Abstract

AIM: To assess the adoption of Carbon dioxide (CO2) insufflation by endoscopists from various European countries, and its determinants.

METHODS: A survey was distributed to 580 endoscopists attending a live course on digestive endoscopy.

RESULTS: The response rate was 24.5%. Fewer than half the respondents (66/142, 46.5%) were aware of the fact that room air can be replaced by CO2 for gut distension during endoscopy, and 4.2% of respondents were actually using CO2 as the insufflation agent. Endoscopists aware of the possibility of CO2 insufflation mentioned technical difficulties in implementing the system and the absence of significant advantages of CO2 in comparison with room air as barriers to adoption in daily practice (84% and 49% of answers, respectively; two answers were permitted for this item).

CONCLUSION: Based on this survey, adoption of CO2 insufflation during endoscopy seems to remain relatively exceptional. A majority of endoscopists were not aware of this possibility, while others were not aware of recent technical developments that facilitate CO2 implementation in an endoscopy suite.

Keywords: Colonoscopy, Practice survey, Carbon dioxide, Digestive endoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Use of Carbon dioxide (CO2) as the insufflating gas during colonoscopy was proposed in 1974 to decrease the explosion hazard associated with polypectomy[1]. As it appeared that there was less bloating and likely less pain after procedures using CO2 for gut distension compared to air[2], randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were performed to compare post-procedure pain when using CO2 versus room air as the insufflation agent. The results of all of these RCTs were unambiguous, with significantly less pain reported after CO2 colonoscopy[3–7]. For other endoscopic procedures also, CO2 was found to be superior to air: (1) for double balloon enteroscopy, small bowel intubation is deeper[8]; (2) for endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP), post-procedural pain is less[9,10]; and (3) for complex colorectal procedures (endoscopic submucosal dissection), fewer sedative drugs are required[11]. This is explained by the pathophysiology of gases: intestinal gases leave the body through alimentary orifices and exhaled air (gases can diffuse through the gut into splanchnic blood and subsequently pulmonary circulation). Experimental studies in live animals have shown that the clearance of gas from isolated bowel segments is much faster for CO2 than nitrogen or oxygen (the two main components of air), and this by a factor of 160 and 12, respectively[12]. The most important reason for this is the higher solubility of CO2 compared to other gases in water. Other factors that influence the diffusion of gases through the intestinal barrier are less significant (e.g. gas tension gradient between the intestinal lumen and blood) or identical for all digestive gases (e.g. surface and thickness of the exchange membrane, and tissue perfusion)[13].

Despite the high level of evidence supporting the use of CO2 for gut distension during colonoscopy and other endoscopic procedures, this gas does not seem to be used in many endoscopy practices. We here report a survey that was performed in a large group of endoscopists to assess the use of CO2 insufflation in daily endoscopy practice, including reasons for possible non-adoption.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Survey design and administration

A questionnaire was developed by the authors for the study. Content validity of the survey was determined based on input by experts in the field and a review of the relevant literature. The final, two-page, 26-item, survey contained two parts: the first one addressed respondents’ demographic characteristics and knowledge about the use of CO2 as room air replacement during gastrointestinal endoscopy; and the second part was divided in two sections directed to endoscopists who, either did (“practitioners”), or did not (“non-practitioners”) use CO2. Non-practitioners were asked for which reasons they did not use CO2, while practitioners were asked about their actual use of CO2.

The survey was performed during the 26th European Workshop on Gastroenterology and Endotherapy held in Brussels, Belgium, on 16-18 June 2008. Questionnaires were placed in cases distributed to course participants, and attendees were asked to deposit completed surveys in a dedicated box at the registration desk. Consent to participate in this study was inferred from voluntary completion of the survey. Efforts to increase response rates included two rehearsals by the course director (Deviere J), projection of a reminder slide during breaks, and collection of surveys by staff members who passed between rows of participants or were posted at the exits of the projection rooms. No gift or financial incentive was proposed to attendees.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SD or as a percentage. Each response was included in the analysis, regardless of the completeness of the survey. In cases when not all survey respondents answered to an individual question, the number of respondents (i.e. the denominator for percentage calculations) is indicated.

