Abstract

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)/Rel transcription factors are key regulators of a variety of genes involved in inflammatory responses, growth, differentiation, apoptosis, and development. There are increasing lines of evidence that NF-κB/Rel activity is controlled to a great extent by its phosphorylation state. In this study, we demonstrated that RelA physically associated with protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) subunit A (PR65). Both the N- and C-terminal regions of RelA were responsible for the PP2A binding. RelA co-immunoprecipitated with PP2A in melanocytes in the absence of stimulation, indicating that RelA forms a signaling complex with PP2A in the cells. RelA was dephosphorylated by a purified PP2A core enzyme, a heterodimer formed by the catalytic subunit of PP2A (PP2Ac) and PR65, in a concentration-dependent manner. Okadaic acid, an inhibitor of PP2A at lower concentration, increased the basal phosphorylation of RelA in melanocytes and blocked the dephosphorylation of RelA after interleukin-1 stimulation. Interestingly, PP2A immunoprecipitated from melanocytes was able to dephosphorylate RelA, whereas PP2A immunoprecipitated from melanoma cell lines exhibited decreased capacity to dephosphorylate RelA in vitro. Moreover, in melanoma cells in which IκB kinase activity was inhibited by sulindac to a similar level as in melanocytes, the phosphorylation state of RelA and the relative NF-κB activity were still higher than those in normal melanocytes. These data suggest that the constitutive activation of RelA in melanoma cells (Yang, J., and Richmond, A. (2001) Cancer Res. 61, 4901–4909) could be due, at least in part, to the deficiency of PP2A, which exhibits decreased dephosphorylation of NF-κB/RelA.

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)1/Rel transcription factors are key regulators of immune and inflammatory responses (1–3). Five members of the mammalian Rel family of proteins have been cloned and characterized: RelA, c-Rel, NF-κB1 (p50/p105), NF-κB2 (p52/p100), and RelB (1, 4, 5). In most cells, NF-κB transcription factors are inactive due to their cytoplasmic sequestration through interaction with inhibitor proteins known as IκB (6–10). The activation of NF-κB by a variety of agents such as cytokines, mitogens, viral infections, bacterial lipopolysaccharide, and phorbol esters involves phosphorylation of IκB proteins by IκB kinases (IKKs) (11–17). The phosphorylated IκB proteins undergo ubiquitination and degradation, thereby releasing NF-κB and allowing nuclear translocation of NF-κB to activate the expression of target genes (11–17).

Signals that induce phosphorylation of IκB proteins can also cause phosphorylation of NF-κB proteins. For example, tumor necrosis factor-α induces phosphorylation of RelA at serine 536 by IKK (18) and at serine 529 through casein kinase II (19). In vitro studies have suggested that phosphorylation of NF-κB transcription factors, including RelA and p50, enhances DNA binding ability (20, 21). In vivo, the inducible phosphorylation on NF-κB is correlated with dimerization, release from IκB, nuclear translocation, or activation of the transcription function of NF-κB (19, 22). Inhibition of interleukin-1-stimulated RelA phosphorylation by mesalamine is accompanied by decreased transcriptional activity of NF-κB (23).

The phosphorylation of NF-κB transcription factors is regulated not only by protein serine/threonine kinases, but also by protein serine/threonine phosphatases. Compared with the well established mechanisms for the phosphorylation of NF-κB transcription factors, the mechanisms underlying the dephosphorylation of these transcription factors are still poorly understood. Four major classes of protein phosphatases have been described, include PP1, PP2A, PP2B (calcineurin), and PP2C. PP2B is calcium-dependent, and PP2C is magnesium-dependent, whereas PP1 and PP2A are not dependent upon divalent cations. PP1 and PP2A are widely expressed in mammalian cells and are involved in the regulation of signaling pathways by a mechanism of phosphorylation/dephosphorylation with a variety of protein kinases (24). The predominant form of PP2A in cells is a heterotrimeric holoenzyme. The core components (core enzyme) of all trimeric forms are the 36-kDa catalytic subunit (PP2Ac) and a 65-kDa regulatory subunit (PP2Aa or PR65). In addition, there are several associated variable regulatory subunits (B subunits) that bind to the core enzyme and confer substrate specificity to its dephosphorylating activity (24). PP2A has been shown to form a complex with calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV (25); casein kinase (26); p21-activated kinase-1 and -3 and p70 S6 kinase (27); and certain G-protein-coupled receptors such as the β2-adrenergic receptor and CXCR2 (28, 29). However, a previous study demonstrated that the SV40 small t antigen, which associates with PP2A and specifically inhibits its phosphatase activity, enhances the activity of NF-κB (30). In addition, treatment of Jurkat cells with okadaic acid (OA), a specific inhibitor of PP1 and PP2A, induces translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus and activation of NF-κB (31). These findings suggest a potential involvement of PP2A in the regulation of NF-κB signaling. To determine whether PP2A plays a direct role in the regulation of phosphorylation of RelA, we examined the interaction of RelA with PP2A. Here, we provide evidence that RelA physically interacts with the PR65 subunit of PP2A. The purified PP2A core enzyme directly dephosphorylates RelA. Moreover, the activity of PP2A in melanoma cells is lower than that in melanocytes, which partially contributes to the higher phosphorylation state of RelA and the increased NF-κB activity in the melanoma cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Construction

