Abstract

Objective

The effectiveness of intentional weight loss in reducing cardiovascular disease (CVD) events in type 2 diabetes is unknown. This report describes one-year changes in CVD risk factors in a trial designed to examine the long-term effects of an intensive lifestyle intervention on the incidence of major CVD events.

Research Design and Methods

A multi-centered randomized controlled trial of 5,145 individuals with type 2 diabetes, aged 45–74 years, with body mass index ≥25 kg/m2 (≥27 kg/m2 if taking insulin). An Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI) involving group and individual meetings to achieve and maintain weight loss through decreased caloric intake and increased physical activity was compared to a Diabetes Support and Education (DSE) condition.

Results

Participants assigned to ILI lost an average 8.6% of their initial weight versus 0.7% in DSE group (p<0.001). Mean fitness increased in ILI by 20.9% versus 5.8% in DSE (p<0.001). A greater proportion of ILI participants had reductions in diabetes, hypertension, and lipid-lowering medicines. Mean HbA1c dropped from 7.3% to 6.6% in ILI (p<0.001) versus from 7.3% to 7.2% in DSE. Systolic and diastolic pressure, triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol, and urine albumin/creatinine improved significantly more in ILI than DSE participants (all p<0.01).

Conclusions

At 1 year, ILI resulted in clinically significant weight loss in persons with type 2 diabetes. This was associated with improved diabetes control and CVD risk factors and reduced medicine use in ILI versus DSE. Continued intervention and follow-up will determine whether these changes are maintained and will reduce CVD risk.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00017953

INTRODUCTION

Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) is an NIH-funded clinical trial investigating the long-term health impact of an intensive lifestyle intervention in 5145 overweight or obese adults with type 2 diabetes. It is being conducted in 16 centers in the United States. The design and methods of this trial have been reported elsewhere (1) as have the baseline characteristics of the randomized cohort (2). Its primary objective is to determine whether cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in persons with type 2 diabetes can be reduced by long-term weight reduction, achieved by an Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI) that includes diet, physical activity, and behavior modification (3). The goal of this intervention is for individuals to achieve and maintain a loss of at least 7% of initial body weight. Results of the ILI group will be compared with a usual-care condition that includes Diabetes Support and Education (DSE). Follow-up of Look AHEAD participants is ongoing and is planned to extend for up to 11.5 years. For the study to continue for this period, two feasibility criteria were set by the Look AHEAD study group based on 1-year changes: 1) a difference between ILI and DSE participants of >5 percentage points in the average percent change in weight from baseline; and 2) an average absolute percent weight loss from baseline among ILI participants (not using insulin at baseline) of >5%. This report documents the success of Look AHEAD in meeting these 1-year feasibility criteria and describes changes in the two groups at the end of the first year in fitness, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and use of medicines.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Participants

For inclusion in the study, participants were 45–74 years of age (which was changed to 55–74 years during the second year of recruitment to increase the anticipated cardiovascular event rate), had a body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2 (≥27 kg/m2 if currently taking insulin), HbA1c ≤11%, blood pressure ≤160 (systolic) and ≤100 (diastolic) mm Hg and triglycerides <600 mg/dL.

Participants completed maximal graded exercise tests to assess fitness prior to randomization. The test consisted of the participant walking on a motorized treadmill at a constant self-selected walking speed (1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 3.5, or 4.0 mph). The elevation of the treadmill was initially set at 0% grade and increased by 1.0% every minute. Heart rate and rating of perceived exertion (RPE) using the Borg 15-category scale (4) were measured during the final 10 seconds of each exercise stage and at the point of test termination. To determine eligibility at baseline, a maximal exercise test was performed. For individuals not taking prescription medicine that would affect heart rate response during exercise (e.g. beta blocker), the baseline test was considered valid if the individual achieved at least 85% of age-predicted maximal heart rate (age predicted maximal heart rate = 220 minus age) and a minimum of 4 metabolic equivalents (METS). For individuals taking prescription medicine that would affect the heart rate response during exercise, the baseline test was considered valid if the individual achieved a RPE of at least 18 and a minimum of 4 METS. Individuals not achieving these criteria were not eligible for randomization into Look AHEAD. METS at each exercise stage and at test termination were estimated from a standardized formula that incorporates walking speed and grade (5).

The goal was to recruit approximately equal numbers of men and women, with ≥33% from racial and ethnic minority groups. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before screening and at enrollment, consistent with the Helsinki Declaration and the guidelines of each center’s institutional review board. After all eligibility criteria were confirmed, participants were randomly assigned with equal probability to either ILI or the DSE comparison condition. Randomization was stratified by clinical center.

Interventions

Prior to randomization, all study participants were required to complete a 2-week run-in period which included successful self-monitoring of diet and physical activity, and they were provided an initial session of diabetes education with particular emphasis on aspects of diabetes care related to the trial such as management of hypoglycemia and foot care. The session stressed the importance of eating a healthy diet and being physically active for both weight loss and improvement of glycemic control. All individuals who smoked were encouraged to quit and were provided self-help materials and/or referral to local programs as appropriate.

