Abstract

Management of small plant populations requires an understanding of their reproductive ecology, particularly in terms of sensitivity to Allee effects. To address this issue, we explored how components of pollen transfer and pollination success of individual plants varied among 36 populations of the self-compatible moth-pollinated orchid Satyrium longicauda in South Africa. Mean fruit set, seed production, proportion of flowers with pollen deposited or removed and proportion of removed pollen that reached stigmas (approx. 8% in this species) were not significantly related to population size (range: 1–450 flowering individuals), density or isolation. Plants in small populations did, however, have significantly higher levels of pollinator-mediated self-pollination (determined using colour-labelled pollen) than those in larger populations. Our results suggest that small populations of this orchid species are resilient to Allee effects in terms of overall pollination success, although the higher levels of pollinator-mediated self-pollination in small populations may lead to inbreeding depression and long-term erosion of genetic diversity.

Keywords: Allee effects, pollen transfer efficiency, pollination, population ecology, Satyrium, self-pollination

1. Introduction

Plants in small or sparse populations often experience lower reproductive output than their conspecifics in large populations (e.g. Lamont et al. 1993; Ågren 1996; Kéry et al. 2000; Ågren et al. 2008). This phenomenon, known as the Allee effect, is of great concern for conservationists as reduction in population size is a common consequence of habitat fragmentation (Eriksson & Ehrlén 2001). However, the actual extent of Allee effects in plants may be obscured by a bias towards publication of studies that find these effects. In addition, the underlying causes of Allee effects when they are present in plant populations remain poorly understood (Hobbs & Yates 2003; Ghazoul 2005).

Positive relationships between population size and seed production in plants may be due to ecological or genetic factors or a combination of both. Some studies have shown that lower seed set of plants in small populations is due to pollen limitation (Ågren 1996; Ward & Johnson 2005). This is usually an ecological consequence of inadequate pollinator visitation affecting pollen quantity, but there is also evidence that the quality of pollen (e.g. compatibility type) received by stigmas can be lower in small populations (Busch & Schoen 2008). Other evidence for a role for genetic factors in Allee effects includes correlations between inbreeding coefficients and low seed production in small populations (reviewed by Leimu et al. 2006). Increased homozygosity in small populations can be due to loss of alleles through drift, founder effects, biparental inbreeding or higher rates of self-fertilization (cf. Klinkhamer & de Jong 1990; Ellstrand & Elam 1993; Young et al. 1996).

We investigated the relationships between population size and components of pollination success in Satyrium longicauda, a widespread South African terrestrial orchid pollinated by hawkmoths (Harder & Johnson 2005; Jersakova & Johnson 2007). As study organisms, orchids have the advantage of possessing flowers in which both pollen removal and pollen deposition can be quantified precisely in the field (Nilsson 1992). In addition, pollen can easily be stained and tracked in order to determine the rates of pollinator-mediated self-pollination and other pollen fates (cf. Peakall 1989; Johnson et al. 2004, 2005). This is the first study in which the relationship between pollen fates and plant population size has been explored in any detail.

The aims of this study were to establish whether the size of S. longicauda populations influences pollination success, pollen transfer efficiency (PTE), rate of self-pollination and seed production of individual plants.

2. Material and methods

We studied 36 discrete natural populations of S. longicauda in January and February 2003. These were distributed across six grassland subregions (five to seven populations each) close to Pietermaritzburg, South Africa (see the electronic supplementary material). The orchids were the only nectar plants available for hawkmoths at these sites, thus making it unlikely that interspecific interactions would affect pollination. Population size varied from 1 to 450 flowering individuals (median=11). For each population, we recorded population density, calculated as the number of plants per square metre (range: 0.0001–1.0, median=0.013) and degree of isolation, calculated as the distance in metres to the nearest population (range: 50–5000, median=300).

