Abstract

Background

Racial disparities persist in prostate cancer (CaP) treatment and survival, but disparities in androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), and to what degree it affects racial differences in survival remains to be fully assessed.

Methods

Using the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results-Medicare linked data, we examined a large cohort of men (n=64,475) diagnosed with locoregional CaP during 1992 to 1999 and followed through 2003. The effects of ADT and race on survival were analyzed using Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

The receipt of ADT was significantly lower in African Americans (AA), (24%) relative to Caucasians (27%), Asians (34%), and Hispanics (28.7%), p < 0.05. Compared with Caucasians, AA race was associated with a statistically significant increased mortality, Hazard Ratio (HR) = 1.26; 95% CI = 1.21−1.32, which remained significant after adjusting for ADT, but was substantially decreased after controlling for primary therapies (radical prostatectomy, radiation, watchful waiting) (HR = 1.06; 1.01 − 1.10), and was no longer statistically significant after controlling for comorbidities (HR = 0.98; 0.94 −1.03).

Conclusions

There were marked racial variations in the receipt of ADT, primary therapies namely surgery and surgery combined with radiation, and comorbidities. However, racial disparities in survival were not affected by racial variations in ADT, but were explained by racial variations in primary therapies, and by racial differences in comorbidities.

Keywords: prostate neoplasm, race, androgen deprivation therapy, survival, comorbidity

Introduction

Substantial racial differences persist in prostate cancer incidence and mortality in the United States; and the incidence rate among African American males is reported to be the highest in the world.1-4 While AAs have a 60% increased risk of developing CaP, twice the risk of developing distant disease and twofold the mortality relative to Caucasians, 5-7 incidence and mortality for Hispanics are lower than those for Caucasians.5 The higher mortality among AAs has been associated with less aggressive treatment compared to Caucasians, 8 advanced–stage prostate cancer at presentation, 9 and biologically aggressive tumor in AAs.10 The younger age at presentation of CaP in AAs compared with Caucasians is indicative of higher tumor stage and grade, and more aggressive tumor, implying potential biologic variation in prostate cancer presentation between these racial/ethnic groups.11-14

Radical prostatectomy (RP), external beam radiation (XRT) or RP plus salvage XRT, also termed aggressive therapies are considered as the two major therapeutic options for treating clinically localized prostate cancer.15 Conservative management is the use of orchiectomy and or primary androgen deprivation therapy (PADT) mainly luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist or no therapy (watchful waiting) within six months of diagnosis. Data are conflicting on the variation in treatment received in explaining racial disparities in CaP mortality and for the survival disadvantage of AAs.15 Several socioeconomic and behavioral differences are believed to explain at least part of the higher CaP incidence and mortality rates observed in AAs. Some studies have attributed this disparity to differences in socio-economic status, 16-19 advanced stage at diagnosis, 7,5,9,20,21 and treatment received.22

Disparities in primary therapies (PT) have been observed, with AAs less likely to undergo radical prostatectomy. Most studies have focused on primary therapies in explaining racial differences in CaP mortality between AAs and Caucasians. This study is unique in that it aimed to assess racial disparities in ADT and its impact on racial differences in survival. We conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study using time-independent covariates in Cox proportional hazards model and presented the overall survival of AAs compared with Caucasians, Asians and Hispanics and the covariates contributing to these variations besides ADT.

Method

Data source

After appropriate approval from the relevant institutional review boards, we conducted a retrospective cohort study using the merged SEER-Medicare database for men diagnosed with locoregional CaP at age 65 and older between 1992 and 1999 in the eleven SEER areas, which accounts for 14% of the US population. The SEER areas comprise the metropolitan areas of San Francisco/Oakland, Detroit, Atlanta, and Seattle; Los Angeles county, the San Jose-Monterey area; and the states of Connecticut, Iowa, New Mexico, Utah, and Hawaii.

Study population

Patients diagnosed with prostate cancer at age 65 and older from 1992 to 1999 in eleven SEER regions were selected, who had both Medicare part A and B and were not members of the Health Maintenance Organizations (HMO). Because SEER provides a combined category for CaP staging for regional and local tumor, tumor staging (I-IV) was used to control for residual confounding by the combined local/regional stages. All races were included in the study population: Caucasians (n=53,764), African Americans (n=6,321), Hispanics (n=1,143), Asians (n=1,830), and others (n=1,417).

Study variables

Outcome variable

All-cause mortality was defined as death from any cause reported as the underlying cause of death. The survival time in months was calculated from the month of diagnosis to the month of death or to the date of last follow-up.

Androgen deprivation therapy

Hormonal or androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) was described as the receipt of luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist or orchiectomy. Patients were characterized as receiving ADT if any of the following Medicare procedure codes indicated so within six months of diagnosis: procedure codes for leuprolide (J1950 or J9217-J9219) and for goserelin (J9202) or procedure codes for orchiectomy (54520 −5421,54530 or 54535). Orchiectomy was defined as surgical castration for the purpose of suppressing testicular testosterone.

Chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation

Chemotherapy was defined as having received chemotherapy if the Medicare Procedure indicated so within six months of diagnosis. Chemotherapy was reported as either received or not received. The details of chemotherapy ascertainment have been described elsewhere.16,61-63 The primary therapies in localized CaP include radical prostatectomy, radiotherapy, or observational management as watchful waiting (WW), which has been reported eslewhere.16, 63

Comorbidity

Comorbidity was ascertained from Medicare claims using diagnoses and procedure performed between one year prior to, and one month after prostate cancer diagnosis.16 The detail on the Comorbidity index has been previously described. 64 Comorbidity scores were categorized into four groups (0, 1, 2, 3 and higher).

Demographics

Race and Age: Race was classified by using data from the SEER and categorized as Caucasian, AA, Hispanics, Asians and others. The age at diagnosis was recoded and categorized into 65−69, 70−74, 75−79 and 80 or older. Marital status was classified as married, unmarried and unknown when information was unavailable.

Socioeconomic status proxies

Three variables from the 1990 census are available in the SEER-Medicare linked data, which was used to define SES, namely: I) education – percent adults aged ≥ 25 years of education at the zip code level, II) poverty – percent of persons living below the poverty line at the census tract level and III) income – median annual household income at the zip code level. Poverty was used at the census tract level since this data is not available at the zip code level. The three variables were categorized into quartiles and when information were unavailable, we described this as unknown category.16 For education and income, the first quartile represents the highest education attainment and economic status respectively.