The weight loss intervention prescribed in the first year has been described in detail (3). Briefly, it combines diet modification and increased physical activity and was designed to induce a minimum weight loss of 7% of initial body weight during the first year. Individual participants were encouraged to lose ≥10% of their initial body weight, with the expectation that aiming high would ensure that a greater number of participants would achieve the minimum 7% weight loss. The intervention was modeled on group behavioral programs developed for the treatment of obese patients with type 2 diabetes and included treatment components from the Diabetes Prevention Program (6,7,8) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s (NHLBI) clinical guidelines (9). During months 1–6, participants were seen weekly with 3 group meetings and 1 individual session per month. During months 7–12, group sessions were provided every other week and the monthly individual session was continued. Sessions were led by intervention teams that included registered dietitians, behavioral psychologists, and exercise specialists.

Caloric restriction was the primary method of achieving weight loss. The macronutrient composition of the diet was structured to enhance glycemic control and to improve CVD risk factors. It included a maximum of 30% of total calories from fat (with a maximum of 10% of total calories from saturated fat) and a minimum of 15% of total calories from protein (10). Participants were prescribed portion-controlled diets, which included the use of liquid meal replacements (provided free of charge) and frozen food entrées, as well as structured meal plans (comprised of conventional foods) for those who declined the meal replacements. Monthly reviews took place at an individual session to reassess progress.

The physical activity program prescribed in the ILI relied heavily on home-based exercise with gradual progression toward a goal of 175 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity per week. While walking was encouraged, participants were allowed to choose other types of moderate-intensity physical activity, and programs were tailored based on the results of a baseline physical fitness test and safety concerns.

The ILI included a “toolbox” approach, as used in the Diabetes Prevention Program (6,7), to help participants achieve and maintain the study’s weight loss and activity goals. Use of the “toolbox” was based on a pre-set algorithm and assessment of participant progress. After the first 6 months, the “toolbox” algorithm included use of a weight loss medicine (orlistat) and/or advanced behavioral strategies for individuals who had difficulty in meeting the trial’s weight or activity goals. Specific protocols were used to determine when to initiate medication or other approaches, to monitor participants, and to determine when to stop a particular intervention.

Participants assigned to DSE attended the initial pre-randomization diabetes education session (described above) and were invited to 3 additional group sessions during the first year. A standard protocol was used for conducting these sessions, which provided information and opportunities for discussing topics related to diet, physical activity, and social support. However, the DSE group was not weighed at these sessions and received no counseling in behavioral strategies for changing diet and activity.

Ongoing clinical care

All participants in the ILI and DSE groups continued to receive care for their diabetes and all other medical conditions from their own physicians. Changes in all medicines were made by the participants’ own physicians, except for temporary reductions in hyperglycemia medicines during periods of intensive weight loss intervention, which were made by the intervention sites following a standardized treatment protocol aimed at avoiding hypoglycemia.

Assessments

Anthropometry

All participants were scheduled to attend baseline and 1-year assessments, at which measures were collected by staff members who were masked to participants’ intervention assignments. Weight and height were assessed in duplicate using a digital scale and a standard stadiometer. Seated blood pressure was measured in duplicate, using an automated device after a 5-minute rest. Participants brought all prescription medicines to the clinic to ensure recording accuracy. History of cardiovascular disease was based on self-report of myocardial infarction, stroke, transient ischemic event, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, or coronary artery bypass graft.

Fitness

At 1 year, a submaximal exercise test was performed and terminated when the participant first achieved or exceeded 80% of age-predicted maximal heart rate (HRMax in beats/minute= 220 minus age). If the participant was taking a beta blocking medicine at baseline or 1-year assessment, the submaximal test was terminated at the point when the participant first reported achieving or exceeding 16 on the 15-category RPE scale. For participants not taking a beta blocking medicine, change in cardiorespiratory fitness was computed as the difference in estimated METS between points during the baseline and 1-year tests when >80% of age-predicted maximal heart rate was attained. For participants taking beta blocking medicine at either baseline or 1-year, change in cardiorespiratory fitness was computed as the difference in estimated METS between points during the baseline and 1-year tests when RPE>16 was attained.

Serum measures

The Central Biochemistry Laboratory (Northwest Lipid Research Laboratories, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.) conducted standardized analyses of shipped frozen specimens. HbA1c was measured by a dedicated ion exchange, high performance liquid chromatography instrument (Biorad Variant 11). Fasting serum glucose was measured enzymatically on a Hitachi 917 autoanalyzer using hexokinase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Total serum cholesterol and triglycerides were measured enzymatically using methods standardized to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Reference Methods. LDL-cholesterol was calculated by the Friedewald equation (11). HDL-cholesterol was analyzed by the treatment of whole plasma with dextran sulfate – Mg++ to precipitate all of the apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins. Albumin and creatinine concentrations were measured from spot urine samples.

Participants were classified as having the metabolic syndrome using the criteria proposed by the National Cholesterol Education Program ATP III panel (12). They also were classified according to their success in meeting treatment goals published by the American Diabetes Association (13). Glycemic control was defined as HbA1c <7.0%; blood pressure control as systolic blood pressure <130 and diastolic blood pressure <80 mm Hg; and lipid control as LDL-cholesterol <100 mg/dL.

