Abstract

Tetracycline repressor (TetR)-controlled expression systems have recently been developed for mycobacteria and proven useful for the construction of conditional knockdown mutants and their analysis in vitro and during infections. However, even though these systems allowed tight regulation of some mycobacterial genes, they only showed limited or no phenotypic regulation for others. By adapting their codon usage to that of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome, we created tetR genes that mediate up to ∼50-fold better repression of reporter gene activities in Mycobacterium smegmatis and Mycobacterium bovis BCG. In addition to these repressors, for which anhydrotetracycline (atc) functions as an inducer of gene expression, we used codon-usage adaption and structure-based design to develop improved reverse TetRs, for which atc functions as a corepressor. The previously described reverse repressor TetR only functioned when expressed from a strong promoter on a multicopy plasmid. The new reverse TetRs silence target genes more efficiently and allowed complete phenotypic silencing of M. smegmatis secA1 with chromosomally integrated tetR genes.

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial genomes encode hundreds of genes whose functions yet remains to be discovered. For example, the genome of the important human pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis contains more than 1000 genes whose functions are unknown (1). Approximately 20% of these are likely required by M. tuberculosis to form colonies on agar plates (2). In this organism, genes of unknown functions are, thus, not only abundant but also frequently essential for growth. Reverse genetics allow to systematically associate genes of unknown function with specific biological processes and can provide an initial functional classification. Application of this approach to genes essential for in vitro growth requires the construction of conditional mutants, because bacteria, in which a growth essential gene has been constitutively inactivated, cannot be obtained in amounts sufficient for further analyses. A straightforward method for obtaining conditional mutants is to replace the native promoter of a target gene with a tightly regulated promoter whose activity can be controlled experimentally (3–7).

The promoters that initiate transcription of tetracycline (tc) efflux pump encoding genes in Gram-negative bacteria are among the most tightly regulated bacterial promoters. High-level expression of a tc efflux pump is toxic in the absence of tc and transcription of the encoding gene, tetA, is only induced in the presence of the antibiotic (8,9). This regulation is controlled by a single transcriptional repressor, TetR, which binds to two tet operators (tetOs) in the tetA promoter. Binding of TetR prevents access of RNA polymerase to the promoter and inhibits transcription initiation. Once tc enters the cell it binds to TetR, induces a conformational change that forces the helix–turn–helix (HTH) motifs of TetR into positions that interfere with operator binding and releases the repressor from tetO. The affinity of tc to TetR is ∼1000-fold higher than tc's affinity to the ribosomes. Expression of tetA is, therefore, induced at tc concentrations far below those that inhibit translation (10).

TetRs and tetO-containing promoters have been used to regulate gene expression in Gram-negative (11,12), Gram-positive (13–15) and acid-fast bacteria (4,16–18). In most of these systems, expression of the target gene is induced by adding tc to the culture. While useful for many experiments, these systems are not ideal if the goal is to study the consequences of gene silencing, in part, because the removal of tc is difficult in some experimental settings (e.g. during hypoxia).

We recently constructed a regulated mycobacterial expression system that permits to silence a gene by the addition of atc (5,7). This system makes use of a TetR mutant, TetR r1.7 (19), which harbors three amino acid changes (E15A, L17G, and L25V) in the DNA-binding domain. These mutations reverse the allosteric response of TetR to binding of tc: whereas binding of tc to wt TetR causes the repressor to dissociate from DNA, binding of tc to TetR r1.7 (or other reverse TetRs) causes the repressor to bind to DNA. Repression by TetR r1.7 was efficient enough to study the consequences of silencing secA1 in Mycobacterium smegmatis (7) and prcBA in M. tuberculosis (5). However, repression by TetR r1.7 requires high-level TetR expression and only occurs if (i) the tetR gene is transcribed by the strong mycobacterial promoter Psmyc and (ii) is located on a multicopy plasmid. Even under these conditions repression by TetR r1.7 with atc is not as efficient as repression by wt TetR without atc (7) so that only some mycobacterial genes can be silenced to the extent necessary to reveal the consequences of their inactivation (unpublished data).

The wt TetR used by us to control gene expression in mycobacteria stems from the transposon Tn10, which encodes the so-called tet(B) tc resistance determinant (20). In contrast, TetR r1.7 was derived from a chimeric tetR(BD) gene in which the protein core is encoded by the tetR gene of the tet(D) resistance determinant (19). Here, we demonstrate that the low repression efficiency of TetR r1.7 in mycobacteria is in part due to low expression of some tetR(BD) genes and describe the construction of new wt TetRs and reverse TetRs that allow more efficient gene silencing in mycobacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, bacterial strains, media, reagents and molecular biology techniques

Bacteria and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmids were constructed using standard procedures (details available upon request). Mycobacteria were grown at 37°C on Difco 7H11 agar or in Difco Middelbrook 7H9 broth with 0.2% v/v glycerol and 0.05% v/v Tween 80. For Mycobacterium bovis BCG the 7H9 medium was supplemented with ADN enrichment (0.5% BSA, 0.2% dextrose, 0.085% NaCl). Escherichia coli was grown in Luria-Bertani broth (LB). Antibiotics were added, where appropriate, at 50 μg/ml for mycobacteria and 200 μg/ml for E. coli (hygromycin B, Calbiochem) and 15 µg/ml for mycobacteria and 30 µg/ml for E. coli (kanamycin A, Sigma). Atc was obtained from Sigma. Preparation of competent cells and electroporations were performed as described (4).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strain | ||

| M. smegmatis mc2155 | Electroporation-proficient M. smegmatis | (26) |

| M. smegmatis MSE10 | Hygr mc2155 derivative in which secA1 is controlled by Pmyc1tetO. | (7) |

| M. bovis BCG | Mycobacterium bovis BCG | ATCC #35734 |

| E. coli DH5α | F− φ80dlacZΔ(lacZ)M15 Δ(lacZYA-argF) U169 deoR recA1 endA1hsdR17 (r−Km+K) phoA supE44 λ− thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Gibco, BRL |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMS2 | Hygr, pAL5000 and ColE1 origins, multiple cloning site | (23) |

| pMV306Km | Kmr, ColE1 origin, intL5, attPL5, integrates at attBL5 site | (27) |

| pTT-P1A | Kmr, Ampr, ColE1 origin, inttweety, attPtweety, integrates at attBtweety site | (24) |

| pTE-4M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR(BD)E15A-L17G-L25V | (7) |

