Abstract

AIM: To determine the frequency and characteristics of extracolonic lesions detected using computed tomographic (CT) colonography.

METHODS: The significance of extracolonic lesions was classified as high, intermediate, or low. Medical records were reviewed to establish whether further investigations were carried out pertaining to the extracolonic lesions that were detected by CT colonography.

RESULTS: A total of 920 cases from 7 university hospitals were included, and 692 extracolonic findings were found in 532 (57.8%) patients. Of 692 extracolonic findings, 60 lesions (8.7%) were highly significant, 250 (36.1%) were of intermediate significance, and 382 (55.2%) were of low significance. CT colonography revealed fewer extracolonic findings in subjects who were without symptoms (P < 0.001), younger (P < 0.001), or who underwent CT colonography with no contrast enhancement (P = 0.005). CT colonography with contrast enhancement showed higher cost-effectiveness in detecting highly significant extracolonic lesions in older subjects and in subjects with symptoms.

CONCLUSION: Most of the extracolonic findings detected using CT colonography were of less significant lesions. The role of CT colonography would be optimized if this procedure was performed with contrast enhancement in symptomatic older subjects.

Keywords: Computed tomographic colonography, Extracolonic lesion, Cost, Contrast enhancement, Clinical availability

INTRODUCTION

Computed tomographic (CT) colonography allows the visualization of extracolonic organs, thereby permitting the detection of potentially significant pathologies beyond the colon[1]. Extracolonic lesions are found in 15%-85% of cases, with some being important lesions, such as extracolonic cancer or aortic aneurysm[2,3]. However, most of the extracolonic lesions are of minimal importance and lead to further investigations and possibly procedures, with the final diagnosis being simple benign pathology[2]. Thus, the evaluation and management of extracolonic findings have been found to lead to significant additional cost, and the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of CT colonography needs to be carefully evaluated[4].

Since multi-section helical CT colonography was first introduced in 1998, improvements such as faster scanning, improved temporal resolution and reduced motion artifacts have been implemented[5]. However, multidetector CT colonography has been described as a sort of Pandora’s box, releasing a cascade of diagnostic events with medicolegal, ethical and economic implications[6]. Therefore, it would be helpful to clinicians if there were defined strategies for the clinical approach toward the detection of highly significant extracolonic lesions.

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no large multicenter study on extracolonic findings of CT colonography among Koreans. We therefore performed a multicenter study to assess the frequency and characteristics of extracolonic lesions detected with the aid of CT colonography. In addition, we surveyed the factors related to the detection of highly significant extracolonic findings, and analyzed its cost-effectiveness to determine which factors would enhance the potential benefits of CT colonography examination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

The results of CT colonographies performed from January 2005 to December 2006 at the authors’ seven university hospitals in Korea were reviewed. Those who were diagnosed as having a malignancy at the time of the CT colonography, those under the age of 16 years and those with ethnicity other than Korean were excluded from the study.

Types and scanning parameters of multidetector array CT colonography are summarized in Table 1. The subjects underwent standard bowel preparation, and a rectal catheter was inserted. Air was used to distend the colon to maximum subject tolerance. Scout image was taken to confirm the adequacy of distention before each examination. Images were taken from the diaphragm to the symphysis with the subject in the supine and prone positions during a breath hold. Medical records were reviewed to establish whether further investigation was carried out pertaining to the extracolonic lesions that were detected by CT colonography during 1 year follow up period. This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review boards which confirmed that the study was in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Hospital | Number of the subjects | Type of CT colonogrphy | kVp | mAs | Pitch | Slice thickness/reconstruction intervalfor extracolonic finding (mm) |

| A | 278 | Sensation 64; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany | 120 | 70 | 1.5 | 3/3 |

| B | 157 | LightSpeed Ultra 8 or 16; GE Medical systems, Milwaukee, WI | 120 | 70 | 1.35 | 1.25/1.25 |

| C | 152 | Sensation 16; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany | 120 | 30 | 1 | 5/5 |

| D | 135 | Brilliance 40-channel MDCT, Phillips Medical System, Netherlands | 120 | 160 | 1.176 | 0.5/0.9 |

| E | 92 | LightSpeed 16; GE healthcare, Milwaukee, Wis | 120 | 200 | 1.375 | 1.25/3.75 |

| F | 65 | MX 8000 IDT 16, Phillips Eindhoven, Netherlands | 120 | 200 | 1 | 2/1 |

| G | 41 | Sensation 16; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany | 120 | 30 | 1 | 5/5 |

