Abstract

Recent studies suggest that tumor-associated CD11b+Gr1+ myeloid cells contribute to refractoriness to antiangiogenic therapy with an anti-VEGF-A antibody. However, the mechanisms of peripheral mobilization and tumor-homing of CD11b+Gr1+ cells are unclear. Here, we show that, compared with other cytokines [granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), stromal derived factor 1α, and placenta growth factor], G-CSF and the G-CSF-induced Bv8 protein have preferential expression in refractory tumors. Treatment of refractory tumors with the combination of anti-VEGF and anti-G-CSF (or anti-Bv8) reduced tumor growth compared with anti-VEGF-A monotherapy. Anti-G-CSF treatment dramatically suppressed circulating or tumor-associated CD11b+Gr1+ cells, reduced Bv8 levels, and affected the tumor vasculature. Conversely, G-CSF delivery to animals bearing anti-VEGF sensitive tumors resulted in reduced responsiveness to anti-VEGF-A treatment through induction of Bv8-dependent angiogenesis. We conclude that, at least in the models examined, G-CSF expression by tumor or stromal cells is a determinant of refractoriness to anti-VEGF-A treatment.

Keywords: Bv8, resistance, prokineticin 2, bone marrow

Angiogenesis is important in several pathophysiological processes (1, 2). The VEGF signaling pathway has a key role in both physiological and pathological angiogenesis (3, 4). Bevacizumab, a humanized anti-VEGF-A (hereafter anti-VEGF) neutralizing mAb, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for cancer therapy, in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy (5, 6). Subsequently, 2 small molecule VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (sunitinib and sorafenib) were FDA approved (2). However, although these agents resulted in clinical benefits in multiple tumor types, similar to other anticancer drugs, a partial or complete lack of response to anti-VEGF agents has been reported in patients, as well as in some experimental models (7).

Over the last several years, the contribution of various bone marrow (BM)-derived cell types to tumor angiogenesis has been the object of intense investigation (8–11). Among these cell types, CD11b+Gr1+ cells are frequently increased in the tumors and in the peripheral blood (PB) of tumor-bearing animals, and have been shown to promote tumor angiogenesis (12), and to suppress immune functions, hence, the denomination of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) (13). However, the initiating mechanisms responsible for peripheral mobilization, tumor-homing, and acquisition of proangiogenic properties in CD11b+Gr1+ cells remain to be elucidated.

We reported that CD11b+Gr1+ cells have a role in mediating refractoriness to anti-VEGF treatment in mouse tumor models (14). Further experiments revealed that CD11b+Gr1+ cells produce several angiogenic factors, including Bv8, a secreted protein previously characterized as a mitogen for specific endothelial cell type, as a growth factor for hematopoietic progenitors (15, 16), and as a neuromodulator (17, 18). Analysis of several xenografts, as well as of a transgenic cancer model (RIP-Tag), suggested that Bv8 promotes tumor angiogenesis through increased peripheral mobilization of myeloid cells and local stimulation of angiogenesis (19, 20). We identified granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) as a strong inducer of Bv8 expression, both in vitro and in vivo. Physiologically, G-CSF has an important role in mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells, progenitors, and mature cells, particularly neutrophils, into the blood circulation (21, 22). G-CSF is also necessary for differentiation of progenitors to cells of granulocytic lineage, such as neutrophils, eosinophils and basophils. Although a few reports have suggested that G-CSF administration enhances tumor angiogenesis and growth (23, 24), the evidence implicating this factor in tumorigenesis is far from conclusive. To our knowledge, until now no study has tested whether G-CSF blockade affects tumor growth.

Here, we show that, compared with G-macrophage(M) CSF, stromal derived factor (SDF)1α, and placenta growth factor (PlGF), G-CSF and Bv8 show the strongest correlation with refractoriness to anti-VEGF in our tumor models. Administration of an anti-G-CSF mAb had little or no effect on growth of sensitive tumors. However, anti-G-CSF (or anti-Bv8) mAb resulted in reduced tumor angiogenesis and growth, and was additive to anti-VEGF mAb in refractory tumors. Strikingly, anti-G-CSF treatment reduced circulating and tumor-associated myeloid cells to the levels detected in mice bearing sensitive tumors. Conversely, treatment of mice bearing sensitive tumors with recombinant G-CSF or implantation of G-CSF-transfected cells resulted in increased CD11b+Gr1+ cell numbers and reduced responsiveness to anti-VEGF therapy.