A preliminary breeding system experiment at the ‘Wahroonga’ site revealed that S. longicauda is self-compatible and largely incapable of autonomous self-pollination. Eight randomly chosen plants were bagged to prevent pollinators from visiting them. After anthesis, four flowers per plant were randomly selected to be self-pollinated, four to be cross-pollinated and four to be unmanipulated controls. The median percentage fruit set per plant for self-pollinated flowers (100%, range 50–100%) did not differ significantly from that for cross-pollinated flowers (100%, range 66.6–100%, Z=0.92, p=0.35, Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired samples). However, the mean (±s.e.) angular-transformed percentage of seeds with viable embryos per fruit per plant was much higher in the cross-pollination treatment (back-transformed values, cross: 31.9±5.5%, self: 8.0±2.9%, t7=4.1, p=0.004, paired t-test). Just 21 per cent of flowers in the unmanipulated treatment set fruit and these contained a minimal mean percentage (2.4%) of seeds with embryos.

Natural pollination success was scored for one recently wilted flower selected arbitrarily from each of approximately 30 plants per population. In populations containing fewer than 10 individuals, two to four flowers per plant were collected. Collected flowers were examined under a microscope to establish the number of pollinaria (pollen packages) removed and the number of individual pollen massulae (subunits of pollinaria) deposited on stigmas.

For each population, the PTE, a measure of the proportion of removed pollen that reaches stigmas (cf. Johnson et al. 2004), was calculated as Ms/(Nr×P), where Ms is the mean number of pollen massulae on stigmas; Nr is the mean number of pollinaria removed from flowers; and P is the mean number of pollen massulae per pollinarium. The latter was based on counts for 20–30 pollinaria from each of seven populations.

Pollinaria in 5–15 plants in each of 21 populations were stained with histochemicals (Peakall 1989) to assess the rate of self-pollination and its relationship to population size. Up to three focal groups of five plants each were used in each population and each plant in a focal group was assigned to be stained with one of the following stains: gentian violet; fast green; brilliant blue; rhodamine; and neutral red. These stains do not affect transfer probabilities (Johnson et al. 2004). Staining was accomplished by injecting the histochemicals into the anthers of up to five flowers per plant with a 5 μl Hamilton microsyringe. After 3 days, stained plants were collected and the number of stained pollinaria removed and stained massulae deposited were recorded. The rate of self-pollination was calculated as Ps/PTE, where Ps is the proportion of removed stained pollen that was deposited on stigmas of the source plant and PTE is the overall proportion of removed pollen that was deposited on stigmas in the population (see above).

At fruit maturation, the percentage of flowers that set fruit was determined for plants in 17 populations. We scored fruit set in all the plants in these populations, except for a larger population in which it was scored for a subsample of 20 individuals. We also collected a single fruit from each of 1–18 plants (mean=6.9) in 24 populations and then, using a dissecting microscope, established the percentage of ovules that had developed into seeds with embryos in each of these fruits.

We examined the relationship between population size and population means for various measures of plant reproductive success using two sets of analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models. The first set simultaneously included population size and grassland subregion as independent variables, while the second set in addition included population density and isolation as independent variables.

3. Results

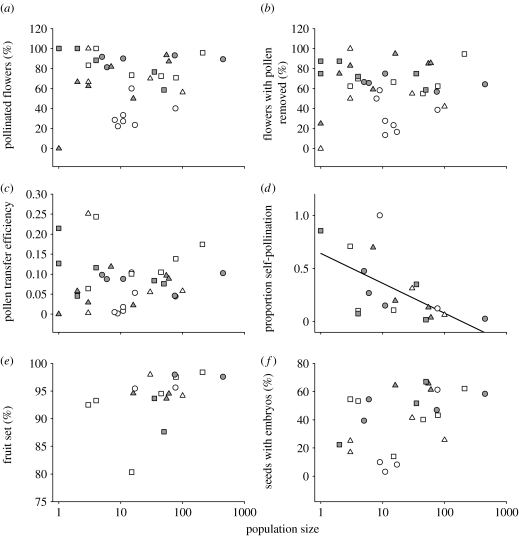

We did not detect significant relationships between population size and measures of male and female pollination success in S. longicauda (figure 1; table 1). While PTE was apparently unaffected by population size, self-pollination was negatively related to population size in ANCOVA models both that did (F1,9=8.61, p=0.017; table 1) and did not take the effects of population density and isolation into account (F1,12=12.6, p=0.004; figure 1; statistically significant also after sequential Bonferroni correction). For both sets of models, neither the proportion of flowers setting fruit or the percentage of seeds with viable embryos showed a significant relationship with population size. No measure of pollination success or fecundity in S. longicauda was significantly related to population density or isolation (table 1).

