Abstract

Purpose

The objective of this review is to summarize the potential issues faced by cancer survivors, define a conceptual framework for cancer survivorship, describe challenges associated with improving the quality of survivorship care, and outline proposed survivorship programs that may be implemented going forward.

Methods

We performed a non-systematic review of current cancer survivorship literature. Given its comprehensive scope and high profile, the Institute of Medicine’s recent report From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition served as the principal guide for the review.

Results

In recognition of the growing number of cancer survivors in the United States, survivorship has become an important health care concern. The Institute of Medicine’s recent report comprehensively outlined deficits in the care provided to cancer survivors and proposed mechanisms to improve the coordination and quality of follow-up care provided to this growing number of Americans. Measures to achieve these objectives include improving communication between health care providers through a Survivorship Care Plan, providing evidence-based surveillance guidelines, and assessing different models of survivorship care. Implementing coordinated survivorship care broadly will require additional health care resources and commitment from both health-care providers and payers. Research aimed to demonstrate the effectiveness of survivorship care will be important on this front.

Conclusions

Potential shortcomings in the recognition and management of ongoing issues faced by cancer survivors may impact the overall quality of long-term care in this growing population. Although programs to address these issues have been proposed, there is substantial work to be done in this area.

Introduction

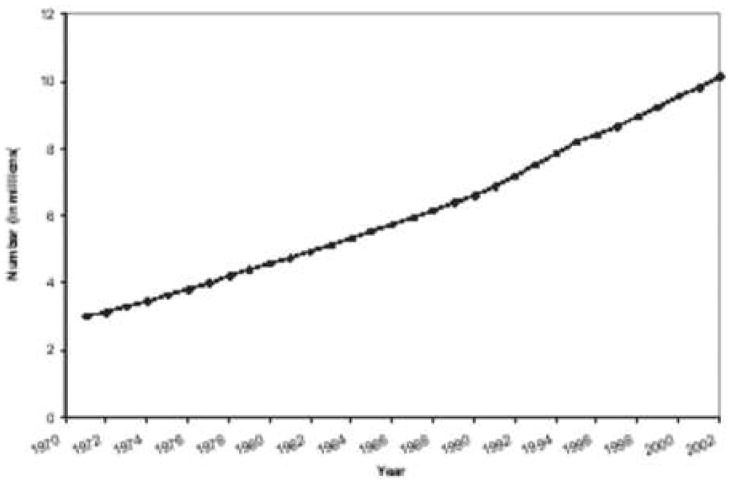

Improvements in cancer-directed therapies and management strategies have led to significant gains in survival over the past several decades. While additional progress is unquestionably necessary, a substantial proportion of adult cancer patients (an estimated 64%) currently reach 5-year survival,1 and the number of cancer survivors has grown steadily, increasing from 3 million in 1971 to more than 10 million in 2002.2 (Figure 1) Accordingly, the quality of cancer survivorship has gained recognition as an important but understudied area of cancer care. While few organized and comprehensive programs are currently in place, initiatives directed toward improving the quality of care provided to cancer survivors have become a priority among survivorship advocates and policy makers.

Figure 1. Estimated Number of Cancer Survivors in the United States from 1971–2002.

Adapted from the Institute of Medicine, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition2

Broadly defined, cancer survivorship encompasses the entire cancer continuum, from the initial diagnosis through the remainder of a cancer patient’s life. More explicitly, it is focused on the distinct phase of cancer care following active cancer-directed treatment, and comprehensively extends over a range of issues faced by survivors, including the physical, mental and social aspects of the cancer experience.2 For the more than 10 million cancer survivors living in the United States today, complications and long-term consequences related to the diagnosis and treatment of cancer can carry a substantial burden. Survivorship care encompasses these issues broadly, and includes surveillance for the impacts of cancer and treatment beyond disease recurrence. Accordingly, monitoring for late and long-term treatment-related effects, assessment of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) impairments, maintenance of general health, and management of the social and psychological facets of cancer recovery, including rehabilitation, adjustment and re-integration into normal daily life are all paramount concerns addressed by cancer survivorship.2