| pTC-0X-1L | pMV306 derivative, Pmyc1tetO-lacZ | (7) |

| pTE-1M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR(B) | (7) |

| pTE-mcs | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, alternative multiple cloning site containing unique restriction sites for ClaI, PacI, PmeI and NotI | This study |

| pTC-mcs | pMV306K derivative, Kmr, alternative multiple cloning site containing unique restriction sites for MluI, NotI, PmeI, PacI, ClaI and SalI | This study |

| pTE-2M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR(Bsyn1–50) | This study |

| pTE-10M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR(Bsyn1–207) | This study |

| pTE-9M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR(BD) | This study |

| pTE-11M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR(BDsyn1-50) | This study |

| pTE-12M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR(BDsyn1-208) | This study |

| pTE-15M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR(BDsyn1-208)E15A-L17G-L25V | This study |

| pTE-16M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR(BDsyn1-208)L17G | This study |

| pTE-19M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR(BDsyn1-208)A56P-V57L-E58V | This study |

| pTE-20M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR(BDsyn1-208)R94P-V99E | This study |

| pTE-22M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR(Bsyn1-207)E15A-L17G-L25V | This study |

| pTE-23M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR#23 | This study |

| pTE-24M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR#24 | This study |

| pTE-25M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR#25 | This study |

| pTE-27M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR#27 | This study |

| pTE-28M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR #28 | This study |

| pTE-29M-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Pimyc-tetR#29 | This study |

| pTE-15S15-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Psmyc-tetR(BDsyn1-208)E15A-L17G-L25V | This study |

| pTE-22 S15-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Psmyc-tetR(Bsyn1-207)E15A-L17G-L25V | This study |

| pTE-23 S15-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Psmyc-tetR#23 | This study |

| pTE-24 S15-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Psmyc-tetR#24 | This study |

| pTE-25 S15-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Psmyc-tetR#25 | This study |

| pTE-27 S15-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Psmyc-tetR#27 | This study |

| pTE-28 S15-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Psmyc-tetR#28 | This study |

| pTE-29 S15-0X | pMS2 derivative, Hygr, Psmyc-tetR#29 | This study |

| pTC-1M-1L | pMV306 derivative, Kmr, Pmyc1tetO-lacZ, Pimyc-tetR(B) | This study |

| pTC-2M-1L | pMV306 derivative, Kmr, Pmyc1tetO-lacZ, Pimyc-tetR(Bsyn1–50) | This study |

| pTC-10M-1L | pMV306 derivative, Kmr, Pmyc1tetO-lacZ, Pimyc-tetR (Bsyn1–207) | This study |

| pTC-4S15-0X | pMV306 derivative, Kmr, Psmyc-tetR(BD)E15A-L17G-L25V | This study |

| pTC-15S15-0X | pMV306 derivative, Kmr, Psmyc-tetR(BDsyn1–208)E15A-L17G-L25V | This study |

| pTC-27S15-0X | pMV306 derivative, Kmr, Psmyc-tetR#28 | This study |

| pTC-28S15-0X | pMV306 derivative, Kmr, Psmyc-tetR #28 | This study |

| pTT-P1A-S1L | pTT-P1A derivative, Strepr, Pmyc1tetO-lacZ | This study |

β-Galactosidase assays

Repression by TetRs and induction with atc was determined after transformation of M. smegmatis or M. bovis BCG with the appropriate plasmids. From each transformation three single colonies were inoculated into 2 ml of 7H9 media containing the antibiotics required to select for plasmid maintenance. After shaking at 37°C for 44–48 h (M. smegmatis) or 8–10 days (M. bovis BCG), bacteria were diluted 100-fold in 1-ml fresh media contained in 96-square-well plates (Beckman). After shaking at 37°C for 20–24 h (M. smegmatis) or 3–4 days (M. bovis BCG) optical densities were measured at 580 nm. In a black 96-well plate, 100-μl bacteria were then mixed with C2FDG (Invitrogen) to a final concentration of 30 μM C2FDG (21). The plate was incubated in the dark for 3 h at 30°C and fluorescence was measured at 515 nm after excitation at 485 nm using a spectramax M2 plate reader (Molecular Devices). Fluorescence intensities were normalized to cell density and reported as relative fluorescence units (RFUs). All measurements were repeated at least twice.

Preparation of protein lysates

Mycobacteria were harvested by centrifugation and washed with PBS (128 mM NaCl, 8.5 mM Na2HPO4, 3.5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4). Cells were resuspended in PBS supplemented with Complete™ protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science), and 0.5 ml of the suspension was transferred into a screw-cap vial containing ∼250 μl of 0.1 mm Zirconia/Silica beads (BioSpec). Cells were broken by shaking in a Precellys 24 homogenizer (Bertin Technologies) at 6500 r.p.m. for 20 s three times, with 5-min incubations on ice in between. Total lysates were obtained after removing beads and unbroken cells by centrifugation at 13 000 r.p.m (13 793 g) for 1 min. For detection of TetR, total lysates were centrifuged at 13 000 r.p.m for 45 min at 4°C in an Eppendorf 5417R centrifuge to separate the soluble (cytoplasm) and insoluble (cell wall) fractions.

Western blot analysis

Cell lysates were mixed with an SDS- and β-mercaptoethanol-containing loading buffer and incubated at 95°C for 5 min. Proteins were separated by 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and transferred to a Protran BA83 nitrocellulose membrane (Whatman) in an ice cooled container with a constant current of 120 mA in transfer buffer (192 mM glycine, 25 mM Tris, 20% v/v methanol) for 2 h. A mixture of hybridoma supernatant containing monoclonal murine antibodies mixed 1:1 with Odyssey® blocking buffer was used as primary antibodies. For detection of the loading control dihydrolipoamide acyltransferase (DlaT) a polyclonal anti-DlaT serum was used at a 1:10 000 dilution. Odyssey® Infrared Imaging System was used for detection.

Molecular modeling

The software DS Viewer Pro and Swiss Pdb viewer was used to determine amino acid residues contacting mutated amino acid residues in various reverse TetRs on the basis of the tetO-bound TetR structure PDB#1qpi (22).

