Abstract

Laterally spreading tumors (LSTs) are considered a special subtype of superficial colorectal tumor. This study was performed to characterize the clinicopathological features and examine activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in LSTs and protruded-type colorectal adenomas (PAs). Fifty LSTs and 54 PAs were collected, and their clinicopathological characteristics were compared. The expression of E-cadherin, β-catenin, glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), phosphorylated GSK-3β, (phospho-GSK-3β), cyclin D1, and c-myc was investigated by immunohistochemical staining on serial sections. Patients with LSTs were significantly older than those bearing PAs (63.4 vs 47.4 years old; p<0.001). The mean size of LSTs was significantly larger than that of PAs (27.0 mm vs 14.6 mm; p<0.01). Forty-eight percent of LSTs were located in the proximal colon, which was significantly higher than that of PAs (18.5%; p<0.05). Expression of β-catenin, phospho-GSK-3β, cyclin D1, and c-myc was significantly increased in LSTs compared with PAs (p<0.05). However, E-cadherin and total GSK-3β expression was not significantly different between the two groups. The level of β-catenin expression correlated strongly with phospho-GSK-3β, cyclin D1, and c-myc expression in LSTs but not in PAs. Our findings suggest that activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is more prevalent in LSTs than in PAs, suggesting that phosphorylation-dependent inactivation of GSK-3β may be involved in LST carcinogenesis. (J Histochem Cytochem 57:363–371, 2009)

Keywords: laterally spreading colorectal tumor, carcinogenesis, Wnt/β-catenin pathway, GSK-3β, phosphorylation

Colorectal tumors can be divided into two groups on the basis of their morphological characteristics: protruded-type tumors and flat-type tumors (Takahashi et al. 2007). The process of carcinogenesis for protruded-type tumors is based on the concept of “adenoma-carcinoma sequence” and follows a multistep genetic model (Fearon and Vogelstein 1990). However, the flat-type colorectal tumors, including laterally spreading colorectal tumors (LSTs), are believed to have distinct histological and genetic characteristics (Mueller et al. 2002). LSTs are defined as lesions >10 mm in diameter with a low vertical axis, which extend laterally along the interior luminal wall (Kudo 1993). Because its superficial growth pattern and biological behaviors are different from protruded-type colorectal adenomas (PAs), LSTs have received significant attention from researchers, and an increasing number of studies on LSTs have been reported (Ohno et al. 2001; Hurlstone et al. 2002). However, the majority of studies on LSTs have focused on endoscopic diagnosis and therapy (Tamura et al. 2004; Fujishiro et al. 2006). Only a few reports (Hiraoka et al. 2006; Mikami et al. 2006; Hashimoto et al. 2007) have studied the epigenetic and genetic characteristics of LSTs.

It is widely accepted that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays an important role in colorectal tumorigenesis (Clevers 2004; Fodde and Brabletz 2007). Activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway has been reported in colorectal tumors (Fodde et al. 2001; Chiang et al. 2002; van de Wetering et al. 2002). These reports suggest that transactivation of T cell factor (TCF) target genes induced by the Wnt/β-catenin pathway constitute the primary transforming events in colorectal cancer. However, the role of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in LSTs is still unclear. Hashimoto et al. (2007) reported that flat segments of LSTs showed higher expression of β-catenin in the nucleus. Similarly, Mikami et al. (2006) detected cytoplasmic expression of β-catenin in a higher percentage of flat-type tumors with depressed areas than in tumors without depressed areas (11/17, 64.7% vs 147/293, 50.2%), although this difference was not statistically significant. These findings suggest that a higher level of β-catenin expression may play an important role in LSTs. However, research regarding the activation of other key molecules in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in LSTs is lacking, and the regulatory mechanisms of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway are unclear.

β-Catenin has two main functions. It is a structural adaptor protein that links cadherin to the actin cytoskeleton; thus, it plays an important role in cell–cell adhesion. It is also a transcription factor acting downstream of the Wnt signaling cascade (Segditsas and Tomlinson 2006). In the absence of extracellular Wnt stimulation, the intracellular level of β-catenin is kept low through phosphorylation-mediated destabilization. As a result, the downstream transcriptional factor TCF is repressed. Degradation of cytoplasmic β-catenin is mediated by a multiprotein complex consisting of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), axis inhibitor (AXIN), and adenomatous polyposis coli (APC). This multiprotein complex binds and phosphorylates β-catenin, thus targeting it for proteasomal degradation. After Wnt stimulation, the AXIN-GSK-3β-APC complex is inhibited. β-catenin accumulates in the cytoplasm and then translocates to the nucleus. In the nucleus, β-catenin binds to the TCF/lymphoid enhancer factor (LEF) family of transcription factors to coactivate Wnt target genes (Giles et al. 2003), including cyclin D1 and c-myc. Activation of cyclin D1 and c-myc underlies tumorigenesis. Mutations in APC, AXIN, or β-catenin genes, or phosphorylation of GSK-3β (GSK-3βser9 or phospho-GSK-3β, the inactivated form of GSK-3β) removes the negative regulatory mechanisms for β-catenin, resulting in β-catenin accumulation in the cytoplasm and translocation to the nucleus. This translocation results in the expression of oncogenic genes (Giles et al. 2003; Shakoori et al. 2005). Previous studies reported that up to 85% of all sporadic colorectal cancers have mutations in APC (Giles et al. 2003), which is the main cause of β-catenin activation in colorectal cancers. Nevertheless, the exact regulatory mechanisms behind β-catenin accumulation in LSTs are still unclear.

