Abstract

A saprophytic Bacillus subtilis secretes two types of rhamnogalacturonan (RG) lyases, endotype YesW and exotype YesX, which are responsible for an initial cleavage of the RG type I (RG-I) region of plant cell wall pectin. Polysaccharide lyase family 11 YesW and YesX with a significant sequence identity (67.8%) cleave glycoside bonds between rhamnose and galacturonic acid residues in RG-I through a β-elimination reaction. Here we show the structural determinants for substrate recognition and the mode of action in polysaccharide lyase family 11 lyases. The crystal structures of YesW in complex with rhamnose and ligand-free YesX were determined at 1.32 and 1.65 Å resolution, respectively. The YesW amino acid residues such as Asn152, Asp172, Asn532, Gly533, Thr534, and Tyr595 in the active cleft bind to rhamnose molecules through hydrogen bonds and van der Waals contacts. Other rhamnose molecules are accommodated at the noncatalytic domain far from the active cleft, revealing that the domain possibly functions as a novel carbohydrate-binding module. A structural comparison between YesW and YesX indicates that a specific loop in YesX for recognizing the terminal saccharide molecule sterically inhibits penetration of the polymer over the active cleft. The loop-deficient YesX mutant exhibits YesW-like endotype activity, demonstrating that molecular conversion regarding the mode of action is achieved by the addition/removal of the loop for recognizing the terminal saccharide. This is the first report on a structural insight into RG-I recognition and molecular conversion of exotype to endotype in polysaccharide lyases.

Carbohydrate-active enzymes such as glycoside hydrolases (GHs)2 (1), polysaccharide lyases (PLs), glycosyl transferases, and carbohydrate esterases are categorized into over 200 families based on their amino acid sequences in the Carbohydrate-Active enZymes (CAZy) data base (1). Lyases are classified into 18 PL families. PLs commonly recognize uronic acid residues in polysaccharides, catalyze a β-elimination reaction, and produce unsaturated saccharides with C=C double bonds in uronic acid residues at the newly formed nonreducing terminus. The crystal structures of PLs in 12 families have been determined thus far, and the structure and functional relationships of enzymes such as lyases for polygalacturonan, alginate, chondroitin, hyaluronan, and xanthan have been demonstrated (2-10). On the other hand, little knowledge has been accumulated on the mechanisms of substrate recognition and catalytic reaction in lyases acting on the rhamnogalacturonan (RG) region of pectin.

Pectin, the major component of the plant cell wall, is divided into three regions, i.e. polygalacturonan, RG type I (RG-I), and RG type II (RG-II). In pectin molecules, polygalacturonan is present as a linear backbone, and RG-I and RG-II are attached to the backbone as branched chains (11-13). RG-I is a polymer with a disaccharide-repeating unit consisting of l-rhamnopyranose (Rha) and d-galactopyranouronic acid (GalA) as the main chain, and arabinans and galactans are attached to the main chain (14). RG-II has a backbone of polygalacturonan, and its side chains consist of a complex of about 30 monosaccharides, including rare sugars such as apiose and aceric acid (15).

RG lyases are responsible for cleaving the α-1,4 bonds of the RG-I main chain (RG chain) through the β-elimination reaction (Fig. 1A) and belong to PL families 4 and 11, which mainly contain fungal and bacterial enzymes, respectively. Recently, we have reported the enzymatic route for degradation of the RG chain in a saprophytic Bacillus subtilis strain 168 (16). This bacterium secretes two types of PL family 11 RG lyases, YesW and YesX, extracellularly. YesW cleaves the glycoside bond of the RG chain endolytically, and the resultant oligosaccharides are subsequently converted to disaccharides, unsaturated galacturonyl rhamnose (ΔGalA-Rha), through the exotype YesX reaction (16) (Fig. 1). The crystal structures of YesW and its complex with GalA disaccharide (YesW/GalA-GalA) reveal that the enzyme adopts a β-propeller fold as a basic scaffold and has an active cleft at the center of the β-propeller (17), although the three-dimensional structure of YesX and the structural determinants for recognition of the substrate, especially Rha molecules, and the mode of action in PL family 11 RG lyases, are yet to be clarified.

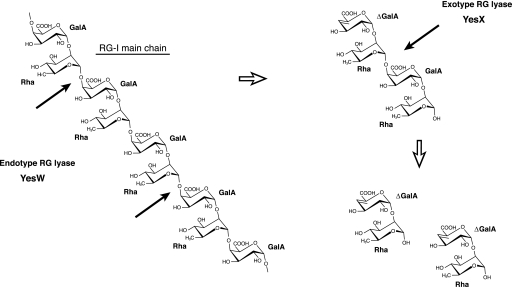

FIGURE 1.

RG chain degradation by B. subtilis endo- and exotype RG lyases. Thick arrows indicate the cleavage sites for each enzyme against substrate.

A synergistic catalysis by the endo- and exotype PLs plays an important role in initial degradation of the target polysaccharide. A plant-pathogenic Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937 secretes eight isoenzymes of pactate lyases such as PelA, PelB, PelC, PelD, PelE, PelI, PelL, and PelZ and one exotype polygalacturonate lyase PelX for degradation of polygalacturonan (18). In alginate degradation by plant-related Sphingomoans sp. strain A1, three endotype alginate lyases, A1-I, A1-II, and A1-III, release oligosaccharides from the polymer, and the resultant oligoalginates are converted to the constituent monosaccharides through the reaction of exotype lyase, A1-IV (19). Structure and function relationships in the endotype PLs have been demonstrated (2, 3), but little information on the structural features of exotype lyases has been accumulated. Endotype YesW and exotype YesX from B. subtilis significantly resemble each other in primary structure, i.e. 68.7% identity in 597-amino acid overlap (16), suggesting that their mode of action (endo/exo) is determined by a slight structural difference present in the catalytic domain. Structure comparison between YesW and YesX facilitates not only the identification of structural determinants for the mode of action but also the establishment of biotechnological bases of endo/exo interconversion in PLs.