RESULTS

The impact of tetR codon usage on gene silencing by wt TetRs in M. smegmatis and M. bovis BCG

Expression of TetRs in mycobacteria might be limited by the inefficient translation of codons within their genes that rarely occur in mycobacterial genes. To test this, we constructed four tetR genes in which codons that occur infrequently in the M. tuberculosis genome were mutated to alternative codons, which encode the same amino acid but occur frequently in the M. tuberculosis genome. In the first of these genes, tetR(Bsyn1–50), the nucleotides encoding the DNA-binding domain of TetR (nucleotides 1–150) were derived from a synthetic DNA fragment in which codon usage was adapted to that of the M. tuberculosis genome. The corresponding gene encoding the chimeric TetR(BD) protein was named tetR(BDsyn1–50). The 3′ fragments of both, tetR(Bsyn1–50) and tetR(BDsyn1–50), were from the original tetR(B) and tetR(D) genes. The remaining two tetR variants, tetR(Bsyn1–207) and tetR(BDsyn1–208), were entirely derived from synthetic DNAs in which all amino acids were encoded by codons that occur frequently in the M. tuberculosis genome.

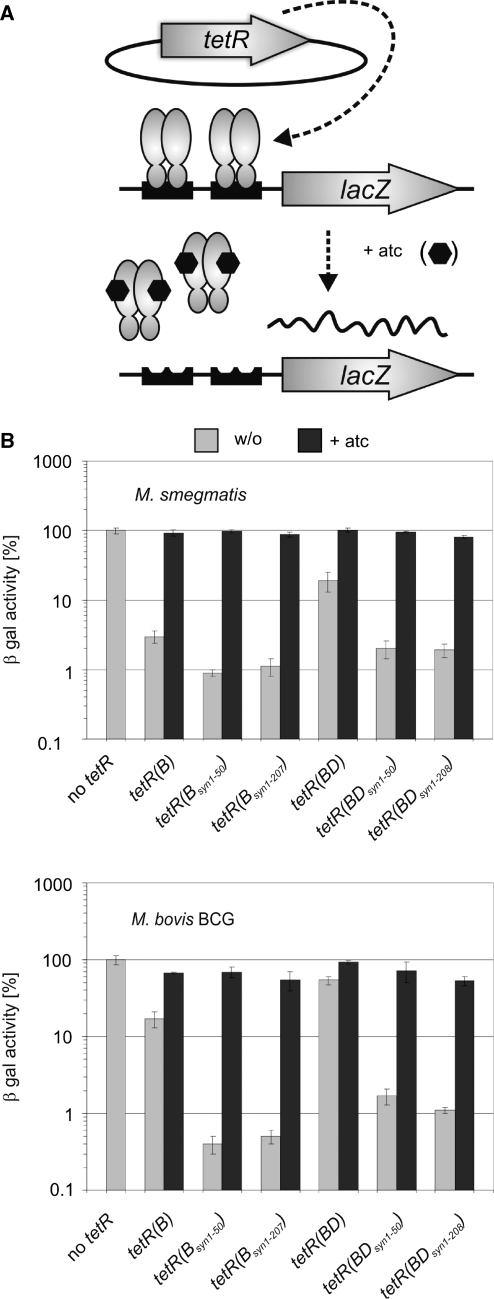

We first analyzed the tetR(B) genes in M. smegmatis Pmyc1tetO-lacZL5, which contains the Pmyc1tetO-lacZ expression cassette (7) integrated into the chromosomal attachment site of the mycobacteriophage L5. Mycobacterium smegmatis Pmyc1tetO-lacZL5 displayed a β-galactosidase activity of ∼8000 relative fluorescence units (RFUs). The limit of β-galactosidase detection was at ∼70 RFUs. Episomally replicating plasmids containing tetR downstream of the constitutive promoter Pimyc (23) were used to express each TetR variant (Figure 1A). Transformation of M. smegmatis Pmyc1tetO-lacZL5 with the Pimyc-tetR(B) plasmid reduced β-galactosidase activity to ∼3% of that of M. smegmatis Pmyc1tetO-lacZL5 without tetR (Figure 1B). Strains containing the two synthetic tetR(B) genes, Pimyc-tetR(Bsyn1–50) or Pimyc-tetR(Bsyn1–207) displayed β-galactosidase activities of ∼1%. In M. bovis BCG Pmyc1tetO-lacZL5 the original tetR(B) gene reduced β-galactosidase activity to 17% of the activity of M. bovis BCG Pmyc1tetO-lacZL5 without tetR. In contrast, the two synthetic tetR(B) genes both caused repression to <1%.

Figure 1.

Impact of tetR codon usage adaptation on repression of chromosomally encoded β-galactosidase activities by episomally encoded wt TetRs. (A) Genetic organization of the assay strains. The Pmyc1tetO-lacZ reporter gene cassette was integrated into the mycobacteriophage L5 attachment site. The Pimyc-tetR genes were located on episomally replicating plasmids. Binding of TetR to tetOs in the absence of atc caused repression of Pmyc1tetO. Symbols: TetRs, gray ovals; tetOs, black boxes; atc, black hexagons. (B) β-Galactosidase activities (β-gal). Expressed TetR variants are identified underneath the graph. Values were normalized to the β-galactosidase activity measured in the absence of TetR, which was set to 100%. Bars represent averages of three measurements and are representative of at least two independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

We then measured repression of β-galactosidase activities by the three tetR(BD) genes in M. smegmatis and M. bovis BCG. Expression of TetR(B/D) by Pimyc-tetR(BD) reduced β-galactosidase activities to ∼20% and ∼50%, respectively, of M. smegmatis and M. bovis BCG without tetR (Figure 1B, gray bars). In contrast, expression of TetR(B/D) by the synthetic tetR(BD) genes repressed β-galactosidase activities to levels between 1 and 2%. All strains exhibited between 53 and 102% β-galactosidase activities in the presence of 300 ng/ml atc (Figure 1B, black bars).

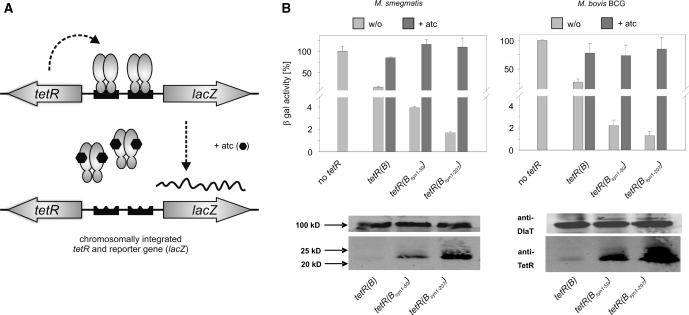

Next, we determined if the two synthetic tetR(B) genes, which repressed expression of β-galactosidase more efficiently than the corresponding tetR(B/D) genes, also allowed efficient gene silencing when integrated into the chromosome. For this, we cloned each tetR(B) gene together with the reporter gene cassette, Pmyc1tetO-lacZ, into one integrative plasmid (Figure 2A). In both, M. smegmatis and M. bovis BCG, repression was most efficient with tetR(Bsyn1–207) and least efficient with tetR(B) (Figure 2B). Repression correlated well with protein steady-state levels, which were highest with tetR(Bsyn1–207) and lowest with tetR(B) (Figure 2B). In summary, these findings demonstrated that repression by wt TetRs in M. smegmatis and M. bovis BCG was significantly improved by adapting the codon usage of tetR to that of mycobacteria and that tetR(B) genes mediated more efficient repression than the corresponding tetR(BD) genes.