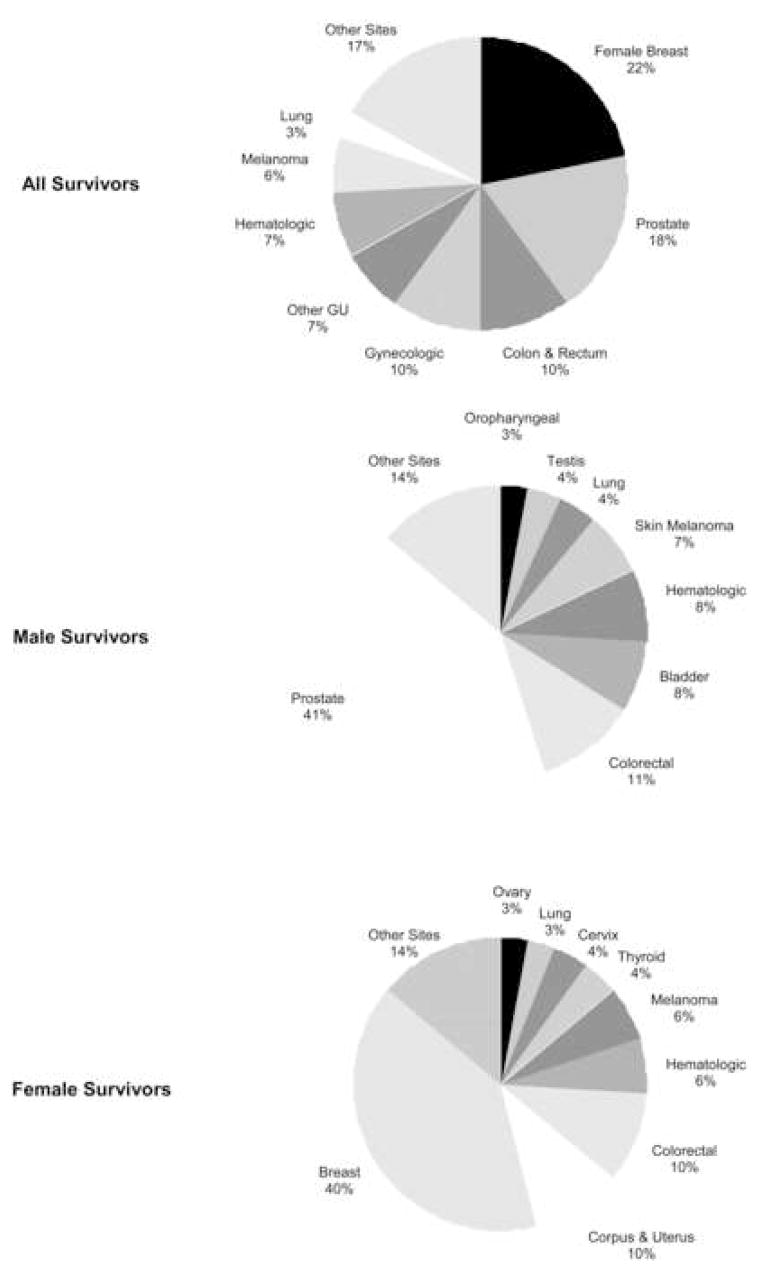

Although survivorship is an area of concern for a multitude of physicians, policy makers, and advocates for quality cancer care, those involved in the management of patient with urologic cancers have a particularly important stake in this developing field. Among the many million cancer survivors living in the United States, men treated for prostate cancer comprise the second largest group, following only breast cancer survivors in overall number. (Figure 2) In aggregate, urologic malignancies account for one-quarter of the total population of cancer survivors, and among male cancer survivors, greater than half are survivors of prostate, bladder, kidney and testis cancers.2 The issues faced by urologic cancer survivors may be substantial. In prostate cancer, examples range from functional and health-related quality life impairments for men treated for early-stage disease,3 to significant late-term effects, such as changes in body composition, bone loss, increased fracture risk,4 and development of diabetes and cardiovascular disease5 in those managed with androgen deprivation therapy. For young men successfully treated for testis cancer, issues related to disease surveillance, fertility and toxicity associated with radiation therapy and chemotherapy are highly relevant concerns. Similar examples exist for bladder and kidney cancer. Consequently, issues related to long-term cancer survivorship are important among those diagnosed and successfully treated for urologic cancers.

Figure 2. Distribution of Cancer Survivors in the United States by Cancer Site in 2002.

Adapted from the Institute of Medicine, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition2

Until recently, the long-term concerns and cancer-related issues specific to this prevalent and growing group have gone largely unrecognized. Transitioning from a relatively focused cancer control perspective to one inclusive of post-treatment surveillance, recovery and rehabilitation is required to adequately address and manage the late and long-term consequences of cancer and its treatment.6 The rise of prominent survivorship advocacy groups such as the National Coalition of Cancer Survivorship (NCCS)7 and the Lance Armstrong Foundation (LAF)8 underscore the importance of this challenge. Further support from influential organizations, such as the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and the American Cancer Society (ACS), has contributed to the dialogue surrounding survivorship initiatives. However, widespread implementation of structured programs has yet to gain traction and the role and form of survivorship care in the overall approach to cancer remains ill-defined. The purpose of this review is to outline the range of issues faced by cancer survivors, describe a conceptual framework for cancer survivorship, and review several proposed survivorship programs and potential challenges associated with improving the quality of survivorship care.

