Abstract

F18-fimbriated Escherichia coli are associated with porcine postweaning diarrhea and edema disease. Adhesion of F18-fimbriated bacteria to the small intestine of susceptible pigs is mediated by the minor fimbrial subunit FedF. However, the target cell receptor for FedF has remained unidentified. Here we report that F18-fimbriated E. coli selectively interact with glycosphingolipids having blood group ABH determinants on type 1 core, and blood group A type 4 heptaglycosylceramide. The minimal binding epitope was identified as the blood group H type 1 determinant (Fucα2Galβ3GlcNAc), while an optimal binding epitope was created by addition of the terminal α3-linked galactose or N-acetylgalactosamine of the blood group B type 1 determinant (Galα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAc) and the blood group A type 1 determinant (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)-Galβ3GlcNAc). To assess the role of glycosphingolipid recognition by F18-fimbriated E. coli in target tissue adherence, F18-binding glycosphingolipids were isolated from the small intestinal epithelium of blood group O and A pigs and characterized by mass spectrometry and proton NMR. The only glycosphingolipid with F18-binding activity of the blood group O pig was an H type 1 pentaglycosylceramide (Fucα2Galβ3GlcNAc-β3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer). In contrast, the blood group A pig had a number of F18-binding glycosphingolipids, characterized as A type 1 hexaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), A type 4 heptaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GalNAcβ3Galα4Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), A type 1 octaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), and repetitive A type 1 nonaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GalNAcα3-(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer). No blood group antigen-carrying glycosphingolipids were recognized by a mutant E. coli strain with deletion of the FedF adhesin, demonstrating that FedF is the structural element mediating binding of F18-fimbriated bacteria to blood group ABH determinants.

Enterotoxigenic (ETEC)4 and verotoxigenic Escherichia coli are important causes of disease in man and animal (1, 2). In newly weaned pigs, F18-fimbriated E. coli producing entero- and/or Shiga-like toxins induce diarrhea and/or edema disease, which accounts for substantial economical losses in the pig industry (3). Two virulence factors are of major importance, namely the F18 fimbriae, the adhesive polymeric protein surface appendages of F18-fimbriated E. coli, and the Shiga-like toxin (SLT-IIv), or enterotoxins (STa or STb), that are produced by the bacterium. F18 fimbriae are expressed by the fed (fimbriae associated with edema disease) gene cluster, with fedA encoding the major subunit, fedB the outer membrane usher, fedC the periplasmic chaperone, whereas fedE and fedF encode minor subunits (4). FedF is the adhesive subunit and is presumably located at the tip of the fimbrial structure (5, 6). Typically, tip adhesins consist of two domains: an N-terminal carbohydrate-specific lectin domain and a C-terminal pilin domain (7), which needs to be donor-strand-complemented to stabilize its incomplete Ig fold (8, 9). Crystal structures of the lectin domains of type 1 pili, P pili, and F17 fimbrial adhesins reveal that they all have the immunoglobulin-like (Ig-like) fold in common, which is remarkable, because they show little to no sequence identity (10). N-terminal truncation has enabled crystallization of the FedF adhesin, and elucidation of its crystal structure will shed light on the interaction with the natural receptor on the intestinal epithelium (11).

A crucial step in the pathogenesis of the F18-fimbriated E. coli-induced diarrhea/edema is the initial attachment of the bacteria to a specific receptor (F18R) on the porcine intestinal epithelium. However, some pigs are resistant to colonization by F18-fimbriated E. coli, due to lack of F18R expression. The F18R status of pigs is genetically determined (12), with the gene controlling expression of F18R mapped to the halothane linkage group on pig chromosome 6 (13, 14). This locus contained two candidate genes, FUT1 and FUT2, both encoding α2-fucosyltransferases. Expression analysis of these two genes in the porcine small intestine revealed that the FUT2 gene is differentially expressed, whereas the FUT1 gene is expressed in all examined pigs (15). Sequencing of the FUT1 gene of pigs being either susceptible or resistant to infection by F18-fimbriated E. coli showed a polymorphism (G or A) at nucleotide 307. Presence of the A nucleotide on both alleles (FUT1A/A genotype) led to significantly reduced enzyme activity, corresponding to the F18-fimbriated E. coli-resistant genotype, whereas susceptible pigs had either the heterozygous FUT1G/A or the homozygous FUT1G/G genotype. These findings have led to the development of a PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism test to differentiate between F18R-positive and F18R-negative pigs.

Although substantial information exists regarding the genetics of F18R, the identity and nature of the F18R molecule have remained unclear. In this report, F18R was found to be of glycosphingolipid nature. Consequently, a collection of glycosphingolipids from various sources was tested for binding with F18-fimbriated E. coli, demonstrating a specific interaction of recombinant F18-expressing bacteria with blood group ABH determinants on type 1 core chains. The role of the FedF adhesin in this binding process was defined by using a FedF-negative mutant strain (5). Knowledge of the F18R structure could provide better insights into the interactions between F18-fimbriated E. coli and the porcine gut, and may, additionally, lead to the design of potent inhibitors of adherence for use in anti-adhesive therapy (16).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains, Culture Conditions, and Labeling

The wild-type verotoxigenic F18-positive E. coli reference strain 107/86 (serotype O139:K12:H1, F18ab+, SLT-IIv+) (17), and the wild-type enterotoxigenic F4ac-positive E. coli reference strain GIS 26 (serotype O149:K91:F4ac, LT+, STa+, STb+), were cultured on BHI agar plates (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England) at 37 °C for 18 h. Subsequently, the bacteria were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.3). The concentration of bacteria in the suspension was determined by measuring the optical density at 660 nm (A660). An optical density of 1 equals 109 bacteria per milliliter, as determined by counting colony forming units.

Recombinant E. coli strains expressing whole F18 fimbriae (HB101(pIH120), or F18 fimbriae with deletion of the FedF adhesive subunit (HB101(pIH126)) (4, 5) were grown on Iso Sensitest agar plates (Oxoid) supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) at 37 °C overnight. For metabolic labeling, the culture plates were supplemented with 10 μl of [35S]methionine (400 μCi, Amersham Biosciences). Bacteria were harvested, washed three times in PBS, and resuspended in PBS containing 2% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.1% (w/v) NaN3, and 0.1% (w/v) Tween 20 (BSA/PBS/Tween) to a bacterial density of 1 × 108 colony forming units/ml. The specific activity of bacterial suspensions was ∼1 cpm per 100 bacteria. The same conditions (with omission of ampicillin) were used for culture and labeling of the background E. coli strain HB101.

In Vitro Villous Adhesion Assay

The physio-chemical properties of F18R on porcine small intestinal villous enterocytes was investigated using an in vitro villous adhesion inhibition assay (18, 19). Briefly, a 20-cm intestinal segment was collected from the mid jejunum of a euthanized pig, rinsed three times with ice-cold PBS, and fixed with Krebs-Henseleit buffer (160 mm, pH 7,4) containing 1% (v/v) formaldehyde for 30 min at 4 °C. Thereafter, the villi were gently scraped from the mucosae with a glass slide and stored in Krebs-Henseleit buffer at 4 °C. Treatment of villi with acetone, methanol, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mm NaIO4 in 0.2 m sodium acetate, pH 4.5, or 0.2 m sodium acetate, pH 4.5, without NaIO4, respectively, was performed at room temperature on a rotating wheel in a volume of 500 μl during 1 h. Next, the villi were washed six times with Krebs-Henseleit buffer followed by addition of 4 × 108 bacteria of the F18-positive reference E. coli strain (107/86), or the F4ac-expressing E. coli strain GIS 26, to an average of 50 villi in a total volume of 500 μl of PBS, supplemented with 1% (w/v) d-mannose to prevent adhesion mediated by type 1 pili. These mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 1 h while being gently shaken. Villi were examined by phase-contrast microscopy at a magnification of 600, and the number of bacteria adhering along a 50-μm brush border was quantitatively evaluated by counting the number of adhering bacteria at 20 randomly selected places, after which the mean bacterial adhesion was calculated.

Reference Glycosphingolipids

Total acid and non-acid glycosphingolipid fractions were prepared as described before (20), and the individual glycosphingolipids were obtained by repeated chromatography on silicic acid columns and by high-performance liquid chromatography, and identified by mass spectrometry and proton NMR spectroscopy (20).

TLC

Aluminum- or glass-backed silica gel 60 high-performance TLC plates (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) were used for TLC and eluted with chloroform/methanol/water (60:35:8, by volume) as the solvent system. The different glycosphingolipids were applied to the plates in quantities of 0.002–4 μg of pure glycosphingolipids, and 40 μg of glycosphingolipid mixtures. Chemical detection was done with anisaldehyde (21).

Chromatogram Binding Assay

Binding of radiolabeled bacteria to glycosphingolipids on thin-layer chromatograms was done as described before (20), with minor modifications. Dried chromatograms were dipped in diethylether/n-hexane (1:5 v/v) containing 0.5% (w/v) polyisobutylmethacrylate for 1 min, dried, and then blocked with BSA/PBS/Tween for 2 h at room temperature. Thereafter, the plates were incubated with 35S-labeled bacteria (1–5 × 106 cpm/ml) diluted in BSA/PBS/Tween for another 2 h at room temperature. After washing six times with PBS, and drying, the thin-layer plates were autoradiographed for 12 h using XAR-5 x-ray films (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Chromatogram binding assays with monoclonal antibodies directed against the blood group A determinant (DakoCytomation Norden A/S, Glostrup, Denmark) were done as described (22), using 125I-labeled anti-mouse antibodies for detection.

Isolation of F18-binding Glycosphingolipids from Porcine Small Intestinal Mucosa

Non-acid glycosphingolipids were isolated from mucosal scrapings from porcine small intestines as described (20). Briefly, the mucosal scrapings were lyophilized and then extracted in two steps in a Soxhlet apparatus with chloroform and methanol (2:1 and 1:9, by volume, respectively). The material obtained was subjected to mild alkaline hydrolysis and dialysis, followed by separation on a silicic acid column. Acid and non-acid glycosphingolipid fractions were obtained by chromatography on a DEAE-cellulose column. To separate the non-acid glycolipids from alkali-stable phospholipids, this fraction was acetylated and separated on a second silicic acid column, followed by deacetylation and dialysis. Final purifications were done by chromatographies on DEAE-cellulose and silicic acid columns. The total non-acid glycosphingolipid fractions obtained were thereafter separated, as described below. Throughout the separation procedures aliquots of the fractions obtained were analyzed by TLC, and fractions that were colored green by anisaldehyde were tested for binding of F18-fimbriated E. coli using the chromatogram binding assay.