Clinical features and other characteristics

This data represents locoregional prostate cancer. SEER defines localized disease as an invasive neoplasm confined entirely to organ of origin, while regional disease refers to a neoplasm that has extended beyond the limits of the organ of origin directly into surrounding organs or tissues. Prostate cancer data from SEER are available as loco-regional and distant or metastasis. Both grade and tumor stage (I, II, III, IV, or unknown) categories were used in adjusting for confounding. The Gleason score ranges from 2−10, with 10 implying worst prognosis. A Gleason score of 2−4 represents slow growing tumor, 5−7, moderately aggressive, while a score of 8−10 represents high chance of tumor spread. The staging of prostate cancer involves stage 1-IV classification, with stage IV representing the worst prognosis. Stage I represents early cancer confined to microscopic area, stage II refers to palpable tumor confined to prostate gland, and stage III represents tumor with possible spread to seminal vesicles, while stage IV refers to spread to lymph node, bones, lungs or other areas. Geographic area is available in the SEER, and represented the eleven SEER areas in the dataset used for this study.

Statistical analyses

Pearson Chi square statistic was used to examine the association between race and ADT and the distribution of other socio-demographic (age, education, income, marital status, poverty) and clinico-pathologic parameters (tumor stage, Gleason score, radiation, chemotherapy, comorbidity score, year of diagnosis, and geographic area). Time to event data were analyzed using log-rank tests, Kaplan-Meier method, and Cox proportional hazard regression model. The overall survival was estimated using Kaplan Meier product limit by race/ethnicity. Univariable log-rank test were used to test the association between various clinico-pathologic characteristics and CaP survival. The proportionality assumption was satisfied when the log-log Kaplan-Meier curves for survival functions by HT and race were parallel and did not intersect.32 Multivariable analyses based on Cox Proportional Hazards regression model was used to examine the effect of the various covariates on the risk of dying by race. This model generates the hazard rate as function of the baseline hazard (ho) at time (t), and the effect of one or more independent variables (x1 x2 x3 ....xn). Interactions between race and ADT, and ADT and primary therapies were tested using the product terms of these covariates for inclusion in the model building. The interaction terms were allowed in the model if < 0.10 significance level. Further, analyses were adjusted for socio-demographics, tumor characteristics, ADT, chemotherapy primary therapies received, and comorbidities. Finally, we tested the model with and without interaction using likelihood ratio test for model fitness, and presented the results of the model without interaction. Statistical tests were two-sided at 0.05 significance level. All analyses were performed using STATA Statistical package, version 10.0. (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX)

Results

This analysis includes a total of 64,475 cases, with 17,415 (27%) receiving androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). Table 1 presents the comparison of socio-demographics, tumor characteristics and prognostic factors among different racial/ethnic groups in older men diagnosed with locoregional prostate cancer from 1992 through 1999 and followed till December 2003. Compared with Caucasian, African Americans (AAs) were more likely to be diagnosed with locoregional disease at younger age (28.7% versus 33.3%, χ2 (12) = 241.6, p < 0.001), less likely to be married at the time of diagnosis (55.7% versus 74.0%, χ2 (8) = 1200, p < 0.001), and disproportionately represented in the lowest quartile of the education level (26.8% versus 3.7% respectively, p < 0.001). Table 1 also presents the comorbidity index, Gleason score, tumor stage and ADT by race. Relative to Caucasians, African Americans were more likely to present with higher comorbidity index (9.0% versus 4.6%, p < 0.001), slightly less likely to be diagnosed with low Gleason score, (11.7% versus 13.9%, p < 0.001), and slightly less likely to receive chemotherapy alone (15.4% versus 17.8%, p < 0.001). In addition, compared with Caucasians, African Americans were less likely to receive ADT alone (27% versus 24%) whereas Hispanics (27% versus 28.2%) and Asians (27% versus 34.2%) were more likely to receive ADT alone, p < 0.001.

Table 1.

Study size and comparison of demographics, treatment and prognostic factors among different ethnic/racial groups in older men with local/regional prostate cancer

| Variable |

Race/Ethnicity (Number and Percentage) |

P value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasian | African American | Hispanics | Asians | Others | ||

| Overall | 53,764 (83.4) | 6,321(9.8) | 1,143 (1.8) | 1,830 (2.8) | 1,417(2.2) | |

| 64,475 (100) | ||||||

| Age (years) | < 0.001 | |||||

| 65−69 | 15,416 (28.7) | 2,131(33.7) | 411 (36.0) | 447 (24.4) | 354 (25.0) | |

| 70−74 | 17,324 (32.2) | 2,023 (32.0) | 390 (34.1) | 613 (33.5) | 390 (27.5) | |

| 75−79 | 12,271 (22.8) | 1,314 (20.8) | 221 (19.3) | 449 (24.5) | 319 (22.5) | |

| ≥ 80 | 8,753 (16.3) | 853 (13.5) | 121 (10.6) | 321 (17.5) | 354 (25.0) | |

| Comorbidity | < 0.001 | |||||

| 0 | 34,402 (64.0) | 3,394 (53.7) | 669 (58.5) | 1,097 (59.9) | 846 (59.7) | |

| 1 | 12,565 (23.4) | 1,611 (25.5) | 290 (25.4) | 465 (25.4) | 328 (23.1) | |

| 2 | 4,342 (8.1) | 747 (11.8) | 96 (8.4) | 164 (9.0) | 135 (9.5) | |

| ≥3 | 2,455 (4.6) | 569 (9.0) | 88 (7.7) | 104 (5.7) | 108 (7.6) | |

| Education | < 0.001 | |||||

| 1st | 14,437 (26.8) | 237 (3.7) | 60 (5.2) | 328 (17.9) | 228 (16.1) | |

| 2nd | 14,059 (26.1) | 472 (7.5) | 122 (10.7) | 300 (16.4) | 262 (18.5) | |

| 3rd | 13,034 (24.2) | 1,168 (18.5) | 225 (19.7) | 487 (26.6) | 360 (25.4) | |

| 4th | 9,193 (17.1) | 4,260 (67.4) | 666 (58.3) | 667 (36.4) | 493 (34.8) | |

| Unknown | 3,041 (5.7) | 184 (2.9) | 70 (6.1) | 48 (2.6) | 74 (5.2) | |

| Gleason sore | < 0.001 | |||||

| 2−4 | 7,475 (13.9) | 740 (11.71) | 198 (17.3) | 282 (15.4) | 224 (15.8) | |

| 5−7 | 33,218 (61.8) | 3,789 (59.9) | 650 (56.9) | 998 (54.5) | 733 (51.7) | |

| 8−10 | 10,438 (19.4) | 1,410 (22.3) | 240 (21.0) | 492 (26.9) | 337 (26.6) | |

| Unknown | 2,633 (4.9) | 382 (6.0) | 55 (4.8) | 58 (3.2) | 88 (5.9) | |

| Marital status | < 0.001 | |||||

| Married | 39,765 (74.0) | 3,522 (55.7) | 778 (68.1) | 1,459 (79.7) | 1,039 (73.2) | |