This article deals with the identification of structural determinants for substrate recognition and the mode of action in PL family 11 lyases through the determination of the crystal structures of YesW in complex with Rha (YesW/Rha) and YesX. On the basis of this structure and function relationship, exotype YesX was converted into YesW-like endotype enzyme by protein engineering.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials—RG-I (from potatoes) was purchased from Megazyme. l-Rha was purchased from Wako Pure Chemical. Ni2+-chelating Sepharose™ Fast Flow and HiLoad™ 16/60 Superdex™ 200 pg were purchased from GE Healthcare. The RG chain, substrate for YesW and YesX, was prepared from RG-I as described previously (16).

Assays for Enzymes and Proteins—RG lyases was incubated at 30 °C for 5 min in a reaction mixture (1 ml) consisting of 0.5 mg/ml RG-I, 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and 2 mm CaCl2. Activity was determined by monitoring the increase in absorbance at 235 nm arising from the double bond formed in the reaction products. One unit (U) of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to produce an increase of 1.0 in absorbance at 235 nm/min using a cuvette with a light path 1 cm long. The protein content was determined by the Bradford method (20), with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Protein Preparation—Protein expression and purification of YesW and YesX were conducted as described previously (16, 21). Briefly, YesW and YesX expressed in Escherichia coli cells were purified through two-step column chromatography, i.e. Ni2+-chelating Sepharose™ Fast Flow and HiLoad™ 16/60 Superdex™ 200 pg. Each purified enzyme includes the C-terminal histidine-tagged sequence (eight amino acid residues, LEHHHHHH) derived from the expression vector pET21b (Novagen). The N-terminal 37 amino acid residues of YesW (total 628 amino acid residues) are excised as a signal peptide in E. coli cells (21). The molecular masses of the purified YesW and YesX including a C-terminal histidine tag were calculated to be 64,444 Da (591 amino acid residues) and 68,754 Da (620 amino acid residues), respectively.

Crystallization and X-ray Diffraction—Crystallization of YesW was conducted as described previously (17, 21). To analyze the complex form of YesW and Rha (YesW/Rha), a single crystal of YesW was soaked at 20 °C for 15 h in a solution containing 1.5 m Rha, 0.1 m Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), and 2 mm CaCl2. The crystal of YesX was prepared as follows. Purified YesX (7.5 mg/ml) in 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 2 mm CaCl2 and 0.2 m NaCl was crystallized at 20 °C by sitting drop vapor diffusion using Intelli-Plate (Veritas). The reservoir solution volume in each well was 0.1 ml, and the droplet was prepared by mixing 1 μl of the protein solution and 1 μl of the reservoir solution. A crystal suitable for x-ray analysis was obtained using a polyethylene glycol/ion screen kit (Hampton Research) for about a month. The reservoir solution for successful crystallization consisted of 20% polyethylene glycol 3350 and 0.2 m ammonium acetate.

Crystals of YesW/Rha and YesX on a nylon loop (Hampton Research) were placed in a cold nitrogen gas stream at -173 °C, and x-ray diffraction images were collected at -173 °C under the nitrogen gas stream with a Jupiter 210 CCD detector and synchrotron radiation of wavelength 0.800 Å for the YesW/Rha crystal and 1.000 Å for the YesX crystal at the BL-38B1 station of SPring-8 (Hyogo, Japan). Additional cryoprotectant was required for vitrification of the YesX crystallization drop. To reduce the “ice rings,” glycerol was added to the reservoir solution of the YesX crystal at a final concentration of 20%. Two hundred forty diffraction images from the crystal with 1.0° oscillation were collected as a series of consecutive data sets. Diffraction data were processed using the HKL2000 program package (22). The data collection statistics are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| YesW/Rha | YesX | |

|---|---|---|

| Space group | P21 | P212121 |

| Unit cell parameters (Å) | a = 57.3, b = 105.9, c = 101.0, β = 94.8 | a = 72.9, b = 88.1, c = 99.3 |

| Data collection | ||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.800 | 1.000 |

| Resolution limit (Å) | 50.0-1.32 (1.37-1.32)a | 50.0-1.65 (1.71-1.65) |

| Total reflections | 1,043,631 | 747,425 |

| Unique reflections | 280,440 | 77,151 |

| Redundancy | 3.8 (3.6) | 9.8 (9.1) |

| Completeness (%) | 97.6 (95.1) | 98.9 (97.4) |

| I/Sigma (I) | 13.0 (2.8) | 8.2 (4.1) |

| Rmerge (%) | 6.6 (33.8) | 9.4 (25.8) |

| Refinement | ||

| Final model | 1,164 (582 × 2) residues, 1,255 water molecules, 20 calcium ions, | 604 residues, 706 water molecules, 9 calcium ions, |

| 2 2-metyl-2,4-pentanediol, 7 rhamnose molecules | ||

| Resolution limit (Å) | 50.0-1.32 (1.35-1.32) | 37.2-1.65 (1.70-1.65) |

| Used reflections | 259,908 (18,169) | 72,365 (5,090) |

| Completeness (%) | 97.4 (92.2) | 98.7 (94.9) |

| Average B factor (Å2) | ||

| Protein | 14.1, 15.3 (molecule A, B) | 9.6 |

| Water | 28.9 | 23.1 |

| Calcium ions | 11.8 | 7.7 |

| 2-Metyl-2,4-pentanediol | 34.1 | |

| Rhamnose | 26.1 | |

| R factor (%) | 16.7 (23.3) | 16.2 (19.8) |

| Rfree (%) | 18.0 (25.8) | 18.4 (24.9) |

| Root mean square deviations | ||

| Bond (Å) | 0.006 | 0.007 |

| Angle (°) | 1.17 | 1.10 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | ||

| Most favored regions | 89.3 | 89.3 |

| Additional allowed regions | 9.6 | 10.1 |

| Generously allowed regions | 1.0 | 0.6 |

The data for the highest shells are given in parentheses.