The expression vectors encoding full-length RelA and deletion mutants of RelA in pcDNA3 were prepared as described (18). The wild-type and mutant RelA cDNAs were cut with BamHI and XhoI and inserted into the pGEX-5X-3 vector (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) digested with the same enzymes. The GST-PR65 expression plasmid was a generous gift from Dr. Kerry Campbell (Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA). GST-PP2Ac was generated by amplifying the human PP2Ac cDNA (32). The fragment was digested with BamHI and XhoI and inserted into pGEX-KG digested with the same enzymes. The GST fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21 and purified with glutathione-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Cell Culture and Treatment

Melanoma cell lines Sk Mel 5 and WM 115, established from human melanomas, were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. Normal human epidermal melanocytes (NHEMs) were provided by the Tissue Culture Core of the Skin Disease Research Center. Melanoma cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s/Ham’s F-12 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 μM minimal essential medium containing nonessential amino acids (Life Technologies, Inc.), and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma). NHEMs were cultured in medium 154 (Cascade Biologics, Inc.) with appropriate additions as described by the manufacturer. Sulindac (1 mM) was added into the cell culture medium for 16 h for the luciferase assay or for 2 h prior to assays of IKK activity and RelA phosphorylation.

In Vitro Binding Assay

BL21 cells transformed with GST or GST fusion protein constructs were cultured in LB medium overnight at 37 °C; then isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (200 mM) was added, and incubation was continued for another 3 h to induce protein expression. The bacteria were lysed in PBST buffer (1% Triton X-100 and 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol in phosphate-buffered saline) by sonication on ice for 10 s. The supernatant of the bacterial lysate was incubated with glutathione-Sepharose at 4 °C for 30 min. The beads were washed three times with PBST buffer prior to addition to the cell lysate from NHEMs. GST or GST fusion proteins bound to glutathione-Sepharose were incubated with the cell lysate for 2 h at 4 °C with rotation. Beads were pelleted by centrifugation (12,000 rpm) for 2 min and washed three times with PBST cell lysis buffer. Bound proteins were released by boiling in Laemmli sample buffer for 5 min and detected by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Co-immunoprecipitation

NHEMs were washed with phosphate-buffered saline twice and incubated with 2.5 mM dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate) or disuccinimidyl suberate (both from Pierce) for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were lysed in 1 ml of radioimmune precipitation assay buffer. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation for 4 min at 13,000 rpm in an Eppendorf microcentrifuge. The supernatant was precleared for 1 h to reduce nonspecific binding by addition of 40 μl of protein A/G-agarose (Pierce). After removal of the protein A/G-agarose by centrifugation in an Eppendorf microcentrifuge at 3000 rpm for 1 min, the supernatant was collected, and 10 μl of antibody against RelA (C-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or PP2Ac (P47720, Transduction Laboratories) was added for overnight incubation at 4 °C with rotation. 40 μl of protein A/G agarose was then added and incubated at 4 °C for 2 h prior to sedimentation. The immunocomplex was washed three times with ice-cold radioimmune precipitation assay buffer, and the final pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of Laemmli sample buffer containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol and boiled for 10 min. 20 μl of this preparation was electrophoresed on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and the proteins on the gel were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) as previously described (31). Coprecipitated RelA or PP2Ac was detected by Western blotting using specific antibodies.

In Vitro Phosphorylation and Dephosphorylation

The bacterially expressed GST fusion protein of RelA-(354 –551) was labeled with [γ-32P]ATP by the constitutively activated IKK complex from the melanoma cell line Sk Mel 5. Briefly, cells were collected by mechanically release from tissue culture plates into cold phosphate-buffered saline. Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared in lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) with Complete protein inhibitors (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) and incubated with 1 μg of both polyclonal anti-IKKα and anti-IKKβ antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and 60 μg of protein A/G-agarose for 3 h at 4 °C. After washing twice with washing buffer (50 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 0.1% Nonidet P-40) and once with kinase buffer, the beads were incubated with 1 μg of GST-RelA fusion protein in 20 μl of kinase buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 20 mM MgCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 200 μM ATP in the presence of 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP at 30 °C for 30 min. The 32P-labeled GST-RelA protein in the supernatant was separated from the IKKα·IKKβ immunoprecipitants by centrifugation. Dephosphorylation was carried out by incubating the 32P-labeled GST-RelA protein with different concentrations of purified PP2A core enzyme (0, 0.01, 0.1, and 0.5 μg) in 30 μl of reaction buffer for 60 min at 30 °C. The reaction was terminated by adding Laemmli sample buffer containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol and boiling for 10 min. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE (10%), and phosphorylated RelA was detected by autoradiography.

In Vitro Kinase Assay

The IKKα·IKKβ complex was immunoprecipitated as described above. The immunoprecipitates were incubated with IκBα-(1–54) as a substrate in 20 μl of kinase assay buffer containing 100 μM ATP and 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP at 30 °C for 30 min. The reaction was terminated by adding Laemmli sample buffer and boiling for 10 min. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE (10%), and phosphorylated RelA was detected by autoradiography.

In Vivo Phosphorylation and Dephosphorylation

Human melanocytes were metabolically labeled by incubation with [32P]orthophosphate (100 μCi/ml; PerkinElmer Life Sciences) in phosphate-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium at 37 °C for 1 h. Cells were then stimulated with or without interleukin-1β for 20 min. Dephosphorylation was performed by allowing the cells to recover in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium at 37 °C for 1 h. Cells were lysed in cold radioimmune precipitation assay buffer, and RelA was immunoprecipitated as described above. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). Phosphorylated RelA was detected by autoradiography. The membrane was blotted with a polyclonal antibody against RelA to confirm equal loading.