Statistical methods

Cross-sectional differences between participants assigned to the ILI and DSE conditions were assessed using analysis of covariance and logistic regression, with adjustment for clinical center (the sole factor used to stratify randomization). Changes in outcome measures from baseline to 1 year were compared using analysis of covariance and Mantel-Haenszel tests.

RESULTS

Participants’ baseline characteristics

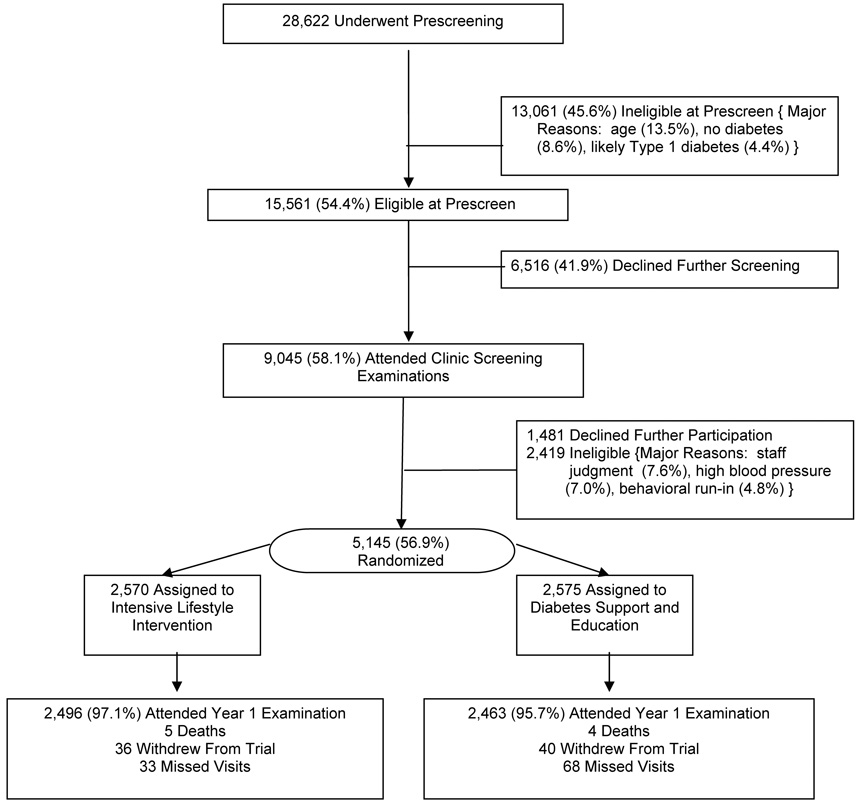

Figure 1 describes trial enrollment. Of the 28,622 individuals who provided information during prescreening, 15,561 (54.4%) were found to be eligible for clinic visits to confirm eligibility. The most common reasons for ineligibility at this stage were related to age (13.5%), lack of diabetes (8.6%), and the likelihood that the diabetes was Type 1 (4.4%). Of the 9,045 (58.1%) who attended clinic visits, 5,145 (56.9%) were ultimately randomized: 2,570 participants were assigned to ILI and 2,575 to DSE. At this stage, individuals were most commonly ineligible due to staff judgment (7.6%), elevated blood pressure (7.0%), or incomplete behavioral run-ins (4.8%).

FIGURE 1.

Enrollment of Look AHEAD participants.

At baseline, the characteristics of participants assigned to the two intervention conditions were similar (Table 1). Overall, 14.0% reported a history of cardiovascular disease, 94.0% met the National Cholesterol Education program ATPIII definition for the metabolic syndrome (12), 15.3% were taking insulin, 87.5% were using diabetes medicines (including insulin), 75.3% were using anti-hypertensive medicines, and 51.0% were using lipid-lowering medicines.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the ILI and DSE groups: mean (standard deviation) or frequency (percent).

| Characteristic | Intervention Assignment |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intensive Lifestyle Intervention N=2,570 |

Diabetes Support and Education N=2,575 |

||

| Female | 1526 (59.3) | 1537 (59.6) | 0.85* |

| Ethnicity | |||

| African-American | 399 (15.5) | 404 (15.7) | |

| American Indian / Alaskan Native | 130 (5.1) | 128 (5.0) | |

| Asian / Pacific Islander | 29 (1.1) | 21 (0.8) | 0.28* |

| Hispanic / Latino | 339 (13.2) | 338 (13.2) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1618 (63.1) | 1628 (63.3) | |

| Other / multiple | 48 (1.9) | 50 (1.9) | |

| Age, years | 58.6 (6.8) | 58.9 (6.9) | 0.12† |

| History of cardiovascular disease‡ | 371 (14.4) | 351 (13.6) | 0.40* |

| Metabolic síndrome | 2406 (93.6) | 2431 (94.4) | 0.32* |

| Use of insulin | 381 (14.8) | 408 (15.8) | 0.31* |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | |||