Blood Group O Pig Intestinal Mucosa—A total non-acid glycosphingolipid fraction (148 mg) from blood group O pig intestinal mucosa was first separated on a silicic acid column eluted with increasing volumes of methanol in chloroform. Thereby, an F18-fimbriated E. coli binding fraction containing tetraglycosylceramides and more slow-migrating compounds (22 mg) was obtained. This fraction was further separated on an Iatrobeads (Iatrobeads 6RS-8060; Iatron Laboratories, Tokyo) column (10 g), first eluted with chloroform/methanol/water (60:35:8, by volume), 10 × 5 ml, followed by chloroform/methanol/water (40:40:12, by volume), 2 × 10 ml. The F18-fimbriated E. coli binding compound eluted in fractions 3 and 4, and after pooling of these fractions 6.7 mg was obtained. This material was acetylated and further separated on an Iatrobeads column (2 g), eluted with increasing volumes of methanol in chloroform. After deacetylation and dialysis, 6.0 mg of pure F18-binding glycosphingolipid (designated fraction O-I) was obtained.

Blood Group A Pig Intestinal Mucosa—A total non-acid glycosphingolipid fraction (183 mg) from blood group A pig intestinal mucosa was initially separated on a silicic acid column eluted with increasing volumes of methanol in chloroform. Pooling of fractions containing tetraglycosylceramides and more slowly migrating compounds yielded 51.2 mg. This material was further separated by high-performance liquid chromatography on a 1.0- × 25-cm silica column (Kromasil Silica, 10-μm particles, Skandinaviska Genetec, Kungsbacka, Sweden) eluted with a linear gradient of chloroform/methanol/water (70:25:4 to 40:40:12, by volume) during 180 min and with a flow of 2 ml/min. The fractions obtained were pooled according to mobility on thin-layer chromatograms and F18-fimbriated E. coli binding activity. Thereby, six F18-fimbriated E. coli binding fractions were obtained, designated fraction A-I (12.6 mg), A-II (3.6 mg), A-III (0.3 mg), A-IV (0.5 mg), A-V (0.2 mg), and A-VI (0.2 mg), respectively.

Negative Ion FAB MS

Negative ion FAB mass spectra were recorded on a JEOL SX-102A mass spectrometer (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). The ions were produced by 6 keV xenon atom bombardment using triethanolamine (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) as matrix and an accelerating voltage of –10 kV.

Endoglycoceramidase Digestion and LC/MS

Endoglycoceramidase II from Rhodococcus spp. (23) (Takara Bio Europe S.A., Gennevilliers, France) was used for hydrolysis of glycosphingolipids. Briefly, 50 μg of F18-fimbriated E. coli binding fraction O-I from blood group O porcine intestinal mucosa, H type 1 pentaglycosylceramide from human meconium, and H type 2 pentaglycosylceramide from human erythrocytes were resuspended in 100 μl of 0.05 m sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.0, containing 120 μg of sodium cholate, and sonicated briefly. Thereafter, 1 milliunit of endoglycoceramidase II was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. The reaction was stopped by addition of chloroform/methanol/water to the final proportions 8:4:3 (by volume). The oligosaccharide-containing upper phase thus obtained was separated from detergent on a Sep-Pak QMA cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA). The eluant containing the oligosaccharides was dried under nitrogen and under vacuum.

For LC/MS the glycosphingolipid-derived saccharides were separated on a column (200 × 0.180 mm) packed in-house with 5-μm porous graphite particles (Hypercarb, Thermo Scientific), and eluted with a linear gradient from 0%B to 45%B in 46 min (Solvent A: 8 mm NH4HCO3; Solvent B: 20% 8 mm NH4HCO3/80% acetonitrile (by volume)). Eluted saccharides were analyzed in the negative mode on an LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron, San Jose, CA), using Xcalibur software.

Proton NMR Spectroscopy

1H NMR spectra were acquired on a Varian 600-MHz spectrometer at 30 °C. Samples were dissolved in DMSO/D2O (98:2, by volume) after deuterium exchange.

Carbohydrate Inhibition Assay

The ability of soluble oligosaccharides to interfere with the binding of F18-fimbriated E. coli to porcine small intestinal cells was evaluated in the in vitro villous adhesion assay. The F18-positive E. coli strain 107/86 (8 × 107 bacteria) was incubated with different concentrations (10 mg/ml, 1 mg/ml, 100 μg/ml) of blood group H type 1 pentasaccharide (Fucα2Galβ3GlcNAcβ3-Galβ4Glc) or lacto-N-tetraose saccharide (Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glc) (Glycoseparations, Moscow, Russia) in a final volume of 100 μl of PBS, for 1 h at room temperature, while being gently shaken. The mixtures were then added to the villi, and again incubated for 1 h at room temperature with gentle shaking. Thereafter, the villi were examined by phase-contrast microscopy, and adhering bacteria were quantitated as described above. Villi of two different F18R-positive pigs were used, and the counts were performed in triplicate. The pigs used were found to be blood group H type 1 and 2 positive, and blood group A type 2 negative, by indirect immunofluorescence using blood group-specific monoclonal antibodies (clone 17-206, GeneTex, Inc., San Antonio, TX; clone 92FR-A2, Abcam, Cambridge, UK; clone 29.1 Sigma-Aldrich), and fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled secondary anti-mouse antibody (Sigma-Aldrich).

RESULTS

Determination of the Physiochemical Properties of F18R

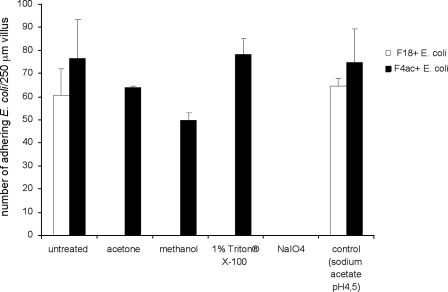

To examine the physiochemical characteristics of F18R, intestinal villi isolated from four pigs were treated with different agents that affect lipids or carbohydrates on the cell membrane. Treatment was followed by assessment of adhesion of F18-fimbriated E. coli to the villus epithelium. The adhesion of F18-fimbriated E. coli to porcine intestinal villi was completely abolished after treatment with acetone, methanol, 1% Triton X-100, and NaIO4 (Fig. 1), suggesting that F18R is a glycolipid. In contrast, the adhesion of the control F4ac-fimbriated E. coli strain, having a glycoprotein receptor (24), was only abolished by incubation with NaIO4, whereas treatment with acetone, methanol, and 1% Triton X-100 had no or only little effect.

FIGURE 1.

Effects of treatment with acetone, methanol, 1% Triton X-100 and NaIO4, on the adherence of F18-fimbriated E. coli and F4ac-fimbriated E. coli to porcine intestinal villi. The assay was performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The black gray correspond to the number of adhering F4ac-fimbriated E. coli, and the white bars correspond to the number of adhering F18-fimbriated E. coli.

Screening for F18 Carbohydrate Recognition by Binding to Mixtures of Glycosphingolipids

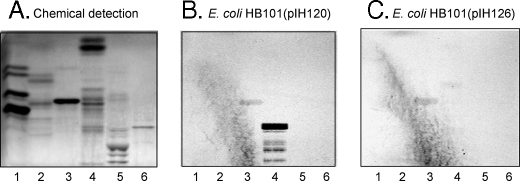

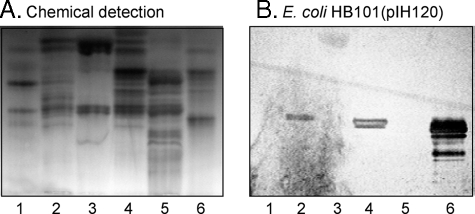

The suggested glycolipid binding of F18-fimbriated E. coli was next investigated by binding to glycosphingolipids separated on thin-layer plates. The initial screening for F18-fimbriated E. coli carbohydrate-binding activity was done by using mixtures of glycosphingolipids from various sources, to expose the bacteria to a large number of potentially binding-active carbohydrate structures. Thereby, a distinct binding of the F18-expressing E. coli strain HB101(pIH120) to slow migrating minor non-acid glycosphingolipids from black and white rat intestine was obtained (Fig. 2B, lane 4). Notably, these compounds were not recognized by the E. coli strain HB101(pIH126), having a deletion of the FedF adhesin (Fig. 2C). A weak binding of both the F18-expressing strain HB101(pIH120) and the FedF deletion strain HB101(pIH126) to the major compound (gangliotriaosylceramide) of the non-acid glycosphingolipid fraction of guinea pig erythrocytes (lane 3) was also observed. Binding to this gangliotriaosylceramide was also obtained with the HB101 background strain (not shown) and was most likely due to the relatively large amounts of this compound on the thin-layer chromatograms.

FIGURE 2.

Binding of recombinant E. coli expressing F18 fimbriae (strain HB101(pIH120)), and F18 fimbriae with deletion of the FedF adhesin (strain HB101(pIH126)), to mixtures of glycosphingolipids on thin-layer chromatograms. Chemical detection by anisaldehyde (A), and autoradiograms obtained by binding of 35S-labeled bacterial cells (B and C). The glycosphingolipids were separated on aluminum-backed silica gel plates, using chloroform/methanol/water (60:35:8, by volume) as solvent system, and the binding assays were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The lanes are: lane 1, non-acid glycosphingolipids of human blood group O erythrocytes, 40 μg; lane 2, non-acid glycosphingolipids of dog intestine, 40 μg; lane 3, non-acid glycosphingolipids of guinea pig intestine, 40 μg; lane 4, non-acid glycosphingolipids of black and white rat intestine, 40 μg; lane 5, calf brain gangliosides, 40 μg; and lane 6, acid glycosphingolipids of human blood group O erythrocytes, 40 μg. Autoradiography was for 12 h.