| Unmarried | 9,963 (18.5) | 2,267(35.9) | 295 (25.8) | 255 (13.9) | 276 (19.5) | |

| Unknown | 4,036 (7.5) | 532 (8.4) | 70 (6.1) | 116 (6.3) | 102 (7.2) | |

| ADT | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 39,266 (73.0) | 4,808 (76.0) | 815 (71.3) | 1,204 (65.8) | 967 (68.2) | |

| Yes | 14,498 (27.0) | 1,513 (24.0) | 328 (28.7) | 626 (34.2) | 450 (31.8) | |

| Chemotherapy | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 44,219 (82.2) | 5,345 (84.6) | 861 (75.3) | 1,345 (73.5) | 1,109 (78.3) | |

| Yes | 9,545 (17.8) | 976 (15.4) | 282 (24.7) | 485 (26.5) | 308 (21.7) | |

| Primary therapy | < 0.001 | |||||

| RP | 12,907 (24.0) | 1,070 (16.9) | 328 (28.7) | 411 (22.5) | 273 (19.3) | |

| XRT | 20,536 (38.2) | 2,463 (39.0) | 327 (28.6) | 695 (38.0) | 481 (33.9) | |

| RP plus XRT | 1,205 (2.2) | 89 (1.4) | 26 (2.3) | 57 (3.1) | 31 (2.2) | |

| Neither RP nor XRT | 19,116 (35.6) | 2,699 (42.7) | 462 (40.4) | 667 (36.4) | 632 (44.6) | |

| Tumor Stage | < 0.001 | |||||

| I | 17,636 (32.8) | 2,263 (35.8) | 387 (33.9) | 596 (32.6) | 435 (30.7) | |

| II | 6,701 (12.5) | 866 (13.7) | 147 (12.9) | 247 (13.5) | 180 (12.7) | |

| III | 7,717 (14.3) | 681 (10.8) | 173 (15.1) | 255 (14.0) | 215 (15.2) | |

| IV | 1,733 (3.2) | 212(3.3) | 48 (4.2) | 62 (3.4) | 61 (4.3) | |

| Unknown | 19,977(37.2) | 2,299 (36.4) | 388 (34.0) | 670 (36.6) | 526 (37.1) | |

Notes and abbreviations: P value for Chi square on racial/ethnic difference in the distribution of study characteristics. The first quartile represents highest education status. Radical prostatectomy=RP, Radiation=XRT

Note and abbreviations: P value for Chi square on racial/ethnic difference in the distribution of study characteristics. Radical prostatectomy=RP, Radiation=XRT, ADT=Androgen deprivation therapy.

Table 2 presents the comparison of treatments received among different ethnic/racial groups. The receipt of primary therapies and chemotherapy were statistically significantly different by race, p < 0.001. Compared with Caucasians, African Americans were less likely to receive radical prostatectomy (87% versus 85.8%), more likely to receive radical prostatectomy plus ADT (13% versus 14.2%), less likely to receive radiation plus ADT (28.5% versus 21.8%), more likely to receive radiation therapy alone (71.5% versus 78.2%), and were more likely to undergo watchful waiting or observational management alone (64.7% versus 70.4%), p < 0.001.

Table 2.

The comparison of treatment received among different ethnic/racial groups in older men with loco-regional prostate cancer

| Treatment |

Race/Ethnicity (number and percentage) |

P value* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasian (n=53,764) | African American (n=6,321) | Hispanic (n=1,143) | Asian (n=1,830) | Other (n=1,417) | ||

| Radical prostatectomy (RP) | < 0.001 | |||||

| RP plusADT | 1,674 (13.0) | 152 (14.2) | 51 (15.5) | 86 (20.9) | 55 (20.1) | |

| RP alone | 11,233 (87.0) | 918 (85.8) | 277 (84.5) | 325 (79.1) | 218 (79.9) | |

| Radiation therapy (XRT) | < 0.001 | |||||

| XRT plus ADT | 5,846 (28.5) | 536 (21.8) | 114 (34.9) | 261 (37.5) | 141 (29.3) | |

| XRT alone | 14,690 (71.5) | 1,927 (78.2) | 213 (65.1) | 434 (62.5) | 340 (70.7) | |

| RP & XRT | 0.008 | |||||

| RP/XRT plus ADT | 234 (19.4) | 27 (30.3) | 7 (26.9) | 15 (26.3) | 12 (38.7) | |

| RP/XRT alone | 971 (80.6) | 62 (69.7) | 19 (73.1) | 42 (73.7) | 19 (61.3) | |

| Watchful waiting (WW) | < 0.001 | |||||

| WW plus ADT | 6,744 (35.3) | 798 (29.6) | 156 (33.8) | 264 (39.6) | 242 (38.3) | |

| WW alone | 12,372 (64.7) | 1,901 (70.4) | 306 (66.2) | 403 (60.4) | 390 (61.7) | |

| Chemotherapy | < 0.001 | |||||

| Chemotherapy plus ADT | 8,497 (89.0) | 876 (89.7) | 247 (87.6) | 436 (95.5) | 286 (92.9) | |

| Chemotherapy alone | 1,048 (11.0) | 100 (10.2) | 35(12.4) | 22 (4.5) | 22 (7.1) | |

Note and abbreviations: p value for the chi square on ethnic differences in the distribution of primary therapies and chemotherapy. ADT = androgen deprivation therapy