Figure 1.

(a,b) Relationships between population size and measures of pollination success, (c) PTE, (d) proportion of self-pollination (; subregion NS; log population size, p=0.004) and (e,f) fruit and seed production in S. longicauda. Symbols indicate population clusters belonging to a particular subregion of the study area (treated as a block factor in the ANCOVA; table 1).

Table 1.

ANCOVA models of the relationships between four predictor variables—geographical subregion, population size, population density and population isolation—and population means for measures of pollination success, PTE and seed production in populations of S. longicauda. Values given are F ratios, except for sample size (n) that refers to the number of populations included in the model. Population size, density and isolation were log transformed prior to analysis. Response variables were angular-transformed proportions. (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.)

| response variable | n | subregion | pop size | pop density | pop isolation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pollinated flowers | 29 | 8.38*** | 0.50 | 0.07 | 0.41 |

| flowers with pollen removed | 28 | 3.32* | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.07 |

| pollen transfer efficiency | 29 | 5.15** | 1.80 | 0.81 | 1.18 |

| self-pollination | 18 | 1.51 | 8.61* | 3.20 | 0.79 |

| fruit production | 17 | 0.46 | 2.15 | 0.13 | 0.88 |

| seeds with embryos | 23 | 2.88 | 2.90 | 0.29 | 0.32 |

The variance in the examined measures of reproductive success tended to decrease with increasing population size, but except for PTE (regression of absolute residuals from ANCOVA in table 1 on log population size, b=−0.025, p=0.028, ), this trend was not statistically significant (p>0.33).

4. Discussion

The orchid S. longicauda appears to have an overall resilience to Allee effects in terms of both population size and density. Both small and large populations experience high levels of pollination success, with approximately 70 per cent of flowers having pollen deposited and removed. In terms of PTE, approximately 8 per cent of the pollen removed from flowers reached stigmas, irrespective of population size. Pollen transfer is a notoriously stochastic process (cf. Harder & Johnson 2005) and this could confound the detection of population effects on PTE. However, the proportion of deposited pollen that arose from pollinator-mediated self-pollination was higher in small populations (figure 1; table 1). This is consistent with the theoretical expectation that pollinators should visit more flowers per plant in small or sparse populations, which, in turn, would increase the level of geitonogamous self-pollination (cf. Klinkhamer & de Jong 1990; Goulson 1999).

Although higher levels of self-pollination could potentially result in lower seed production (owing to significant inbreeding depression at the seed development stage, see §2), an effect of population size on fruit and seed production of S. longicauda was not evident in this study (figure 1; table 1). A possible explanation for this is that, despite the increased level of self-pollination in small populations, plants in these populations received sufficient cross-pollen for high levels of seed production. Orchids such as S. longicauda that have sectile pollinia usually receive mixtures of self- and cross-pollen on their stigmas (Johnson et al. 2005). Waites & Ågren (2004) found that variation in seed production of the self-incompatible Lythrum salicaria largely reflected variation in deposition of compatible pollen and that seed production was apparently unaffected by the deposition of large quantities of self-incompatible pollen grains.

Many of the studies, in which a positive effect of population size on plant fecundity has been found, have involved bee-pollinated species (cf. Ågren 1996; Kéry et al. 2000). Bees often forage in a local range and are expected to avoid small unprofitable patches (Goulson 1999). It may be that the resilience of S. longicauda to Allee effects is partially related to its hawkmoth pollinators, which are migratory animals and largely opportunistic foragers. However, any firm conclusions about the link between Allee effects and particular pollinators must await a wider range of studies.

In conclusion, our study shows that seed production and most pollen fates in S. longicauda are not affected by the size, density or isolation of populations. However, the increased level of geitonogamous self-pollination in small populations is an intriguing phenomenon that deserves more attention, both with respect to the underlying process and its possible implications for the genetic structure of populations.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a joint NRF-SIDA grant to S.D.J. and J.Å.