| Females | 36.3 (6.2) | 36.6 (6.0) | 0.15† |

| Males | 35.3 (5.7) | 35.1 (5.2) | 0.41† |

| Weight, kg | |||

| Females | 94.8 (17.9) | 95.4 (17.3) | 0.34† |

| Males | 108.9 (19.0) | 109.0 (18.0) | 0.94† |

| Waist circumference, cm | |||

| Females | 110.5 (13.6) | 111.2 (13.2) | 0.14† |

| Males | 118.7 (14.0) | 118.4 (12.9) | 0.62† |

| Fitness, METS | |||

| Females | 6.7 (1.7) | 6.6 (1.7) | 0.38† |

| Males | 7.9 (2.1) | 8.0 (2.2) | 0.89† |

Chi square test

Analysis of covariance, adjusted for clinical center

Self-report of prior myocardial infarction, stroke, TIA (transient ischemic attack), angioplasty/stent, coronary artery bypass graft, carotid endarterectomy, angioplasty of lower extremity, aortic aneurysm repair, or heart failure

Baseline BMI, weight, waist circumference and fitness are given by sex in Table 1. A BMI of ≥30.0 kg/m2 was present in 85.1% of participants.

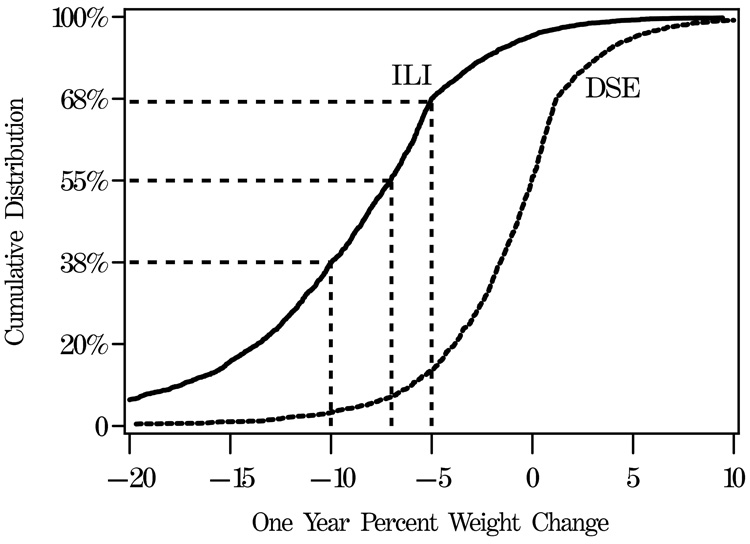

Weight loss

The 1-year examination was attended by 2,496 (97.1%) of the ILI and 2,463 (95.7%) of the DSE participants (p=0.004). Among the factors listed in Table 1, only the distribution of baseline insulin use significantly varied between non-attendees (21.0%) versus attendees (15.1%): p=0.04. Over the first year of the trial, the ILI group lost an average of 8.6% (standard deviation, 6.9%) of initial body weight compared with 0.7% (4.8%) in the DSE group (p<0.001). Figure 2A portrays the cumulative distribution of weight changes in the two groups. Within the ILI group, 37.8% of participants met the individual weight loss goal (≥10% of initial weight) and 55.2% met the group average goal (≥7%) compared with 3.2% and 7.0% of DSE participants, respectively. These weight losses were accompanied by greater mean reductions in waist circumference in the ILI than DSE group, with mean decreases of 6.2 (10.2) cm versus 0.5 (8.5) cm: p<0.001.

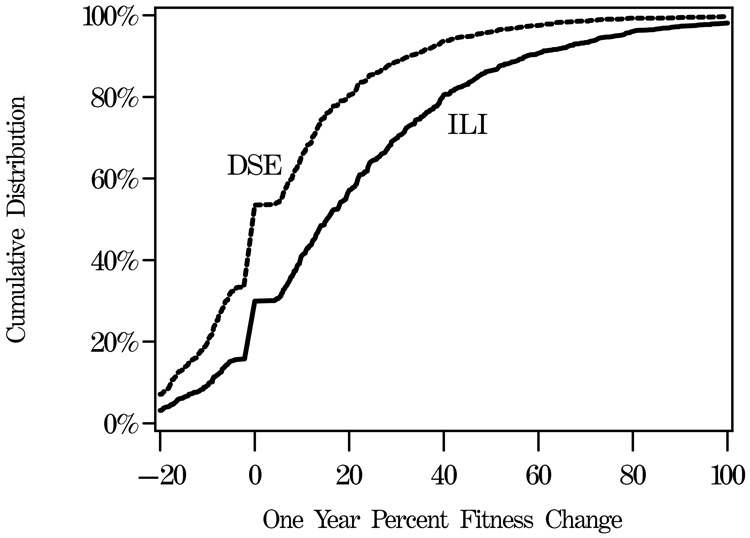

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of one-year changes in percent weight and fitness (METS) among individuals grouped by intervention assignment. Dashed lines are used to indicate the percentages of ILI participants with weight losses exceeding 10%, 7%, and 5%, respectively.