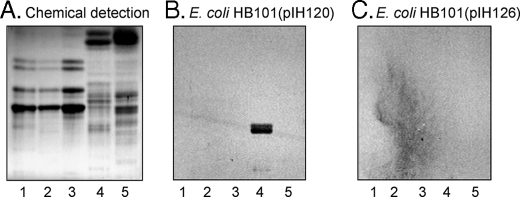

A characteristic feature of black and white rat intestine is the presence of glycosphingolipids with blood group A determinants on type 1 (Galβ3GlcNAc) core chains, whereas in white rat intestine blood group A-terminated glycosphingolipids are absent (25). When binding of the F18-positive strain HB101-(pIH120) to non-acid glycosphingolipids from white rat intestine was examined (Fig. 3, lane 5), no binding of the bacteria to this fraction (lane 5) occurred, in contrast to the distinct binding of the bacteria to the non-acid glycosphingolipid fraction from black and white rat intestine (Fig. 3B, lane 4). A further observation was the absence of binding of the F18-fimbriated bacteria to the non-acid glycosphingolipids from human blood group A, B, or O erythrocytes (lanes 1–3), where the predominant glycosphingolipids with blood group A, B, and H determinants have type 2 (Galβ4GlcNAc) core chains (26–28). Once again, no glycosphingolipid was recognized by the FedF deletion mutant HB101(pIH126) (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

Binding of recombinant E. coli expressing F18 fimbriae (strain HB101(pIH120)), and F18 fimbriae with deletion of the FedF adhesin (strain HB101(pIH126)), to mixtures of glycosphingolipids on thin-layer chromatograms. Chemical detection by anisaldehyde (A), and autoradiograms obtained by binding of 35S-labeled bacteria (B and C). The glycosphingolipids were separated on aluminum-backed silica gel plates, using chloroform/methanol/water (60:35:8, by volume) as solvent system, and the binding assay was performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The lanes are: lane 1, non-acid glycosphingolipids of human blood group A erythrocytes, 40 μg; lane 2, non-acid glycosphingolipids of human blood group B erythrocytes, 40 μg; lane 3, non-acid glycosphingolipids of human blood group O erythrocytes, 40 μg; lane 4, non-acid glycosphingolipids of black and white rat intestine, 40 μg; and lane 5, non-acid glycosphingolipids of white rat intestine, 40 μg. Autoradiography was for 12 h.

In summary, the binding of the F18-fimbriated bacteria to slow migrating minor non-acid glycosphingolipids from black and white rat intestine suggested a specific recognition of blood group determinants on type 1 core chains. Furthermore, the absence of binding of the FedF deletion mutant to these compounds indicated an involvement of the FedF protein in the interaction.

Binding of F18-fimbriated E. coli to Pure Reference Glycosphingolipids

Binding assays using pure reference glycosphingolipids in defined amounts confirmed the suggested binding of F18-fimbriated E. coli to blood group determinants on type 1 core chains. The results are exemplified in Fig. 4 and summarized in Table 1. Thus, the F18-expressing E. coli bound to all glycosphingolipids with blood group A, B, or H determinants on type 1 core chains, as the H type 1 pentaglycosylceramide (Fucα2Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer,5 Fig. 4, lane 1), the B type 1 hexaglycosylceramide (Galα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer, Fig. 4, lane 3), the A type 1 hexaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer, Fig. 4, lane 5), the A type 1 heptaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3(Fucα4)GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer, Fig. 4, lane 7), and the B type 1 heptaglycosylceramide (Galα3(Fucα2)Galβ3(Fucα4)GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer, Fig. 4, lane 9). In contrast, no type 2 core counterparts of these compounds were recognized by the F18-fimbriated bacteria, as the H type 2 pentaglycosylceramide (Fucα2Galβ4GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer, Fig. 4, lane 2), the B type 2 hexaglycosylceramide (Galα3(Fucα2)Galβ4GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer, Fig. 4, lane 4), the A type 2 hexaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ4GlcNAcβ3 Galβ4Glcβ1Cer, Fig. 4, lane 6), or the A type 2 heptaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ4(Fucα4)GlcNAcβ3 Galβ4Glcβ1Cer, Fig. 4, lane 8).

FIGURE 4.

Binding of recombinant E. coli expressing F18 fimbriae (strain HB101(pIH120)) to pure glycosphingolipids on thin-layer chromatograms. The glycosphingolipids were separated on aluminum-backed silica gel plates and visualized with anisaldehyde (A). Duplicate chromatograms were incubated with 35S-labeled bacteria (B), followed by autoradiography for 12 h, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The solvent system used was chloroform/methanol/water (60:35:8, by volume). The lanes are: lane 1, H5 type 1 pentaglycosylceramide (Fucα2Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), 4 μg; lane 2, H5 type 2 pentaglycosylceramide (Fucα2Galβ4GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), 4 μg; lane 3, B6 type 1 hexaglycosylceramide (Galα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), 4 μg; lane 4, B6 type 2 hexaglycosylceramide (Galα3(Fucα2)Galβ4GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), 4 μg; lane 5, A6 type 1 hexaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), 4 μg; lane 6, A6 type 2 hexaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ4GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), 4 μg; lane 7, A7 type 1 heptaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3(Fucα4)GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), 4μg; lane 8, A7 type 2 heptaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ4(Fucα3)GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), 4 μg; and lane 9, B7 type 1 heptaglycosylceramide (Galα3(Fucα2)Galβ3(Fucα4)GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), 4 μg.

TABLE 1.

Binding of 35S-labeled recombinant F18 fimbriae-expressing E. coli (pIH120) and recombinant E. coli expressing F18 fimbriae with deletion of the tip subunit (pIH126), to glycosphingolipids on thin-layer chromatograms

| No. and trivial name | Structure | pIH120 | pIH126 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple compounds | |||

| 1) Galactosylceramide | Galβ1Cer | -a | - |

| 2) Glucosylceramide | Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 3) Sulfatide | SO3-3Galβ1Cer | - | - |

| 4) LacCer (d18:1-16:0-24:0)b | Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 5) LacCer (t18:0-h16:0-h24:0) | Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 6) Isoglobotri | Galα3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 7) Globotri | Galα4Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 8) A-4 | GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| Ganglioseries | |||

| 9) GgO3 | GalNAcβ4Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 10) GgO4 | Galβ3GalNAcβ4Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 11) Fuc-GgO4 | Fucα2Galβ3GalNAcβ4Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 12) Sulf-GgO4 | SO3-3Galβ3GalNAcβ4Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| Neolactoseries | |||

| 13) Neolactotetra | Galβ4GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 14) H5 type 2 | Fucα2Galβ4GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 15) B5 | Galα3Galβ4GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 16) B6 type 2 | Galα3(Fucα2)Galβ4GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 17) A6 type 2 | GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ4GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 18) B7 type 2 | Galα3(Fucα2)Galβ4(Fucα3)GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 19) A7 type 2 | GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ4(Fucα3)GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| Lactoseries | |||

| 20) Lactotetra | Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 21) Lea-5 | Galβ3(Fucα4)GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 22) Leb-6 | Fucα2Galβ3(Fucα4)GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 23) H5 type 1 | Fucα2Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | + | - |

| 24) B6 type 1 | Galα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | +++ | - |

| 25) A6 type 1 | GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | +++ | - |

| 26) A7 type 1 | GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3(Fucα4)GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | ++ | - |

| 27) B7 type 1 | Galα3(Fucα2)Galβ3(Fucα4)GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | ++ | - |

| 28) A8 type 1 | GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβGalβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | +c | - |

| 29) A9 type 1 | GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | +c | - |

| Globoseries | |||

| 30) Globotetra | GalNAcβ3Galα4Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 31) Forssman | GalNAcα3GalNAcβ3Galα4Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 32) A7 type 4 | GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GalNAcβ3Galα4Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | ++ | - |

| Gangliosides | |||

| 33) NeuGc-GM3 | NeuGcα3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 34) NeuGc-GM1 | Galβ3GalNAcβ4(NeuGcα3)Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 35) NeuAc-GM1 | Galβ3GalNAcβ4(NeuAcα3)Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 36) NeuAc-GD1b | Galβ3GalNAcβ4(NeuAcα8NeuAcα3)Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

| 37) NeuAcα3SPG | NeuAcα3Galβ4GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer | - | - |

Binding is defined as follows: +++ denotes a binding when <0.1 μg of the glycosphingolipid was applied on the thin-layer chromatogram, whereas ++ denotes a binding when <1 μg of the glycosphingolipid was applied, + denotes a binding at 1-2 μg, and - denotes no binding even at 4 μg.

In the shorthand nomenclature for fatty acids and bases, the number before the colon refers to the carbon chain length, and the number after the colon gives the total number of double bonds in the molecule. Fatty acids with a 2-hydroxy group are denoted by the prefix h before the abbreviation e.g. h16:0. For long chain bases, d denotes dihydroxy and t trihydroxy. Thus d18:1 designates sphingosine (1,3-dihydroxy-2-aminooctadecene) and t18:0 phytosphingosine (1,3,4-trihydroxy-2-aminooctadecene).

The relative affinities of the F18-fimbriated E. coli for compounds No. 28 and No. 29 could not be evaluated because they occurred in a mixture.

Notably, none of the glycosphingolipids with blood group A, B, or H determinants on type 1 core chains, recognized by the F18-fimbriated bacteria, were bound by the FedF deletion mutant strain HB101(pIH126) (Table 1), demonstrating that the FedF protein is the structural element responsible for binding to the blood group A, B, or H type 1-carrying glycosphingolipids.

In addition to these compounds with terminal blood group A/B/H determinants a number of other pure glycosphingolipids were examined for F18-binding activity using the chromatogram binding assay, but no further binding active glycosphingolipids were detected (Table 1).

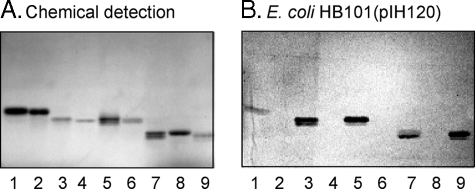

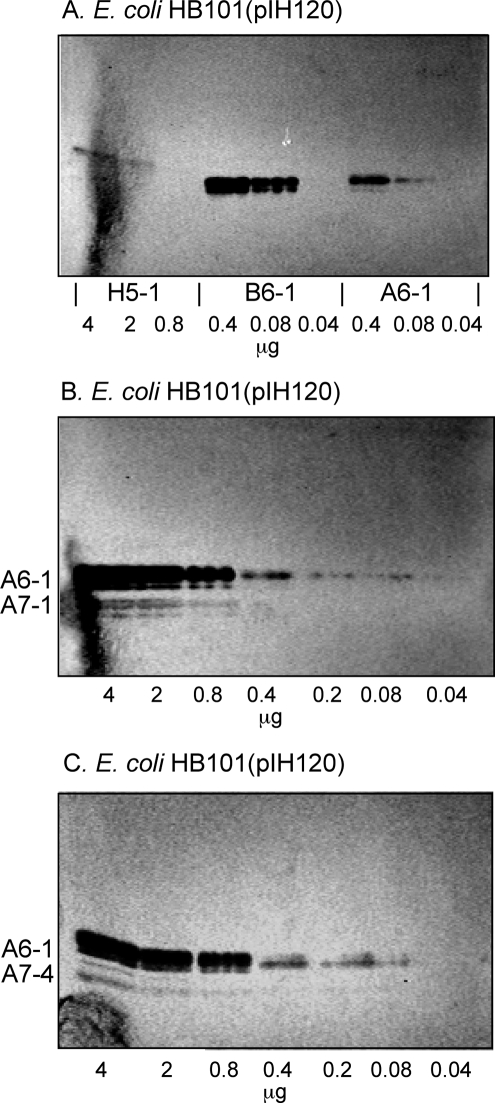

Comparisons of the relative binding affinity of the F18-fimbriated E. coli for the various binding-active glycosphingolipids was done using dilutions of glycosphingolipids on thin-layer chromatograms. As shown in Fig. 5A, the detection limit for the H type 1 pentaglycosylceramide was 2 μg, whereas the detection limit for the A type 1 hexaglycosylceramide and the B type 1 hexaglycosylceramide were ∼0.08 μg.