Results

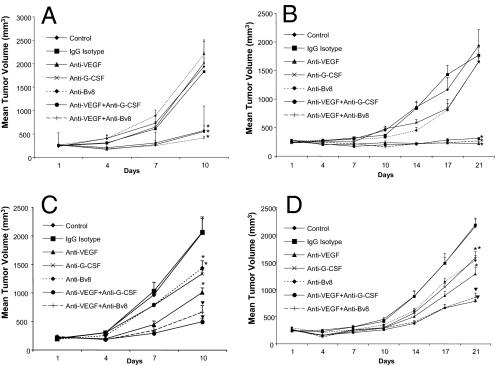

Anti-G-CSF or Anti-Bv8 Treatment Delays Growth of Refractory Tumors.

We previously identified the EL4 and LLC cell lines as refractory, and the B16F1 and Tib6 cell lines as sensitive to anti-VEGF mAb treatment (14). As shown in Fig. 1A, administration of anti-G-CSF Mab did not have any significant effect on growth of B16F1 tumors. Similarly, anti-Bv8 therapy did not inhibit tumor growth. Combination of anti-Bv8 (or anti-G-CSF) with anti-VEGF did not provide any therapeutic advantage over anti-VEGF alone, further suggesting that neither G-CSF nor Bv8 facilitates the growth of B16F1 cells. Interestingly, Tib6 tumors in 2 independent experiments showed some response to both anti-G-CSF and anti-Bv8 at early time points (day 14 postinoculation), but not later, suggesting a transient increase in G-CSF at early stages of tumor development (Fig. 1B). Similar to B16F1 tumors, combination of anti-VEGF with anti-Bv8 or anti-G-CSF did not provide any additivity in inhibiting Tib6 tumor growth compared with anti-VEGF alone. However, anti-G-CSF treatment reduced terminal EL-4 tumor volumes by ≈35%. Anti-VEGF had a slightly greater effect. However, the combination anti-G-CSF plus anti-VEGF resulted in almost 80% tumor growth inhibition (Fig. 1C). Anti-Bv8 had similar efficacy as anti-G-CSF. LLC tumors showed responses comparable with those observed in EL4 tumors (Fig. 1D). Monotherapy with anti-G-CSF or anti-Bv8 reduced terminal tumor size by ≈30%, similar to anti-VEGF. Combination treatments (anti-Bv8 plus anti-VEGF or anti-G-CSF plus anti-VEGF) caused a significant reduction in terminal tumor volume (≈60%). These data suggest a role for G-CSF and Bv8 in mediating refractoriness to anti-VEGF treatment.

Fig. 1.

Anti-G-CSF or anti-Bv8 treatments inhibit growth of refractory tumors. Balb-c nude mice [n = 10; 3 × 106 cells per mouse] were s.c. implanted with B16F1 (A), Tib6 (B), EL4 (C), or LLC (D) cells. Mice were treated with control IgG, anti-VEGF, anti-Bv8, anti-G-CSF, anti-Bv8 plus anti-VEGF, or anti-G-CSF plus anti-VEGF, as described in Methods. Tumor volume was measured at several time points as indicated, starting at day 1 posttumor cell inoculation. Graphs represent mean tumor volume ± SEM. *, significant difference (P < 0.05) in tumor volume when comparing each treatment vs. corresponding control-treated tumors. ▼, significant difference (P < 0.05) when comparing combination treatments (anti-Bv8 plus anti-VEGF or anti-G-CSF plus anti-VEGF) with anti-VEGF monotherapy.

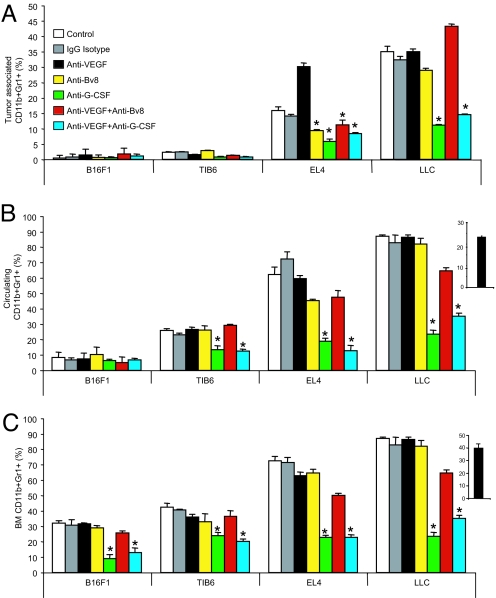

Anti-G-CSF Dramatically Reduces CD11b+Gr1+ Cells in Refractory Tumors.

