Abstract

Urease, a major virulence factor for Cryptococcus neoformans, promotes lethal meningitis/encephalitis in mice. The effect of urease within the lung, the primary site of most invasive fungal infections, is unknown. An established model of murine infection that utilizes either urease-producing (wt and ure1::URE1) or urease-deficient (ure1) strains (H99) of C. neoformans was used to characterize fungal clearance and the resultant immune response evoked by these strains within the lung. Results indicate that mice infected with urease-producing strains of C. neoformans demonstrate a 100-fold increase in fungal burden beginning 2 weeks post–infection (as compared with mice infected with urease-deficient organisms). Infection with urease-producing C. neoformans was associated with a highly polarized T2 immune response as evidenced by increases in the following: 1) pulmonary eosinophils, 2) serum IgE levels, 3) T2 cytokines (interleukin-4, -13, and -4 to interferon-gamma ratio), and 4) alternatively activated macrophages. Furthermore, the percentage and total numbers of immature dendritic cells within the lung-associated lymph nodes was markedly increased in mice infected with urease-producing C. neoformans. Collectively, these data define cryptococcal urease as a pulmonary virulence factor that promotes immature dendritic cell accumulation and a potent, yet non-protective, T2 immune response. These findings provide new insights into mechanisms by which microbial factors contribute to the immunopathology associated with invasive fungal disease.

Cryptococcus neoformans, an opportunistic fungal pathogen acquired through inhalation, causes severe pneumonia and subsequent central nervous system (CNS) infections, predominantly in immunocompromised individuals.1,2,3,4 Recent reports of invasive cryptococcosis in noncompromised individuals indicate that the organism can evade or neutralize intact host defense mechanisms.5,6,7 Numerous cryptococcal virulence factors have been defined that influence the pathogenesis of C. neoformans infection.8,9,10 Quantitative differences in the expression of these factors have been shown to alter the host’s ability to clear the primary infection or prevent systemic dissemination.11,12,13,14,15 However, the specific cellular and molecular mechanisms by which these factors enhance virulence remain largely unknown. Understanding these mechanisms may aid the development of new strategies designed to prevent and/or treat invasive fungal disease in humans.

The cryptococcal urease gene (URE1) is a significant virulence factor associated with increased mortality in C. neoformans-infected mice.16,17 The mechanisms responsible for this effect are not fully understood. We have previously shown that urease promotes microvascular sequestration within the brain, resulting in increased CNS invasion with resultant meningoencephalitis and death.17 Although urease is not required for the acute growth of organism in the lungs,17 others have shown that chronic pulmonary infection, the primary portal of entry for C. neoformans,18 is a prerequisite for cryptococcal dissemination into the CNS.19,20,21 Whether cryptococcal urease might also function as a virulence factor by contributing to the persistence of C. neoformans within the lung is unknown.

The clearance of C. neoformans from the lung and the prevention of systemic dissemination is critically dependent on the development of an adaptive T1 immune response against the organism.22,23,24 Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are required for this protective response.25 In contrast, the development of a T2 response in the lungs is nonprotective and associated with persistence of C. neoformans.26,27,28,29 Experimentally altering the T1 versus T2 balance profoundly affects pulmonary clearance of the organism. Mice lacking interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) signaling, the major cytokine component of the T1 response, lose their ability to successfully clear cryptococcal infection.30 In contrast, depletion of the crucial T2 cytokines interleukin (IL)-4 or IL-13 reduces cryptococcal burden and increases host survival.31,32 Thus, the balance between a T1 versus T2 adaptive immune responses is a strong determinant defining the outcome of infections with C. neoformans.

Pulmonary dendritic cells (DCs) play an important role in defining the T1/T2 balance within the lung.33 Studies of DC interactions with Candida albicans have shown that differential expression of fungal factors may significantly alter DC phenotype, subsequent T cell polarization, and the outcome of the infection with this opportunistic pathogen.34,35 We have recently shown that large numbers of conventional DCs are recruited to the lung in response to cryptococcal infection.36 We have also shown that the adoptive transfer of immature DCs to mice infected with C. neoformans can bias the resultant immune response toward a T2 phenotype.37 To date, specific cryptococcal-derived factors that influence polarization of the adaptive immune response against C. neoformans have not been identified. We hypothesized that in addition to its effects on microvascular sequestration during fungemia, cryptococcal urease might impair local host defense within the lungs. We investigated this hypothesis using an established murine model comparing the effect of infection with urease-producing or urease-deficient strains of C. neoformans in mice.17 Specifically, we sought to determine whether cryptococcal urease expression influences the clearance of the organism and whether (and how) it might alter the development of T1 or T2 adaptive immune responses within the lung.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Mice (C57BL/6, Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in enclosed filter top cages at the University of Michigan Laboratory Animal Facility. Clean food and water were given ad libitum. The mice were handled and maintained using microisolator techniques with daily veterinarian monitoring. This study complied with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Dept. of Health, Education, & Welfare Publication No. 80-32) and followed a protocol approved by the Animal Care Subcommittee of the local Institutional Review Board.

C. neoformans

Three strains of C. neoformans were used in this study were kindly provided by Drs. Gary Cox and John Perfect from Duke University: 1) wt, the wild-type H99 strain that expresses urease; 2) ure1, a urease-negative transformant (knockout) of H99 with disruption of the native urease gene; and 3) ure1::URE1, a urease-expressing (revertant) strain in which strain ure1 has a wild-type copy of URE1 reintroduced. For the infection, yeast that were recovered from 10% glycerol stocks were grown to stationary phase (at least 72 hours) at 36°C in Sabouraud dextrose broth (1% neopeptone, 2% dextrose; Difco, Detroit, MI) on a shaker. The cultures were then washed in non-pyrogenic saline (Travenol, Deerfield, IL), counted on a hemocytometer, and diluted to 3.3 × 105 yeast cells/ml or to 3.3 × 107 in sterile non-pyrogenic saline.

Experimental Design

In all experiments, primary cryptococcal infection was induced in the lungs by intratracheal inoculation of C57BL/6 mice with either a urease-producing (wt or ure1::URE1) or urease-deficient (ure1) strain of C. neoformans on day 0. Thereafter, the following experiments were performed: 1) Analysis of pulmonary cryptococcal burden, by lung CFU assay, at weeks 1, 2, and 3 postinfection; 2) Enumeration of lung leukocytes, by visual identification, at weeks 1, 2, and 3; 3) Quantification of serum IgE levels, by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), at week 3; 4) Histological assessment of the lungs, by H&E staining and immunohistochemistry performed on lung sections, at week 3; 5) Determination of the expression of IL-4, IL-13, and IFN-γ by lung leukocyte cultures, using ELISA, at week 2, or intracellular cytokine staining using flow cytometric analysis; IL-4 and IFN-γ; at week 2; and 6) Enumeration and immunophenotyping of pulmonary DC in lung and lung associated lymph nodes by flow cytometric analysis, at weeks 1 and 2. Comparative analysis was performed between experimental groups infected with either urease-producing (wt or ure1::URE1) or urease-deficient (ure1) strains of C. neoformans.

Surgical Intratracheal Inoculation

Mice were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine mix (ketamine/xylazine 100/6.8 mg/kg/BW) and were restrained on a foam plate. A small incision was made through the skin over the trachea and the underlying tissue was separated. A bent 30-gauge needle (Becton Dickinson, Rutherford, NJ) was attached to a tuberculin syringe (BD & Co, Franklin Lakes, NJ) filled with the diluted C. neoformans culture. The needle was inserted into the trachea and 30 μl of inoculum dispensed into the lungs (104 yeast cells except where indicated). The skin was closed with cyanoacrylate adhesive. The mice recovered with minimal visible trauma.