FIGURE 5.

Binding of recombinant E. coli expressing F18 fimbriae (strain HB101(pIH120)) to dilutions of pure glycosphingolipids on thin-layer chromatograms. The glycosphingolipids were separated on aluminum-backed silica gel plates, using chloroform/methanol/water (60:35:8, by volume) as solvent system. The chromatograms were incubated with 35S-labeled F18 fimbriated E. coli (strain pIH120), followed by autoradiography for 12 h, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The lanes in A are: lane 1, H type 1 pentaglycosylceramide (Fucα2Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), 4 μg; lane 2, H type 1 pentaglycosylceramide, 2 μg; lane 3, H type 1 pentaglycosylceramide, 0.08 μg; lane 4, B type 1 hexaglycosylceramide (Galα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), 0.4 μg; lane 5, B type 1 hexaglycosylceramide, 0.08 μg; lane 6, B type 1 hexaglycosylceramide, 0.04 μg; lane 7, A type 1 hexaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), 0.4 μg; lane 8, A type 1 hexaglycosylceramide, 0.08 μg; and lane 9, A type 1 hexaglycosylceramide, 0.04 μg. The lanes in B are dilutions (4–0.04 μg) of A type 1 hexaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer) and A type 1 heptaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3-(Fucα2)Galβ3(Fucα4)GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer). The lanes in C were dilutions (4–0.04 μg) of A type 1 hexaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3-(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer) and A type 4 heptaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GalNAcβ3Galα4Galβ4Glcβ1Cer).

Because lactotetraosylceramide (Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer; No. 20 in Table 1), having an unsubstituted type 1 core chain, was devoid of FedF-mediated binding activity, the terminal α2-linked fucose of the H type 1 pentaglycosylceramide (Fucα2Galβ3GlcNAcβ3-Galβ4Glcβ1Cer) was necessary for binding to occur. Of interest in this context is the absence of binding of the F18-fimbriated bacteria to fucosylgangliotetraosylceramide (Fucα2Galβ3GalNAcβ4Galβ4Glcβ1Cer; No. 11 in Table 1), demonstrating that the internal N-acetylglucosamine also contributes to the binding process. Furthermore, the higher affinity for the B type 1 hexaglycosylceramide (Galα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), and the A type 1 hexaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), demonstrated that the terminal α3-linked galactose/N-acetylgalactosamine of these compounds contributed substantially to the interaction.

The comparison of the binding of F18-positive bacteria to the A type 1 hexaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer) and the A type 1 heptaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3(Fucα4)GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer) is shown in Fig. 5B. The detection limit for the A type 1 hexaglycosylceramide was ∼0.08 μg and for the A type 1 heptaglycosylceramide 0.8 μg, demonstrating that substitution of the N-acetylglucosamine with an α-fucose in 4-position constitutes a relative hindrance for binding of the FedF protein. This suggestion is corroborated by the fact that the Leb hexaglycosylceramide (Fucα2Galβ3(Fucα4)GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer; No. 22 in Table 1) is not recognized by the F18-expressing E. coli, although it has the Fucα2Galβ3GlcNAc sequence of the binding active H type 1 pentaglycosylceramide.

Thus, the minimal binding epitope of the FedF adhesin of F18 fimbriae is the linear Fucα2Galβ3GlcNAc sequence, and an optimal binding epitope is created by the addition of the α3-linked galactose or N-acetylgalactosamine of the Galα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAc and GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAc sequences.

Binding of F18-fimbriated E. coli to Glycosphingolipids from Porcine Small Intestinal Epithelium

To assess the potential role of the glycosphingolipid recognition by F18-fimbriated E. coli in target tissue adherence, the binding of the F18-expressing E. coli strain HB101(pIH120), and FedF deletion mutant strain HB101(pIH126), to acid and non-acid glycosphingolipid fractions from porcine small intestinal epithelium was determined (Fig. 6). No binding to the acid glycosphingolipids (lanes 3 and 5) occurred. However, in the non-acid fractions from 3-day-old piglet (lane 2), and in the two adult pigs (lanes 4 and 6), a distinct binding to some compounds was obtained with the F18-fimbriated strain (Fig. 6B) while no binding of the FedF deletion mutant strain to these compounds occurred (not shown).

FIGURE 6.

Binding of recombinant E. coli expressing F18 fimbriae (strain HB101(pIH120)) to mixtures of glycosphingolipids from porcine small intestinal epithelium on thin-layer chromatograms. The glycosphingolipids were separated on aluminum-backed silica gel plates and visualized with anisaldehyde (A). Duplicate chromatograms were incubated with 35S-labeled bacteria (B), followed by autoradiography for 12 h, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The solvent system used was chloroform/methanol/water (60:35:8, by volume). The lanes are: lane 1, non-acid glycosphingolipids of rabbit small intestine, 40 μg; lane 2, non-acid glycosphingolipids of 3-day-old piglet small intestinal epithelium, 40 μg; lane 3, acid glycosphingolipids of 3-day-old piglet small intestinal epithelium, 40 μg; lane 4, non-acid glycosphingolipids of adult pig small intestinal epithelium (pig No. 1), 40μg; lane 5, acid glycosphingolipids of adult pig small intestinal epithelium (pig No. 1), 40 μg; and lane 6, non-acid glycosphingolipids of adult pig small intestinal epithelium (pig No. 2), 40μg.

Two different binding modes were observed for the two non-acid glycosphingolipid fractions from adult pig intestinal epithelium (Fig. 6B, lanes 4 and 6). The fraction in lane 4 (adult pig No. 1) had one binding-active compound migrating in the pentaglycosylceramide region, whereas in the fraction in lane 6 (adult pig No. 2) a distinct binding to a compound migrating in the penta-/hexaosylceramide region was observed, along with binding to a more slow migrating compound. Several compounds recognized by monoclonal antibodies directed against the blood group A determinant were present in the non-acid fraction from adult pig No. 2 (not shown). In contrast, no binding of the anti-A monoclonal antibodies to the non-acid glycosphingolipids from 3-day-old piglet, and adult pig No. 1 occurred, indicating that these fractions were from blood group O pigs, because blood group B is not expressed in pigs (29).

Isolation and Characterization of the F18-binding Glycosphingolipid from Blood Group O Pig Intestinal Epithelium

From 148 mg of total non-acid glycosphingolipids from one blood group O pig intestine, 6.0 mg of pure F18 fimbriae-binding glycosphingolipid (designated fraction O-I) was isolated by a number of chromatographic steps. It should be noted that, although all fractions obtained during the isolation procedure were tested for binding of F18-expressing E. coli, no other binding-active glycosphingolipids from this source were detected.

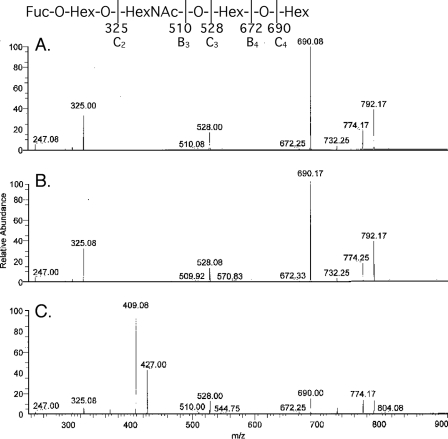

Characterization of the F18-fimbriated E. coli binding glycosphingolipid isolated from blood group O pig intestinal epithelium demonstrated a blood group H type 1 pentaglycosylceramide (Fucα2Galβ3GlcNAcβ3-Galβ4Glcβ1Cer). This conclusion was based on the following three properties: (i) The binding-active compound migrated in the pentaglycosylceramide region on thin-layer chromatograms (Fig. 6B, lane 4). (ii) In the LC/MS analysis of the saccharides obtained by hydrolysis with Rhodococcus endoglycoceramidase, the retention time and MS2 spectrum of the saccharide of the porcine pentaglycosylceramide and of reference H type 1 pentaglycosylceramide were almost identical. The saccharides were detected as an [M-H]– ion at m/z 852, and the saccharides from pig intestinal epithelium and from reference H type 1 pentaglycosylceramide both eluted at 22.5–23.3 min (data not shown), whereas the saccharide obtained from reference H type 2 pentaglycosylceramide eluted at 24.6–25.1 min. MS2 of the saccharide released from the pentaglycosylceramide from pig intestinal epithelium (Fig. 7A) and reference H type 1 pentaglycosylceramide (Fig. 7B) resulted in very similar mass spectra with a series of prominent C-type fragment ions (C2 at m/z 325, C3 at m/z 528, and C4 at m/z 690) identifying a pentasaccharide with a Fuc-Hex-HexNAc-Hex-Hex sequence. C-type fragment ions at m/z 325, m/z 528, and m/z 690, identifying a Fuc-Hex-HexNAc-Hex-Hex sequence, were also present in the MS2 spectrum of reference H type 2 pentaglycosylceramide (Fig. 7C). However, this spectrum was dominated by a 0,2A3 fragment ion at m/z 427 and a 0,2A3-H2O fragment ion at m/z 409, characteristic for GlcNAc substituted at C-4, i.e. type 2 carbohydrate chains (30, 31). (iii) The proton NMR spectrum of the F18-fimbriated E. coli binding pentaglycosylceramide of pig intestine (not shown) revealed five anomeric signals (summarized in Table 2) composed of a terminal α and four internal β resonances at 4.983 ppm (Fucα2), 4.574 ppm (GlcNAcβ3), 4.442 ppm (Galβ3), 4.262 ppm (Galβ4), and 4.207 ppm (Glcβ1), respectively, readily identifying this compound as the H type 1 pentaglycosylceramide (Fucα2Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ 1Cer) through comparison with previously published spectra (32).