We next examined the frequency of CD11b+Gr1+ cells in tumors, PB, and BM (Fig. 2; SI Methods). Both G-CSF (25) and Bv8 (16, 19) have been shown to induce peripheral mobilization of CD11b+Gr1+ cells. Tumor analysis revealed a greater frequency of CD11b+Gr1+ cells in refractory tumors compared with sensitive ones (Fig. 2A). This finding is consistent with the observation by De Palma et al. (26) that B16F1 tumors recruit very few leukocytes compared with LLC. Of note, the frequency of myeloid cells in LLC was much greater than EL4 tumors, indicating differences in the cytokine milieu among refractory tumors. Anti-G-CSF treatment significantly reduced the frequency of tumor associated CD11b+Gr1+ cells in both single and combination therapies in both EL4 and LLC tumors. However, anti-Bv8 significantly reduced homing of CD11b+Gr1+ in EL4, but not in LLC tumors, indicating that Bv8 is a more critical player in recruitment of myeloid cells in EL4 tumors. Interestingly, IHC detected Bv8 expression in refractory but not in sensitive tumors (Fig. S1A), and confirmed the crucial role of G-CSF in regulating Bv8 expression (19), because Bv8 was almost absent in LLC-tumors from anti-G-CSF treated mice (Fig. S1B). Also, Bv8-myeloperoxydase double staining confirmed the localization of Bv8 predominantly in neutrophils (Fig. S2)

Fig. 2.

Anti-G-CSF treatment targets CD11b+Gr1+ cells. Single cells were isolated from the tumors (A), PB (B), or BMMNCs (C) of mice bearing sensitive or refractory tumors, as indicated in the main text. Tumors were harvested when they reached ≈2,000 mm3 (late tumor growth), and were stained with rat anti-mouse CD11b-APC and rat anti-mouse Gr1-PE antibodies as described in SI Methods. Graphs represent mean frequency of CD11b+Gr1+ cells in each tissue, and bars represent SEM. *, significant difference (P < 0.05) in the frequency of myeloid cells when comparing each treatment vs. corresponding control-treated tumors. ▼, significant difference (P < 0.05) in combination treatments (anti-Bv8 plus anti-VEGF or anti-G-CSF plus anti-VEGF) vs. anti-VEGF monotherapy. Insets indicate frequency of myeloid cells in nontumor bearing mice.

Analysis of mononuclear cells (MNCs) in PB was in agreement with our findings in tumors. Anti-G-CSF treatment substantially decreased circulating CD11b+Gr1+ cells in animals bearing refractory tumors (Fig. 2B). Anti-Bv8 reduced the frequency of circulating myeloid cells in EL4-, but not in LLC-bearing animals. Interestingly, the magnitude of myeloid cell mobilization associated with LLC tumors was markedly greater than that in EL4 tumors. To further verify the FACS data, we measured the total numbers of leukocytes, as well as neutrophils and lymphocytes, in the PB in all of the groups (Fig. S3). The measurements were in agreement with FACS data, because anti-G-CSF dramatically reduced the number of white blood cells (Fig. S3A) and neutrophils (Fig. S3B), without affecting the number of lymphocytes.

Consistent with our previous observations (19), anti-Bv8 treatment did not affect the frequency of myeloid cells in the BM (Fig. 2C). In contrast, anti-G-CSF significantly reduced the frequency of myeloid cells in the BM.

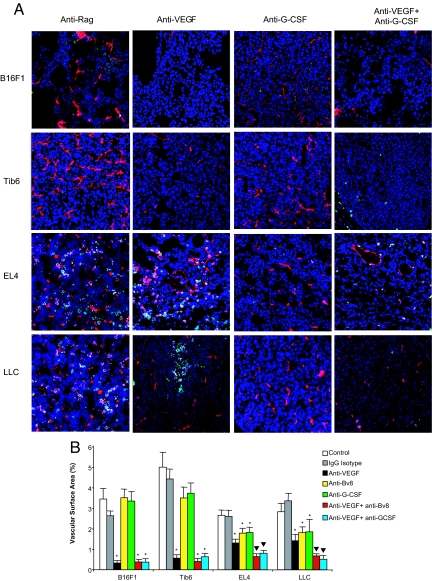

Inhibition of Tumor Angiogenesis in Anti-Bv8 or Anti-G-CSF Treated Animals.

