Abstract

A fundamental goal of sociobiology is to explain how complex social behaviour evolves1, especially in social insects, the exemplars of social living. Although still the subject of much controversy2, recent theoretical explanations have focused on the evolutionary origins of worker behaviour (assistance from daughters that remain in the nest and help their mother to reproduce) through expression of maternal care behaviour towards siblings3,4. A key prediction of this evolutionary model is that traits involved in maternal care have been co-opted through heterochronous expression of maternal genes5 to result in sib-care, the hallmark of highly evolved social life in insects6. A coupling of maternal behaviour to reproductive status evolved in solitary insects, and was a ready substrate for the evolution of worker-containing societies3,4,7,8. Here we show that division of foraging labour among worker honey bees (Apis mellifera) is linked to the reproductive status of facultatively sterile females. We thereby identify the evolutionary origin of a widely expressed social-insect behavioural syndrome1,5,7,9, and provide a direct demonstration of how variation in maternal reproductive traits gives rise to complex social behaviour in non-reproductive helpers.

Worker honey bees change the tasks that they perform with age10. This behaviour results in a division of labour that is age-associated11. Workers usually make a transition from working in the nest to foraging in their second or third week of life12, and foragers often specialize in collecting nectar or pollen. Recent studies have identified a suite of traits that differ between nectar and pollen foragers9. These traits are affected by a pleiotropic genetic network13, and it has been suggested that this pleiotropy can be explained if a reproductive regulatory network was co-opted by natural selection to differentiate the foraging behaviour of the facultatively sterile workers7. This hypothesis emerged from studies of honey bees that were selected to collect and store high (the high-hoarding strain) or low (the low-hoarding strain) amounts of pollen14. Traits of the strains diverge, so that high pollen-hoarding bees switch from nest tasks to foraging earlier in life, and are more likely to collect pollen and carry larger pollen loads. Bees from the high pollen-hoarding strain are more likely than bees from the low pollen-hoarding strain to collect water and nectar with low sugar concentration, and at emergence they have higher haemolymph (blood) levels of juvenile hormone and vitellogenin protein7. Pollen foraging is a maternal reproductive behaviour in solitary bees, and non-reproductive females feed mainly on nectar15. Elevated juvenile hormone levels cause physiological and behavioural changes during the reproductive maturation of many insects7,16,17, and vitellogenin is a conserved yolk precursor synthesized by most oviparous females18. Therefore, the evidence from pollen-hoarding strains suggests that nectar-foraging bees display a non-reproductive phenotype, whereas pollen foragers display the ancestral maternal character state of solitary species7. As a consequence, the foraging division of labour between worker bees would be derived from variation in maternal reproductive traits. Validation of this hypothesis, however, requires the demonstration of a relationship between the reproductive status and the foraging behaviour of honey bee workers7.