Luciferase Reporter Activity Assay

Melanoma cells or NHEMs were transfected with an NF-κB reporter construct, a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat luciferase reporter containing two NF-κB-binding sites, and a β-galactosidase reporter vector. Cell extracts were analyzed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities using the Dual-Light kit (Tropix Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

RESULTS

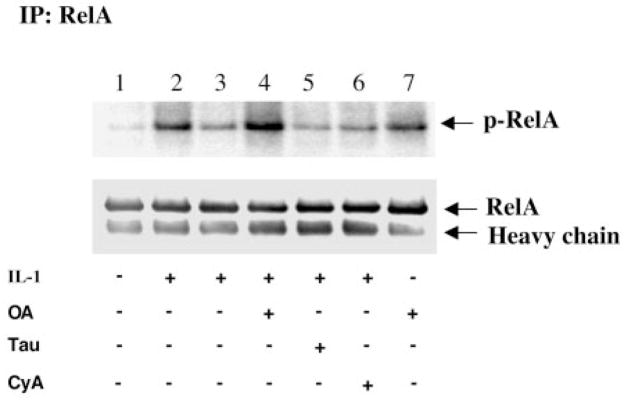

To determine which protein phosphatase is involved in the dephosphorylation of RelA, phosphatase inhibitors were tested for the inhibition of RelA dephosphorylation. We took advantage of inhibitors with different phosphatase specificities: OA, an inhibitor of PP1 and PP2A (33, 34, 37); tautomycin, a selective inhibitor of PP1 (33, 35); and cyclosporin A, a specific inhibitor of PP2B (33, 36). As shown in Fig. 1, exposure of the NHEMs to interleukin-1 resulted in a more robust phosphorylation of RelA (Fig. 1, lane 2) compared with the untreated cells (lane 1). This phosphorylation was reversed after withdrawal of the agonist and recovery of the cells at 37 °C for another 1 h (Fig. 1, lane 3). Pretreatment with OA (50 nM) greatly inhibited the dephosphorylation of RelA (Fig. 1, lane 4), whereas pre-treatment with cyclosporin A (400 nM) or tautomycin (500 nM) did not block the protein dephosphorylation (lanes 5 and 6). Interestingly, treatment of the cells with OA increased the basal phosphorylation of RelA (Fig. 1, lane 7).

Fig. 1. Dephosphorylation of RelA is inhibited by OA in melanocytes.

NHEMs were metabolically labeled with [32P]orthophosphate in phosphate-free medium for 1 h. Cells were treated for 10 min without or with 50 nM OA (lanes 4 and 7), 400 nM tautomycin (Tau) (lane 5), or 400 nM cyclosporin A (CyA) (lane 6) prior to incubation without (lanes 1 and 7) or with (lanes 2–6) interleukin-1 (IL-1; 1 ng/ml) for 20 min. The cells were then kept on ice (lanes 1, 2, and 7) or incubated in medium at 37 °C (lanes 3–6) for another 1 h in the absence or presence of the inhibitors as indicated. RelA was immunoprecipitated (IP) with a polyclonal anti-RelA antibody as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Phosphorylated RelA was detected by autoradiography. The same membrane was blotted with a polyclonal anti-RelA antibody to confirm equal loading. The data shown represent one of three independent experiments.

