Abstract

Herpesviruses have evolved numerous strategies to subvert host immune responses so they can coexist with their host species. These viruses ‘co-opt’ host genes for entry into host cells and then express immunomodulatory genes, including mimics of members of the tumour-necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily, that initiate and alter host-cell signalling pathways. TNF superfamily members have crucial roles in controlling herpesvirus infection by mediating the direct killing of infected cells and by enhancing immune responses. Despite these strong immune responses, herpesviruses persist in a latent form, which suggests a dynamic relationship between the host immune system and the virus that results in a balance between host survival and viral control.

The immune system has evolved to provide protection against the many pathogens that are encountered throughout the lifetime of an individual. In turn, the selective pressure that is exerted by the immune system has shaped the evolution of pathogens. This co-evolutionary relationship between host and pathogen is particularly clear for viruses that establish persistent infections, such as herpesviruses (BOX 1). Indeed, analyses of viral genome sequences have shown that herpesvirus genomes encode sequence homologues of host proteins that have a role in the immune system, and many viral gene products have immunomodulatory function. These ‘co-opted’ genes allow the virus to manipulate detection and clearance by the host innate and adaptive immune systems, and this is thought to favour viral replication or persistence in the host. In addition, many host proteins that have basic cellular functions are active during viral infection and might be beneficial to the virus, and other host proteins might facilitate viral infection by performing functions that are unrelated to their normal role (for example, by acting as receptors for the entry of the virus into host cells). Phylogenetic analysis has shown that the evolution of herpesvirus genomes is closely linked to the evolution of host genomes, such that the divergence of herpesvirus species correlates with the divergence of vertebrate orders1. The factors that drive virus-host co-evolution are unclear, although immunomodulation by the virus might be involved.

Both innate and adaptive immune responses can exert strong selective pressure on herpesviruses in infected individuals. For example, infection of mice that lack an adaptive immune system with mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV) results in the rapid accumulation of mutations in selected viral genes, which allows the viral mutants that escape detection by cells of the innate immune system to thrive and overwhelm the host2. However, herpesvirus genomes are remarkably stable in immunocompetent individuals, perhaps because viral latency can only be maintained if mutations of the genome are limited and sufficient viral replicative capacity is retained.

Many viruses, including herpesviruses, have evolved mechanisms to interfere with recognition by innate and adaptive immune cells. However, host recognition of viruses is never completely blocked; viruses must therefore also evade effector immune responses, particularly those that are mediated by cytokines, including interferons (IFNs), chemokines and tumour-necrosis factor (TNF)-related cytokines, in order to propagate. The TNF superfamily of ligands and receptors is involved in signalling pathways that are important during development and host defence3-5, in which they have crucial roles in the regulation of cell survival and death in immune, nervous and ectodermal tissues. Because of this important role in host defence, the TNF superfamily network exerts a strong selection pressure on viruses to evolve strategies that evade responses that are mediated by these host proteins. Indeed, herpesviruses, poxviruses, adenoviruses and other pathogens use multiple strategies to manipulate signalling pathways through TNF superfamily members — for example, viruses express orthologues of TNF receptors (TNFRs) and of their downstream signalling components and target genes that interfere with host signalling pathways6-8. one of the best-known TNFR mimics is the protein M-T2, which is expressed by the poxvirus myxoma virus and was shown to be a virus virulence factor, as infection of rabbits with a M-T2-deficient virus resulted in attenuated disease9. The unique ability of herpesviruses to establish lifelong infections depends on the virus taking advantage of many host-cell processes, including manipulation of host TNFR pathways, to evade clearance by the immune system.

In this review we discuss several aspects of the manipulation of host TNFR pathways by herpesviruses, including the use of host receptors, such as the TNFR herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM; also known as TNFRSF14), for viral entry into cells, and the expression of viral mimics of host TNFRs to manipulate host-cell signalling. In addition, we discuss the recent studies which show that the host counteracts viral-evasion strategies through the co-stimulatory TNFR OX40 (also known as TNFRSF4), and that lymphotoxin-β receptor (LTβR), a key homeostatic regulator of lymphoid organs, limits the spread of herpesviruses from infected cells and maintains splenic architecture and productive immune responses. The selective targeting of the cytokine pathways that are involved in homeostatic processes by herpesviruses suggests an intimate host-pathogen relationship.

Box 1 Infection by herpesviruses.

Herpesviruses are a family of large, double-stranded DNA viruses that infect organisms in a species-specific manner. Primary infection can be subclinical or can result in disease, especially in the context of a compromised immune system. There are eight human herpesviruses, which are divided into three subfamilies on the basis of their genomic structure (see table). These viruses are remarkably diverse in terms of their biological properties and pathogenesis, despite similarities between virus subfamilies regarding virion properties and strategies of viral replication155.

Herpesvirus virions consist of the DNA genome packaged in an icosahedral capsid that is surrounded by a layer of proteins (known as the tegument) and by an outermost lipid bilayer that contains approximately 12 viral glycoproteins. A subset of these glycoproteins mediates the binding of a virus to host receptors and the entry into host cells through fusion of the virion envelope with a cell membrane. Although the replicative strategies are similar among various herpesviruses, cell tropisms and strategies for maintaining latent infections and for evading host immune responses differ and contribute to the biological distinctions of the herpesviruses. Common to all herpesviruses is a characteristic latent phase and a lytic replicative cycle, during which the virus can be detected in the infected host. Even after immunity is established, the virus can be released persistently from mucosal tissues. The large genomes of herpesviruses encode a range of proteins that function as immune modulators that are active during the viral life cycle and that interfere with antigen presentation, with detection by the innate immune system and with other signalling pathways. Many of these immune modulators mimic the action of host proteins, thereby allowing the virus to survive and disseminate.

| Subfamily | Formal name | Common name | Disease manifestations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alphaherpesvirinae | Human herpesvirus 1 (HHV-1) | Herpes simplex virus type 1 | Mucocutaneous lesions (orofacial, genital, other), keratitis and encephalitis |

| Human herpesvirus 2 (HHV-2) | Herpes simplex virus type 2 | Mucocutaneous lesions (orofacial, genital, other), encephalitis and meningitis | |

| Human herpesvirus 3 (HHV-3) | Varicella-zoster virus | Chicken pox and zoster (shingles) | |

| Betaherpesvirinae | Human herpesvirus 5 (HHV-5) | Cytomegalovirus | Transplant- and AIDS-related disease, and intrauterine infections that cause mental retardation and hearing loss |

| Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) | HHV-6 | Roseola | |

| Human herpesvirus 7 (HHV-7) | HHV-7 | Roseola | |

| Gammaherpesvirinae | Human herpesvirus 4 (HHV-4) | Epstein-Barr virus | Infectious mononucleosis; cofactor in various malignancies (Burkitt's lymphoma, AIDS-associated lymphoma, Hodgkin's lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma) |

| Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) | Kaposi's sarcoma-associated virus | Kaposi's sarcoma, Castleman's disease and primary effusion lymphoma |

Entry of herpes simplex virus into host cells

The first encounter between a virus and its host, and an important opportunity for the immune system to resist infection and viral dissemination, is the entry of the virus into the host cell. In general, many glycoproteins in the envelope of a herpesvirus must interact with many cell-surface receptors for host-cell invasion to occur (TABLE 1). Most herpesviruses make their initial contact with the host-cell surface by binding to heparan-sulphate proteoglycans, and this increases the efficiency of virus entry. The viral ligands for heparan sulphate are glycoprotein B (gB) and usually at least one other glycoprotein. entry of the virus into the host cell requires fusion of the viral envelope with the host-cell membrane; this is mediated by the binding of the conserved glycoproteins (gB, gH and gL) and usually one or more non-conserved glycoproteins to specific cell-surface receptors10. The viral ligands that are used for binding to cell-surface entry receptors and, for some herpesviruses, the composition of the gH- and gL-containing complexes on the surface of the virion determine the host-cell receptors that are used for entry, the cell tropism of the virus and ultimately viral pathogenesis11,12.

Table 1.