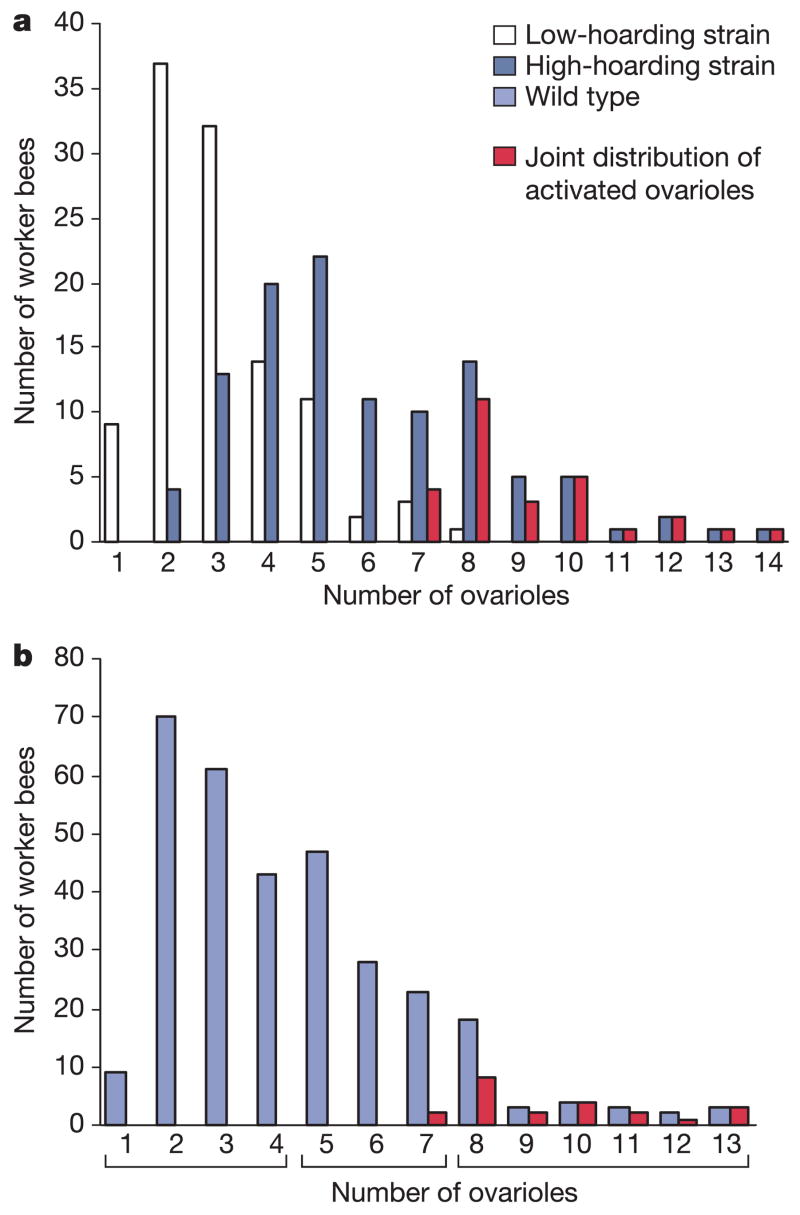

We addressed the debate on the origin of complex social behaviour by first inspecting the number of ovarioles (egg-forming filaments in the ovary) in newly emerged workers from the previously examined7 high and low pollen-hoarding strains. Developmental differentiation of ovariole number19 is influenced by endocrine regulatory networks that during the adult stage are responsible for modulation of maternal reproductive behaviour in insects7,20,21. Ovariole number is, moreover, a recognized marker of reproductive potential in the honey bee22, as well as in the well-studied solitary insect Drosophila21,23. We found that high pollen-hoarding strain workers had more ovarioles than those from the low pollen-hoarding strain (factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA), P < 0.005). This difference was independent (factorial ANOVA, P = 0.72) of whether the workers were co-fostered (mean ± s.e.m., 5.56 ± 0.42 and 2.96 ± 0.31 ovarioles for the high and low pollen-hoarding strains, respectively; n = 25 per strain) or reared by their native colony (5.88 ± 0.41 and 2.88 ± 0.19 ovarioles; n = 25). Furthermore, bees with eight or more ovarioles were exclusively found in the high pollen-hoarding strain, where they represented 26% of the sample population (Supplementary Table S1). We also observed that this higher number of ovary filaments was associated with a swelling of the ovarioles (Supplementary Table S1), which is an established indicator of previtellogenic ovarian activation24,25. These results demonstrate that a regulatory system that affects female reproductive morphology, physiology, and behaviour7,20,21,26 is differentially tuned during the development of honey bees characterized by different levels of pollen hoarding.

To verify that the observed variation in ovariole number translates into functional differences in adult reproductive potential, we next introduced high and low pollen-hoarding bees into host colonies with or without a queen (the presence of a queen inhibits worker oogenesis27). The experimental design also controlled for rearing environment by using workers that were co-fostered and workers that were reared in their native high or low pollen-hoarding strain colony. The bees were examined after 10–21 days. In colonies with a queen (n = 6 colonies), we found that 29.5 ± 3.6% of the bees from the high pollen-hoarding strain (n = 201) had activated previtellogenic ovaries, compared with 2.6 ± 1.8% of the workers from the low pollen-hoarding strain (n = 201) (Supplementary Table S2). This divergence (factorial ANOVA, P < 0.005) was independent of whether the bees were co-fostered or reared by their native colony (factorial ANOVA, P = 0.42). The effect of hoarding strain on the proportion of individuals with non-activated ovaries versus previtellogenic ovaries was significant in all hives (V-square test, P < 0.05). Also, previtellogenic ovarian activation was exclusively found in workers with seven or more ovarioles (Supplementary Table S2). These results from mature workers (Fig. 1a) correspond with the data from newly emerged bees (Supplementary Table S1), suggesting that a sizable proportion of worker bees selected to collect and store high amounts of pollen emerge with an active ovarian phenotype that persists for several weeks in the presence of a fully functional queen.