Figure 2.

Impact of tetR codon usage adaptation on repression of chromosomally encoded β-galactosidase activities by chromosomally encoded wt TetRs. (A) Genetic organization of the assay strains. Plasmids containing both, the Pmyc1tetO-lacZ reporter gene cassette and the Psmyc-tetR genes were integrated into the chromosome via the L5 attachement site. Symbols: TetRs, gray ovals; tetOs, black boxes; atc, black hexagons. (B) β-galactosidase activities (β-gal) and steady-state TetR protein levels detected by a monoclonal anti-TetR antibody. Expressed TetR variants are identified underneath the bar graph. Values were normalized to the β-galactosidase activity measured in the absence of TetR, which was set to 100%. Bars represent averages of three measurements and are representative of at least two independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations. Western blots are shown below the respective bar graphs. The dihydrolipoamide acyltransferase (DlaT) signal was used as a loading control and detected by a polyclonal anti-DlaT antibody.

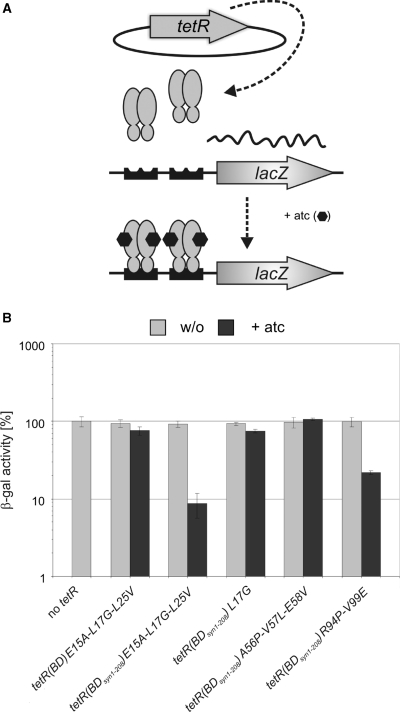

The impact of tetR codon usage on gene silencing by reverse TetRs in M. smegmatis

Reverse TetRs allow gene silencing by adding atc instead of removing atc (Figure 3A), which is advantageous under conditions were atc cannot be easily depleted (e.g. during hypoxia). TetR r1.7, a reverse TetR(BD) variant that contained three mutations in its DNA-binding domain (E15A, L17G and L25V), allowed atc-induced gene silencing in both, M. smegmatis (7) and M. tuberculosis (5). However, repression by TetR r1.7 was less efficient than repression by wt TetR (7). To improve gene silencing by reverse TetRs we first mutated the tetR(BDsyn1–208) gene to encode TetR r1.7; the resulting gene was named tetR(BDsyn1–208)E15A-L17G-L25V (in contrast to tetR(BD)E15A-L17G-L25V, the noncodon usage adapted gene encoding TetR r1.7) Transformation of M. smegmatis Pmyc1tetO-lacZL5 with an episomally replicating plasmid containing Pimyc-tetR(BDsyn1–208)E15A-L17G-L25V reduced β-galactosidase activity to ∼6% of the strain without tetR in the presence of atc (Figure 3B). No repression was observed in the absence of atc. As had been observed previously (7), Pimyc-tetR(BD)E15A-L17G-L25V did not change β-galactosidase of M. smegmatis. We also constructed and analyzed three additional tetR(BDsyn1–208) derivates which all encoded reverse TetRs that function efficiently in E. coli (19). However, the most efficient of these repressors reduced β-galactosidase activity only to 22% in M. smegmatis (Figure 3B) and none of them caused any repression if expressed by the original, noncodon usage adapted, tetR(BD) genes. These experiments demonstrated that codon-usage adaptation improved gene silencing by TetR r1.7 and that among the four TetRs evaluated, TetR r1.7 was most efficient in M. smegmatis.

Figure 3.

Impact of tetR codon usage adaptation on repression of chromosomally encoded β-galactosidase activities by episomally encoded reverse TetRs. (A) Genetic organization of the assay strains. The Pmyc1tetO-lacZ reporter gene cassette was integrated into the mycobacteriophage L5 attachment site. The Pimyc-tetR genes were located on episomally replicating plasmids. Binding of revTetR to tetOs in the presence of atc caused repression of Pmyc1tetO. Symbols: TetRs, gray ovals; tetOs, black boxes; atc, black hexagons. (B) β-galactosidase activities (β-gal). Expressed TetR variants are identified underneath the bar graph. Values were normalized to the β-galactosidase activity measured in the absence of TetR, which was set to 100%. Bars represent averages of three measurements and are representative of at least two independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