FIGURE 7.

LC/MS of the saccharide obtained by digestion with Rhodococcus endoglycoceramidase II of the F18 fimbriated E. coli binding glycosphingolipid fraction O-I from blood group O pig intestinal epithelium. MS2 spectra of the [M-H]– ions at m/z 852 of the saccharides derived from the F18 fimbriae-binding glycosphingolipid from blood group O pig intestinal epithelium (fraction O-I) (A), reference H type 1 pentaglycosylceramide (B), and reference H type 2 pentaglycosylceramide (C).

TABLE 2.

Chemical shift data (ppm) for anomeric resonances from proton NMR spectra of glycosphingolipids from blood group A and O pig intestinal epithelia, obtained in DMSO-d6/D2O (98:2, by volume) at 30 °C

| IX | VIII | VII | VI | V | IV | III | II | I | Trivial name | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fucα2 | Galβ3 | GlcNAcβ3 | Galβ4 | Glcβ1 | Cer | H5 type1 | This work and Ref. 39 | ||||

| 4.983 | 4.442 | 4.574 | 4.262 | 4.207 | |||||||

| GalNAcα3 | (Fucα2) | Galβ3 | GlcNAcβ3 | Galβ4 | Glcβ1 | Cer | A6 type 1 | This work and Ref. 39 | |||

| 4.913 | 5.061 | 4.501 | 4.532 | 4.259 | 4.208 | ||||||

| GalNAcα3 | (Fucα2) | Galβ3 | GalNAcβ3 | Galα4 | Galβ4 | Glcβ1 | Cer | A7 type 4 | This work and Ref. 40 | ||

| 4.930 | 5.056 | 4.510 | 4.437 | 4.810 | 4.253 | 4.208 | |||||

| GalNAcα3 | (Fucα2) | Galβ3 | GlcNAcβ3 | Galβ3 | GlcNAcβ3 | Galβ4 | Glcβ1 | Cer | A8 type 1 | This work and Ref. 41 | |

| 4.917 | 5.066 | 4.49 | 4.53 | 4.18 | 4.78 | 4.26 | 4.21 | ||||

| GalNAcα3 | (Fucα2) | Galβ3 | GalNAcα3 | (Fucα2) | Galβ3 | GlcNAcβ3 | Galβ4 | Glcβ1 | Cer | A9 type 1 | This work |

| 4.948 | 5.055 | 4.657 | 4.932 | 5.276 | 4.469 | 4.50 | 4.26 | 4.21 | |||

| GalNAcα3 | (Fucα2) | Galβ3 | GalNAcα3 | (Fucα2) | Galβ4 | GlcNAcβ3 | Galβ4 | Glcβ1 | Cera | A9 type 3 | From Ref. 42 |

| 4.947 | 5.061 | 4.663 | 4.955 | 5.329 | 4.344 | 4.618 | 4.260 | 4.168 |

Measured at 35 °C except for the anomeric resonances stemming from the GalNAcα3 residues and the internal Fucα2, which were obtained at 55 °C (42).

Isolation and Characterization of F18-binding Glycosphingolipids from Blood Group A Pig Intestinal Epithelium

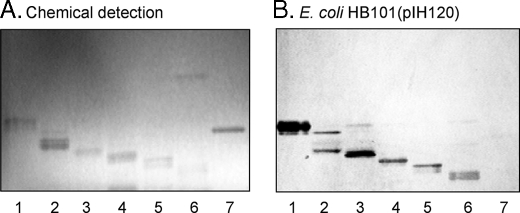

The total non-acid fraction from the intestinal epithelium of one blood group A pig was separated by silica gel chromatography and high-performance liquid chromatography, and the subfractions obtained were pooled according to mobility on thin-layer chromatograms and F18-fimbriated E. coli binding activity. Thereby, six F18-fimbriated E. coli binding fractions were obtained, designated fraction A-I (12.6 mg), A-II (3.6 mg), A-III (0.3 mg), A-IV (0.5 mg), A-V (0.2 mg), and A-VI (0.2 mg), respectively (Fig. 8). Thus, although only one glycosphingolipid with F18-fimbriated E. coli binding activity was obtained from the intestinal epithelium of the blood group O pig, the intestinal epithelium of the blood group A pig had a number of F18-fimbriated E. coli binding compounds.

FIGURE 8.

Binding of recombinant E. coli expressing F18 fimbriae (strain HB101(pIH120)) to non-acid glycosphingolipids isolated from a blood group A pig intestinal epithelium on thin-layer chromatograms. The glycosphingolipids were separated on aluminum-backed silica gel plates and visualized with anisaldehyde (A). Duplicate chromatograms were incubated with 35S-labeled bacterial cells (B), followed by autoradiography for 12 h, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The solvent system used was chloroform/methanol/water (60:35:8, by volume). The lanes are: lane 1, fraction A-I from a blood group A pig intestinal epithelium, 4 μg; lane 2, fraction A-II, 4 μg; lane 3, fraction A-III, 4 μg; lane 4, fraction A-IV, 4 μg; lane 5, fraction A-V, 4 μg; lane 6, fraction A-VI, 4 μg; and lane 7, reference A type 2 heptaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ4(Fucα3)GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer) of human erythrocytes, 4 μg.

Fraction A-I—Structural characterization of fraction A-I identified a blood group A6 type 1 hexaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer). This conclusion is based on the following three observations: (i) On thin-layer chromatograms this F18-binding glycosphingolipid migrated in the hexaglycosylceramide region (Fig. 8B, lane 1). (ii) The negative ion FAB mass spectrum of fraction A-I (supplemental Fig. S1) had a series of molecular ions at m/z 1592–1721, identifying a hexaglycosylceramide with one fucose, two HexNAc and three Hex, having a mixed ceramide composition with phytosphingosine and hydroxy 24:0 fatty acid as the predominant species. Fragment ions, derived from the molecular ion at m/z 1721, were found at m/z 1575, 1518, 1372, 1209, 1006, 844, and 682, identifying a HexNAc-(Fuc-)Hex-HexNAc-Hex-Hex sequence. (iii) Proton NMR spectroscopy (data not shown) showed six anomeric signals at 5.061 ppm (α), 4.913 ppm (α), 4.532 ppm (β), 4.501 ppm (β), 4.259 ppm (β), and 4.208 ppm (β), respectively, thus identifying the structure as the A type 1 hexaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer) (Table 2) through comparison with previously published spectra (32).

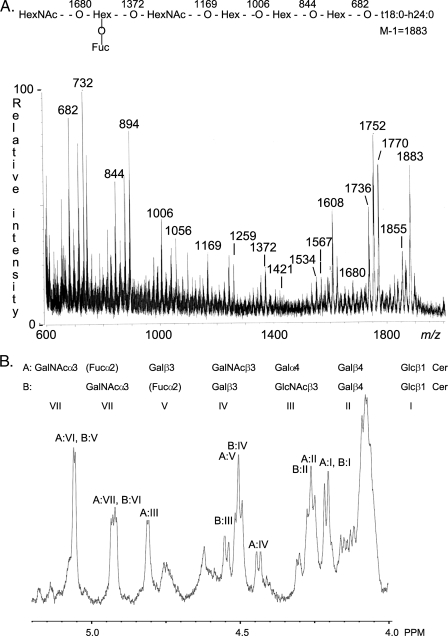

Fraction A-II—Characterization of F18-fimbriated E. coli binding fraction A-II demonstrated a heptaglycosylceramide based on a type 4 chain, i.e. a blood group A type 4 heptaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GalNAcβ3Galα4Galβ4Glcβ1Cer) as the major component. This conclusion was based on the following properties: (i) On thin-layer chromatograms the major compound of fraction A-II migrated in the heptaglycosylceramide region (Fig. 8B, lane 2). A minor compound migrating in the hexaglycosylceramide region was also observed. (ii) The negative ion FAB mass spectrum of fraction A-II (Fig. 9A) had a set of molecular ions at m/z 1736, 1752, 1770, 1855, and 1883 indicating a glycosphingolipid with one Fuc, two HexNAc, and four Hex, and d18:1–16:0, t18:0–16:0, t18:0-h16:0, t18:0-h22:0, and t18:0-h24:0 ceramides, respectively.6 A series of fragment ions, obtained by sequential loss of terminal carbohydrate units from the ion at m/z 1883, were observed at m/z 1680, 1534, 1372, 1169, 1006, 844, and 682, demonstrating a HexNAc-(Fuc-)Hex-HexNAc-Hex-Hex-Hex sequence. Other series of fragment ions supported this proposed carbohydrate sequence, e.g. the ions derived from the molecular ion at m/z 1770, found at m/z 1567, 1421, 1259, 1056, 894, 732, and 570 (not shown). (iii) The anomeric region of the proton NMR spectrum of fraction A-II shown in Fig. 9B revealed the presence of two major compounds (∼1:1) of which the first is A6 type 1 glycosphingolipid, as described for the previous fraction. The second compound exhibits seven anomeric signals as follows: 5.056 ppm (α), 4.930 ppm (α), 4.810 ppm (α), 4.510 ppm (β), 4.437 ppm (β), 4.253 ppm (β), and 4.208 ppm (β). This set of signals (Table 2) readily identifies the compound as the A7 type 4 glycosphingolipid (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Gal β3GalNAcβ3Galα4Galβ4Glcβ1Cer) previously isolated from blood group A1 erythrocytes (33).

FIGURE 9.

Characterization of the F18-fimbriated E. coli binding heptaglycosylceramide isolated from blood group A pig intestinal epithelium (fraction A-II) by mass spectrometry and proton NMR. A, negative ion FAB mass spectrum of fraction A-II. Above the spectrum is an interpretation formula representing the molecular species with t18:0-h24:0 ceramide. The analysis was done as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, anomeric region of the 600-MHz proton NMR spectrum of fraction A-II (30 °C). The sample was dissolved in DMSO-D2O (98:2, by volume) after deuterium exchange.