Figure 1. Distributions of ovariole number and patterns of previtellogenic ovarian activation in worker bees.

a, Ovariole number in mature 10- to 21-day-old bees from strains selected for high or low levels of pollen hoarding (n = 109 bees per strain). b, Samples from wild-type bees collected at presumably their first foraging flight (n = 314). The mean numbers of ovarioles (±s.e.m.) for groups with 1–4, 5–7 and 8 or more ovarioles are 2.75 ± 0.06, 5.76 ± 0.08 and 9.30 ± 0.30, respectively. The joint distributions of ovarian activation are superimposed on the original densities and refer, therefore, to bees within the genotype-specific data sets.

In colonies without a queen (n = 6 colonies), 75.8 ± 0.1% of the high pollen-hoarding workers (n = 212) had active ovaries that were previtellogenic, vitellogenic with developing oocytes, or vitellogenic with eggs (Supplementary Table S2). In comparison, 42.0 ± 0.1% of bees from the low pollen-hoarding strain had active ovaries (n = 212). This difference between strains (factorial ANOVA, P < 0.05) was independent of rearing environment (factorial ANOVA, P = 0.94). The effect of hoarding strain on the proportion of workers with non-activated ovaries versus previtellogenic ovaries was significant in all but one hive (V-square test, P < 0.05), and out of the 48 bees with eggs, 36 were from the high pollen-hoarding strain (Supplementary Table S2). Eggs were found in bees with five or more ovarioles (Supplementary Table S2). These results demonstrate that workers selected for a high level of pollen hoarding have a functional phenotype that more frequently achieves an advanced reproductive state.

Finally, we used workers from ‘wild-type’ colonies (not selected for pollen hoarding) to test whether the trait-associations that characterize the high and low pollen-hoarding strains are present in the general population. Wild-type bees were marked at adult eclosion and later captured at presumably their first foraging flight (n = 551). The nectar- and pollen-loads of the workers were quantified, and ovariole number was determined by dissection of those bees (n = 314) that carried measurable amounts of nectar or pollen (more than 0.0005 g).

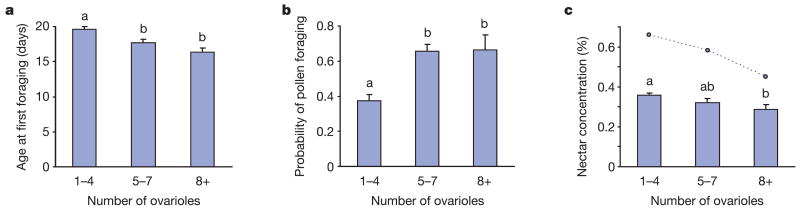

We first investigated whether an association between ovariole number and previtellogenic ovarian activation was present. Activation occurred exclusively in bees with seven or more ovarioles (Fig. 1b), confirming our findings from the selected strains. On the basis of ovariole number, we then divided the data from the 314 workers into three groups. The first group had a mean ovariole number similar to the low pollen-hoarding strain (1–4 ovarioles, n = 184), the next had a mean ovariole number comparable to the high strain (5–7 ovarioles, n = 97), and the last group consisted of bees with eight or more ovarioles (n = 33) (Fig. 1b). Subsequent analysis of the data set showed that ovariole number correlated with the adult age of bees at their first foraging flight, the probability of being a pollen forager, and the nectar concentration collected by the workers (multivariate ANOVA; P < 0.00001). Worker bees with 5–7 and 8 or more ovarioles initiated foraging at younger ages than bees with 1–4 ovarioles (Fig. 2a). Workers with 5–7 and 8 or more ovarioles were also more likely to forage for pollen (Fig. 2b). In addition, the bees with 8 or more ovarioles collected lower nectar concentrations than workers with only 1–4 ovary filaments (Fig. 2c). Consequently, the trait-associations of wild-type bees with the greatest number of ovary filaments corresponded precisely with those shown for the strain selected to collect and store high amounts of pollen7,9.

