Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a lethal neuromuscular disease that currently has no effective therapy. Transgenic overexpression of the α7 integrin in mdx/utrn−/− mice, a model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy ameliorates the disease. We have isolated and used α7+/− muscle cells expressing β-galactosidase, driven by the endogenous α7 promoter, to identify compounds that increase α7 integrin levels. Valproic acid (VPA) was found to enhance α7 integrin levels, induce muscle hypertrophy, and inhibit apoptosis in myotubes by activating the Akt/mTOR/p70S6K pathway. This activation of the Akt pathway occurs within 1 hour of treatment and is mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase. To evaluate the potential use of VPA to treat muscular dystrophy, mdx/utrn−/− mice were injected with the drug. Treatment with VPA lowered collagen content and fibrosis, and decreased hind limb contractures. VPA-treated mice also had increased sarcolemmal integrity and decreased damage, decreased CD8-positive inflammatory cells, and higher levels of activated Akt in their muscles. Thus, VPA has important biological effects that may be applicable for the treatment of muscular dystrophy.

Muscular dystrophies are a group of diseases characterized by skeletal muscle degeneration, inflammation, necrosis, and fibrosis that lead to progressive muscle weakness. The most common form, Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), is caused by mutations in the gene encoding dystrophin,1 a member of the dystrophin- glycoprotein complex. This protein complex links laminin in the extracellular matrix to actin in the cytoskeleton. The mdx/utrn−/− mouse expresses neither dystrophin nor its homolog utrophin, and manifests severe dystrophy and a shortened life-span akin to DMD patients.2,3

The transmembrane α7β1 integrin complex also links laminin in the extracellular matrix to actin in skeletal muscle. The integrin plays structural and signaling roles that contribute to muscle development, physiology, and maintenance.4 Overexpression of the α7BX2 integrin isoform in mdx/utrn−/− mice ameliorated dystrophy and increased life-span more than threefold.5 Multiple mechanisms underlie this rescue of mdx/utrn−/− mice by the integrin and include maintaining myotendinous and neuromuscular junction structure, enhancing regeneration, increasing hypertrophy, decreasing apoptosis, and secondarily decreasing cardiomyopathy.5,6 Increased levels of integrin also protect against exercise-induced muscle damage.7 To translate these results into a potential therapy for patients, we have sought to identify molecules that enhance α7 integrin levels in skeletal muscle.

Activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway promotes skeletal muscle hypertrophy and survival.8 Activation of Akt can be initiated by phosphatidyl inositol 3-OH kinase (PI3K), which in turn activates the rapamycin-sensitive kinase mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and further downstream targets such as p70S6 kinase. This results in stimulation of gene transcription, protein synthesis, and hypertrophy.9 Expression of a constitutively active form of Akt in vitro10 or in vivo8,11 leads to muscle hypertrophy. Rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR, blocks hypertrophy when administered to rodents.8 Activated Akt also functions through multiple signaling proteins including IκB kinase, Bad, caspase-9, and forkhead transcription factors to block apoptosis and promote survival.9

Activators of the Akt pathway may also be useful in the therapy of muscular dystrophies. For example, insulin-like growth factor-1(IGF-1), an activator of the Akt/mTOR pathway, ameliorates dystrophic pathology and promotes increased muscle mass, decreased myonecrosis, and decreased fibrosis in mdx mice.12 Valproic acid (VPA) is a branched chain fatty acid that is Food and Drug Administration approved for treating epilepsy and bipolar disorders. It activates Akt in neurons and promotes their survival.13 VPA is also known to have histone deacetylase inhibitor activity.14

We report here the isolation and use of myogenic cells to identify VPA as a molecule that enhances α7 integrin expression. In addition, we show that VPA promotes hypertrophy and decreases apoptosis in myotubes in vitro by activating the Akt/mTOR/p70S6k pathway. We demonstrate that VPA activates Akt in myotubes within 1 hour of treatment. Administration of VPA to mdx/utrn−/− mice conferred multiple beneficial effects in skeletal muscle including increased sarcolemmal integrity, decreased hind-limb contractures, and decreased inflammation. Mice treated with VPA had higher levels of activated Akt in skeletal muscle, akin to results obtained in vitro in myotubes. These results suggest that VPA (or its derivatives) may be promising therapeutic molecules for the treatment of muscular dystrophy.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and Other Reagents

VPA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against activated and total Akt, mTOR, ERK, and p70S6k were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against the α7A and α7B integrin chain alternative cytoplasmic domains have been described.15 MF-20 mouse monoclonal antibody was used to detect myosin heavy chain.16 Wortmannin was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibody against collagen type VI α chain was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibody against CD8 was a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled rat anti-mouse CD8a antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Horseradish peroxidase and FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA). Cell culture reagents and fluorescein di-β-d-galactopyranoside (FDG) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Apoptotic nuclei were stained using the DeadEnd fluorometric terminal dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI).

Isolation of α7+/− Mouse Myogenic Cells

The α7+/− mice were derived as reported.17 These mice were engineered to contain the LacZ gene driven by the α7 integrin promoter. Skeletal muscles from the hind limbs (including gastrocnemius-soleus, quadriceps, and tibialis anterior) of a 3-week-old α7+/− mouse were removed under sterile conditions, finely minced in Hanks’ balanced salt solution, and incubated in 5 ml of enzyme solution I consisting of 1.5 U/ml collagenase D (0.15 U/mg powder; from Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), 2.4 U/ml dispase II (neutral protease, grade II, 0.8 U/mg powder; from Roche Diagnostics), and 2.5 mmol/L calcium chloride for 30 minutes at 37°C with trituration every 5 minutes. The supernatant was decanted into 5 ml of 20% fetal bovine serum (Biomeda Corp., Foster City, CA) in Hanks’ balanced salt solution. Enzyme solution II consisting of 0.6 mg/ml trypsin (stock solution 0.5%; Invitrogen) in Hanks’ balanced salt solution was added to the remaining muscle fragments, incubated for 30 minutes as above, and the cell suspensions were pooled. After passing the cells through a 40-μm nylon mesh, the suspension of cells was centrifuged at 350 × g for 10 minutes and the pellet was suspended in 10 ml of growth medium (see below). Preplating on noncoated tissue culture-grade plastic plates (Corning, Lowell, MA) for 30 minutes was done to separate myogenic and nonmyogenic cells. This procedure was repeated three times. Cells were then plated on 1% gelatin-coated plates.