In this study, we investigated the clinical histopathological characteristics of 50 LSTs and 54 PAs and examined the expression of a series of key factors in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by immunohistochemistry. The goal was to elucidate the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and its potential regulatory mechanisms in LSTs.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Specimens

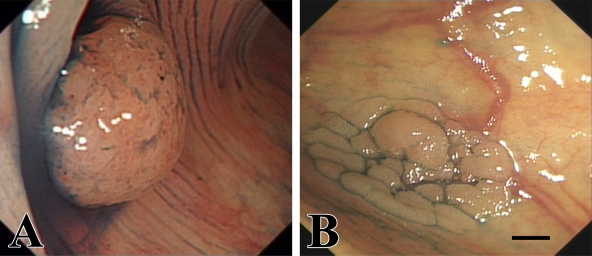

A total of 104 colorectal tumors were collected from individuals who underwent endoscopic resection under total colonoscopy at Nanfang Hospital from July 2005 to December 2007. The specimens consisted of 50 LSTs and 54 PAs. Figure 1 shows examples of endoscopic images of PAs and LSTs. Tissues from patients with inflammatory bowel disease, a known history of familial adenomatous polyposis, or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer were excluded from this analysis. The study was performed in accordance with institutional ethical guidelines and was approved by the Scientific Committee of Nanfang Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic images of protruded-type colorectal adenoma (A) and laterally spreading colorectal tumor (B). Bar = 4 mm.

The specimens were fixed in 10% formalin solution and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections (4 μm) were cut and prepared for hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining and immunohistochemistry. All HE-stained sections were reviewed by two experienced pathologists independently, who defined the tumor type and histological grade of all lesions. The following factors were determined for all patients: age, gender, tumor size, tumor location (proximal colon, distal colon, or rectum), tumor histology (tubular, tubulovillous, or villotubular), and grade of intraepithelial neoplasia (low-grade, LGIN or high-grade, HGIN).

Immunohistochemistry

Serial sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in graded ethanol. Antigen retrieval was performed by microwaving at moderate power for 3 min, then high power for 10 min in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubation with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 20 min, followed by incubation with 10% normal non-immune goat serum for 30 min to block nonspecific binding of secondary antibodies. Subsequently, sections were incubated with primary antibodies in appropriate dilutions overnight at 4C (E-cadherin antibody: cat #4065, Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA, 1:50 dilution; β-catenin antibody: cat #9562, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:200 dilution; GSK-3β antibody: cat #9315, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:100 dilution; phospho-GSK-3β antibody: cat #9336, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:50 dilution; cyclin D1 antibody: cat #2978, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:50 dilution; c-myc antibody: cat #554205, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, 1:200 dilution). After three washes with PBST (2000 ml PBS + 4 ml Tween 20), the sections were incubated with biotin-conjugated second antibody for 10 min, and then incubated with streptavidin-peroxidase for 10 min. 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine was used as the chromogen. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, mounted on slides, and coverslipped (Mukawa et al. 2005). For negative controls, according to different primary antibodies, normal rabbit or mouse serum was added instead of the primary antibody. Normal-appearing epithelium and glands in each section provided positive internal controls for binding of the primary antibodies.

Immunohistochemical Evaluation

All sections were blindly and independently assessed microscopically by two well-trained pathologists. Both the intensity and distribution of immunohistochemical staining of Wnt pathway proteins were evaluated (Qiao et al. 2001), and the staining of the membrane, cytoplasm, and nucleus was assessed separately. The intensity of staining was assessed with a semiquantitative scoring system as follows: 0, negative staining; 1, weak staining; 2, moderate staining; 3, strong staining. The distribution of staining was graded by the percentage of stained cells in the region of interest: 0, positive cells were less than 10% of tumor cells; 1, positive cells were 10–50% of tumor cells; 2, positive cells were 50–75% of tumor cells; 3, positive cells were more than 75% of tumor cells. An overall score was obtained as the product of the intensity and distribution of positive staining. Cases with 0 points were considered to be negative (0), cases with a final score of 1–3 as weakly positive (1+), cases with a final score of 4–7 as moderately positive (2+), and cases with a final score of >7 as strongly positive (3+).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 13.0 (The Predictive Analytics Company; Chicago, IL). To test the significance of differences in clinicopathological parameters between groups, Student's t-test was used for age and sex, and the χ2 test and the Mann-Whitney U test were used for the remaining parameters (Konishi et al. 2006). Correlations between the expression of Wnt pathway proteins (immunohistochemical scores) with clinicopathological parameters were evaluated by the Spearman rank-order correlation coefficient (Bravou et al. 2006). All ranking tests were performed with correction for ties. The significance level was defined as p<0.05.