Classification of extracolonic lesions

Extracolonic lesions were divided into three categories, according to previous reports[7,8]. Highly significant lesions include those requiring immediate surgical therapy, medical intervention, and/or further investigation. Examples of highly significant extracolonic lesions include a solid organ mass, adrenal mass greater than 3 cm, aortic aneurysm greater than 3 cm, lymphadenopathy greater than 1 cm, cardiomegaly, pericardial effusion, fistula, abscess and small-bowel infarction.

Lesions of intermediate significance include conditions that do not require immediate therapy but would likely require further investigation, recognition, or therapy at a later time. Examples of such extracolonic lesions include calculi, intermediate cysts, pulmonary fibrosis, inguinal hernia, uterine myoma, endometriosis, pelvic fluid collection, liver cirrhosis, liver hemangioma and bile duct dilatation.

Lesions of low significance include benign conditions that do not require further medical therapy or additional work-up. Examples of such extracolonic lesions include calcifications, granulomas, diverticulosis, simple organ cysts, hernias, pleural thickening, benign prostatic hypertrophy, accessory spleen, benign bony lesion, fatty liver, and renal infarction.

Statistical analyses

Differences between the groups were analyzed using the chi-square test and Student’s t-test. The age was expressed as mean ± SD (standard deviation) values. Cost effectiveness was calculated by cost needed for detecting one highly significant lesion (cost of CT colonography × total number of CT colonography/number of subjects with highly significant extracolonic lesions). Regression analysis was performed to assess the related factors in detecting extracolonic lesions according to their significance. A probability value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the subjects

A total of 920 consecutive subjects (men/women = 535/385) were analyzed. Their mean age (± SD) was 57.3 ± 12.8 (range, 34-87). Of these, 692 extracolonic findings were found in 532 (57.8%) subjects (Table 2). Of the 692 extracolonic findings, 60 (8.7%) were highly significant, 250 (36.1%) were of intermediate significance, and 382 (55.2%) were of low significance (Table 3). Data regarding the examination, age, and sex distribution of each group are summarized in Table 4.

Table 2.

Results of 920 computed tomographic colonoscopy examinations n (%)

| Number of extracolonic findings | Number of subjects |

| 0 | 388 (42.2) |

| 1 | 403 (43.8) |

| 2 | 105 (11.4) |

| 3 | 19 (2.1) |

| 4 | 5 (0.5) |

Table 3.

Proportion of extracolonic lesions according to the clinical significance

| Extracolonic findings | Number |

| Highly significant (n = 60) | |

| Solid organ mass including malignancy | 421 |

| Cardiomegaly/pericardial effusion | 5 |

| Lymphadenopathy greater than 1 cm | 3 |

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis | 3 |

| Abscess | 3 |

| Aortic lesion | 2 |

| Small bowel obstruction | 2 |

| Intermediately significant (n = 250) | |

| Benign solid organ lesion | 1412 |

| Renal stone/hydronephrosis | 28 |

| Gall bladder stone/polyp/cholecystitis | 22 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 13 |

| Bile duct stone/dilatation/hemobilia | 9 |

| Small bowel inflammation | 8 |

| Vascular lesion (aortic stenosis, varix, etc) | 6 |

| Bronchiectasis/emphysema | 5 |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | 5 |

| Pleural effusion | 3 |

| Inguinal hernia | 3 |

| Ascites of unknown cause | 3 |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 2 |