A comparison of the binding of F18-expressing E. coli bacteria to the A type 1 hexaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer) and the A type 4 heptaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GalNAcβ3Galα4 Galβ4Glcβ1Cer) is shown in Fig. 5C. Again, the detection limit for the A type 1 hexaglycosylceramide was ∼0.08 μg, whereas the detection limit for the A type 4 heptaglycosylceramide was ∼0.8 μg.

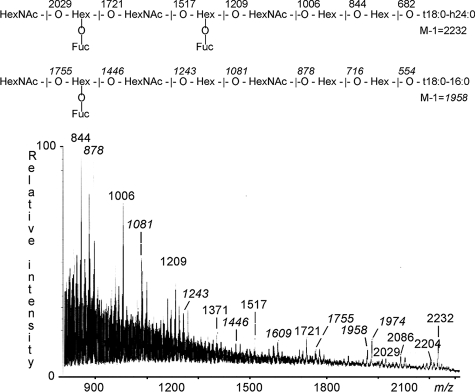

Fraction A-III—Structural characterization of F18-fimbriated E. coli binding fraction A-III identified showed that it contained a linear blood group A type 1 octaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer) and a repetitive A type 1 nonaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)GalβGalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer). This was concluded from the following three observations: (i) Fraction A-III migrated below the heptaglycosylceramide region on thin-layer chromatograms (Fig. 8B, lane 3). (ii) In the negative ion FAB mass spectrum of fraction A-III (Fig. 10) two sets of molecular ions were observed. The molecular ions at m/z 2204 and 2232 corresponded to a nonaglycosylceramide with two fucoses, three HexNAc, and four hexoses, combined with t18:0-h22:0 and t18:0-h24:0 ceramides, respectively. Fragments ions from the molecular ion at m/z 2232, observed at m/z 2086, 2029, 1721, 1517, 1371, 1209, 1006, 844, and 682 (not shown) identified a HexNAc-(Fuc-)Hex-HexNAc-(Fuc-)Hex-HexNAc-Hex-Hex sequence. The second series of molecular ions at m/z 1958 and 1974 identified an octaglycosylceramide with one fucose, three HexNAc, and four hexoses, and with t18:0–16:0 and t18:0-h16:0 ceramides, respectively. Fragments ions derived from the molecular ion at m/z 1958, found at m/z 1755, 1609, 1446, 1243, 1081, 878, 716 (not shown), and 554 (not shown), demonstrated a HexNAc-(Fuc-)Hex-HexNAc-Hex-HexNAc-Hex-Hex carbohydrate sequence. (iii) The anomeric region of the proton NMR spectrum of fraction A-III (not shown) is complex, consisting of at least four species of which two are dominating. One of the minor contributions is due to the A7 type 4 glycosphingolipid, as described above, whereas the two dominating compounds can be ascribed to the A8 type 1 (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ3GlcNAcβGalβ4Glcβ1Cer) and A9 type 1 (GalNAcα3(Fucα2) Galβ3GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer) glycosphingolipids, of which the former previously has been isolated from rat small intestine (34). The A8 type 1 structure thus displays the following anomeric signals (Table 2): 5.066 ppm (Fucα2), 4.917 ppm (GalNAcα3), 4.783 ppm (core GlcNAcβ3), 4.53 ppm (GlcNAcβ3), 4.49 ppm (Galβ3), 4.26 ppm (Galβ4), 4.209 ppm (Glcβ1), and 4.195 ppm (core Galβ3). The latter compound (A9 type 1 glycosphingolipid) has not been described earlier. The same compound has also been isolated from the small intestine of miniature swine and characterized by NMR.7 The A9 type 1 glycosphingolipid differs from the A9 type 3 structure (35) only in that the core Gal at position 4 is 3-linked instead of 4-linked. However, this affects the anomeric region of the NMR spectrum significantly as regards the internal blood group A determinant, as summarized in Table 2. The following anomeric signals could thus be established for the A9 type 1 structure: external GalNAcα3 at 4.948 ppm, external Fucα2 at 5.055 ppm, external Galβ3 at 4.657 ppm, internal GalNAcα3 at 4.932 ppm, internal Fucα2 at 5.276 ppm, internal Galβ3 at 4.469 ppm, core GlcNAcβ3 at 4.50 ppm, core Galβ4 at 4.26 ppm, and core Glcβ1 at 4.21 ppm. A comparison with the A9 type 3 structure thus reveals that the sugar residues of the inner A determinant have shifted significantly as exemplified by the upfield shifts of the internal GalNAcα3 and Fucα2 by 0.03 ppm and 0.05 ppm, respectively. However, even more conspicuous is the absence of the core Galβ4 resonance at 4.344 ppm in A9 type 3 glycosphingolipid, which in A9 type 1 glycosphingolipid has been replaced by a core Galβ3 at 4.469 ppm.

FIGURE 10.

Negative ion FAB mass spectrum of the F18-fimbriated E. coli binding glycosphingolipid fraction A-III, isolated from blood group A pig intestinal epithelium. Above the spectrum are interpretation formulae representing an octaglycosylceramide with t18:0–16:0 ceramide and a nonaglycosylceramide with t18:0-h24:0 ceramide, respectively. The analysis was done as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

Fractions A-IV–VI—F18-fimbriated E. coli binding fractions A-IV-VI migrated below the octaglycosylceramide region on thin-layer chromatograms (Fig. 8B, lanes 4–6). The negative ion FAB mass spectra of these fractions were very complex. The spectrum of fraction A-IV (supplemental Fig. S2) had two molecular ions at m/z 2407 and 2435, indicating a decaglycosylceramide with two fucoses, four HexNAc, and four hexoses, with t18:0-h22:0 and t18:0-h24:0 ceramides, respectively. Fragments ions from the molecular ion at m/z 2435 were observed at m/z 2232, 1924, and 1721, identifying a terminal HexNAc-(Fuc-)Hex-HexNAc sequence.

Negative ion FAB mass spectrometry of fraction A-V (supplemental Fig. S3) demonstrated molecular ions at m/z 2553 and 2581, corresponding to an undecaglycosylceramide with three fucoses, four HexNAc, and four hexoses, with t18:0-h22:0 and t18: 0-h24:0 ceramides, respectively. A terminal HexNAc-(Fuc-)Hex-HexNAc sequence was suggested by fragment ions from the molecular ion at m/z 2581, found at m/z 2378, 2070, and 1867.

The major compound of fraction A-VI gave rise to molecular ions at m/z 2772 and 2800 (supplemental Fig. S4), which tentatively identified it as a glycosphingolipid with twelve carbohydrate units (two fucoses, five HexNAc, and five Hex), combined with t18:0-h22:0 and t18:0-h24:0 ceramides, respectively. Fragments ions from the molecular ion at m/z 2800, observed at m/z 2597, 2289, and 2086, again identified a terminal HexNAc-(Fuc-)Hex-HexNAc sequence.

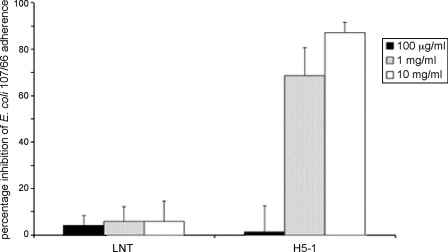

Carbohydrate Inhibition Assay

The ability of soluble oligosaccharides to interfere with the binding of F18-fimbriated E. coli to porcine small intestinal cells was evaluated in the in vitro villous adhesion assay. A strong reduction (87.1%, S.D. = 4.5 and 68.5%, S.D. = 12.2) of the adherence of F18-positive E. coli to porcine intestinal villi of two different pigs was obtained by incubation of the bacteria with 10 mg/ml and 1 mg/ml of the blood group H type 1 pentasaccharide (H5-1, Fucα2Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glc) (Fig. 11), whereas incubation with 100 μg/ml of the H5–1 saccharide had no visible effect (1.4% inhibition, S.D. = 11.14) on the adherence of the bacteria. Incubation with different concentrations (10 mg/ml, 1 mg/ml, and 100 μg/ml) of lacto-N-tetraose saccharide (Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glc) had no effect (5.8% inhibition, S.D. = 8.9; 5.8% inhibition, S.D. = 6.4; and 4.2% inhibition, S.D. = 4.2, respectively) on the adherence of the F18-fimbriated E. coli.

FIGURE 11.

Effect of preincubation of F18-fimbriated E. coli with oligosaccharides. F18-positive E. coli strain 107/86 was incubated with blood group H type 1 pentasaccharide (H5–1, Fucα2Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glc) or lacto-N-tetraose saccharide (Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glc) in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Thereafter, the suspensions were utilized in the in vitro villous adhesion assay.

DISCUSSION

Attachment of pathogenic bacteria to host tissues is a critical early step in the development of disease. The F18-fimbriated E. coli, causing post-weaning diarrhea and edema disease in pigs, adhere to a specific receptor on the epithelial cells of the porcine small intestine, but the nature of this F18R has so far remained unknown. In this study, F18R was identified by binding of F18-expressing E. coli to glycosphingolipids, demonstrating a highly specific interaction of the F18-fimbriated bacteria with glycosphingolipids having blood group ABH determinants on type 1 core chains, as well as the blood group A type 4 heptaglycosylceramide. The absence of binding of the FedF deletion mutant strain to the blood group antigen-carrying glycosphingolipids recognized by the F18-fimbriated E. coli strain, demonstrated that the recognition of the blood group ABH determinants is mediated by the FedF adhesin.

Comparison of the relative binding affinities of the F18-fimbriated E. coli for binding-active glycosphingolipids demonstrated that the minimal binding epitope of the FedF adhesin is the linear Fucα2Galβ3GlcNAc sequence (blood group H type 1 determinant), whereas an optimal binding epitope is created by the addition of the α3-linked galactose or N-acetylgalactosamine of the Galα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAc (blood group B type 1 determinant) and GalNAcα3(Fucα2)-Galβ3GlcNAc (blood group A type 1 determinant) sequences.

However, investigation of glycosphingolipids recognized by F18-fimbriated bacteria in the target cells of porcine small intestinal epithelium revealed that these bacteria also have the capacity to interact with the blood group A type 4 heptaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GalNAcβ3Galα4Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), although with a lower affinity of binding than for the blood group A type 1 hexaglycosylceramide.

In pigs only blood group A and O determinants are expressed (29). Thus, the binding of blood group B type 1 determinants by the F18-fimbriated E. coli has no relevance for attachment to pig intestine. However, binding to blood group B determinant on type 1 core chains is not surprising from a structural point of view, because the accommodation of a GalNAcα3 into the binding site of FedF will also allow accommodation of a Galα3. To address the relevance of the blood group antigen binding for target tissue adherence, F18-fimbriated E. coli binding glycosphingolipids were isolated from epithelial cells of the small intestine of blood group O and A pigs and characterized by mass spectrometry and proton NMR.