Results

Clinical and Histopathological Features

The clinicopathological features of LSTs and PAs are summarized in Table 1. No significant difference was found in gender, tumor histology, and grade of intraepithelial neoplasia between LSTs and PAs (p>0.05). The mean age of patients bearing PAs was 47.4 ± 14.4 years, whereas those with LSTs had a mean age of 63.4 ± 9.7 years (p<0.001). In regard to the tumor size, PAs ranged from 3 mm to 30 mm with a mean of 14.6 ± 9.0 mm, whereas LSTs ranged from 10 mm to 75 mm with a mean of 27.0 ± 17.1 mm (p<0.01). Forty-eight percent (24/50) of LSTs were located in the proximal colon. However, only 10/54 (18.5%) of PAs were located there (p<0.05). On the other hand, PAs were found more frequently in the distal colon (31/54, 57.4%), whereas only 8/50 (16.0%) of LSTs were located there (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic features of protruded-type adenomas and laterally spreading tumors

| PAs (n=54) | LSTs (n=50) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) mean ± SD (range)a | 47.4 ± 14.4 (25–75) | 63.4 ± 9.7 (45–77) |

| Male/femaled | 35/19 | 30/20 |

| Tumor size (mm) mean ± SD (range)b | 14.6 ± 9.0 (3–30) | 27.0 ± 17.1 (10–75) |

| Location | ||

| Proximal colonc | 10 (18.5%) | 24 (48.0%) |

| Distal colona | 31 (57.4%) | 8 (16.0%) |

| Rectumd | 13 (24.1%) | 18 (36.0%) |

| Tumor histologyd | ||

| Tubular | 19 (35.2%) | 17 (34.0%) |

| Tubulovillous | 15 (27.8%) | 22 (44.0%) |

| Villotubular | 20 (37.0%) | 11 (22.0%) |

| Grade of intraepithelial neoplasiad | ||

| Low grade | 37 (68.5%) | 29 (58.0%) |

| High grade | 17 (31.5%) | 21 (42.0%) |

p<0.001.

p<0.01.

p<0.005.

No significant difference between PAs and LSTs.

LST, laterally spreading tumor; PA, protruded-type adenoma. Proximal colon includes cecum, ascending colon, and transverse colon; distal colon includes descending colon and sigmoid colon.

Immunohistochemical Data

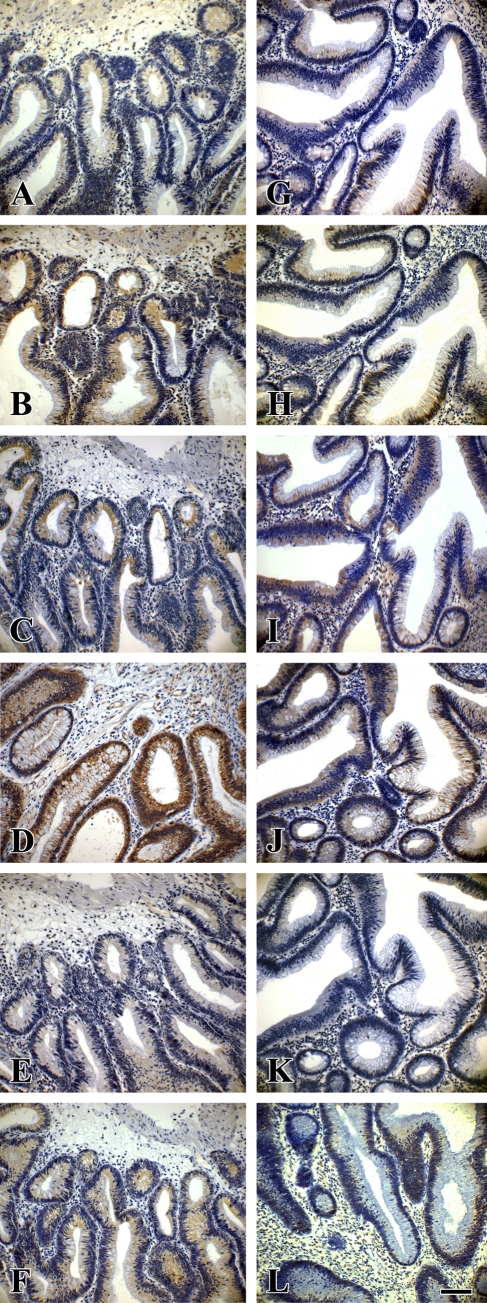

As shown in Figures 2–4, expression levels of β-catenin, phospho-GSK-3β, cyclin D1, and c-myc were significantly higher in LSTs than in PAs (Tables 2–4), especially when compared in the same grade of intraepithelial neoplasia.

Figure 2.