Cell Culture and Treatment

α7+/− myogenic cells were cultured on 1% gelatin-coated plastic plates in Ham’s F-10 growth medium (20% fetal bovine serum, 0.5% chick embryo extract, 5 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor, 2 mmol/L glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin). After six passages, cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 20% fetal bovine serum, 0.5% chick embryo extract, 2 mmol/L glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Differentiation was induced by switching the medium to Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 2% horse serum and antibiotics when cells attained 90% confluence. After 48 hours of differentiation, 2 mmol/L VPA was added and supplied fresh every 24 hours. Wortmannin was used at 100 nmol/L and added fresh every 24 hours.

FDG-Based β-Galactosidase Fluorescent Assay

α7+/− muscle cells in 96-well plates were induced to differentiate for 48 hours and various concentrations of VPA were then added to six replicate wells for each concentration. Fresh VPA and differentiation medium were added every 24 hours. Control wells received only differentiation medium. After 48 hours of treatment, medium was aspirated and cells were lysed by adding 50 μl of water and freeze-thawing. Fifty μl of 2× reaction buffer (2 μmol/L FDG, 2 mmol/L MgCl2, 20 mmol/L NaH2PO4, pH 7.0, 0.2% β-mercaptoethanol) were added per well and incubated for 20 minutes, followed by addition of 2× stop solution (40 mmol/L Tris-acetate, 2 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, pH 8.0). The fluorescence in each well was quantified using an Analyst plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Quantification of Myotube Hypertrophy

After 72 hours of exposure to 2 mmol/L VPA, α7+/− myotubes on Lab-Tek chamber slides (Nalge-Nunc International, Rochester, NY) were fixed in ice-cold methanol for 5 minutes, washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 5 minutes, and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 30 minutes. The cells were stained with anti-myosin heavy chain antibody (MF-20, 1:3 in 1% BSA in PBS) and FITC-conjugated donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:200 in 1% BSA in PBS) for 1 hour each, and mounted in Vectashield with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Micrographs of 10 fields were taken for VPA-treated and control myotubes using a Leica DMRXA2 microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), AxioCam digital camera (Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY), and Openlab software (Improvision, Lexington, MA). Areas of myosin heavy chain-positive myotubes were measured using Openlab software (Improvision) and the numbers of nuclei in each myotube were counted.

Quantification of Apoptosis in Myotubes

Differentiating cultures of α7+/− cells on 1% gelatin-coated Lab-Tek eight-well chamber slides (Nalge-Nunc International) were exposed to 2 mmol/L VPA on day 2 of differentiation, and fresh VPA in differentiation medium was added every 24 hours. On day 8 of differentiation, the DeadEnd Fluorometric TUNEL assay (Promega) was used to label apoptotic nuclei, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The numbers of clusters of apoptotic nuclei in each chamber were counted.

Testing Dependence of Akt Activation on PI3K in Myotubes

To test whether Akt activation by VPA in α7+/− myotubes is dependent on PI3K, α7+/− cells were differentiated for 48 hours and treated for 72 hours with 2 mmol/L VPA with or without 100 nmol/L wortmannin. Fresh drugs were added every 24 hours. Phase-contrast micrographs of the cultures were captured at the end of 72 hours of treatment. To determine status of Akt activation in the cultures, α7+/− myotubes were treated as above and protein extracts were made at the end of 72 hours of treatment using a 2% Triton X-100 extraction buffer (see below). Immunoblotting for phospho- and total Akt were done as detailed below.

Administration of VPA to mdx/utrn−/− Mice

mdx/utrn−/− mice lack both dystrophin and utrophin,2,3 and were bred and genotyped as reported.5 Two hundred forty mg/kg body weight of VPA was injected intraperitoneally twice daily into mdx/utrn−/− mice (n = 9) starting at 3 weeks of age, for a period of 5 weeks. Control mice were injected with saline (n = 9). Body weights were determined daily.

Contracture Assay

On the 35th day of treatment, mdx/utrn−/− mice injected with saline (n = 9) or VPA (n = 9) were tested for contractures in their hind limbs as follows: mice were placed on a flat table and were lifted by their tails so that their forelimbs touched the table surface and their hindquarters were in air. The positions of the hindlimbs were photographed. Normally, mice in this position extend their hindlimbs. The presence of contractures in dystrophic mice prevents full extension. The number of mice in the VPA-treated and control groups that failed to extend their hindlimbs were noted.

Western Blot Analysis

Lysates of differentiating cells on 60-mm dishes were prepared as follows: the cells were washed twice with PBS and 200 μl of Triton X-100 lysis buffer [2% Triton X-100, 20 mmol/L Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1 mmol/L EGTA, 2.5 mmol/L NaPPi, 1 mmol/L β-glycerophosphate, 1 mmol/L sodium vanadate, 1:200 protease inhibitor cocktail (EMD Chemicals, San Diego, CA) and 1 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride] were added. The cells were scraped and transferred into Eppendorf tubes, the cell suspensions were triturated and centrifuged at 8000 × g at 4°C for 10 minutes, and the supernatants were collected. Lysates from mouse skeletal muscle were prepared as follows: the quadriceps muscles were dissected out, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and pulverized using a mortar and pestle. The powdered muscles were collected in Eppendorf tubes, 500 μl of Triton X-100 lysis buffer were added, rotated at 4°C for 30 minutes, centrifuged at 8000 × g for 10 minutes, and the supernatants were collected. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay. Sodium dodecyl sulfate extracts of muscle were made by boiling powdered muscle in extraction buffer (100 mmol/L Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 10 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and 10% glycerol) for 10 minutes, vortexing vigorously, and centrifuging at 8000 × g for 10 minutes. The supernatants were collected and protein concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically at OD260 and OD280. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed using 50 μg of protein for each sample and separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. For Western blotting using antibodies against signaling proteins, membranes were blocked in 5% BSA in TBST for 2 hours at room temperature. For all other blots, incubations were done in 5% milk in TBST overnight at 4°C. The membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted 1:1000 in 1% BSA in TBST. After washing in 1% BSA in TBST, blots were incubated for 1 hour in horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies diluted 1:5000 in 1% BSA in TBST. Blots were processed using the ECL kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) and bands were visualized with Kodak Biomax MR film (Kodak, Rochester, NY). ImageQuant analysis software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) was used to quantify band intensity.

Quantification of Evan’s Blue Dye Uptake

On the 35th day of injection of VPA, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 100 mg/kg body weight of Evan’s blue dye. After 24 hours, the quadriceps muscles were collected, frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane, and stored at −80°C. Eight-μm cryosections of quadriceps were fixed in ice-cold methanol for 1 minute and washed in PBS three times for 5 minutes each. To delineate muscle fibers, the sections were incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature in FITC-conjugated wheat-germ agglutinin (Invitrogen) diluted 1:500 in PBS. The sections were washed three times in PBS, 5 minutes each time, and the percentage of Evan’s blue dye-positive fibers in three sections taken 40 μm apart were counted (∼5000 fibers total) for each mouse.