Structure Determination and Refinement—The crystal structures of YesW/Rha and YesX were solved by molecular replacement using the Molrep program (23) in the CCP4 program package (24) with the ligand-free YesW structure (Protein Data Bank code 2Z8R) as a reference model. The Coot program (25) was used for manual modification of the initial model. Initial rigid body refinement, and several rounds of restrained refinement against the data set were done using the Refmac5 program (26). Water molecules were incorporated where the difference in density exceeded 3.0 σ above the mean, and the 2Fo - Fc map showed a density of over 1.0 σ. At this stage, calcium ions were included in the calculation and refinement continued until convergence at maximum resolution (YesW/Rha, 1.32 Å; YesX, 1.65 Å). Protein models were superimposed, and their root mean square deviation was determined with the LSQKAB program (27), a part of CCP4. Final model quality was checked with PROCHECK (28). Ribbon plots were prepared using the PyMOL programs (29). Coordinates used in this work were taken from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (30).

Deletion Mutagenesis—To delete the loop specific for YesX corresponding to 439PPGNDGMSY447, a YesX del_loop mutant was constructed using a KOD Plus Mutagenesis Kit (Toyobo). The plasmid, pET21b/YesX, constructed as described previously (16), was used as a PCR template, and the following oligonucleotides were used as primers: sense, 5′-GGGCTTTTCACGAGCAAAGG-3′ and antisense, 5′-ATCAATTCCCCAGACGAGCGA-3′. PCR was performed according to the manufacturer's recommendation. Mutation was confirmed by DNA sequencing with an automated DNA sequencer (model 377; Applied Biosystems). Expression and purification of the mutants were conducted by the same procedures as those used for the wild-type YesX.

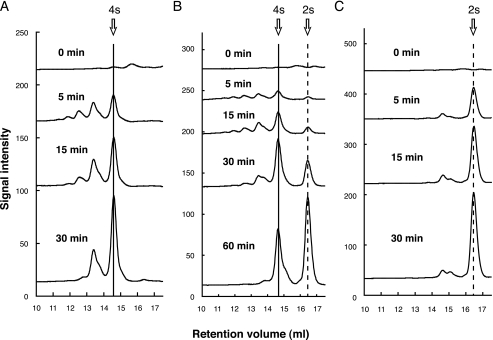

Size Exclusion Chromatography—To determine the mode of action in the YesX del_loop mutant, the degradation profile of the RG chain through the YesW, YesX, or YesX del_loop mutant reaction was analyzed by size exclusion chromatography. Appropriate amounts of YesW, YesX, or YesX del_loop mutant were incubated at 30 °C for 60 min in a reaction mixture (1 ml) consisting of 0.5 mg/ml RG chain, 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and 2 mm CaCl2. The products were subjected to size exclusion chromatography using Superdex™ peptide 10/300 GL with AKTA purifier (GE Healthcare). Saccharides were eluted at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min with 10 mm potassium phosphate (pH 7.0) and detected using a UV detector at 235 nm on the basis of C=C double bonds in the reaction products.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Structure Determination of YesW/Rha—To identify YesW residues involved in substrate binding, we first tried to prepare the crystal of YesW in complex with the enzyme reaction product ΔGalA-Rha (16) but failed. Thus, the crystal structure of YesW in complex with Rha (YesW/Rha) was determined at 1.32 Å resolution (Fig. 2). Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1. The structure of YesW/Rha was solved by molecular replacement using the wild-type structure as a reference model. N-terminal amino acid residue and C-terminal histidine-tagged sequence (8 amino acid residues, -LEHHHHHH) could not be assigned in the 2Fo - Fc map. The refined model in an asymmetric unit consists of two identical monomers (582 amino acid residues × 2) termed molecules A and B. The root mean square deviation between molecules A and B was calculated as 0.293 Å for all residues (582 Cα atoms). On the basis of theoretical curves in the plot calculated according to Luzzati (31), the absolute positional error was estimated to be 0.13 Å at a resolution of 1.32 Å. Ramachandran plot analysis (32), in which the stereochemical correctness of the backbone structure is indicated by (ϕ, ψ) torsion angles (33), shows that 89.3% of nonglycine residues lie within the most favored regions and 9.6% of nonglycine residues lie in the additionally allowed regions. Five amino acid residues (Asn152, Ala327, Asn490, Ser506, and Ala594) in each molecule fell into generously allowed regions. One cispeptide was observed between Glu285 and Pro286 residues in each generously allowed region. Four Rha molecules in molecule A are well fitted in the electron density map (Fig. 3, A and C) with an average B factor of 23.4 Å2, whereas three Rha molecules were assigned in molecule B with an average B factor of 27.6 Å2. Because YesW is active in monomeric form (16), interactions between the YesW molecule A and Rha molecules are focused on hereafter. The root mean square deviation between ligand-free YesW and YesW/Rha in molecule A was calculated as 0.129 Å for all residues (582 Cα atoms); this indicates that no significant conformational change occurs between protein structures with or without Rha molecules.

