Abstract

Epiboly spreads and thins the blastoderm over the yolk cell during zebrafish gastrulation, and involves coordinated movements of several cell layers. Although recent studies have begun to elucidate the processes that underlie these epibolic movements, the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved remain to be fully defined. Here, we show that gastrulae with altered Gα12/13 signaling display delayed epibolic movement of the deep cells, abnormal movement of dorsal forerunner cells, and dissociation of cells from the blastoderm, phenocopying e-cadherin mutants. Biochemical and genetic studies indicate that Gα12/13 regulate epiboly, in part by associating with the cytoplasmic terminus of E-cadherin, and thereby inhibiting E-cadherin activity and cell adhesion. Furthermore, we demonstrate that Gα12/13 modulate epibolic movements of the enveloping layer by regulating actin cytoskeleton organization through a RhoGEF/Rho-dependent pathway. These results provide the first in vivo evidence that Gα12/13 regulate epiboly through two distinct mechanisms: limiting E-cadherin activity and modulating the organization of the actin cytoskeleton.

Introduction

During vertebrate gastrulation, an embryo of simple and symmetrical morphology is reshaped to reveal its fundamental body plan. This process is accomplished by cooperation of four morphogenetic movements—epiboly, internalization, and convergence and extension (C&E)—that are largely conserved among vertebrates (Arendt and Nubler-Jung, 1999; Leptin, 2005; Solnica-Krezel, 2005). Epiboly starts at the late blastula stage as the yolk cell pushes into the blastoderm, which thins and expands vegetally until it encloses the entire yolk cell (Warga and Kimmel, 1990; Solnica-Krezel, 2006; Rohde and Heisenberg, 2007). At this stage, the embryo is composed of four cell layers: the enveloping layer (EVL), deep cells, the yolk syncytial layer (YSL), and the yolk cell. The EVL is a superficial epithelial layer that covers a mass of deep cells, which give rise to embryonic tissues. The YSL is a shallow and superficial cytoplasmic layer within the yolk cell (Solnica-Krezel and Driever, 1994; Rohde and Heisenberg, 2007). Proper epiboly involves coordinated movements of all of these layers, and the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms remain to be fully defined (Solnica-Krezel, 2006; Rohde and Heisenberg, 2007).

Recent studies indicate that E-cadherin–mediated cell–cell adhesion plays a critical role in zebrafish epiboly. In both E-cadherin mutant embryos and embryos injected with E-cadherin morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) to block its translation, the epibolic movement of the deep cells is delayed or arrested at midgastrulation, although the YSL and EVL expand vegetally in a relatively normal fashion (Babb and Marrs, 2004; Kane et al., 2005; McFarland et al., 2005; Shimizu et al., 2005). This epibolic delay has been attributed to impaired radial intercalation resulting from decreased adhesion among the deep cells and between the deep cells and the EVL (Kane et al., 2005; Montero et al., 2005; Shimizu et al., 2005). An additional cell–cell adhesion defect was observed in E-cadherin–deficient embryos, with cells bulging and detaching from the embryonic surface (Babb and Marrs, 2004; Kane et al., 2005; McFarland et al., 2005; Shimizu et al., 2005).

E-cadherin is a plasma membrane glycoprotein that is indirectly linked to the actin cytoskeleton through β-catenin (Barth et al., 1997). The involvement of E-cadherin in morphogenesis and differentiation during the early development has been also demonstrated in many species including mouse, chick, and frog (Halbleib and Nelson, 2006). In addition, E-cadherin is essential for cell migration and polarity, as well as neuronal synapse function. E-cadherin expression is regulated at various levels including gene expression, protein stability, and intracellular protein distribution (Halbleib and Nelson, 2006). Down-regulation of E-cadherin is regarded as the hallmark of the epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and is often observed in invasive tumor cells (Behrens, 1999).

In comparison to our fairly detailed knowledge about the regulation of E-cadherin expression, we know very little about regulation of its activity. However, recent studies in cell culture indicate that heterotrimeric G proteins of the Gα12 family (Gα12 and Gα13) can modulate E-cadherin function: Gα12/13 can bind E-cadherin at its cytoplasmic domain to block the β-catenin–binding site, resulting in inhibition of cell–cell adhesion (Kaplan et al., 2001; Meigs et al., 2001; Meigs et al., 2002). Nevertheless, the significance of the Gα12/13 and E-cadherin interaction during morphogenesis remains to be tested.

During epiboly, the yolk cell may serve as a towing motor to drive the movements of epiboly. Nuclei of the YSL move vegetally even after removal of the blastoderm (Trinkaus, 1951), which indicates that the YSL can undergo epiboly autonomously. Because the EVL and the YSL are tightly attached (Betchaku and Trinkaus, 1986), EVL epiboly is believed to depend on the YSL expansion. In addition, endocytosis in the YSL near the blastoderm margin results in removal of the yolk cytoplasmic membrane and could play a role in epiboly by drawing the blastoderm to the vegetal pole (Trinkaus, 1993; Solnica-Krezel and Driever, 1994).

The cytoskeleton plays many important roles during epiboly. Extensive microtubule networks in the yolk cell may facilitate the epibolic movements, as microtubule disruption completely inhibits the movement of yolk syncytial nuclei (YSN) and impairs the epibolic movements of the deep cells and the EVL (Strahle and Jesuthasan, 1993; Solnica-Krezel and Driever, 1994). A decrease in the amount of polymerized microtubules in the yolk cell also leads to epiboly delay (Hsu et al., 2006). Actin microfilaments throughout the embryo contribute to epiboly as well (Zalik et al., 1999; Cheng et al., 2004; Koppen et al., 2006). Three distinct actin structures are elaborated during late epiboly stages: two rings at the margin of the deep cells and the EVL, and a punctate band of actin accumulation in the external YSL adjacent to the EVL margin (Cheng et al., 2004). It has been proposed that the actin rings act as a “purse string” to pull the EVL vegetally, thereby advancing the epiboly process (Cheng et al., 2004), whereas the punctate band of contractile elements including actin and myosin 2 in the YSL contributes to the shortening of the actin bands and the EVL margin, moving the EVL toward the vegetal pole (Koppen et al., 2006). Disruption of these actin structures, as a consequence of either cytochalasin B treatment (Cheng et al., 2004), interference with myosin2 (Koppen et al., 2006), or the homeobox transcription factor Mtx2 (Wilkins et al., 2008), results in a delay or failure in epiboly. Similarly, an abnormal cytoskeleton contributes to the epibolic delay in Pou5fl-deficient embryos (Lachnit et al., 2008).

We previously demonstrated that Gα12/13 are required for C&E gastrulation movements in zebrafish (Lin et al., 2005). Here, we find that Gα12/13 regulate epiboly in zebrafish, and provide evidence that Gα12/13 interact with E-cadherin to negatively modulate E-cadherin–mediated cell–cell adhesion. Moreover, we show that Gα12/13 also regulate epiboly by promoting actin microfilament assembly through a Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF)-dependent signaling pathway. Our results therefore identify a novel Gα12/13-dependent mechanism for modulating epiboly during vertebrate gastrulation.

Results

Disruption of Gα12/13 function results in epiboly delay

We have previously identified one Gα12 and two Gα13 (Gα13a and Gα13b isoforms) in zebrafish and demonstrated that proper Gα12/13 signaling is essential for C&E movements, as well as for epiboly during zebrafish gastrulation (Lin et al., 2005). To define further the mechanisms whereby Gα12 and Gα13 regulate epiboly, we used gain- and loss-of-function approaches. To enhance Gα13 function, we injected embryos with a synthetic RNA encoding Gα13a. To inhibit Gα12/13 function, we injected embryos with a mixture of antisense MOs (3MO) that interfere with translation of the three Gα12/13 transcripts (gna13a, gna13b, and gna12; 4 ng each). Alternatively, we injected a synthetic RNA encoding the carboxy-terminal (CT) peptides of Gα12/13, which have been shown to disrupt the coupling of Gα12/13 to their cognate receptors (Akhter et al., 1998; Gilchrist et al., 1999; Arai et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2005). In zebrafish, epiboly initiates at the sphere stage and is complete when the blastoderm encloses the yolk cell (Warga and Kimmel, 1990). Embryos with either an excess or deficiency of Gα12/13 expression initiated epiboly and progressed through early stages at rates comparable to those of their uninjected siblings. Furthermore, they underwent internalization normally and formed embryonic shields of normal morphology (unpublished data). However, when the blastoderm covered 70% of the yolk cell in control embryos (70% E), embryos with altered Gα12/13 activity lagged in epibolic movements behind their siblings by 10–20%. By 80% E, only a very small fraction of uninjected embryos (1.1 ± 1.9%; 136 embryos) showed epiboly defects, yet a majority of embryos overexpressing Gα13a (98.5 ± 2.6%, 258 embryos), injected with the Gα13-CT RNA (86.5 ± 6.5%, 106 embryos) or injected with 3MO (84.4 ± 5.7%, 143 embryos), exhibited epiboly defects (Fig. 1 M).

