).

Nuclear Delivery of SV40

Simian virus 40, a nonenveloped DNA virus, was the first virus recognized for cellular uptake via caveolar endocytosis (123). After internalization, SV40 is entrapped in caveosomes, as evidenced by colocalization of SV40 with caveolin-1, a caveolae marker that is localized in the caveosomes (4). Trafficking of SV40 to the ER is microtubules dependent, as it is inhibited by nocodazole. After having moved along microtubules to the ER, SV40 was not observed in the cytosol or in the nucleus (Fig. 1; 4). Decoating of the SV40 capsid probably occurs in the ER and is mediated by chaperone activity. Molecular chaperones are involved in degradation of protein that transit through the ER (124). The decoating process results in dissociation of SV40 capsid proteins, VP1, VP2, and VP3. The key molecules for ER escape are VP2 and VP3. Immunostaining showed that VP2/3 was localized outside of the ER, while VP1 was colocalized in the ER even after 20 h (125). The question then is how VP2 and VP3 are transported across the ER membrane. Apparently, they escape via the pore-formation mechanism (126). It is doubtful that they escape via a detergent-like mechanism because lysis of the ER would result in cell death. VP2 and VP3 oligomerize to form pores, allowing the DNA genome to be released from the ER (127).

There are two routes for transport of DNA from the ER into the nucleus (Fig. 1). One possibility is that the DNA is delivered into the nucleus through the NPC after it is released from the ER into the cytoplasm (128). Alternatively, the genomic DNA might be transported directly from the ER to the nucleus across the inner nuclear membrane, since the ER and nuclear membranes are linked (127). As a result, this route would be an efficient way to deliver the SV40 DNA to the nucleus.

CONCLUSION

This article reviews the journey that viruses must complete to successfully infect their host; we describe internalization pathways and intracellular trafficking, including endosomal escape and nuclear delivery. Although mechanisms of viral uptake are not as diverse as their receptors, they provide information that is valuable for delivery of therapeutic agents. Viruses that enter via clathrin-mediated endocytosis provide information on mechanisms by which substances escape the endosome, which is a significant barrier to gene delivery. Several amphipathic peptides are introduced to mediate the escape of macromolecules, such as small interfering RNA, plasmid DNA, nucleic acids, and proteins. The caveolar endocytosis pathway can be used to deliver macromolecules to parenchymal cells, as macromolecules that are taken up by this pathway can traverse endothelial cells. In addition, trafficking of SV40 to the endoplasmic reticulum via the caveolar pathway demonstrates the possibility of direct nuclear import, although further investigation is still needed. This phenomenon suggests that novel organelle-targeted intracellular pathways of nuclear delivery are possible, as reported in the very recent studies. Sun and coworkers demonstrate that a derivative of an arginine peptide (R8), CALNNR8 peptide, is targeted either to the endoplasmic reticulum or to the nucleus (129). Collectively, complete understanding of intracellular trafficking of viruses may provide a rational design by which nonviral-gene delivery systems can be improved.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Core Research for Evolution of Science and Technology (CREST), Japan Science and Technology Corporation (JST). We also thank Dr. James L. McDonald for the helpful advice in writing the English manuscript.