Quantification of CD8-Positive Cells in Muscle

Eight-μm-thick cryosections of the quadriceps muscles of saline- and VPA-injected mice were made. Cytotoxic T cells were detected with a FITC-labeled rat anti-mouse CD8a antibody (BD Pharmingen) as follows: the sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 minutes, washed in PBS three times for 5 minutes each, blocked with 5% BSA/PBS for 1 hour, anti-CD8 antibody added at 1:1000 dilution for 1 hour, and washed in 1% BSA/PBS three times for 5 minutes each. The sections were mounted in Vectashield containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories). The number of CD8-positive cells and the total number of nuclei in the same field were counted in 10 random fields for each mouse. The ratio of the number of CD8-positive cells to the total number of nuclei were calculated, averaged, and plotted for the saline- and VPA-treated groups.

Masson’s Trichrome Staining

A Masson’s trichrome staining kit (American MasterTech Scientific Inc., Lodi, CA) was used to stain 8-μm muscle cryosections, as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Results

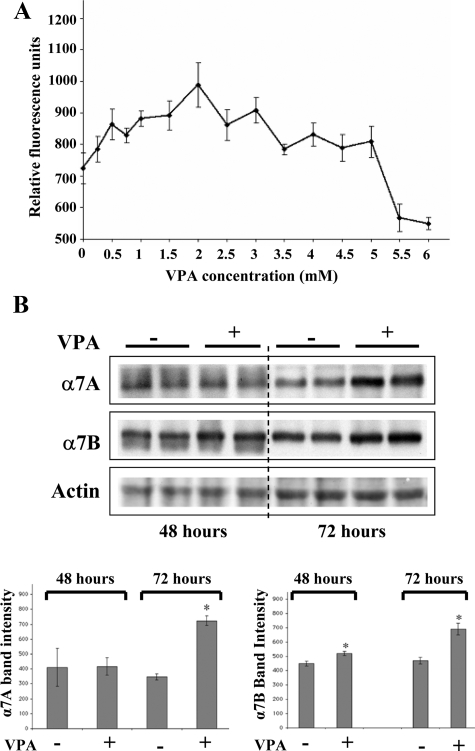

Muscle Cells Treated with VPA Have Enhanced Levels of α7 Integrin

α7+/− myotubes were treated with various concentrations of VPA for 48 hours starting at day 2 of differentiation. β-Galactosidase, the reporter for α7 expression in these cells was quantified using the FDG assay. The effect of VPA, reported by β-galactosidase activity, was concentration-dependent, with the highest level being 1.4-fold, at 2 mmol/L VPA (Figure 1A). Western blotting confirmed increases in α7 protein. The α7A and α7B integrin isoforms were increased 2-fold and 1.5-fold, respectively, in myotubes treated with 2 mmol/L VPA for 72 hours (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

VPA increases α7 integrin levels in α7+/− myotubes. A: FDG-based β-galactosidase assay was done after exposing 2-day-old α7+/− myotubes to various concentrations of VPA for 24 hours. Data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples. B: Top: Western blotting of α7 integrin in extracts of α7+/− myotubes exposed for 48 or 72 hours to 2 mmol/L VPA in duplicate plates. Bottom: Quantification of α7 band intensities. Data represent mean ± SD of duplicate samples. *P < 0.05.

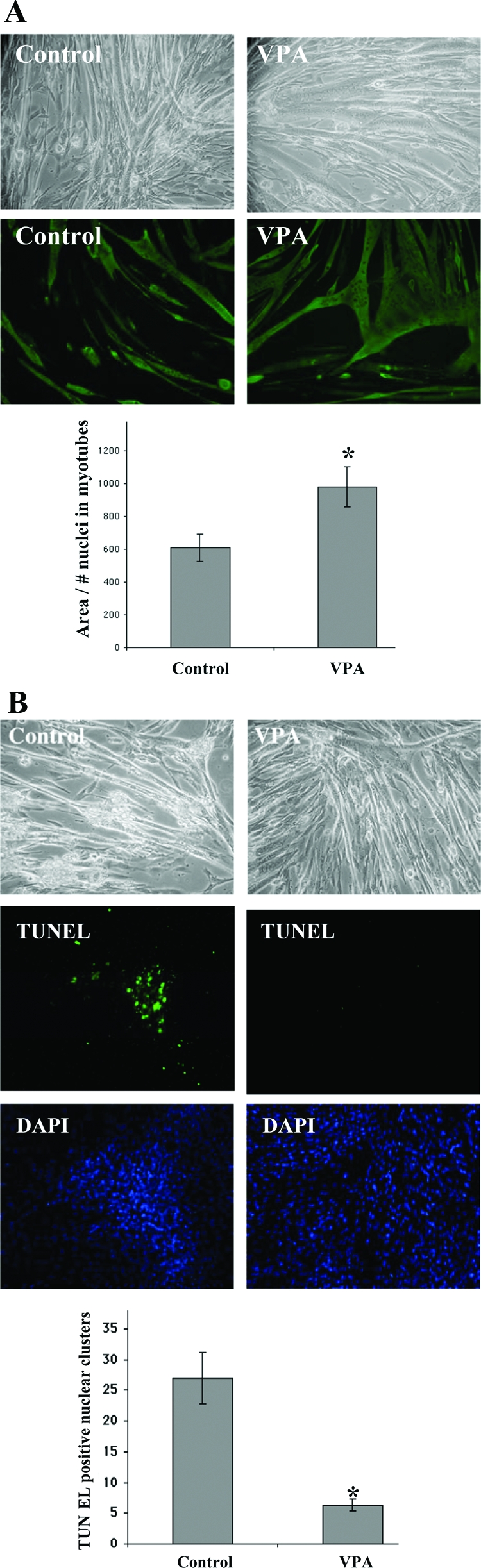

VPA Promotes Hypertrophy and Inhibits Apoptosis in α7+/− Myotubes

α7+/− myotubes were observed every 24 hours after treatment with 2 mmol/L VPA. As shown in Figure 2A, myotubes in VPA-treated cultures were larger compared with controls. To quantify this effect, myotubes were stained with anti-myosin heavy chain antibody, and their areas were determined. To score for hypertrophy, the number of nuclei in the myotubes were counted and the ratios of myotube area to number of nuclei within the myotube were determined. The areas per nucleus of the VPA-treated myotubes were 1.6-fold greater than control indicating that VPA promotes hypertrophy in myotubes (Figure 2A). The VPA-treated cultures also had greater numbers of nuclei per myotube compared with untreated controls, indicating that increased fusion of myoblasts into myotubes also contributed toward forming the larger myotubes.