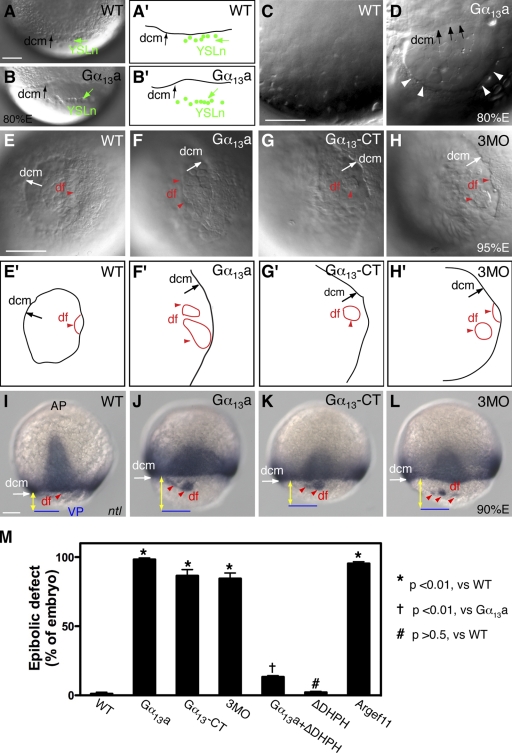

Figure 1.

Gα12/13 regulate epibolic movements of the deep cells. (A and B) Nomarski images of control WT embryos (A) and embryos overexpressing Gα13a (B) at 80% epiboly (A′ and B′ are schematic drawings of A and B), showing the dcm and YSL nuclei (YSLn; green arrows and dots), which move together in control embryos (A and A′) but are separated in embryos overexpressing Gα13a (B and B′). (C and D) Nomarski images of yolk cell region at high magnification in a control WT embryo (C) and an embryo overexpressing Gα13a (D), showing distortions in the YCL (white arrowheads). (A–D) Lateral view, with dorsal shown toward the right and vegetal toward the bottom. (E–H) Nomarski images of control WT embryos (E), embryos overexpressing either full-length Gα13a (F), or the CT fragment of Gα13a (Gα13-CT; G), and embryos injected with 3MOs against gna13a, gna13b, and gna12 (4 ng each; H) at 95% epiboly. (E′–H′) Schematic drawings of E–H. Vegetal view is shown. df, df cells (red arrowheads). Note: in F–H versus E, the vegetal opening is much larger, and dfs are separated from the dcm; in F and H, the dfs are split. (I–L) Expression of the ntl mRNA at 90% epiboly. Images show ntl expression domains at dcm and df. Dorsal view, with the vegetal pole (VP; blue lines) toward the bottom. Yellow lines with double arrows, distance from dcm to VP. Bars, 100 µm. (M) The percentage of embryos with epibolic defects. Data are compiled from two to three different experiments. Error bars represent mean ± SEM.

The YSL consists of an internal YSL and an external YSL that is populated with YSN (Solnica-Krezel and Driever, 1994). The EVL is tightly linked to the YSL margin. Therefore, as seen in Fig. 1 (A and A′), during the course of normal epiboly, the YSN and the deep cell margin (dcm) stay together (the EVL is invisible, as it is not in the focal plane; Trinkaus, 1984; Solnica-Krezel and Driever, 1994). However, in embryos overexpressing Gα13a, a sizable gap was formed between the YSN and the dcm (Fig. 1, B and B′), which indicates that epibolic movement of the deep cells lags behind the movement of the YSL. Thus, the distance between the dcm and the vegetal pole is significantly greater in embryos overexpressing Gα13a than in the uninjected control (Fig. 1, A and B). In addition, we noted that in contrast to the uniform and smooth appearance of the yolk cytoplasmic layer (YCL; a thin anuclear cytoplasmic layer covering the yolk mass) in control embryos (Fig. 1 C), this structure was frequently distorted in Gα13a-expressing embryos, exhibiting an uneven thickness (Fig. 1 D, arrowheads). As epiboly progressed to 95% E, the dcm of wild-type (WT) embryos moved closer to the vegetal pole (Fig. 1, E and E′), but those of embryos overexpressing Gα13a, the dominant-negative Gα13-CT peptide, or injected with 3MO had a much larger vegetal opening (Fig. 1, E–H′). Moreover, the dorsal forerunners (dfs), a small dorsal cell population that normally moves toward the vegetal pole as a single cluster in close association with the dcm (Fig. 1 E; Cooper and D'Amico, 1996), were well separated from the dcm and far ahead of the remaining deep cells in embryos with reduced or excess Gα12/13 function. Interestingly, in these embryos, the df cells split and formed several smaller clusters (Fig. 1, F–H). These observations in live embryos were confirmed by analyzing the expression of the no tail (ntl) gene, which marks the mesodermal precursors at the dcm and the df cells (Schulte-Merker et al., 1994). As seen in Fig. 1 (I–L), the distance between the dcm and the vegetal pole was significantly greater in embryos with either reduced or excess Gα12/13 function than that in control embryos, and dfs were separated from the dcm and divided into several smaller clusters. The observed delay in epiboly and abnormal behavior of the dfs resemble aspects of the phenotypes that have been described for the half-baked (hab) mutants, which harbor mutations in the cadherin1 (cdh1; E-cadherin) gene (Kane et al., 1996; Kane and Warga, 2004), and in embryos injected with an MO that targets cdh1 (Babb and Marrs, 2004). This observation suggested a possible link between Gα12/13 function and E-cadherin activity.

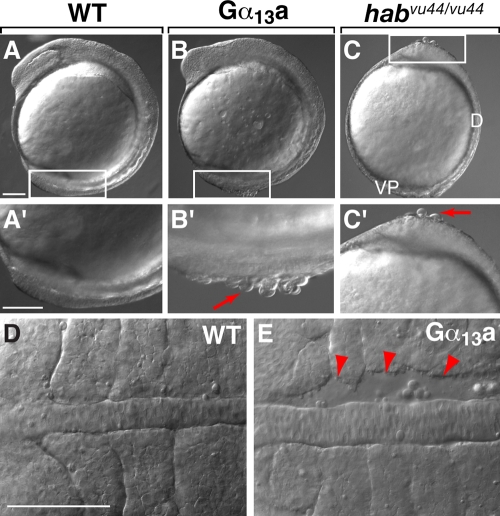

In embryos overexpressing Gα13a, but not those injected with Gα13-CT RNA or 3MO (not depicted), cells frequently dissociated from the embryonic surface (Fig. 2, A–C′), and gaps formed between the paraxial and axial mesoderm during segmentation (Fig. 2 E). These phenotypic changes have also been observed in hab mutant embryos and have been attributed to defects in cell–cell adhesion (Kane et al., 2005; McFarland et al., 2005). Together, these observations suggest that Gα12/13 signaling may negatively regulate E-cadherin–mediated cell–cell adhesion during zebrafish gastrulation.

Figure 2.

Overexpression of Gα13a results in cell adhesion defects in embryonic tissues. (A–C′) Nomarski images of uninjected WT embryos, embryos overexpressing Gα13a, and habvu44/vu44 mutant (E-cadherin–deficient) embryos. Higher magnification images of the boxed areas are shown in A′–C′. Red arrows indicate cells detaching from the blastoderm. Lateral view is shown, with dorsal (D) toward the right and the vegetal pole (VP) toward the bottom. (D and E) Nomarski images of notochord and somites in the WT embryos and embryos overexpressing Gα13a at the 4–5 somite stage. Red arrowheads indicate gaps between the notochord and somites. Dorsal view is shown, with anterior to the left. Bars, 100 µm.