Lung CFU Assay

Aliquots of the lung digest solutions were collected for lung CFU assays. Lung suspensions were serially diluted in sterile water. Dilution samples (10 μl each) were plated on Sabouraud dextrose agar and incubated at room temperature for 48 hours. Colony counts were performed and adjusted to reflect the total lung colony-forming units.

Detection of Urease Activity within Lung Tissue

C57BL/6 mice were inoculated by the intratracheal route with 106 wt or ure1 strains of C. neoformans. One week postinfection, lungs were dissected, homogenized, and incubated in 2 ml Christensen urea broth (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, MD.) at 37°C for 2 hours. Media color change (from light orange to red) indicates urease activity in the homogenized lung tissue.

Lung Leukocyte Isolation

The lungs from each mouse were excised, washed in PBS, minced with scissors, and digested enzymatically at 37°C for 30 to 35 minutes in 15 ml/lung of digestion buffer [RPMI, 5% fetal calf serum, antibiotics, and 1 mg/ml collagenase (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemical, Chicago, IL), and 30 μg/ml DNase (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO)]. The cell suspension and tissue fragments were further dispersed by repeated aspiration through the bore of a 10-ml syringe and were centrifuged. Erythrocytes in the cell pellets were lysed by addition of 3 ml of NH4Cl buffer (0.829% NH4Cl, 0.1% KHCO3, 0.0372% Na2EDTA, and pH 7.4) for 3 minutes, followed by a tenfold excess of RPMI. Cells were resuspended and a second cycle of syringe dispersion and filtration through a sterile 100 μm nylon screen (Nitex Kansas City, MO) was performed. The filtrate was centrifuged for 25 minutes at 1500 × g in the presence of 20% Percoll (Sigma) to separate leukocytes from cell debris and epithelial cells. Leukocyte pellets were resuspended in 5 ml of media, and enumerated on a hemocytometer following dilution in Trypan blue (Sigma).

Lung-Associated Lymph Node Leukocyte Isolation

Individual lung-associated lymph nodes (LALNs) were excised. To collect LALN leukocytes, nodes were dispersed using a 3-ml sterile syringe plunger and a flushed through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon) with complete media into a sterile tube. Following erythrocyte lysis (as above), cells were resuspended in complete medium and enumerated in the presence of trypan blue using a hemocytometer.

Visual Identification of Leukocyte Populations

To obtain differential cell counts of lung cell suspensions isolated from the lung digest, samples were cytospun (Shandon Cytospin, Pittsburgh, PA) onto glass slides and stained by a modification of the Diff-Quik whole blood stain (Diff-Quik, VWR Scientific Products). Samples were fixed/prestained for 2 minutes in a one-step, methanol-based, Wright-Giemsa stain (Harleco, EM Diagnostics, Gibbstown, NJ), rinsed in water, and stained using steps two and three of the Diff-Quik stain. This modification of the Diff-Quik stain procedure improves the resolution of eosinophils from neutrophils in the mouse. A total of 200 cells were counted for each sample from randomly chosen, high-power microscope fields.

Histology

Lungs were fixed by inflation with 1 ml of 10% neutral buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ), excised en bloc and immersed in neutral buffered formalin. After paraffin embedding, 5 μm sections were cut and stained with H&E ± counterstained with mucicarmine. Quantification of YM1 crystal deposition was assessed by identifying the number of crystals observed per high power (at ×400 magnification) field within inflamed regions of lungs from infected mice. Data represent the mean (±SEM) of at least 15 fields per experimental condition (n = 2 to 3 mice each). For immunohistochemistry, unstained paraffin sections were dewaxed and pretreated with hydrogen peroxide (Sigma) to eliminate residual peroxidase activity. Anti-Arginase1 antibody (BD Pharmingen) staining coupled with immunodetection using VECTOR M.O.M. Peroxidase Immunodetection kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. Sections were analyzed with light microscopy and microphotographs taken using Nikon Digital Microphotography system DFX1200 and ACT-1 software (Nikon Instrum. Inc., Melville, NY).

Cytokine Production

Isolated lung leukocytes were adjusted to 5 × 106 cells/ml in media, plated, and cultured at 37°C, 95% O2, and 5% CO2. After 24 hours, supernatants were separated from cells by centrifugation, collected, and frozen until tested. Reactions were performed in 96-well ELISA plates (Costar Corning Inc., Corniny, NY) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The optical densities were read on a microplate reader (Versa Max, MolecularDevices, Sunnyvale, CA) interpolation of sample optical density values with an appropriate standard by a four-parameter curve-fitting program.

Total Serum IgE Analysis

Blood was obtained by tail vein bleed of the mice. Following centrifugation to separate cells, serum was removed and total IgE concentrations were assessed using an IgE specific sandwich ELISA (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), read and analyzed as cytokine ELISAs described above.

Flow Cytometric Analysis

Leukocytes for the lung and LALN were harvested and single cell suspensions were generated as described above. Antibody staining, including blockade of Fc receptors, was performed as previously described.38 Antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Data were collected on a FACScan flow cytometer using Cell Quest software (both from Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, Mountain View, CA) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., San Carlos, CA). A minimum of 50,000 cells was analyzed per sample. Initial gates were set based on light scatter characteristics to exclude debris, red cells, and cell clusters. Identification and enumeration of DCs as cells expressing CD11c (FL-1 channel; fluorescein isothiocyanate) and MHC Class II (FL-2 channel; phycoerythrin) within single-cell suspensions generated from total lung leukocytes was performed using a gating strategy previously described in detail.39 These cells also express CD11b but not B220 and can therefore be defined as “conventional” DCs, (cDCs).36,40 Similarly, cDCs were defined within the LALN as cells expressing CD11c (fluorescein isothiocyanate) and MHC class II (I-Ab, phycoerythrin) as previously described.38,41 Cytometer parameters and gate position were held constant during analysis of all samples. The percent cDCs within each lung and LALN population was obtained after subtracting background events occurring within this gate in isotype control populations. The percentage of cDCs obtained from flow cytometry was used to calculate the total number of DC from each tissue by multiplying the frequency of cDCs by the total cell count for that sample.

Three-color analysis was then performed to assess the expression of CD80 on cDCs identified within LALN populations.41 Specifically, the expression of CD80 was determined using biotinylated anti-CD80 antibody, followed by streptavidin-conjugated peridinin chlorophyll. CD80 expression was defined (in the FL3 channel) as either high or low based on values of mean fluorescence intensity relative to an isotype control. The total number of CD80hi and CD80lo DCs was determined by multiplying their frequency by the total number of LALN leukocytes.