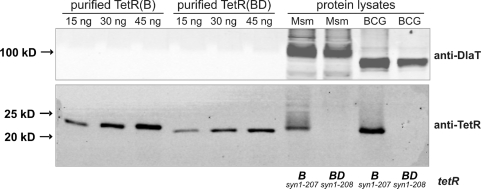

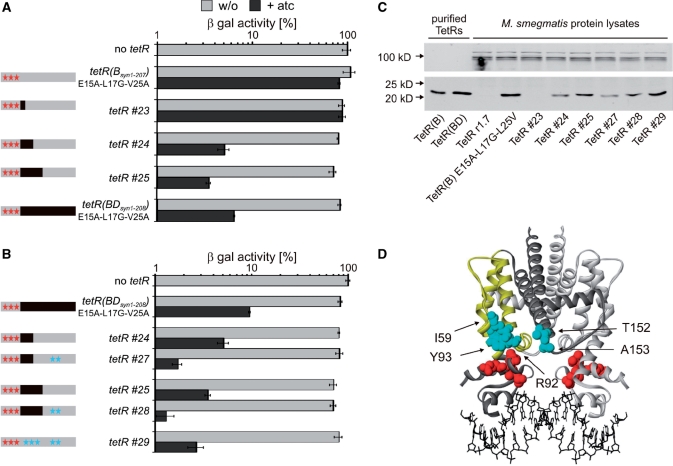

Construction of improved reverse TetRs for gene silencing in mycobacteria

All reverse TetRs analyzed so far were originally isolated in genetic screens using mutants of tetR(BD) (19). Unfortunately, repression of lacZ by TetR(BD) in M. smegmatis and M. bovis BCG was less efficient than repression by TetR(B) (Figure 1B). To determine if the difference in repression by TetR(B) and TetR(BD) might be caused by different protein steady state levels, lysates from M. smegmatis and M. bovis BCG containing Pimyc-tetR(Bsyn1–207) or Pimyc-tetR(BDsyn1–208) were analyzed by Western blots. Strong signals were detected for TetR(B) in lysates from both mycobacteria but the steady state levels of TetR(BD) were below the level of detection (Figure 4). This suggested that a reverse TetR derived from TetR(B) might be more efficient in mycobacteria than those derived from TetR(BD). However, so far no reverse TetR(B) variant had been isolated.

Figure 4.

Comparison of TetR steady state levels in M. smegmatis and M. bovis BCG containing tetR(B)syn1–207 or tetR(BD)syn1–208. Protein lysates were from M. smegmatis (labeled ‘Msm’) and M. bovis BCG (labeled ‘BCG’) containing episomally replicating Pimyc-tetR plasmids. A monoclonal anti-TetR antibody recognizing an epitope within the DNA-binding region of TetR was used to detect purified TetR as well as TetR in protein lysates from M. smegmatis and M. bovis BCG. The DlaT signal was used as a loading control and detected by a polyclonal anti-DlaT antibody.

We first examined if a reverse TetR(B) could be constructed by introducing the amino acid exchanges present in TetR r1.7. Expression of this repressor using an episomally replicating plasmid containing Pimyc-tetR(Bsyn1–207)E15A-L17G-L25V did not affect the β-galactosidase activity of M. smegmatis Pmyc1tetO-lacZL5 with or without atc (Figure 5A). When expressed by the strong promoter Psmyc, this repressor reduced β-galactosidase activity ∼5-fold in the presence of atc (data not shown). No repression was observed in the absence of atc. TetR(Bsyn1-207)E15A-L17G-L25V thus encoded a less efficient reverse TetR than the corresponding tetR(BDsyn1–208) gene (tetR(BDsyn1–208)E15A-L17G-L25V, Figure 3B) even though the steady-state level of the TetR(B) protein was higher than that of the TetR(BD) protein (Figure 5C). This suggested that additional TetR(B) amino acids needed to be replaced by the corresponding TetR(D) amino acids to not only achieve an increase in protein expression but also generate an efficient reverse phenotype.

Figure 5.

Analysis of reverse TetR chimeras in M. smegmatis. (A) β-galactosidase activities (β-gal). Expressed TetR variants are specified left of the bar graph. In the schemas on the left, gray and black rectangles indicate sequences derived from tetR(B) and tetR(D) respectively. Red stars indicate the location of mutation causing the reverse phenotype of TetR r1.7. Blue stars indicate TetR(B) to TetR(D) mutations. β-Gal values were normalized to the β-galactosidase activity measured in the absence of TetR, which was set to 100%. Bars represent averages of three measurements and are representative of at least two independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) β-galactosidase activities (β-gal). As described for (A). (C) Western blots. Protein lysates were prepared from M. smegmatis expressing TetR variants encoded by episomally replicating plasmids. TetR was detected by a monoclonal anti-TetR antibody (lower panel) and the dihydrolipoamide acyltransferase (DlaT) signal was used as a loading control and detected by a polyclonal anti-DlaT antibody (upper panel). (D) Structure of tetO-bound TetR(D) (22). The two monomers are shown in light and dark gray. The side chains of the amino acids that are mutated in and cause the reverse phenotype of TetR r1.7 are shown in red. In the dark gray monomer helices 4 to 7 are drawn in yellow. Side chains that are different in TetR(B) and TetR(D) and within a radius of 15 Å to positions 15, 17 and 25 are shown in light blue (for clarity sake only within one monomer).

We hypothesized that the TetR(D) amino acids required for an efficient reverse phenotype should be located in close proximity to the amino acids at positions 15, 17 and 25 in the crystal structure of the TetR(D)–tetO complex. Most residues that are (i) different in TetR(B) and TetR(D) and (ii) located in the vicinity of the amino acids at positions 15, 17 and 25 are in alpha helices four, five and the N-terminal and C-terminal regions of helices seven and eight, respectively (α4, α5, α7, α8) (Figure 5D). Using the fully codon usage adapted tetR(Bsyn1–207) and tetR(BDsyn1–208) genes, we constructed three derivatives of TetR(B)E15A-L17G-L25V in which all amino acids located in α4 (TetR#23), α4-α5 (TetR#24) or α4-α7 (TetR#25) were identical to those of TetR(D) (Figure 5A). Analysis of these TetRs in M. smegmatis demonstrated that repression in the presence of atc increased with the number of TetR(D) residues introduced into TetR(B)E15A-L17G-L25V (Figure 5A). We next introduced two additional TetR(D) amino acids—T152 and A153, which are located at the C-terminus of helix 8 and proximal to amino acid L17 and L25 in the TetR(D)–tetO complex (distance Cβ-Cβ < 15 Å) (Figure 5D)—into TetR#24 and #25. The resulting repressors were named TetR#27 and TetR#28, respectively (Figure 5B). TetR#27 and TetR#28 both repressed the β-galactosidase activity of M. smegmatis Pmyc1tetO-lacZL5 to <2% of that of the strain without tetR achieving 3-fold better repression compared to TetR#24 and TetR#25. None of the repressors reduced β-galactosidase activities in the absence of atc.

TetR#27 and TetR#28 both contained TetR(D) amino acids at position that were not in close proximity of the TetR DNA-binding domain (e.g. amino acids located in the loop connecting α4 and α5) (Figure 5D). We therefore constructed one additional TetR variant, named TetR#29, in which those amino acids that are located within a radius of 15 Å of residues E15, L17 or L25 were mutated to the corresponding TetR(D) amino acids, namely M59I, S92R, H93Y, Q152T and V153A, as well as I57V and D61A which are located within a radius between 15 and 20 Å. Repression by TetR#29 was slightly less efficient than that achieved by TetR#27 and #28 (Figure 5B).