Gα12/13 do not influence E-cadherin expression or intracellular distribution

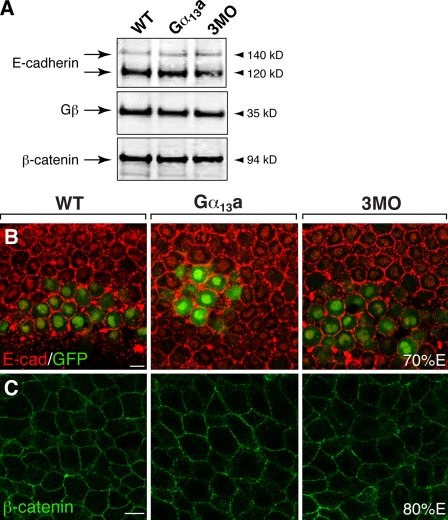

To test the hypothesis that Gα12/13 regulate epiboly by modulating the function of E-cadherin, we first determined if Gα12/13 affect the expression of E-cadherin in embryos with reduced or excess signaling. We performed Western blot analyses using an anti–E-cadherin antibody with protein extracts prepared either from gastrulae injected with gna13a RNA or 3MO, or from uninjected control siblings. As shown in Fig. 3 A, two prominent bands of E-cadherin, which may correspond to two glycosylation forms of E-cadherin, were detected, as described previously (Babb and Marrs, 2004). There was no clear difference in the expression level of E-cadherin protein between the control embryos and embryos with excess or reduced Gα12/13 signaling (Fig. 3 A). We then performed whole-mount immunostaining to determine if Gα12/13 regulate the cellular distribution of E-cadherin. It has been shown that E-cadherin is expressed at a higher level at the anterior region of the hypoblast during gastrulation (Babb and Marrs, 2004). To identify this region, we used embryos obtained from transgenic TG:[gsc-GFP] fish, in which GFP is expressed in the dorsal midline (Doitsidou et al., 2002; Inbal et al., 2006). As shown in Fig. 3 B, in control embryos at 70% E, E-cadherin was expressed in all blastomeres, predominantly on the cell membranes, but also in a punctate pattern in the cytosol, as described previously (Babb and Marrs, 2004; Montero et al., 2005). Our analyses revealed that neither Gα13a overexpression nor Gα12/13 down-regulation (3MO-mediated) affected the expression level or the cellular distribution of E-cadherin (Fig. 3 B).

Figure 3.

Altered Gα12/13 expression does not change the levels and distribution of E-cadherin and β-catenin. (A) Western blots showing the expression levels of E-cadherin, the G protein β subunit, and β-catenin in the uninjected WT, Gα13a-overexpressing, and three MOs (3MO)-injected gastrulae. (B and C) Confocal images showing the cellular distribution of E-cadherin (red) in the anterior mesendoderm of embryos at 70% E (B; gsc-GFP labels the prechordal mesoderm), and of β-catenin in the lateral mesoderm in embryos at 80% E (C). Bars, 10 µm.

Gα12/13 regulate epiboly by inhibiting E-cadherin activity

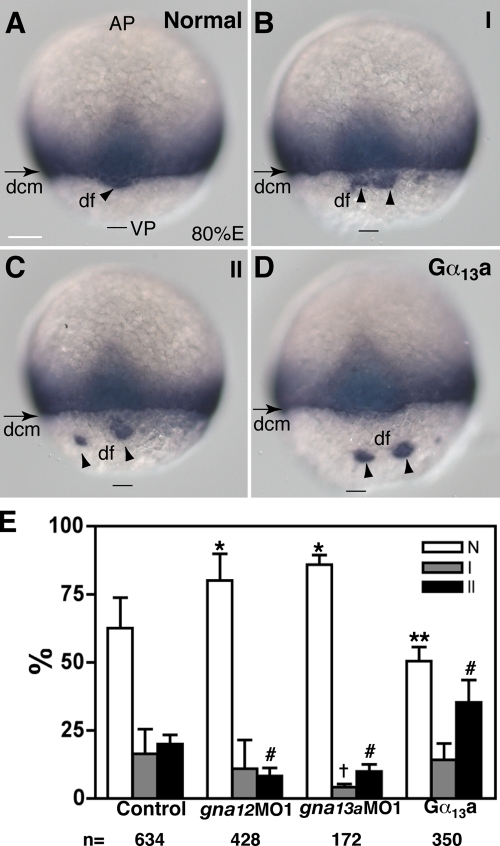

Next, we aimed to determine whether Gα12/13 modulate E-cadherin function in vivo by testing their genetic interactions. We took advantage of a zebrafish mutant, habvu44, harboring a premature stop codon at amino acid residue L553 within the EC4 domain of the extracellular portion of the cdh1 gene (Kane et al., 2005). habvu44/vu44 embryos display an epiboly delay/arrest after midgastrulation, probably due to a moderating effect of the maternal contribution of E-cadherin, which has been shown to cooperate with the zygotically expressed E-cadherin to regulate epiboly (Shimizu et al., 2005). We injected embryos derived from crosses among habvu44 heterozygous fish with either a small dose of synthetic RNA encoding Gα13a (10 pg) or a single MO against Gα13a or Gα12 (4 ng) to elevate or reduce the function of Gα13 or Gα12, respectively. Such treatments alone had no effect on the epiboly in WT embryos (unpublished data). We then assessed whether this manipulation of Gα12/13 function can modulate the phenotypic changes caused by E-cadherin deficiency by analyzing the ntl expression profile. We reasoned that if Gα12/13 negatively regulate the E-cadherin activity, then excess Gα12/13 function exacerbates it, and decreased Gα12/13 signaling should suppress the phenotypic changes caused by E-cadherin deficiency. Among the uninjected progeny from habvu44/+ parents, 63 ± 11% embryos showed a normal pattern of ntl expression (Fig. 4 A); 16 ± 9% exhibited mild defects in epiboly, in which their df cells were divided into smaller clusters in spite of being tightly associated with the margin (type I defect; Fig. 4 B); and 20 ± 3.3% showed a strong epiboly delay in the deep cells and obvious separation of the df cells from the dcm (type II defect; Fig. 4 C). This phenotypic distribution is consistent with a partial penetrance of both the dominant df defect and the recessive epiboly phenotype of habvu44 mutation (Kane et al., 2005). A reduction in the expression of either Gα12 or Gα13 in the progeny of habvu44/+ heterozygotes partially suppressed the mutant epibolic defects, as indicated by a significant increase in the proportion of embryos showing normal ntl expression in the blastoderm margin and df cells, and a decrease in the percentage of embryos with severe epibolic defects (type II; Fig. 4 E). Conversely, a slight increase in Gα13 activity exacerbated these defects (Fig. 4, D–E). These results support the notion that Gα12/13 regulate epiboly through E-cadherin by acting as negative regulators of E-cadherin activity.

Figure 4.

Gα12/13 signaling modulates the phenotype of habvu44 mutant embryos. (A–C) Different phenotypic classes of progeny of habvu44/+ parents revealed by ntl staining: normal pattern (A), type I (B), and type II (C). See text for details. (D) A representative image showing exacerbation of epibolic defects of habvu44 mutant embryos overexpressing Gα13a (20 pg; see text for details). A dorsal view is shown. AP, animal pole; VP, vegetal pole. Bars, 100 µm. (E) Effects of altered Gα12/13 signaling on distribution of the phenotypic classes of progeny from habvu44/+ parents. The data were generated from at least three separate experiments, with the total number of embryos indicated below the graph. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.05; †, P < 0.01; #, P < 0.001 versus control.

Gα12/13 interact with E-cadherin and inhibit cell adhesion

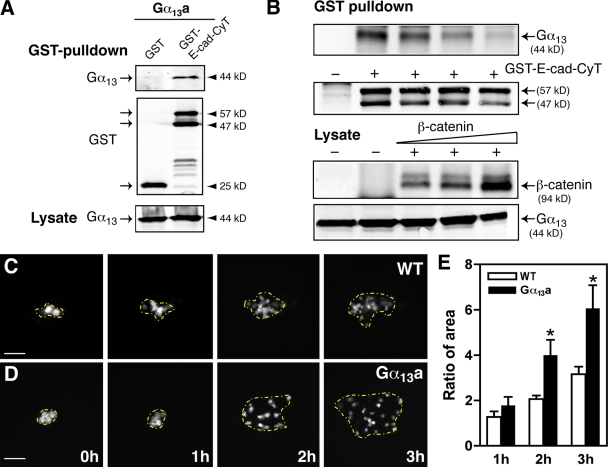

To better understand the mechanisms by which Gα12/13 regulate E-cadherin activity, we set out to test these two proteins for physical interactions in vivo. Because previous studies in cultured cells had shown that mammalian Gα12 or Gα13 can bind the cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin (Kaplan et al., 2001; Meigs et al., 2001), we performed the following procedures. First, we cotransfected HEK 293 cells with zebrafish Gα13a and a GST-tagged construct encoding the E-cadherin cytoplasmic terminus (E-cad–CyT) or GST only, and performed a GST pull-down assay. As shown in Fig. 5 A, Gα13a was pulled down by GST–E-cad–CyT but not by GST alone, which suggests a specific association between zebrafish Gα13a and the E-cad–CyT. In addition, we demonstrated that β-catenin can compete with Gα13a for the binding to E-cadherin in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5 B), confirming that the β-catenin– and Gα13a-binding sites on E-cadherin are close to one another (Kaplan et al., 2001). However, we did not observe any obvious change in the expression level and intracellular distribution of β-catenin in embryos with altered Gα12/13 expression (Figs. 3 C and S1).

Figure 5.