RESULTS

Study population

Surveys were distributed to 580 medical doctors attending the course, and 142 of them completed the study (response rate, 24.5%). All of them answered all the demographic questions (Table 1). The respondents had their endoscopy practice in 21 countries, but six of these (Belgium, Greece, Italy, France, Spain and Switzerland) made up two-thirds of the respondents. Main practices were roughly equally distributed between private practice, community hospitals and university hospitals. Sedation with propofol or general anesthesia was used for more than 50% of colonoscopies by about half the respondents.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the 142 survey respondents (mean ± SD)

| Characteristics | n (%) |

| Male gender | 109 (76.8) |

| Age (yr) | 47.7 ± 9.1 |

| Years in practice | 17.5 ± 9.2 |

| Country | |

| Belgium | 25 (17.6) |

| Greece | 18 (12.7) |

| Italy | 18 (12.7) |

| France | 16 (11.3) |

| Spain | 10 (7.0) |

| Switzerland | 9 (6.3) |

| Other | 46 (32.4) |

| Main practice setting | |

| Private | 36 (25.4) |

| Community Hospital | 54 (38.0) |

| University Hospital | 52 (36.6) |

| No. of colonoscopies performed/year in the center | |

| < 500 | 7 (4.9) |

| 500-1000 | 40 (28.2) |

| 1000-1500 | 33 (23.2) |

| > 1500 | 62 (43.7) |

| Proportion of colonoscopies performed with propofol/general anesthesia | |

| < 20% | 74 (52.1) |

| 20%-39% | 4 (2.8) |

| 40%-59% | 0 |

| 60%-79% | 15 (10.6) |

| 80%-100% | 49 (34.5) |

| Main patient pattern | |

| Outpatients | 48 (33.8) |

| Inpatients | 5 (3.5) |

| Mixed | 89 (62.7) |

Answers to the survey

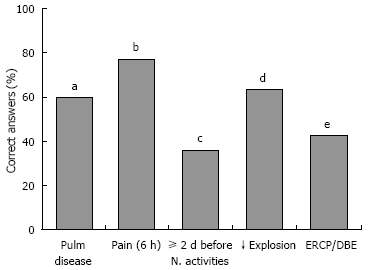

Fewer than half of the respondents (66/142, 46.5%) were aware that room air could be replaced by CO2 for gut distension during endoscopy. Thirty-eight respondents (26.8%) had previously seen (n = 24) or performed (n = 14) an endoscopy procedure using CO2, with only six of them actually practicing this technique (adoption rate of the technique in the whole population, 4.2%). Fifty-eight (87.9%) of the 66 respondents who were aware of the technique also stated that all RCTs had shown that CO2 insufflation decreased pain and gut distension compared to air insufflation. The proportions of survey respondents who correctly answered questions relating to various aspects of CO2 use during endoscopy are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Percentages of correct answers (yes/no choice; correct answer was yes in all cases) to the following questions. aCO2 insufflation is not advised in patients with severe pulmonary diseases; bAbout 20% of patients still have pain 6 h after colonoscopy using air insufflation; cAbout 20% of patients need ≥ 2 d before they are able to return to their normal activities after screening colonoscopy; dCompared to air, CO2 colonoscopy decreases the risk of bowel explosion; eCompared to air, CO2 insufflation is better for ERCP and double balloon enteroscopy DBE.

One hundred and thirty endoscopists answered why they did not use CO2: 73 (56.1%) of them were not aware of this possibility, and those who were aware most often cited “technical difficulties in implementing the system” and “advantages not significant enough for the patient” [n = 48 (84%) and 28 (49%), respectively; two answers were permitted for this item]. Marginal answers included the risk of patient carbonarcosis (n = 6) and of CO2 inhalation by the endoscopy personnel (n = 4).

Reasons that could motivate a change in their practice were stated by 127 endoscopists: a demonstration of the use of CO2 [in a workshop (n = 61; 48.0%) or in their endoscopy unit (n = 50; 39.4%)], and proposal of a CO2 insufflator as an option when buying a colonoscope (n = 44; 34.6%) were the most frequently cited answers. Other answers were less frequent [5% higher reimbursement for CO2 compared to air colonoscopy (n = 16; 12.6%); virtual colonoscopy performed close to their practice using CO2 insufflation (n = 9; 7.1%)]. Four endoscopists reported that they had attempted implementing CO2, but that they had abandoned it because of costs.

Four endoscopists who were actually using CO2 compared it with air colonoscopy. CO2 was rated as similar to air in terms of ease of use, endoscopist comfort and patient comfort during colonoscopy, but better with respect to post-procedure patient comfort, and more expensive (all answers were identical, except for one endoscopist who rated CO2 as better for patient comfort during colonoscopy).