Sections of tumors from all treatments groups were stained for CD31, CD11b, and Gr1 to study tumor vasculature, monocyte/macrophages, and neutrophils, respectively (Fig. 3; SI Methods and Fig. S4). Histological observations were consistent with FACS data, because refractory tumors showed greater infiltration of monocytes and neutrophils in control- and anti-VEGF-treated groups compared with sensitive tumors (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, we did not observe any difference in CD11b+Gr1+ cells between anti-Bv8 treated and control treated groups. However, EL4 and LLC sections from anti-Bv8 or anti-G-CSF-treated animals displayed a significant reduction in vascular surface area (VSA) in both monotherapy and combination treatment (Fig. 3B; Fig. S4). Therefore, even though anti-Bv8 did not markedly affect homing of myeloid cells in refractory tumors, it reduced tumor angiogenesis. In sensitive tumors, VSA measurement did not reveal any significant difference between anti-Bv8 or anti-G-CSF and control-treated tumors. Anti-VEGF-treated sensitive tumors showed a significant reduction in VSA compared with control-treated groups (Fig. 3B). This antivascular effect was not augmented by anti-Bv8 or anti-G-CSF. In contrast, refractory tumors showed a significant reduction in VSA in response to anti-Bv8 or anti-G-CSF treatment compared with control-treated tumors. Combination therapies (anti-VEGF with anti-Bv8 or anti-VEGF plus anti-G-CSF) induced a significant reduction in VSA compared with anti-VEGF monotherapy, further suggesting an antiangiogenic mechanism for anti-Bv8 or anti-G-CSF (Fig. 3; Fig. S4). In agreement with these conclusions, G-CSF, anti-G-CSF, Bv8, or anti-Bv8 had no effect on the in vitro proliferation of the tumor cells used in this study (Fig. S5). Also, by using RT-PCR, expression of G-CSF receptor was not detected in any of the tumor cell lines tested.

Fig. 3.

Anti-Bv8 or anti-G-CSF reduces tumor angiogenesis. (A) Sections from tumors treated with mono or combination treatments were stained with anti-CD31 (shown in red), anti-CD11b (shown in green), and anti-Gr1 (shown in pink) antibodies as described in SI Methods. Images of tumors (20×) were taken in a Zeiss confocal microscope. Due to space limitation, images from the control, anti-VEGF, anti-G-CSF, and combination of anti-VEGF and anti-G-CSF treatments have been included here. Images from other treatment groups are shown in Fig. S4. Consistent with FACS data (Fig. 2A), anti-G-CSF treatment significantly reduced CD11b+Gr1+ cells in the tumors. (B) Quantification of tumor vasculature indicated that anti-G-CSF or anti-Bv8 inhibits angiogenesis as monotherapy or in combination with anti-VEGF in refractory tumors. By using ImageJ, areas of CD31+ in each section were measured in 20–25 images from each treatment (n = 3). Bars represent the mean VSA ± SEM in each treatment. *, significant difference (P < 0.05) when comparing VSA in mono or combination therapy vs. controls. ▼, difference in combination treatment vs. anti-VEGF alone is significant (P < 0.05).

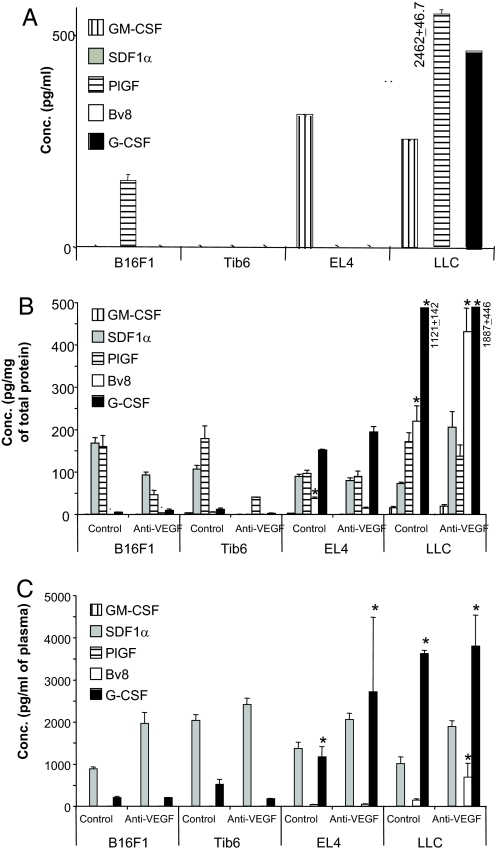

Higher Concentrations of G-CSF and Bv8 in Refractory Tumors.