Figure 2. Correlations between ovariole number and the social behaviour of wild-type bees.

a, Honey bee age at presumably the first foraging flight. b, The probability of being a pollen forager. c, The sugar concentration of nectar collected by the worker bees. Data show mean ± s.e.m. Different letters (a, b) refer to groups that were different according to a Fisher’s post-hoc test (P < 0.05). Points connected by a dotted line in c denote the highest nectar concentration collected by any single bee in the respective ovariole groups.

We conclude that division of foraging labour in the advanced eusocial honey bee emerges from variation in maternal care behaviour. This finding illustrates how the behavioural mechanisms of division of labour evolve from solitary ancestry, and provides an experimental demonstration of the origins of sib-care behaviour from maternal reproductive traits3–5,7. The evolution of sib-care from maternal care is a critical step towards the evolution of eusociality in insects, and remains a point of substantial debate5,8,28,29.

METHODS

Bees selected for high or low levels of pollen hoarding

Larvae from six high and six low pollen-hoarding strain queens were reared together in common wild-type nurse colonies. For workers reared by their native colony, frames with mature pupae were obtained from the same 12 sources. Newly emerged bees were collected for ovarian analysis or marked on the thorax with a spot of paint (Testors Enamel) for identification of strain and age. Marked workers were added to host colonies with or without a queen.

Wild-type bees

Newly emerged bees from four unrelated and unselected source/host colonies were mixed together to obtain a worker pool with high phenotypic variance. The bees were marked (see above) for identification of age, and each source/host colony received 400 workers from the mix. Starting five days later, the hive entrances were monitored between 9:00 in the morning and 14:00 in the afternoon, and marked bees that returned from flight were collected.

Foraging load measurements

Bees were treated with CO2 until immobile to enable quantification of pollen weight, nectar weight and nectar sugar concentration, as reported previously30.

Quantification of ovariole number and ovarian physiology

Bees were dissected under a stereomicroscope at ×40 magnification. Incisions were made dorsally, and the number of ovarioles in the right-side ovary24 was determined at ×100 magnification. The extent of ovarian activation was determined using a relative scale as described previously24: 1, non-activated ovary; 2, previtellogenic activated ovary; 3, vitellogenic ovary with developing oocytes; 4, mature ovary with at least one egg.

Data analysis

Ovariole number and ovarian activation in bees selected for high or low levels of pollen hoarding were analysed using factorial ANOVA. Analyses were combined with Fisher’s post-hoc and non-parametric V-square tests to examine the effect of strain. Foraging data from wild-type bees were analysed with multivariate ANOVA and Fisher’s post-hoc test. Ovariole number (coded by group: 1–4, 5–7, and 8 or more ovarioles) and host colony were the categorical factors. The effect of host colony was used to control error variance. Pollen load was coded as a binary variable. Statistica 6.0 software was used.

