Abstract

Objective To investigate basic assumptions and other methodological problems in the application of indirect comparison in systematic reviews of competing healthcare interventions.

Design Survey of published systematic reviews.

Inclusion criteria Systematic reviews published between 2000 and 2007 in which an indirect approach had been explicitly used. Identified reviews were assessed for comprehensiveness of the literature search, method for indirect comparison, and whether assumptions about similarity and consistency were explicitly mentioned.

Results The survey included 88 review reports. In 13 reviews, indirect comparison was informal. Results from different trials were naively compared without using a common control in six reviews. Adjusted indirect comparison was usually done using classic frequentist methods (n=49) or more complex methods (n=18). The key assumption of trial similarity was explicitly mentioned in only 40 of the 88 reviews. The consistency assumption was not explicit in most cases where direct and indirect evidence were compared or combined (18/30). Evidence from head to head comparison trials was not systematically searched for or not included in nine cases.

Conclusions Identified methodological problems were an unclear understanding of underlying assumptions, inappropriate search and selection of relevant trials, use of inappropriate or flawed methods, lack of objective and validated methods to assess or improve trial similarity, and inadequate comparison or inappropriate combination of direct and indirect evidence. Adequate understanding of basic assumptions underlying indirect and mixed treatment comparison is crucial to resolve these methodological problems.

Introduction

Well designed head to head randomised controlled trials are generally considered to provide the most rigorous research evidence on the relative effects of interventions.1 Evidence from such trials is often limited or unavailable, however, and indirect comparison may be necessary.2 3

A simple but inappropriate method is to compare the results of individual arms from different trials as if they were from the same trial. This unadjusted indirect comparison has been criticised for discarding the within trial comparison, increasing liability to bias and over- precise estimates.2 The adjusted indirect comparison can, however, take advantage of the strength of randomised controlled trials in making unbiased comparisons (see box).4 5 Here the indirect comparison of different interventions is adjusted by comparing the results of their direct comparisons with a common control group.

A simple example of indirect comparison

The case study compared bupropion with nicotine replacement therapy patch for smoking cessation.6 The outcome was the number of smokers who failed to quit at 12 months (table). Indirect comparison can be made using two sets of randomised controlled trials: nine that compared bupropion with placebo and 19 that compared nicotine replacement therapy with placebo. One trial also compared bupropion with nicotine replacement therapy.7

Number of smokers failing to quit at 12 months, according to treatment group

| Comparison | No of trials | Odds ratio (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bupropion v placebo | 9 | 0.51 (0.36 to 0.73) | 54 |

| NRT patch v placebo | 19 | 0.57 (0.48 to 0.67) | 12 |

| Bupropion v NRT patch: | |||

| Direct comparison | 1 | 0.48 (0.28 to 0.82) | — |

| Adjusted indirect comparison | 9+19 | 0.90 (0.61 to 1.34) | — |

| Combined (direct+indirect) | 1+(9+19) | 0.68 (0.37 to 1.25) | 71 |

NRT=nicotine replacement therapy.

See Bucher et al5 and Song et al4 for indirect comparison methods. Random effects model was used in meta-analyses of trials and for combination of direct and indirect estimates.8

Indirect comparison

The results of placebo controlled trials suggested that both active treatments are more effective than placebo for smoking cessation. The results of the two sets of placebo controlled trials can also be used to indirectly compare the active treatments. Compared with placebo, the magnitude of treatment effect of bupropion (odds ratio 0.51, 95% confidence interval 0.36 to 0.73) was similar to that of nicotine replacement therapy (0.57, 0.48 to 0.67). Therefore it could be indirectly concluded that the treatments were equally effective. The adjusted indirect comparison can also be formally done, using one of several sound methods. The result of adjusted indirect comparison suggests that bupropion was as effective as nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation (0.90, 0.61 to 1.34), although the confidence interval is wide. The validity of the adjusted indirect comparison depends on a similarity assumption, assuming that the two sets of placebo controlled trials are sufficiently similar for moderators of relative treatment effect.