Defining and Prioritizing Cancer Survivorship

In response to the challenge issued by Fitzhugh Mullen, a physician and cancer survivor, to “map the middle ground of survivorship and minimize its medical and social hazards,”9 the Institute of Medicine (IOM) established a special committee to examine the medical and psychosocial issues faced by the growing number of cancer survivors. The resulting report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, outlined several objectives intended to raise awareness of the needs of cancer survivors, establish survivorship as a distinct phase of cancer care, and ensure that cancer survivors receive appropriate care during this often under-recognized phase of the cancer continuum.2 In total, ten recommendations were issued, ranging from survivor-directed interventions to system-based approaches. (Table 1) While some will likely be achievable without undue effort, others will require systematic restructuring of the care provided to cancer survivors. Yet others, such as recommendations to improve opportunities in survivorship research, will require a significant commitment from the health care community, including funding agencies invested in advancing cancer care.

Table 1. Institute of Medicine Recommendation Summary.

Adapted from the Institute of Medicine, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition2

| Recommendation 1 | Raise awareness of the needs of cancer survivors, establish cancer survivorship as a distinct phase of cancer care, and act to ensure the delivery of appropriate survivorship care. |

| Recommendation 2 | Provide a comprehensive care summary and follow-up plan (Survivorship Care Plan) that is clearly and effectively explained to all patients completing active cancer therapy. |

| Recommendation 3 | Use systematically developed evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, assessment tools, and screening instruments to help identify and manage late effects of cancer and its treatment. |

| Recommendation 4 | Develop quality of survivorship care measures and implement quality assurance programs to monitor and improve the care that all cancer survivors receive. |

| Recommendation 5 | Test models of coordinated, interdisciplinary survivorship care in diverse communities and across systems of care. |

| Recommendation 6 | Develop comprehensive cancer control plans that include consideration of survivorship care, and promoting the implementation, evaluation, and refinement of existing state cancer control plans. |

| Recommendation 7 | Expand and coordinate efforts to provide educational opportunities to health care providers to equip them to address the health care and quality of life issues facing cancer survivors. |

| Recommendation 8 | Act to eliminate discrimination and minimize adverse effects of cancer on employment, while supporting cancer survivors with short-term and long-term limitations in ability to work. |

| Recommendation 9 | Act to ensure that all cancer survivors have access to adequate and affordable health insurance with the assistance of insurers and health care payors. |

| Recommendation 10 | Increase funding support of survivorship research and expand mechanisms for its conduct. In the effort to better guide effective survivorship care. |

Survivorship Care Plan (SCP)

To a large extent, care following cancer treatment is typically focused on surveillance for disease recurrence. Despite the importance of this objective, other significant health problems may persist or become apparent later in the course of the cancer trajectory. In this setting, the success of the initial cancer treatment may be undermined by failing to anticipate and address later detrimental health effects. Establishing a Survivorship Care Plan has been suggested as one way to prevent the disconnect between successful initial cancer therapy and sub-optimal long-term follow-up care.2

For the majority of cancer survivors in the United States today, follow-up care is provided by a cancer specialist, and while intermittent communication between primary care physicians and cancer specialists may take place, coordination of follow-up care may be variable in many cases. As with many other facets of current follow-up care, the duration and intensity of surveillance may also vary widely. In general, ongoing, coordinated survivorship care does not extend beyond a relatively short follow-up period, and although special services are available to cancer survivors, most are underutilized.10 As a result, potential health problems may be missed by a myopic perspective. The lack of a comprehensive plan outlining the specific needs of cancer survivors may contribute to the incomplete transition of care from the cancer specialist to the primary care physician, resulting in lost opportunity to transfer essential information.1 Communication, if present, is often episodic and may fail to incorporate pertinent information which facilitates the primary care physician’s ability to provide high-quality and necessary follow-up care.1 In this setting, efforts focused at improving the overall quality of cancer care provided to cancer survivors are needed.

The Survivorship Care Plan is a tailored document created by those primarily responsible for cancer treatment for the purpose of providing detailed information regarding a patient’s cancer and treatment history and to define surveillance schedules, identify health priorities related to both cancer therapy and general health, and indicate how (by whom and in what setting) follow-up care is provided. It is tailored to each cancer survivor, can be modified according to developing concerns and needs, is shared with the patient, the primary care provider and members of the patient’s support network, and is modifiable upon completion of active therapy. Essential aspects include a comprehensive summary of all care received, detailed pertinent cancer-specific information, such as tumor characteristics, and a clear description of what ought to be done during both short- and long-term follow-up.11 This information is important to both survivors and their physicians, as a substantial number of patients are not knowledgeable about the treatments they have received.12 Additional information, such as the likely course of recovery, expected short-term toxicities related to treatment, outlined strategies for ongoing health maintenance, and recommended preventative treatments likely improve the utility of the plan, which may translate into better cancer care.11