Figure 2.

VPA promotes hypertrophy and inhibits apoptosis in α7+/− myotubes. Two mmol/L VPA was added to day 2 α7+/− differentiating cultures. A: Top: Phase-contrast micrographs of α7+/− myotubes exposed to VPA for 72 hours compared with untreated control cells. Bottom: Myotubes exposed to VPA for 72 hours and stained using anti-myosin heavy chain antibody. The graph shows the ratios of myotube area to the number of nuclei within myotubes in VPA-treated and control cultures. Data represent mean ± SD of the ratios in 10 random fields. *P < 0.05. B: Top: Phase-contrast micrographs of α7+/− myotubes treated with VPA for 6 days (starting on day 2 of differentiation) compared with untreated controls. Bottom: α7+/− myotubes in eight-well chamber slides were exposed to either 2 mmol/L VPA (four chambers) or no treatment (four chambers) for 6 days. TUNEL assays identify FITC-labeled apoptotic nuclei. DAPI staining shows all nuclei in the same fields. The total number of TUNEL-positive nuclear clusters in four chambers each for VPA-treated and control cultures was counted. Data represent mean ± SD of quadruplicate values. *P < 0.05.

Myotubes kept for prolonged periods of time in culture often become vacuolated, undergo apoptosis, and detach. After day 8, α7+/− myotubes in control cultures exhibited vacuoles and some detachment. In contrast, VPA-treated cultures appeared relatively normal (Figure 2B). A TUNEL assay was used to quantify the proportion of apoptotic nuclei in VPA-treated and control cultures. Two mmol/L VPA was added on day 2 of differentiation. Fresh medium and VPA were added every 24 hours. On day 6 of treatment, TUNEL assays were done. VPA-treated cultures had greater than fivefold fewer apoptotic nuclei compared with control cells (Figure 2B), indicating that treatment with VPA promotes myotube survival.

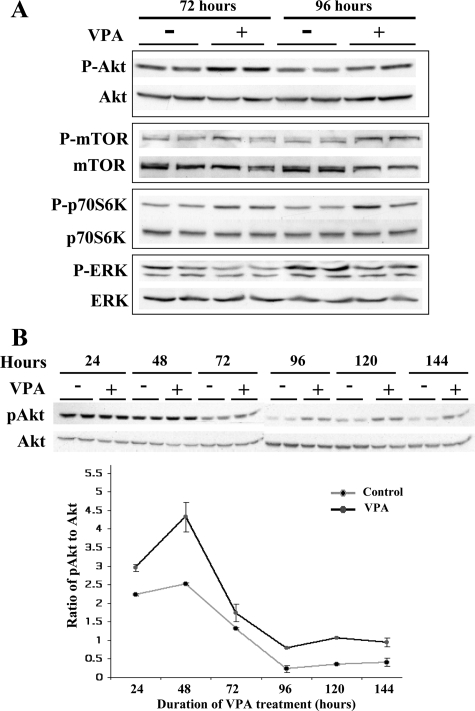

VPA Activates the Akt/mTOR/p70S6K Pathway and Inhibits the ERK Pathway in α7+/− Myotubes

To determine the mechanism by which VPA promotes hypertrophy and survival, the Akt/mTOR/p70S6K pathway was investigated. Myotubes treated with VPA for 48 or 72 hours had higher levels of activated Akt, mTOR, and p70S6K (Figure 3A). In myotubes, the ERK and Akt pathways are antagonistic to each other.18 As shown in Figure 3A, VPA-treated myotubes also had significantly lower levels of activated ERK.

Figure 3.

VPA activates the Akt/mTOR/p70S6K pathway in α7+/− myotubes. A: Two mmol/L VPA was added to duplicate cultures of day 2 α7+/− myotubes for 72 or 96 hours, followed by Western blotting using antibodies against the signaling proteins. Higher levels of activated Akt, mTOR, and p70S6K and lower levels of activated ERK were detected in the VPA-treated myotubes. B: α7+/− myotubes in duplicate plates were treated with 2 mmol/L VPA and protein was extracted every 24 hours for up to 144 hours. Western blotting was done to quantify phospho and total Akt. The ratio of band intensities of phospho to total Akt every 24 hours shows sustained activation of Akt in the VPA-treated cells.

To determine whether VPA induced a transient or sustained activation of Akt, 2 mmol/L VPA was added daily to α7+/− myotubes, protein extracts were made every 24 hours up to 144 hours, and Western blotting was performed to determine the levels of activated and total Akt. The ratios of band intensities of activated to total Akt were calculated (Figure 3B). VPA-treated myotubes exhibited higher levels of activated Akt at all time points. Although total Akt levels decreased with increasing days of differentiation in both control and VPA-treated cultures, the higher proportion of phosphorylated Akt was sustained in the treated α7+/− myotubes.

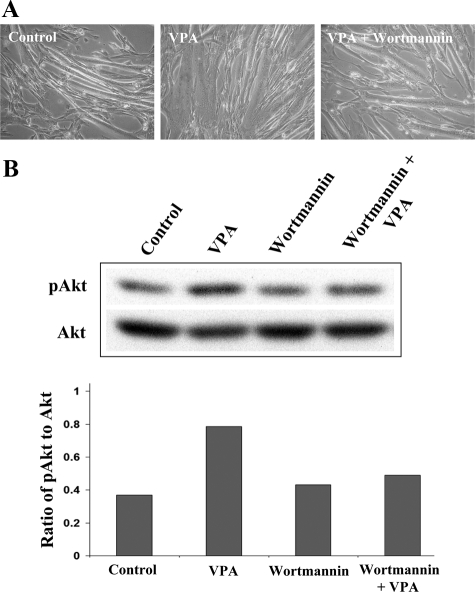

Akt Activation by VPA Is Dependent on PI3K

Because VPA has histone deacetylase inhibitor activity, kinases expressed or activated as a result of gene modulation may activate Akt independently of PI3K. Alternatively, VPA may activate Akt through the classical PI3K pathway. To differentiate between these possibilities, 2 mmol/L VPA was added on day 2 of differentiation either with or without 100 nmol/L wortmannin, a potent inhibitor of PI3K. Fresh VPA and wortmannin were added every 24 hours thereafter. Microscopic observations revealed that wortmannin attenuated the myotube hypertrophy promoted by VPA (Figure 4A). Western blots of extracts made 72 hours after exposure to the drugs demonstrate that wortmannin attenuated the activation of Akt by VPA, confirming that VPA activates Akt through PI3K (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Akt activation by VPA is dependent on PI3K. A: α7+/− myotubes were treated for 72 hours with 2 mmol/L VPA with or without 100 nmol/L wortmannin. Fresh drugs were added every 24 hours. Phase-contrast micrographs show that the hypertrophic effect of VPA on myotubes is attenuated by wortmannin, indicating that VPA depends on PI3K for this effect. B: α7+/− myotubes treated as above were extracted and immunoblotted for phospho and total Akt. Ratios of phospho to total Akt band intensities were plotted. The Akt-activating effect of VPA was attenuated by wortmannin.