Acknowledgments

We thank A.L.O.T. Aase for assistance with dissections, and K. Hartfelder and P. Kukuk for comments. The project was supported by grants from the Norwegian Research Council to G.V.A, and from the National Institute on Aging and the National Research Initiative of the USDA Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service to R.E.P.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Information Reprints and permissions information is available at npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Robinson GE, Grozinger CM, Whitfield CW. Sociogenomics: social life in molecular terms. Nature Rev Genet. 2005;6:257–270. doi: 10.1038/nrg1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson EO, Hölldobler B. Eusociality: origin and consequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13367–13371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505858102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.West-Eberhard MJ. In: Animal Societies: Theories and Fact. Itô Y, Brown JL, Kikkawa J, editors. Japan Sci. Soc. Press; Tokyo: 1987. pp. 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- 4.West-Eberhard MJ. In: Natural History and Evolution of Paper Wasp. Turillazzi S, West-Eberhard MJ, editors. Oxford Univ. Press; New York: 1996. pp. 290–317. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linksvayer TA, Wade MJ. The evolutionary origin and elaboration of sociality in the aculeate Hymenoptera: Maternal effects, sib-social effects, and heterochrony. Q Rev Biol. 2005;80:317–336. doi: 10.1086/432266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.West-Eberhard MJ. Developmental Plasticity and Evolution. Oxford Univ. Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amdam GV, Norberg K, Fondrk MK, Page RE. Reproductive ground plan may mediate colony-level selection effects on individual foraging behaviour in honey bees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11350–11355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403073101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunt JH, Amdam GV. Bivoltinism as an antecedent to eusociality in the paper wasp genus Polistes. Science. 2005;308:264–267. doi: 10.1126/science.1109724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page RE, Erber J. Levels of behavioural organization and the evolution of division of labour. Naturwissenschaften. 2002;89:91–106. doi: 10.1007/s00114-002-0299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seeley TD. The Wisdom of the Hive. Harvard Univ. Press; Cambridge, Massachusetts: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson GE. Regulation of division of labour in insect societies. Annu Rev Entomol. 1992;37:637–665. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.37.010192.003225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winston ML. The Biology of the Honey Bee. Harvard Univ. Press; Cambridge, Massachusetts: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rueppell O, Pankiw T, Page RE. Pleiotropy, epistasis and new QTL: The genetic architecture of honey bee foraging behaviour. J Hered. 2004;95:481–491. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esh072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Page RE, Fondrk MK. The effects of colony-level selection on the social organization of honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) colonies: colony-level components of pollen hoarding. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1995;36:135–144. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn T, Richards MH. When to bee social: interactions among environmental constraints, incentives, guarding, and relatedness in a facultatively social carpenter bee. Behav Ecol. 2003;14:417–424. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simonet G, et al. Neuroendocrinological and molecular aspects of insect reproduction. J Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16:649–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Min KJ, Taub-Montemayor TE, Linse KD, Kent JW, Rankin MA. Relationship of adipokinetic hormone I and II to migratory propensity in the grasshopper, Melanoplus sanguinipes. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 2004;55:33–42. doi: 10.1002/arch.10109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spieth J, Nettleton M, Zuckeraprison E, Lea K, Blumenthal T. Vitellogenin motifs conserved in nematodes and vertebrates. J Mol Evol. 1991;32:429–438. doi: 10.1007/BF02101283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capella ICS, Hartfelder K. Juvenile hormone effect on DNA synthesis and apoptosis in caste-specific differentiation of the larval honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) ovary. J Insect Physiol. 1998;44:385–391. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(98)00027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tatar M, Yin CM. Slow aging during insect reproductive diapause: why butterflies, grasshoppers and flies are like worms. Exp Gerontol. 2001;36:723–738. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00238-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tu MP, Tatar M. Juvenile diet restriction and the aging and reproduction of adult Drosophila melanogaster. Aging Cell. 2003;2:327–333. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka ED, Hartfelder K. The initial stages of oogenesis and their relation to differential fertility in the honey bee (Apis mellifera) castes. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2004;33:431–442. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodin J, Riddiford LM. Different mechanisms underlie phenotypic plasticity and interspecific variation for a reproductive character in drosophilids (Insecta: Diptera) Evolution. 2000;54:1638–1653. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartfelder K, Bitondi MMG, Santana WC, Simões ZLP. Ecdysteroid titer and reproduction in queens and workers of the honey bee and of a stingless bee: loss of ecdysteroid function at increasing levels of sociality? Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;32:211–216. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(01)00100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maurizio A. Pollenernahrung und Lebensvorgange bei der Honigbiene (Apis mellifera L.) Landwirtsch Jahrb Schweiz. 1954;245:115–182. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartfelder K, Köstlin K, Hepperle C. Ecdysteroid-dependent protein synthesis in caste-specific development of the larval honey bee ovary. Rouxs Arch Dev Biol. 1995;205:73–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00188845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butler CG. The control of ovary development in worker honeybees (Apis mellifera) Experientia. 1957;13:256–257. doi: 10.1007/BF02157449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bloch G, Wheeler D, Robinson GE. In: Hormones, Brain and Behavior. Pfaff D, Arnold AP, Etgen AM, Fahrbach SE, Rubin RT, editors. Academic; San Diego: 2002. pp. 195–235. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson GE, Ben-Shahar Y. Social behaviour and comparative genomics: new genes or new gene regulation? Genes Brain Behav. 2002;1:197–203. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-183x.2002.10401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gary NE, Lorenzen K. A method for collecting the honey-sac content from honeybees. J Apic Res. 1976;15:73–79. [Google Scholar]