Human herpesvirus glycoproteins and their cellular receptors

| Human herpesvirus |

Initial binding | Entry | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viral glycoprotein | Host molecule | Viral glycoprotein | Host receptor | ||

| HSV-1 | gB, gC | Heparan-sulphate proteoglycans | gB | PILRα |

14,16,19, 156,157 |

| gD | HVEM, nectin-1, nectin-2, 3-O-sulphotransferase-modified heparan sulphate | ||||

| HSV-2 | gB, gC | Heparan-sulphate proteoglycans | gD | HVEM, nectin-1, nectin-2, 3-O-sulphotransferase-modified heparan sulphate |

14,19, 156,157 |

| VZV | gB | Heparan-sulphate proteoglycans | Mannose-6-phosphate-containing gB,gE,gH,gI | Mannose-6-phosphate receptor |

14, 158-160, |

| gE | Insulin-degrading enzyme | ||||

| EBV | gp220 and gp350 | CD21 | gH, gL, gp42 | MHC class II, others? | 161 |

| CMV | gB, gM | Heparan-sulphate proteoglycans | gB, gH | EGFR, αvβ3-integrin | 14,162,163 |

| HHV-6 | Unknown | Heparan-sulphate proteoglycans? | gH, gL, gQ | CD46 | 14,164-166 |

| HHV-7 | gB, gp65 | Heparan-sulphate proteoglycans | Unknown | CD4 | 14,167 |

| KSHV | Unknown | Heparan-sulphate proteoglycans | gB | α3β1-integrin | 14,168,169 |

| gB, gH, gL | Cysteine transporter | ||||

| CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; gX, glycoprotein X; HHV, human herpesvirus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; HVEM, herpesvirus entry mediator; KSHV, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated virus; PILRα, paired immunoglobulin-liketype 2 receptor-α VZV,varicella-zostervirus. | |||||

Attachment and fusion

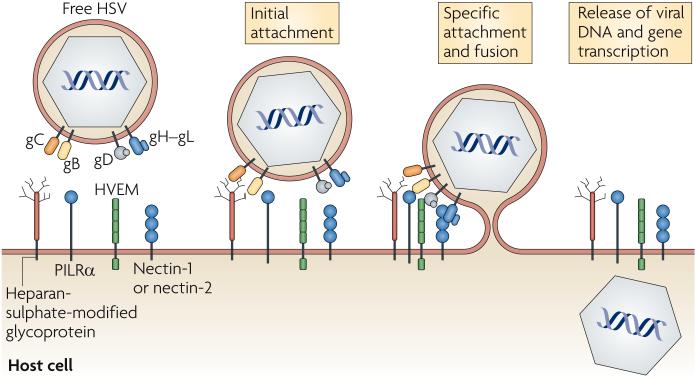

The requirement of numerous receptors and ligands for the entry of herpes simplex virus (HSV; used here when referring to both HSV-1 and HSV-2) into host cells illustrates the complexity of the viral-entry process (FIG. 1). similarly to other herpes-viruses, HSV-1 first attaches to the host cell through the interaction of gB or gC with heparan-sulphate chains on cell-surface proteoglycans (the HSV-2 ligands for heparan sulphate are gB and gG)13,14. These interactions with heparan sulphate are reversible and are not solely sufficient for viral entry; the action of four HSV glycoproteins is also required, specifically the interaction of HSV gD (which is unique to a subset of the alphaherpesviruses) and gB with a cell-surface receptor, and the participation of a gH-gL heterodimer in membrane fusion. The gD receptors include HVEM (a member of the TNFR super-family), nectin-1 and nectin-2 (also known as PVRL1 and PVRL2, respectively, and are cell-adhesion molecules that belong to the immunoglobulin superfamily), and heparan-sulphate chains that have been modified by particular 3-O-sulphotransferases15. recently, gB was shown to bind to paired immunoglobulin-like type 2 receptor-α (PILRα) and have a role in HSV entry16; this interaction seems to be independent of gB binding to heparan sulphate.

Figure 1. Herpes simplex virus entry receptors and ligands.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) contains on its surface five glycoproteins that are used for its entry into host cells, gB, gC, gD, gH and gL. gB and gC mediate the initial attachment of virus particles to heparan-sulphate moieties on host cell-surface proteoglycans. gB binding to paired immunoglobulin-like type 2 receptor-α (PILRα) and gD binding to herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM), nectin-1, nectin-2 or 3-O-sulphotransferase-modified heparan sulphate trigger membrane fusion, which is mediated by gB and the gH-gL heterodimer, and release of the viral nucleocapsid into the host-cell cytoplasm. Viral-gene transcription occurs following the release of viral DNA into the cell nucleus.

It is not yet clear how the five HSV glycoproteins (gB, gC, gD, gH and gL) mediate fusion of the viral envelope with the host-cell membrane, an event that can occur either at the cell surface or after endocytosis of the virus. It has been shown that gD can assume multiple conformations depending on whether or not it is bound to HVEM or nectin-1 (REF. 17). The binding of gD to one of its receptors is thought to trigger a change in its conformation that allows it to interact with the gH-gL heterodimer or with gB and activate their fusion activity. Although less is known about the gB-PILRα interaction, it also has a role in triggering fusion activity in some cell types.

Expression of viral-entry receptors and cell tropism

The cell-surface receptors that can mediate HSV entry are expressed by various cell types, including epithelial cells and neurons (which are the main targets for HSV infection in vivo). several lines of evidence indicate that, of the gD-binding receptors, nectin-1 is preferentially used by HSV for the infection of these cells. Accordingly, antibodies that are specific for nectin-1, but not those that are specific for HVEM, can inhibit the infection of cultured neuronal and epithelial cells by HSV18-20. Moreover, mutations in gD that specifically abrogate HVEM binding do not interfere with the infection of neuronal and epithelial cells, whereas mutations that specifically affect nectin-1 binding do21. Finally, in nectin-1- deficient mice, intravaginal infection of HSV-2 is less efficient than in wild-type mice and neurological disease is attenuated, whereas in HVEM-deficient mice HSV infection is largely unchanged. However, the role of HVEM as an entry receptor should not be ignored, as mice that are deficient in both nectin-1 and HVEM are resistant to HSV-2 infection through an intravaginal route22.

HVEM may be more important for the infection of leukocytes than for the infection of epithelial cells and neurons, as HVEM-specific antibodies partially blocked the infection of activated human T cells19, and gD mutants that can bind HVEM but not nectin-1 can still mediate the infection of Jurkat T cells21. Finally, antibodies that are specific for either HVEM or PILRα inhibited HSV infection of CD14+ monocytes, which indicates that both receptors are required for the infection of these cells16. Nevertheless, it is unclear how HSV infection of leukocytes may contribute to viral pathogenesis in vivo.

In addition to the use of HVEM by HSV as a receptor for entry into host cells, other viruses (such as feline immunodeficiency virus, rabies virus, and avian leukosis and sarcoma virus) are now known to enter cells by binding to members of the TNFR superfamily (OX40, nerve growth factor receptor (NGFR) and avian TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor (TRAILR; also known as TNFRSF10A)). These viruses can target the structurally conserved cysteine-rich domain 1 (CRD1) that is present in TNFRs23.

Activation of HSV entry receptors

Ligation of HVEM and PILRα by their cellular ligands triggers positive- and negative-signalling pathways that regulate immune effector cells. Binding of these receptors by HSV glycoproteins is also thought to induce some degree of signalling, and this could prime the cell for downstream events that are involved in viral replication and/or initiate host protective responses. signalling is not absolutely necessary for HSV entry into host cells, as deletion of the cytoplasmic domains of HVEM, PILRα or nectin-1 does not abrogate this event16,19,24. It remains to be determined whether binding of gD to HVEM or of gB to PILRα has immunomodulatory effects and how this might benefit the virus in vivo. However, the recent discovery that HVEM has many cellular ligands raises the possibility that immunomodulatory selective pressure is involved in the evolution of these viral-entry strategies.