In the ILI group, the average weight loss among baseline insulin users was 7.6% (7.0%) compared with 8.7% (6.9%) in non-users (p=0.002). Insulin users, compared with non-insulin users, were less likely to achieve weight losses >10% (33.5% versus 38.5%) or >7% (47.8% versus 56.4%). In the DSE group, average weight loss was 0.3% (5.1%) among insulin users versus 0.8% (4.7%) among non-insulin users.

Changes in fitness

Figure 2B illustrates the cumulative distribution of measured 1-year fitness changes in 4,246 participants who had repeat testing. Fitness tended to increase in both groups, however increases were more prevalent and tended to be larger among ILI participants; 70.1% of the ILI participants had increased fitness at 1-year compared with 46.3% of the DSE participants (p<0.001). Fitness increases averaged 20.9% (29.1%) among ILI participants compared with 5.8% (22.0%) among DSE participants (p<0.001). These changes could not be fully accounted for by changes in weight. After covariate adjustment for weight changes, the fitted mean difference in fitness increases between groups remained statistically significant (15.9% for ILI versus 10.8% for DSE, p<0.001).

Changes in medicines and cardiovascular risk factors

During the first year, use of glucose lowering medicines among ILI participants decreased from 86.5% to 78.6%, while it increased from 86.5% to 88.7% among DSE participants (p<0.001). As shown in Table 2, despite this difference, mean fasting glucose declined more among ILI participants compared with DSE participants (p<0.001), as did mean HbA1c (p<0.001).

TABLE 2.

Changes in measures of diabetes control, blood pressure control, measures of lipid/lipoproteins control, albumin/creatinine, and prevalence of metabolic syndrome among participants seen at year 1: mean or percent (standard error).

| Measure | Intensive Lifestyle Intervention N=2,496 |

Diabetes Support and Education N=2,463 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of diabetes medicines (%) | |||

| Baseline | 86.5 (0.7) | 86.5 (0.7) | 0.93* |

| Year 1 | 78.6 (0.8) | 88.7 (0.6) | <0.001* |

| Change | −7.8 (0.6) | 2.2 (0.5) | <0.001† |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | |||

| Baseline | 151.9 (0.9) | 153.6 (0.9) | 0.21‡ |

| Year 1 | 130.4 (0.8) | 146.4 (0.9) | <0.001‡ |

| Change | −21.5 (0.9) | −7.2 (0.9) | <0.001‡ |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | |||

| Baseline | 7.25 (0.02) | 7.29 (0.02) | 0.26‡ |

| Year 1 | 6.61 (0.02) | 7.15 (0.02) | <0.001‡ |

| Difference | −0.64 (0.02) | −0.14 (0.02) | <0.001‡ |

| Use of antihypertensive medicines (%) | |||

| Baseline | 75.3 (0.9) | 73.7 (0.9) | 0.23* |

| Year 1 | 75.2 (0.9) | 75.9 (0.9) | 0.54* |

| Change | −0.1 (0.6) | 2.2 (0.6) | 0.02† |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | |||

| Baseline | 128.2 (0.4) | 129.4 (0.3) | 0.01‡ |

| Year 1 | 121.4 (0.4) | 126.6 (0.4) | <0.001‡ |

| Change | −6.8 (0.4) | −2.8 (0.3) | <0.001‡ |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | |||

| Baseline | 69.9 (0.2) | 70.4 (0.2) | 0.11‡ |

| Year 1 | 67.0 (0.2) | 68.6 (0.2) | <0.001‡ |

| Change | −3.0 (0.2) | −1.8 (0.2) | <0.001‡ |

| Use of lipid-lowering medicines (%) | |||

| Baseline | 49.4 (1.0) | 48.4 (1.0) | 0.52* |

| Year 1 | 53.0 (1.0) | 57.8 (1.0) | <0.001* |

| Change | 3.7 (0.8) | 9.4 (0.8) | <0.001† |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | |||

| Baseline | 112.2 (0.4) | 112.4 (0.6) | 0.78‡ |

| Year 1 | 107.0 (0.6) | 106.7 (0.7) | 0.74‡ |

| Change | −5.2 (0.6) | −5.7 (0.6) | 0.49‡ |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | |||

| Baseline | 43.5 (0.2) | 43.6 (0.2) | 0.80‡ |

| Year 1 | 46.9 (0.3) | 44.9 (0.2) | <0.001‡ |

| Change | 3.4 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.1) | <0.001‡ |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | |||

| Baseline | 182.8 (2.3) | 180.0 (2.4) | 0.38‡ |

| Year 1 | 152.5 (1.8) | 165.4 (1.9) | <0.001‡ |

| Change | −30.3 (2.0) | −14.6 (1.8) | <0.001‡ |

| Albumin/Creatinine >30.0 ug/mg (%) | |||

| Baseline | 16.4 (0.7) | 16.9 (0.8) | 0.69‡ |

| Year 1 | 12.5 (0.7) | 15.4 (0.7) | 0.005‡ |

| Change | −3.9 (0.6) | −1.5 (0.6) | 0.002‡ |

| Metabolic syndrome (%) | |||

| Baseline | 93.6 (0.5) | 94.4 (0.5) | 0.23‡ |

| Year 1 | 78.9 (0.8) | 87.3 (0.7) | <0.001‡ |

| Change | −14.7 (0.8) | −7.1 (0.7) | <0.001‡ |

Logistic regression with adjustment for clinical site

Mantel-Haenszel test with adjustment for clinical site

Analysis of covariance with adjustment for clinical site

As described in Table 2, the prevalence of antihypertensive medicine use remained unchanged among ILI participants, but increased by 2.2% (0.6%) among DSE participants (p=0.02). Mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels declined in both groups, but reductions were significantly greater in ILI than in DSE participants (both p<0.001).