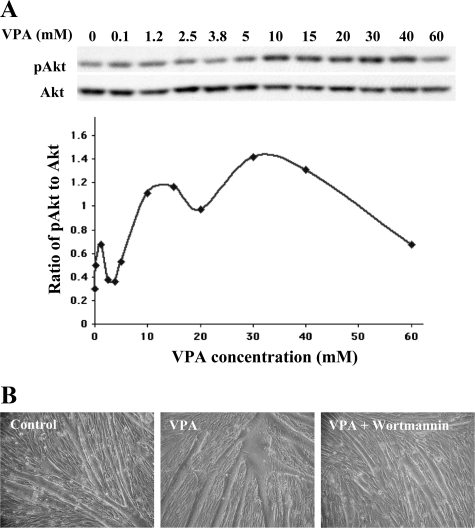

A 1-Hour Exposure to VPA Activates Akt and Promotes Myotube Hypertrophy

The data above showed that myotubes treated with VPA for 24 hours or longer had higher levels of PI3K-mediated Akt activation, leading to hypertrophy and decreased apoptosis. To determine whether this Akt activation and its resulting downstream effects are triggered by VPA at a shorter time after exposure, 2-day old differentiating cultures were treated with various concentrations of VPA for 1 hour, extracted, and immunoblotted for total and phosphorylated Akt. Treatment of α7+/− myotubes with VPA activated Akt within 1 hour. Activation of Akt exhibited a dose-dependent response to VPA, with maximal activation at 30 mmol/L (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

VPA activates Akt within 1 hour in a dose-dependent manner and this brief exposure promotes hypertrophy in α7+/− myotubes. A: α7+/− myotubes were exposed to various concentrations of VPA for 1 hour, followed by extraction and Western blotting for Akt. Band intensities from the blots were quantified and the ratios of activated to total Akt were plotted. VPA activates Akt in a dose-dependent manner, with highest activation seen at 30 mmol/L VPA. B: α7+/− myotubes were exposed to 30 mmol/L VPA with or without 100 nmol/L wortmannin for 1 hour, washed, and fresh medium was added. Microscopic observations 72 hours later show hypertrophy in myotubes exposed to VPA. This effect was attenuated by wortmannin, confirming the ability of VPA to activate Akt within 1 hour is dependent on PI3 kinase.

To determine whether Akt activation induced by the 1-hour exposure to VPA is mediated through PI3K and is sufficient to promote myotube hypertrophy, 30 mmol/L VPA, with or without 100 nmol/L wortmannin was added on day 2 of differentiation for 1 hour, followed by removal of medium, washing twice with PBS, and adding fresh medium with no VPA or wortmannin. Microscopic observations 72 hours after this protocol revealed that myotubes exposed to VPA for 1 hour were larger compared with controls (Figure 5B). Thus a 1-hour exposure of cells to VPA is sufficient to trigger changes that lead to hypertrophy. The presence of wortmannin inhibited this effect, confirming that the ability of VPA to activate Akt within 1 hour is dependent on PI3K (Figure 5B). These results indicate that Akt activation and the resulting myotube hypertrophy are triggered by VPA at time periods at least as short as 1 hour of treatment.

VPA Ameliorates Hind-Limb Contractures in mdx/utrn−/− Mice and Inhibits Fibrosis

Because VPA promoted beneficial effects in muscle cells in culture, we determined if VPA could also have beneficial effects in dystrophic muscle. VPA or saline were administered intraperitoneally into mdx/utrn−/− mice (see Materials and Methods). The mdx/utrn−/− mice exhibit severe muscular dystrophy and reduced lifespan.2,3,5

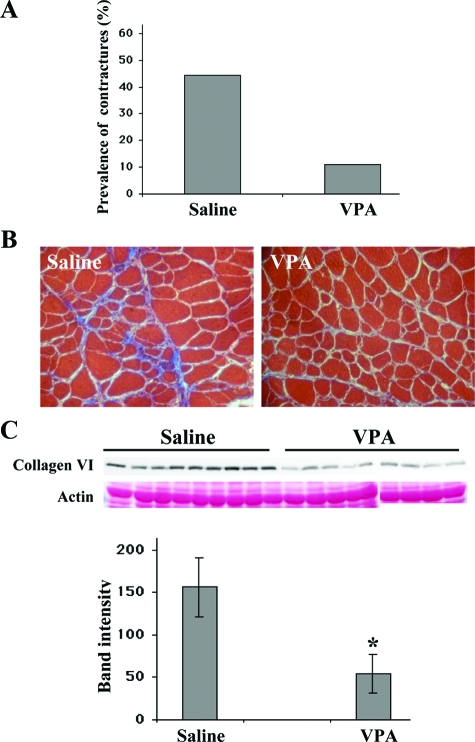

The number of mice with hind-limb contractures in the group injected with VPA was approximately fourfold lower compared with saline-injected mice (Figure 6A). To determine whether treatment with VPA decreased fibrosis, cryosections of quadriceps were stained with Masson’s trichrome stain, which stains collagen blue. mdx/utrn−/− mice treated with VPA had a lower intensity of collagen staining compared with controls, indicating that VPA treatment led to decreased collagen content in these muscles (Figure 6B). Type VI collagen is elevated twofold to threefold in DMD patients compared with normal.19 Western blotting revealed that mdx/utrn−/− mice treated with VPA had approximately threefold lower expression of type VI collagen in muscle than control mice (Figure 6C). Thus treatment with VPA decreased fibrosis in the mdx/utrn−/− dystrophic mice.

Figure 6.

VPA inhibits muscle fibrosis in dystrophic muscle and ameliorates hind limb contractures in mdx/utrn−/− mice. A: On the 35th day of treatment, mdx/utrn−/− mice injected with saline (n = 9) or VPA (n = 9) were tested for contractures in their hind limbs by lifting of their tails. The presence of contractures prevents full extension of the hind limbs. The graph shows the proportion of mice with contractures in the saline-injected group (four of nine, 44.4%) was fourfold higher than the VPA-injected group (one of nine, 11.1%). B: Cryosections of quadriceps stained with Masson’s trichrome. Collagen content is higher in muscle from saline-injected mice (as seen by the higher intensity of blue), compared with VPA-injected mice. C: Sodium dodecyl sulfate extracts of quadriceps from saline (n = 9)- and VPA (n = 9)-injected mice were subjected to Western blotting for collagen type VI. Quantification of band intensities show greater than threefold more collagen type VI in the saline-injected mice compared with animals injected with VPA. Data represent mean ± SD. *P < 0.05.