Table 3 presents the univariable and multivariable Proportional Hazard model of the covariates influencing the survival of older men diagnosed with locoregional prostate cancer, and treated for the disease. In the unadjusted univariable regression, there was a statistically significant difference in the survival of African Americans, Hispanics, Asians and Caucasians, χ2 (3) = 206.6, (p < 0.001; log-rank). Compared with Caucasians, African Americans had a significant 26% increased risk of dying, HR=1.26, 95% CI, 1.21−1.32, (p < 0.001) whereas Hispanics and Asians had significant 17% and 28% decreased risk of dying, HR=0.83, 95% CI, 0.75−0.93, (p = 0.001), and HR=0.72, 95%CI, 0.66−0.79, (p < 0.001) respectively. Likewise, there was a significant difference in survival by those who received ADT compared to those who did not, χ2 (1) = 923.5, (p < 0.001; log-rank). Androgen deprivation therapy significantly increased the risk of dying, HR=1.55, 95% CI, 1.50−1.59, (p < 0.001). The younger age at diagnosis, early stage tumor, low Gleason score, marriage, higher income, lower comorbidity index, lower poverty level, higher education, radical prostatectomy (RP), radiation therapy (XRT), XRT and RP were significantly associated with survival advantage, p < 0.001. In contrast, chemotherapy and observational management, also termed watchful waiting were significantly associated with poorer survival, p < 0.001. Whereas XRT was associated with a significant 21% decreased risk of dying, HR = 0.79, 95% CI, 0.77 − 0.81, (p < 0.001), the use of XRT and RP was associated with a significant 47% decreased risk of dying in this cohort, HR = 0.53, 95% CI, 0.47− 0.59,( p < 0.001). In the multivariable Cox model, the impact of the covariates (socio-demographics, ADT, chemotherapy, primary therapies, and comorbidities) on the survival of this cohort persisted. However, the significant racial difference in survival between AAs and Caucasians was removed after controlling for these covariates, HR = 0.98, 95% CI, 0.94−1.03; p < 0.001.

Table 3.

The effects of covariates on survival of older men with locoregional prostate cancer in univariable and multivariable Cox Regression Model

| Covariates | Univariable Hazard Ratio (HR) , 95% Confidence Interval(CI) & Significance |

Multivariable Hazard Ratio (HR), 95% Confidence Interval (CI) & Significance |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Caucasian | 1.0 | Referent | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | Referent |

| African American | 1.26 | 1.21−1.32 | < 0.001 | 0.98 | 0.94−1.03 | 0.51 |

| Hispanic | 0.83 | 0.75−0.92 | 0.001 | 0.77 | 0.69−0.86 | < 0.001 |

| Asian | 0.72 | 0.66−0.79 | < 0.001 | 0.63 | 0.58−0.69 | < 0.001 |

| Age Group (years) | ||||||

| 65−69 | 1.0 | Referent | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | Referent |

| 70−74 | 1.48 | 1.42−1.54 | < 0.001 | 1.24 | 1.19−1.29 | < 0.001 |

| 75−79 | 2.60 | 2.50−2.70 | < 0.001 | 1.74 | 1.67−1.82 | < 0.001 |

| > 80 | 5.73 | 5.50−6.00 | < 0.001 | 2.98 | 2.85−3.12 | < 0.001 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 1.0 | Referent | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | Referent |

| Unmarried | 1.69 | 1.64−1.74 | < 0.001 | 1.29 | 1.25−1.33 | < 0.001 |

| Education | ||||||

| 1st | 1.0 | Referent | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | Referent |

| 2nd | 1.21 | 1.16−1.23 | < 0.001 | 1.07 | 1.03−1.12 | 0.001 |

| 3rd | 1.37 | 1.32−1.43 | < 0.001 | 1.09 | 1.04−1.13 | < 0.001 |

| 4th | 1.54 | 1.48−1.60 | < 0.001 | 1.08 | 1.03−1.14 | 0.001 |

| Income | ||||||

| 1st | 1.0 | Referent | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | Referent |

| 2nd | 1.17 | 1.12−1.21 | < 0.001 | 1.07 | 1.03−1.12 | 0.001 |

| 3rd | 1.28 | 1.23−1.33 | < 0.001 | 1.14 | 1.09−1.20 | < 0.001 |

| 4th | 1.47 | 1.42−1.53 | < 0.001 | 1.17 | 1.11−1.23 | < 0.001 |

| Poverty | ||||||

| 1st | 1.0 | Referent | Referent | --- | --- | --- |

| 2nd | 1.13 | 1.09−1.17 | < 0.001 | --- | --- | --- |

| 3rd | 1.23 | 1.18−1.28 | < 0.001 | --- | --- | --- |

| 4th | 1.50 | 1.44−1.55 | < 0.001 | --- | --- | --- |

| Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT) | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | Referent | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 1.55 | 1.50−1.59 | < 0.001 | 1.02 | 0.99−1.06 | 0.21 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | Referent | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 1.27 | 1.23−1.32 | < 0.001 | 1.00 | 0.96−1.05 | 0.90 |

| Radiation therapy (XRT) | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | Referent | Referent | --- | --- | --- |

| Yes | 0.79 | 0.77−0.81 | < 0.001 | --- | --- | --- |

| Radiation plus RP | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | Referent | Referent | --- | --- | --- |

| Yes | 0.53 | 0.47−0.59 | < 0.001 | --- | --- | --- |

| Watchful Waiting | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | Referent | Referent | --- | --- | --- |

| Yes | 2.93 | 2.86−3.01 | < 0.001 | --- | --- | --- |

| Primary Therapies | ||||||

| RP | 1.0 | Referent | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | Referent |

| Radiation | 2.41 | 2.30−2.52 | < 0.001 | 1.96 | 1.86−2.06 | < 0.001 |

| Radiation and RP | 1.48 | 1.32−1.66 | < 0.001 | 1.27 | 1.14−1.43 | < 0.001 |

| Watchful waiting | 5.27 | 5.04−5.51 | < 0.001 | 3.12 | 2.96−3.29 | < 0.001 |

| Radical Prostatectomy (RP) | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | Referent | Referent | --- | --- | --- |

| Yes | 0.28 | 0.27−0.29 | < 0.001 | --- | --- | --- |

| Gleason score | ||||||

| 2−4 | 1.0 | Referent | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | Referent |

| 5−7 | 0.87 | 0.84−0.91 | < 0.001 | 1.16 | 1.11−1.21 | < 0.001 |

| 8−10 | 1.49 | 1.42−1.55 | < 0.001 | 1.72 | 1.65−1.80 | < 0.001 |

| Tumor stage | ||||||

| I | 1.0 | Referent | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | Referent |