Supplementary Material

Attributes of the study populations of Satyrium longicauda

References

- Ågren J. Population size, pollinator limitation, and seed set in the self-incompatible herb Lythrum salicaria. Ecology. 1996;77:1779–1790. doi:10.2307/2265783 [Google Scholar]

- Ågren J., Ehrlén J., Solbreck C. Spatio-temporal variation in fruit production and seed predation in a perennial herb influenced by habitat quality and population size. J. Ecol. 2008;96:334–345. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2007.01334.x [Google Scholar]

- Busch J.W., Schoen D.J. The evolution of self-incompatibility when mates are limiting. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.01.002. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2008.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellstrand N.C., Elam D.R. Population genetic consequences of small population size: implications for plant conservation. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1993;24:217–242. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.24.110193.001245 [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson O., Ehrlén J. Landscape fragmentation and the viability of plant populations. In: Silvertown J., Antonovics J., editors. Integrating ecology and evolution in a spatial context. Blackwell Science; Oxford, UK: 2001. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazoul J. Pollen and seed dispersal among dispersed plants. Biol. Rev. 2005;80:413–443. doi: 10.1017/s1464793105006731. doi:10.1017/S1464793105006731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulson D. Foraging strategies of insects for gathering nectar and pollen, and implications for plant ecology and evolution. Persp. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 1999;2:185–209. doi:10.1078/1433-8319-00070 [Google Scholar]

- Harder L.D., Johnson S.D. Adaptive plasticity of floral display size in animal-pollinated plants. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2005;272:2651–2657. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3268. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs R.J., Yates C.J. Impacts of ecosystem fragmentation on plant populations: generalising the idiosyncratic. Aust. J. Bot. 2003;51:471–488. doi:10.1071/BT03037 [Google Scholar]

- Jersakova J., Johnson S.D. Protandry promotes male pollination success in a moth-pollinated orchid. Funct. Ecol. 2007;21:496–504. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2007.01256.x [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S.D., Peter C.I., Ågren J. The effects of nectar addition on pollen removal and geitonogamy in the non-rewarding orchid Anacamptis morio. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2004;271:803–809. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2659. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S.D., Neal P.R., Harder L.D. Pollen fates and the limits on male reproductive success in an orchid population. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2005;86:175–190. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00541.x [Google Scholar]

- Kéry M., Matthies D., Spillmann H.-H. Reduced fecundity and offspring performance in small populations of the declining grassland plants Primula veris and Gentiana lutea. J. Ecol. 2000;88:17–30. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2745.2000.00422.x [Google Scholar]

- Klinkhamer P.G.L., de Jong T.J. Effects of plant size, plant density and sex differential nectar reward on pollinator visitation in the protandrous Echium vulgare (Boraginaceae) Oikos. 1990;57:399–405. doi:10.2307/3565970 [Google Scholar]

- Lamont B.B., Klinkhamer P.G.L., Witkowski E.T.F. Population fragmentation may reduce fertility to zero in Banksia goodii: a demonstration of the Allee effect. Oecologia. 1993;94:446–450. doi: 10.1007/BF00317122. doi:10.1007/BF00317122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leimu R., Mutikainen P., Koricheva J., Fischer M. How general are positive relationships between plant population size, fitness and genetic variation? J. Ecol. 2006;94:942–952. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2006.01150.x [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson L.A. Orchid pollination biology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1992;7:255–259. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(92)90170-G. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(92)90170-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peakall R. A new technique for monitoring pollen flow in orchids. Oecologia. 1989;79:361–365. doi: 10.1007/BF00384315. doi:10.1007/BF00384315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waites A.R., Ågren J. Pollinator visitation, stigmatic pollen loads and among-population variation in seed set in Lythrum salicaria. J. Ecol. 2004;92:512–526. doi:10.1111/j.0022-0477.2004.00893.x [Google Scholar]

- Ward M., Johnson S.D. Pollen limitation and demographic structure in small fragmented populations of Brunsvigia radulosa (Amaryllidaceae) Oikos. 2005;108:253–262. doi:10.1111/j.0030-1299.2005.13468.x [Google Scholar]

- Young A., Boyle T., Brown T. The population genetic consequences of habitat fragmentation for plants. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1996;11:413–418. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)10045-8. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(96)10045-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Attributes of the study populations of Satyrium longicauda