VPA Increases Myofiber Integrity and Decreases Inflammation in Dystrophic Muscle

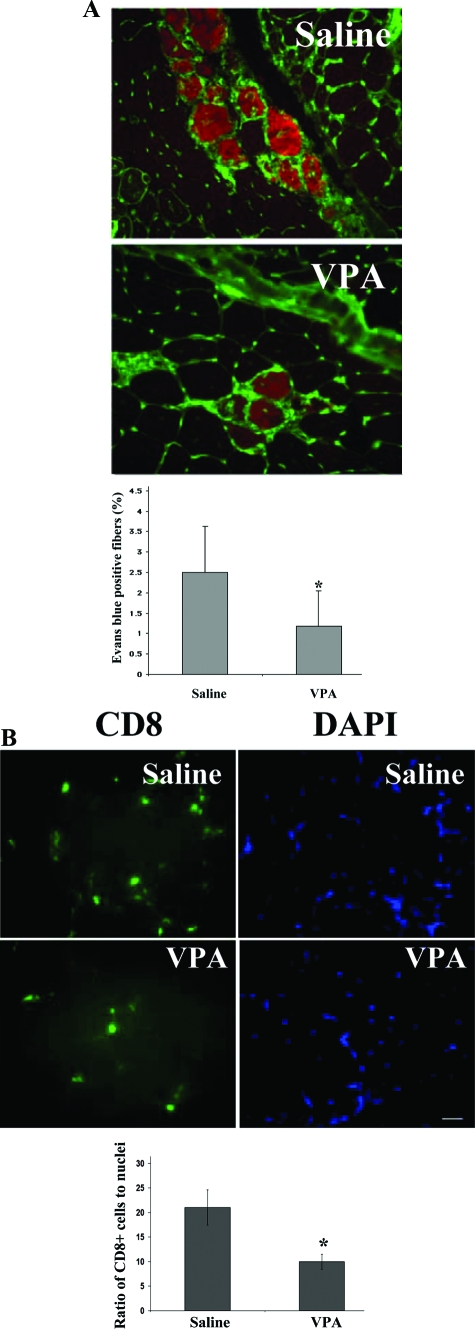

Cryosections from the quadriceps muscles of mice treated with VPA or saline were evaluated for Evans blue dye-positive fibers. The total number of fibers in two sections taken 40 μm apart from each mouse was counted (∼5000 fibers for each mouse) and the percentage of Evans blue-positive fibers were noted. VPA-injected mdx/utrn−/− mice had approximately twofold fewer damaged fibers than mice injected with saline (Figure 7A). To determine whether VPA reduced inflammation in dystrophic muscle, cryosections from quadriceps of VPA-treated and control mdx/utrn−/− mice were stained using anti-CD8 antibody. Our results show that VPA treatment decreased the CD8-positive cytotoxic T-cell content by ∼2.1-fold in dystrophic muscle (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

VPA increases myofiber integrity and decreases inflammation in dystrophic muscle. A: Cryosections of quadriceps from saline (n = 9)- and VPA (n = 9)-injected mdx/utrn−/− mice that also had been injected with Evans blue dye (50 mg/kg). FITC-wheat germ agglutinin was used to delineate myofibers. The red fluorescence shows Evans blue dye-positive fibers. The percentage of Evan’s blue dye-positive fibers in three sections, 40 μm apart, were counted (∼5000 fibers total) for each mouse. Quantification shows an ∼2.5-fold decrease in proportion of Evans blue-positive fibers in VPA-injected mice. Data represent mean ± SD. *P < 0.05. B: Cryosections of quadriceps from saline- and VPA-injected mice were stained for CD8-positive cytotoxic T cells using a FITC-labeled anti-CD8a antibody. The sections were co-stained with DAPI to delineate nuclei. The number of CD8-positive cells and the total number of nuclei in the same field were counted in 10 random fields for each mouse. The ratio of the number of CD8-positive cells to the total number of nuclei were calculated, averaged, and plotted for the saline- and VPA-treated groups. Quantification shows a 2.1-fold decrease in number of CD8-positive cells in VPA-treated mice. Data represent mean ± SD. *P < 0.05.

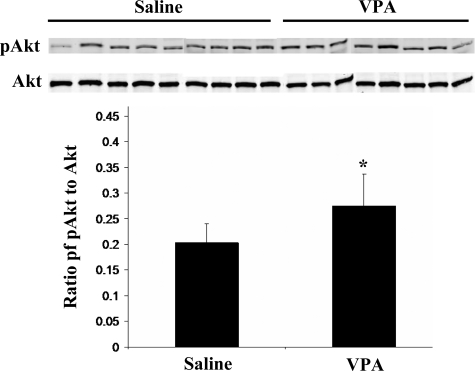

VPA-Treated Mice Have Higher Activated Akt in Skeletal Muscle

To understand the mechanism by which VPA ameliorated dystrophy in the mdx/utrn−/− mice, Western blotting was done for activated and total Akt in extracts prepared from quadriceps muscles of saline- and VPA-treated mice. Significantly higher levels of activated Akt were found in the muscles of VPA-treated mice (Figure 8). However, Western blotting and quantification of α7 integrin in the muscle extracts did not show changes between the saline- and VPA-injected mice (data not shown). In summary, these data demonstrate that VPA activates the Akt pathway in myotubes in vitro and in skeletal muscle of severely dystrophic mdx/utrn−/− mice in vivo where it ameliorates dystrophy.

Figure 8.

VPA-treated mice have higher proportions of activated Akt in skeletal muscle. Extracts of quadriceps from saline- and VPA-injected mdx/utrn−/− mice were subjected to Western blotting for activated and total Akt. Quantification of band intensities and ratios of activated to total Akt show higher levels of activated Akt in the VPA-injected mice. Data represent mean ± SD. *P < 0.05.

Discussion

Although it is approximately 2 decades since mutations in the gene encoding dystrophin were discovered to be the underlying cause of DMD, there is still no cure or effective therapy for this devastating neuromuscular disorder. Transgenic overexpression of α7 integrin can partially rescue mdx/utrn−/− mice against dystrophy.5,6 Overexpression of α7 integrin in muscle does not disrupt global gene expression profiles.20 We have therefore sought to identify molecules that can enhance α7 integrin levels in skeletal muscle using α7+/− myotubes.