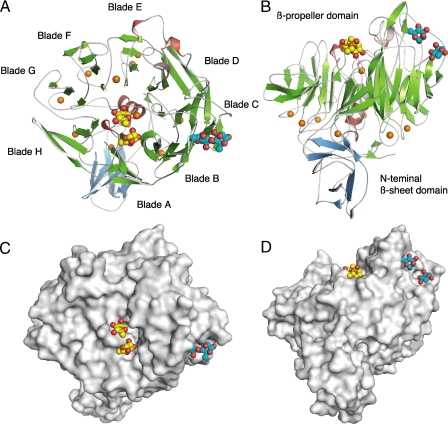

FIGURE 2.

Structure of YesW/Rha. A, overall structure. B, image in A is turned by 90° around the x axis. C, surface model. D, image in C is turned by 90° around the x axis. β-Sheets are shown as green arrows, and helices are red cylinders. The calcium ions are shown as orange balls. Rha molecules are shown as ball models: oxygen atom, red; carbon atom, yellow in molecules (RA1 and RA2) bound to the active cleft and cyan in molecules (RA3 and RA4) bound to blade C.

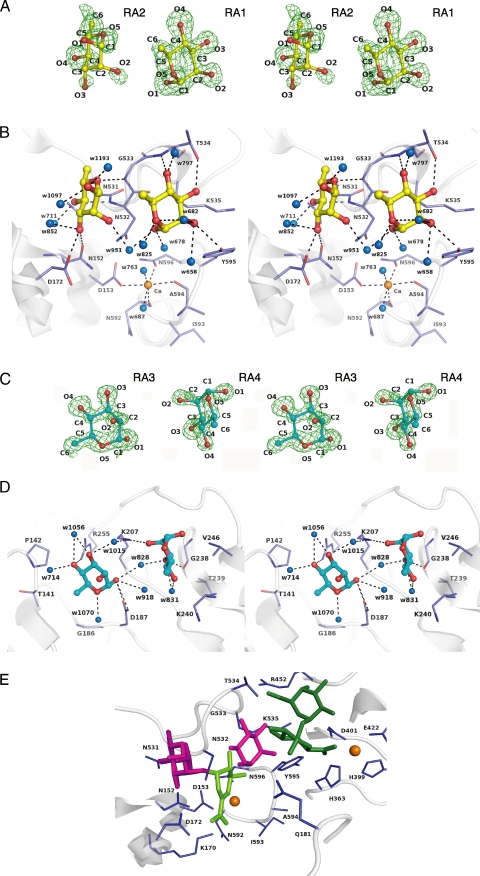

FIGURE 3.

Rhamnose binding. A, electron density of Rha molecules in the active cleft by the omit map (Fo - Fc) calculated without Rha and countered at 3.0 σ. B, residues interacting with Rha molecules in the active cleft. C, electron density of Rha molecules in CBM-like domain by the omit map (Fo - Fc) calculated without the Rha and countered at 3.0 σ. D, residues interacting with Rha molecules in the CBM-like domain. Amino acid residues and Rha molecules are shown by colored elements: oxygen atom, red; carbon atom, blue in residues, yellow in Rha molecules RA1 and RA2, and cyan in RA3 and RA4; nitrogen atom, deep blue. The calcium ions are shown as orange balls, and water molecules are blue balls. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines. The characters indicate the saccharide number and its atoms in A and C and the amino acid residues number in B and D. E, structural superimposition in the active site between YesW/Rha and YesW/GalA-GalA. Rha and GalA-GalA molecules are shown by magenta and green sticks, respectively. The reaction product, ΔGalA-Rha, is fitted on the active site by structural simulation. ΔGalA is represented by light green sticks.

Rhamnose Binding—Two (RA1 and RA2) of four Rha molecules are bound to the active cleft, which is located at the center of β-propeller (Fig. 2A). Two (Tyr595 and Thr534) and four (Asn152, Asp172, Asn532, and Gly533) amino acid residues form a direct hydrogen bond (<3.4 Å) with RA1 and RA2, respectively (Fig. 3B and Table 2). In addition to direct hydrogen bonds, 10 water-mediated hydrogen bonds exist between the enzyme and Rha molecules: RA1/O-1=Wat951=Asn532/Nδ2 (2.9 Å); RA1/O-2=Wat658=Tyr595/OH (3.0 Å), =His214/Nε2 (3.3 Å), and =Asp178/Oδ1 (2.7 Å); RA2/O-1=Wat1097=Ser174/O (3.0 Å); RA2/O-2=Wat-951=Asn532/Nδ2 (2.8 Å); RA2/O-3= Wat852=Asp172/Oδ2 (2.9 Å); RA2/O-4=Wat711=Asn152/Oδ1 (3.0 Å), =Ala-151/O (2.7 Å), and =Ser150/Oγ (2.7 Å). van der Waals contacts (<4.5 Å) between RA1 and four amino acid residues (Tyr595, Lys535, Asn532, and Gly533) and RA2 and three amino acid residues (Gly533, Asn532, and Asn531) were observed. These amino acid residues are highly conserved in PL family 11 RG lyases (YesW and YesX from B. subtilis (16), Rgl11A from Cellvibrio japonicus (34), and Rgl11Y from Clostridium cellulolyticum (35)), indicating that these play important roles in recognizing the Rha residues of the RG chain.

TABLE 2.