Western blots revealed that the lack of repression by TetR#23 correlated with its low-steady-state level (which was below the level of detection) (Figure 5C). The differences in repression by the other TetR variants, however, cannot be explained by differences in their expression. For example, the steady-state level of TetR#27 is lower than that of TetR#29 but TetR#27 is the more efficient repressor. This suggests that some or all of the TetR(D) amino acids present in TetR#27 and missing in TetR#29 are involved in the atc-induced allosteric transition required for repression. In summary, this work led to the construction of more efficient reverse TetRs for mycobacteria and identified regions in the TetR protein core required for efficient tetO binding.

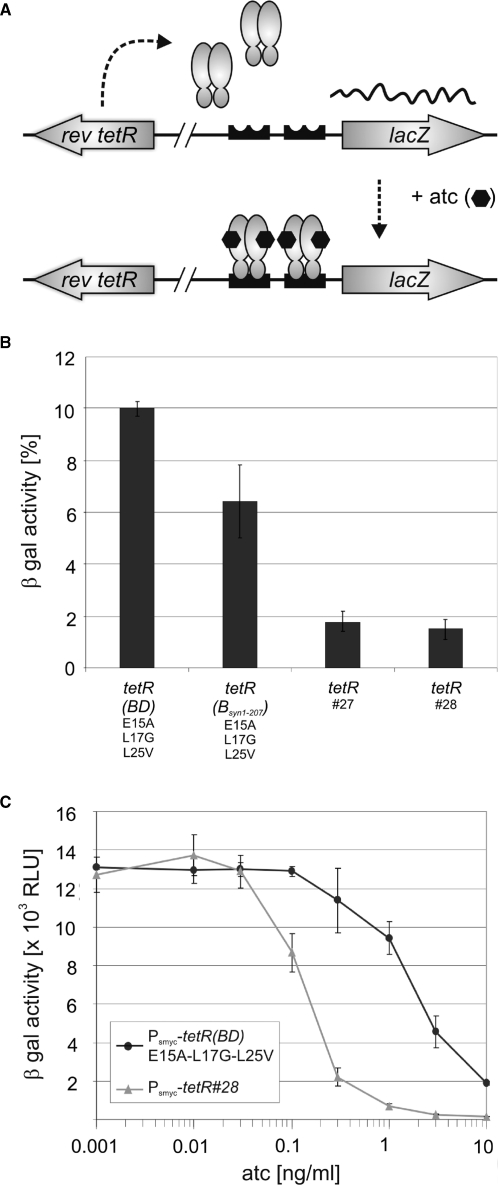

Gene silencing by chromosomally integrated reverse tetRs

A limitation of the previously described TetR r1.7 is the requirement for expression by a multicopy plasmid to achieve efficient repression in mycobacteria. We tested if the new reverse TetRs would allow the repression of a target gene if expressed by a chromosomally integrated tetR. For this we cloned four tetRs, the original tetR(BD)E15A-L17G-L25V, tetR(BDsyn1–208)E15A-L17G-L25V, tetR#27 and tetR#28, into expression plasmids that can integrate in the chromosomal attachment site of the mycobacteriophage L5. These constructs were evaluated in M. smegmatis Pmyc1tetO-lacZtweety, which contained the lacZ reporter integrated into the chromosomal attachment site of the mycobacteriophage tweety (Figure 6A) (24). Chromosomal expression of TetR#27 and #28 reduced the β-galactosidase of M. smegmatis Pmyc1tetO-lacZtweety to <2% (Figure 6B). In contrast β-galactosidase activities of the strains containing tetR(BD)E15A-L17G-L25V or tetR(BDsyn1–208)E15A-L17G-L25V, both of which encode TetR r1.7, were 10% and 6%, respectively. A comparison of repression by TetR r1.7 and TetR#28 with different atc concentrations demonstrated that TetR#28 not only caused more efficient repression at high atc concentrations but also was more responsive to low levels of atc.

Figure 6.

Repression of lacZ by chromosomally encoded reverse TetRs. (A) Genetic organization of the assay strains. The Pmyc1tetO-lacZ reporter gene cassette was integrated into the mycobacteriophage tweety attachment site. The Psmyc-tetR genes were integrated into the mycobacteriophage L5 attachment site. Symbols: TetRs, gray ovals; tetOs, black boxes; atc, black hexagons. (B) β-galactosidase activities (β-gal) with 300 ng/ml atc. Expressed TetR variants are specified below the bar graph. β-gal values were normalized to the β-galactosidase activity measured in the absence of TetR, which was set to 100%. Bars represent averages of three measurements and are representative of at least two independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (C) β-galactosidase activities (β-gal) with different atc concentrations. Black circles and gray triangles represent data from M. smegmatis containing Psmyc-tetR(BD)E15A-L17G-L25V and Psmyc-tetR#28, respectively.

To confirm these results by an independent test, we transformed M. smegmatis MSE10 with chromosomally integrating plasmids containing Psmyc-tetR(BD)E15A-L17G-L25V, Psmyc-tetR(BDsyn1–208)E15A-L17G-L25V, Psmyc-tetR#27, or Psmyc-tetR#28. M. smegmatis MSE10 is a mutant in which the native promoter of the essential secA1 gene has been replaced by Pmyc1tetO so that transcription of secA1 and growth of M. smegmatis can be controlled with TetRs (7). The outgrowth of these transformations was spread on selective 7H11 media containing either no or 300 ng/ml atc and pictures were taken after 3 days of incubation at 37°C. Expression of TetR r1.7 by a chromosomally integrated tetR(BD)E15A-L17G-L25V did not affect growth of this M. smegmatis MSE10 (Supplementary Figure 2). Expression of TetR r1.7 using a chromosomally integrated copy of the codon usage adapted tetR(BDsyn1-208)E15A-L17G-L25V gene did decrease but not entirely suppress growth in the presence of atc. In contrast, no growth on atc plates was observed for the strains containing chromosomally integrated genes encoding TetR#27 or #28. All strains grew similarly on plates without atc. In summary these experiments demonstrated that the new reverse TetRs show significantly improved repression and atc responsiveness.