References

- 1.Smith A. E., Helenius A. How viruses enter animal cells. Science. 2004;304:237–242. doi: 10.1126/science.1094823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson J. L., Hope T. J. Intracellular trafficking of retroviral vectors: obstacles and advances. Gene Ther. 2005;12:1667–1678. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimitrov D. S. Virus entry: molecular mechanisms and biomedical applications. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:109–122. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelkmans L., Kartenbeck J., Helenius A. Caveolar endocytosis of simian virus 40 reveals a new two-step vesicular-transport pathway to the ER. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:473–483. doi: 10.1038/35074539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marsh M., Helenius A. Virus entry: open sesame. Cell. 2006;124:729–740. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medina-Kauwe L. K. Endocytosis of adenovirus and adenovirus capsid proteins. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55:1485–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wickham T. J., Mathias P., Cheresh D. A., Nemerow G. R. Integrin alpha v beta 5 promote adenovirus internalization but not virus attachment. Cell. 1993;73:309–319. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90231-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnberg N., Kidd A. H., Edlund K., Wadell G. Adenovirus type 37 uses sialic acid as cellular receptor. J Virol. 2000;74:42–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernardes C., Antonio A., Pedroso de Lima M. C., Valdeira M. L. Cholesterol affects African swine fever virus infection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1393:19–25. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simmons G., Reeves J. D., Grogan C. C., Vandenberghe L. H., Baribaud F., Whitbeck J. C., Burke E., Buchmeier M. J., Soilleux E. J., Riley J. L., Doms R. W., Bates P., Pohlmann S. DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR bind ebola glycoproteins and enhance infection of macrophages and endothelial cells. Virol. 2003;305:115–123. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan S., Empig C., Welte F., Speck R., Schmaljohn A., Kreisberg J., Goldsmith M. Folate receptor alpha is a cofactor for cellular entry by Marburg and Ebola viruses. Cell. 2001;106:117–126. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00418-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartosch B., Cosset F. L. Cell entry of hepatitis C virus. Virol. 2006;348:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kroschewski H., Allison S. L., Heinz F. X., Mandl C. W. Role of heparan sulfate for attachment and entry of tick-borne encephalitis virus. Virol. 2003;308:92–100. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(02)00097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y., Maquire T., Hileman R. E., Fromm J. R., Esko J. D., Linhardt R. J., Marks R. M. Dengue virus infectivity depends on envelope protein binding to target cell heparin sulfate. Nat Med. 1997;3:866–871. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tassaneetrithep B., Burgess T. H., Granelli-Piperno A., Trumpfheller C., Finke J., Sun W., Eller M. A., Pattanapanyasat K., Sarasombath S., Birx D. L., Steinman R. M., Schlesinger S., Marovich M. A. DC-SIGN (CD209) mediates dengue virus infection of human dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197:823–829. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper A., Shaul Y. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis and lysosomal cleavage of hepatitis B virus capsid-like core particles. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16563–16569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601418200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Compton T., Nowlin D. M., Cooper N. R. Initiation of human cytomegalovirus infection requires initial interaction with cell surface heparin sulfate. Virol. 1993;193:834–841. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halary F., Amara A., Lortat-Jacob H., Messerle M., Delaunay T., Houles C., Fieschi F., Arenzana-Seisdedos F., Moreau J. F., Dechanet-Merville J. Human cytomegalovirus binding to DC-SIGN is required for dendritic cell infection and target cell trans-infection. Immunity. 2002;17:653–664. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00447-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki T., Takahashi T., Guo C. T., Hidari K. I., Miyamoto D., Goto H., Kawaoka Y., Suzuki Y. Sialidase activity of influenza A virus in an endocytic pathway enhances viral replication. J Virol. 2005;79:11705–11715. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.11705-11715.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drobni P., Mistry N., McMillan N., Evander M. Carboxy-fluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester labeled papillomavirus virus-like particles fluoresce after internalization and interact with heparan sulfate for binding and entry. Virol. 2003;310:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evander M., Frazer I. H., Payne E., Qi Y. M., Hengst K., McMillan N. A. Identification of the alpha6 integrin as a candidate receptor for papillomaviruses. J Virol. 1997;71:2449–24456. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2449-2456.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dugan A. S., Eash S., Atwood W. J. Update on BK virus entry and intracellular trafficking. Transpl Infect Dis. 2006;8:62–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2006.