DISCUSSION

CO2 was used for gut distension during endoscopy by < 5% of survey respondents, even though all RCTs performed since the description of the technique 35 years ago have shown that pain is lower with CO2 compared to air[1,3,4–6,9,14]. Indeed, the adoption rate found in the present study was even lower than that reported 20 years ago in a survey of US hospitals in Illinois (13% for colonoscopy)[15]. A majority of endoscopists were not aware at all of the possible use of CO2 during endoscopy, while the remainder ignored recent practical developments (they cited technical difficulties in implementing CO2 as the main factor limiting its adoption, even though CO2 insufflators have become more widely available). The other major reason cited for not adopting CO2 was that advantages for the patients were not sufficiently significant. This likely relates to a lack of information among endoscopists about post-colonoscopy patient inconvenience (only one-third of them knew that 20% of patients need ≥ 2 d before being able to return to their normal activities after screening colonoscopy)[16].

Endoscopists currently pay more attention to patients’ comfort; for example, polyethylene glycol is being replaced by sodium phosphate for bowel preparation before colonoscopy[17]. However, recent reports have shown that phosphate nephropathy may complicate bowel preparation using sodium phosphate, even after a single preparation[18]. Another example is the use of propofol for sedation in replacement of benzodiazepines[19]. CO2 deals with the post-procedure phase of colonoscopy by reducing bloating and abdominal pain, the most frequent side effects of colonoscopy[16]. However, it remains to be demonstrated if the advantages conferred by CO2 are sufficiently significant to improve patient acceptance of endoscopic procedures and cost-effectiveness (by reducing loss from normal activities after endoscopy). These two criteria, namely patient acceptance and cost-effectiveness, are of paramount importance for colorectal cancer screening as computed tomography (CT) colonography has been shown to be superior to colonoscopy for both of them[20,21]. Incidentally, one of the three CO2 insufflators that are available for endoscopy was developed initially for gut distension during CT colonography, and radiologists use it increasingly often for reasons of safety and patient comfort (CO2 is used in about half of CT colonographies)[22]. In our survey, the use of CO2 for CT colonography was not perceived by endoscopists as an incentive to change their practice. As endoscopists become aware of the ease and benefits of CO2 implementation in an endoscopy suite, the use of CO2 may be the next logical step to minimize patient discomfort.

Most endoscopists reported that a demonstration (in their endoscopy unit or in a workshop) was likely to change their perception of CO2 usefulness. This corroborates our previous observation that endoscopists’ opinion may significantly change following a demonstration of a particular endoscopy technique[23]. However, it remains to be seen if intentions translate into actual changes, in particular, because CO2 benefits are mainly observed after sedation reversal, when many patients are not evaluated by endoscopists.

From a practical standpoint, CO2 is readily available in centers where laparoscopic surgery is performed (or it can be purchased from various distributors), and endoscopic CO2 insufflators have recently become more widely available (Table 2). CO2 insufflators are electrically powered devices that combine at the minimum a gas pressure regulator, a safety pressure valve to protect against over-insufflation, and connection tubes. When CO2 is used, the regular air insufflation is inactivated (to prevent endoscopic insufflation with both gases), and endoscope manipulation is unchanged compared to using air for gut distension (CO2 insufflation is obtained by placing the finger on the vent hole of the insufflation/irrigation valve, and lens cleaning is obtained by firmly pressing this valve). One may also switch from one gas to another during an endoscopic procedure. Contraindications to the use of CO2 are limited to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (if CO2 is absorbed at a rate exceeding its respiratory elimination, this leads to CO2 retention and pulmonary acidosis)[24]. Provided that this contraindication is observed, Bretthauer et al[3] have shown that, although pCO2 levels increase during colonoscopy and ERCP (due to the effect of sedative drugs), this increase is no more important with CO2 than with air insufflation[4,9].

Table 2.

Characteristics of CO2 insufflators available for gut distension during endoscopy

| CO2-efficient | Olympus keymed ECR | Olympus UCR | |

| Weight (kg) | 9.0 | 26.0 | 4.9 |

| Size (mm) | 254 × 140 × 254 | 420 × 1049 × 539 | 130 × 156 × 334 |

| Output of CO2 adjustable | No1 | No | No |

| Indicator of the amount of gas delivered | Yes | No | No |

| Indicator of “empty tank” | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| FDA approved/CE mark | Yes/Yes | Yes/Yes | Yes/Yes |

| Availability | International | United Kingdom | International |

| Price (euros) | 7400 | NA | 7000 |

| Manufacturer | Bracco Imaging SPA, San Donato Milanese, Italy | Olympus Keymed, Southend-on-Sea, UK | Olympus, Tokyo, Japan |

FDA: Food and Drug Administration; NA: not available.