Calculations and Statistics

Data (mean ± SE) for each experimental group were derived from at least 2 independent infections (of compared groups of animals) and analyzed using Primer of Biostatistics Software, Version 4.0 (McGraw Hill, Columbus, OH) via t-test, one way or two-way analysis of variance, depending on the experimental design. For individual comparisons of multiple groups, Student-Newman-Keuls posthoc test was used to calculate P values. To calculate IL-4:IFN-γ ratios, the ratio of paired cytokine samples for each mouse was determined and then averaged. A Kruskal-Wallis analysis was performed followed by a Dunn’s posthoc test to compare ratios between individual groups. Means with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

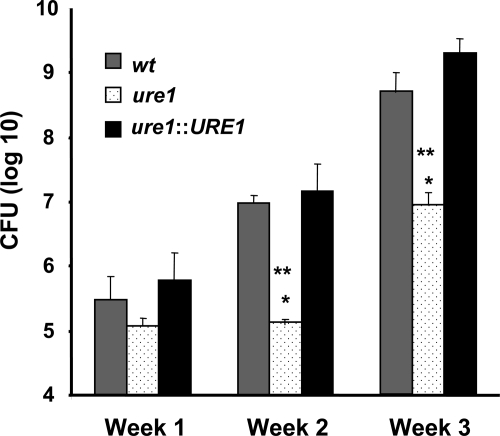

Cryptococcal Urease Is Associated with Impaired Clearance of C. neoformans from the Lung

Our previous study demonstrated that urease is not required for the acute growth/survival of C. neoformans in the lungs as assessed at very early time-points (days 1 and 4) post–infection.17 However, clearance of C. neoformans from the lungs does not occur until T1-polarized effector T-cells are recruited during second and third week of the infection.42,43 To determine whether cryptococcal urease expression would affect clearance of the organism at these later timepoints, lung CFU of mice infected with either wt, ure1, or ure1::URE1 strains of C. neoformans were compared at weeks 1, 2, and 3 post–infection (Figure 1). Results demonstrate no difference in microbial burden within the lungs of mice infected with each of these three strains at week 1 post–infection. Infection with urease-producing C. neoformans (wt and ure1::URE1) was associated with a 100-fold increase in cryptococcal burden within the lung at week 2 and week 3 postinfection compared with mice infected with the urease-deficient strain (ure1).

Figure 1.

Effect of cryptococcal urease on fungal clearance. Mice were intratracheally infected with 104 C. neoformans and lungs were harvested at weeks 1, 2, and 3 post–infection for analysis of fungal burden. Data, pooled from separate matched experiments, are expressed as the mean CFU per lung ± SE from mice infected with the following strains: wt (strain H99, urease-producing; gray bars, n = 14 week1, n = 33 week 2, n = 12 week 3), ure1 (knockout strain, urease-deficient; white speckled bars, n = 13 week 1, n = 13 week 2, n = 5 week 3), and ure1::URE1 (revertant strain, urease-producing; black bars, n = 7 week 1, n = 17 week 2, n = 7 week 3). *P < 0.05, in comparison with wt, **P < 0.05, in comparison with ure1::URE1 infected mice.

To verify that these biological differences were attributable to the expression of cryptococcal urease within the lung, we used a colorimetric assay (see Materials and Methods) to detect urease enzymatic activity in lung homogenates from infected mice. Results from two independent experiments confirmed that cryptococcal urease enzymatic activity was only detected in the lungs of mice infected with wt but not ure1 strains of C. neoformans (data not shown). Collectively, these findings suggest that cryptococcal urease expression does not enhance C. neoformans growth rate in the lungs during the period of the initial innate immune response. However, cryptococcal urease expression is associated with impaired clearance of pulmonary C. neoformans growth at later time points suggesting a detrimental effect of urease on the ensuing adaptive immune response.

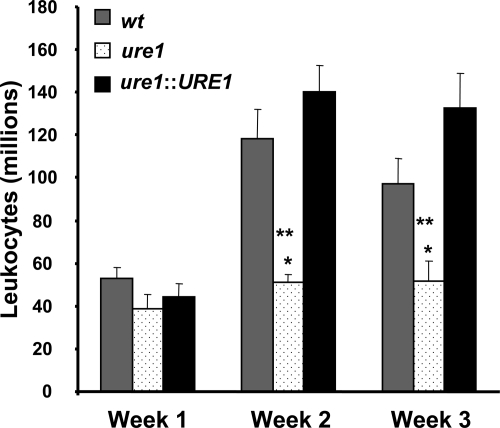

Cryptococcal Urease Does Not Impair Pulmonary Leukocyte Recruitment

The impaired clearance of urease-producing C. neoformans might result from either an insufficient (weak) immune response to the pathogen or by the generation of a non-protective immune response in the lungs. To determine the effect of cryptococcal urease expression on pulmonary leukocyte recruitment, we evaluated the total numbers of recruited lung leukocytes at weeks 1, 2, and 3 post–infection from mice infected with wt, ure1, or ure1::URE1 strains of C. neoformans. By week 2 post–infection, significantly greater numbers of leukocytes were recruited into the lungs of mice infected with wt and ure1::URE) as compared with lungs infected with ure1 (Figure 2). Thus, cryptococcal urease production did not impair leukocyte recruitment; rather the resultant inflammatory response in the lung was non-protective.

Figure 2.

Effect of cryptococcal urease on pulmonary leukocyte recruitment. Mice were intratracheally infected with 104 C. neoformans. Lungs were harvested at weeks 1, 2, and 3 post–infection and total lung leukocytes were isolated from infected lungs following enzymatic digestion and assessed by visual identification (see Materials and Methods). Data were pooled from separate matched experiments and expressed as mean absolute numbers of recruited leukocytes per lung ± SE for mice infected with the following strains of C. neoformans: wt (strain H99, urease-producing; gray bars), ure1 (knockout strain, urease-deficient; white speckled bars), and ure1::URE1 (revertant strain, urease-producing; black bars). *P < 0.05, in comparison with wt, **P < 0.05, in comparison with ure1::URE1 infected mice (n = 5 to 33 per group of infected mice as per Figure 1).

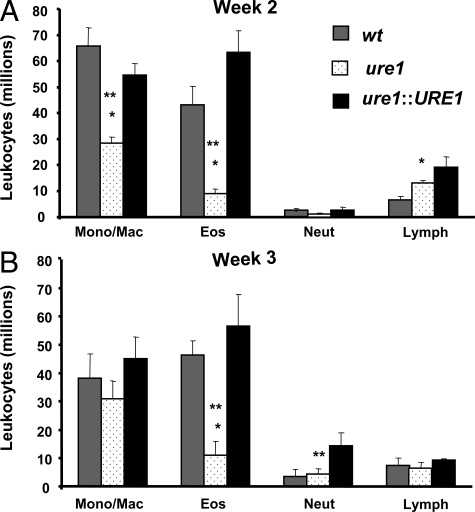

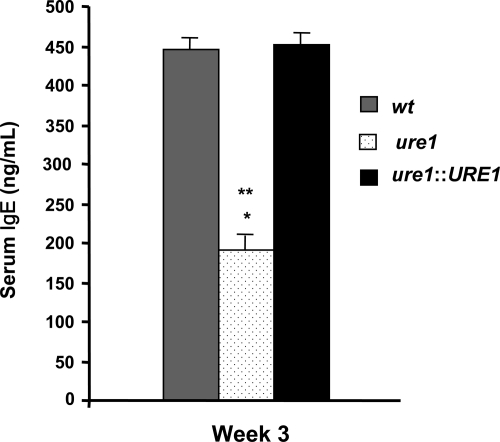

Cryptococcal Urease Expression Is Associated with the Development of Pulmonary Eosinophilia and Increased IgE Production

Our finding of increased lung leukocyte recruitment in mice infected with urease-producing strains of C. neoformans suggests that this robust immune response is nonetheless ineffective at clearing the organism. We next assessed whether cryptococcal urease production promoted differential recruitment of lung leukocyte populations. Mice were infected with wt, ure1, or ure1::URE1 strains of C. neoformans and leukocyte subsets were evaluated in enzymatically-digested lungs at weeks 2 and 3 postinfection (Figure 3, A and B). Mice infected with wt and ure1::URE1 were observed to have a persistent increase in the number of lung eosinophils as compared with infection with ure1. Monocyte/macrophage populations were transiently reduced (week 2 post–infection) in the absence of cryptococcal urease. We also observed that mice infected with wt and ure1::URE1 had higher levels of serum IgE than mice infected with ure1 (Figure 4). Our published data have documented that persistent pulmonary eosinophilia and increased serum IgE during C. neoformans infection is T cell-dependent and specifically associated with the development of a highly polarized T2 response.29,41 Thus, the increased pulmonary eosinophilia and elevated levels of serum IgE observed in mice infected with urease-producing C. neoformans suggest that cryptococcal urease is associated with a pulmonary T2 adaptive immune response.