Gα13a interacts with E-cadherin and inhibits cell adhesion. (A) Gα13a interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin. The GST pull-down assay was performed on cell extracts from HEK 293 cells cotransfected with Gα13a and either GST or a GST-tagged cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin (GST–E-cad–CyT). The precipitates were immunoblotted with anti-Gα13 and anti-GST antibodies. The level of Gα13a expression in the lysates is shown at the bottom of the panel. (B) β-catenin competes with E-cadherin for binding to Gα13a in a dose-dependent manner. HEK 293 cells were transfected with Gα13a and GST–E-cad–CyT with or without β-catenin at various doses, and the GST pull-down assay was performed. The expression levels of β-catenin and Gα13a in the lysates are shown. (C and D) Overexpression of Gα13a enhances cell scattering in the blastoderm. Shown are representative images of labeled cells in the blastoderm of control WT embryos and embryos overexpressing Gα13a scattering over time. The area of cell scattering is indicated by the yellow broken lines, which mark the cells at the outer edge. Bars, 100 µm. (E) Quantitative data from four separate experiments (eight embryos in each group), showing the ratio of the area of cell scattering relative to the starting point, at different time points. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05 versus control.

E-cadherin is known to regulate cell–cell adhesion in zebrafish (Meigs et al., 2002; Montero et al., 2005) and many other animals (Halbleib and Nelson, 2006). Moreover, the binding of Gα13 to E-cadherin interferes with its cell adhesive function in mammalian cultured cells (Meigs et al., 2002). To determine if Gα12/13 can influence cell adhesion in zebrafish, we performed a cell tracing experiment in embryos (Warga and Kane, 2003). In this assay, zygotes were first injected with gna13a RNA to enhance Gα13 function. At the 256-cell stage, a single cell at the animal pole of an uninjected or gna13a-RNA–injected blastula was then injected with fluorescein dextran, then the distribution of the progeny of the labeled cells at several time points up to 50%E was analyzed. During embryonic development, blastomeres at the animal pole become separated from each other by intercalating radially from deeper layers to the more superficial layers without significant directional migration (Warga and Kimmel, 1990). This phenomenon is thought to be mediated by E-cadherin–dependent cell–cell adhesion interactions, because in hab mutants (E-cadherin deficient), cells intercalate from the deeper to the more superficial layers but fail to maintain this position and often fall back into the deeper layer (Warga and Kane, 2003; Kane et al., 2005). We found that progeny of the labeled cells gradually dispersed over time in control embryos (Fig. 5 C) and in embryos overexpressing Gα13a (Fig. 5 D). To quantify the scattering, we marked the outside edge of the regions containing the labeled cells, and calculated the areas. We then determined a scattering factor by comparing the areas at different time points to the initial area for each embryo. 1 h after injection, the scattering factor for the Gα13a-expressing embryos was similar to that of control embryos. However, by the second and third hour, the ratio in embryos overexpressing Gα13a was significantly greater than that in control embryos (Fig. 5, C–E). These results indicate that overexpression of Gα13a enhanced dispersion in the blastoderm during epiboly, which suggests that Gα13a-expressing cells have a reduced tendency to adhere to one another. These findings provide further support for the notion that signaling via Gα13 negatively regulates E-cadherin activity.

Gα12/13 regulate actin cytoskeleton assembly during epiboly via a RhoGEF/Rho-dependent pathway

Although embryos with enhanced or decreased Gα12/13 showed similar epibolic defects in deep cells as E-cadherin mutant embryos, we noted that Gα13a-overexpressing embryos exhibited additional defects such as a distorted YCL (Fig. 1 D), which suggests that Gα13a signaling may contribute to the regulation of epiboly via additional mechanisms that are independent of E-cadherin. Such distortions of the YCL have also been observed in embryos with cytoskeleton abnormalities; e.g., in embryos treated with taxol to stabilize microtubules (Solnica-Krezel and Driever, 1994) or in Pou5fl mutants (Lachnit et al., 2008). We have previously shown that, like their mammalian counterparts, zebrafish Gα12/13 can promote actin stress fiber formation in cultured cells (Lin et al., 2005). Based on these observations, we tested whether Gα12/13 can also regulate cytoskeletal function in zebrafish gastrulae.

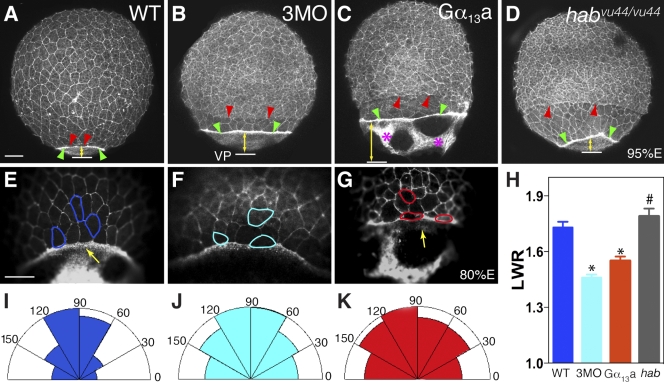

To assess the organization of actin cytoskeleton during gastrulation, we visualized actin by whole-mount immunostaining with phalloidin. As shown in Fig. 6 (A–D), the confocal images revealed the periphery of the superficial EVL cells and the deep cells beneath, as well as two actin rings at the margins of the deep cells and the EVL (Fig. 6, A–D, red and green arrowheads, respectively), as reported previously (Cheng et al., 2004). In WT embryos, the actin rings adjacent to the deep cells and the EVL are closely associated (Fig. 6 A), which indicates that EVL and the deep cells move together toward the vegetal pole during epiboly. Consistent with previous papers on studies performed in habvu44/vu44 mutant embryos, the deep cells exhibited impaired epiboly and lagged behind the EVL margin (Fig. 6 D); whereas the EVL underwent epiboly at a relatively normal rate, as revealed by the observation that the distance between the EVL margin and the vegetal pole (Fig. 6, yellow lines with arrows) in the mutant was comparable to that in WT embryos (Fig. 6, A and D; Kane et al., 2005; Koppen et al., 2006). As expected, embryos with reduced or excess Gα12/13 function displayed similar epibolic defects of the deep cells (separation from EVL margin), although the defects were more minor than those in habvu44/vu44 mutant embryos (Fig. 6, B–D). However, embryos with altered Gα12/13 function exhibited an epibolic delay of the EVL, as the distance between the EVL margin and vegetal pole (Fig. 6, yellow lines with arrows) was significantly increased relative to that in the age-matched uninjected WT embryos (Fig. 6, A–C).

Figure 6.

Gα12/13 regulate cytoskeleton organization during epiboly. (A–D) Confocal images show phalloidin staining of F-actin in gastrulae. Red and green arrowheads indicate the margin of the deep cells and the EVL, respectively; yellow lines with arrows indicate the distance between the EVL margin and the vegetal pole (VP; white lines). Pink asterisks indicate the actin bundles in the yolk. (E–G) Representative images of the EVL cells indicated at high magnification. The cell boundaries of a few EVL cells of each group are highlighted. Note: the EVL cells in embryos injected with 3MO and embryos overexpressing Gα13a are rounder and not correctly aligned. Yellow arrows indicate an actin ring in the vegetal margin of the EVL. Bars, 100 µm. (H) Quantitative data showing the LWRs of the EVL cells close to the margin. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. *, P < 0.05 versus WT. #, P > 0.05 versus control. (I–K) The half-Rose diagrams show the numbers of EVL cells for which the angle of the long axis relative to a line parallel to the EVL margin falls within each sector.

During epiboly, the constriction of the marginal EVL cells leads to dramatic cell-shape changes in the EVL cells, and to the elongation of the EVL cells along the animal–vegetal axis. Failure of such cell-shape changes has been implicated in epibolic defects (Koppen et al., 2006). To further evaluate the morphology of the EVL cells in embryos with altered Gα12/13 function, we took confocal images of phalloidin-stained embryos at higher magnification, and analyzed cell shape (length-to-width ratio [LWR]) and orientation (the angle of the long axis of the EVL cells relative to a line parallel to the EVL margin) of the EVL cells near the margin. As shown in Fig. 6 (E–H), there was no significant difference in the intensity of F-actin staining in the EVL cells between the uninjected WT embryos and embryos injected with 3MO or the Gα13a RNA. However, both the shape and orientation of the EVL cells in embryos with reduced or excess Gα12/13 function were significantly altered with respect to those in the control embryos (Fig. 6 E-G). In the uninjected control embryos, the EVL cells were elongated, with a mean LWR of 1.73 ± 0.3 (220 cells, 6 embryos), and were orientated at an angle of 67 ± 20°. Of 220 cells counted, 73% aligned their cell bodies at an angle in the range of 60–120° with respect to the EVL margin; this indicates that most of these cells elongate vegetally along a line roughly perpendicular to the EVL margin, which is consistent with the direction of the epibolic movement. Similarly, the EVL cells in habvu44/vu44 mutant embryos were elongated and aligned properly (LWR = 1.79 ± 0.54; angle = 64 ± 16°C; 171 cells, 3 embryos; P > 0.05 vs. WT). In contrast, in embryos with reduced or excess Gα12/13 function, the EVL cells were significant rounder (smaller LWR; 3MO: LWR = 1.46 ± 0.32, 379 cells, 8 embryos; Gα13a: LWR = 1.55 ± 0.44, 342 cells, 8 embryos; P < 0.001 vs. control; Fig. 6, E–H). In addition, these EVL cells were more disorganized and failed to align their cell bodies along the direction of epibolic movement, with orientations of 52 ± 26° or 54 ± 25° (P < 0.001 vs. control) in Gα12/13-depleted or Gα13a-overexpressing embryos, respectively. Moreover, only 41–49% of the cells from these embryos exhibited an angle within the range of 60–120°, which suggests that most EVL cells in these embryos were oriented in random directions (Fig. 6, E–G and I–K). Interestingly, the punctate actin accumulation adjacent to the EVL margin was markedly reduced in embryos overexpressing Gα13a (Fig. 6 G; compare the yellow arrows Fig. 6, E and G). Moreover, these embryos exhibited abnormal formation of actin bundles in the YCL, although these are rarely observed in the yolk cells of WT embryos. This is possibly due to the aggregation or contraction of F-actin, which was absent in some areas of the cortical cytoplasmic layer (Fig. 6, C and G).