A second goal of the Survivorship Care Plan is to optimize the continuity and coordination of care. Because the follow-up care for cancer patients is often complex, involves a number of health care providers and is not universally provided at a single treatment site, the potential for fragmented and poorly coordinated care exists. While some motivated cancer survivors organize treatment information and serve, in effect, as the coordinator of their own care, this is not the case for all. In fact, a significant number of patients are not certain which physician is responsible for their follow-up care, indicating that a more systematic process is needed.13 Consequently, health care providers and systems must adapt to the unique challenges inherent in managing a diverse group of patients who are often times mobile and receive care from a multitude of sources, physicians and locations. Specific provider identification and role definition is needed to optimize the coordination of the multi-faceted aspects of cancer care and surveillance, and also avoid unnecessary physician visits, redundant evaluations and inefficient utilization of limited resources. By serving as a transferable source of information, the Survivorship Care Plan is designed to address this frequently encountered gap in care.

Developing Evidence-Based Surveillance Guidelines and Post-Treatment Assessment

According the IOM recommendations,2 survivorship care should be founded on evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, assessment tools, and screening instruments. While disease surveillance is a standard part of the follow-up care currently provided to cancer survivors, the frequency and type of surveillance varies. For many cancers this stems, in part, from a lack of well-defined, evidence-based guidelines and may also reflect a lack of consensus among providers of cancer care.14 Close surveillance is most beneficial in situations where detection of recurrent disease results in intervention that prolongs survival. However, this is not the case for all diseases or clinical settings. Although both patients and providers appear to value close follow-up contact,15,16 early detection of disease recurrence often does not translate to an increased likelihood of salvage.17,18 Furthermore, while proponents of early surveillance argue for detecting and preventing potentially devastating complications related to disease recurrence, this has not been widely supported by clinical trials to date.19 Given the lack of clinical evidence and uncertainty regarding the appropriate frequency and intensity of surveillance, further work will be required to define optimal follow-up care for many cancers, including urologic malignancies.

In the absence of high-level clinical evidence, treatment and surveillance guidelines are largely consensus based for many cancers.20 The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has released evidence-based guidelines for breast and colorectal cancer, and comprehensive and detailed consensus-based guidelines are available through the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) for many others. However, the lack of well-defined evidence supporting surveillance procedures has resulted in substantial variability in how cancer survivors are followed, and consequently, many survivors receive more intense surveillance than recommended.21,22 More care does not always equate to better care. In breast and colorectal cancer, for example, evidence-based clinical guidelines support limited surveillance testing.23–25 Even in this setting, however, a significant proportion of survivors do not receive basic recommended follow-up care.22 Given these deficiencies, additional work is required to improve the quality of evidence defining surveillance recommendations and to assure that survivors receive optimal follow-up care. The benefits of this approach may be substantial – with well-conceived evidence-based guidelines, variations in clinical practice may be decreased, resulting in more efficient and potentially effective health care delivery.21 Furthermore, well-designed and supported clinical guidelines may facilitate the delivery of necessary care.11

Surveillance is not restricted to disease recurrence. The number of cancer survivors older than 65 years of age is steadily increasing, and an additional challenge is present in expanding surveillance to include non-cancer health problems in this aging population. For many cancer survivors, overall health may be as important as cancer-specific concerns, and although cancer patients are exposed to many difference health resources and professionals, they may not always receive the same quality of care for chronic medical problems during active cancer treatment and surveillance.26,27 To provide high quality care, cancer providers may have to partner with primary care physicians to ensure that cancer and general health issues are addressed appropriately. A survivor’s cancer experience may facilitate this objective; following successful cancer therapy, many survivors become more health conscious. This period has been referred to as a teachable moment in which attentive and motivated survivors can be encouraged to change health behaviors meaningfully.28 As a result, many advocate including modifiable health behaviors, such as smoking cessation, changes in diet, decreased alcohol consumption, and increased physical activity, in the Survivorship Care Plan. In addition, many survivorship advocates also argue for broadening survivorship care to include psychosocial issues and economic consequences following cancer treatment.2