Figure 3.

Effect of cryptococcal urease on recruitment of leukocyte subsets. Mice were intratracheally infected with 104 C. neoformans. Lungs harvested at weeks 2 (A) and 3 (B) post–infection were enzymatically digested and lung leukocyte subsets were assessed by visual identification (see Materials and Methods). Data were pooled from separate matched experiments and expressed as mean absolute numbers of recruited leukocytes per lung ± SE for mice infected with the following strains of C. neoformans: wt (strain H99, urease-producing; gray bars), ure1 (knockout strain, urease-deficient; white speckled bars), and ure1::URE1 (revertant strain, urease-producing; black bars). *P < 0.05, in comparison with wt, **P < 0.05, in comparison with ure1::URE1 infected mice (n = 5 to 33 per group of infected mice as per Figure 1).

Figure 4.

Effect of cryptococcal urease on the production of serum IgE. Total serum IgE concentrations were measured by ELISA at 3 weeks post–infection C. neoformans. Bars represent mean serum IgE concentration ± SE from mice infected with the following strains of C. neoformans: wt (strain H99, urease-producing; gray bars), ure1 (knockout strain, urease-deficient; white speckled bars), and ure1::URE1 (revertant strain, urease-producing; black bars). *P < 0.05, in comparison with wt, **P < 0.05, in comparison with ure1::URE1 infected mice (n = 6 to 7 per group of infected mice).

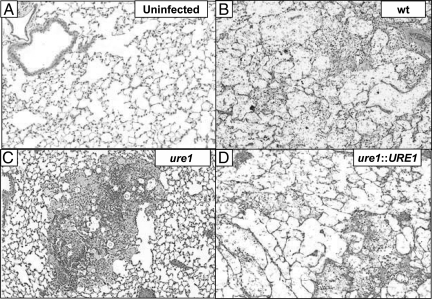

Diffuse Infiltrates Containing Eosinophils and Alternatively Activated Macrophages Are Prevalent in the Lungs of Mice Infected with Urease-Producing Strains of C. neoformans

Histopathological examination of lungs infected with wt, ure1, or ure1::URE1 strains of C. neoformans was performed at week 3 post–infection to determine the effect of cryptococcal urease on lung pathology (Figure 5, A–D). In mice infected with wt or ure1::URE1 we observed diffuse growth of C. neoformans and the presence of numerous eosinophils within loosely organized infiltrates in the inflamed areas of the lungs (Figure 5, B and D). In addition, we observed large extended macrophages containing multiple cryptococci, which suggested decreased intracellular killing of C. neoformans by macrophages. In contrast, mice infected with ure1 had fewer eosinophils. Instead, dense granuloma-like nodules and bronchovascular infiltrates were observed surrounding the infected areas of the lungs (Figure 5C). This pattern of inflammation has been associated with protective T1 responses against C. neoformans.29,36,41

Figure 5.

Effect of cryptococcal urease on the morphological pattern of pulmonary inflammation. Mice were either uninfected (A) or intratracheally infected (B–D) with 104 C. neoformans. Representative photomicrographs (H&E-stained; ×100 magnification) taken of lung sections harvested (3 weeks post–infection) from mice which were (A) uninfected or infected with one of the following strains of C. neoformans: B: wt (H99; urease-producing), ure1 (C urease-deficient knockout), or ure1: URE1 (D urease-producing revertant). Note the diffuse infiltrates in mice infected with urease-producing strains (wt, panel B and ure1::URE1, panel D), which consisted of loose conglomerates of visible C. neoformans, eosinophils and macrophages. In contrast, infiltrates in mice infected with the urease-deficient strain (ure1, panel C) contained tightly packed granulomas and bronchovascular infiltrates in which extracellular C. neoformans and eosinophils were notably diminished.

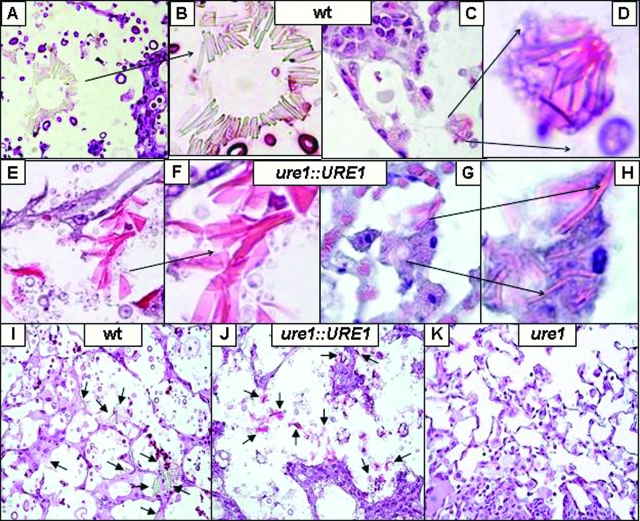

The presence of eosinophils and macrophages containing intracellular cryptococci (in the lungs of mice infected with urease-producing C. neoformans) suggests that these macrophages might be alternatively activated.26,44 We therefore evaluated these lungs for evidence of YM1 crystal deposition, a hallmark of alternatively activated macrophages (Figure 6). Both intracellular and extracellular YM1 crystals were abundant in the areas heavily infected with wt (11.3 ± 2 crystals/hpf, Figure 6, A–D, I), or ure1::URE1 (30.9 ± 3 crystals/hpf, Figure 6, E–H, J). In contrast, YM1 crystals were rarely observed in the lungs of mice infected with ure1 (0.3 ± 0.1 crystals/hpf, Figure 6K; P < 0.001 versus wt or ure1::URE1 by unpaired student t-test).

Figure 6.

Effect of cryptococcal urease on pulmonary YM1 crystal deposition. Mice were intratracheally infected with 104 C. neoformans. Representative photomicrographs of lung sections (3 weeks post–infection) stained with H&E followed by counterstaining with mucicarmine (to identify C. neoformans) from mice that were infected with wt (urease-producing H99, A–D, I), ure1::URE1 (urease-producing revertant, E–H, J), or ure1 (urease-deficient knockout, K). At high power magnification (A, C, E, G ×400 magnification; B, D, F, H ×1000 magnification), note the presence of both intracellular and extracellular YM1 crystals (arrows) in the lungs of mice infected with wt or ure1::URE1 (urease-producing). At low power magnification (I–K, ×200 magnification), note the absence of crystals in the lungs of mice infected with ure1 (urease-deficient).