VPA, a drug that is currently Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of epilepsy and bipolar disorders, increased α7 integrin levels in myotubes, maximally at a dose of 2 mmol/L. Microscopic observations revealed that the VPA-treated myotubes were larger compared with controls. Myoblasts pretreated with other histone deacetylase inhibitors have higher rates of fusion into preformed myotubes and thus also produce larger myotubes.21 However earlier studies show that histone deacetylase inhibitors inhibit myoblast differentiation in vitro.22 Our results demonstrate that VPA-treated cultures had increased ratios of myotube area to number of nuclei, compared with untreated cultures. The number of nuclei per myotube was also increased in VPA-treated cultures, indicating that both hypertrophy and increased fusion of myoblasts into myotubes contributed to the larger myotubes seen on exposure to VPA.

VPA-treated myotubes also survived longer in culture compared with untreated controls. Neurons treated with VPA likewise survive for longer periods of time in vitro than untreated controls.13 To test whether VPA promoted survival by inhibiting apoptosis, a TUNEL assay was performed after 6 days of VPA treatment. VPA-treated cultures had fivefold fewer apoptotic nuclei, indicating VPA promoted myotube survival.

The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway was investigated to understand the mechanism by which VPA promotes hypertrophy and inhibits apoptosis. Activation of this pathway promotes hypertrophy and inhibits apoptosis in skeletal muscle.9 IGF-1 activates this pathway and promotes these effects in muscle and use of IGF-1 has shown encouraging results in treating muscular dystrophy.12 Immunoblotting with antibodies against activated or total Akt, mTOR, and p70S6k showed that VPA activated this pathway in myotubes, thus explaining its hypertrophic and survival effects on myotubes.

To determine whether activation of Akt in myotubes is transient or sustained in the presence of VPA, Akt levels were determined every 24 hours starting on day 2 of differentiation. Higher levels of activated Akt were detected in VPA-treated cultures compared with controls at all time points tested, with the proportion of activated Akt increasing with time of exposure to VPA. Beyond 96 hours, there were twofold to threefold higher levels of Akt in VPA-treated cultures. This may explain the increased survival of myotubes in VPA-treated cultures kept for prolonged periods of time.

Wortmannin, a specific inhibitor of PI3K was used to distinguish whether VPA activated Akt through the classical PI3K pathway or through an alternate pathway. Wortmannin attenuated Akt activation by VPA, showing Akt activation by VPA is dependent on PI3K. Moreover, wortmannin inhibited the hypertrophy promoted by VPA, confirming that PI3K-mediated Akt activation by VPA is necessary to induce hypertrophy in myotubes.

Our results show that myotubes treated with VPA for 24 hours or longer had higher levels of PI3K-mediated Akt activation, leading to hypertrophy and decreased apoptosis. This activation of Akt and its resulting downstream effects were triggered by treatment with VPA for as short as 1 hour and with a dose-dependent maximal Akt activation at 30 mmol/L. This is interesting, since to date, VPA has not been shown to activate the Akt pathway in muscle. The mechanism by which VPA activates the PI3K/Akt pathway is currently not known but it may be mediated through direct effects of VPA on PI3K, PDK, or both.

Administration of VPA to severely dystrophic mdx/utrn−/− mice led to several beneficial changes in muscle including decreased incidence of hind-limb contractures. Masson’s trichrome staining also showed decreased collagen in the muscle of VPA-treated mice. In DMD patients type VI collagen is increased approximately twofold to threefold above normal and extensive fibrosis contributes to the dystrophic pathology and severely limits the mobility.19,23,24 Western blotting of protein extracted from the quadriceps of mdx/utrn−/− mice treated with VPA showed an approximate threefold decrease in levels of this collagen. Mice treated with VPA also had greater myofiber integrity, as shown by decreased Evans blue dye uptake. Furthermore, treatment with VPA decreased the number of CD8-positive inflammatory cells ∼2.1-fold. These results indicate that VPA promotes increased myofiber integrity that leads to less damage and thus less inflammation, and this eventually results in decreased fibrosis.

To understand the mechanism by which VPA ameliorated dystrophic pathology in mdx/utrn−/− mice, Western blotting was done to quantify activated and total Akt in the quadriceps muscles of VPA- and saline-treated mice. The VPA-treated mice had higher activated Akt compared with the saline controls. Studies have shown that Akt activation mediated by IGF-1 plays a central role in inhibiting apoptosis and promoting growth in muscle.25,26 Elevated levels of activated Akt are seen in mdx mice that overexpress IGF-1 in muscle, and these mice have decreased fibrosis and myonecrosis.12 Our results show that VPA-mediated activation of Akt also promotes muscle integrity.

Although transgenic α7mdx/utrn−/− mice that overexpress the integrin, and α7+/− myotubes treated in vitro with VPA, both have increased levels of α7 chain and increased activated Akt (D.J. Burkin, M.D. Boppart, and S.J. Kaufman, manuscript in preparation), there was no change in α7 levels in the muscles of mdx/utrn−/− mice injected with VPA. Thus VPA and α7 integrin appear to activate the Akt pathway differently. VPA-mediated activation of Akt appears to be independent of the integrin and the excess integrin present in the α7mdx/utrn−/− mice was sufficient to mediate activation of Akt.5,6 In both cases, activation of Akt promoted muscle integrity. The dose and duration of injection of VPA in the mdx/utrn−/− mice may not have been optimal to increase α7 chain levels. The half-life of VPA in mice is ∼45 minutes,27,28 thus serum levels of VPA may not have been sustained long enough to stimulate α7 integrin expression in the mdx/utrn−/− mice. A different method of VPA administration such as implantable subcutaneous capsules or pumps might be more effective at achieving sustained serum levels of the drug and enhanced α7β1 integrin levels would likely promote an even greater degree of amelioration of muscle pathology in mice.5,6 Additionally, it has recently been shown that α7 integrin promotes activation and proliferation of satellite cells for regeneration in muscle.6,29 In humans, the half life of VPA is ∼14 hours.30 Thus, therapeutic levels of the drug may be achieved and sustained in DMD patients at lower doses.

Our results demonstrate for the first time that VPA is an activator of Akt in muscle, both in vitro and in vivo. Because the drug is effective in decreasing fibrosis, increasing myofiber integrity, and decreasing inflammation, VPA and its derivatives may be promising candidates for the treatment of muscular dystrophy. Additional preclinical studies are needed to optimize dosage and direct measurements of muscle contractility should prove informative. Thereafter, it should take a relatively short period to further evaluate VPA as a therapy for muscular dystrophy since the Food and Drug Administration currently approves VPA for treating neurological ailments.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Paul Hergenrother, University of Illinois, for the use of his fluorescence plate reader; Dr. Joshua Sanes, Harvard University, for providing mice for breeding the mdx/utrn−/− animals; Dr. Jie Chen, University of Illinois, for her thoughtful discussions; and Melissa Hentges, Jachinta Rooney, and Jennifer Welser for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Stephen J. Kaufman, Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, University of Illinois, B107 CLSL, 601 S. Goodwin Ave., Urbana, IL 61801. E-mail: stephenk@illinois.edu.