Interaction between YesW and Rha

|

Sugar

|

Hydrogen bond (<3.4 Å)

|

C-C contact (<4.5 Å)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atom | Protein | Atom | Distance | Atom | Protein | Atom(s) | |

| Å | |||||||

| RA1 | O-1 | Wat951 | 2.6 | C-1 | Tyr595 | C∈ 1 | |

| Wat678 | 2.8 | C-2 | Tyr595 | C∈ 1, Cζ | |||

| O-2 | Tyr595 | Oη | 3.0 | Lys535 | C∈, Cγ | ||

| Wat658 | 3.0 | C-3 | Lys535 | C∈, Cγ | |||

| Wat682 | 3.0 | Asn532 | C | ||||

| O-3 | Thr534 | Oγ1 | 2.8 | C-4 | Gly533 | Cα | |

| O-4 | Thr534 | N | 3.0 | C-5 | Asn532 | C | |

| Wat797 | 2.7 | ||||||

| O-5 | Wat825 | 2.7 | |||||

| Wat682 | 3.3 | ||||||

| RA2 | O-1 | Wat1097 | 2.6 | C-1 | Gly533 | Cα | |

| Wat1193 | 2.7 | Asn532 | C | ||||

| O-2 | Wat951 | 3.0 | C-2 | Asn532 | Cα | ||

| O-3 | Asn152 | Oδ1 | 3.1 | C-3 | Asn532 | Cα | |

| Asp172 | Oδ2 | 2.7 | C-4 | Asn532 | C, Cα | ||

| Wat852 | 3.1 | Asn531 | C, Cα | ||||

| O-4 | Asn532 | N | 3.1 | C-5 | Gly533 | Cα | |

| Wat711 | 2.7 | Asn532 | C, Cα | ||||

| O-5 | Gly533 | N | 3.0 | ||||

| RA3 | O-1 | Asp187 | Oδ1 | 2.7 | C-1 | Asp187 | Cγ |

| Oδ2 | 3.3 | C-2 | Lys207 | C∈ | |||

| Wat918 | 3.3 | C-3 | Lys207 | C∈ | |||

| Wat828 | 3.0 | C-4 | Arg255 | Cζ | |||

| O-3 | Wat1015 | 2.9 | C-6 | Thr141 | Cα, Cζ | ||

| Wat1056 | 2.9 | Tyr147 | C∈ 2 | ||||

| O-4 | Arg255 | Nη 1 | 2.8 | Gly186 | Cα | ||

| Wat1056 | 3.2 | ||||||

| Wat714 | 2.7 | ||||||

| O-5 | Wat1070 | 2.8 | |||||

| RA4 | O-2 | Lys207 | Nζ | 2.9 | C-3 | Val246 | Cγ 1, Cγ 2 |

| O-3 | Gly238 | O | 2.6 | Gly238 | Cα | ||

| Wat828 | 2.8 | C-5 | Val246 | Cγ 2 | |||

| Wat831 | 3.2 | C-6 | Lys240 | C∈ | |||

| O-4 | Wat831 | 2.8 | |||||

The other two Rha molecules (RA3 and RA4) are observed in the overhanging loop region formed in the blade C of the β-propeller domain (Fig. 2). Two amino acid residues (Asp187 and Arg255) form a direct hydrogen bond with RA3 and two (Lys207 and Gly238) with RA4 (Fig. 3D, Table 2). The 19 water-mediated hydrogen bonds also exist between the enzyme and Rha molecules: RA3/O-1=Wat918=Asp187/Oδ2 (2.7 Å); RA3/O-1=Wat828=Lys207/Nζ (2.8 Å) and =Lys207/N (2.9 Å); RA3/O-3=Wat1015=Lys207/Nζ (3.0 Å); RA3/O-3=Wat1056=Arg255/Nη2 (2.9 Å); RA3/O-4=Wat1056=Arg255/Nη2 (2.9 Å); RA3/O-4=Wat714=Thr140/O (2.8 Å) and =Pro142/N (3.1 Å); RA3/O5=Wat1070=Asp-187/Oδ2 (3.2 Å), =Asp187/N (2.8 Å), and =Tyr147/OH (2.4 Å); RA4/O-3=Wat828=Lys207/Nζ (2.8 Å) and =Lys207/N (2.9 Å); RA4/O-3=Wat831=Gly238/O (2.9 Å), =Asn204/O (3.1 Å), and =Asn204/Oδ1 (3.2 Å); RA4/O-4=Wat831=Gly238/O (2.9 Å), =Asn204/O (3.1 Å), and =Asn204/Oδ1 (3.2 Å). van der Waals contacts between RA3 and six amino acid residues (Asp187, Lys207, Arg255, Thr141, Tyr147, and Gly186) and between RA4 and three amino acid residues (Val246, Gly238, and Lys240) were observed. A space between RA3 and RA4 suggests that GalA, which forms a α-1,4 bond with RA3 and α-1,2 bond with RA4, is accommodated at this site. In this case, the basic residues such as Arg255 and/or Lys207 are supposed to stabilize the carboxyl group of the GalA residue.

Rha molecules are unexpectedly bound to the noncatalytic domain in addition to the active cleft. This noncatalytic domain for Rha binding probably function as a carbohydrate-binding module (CBM). Some carbohydrate-active enzymes are appended by one or more noncatalytic CBMs, which are classified into 52 families based on their amino acid sequence similarity and promote association of the enzyme and substrate (36). A CBM family 32 protein, YeCBM32 from Yersinia enterolitica, has been reported to recognize acidic polysaccharides such as pectin, polygalacturonan, and RG-I (37), although most CBMs recognize the neutral polysaccharide such as cellulose, β-1,3 glucans, xylan, and starch. The noncatalytic domain in YesW, however, shows no significant homology with any other CBM proteins, including YeCBM32 in the primary structure. This result probably facilitates the creation of a new CBM family.