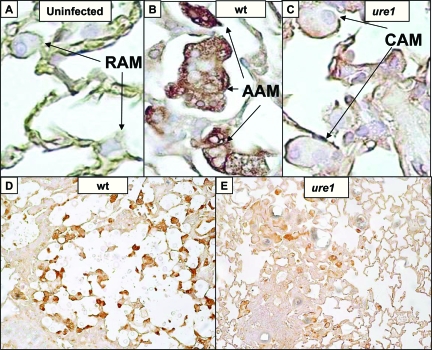

Expression of arginase was evaluated to further investigate the activation status of pulmonary macrophages (Figure 7). Minimal arginase expression was observed within resting alveolar macrophages identified within the lungs of uninfected mice (Figure 7A). In contrast, robust expression of arginase was detected in macrophages identified in the lungs of mice infected with wt C. neoformans (Figure 7, B and D) consistent with alternative activation. Mice infected with ure1, displayed weak arginase expression (Figure 7, C and E) suggesting the presence of classically activated macrophages. Collectively, the finding of diffuse infiltrates containing eosinophils and alternatively activated macrophages in the lungs of mice infected with urease-producing C. neoformans confirms that cryptococcal urease is strongly associated with the classic histopathological findings of a pulmonary T2 immune response.

Figure 7.

Effect of cryptococcal urease on arginase expression by pulmonary macrophages. Mice were either uninfected (A) or intratracheally infected with 104 C. neoformans (B–E). A–C: Representative high power (×1000 magnification) photomicrographs taken of lung sections stained with anti-Arginase1 antibody (peroxidase detection, brown substrate) from (A) uninfected mice or mice infected 2 weeks with (B) wt (urease-producing H99) or (C) ure1 (urease-deficient knockout) strains of C. neoformans. Note the absence of staining in resting alveolar macrophages (RAM; panel A), whereas strong staining indicative of alternatively-activated macrophages (AAM) was evident in mice infected with the urease-producing strain (wt; panel B). In contrast, weak staining suggestive of classically activated macrophages (CAM) was noted in mice infected with the urease-deficient strain (ure1; panel C). D, E: Representative low power (×200 magnification) photomicrographs demonstrate that AAM (strong arginase expression) are more abundant in the lungs of mice infected with wt (D) compared with ure1 (E).

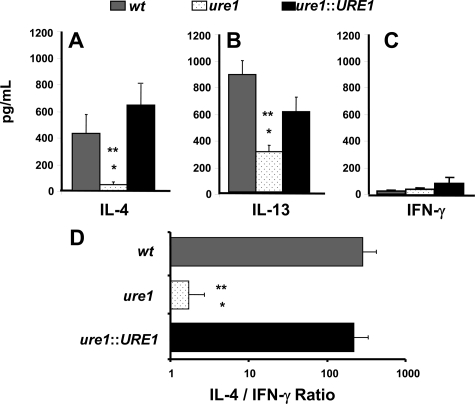

T2 Cytokine Production Is Increased in Mice Infected with Urease-Producing Strains of C. neoformans

Protective T1 immune responses against C. neoformans are most strongly associated with T cell production of IFN-γ and the classical activation of lung macrophages.27 In contrast, non-protective T2 responses are characterized by the induction of IL-4 and IL-13, which promote the development of alternatively-activated macrophages.26,27 To compare the effect of cryptococcal urease on the T1 versus T2 cytokine profiles, we evaluated the production of these cytokines by pulmonary leukocytes isolated from mice infected with wt, ure1, or ure1::URE1 strains of C. neoformans at week 2 post–infection (Figure 8). Leukocytes isolated from mice infected with wt or ure1::URE1 demonstrated a large increase in IL-4 and IL-13 expression (Figure 8, A and B) whereas IFN-γ remained low (Figure 8C). This increase in IL-4 and IL-13 induction resulted in a significantly increased IL-4:IFN-γ ratio in mice infected with wt or ure1::URE1 compared with mice infected with ure1 (Figure 8D).

Figure 8.

Effect of cryptococcal urease on pulmonary cytokine production. Total lung leukocytes were isolated 2 weeks post–infection with C. neoformans and cultured for 24 hours at 5 × 106 cells/ml in the absence of any stimulation. Supernatants were harvested, and cytokine levels were detected by ELISA. Bars represent mean cytokine (A, IL-4; B, IL-13; C, IFN-γ) concentration ± SE (pg/ml) or (D), the IL-4/IFN-γ ratio, for paired leukocyte cultures obtained from the lungs of individual mice infected with the following strains of C. neoformans: wt (strain H99, urease-producing; gray bars), ure1 (knockout strain, urease-deficient; white speckled bars), and ure1::URE1 (revertant strain, urease-producing; black bars). *P < 0.05, in comparison with wt, **P < 0.05, in comparison with ure1::URE1 infected mice (n = 6 to 7 per group of infected mice).

We performed intracellular staining for IL-4 and IFN-γ at week 2 postinfection to confirm that both CD4+ and CD8+ cells polarization was affected by cryptococcal urease expression. In the lungs of mice infected with ure1::URE1, we found a fourfold increase in the numbers of IL-4 positive CD4 cells and fivefold increase in IL-4 positive CD8 cells, as compared with the lungs infected with ure1 (1.1 ± 0.3 vs. 4.4 ± 0.3 and 1.1 ± 0.4 vs. 5.1 ± 0.6, respectively; data not shown). Within the LALN, urease production was associated with a significant decrease in the frequency of IFN-γ producing T cells (data not shown). Thus, the key effector cytokines (IL-4 and IL-13) known to mediate T2 immune responses are strongly enhanced in the presence of cryptococcal urease. Taken together, these data supports our conclusion that cryptococcal urease promotes T2 responses and further focuses our investigations on the potential mechanism(s) through which this effect on T cell polarization is mediated.

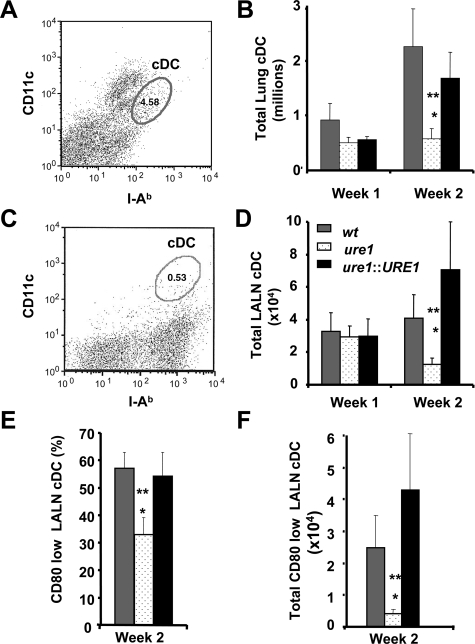

Cryptococcal Urease Production Is Associated with Increased Numbers of Immature cDCs within the Lung Associated Lymph Nodes

DCs are potent antigen presenting cells and are critical determinants of T-cell polarization. The role of DCs in mediating host defense against C. neoformans remains incompletely understood as they have been implicated in promoting both protective and non-protective responses to C. neoformans.37,45 Our objective was to determine whether cryptococcal urease expression had an effect on the numbers and phenotype of pulmonary DC. Flow cytometric analysis was used to identify cDCs as CD11c+/MHC Class II+ cells (see methods) from the lung (Figure 9, A and B) and lung-associated lymph nodes (LALN; Figure 9, C–F) at weeks 1 and 2 postinfection with wt, ure1, or ure1::URE1 strains of C. neoformans. No significant difference in DC recruitment was observed 1 week postinfection. In contrast, pulmonary infection with either wt or ure1::URE1 resulted in significantly increased numbers of cDC in both the lung and LALN by week 2, as compared with infection with ure1. Thus, more cDCs were recruited to lung and LALNs following infection with urease-producing C. neoformans.