Use of lipid-lowering medicines increased in both groups; however, the increase was significantly smaller among ILI participants than in DSE participants (p<0.001). Mean levels of LDL-cholesterol declined by similar magnitudes in both groups (p=0.49). Mean HDL-cholesterol levels increased more among ILI than DSE participants (p<0.001) while mean triglyceride levels decreased more among ILI (p<0.001).

The prevalence of urine albumin/creatinine ratios ≥30.0 ug/mg decreased more among ILI participants than DSE participants (p=0.002).

Classification of participants

The percentage meeting criteria for the metabolic syndrome decreased significantly more among ILI than DSE participants (p<0.001). As shown in Table 2, the prevalence declined from 93.6 to 78.9 in the ILI group, compared with a decline of 94.4% to 87.3% in the DSE group. The prevalence of meeting ADA goals for HbA1c, blood pressure, and LDL-cholesterol increased among both ILI and DSE participants (Table 3). These increases were greater among ILI participants (p<0.001) for HbA1c and blood pressure 26.4% (1.0%) vs. 5.4% (1.07%) and 15.1% (1.1%) vs. 7.0% (1.2%) respectively (both p<0.001), but were of similar magnitudes for LDL-cholesterol. The prevalence simultaneously meeting all three goals increased from 10.8% to 23.6% among ILI participants compared with an increase from 9.5% to 16.0% among DSE participants (p<0.001).

TABLE 3.

Changes percentage of participants meeting American Diabetes Association goals for risk factors: percent (standard error).

| Measure | Intensive Lifestyle Intervention | Diabetes Support and Education | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin A1c < 7% (%) | |||

| Baseline | 46.3 (1.0) | 45.4 (1.0) | 0.50* |

| Year 1 | 72.7 (0.9) | 50.8 (1.0) | <0.001* |

| Difference | 26.4 (1.0) | 5.4 (1.0) | <0.001† |

| Blood pressure <130/80 mmHg (%) | |||

| Baseline | 53.5 (1.0) | 49.9 (1.0) | 0.01* |

| Year 1 | 68.6 (0.9) | 57.0 (1.0) | <0.001* |

| Change | 15.1 (1.1) | 7.0 (1.2) | <0.001† |

| LDL-cholesterol <100 mg/dl (%) | |||

| Baseline | 37.1 (1.0) | 36.9 (1.0) | 0.87* |

| Year 1 | 43.8 (1.0) | 44.9 (1.0) | 0.45* |

| Change | 6.7 (1.0) | 8.0 (1.0) | 0.34† |

| All three goals | |||

| Baseline | 10.8 (0.6) | 9.5 (0.6) | 0.13* |

| Year 1 | 23.6 (0.8) | 16.0 (0.7) | <0.001* |

| Change | 12.8 (0.9) | 6.5 (0.8) | <0.001† |

Logistic regression with adjustment for clinical site

Mantel-Haenszel test with adjustment for clinical site

CONCLUSIONS

The present results show that clinically significant weight loss is broadly achievable in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus and is associated with improved cardiovascular risk factors. At 1 year, participants in ILI achieved an average loss of 8.6% of initial body weight and a 21% improvement in cardiovascular fitness. Separate manuscripts are underway that will provide details on the relative contributions of individual strategies (e.g. meal replacement, orlistat) towards this successful outcome. Even participants on insulin lost an average of 7.6% of initial weight. The ILI was associated with an increase from 46% to 73% in the participants who met the ADA goal of HbA1c ≤ 7% and a doubling in the percent of individuals who met all three of the ADA goals for glycemic control, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.

Look AHEAD is the first large clinical trial to compare an intensive weight loss intervention (i.e. ILI) with a support and education group (i.e. DSE) in individuals with type 2 diabetes. As expected, participants in the ILI group had significantly greater weight loss and improvement in fitness at 1 year than those in the DSE group. Moreover, they had a significantly greater decrease in the number of medicines used to treat their diabetes and blood pressure. Despite the greater reductions in these medicines, the ILI group showed greater improvements in their glycemic control, albumin:creatinine ratio, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, triglycerides, and HDL-cholesterol than the DSE group. Changes in LDL-cholesterol were comparable in the two groups. Of particular note is that mean HbA1c fell from 7.2% to 6.6%. Few studies, even trials of newer diabetes medicines, have achieved levels of HbA1c of 6.6%. Although the DSE group had smaller benefits than ILI, it is important to recognize that these participants also experienced some improvement (not worsening), on average, in weight, fitness, and cardiovascular risk factors.