Applied Models for Delivering Survivorship Care

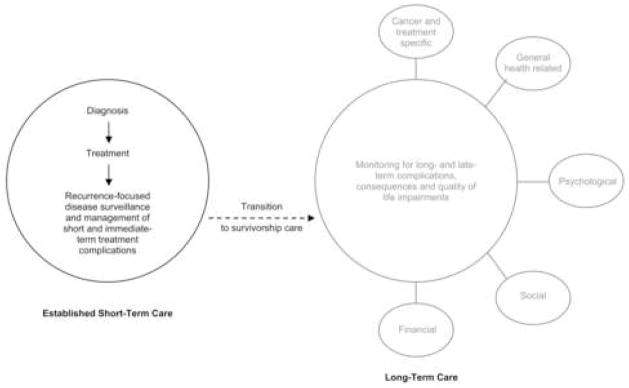

Conceptually, survivorship grows from established care following a cancer diagnosis. In this setting, treatment options are discussed and implemented, if appropriate. Following treatment, a period of surveillance is typical to detect short- and intermediate-term complications. A transition then exists to longer-term care. This period of survivorship care should be inclusive and encompass cancer-specific issues, general health concerns and less commonly assessed areas of potential impairment (Figure 3). It is this transition that is often the weak link in present care.2 Several different models have been proposed to provide quality survivorship care. While approaches vary, all models are directed toward the common goal of improving the quality of care provided to cancer survivors by delivering comprehensive, coordinated and tailored follow-up care. Because survivors comprise a large and diverse group, specific individual needs will vary considerably. The following sections summarize four commonly applied models for cancer survivorship.

Figure 3. Conceptual Model of Current Follow-Up Care and Cancer Survivorship.

Shared Care Model

The shared-care model, as implied, involves care shared and coordinated between two or more health care providers in different specialties or locations. Because this approach has been shown to improve outcomes and facilitate effective management in chronic diseases, such as diabetes and chronic renal disease,29,30 it is used extensively throughout the United States. The success of the shared care approach is regular, personal communication and periodic knowledge transfer between specialists and primary care physicians. Although additional assessment is necessary, the shared care model may be beneficial in improving the quality of cancer survivorship care. Involving more than one physician in the care of cancer survivors appears to increase the likelihood of quality care. For example, one study reported that colorectal cancer survivors managed by both an oncologist and a primary care physician were significantly more likely to receive recommended care compared to those managed by either one alone.27 Although experience with the shared-care model in cancer care is limited in the United States, several European and Canadian studies indicate that this model may be appropriate in caring for cancer survivors.19,31,32

Because the shared care model utilizes existing resources, it may be more easily implemented than other survivorship models. In addition, application of a Survivorship Care Plan may increase physician communication and coordination of care, and direct re-referral to the cancer specialist when late-term effects and concerns arise. The use of a care manager to serve as a coordinating intermediary between the oncologist and primary care physician has also been proposed as a potential refinement.33 Advances in technology may also improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the shared-care model. For example, increasing utilization of electronic medical systems may improve information transfer and physician communication. Successful shared care reintegrates the primary care physician into the overall care of the cancer survivor during a period in which general medical and health maintenance needs may be overshadowed by cancer-specific concerns.1

Risk-Based Follow-up Care

While some survivors will not require, nor desire, close follow-up care, those at high-risk of health detriment require more intense surveillance and care. In childhood cancers34,35 and breast cancer,36,37 a risk-based approach has been used to address differential surveillance requirements based on severity of disease, treatment characteristics and risk of detrimental health effects, and provide an appropriate level of care at the individual level.38 A principal component of the risk-based approach is that the survivorship follow-up plan is adaptable and can be tailored to the specific needs of each cancer survivor. Typically, nurses have been utilized as coordinators of such risk-based long-term follow-up clinics.35,39 In childhood cancers, these programs promote continuity40 and effectively manage cancer-related symptoms.41 The success of this model will depend on several factors, including identifying, redirecting and retraining a segment of health care providers, such as nurses, to serve as coordinators.2

Cancer-Specific Survivorship Clinics

Dedicated survivorship clinics are designed to provide a range of services and comprehensive care to cancer survivors in a single clinical setting. In many ways, this approach represents an extension of long-term follow-up programs used to manage the needs of childhood cancer survivors following completion of therapy.42 Several resources are brought together in long-term follow-up clinics; care is generally coordinated by an oncology nurse practitioner, a multidisciplinary approach consisting of surgical, medical and radiation oncologists as well as reconstructive surgeons is generally used, and many programs utilize social worker and psychiatry services. The central principles, such as risk-based assessment, and care coordination and continuity are transferable, and may contribute substantially to improved care among adult cancer survivors. Disease-specific cancer survivorship programs were first initiated in breast cancer to address treatment-related effects such as lymphedema, changes in body image, depression, weight control and less commonly, cardiac disease. Other disease-focused programs have been initiated, but are not as well-established. The structure, available resources and objectives vary according to disease and clinic design, however, few adult cancer survivors are likely followed in this setting.

Institution-Based Survivorship Programs

Comprehensive survivorship programs are under development at several academic cancer centers. In contrast to disease-specific survivorship clinics, these programs, which are institutionally-based, are directed toward providing coordinated and tailored care to survivors of all cancers in a single clinical setting. In theory, institution-based programs limit the redundancy inherent in operating several cancer-specific clinics. While potentially more complex, this approach utilizes shared clinical and research resources and expertise, and may ultimately prove to be more efficient than a multitude of separate disease-specific clinics.1 Resolving recognized challenges, such as ensuring flexibility in how survivors navigate and utilize program resources, are areas that will require innovation and novel thought going forward. There is growing interest and support for this model, as indicated by the network of cancer centers funded through the Lance Armstrong Foundation,8 and in the coming years, additional clinical experience, systems development and research will provide further insight into this developing model.