| II | 0.88 | 0.84−0.92 | < 0.001 | 1.15 | 1.10−1.21 | < 0.001 |

| III | 0.68 | 0.65−0.71 | < 0.001 | 1.26 | 1.20−1.32 | < 0.001 |

| IV | 1.33 | 1.25−1.42 | < 0.001 | 1.74 | 1.62−1.86 | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| 0 | 1.0 | Referent | Referent | 1.0 | Referent | Referent |

| 1 | 1.82 | 1.76−1.87 | < 0.001 | 1.59 | 1.54−1.64 | < 0.001 |

| 2 | 2.79 | 2.68−2.90 | < 0.001 | 2.19 | 2.10−2.28 | < 0.001 |

| > 3 | 4.66 | 4.45−4.88 | < 0.001 | 3.30 | 3.15−3.46 | < 0.001 |

Notes: The first quartile represents highest education status, highest income level, and lowest poverty level (high income level). The significance level, p < 0.05.

Notes and abbreviation: Lower Gleason score (2−3) correlates with better prognosis, while early stage at diagnosis (I) is associated with favorable outcome. The low comorbidity score (0) is associated with better prognosis. RP = Radical prostatectomy. The significance level, p < 0.05.

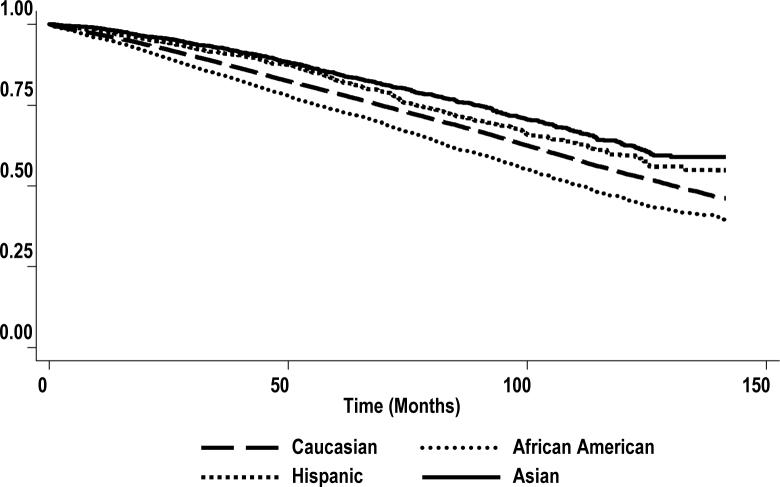

Table 4 presents a number of models used to assess the effect of ADT, primary therapies and other prognostic factors including education as socio-economic proxy on racial disparities in survival of older men treated for locoregional disease. The crude HR of dying was 26%, 52%, and 76% higher in AAs relative to Caucasians (HR =1.26, 95% CI = 1.21−1.32, p < 0.001), Hispanics (HR = 1.52, 95% CI = 1.36 −1.70, p < 0.001) and Asians (HR = 1.76, 95% CI = 1.60−1.94, p < 0.001). Model 2 adjusted for socio-demographics namely age at diagnosis, marital status, education and income. After controlling for these covariates, there was a significant 13% increased risk of mortality among AAs compared to Caucasians, HR =1.13, 95% CI, 1.08−1.18, (p < 0.001). Model 3 adjusted for all the covariates controlled in model 2 as well as tumor characteristics (tumor stage and Gleason score). There was a significant 11% increased risk of dying among AAs relative to Caucasians, HR = 1.11, 95% CI, 1.06−1.16, (p < 0.001). Model 4 adjusted for all the covariates controlled in model 3 plus ADT. There was a significant 12% increased risk of dying among AAs compared to Caucasians, HR = 1.12, 95% CI, 1.07−1.17, (p < 0.001). Model 5 controlled for all the covariates adjusted in model 4 as well as chemotherapy. There was no difference in the risk of dying in this model relative to the previous model (model 4). Model 6 controlled for the covariates adjusted in model 5 as well as primary therapies (surgery, radiation and watchful waiting). There was a significant 6% increased risk of dying among AAs compared to Caucasians, HR = 1.06, 95% CI, 1.01−1.10, (p < 0.001). Finally, model 7 adjusted for all the covariates controlled in previous models plus comorbidities. There was no significant different in mortality between AA and Caucasian men, (HR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.94−1.03), p = 0.51. The Kaplan-Meier survival function curve shows the survival advantage of both Hispanics and Asians compared with Caucasians or AAs (Figure I). This survival advantage persisted after adjustment for all the covariates (model 7). Thus compared with Caucasians, Hispanics and Asians had significant 23% and 37% decreased risks of dying (HR = 0.77; 0.69−0.86), p < 0.001 and (HR = 0.63; 0.58−0.69), p < 0.001 respectively.

Figure I. Kaplan-Meier survival estimate, by race/ethnicity.

Notes: The curves illustrate the overall survival disadvantage of African Americans compared with Caucasians, and the overall survival advantage of Asians compared with other ethnic/racial groups of older men diagnosed with locoregional prostate cancer and treated for the disease. The y axis presents the probability of survival as the survival function.

Discussion

There are a few relevant findings from this study: 1) There were substantial variations in the receipt of ADT alone and primary therapies (radical prostatectomy, radiation and observational management or watchful waiting) among different ethnic/racial groups. 2) Radical prostatectomy (RP) alone and combined XRT and RP significantly improved survival of older men treated for locoregional disease irrespective of race/ethnicity. 3) African Americans were less likely to receive ADT alone and RP alone, and more likely to receive observational management alone than Caucasians, whereas Hispanic and Asian men were more likely to receive ADT alone and RP alone. 4) African Americans were more likely to have higher comorbidity index, indicative of poor tumor prognosis. 5) Racial/ethnic disparities in survival were not affected by ADT alone, but were substantially reduced after adjusting for racial differences in primary therapies, and no longer persisted after controlling for cormorbidities.