The Look AHEAD participants are of similar ethnic distribution to that observed in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2000 (14), but their average baseline BMI was higher. Overall, they are healthier than diabetic persons in NHANES with regard to glucose, HbA1c, and lipid levels and are less likely to smoke. A large percentage was taking medicines for risk factors at study enrollment and many had a significant history of cardiovascular disease. Despite the level of health of the sample, fewer than half met the ADA goal for HbA1c and only 10% met all 3 ADA goals (13). The ILI was extremely effective in increasing the percent of participants who met these goals. At 1 year, 72.7% met the goal for HbA1c and 23.6% met all 3 goals, compared with only 50.8% and 16.0%, respectively, for the DSE group. The ILI also was associated with significantly greater remission of the metabolic syndrome than was the DSE intervention.

Several large clinical trials of individuals with impaired glucose tolerance (6,15) or hypertension (16,17) have achieved average weight losses of 4% to 7% at 1 year using intensive lifestyle interventions that emphasized behavior change. These weight losses were associated with marked improvement in health status. Although a number of smaller studies (18,19) have shown that it is possible, using strong behavioral programs, to produce significant weight loss in patients with type 2 diabetes, most studies of weight loss in such individuals have had only modest success. It appears that individuals with diabetes (especially those on insulin) may have more difficulty losing weight and then keeping it off than those without diabetes (20). For example, among adult Pima Indians receiving standard clinical care for type 2 diabetes, those treated with insulin lost less weight than those treated without drugs or with oral agents (21). The larger weight losses in Look AHEAD than in prior clinical trials may be attributable to the combination of group and individual contact, the higher physical activity goal that was prescribed, and/or the more intense dietary intervention, which included not only calorie and fat restriction but also structured meal plans, each of which has previously been associated with successful weight loss and maintenance (22,23,24,25). Although Look AHEAD participants using insulin achieved less average weight loss than those not on insulin (7.6% versus 8.7%), the weight loss of the participants on insulin demonstrates that use of insulin does not prevent successful weight loss. A recent meta-analysis found that the use of meal replacements increased both short and long-term average weight loss by about 2.5 kg, compared with prescription of a conventional reducing diet with the same calorie goals (26). Our findings that participants in the ILI had significant improvements in cardiovascular risk factors confirms prior studies showing that initial weight loss in type 2 diabetes is associated with improved glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors at 1 year (27,28). However, the long-term impact of such weight losses remains unclear.

Estimated fitness improved in both groups over the year, but it improved significantly more in the ILI group. It is unknown how much of the improvement in either treatment group was due to measurement variability and greater familiarity with the testing procedure at the 1 year visit and how much represented physiologic change. The difference in improvement between the ILI and DSE groups, however, can be taken as a measure of the ILI treatment effect. This treatment effect persisted even after adjustment for the 1-year weight change. The changes in fitness compared favorably with those observed in prior studies with both diabetic (29,30) and non-diabetic (29,31,32) participants. Thus the modest increase in physical activity, primarily walking, had a very beneficial effect. This may translate into a lower rate of cardiovascular events, including mortality, as suggested in some observational studies (33,34).

The primary outcome of the Look AHEAD trial is the effect of weight loss on the development of cardiovascular disease. Although the difference between the ILI and DSE groups in the change in risk factors at 1 year points to the potential cardiovascular benefits of the ILI, we will need several additional years to determine whether the initial weight loss can be maintained, whether weight loss has a long-term effect on the risk factors, and whether the favorable risk factor changes translate into reduced cardiovascular events. This is critical information for establishing evidence-based recommendations with regard to weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in individuals with diabetes.

Acknowledgments

Authors

Xavier Pi-Sunyer, MD; George Blackburn, MD, PhD; Frederick L. Brancati, MD, MHS; George A. Bray, MD; Renee Bright, MS; Jeanne M. Clark, MD, MPH; Jeffrey M. Curtis, MD, MPH; Mark A. Espeland, PhD; John P. Foreyt, PhD; Kathryn Graves, MPH, RD, CDE; Steven M. Haffner, MD; Barbara Harrison, MS; James O. Hill, PhD; Edward S. Horton, MD; John Jakicic, PhD; Robert W. Jeffery, PhD; Karen C. Johnson, MD, MPH; Steven Kahn MB, ChB; David E. Kelley, MD; Abbas E. Kitabchi, MD, PhD; William C. Knowler, MD, DrPH; Cora E. Lewis, MD, MSPH; Barbara J. Maschak-Carey, MSN, CDE; Brenda Montgomery, RN, MS, CDE; David M. Nathan, MD; Jennifer Patricio, MS; Anne Peters, MD; J. Bruce Redmon, MD; Rebecca S. Reeves, DrPH, RD; Donna H. Ryan, MD; Monika Safford, MD; Brent Van Dorsten, PhD; Thomas A. Wadden, PhD; Lynne Wagenknecht, DrPH; Jacqueline Wesche-Thobaben, RN,BSN,CDE; Rena R. Wing, PhD; Susan Z. Yanovski, MD