We measured the concentrations of Bv8, G-CSF, and other cytokines (GM-CSF, SDF1α, and PlGF) in sensitive or refractory tumors (Fig. 4; SI Methods). GM-CSF is implicated in differentiation of hematopoietic progenitors (27) and in angiogenesis (28). SDF1α is abundant in tumor-associated fibroblasts, and has been implicated in recruitment of CXCR4+ cells to the tumors resulting in enhanced tumor angiogenesis (29). A recent study suggested a role for PlGF in mediating refractoriness to anti-VEGF treatment (30). However, quantitative analysis indicated that, among the above cytokines, G-CSF and Bv8 are the most enriched in the plasma and tumors in animals bearing refractory tumors. Other cytokines were either undetectable or were not significantly different in sensitive vs. refractory tumors. Very low levels of GM-CSF were detectable in all tumors, whereas PlGF and SDF-1α were detectable at higher concentrations in all tumor types, irrespective of the treatment. Interestingly, levels of G-CSF in tumor homogenates from LLC tumors were markedly higher than those from EL4 tumors, providing a possible explanation for the quantitative differences in the frequency of CD11b+Gr1+ between the 2 tumor types (Fig. 4B). To determine whether the tumor cells or the stroma is the source of these cytokines, we measured their concentrations in the conditioned media (CM) from cultured sensitive or refractory cells (Fig. 4A). However, neither SDF1α nor Bv8 was secreted by any of the tumor cells. Therefore, stromal cells such as tumor associated fibroblasts or myeloid cells are a likely source of these cytokines. Interestingly, G-CSF was detectable in LLC-CM, but not in EL4-CM, raising the possibility that tumor stroma is a source of G-CSF in EL4 tumors. In agreement with this hypothesis, initial observations indicated that fibroblasts isolated from EL4 tumors (31) release in the medium significant amounts of G-CSF. Also, GM-CSF was enriched in the CM of EL4 and LLC cells, but not in the CM of sensitive cell lines. Last, PlGF was present in the CM of B16F1 and LLC cells, but not other sensitive/refractory cells.

Fig. 4.

G-CSF and Bv8 are increased in refractory tumors. (A) Cytokine levels in the CM of tumor cells lines. All cell lines were incubated in DMEM plus 10% FBS for 72 h. CM were then collected and concentrated by Amicon Spin Columns (10-kDa MW cutoff; Millipore). Levels of GM-CSF, SDF1α, PlGF, Bv8, and G-CSF were measured by ELISA. (B and C) Balb-c nude mice were implanted with sensitive or refractory tumors as described, and were treated with control or anti-VEGF mAbs. By using ELISA, levels of GM-CSF, SDF1α, PlGF, Bv8, and G-CSF were quantified in the tumors (B) and plasma (C). *, significant difference (P < 0.05) when comparing levels of each cytokine in refractory tumors in the control/anti-VEGF treated mice with the corresponding ones in sensitive tumors.

Analysis of the same cytokines in plasma confirmed that only Bv8 and G-CSF were significantly increased in mice harboring refractory tumors (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, PlGF was not detected in the plasma, despite the fact that significant amounts were measured in some tumors (Fig. 4B), suggesting that this molecule is mostly retained in the local microenvironment, possibly due to its heparin-binding properties. Bv8 measurements in BMMNCs were in agreement with tumor data, because refractory tumors were associated with higher (P < 0.05) levels of Bv8 compared with sensitive ones (Fig. S6).

G-CSF Reduces Responsiveness to Anti-VEGF in a Sensitive Tumor.

G-CSF has been shown to promote tumor growth and angiogenesis in some experimental models (24). We tested whether G-CSF delivery might confer some resistance to anti-VEGF treatment. For this purpose, mice bearing B16F1 tumors received recombinant G-CSF, and were subsequently treated with control or anti-VEGF antibodies (Fig. 5A). G-CSF treatment was associated with reduced response to anti-VEGF, because tumor volume in G-CSF-treated mice was significantly greater than the volume in PBS treated animals. Similar results were observed in Tib6 tumors. G-CSF treatment resulted in a significant increase in the frequency of CD11b+Gr1+ cells in the tumors, PB, and BMMNCs (Fig. 5 B–E). Using flow cytometry (SI Methods), we detected an increase in tumor endothelial cells (CD31+CD45neg) in anti-VEGF treated mice that had received G-CSF compared with PBS.

Fig. 5.

G-CSF reduces responsiveness to anti-VEGF. (A) Balb-c nude mice (n = 10) were implanted with B16F1 cells [3 × 106 cells per mouse]. Mice received recombinant G-CSF or PBS i.p. for the first 4 days after tumor implantation and then at alternative days. Treatment with anti-VEGF or control mAbs was started at day 5 after tumor cell inoculation. Data represent mean tumor volumes ± SEM, and asterisks indicate significant difference when comparing G-CSF treated tumors in anti-VEGF treated mice vs. the corresponding control group. (B–E) Frequency of CD11b+Gr1+ cells in the tumors (B), PB (C), BMMNCs (D), and tumor-associated endothelial cells (CD31+CD45neg; E) were measured by using the same FACS technique as described. Asterisks indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05) when comparing myeloid cells in G-CSF treated mice with those in the PBS treated group. Treatment with G-CSF confers reduced responsiveness to anti-VEGF through induction of angiogenesis and infiltration of myeloid cells. (F) B16F1 cells were cotransfected with a mG-CSF expression plasmid and a vector conferring Zeocin resistance. The transfected cells were selected, expanded in culture, and characterized as described in SI Methods. Nude mice (n = 10) were implanted with 5 × 106 G-CSF- or control- transfected cells, and were treated with anti-VEGF, anti-Bv8, or control mAbs, starting at day 1 postinoculation. Data shown represent mean tumor volumes ± SEM, and asterisks indicate significant difference in B16F1-G-CSF tumors treated with anti-Bv8 or anti-VEGF vs. corresponding groups in the Vector tumors. (G–I) By using ELISA, levels of G-CSF (G) and Bv8 (H) in the tumors, and Bv8 in BMMNCs (I) were measured in all of the treatment groups. G-CSF is highly expressed in tumors derived from the G-CSF transfected lines, resulting in higher expression of Bv8 in tumors and BM. Note that the presence of anti-Bv8 antibodies may interfere with Bv8 measurements by ELISA.