The complex interactions between HVEM, PILRα and their ligands

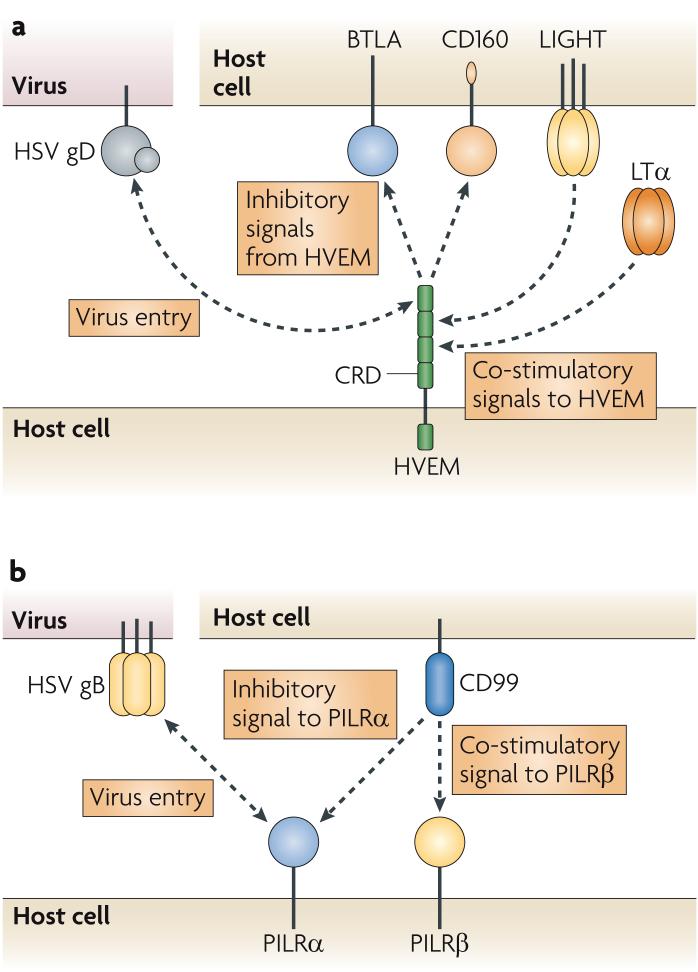

The cellular and viral ligands that interact with HVEM include the TNF superfamily members LTα and LIGHT (also known as TNFSF14), the immunoglobulin-domain-containing cell-surface receptors B and T lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA) and the recently identified CD160, and HSV gD25-28 (FIG. 2a). Activation of HVEM by LIGHT leads to co-stimulation of several cell types, including T cells and antigen-presenting cells, whereas ligation of T-cell-expressed BTLA or CD160 by HVEM results in inhibition of T-cell proliferation and effector function28-30. Although the interaction stoichiometry and the relative positions of HVEM and BTLA or CD160 on opposing membranes are not clear, the trimeric TNF-related ligands LIGHT and LTα are thought to induce HVEM trimerization, whereas HVEM and BTLA bind as heterodimers in solution31-33. Interestingly, LIGHT increases the binding of BTLA to HVEM, and there is some evidence that HVEM can interact in a ternary complex with BTLA and LIGHT34,35. These data, and the ubiquitous expression of these proteins, have led to the proposal that HVEM binds LIGHT and BTLA in a multimeric complex that contains three heterodimers of BTLA or CD160 with HVEM bound to a trimer of LIGHT molecules28,30,33,34. It is unclear whether HSV gD can participate in a ternary complex with HVEM and additional ligands and whether this complex can induce signalling. Nevertheless, the structure of HVEM bound to gD shows that these two proteins form a heterodimer, as do HVEM and BTLA30,33,36, which indicates that gD-containing complexes may exist. still, it is unclear whether such complexes are necessary for the activation of any of these proteins.

Figure 2. Co-stimulatory and inhibitory signalling by HVEM and PILRα.

a | Herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM) binds the trimeric tumour-necrosis factor (TNF) proteins lymphotoxin-α (LTα) and LIGHT through cysteine-rich domain 2 (CRD2) and CRD3 in its extracellular domain, and this leads to co-stimulatory signalling in many cell types. HVEM binds the immunoglobulin proteins B and T lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA) and CD160 through its amino (N)-terminal CRD1, and this activates inhibitory signalling in T cells. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) glycoprotein D (gD) also binds the CRD1 of HVEM using its N-terminal loop, which facilitates the entry of the virus into HVEM-expressing cells. Although the TNF and immunoglobulin ligands bind distinct regions of HVEM, gD can compete with LIGHT and BTLA for binding to HVEM. b | Paired immunoglobulin-like type 2 receptor-α (PILRα) and PILRβ are inhibitory and co-stimulatory receptors for CD99, respectively. Only PILRα binds HSV gB, which is present as a trimer on the HSV virion.

PILRα is one of a pair of inhibitory and activating receptors that are expressed by dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages, natural killer cells and nervous-system cells16,37,38. The cytoplasmic domain of PILRα contains an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif and triggers inhibitory responses, whereas the related receptor, PILRβ, interacts with an adaptor molecule that contains an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) and transduces activating signals39. The cellular ligand for both PILRα and PILRβ is the leukocyte-expressed protein CD99 (FIG. 2b), and natural killer cells that express PILRβ are activated to kill target cells that express CD99 (REF. 37). CD99 is highly expressed on activated T cells40, indicating that PILRβ and/or PILRα might regulate T-cell activation. The selective ligation of gB with the inhibitory receptor PILRα, as mentioned earlier, suggests a mechanism whereby surface-expressed gB potentially deactivates natural killer cells and prevents lysis of HSV-infected cells.

Signal transduction induced by HSV

As an early event in infection, HSV-1 induces the activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), which seems to be necessary for efficient viral replication41-43. More specifically, a purified soluble form of gD, or gD expressed by fibroblasts, was shown to induce NF-κB activation in U293 and THP-1 tumour cell lines, and this activation was decreased or inhibited by the presence of a gD-specific blocking antibody or by the expression of a mutant form of gD that cannot bind to HVEM44,45. Although these results indicate that gD is one viral factor that can activate NF-κB, gD has also been implicated in the inhibition of T-cell activation, as discussed later. At present, it is difficult to provide an explanation for these apparently contradictory observations.

In epithelial cells, HSV-1 and HSV-2 trigger inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate-mediated release of Ca2+ from endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ stores, and this is necessary for the phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase46,47. Ca2+-activated focal adhesion kinase seems to be required for the transport of viral capsids to the nuclear pore, as blocking the Ca2+ activation of this enzyme significantly inhibits the establishment of viral infection immediately after entry. Viral mutants that lack gD, gB, gH or gL can still bind to host cells, presumably through the remaining viral glycoproteins that are present in the virions, but these mutants fail to enter cells and fail to trigger the release of Ca2+ stores. Therefore, cell binding of one or more of these viral glycoproteins is not sufficient for the Ca2+ response. Downregulation of nectin-1 expression in human cervical epithelial cells using small interfering RNA prevented viral entry and the subsequent Ca2+ response. By contrast, downregulation of HVEM using the same mechanism had no effect on viral entry or on Ca2+ mobilization. However, human cervical epithelial cells may not express HVEM47. Therefore, gD binding to HVEM is presumably not responsible for Ca2+-mediated capsid transport in these cells, even though intracellular Ca2+ mobilization has been associated with HVEM signalling in monocytes in response to LIGHT48.

HVEM-mediated viral entry is probably more important in other cell types, and HVEM may engage signalling mechanisms that are different to those engaged by nectin-1. gD binding to HVEM may have an additional immunomodulatory role, as recombinant soluble gD or fibroblasts expressing gD alone could inhibit T-cell proliferation49. Furthermore, HSV-infected fibroblasts could inhibit the activation and effector functions of T cells50. Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have been isolated from skin lesions containing reactivated HSV-2, although HSV-2-specific cytotoxic T-cell recruitment to these lesions and localization at peripheral nerve endings seem to best correlate with viral clearance51-53. Mutant HSV that expressed a form of gD that cannot bind HVSM was as effective as wild-type HSV at inhibiting T-cell activity52, which suggests that other inhibitory pathways may be engaged by the virus (for example, through the interaction between gB and PILRα).

Herpesvirus mimicry of TNFR pathways

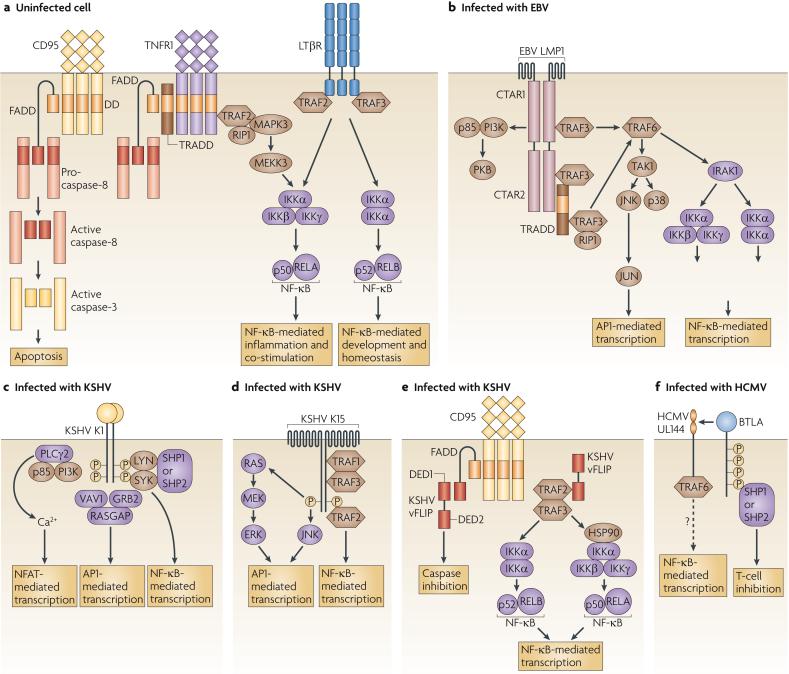

Signalling through TNFR superfamily members has diverse outcomes, including caspase-induced apoptosis in response to signalling downstream of death receptors, inflammation and co-stimulation in response to TNFR-induced canonical NF-κB activation, and the provision of developmental and homeostatic signals in response to non-canonical NF-κB activation5 (FIG. 3a). TNFR signalling pathways are commonly targeted by viruses both to prevent the infected cell from triggering apoptotic cascades and to promote the induction of survival pathways6,8,54-56. Examples of herpesvirus proteins that activate all or part of the TNFR signalling pathways include Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) LMP1 (latent membrane protein 1), Kaposi's sarcoma-associated virus (KSHV) K1, K15 and vFLIP (viral caspase-8 (FLICE)-like inhibitory protein), and CMV UL144 (FIG. 3b-f). Although the function of each of these viral gene products during infection is not completely understood, they are thought to regulate cell transformation, viral latency and immune evasion. So, these proteins induce different signalling pathways that, however, share features of ligand-independent signalling, TNFR-associated factor (TRAF) recruitment and NF-κB activation, which ultimately lead to the induction of expression of pro-survival factors and consequently the inhibition of apoptosis. Although none of these proteins has been shown to influence pathogenesis in natural human infections, it should be noted that studying them in the context of a natural infection remains a challenge.