| Mesenteric fat necrosis | 1 |

| Spinal stenosis with destruction | 1 |

| Lowly significant (n = 382) | |

| Renal cyst | 143 |

| Hepatic cyst | 114 |

| Fatty liver | 39 |

| Vascular calcification/atherosclerosis | 19 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease/pleural thickening | 16 |

| Accessory spleen/splenic infarction | 15 |

| Hepatic calcification | 10 |

| Benign osteolytic lesion | 8 |

| Hiatal hernia | 6 |

| Benign prostatic hypertrophy | 5 |

| Colonic diveticulosis | 4 |

| Tiny pancreas cyst | 1 |

| Mesenteric calcification | 1 |

| Gallbladder sludge | 1 |

Liver 9, lung 9, stomach 7, pancreas 3, kidney 3, bladder 3, adrenal gland 2, small bowel 2, bone 1, bile duct 1, psoas muscle 1 and ovary 1.

Liver 46, kidney 30, uterus 19, ovary 13, lung 9, adrenal gland 8, lymph node 7, muscle 4, pancreas 3, spleen 1 and testis 1.

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics according to the clinical significance of extracolonic lesions n (%)

| Highly significant lesion (n = 60) | Intermediately significant lesion (n = 250) | Lowly significant lesion (n = 382) | No extracolonic lesion (n = 388) | P-value | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 58.3 ± 16.4 | 57.9 ± 13.8 | 59.0 ± 11.9 | 54.4 ± 13.1 | < 0.001 |

| Male:Female | 36:24 | 116:134 | 237:145 | 233:155 | 0.001 |

| Indication | < 0.001 | ||||

| Screening | 16 (26.7) | 76 (30.4) | 155 (40.6) | 160 (41.2) | |

| Family history | 1 (1.7) | 4 (1.6) | 4 (1.0) | 13 (3.4) | |

| Past history | 10 (16.7) | 38 (15.2) | 55 (14.4) | 93 (24.0) | |

| GI bleeding | 5 (8.3) | 19 (7.6) | 11 (2.9) | 17 (4.4) | |

| IDA | 1 (1.7) | 7 (2.8) | 8 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Bowel habit change | 6 (10.0) | 27 (10.8) | 44 (11.5) | 38 (9.8) | |

| Abdominal pain | 17 (28.2) | 58 (23.2) | 78 (20.4) | 56 (14.4) | |

| Others | 4 (6.7) | 21 (8.4) | 27 (7.1) | 11 (2.8) | |

| CT with enhancement1 | 53 (88.3) | 225 (90.0) | 320 (83.7) | 305 (78.6) | 0.001 |

| Hospital | < 0.001 | ||||

| A (n = 313) | 23 (38.4) | 61 (24.4) | 77 (20.2) | 151 (38.9) | |

| B (n = 214) | 9 (15.0) | 86 (34.4) | 86 (22.6) | 33 (8.5) | |

| C (n = 171) | 5 (8.3) | 24 (9.6) | 60 (15.7) | 81 (20.9) | |

| D (n = 149) | 2 (3.3) | 31 (12.4) | 70 (18.3) | 45 (11.6) | |

| E (n = 104) | 10 (16.7) | 20 (8.0) | 44 (11.5) | 30 (7.7) | |

| F (n = 73) | 5 (8.3) | 16 (6.4) | 12 (3.1) | 40 (10.3) | |

| G (n = 59) | 6 (10.0) | 12 (4.8) | 33 (8.6) | 8 (2.1) |

Computed tomography with pre- and post-contrast images enhanced by intravenous contrast. SD: Standard deviation; GI: Gastrointestinal; IDA: Iron deficiency anemia.

Of 920 subjects, 764 and 156 subjects were examined by CT colonography with and without the aid of contrast enhancement, respectively. Extracolonic lesions were found in 459 of the 764 subjects (60.1%) examined with contrast enhancement, but in only 73 of the 156 subjects (46.8%) examined without contrast enhancement (P = 0.005).