We also transfected B16F1 cells with a G-CSF expression vector to create B16F1-G-CSF cells. B16F1-G-CSF tumors exhibited a reduced response to anti-VEGF compared with vector-transfected control tumors, which showed a nearly complete suppression by such treatment (Fig. 5F). Interestingly, anti-Bv8 treatment, which had almost no effect on the growth of the vector control group, inhibited growth of B16F1-G-CSF tumors by ≈50% (Fig. 5F), suggesting again a role for Bv8 as a mediator of G-CSF effects. As shown in Fig. 5 G and H, G-CSF-B16F1 transduced tumors contained dramatically higher amounts of G-CSF and Bv8 compared with controls. Anti-VEGF treatment reduced such increases, coincident with a smaller tumor mass. Also, as expected, G-CSF transfection was associated with markedly increased Bv8 levels in the BM (Fig. 5I). Therefore, G-CSF is sufficient to mediate refractoriness to anti-VEGF treatment through induction of Bv8-mediated angiogenesis.

Discussion

Previous studies indicated that tumor-associated CD11b+Gr1+ myeloid cells can confer refractoriness to anti-VEGF in mouse models (14). Therefore, identification of factors resulting in the recruitment/activation of these cells might yield therapeutic targets. Our earlier studies suggested that members of the VEGF family that interact selectively with VEGFR-1 (PlGF or VEGF-B) are unlikely to mediate myeloid cell recruitment and refractoriness to anti-VEGF in the same models (14).

Several studies have shown that CD11b+Gr1+ cells (or their functional counterparts) are frequently increased in tumor-bearing animals and in cancer patients. These cells have been reported to promote angiogenesis, and to suppress various T cell-mediated functions; thus, facilitating tumor-induced immune tolerance (11–13, 33–35). Numerous factors have been implicated in the recruitment and activation of CD11b+Gr1+ cells, including GM-CSF, M-CSF, IL-6, etc. (32). However, a clear link between CD11b+Gr1+ cells and G-CSF has yet to be established (32).

Some observations suggest that G-CSF has a role in angiogenesis. Administration of G-CSF has been reported to facilitate tissue repair in various ischemic conditions (36, 37). In addition, a few studies suggest that G-CSF is implicated in tumor angiogenesis. G-CSF (and GM-CSF) promoted tumor growth in a skin carcinoma model through paracrine action on stromal cells (38). Also, G-CSF administration to tumor-bearing mice enhanced tumor growth through recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells (24). Furthermore, high G-CSF productions have been associated with several malignancies, including head and neck (39), lung (40), and bladder (41) carcinomas.

In our models, Bv8 and G-CSF were preferentially expressed in the refractory tumors. Other cytokines implicated in hematopoietic cell mobilization/angiogenesis such as GM-CSF, SDF1α, and PLGF were either undetectable or similarly expressed in both sensitive and refractory tumors. Both anti-Bv8 and anti-G-CSF inhibited growth of refractory tumors in single or combination treatments. However, only anti-G-CSF treatment resulted in a dramatic suppression in the number of circulating and tumor-associated CD11b+Gr1+ cells. Our data point to the conclusion that Bv8 primarily functions as a local regulator of angiogenesis, because anti-Bv8 treatment did not markedly affect circulating myeloid cells, likely due to the high G-CSF levels, especially in LLC. Indeed, the inability of anti-Bv8 to reduce CD11b+Gr1+ cells in such refractory tumors appears consistent with our earlier observation that blocking Bv8 reduces the increases in circulating CD11b+Gr1+ cells in response to a low but not to a maximal dose of G-CSF (19). In contrast, anti-G-CSF significantly reduced both myeloid cell mobilization and tumor angiogenesis.

G-CSF, delivered by 2 different modalities, did not significantly enhance tumor growth in the model examined, but resulted in reduced responsiveness to anti-VEGF treatment. Administration of an anti-Bv8 antibody to mice bearing G-CSF expressing cells significantly reduced tumor growth. This finding points to a role for Bv8 in mediating the proangiogenic effects of G-CSF. Studies are required to further dissect the roles of Bv8 vs. G-CSF in tumor growth.