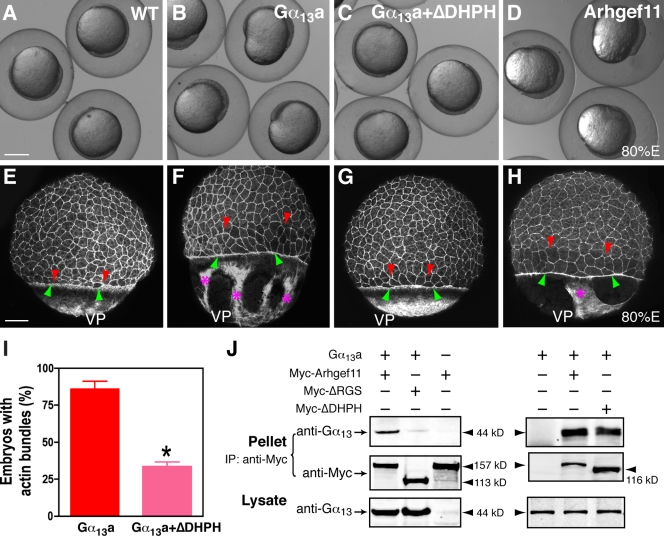

Work in mammalian systems has established that Gα12/13 regulate actin cytoskeleton dynamics to modulate cell shape and migration via a RhoGEF/Rho-dependent signaling pathway (Buhl et al., 1995; Gohla et al., 1998; Hart et al., 1998; Kozasa et al., 1998). We have shown previously that, like zebrafish Gα12/13, one of the zebrafish RhoGEFs, PDZRhoGEF (Arhgef11), can induce stress fiber formation in HEK 293 cells (Lin et al., 2005; Panizzi et al., 2007), which suggests that zebrafish Gα12/13 also function through RhoGEF to regulate actin organization. Furthermore, we showed that, when coexpressed in HEK 293 cells, Gα13a specifically coprecipitated with myc-tagged full-length Arhgef11, and this interaction was not observed when an Arhgef11 mutant lacking the RGS domain, known to be required for target binding, was coexpressed. This indicates that Gα12/13 physically interact with PDZRhoGEF via the RGS domain (Fig. 7 J).

Figure 7.

Gα13a promotes actin assembly via a PDZ RhoGEF-dependent pathway. (A–D) Nomarski images of live WT embryos (A), embryos overexpressing Gα13a alone (B), embryos overexpressing Gα13a and a dominant-negative mutant zebrafish Arhgef11, ΔDHPH (C), or embryos overexpressing Arhgef11 (D) at 80% epiboly. Bar, 250 µm. (E–H) Confocal z-projection images show phalloidin staining of F-actin. Red and green arrowheads indicate the dcm and the EVL, respectively; pink asterisks show the actin bundles in the yolk. Note the gap between dcm and the EVL, and the lack of actin bundles in embryos coinjected with Gα13a and a ΔDHPH-encoding RNA. VP, vegetal pole. Bars, 100 µm. (I) The percentage of embryos with actin bundles in the embryos expressing Gα13a alone or both Gα13a and ΔDHPH. *, P < 0.05 versus Gα13a. (J) Gα13a interacts with zebrafish Arhgef11. Coimmunoprecipitation was performed on cell extracts from HEK 293 cells transfected with Gα13a or Arhfef11 alone, or with both Gα13a and myc-tagged Arhgef11 forms (WT, dominant-negative mutants lacking the RGS domain [ΔRGS], or lacking the DH and PH domains [ΔDHPH]). Immunoblotting was performed with the indicated antibodies. Error bars represent mean ± SEM.

To determine if zebrafish Gα12/13 modulate epiboly via a RhoGEF-dependent signaling pathway, we first examined the effect of Arhgef11 overexpression on epiboly. The overexpression of Arhgef11 resulted in similar epiboly defects and distortions in the YCL, similar to those observed for Gα12/13 overexpression (Fig. 7 D and not depicted). Actin staining revealed that embryos overexpressing Arhgef11 also exhibited delayed epiboly of the deep cells and the EVL as well as the formation of thick actin bundles in the YCL (Fig. 7 H). Similar defects were observed in embryos overexpressing a constitutively activated zebrafish RhoA (data not shown). To test whether RhoGEF acts downstream of Gα12/13 in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, we coexpressed Gα13a together with a dominant-negative form of Arhgef11 lacking the DH and PH domains (ΔDHPH), which are needed for interacting with downstream proteins (Panizzi et al., 2007). We found that Arhgef11 ΔDHPH bound to Gα13 (Fig. 7 J) and suppressed both the formation of actin bundles in the YCL and the epiboly defects associated with Gα13a overexpression (Figs. 1 M and 7). Although actin bundles were found in 86 ± 5% of the embryos overexpressing Gα13a, only 33 ± 3% of the embryos coexpressing Gα13a and Arhgef11 ΔDHPH showed this phenotype (Fig. 7 I). However, we observed that coexpression of Arhgef11 ΔDHPH did not fully rescue the epibolic delay in the deep cells (Fig. 7 G), which suggests that cytoskeletal assembly regulated by Arhgef11 only partially accounts for the function of Gα12/13 in epiboly. Collectively, these results indicate that Gα12/13 can regulate epiboly through a PDZ RhoGEF/RhoA-dependent signaling pathway to modulate the function of the actin cytoskeleton.

Discussion

In this paper, we demonstrate that Gα12/13 signaling can regulate different aspects of epiboly movements by two distinct mechanisms: inhibiting E-cadherin activity and modulating actin cytoskeleton organization.

Excess or reduced Gα12/13 signaling during gastrulation resulted in delayed epiboly of the deep cells and in the splitting of the df cell cluster (Fig. 1). Moreover, excess Gα12/13 activity led to the detachment of cells from embryonic tissues, which suggests that cell adhesion is defective under these circumstances (Fig. 2). All of these phenotypic characteristics resemble those observed in hab (cdh1) mutant embryos (Kane et al., 1996; Kane and Warga, 2004), which suggests a possible link between Gα12/13 signaling and E-cadherin. Indeed, although altered Gα12/13 expression did not change the expression level and cellular distribution of E-cadherin (Fig. 3), our in vivo genetic experiments demonstrated that Gα12/13 can inhibit the function of E-cadherin. In particular, we found that a reduction in the expression of either Gα12 or Gα13 function by MO injection partially suppressed, whereas an increase in Gα13 activity exacerbated the epibolic defects in hab mutant mutants (Fig. 4). Interestingly, decreased Gα12/13 function reduced the fraction of embryos with a weak epibolic defect, as well as the fraction with a strong epibolic delay (Fig. 4). This suggests that reduced Gα12/13 function may suppress not only the epibolic defects in heterozygous embryos, but also those in homozygous mutants. We speculate that such an effect might be caused by the reduced inhibition of the maternal E-cadherin protein by Gα12/13 in homozygous mutants (Babb and Marrs, 2004; Kane et al., 2005).