Factors related to the clinical significance of extracolonic findings

The mean age was lower in cases without extracolonic findings (Table 4). With regard to indications for CT colonography, gastrointestinal symptoms were more common in those in whom significant lesions were detected (Table 4). Regression analysis revealed that, older age (P < 0.001), being female (P = 0.001), presence of symptoms (P < 0.001), and the use of contrast during CT colonography (P = 0.003) were associated with detection of the more significant extracolonic lesions.

Additional evaluation and management of extracolonic findings

Table 5 lists the additional tests performed in each group. It can be seen that, 81.7% of highly significant subjects received further treatment, while such treatment was received in only 20.8% and 2.9% of subjects of intermediate and low significance, respectively.

Table 5.

Further managements according to the clinical significance of extracolonic lesions n (%)

| Highly significant lesion (n = 60) | Intermediately significant lesion (n = 250) | Lowly significant lesion (n = 382) | |

| Diagnostic intervention | |||

| US | 6 (10.0) | 108 (43.2) | 31 (8.1) |

| CT | 17 (28.3) | 65 (26.0) | 21 (5.5) |

| MRI | 4 (6.7) | 14 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Biopsy | 8 (13.3) | 3 (1.2) | 2 (0.5) |

| Endoscopy | 6 (10.0) | 6 (2.4) | 1 (0.3) |

| Other tests | 18 (30.0) | 25 (10.0) | 10 (2.6) |

| Not done | 1 (1.7) | 29 (11.6) | 317 (83.0) |

| Therapeutic intervention | 49 (81.7) | 52 (20.8) | 11 (2.9) |

US: Ultrasonography; CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging.

Cost of finding a highly significant extracolonic lesion

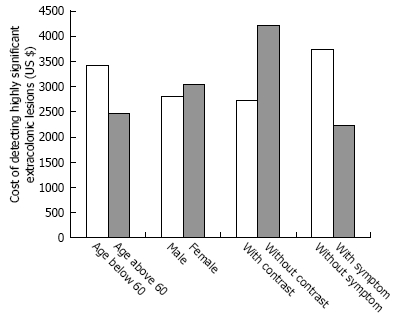

Since each CT colonography procedure costs US $ 190 (180 000 won) in Korea, US $ 2905 (2 760 000 won) was needed to detect each highly significant lesion in our study (i.e. cost of CT colonography × total CT colonography cases/number of subjects with highly significant extracolonic lesions). The following factors were found to be associated with poor cost-effectiveness: patient age below 60 years, lack of symptoms and use of CT colonography without contrast enhancement (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cost of detecting highly significant extracolonic lesions. Cost-effectiveness was assessed using the following calculation for each group. Poor cost-effectiveness in the detection of highly significant lesions was observed for subjects aged below 60 year-old (US $ 3442), subjects without symptoms (US $ 3737), and CT colonography performed without contrast enhancement (US $ 4221).

DISCUSSION

In this study, extracolonic lesions were found in 532 out of 920 subjects (57.8%), which is consistent with previous studies reporting incidences of between 33% and 85%[2–4,6,8,9]. A substantial proportion of these lesions were insignificant, which led to further unnecessary workup and, hence, additional cost. Highly significant extracolonic lesions were detected in the present study in only 60 of 920 subjects (6.5%), which is slightly lower than the incidences found in previous studies. This discrepancy might be due to differences in the study population (ours included only Koreans), the definition of highly significant lesion used and the CT colonography conditions used. In our study, a solid organ mass suspicious of malignancy was detected in 42 of 920 (4.6%) subjects. Considering that substantial numbers of subjects undergoing CT colonography are found to have clinically important extracolonic findings, this would have positive effects on health care by undergoing additional evaluations[10]. The cost of a CT colonography in Korea, i.e. US $190 (180 000 won), is only US $ 53 (50 000 won) more expensive than colonoscopy. Therefore, CT colonography might be more attractive in Korea, since is it less expensive when compared with US[11,12]. Several studies have reported on a prospective cost-benefit analysis of diagnostic CT colonography[10,13]. Some reported low clinical relevant disease in average-risk asymptomatic adults[14], while others revealed higher proportion of colon cancers in subjects with colonic symptoms[13]. We further tried to idebtify the factors associated with the more effective use of CT colonography by analyzing the cost of detecting highly significant extracolonic lesions. As expected, the prevalence of significant extracolonic lesions was higher in older subjects and those with gastrointestinal symptoms. Since our results suggest that significant extracolonic lesions can be anticipated at a higher frequency in this population than in an asymptomatic younger population, they also contribute toward a better understanding of the selection of subjects who would benefit more effectively from CT colonography.