When the vent hole of the insufflation/irrigation valve is not occluded, CO2 flow decreases from 3 L/min to a managed flow of 0.25 L/min, in order to preserve CO2 reserves. None of the three models allows selecting between different intensities of CO2 flow (in contrast with the selection of low/medium/high intensities of air flow with air insufflators).

Finally, the cost of an insufflator was cited as a limiting factor by endoscopists who attempted to implement the system. The cost of an insufflator ranges between 7000 and 7400 euros. The cost of CO2 gas per colonoscopy is < 1 euro (renting a 2400-L CO2 tank costs about 50 euros/year, and refilling it costs 25 euros; this volume is sufficient for 800 min of continuous insufflation; a mean of 8.3 L is used per colonoscopy procedure)[25]. The acquisition cost should be viewed in light of the multiple uses of these systems (e.g. colonoscopy, ERCP, double balloon enteroscopy) and ideally, from a societal perspective. Indeed, if cost calculations of screening colonoscopy took into account total time lost from work for patients undergoing the examination, as well as for the person accompanying the patient, this would increase the cost by about 50%[26]. A catalyst for CO2 adoption by endoscopists could be the implementation of CO2 insufflation capabilities into standard endoscopy processors, as additional costs would be hard to justify in the absence of specific reimbursement. The endoscope manufacturer that would first take this step would have a competitive advantage.

Our study has several potential limitations, including selection bias and the relatively limited number of responders. However, survey respondents were distri-buted relatively evenly between different endoscopy practices, and an international audit with a larger panel of individual respondents than reported here is notably difficult to organize[27,28].

In conclusion, the use of CO2 for gut distension during endoscopy remains exceptional despite the results of numerous RCTs that have shown the superiority of this technique compared to air. A majority of endoscopists are unaware of this possibility, while those who are aware mostly think that CO2 implementation in an endoscopy suite is technically difficult or presents few advantages. Greater availability of CO2 insufflators, more widespread use of CO2 in competing CT colonography, and better endoscopists’ education have the potential to change this situation.

COMMENTS

Background

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is cleared much more rapidly than air from the bowel and randomized controlled trials have consistently shown that it is superior to air for several gastrointestinal endoscopy procedures. In particular, advantages were demonstrated for colonoscopy (less pain), endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (less pain), double balloon enteroscopy (deeper bowel intubation), and long, complex, therapeutic procedures (fewer sedative drugs).

Research frontiers

Use of CO2 is common for colon computed tomography but it does not seem to be widespread in endoscopy practice. Reasons for possible non-adoption of this gas are unknown.

Innovations and breakthroughs

No data about the use of CO2 by endoscopists have been available for > 20 years. Recently, CO2 insufflators for endoscopy have become commercially available.

Applications

As a majority of endoscopists were not aware of the possibility to use CO2 as air replacement during endoscopy, specific endoscopists’ education and implementation of CO2 insufflation capabilities into standard endoscopy processors should be encouraged.

Peer review

The cost of equipment required for CO2 insufflation during endoscopy is the main barrier to adoption of this technique; it is actually around 7000 euros.