This study clearly demonstrated racial/ethnic variance in the survival of older men diagnosed with prostate cancer, and treated for the disease. We examined the differences in ADT alone and other treatments for possible explanation of the persisted racial/ethnic differences in CaP mortality. Though a multi-race model, our main focus was on AAs because this ethnic/racial group has the highest incidence and mortality rates of CaP in United States. 1-4 Further, we considered a number of explanations for the racial differences in survival, and observed that ethnic/racial difference in all cause mortality in older men treated for locoregional prostate cancer is unexplained by racial variance in ADT, but largely by primary therapies mainly radical prostatectomy and comorbidities.

African Americans had more advanced stage disease at diagnosis as defined by the Gleason score and were less likely to receive aggressive therapy which has been shown to be associated with improved survival in previous studies.38,46,49,52,53,60 Although it is totally unclear why AAs received less aggressive therapy, it is possible that the selection of a particular therapy is driven by patients’ factors such as concerns about side effects of the treatment or bias among medical professionals not to recommend aggressive treatments for AAs.65,66 Therefore, it is plausible to assume that physicians may have empirically treated AAs as being more likely to have advanced-stage disease by withholding radical prostatectomy and offering either conservative management or radiation therapy.67,68

We have demonstrated a statistically significant difference in the receipt of ADT by race, with AAs less likely to receive ADT compared with Caucasians and other ethnic groups. We have also shown that ADT does not explain the survival differences observed between AAs and Caucasians. There are conflicting results on the role of androgen in prostate carcinogenesis 14, 37-40, 41-43, 44, 54, 55, 56 and therapeutics. Because CaP is heterogeneous, with hormone-sensitive and hormone-refractory subtypes, hormonal manipulation in CaP is not very clearly understood. Generally, androgen deprivation or rather maximum androgen blockade, competitively antagonize the androgen receptors and therefore block the action of androgens from any source. This action may result in the blockade of ligand-independent activation receptors.14,45 CaP is initially androgen dependent or sensitive and losses this sensitivity as the tumor progresses or after long term treatment with anti-androgens, thus becoming androgen-independent and incurable.45

Racial and ethnic disparities in CaP survival have been documented. 46,16,57-60 This variation has been associated with disparities in SES, 37 or socio-economic differences,16,25,57,59 response to chemotherapy45,47 and tumor stage.9,58,60 This study focused on ADT and other treatments received in explaining the observed racial/ethnic variation in this cohort. Our results indicate a 20% decreased risk of dying among AAs, after controlling for socio-demographics, tumor characteristics, ADT, chemotherapy and primary therapies (model 6). Therefore, in older males treated for locoregional prostate cancer the racial disparities between AAs and Caucasian were narrowed to some extent but not removed by primary therapies. However, these racial disparities did not persist after adjustment for comorbidities (HR = 0.98;0.94−1.03; p < 0.001), which confirms previous observations on survival disadvantage of cancer patients with increasing cormorbidities.16,25,57,59 African Americans are more likely to be hypertensive and to be prescribed hydrochlorothiazide, which had been implicated in prostate carcinogenesis, by increasing calcium and suppressing circulating levels of dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25 (OH)2D), a potential protective factor for prostate cancer.69 Therefore racial differences in comorbidities as well as the treatment of these cormorbidities (not measured by our data), may explain to some degree the racial differences in survival of older men with locoregional prostate cancer treated for the disease.

In addition, we have shown that Asians have the longest survival in this large sample of older men with locoregional disease. Compared with Caucasians, Asians had a 37% decreased risk of dying after adjustment for socio-demographics, tumor characteristics, ADT, chemotherapy, primary therapies and comorbidities (HR = 0.63; 0.58−0.69; p < 0.001). Since the differences between Asians and Caucasians persisted after adjustment, it is plausible to suggest that gene-environment interaction such as differences in the dietary pattern, (implying variation in tumor biology or molecular factors), 10 which was not assessed and controlled for in our analysis, might explain these disparities. Similarly, Hispanics presented with a survival advantage relative to Caucasians and AAs. After adjustment for all covariates (model 7), compared with Caucasians, Hispanics had 23% decreased mortality risk. The survival advantage of Hispanics in this sample of older males treated for local/regional disease, albeit the aggressive treatment received, remains to be explored, which may include differences in the biologic behavior, tumor virulence or simply, the Hispanic paradox.

Generally, racial variance in survival is a complex phenomenon. There is possibility that race is related to CaP screening, frequency of medical examination, which in turn may be associated with education or access and utilization of care, and comorbidities. In interpreting the results of this study, several limitations should be considered. First, though we adjusted for several possible confounders of the effect of race on CaP survival, there are other confounders that were not available in our dataset for possible adjustment, typically oral hormonal agents, dietary profile, concurrent disease and their treatments. Also, as with any epidemiologic investigation, we cannot exclude the possibility of unmeasured or residual confounding influencing our results. Second, we were unable to separate LHRH-A and Orchiectomy, LHRH-A and anti-androgens, regional and localized tumor for separate group analysis. Likewise having data on separate tumor stage for example, local stage alone would provide a better assessment of ADT role in CaP, since CaP tends to be androgen insensitive with locally advanced stage, indicative of poor prognosis with ADT in advanced disease. Third, men aged 65 years and younger, and those who were members of HMO with incident CaP were not included in our sample. We surmise that the distribution and effect of ADT would be different in this age group, and therefore, these results may not be generalizable to younger cases, and men utilizing HMO. Also, because we did not assess the effect of other hormonal agents, care must be exercised not to generalize these findings to all androgen blocking agents and procedures. Finally, we used census tract for education, income and poverty because information on individual level measures of these covariates were not available; measures of the latter type might minimize misclassification and allow more precise estimates of socioeconomic status.48, 70

In summary, there were marked racial variations in the receipt of ADT, primary therapies, and comorbidities by older men treated for locoregional prostate cancer in our sample. However, racial disparities in survival were not affected by racial variations in ADT, but were explained substantially by variations in primary therapies, and by racial differences in comorbidities. Additional research is necessary to assess whether or not the racial variation in cormorbidities is associated with the racial variations in the treatment of comorbidities, as well as to determine whether or not the treatment received for locoregional prostate cancer is due to African American's preference for conservative therapy or clinician's bias not to recommend aggressive and beneficial therapy to older African American men.

Table 3.