Apart from age and clinical symptoms, contrast enhancement was found to be advantageous in identifying extracolonic lesions on CT colonography. This demonstrates that some important extracolonic lesions might have been overlooked in non-contrast enhanced cases. The inability of low-radiation dose CT colonography to accurately define lesions in other organs also raises important medico-legal considerations[2]. Based on our findings, age, the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms and the use of contrast enhancement must be taken into account when deciding when to use CT colonography in routine clinical practice.

In the present study, 221 of 250 (88.4%) subjects with extracolonic lesions of intermediate significance were referred for further investigations, of which 52 (20.8%) received treatment, while 65 of 382 (17.0%) subjects with extracolonic lesion of low significance were referred for further investigations, of which only 11 (2.9%) received treatment. Because symptomatic subjects were included in our study, CT colonography was performed as a diagnostic evaluation as well as a screening tool. This would explain why further investigations frequently followed CT colonography. Our results indicate that further investigations pertaining to extracolonic lesions, other than those of high significance, benefit only a few and result in additional and unnecessary cost as a result of unnecessary workups.

The limitation of our study is that there were some differences due to inhomogenous settings. Different participating institutions used such relevant differences in study protocols: Slice thickness varies between 0.5 and 5 mm and mAs varies between 30 and 200. The radiation dose was in the range of 1.7-8.8 mSv, with a median of 3.9 mSv. It was comparatively larger than simple X-ray or plain abdomen with approximately 0.1 mSv. For example, the hospitals D, E and F used almost standard dose contrast, while slice thickness were less than 1 mm for extracolonic lesions at the hospitals B, D and F. However, when considering that the proportions of normal extracolonic findings were highest in hospital F (54.5%) > A (48.2%) > C (47.3%) > D (30.2%) > E (28.8%) > B (15.4%) > G (13.6%), slice thickness and standard dose are not predictive factors of the presence of extracolonic lesions. Another limitation concerns the number of false positive and false negative results of the exam. Since study populations have not been followed up periodically, correct false positivity and negativity could not be evaluated. However, subjects diagnosed as having significant extracolonic lesions received full evaluation and treatment for their lesions. Accordingly, false positivity of significant extracolonic lesions was nearly zero.

In conclusion, most of the extracolonic lesions detected by CT colonography were of low significance, and resulted in additional costly investigations. However, CT colonography may demonstrate asymptomatic malignant disease requiring immediate treatment in older subjects and among those with symptoms, particularly when performed with contrast enhancement. Based on these results, CT colonography should be performed with contrast enhancement in symptomatic older subjects.

COMMENTS

Background

Currently, computed tomographic (CT) colonography is widely used in the clinical field to visualize colon and extracolonic lesions. Extracolonic lesions occur in 15%-85% of cases, with some being important lesions, such as extracolonic cancer or aortic aneurysm. The utilization of CT colonography will increase in clinical field, and research for availability, detection rate and cost-effectiveness of CT colonography is necessary.

Research frontiers

Early detection of extracolonic lesions is an aim of CT colonography. In particular, the detection of significant lesions is very important. However, the incidence rates of significant extracolonic lesions vary from country to country, and most reports relate to the Western population. This is the first study focusing on the Asian population, where the incidence rate of colorectal disease is lower than in the Western population.