Active Site of YesW—Structural superimposition between YesW/Rha and YesW/GalA-GalA (Protein Data Bank code 2Z8S) reveals the binding mode of the substrate Rha and GalA molecules to the active cleft (Fig. 3E). Subsites are defined to label so that -n represents the nonreducing terminus, and n represents the reducing terminus, and cleavage occurs between the -1 and +1 sites (38). RG lyases cleave α-1,4 bonds between Rha and GalA residues in RG chain through the β-elimination reaction. A space between Rha molecules (RA1 and RA2) in YesW/Rha is strongly suggested to accommodate the GalA residue in RG chain. Based on the cleavage site (α-1,4 bonds between Rha and GalA residues) by RG lyases and the orientation of Rha molecules (RA1 and RA2) in YesW/Rha, RA1 and RA2 are considered to be positioned in subsites -1 and +2, respectively. The disaccharide in YesW/GalA-GalA is bound around subsite -2 or -3. We have previously determined the crystal structure of unsaturated galacturonyl hydrolase YteR in complex with ΔGalA-Rha, a reaction product by RG lyase (39). Through use of the coordinates for the disaccharide, the catalytic reaction was structurally simulated through the binding of ΔGalA-Rha at subsite +1 and +2 with reference to the RA2 orientation (Fig. 3E). In that case, Lys170 as well as the calcium ion coordinated by four amino acid residues (Asp153, Asn592, Ala594, and Asn596) probably function as a stabilizer for the carboxyl group of GalA at subsite +1, and Asp172 is a candidate for a catalytic base abstracting C-5 proton of the GalA residue.

Structure Determination of YesX—The YesX crystal belongs to space group P212121 with unit cell parameters of a = 72.9 Å, b = 88.1 Å, and c = 99.3 Å. One molecule is present in an asymmetric unit. Data collection statistics at up to 1.65 Å resolution are shown in Table 1. The initial phase was determined by molecular replacement with the wild-type YesW structure as a reference model. Subsequent model building and refinement contributed to the protein model with 604 of all the 620 amino acid residues.

The refined model includes 604 amino acid residues, 706 water molecules, and 9 calcium ions for one YesX molecule in an asymmetric unit. Two residues at N terminus and 14 residues at C terminus including the histidine-tagged sequence (8 amino acid residues, -LEHHHHHH) could not be assigned in the 2Fo - Fc map. The final overall R factor for the refined model was 16.2% with 72,365 unique reflections within a 37.2-1.65 Å resolution range. The final overall free R factor calculated with randomly selected 5% reflection was 18.4%. The absolute positional error from Luzzati (31) was estimated to be 0.15 Å at a resolution of 1.65 Å. Ramachandran plot analysis (32) shows that 89.3% of nonglycine residues lie within the most favored regions, and 10.1% lie in additionally allowed regions. Three residues (Asn142, Asn466, and Ala578) fell into generously allowed regions. One cispeptide was observed between Glu252 and Pro253 residues. The refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1.

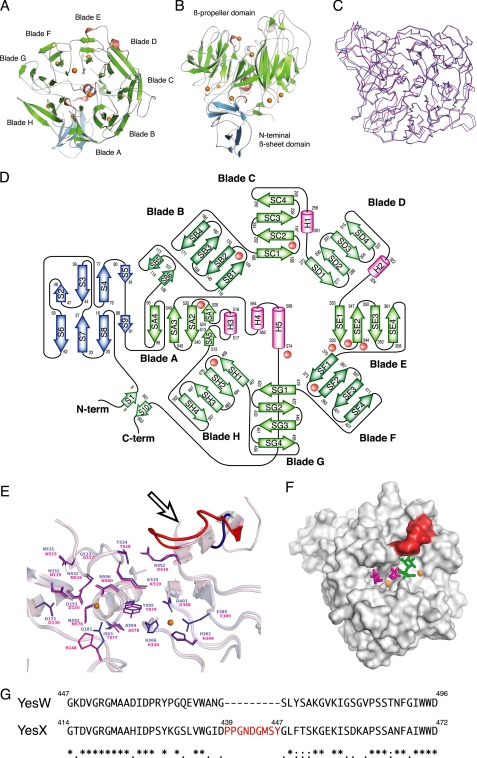

The overall structure (Fig. 4, A and B) and topology of the secondary structure elements (Fig. 4D) indicate that YesX consists of an N-terminal β-sheet domain and an eight-bladed β-propeller domain. Because of the high identity (68.7%) in primary structure between YesX and YesW, the eight-bladed β-propeller of YesX exhibits a significant structural similarity to that of YesW with an root mean square deviation of 0.784 Å for 581 Cα (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Structure of YesX. A, overall structure. B, image in A is turned by 90° around the x axis. C, superimposition of YesW (blue) and YesX (pink). D, topology diagram. β-Sheets are shown as blue or green arrows, and helices are pink cylinders. The calcium ions are shown as orange balls. E, structural comparison of YesW and YesX in the active site. Residues are colored blue for YesW and pink for YesX. A calcium ion is shown as an orange ball. Loop specific for YesX is colored red and indicated by an arrow. F, comparison in the surface structure among YesX, YesW/GalA-GalA, and YesW/Rha. The loop specific for YesX is colored red. Disaccharide is shown by colored elements: oxygen atom, red; carbon atom, green. The calcium ions are shown as orange balls, and GalA and Rha molecules are shown by green and magenta sticks, respectively. G, amino acid sequence alignment of YesW and YesX (GenPept accession number CAB12524 for YesW and CAB12525 for YesX). Amino acid sequences were aligned using the ClustalW program. Identical residues are denoted by asterisks, strongly conserved residues are denoted by colons, and weakly conserved residues are denoted by periods. The inserted sequence, which corresponds to the loop specific for YesX, is shown in red letters.