Cox Proportional hazards model for the covariates contributing to racial variations in overall survival of African Americans, Hispanics and Asians compared to Caucasians with local/regional prostate cancer

| Variables in models | Hazard ratio (HR)and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) in African Americans, Hispanics and Asians compared to Caucasians* |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

African Americans |

Hispanics |

Asians |

|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Model 1: Race only | 1.26 (1.21−1.32) | 0.83 (0.75−0.92) | 0.72 (0.66−0.79) |

| Model 2: Race + socio-demographics | 1.13 (1.08−1.18) | 0.82 (0.74−0.92) | 0.66 (0.60−0.72) |

| Model 3: Race + socio-demographics + tumor characteristics | 1.11 (1.06−1.16) | 0.81 (0.73−0.90) | 0.64 (0.58−0.70) |

| Model 4: Race + socio-demographics + tumor characteristics + ADT | 1.12 (1.07−1.17) | 0.81 (0.73− 0.90) | 0.64 (0.58−0.70) |

| Model 5: Race + socio-demographics + tumor characteristics + ADT+ chemotherapy | 1.12 (1.07−1.17) | 0.81 (0.73− 0.90) | 0.64 (0.58−0.70) |

| Model 6: Race + socio-demographics + tumor characteristics + ADT+ chemotherapy + primary therapies | 1.06 (1.01−1.10) | 0.79 (0.71−0.87) | 0.64 (0.58−0.70) |

| Model 7: Race + socio-demographics + tumor characteristics + ADT+ chemotherapy + primary therapies + comorbidities | 0.98 (0.94−1.03) | 0.77 (0.69−0.86) | 0.63 (0.58−0.69) |

Notes and abbreviation:

Multi-racial model for overall survival of older men treated for local/regional prostate cancer. ADT= Androgen deprivation therapy

Acknowledgements

The preparation of this manuscript was facilitated by the National Institute of Mental Health grant # RO1 MH062960-03. We acknowledge the efforts of the National Cancer Institute; Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Information Management Services, Inc.; and the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of this database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibilities of the authors. Also, we thank Dr. Jobayer Hossain, Jennifer Holmes and Rachael Mahibar for their assistance in editing the initial draft of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ries LAG, Kosary CL, Hankey BF, et al. SEER Report: Racial/Ethnic Patterns of cancer in the United States 1973−1993. National Cancer Institute; Rockville, MD: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ries LAG, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1973−99. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Thomas A, Murray T, Thun M, Ward E, Samuels A, et al. Cancer Statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu KC, Tarone RE, Freeman HP. Trends in prostate cancer mortality among black men in the United states. Cancer. 2003;97:1507–1516. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanford JL, Stephenson RA, Coyle, et al. Prostate Cancer Trends 1973−1995. SEER Program National cancer Institute NIH Pub No 99−4543; Bethesda, MD: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clegg LX, Li FP, Hankey BF, Chu K, Edwards BK. Cancer survival among US whites and minorities: A SEER program population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1985–1993. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.17.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman RM, Gilliland FD, Eley JW, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in advanced –stage prostate cancer: The Prostate Cancer Outcome study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:388–395. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.5.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harlan L, Brawley O, Pommerenke F, et al. Geographic, age and racial variation in the treatment of local/regional carcinoma of the prostate. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:93–100. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morton RA., Jr. Racial differences in Adenocarcinoma of the prostate in North American Men. Urology. 1994;44:637–645. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(94)80196-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pienta KJ, Esper PS. Risk factors for prostate cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:793–803. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-10-199305150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wingo PA, Bolden S, Tong T. Cancer Statistics for African Americans. CA Cancer J Clin. 1996;46:113–117. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.46.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dayal HH, Chiu C. Factors associated with racial differences in survival for prostatic carcinoma. J Chronic Dis. 1982;35:553–560. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(82)90074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bennett CL, Price DK, Kim, et al. Racial variation in CAG repeat lengths within the androgen receptor gene among prostate cancer patients of lower socioeconomic status. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3599–3604. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witte JS, Nelson KA. Androgen receptor CAG repeats and prostate cancer. Am J. Epidemiol. 2002;155:883–890. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.10.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zelliadt SB, Potosky AL, Etzioni R, et al. Racial disparity in primary and adjuvant treatment for nonmetastatic prostate cancer:SEER-Medicare trends 1991 to 1999. Urology. 2004;64:1171–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du XL, Fang S, Chan W, et al. Racial disparities and socioeconomic status in association with survival in older men with local/regional stage prostate cancer: finding from a large community-based cohort. Cancer. 2006;106:1276–1285. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polednak AP. Prostate cancer treatment in black and white men: The need to consider both stage at diagnosis and socioeconomic status. J Natl Med Assoc. 1998;90:101–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conlisk EA, Lengerish EJ, Demark-Wahnerfried W, et al. Prostate cancer: Demographic and behavioral correlates of stage at diagnosis among blacks and whites in North Carolina. Urology. 1999;53:1194–1199. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarman GJ, Kane CJ, Moul JW, et al. Impact of socioeconomic status and race on clinical parameters of patients undergoing radical prostatectomy in an equal access health care system. Uroloogy. 2000;56:1016–1020. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00808-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brawn PN, Johnson EH, Kuhl DL, et al. Stage at presentation and survival of white and black patients with prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;71:2569–73. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930415)71:8<2569::aid-cncr2820710822>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Optenberg SA, Thompson IM, Friedrichs P, et al. Race, treatment, and long-term survival from prostate cancer in an equal–access medical care delivery system. JAMA. 1995;274:1599–1605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denberg TD, Beasty BL, Kim FJ, et al. Marriage and ethnicity predict treatment in localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:1819–1825. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan Y, Carvlhal GF, Catalona WJ, et al. Primary treatment choices for me with clinically localized prostate carcinoma detected by screening. Cancer. 2000;88:1122–1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demark-Wahnefried W, Schildkraust JM, Iselin CE, et al. Treatment options, selection, and satisfaction among African Americans and white men with prostate cancer in North Carolina. Cancer. 1998;83:320–330. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980715)83:2<320::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vijayakumar S, Weichselbaum R, Vaida F, et al. Prostate Specific Antigen levels in African Americans correlate with insurance status as the indicator of socioeconomic status. Cancer J Sci Am. 1996;2:225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demers RY, Tiwari A, Wei J, et al. Trends in utilization of androgen–deprivation therapy for patients with prostate carcinoma suggest an effect on mortality. Cancer. 2001;92:2309–2317. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011101)92:9<2309::aid-cncr1577>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Potosky AL, et al. Potential for cancer related services using linked Medicare-tumor registry database. Med care. 1993;31:732–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waren JL, et al. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV3–IV18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandelblatt JS, et al. Variations in breast carcinoma treatment in older Medicare beneficiaries: is it black or white. Cancer. 2002;95:1401–14. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Cancer institute [December,3,2005];SEER-Medicare Linked Database. http:healthservices.cancer.gov/seermedicare.