Figure 9.

Effect of cryptococcal urease on the number and phenotype of conventional dendritic cells. Flow cytometric analysis was performed to identify conventional dendritic cells (cDC) among leukocytes obtained from the lung (A, B) and lung associated lymph nodes (LALN; C–F) 2 weeks following infection with C. neoformans. A, C: Representative histogram demonstrating the gating strategy used to identify cDC (oval gates) among lung (A), and LALN (C) leukocytes as cells expressing modest to high amounts of both MHC Class II (I-Ab; FL-1 channel, fluorescein isothiocyanate) and CD11c (FL-2 channel, phycoerythrin). B, D: Total numbers of cDC within leukocyte populations were determined by multiplying the frequency of cDC by the total number of leukocytes present in each tissue. Bars represent the mean number of DC in lung (B), and LALN (D) ± SE from mice infected with the following strains of C. neoformans: wt (strain H99, urease-producing; gray bars), ure1 (knockout strain, urease-deficient; white speckled bars), and ure1::URE1 (revertant strain, urease-producing; black bars). E, F: Three color flow cytometric analysis was performed on cDC identified within LALN at 2 weeks postinfection and assessed for the expression of the costimulatory molecule, CD80 (FL-3, PerCp). Results are expressed as the percentage (E) and total number (F) of CD80low cDC identified within LALN leukocytes (same key as above). Bars represent mean ± SE, n = at least three animals per group, *P < 0.05, in comparison with wt, **P < 0.05, in comparison with ure1::URE1 infected mice.

CD80 (B7.1) is a major co-stimulatory molecule required for the generation of a protective T1 response.46,47 High expression of CD80 characterizes fully mature cDCs while low expression characterizes immature cDCs. Antigen-specific stimulation of naïve T cells by immature DCs has been demonstrated to promote T2 polarization in mice infected with C. neoformans.37 To determine whether cDCs within LALNs were mature or immature, the frequency and total numbers of CD80low cDCs in the LALN were examined at 2 weeks postinfection with either wt, ure1, or ure1::URE1 strains of C. neoformans. The frequency (Figure 9E) and number (Figure 9F) of CD80low (ie, immature) cDCs present in the LALN of mice infected with wt or ure1::URE1 were significantly higher by week 2 postinfection compared with ure1. These data suggest that cryptococcal urease production increases in the number of immature DCs residing within the LALN at the onset of the adaptive immune response. The resultant T cell stimulation by the enhanced numbers of immature DCs within the LALN provides one possible mechanistic link whereby cryptococcal urease promotes non-protective T2 responses within the lung.

Discussion

In this study, we used a well-established murine model to investigate the effect of cryptococcal urease on host defense against C. neoformans specifically within the lung. We report the following novel findings. First, cryptococcal urease expression is associated with impaired clearance of C. neoformans within the lungs of infected mice. Second, this increased microbial burden associated with urease-producing C. neoformans occurs despite an increase in the total number of lung leukocytes in these mice. Third, we demonstrate that this nonprotective immune response in mice infected with urease-producing C. neoformans results from T2 polarization as characterized by increased lung eosinophils, serum IgE, and alternatively activated macrophages. Our finding of enhanced production of the T2 cytokines (IL-4 and IL-13) in the lungs of mice infected with urease-producing C. neoformans further confirms the presence of T2 polarization and suggests an effect of cryptococcal urease on antigen presentation. Finally, we report that infection with urease-producing C. neoformans results in increased numbers of immature DC in the lung-associated lymph nodes, a phenotype known to promote T2 polarization against the organism.

Our previous studies document that urease is an important virulence factor for C. neoformans that enhances cryptococcal dissemination into the CNS.17 In that study, we demonstrated that cryptococcal urease enhances microvascular sequestration of the organism within capillary beds in the brain, which leads to lethal meningoencephalitis. Here we show that cryptococcal urease expression also impairs the clearance of the organism from the lung. The kinetics with which C. neoformans is cleared from the lungs in these studies is noteworthy. Within the first week post–infection, the presence or absence of urease does not affect the clearance of C. neoformans within the lung. This is consistent with our prior study in which urease expression did not impair pulmonary growth rate of C. neoformans during the early/innate phase of the immune response.17 In addition, we previously demonstrated that urease expression did not impair primary macrophage phagocytosis of C. neoformans.17 However, in the original inhalational model of C. neoformans infection reported by Cox et al, they suggested that mice infected with urease-producing strains developed respiratory distress.16 Our data clarify this apparent discrepancy. We now show that although urease expression does not enhance the immediate growth rate of the organism in lungs in vivo, it is associated with impaired clearance of the organism at weeks 2 and 3 postinfection. This time point coincides with the development of T cell polarization in this model system.25,41,43 Thus, we have defined cryptococcal urease as a virulence factor that exerts a strong effect at the later stages of the host response against the organism specifically within the lung (the primary site of infection).

The kinetics of this impairment in fungal clearance directed us to investigate the effect of cryptococcal urease on the adaptive immune response. The observation that recruited leukocytes were increased in the lungs of mice infected with urease-producing C. neoformans, despite impaired clearance, suggests that this response was ineffective. We observed that cryptococcal urease expression correlated with increased tissue eosinophilia and serum IgE levels. T2 cytokine production (IL-4 and IL-13) and the IL-4:IFN-γ ratio were markedly increased (in the presence of urease) demonstrating that the balance of the immune response has shifted toward a highly polarized T2 response. We and others have shown that the T2 responses against C. neoformans, although vigorous, are nonprotective and are associated with persistent infection.24,26,29,31 The phenotype observed in mice infected with urease-deficient C. neoformans is similar to that identified in IL-4 knockout mice infected with urease-producing C. neoformans (ie, improved cryptococcal clearance, reduced lung eosinophilia, and a reduced IL-4:IFN-γ ratio).25 Thus, the data suggest that cryptococcal urease promotes T cell polarization toward nonprotective T2 phenotype.

Our comparative histopathological analysis of mice infected with urease-producing and urease-deficient C. neoformans emphasizes the degree to which cryptococcal urease promotes pulmonary immunopathology. The lungs of mice infected with urease-producing C. neoformans were characterized by extensive, loose alveolar infiltrates containing eosinophils and macrophages. Extracellular cryptococci were more numerable and could also be readily identified within lung macrophages. These macrophages showed accumulation of YM1 crystals and enhanced arginase expression indicative of alternative activation. Alternatively-activated macrophages (AAM) are induced by T2 cytokines (IL-4 and IL-13) and are massively increased in the lungs of mice over-expressing IL-13.27,48 Arginase competes with iNOS for arginine, thereby reducing the substrate by which iNOS produces NO and resultant production of reactive nitrogen species. Increased arginase to iNOS ratio has been reported to decrease intracellular killing of yeast by macrophages resulting in an increased fungal burden.27,32,49 In the absence of cryptococcal urease, extracellular cryptococci were decreased and we identified numerous tightly formed granulomas and dense bronchovascular infiltrates. We have recently reported these microanatomic structures are associated with T1 immune responses within the lungs of mice infected with C. neoformans.36,41

Our characterization of DC accumulation and phenotype provides significant insight into the mechanism(s) through which cryptococcal urease promotes T2 immune responses in this model system. We observed that immature cDC were significantly increased in the LALN of mice infected with urease-producing strains of C. neoformans. We have previously shown that mice stimulated with immature DC develop enhanced T2 responses against C. neoformans in vivo.37,41 Our present data suggests that cryptococcal urease increases the likelihood that an antigen specific T cell-DC interaction in LALN entails phenotypically immature DCs. We propose that the resultant T cell response is thereby skewed toward a T2 phenotype resulting in immune deviation, which contributes to impaired clearance and immune-mediated pathophysiology. This hypothesis is supported by a recent study by Mukai et al in their investigation of the effects of urease generated by another intracellular pathogen, Mycobacterium bovis (BCG). Their results demonstrate that bone-marrow derived DCs and macrophages display impaired maturation in response to urease-expressing strain of BCG, when compared with a mutant strain lacking urease).50 This defect was linked to impaired phagosomal acidification and maturation due to the enzymatic activity of urease (which degrades urea to ammonia). Furthermore, T cells stimulated by DCs pulsed with urease-producing BCG expressed more IL-13 and less IFN-γ than T cells stimulated by urease-deficient BCG pulsed DCs. These mechanisms outlined for BCG-induced urease in vitro are in line with the immunological effects of urease expression by C. neoformans observed in our in vivo model of pulmonary infection.