Figure 3. Tumour-necrosis-factor-receptor-like signalling of viral proteins.

a | In general, tumour-necrosis factor (TNF) ligands initiate TNF-receptor (TNFR) signalling through ligand-induced trimerization, which leads to the oligomerization of the associated adaptor proteins. Death receptors, such as CD95, first recruit FAS-associated via death domain (FADD) directly or through the adaptor TNFR1-associated via death domain (TRADD) and then recruit caspase-8 and caspase-3, which ultimately leads to DNA cleavage and apoptosis. Non-apoptotic TNFRs that recruit TNFR-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) activate the IκB kinase-α (IKKα)-IKKβ-IKKγ complex, leading to the formation of RELA-p50 nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) heterodimers. By contrast, the TNFRs that recruit TRAF3 generally activate IKKα-IKKα complexes, leading to the degradation of p100 to p52 and the formation of RELB-p52 NF-κB heterodimers. TNFR1 can activate apoptotic cascades by associating with TRADD, and NF-κB signalling by associating with TRAF2. Lymphotoxin-β receptor (LTβR) activates both RELA- and RELB-containing NF-κB complexes through the recruitment of both TRAF2 and TRAF3. b-e | Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1), Kaposi's sarcoma-associated virus (KSHV) K15 and viral caspase-8 (FLICE)-like inhibitory protein (vFLIP) all recruit cellular TRAFs to activate NF-κB, whereas KSHV K1-mediated activation of NF-κB requires the SRC family kinases. Some of these virus-encoded proteins also activate mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Ca2+ pathways to induce the expression of activator protein 1 (AP1) and nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), leading to the transcription of many host genes that are necessary for host and virus survival. vFLIP (as well as cellular FLIP) blocks apoptosis by inhibiting the death-inducing signalling complex downstream of TNFR signalling. f | The human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) protein UL144 may have signalling activity and thereby induce the expression of NF-κB. In addition, it binds B and T lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA), which induces inhibitory signalling. CTAR, C-terminal activator region; DED, death effector domain; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; GRB2, growth-factor-receptor-bound protein 2; HSP90, heat-shock protein 90; IRAK1, interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1; JNK, JUN N-terminal kinase; MEK, MAPK/ERK kinase; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PKB, protein kinase B; PLCγ2, phospholipase Cγ2; RASGAP, RAS GTPase-activating protein; RIP1, receptor-interacting protein 1; SHP, SH2-domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase; SYK, spleen tyrosine kinase; TAK1, transforming-growth-factor-β-activated kinase 1.

EBV LMP1

LMP1 is a six-transmembrane-domain protein that is associated with lipid rafts and that oligomerizes to form a receptor complex that signals constitutively using the TNFR signalling apparatus57-60. The cytoplasmic domain of LMP1 contains a binding site with a TRAF recruitment motif (known as carboxy (C)-terminal activator region 1 (CTAR1)) and a TNFR-associated via death domain (TRADD)- and receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1)-binding site (known as CTAR2). CTAR1 and CTAR2 can recruit several TRAF molecules directly and indirectly, respectively; of these TRAF molecules, TRAF3 is specifically required for the activation of the JUN N-terminal kinase (JNK) and activator protein 1 (AP1) pathway, for the activation of the NF-κB components RELA and RELB and for the production of immunoglobulins by B cells61-63. By driving these signalling pathways, LMP1 functions as a constitutively active mimic of the TNFR family member CD40, resulting in the activation of survival pathways and in the provision of proliferative signals for B-cell transformation. EBV-transformed B-cell lymphomas that express LMP1 have constitutively active NF-κB, protein kinase B (PKB; also known as AKT) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), and inhibition of the constitutive activation of these molecules using specific inhibitors against NF-κB, PKB and STAT3 restrains B-cell lymphoma growth and survival64. It is unclear whether LMP1 activates the Janus kinase (JAK)-STAT signalling pathway directly or indirectly following the transcription of LMP1-responsive genes such as interleukin-10 (IL10)59,65. LMP1 also activates PKB and numerous other signalling pathways, and together with other EBV proteins that are expressed during viral latency, LMP1 promotes the differentiation of infected naive B cells into long-lived memory B cells, in which the virus remains in a latent state66.

LMP1-mediated activation of the transcription factors AP1, RELA and RELB is known to involve the coordination of a large number of adaptor molecules and signalling pathways. TRAF6, IL-1R-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) and IκB kinase-β (IKKβ) are all essential for LMP1-mediated phosphorylation and nuclear localization of the NF-κB RELA-p50 heterodimers, which trigger the canonical NF-κB pathway59,67-70. The recruitment of TRAF3 to the CTAR1 of LMP1 also activates NF-κB-inducing kinase and IKKα to activate the processing of the NF-κB p100 subunit to p52, which allows the formation of RELB-p52 heterodimers and, consequently, the activation of the non-canonical NF-κB pathway71. In mouse embryonic fibroblasts, but not in B cells, LMP1 activates AP1 through the direct association of TRAF1 with its CTAR1 or through the indirect association of TRAF2 with TRADD through CTAR2 (REFS 72,73). LMP1-mediated AP1 activation also requires the activation of TRAF6-dependent TGFβ-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), and the downstream mitogen-activated protein kinases JNK and p38 (REFS 74,75). Finally, LMP1-mediated activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway that leads to the activation of PKB requires the CTAR1 of LMP1, which indicates that TRAF proteins are involved in this pathway76.

KSHV K1

The KSHV protein K1 self-associates through its single extracellular immunoglobulin domain to initiate ligand-independent constitutive signalling77. The cytoplasmic domain of K1 contains an ITAM, which is phosphorylated, possibly by spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK), and functions in the recruitment of LYN, SYK, phospholipase Cγ 2, the p85 subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase, VAV1, SRC homology 2 (SH2)-domain-containing phosphatase 1 (SHP1), SHP2, RAS GTPase-activating protein and growth-factor-receptor-bound protein 2 (REFS 78,79). These proteins can activate several transcription factors, including AP1, Ca2+-signal-driven nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) and PKB-signal-driven forkhead-box-containing proteins, which are all involved in preventing apoptosis59,80. In addition, K1 activates NF-κB in B cells in a process that requires the K1 cytoplasmic ITAM and LYN81. Together these signalling pathways ensure the survival of infected cells and promote the expression of many host genes, including vascular-endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in vitro. In a mouse model of infection using a recombinant variant of mouse gammaherpesvirus 68 that expresses KSHV K1, expression of K1 was shown to increase latent viral load, tumour formation and the inflammatory response82,83.

KSHV K15

The KSHV protein K15 is a multi-transmembrane-domain protein that associates with lipid rafts and initiates constitutive signalling through SH2- and SH3-binding motifs in its cytoplasmic domain59,84. Although none of these domains is required for the binding of SRC family kinases in vitro, the C-terminal tyrosine-containing motif is required for SRC-kinase-mediated phosphorylation of K15. Once phosphorylated, K15 activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 (ERK2) through RAS and MAPK/ERK kinase 1 (MEK1) or through MEK2 and the JNK pathway, which together lead to AP1 activation. K15 also activates NF-κB, although the mechanism of activation is unclear. However, K15 binds TRAF1, TRAF2 and TRAF3 in vitro, and the C-terminal tyrosine of K15 is required for TRAF2 binding and NF-κB activation59,84. K15 signalling induces the expression of many cytokines and chemokines, including IL-6 and IL-8, and, as with K1, this leads to VEGF expression in vitro and could contribute to angiogenesis in vivo85. Therefore, KSHV triggers many signalling pathways through K1 and K15, which may act together with other KSHV proteins, including the viral homologues of IL-6 and CD200, to establish a state that promotes tumour formation in patients with Kaposi's sarcoma86.

CMV UL144

The UL144 protein of human CMV (HCMV) is encoded within the (UL)/b′ region of the virus genome and was originally described as a homologue of HVEM87,88. Although the (UL)/b′ region is not necessary for the replication of HCMV in certain cell types in vitro and is absent from many laboratory strains of the virus, it contains most of the viral immunomodulatory genes and is required for the virus to evade host immune responses89. UL144 binds the HVEM ligand BTLA30,35 but does not interact with any TNF-related ligands87,90, presumably because UL144 has only two CRDs. Exposure of T cells to HVEM-Fc or UL144-Fc fusion proteins inhibited T-cell proliferation, possibly through binding of the fusion proteins to T-cell-expressed BTLA27,35,91,92. Interestingly, UL144 seems to have a stronger inhibitory activity than HVEM despite having lower affinity for BTLA, probably owing to the selective binding of UL144 to BTLA and not to the TNF ligands LIGHT or LTα (REF. 35). As UL144 competes with HVEM for binding BTLA35,93, HVEM and UL144 may bind and activate BTLA similarly, and HCMV may use UL144 to inhibit T-cell responses through BTLA.