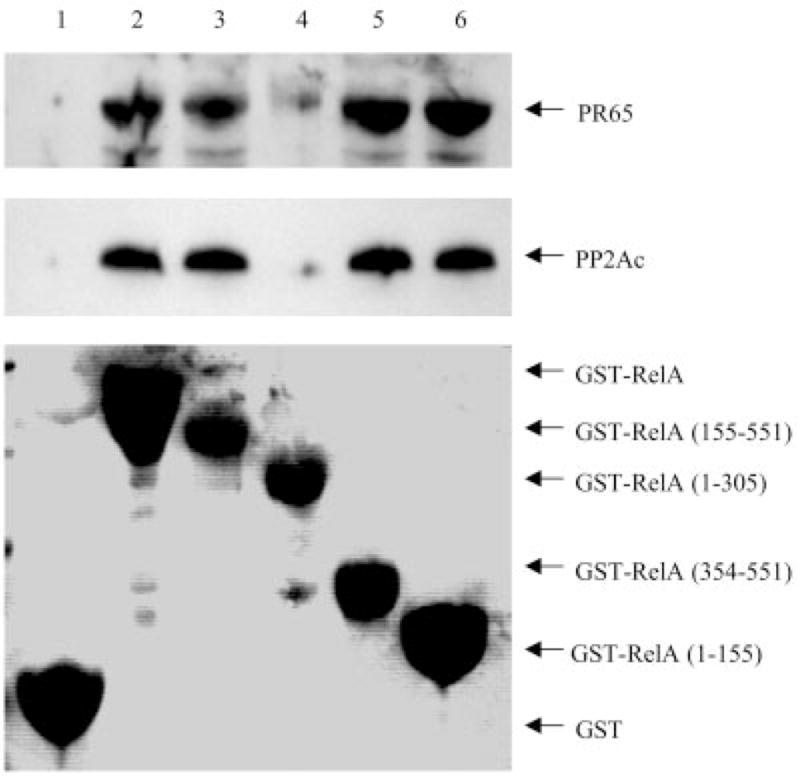

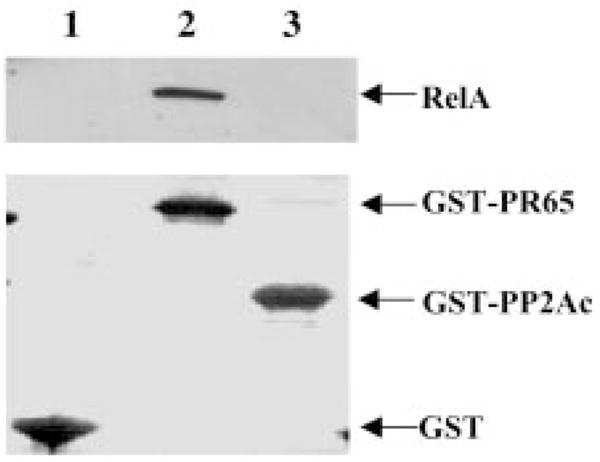

To examine whether PP2A associates with RelA, a GST pull-down assay was performed. GST-RelA fusion proteins were incubated with NHEM cell lysate, and the coprecipitated PP2Ac and PR65 subunits were detected by Western blotting using antibodies against PP2Ac and PR65, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2, PR65 and PP2Ac were coprecipitated with GST-RelA (lane 2), but not with GST alone (lane 1). The N-terminal truncated mutant forms of RelA (amino acids 155–551 and 354 –551) bound an almost equal amount of the PP2A core enzyme (Fig. 2, lanes 3 and 5). However, a C-terminal truncated mutant of RelA (amino acids 1–305) failed to bind the PP2A core enzyme (Fig. 2, lane 4), whereas a further C-terminal truncated mutant of RelA (amino acids 1–155) retained the ability to bind to PP2A (lane 6), suggesting that PP2A may bind to both the C- and N-terminal regions of RelA and that the folding of RelA-(1–305) does not allow the N-terminal region of RelA to bind to PP2A. To assess which subunit of the heterodimeric PP2A core enzyme binds directly to RelA, GST fusion proteins of PR65 and PP2Ac were incubated with the cell lysate from Sk Mel 5 melanoma cells, and coprecipitated RelA was detected by Western blotting. The results demonstrated that RelA bound only to GST-PR65, but not to GST-PP2Ac (Fig. 3), suggesting direct interaction between RelA and PR65.

Fig. 2. In vitro interaction of RelA with PP2A.

GST alone or GST-RelA fusion proteins of wild-type and truncated mutant RelA were incubated with NHEM cell lysate as described under “Experimental Procedures.” After washing, the beads were resuspended in loading buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Coprecipitated PR65 and PP2Ac were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-PR65 and anti-PP2Ac antibodies, respectively. The membrane was initially stained with 0.1% Ponceau S solution (P 7170, Sigma) to confirm protein expression and equal loading. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Fig. 3. In vitro interaction of PP2A subunits with RelA.

GST alone or GST fusion proteins of PP2Ac and PR65 were incubated with Sk Mel 5 melanoma cell lysate. A GST pull-down assay was performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Coprecipitated RelA was analyzed by immunoblotting with a polyclonal anti-RelA antibody. The membrane was initially stained with Ponceau S solution to identify the GST fusion protein concentration. The data shown are representative of two independent experiments.

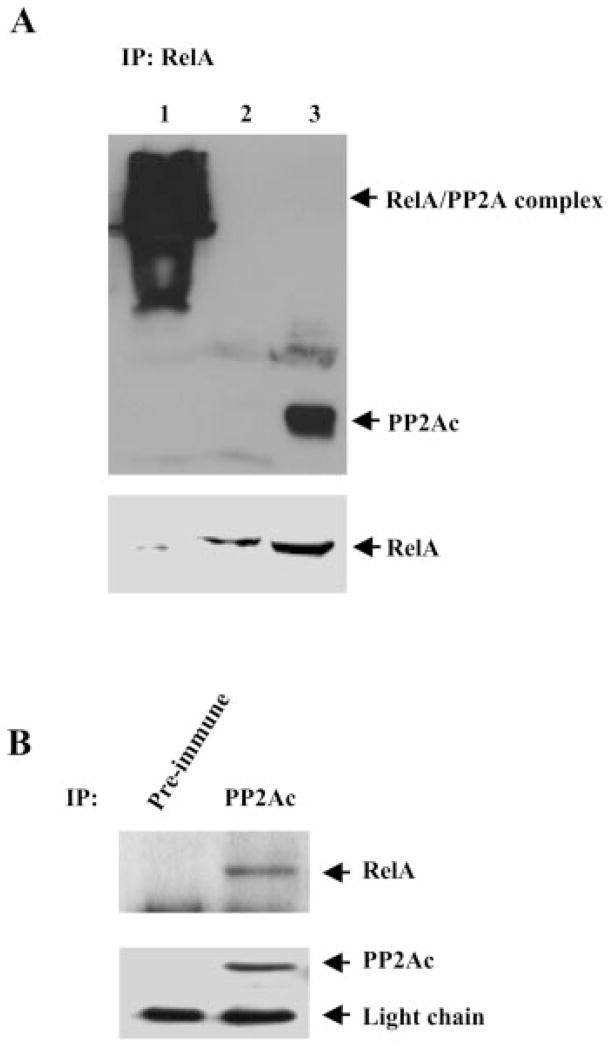

Based on our observation that OA, an inhibitor of PP2A, blocks the dephosphorylation of RelA, we hypothesized that PP2A might be responsible for the dephosphorylation of RelA. If this interaction were one of enzyme/substrate, we postulated it would then be transient and therefore chose to use cross-linker to stabilize the proposed complex. To determine whether a functional complex consisting of RelA and the PP2A core enzyme could be detected in mammalian cells, NHEMs were treated with dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate), a cleavable cross-linker, or with disuccinimidyl suberate, a non-cleavable cross-linker; RelA was immunoprecipitated from the cell lysate; and co-immunoprecipitated PP2A was detected by Western blotting under reducing conditions. As shown in Fig. 4A, in the cells treated with disuccinimidyl suberate, immunoprecipitation of RelA resulted in a high molecular mass band that was reactive to anti-PP2Ac antibody (lane 1), whereas in the cells treated with dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate), PP2A was also co-immunoprecipitated with RelA, but was separated from RelA under reducing conditions (lane 3). However, no detectable PP2A was co-immunoprecipitated with RelA in the cells without cross-linker treatment (Fig. 4A, lane 2), suggesting a transient interaction of RelA with PP2A.