Peer reviewer: William Dickey, Altnagelvin Hospital, Londonderry, BT47 6SB, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Rogers BH. The safety of carbon dioxide insufflation during colonoscopic electrosurgical polypectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1974;20:115–117. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(74)73900-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hussein AM, Bartram CI, Williams CB. Carbon dioxide insufflation for more comfortable colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1984;30:68–70. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(84)72319-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bretthauer M, Thiis-Evensen E, Huppertz-Hauss G, Gisselsson L, Grotmol T, Skovlund E, Hoff G. NORCCAP (Norwegian colorectal cancer prevention): a randomised trial to assess the safety and efficacy of carbon dioxide versus air insufflation in colonoscopy. Gut. 2002;50:604–607. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.5.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bretthauer M, Lynge AB, Thiis-Evensen E, Hoff G, Fausa O, Aabakken L. Carbon dioxide insufflation in colonoscopy: safe and effective in sedated patients. Endoscopy. 2005;37:706–709. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevenson GW, Wilson JA, Wilkinson J, Norman G, Goodacre RL. Pain following colonoscopy: elimination with carbon dioxide. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:564–567. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(92)70517-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sumanac K, Zealley I, Fox BM, Rawlinson J, Salena B, Marshall JK, Stevenson GW, Hunt RH. Minimizing postcolonoscopy abdominal pain by using CO(2) insufflation: a prospective, randomized, double blind, controlled trial evaluating a new commercially available CO(2) delivery system. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:190–194. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Church J, Delaney C. Randomized, controlled trial of carbon dioxide insufflation during colonoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:322–326. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6549-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domagk D, Bretthauer M, Lenz P, Aabakken L, Ullerich H, Maaser C, Domschke W, Kucharzik T. Carbon dioxide insufflation improves intubation depth in double-balloon enteroscopy: a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. Endoscopy. 2007;39:1064–1067. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bretthauer M, Seip B, Aasen S, Kordal M, Hoff G, Aabakken L. Carbon dioxide insufflation for more comfortable endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. Endoscopy. 2007;39:58–64. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-945036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keswani R, Hovis R, Edmunowicz S, Sadeddin E, Jonnalagadda S, Azar R, Waldbaum L, Maple J. Carbon dioxide (CO2) insufflation during ERCP for the reduction of post-procedure pain: preliminary results of a randomized, double-blind controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:AB107. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saito Y, Uraoka T, Matsuda T, Emura F, Ikehara H, Mashimo Y, Kikuchi T, Kozu T, Saito D. A pilot study to assess the safety and efficacy of carbon dioxide insufflation during colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection with the patient under conscious sedation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:537–542. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mciver MA, Redfield AC, Benedict EB. Gaseous exchange between the blood and the lumen of the stomach and intestines. Am J Physiol. 1926;76:92–111. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saltzman HA, Sieker HO. Intestinal response to changing gaseous environments: normobaric and hyperbaric observations. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1968;150:31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1968.tb19028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bretthauer M, Hoff G, Thiis-Evensen E, Grotmol T, Holmsen ST, Moritz V, Skovlund E. Carbon dioxide insufflation reduces discomfort due to flexible sigmoidoscopy in colorectal cancer screening. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:1103–1107. doi: 10.1080/003655202320378329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phaosawasdi K, Cooley W, Wheeler J, Rice P. Carbon dioxide-insufflated colonoscopy: an ignored superior technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:330–333. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(86)71877-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ko CW, Riffle S, Shapiro JA, Saunders MD, Lee SD, Tung BY, Kuver R, Larson AM, Kowdley KV, Kimmey MB. Incidence of minor complications and time lost from normal activities after screening or surveillance colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:648–656. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan JJ, Tjandra JJ. Which is the optimal bowel preparation for colonoscopy - a meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:247–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heher EC, Thier SO, Rennke H, Humphreys BD. Adverse renal and metabolic effects associated with oral sodium phosphate bowel preparation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1494–1503. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02040408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rex DK, Heuss LT, Walker JA, Qi R. Trained registered nurses/endoscopy teams can administer propofol safely for endoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1384–1391. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hassan C, Pickhardt PJ, Laghi A, Kim DH, Zullo A, Iafrate F, Di Giulio L, Morini S. Computed tomographic colonography to screen for colorectal cancer, extracolonic cancer, and aortic aneurysm: model simulation with cost-effectiveness analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:696–705. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.7.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gluecker TM, Johnson CD, Harmsen WS, Offord KP, Harris AM, Wilson LA, Ahlquist DA. Colorectal cancer screening with CT colonography, colonoscopy, and double-contrast barium enema examination: prospective assessment of patient perceptions and preferences. Radiology. 2003;227:378–384. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2272020293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pickhardt P. Incidence of significant complications at CT colonography: collective experience of the working group on virtual colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:AB202. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dumonceau JM, Dumortier J, Deviere J, Kahaleh M, Ponchon T, Maffei M, Costamagna G. Transnasal OGD: practice survey and impact of a live video retransmission. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:776–783. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen NT, Wolfe BM. The physiologic effects of pneumoperitoneum in the morbidly obese. Ann Surg. 2005;241:219–226. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000151791.93571.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bretthauer M, Hoff GS, Thiis-Evensen E, Huppertz-Hauss G, Skovlund E. Air and carbon dioxide volumes insufflated during colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:203–206. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jonas DE, Russell LB, Sandler RS, Chou J, Pignone M. Value of patient time invested in the colonoscopy screening process: time requirements for colonoscopy study. Med Decis Making. 2008;28:56–65. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07309643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goel A, Barnes CJ, Osman H, Verma A. National survey of anticoagulation policy in endoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:51–56. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3280120eb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ladas SD, Aabakken L, Rey JF, Nowak A, Zakaria S, Adamonis K, Amrani N, Bergman JJ, Boix Valverde J, Boyacioglu S, et al. Use of sedation for routine diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Survey of National Endoscopy Society Members. Digestion. 2006;74:69–77. doi: 10.1159/000097466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]