Although it was previously reported that UL144 cannot induce apoptosis or activate NF-κB87, a recent report has shown that UL144 recruits TRAF6 and constitutively activates NF-κB90. It is unclear whether UL144 binds to TRAF6 directly or indirectly through an intermediate protein, as the cytoplasmic domain of UL144 does not contain a canonical TRAF-binding site. The cytoplasmic domain of UL144 is conserved between strains of HCMV, in contrast to the significant sequence variability in the extracellular domain88, which suggests that the cytoplasmic domain has a role in signalling. Interestingly, both UL144 and LMP1 induce the expression of CC-chemokine ligand 22 (CCL22), which implies that this chemokine has an important role during infection with herpesviruses of different subfamilies90,94. However, more studies need to be carried out to determine which signalling molecules act downstream of UL144, the relevance of virus-induced NF-κB activation, and how UL144 interacts with BTLA (in cis or in trans) during infection.

Although the impact of UL144 on immune function during HCMV infection in lymphoid organs and in the periphery is unclear (owing to technical difficulties in assessing UL144 expression in various human tissues that are targeted by the virus), a recent report has identified HVEM-BTLA co-signalling as an important pathway for regulating the homeostasis of splenic CD8α- and CD8α+ DC subsets, which preferentially activate CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, respectively95,96. Importantly, mice that are deficient in either HVEM or BTLA have increased numbers of CD8α- DCs, whereas mice that are deficient in LTα, LTβ or LTβR have decreased numbers of CD8α- DCs. In addition, mice that lack all three components (HVEM, LIGHT and LTβ) show an additional decrease in the number of the CD8α+ DCs. Taken together, these observations suggest that these TNF ligands and receptors regulate DC homeostasis at many levels. CMV infects DCs and inhibits their maturation and effector function by decreasing their expression of MHC molecules, co-stimulatory molecules and cytokines, which leads to the inhibition of T-cell activation97,98. It is also possible that CMV regulates DC function by direct UL144-mediated activation of DC-expressed BTLA, which results in inhibition of DC function. It is unclear whether similar DC subsets are present in humans, and it remains to be determined whether UL144 influences the frequencies or activation of these cells in vivo.

Herpesvirus subversion of death receptors

Expression of death receptors and ligands

The death receptors CD95 (also known as FAS), TRAILR1, TRAILR2 and TNFR1 (also known as TNFRSF1A) are crucial for the induction of apoptosis of infected cells99,100. Not surprisingly therefore, many viruses, including herpesviruses, regulate the expression of death receptors. The EBV protein BZLF1 inhibits the expression of TNF-induced genes and decreases TNFR1 promoter activity, which results in decreased TNFR1 transcription during lytic reactivation of the virus101. CMV also reduces the cell-surface expression of TNFR1 by inducing the relocalization of TNFR1 from the cell surface to the trans-Golgi network102. By contrast, herpesviruses can also increase the expression of death receptors, possibly to allow for cytotoxic T-cell-mediated clearance of infected cells103,104: CMV induces TRAILR expression in vitro and EBV induces CD95 expression through signalling downstream of LMP1 and through activation of NF-κB. Moreover, type I IFNs that are produced in response to CMV infection cause the induction of TRAIL expression by DCs105, and the CMV immediate-early 2 (IE2) gene product has been shown to induce the expression of CD95 ligand by human retinal pigment epithelial cells106. These observations indicate that increased expression of death-receptor ligands might be used by the virus to induce fratricide of uninfected, virus-specific effector T cells, thereby limiting detection by the immune system8.

Regulation of death-receptor signalling

The apoptotic signalling cascade that is induced by several members of the TNFR superfamily is regulated at many levels and has many steps that viruses can exploit6,8. In addition to the regulation of the expression of the death receptors and ligands themselves, a common mechanism that is used by herpesviruses to block apoptosis is the induction of expression of cellular FLIP or vFLIP107,108. FLIP proteins bind to FAS-associated via death domain (FADD), which prevents the oligomerization of pro-caspase-8 with the death-induced signalling complex of death receptors, and inhibits subsequent apoptosis107,109,110. EBV infection protects BJAB cells from CD95- and TRAIL-induced apoptosis, partly owing to the ability of LMP1 to induce the expression of cellular FLIP111. similarly, the CMV protein IE2 induces the expression of cellular FLIP in human retinal pigment epithelial cells, and this also contributes to protection from CD95- and TRAIL-mediated apoptosis112. HSV induces the expression of both cellular FLIP and cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 2 (cIAP2) following gD-mediated activation of NF-κB44. HCMV and MCMV also encode proteins (UL36 and M36) that prevent caspase-8 activation by binding to pro-caspase-8, similarly to FLIP, although these viral proteins share no sequence homology with FLIP113,114. Another protein encoded by MCMV (M45) blocks TNF-induced apoptosis in a manner that is independent of caspase activation and instead occurs through the binding of M45 to the TNFR adaptor protein RIP1 (REF. 115). Taken together, these observations suggest that herpesviruses have evolved numerous mechanisms to subvert death-receptor-induced apoptosis.

Recently, several studies have been published that examine the function of KSHV vFLIP beyond its known role as an inhibitor of apoptotic cascades. KSHV vFLIP protects the human myeloid leukaemia cell line TF-1 from growth-factor-withdrawal-induced apoptosis through the induction of NF-κB activation116. NF-κB activation by KSHV vFLIP in primary effusion lymphoma requires direct binding by TRAF2 and TRAF3, and correlates with the binding of IKKγ (REF. 117). vFLIP recruits the IKKα-IKKβ-IKKγ complex, in addition to heat-shock protein 90, resulting in the activation and nuclear translocation of RELA-p50 heterodimers118. vFLIP binds p100 directly, and this activates IKKα-mediated ubiquitylation and processing of p100 to p52 independently of RIP1 and NF-κB-inducing kinase119. vFLIP signalling induces the transcription of many genes, including those that encode the anti-apoptotic proteins cellular FLIP, cIAP1 and cIAP2, and the cytokines and chemokines IL-6, IL-8 and CXC-chemokine ligand 3 (CXCL3)120,121. Interestingly, the NF-κB-activating function of vFLIP might be more relevant than its anti-apoptotic function, as vFLIP-transgenic mice have normal CD95-mediated apoptosis of thymocytes, but increased DNA binding by NF-κB in lymphoid tissues122.

As previously mentioned, KSV K1 activates the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway to protect cells from apoptosis and inhibits CD95, but not TRAILR, signalling123. EBV protects cells from CD95-induced apoptosis through a small non-polyadenylated RNA that binds IFN-inducible dsRNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) and prevents cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase, and CMV RNA β2.7 stabilizes the mitochondrial membrane, thereby preventing chemically induced apoptosis124,125. Together, these examples show that herpesviruses have evolved many different mechanisms to interfere with death-receptor signalling and prevent host-cell apoptosis, thereby allowing for the eventual spread of the virus.

Regulation of herpesviruses by TNFR pathways

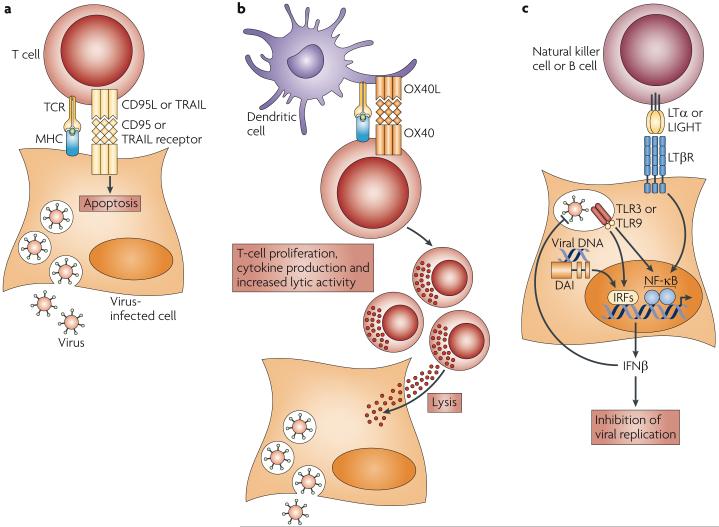

The TNFR superfamily proteins control numerous important pathways that limit pathogen infection through the induction of inflammatory responses and the direct lysis of infected cells (FIGS 3a,4a). Recent studies indicate that members of the TNFR superfamily might also have important roles in limiting virus infection by augmenting T-cell co-stimulation (for example, through OX40-mediated co-stimulation) and by regulating IFN production (for example, through LTβR signalling). Indeed, OX40 enhances immunity to infection with MCMV, and LTβR signalling limits MCMV replication through the production of IFN and helps to maintain splenic architecture during viral infection.