The only glycosphingolipid with F18-fimbriated E. coli binding activity obtained from the intestinal epithelium of the blood group O pig was a blood group H type 1 pentaglycosylceramide (Fucα2Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer). In contrast, the intestinal epithelium of the blood group A pig had a number of F18-fimbriated E. coli binding glycosphingolipids. The major compound was characterized as a blood group A type 1 hexaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer), as reported previously (36). The heptaglycosylceramide was found to be based on a type 4 chain, i.e. an A type 4 heptaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GalNAcβ3Galα4Galβ4Glcβ1Cer). This glycosphingolipid has previously only been identified in human kidney and erythrocytes (33, 37).

Structural characterization of F18-binding glycosphingolipids of the intestinal epithelium of the blood group A pig also identified a linear A type 1 octaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ3GlcNAcβGalβ4Glcβ1Cer) (34), and a novel repetitive A type 1 nonaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer). The discovery of the latter compound is consistent with the dominance of type 1-based structures in the intestinal epithelium as opposed to the type 2-based core in the A9 type 3 nonaglycosylceramide found in A erythrocytes (35). The more slow migrating binding-active compounds were tentatively identified as a decaglycosylceramide, an undecaglycosylceramide, and a glycosphingolipid with twelve carbohydrate units, all having a terminal HexNAc-(Fuc-)Hex-HexNAc sequence.

Comparison of the minimum energy conformations of the A types 1 and 2 hexaglycosylceramides, the A type 4 heptaglycosylceramide, and the A type 3 nonaglycosylceramide (38) show that the conformation of the terminal A-trisaccharide per se is practically the same in all four types of oligosaccharide chains. However, the orientation of the oligosaccharide chains differ, and whereas the A determinant of the A type 1 hexaglycosylceramide extends almost perpendicular to the membrane plane, the terminal part of the carbohydrate chains of the types 2–4 are more parallel to the membrane. A noteworthy observation is that the α2-linked fucose residue of the A determinant (required for F18 binding) of the type 2 chain is facing the membrane, and thus relatively inaccessible, whereas in the type 1, 3, and 4 chains the α2-linked fucose is directed toward the environment. Furthermore, the blood group A9 type 1-based repetitive nonaglycosylceramide discovered in this work is expected to have the same conformation as A6 type 1 as regards the core structure, thus exposing Fucα2 of the external A determinant.

Unfortunately, the A type 3 nonaglycosylceramide (GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ3GalNAcα3(Fucα2)Galβ4GlcNAcβ3Galβ4Glcβ1Cer) was not available for testing. This glycosphingolipid is present, however, as a minor compound in the non-acid fraction of human blood group A erythrocytes (35), and no binding of F18-fimbriated E. coli to this fraction occurred. Thus, the A type 3 nonaglycosylceramide might be non-binding, but the absence of binding might also be due to the low concentration of this glycosphingolipid.

Inhibition of binding of F18-fimbriated E. coli to porcine enterocytes by monoclonal antibodies directed against the blood group H type 2 epitope (Fucα2Galβ4GlcNAcβ) has been described, leading to the suggestion that target cell adherence of these bacteria is mediated by binding to type 2 carbohydrate chains (39). In the present study, glycosphingolipids with type 2 chains were not recognized by the F18-fimbriated E. coli, and we found no blood group H type 2-carrying glycosphingolipids in the intestinal epithelium of the blood group O pig. However, lectin and monoclonal antibody binding studies have demonstrated the presence of the H type 2 epitope in porcine small intestinal glycoproteins (40). Glycoprotein binding by the anti-H type 2 monoclonal antibodies used in the previous study might have imposed a sterical hindrance, obscuring the high affinity binding to type 1- and type 4-based glycosphingolipids.

The synthesis of histo-blood group antigens requires several glycosyltransferases acting on precursor oligosaccharides, such as type 1 (Galβ3GlcNAcβ-R) and type 2 precursor chains (Galβ4GlcNAcβ-R). These precursors are converted into H antigens by the action of α2-fucosyltransferases adding a fucose in an α2-linkage. Two genes encoding fucosyltransferases, FUT1 and FUT2, have been identified in pigs, corresponding to the human H (FUT1) and Se (FUT2) genes, respectively (14).

Because resistance to infections with F18-fimbriated E. coli is associated with polymorphism on bp 307 of FUT1 (15), the highly specific binding of F18-fimbriated E. coli to blood group ABH determinants on type 1 core chains was an unexpected finding. However, although it had been demonstrated that human and porcine FUT1 enzymes preferentially act on type 2 chain precursor chains in vitro (41, 42), α2-fucosylation of type 1 chains by human FUT1 also occurs both in vitro and in vivo (43–45), suggesting that porcine FUT1 enzyme may also act on type 1 precursor chains. If porcine FUT1 enzyme is directly involved in the synthesis of type 1 blood group ABH determinants in porcine intestine merits further investigations.

Several other bacteria, including Helicobacter pylori and Campylobacter jejuni, have also been shown to utilize blood group determinants as receptors to facilitate their colonization. While C. jejuni binds to the blood group H type 2 determinant (46), the primary receptor for H. pylori is the Leb determinant (Fucα2Galβ3-(Fucα4)GlcNAc), along with a lower affinity binding to the H type 1 determinant (47). Binding to Leb and the H type 1 determinant is mediated by the BabA adhesin (48). Recently the adaptation of the BabA adhesin to the fucosylated blood group antigens most prevalent in the local population was described (49). In Europe and the U.S., where the blood group ABO phenotypes are common in the population, the H. pylori strains (designated generalist strains) bind to blood group A, B, and O type 1 determinants. However, in populations such as the indigenous South American native population, which only have the blood group O phenotype, the H. pylori strains (designated specialist strains) bind only to the blood group O determinants (Leb and the H type 1). Thus, both the BabA adhesin of H. pylori generalist strains, and the FedF protein of F18-fimbriated E. coli, have the capacity to bind to the blood group ABH type 1 determinants, whereas the main receptor for the BabA adhesin, i.e. the Leb determinant, is not recognized by the FedF protein. A structural comparison of the BabA adhesin and the FedF protein would thus be highly interesting.

Several other fimbriated E. coli interact with glycosphingolipids to colonize the host epithelium. P-fimbriated uropathogenic E. coli bind to the Galα4Gal sequence present in the globoseries glycosphingolipids on kidney epithelium and kidney vascular endothelium (50, 51). In addition, F5 (K99)-fimbriated E. coli, causing neonatal diarrhea in pigs and calves, recognize NeuGcα3-carrying glycosphingolipids on porcine and bovine intestinal epithelium (20, 52, 53). Glycosphingolipid binding of E. coli with F1C-fimbriae, CFA/I-fimbriae, S-fimbriae, and F4ad (K88ad) fimbriae has also been reported (54–57).

Susceptibility to infections caused by F18-fimbriated E. coli is dependent on the age of the pigs (58, 59). No adhesion of F18-positive bacteria to the intestinal epithelium of newborn pigs occurs, whereas from the age of 3 weeks strong adhesion to the intestinal epithelium is observed, and no decline in adhesion is found as the pigs grow older. The F18-binding glycosphingolipids are present in both young (3 days old) and adult pigs. However, an important difference in the quantities of non-acid glycosphingolipids of intestinal mucosa exists in newborn and adult pigs (20). The amount of acid glycosphingolipids in intestinal mucosa of newborn pigs is about ten times higher than in adult pigs, and is about seven times higher than the amount of the non-acid glycosphingolipids. This high amount of non-binding acid glycosphingolipids could mask the F18-binding glycosphingolipids in young pigs (<3 weeks old), or could inhibit adhesion by sterical hindrance, thereby causing resistance to infection.

The knowledge of the F18R carbohydrate structure opens new perspectives to develop anti-adhesive therapies against pig post-weaning diarrhea and edema disease. Carbohydrate receptor mimics or receptor blocking agents such as lectins or antibodies supplemented in pig feed could interfere with the initial attachment of the bacteria to the pig intestinal epithelium and prevent pigs from infection. In the past, several carbohydrate receptor analogs were shown to inhibit adhesion of various pathogens to host epithelium (60), but clinical trials in man revealed poor efficacy (61, 62). In the present study we show that the binding of F18-fimbriated E. coli to porcine small intestinal cells was decreased, in a dose-dependent manner, by incubation of the bacteria with the blood group H type 1 pentasaccharide. Synthesis of multivalent inhibitors could be a way to improve the efficacy of these carbohydrate receptor analogs (63, 64). Furthermore, co-crystallization of the identified carbohydrate receptor with the adhesin FedF will increase our understanding of the combining site, which could facilitate the design of more potent anti-adhesive molecules.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Furthermore, Dr. Imberechts is thanked for providing E. coli strains HB101(pIH120) and HB101(pIH126). The use of the Varian 600 MHz machine at the Swedish NMR Centre, Hasselblad Laboratory, Göteborg University, is gratefully acknowledged.

This work was supported in part by the Swedish Research Council/Medicine (Grant 11612 to S. T. and Grant 12628 to M. E. B.), the Swedish Cancer Foundation (to S. T.), and Magnus Bergvalls Foundation (to S. T.). The UGent and FWO-Flanders (Grants G001305N and 3G038907) are acknowledged for their financial support.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: ETEC, enterotoxigenic E. coli; F18R, receptor for F18-fimbriated E. coli; FAB, fast atom bombardment; LC/MS, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; BSA, bovine serum albumin; MS, mass spectrometry; MS2, tandem mass spectrometry.

The glycosphingolipid nomenclature follows the recommendations by the IUPAC-IUB Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (CBN for Lipids (65)). It is assumed that Gal, Glc, GlcNAc, GalNAc, NeuAc, and NeuGc are of the D-configuration, Fuc of the L-configuration, and all sugars are present in the pyranose form.

In the shorthand nomenclature for fatty acids and bases, the number before the colon refers to the carbon chain length and the number after the colon gives the total number of double bonds in the molecule. Fatty acids with a 2-hydroxy group are denoted by the prefix h before the abbreviation; e.g. h16:0. For long-chain bases, d denotes dihydroxy and t trihydroxy. Thus d18:1 designates sphingosine (1,3-dihydroxy-2-aminooctadecene) and t18:0 phytosphingosine (1,3,4-trihydroxy-2-aminooctadecane).