Survivorship Care in Urologic Cancers

While optimal surveillance procedures have not been completely defined for survivors of urologic cancers, several health concerns and impairments have emerged as potentially important areas of necessary care. For prostate cancer survivors, survivorship issues range from routine health-related quality of life assessment and management of urinary incontinence, sexual dysfunction and bowel complaints to consideration of the many side effects associated with androgen deprivation therapy, such as decreased bone mineral density and increased risk of skeletal fracture. Bladder cancer survivors treated with cystectomy experience changes in urinary and bowel function following urinary diversion, and long-term health concerns including downstream consequences related to gastrointestinal mal-absorption, HRQOL impairments and changes in body image may go under-recognized. For those bladder cancer survivors managed for non-muscle-invasive disease, frequency of surveillance and detection of recurrent disease are important considerations. Concerns for testis cancer survivors may focus on disease recurrence and preservation of fertility, however other important processes of surveillance, such as assessing the remaining testis for tumor development and monitoring for secondary malignancies for those exposed to radiation and chemotherapy should be considered. For survivors of kidney cancer, surveillance of renal function and disease recurrence are two common concerns; however without effective salvage therapy or evidence-based surveillance guidelines, follow-up imaging may be more commonly obtained than warranted. These examples are not meant to be a complete list of survivorship concerns faced by survivors of urologic cancers, but instead underscore the many issues and uncertainties regarding optimal and necessary survivorship care in this population.

The care of urologic cancer survivors may be improved in several ways. An important first step may be widespread implementation and application of Survivorship Care Plans. As previously discussed, common use of a Survivorship Care Plan likely facilitates physician communication, provides a guide for follow-up care, and assists in coordinating disease and health surveillance. In the case of prostate cancer survivors managed with androgen deprivation therapy, information related to disease severity, previous local treatments, if any, type, frequency and duration of ADT, side effects related to the hypogonadal state, and potential risks associated with prolonged ADT exposure, such as metabolic changes and bone mineral density loss, informs care givers regarding the treatment history, associated symptoms, and potential downstream health risks. Evidence-based surveillance practices are an additional area necessitating consideration. In several cases – cystoscopic surveillance for superficial bladder and radiographic imaging surveillance for renal cell carcinoma, are two examples – the optimal frequency and duration, as well as effectiveness of surveillance has not yet been determined. In the absence of evidence-based guidelines, clinicians may base surveillance care on consensus-based guidelines, such as those provided by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the American Urological Association.43 Program development and advancement in the form of disease-specific and institution-base survivorship clinics may serve as a logical next step to systematically improve survivorship care. While few organized survivorship programs are currently in place for prostate cancer survivors, the high rate of cancer control obtainable with treatment and the functional and health-related quality of life impairments associated with different therapies have resulted in a prevalent group of survivors who may benefit from structured, coordinated and tailored survivorship care. Although efforts are currently underway, such programs are in the earliest stages of development. Determining how patients respond to more structured and coordinated follow-up care, and more importantly, if the approaches outlined thus far improve patient outcomes are relevant questions that may be answered through concomitant clinical research in the setting of survivorship clinics.

Survivorship Research

While efforts and clinical initiatives directed at improving the care provided to cancer survivors are in the early stages of development, an equally important initiative is to promote and advance survivorship research. This is a potentially fertile area of translational research that will further facilitate the quality of care provided to cancer survivors. A number of important questions regarding survivorship remain to be answered. While the benefits of survivorship care are intuitive, coordinated and comprehensive care has not been tested empirically, and there is a potential for increased resource expenditure without concurrent improvement in outcomes. Consequently, survivorship models should be compared quantitatively and objectively. Defining optimal, evidence-based surveillance practices is an additional research priority in this area. As indicated in the cases of breast and colorectal cancer, more testing does not always lead to improved outcomes. For the majority of cancers, including urologic malignancies, questions regarding frequency, type and intensity of follow-up care have not been adequately addressed. Given the limited amount of research and knowledge currently available to push survivorship forward, the Institute of Medicine has identified this as a priority in its recommendations.