G-CSF is widely used in cancer therapy, and its use has dramatically reduced the risks associated with chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and facilitated delivery of maximally effective doses of cytotoxic agents (42, 43). Nevertheless, ours and other investigators' findings suggest that G-CSF may, in some circumstances, facilitate tumor angiogenesis. In particular, our results raise the possibility that G-CSF administration may result in reduced responsiveness to an anti-VEGF agent. Considering the widespread clinical use of both G-CSF and VEGF pathway inhibitors, further studies are warranted to investigate these issues.

Although our data demonstrate that an anti-G-CSF or anti-Bv8 neutralizing antibodies can reduce tumor growth and be additive to anti-VEGF, such combinations did not completely block tumor growth, suggesting that additional mechanisms are likely to be involved in VEGF-independent angiogenesis. Very recently, we identified an additional proangiogenic mechanism in the EL-4 model, mediated by PDGF-C up-regulation in tumor-associated fibroblasts (31). These findings suggest that, even within the same tumor, multiple molecular and cellular mechanisms resulting in VEGF-independent angiogenesis may coexist.

In conclusion, our study shows that targeting G-CSF, a key regulator of hematopoiesis, results in growth inhibition in some tumors. We also show that G-CSF can be involved in the development of refractoriness to an anti-VEGF agent.