Innovations and breakthroughs

In recent reports, cost-effectiveness of CT colonography was calculated in US dollars, because most studies were carried out in the USA. However, the cost of CT colonography varies according to different countries. This study evaluated its cost-effectiveness taking into consideration the specific medical system of the country. In addition, optimal methods to detect significant extracolonic lesions were evaluated. This study showed that the selective use of CT colonoscopy (for symptomatic elderly and with contrast enhancement) shows a good cost-effectiveness.

Applications

Use of CT colonography is currently rising due to its various functions. However, cost of CT colongraphy is comparatively high, and clinical availability is being evaluated. This study is helpful to clinicians to determine the best way to use the CT colonography for detecting highly significant extracolonic lesions.

Terminology

Multi-section helical CT colonography was first introduced in 1998. There have many improvements such as faster scanning, improved temporal resolution, and reduced movement artifacts. Various approaches were tried to increase the effectiveness of CT colonography, and contrast enhancement is recommended as a good strategy if it is applied to an ideal case.

Peer review

The authors examined the cost-effectiveness of CT colonography for various Korean patients, and proposed how to optimize the use of CT colonography. Considering the rising application of CT colonography to the medical field, this study will provide a good basis to guide its use.

Supported by Korean Association for the Study of Intestinal diseases (KASID)

Peer reviewer: Vito Annese, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Unit of Gastroenterology, Hospital, Viale Cappuccini, 1, San Giovanni Rotondo 71013, Italy

S- Editor Li LF L- Editor Negro F E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Burling D, Taylor SA, Halligan S. Virtual colonoscopy: current status and future directions. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2005;15:773–795. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards JT, Wood CJ, Mendelson RM, Forbes GM. Extracolonic findings at virtual colonoscopy: implications for screening programs. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3009–3012. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hellström M, Svensson MH, Lasson A. Extracolonic and incidental findings on CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy) AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:631–638. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.3.1820631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hara AK, Johnson CD, MacCa-rty RL, Welch TJ. Incidental extracolonic findings at CT colonography. Radiology. 2000;215:353–357. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.2.r00ap33353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rockey DC. Colon imaging: computed tomographic colonography. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S37–S41. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ginnerup Pedersen B, Rosenkilde M, Christiansen TE, Laurberg S. Extracolonic findings at computed tomography colonography are a challenge. Gut. 2003;52:1744–1747. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.12.1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sosna J, Kruskal JB, Bar-Ziv J, Copel L, Sella T. Extracolonic findings at CT colonography. Abdom Imaging. 2005;30:709–713. doi: 10.1007/s00261-005-0333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gluecker TM, Johnson CD, Wilson LA, Maccarty RL, Welch TJ, Vanness DJ, Ahlquist DA. Extracolonic findings at CT colonography: evaluation of prevalence and cost in a screening population. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:911–916. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajapaksa RC, Macari M, Bini EJ. Prevalence and impact of extracolonic findings in patients undergoing CT colonography. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:767–771. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000139035.38568.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yee J, Kumar NN, Godara S, Casamina JA, Hom R, Galdino G, Dell P, Liu D. Extracolonic abnormalities discovered incidentally at CT colonography in a male population. Radiology. 2005;236:519–526. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2362040166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vijan S, Hwang I, Inadomi J, Wong RK, Choi JR, Napierkowski J, Koff JM, Pickhardt PJ. The cost-effectiveness of CT colonography in screening for colorectal neoplasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:380–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00970.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng CS, Freeman AH. Incidental lesions found on CT colonography: their nature and frequency. Br J Radiol. 2005;78:20–21. doi: 10.1259/bjr/30856690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan KY, Xiong T, McCafferty I, Riley P, Ismail T, Lilford RJ, Morton DG. Frequency and impact of extracolonic findings detected at computed tomographic colonography in a symptomatic population. Br J Surg. 2007;94:355–361. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pickhardt PJ, Taylor AJ. Extracolonic findings identified in asymptomatic adults at screening CT colonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:718–728. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]