Our in vivo studies demonstrate that cryptococcal urease production increases the microbial load in the lung and CNS and is associated with increased mortality. However, the urease-deficient strain (ure1) is not cleared from the lungs. This residual virulence retained by ure1 is likely a result of other factors (encapsulation, phospholipase, laccase/melanin production, growth at 37°C16) that continue to be expressed. The critical finding of our study is that cryptococcal urease further contributes to cryptococcal virulence by dramatically enhancing a non-protective T2 response. This effect is not limited to C57BL/6 mice as urease expression is also associated with enhanced T2 responses (increased lung eosinophils and IL-4 production) in the lungs of BALB/c mice (a strain of mice genetically predisposed toward T1 polarization41). A recent study by Guerrero et al51 proposed that certain mucoid strains of C. neoformans should be considered as Class III pathogens due to the host damage elicited by an over-exuberant inflammatory response. Interpretation of our data in the context of this “damage response” framework of microbial pathogenesis52,53 could also imply that urease-expression favors a switch from a Class II to a Class III pathogen due to the potential damage caused by tissue eosinophils and crystal deposition by urease-producing strains of C. neoformans.54

In summary, this is the first study to examine, in detail, the role of cryptococcal urease as a pulmonary virulence factor during fungal infection. Our results demonstrate that infection with urease-producing C. neoformans promotes a vigorous T2 adaptive immune response, which is ineffective at clearing the organism. Our data specifically implicate the effect of cryptococcal urease on the accumulation of immature pulmonary DCs within local lymph nodes as a mechanism through which the virulence of urease-producing fungi is enhanced in vivo. These findings suggest that approaches to inhibit cryptococcal urease and/or enhance DC maturation might improve the efficacy of vaccines or novel therapeutics designed to prevent or treat invasive fungal infections.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Drs. John Perfect and Gary Cox for providing urease knockout and revertant mutants. We thank Rod McDonald, Nicole Falkowski and David McNamara for their assistance in different parts of this project; and the Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program at University of Michigan for the support.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Michal A. Olszewski, D.V.M., Ph.D., Ann Arbor Veterans Administration Health System (11R), 2215 Fuller Rd., Ann Arbor, MI 48105. E-mail: olszewsm@umich.edu.

Supported in part by Merit Review awards (M.A.O. and G.B.T.), a Career Development Award (J.J.O.), and a Research Enhancement Award Program (G.B.T., J.L.C. and M.A.O.) from the Department of Veterans Affairs; by T32-HL07749 (J.E.M.), R01-HL63670 (G.B.H.), R01-HL65912 (G.B.H.), R01-HL51082 (G.B.T.), R01-HL082480 (J.L.C.), and R01-HL056309 (J.L.C.) from the National Institutes of Health; and by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (G.B.H.).

J.J.O., R.S., and J.E.M. contributed equally to this work.

References

- Berkefeld J, Enzensberger W, Lanfermann H. Cryptococcus meningoencephalitis in AIDS: parenchymal and meningeal forms. Neuroradiology. 1999;41:129–133. doi: 10.1007/s002340050717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hage CA, Wood KL, Winer-Muram HT, Wilson SJ, Sarosi G, Knox KS. Pulmonary cryptococcosis after initiation of anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. Chest. 2003;124:2395–2397. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.6.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs JA, Kovacs AA, Polis M, Wright WC, Gill VJ, Tuazon CU, Gelmann EP, Lane HC, Longfield R, Overturf G, Masher AM, Fauci AS, Parrillo JE, Bennett JE, Masur H. Cryptococcosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:533–538. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-4-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SC, Dickson DW, Casadevall A. Pathology of cryptococcal meningoencephalitis: analysis of 27 patients with pathogenetic implications. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:839–847. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90459-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang LMN, Maguire JA, Doyle P, Fyfe M, Roscoe DL. Cryptococcus neoformans infections at Vancouver Hospital and Health Sciences Centre (1997–2002): epidemiology, microbiology and histopathology. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:935–940. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahra LV, Azzopardi CM, Scott G. Cryptococcal meningitis in two apparently immunocompetent Maltese patients. Mycoses. 2004;47:168–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2004.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofman V, Venissac N, Mouroux C, Butori C, Mouroux J, Hofman P. [Disseminated pulmonary infection due to Cryptococcus neoformans in a non immunocompromised patient]. Ann Pathol. 2004;24:187–191. doi: 10.1016/s0242-6498(04)93945-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock R, Buchanan KL, Cherniak R, Mitchell TG, Wong B, Bartiss A, Jackson L, Murphy JW. Pathogenesis of Cryptococcus neoformans is associated with quantitative differences in multiple virulence factors. Mycopathologia. 1999;147:1–11. doi: 10.1023/a:1007041401743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan KL, Murphy JW. What makes Cryptococcus neoformans a pathogen? Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:71–83. doi: 10.3201/eid0401.980109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panepinto JC, Williamson PR. Intersection of fungal fitness and virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6:489–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock R, Buchanan KL, Adesina AM, Murphy JW. Differential regulation of immune responses by highly and weakly virulent Cryptococcus neoformans isolates. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3601–3609. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3601-3609.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffnagle GB, Chen GH, Curtis JL, McDonald RA, Strieter RM, Toews GB. Down-regulation of the afferent phase of T cell-mediated pulmonary inflammation and immunity by a high melanin-producing strain of Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 1995;155:3507–3516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski MA, Huffnagle GB, Traynor TR, McDonald RA, Cook DN, Toews GB. Regulatory effects of macrophage inflammatory protein 1alpha/CCL3 on the development of immunity to Cryptococcus neoformans depend on expression of early inflammatory cytokines. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6256–6263. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6256-6263.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami K, Tohyama M, Xie Q, Saito A. IL-12 protects mice against pulmonary and disseminated infection caused by Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;104:208–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.14723.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami K, Qifeng X, Tohyama M, Qureshi MH, Saito A. Contribution of tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in host defence mechanism against Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;106:468–474. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-870.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox GM, Mukherjee J, Cole GT, Casadevall A, Perfect JR. Urease as a virulence factor in experimental cryptococcosis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:443–448. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.443-448.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski MA, Noverr MC, Chen GH, Toews GB, Cox GM, Perfect JR, Huffnagle GB. Urease expression by Cryptococcus neoformans promotes microvascular sequestration, thereby enhancing central nervous system invasion. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1761–1771. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63734-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadevall A, Perfect JR. Cryptococcus neoformans. Washington DC: ASM Press,; 1998:541. [Google Scholar]