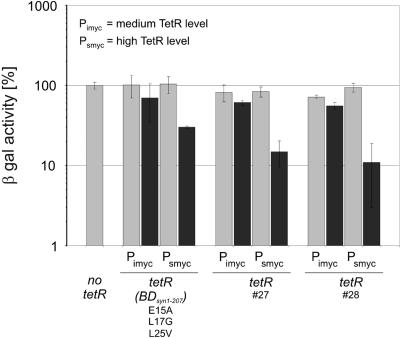

Analysis of selected reverse TetRs in M. bovis BCG

To determine if tetR#27 and tetR#28 also mediated more efficient repression in slow growing mycobacteria we compared them with tetR(BDsyn1–208)E15A-L17G-L25V in M. bovis BCG containing the Pmyc1tetO-lacZ reporter integrated into the mycobacteriophage L5 attachment site. The weak promoter Pimyc and the strong promoter Psmyc were used to express each tetR gene. When expressed from Pimyc, none of the TetRs caused repression of β-galactosidase activity (Figure 7). However, M. bovis BCG transformed with episomally replicating plasmids containing tetR(BDsyn1–208)E15A-L17G-L25V, tetR#27 or tetR#28 downstream of Psmyc, displayed β-galactosidase activities that were repressed by a factor of 3, 7 or 10, respectively. This repression was only observed in the presence of atc. TetR#27 and TetR#28, thus, also function more efficiently than TetR r1.7 in M. bovis BCG.

Figure 7.

Analysis of reverse TetRs in M. bovis BCG. TetR-mediated repression was measured using the chromosomally integrated Pmyc1tetO-lacZ reporter. TetR variants were expressed from episomally replicating plasmids. β-galactosidase activities were analyzed in the absence (light gray bars) and presence of 300 ng/ml atc (dark gray bars) using a fluorescent-based assay as explained in ‘Materials and methods’ sections. Obtained values were normalized to the β-galactosidase activity measured in the absence of TetR, which was set to 100%. Bars represent averages of three measurements and are representative of at least two independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

The phenotypes of loss-of-function mutants greatly contributed to our understanding of the biology of mycobacteria (25). Constitutive loss-of-function mutants are, however, of limited value for the analysis of genes that are essential for growth in vitro. The inability to recover loss-of-function mutants can identify a gene as essential for in vitro growth. However, the underlying mechanism may remain unknown. For example, this is true for approximately one-third of the M. tuberculosis genes required for optimal growth on agar plates (2). It also remains unknown if a gene required for growth on agar plates is required for growth in other environments or is required for survival under conditions that suppress replication but permit survival (e.g. during starvation). One approach that can overcome the limitations of constitutive loss-of-function mutants is to generate conditional loss-of-function mutants in which transcription of the only functional copy of the target gene can be repressed. To allow this in mycobacteria, several regulated mycobacterial expression systems that make use of TetRs from E. coli or Corynebacterium glutamicum have recently been constructed (4,16–18). Here we described the design of new TetRs that were derived from the tetR(B) and tetR(D) repressors and improved to regulate gene expression in mycobacteria. We first analyzed repression mediated by wt tetR(B) and tetR(BD) genes whose codon usage was either that of the original genes or adapted to that of the M. tuberculosis genome. Codon usage adaptation improved repression between ∼3-fold (episomal expression of tetR(B) in M. smegmatis) and ∼50-fold (episomal expression of tetR(BD) in M. bovis BCG) (Figure 1). This improvement is a consequence of increased TetR steady-state levels (Figure 2) most likely caused by more efficient translation of the codon usage adapted mRNAs. Importantly, the increased TetR steady-state levels did not interfere with induction by atc (Figures 1 and 2).

Codon-usage adaptation of the gene encoding the reverse repressor TetR r1.7 also improved repression (Figure 3). However, even after codon-usage adaptation repression was not as efficient as for wt TetR. Three repressors containing other mutations, all of which caused reverse TetR phenotypes in E. coli, were analyzed but none were more efficient than TetR r1.7 (Figure 3). To improve repression, we next used a strategy that was based on (i) the observation that TetR(B) accumulated to higher steady-state levels in mycobacteria than TetR(BD) (Figure 4) and (ii) the fact that all reverse TetRs that had been tested so far were TetR(BD) mutants. The reverse phenotype of TetR r1.7 is caused by three mutations (E15A, L17G and L25V) within the DNA-binding domain (Figure 5D). Introduction of these mutations into the codon usage adapted tetR(B) resulted in a reverse TetR(B) (data not shown). However, repression by TetR(B)E15A-L7G-L25V was less efficient than by TetR r1.7 even though the steady-state levels were higher for TetR(B)E15A-L17G-L25V than for TetR r1.7 (Figure 5C). This suggested an interference of the TetR(B) protein core with the allosteric change required for efficient repression by the reverse (TetR-atc) complex. We reasoned that the amino acids responsible for this interference should be located close to amino acids 15, 17 and/or 25 in the TetR-tetO crystal structure (Figure 5D). To test this hypothesis we constructed several derivatives of TetR(B)E15A-L17G-L25V in which these TetR(B) amino acids were exchanged to the respective TetR(D) amino acids.

Amino acids that are different in TetR(B) and TetR(D) and within a radius of 15 Å (distance Cβ-Cβ) to amino acids 15, 17 and/or 25 are located within the C-terminal region of α4, the turn between α5 and α6, and the C-terminus of α8 (Figure 5D). Exchanging all amino acids located in α4–α7 to the respective TetR(D) residues led to a repressor, TetR#25, which caused an ∼25-fold repression in M. smegmatis. The steady-state protein level of TetR#25 was higher than that of TetR r1.7 but lower than that of TetR(B)E15A-L17G-L25V. Its increased activity was, thus, the result of achieving high expression without interfering with atc induced tetO binding. Repressors that only contained the TetR(D) residues located in α4 (TetR#23) or α4 and α5 (TetR#24) were less well expressed and less active (Figure 5). Mutating the amino acids 152 and 153 to the respective TetR(D) residues within TetR#25 (leading to TetR#28) further improved repression to ∼70-fold. A similar improvement was observed by introducing these mutations into TetR#24 (leading to TetR#27). In both cases, the mutations at positions 152 and 153 hardly affected TetR protein levels, suggesting that the improved repression properties are due to an improved atc induced tetO-binding caused by these mutations. TetR#28 contained a total of 25 TetR(B) to TetR(D) mutations only five of which affected amino acids located close to amino acids 15, 17 and/or 25. However, a TetR(B)E15A-L17G-L25V mutant in which only these five amino acids plus two additional positions in helix 4 were mutated (TetR#29) was a less efficient repressor than TetR#27 and TetR#28 even though its steady-state level was higher (Figure 5C). Some or all of the mutations included in TetR#27/28 thus likely contribute to atc induced tetO binding.