Expression of Wnt pathway proteins in serial sections of a laterally spreading colorectal tumor with low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (LST-LGIN) and a protruded-type colorectal adenoma with low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (PA-LGIN). (A,G) E-cadherin. (B,H) Phosphorylated GSK-3β (phospho-GSK-3β). (C,I) Total GSK-3β. (D,J) β-Catenin. (E,K) Cyclin D1. (F,L) c-myc. (A–F) From LST-LGIN. (G–L) From PA-LGIN. Bar = 45 μm.

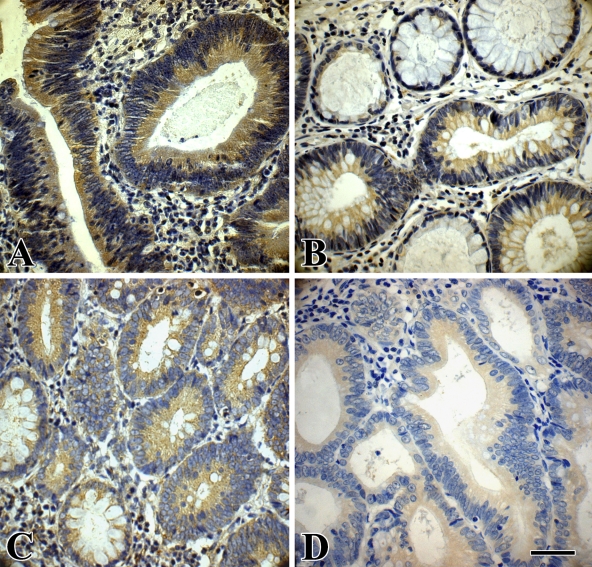

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical staining of phospho-GSK-3β and β-catenin in an LST and a PA. (A) Cytoplasmic expression of phospho-GSK-3β in an LST-LGIN. (B) Cytoplasmic expression of phospho-GSK-3β in a PA-LGIN; the adjacent normal glands show no staining. (C) Cytoplasmic expression of β-catenin in an LST-LGIN; the adjacent normal glands in the lower-left corner show membranous location of this protein. (D) Cytoplasmic expression of β-catenin in a PA-LGIN. Bar = 55 μm.

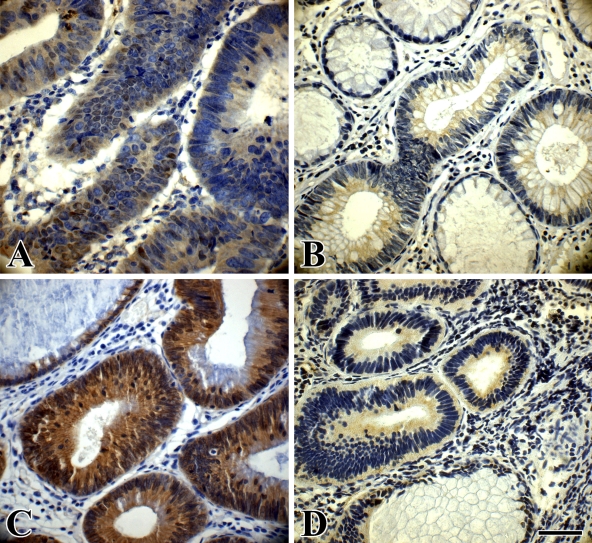

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical staining of cyclin D1 and c-myc in an LST and a PA. (A) Cytoplasmic expression of cyclin D1 in an LST-LGIN. Nuclei of some of the tumor cells also show cyclin D1 expression. (B) Cytoplasmic expression of cyclin D1 in a PA-LGIN; the adjacent normal glands show no staining. (C) Clear cytoplasmic expression of c-myc in an LST-LGIN; the adjacent normal gland shows no staining. (D) Cytoplasmic expression of c-myc in a PA-LGIN; the adjacent normal gland shows no staining. Bar = 55 μm.

Table 2.

Expression of E-cadherin and β-catenin localized to the cytoplasm in PAs and LSTs

| E-cadherin

|

β-Catenin

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 0 | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | p | n | 0 | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | p | |

| LST | 50 | 19 | 11 | 16 | 4 | 0.234a | 50 | 5 | 9 | 21 | 15 | 0.012a |

| LGIN | 29 | 12 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 0.393b | 29 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 4 | 0.032b |

| HGIN | 21 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 0.622c | 21 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 11 | 0.024c |

| PA | 54 | 25 | 15 | 10 | 4 | 54 | 12 | 20 | 16 | 6 | ||

| LGIN | 37 | 17 | 13 | 5 | 2 | 37 | 9 | 15 | 10 | 3 | ||

| HGIN | 17 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 3 | ||

LSTs vs PAs.

LSTs-LGIN vs PAs-LGIN.

LSTs-HGIN vs PAs-HGIN.

Correlation with grade of intraepithelial neoplasia. LGIN, low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia; HGIN, high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia.

Table 3.