Structural Superimposition between YesW and YesX on Active Site—The significant structural similarities between YesW and YesX suggest that their mode of action (endo/exo) is determined by a slight structural difference in the catalytic domain. Because the catalytic cleft of YesW was demonstrated above, the active site of YesX was compared with that of YesW through structural superimposition. The catalytically important residues in the active site (17) are well conserved between both (Fig. 4E). Arg452 in YesW corresponds to Arg419 in YesX, and in the same way, Thr534 to Thr518, Lys535 to Lys519, Tyr595 to Tyr579, Gly533 to Gly517, Asn532 to Asn516, Asn531 to Asn515, Asn152 to Asn119, and Asp172 to Asp139. Gln181 in YesW is replaced by His148 in YesX. All residues, which coordinate the calcium ions, are completely conserved. Interestingly, a single loop is found situated over the active site of YesX (Fig. 4E, arrow). The amino acid sequence alignment of YesW and YesX shows that the loop corresponding to nine residues, 439PPGNDGMSY447, is specific for YesX (Fig. 4G). Comparison of the surface structure among YesX, YesW/Rha, and YesW/GalA-GalA indicates that the loop specific for YesX overlays the disaccharide at the nonreducing terminus (Fig. 4F). This suggests that the loop plays an important role in the substrate specificity and mode of action.

Molecular Conversion of Exotype YesX to Endotype Enzyme—To characterize the loop specific for YesX in the active site, a YesX mutant with no loop region was constructed and designated as YesX del_loop mutant. Three enzymes, YesW, YesX, and YesX del_loop mutant, were purified and subjected to enzyme kinetics using RG-I as a substrate (Table 3). In comparison with YesX, YesX del_loop mutant showed much lower Km, suggesting that the mutant has a preferable affinity with the substrate. There is no significant difference in Vmax between the two. The mode of action of YesX del_loop mutant was examined using an RG chain, a mixture of different RG backbone sizes, as a substrate. As described in the previous report (16), YesW releases a tetrasaccharide and larger saccharides as a major product (Fig. 5A), whereas disaccharide was produced at any reaction time as a major product through the YesX reaction (Fig. 5C). This indicates that YesW acts endolytically on the substrate and YesX exolytically. As shown in Fig. 5B, YesX del_loop mutant released oligosaccharides with several polymerization degrees in the early stage of reaction. The resultant oligosaccharides were gradually converted to disaccharides. This strongly demonstrates that the mutant shows the endolytical reaction profile as observed in the reaction of YesW. Judging from the enzyme kinetics, this molecular conversion in the mode of action strongly suggests that the loop prevents YesX from accommodating the larger saccharides in the active site because of steric hindrance.

TABLE 3.

Kinetic parameters for YesW, YesX, and YesX del_loop mutant toward RG-I

| Enzyme | Vmax | Km | Vmax/Km |

|---|---|---|---|

| min−1 | mg ml−1 | min−1 mg−1 ml | |

| YesW | 672 ± 43.4 | 0.181 ± 0.023 | 3710 |

| YesX | 8.8 ± 0.90 | 1.78 ± 0.28 | 4.94 |

| YesX del_loop mutant | 7.7 ± 0.37 | 0.56 ± 0.058 | 13.5 |

FIGURE 5.

Degradation profile of the RG chain. Profiles of the RG chain with YesW (A) YesX (C) and YesX del_loop mutant (B) were periodically analyzed by size exclusion chromatography. The reaction times were 0, 5, 15, 30, and 60 min. Product from RG chain without added enzyme was used as the negative control. All of the profiles are overlaid, and the peaks of tetrasaccharide and disaccharide are indicated by solid and dashed lines, respectively.

Similar molecular conversion studies regarding the mode of action have already been reported for GH families 6 and 43 (40, 41). GH family 6 exocellobiohydrolase from Cellulomonas fimi enhances the endo-β-1,4-glucanase activity by removing a surface loop over the active tunnel based on a structural comparison between Thermomonospora fusca endo-β-1,4-glucanase and Trichoderma reesei exo-β-1,4-glucanase (40). GH family 43 exotype α-l-arabinanase from C. japonicus (CjArb43A) is converted to an endotype enzyme through point mutations D35L/Q316A and/or the insertion of the LTEER loop in Pro55 on the basis of the structural difference between CjArb43A and B. subtilis exotype α-l-arabinanase (BsArb43A) (41). This conversion is based on protein engineering reducing the steric restriction at the subsite -3 specific for the exotype enzyme. More recently, endo/exo conversion in GH families 26, 46, and 74 has been demonstrated (42-44). Although our molecular conversion of exotype YesX to endotype YesW-like enzyme is similar to that of GH families 6 and 74 exohydrolase to endoenzyme by removing a specific loop for exotype enzyme enclosing the active cleft, this is the first example of endo/exo conversion in PLs.

In conclusion, substrate recognition and mode of action together with a novel CBM were identified in PL family 11 through determination of x-ray crystal structures of YesW/Rha and ligand-free YesX. The endo/exo interconversion was achieved by the addition/removal of the loop for recognizing the terminal saccharide.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. K. Hasegawa and S. Baba of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute for kind help in data collection. The diffraction data for crystals were collected at the BL-38B1 station of SPring-8 (Hyogo, Japan) with the approval of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute.