Outcomes metrics are also expanding, and increasingly, clinicians and researchers appreciate the importance of cancer-related outcomes other than survival. As therapy has become more effective and life has been prolonged, treatment related complications, health impairment and health-related quality of life have become more relevant and important outcomes. Quality of life research and survivorship experiences are interrelated, as both are measures of how patients treated for cancer function and experience life following cancer treatment. To date, survivorship research in prostate cancer has been largely based in HRQOL measurement and comparison, and several longitudinal population-based cohort studies have estimated the burden of disease and treatment using HRQOL as the primary measure.44 Building on these prior areas of research, future research efforts directed toward preventing and managing prevalent conditions and complications in cancer survivors would be beneficial. The results from such research may be used to guide follow-up survivorship care,45 as well as to inform guideline development and health policy.46

Survivorship research will benefit from directed efforts to increase long-term health assessment in both randomized clinical trials and observation studies. Indeed, the long-term nature of many survivorship issues requires substantial foresight and investment in longitudinal measures and data collection. While some have advocated incorporating long-term complication and health-related quality of life measures into randomized clinical trial,46 existing resources, such as the National Cancer Institute supported Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium and the Cancer Research Network may be an informative and efficient starting point.47,48 Regardless, the success of survivorship research initiative may ultimately be based on commitment to these endeavors.

Conclusion

As the number of individuals treated successfully for cancer has grown, health issues that extend beyond the immediate post-treatment and early surveillance phase of follow-up care have become more relevant. The number of cancer survivors in the United States will continue to grow, particularly in light of changes in the age structure projected in coming years. The cancer experience may result in health impairments that have previously gone unrecognized following successful cancer treatment. Furthermore, the follow-up care provided to the majority of cancer survivors is likely variable, and in many instances evidence guiding the type and intensity of surveillance is lacking. Substantial improvement in the quality of the care provided during the survivorship phase may be realized with initiatives directed towards improving the coordination of care and monitoring for long-term and late complications of cancer and its treatment. Although early in development, structured and coordinated survivorship care is gaining traction. Measures such as providing a Survivorship Care Plan at discharge from active cancer treatment may be realized without undue effort; however, greater challenges, such as ensuring efficient use of health care resources, implementing effective models of survivorship care, improving the quality of evidence supporting surveillance guidelines, providing additional opportunities for high-impact survivorship research and evaluating the overall effectiveness of survivorship care will ultimately determine the evolving role of survivorship care.

Acknowledgments

Support: Scott M. Gilbert, MD, is supported by NIH-1-T-32 DKO7782 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and by the American Urological Association Foundation (AUAF) Research Scholars Program.

Key Definitions for Abbreviations

- NCCS

National Coalition of Cancer Survivorship

- LAF

Lance Armstrong Foundation

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- ACS

American Cancer Society

- IOM

Institute of Medicine

- SCP

Survivorship Care Plan

- ASCO

American Society of Clinical Oncology

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- HRQOL

Health-Related Quality of Life

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5117–5124. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, D. C.: The National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller SC, Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Montie JE, Pimentel H, Sandler HM, et al. Long-term outcomes among localized prostate cancer survivors: health-related quality-of-life changes after radical prostatectomy, external radiation and brachytherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2772–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shahinian VB, Kuo YF, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Risk of fracture after androgen deprivation for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:154–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keating NL, O’Malley AJ, Smith MR. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease during androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4448–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grunfeld E. Looking beyond survival: how are we looking at survivorship? J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5166–5169. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Coalition of Cancer Survivorship. [Accessed February 2007]; Available at http://www.canceradvocacy.org/

- 8.Lance Armstrong Foundation. [Accessed February 2007]; Available at http://www.livestrong.org/

- 9.Mullan F. Seasons of survival: reflections of a physician with cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:270–273. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198507253130421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tesauro GM, Rowland JH, Lustig C. Survivorship resources for post-treatment cancer survivors. Cancer Pract. 2002;10:277–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.106007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Earle CC. Failing to plan is planning to fail: improving the quality of care with survivorship care plans. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5112–5116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makaryus AN, Friedman EA. Patients’ understanding of their treatment plans and diagnosis at discharge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:991–994. doi: 10.4065/80.8.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miedema B, MacDonald I, Tatemichi S. Cancer follow-up care. Patients’ perspectives. Can Fam Physician. 2003;49:890–895. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson FE. Overview. In: Johnson FE, Virgo KS, editors. Cancer Patient Follow-Up. St. Louis: Mosby; 1997. p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.The GIVIO investigators. Impact of follow-up testing on survival and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients. A multicenter randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1994;271:1587–1592. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03510440047031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muss HB, Tell GS, Case LD, Robertson P, Atwell BM. Perceptions of follow-up care in women with breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 1991;14:55–59. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199102000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fong Y, Cohen AM, Fortner JG, Enker WE, Turnbull AD, Coit DG, et al. Liver resection for colorectal metastases. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:938–946. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.NIH consensus conference. Ovarian cancer. Screening, treatment and follow-up. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Ovarian Cancer. JAMA. 1995;273:491–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grunfeld E, Levine MN, Julian JA, Coyle D, Szechtman B, Mirsky D, et al. Randomized trial of long-term follow-up for early-stage breast cancer: a comparison of family physicians versus specialist care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:848–855. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. [Accessed January 2007]; Available at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.asp.