Figure 4. The role of tumour-necrosis factor receptors in the control of viral replication.

a | Death receptors, such as CD95 and tumour-necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) receptor, mediate signalling in virus-infected cells to induce apoptosis and viral clearance. b | Co-stimulatory TNF receptors (TNFRs), such as OX40, that are present on cytotoxic T lymphocytes induce signalling to promote the proliferation, cytokine production and lytic activity of virus-specific effector T-cell populations, which reduces viral load. c | Lymphotoxin-β receptor (LTβR) signalling in cytomegalovirus-infected cells induces interferon-β (IFNβ) expression, which limits viral replication and induces the antiviral state in other cells. CD95L, CD95 ligand; DAI, DNA-dependent activator of IRFs; IRF, IFN-regulatory factor; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; OX40L, OX40 ligand; TCR, T-cell receptor; TLR, Toll-like receptor.

Control of viral transmission by OX40

Previously, OX40 was shown to contribute to antiviral immunity by inducing T-cell expansion and effector responses through co-stimulatory signalling126-128. OX40 not only synergizes with signals from other co-stimulatory receptors to induce naive T-cell stimulation, but also signals to increase effector T-cell proliferation, cytolytic activity and cytokine production129,130. During HSV-induced herpesvirus stromal keratitis in mice, OX40 is expressed by corneal CD4+ T cells, although OX40 ligand does not seem to be expressed by the tissue-associated antigen-presenting cells131. OX40 stimulation of CD4+ T cells increases the clonal expansion and cytolytic activity of EBV-specific CD8+ T cells in vitro132. MCMV stimulates the proliferation of virus-specific CD8+ T cells, the numbers of which change during the acute and persistent phases of infection133. Notably, OX40-deficient mice have decreased CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses in the persistent phase of viral infection, whereas T-cell responses in the acute phase are equivalent to those of wild-type mice. Together, these data indicate that OX40 signalling might be important in secondary responses to herpesviruses, and that CD4+ T cells receive OX40 signals to provide help for CD8+ T-cell expansion (FIG. 3b). MCMV replicates in the salivary glands and is persistently shed from this location in C57Bl/6 mice; similarly, herpesviruses can be readily detected in human saliva. A recent report showed that during MCMV infection of salivary glands, the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10 is expressed by a significant percentage of salivary-gland-infiltrating CD4+ T cells. OX40 ligation on these T cells reduced IL-10 expression and resulted in viral clearance from the salivary glands (but not from visceral organs), which indicates that OX40 activation can directly inhibit IL-10-mediated immune suppression, and that both the IL-10 and OX40 signalling pathways can be modulated to alter the course of viral dissemination134. Interestingly, several herpesviruses, including HCMV and EBV, encode homologues of IL-10. These homologues are thought to inhibit or skew effector T-cell responses or to promote B-cell survival, although the contribution of these viral genes to the pathogenesis of human disease is yet to be shown135,136.

Cooperative relationship between LTβR, IFNβ and CMV

At present, it is not clear which innate immune receptor is responsible for detecting herpesvirus infection. Moreover, receptor use might depend on cell type. In conventional and plasmacytoid DCs, Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) might be used by MCMV, and this probably leads to the activation of IFN-regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), IRF7 and IRF9 (REFS 137-139). Recent reports indicate that DAI (DNA-dependent activator of IRFs; also known as ZBP1) might be a cytosolic sensor of HSV DNA and that a dominant-negative mutation of TLR3 increases susceptibility to HSV-induced encephalitis in humans, which suggests that multiple sensors are used to detect herpesvirus in host cells140,141.

An important outcome of virus detection is the production of type I and type II IFNs, which inhibit virus replication. Herpesviruses can block both IFN production and their downstream effects; for example, HCMV blocks the induction of IFN production and triggers cytopathic effects in fibroblasts in vitro, an effect that is countered by the TNF superfamily members LTαβ and LIGHT142. Blockade of HCMV-induced cytopathology depends on IFNβ production, and this requires both LTβR signalling through NF-κB and HCMV infection in IFN-producing cells. Lack of LTβR signalling in mice that had been infected with MCMV resulted in uncontrolled infection and lethality143, and defective IFNβ production was linked to a blockade of LTβR signalling in stromal cells (the site of primary infection) (FIG. 4c). The LTβR pathway regulates the early TLR-independent type I IFN response in the spleen, which is the main source of serum IFN during the first few hours after infection144. In mice this LTβR-induced early IFNβ production was recently shown to be activated by LTαβ that is produced by naive B cells, and in humans IL-2-activated natural killer cells also express high levels of cell-surface LTαβ and can activate LTβR signalling to induce IFNβ production by CMV-infected fibroblasts143,145. Type I IFNs and IFNγ have crucial roles in establishing and maintaining the latency of herpesviruses146,147, and the cooperation of LTβR and IFNβ may be one mechanism by which latency is initiated.

Another way in which MCMV manipulates the LTβR pathway is by influencing the organization of the splenic microarchitecture. LTβR signalling is required for the formation and maintenance of the microarchitecture of lymphoid organs, in part through the regulation of the tissue-organizing chemokines CCL19, CCL21 and CXCL13. B-cell-expressed LTαβ has an important role in the expression of these stromal chemokines. MCMV infection disrupts the splenic architecture 3-4 days after infection, specifically through a decrease in CCL21 protein levels that is caused by a loss of Ccl21 mRNA148. As a result, T cells do not properly localize in the splenic white pulp. However, T-cell localization to the splenic white pulp could be reinstated through enforced LTβR signalling during infection. This virus-induced dysregulated homeostasis is transient, as the expression of CCL21 is restored following viral clearance at 7-10 days after infection. This transient remodelling of the host environment may provide a selective advantage for the virus over host adaptive immune responses.

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), which is a small RNA virus of the arenavirus family and is often used as a model virus infection in mice, is associated with disorganization of lymphoid tissue. Late after infection, when the CD8+ T-cell response is reaching its peak, the expression of all of the tissue-organizing chemokines is lost149,150. The broad loss of chemokine production results in poor immune responses to other pathogens and is due to damage to the stroma caused by cytotoxic-T-cell-mediated clearance of the virus, rather than by a virus-mediated cytopathic mechanism. So, LCMV infection induces immune pathology, whereas the strategies used by herpesviruses, such as CMV, that target homeostatic processes seem to create a niche for viral persistence and latency.

Concluding remarks

From the initial point of entry of herpesviruses into host cells to the induction of downstream effectors, these viruses target multiple components of the TNF signalling pathways. The HVEM-BTLA pathway stands out as a common target of both alphaherpesviruses and betaherpesviruses: the envelope gD of HSV mimics BTLA binding, whereas UL144 of HCMV and HVEM are orthologues. HSV and HCMV diverged a long time ago, but retained specific but distinct mechanisms for targeting the HVEM-BTLA pathway. The findings that herpesviruses in evolutionarily distant vertebrates encode HVEM-like molecules151,152 (J.R.S. and C.F.W., unpublished observations) and that BTLA is present in many forms in these host species153, and therefore probably represents an ancient inhibitory pathway, support the idea that the HVEM-BTLA pathway exerts an important selective pressure that influences pathogen evolution. The discovery that diverse viral pathogens, such as equine infectious anaemia virus (a lentivirus), target the host-specific equivalent of HVEM to enter host cells154 suggests that HVEM binding confers some benefit to these pathogens.

The important role of HVEM in regulating host immune-cell functions might also explain why targeting this molecule would benefit the virus. This is supported by the finding that activation of inhibitory signalling through BTLA by the UL144 protein of HCMV modulates immune responsiveness. The dual advantage of targeting a receptor for both entry and immunomodulation may act as the key selective pressure to retain and evolve these viral-entry strategies. Indeed, other immunoregulatory TNFRs, such as OX40, TRAILR and NGFR, are also used by diverse pathogens to enter host cells23. A clear understanding of the entry mechanisms that are used by viruses might therefore provide clues to finding new strategies for modulating undesired immune responses in the clinical setting.

Acknowledgements

We apologize to all our colleagues whose work could not be cited because of space limitations.

Footnotes

Latent phase A phase of a virus life cycle that is characterized by the absence of most or all viral-gene transcription despite the presence of the viral genome in host cells.

Lytic replicative cycle A phase of a virus life cycle that is characterized by active viral-gene transcription and viral-particle production and that commonly results in cell death.

Viral glycoprotein A glycoprotein that is found in the outer envelope of viruses. Of the 12 glycoproteins that are found in the outer envelope of herpesviruses, gB, gH and gL are the most highly conserved and are thought to be important for virus–host-cell membrane fusion.

Heparan sulphate A ubiquitously expressed glycosaminoglycan found on most proteoglycans.