Fig. 4. RelA associates with the PP2A core enzyme in melanocytes.

A, NHEMs were treated with 2.5 mM dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate) or disuccinimidyl suberate for 30 min, and RelA was immunoprecipitated (IP) from the cell lysate with an anti-RelA antibody. Proteins were separated under reducing conditions by SDS-PAGE (10%) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Coprecipitated PP2Ac was blotted with an anti-PP2Ac antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with an anti-RelA antibody. B, PP2Ac was immunoprecipitated from NHEM lysate with an anti-PP2Ac antibody (second lane). Preimmune mouse IgG1 (MAB002, R&D Systems) was used in parallel as a control (first lane). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Coprecipitated RelA was blotted an anti-RelA antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with an anti-PP2Ac antibody. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments.

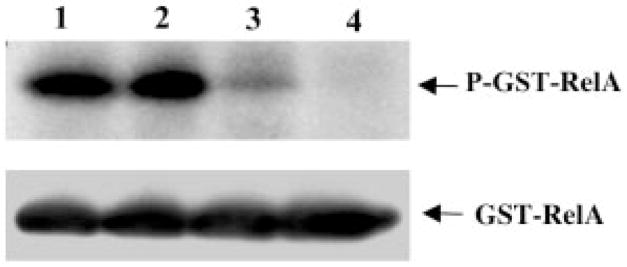

To determine whether RelA is directly dephosphorylated by PP2A, an in vitro phosphorylation and dephosphorylation assay was performed. The GST-RelA fusion protein was phosphorylated by IKKα·IKKβ immunoprecipitants from SK Mel 5 cells. The phosphorylated GST-RelA protein was then incubated with a purified PP2A core enzyme. As shown in Fig. 5, RelA was dephosphorylated by the purified PP2A core enzyme in a concentration-dependent manner.

Fig. 5. In vitro dephosphorylation of RelA by the purified PP2A core enzyme.

IKKα·IKKβ complexes immunoprecipitated from SK Mel 5 cells were incubated with 1 μg of GST-RelA protein in the presence of 5 μCi of γ-32P]ATP at 30 °C for 30 min. The supernatant containing phosphorylated RelA was incubated with different concentrations (lane 1, 0 μg; lane 2, 0.01 μg; lane 3, 0.1 μg; lane 4, 0.5 μg) of purified PP2A core enzyme for another 1 h at 30 °C. The reactions were terminated by adding Laemmli sample buffer and boiling for 5 min. The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Phosphorylated proteins were detected by autoradiography. The same membrane was blotted with an anti-RelA antibody to confirm equal loading. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments.

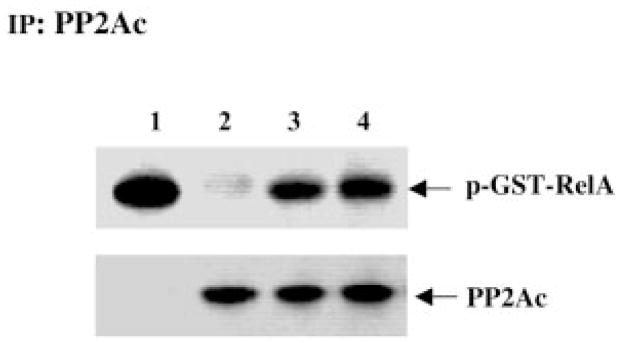

Previous studies have demonstrated that RelA in melanoma cells is constitutively activated (38). Considering the genetic alteration of PR65 that has been found in melanoma cells and other cancer cells (39), we postulated that PP2A in melanoma cells is functionally deficient in regulating the phosphorylation of RelA, resulting in hyperphosphorylation and constitutive activation of the transcription factor. To test this hypothesis, PP2A was immunoprecipitated from either melanocytes or melanoma cell lines, and the immunoprecipitants were tested for dephosphorylation of RelA phosphorylated by purified IKK. Interestingly, the dephosphorylation activity of PP2A in the melanoma cell lines Sk Mel 5 and WM 115 was decreased compared with that in NHEMs (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Dephosphorylation of the RelA subunit by PP2A immunoprecipitated from melanocytes or melanoma cell lines.

The purified GST-RelA protein was phosphorylated using [γ-32P]ATP in an in vitro specific kinase reaction with IKK immunoprecipitated from Sk Mel 5 melanoma cells. The 32P-labeled GST-RelA protein was incubated without (lane 1) or with PP2Ac immunoprecipitated (IP) from NHEMs (lane 2), Sk Mel 5 cells (lane 3), or WM 115 cells (lane 4) at 30 °C for 1 h. The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Phosphorylated proteins were detected by autoradiography. The membrane was blotted with an anti-PP2Ac antibody to confirm equal loading. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments.