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to K. M. and W. H.) and by Targeted Proteins Research Program (to W. H.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan. Part of this work was supported by Research Fellowships from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists (to A. O.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: GH, glycoside hydrolase; PL, polysaccharide lyase; RG, rhamnogalacturonan; Rha, rhamnose; GalA, galacturonic acid; RG chain, RG-I main chain; ΔGalA-Rha, unsaturated galacturonyl rhamnose; CBM, carbohydrate-binding module.

References

- 1.Coutinho, P. M., and Henrissat, B. (1999) Carbohydrate-active Enzymes: An Integrated Database Approach (Gilbert, H. J., Davies, G., Henrissat, B., and Svensson, B., eds) The Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge

- 2.Yoder, M. D., and Jurnak, F. (1995) Plant Physiol. 107 349-364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayans, O., Scott, M., Connerton, I., Gravesen, T., Benen, J., Visser, J., Pickersgill, R., and Jenkins, J. (1997) Structure 5 677-689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamasaki, M., Ogura, K., Hashimoto, W., Mikami, B., and Murata, K. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 352 11-21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoon, H.-J., Hashimoto, W., Miyake, O., Murata, K., and Mikami, B. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 307 9-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lunin, V. V., Li, Y., Linhardt, R. J., Miyazono, H., Kyogashima, M., Kaneko, T., Bell, A. W., and Cygler, M. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 337 367-386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaya, D., Tocilj, A., Li, Y., Myette, J., Venkataraman, G., Sasisekharan, R., and Cygler, M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 15525-15535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maruyama, Y., Hashimoto, W., Mikami, B., and Murata, K. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 350 974-986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maruyama, Y., Mikami, B., Hashimoto, W., and Murata, K. (2007) Biochemistry 46 781-791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogura, K., Yamasaki, M., Mikami, B., Hashimoto, W., and Murata, K. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 380 373-385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darvill, A. G., McNeil, M., and Albersheim, P. (1978) Plant Physiol. 62 418-422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thakur, B. R., Singh, R. K., and Handa, A. K. (1997) Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 37 47-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNeil, M., Darvill, A. G., Fry, S. C., and Albersheim, P. (1984) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 53 625-663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNeil, M., Darvill, A. G., and Albersheim, P. (1980) Plant Physiol. 66 1128-1134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Neill, M. A., Warrenfeltz, D., Kates, K., Pellerin, P., Doco, T., Darvill, A. G., and Albersheim, P. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 22923-22930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ochiai, A., Itoh, T., Kawamata, A., Hashimoto, W., and Murata, K. (2007) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73 3803-3813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ochiai, A., Itoh, T., Maruyama, Y., Kawamata, A., Mikami, B., Hashimoto, W., and Murata, K. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 37134-37145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shevchik, V. E., Condemine, G., Robert-Baudouy, J., and Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat, N. (1999) J. Bacteriol. 181 3912-3919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashimoto, W., Miyake, O., Momma, K., Kawai, S., and Murata, K. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182 4572-4577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradford, M. M. (1976) Anal. Biochem. 72 248-254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ochiai, A., Yamasaki, M., Itoh, T., Mikami, B., Hashimoto, W., and Murata, K. (2006) Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Crystalliz. Comm. 62 438-440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otwinowski, Z., and Minor, W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276 307-326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vagin, A., and Teplyakov, A. (1997) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 30 1022-1025 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collaborative Computational Project (1994) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50 760-76315299374 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emsley, P., and Cowtan, K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 60 2126-2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A., and Dodson, E. J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53 240-255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kabsch, W. (1976) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 32 922-923 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laskowski, R. A., MacArthur, M. W., Moss, D. S., and Thornton, J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26 283-291 [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeLano, W. L. (2004) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA

- 30.Berman, H. M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T. N., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I. N., and Bourne, P. E. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res. 28 235-242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luzzati, V. (1952) Acta Crystallogr. 5 802-810 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sibanda, B. L., and Thornton, J. M. (1985) Nature 316 170-174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramachandran, G. N., and Sasisekharan, V. (1968) Adv. Protein Chem. 23 283-438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKie, V. A., Vincken, J. P., Voragen, A. G., van den Broek, L. A., Stimson, E., and Gilbert, H. J. (2001) Biochem. J. 355 167-177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pages, S., Valette, O., Abdou, L., Belaich, A., and Belaich, J. P. (2003) J. Bacteriol. 185 4727-4733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boraston, A. B., Bolam, D. N., Gilbert, H. J., and Davies, G. J. (2004) Biochem. J. 382 769-781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abbott, D. W., Hrynuik, S., and Boraston, A. B. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 367 1023-1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davies, G. J., Wilson, K. S., and Henrissat, B. (1997) Biochem. J. 321 557-559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Itoh, T., Ochiai, A., Mikami, B., Hashimoto, W., and Murata, K. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 347 1021-1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meinke, A., Damude, H. G., Tomme, P., Kwan, E., Kilburn, D. G., Miller, R. C., Jr., Warren, R. A., and Gilkes, N. R. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 4383-4386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Proctor, M. R., Taylor, E. J., Nurizzo, D., Turkenburg, J. P., Lloyd, R. M., Vardakou, M., Davies, G. J., and Gilbert, H. J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 2697-2702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao, Y. Y., Shrestha, K. L., Wu, Y. J., Tasi, H. J., Chen, C. C., Yang, J. M., Ando, A., Cheng, C. Y., and Li, Y. K. (2008) Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 21 561-566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yaoi, K., Kondo, H., Hiyoshi, A., Noro, N., Sugimoto, H., Tsuda, S., Mitsuishi, Y., and Miyazaki, K. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 370 53-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cartmell, A., Topakas, E., Ducros, V. M., Suits, M. D., Davies, G. J., and Gilbert, H. J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 34403-34413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]