Methods

BALB/c nude mice (6–8 weeks) were purchased from Charles River, and were maintained under the guidelines of the Genentech animal care facility. For tumor cell inoculation, mice were anesthetized by using isoflurane inhalation, and were s.c. implanted with 3.5 × 106 cells in 100 μL of growth factor-reduced matrigel (BD BioScience). B16F1, Tib6, EL4, and LLC cell lines were purchased from ATCC, and were routinely grown in DMEM (GIBCO BRL, Invitrogen), supplemented with 10% serum and 2 mM glutamine. Neutralizing anti-mouse G-CSF mAb (MAB414) and the matching Isotype IgG control (R & D Systems) were administered at the dose of 10 μg/day. Mouse anti-Bv8 mAbs 2B9 plus 3F1 or control anti-Ragweed mAb (hereafter control) were administered at the total dose or 10 mg/kg by i.p. route of administration as described (19). Hamster anti-mouse Bv8 mAb 2D3, an antibody suitable for immunoneutralization and immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Genentech), was administered at the dose of 10 mg/kg twice weekly. Anti-VEGF mAb G6–31has been previously described (44), and was administered at the dose of 5 mg/kg twice a week. Mice were killed when tumors reached ≈2,000 mm (3). For gain-of-function studies, rhG-CSF (Amgen) was i.p administered at the dose of 10 μg per mouse for 4 consecutive days, followed by treatment on alternate days. In all experiments, tumor volumes were measured by using a caliper, as described (14).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank M. Singh for assistance in IHC staining, and Y. Crawford for measuring G-CSF in cultured fibroblasts.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors are employees and shareholders of Genentech, Inc.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0902280106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ferrara N, Kerbel RS. Angiogenesis as a therapeutic target. Nature. 2005;438:967–974. doi: 10.1038/nature04483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerbel RS. Tumor angiogenesis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2039–2049. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0706596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis LM, Hicklin DJ. VEGF-targeted therapy: Mechanisms of anti-tumour activity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrc2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrara N, Hillan KJ, Gerber HP, Novotny W. Discovery and development of bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:391–400. doi: 10.1038/nrd1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giantonio BJ, et al. 3rd: Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin (FOLFOX4) for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: Results from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E3200. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1539–1544. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shojaei F, Ferrara N. Refractoriness to antivascular endothelial growth factor treatment: Role of myeloid cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5501–5504. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rafii S, Lyden D, Benezra R, Hattori K, Heissig B. Vascular and haematopoietic stem cells: Novel targets for anti-angiogenesis therapy? Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:826–835. doi: 10.1038/nrc925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Palma M, Murdoch C, Venneri MA, Naldini L, Lewis CE. Tie2-expressing monocytes: Regulation of tumor angiogenesis and therapeutic implications. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:519–524. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shojaei F, Zhong C, Wu X, Yu L, Ferrara N. Role of myeloid cells in tumor angiogenesis and growth. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang L, et al. Expansion of myeloid immune suppressor Gr+CD11b+ cells in tumor-bearing host directly promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bronte V, et al. Identification of a CD11b(+)/Gr-1(+)/CD31(+) myeloid progenitor capable of activating or suppressing CD8(+) T cells. Blood. 2000;96:3838–3846. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shojaei F, et al. Tumor refractoriness to anti-VEGF treatment is mediated by CD11b+Gr1+ myeloid cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:911–920. doi: 10.1038/nbt1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LeCouter J, et al. The endocrine-gland-derived VEGF homologue Bv8 promotes angiogenesis in the testis: Localization of Bv8 receptors to endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2685–2690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337667100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LeCouter J, Zlot C, Tejada M, Peale F, Ferrara N. Bv8 and endocrine gland-derived vascular endothelial growth factor stimulate hematopoiesis and hematopoietic cell mobilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16813–16818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407697101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng MY, et al. Prokineticin 2 transmits the behavioural circadian rhythm of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Nature. 2002;417:405–410. doi: 10.1038/417405a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsumoto S, et al. Abnormal development of the olfactory bulb and reproductive system in mice lacking prokineticin receptor PKR2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4140–4145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508881103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shojaei F, et al. Bv8 regulates myeloid cell-dependent tumour angiogenesis. Nature. 2007;450:825–831. doi: 10.1038/nature06348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shojaei F, Singh M, Thompson JD, Ferrara N. Role of Bv8 in neutrophil-dependent angiogenesis in a transgenic model of cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2640–2645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712185105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rapoport AP, Abboud CN, DiPersio JF. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF): Receptor biology, signal transduction, and neutrophil activation. Blood Rev. 1992;6:43–57. doi: 10.1016/0268-960x(92)90007-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lieschke GJ, et al. Mice lacking granulocyte colony-stimulating factor have chronic neutropenia, granulocyte and macrophage progenitor cell deficiency, and impaired neutrophil mobilization. Blood. 1994;84:1737–1746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Natori T, et al. G-CSF stimulates angiogenesis and promotes tumor growth: Potential contribution of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:1058–1061. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02335-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okazaki T, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor promotes tumor angiogenesis via increasing circulating endothelial progenitor cells and Gr1+CD11b+cells in cancer animal models. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1–9. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basu S, Hodgson G, Katz M, Dunn AR. Evaluation of role of G-CSF in the production, survival, and release of neutrophils from bone marrow into circulation. Blood. 2002;100:854–861. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.3.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Palma M, Venneri MA, Roca C, Naldini L. Targeting exogenous genes to tumor angiogenesis by transplantation of genetically modified hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2003;9:789–795. doi: 10.1038/nm871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamilton JA, Anderson GP. GM-CSF Biology. Growth Factors. 2004;22:225–231. doi: 10.1080/08977190412331279881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valdembri D, Serini G, Vacca A, Ribatti D, Bussolino F. In vivo activation of JAK2/STAT-3 pathway during angiogenesis induced by GM-CSF. FASEB J. 2002;16:225–227. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0633fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orimo A, et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischer C, et al. Anti-PlGF Inhibits Growth of VEGF(R)-Inhibitor-Resistant Tumors without Affecting Healthy Vessels. Cell. 2007;131:463–475. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crawford Y, et al. PDGF-C mediates the angiogenic and tumorigenic properties of fibroblasts associated with tumors refractory to anti-VEGF treatment. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marigo I, Dolcetti L, Serafini P, Zanovello P, Bronte V. Tumor-induced tolerance and immune suppression by myeloid derived suppressor cells. Immunol Rev. 2008;222:162–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Filipazzi P, et al. Identification of a new subset of myeloid suppressor cells in peripheral blood of melanoma patients with modulation by a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulation factor-based antitumor vaccine. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2546–2553. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Almand B, et al. Increased production of immature myeloid cells in cancer patients: A mechanism of immunosuppression in cancer. J Immunol. 2001;166:678–689. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Youn JI, Nagaraj S, Collazo M, Gabrilovich DI. Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:5791–5802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ripa RS, et al. Intramyocardial injection of vascular endothelial growth factor-A165 plasmid followed by granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to induce angiogenesis in patients with severe chronic ischaemic heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1785–1792. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee ST, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor enhances angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia. Brain Res. 2005;1058:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mueller MM, et al. Tumor progression of skin carcinoma cells in vivo promoted by clonal selection, mutagenesis, and autocrine growth regulation by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1567–1579. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62541-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ninck S, et al. Expression profiles of angiogenic growth factors in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:34–44. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hasegawa S, Suda T, Negi K, Hattori Y. Lung large cell carcinoma producing granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:308–310. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirasawa K, Kitamura T, Oka T, Matsushita H. Bladder tumor producing granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and parathyroid hormone related protein. J Urol. 2002;167:2130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crawford J, et al. Reduction by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor of fever and neutropenia induced by chemotherapy in patients with small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:164–170. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107183250305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lyman GH, Kuderer NM, Djulbegovic B. Prophylactic granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in patients receiving dose-intensive cancer chemotherapy: A meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2002;112:406–411. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liang WC, et al. Cross-species vegf-blocking antibodies completely inhibit the growth of human tumor xenografts and measure the contribution of stromal vegf. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:951–961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508199200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.