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Summerford C., Samulski R. Membrane-associated heparin sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2. J Virol. 1998;72:1438–1445. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1438-1445.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qing K., Mah C., Hansen J., Zhou S. Z., Dwarki V., Srivastava A. Human fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is a co-receptor for infection by adeno-associated virus 2. Nat Med. 1999;5:71–77. doi: 10.1038/4758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Summerford C., Bartlett J. S., Samulski R. J. AlphaVbeta5 integrin: a co-receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 infection. Nat Med. 1999;5:78–82. doi: 10.1038/4768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walters R. W., Yi S. M., Keshavjee S., Brown K. E., Welsh M. J., Chiorini J. A., Zabner J. Binding of adeno-associated virus type 5 to 2,3-linked sialic acid is required for gene transfer. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20610–20616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ros C., Burckhardt C. J., Kempf C. Cytoplasmic trafficking of minute virus of mice: low-pH requirement, routing to late endosomes, and proteasome interaction. J Virol. 2002;76:12634–12645. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12634-12645.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parker J. S., Parrish C. R. Cellular uptake and infection by canine parvovirus involves rapid dynamin-regulated clathrin-mediated endocytosis, followed by slower intracellular trafficking. J Virol. 2000;74:1919–1930. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1919-1930.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joki-Korpela P., Marjomaki V., Krogerus C., Heino J., Hyypia T. Entry of human parechovirus 1. J Virol. 2001;75:1958–1967. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.4.1958-1967.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joki-Korpela P., Hyypia T. Parechoviruses, a novel group of human picornaviruses. Ann Med. 2001;33:466–471. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hofer F., Gruenberger M., Kowalski H., Machat H., Huettinger M., Kuechler E. Members of the low density lipoprotein receptor family mediate cell entry of a minor-group common cold virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1839–1842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chou T. Stochastic entry of enveloped viruses: fusion versus endocytosis. Biophys J. 2007;93:1116–1123. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.106708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Husain M., Moss B. Role of receptor-mediated endocytosis in the formation of vaccinia virus extracellular enveloped particles. J Virol. 2005;79:4080–4089. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4080-4089.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barton E. S., Forrest J. C., Connolly J. L., Chappell J. D., Liu Y., Schnell F. J. Junction adhesion molecule is a receptor for reovirus. Cell. 2001;104:441–451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brojatsch J., Naughton J., Rolls M. M., Zingler K., Young J. A. CAR1, a TNF-related protein, is a cellular receptor for cytophatic avian leukosis–sarcoma viruses and mediates apoptosis. Cell. 1996;87:845–855. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81992-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griffero F. D., Hoschander S. A., Brojatsch J. Endocytosis is a critical step in entry of subgroup B avian leukosis viruses. J Virol. 2002;76:12866–12876. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12866-12876.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewis P., Fu Y., Lentz T. L. Rabies virus entry into endosomes in IMR-32 human neuroblastoma cells. Exp Neurol. 1998;153:65–73. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun X., Yau V. K., Briggs B. J., Whittaker G. R. Role of clathrin-mediated endocytosis during vesicular stomatitis virus entry into host cells. Virol. 2005;338:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Byrnes A. P., Griffin D. E. Binding of sindbis virus to cell surface heparan sulfate. J Virol. 1998;72:7349–7356. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7349-7356.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeTulleo L., Kirchhausen T. The clathrin endocytic pathway in viral infection. EMBO J. 1998;17:4585–4593. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Helenius A., Morein B., Fries E., Simons K., Robinson P., Schirrmacher V., Terhorst C., Strominger J. L. Human (HLA-A and HLA-B) and Murine (H-2K and H-2D) histocompatibility antigens are cell surface receptors for semliki forest virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:3846–3450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kee S. H., Cho E. J., Song J. W., Park K. S., Baek L. J., Song K. J. Effects of endocytosis inhibitory drugs on rubella virus entry into VeroE6 cells. Microbiol Immunol. 2004;48:823–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2004.tb03614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mastromarino P., Cioe L., Rieti S., Orsi N. Role of membrane phospholipids and glycolipids in the Vero cell surface receptor for rubella virus. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1990;179:105–114. doi: 10.1007/BF00198531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bousarghin L., Touze A., Sizaret P. Y., Coursaget P. Human papillomavirus type 16, 31 and 58 use different endocytosis pathways to enter cells. J Virol. 