Most herpesviruses target and use heparan sulphate as a receptor for initial attachment to host cells.

Cysteine-rich domain (CRD). A protein domain that is present in several copies in most tumour-necrosis factor receptors (TNFRs) and that contains up to six cysteine residues, which form up to three disulphide bonds. CRDs are named according to their position in TNFRs and typically CRD2 and CRD3 are required for binding of the receptors to members of the TNF superfamily.

Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM). A short peptide motif (Ile/Val/Leu/Ser-X-Tyr-X-X-Leu/Val; in which X denotes any amino acid) that is present in the cytoplasmic domain of inhibitory receptors. When the tyrosine residue is phosphorylated, ITIMs recruit lipid or tyrosine phosphatases that mediate the inhibitory function of these receptors.

Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif A structural motif containing tyrosine residues, which is found in the cytoplasmic tails of several signalling molecules. The motif has the form Tyr-X-X-(Leu/Ile), in which X denotes any amino acid, and the tyrosine is a target for phosphorylation by SRC tyrosine kinases and subsequent binding of proteins containing SRC-homology 2 domains.

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). A family of transcription factors (including NF-κB1 (also known as p50), NF-κB2 (also known as p52), cREL, RELA and RELB) that is important for pro-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic responses and for the development of lymphoid tissues. Each of these responses is mediated by canonical and non-canonical signalling pathways.

Death receptor A cell-surface receptor that can mediate cell death following ligand-induced trimerization. The best-studied members of the death-receptor family include tumour-necrosis factor (TNF) receptor 1, CD95 and two receptors for TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAILR1 and TRAILR2).

Lipid raft A cholesterol- and glycosphingolipid-rich region of the plasma membrane that provides ordered structure to the lipid bilayer and can include or exclude specific signalling molecules and complexes.

Activator protein 1 A transcription factor complex composed of a heterodimer of JUN and FOS subunits that is necessary for the induction of interleukin-2 transcription in T cells. JUN and FOS subunits are members of a family of leucine-zipper-containing proteins that are induced following activation of extracellular-signal-regulated kinase and JUN N-terminal kinase.

Mitogen-activated protein kinase A family of serine/threonine kinases that are activated by various mitogenic stimuli and lead to the activation of extra-cellular-signal-regulated kinase, JUN N-terminal kinase or p38.

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K). A lipid kinase that generates phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate, which can be bound by pleckstrinhomology-domain-containing proteins, such as protein kinase B. PI3K activation is often associated with survival signals and the activity of anti-apoptotic proteins.

SRC family kinases A group of structurally related cytoplasmic and membrane-associated enzymes that is named after its prototypical member, SRC. In haematopoietic cells, SRC kinases are the first protein tyrosine kinases to become activated after stimulation through the immunoreceptor. They phosphorylate ITAMs of the immunoreceptors, thereby providing binding sites for SRC homology 2 (SH2)-domain-containing molecules, such as SYK.

Fratricide A form of cell killing in which one of a group of similar cells kills another member or members of the group.

References

- 1.McGeoch DJ, Rixon FJ, Davison AJ. Topics in herpesvirus genomics and evolution. Virus Res. 2006;117:90–104. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.French AR, et al. Escape of mutant double-stranded DNA virus from innate immune control. Immunity. 2004;20:747–756. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glenney GW, Wiens GD. Early diversification of the TNF superfamily in teleosts: genomic characterization and expression analysis. J. Immunol. 2007;178:7955–7973. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bridgham JT, Wilder JA, Hollocher H, Johnson AL. All in the family: evolutionary and functional relationships among death receptors. Cell. Death Differ. 2003;10:19–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ware CF. Network communications: lymphotoxins, LIGHT, and TNF. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2005;23:787–819. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahman MM, McFadden G. Modulation of tumor necrosis factor by microbial pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e4. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lichtenstein DL, Toth K, Doronin K, Tollefson AE, Wold WS. Functions and mechanisms of action of the adenovirus E3 proteins. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2004;23:75–111. doi: 10.1080/08830180490265556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benedict CA, Banks TA, Ware CF. Death and survival: viral regulation of TNF signaling pathways. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2003;15:59–65. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Upton C, Macen J, Schreiber M, McFadden G. Myxoma virus expresses a secreted protein with homology to the tumor necrosis factor receptor gene family that contributes to viral virulence. Virology. 1991;184:370–382. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90853-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spear PG, Longnecker R. Herpesvirus entry: an update. J. Virol. 2003;77:10179–10185. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10179-10185.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X, Kenyon WJ, Li Q, Mullberg J, Hutt-Fletcher LM. Epstein-Barr virus uses different complexes of glycoproteins gH and gL to infect B lymphocytes and epithelial cells. J. Virol. 1998;72:5552–5558. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5552-5558.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang D, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus virion protein complex required for epithelial and endothelial cell tropism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci USA. 2005;102:18153–18158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509201102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adamiak B, Ekblad M, Bergstrom T, Ferro V, Trybala E. Herpes simplex virus type 2 glycoprotein G is targeted by the sulfated oligo- and polysaccharide inhibitors of virus attachment to cells. J. Virol. 2007;81:13424–13434. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01528-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shukla D, Spear PG. Herpesviruses and heparan sulfate: an intimate relationship in aid of viral entry. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:503–510. doi: 10.1172/JCI13799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spear PG. Herpes simplex virus: receptors and ligands for cell entry. Cell. Microbiol. 2004;6:401–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Satoh T, et al. PILRα is a herpes simplex virus-1 entry co-receptor that associates with glycoprotein B. Cell. 2008;132:935–944. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This recent paper indicates that PILRα is a new entry factor for HSV-1 and shows that the viral glycoprotein gB can also mediate specific viral attachment to host cells.

- 17.Krummenacher C, et al. Structure of unliganded HSV gD reveals a mechanism for receptor-mediated activation of virus entry. EMBO J. 2005;24:4144–4153. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cocchi F, Menotti L, Mirandola P, Lopez M, Campadelli-Fiume G. The ectodomain of a novel member of the immunoglobulin subfamily related to the poliovirus receptor has the attributes of a bona fide receptor for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in human cells. J. Virol. 1998;72:9992–10002. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9992-10002.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montgomery RI, Warner MS, Lum BJ, Spear PG. Herpes simplex virus-1 entry into cells mediated by a novel member of the TNF/NGF receptor family. Cell. 1996;87:427–436. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81363-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This report identifies HVEM as the entry receptor for HSV-1.

- 20.Simpson SA, et al. Nectin-1/HveC mediates herpes simplex virus type 1 entry into primary human sensory neurons and fibroblasts. J. Neurovirol. 2005;11:208–218. doi: 10.1080/13550280590924214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manoj S, Jogger CR, Myscofski D, Yoon M, Spear PG. Mutations in herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D that prevent cell entry via nectins and alter cell tropism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12414–12421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404211101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor JM, et al. Alternative entry receptors for herpes simplex virus and their roles in disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This recent report is the first to show the specific contributions of each HSV-2 entry receptor in vivo, indicating that although either HVEM or nectin-1 can mediate infection, nectin-1 is mainly responsible for the formation of external lesions and neuronal infection.

- 23.Kinkade A, Ware CF. The DARC conspiracy — virus invasion tactics. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subramanian RP, Dunn JE, Geraghty RJ. The nectin-1α transmembrane domain, but not the cytoplasmic tail, influences cell fusion induced by HSV-1 glycoproteins. Virology. 2005;339:176–191. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whitbeck JC, et al. Glycoprotein D of herpes simplex virus (HSV) binds directly to HVEM, a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily and a mediator of HSV entry. J. Virol. 1997;71:6083–6093. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6083-6093.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mauri DN, et al. LIGHT, a new member of the TNF superfamily, and lymphotoxin α are ligands for herpesvirus entry mediator. Immunity. 1998;8:21–30. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80455-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sedy JR, et al. B and T lymphocyte attenuator regulates T cell activation through interaction with herpesvirus entry mediator. Nature Immunol. 2005;6:90–98. doi: 10.1038/ni1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai G, et al. CD160 inhibits activation of human CD4+ T cells through interaction with herpesvirus entry mediator. Nature Immunol. 2008;9:176–185. doi: 10.1038/ni1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider K, Potter KG, Ware CF. Lymphotoxin and LIGHT signaling pathways and target genes. Immunol. Rev. 2004;202:49–66. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy KM, Nelson CA, Sedy JR. Balancing co-stimulation and inhibition with BTLA and HVEM. Nature Rev. Immunol. 2006;6:671–681. doi: 10.1038/nri1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Locksley RM, Killeen N, Lenardo MJ. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: integrating mammalian biology. Cell. 2001;104:487–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bodmer JL, Schneider P, Tschopp J. The molecular architecture of the TNF superfamily. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002;27:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Compaan DM, et al. Attenuating lymphocyte activity: the crystal structure of the BTLA-HVEM complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:39553–39561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507629200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonzalez LC, et al. A coreceptor interaction between the CD28 and TNF receptor family members B and T lymphocyte attenuator and herpesvirus entry mediator. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:1116–1121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409071102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study, together with reference 27, identifies BTLA as the natural ligand for HVEM and shows that HVEM ligation of T-cell-expressed BTLA results in inhibition of T-cell activation.