Comparison of direct and indirect estimates

The result of the head to head comparison trial suggested that bupropion was more effective than nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation (0.48, 0.28 to 0.82). The discrepancy between the direct and indirect estimate was marginally significant (I2=71%, P=0.06). Statistical methods are available to combine the results of direct and indirect evidence (combined odds ratio 0.68, 95% confidence interval 0.37 to 1.25). A consistency assumption is, however, required to combine the estimates. The combination of inconsistent evidence from different sources may provide invalid and misleading results.

To improve statistical power, evidence generated by indirect comparison can be combined with evidence from head to head trials,9 10 11 facilitated by the development of network meta-analysis12 and Bayesian hierarchical models for mixed treatment comparisons.13

Empirical evidence indicates that the results of an adjusted indirect comparison usually but not always agree with the results of direct comparison trials.4 Recently, conflicting evidence has emerged about the validity of indirect comparison,6 therefore the potential usefulness of adjusted indirect comparison is still overshadowed by concern about bias resulting from its misuse.

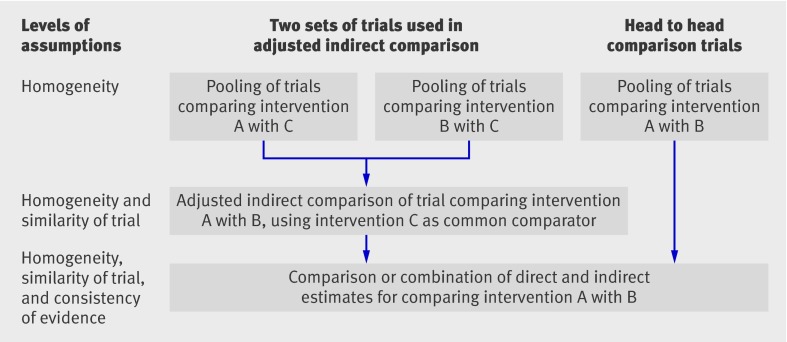

Existing statistical methods for adjusted indirect comparison and mixed treatment comparison are unbiased, but only if some assumptions are fulfilled.2 The description of important assumptions underlying indirect comparison may not be clear in some methodological studies. For mixed treatment comparison it was noted that “the only additional assumption is that the similarity of the relative effects of treatment holds across the entire set of trials, irrespective of which treatments were actually evaluated.”9 However, the additional assumption may hold to a subset of trials but not across the entire set of trials. We suggest a framework to delineate the main assumptions related to indirect and mixed treatment comparison (figure).

Assumptions underlying adjusted indirect and mixed treatment comparison

Assumptions concerning adjusted indirect comparison and mixed treatment comparison are similar to but more complex than the underlying assumption for standard meta-analysis. At least three issues of comparability need consideration: a homogeneity assumption for each meta-analysis, where different trials are sufficiently homogeneous and estimate the same treatment effect (fixed effect model) or different treatment effects distributed around a typical value (random effects model); a similarity assumption for individual adjusted indirect comparison, where trials are similar for moderators of relative treatment effect; and a consistency assumption for the combination of evidence from different sources (figure).

We report findings from a survey of methodological problems in the application of indirect and mixed treatment comparison.

Methods

We searched PubMed for systematic reviews or meta-analyses published between 2000 and 2007 in which indirect comparison had been explicitly used (see bmj.com). The titles and abstracts of retrieved references were independently assessed by two reviewers to identify relevant reviews.

We extracted data on clinical indications, interventions compared, comprehensiveness of the literature search for trials used in indirect comparison, methods for indirect comparison, and whether direct evidence from head to head comparison trials was also available. We examined whether the assumption of similarity was explicitly mentioned and whether any efforts were made to investigate or improve the similarity of trials for indirect comparison. One reviewer extracted data and another checked each study.

Results

Overall, 88 review reports (91 publications) were included: 59 were reviews of effectiveness of interventions, 19 were reports of health technology assessment or cost effectiveness analysis, six were Cochrane reviews, and four were reviews used to illustrate methods for indirect comparisons.