Expression of GSK-3β and phospho-GSK-3β localized to the cytoplasm in PAs and LSTs

| GSK-3β

|

Phospho-GSK-3β

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 0 | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | p | n | 0 | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | p | |

| LST | 50 | 12 | 26 | 8 | 4 | 0.101a | 50 | 9 | 14 | 19 | 8 | 0.001a |

| LGIN | 29 | 8 | 16 | 4 | 1 | 0.019b | 29 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 2 | 0.036b |

| HGIN | 21 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 3 | 0.432c | 21 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 0.007c |

| PA | 54 | 26 | 15 | 7 | 6 | 54 | 24 | 17 | 10 | 3 | ||

| LGIN | 37 | 22 | 11 | 3 | 1 | 37 | 18 | 11 | 6 | 2 | ||

| HGIN | 17 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 17 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 1 | ||

LSTs vs PAs.

LSTs-LGIN vs PAs-LGIN.

LSTs-HGIN vs PAs-HGIN.

Correlation with grade of intraepithelial neoplasia. LGIN, low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia; HGIN, high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia.

Table 4.

Expression of cyclin D1 and c-myc localized to the cytoplasm in PAs and LSTs

| Cyclin D1

|

c-myc

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 0 | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | p | n | 0 | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | p | |

| LST | 50 | 14 | 20 | 11 | 5 | 0.023a | 50 | 21 | 15 | 7 | 7 | 0.025a |

| LGIN | 29 | 9 | 15 | 4 | 1 | 0.002b | 29 | 17 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 0.019b |

| HGIN | 21 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 0.626c | 21 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 0.879c |

| PA | 54 | 29 | 13 | 8 | 4 | 54 | 35 | 10 | 5 | 4 | ||

| LGIN | 37 | 26 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 37 | 31 | 5 | 1 | 0 | ||

| HGIN | 17 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 17 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | ||

LSTs vs PAs.

LSTs-LGIN vs PAs-LGIN.

LSTs-HGIN vs PAs-HGIN.

Correlation with grade of intraepithelial neoplasia. LGIN, low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia; HGIN, high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia.

Immunoreactivity of β-catenin was found in the cytoplasm of LST and PA colorectal tumor cells (Figures 3C and 3D). The expression levels of β-catenin were significantly higher in LSTs than in PAs (p<0.05). In addition, β-catenin expression was higher in LSTs-LGIN than in PAs-LGIN (p<0.05). Expression was also higher in LSTs-HGIN compared with PAs-HGIN (p<0.05). Moreover, weak nuclear expression of β-catenin was found in 13 LSTs but only in 4 PAs (13/50, 26.0% vs 4/54, 7.4%; p<0.01).

E-cadherin is a well-characterized cell–cell adhesion molecule that anchors to the cell membrane. The cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin is associated with β-catenin. The cytoplasmic expression of E-cadherin was not significantly different between LSTs (31/50, 62.0%) and PAs (29/54, 53.7%; p>0.05).

Immunoreactivity of phospho-GSK-3β was found in the cytoplasm of both LST and PA colorectal tumor cells (Figures 3A and 3B). The expression levels of phospho-GSK-3β were significantly increased in LSTs compared with PAs (p<0.005). In addition, phospho-GSK-3β expression was significantly higher in LSTs-LGIN than in PAs-LGIN (p<0.05). It was also higher in LSTs-HGIN compared with PAs-HGIN (p<0.01). In regard to total GSK-3β expression, there was no significant difference between LSTs and PAs (p>0.05).

Immunoreactivity of cyclin D1 and c-myc was found in the cytoplasm and the nucleus of LST and PA colorectal tumor cells (Figure 4). The expression levels of cyclin D1 and c-myc were higher in LSTs than in PAs (p<0.05, Table 4). Expression of cyclin D1 and c-myc was also stronger in LSTs-LGIN than in PAs-LGIN (p<0.005 for cyclin D1 and p<0.05 for c-myc), but there was no significant difference between LSTs-HGIN and PAs-HGIN. Moreover, nuclear localization of cyclin D1 was found in 22 LSTs but only in 7 PAs (22/50, 44.0% vs 7/54, 13.0%; p<0.005). Nuclear localization of c-myc was found in 13 LSTs but only in 5 PAs (13/50, 26.0% vs 5/54, 9.3%; p<0.05).

Expression of the key molecules in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway was compared between LSTs-LGIN and LSTs-HGIN, and between PAs-LGIN and PAs-HGIN. The expression levels of β-catenin, phospho-GSK-3β, cyclin D1, and c-myc were significantly increased in LSTs-HGIN compared with those in LSTs-LGIN (p<0.05 for β-catenin, phospho-GSK-3β, and cyclin D1; p<0.01 for c-myc). The expression levels of β-catenin and phospho-GSK-3β were not significantly different between PAs-LGIN and PAs-HGIN (p>0.05). However, the expression levels of cyclin D1 and c-myc were significantly higher in PAs-HGIN than in PAs-LGIN (p<0.001).

To observe the impact of age on molecular expression, we compared the Wnt/β-catenin pathway expression between PAs and LSTs at a series of age stratification. We found that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway expression in LSTs was indeed stronger than that in PAs, especially for β-catenin, cyclin D1, and phospho-GSK-3β and was not age related (data not shown).