2003;77:3846–3850. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.6.3846-3850.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Connaris H., Takimoto T., Russell R., Crennell S., Moustafa I., Portner A., Taylor G. Probing the sialic acid binding site of the hemagglutinin-neuraminidase of Newcastle disease virus: identification of key amino acids involved in cell binding, catalysis, and fusion. J Virol. 2000;76:1068–1074. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.4.1816-1824.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cantin C., Holguera J., Ferreira L., Villar E., Munoz-Barroso I. Newcastle disease virus may enter cells by caveolae-mediated endocytosis. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:559–569. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Werling D., Hope J. C., Chaplin P., Collins R. A., Taylor G., Howard C. J. Involvement of caveolae in the uptake of respiratory syncytial virus antigen by dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:50–58. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Y., Bergelson J. M. Adenovirus receptors. J Virol. 2005;79:12125–12131. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.19.12125-12131.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shieh J. T., Bergelson J. M. Interaction with decay-accelerating factor facilitates coxsackievirus B infection of polarized epithelial cells. J Virol. 2002;76:9474–9480. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.18.9474-9480.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marjomaki V., Pietiainen V., Matilainen H., Upla P., Ivaska J., Nissinen L., Reunanen H., Huttunen P., Hyypia T., Heino J. Internalization of echovirus 1 in caveolae. J Virol. 2002;76:1856–1865. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.4.1856-1865.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richterova Z., Liebl D., Horak M., Palkova Z., Stokrova J., Hozak P., Korb J., Forstova J. Caveolae are involved in the trafficking of mouse polyoma virus virions and artificial VP1 pseudocapsids toward cell nuclei. J Virol. 2001;75:10880–10891. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10880-10891.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spear P. G., Eisenberg R. J., Cohen G. H. Three classes of cell surface receptors for alphaherpes virus entry. Virol. 2000;275:1–8. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fingeroth J. D., Weiss J. J., Tedder T. F., Strominger J. L., Biro P. A., Fearon D. T. Epstein–Barr virus receptor on human B lymphocytes is the complement receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:4510–4514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.14.4510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nemerow G. R., Wolfert R., McNaughton M., Cooper N. R. Identification and characterization of the Epstein–Barr virus receptor on human B lymphocytes and its relationship to the C3d complement receptor (CR2) J Virol. 1985;55:347–351. doi: 10.1128/jvi.55.2.347-351.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bose E., Banerjee A. K. Role of heparan sulfate in human parainfluenza virus type 3 infection. Virol. 2002;298:73–83. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lamb R. A. Paramyxovirus fusion: a hypothesis for changes. Virol. 1993;197:1–11. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tahara M., Takeda M., Yanagi Y. Altered interaction of the matrix protein with the cytoplasmic tail of hemagglutinin modulates measles virus growth by affecting virus assembly and cell–cell fusion. J Virol. 2007;81:6827–6836. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00248-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ghosh J. K., Peisajovich S. G., Ovadia M., Shai Y. Structure-function study of a heptad repeat positioned near the transmembrane domain of Sendai virus fusion protein which blocks virus-cell fusion. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27182–27190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ren G., Wang Z., Hu X. Effects of ectodomain sequences between HR1 and HR2 of F1 protein on the specific membrane fusion in paramyxoviruses. Intervirol. 2007;50:115–122. doi: 10.1159/000098237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li P., McL Rixon H. W., Brown G., Sugrue R. J. Functional analysis of the N-linked glycans within the fusion protein of respiratory syncytial virus. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;379:69–83. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-393-6_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berger E. A., Murphy P. M., Farber J. M. Chemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors: roles in viral entry, tropism and disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:657–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bae E. H., Park S. H., Jung Y. T. Role of a third extracellular domain of an ecotropic receptor in moloney murine leukemia virus infection. J Microbiol. 2006;44:447–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cao W., Henry M. D., Borrow P., Yamada H., Eldor J. H., Ravkov E. V., Nichol S. T., Compans R. W., Campbell K. P., Oldstone M. B. Identification of alfa-dystroglycan as a receptor for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus and lassa fever virus. Science. 1998;282:2079–2081. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Borrow P., Oldstone M. B. Mechanism of lyphocytic choriomeningitis virus entry into cells. Virology. 