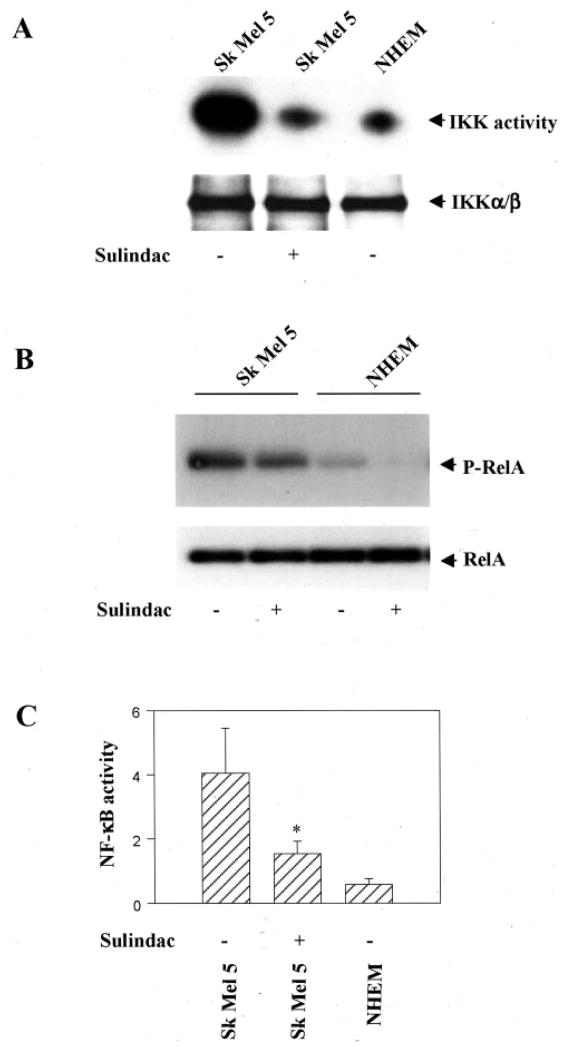

To test the hypothesis that the constitutive RelA activity in melanoma cells is attributed not only to the constitutive IKK activity (38), but also to some other events such as the PP2A deficiency, the phosphorylation state of RelA and the relative NF-κB activity were measured in melanocytes and melanoma cell lines treated with the IKK inhibitor sulindac (40). Sulindac (1 mM) treatment of Sk Mel 5 cells reduced the IKK activity to an equal or lower level than the kinase activity in NHEMs without sulindac treatment (Fig. 7A). However, the phosphorylation state of RelA in sulindac-treated Sk Mel 5 cells was still higher than that in NHEMs without sulindac treatment (Fig. 7B). Although sulindac treatment reduced the NF-κB activity, it remained significantly higher than that in NHEMs without sulindac treat (Fig. 7C). These data suggest that the higher phosphorylation state and the relative activity of RelA in melanoma cells are due in part to the deficient PP2A activity.

Fig. 7. IKK activity, RelA phosphorylation, and NF-κB activity in melanoma cells.

A, Sk Mel 5 cells (but not NHEMs) were treated without or with sulindac (1 mM), and the IKKα·IKKβ complex was immunoprecipitated with a mixture of polyclonal anti-IKKα and anti-IKKβ antibodies and assayed for phosphorylation of a GST-IκBα-(1–54) substrate. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%), transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and analyzed by autoradiography. B, Sk Mel 5 cells and NHEMs were treated without or with sulindac (1 mM) before being incubated with 100 μCi/ml [32P]orthophosphate in phosphate-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium for 1 h. RelA was immunoprecipitated with a rabbit anti-RelA antibody. The immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE (10%), transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and analyzed by autoradiography. The membrane was blotted with a monoclonal anti-RelA antibody to confirm equal loading. C, Sk Mel 5 cells and NHEMs were cotransfected with an NF-κB reporter construct as well as a β-galactosidase construct. 18 h after transfection, Sk Mel 5 cells (but not NHEMs) were treated without or with sulindac (1 mM) for 16 h, and then the total cell extracts were analyzed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities using the Dual-Light kit. The luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activity and is reported as -fold activation over the luciferase activity in NHEMs. Values shown are the means ± S.D. The data were analyzed using Student’s paired t test. *, p < 0.05 compared with the NF-κB activity in NHEMs.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have provided evidence that PP2A plays an important role in the regulation of RelA phosphorylation by forming a complex with the transcription factor. The formation of this complex in the cells is probably transient since cross-linking was required to observe it. PP2A may interact with RelA through its regulatory subunit A, directly binding to RelA, because only the GST fusion protein of PR65 (but not that of PP2Ac) interacted with RelA in our experiments. We did not have a chance to examine the potential interaction of RelA with the B subunits of PP2A, which comprise several polypeptides that regulate PP2A activity and specificity. RelA is phosphorylated predominantly at the C-terminal serine residues, e.g. Ser-529 (19) and Ser-536 (18). It is not clear whether PP2A directly binds to those phosphorylation sites. However, studies on the interaction of PP2A with proteins such as protein kinase Cζ (25), casein kinase-2α (28), and CXCR2 (31) indicate that PP2A binds to sites other than the phosphorylation sites in these proteins. The interaction of RelA with PP2A appears to be specific and functional because the dephosphorylation of RelA in vitro by the purified PP2A core enzyme was concentration-dependent, and the dephosphorylation of RelA was blocked by the lower concentration of OA (which predominantly inhibits PP2A), but not tautomycin (PP1 inhibitor) or cyclosporin A (PP2B inhibitor).