Correlation of β-Catenin Accumulation With Expression of Phospho-GSK-3β, Cyclin D1, and c-myc

Correlations between cytoplasmic β-catenin levels and other key molecules in the Wnt signaling pathway were analyzed. In LSTs, cytoplasmic accumulation of β-catenin was significantly correlated with increased cytoplasmic expression of phospho-GSK-3β (rs = 0.405, p<0.005), cyclin D1 (rs = 0.479, p<0.001), and c-myc (rs = 0.373, p<0.01). However, it was not correlated with cytoplasmic expression of total GSK-3β (rs = 0.113, p>0.05) (Table 5). In PAs, cytoplasmic accumulation of β-catenin was not correlated with cytoplasmic expression of phospho-GSK-3β (rs = 0.212, p>0.05) but was correlated with cytoplasmic expression of total GSK-3β (rs = 0.314, p<0.05), cyclin D1 (rs = 0.281, p<0.05), and c-myc (rs = 0.596, p<0.001) (Table 6). Correlations of nuclear β-catenin with other key molecules in the Wnt pathway were not analyzed, owing to lower levels of nuclear expression.

Table 5.

Correlation of β-catenin expression with GSK-3β, phospho-GSK-3β, cyclin D1, and c-myc cytoplasmic expression in LSTs

| β-Catenin

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | rs | p | ||

| GSK-3β | 0 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0.113 | 0.433a |

| 1+ | 0 | 3 | 10 | 13 | |||

| 2+ | 0 | 1 | 7 | 0 | |||

| 3+ | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |||

| Phospho-GSK-3β | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0.405 | 0.003b |

| 1+ | 1 | 3 | 8 | 2 | |||

| 2+ | 1 | 2 | 10 | 6 | |||

| 3+ | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | |||

| Cyclin D1 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0.479 | 0.000c |

| 1+ | 0 | 5 | 7 | 8 | |||

| 2+ | 0 | 1 | 4 | 6 | |||

| 3+ | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | |||

| c-myc | 0 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 0.373 | 0.008d |

| 1+ | 0 | 2 | 11 | 2 | |||

| 2+ | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |||

| 3+ | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | |||

β-Catenin vs GSK-3β.

β-Catenin vs phospho-GSK-3β.

β-Catenin vs cyclin D1.

β-Catenin vs c-myc.

Table 6.

Correlation of β-catenin expression with GSK-3β, phospho-GSK-3β, cyclin D1, and c-myc cytoplasmic expression in PAs

| β-Catenin

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | rs | p | ||

| GSK-3β | 0 | 5 | 15 | 5 | 1 | 0.314 | 0.021a |

| 1+ | 6 | 2 | 6 | 1 | |||

| 2+ | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | |||

| 3+ | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Phospho-GSK-3β | 0 | 6 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 0.212 | 0.124b |

| 1+ | 2 | 4 | 7 | 4 | |||

| 2+ | 4 | 0 | 6 | 0 | |||

| 3+ | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Cyclin D1 | 0 | 7 | 15 | 6 | 1 | 0.281 | 0.039c |

| 1+ | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 | |||

| 2+ | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | |||

| 3+ | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |||

| c-myc | 0 | 12 | 15 | 8 | 0 | 0.596 | 0.000d |

| 1+ | 0 | 3 | 5 | 2 | |||

| 2+ | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||

| 3+ | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |||

β-Catenin vs GSK-3β.

β-Catenin vs phospho-GSK-3β.

β-Catenin vs cyclin D1.

β-Catenin vs c-myc.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that LSTs are located more frequently in the proximal colon and are larger than PAs. These findings are consistent with previous reports (Tanaka et al. 2001; Kim et al. 2003; Abe et al. 2006), suggesting that LSTs indeed have distinct biological characteristics compared with PAs. Gastroenterologists should be aware of these characteristics to avoid misdiagnosis under colonoscopy. We did our best to eliminate sample error, and an expert statistician determined that all of our results are credible. However, sample error cannot be completely eliminated in any experiment. Currently, there is no definitive conclusion on the malignant potential of LSTs compared with that of PAs. Further evidence must be obtained from experiments using a larger sample.

To estimate the changes of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in LSTs and PAs, we examined the expression of E-cadherin, β-catenin, total GSK-3β, phospho-GSK-3β, cyclin D1, and c-myc by immunohistochemical staining on serial sections of tumor tissues. The central player of the Wnt signaling pathway is β-catenin. Accumulation of β-catenin within the cytoplasm and nucleus is associated with colorectal cancers as well as other types of cancers. We find that cytoplasmic expression of the β-catenin family is significantly higher in LSTs than in PAs, especially when compared within the same grade of intraepithelial neoplasia. Meanwhile, β-catenin expression is significantly higher in LSTs-HGIN versus LSTs-LGIN. On the other hand, no difference in β-catenin expression is found between PAs-HGIN and PAs-LGIN. Koga et al. (2008) demonstrated that nuclear immunoreactivity for β-catenin increased significantly in flat-type colorectal tumors compared with PAs. In addition, Qiao et al. (2001) reported a significant correlation between increased cytoplasmic expression of β-catenin and a 1-year survival rate, suggesting that cytoplasmic expression of β-catenin may be a bad prognostic factor and might represent higher malignant potential (Yamada et al. 2000; Anderson et al. 2002; Sena et al. 2006). Our data are consistent with previous reports and support the hypothesis that LSTs, as a type of precancerous lesion, may have higher malignancy than PAs (Teixeira et al. 1996).