- 31.Charlson M, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic in longitudinal studies: development and valididation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40:373. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klienbaum DG. Survival analysis: A self-Learning Text. Springer-Verlag; New York, NY: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fowler JE, Jr, Terrel F. Survival in blacks and whites after treatment for localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 1996;156:133–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pieneta KJ, et al. effect of age and race on the survival of men with prostate cancer in the metropolitan Detriot tricounty area, 1973 to 1987. Urology. 1995;45:93–101. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(95)96996-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roach M, III, et al. Race and survival of men treated for prostate cancer on radiation therapy oncology group phase III randomized trials. Urology. 2003;169:245–250. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burns RB, et al. Black women received less mammography even with similar use of primary care. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:173–82. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-3-199608010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bach PB, et al. Racial differences in the treatment of early early-stage lung cancer. N. Engl J Med. 1999;341:1198–1205. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klotz L. Combined androgen blockade in prostate cancer: meta-analyses and associated issues. BJU International. 2001;87:806–813. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akaza H. Adjuvant goserlin improves clinical disease-free survival and reduces disease-related mortality in patients with locally advanced or localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2004;93:42–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2004.04552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koff SG, Connelly RR, Bauer JJ, et al. Primary hormonal therapy for prostate cancer: experience with 135 consecutive PSA-ERA patients from tertiary care military medical center. Prostate cancer and Prostatic Diseases. 2002;5:152–158. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, et al. A human prostatic epithelial model of hormonal carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6064–6072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bosland MC. The role of steroid hormone in prostate carcinogenesis. J Natl cancer Inst Monogr. 2000;27:39–66. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu AH, et al. Lifestyle determinants of 5 a reductase metabolites in older African-Americans, Whites, and Asian American men. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2001;10:533–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Platz EA, et al. Racial variation in prostate cancer incidence and in hormonal system markers among male health professionals. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:2009–2017. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.24.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thatai LC, et al. Racial disparity in clinical course and outcome of metastatic and androgen-independent prostate cancer. Urology. 2004;64:738–743. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ward E, et al. Cancer Disparities by Race/Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:78–93. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Godley PA, et al. Racial differences in mortality among Medicare recipients after treatment for localized prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1702–1710. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Geronimus AT, Bound J. Use of census-based aggregate variables to proxy for socioeconomic group: evidence for national samples. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:475–478. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harlan L, Brawley O, Pommerenke F, Wali P, Krammer B. Geographic, age, and racial variation in the treatment of local/regional carcinoma of prostate. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:93–100. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Imperato PJ, Nenner RP, Will TO. Radical prostatectomy: lower rates among African-American men. J Natl Med Assoc. 1996;88:589–594. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horner RD. Racial variation in cancer care: a case study of prostate cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 1998;97:99–114. doi: 10.1007/978-0-585-30498-4_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Harlan LC, Kramer BS. Trends and black/white differences in treatment for nonmetastatic prostate cancer. Med Care. 1998;36:1337–1348. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199809000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Desch CE, Penberthy L, Newschaffer CJ, Hilner BE, Whittemore M, McClish D, et al. Factors that determine the treatment for local and regional prostate cancer. Med Care. 1996;34:152–62. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199602000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kubritch WS, 3rd, Williams BJ, Whatley T, Easthman JA. Serum testosterone levels in African-American and white men undergoing prostate biopsy. Urology. 1999;54:10351038. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gann PH, Hennekenes CH, Ma J, Longcope C, Stampfer MJ. Prospective study of sex hormone levels and the risk of prostate cancer. J Natl Inst. 1996;86:1118–1126. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.16.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heikkila R, Aho K, Helliovaara M, et al. Serum testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin concentrations and the risk of prostate carcinoma: a longitudinal study. Cancer. 1999;86:312–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tewari A, Horninger W, Pelzer AE, et al. Factors contributing to the racial differences in prostate cancer mortality. BJU Int. 2005;96:1247–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Polednak AP, Flannery JT. Black versus white racial differences in clinical stage at diagnosis and treatment of prostatic cancer in Connecticut. Cancer. 1993;71:3582–3593. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19921015)70:8<2152::aid-cncr2820700824>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robins AS, Whittemore AS, Thom DH. Differences in socioeconomic status and survival among white and black men with prostate cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:493–4. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shavers VL, Brown ML, Potosky AL, et al. Race/ethnicity and the receipt of watchful waiting for initial management of prostate cancer. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:146–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Du XL, Goodwin JS. Patterns of use of chemotherapy for breast cancer in older women: Findings from Medicare claims data. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19:1455–1461. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Du XL, Key CR, Dickie L, et al. External Validation of Medicare Claims for Breast Cancer Chemotherapy Compared with Medical Chart Reviews. Medical Care. 2006;44:124–131. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196978.34283.a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Du XL, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Information on radiation therapy in patients with breast cancer: the advantages of the linked Medicare and SEER data. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1999;52:463–470. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Du XL, Chan W, Giordano S, et al. Variation in Modes of Chemotherapy Administration for Breast Carcinoma and Association with Hospitalization for Chemotherapy-related Toxicity. Cancer. 2005;104:913–924. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Steginga SK, Occhipinti S, Gardiner RA, Yaxley J, Heathcote P. Making decisions about treatment for localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2002;89:255–260. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-4096.2001.01741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St George DM. Distrust, race, and research. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2458–2463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fowler FJ, Jr., McNaugghton CM, Albertsen PC, et al. Comparison of recommendations by urologists and radiation oncologist for treatment of clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2000;283:3217–3222. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.24.3217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Feldman-Stewart D, Brundage MD, Hayter C, et al. What prostate cancer patients should know: variation in professionals’ Opinions. Radiother Oncol. 1998;49:111–123. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(98)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Wolk A, et al. Calcium and fructose intake in relation to risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:442–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Holmes L, Chan W, Jiang Z, Du XL. Effectiveness of androgen deprivation therapy in prolonging survival of older men treated for locoregional prostate cancer. Prostate cancer and Prostatic Dis. 2007;10:388–395. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]