1994;198:1–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meier O., Boucke K., Hammer S. V., Keller S., Stidwill R. P., Hemmi S., Greber U. F. Adenovirus triggers macropinocytosis and endosomal leakage together with its clathrin-mediated uptake. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:1119–1131. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sieczkarski S. B., Whittaker G. R. Influenza virus can enter and infect cells in the absence of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J Virol. 2002;76:10455–64. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10455-10464.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hogle J. M. Poliovirus cell entry: common structural themes in viral cell entry pathways. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2002;56:677–702. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.160757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Greve J. M., Davis G., Meyer A. M., Forte C. P., Yost S. C., Marlor C. W. The major human rhinovirus receptor is ICAM-1. Cell. 1989;56:834–849. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90688-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Prechla E., Plank C., Wagner E., Blaas D., Fuchs R. Virus-mediated release of endosomal content in vitro: different behaviour of adenovirus and rhinovirus serotype 2. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:111–123. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stuart A. D., Eustace H. E., McKee T. A., Brown T. D. A novel cell entry pathway for a DAF-using human enterovirus is dependent on lipid rafts. J Virol. 2002;76:9307–9322. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.18.9307-9322.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guerrero C. A., Zarate S., Corkidi G., Lopez S., Arias C. F. Biochemical characterization of rotavirus receptors in MA104 cells. J Virol. 2000;74:9362–9371. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.20.9362-9371.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chemello M. E., Aristimuno O. C., Michelangeli F., Ruiz M. C. Requirement for vacuolar H+-ATPase activity and Ca2+ gradient during entry of rotavirus into MA104 cells. J Virol. 2002;76:13083–13087. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.13083-13087.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sanchez-San Martin C., Lopez T., Arias C. F., Lopez S. Characterization of rotavirus cell entry. J Virol. 2004;78:2310–2318. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2310-2318.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Greber U. F. Signalling in viral entry. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:608–626. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8453-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pelkmans L., Fava E., Grabner H., Hannus M., Habermann B., Krauz E., Zerial M. Genome-wide analysis of human kinases in clathrin- and caveolae/raft-mediated endocytosis. Nature. 2005;436:78–86. doi: 10.1038/nature03571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maxfield F. R., McGraw T. E. Endocytic recycling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:121–132. doi: 10.1038/nrm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schnitzer J. E. Caveolae: from basic trafficking mechanism to targeting transcytosis for tissue-specific drug and gene delivery in vivo. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;49:265–280. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rejman J., Oberle V., Zuhorn I. S., Hoekstra D. Size-dependent internalization of particles via pathways of clathrin- and caveolae-mediated endocytosis. Biochem. 2004;377:159–169. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pelkmans L., Helenius A. Endocytosis via caveolae. Traffic. 2002;3:311–320. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.30501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shaul P. W., Anderson R. G. W. Role of plasmalemmal caveolae in signal transduction. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L843–L851. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.5.L843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tuma P. L., Hubbard A. L. Transcytosis: crossing cellular barriers. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:871–932. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bomsel M., Alfsen A. Entry of viruses through the epithelial barrier: pathogenic trickery. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:57–68. doi: 10.1038/nrm1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ouzilou L., Caliot E., Pelletier I., Prevost M.-C., Pringault E., Colbere-Garapin F. Poliovirus transcytosis through M-like cells. J General Virol. 2002;83:2177–2182. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-9-2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bomsel M. Transcytosis of infectious human immunodeficiency virus across a tight human epithelial cell line barrier. Nat Med. 1997;3:42–47. doi: 10.1038/nm0197-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pesonen M., Ansorge W., Simons K. Transcytosis of the G protein of vesicular stomatitis virus after implantation into the apical plasma membrane of Madin–Darby canine kidney cells I. Involvement of endosomes and lysosomes. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:796–802. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.3.796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pesonen M., Bravo R., Simons K. Transcytosis of the G protein of vesicular stomatitis virus after implantation into the apical membrane of Madin–Darby canine kidney cells II. Involvement of the Golgi complex. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:803–809. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.3.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schnitzer J. E., Oh P. Albondin-mediated capillary permeability to albumin. Differential role of receptors in endothelial transcytosis and endocytosis of native and modified albumins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6072–6082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Meier O., Greber U. F. Adenovirus endocytosis. J Gene Med. 2004;6:S152–S163. doi: 10.1002/jgm.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kielian M., Rey F. A. Virus membrane-fusion proteins: more than one way to make a hairpin. Nat Rev. 2006;4:67–76. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Skehel J. J., Wiley D. C. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:531–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Garten W., Hallenberger S., Ortmann D., Schafer W., Vey M., Angliker H., Shaw E., Klenk H. D. Processing of viral glycoproteins by the substilin-like endoprotease furin and its inhibition by specific peptidylchloroalkylketones. Biochimie. 1994;76:217–225. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(94)90149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Adam B., Lins L., Stroobant V., Thomas A., Brasseur R. Distribution of hydrophobic residues is crucial for the fusogenic properties of the Ebola virus GP2 fusion peptide. J Virol. 2004;78:2131–2136. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.2131-2136.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li X., McDermott B., Yuan B., Goff S. P. Homomeric interactions between transmembrane proteins of Moloney murine leukemia virus. J Virol. 1996;70:1266–1270. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1266-1270.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bosch B. J., Van der Zee R., de Haan C. A., Rottier P. J. The coronavirus spike protein is a class I virus fusion protein: structural and functional characterization of the fusion core complex. J Virol. 2003;77:8801–8811. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8801-8811.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rey F. A., Heinz F. X., Mandl C., Kunz C., Harrison S. C. The envelope glycoprotein from tick-borne encephalitis virus at 2 Å resolution. Nature. 1995;375:291–298. doi: 10.1038/375291a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lescar J., Roussel A., Wien M. W., Navaza J., Fuller S. D., Wrengler G., Rey F. A. The fusion glycoprotein shell of Semliki Forest virus: an isocahedral assembly primed for fusogenic activation at endosomal pH. Cell. 2001;205:237–148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Oren Z., Shai Y. Mode of action of linear amphipathic α-helical antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers. 1998;47:451–463. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1998)47:6<451::AID-BIP4>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shai Y. Mechanism of the binding, insertion and destabilization of phospholipids bilayer membranes by α-helical antimicrobial and cell non-selective membrane-lytic peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1462:55–70. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00200-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pouny Y., Rapaport D., Mor A., Nicolas P., Shai Y. Interaction of antimicrobial dermaseptin and its fluorescently labeled analogs with phospholipids membranes. Biochemistry. 1992;31:12416–12423. doi: 10.1021/bi00164a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hinz A., Galla H. J. Viral membrane penetration: lytic activity of nonviral fusion peptide. Eur Biophys J. 2005;34:285–293. doi: 10.1007/s00249-004-0450-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Seth P. Adenovirus-dependent release of choline from plasma membrane vesicles at an acidic pH is mediated by the penton base protein. J Virol. 1994;68:1204–1206. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.1204-1206.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wiethoff C. M., Wodrich H., Gerace L., Nemerow G. R. Adenovirus protein VI mediates membrane disruption following capsid disassembly. J Virol. 2005;79:1992–2000. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.1992-2000.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Miyazawa N., Crystal R. G., Leopold P. L. Adenovirus serotype 7 retention in a late endosomal compartment prior to cytosol escape is modulated by fiber protein. J Virol. 2001;75:1387–1400. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.3.1387-1400.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang F., Andreassen P., Fender P., Geissier E., Hernandez J. F., Chroboczek J. A transfecting peptide derived from adenovirus fiber protein. Gene Ther. 1999;6:171–181. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kamper N., Day P. M., Nowak T., Selinka H. C., Florin L., Bolscher J., Hilbig L., Schiller J. T., Sapp M. A membrane-destabilizing peptide in capsid protein L2 is required for egress of papillomavirus genomes from endosomes. J Virol. 2006;80:759–768. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.759-768.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Schober D., Kronenberger P., Prchla E., Blaas D., Fuchs R. Major and minor receptor group human rhinoviruses penetrate from endosomes by different mechanisms. J Virol. 1998;72:1354–1364. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1354-1364.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]