- 35.Cheung TC, et al. Evolutionarily divergent herpesviruses modulate T cell activation by targeting the herpesvirus entry mediator cosignaling pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:13218–13223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506172102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study, the authors show that the CMV homologue of HVEM UL144 selectively interacts with the HVEM ligand BTLA and that UL144 can inhibit T-cell responses.

- 36.Carfi A, et al. Herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D bound to the human receptor HveA. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:169–179. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiratori I, Ogasawara K, Saito T, Lanier LL, Arase H. Activation of natural killer cells and dendritic cells upon recognition of a novel CD99-like ligand by paired immunoglobulin-like type 2 receptor. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:525–533. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fournier N, et al. FDF03, a novel inhibitory receptor of the immunoglobulin superfamily, is expressed by human dendritic and myeloid cells. J. Immunol. 2000;165:1197–1209. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mousseau DD, Banville D, L'Abbe D, Bouchard P, Shen SH. PILRα, a novel immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif-bearing protein, recruits SHP-1 upon tyrosine phosphorylation and is paired with the truncated counterpart PILRβ. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:4467–4474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park SH, et al. Rapid divergency of rodent CD99 orthologs: implications for the evolution of the pseudoautosomal region. Gene. 2005;353:177–188. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patel A, et al. Herpes simplex type 1 induction of persistent NF-κB nuclear translocation increases the efficiency of virus replication. Virology. 1998;247:212–222. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amici C, et al. Herpes simplex virus disrupts NF-κB regulation by blocking its recruitment on the IκBα promoter and directing the factor on viral genes. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:7110–7117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512366200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taddeo B, Zhang W, Lakeman F, Roizman B. Cells lacking NF-κB or in which NF-κB is not activated vary with respect to ability to sustain herpes simplex virus 1 replication and are not susceptible to apoptosis induced by a replication-incompetent mutant virus. J. Virol. 2004;78:11615–11621. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.11615-11621.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Medici MA, et al. Protection by herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D against Fas-mediated apoptosis: role of nuclear factor κB. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:36059–36067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306198200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sciortino MT, et al. Signaling pathway used by HSV-1 to induce NF-κB activation: possible role of herpes virus entry receptor A. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2007;1096:89–96. doi: 10.1196/annals.1397.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheshenko N, Liu W, Satlin LM, Herold BC. Focal adhesion kinase plays a pivotal role in herpes simplex virus entry. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:31116–31125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503518200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheshenko N, Liu W, Satlin LM, Herold BC. Multiple receptor interactions trigger release of membrane and intracellular calcium stores critical for herpes simplex virus entry. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:3119–3130. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-01-0062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heo SK, et al. HVEM signaling in monocytes is mediated by intracellular calcium mobilization. J. Immunol. 2007;179:6305–6310. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.6305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.La S, Kim J, Kwon BS, Kwon B. Herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein D inhibits T-cell proliferation. Mol. Cells. 2002;14:398–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sloan DD, et al. Inhibition of TCR signaling by herpes simplex virus. J. Immunol. 2006;176:1825–1833. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koelle DM, et al. Antigenic specificities of human CD4+ T-cell clones recovered from recurrent genital herpes simplex virus type 2 lesions. J. Virol. 1994;68:2803–2810. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2803-2810.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koelle DM, et al. Clearance of HSV-2 from recurrent genital lesions correlates with infiltration of HSV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:1500–1508. doi: 10.1172/JCI1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu J, et al. Virus-specific CD8+ T cells accumulate near sensory nerve endings in genital skin during subclinical HSV-2 reactivation. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:595–603. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alcami A. Viral mimicry of cytokines, chemokines and their receptors. Nature Rev. Immunol. 2003;3:36–50. doi: 10.1038/nri980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seet BT, et al. Poxviruses and immune evasion. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003;21:377–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stanford MM, Werden SJ, McFadden G. Myxoma virus in the European rabbit: interactions between the virus and its susceptible host. Vet. Res. 2007;38:299–318. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2006054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coffin WF, 3rd, Geiger TR, Martin JM. Transmembrane domains 1 and 2 of the latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus contain a lipid raft targeting signal and play a critical role in cytostasis. J. Virol. 2003;77:3749–3758. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.6.3749-3758.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lam N, Sugden B. LMP1, a viral relative of the TNF receptor family, signals principally from intracellular compartments. EMBO J. 2003;22:3027–3038. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brinkmann MM, Schulz TF. Regulation of intracellular signalling by the terminal membrane proteins of members of the gammaherpesvirinae. J. Gen. Virol. 2006;87:1047–1074. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81598-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Soni V, Cahir-McFarland E, Kieff E. LMP1 TRAFficking activates growth and survival pathways. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2007;597:173–187. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-70630-6_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xie P, Hostager BS, Bishop GA. Requirement for TRAF3 in signaling by LMP1 but not CD40 in B lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:661–671. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xie P, Bishop GA. Roles of TNF receptor-associated factor 3 in signaling to B lymphocytes by carboxyl-terminal activating regions 1 and 2 of the EBV-encoded oncoprotein latent membrane protein 1. J. Immunol. 2004;173:5546–5555. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu S, et al. LMP1 protein from the Epstein-Barr virus is a structural CD40 decoy in B lymphocytes for binding to TRAF3. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:33620–33626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502511200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shair KH, et al. EBV latent membrane protein 1 activates Akt, NFκB, and Stat3 in B cell lymphomas. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e166. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lambert SL, Martinez OM. Latent membrane protein 1 of EBV activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase to induce production of IL-10. J. Immunol. 2007;179:8225–8234. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thorley-Lawson DA. Epstein-Barr virus: exploiting the immune system. Nature Rev. Immunol. 2001;1:75–82. doi: 10.1038/35095584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schultheiss U, et al. TRAF6 is a critical mediator of signal transduction by the viral oncogene latent membrane protein 1. EMBO J. 2001;20:5678–5691. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.20.5678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Luftig M, et al. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 activation of NF-κB through IRAK1 and TRAF6. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:15595–15600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136756100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Atkinson PG, Coope HJ, Rowe M, Ley SC. Latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus stimulates processing of NF-κB2 p100 to p52. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:51134–51142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304771200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Song YJ, Jen KY, Soni V, Kieff E, Cahir-McFarland E. IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 is critical for latent membrane protein 1-induced p65/ReIA serine 536 phosphorylation and NF-κB activation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2689–2694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511096103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luftig M, et al. Epstein-Barr virus latent infection membrane protein 1 TRAF-binding site induces NIK/IKK α-dependent noncanonical NF-κB activation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:141–146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237183100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eliopoulos AG, et al. TRAF1 is a critical regulator of JNK signaling by the TRAF-binding domain of the Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent infection membrane protein 1 but not CD40. J. Virol. 2003;77:1316–1328. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1316-1328.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xie P, Hostager BS, Munroe ME, Moore CR, Bishop GA. Cooperation between TNF receptor-associated factors 1 and 2 in CD40 signaling. J. Immunol. 2006;176:5388–5400. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wan J, et al. Elucidation of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway mediated by Estein-Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein 1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:192–199. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.192-199.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Uemura N, et al. TAK1 is a component of the Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 complex and is essential for activation of JNK but not of NF-κB. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:7863–7872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509834200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dawson CW, Tramountanis G, Eliopoulos AG, Young LS. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway to promote cell survival and induce actin filament remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:3694–3704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209840200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lagunoff M, Lukac DM, Ganem D. Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif-dependent signaling by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K1 protein: effects on lytic viral replication. J. Virol. 2001;75:5891–5898. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.5891-5898.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lagunoff M, Majeti R, Weiss A, Ganem D. Deregulated signal transduction by the K1 gene product of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:5704–5709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee BS, et al. Characterization of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K1 signalosome. J. Virol. 2005;79:12173–12184. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.19.12173-12184.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tomlinson CC, Damania B. The K1 protein of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus activates the Akt signaling pathway. J. Virol. 2004;78:1918–1927. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.1918-1927.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Prakash O, et al. Activation of Src kinase Lyn by the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K1 protein: implications for lymphomagenesis. Blood. 2005;105:3987–3994. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee H, et al. Identification of an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif of K1 transforming protein of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:5219–5228. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Douglas J, Dutia B, Rhind S, Stewart JP, Talbot SJ. Expression in a recombinant murid herpesvirus 4 reveals the in vivo transforming potential of the K1 open reading frame of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 2004;78:8878–8884. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8878-8884.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brinkmann MM, et al. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and NF-κB pathways by a Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K15 membrane protein. J. Virol. 2003;77:9346–9358. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9346-9358.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]