Our biochemical studies support the notion that Gα12/13 can interact with E-cadherin. We showed that zebrafish Gα13a was pulled down with the CT fragment of zebrafish E-cadherin (E-cad–CyT) in HEK cells (Fig. 4), which is consistent with the physical interaction between mammalian Gα12/13 and E-cadherin shown previously (Kaplan et al., 2001; Meigs et al., 2001). The E-cad–CyT has been shown to act as a dominant-negative protein (Sadot et al., 1998). Accordingly, we observed that embryos expressing this fragment exhibited cleavage defects, and the detachment of blastodermal cells during early development and coinjection of Gα13a-RNA exacerbated these phenotypes (unpublished data). The region of E-cadherin that binds Gα12/13 was found to be located near the binding site for β-catenin (Kaplan et al., 2001). This is supported by our result showing that β-catenin can compete with Gα13 for E-cadherin binding in HEK cells (Fig. 5 B). Furthermore, it has been hypothesized that the binding of Gα12/13 to E-cadherin interferes with the ability of E-cadherin to form a complex with β-catenin. In fact, Gα12/13 overexpression can cause β-catenin to dissociate from E-cadherin and to translocate from the membrane to the cytosol in cultured cells (Meigs et al., 2001). We speculate that the competition of Gα12/13 with β-catenin for binding to E-cadherin may be one of the underlying mechanisms in embryos. However, we did not observe any overt change in expression level or intracellular distribution of β-catenin in embryos overexpressing Gα13a (Fig. 3). The reason for this discrepancy between studies in cell culture and our studies in zebrafish embryos is unclear. However, one possibility is that the levels of Gα12/13 we used were sufficient to alter E-cadherin activity but not to produce detectable changes in β-catenin distribution.

Studies from hab mutant embryos indicate that E-cadherin regulates epiboly in part by impinging on cell–cell adhesion (Warga and Kimmel, 1990; Montero et al., 2005; Shimizu et al., 2005). Considering these findings in the light of our biochemical and genetic data showing that Gα12/13 functionally interact with E-cadherin in zebrafish, we propose that Gα12/13 modulate epibolic movement by inhibiting E-cadherin–mediated cell–cell adhesion. Accordingly, cells in embryos overexpressing Gα13a during early epiboly scattered across a larger area (Fig. 5). In addition, we also demonstrated that a larger scattering area in embryos overexpressing Gα13a is not due to an increase in cell number (Fig. S2). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that other functions of Gα12/13 could contribute to reduced cohesion or abnormal cell movements.

In addition to the impaired epiboly of the deep cells, altered Gα12/13 signaling resulted in epibolic defects of the EVL (Fig. 6). This is in contrast to habvu44 and maternal-zygotic cdh1rk3 mutant embryos, in which the EVL appears to undergo normal epiboly in spite of the fact that the deep cells exhibit severe epibolic defects (Fig. 6 D; Shimizu et al., 2005). These results suggest that Gα12/13 may impinge on pathways other than the E-cadherin pathway to regulate epiboly in EVL cells. Recent evidence indicates that proper organization of the F-actin–based cytoskeleton plays critical roles in the normal epiboly of zebrafish embryos (Zalik et al., 1999; Cheng et al., 2004; Koppen et al., 2006). The actin contractile elements in the YSL are necessary for facilitating the proper EVL cell shape changes during late gastrulation (Koppen et al., 2006). Notably, in E-cadherin–deficient embryos, actin organization appeared to be normal, and EVL cells were elongated and orientated properly (Fig. 6, D and H; Shimizu et al., 2005), which indicates that E-cadherin does not play a significant role in actin organization and EVL epiboly in zebrafish.

In mammalian cultured cells, Gα12/13 are known to be involved in the regulation of actin polymerization and the maintenance of proper cell morphology, which suggests that Gα12/13 may affect EVL epiboly by regulating actin cytoskeleton organization and/or function. Although there is no significant change in the organization of filamentous actin of EVL cells in embryos with altered Gα12/13 signaling, these cells displayed defects in cell shape and orientation (Fig. 6), which may contribute to the epibolic defects of the EVL. In addition, in embryos with excess Gα12/13 signaling, the punctate F-actin ring adjacent to the EVL was significantly reduced (Fig. 6 G), and abnormal thick actin bundles, separated by F-actin–free regions, were frequently found in the yolk (Fig. 6, C and G). We speculate that the thick actin bundles may cause abnormal “contractile” forces that disrupt the YCL; alternatively, these forces may create resistance to vegetal pulling of the EVL. Altogether, the changes in actin architecture resulting from altered Gα12/13 activities could prevent the EVL from undergoing active cell rearrangement and shape changes, ultimately affecting normal EVL epiboly. In E-cadherin mutants, in contrast, the abnormal actin fibers are not observed, and thus they are unlikely to be caused by a decrease in E-cadherin function. Interestingly, although the deep cells in embryos with altered Gα12/13 signaling displayed severe defects in epiboly, they did not exhibit corresponding changes in F-actin organization and cell shape (unpublished data). This further underscores the notion that epiboly of the deep cells might involve distinct mechanisms. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that in the deep cells, Gα12/13 also influence epiboly by modulating the actin cytoskeleton. Indeed, in differentiated leukocyte-HL60, Gα12/13 were shown to influence the actomyosin network during retraction of the trailing edge (Xu et al., 2003). It will be interesting in the future to investigate how cell migration contributes to epiboly in zebrafish. Furthermore, in Xenopus laevis, it has been shown that two G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs; the phospholipid lysophosphatidic acid [LPA] receptor and Xflop) that couple to Gα12/13 in some cell types (Ishii et al., 2004) can regulate expression of a calcium-dependent EP-cadherin and modulate the assembly of cortical actin (Lloyd et al., 2005; Tao et al., 2005, 2007). Therefore, it will be important in the future to investigate if LPA functions in a similar manner in zebrafish.

In addition, we found that embryos overexpressing Gα13 exhibited microtubule organization defects similar to those observed for F-actin, showing thick bundles of microtubules surrounded by areas devoid of microtubules (Fig. S3). However, embryos with reduced Gα12/13 do not show significant defects in microtubule organization (unpublished data), which suggests that at their normal expression levels, Gα12/13 do not play an essential role in microtubule stabilization in zebrafish.

Gα12/13 are known to regulate cytoskeletal function via a Rho-dependent signaling cascade. Several observations indicate that Gα12/13 appear to operate through the same signaling pathway to regulate actin organization during EVL epiboly. First, coexpression of a dominant-negative zebrafish PDZ RhoGEF, Arhgef11, with Gα13 significantly reduced the formation of actin bundles, and suppressed the epiboly defects in the EVL (Figs. 1 M and 7). Conversely, overexpression of Arhgef11 or a constitutively active RhoA resulted in similarly abnormal actin organization in the yolk, and impaired epiboly (Fig. 7, D and H; and unpublished data). Notably, embryos expressing Arhgef11 did not exhibit the detachment of cells from the embryo surface (unpublished data), and Arhgef11 LOF did not result in obvious epiboly and C&E defects but gave rise to defects associated with ciliated epithelia (Panizzi et al., 2007). We speculate that Arhgef11 and Gα12/13 may act in both overlapping and different signaling pathways during gastrulation. These results further support the idea that Gα12/13 regulate actin organization and cell adhesion via distinct mechanisms.

In summary, our studies establish Gα12/13 as novel regulators of epiboly in zebrafish. Our data indicate that Gα12/13 may regulate different aspects of epibolic movements by two distinct pathways. In the deep cells, Gα12/13 bind the intracellular domain of E-cadherin and inhibit its activity to modulate epiboly; in the EVL and the yolk cell, Gα12/13 promote actin cytoskeleton assembly through RhoGEF/RhoA in order to regulate epibolic movement of the EVL. It has been shown that Gα12/13 can transmit signals from different GPCRs and suggested that different GPCRs may activate distinct signaling pathways through Gα12/13 (Riobo and Manning, 2005). It will be interesting to determine if zebrafish epiboly involves different extracellular signals acting through distinct GPCRs via Gα12/13 to specify distinct cell behaviors in different cell types. Gα12/13 are oncogenes with transforming potential and growth-promoting activity (Chan et al., 1993; Voyno-Yasenetskaya et al., 1994; Radhika and Dhanasekaran, 2001). Furthermore, the down-regulation of E-cadherin is associated with tumor metastasis and cancer progression (Behrens, 1999). Thus, our findings on the in vivo role of Gα12/13 in epiboly may have significant implications for the mechanisms whereby Gα12/13 function during tumorigenesis and metastasis, as well as during other morphogenetic processes in multicellular systems.

Materials and methods

Zebrafish strain and maintenance

WT, transgenic Tg[gsc:GFP] (Doitsidou et al., 2002), and habvu44 mutant strains of zebrafish were maintained as described previously (Solnica-Krezel et al., 1994). Embryos were obtained by natural mating and staged according to morphology as described previously (Kimmel et al., 1995).

Generation of a GST-tagged cytoplasmic fragment of E-cadherin

The cytoplasmic domain of zebrafish E-cadherin (708-864AA) was cloned by PCR using the cdh1 cDNA as a template (Babb et al., 2001). The GST sequence was inserted in front of the 5′ end of the fragment, and the construct was verified by sequencing and by its expression (as ascertained by immunostaining with anti-GST antibody).

mRNA and antisense MO injections, in situ hybridization

Capped sense mRNAs were synthesized using the SP6 mMessage machine (Applied Biosystems). The injection of synthetic mRNAs encoding Gα13a (60 pg), Gα13-CT (800 pg), myc-tagged PDZ RhoGEF (Arhgef11, 2pg), the dominant-negative mutant Arhgef11 (ΔDHPH, 600 pg), constitutively activated RhoA (10 pg), and antisense MOs targeting zebrafish gna12, gna13a, and gna13b transcripts (4 ng each) has been described previously (Lin et al., 2005). Whole-mount in situ hybridization using an antisense ntl RNA probe was performed as described previously (Thisse and Thisse, 1998), except that BM Purple (Roche) was used for the chromogenic reaction.