The previously described TetR r1.7 did not permit gene silencing when expressed by a chromosomally integrated gene. In contrast, TetR#27 and TetR#28 caused ∼50-fold repression of β-galactosidase activities in M. smegmatis when expressed by a chromosomally integrated gene (Figure 6B) and caused efficient repression even at low atc concentrations (Figure 6C). The new reverse TetRs furthermore allowed efficient silencing of the essential secA1 gene in a conditional M. smegmatis knockdown mutant when expressed by a chromosomally integrated gene (Supplementary Figure 2). Repression by any of the reverse TetRs in M. bovis BCG was not as efficient as in M. smegmatis. However, TetR#27 and TetR#28 were also more efficient in this slow growing mycobacterium than the previously described TetR r1.7 (Figure 7). These new reverse TetRs will therefore likely extend the spectrum of genes that can be efficiently silenced in fast and slow growing mycobacteria.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

A grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Wellcome Trust through the Grand Challenges in Global Health Initiative (to D.S. and S.E.); and the National Institutes of Health (AI063446 to S.E.). Funding for open access charge: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Wellcome Trust.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Wolfgang Hillen and Dr Carl Nathan for providing anti-TetR antibodies and anti-DlaT antibodies, respectively, and for helpful discussions. We also thank Dr Graham Hatfull for the gift of plasmid pTT-P1A and Toshiko Odaira for excellent technical help.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE, III, et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sassetti CM, Boyd DH, Rubin EJ. Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;48:77–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalut C, Botella L, de Sousa-D’Auria C, Houssin C, Guilhot C. The nonredundant roles of two 4′-phosphopantetheinyl transferases in vital processes of Mycobacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:8511–8516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511129103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrt S, Guo XV, Hickey CM, Ryou M, Monteleone M, Riley LW, Schnappinger D. Controlling gene expression in mycobacteria with anhydrotetracycline and Tet repressor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gandotra S, Schnappinger D, Monteleone M, Hillen W, Ehrt S. In vivo gene silencing identifies the Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteasome as essential for the bacteria to persist in mice. Nat. Med. 2007;13:1515–1520. doi: 10.1038/nm1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomez JE, Bishai WR. whmD is an essential mycobacterial gene required for proper septation and cell division. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:8554–8559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140225297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo XV, Monteleone M, Klotzsche M, Kamionka A, Hillen W, Braunstein M, Ehrt S, Schnappinger D. Silencing Mycobacterium smegmatis by using tetracycline repressors. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:4614–4623. doi: 10.1128/JB.00216-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berg CM, Liu L, Wang B, Wang MD. Rapid identification of bacterial genes that are lethal when cloned on multicopy plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 1988;170:468–470. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.1.468-470.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen TN, Phan QG, Duong LP, Bertrand KP, Lenski RE. Effects of carriage and expression of the Tn10 tetracycline-resistance operon on the fitness of Escherichia coli K12. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1989;6:213–225. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berens C, Hillen W. Gene regulation by tetracyclines. Constraints of resistance regulation in bacteria shape TetR for application in eukaryotes. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003;270:3109–3121. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lutz R, Bujard H. Independent and tight regulation of transcriptional units in Escherichia coli via the LacR/O, the TetR/O and AraC/I1-I2 regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1203–1210. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skerra A. Use of the tetracycline promoter for the tightly regulated production of a murine antibody fragment in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1994;151:131–135. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90643-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bateman BT, Donegan NP, Jarry TM, Palma M, Cheung AL. Evaluation of a tetracycline-inducible promoter in Staphylococcus aureus in vitro and in vivo and its application in demonstrating the role of sigB in microcolony formation. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:7851–7857. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7851-7857.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geissendorfer M, Hillen W. Regulated expression of heterologous genes in Bacillus subtilis using the Tn10 encoded tet regulatory elements. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1990;33:657–663. doi: 10.1007/BF00604933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamionka A, Bertram R, Hillen W. Tetracycline-dependent conditional gene knockout in Bacillus subtilis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:728–733. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.2.728-733.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blokpoel MC, Murphy HN, O’Toole R, Wiles S, Runn ES, Stewart GR, Young DB, Robertson BD. Tetracycline-inducible gene regulation in mycobacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e22. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carroll P, Muttucumaru DG, Parish T. Use of a tetracycline-inducible system for conditional expression in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium smegmatis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:3077–3084. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.6.3077-3084.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez-Abanto SM, Woolwine SC, Jain SK, Bishai WR. Tetracycline-inducible gene expression in mycobacteria within an animal host using modified Streptomyces tcp830 regulatory elements. Arch. Microbiol. 2006;186:459–464. doi: 10.1007/s00203-006-0160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scholz O, Henssler EM, Bail J, Schubert P, Bogdanska-Urbaniak J, Sopp S, Reich M, Wisshak S, Kostner M, Bertram R, et al. Activity reversal of Tet repressor caused by single amino acid exchanges. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;53:777–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hillen W, Berens C. Mechanisms underlying expression of Tn10 encoded tetracycline resistance. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1994;48:345–369. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rowland B, Purkayastha A, Monserrat C, Casart Y, Takiff H, McDonough KA. Fluorescence-based detection of lacZ reporter gene expression in intact and viable bacteria including Mycobacterium species. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999;179:317–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orth P, Schnappinger D, Hillen W, Saenger W, Hinrichs W. Structural basis of gene regulation by the tetracycline inducible Tet repressor-operator system. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:215–219. doi: 10.1038/73324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaps I, Ehrt S, Seeber S, Schnappinger D, Martin C, Riley LW, Niederweis M. Energy transfer between fluorescent proteins using a co-expression system in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Gene. 2001;278:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00712-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pham TT, Jacobs-Sera D, Pedulla ML, Hendrix RW, Hatfull GF. Comparative genomic analysis of mycobacteriophage Tweety: evolutionary insights and construction of compatible site-specific integration vectors for mycobacteria. Microbiology. 2007;153:2711–2723. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/008904-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glickman MS, Jacobs WR., Jr. Microbial pathogenesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: dawn of a discipline. Cell. 2001;104:477–485. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00236-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snapper SB, Melton RE, Mustafa S, Kieser T, Jacobs WR., Jr. Isolation and characterization of efficient plasmid transformation mutants of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1911–1919. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stover CK, de la Cruz VF, Fuerst TR, Burlein JE, Benson LA, Bennett LT, Bansal GP, Young JF, Lee MH, Hatfull GF, et al. New use of BCG for recombinant vaccines. Nature. 1991;351:456–460. doi: 10.1038/351456a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.