- 21.Elston Lafata J, Simpkins J, Schultz L, Chase GA, Johnson CC, Yood MU, et al. Routine surveillance care after cancer treatment with curative intent. Med Care. 2005;43:592–599. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163656.62562.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper GS, Johnson CC, Lamerato L, Poisson LM, Schultz L, Simpkins J, et al. Use of guideline recommended follow-up care in cancer survivors: routine of diagnositic indications? Med Care. 2006;44:590–594. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000215902.50543.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith TJ, Davidson NE, Schapira DV, Grunfeld E, Muss HB, Vogel VG, 3rd, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology 1998 update of recommended breast cancer surveillance guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1080–1082. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bast RC, Jr, Ravdin P, Hayes DF, Bates S, Fritsche H, Jr, Jessup JM, et al. 2000 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in breast and colorectal cancer: clinical practice guidelines of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1865–1878. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desch CE, Benson AB, 3rd, Somerfield MR, Flynn PJ, Krause C, Loprinzi CL, et al. Colorectal cancer surveillance: 2005 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8512–8519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Earle CC, Burstein HJ, Winer EP, Weeks JC. Quality of non-breast cancer health maintenance among elderly breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1447–1451. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Earle CC, Neville BA. Under use of necessary care among cancer survivors. Cancer. 2004;101:1712–1719. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ganz PA. A teachable moment for oncologists: cancer survivors, 10 million strong and growing! J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5458–5460. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renders CM, Valk GD, de Sonnaville FF, Twisk J, Kriegsman DM, Heine RJ, et al. Quality of care for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a long-term comparison of two quality improvement programmes in The Netherlands. Diabet Med. 2003;20:846–852. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.01009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones C, Roderick P, Harris S, Rogerson M. An evaluation of a shared primary and secondary care nephrology service for managing patients with moderate to advanced CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47:103–114. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braun TC, Hagen NA, Smith C, Summers N. Oncologists and family physicians: using a standardized letter to improve communication. Can Fam Physician. 2003;49:882–886. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nielsen JD, Palshof T, Mainz J, Jensen AB, Olesen F. Randomized controlled trial of a shared care programme for newly referred cancer patients: bridging the gap between general practice and hospital. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:263–272. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.4.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oxman TE, Dietrich AJ, Williams JW, Jr, Kroenke K. A three-component model for reengineering systems for the treatment of depression in primary care. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:441–450. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.6.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hewitt M, Weiner SL, Simone JV. Childhood Cancer Survivorship: Improving Care and Quality of Life. Washington, D. C.: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oeffinger KC. Longitudinal risk-based health care for adult survivors of childhood cancer. Curr Probl Cancer. 2003;27:143–167. doi: 10.1016/s0147-0272(03)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: a follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:39–49. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Petersen L, Kahn B, Bower JE. Breast cancer in younger women: reproductive and late health effects of treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4184–4193. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallace WH, Blacklay A, Eiser C, Davies H, Hawkins M, Levitt GA, et al. Developing strategies for long term follow up of survivors of childhood cancer. BMJ. 2001;323:271–274. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7307.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hollen PJ, Hobbie WL. Establishing comprehensive specialty follow-up clinics for long-term survivors of cancer. Providing systematic physiological and psychosocial support. Support Care Cancer. 1995;3:40–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00343920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith ED, Walsh-Burke K, Crusan C. Principles of training social workers in oncology. In: Holland JC, editor. Psycho-Oncology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cox K, Wilson E. Follow-up for people with cancer: nurse-led services and telephone interventions. J Adv Nurs. 2003;43:51–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oeffinger KC, Eshelman DA, Tomlinson GE, Buchanan GR. Programs for adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2864–2867. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Urological Association Clinical Guidelines. [Accessed June 2007]; Available at www.auanet.org/guidelines/

- 44.Potosky AL, Harlan LC, Stanford JL, Gilliland FD, Hamilton AS, Albertsen PC, et al. Prostate cancer practice patterns and quality of life: the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1719–1724. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.20.1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giesler RB, Given B, Given CW, Rawl S, Monohan P, Burns D, et al. Improving the quality of life of patients with prostate cancer: a randomized trial testing the efficacy of a nurse-driven intervention. Cancer. 2005;104:752–62. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ayanian JZ, Jacobsen PB. Enhancing research on cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5149–5153. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Fletcher RH, Fouad MN, Harrington DP, Hahn KL, et al. Understanding cancer treatment and outcomes: the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2992–2996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wagner EH, Green SM, Hart G, Field TS, Fletcher S, Geiger AM, et al. Building a research consortium of large health systems: the Cancer Research Network. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005:3–11. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]