In addition to RelA, another important subunit of NF-κB, p50, is also regulated by phosphorylation (21). Hyperphosphorylation of p50 is required for phorbol ester- and hemagglutinin-induced nuclear translocation in Jurkat cells, and phosphorylated p50 accounts for most of the observed nuclear p50 population (41). Phosphorylation of p50 protein has also been shown to increase affinity of formation and stability of p50·DNA complexes in vitro (41). It will be of interest to investigate the potential interaction of PP2A with p50 NF-κB.

It is increasingly clear that dephosphorylation is an important step in reestablishing a normal responsiveness of NF-κB/Rel transcription factors after stimulation removal. RelA forms a complex with PP2A in unstimulated cells. Upon stimulation, RelA is phosphorylated by certain protein serine/threonine kinases. Phosphorylated RelA is translocated from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and activates the expression of target genes. Then the transcription factor may form a complex with PP2A and be dephosphorylated by the phosphatase. Because the majority of PP2A localizes in the cytoplasm, it is postulated that the dephosphorylation of RelA by PP2A occurs mainly in the cytoplasm. In view of the basal association of PP2A with RelA in the absence of stimulation and of the higher incorporation of phosphate in RelA after OA treatment, it appears that the basal level of dephosphorylation has to be relatively active to maintain a low state of phosphorylation of RelA, which is necessary for the normal responsiveness of the transcription factor. Thus, a fraction (if not all) of RelA appears to undergo a constitutive phosphorylation/dephosphorylation cycle in un-stimulated cells, presumably controlled by protein kinases such as IKKs, casein kinases, and protein kinase C and by protein phosphatases such as PP2A. Disrupting the phosphorylation/dephosphorylation cycle would result in constitutive phosphorylation and activation of the transcription factor. It has been shown that the small t antigen, which associates with PP2A and specifically inhibits the phosphatase activity, is able to induce transactivation of NF-κB (25). OA, a potent inhibitor of PP1 and PP2A, induces NF-κB in nuclear extracts (26).

NF-κB has been shown to promote cell survival and escape from apoptosis (42). Induction of NF-κB upon treatment with tumor necrosis factor-α, radiation, and chemotherapeutic agents can protect cells from apoptosis (43–46). There is increasing evidence that NF-κB is important in control of oncogenesis (47). NF-κB controls the expression of several growth factors, oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes (c-myc, p53), and genes encoding cell adhesion proteins and proteases of the extracellular matrix (48). More interestingly, NF-κB activation has been reported in various types of cancers (47, 49, 50). Our previous study also demonstrated constitutive activation and nuclear translocation of RelA in melanoma cell lines (38).

Although the mechanism underlying the constitutive activation of NF-κB in cancer cells remains poorly understood, it has been suggested that PP2A, which controls the phosphorylated state of NF-κB is, at least partially, not functional. Direct evidence for this suggestion has been lacking until recently, when Wang et al. (51) discovered that the gene encoding the β isoform of PR65 was altered in 15% of primary lung tumors, in 6% of lung tumor-derived cell lines, and in 15% of primary colon tumors. Then Calin et al. (39) reported that both the Aα and Aβ subunit isoforms of PR65 were genetically altered in a variety of primary human cancers. All of these mutations have been confirmed to disrupt PP2A subunit interaction and to impair the phosphatase activity (52).

To address whether PP2A in melanoma cell lines is able to dephosphorylate RelA, PP2A was immunoprecipitated from either melanocytes or melanoma cell lines, and the immunoprecipitates were tested for the ability to dephosphorylate RelA in vitro. Interestingly, PP2Ac that was immunoprecipitated from melanoma cell lines exhibited decreased ability to dephosphorylate RelA, whereas as control PP2A that was immunoprecipitated from normal melanocytes was able to dephosphorylate RelA. Based on these data, we postulate that the constitutive activation of RelA in melanoma cells is attributed not only to the constitutive IKK activity as reported previously (38), but also to some other events such as the deficient PP2A activity in these cells. This hypothesis is supported by our data that, in the melanoma cells in which IKK activity was inhibited to a similar level as in melanocytes, the phosphorylation state and the relative NF-κB activity were still significantly higher than those in normal melanocytes. These results suggest the interesting possibility that introducing normal PP2A to the cancer cells may reestablish a normal function of NF-κB and other proteins. In our future study, melanoma cell lines and other cancer cells will be infected with adenovirus encoding the normal PP2A gene, and NF-κB activity and cell differentiation will be investigated.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates for the first time that PP2A physically interacts with and directly dephosphorylates RelA. PP2A forms a complex with RelA in untreated cells. PP2A immunoprecipitated from melanoma cell lines exhibits decreased ability to dephosphorylate RelA in vitro, which explains, at least in part, the constitutive activation of NF-κB in certain cancer cells.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a career scientist grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs (to A. R.), NCI Grants CA34590 and CA56704 from the National Institutes of Health (to A. R.), and Grant CA68485 to the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center from the National Institutes of Health.

The abbreviations used are: NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; IKK, IκB kinase; PP, protein phosphatase; OA, okadaic acid; GST, glutathione S-transferase; NHEMs, normal human epidermal melanocytes.