Indirect comparison was used to evaluate drug interventions in 72 of the reviews: 43 compared drugs of different classes, 17 drugs of the same class, and 10 different formats or modes of delivery of the same drug. Two reviews compared the relative efficacy of an active drug with placebo. Non-drug interventions were indirectly compared in 16 reviews.

The most commonly used approach (49/88) was the adjusted indirect comparison using classic frequentist methods (see bmj.com). More complex methods (network or Bayesian hierarchical meta-analysis) were used in 18 reviews. In 13 reviews, indirect comparison was informal, without calculation of relative effects or testing for statistical significance. In six reviews results from different trials were naively compared without using a common treatment control.

Direct evidence from head to head comparison trials was available in 40 reviews (see bmj.com), including 15 that used simple adjusted methods, 16 that used complex methods, and six that used informal methods. Compared with simple adjusted methods, complex methods were more likely to be used to combine the direct and indirect evidence. Where direct comparison was available, direct and indirect evidence were combined in 15 of the reviews that used complex methods and in only two of the reviews that used simple methods (see bmj.com). Furthermore, direct and indirect evidence were less likely to be explicitly compared in reviews that used complex rather than simple methods (9 v 11).

The assumption of trial similarity was explicitly mentioned or discussed in only 40 reviews (see bmj.com). Explicit mention of the similarity assumption was associated with efforts to examine or improve the similarity between trials for indirect comparisons (30/40 v 19/48). Methods to investigate or improve trial similarity included subjective judgment by a comparison of study characteristics (n=26) and subgroup and metaregression analysis to identify or adjust for possible moderators of treatment effects (n=23). The assumption of consistency was not explicit in most cases where direct and indirect evidence were compared or combined (18/30; see bmj.com).

In eight reviews, indirect comparison was based on data from other published systematic reviews or meta-analyses (see bmj.com). Evidence from head to head comparison trials was not systematically searched for or not included in nine cases (see bmj.com).

Discussion

Indirect comparison is being increasingly used for the evaluation of a wide range of healthcare interventions. In this study, 16 of the 88 included reviews were health technology assessment reports. In many such reports, indirect comparison had not been done for clinical effectiveness but was used in the economic evaluation.

In the literature, several related but different assumptions underlying adjusted indirect comparison (figure) have not been clearly distinguished, resulting in methodological and practical problems in the interpretation of indirect or mixed treatment comparison. The problems include unclear understanding of underlying assumptions, inappropriate search and selection of relevant trials, use of inappropriate or flawed methods, lack of objective and validated methods to assess or improve trial similarity, and inadequate comparison or inappropriate combination of direct and indirect evidence.

Indirect comparison was explicit but informal in 13 reviews—neither relative effects nor statistical significance were calculated. Since the use of indirect comparison is often inevitable, a more explicit and formal approach is preferable. In six reviews, the results from individual arms of different trials were compared naively as if they were from one controlled trial. This approach is flawed because the strength of randomisation is disregarded.2

The strength of randomisation could be preserved in adjusted indirect comparison. The most common scenario was the indirect comparison of two competing interventions adjusted by common comparators using classic frequentist methods (including simple metaregression). The advantages of the simple methods include ease of use and transparency. However, when there are several alternative interventions to be compared, the simple adjusted indirect comparison may become inconvenient. More complex methods, such as network meta-analysis, are being increasingly used to make simultaneous comparisons of multiple interventions.10 12 13 These methods treat all included interventions equally rather than focusing on one particular comparison of two interventions.

Subgroup analysis and metaregression are commonly used to assess or improve trial similarity for adjusted indirect comparison (see bmj.com). Their usefulness may be limited because the number of trials involved in adjusted indirect comparison was usually small and it was uncertain whether the important study level variables were reported in all relevant trials.

Trial similarity was often assessed by examining heterogeneity across trials and by a narrative comparison of trial characteristics for the different treatment comparisons being included, which may be deemed informal and subjective.