Intracellular levels of β-catenin are regulated by a “destruction multiprotein complex” consisting GSK-3β, AXIN, and APC. Phosphorylation of GSK-3βser9 leads to inhibition of the destruction complex and the consequent stabilization of β-catenin. We find that the expression of phospho-GSK-3β is significantly increased in LSTs compared with PAs. In addition, phospho-GSK-3β expression is significantly higher in LSTs-LGIN versus PAs-LGIN and is also present in higher levels in LSTs-HGIN than in PAs-HGIN. However, expression of total GSK-3β is not different between LSTs and PAs. On the basis of these results, increased expression of phospho-GSK-3β might be one of the underlying factors for elevated cytoplasmic levels of β-catenin in LSTs.

Intracellular β-catenin accumulation eventually results in its constitutive signaling to the nucleus. In the nucleus, β-catenin binds to the TCF/LEF family of transcription factors, thus modulating expression of a broad range of Wnt target genes. Cyclin D1 and c-myc are the main Wnt target genes that are involved in tumorigenesis. Cytoplasmic expression of cyclin D1 and c-myc is significantly increased in LSTs versus PAs. When compared at the same grade of intraepithelial neoplasia, cytoplasmic expression of cyclin D1 and c-myc is also stronger in LSTs-LGIN compared with PAs-LGIN. Moreover, more LSTs show nuclear expression of cyclin D1 and c-myc than PAs. Expression of cyclin D1 and c-myc, especially in the nucleus, indicates the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. These results further imply that activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway may be stronger in LSTs than in PAs.

The factors causing the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in LSTs are still unknown. Many regulatory factors are suggested to be involved in β-catenin accumulation, such as GSK-3βser9 phosphorylation, β-catenin, APC, or AXIN mutation (Pennisi 1998; Fodde et al. 2001; Nosho et al. 2005). Nosho et al. (2005) found intense nuclear expression of β-catenin and interstitial deletion of β-catenin exon 3 in LST tissues. Hashimoto et al. (2008) reported that the hypermethylation status of APC was inversely associated with submucosal invasion of LSTs. In the present study, we find that the expression of β-catenin is significantly correlated with phospho-GSK-3βser9 expression in LSTs, which suggests that phosphorylation-dependent inactivation of GSK-3β could be involved in the accumulation of β-catenin. We also investigated the expression of AXIN by immunohistochemistry and did not find any difference in its expression between LSTs and PAs (data not shown).

In conclusion, the present study finds that activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway appears to be stronger in LSTs than in PAs. In addition, phosphorylation-dependent inactivation of GSK-3β might be involved in the accumulation of cytoplasmic β-catenin in LSTs but not in PAs. As a distinct type of colorectal tumor, LSTs deserve greater attention.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of China Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education, grant 20069981008.

The authors thank Professors Yali Zhang, Yadong Wang, and Chudi Chen for their suggestions regarding immunohistochemistry.