- Manelis J, Reichenthal E, Merzbach D, Haschman N, Peyser E. Cryptococcus neoformans meningitis. Report of a case and review of cryptococcosis in Israel. Confin Neurol. 1973;35:304–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poo QM, Paul FM. Cryptococcus neoformans meningitis in a school girl. J Singapore Paediatr Soc. 1977;19:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalaburgi SB, Mohapatra KC. Cryptococcus neoformans meningitis: a case report. S Afr Med J. 1980;57:1011–1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffnagle GB, Lipscomb MF, Lovchik JA, Hoag KA, Street NE. The role of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the protective inflammatory response to a pulmonary cryptococcal infection. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;55:35–42. doi: 10.1002/jlb.55.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami K, Koguchi Y, Qureshi MH, Yara S, Kinjo Y, Miyazato A, Nishizawa A, Nariuchi H, Saito A. Circulating soluble CD4 directly prevents host resistance and delayed-type hypersensitivity response to Cryptococcus neoformans in mice. Microbiol Immunol. 2000;44:1033–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2000.tb02600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynor TR, Kuziel WA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. CCR2 expression determines T1 versus T2 polarization during pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection. J Immunol. 2000;164:2021–2027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindell DM, Ballinger MN, McDonald RA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Diversity of the T-cell response to pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4538–4548. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00080-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez Y, Arora S, Erb-Downward JR, McDonald RA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Distinct roles for IL-4 and IL-10 in regulating T2 immunity during allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis. J Immunol. 2005;174:1027–1036. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora S, Hernandez Y, Erb-Downward JR, McDonald RA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Role of IFN-gamma in regulating T2 immunity and the development of alternatively activated macrophages during allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis. J Immunol. 2005;174:6346–6356. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora S, McDonald RA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Effect of a CD4-depleting antibody on the development of Cryptococcus neoformans-induced allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis in mice. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4339–4348. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01989-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski MA, Huffnagle GB, McDonald RA, Lindell DM, Moore BB, Cook DN, Toews GB. The role of macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha/CCL3 in regulation of T cell-mediated immunity to Cryptococcus neoformans infection. J Immunol. 2000;165:6429–6436. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GH, McDonald RA, Wells JC, Huffnagle GB, Lukacs NW, Toews GB. The gamma interferon receptor is required for the protective pulmonary inflammatory response to Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1788–1796. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1788-1796.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock R, Murphy JW. Role of interleukin-4 in resistance to Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;30:109–117. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0156OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller U, Stenzel W, Kohler G, Werner C, Polte T, Hansen G, Schutze N, Straubinger RK, Blessing M, McKenzie AN, Brombacher F, Alber G. IL-13 induces disease-promoting type 2 cytokines, alternatively activated macrophages and allergic inflammation during pulmonary infection of mice with Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 2007;179:5367–5377. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermaelen K, Pauwels R. Pulmonary dendritic cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:530–551. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200410-1384SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani L, Bistoni F, Puccetti P. Fungi, dendritic cells and receptors: a host perspective of fungal virulence. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:508–514. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(02)02460-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellocchio S, Montagnoli C, Bozza S, Gaziano R, Rossi G, Mambula SS, Vecchi A, Mantovani A, Levitz SM, Romani L. The contribution of the toll-like/IL-1 receptor superfamily to innate and adaptive immunity to fungal pathogens in vivo. J Immunol. 2004;172:3059–3069. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterholzer JJ, Curtis JL, Polak T, Ames T, Chen GH, McDonald R, Huffnagle GB, Toews GB. CCR2 mediates conventional dendritic cell recruitment and the formation of bronchovascular mononuclear cell infiltrates in the lungs of mice infected with cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 2008;181:610–620. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herring AC, Falkowski NR, Chen GH, McDonald RA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Transient neutralization of tumor necrosis factor alpha can produce a chronic fungal infection in an immunocompetent host: potential role of immature dendritic cells. Infect Immun. 2005;73:39–49. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.39-49.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynor TR, Herring AC, Dorf ME, Kuziel WA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Differential roles of CC chemokine ligand 2/monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and CCR2 in the development of T1 immunity. J Immunol. 2002;168:4659–4666. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterholzer JJ, Ames T, Polak T, Sonstein J, Moore BB, Chensue SW, Toews GB, Curtis JL. CCR2 and CCR6, but not endothelial selectins, mediate the accumulation of immature dendritic cells within the lungs of mice in response to particulate antigen. J Immunol. 2005;175:874–883. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortman K, Naik SH. Steady-state and inflammatory dendritic-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:19–30. doi: 10.1038/nri1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GH, McNamara DA, Hernandez Y, Huffnagle GB, Toews GB, Olszewski MA. Inheritance of immune polarization patterns is linked to resistance versus susceptibility to Cryptococcus neoformans in a mouse model. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2379–2391. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01143-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindell DM, Moore TA, McDonald RA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Generation of antifungal effector CD8+ T cells in the absence of CD4+ T cells during Cryptococcus neoformans infection. J Immunol. 2005;174:7920–7928. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindell DM, Moore TA, McDonald RA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Distinct compartmentalization of CD4+ T-cell effector function versus proliferative capacity during pulmonary Cryptococcosis. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:847–855. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmesser M, Kress Y, Novikoff P, Casadevall A. Cryptococcus neoformans is a facultative intracellular pathogen in murine pulmonary infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4225–4237. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.4225-4237.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman SK, Nichols KL, Murphy JW. Dendritic cells in the induction of protective and nonprotective anticryptococcal cell-mediated immune responses. J Immunol. 2000;165:158–167. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchroo VK, Das MP, Brown JA, Ranger AM, Zamvil SS, Sobel RA, Weiner HL, Nabavi N, Glimcher LH. B7–1 and B7–2 costimulatory molecules activate differentially the Th1/Th2 developmental pathways: application to autoimmune disease therapy. Cell. 1995;80:707–718. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milam JE, Herring-Palmer AC, Pandrangi R, McDonald RA, Huffnagle GB, Toews GB. Modulation of the pulmonary type 2 T-cell response to Cryptococcus neoformans by intratracheal delivery of a tumor necrosis factor alpha-expressing adenoviral vector. Infect Immun. 2007;75:4951–4958. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00176-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loke P, MacDonald AS, Robb A, Maizels RM, Allen JE. Alternatively activated macrophages induced by nematode infection inhibit proliferation via cell-to-cell contact. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:2669–2678. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200009)30:9<2669::AID-IMMU2669>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MS, Mentink-Kane MM, Pesce JT, Ramalingam TR, Thompson R, Wynn TA. Immunopathology of schistosomiasis. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:148–154. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukai T, Maeda Y, Tamura T, Miyamoto Y, Makino M. CD4+ T-cell activation by antigen-presenting cells infected with urease-deficient recombinant Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008;53:96–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero A, Fries BC. Phenotypic switching in Cryptococcus neoformans contributes to virulence by changing the immunological host response. Infect Immun. 2008;76:4322–4331. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00529-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. Host-pathogen interactions: basic concepts of microbial commensalism, colonization, infection, and disease. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6511–6518. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6511-6518.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. The damage-response framework of microbial pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2003;1:17–24. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmesser M, Kress Y, Casadevall A. Intracellular crystal formation as a mechanism of cytotoxicity in murine pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2723–2727. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2723-2727.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]