Western blotting

Embryos at 80% epiboly stage were manually deyolked and homogenized in lysis buffer (Chen et al., 2004) to prepare embryo extracts. Equal amounts of protein were used for Western blot analysis. The following primary antibodies were used: anti–E-cadherin antibody (1:10,000; Babb and Marrs, 2004), anti-Gβ antibody (1:5,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), and anti–β-catenin antibody (1:250; Sigma-Aldrich).

GST pull-down and coimmunoprecipitation assays

HEK 293 cells were transiently cotransfected with cDNAs encoding Gα13a and GST or the GST-tagged CT fragment of E-cadherin; or zebrafish Gα13a and a myc-tagged full-length Arhgef11, or myc-tagged Arhgef11 mutants lacking the RGS domain (ΔRGS) or DH and PH domains (ΔDHPH; Panizzi et al., 2007). After serum starvation overnight, cells were washed twice with serum-free medium and lysed in PBS containing 1% Igapal, 0.2% deoxycholate, and protease inhibitors. For the GST pull-down assay, protein extracts were incubated with glutathione–Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). The presence of Gα13a in the lysates and precipitate was detected by anti-Gα13 antibody (1:1,000; Lin et al., 2005). For coimmunoprecipitation of Gα13a with myc-tagged WT and mutant Arhgef11, the lysates were incubated with mouse anti-myc antibody (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) overnight at 4°C. Protein-A–Sepharose was then added for 2 h at 4°C. Immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-Gα13 (1:1,000) and anti-myc (1:1,000; Fitzgerald) antibodies to detect the presence of Gα13a and the myc-tagged proteins. Gα13 antibody was provided by D. Manning (University of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA).

Whole-mount immunostaining

Embryos were fixed at appropriate stages in 4% PFA/PBS/4% sucrose at 4°C overnight. For F-actin staining, Alexa Fluor 546 phalloidin (1:100; Invitrogen) was used as described previously (Koppen et al., 2006). In addition, the following primary antibodies were used: anti–E-cadherin (1:1,000; Babb and Marrs, 2004), anti–α-tubulin (DM1A, 1:300; EMD), and anti–α-catenin (1:250; Sigma-Aldrich). Embryos were then mounted in 75% glycerol in PBS for analysis by microscopy.

Quantification of cell shape and alignment

Confocal images of EVL cells in Phalloidin-stained embryos were collected using a 20×/0.8 NA objective lens (Carl Zeiss, Inc.). LWRs (a ratio of the longest to shortest axis of the cell) and the angle of the long axis of the cells relative to a line parallel to the EVL margin were determined using Object-Image software. The angle of the long cell axes relative to the EVL margin was plotted in a half-Rose diagram (Vector Rose; PAZ software).

Cell scattering assays in vivo

At the 256-cell stage, a single cell at the animal pole was injected with 0.5% rhodamine-dextran (Warga and Kane, 2003). Embryos were mounted on bridged slides filled with 2% methylcellulose, incubated at 28°C, and photographed every hour for 3 h to monitor the scattering of the labeled cells. To measure cell scattering, we exported the images to Object-Image. The exterior-most outlines of the labeled cells were marked and the areas encompassing the dispersed cells were calculated.

Microscopy

Live embryos for still photography were mounted in 1.5–2% methylcellulose at 28.5°C, whereas fixed embryos were mounted in 75% glycerol/PBS. Embryos were photographed using 5–20× objectives on an Axiophot2 microscope or a Stereomicroscope (Stereo Discovery V12) equipped with an Axiocam digital camera (all from Carl Zeiss, Inc.). Axiovision software was used to capture the images. Confocal images were collected on a laser scanning inverted microscope (LSM 510; Carl Zeiss, Inc.) using a 40×/1.30 NA oil objective with zoom 2 or a 20×/0.8 NA objective using the LSM 510 software. The acquired images were exported and edited using Photoshop (Adobe), and then compiled in Illustrator software (Adobe).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired Student's t tests with 2 tails, unequal variance.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows that the distribution of β-catenin and α-catenin is not changed in cells expressing Gα13a. Fig. S2 shows that Gα13a overexpression does not promote cell proliferation. Fig. S3 shows the microtubules in WT control embryos and embryos overexpressing Gα13a revealed by anti–α-tubulin staining. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200805148/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Solnica-Krezel and H.E. Hamm laboratory members for helpful discussions, Nick Echemendia for technical support, Christina Speirs for critical comments, and Christine Blaumueller for proofreading the manuscript. We acknowledge Joshua Clanton, Heidi Beck, and Amanda Bradshaw for excellent fish care. We are grateful to Dr. David Manning for the Gα13 antibody.

Confocal experiments were performed in the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Cell Imaging Core facility (supported by National Institutes of Health [NIH} grant 1S10RR015682). F. Lin is supported by the training grant EY07135-13 and NIH grant 1 K99 RR024119-01. This work was supported in part by the following NIH grants: GM77770 (to L. Solnica-Krezel), EY10291 (to H.E. Hamm), and HL60678 (to H.E. Hamm).

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: C&E, convergence and extension; cdh1, cadherin1; CT, carboxy terminal; CyT, cytoplasmic terminus; dcm, deep cell margin; df, dorsal forerunner; EVL, enveloping layer; GEF, guanine nucleotide exchange factor; GPCR, G protein–coupled receptor; hab, half-baked; LWR, length-to-width ratio; MO, morpholino oligonucleotide; ntl, no tail; WT, wild type; YCL, yolk cytoplasmic layer; YSL, yolk syncytial layer; YSN, yolk syncytial nuclei.

References

- Akhter SA, Luttrell LM, Rockman HA, Iaccarino G, Lefkowitz RJ, Koch WJ. Targeting the receptor-Gq interface to inhibit in vivo pressure overload myocardial hypertrophy. Science. 1998;280:574–577. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai K., Maruyama Y., Nishida M., Tanabe S., Takagahara S., Kozasa T., Mori Y., Nagao T., and Kurose H. Differential requirement of Gα12, Gα13, Gαq, and Gβγ for endothelin-1-induced c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2003. 63: 478–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendt D., Nubler-Jung K. 1999. Rearranging gastrulation in the name of yolk: evolution of gastrulation in yolk-rich amniote eggs.Mech. Dev. 81: 3–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babb S.G., Marrs J.A. 2004. E-cadherin regulates cell movements and tissue formation in early zebrafish embryos.Dev. Dyn. 230: 263–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babb S.G., Barnett J., Doedens A.L., Cobb N., Liu Q., Sorkin B.C., Yelick P.C., Raymond P.A., Marrs J.A. 2001. Zebrafish E-cadherin: expression during early embryogenesis and regulation during brain development.Dev. Dyn. 221: 231–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth A.I., Nathke I.S., Nelson W.J. 1997. Cadherins, catenins and APC protein: interplay between cytoskeletal complexes and signaling pathways.Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 9: 683–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens J. 1999. Cadherins and catenins: role in signal transduction and tumor progression.Cancer Metastasis Rev. 18: 15–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betchaku T., Trinkaus J.P. 1986. Programmed endocytosis during epiboly of Fundulus heteroclitus.Am. Zool. 26: 193–199 [Google Scholar]