References

- Abe S, Terai T, Sakamoto N, Beppu K, Nagahara A, Kobayashi O, Ohkusa T, et al. (2006) Clinicopathological features of nonpolypoid colorectal tumors as viewed from the patients' background. J Gastroenterol 41:325–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CB, Neufeld KL, White RL (2002) Subcellular distribution of Wnt pathway proteins in normal and neoplastic colon. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99:8683–8688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravou V, Klironomos G, Papadaki E, Taraviras S, Varakis J (2006) ILK over-expression in human colon cancer progression correlates with activation of β-catenin, down-regulation of E-cadherin and activation of the Akt–FKHR pathway. J Pathol 208:91–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang JM, Chou YH, Chen TC, Ng KF, Lin JL (2002) Nuclear β-catenin expression is closely related to ulcerative growth of colorectal carcinoma. Br J Cancer 86:1124–1129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H (2004) Wnt breakers in colon cancer. Cancer Cell 5:91–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon ER, Vogelstein B (1990) A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell 61:759–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodde R, Brabletz T (2007) Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cancer stemness and malignant behavior. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19:150–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodde R, Smits R, Clevers H (2001) APC, signal transduction and genetic instability in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 1:55–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kakushima N, Kodashima S, Ichinose M, Omata M (2006) Successful endoscopic en bloc resection of a large laterally spreading tumor in the rectosigmoid junction by endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc 63:178–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles RH, van Es JH, Clevers H (2003) Caught up in a Wnt storm: Wnt signaling in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 1653:1–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Shimizu Y, Suehiro Y, Okayama N, Hashimoto S, Okada T, Hiura M, et al. (2008) Hypermethylation status of APC inversely correlates with the presence of submucosal invasion in laterally spreading colorectal tumors. Mol Carcinog 47:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto S, Higaki S, Amano A, Harada K, Nishikawa J, Yoshida T, Okita K, et al. (2007) Relationship between molecular markers and endoscopic findings in laterally spreading tumors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 22:30–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka S, Kato J, Tatsukawa M, Harada K, Fujita H, Morikawa T, Shiraha H, et al. (2006) Laterally spreading type of colorectal adenoma exhibits a unique methylation phenotype and K-ras mutations. Gastroenterology 131:379–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlstone DP, Korulla C, Lobo AJ (2002) Colorectal laterally spreading tumors: clinical evaluation and endoscopic strategies updated. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 17:1344–1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WH, Suh JH, Kim TI, Shin SK, Paik YH, Chung HW, Kim DY, et al. (2003) Colorectal flat neoplasia. Dig Liver Dis 35:165–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga Y, Yao T, Hirahashi M, Kumashiro Y, Ohji Y, Yamada T, Tanaka M, et al. (2008) Flat adenoma-carcinoma sequence with high-malignancy potential as demonstrated by CD10 and beta-catenin expression: a different pathway from the polypoid adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Histopathology 52:569–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi K, Takimoto M, Kaneko K, Makino R, Hirayama Y, Nozawa H, Kurahashi T, et al. (2006) BRAF mutations and phosphorylation status of mitogen-activated protein kinases in the development of flat and depressed-type colorectal neoplasias. Br J Cancer 94:311–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo S (1993) Endoscopic mucosal resection of flat and depressed types of early colorectal cancer. Endoscopy 25:455–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami M, Nosho K, Yamamoto H, Takahashi T, Maehata T, Taniguchi H, Adachi Y, et al. (2006) Mutational analysis of β-catenin and the RAS-RAF signalling pathway in early flat-type colorectal tumours. Eur J Cancer 42:3065–3072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller JD, Bethke B, Stolte M (2002) Colorectal de novo carcinoma: a review of its diagnosis, histopathology, molecular biology, and clinical relevance. Virchows Arch 440:453–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukawa K, Fujii S, Takeda J, Kitajima K, Tominaga K, Chibana Y, Fujita M, et al. (2005) Analysis of K-ras mutations and expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and gastrin protein in laterally spreading tumors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 20:1584–1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosho K, Yamamoto H, Mikami M, Takahashi T, Adachi Y, Endo T, Hirata K, et al. (2005) Laterally spreading tumour in which interstitial deletion of β-catenin exon 3 was detected. Gut 54:1500–1508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno Y, Terai T, Ogihara T, Hirai S, Miwa H (2001) Laterally spreading tumor: clinicopathological study in comparison with the depressed type of colorectal tumor. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 16:770–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennisi E (1998) How a growth control path takes a wrong turn to cancer. Science 281:1438–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Q, Ramadani M, Gansauge S, Gansauge F, Leder G, Beger HG (2001) Reduced membranous and ectopic cytoplasmic expression of β-catenin correlate with cyclin D1 overexpression and poor prognosis in pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer 95:194–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segditsas S, Tomlinson I (2006) Colorectal cancer and genetic alterations in the Wnt pathway. Oncogene 25:7531–7537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sena P, Saviano M, Monni S, Losi L, Roncucci L, Marzona L, De Pol A (2006) Subcellular localization of β-catenin and APC proteins in colorectal preneoplastic and neoplastic lesions. Cancer Lett 241:203–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakoori A, Ougolkov A, Yu ZW, Zhang B, Modarressi MH, Billadeau DD, Mai M, et al. (2005) Deregulated GSK3β activity in colorectal cancer: its association with tumor cell survival and proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 334:1365–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Nosho K, Yamamoto H, Mikami M, Taniguchi H, Miyamoto N, Adachi Y, et al. (2007) Flat-type colorectal advanced adenomas (laterally spreading tumors) have different genetic and epigenetic alterations from protruded-type advanced adenomas. Mod Pathol 20:139–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura S, Nakajo K, Yokoyama Y, Ohkawauchi K, Yamada T, Higashidani Y, Miyamoto T, et al. (2004) Evaluation of endoscopic mucosal resection for laterally spreading rectal tumors. Endoscopy 36:306–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Haruma K, Oka S, Takahashi R, Kunihiro M, Kitadai Y, Yoshihara M, et al. (2001) Clinicopathologic features and endoscopic treatment of superficially spreading colorectal neoplasms larger than 20 mm. Gastrointest Endosc 54:62–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira CR, Tanaka S, Haruma K, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Kajiyama G, Shimamoto F (1996) Flat-elevated colorectal neoplasms exhibit a high malignant potential. Oncology 53:89–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wetering M, Sancho E, Verweij C, de Lau W, Oving I, Hurlstone A, van der Horn K, et al. (2002) The β-Catenin/TCF-4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell 111:241–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y, Yoshimi N, Hirose Y, Kawabata K, Matsunaga K, Shimizu M, Hara A, et al. (2000) Frequent β-catenin gene mutations and accumulations of the protein in the putative preneoplastic lesions lacking macroscopic aberrant crypt foci appearance, in rat colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 60:3323–3327 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]