Supported by the Muscular Dystrophy Association (to S.J.K.) and the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grant R01AR053697-01 to D.J.B., National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant R21NS058429-01 to D.J.B., and National Institutes of Health grant AG14632 to S.J.K.).

References

- Hoffman EP, Brown RH, Jr, Kunkel LM. Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell. 1987;51:919–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady RM, Teng H, Nichol MC, Cunningham JC, Wilkinson RS, Sanes JR. Skeletal and cardiac myopathies in mice lacking utrophin and dystrophin: a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1997;90:729–738. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80533-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deconinck AE, Rafael JA, Skinner JA, Brown SC, Potter AC, Metzinger L, Watt DJ, Dickson JG, Tinsley JM, Davies KE. Utrophin-dystrophin-deficient mice as a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1997;90:717–727. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80532-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkin DJ, Kaufman SJ. The alpha7beta1 integrin in muscle development and disease. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;296:183–190. doi: 10.1007/s004410051279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkin DJ, Wallace GQ, Nicol KJ, Kaufman DJ, Kaufman SJ. Enhanced expression of the alpha 7 beta 1 integrin reduces muscular dystrophy and restores viability in dystrophic mice. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:1207–1218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.6.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkin DJ, Wallace GQ, Milner DJ, Chaney EJ, Mulligan JA, Kaufman SJ. Transgenic expression of alpha7beta1 integrin maintains muscle integrity, increases regenerative capacity, promotes hypertrophy, and reduces cardiomyopathy in dystrophic mice. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62249-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boppart MD, Burkin DJ, Kaufman SJ. Alpha7beta1-integrin regulates mechano transduction and prevents skeletal muscle injury. Am J Physiol. 2006;290:C1660–C1665. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00317.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodine SC, Stitt TN, Gonzalez M, Kline WO, Stover GL, Bauerlein R, Zlotchenko E, Scrimgeour A, Lawrence JC, Glass DJ, Yancopoulos GD. Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;11:1014–1019. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Signaling pathways in skeletal muscle remodeling. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:19–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi A, Kureishi Y, Yang J, Luo Z, Guo K, Mukhopadhyay D, Ivashchenko Y, Branellec D, Walsh K. Myogenic Akt signaling regulates blood vessel recruitment during myofiber growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4803–4814. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4803-4814.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallafacchina G, Calabria E, Serrano AL, Kalhovde JM, Schiaffino S. A protein kinase B-dependent and rapamycin-sensitive pathway controls skeletal muscle growth but not fiber type specification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9213–9218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142166599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton ER, Morris L, Musaro A, Rosenthal N, Sweeney HL. Muscle-specific expression of insulin-like growth factor I counters muscle decline in mdx mice. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:137–148. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan T, Li X, Xie W, Jankovic J, Le W. Valproic acid-mediated Hsp70 induction and anti-apoptotic neuroprotection in SH-SY5Y cells. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:6716–6720. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göttlicher M, Minucci S, Zhu P, Krämer OH, Schimpf A, Giavara S, Sleeman JP, Lo Coco F, Nervi C, Pelicci PG, Heinzel T. Valproic acid defines a novel class of HDAC inhibitors inducing differentiation of transformed cells. EMBO J. 2001;20:6969–6978. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.6969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song WK, Wang W, Sato H, Bielser DA, Kaufman SJ. Expression of alpha 7 integrin cytoplasmic domains during skeletal muscle development: alternate forms, conformational change, and homologies with serine/threonine kinases and tyrosine phosphatases. J Cell Sci. 1993;106:1139–1152. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.4.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader D, Masaki T, Fischman DA. Immunochemical analysis of myosin heavy chain during avian myogenesis in vivo and in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1982;95:763–770. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.3.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flintoff-Dye NL, Welser J, Rooney J, Scowen P, Tamowski S, Hatton W, Burkin DJ. Role for the alpha7beta1 integrin in vascular development and integrity. Dev Dyn. 2005;234:11–21. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommel C, Clarke BA, Zimmermann S, Nuñez L, Rossman R, Reid K, Moelling K, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ. Differentiation stage-specific inhibition of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway by Akt. Science. 1999;286:1738–1741. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslett JN, Sanoudou D, Kho AT, Bennett RR, Greenberg SA, Kohane IS, Beggs AH, Kunkel LM. Gene expression comparison of biopsies from Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and normal skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15000–15005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192571199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Burkin DJ, Kaufman SJ. Increasing alpha 7 beta 1-integrin promotes muscle cell proliferation, adhesion, and resistance to apoptosis without changing gene expression. Am J Physiol. 2008;294:C627–C640. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00329.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iezzi S, Di Padova M, Serra C, Caretti G, Simone C, Maklan E, Minetti G, Zhao P, Hoffman EP, Puri PL, Sartorelli V. Deacetylase inhibitors increase muscle cell size by promoting myoblast recruitment and fusion through induction of follistatin. Dev Cell. 2004;6:673–684. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iezzi S, Cossu G, Nervi C, Sartorelli V, Puri PL. Stage-specific modulation of skeletal myogenesis by inhibitors of nuclear deacetylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7757–7762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112218599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louboutin JP, Fichter-Gagnepain V, Thaon E, Fardeau M. Morphometric analysis of mdx diaphragm muscle fibres. Comparison with hindlimb muscles. Neuromuscul Disord. 1993;3:463–469. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(93)90098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison J, Lu QL, Pastoret C, Partridge T, Bou-Gharios G. T-cell-dependent fibrosis in the mdx dystrophic mouse. Lab Invest. 2000;80:881–891. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessi DR, Cohen P. Mechanism of activation and function of protein kinase B. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor MA, Rotwein P. Insulin-like growth factor-mediated muscle cell survival: central roles for Akt and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8983–8995. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.8983-8995.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löscher W. Serum protein binding and pharmacokinetics of valproate in man, dog, rat and mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1978;204:255–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löscher W, Nau H. Valproic acid: metabolite concentrations in plasma and brain, anticonvulsant activity, and effects on GABA metabolism during subacute treatment in mice. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1982;257:20–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney JE, Gurpur PB, Yablonka-Reuveni Z, Burkin DJ. Laminin-111 restores regenerative capacity in a mouse model for α7-integrin congenital myopathy. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:256–264. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman AG, Rall TW, Nies AS, Taylor P. New York: Pergamon Press,; Goodman and Gilman’sThe Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 1990:pp 450–453. [Google Scholar]