- Buhl A.M., Johnson N.L., Dhanasekaran N., Johnson G.L. 1995. Gα12 and Gα13 stimulate Rho-dependent stress fiber formation and focal adhesion assembly.J. Biol. Chem. 270: 24631–24634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A.M., Fleming T.P., McGovern E.S., Chedid M., Miki T., Aaronson S.A. 1993. Expression cDNA cloning of a transforming gene encoding the wild-type Gα12 gene product.Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 762–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Dell E.J., Lin F., Sai J., Hamm H.E. 2004. RACK1 regulates specific functions of Gβγ.J. Biol. Chem. 279: 17861–17868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J.C., Miller A.L., Webb S.E. 2004. Organization and function of microfilaments during late epiboly in zebrafish embryos.Dev. Dyn. 231: 313–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M.S., D'Amico L.A. 1996. A cluster of noninvoluting endocytic cells at the margin of the zebrafish blastoderm marks the site of embryonic shield formation.Dev. Biol. 180: 184–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doitsidou M., Reichman-Fried M., Stebler J., Koprunner M., Dorries J., Meyer D., Esguerra C.V., Leung T., Raz E. 2002. Guidance of primordial germ cell migration by the chemokine SDF-1.Cell. 111: 647–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist A., Bunemann M., Li A., Hosey M.M., Hamm H.E. 1999. A dominant-negative strategy for studying roles of G proteins in vivo.J. Biol. Chem. 274: 6610–6616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohla A., Harhammer R., Schultz G. 1998. The G-protein Gα13 but not Gα12 mediates signaling from lysophosphatidic acid receptor via epidermal growth factor receptor to Rho.J. Biol. Chem. 273: 4653–4659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbleib J.M., Nelson W.J. 2006. Cadherins in development: cell adhesion, sorting, and tissue morphogenesis.Genes Dev. 20: 3199–3214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart M.J., Jiang X., Kozasa T., Roscoe W., Singer W.D., Gilman A.G., Sternweis P.C., Bollag G. 1998. Direct stimulation of the guanine nucleotide exchange activity of p115 RhoGEF by Gα13.Science. 280: 2112–2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu H.J., Liang M.R., Chen C.T., Chung B.C. 2006. Pregnenolone stabilizes microtubules and promotes zebrafish embryonic cell movement.Nature. 439: 480–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inbal A., Topczewski J., Solnica-Krezel L. 2006. Targeted gene expression in the zebrafish prechordal plate.Genesis. 44: 584–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii I., Fukushima N., Ye X., Chun J. 2004. Lysophospholipid receptors: signaling and biology.Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73: 321–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane D.A., Warga R.M. 2004. Teleost gastrulation. Gastrulation: From Cells to Embryos. Stern C.D., editor Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 157–169 [Google Scholar]

- Kane D.A., Hammerschmidt M., Mullins M.C., Maischein H.M., Brand M., van Eeden F.J., Furutani-Seiki M., Granato M., Haffter P., Heisenberg C.P., et al. 1996. The zebrafish epiboly mutants.Development. 123: 47–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane D.A., McFarland K.N., Warga R.M. 2005. Mutations in half baked/E-cadherin block cell behaviors that are necessary for teleost epiboly.Development. 132: 1105–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan D.D., Meigs T.E., Casey P.J. 2001. Distinct regions of the cadherin cytoplasmic domain are essential for functional interaction with Gα12 and β-catenin.J. Biol. Chem. 276: 44037–44043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel C.B., Ballard W.W., Kimmel S.R., Ullmann B., Schilling T.F. 1995. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish.Dev. Dyn. 203: 253–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppen M., Fernandez B.G., Carvalho L., Jacinto A., Heisenberg C.P. 2006. Coordinated cell-shape changes control epithelial movement in zebrafish and Drosophila.Development. 133: 2671–2681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozasa T., Jiang X., Hart M.J., Sternweis P.M., Singer W.D., Gilman A.G., Bollag G., Sternweis P.C. 1998. p115 RhoGEF, a GTPase activating protein for Gα12 and Gα13.Science. 280: 2109–2111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachnit M., Kur E., Driever W. 2008. Alterations of the cytoskeleton in all three embryonic lineages contribute to the epiboly defect of Pou5f1/Oct4 deficient MZspg zebrafish embryos.Dev. Biol. 315: 1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leptin M. 2005. Gastrulation movements: the logic and the nuts and bolts.Dev. Cell. 8: 305–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F., Sepich D.S., Chen S., Topczewski J., Yin C., Solnica-Krezel L., Hamm H. 2005. Essential roles of Gα12/13 signaling in distinct cell behaviors driving zebrafish convergence and extension gastrulation movements.J. Cell Biol. 169: 777–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd B., Tao Q., Lang S., Wylie C. 2005. Lysophosphatidic acid signaling controls cortical actin assembly and cytoarchitecture in Xenopus embryos.Development. 132: 805–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland K.N., Warga R.M., Kane D.A. 2005. Genetic locus half baked is necessary for morphogenesis of the ectoderm.Dev. Dyn. 233: 390–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meigs T.E., Fields T.A., McKee D.D., Casey P.J. 2001. Interaction of Gα12 and Gα13 with the cytoplasmic domain of cadherin provides a mechanism for beta -catenin release.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98: 519–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meigs T.E., Fedor-Chaiken M., Kaplan D.D., Brackenbury R., Casey P.J. 2002. Gα12 and Gα13 negatively regulate the adhesive functions of cadherin.J. Biol. Chem. 277: 24594–24600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero J.A., Carvalho L., Wilsch-Brauninger M., Kilian B., Mustafa C., Heisenberg C.P. 2005. Shield formation at the onset of zebrafish gastrulation.Development. 132: 1187–1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panizzi J.R., Jessen J.R., Drummond I.A., Solnica-Krezel L. 2007. New functions for a vertebrate Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor in ciliated epithelia.Development. 134: 921–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhika V., Dhanasekaran N. 2001. Transforming G proteins.Oncogene. 20: 1607–1614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riobo N.A., Manning D.R. 2005. Receptors coupled to heterotrimeric G proteins of the Gα12 family.Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 26: 146–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde L.A., Heisenberg C.P. 2007. Zebrafish gastrulation: cell movements, signals, and mechanisms.Int. Rev. Cytol. 261: 159–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadot E., Simcha I., Shtutman M., Ben-Ze'ev A., Geiger B. 1998. Inhibition of beta-catenin-mediated transactivation by cadherin derivatives.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95: 15339–15344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte-Merker S., van Eeden F.J., Halpern M.E., Kimmel C.B., Nusslein-Volhard C. 1994. no tail (ntl) is the zebrafish homologue of the mouse T (Brachyury) gene.Development. 120: 1009–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T., Yabe T., Muraoka O., Yonemura S., Aramaki S., Hatta K., Bae Y.K., Nojima H., Hibi M. 2005. E-cadherin is required for gastrulation cell movements in zebrafish.Mech. Dev. 122: 747–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solnica-Krezel L. 2005. Conserved patterns of cell movements during vertebrate gastrulation.Curr. Biol. 15: R213–R228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solnica-Krezel L. 2006. Gastrulation in zebrafish–all just about adhesion? Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 16: 433–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solnica-Krezel L., Driever W. 1994. Microtubule arrays of the zebrafish yolk cell: organization and function during epiboly.Development. 120: 2443–2455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solnica-Krezel L., Schier A.F., Driever W. 1994. Efficient recovery of ENU-induced mutations from the zebrafish germline.Genetics. 136: 1401–1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahle U., Jesuthasan S. 1993. Ultraviolet irradiation impairs epiboly in zebrafish embryos: evidence for a microtubule-dependent mechanism of epiboly.Development. 119: 909–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Q., Lloyd B., Lang S., Houston D., Zorn A., Wylie C. 2005. A novel G protein-coupled receptor, related to GPR4, is required for assembly of the cortical actin skeleton in early Xenopus embryos.Development. 132: 2825–2836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Q., Nandadasa S., McCrea P.D., Heasman J., Wylie C. 2007. G-protein-coupled signals control cortical actin assembly by controlling cadherin expression in the early Xenopus embryo.Development. 134: 2651–2661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse C., Thisse B. 1998. High resolution whole-mount in situ hybridization.The Zebrafish Science Monitor. 5: 8–9 [Google Scholar]

- Trinkaus J.P. 1951. A study of the mechanism of epiboly in the egg of Fundulus heteroclitus.J. Exp. Zool. 118: 269–320 [Google Scholar]

- Trinkaus J.P. 1984. Mechanism of Fundulus epiboly: A current view.Am. Zool. 24: 673–688 [Google Scholar]

- Trinkaus J.P. 1993. The yolk syncytial layer of Fundulus: its origin and history and its significance for early embryogenesis.J. Exp. Zool. 265: 258–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voyno-Yasenetskaya T.A., Pace A.M., Bourne H.R. 1994. Mutant α subunits of G12 and G13 proteins induce neoplastic transformation of Rat-1 fibroblasts.Oncogene. 9: 2559–2565 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warga R.M., Kimmel C.B. 1990. Cell movements during epiboly and gastrulation in zebrafish.Development. 108: 569–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warga R.M., Kane D.A. 2003. One-eyed pinhead regulates cell motility independent of Squint/Cyclops signaling.Dev. Biol. 261: 391–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins S.J., Yoong S., Verkade H., Mizoguchi T., Plowman S.J., Hancock J.F., Kikuchi Y., Heath J.K., Perkins A.C. 2008. Mtx2 directs zebrafish morphogenetic movements during epiboly by regulating microfilament formation.Dev. Biol. 314: 12–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Wang F., Van Keymeulen A., Herzmark P., Straight A., Kelly K., Takuwa Y., Sugimoto N., Mitchison T., Bourne H.R. 2003. Divergent signals and cytoskeletal assemblies regulate self-organizing polarity in neutrophils.Cell. 114: 201–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalik S.E., Lewandowski E., Kam Z., Geiger B. 1999. Cell adhesion and the actin cytoskeleton of the enveloping layer in the zebrafish embryo during epiboly.Biochem. Cell Biol. 77: 527–542 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]