J. Ångström, manuscript in preparation.

References

- 1.Kaper, J. B., Nataro, J. P., and Mobley, H. L. (2004) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2 123–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fairbrother, J. M., Nadeau, E., and Gyles, C. L. (2005) Anim. Health Res. Rev. 6 17–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertschinger, H., and Gyles, C. L. (1994) in Escherichia coli in Domestic Animals and Humans (Gyles, C. L. ed) pp. 193–219, CAB, Wallingford, Oxon, UK

- 4.Imberechts, H., De Greve, H., Schlicker, C., Bouchet, H., Pohl, P., Charlier, G., Bertschinger, H., Wild, P., Vandekerckhove, J., Van Damme, J., Van Montagu, M., and Lintermans, P. (1992) Infect. Immun. 60 1963–1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imberechts, H., Wild, P., Charlier, G., De Greve, H., Lintermans, P., and Pohl, P. (1996) Microb. Pathog. 21 183–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smeds, A., Hemmann, K., Jakava-Viljanen, M., Pelkonen, S., Imberechts, H., and Palva, A. (2001) Infect. Immun. 69 7941–7945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hultgren, S. J., Lindberg, F., Magnusson, G., Kihlberg, J., Tennent, J. M., and Normark, S. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86 4357–4361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choudhury, D., Thompson, A., Stojanoff, V., Langermann, S., Pinkner, J., Hultgren, S. J., and Knight, S. D. (1999) Science 285 1061–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sauer, F. G., Fütterer, K., Pinkner, J. S., Dodson, K. W., Hultgren, S. J., and Waksman, G. (1999) Science 285 1058–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buts, L., Bouckaert, J., De Genst, E., Loris, R., Oscarson, S., Lahmann, M., Messens, J., Brosens, E., Wyns, L., and De Greve, H. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 49 705–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Kerpel, M., Van Molle, I., Brys, L., Wyns, L., De Greve, H., and Bouckaert, J. (2006) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 62 1278–1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertschinger, H. U., Stamm, M., and Vögeli, P. (1993) Vet. Microbiol. 35 79–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vögeli, P., Bertschinger, H. U., Stamm, M., Stricker, C., Hagger, C., Fries, R., Rapacz, J., and Stranzinger, G. (1996) Anim. Genet. 27 321–328 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meijerink, E., Fries, R., Vögeli, P., Masabanda, J., Wigger, G., Stricker, C., Neuenschwander, S., Bertschinger, H. U., and Stranzinger, G. (1997) Mamm. Genome 8 736–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meijerink, E., Neuenschwander, S., Fries, R., Dinter, A., Bertschinger, H. U., Stranzinger, G., and Vögeli, P. (2000) Immunogenetics 52 129–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wellens, A., Garofalo, C., Nguyen, H., Van Gerven, N., Slättegård, R., Hernalsteens, J. P., Wyns, L., Oscarson, S., De Greve, H., Hultgren, S., and Bouckaert, J. (2008) PLoS ONE 3 e2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bertschinger, H. U., Bachmann, M., Mettler, C., Pospischil, A., Schraner, E. M., Stamm, M., Sydler, T., and Wild, P. (1990) Vet. Microbiol. 25 267–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox, E., and Houvenaghel, A. (1993) Vet. Microbiol. 34 7–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verdonck, F., Cox, E., van Gog, K., Van der Stede, Y., Duchateau, L., Deprez, P., and Goddeeris, B. M. (2002) Vaccine 20 2995–3004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teneberg, S., Willemsen, P., de Graaf, F. K., Stenhagen, G., Pimlott, W., Jovall, P.-Å., Ångström, J., and Karlsson, K.-A. (1994) J. Biochem. 116 560–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waldi, D. (1962) in Dünnschicht-Chromatographie (Stahl, E., ed) pp. 496–515, Springer-Verlag, Berlin

- 22.Hansson, G. C., Karlsson, K-A., Larson, G., McKibbin, J. M., Blaszczyk, M., Herlyn, M., Steplewski, Z., and Koprowski, H. (1983) J. Biol. Chem. 258 4091–4097 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ito, M., and Yamagata, T. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264 9510–9519 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erickson, A. K., Baker, D. R., Bosworth, B. T., Casey, T. A., Benfield, D. A., and Francis, D. H. (1994) Infect. Immun. 62 5404–5410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breimer, M. E., Hansson, G. C., Karlsson, K.-A., and Leffler, H. (1981) J. Biol. Chem. 257 557–568 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koscielak, J., Plasek, A., Górniak, H., Gardas, A., and Gregor, A. (1973) Eur. J. Biochem. 37 214–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stellner, K., Watanabe, K., and Hakomori, S.-i. (1973) Biochemistry 12 656–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clausen, H., Levery, S. B., Nudelman, E., Baldwin, M., and Hakomori, S.-i. (1986) Biochemistry 25 7075–7085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sako, F., Gasa, S., Makita, A., Hayashi, A., and Nozawa, S. (1990) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 278 228–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chai, W., Piskarev, V., and Lawson, A. M. (2001) Anal. Chem. 73 651–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robbe, C., Capon, C., Coddeville, B., and Michalski, J.-C. (2004) Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 18 412–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clausen, H., Levery, S. B., McKibbin, J. M., and Hakomori, S.-i. (1985) Biochemistry 24 3578–3586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clausen, H., Watanabe, K., Kannagi, R., Levery, S. B., Nudelman, E., Arao-Tomono, Y., and Hakomori, S.-i. (1984) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 124 523–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouhours, D., Ångström, J., Jovall, P.-Å., Hansson, G. C., and Bouhours, J.-F. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266 18613–18619 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clausen, H., Levery, S. B., Nudelman, E. D., Tsuchiya, S., and Hakomori, S.-i. (1985) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 82 1199–1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bäcker, A. E., Breimer, M. E., Samuelsson, B. E., and Holgersson, J. (1997) Glycobiology 7 943–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holgersson, J., Clausen, H., Hakomori, S.-i., Samuelsson, B. E., and Breimer, M. E. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265 20790–20798 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nyholm, P. G., Samuelsson, B. E., Breimer, M., and Pascher, I. (1989) J. Mol. Recogn. 3 103–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snoeck, V., Verdonck, F., Cox, E., and Goddeeris, B. M. (2004) Vet. Microbiol. 100 241–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.King, T. P., Begbie, R., Slater, D., McFadyen, M., Thom, A., and Kelly, D. (1995) Glycobiology 5 525–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oriol, R., Le Pendu, J., and Mollicone, R. (1986) Vox Sang. 51 161–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohney, S., Mouhtouris, E., McKenzie, I. F., and Sandrin, M. S. (1999) Int. J. Mol. Med. 3 199–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu, Y. H., Fujitani, N., Koda, Y., and Kimura, H. (1998) J. Histochem. Cytochem. 46 69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mathieu, S., Prorok, M., Benoliel, A. M., Uch, R., Langlet, C., Bongrand, P., Gerolami, R., and El-Battari, A. (2004) Am. J. Pathol. 164 371–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kyprianou, P., Betteridge, A., Donald, A. S. R., and Watkins, W. M. (1990) Glycoconj. J. 7 573–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruiz-Palacios, G. M., Cervantes, L. E., Ramos, P., Chavez-Munguia, B., and Newburg, D S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 14112–14120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borén, T., Falk, P., Roth, K. A., Larson, G., and Normark, S. (1993) Science 262 1892–1895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ilver, D., Arnqvist, A.,Ögren, J., Frick, I. M., Kersulyte, D., Incecik, E. T., Berg, D. E., Covacci, A., Engstrand, L., and Borén, T. (1998) Science 279 373–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aspholm-Hurtig, M., Dailide, G., Lahmann, M., Kalia, A., Ilver, D., Roche, N., Vikström, S., Sjöström, R., Lindén, S., Bäckström, A., Arnqvist, A., Mahdavi, J., Nilsson, U. J., Velapatiño, B., Gilman, R. H., Gerhard, M., Alarcon, T., López-Brea, M., Nakazawa, T., Fox, J. G., Correa, P., Dominguez-Bello, M. G., Perez-Perez, G. I., Blaser, M. J., Normark, S., Carlstedt, I., Oscarson, S., Teneberg, S., Berg, D. E., and Borén, T. (2004) Science 305 519–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leffler, H., and Svanborg-Edén, C. (1981) Infect. Immun. 34 920–929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bock, K., Breimer, M. E., Brignole, A., Hansson, G. C., Karlsson, K.-A., Larson, G., Leffler, H., Samuelsson, B. E., Strömberg, N., Svanborg Edén, C., and Thurin, J. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260 8545–8551 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kyogashima, M., Ginsburg, V., and Krivan, H. C. (1989) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 270 391–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Teneberg, S., Willemsen, P., de Graaf, F. K., and Karlsson, K.-A. (1990) FEBS Lett. 263 10–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bäckhed, F., Ahlsén, B., Roche, N., Ångström, J., von Euler, A., Breimer, M. E., Westerlund-Wikström, B., Teneberg, S., and Richter-Dahlfors, A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 18198–18205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jansson, L., Tobias, J., Lebens, M., Svennerholm, A.-M., and Teneberg, S. (2006) Infect. Immun. 74 3488–3497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prasadarao, N. V., Wass, C. A., Hacker, J., Jann, K., and Kim, K. S. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268 10356–10363 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grange, P. A., Ericksson, A. K., Levery, S. B., and Francis, D. H. (1999) Infect. Immun. 67 165–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nagy, B., Casey, T. A., Whipp, S. C., and Moon, H. W. (1992) Infect. Immun. 60 1285–1294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coddens, A., Verdonck, F., Tiels, P., Rasschaert, K., Goddeeris, B. M., and Cox, E. (2007) Vet. Microbiol. 122 332–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sharon, N. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1760 527–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ukkonen, P., Varis, K., Jernfors, M., Herva, E., Jokinen, J., Ruokokoski, E., Zopf, D., and Kilpi, T. (2000) Lancet 356 1398–1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parente, F., Cucino, C., Anderloni, A., Grandinetti, G., and Bianchi Porro, G. (2003) Helicobacter 8 252–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Simon, P. M., Goode, P. L., Mobasseri, A., and Zopf, D. (1997) Infect. Immun. 65 750–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lindhorst, T. K., Kieburg, C., and Krallmann-Wenzel, U. (1998) Glycoconj. J. 15 605–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chester, M. A. (1998) Eur. J. Biochem. 257 293–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data