When data from head to head comparison trials are available, consideration needs to be given to whether an indirect comparison is justified when direct comparison trials are available; any discrepancies between direct and indirect evidence need to be sensibly interpreted; and could direct evidence be combined with the results of indirect comparison.

It is controversial whether indirect evidence needs to be considered when there is evidence from direct comparison trials.5 9 Indirect comparison was considered helpful by authors of the 40 reviews in which both direct and indirect evidence were available. Such evidence was less likely to be explicitly compared and more likely to be combined in reviews that used complex rather than simple methods (see bmj.com). Since the evidence consistency is usually assessed informally and subjectively,9 transparency is important to allow others to make their own judgment.

Reviews may include trials with three or more arms. Some reviews separately compared two active treatments with placebo within the same trial, and then the results of two separate comparisons were used in adjusted indirect comparison. This downgrades direct evidence to indirect evidence, reduces precision, and uses data from the same placebo arm twice.

In nine reviews, direct comparison trials were excluded or not searched for systematically. In reviews that included only placebo controlled trials, it was often unclear whether there were other active treatment controlled trials that could also be used for adjusted indirect comparison. Some indirect comparisons seemed to be done on an ad hoc basis, using data from existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Reviews were included in this survey only if the indirect comparison was explicit in their titles and abstracts, and if they were indexed in PubMed. Thus we may have missed reports with indirect comparisons. Missed reviews may have been less explicit and less formal than included ones, therefore not mentioned in the abstract.

Empirical evidence on the validity of indirect and mixed treatment comparison is still limited and many questions remain unanswered. In addition, there is only limited empirical evidence to show that improved trial similarity is associated with improved validity of indirect and mixed treatment comparison.

What is already known on this topic

Indirect comparisons can be valid if some basic assumptions are fulfilled

The related but different methodological assumptions have not been clearly distinguished

What this study adds

Certain methodological problems may invalidate the results of evaluations using indirect comparison approaches

Understanding basic assumptions underlying indirect and mixed treatment comparison is crucial to resolve these problems

A framework can help clarify homogeneity, similarity, and consistency assumptions underlying adjusted indirect comparisons

Contributors: See bmj.com.

Funding: No specific funding was received for this study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:b1147

This article is an abridged version of a paper that was published on bmj.com. Cite this article as: BMJ 2009;338:b1147

References

- 1.Pocok SJ. Clinical trials: a practical approach. New York: Wiley, 1996.

- 2.Glenny AM, Altman DG, Song F, Sakarovitch C, Deeks JJ, D’Amico R, et al. Indirect comparisons of competing interventions. Health Technol Assess 2005;9:1-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ioannidis JP. Indirect comparisons: the mesh and mess of clinical trials. Lancet 2006;368:1470-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song F, Altman DG, Glenny AM, Deeks JJ. Validity of indirect comparison for estimating efficacy of competing interventions: empirical evidence from published meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;326:472-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, Walter SD. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:683-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song F, Harvey I, Lilford R. Adjusted indirect comparison may be less biased than direct comparison for evaluating new pharmaceutical interventions. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:455-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jorenby DE, Leischow SJ, Nides MA, Rennard SI, Johnston JA, Hughes AR, et al. A controlled trial of sustained-release bupropion, a nicotine patch, or both for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med 1999;340:685-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caldwell DM, Ades AE, Higgins JP. Simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments: combining direct and indirect evidence. BMJ 2005;331:897-900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins JP, Whitehead A. Borrowing strength from external trials in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 1996;15:2733-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song F, Glenny AM, Altman DG. Indirect comparison in evaluating relative efficacy illustrated by antimicrobial prophylaxis in colorectal surgery. Control Clin Trials 2000;21:488-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lumley T. Network meta-analysis for indirect treatment comparisons. Stat Med 2002;21:2313-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu G, Ades AE. Combination of direct and indirect evidence in mixed treatment comparisons. Stat Med 2004;23:3105-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]