This paper is available on line at http://www.jbc.org

References

- 1.Baeuerle PA, Henkel T. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:141–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verma IM, Stevenson JK, Schwarz EM, Van Antwerp D, Miyamoto S. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2723–2735. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baeuerle PA, Baltimore D. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin AS., Jr Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:649 –683. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh S, May MJ, Kopp EB. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:225–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haskill S, Beg AA, Tompkins SM, Morris JS, Yurochko AD, Sampson-Johannes A, Mondal K, Ralph P, Baldwin AS., Jr Cell. 1991;65:1281–1289. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90022-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson JE, Phillips RJ, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Ghosh S. Cell. 1995;80:573–582. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90511-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whiteside ST, Epinat JC, Rice NR, Israel A. EMBO J. 1997;16:1413–1426. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Z, Nabel GJ. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6184 –6190. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.6184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simeonidis S, Liang S, Chen G, Thanos D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14372–14377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Traenckner EB, Pahl HL, Henkel T, Schmidt KN, Wilk S, Baeuerle PA. EMBO J. 1995;14:2876 –2883. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scherer DC, Brockman JA, Chen Z, Maniatis T, Ballard DW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11259 –11263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Z, Hagler J, Palombella VJ, Melandri F, Scherer D, Ballard D, Maniatis T. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1586 –1597. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.13.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiDonato J, Mercurio F, Rosette C, Wu-Li J, Suyang H, Ghosh S, Karin M. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1295–1304. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodriguez MS, Wright J, Thompson J, Thomas D, Baleux F, Virelizier JL, Hay RT, Arenzana-Seisdedos F. Oncogene. 1996;12:2425–2435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roff M, Thompson J, Rodriguez MS, Jacque JM, Baleux F, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Hay RT. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7844 –7850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weil R, Laurent-Winter C, Israel A. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9942–9949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakurai H, Chiba H, Miyoshi H, Sugita T, Toriumi W. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30353–30356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang D, Baldwin AS., Jr J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29411–29416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naumann M, Scheidereit C. EMBO J. 1994;13:4597–4607. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06781.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li C, Korner M, Ferris DK, Chen E, Dai RM, Longo DL. Biochem J. 1994;303:499 –506. doi: 10.1042/bj3030499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhong H, Suyang H, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Ghosh S. Cell. 1997;89:413–424. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egan LJ, Mays DC, Huntoon CJ, Bell MP, Pike MG, Sandborn WJ, Lipsky JJ, McKean DJ. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26448 –26453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mumby MC, Walter G. Physiol Rev. 1993;73:673–699. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westphal RS, Anderson KA, Means AR, Wadzinski BE. Science. 1997;280:1258 –1261. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5367.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heriche JK, Lebrin F, Rabilloud T, Leroy D, Chambaz EM, Goldberg Y. Science. 1997;276:952–955. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5314.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Westphal RS, Coffee RL, Jr, Marotta A, Pelech SL, Wadzinski BE. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:687–692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krueger KM, Daaka Y, Pitcher JA, Lefkowitz RJ. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan GH, Yang W, Sai J, Richmond A. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16960 –16968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009292200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sontag E, Sontag JM, Garcia A. EMBO J. 1997;16:5662–5671. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thevenin C, Kim SJ, Rieckmann P, Fujiki H, Norcross MA, Sporn MB, Fauci AS, Kehrl JH. New Biol. 1990;2:793–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wadzinski BE, Eisfelder BJ, Peruski LF, Jr, Mumby MC, Johnson GL. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16883–16888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giannini E, Boulay F. J Immunol. 1995;154:4055–4064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Durfee T, Becherer K, Chen P, Yeh S, Yang Y, Kilburn A, Lee W, Elledge SJ. Genes Dev. 1993;7:555–569. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harper JM, Adami G, Wei N, Keyomarsi K, Elledge SJ. Cell. 1993;75:805–816. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90499-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wuyts A, Schutyser E, Menten P, Struyf S, D’Haese A, Bult H, Opdenakker G, Proost P, Van Damme J. Biochemistry. 2000;39:14549 –14557. doi: 10.1021/bi0011227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bialojan C, Takai A. Biochem J. 1988;256:283–290. doi: 10.1042/bj2560283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang J, Richmond A. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4901–4909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calin GA, di Iasio MG, Caprini E, Vorechovsky I, Natali PG, Sozzi G, Groce CM, Barbanti-Brodano G, Negrini M. Oncogene. 2000;19:1191–1195. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamamoto Y, Yin MJ, Lin KM, Gaynor RB. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27307–27314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.27307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li C, Dai RM, Chen E, Longo DL. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30089 –30092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sonenshein GE. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2952–2960. doi: 10.1172/JCI119848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beg AA, Sha WC, Baltimore D. Science. 1996;274:782–784. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang CY, Mayo MW, Baldwin ASJ. Science. 1996;274:784 –787. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Antwerp DJ, Martin SJ, Kafri T, Green DR, Verma IM. Science. 1996;274:787–789. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu ZG, Hsu HL, Goeddel DV, Karin M. Cell. 1996;87:565–576. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luque I, Gelinas C. Semin Cancer Biol. 1997;8:103–111. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1997.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gilmore TD, Koedoor M, Piffat KA, White DW. Oncogene. 1996;13:1367–1378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sovak MA, Bellas RE, Kim DW, Zanieski GJ, Rogers AE, Traish AM, Sonenshein GE. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2952–2960. doi: 10.1172/JCI119848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Budunova IV, Perez P, Vaden VR, Spiegelman VS, Slaga TJ, Jorcano JL. Oncogene. 1999;18:7423–7431. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang SS, Esplin ED, Li JL, Huang L, Gazdar A, Minna J, Evans GA. Science. 1998;282:284–287. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5387.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ruediger R, Pham HT, Walter G. Oncogene. 2000;20:10–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]