Clinical Sites

The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Frederick L. Brancati, MD, MHS1; Jeff Honas, MS2; Lawrence Cheskin, MD3; Jeanne M. Clark, MD, MPH3; Kerry Stewart, EdD3; Richard Rubin, PhD3; Jeanne Charleston, RN; Kathy Horak, RD

Pennington Biomedical Research Center George A. Bray, MD1; Kristi Rau2; Allison Strate, RN2; Brandi Armand, LPN2; Frank L. Greenway, MD3; Donna H. Ryan, MD3; Donald Williamson, PhD3; Amy Bachand; Michelle Begnaud; Betsy Berhard; Elizabeth Caderette; Barbara Cerniauskas; David Creel; Diane Crow; Helen Guay; Nancy Kora; Kelly LaFleur; Kim Landry; Missy Lingle; Jennifer Perault; Mandy Shipp, RD; Marisa Smith; Elizabeth Tucker

The University of Alabama at Birmingham Cora E. Lewis, MD, MSPH1; Sheikilya Thomas MPH2; Monika Safford, MD3; Vicki DiLillo, PhD; Charlotte Bragg, MS, RD, LD; Amy Dobelstein; Stacey Gilbert, MPH; Stephen Glasser, MD; Sara Hannum, MA; Anne Hubbell, MS; Jennifer Jones, MA; DeLavallade Lee; Ruth Luketic, MA, MBA, MPH; Karen Marshall; L. Christie Oden; Janet Raines, MS; Cathy Roche, RN, BSN; Janet Truman; Nita Webb, MA; Audrey Wrenn, MAEd

Harvard Center

Massachusetts General Hospital: David M. Nathan, MD1; Heather Turgeon, RN, BS, CDE2; Kristina Schumann, BA2; Enrico Cagliero, MD3; Linda Delahanty, MS, RD3; Kathryn Hayward, MD3; Ellen Anderson, MS, RD3; Laurie Bissett, MS, RD; Richard Ginsburg, PhD; Valerie Goldman, MS, RD; Virginia Harlan, MSW; Charles McKitrick, RN, BSN, CDE; Alan McNamara, BS; Theresa Michel, DPT, DSc CCS; Alexi Poulos, BA; Barbara Steiner, EdM; Joclyn Tosch, BA

Joslin Diabetes Center: Edward S. Horton, MD1; Sharon D. Jackson, MS, RD, CDE2; Osama Hamdy, MD, PhD3; A. Enrique Caballero, MD3; Sarah Bain, BS; Elizabeth Bovaird, BSN, RN; Ann Goebel-Fabbri, PhD; Lori Lambert, MS, RD; Sarah Ledbury, MEd, RD; Maureen Malloy, BS; Kerry Ovalle, MS, RCEP, CDE

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center: George Blackburn, MD, PhD1; Christos Mantzoros, MD, DSc3; Kristina Day, RD; Ann McNamara, RN

University of Colorado Health Sciences Center James O. Hill, PhD1; Marsha Miller, MS, RD2; JoAnn Phillipp, MS2; Robert Schwartz, MD3; Brent Van Dorsten, PhD3; Judith Regensteiner, PhD3; Salma Benchekroun MS; Ligia Coelho, BS; Paulette Cohrs, RN, BSN; Elizabeth Daeninck, MS, RD; Amy Fields, MPH; Susan Green; April Hamilton, BS, CCRC; Jere Hamilton, BA; Eugene Leshchinskiy; Michael McDermott, MD; Lindsey Munkwitz, BS; Loretta Rome, TRS; Kristin Wallace, MPH; Terra Worley, BA

Baylor College of Medicine John P. Foreyt, PhD1; Rebecca S. Reeves, DrPH, RD2; Henry Pownall, PhD3; Ashok Balasubramanyam, MBBS3; Peter Jones, MD3; Michele Burrington, RD; Chu-Huang Chen, MD, PhD; Allyson Clark, RD; Molly Gee, MEd, RD; Sharon Griggs; Michelle Hamilton; Veronica Holley; Jayne Joseph, RD; Patricia Pace, RD: Julieta Palencia, RN; Olga Satterwhite, RD; Jennifer Schmidt; Devin Volding, LMSW; Carolyn White

University of California at Los Angeles School of Medicine Mohammed F. Saad, MD1; Siran Ghazarian Sengardi, MD2; Ken C. Chiu, MD3; Medhat Botrous; Michelle Chan, BS; Kati Konersman, MA, RD, CDE; Magpuri Perpetua, RD

The University of Tennessee Health Science Center Karen C. Johnson, MD, MPH1; Helen Lambeth, RN, BSN2; Carolyn M. Gresham, RN2; Abbas E. Kitabchi, MD, PhD3; Stephanie A. Connelly, MD, MPH3; Lynne Lichtermann, RN, BSN

University of Minnesota Robert W. Jeffery, PhD1; Carolyn Thorson, CCRP2; John P. Bantle, MD3; J. Bruce Redmon, MD3; Richard S. Crow, MD3; Scott Crow, MD3; Susan K Raatz, PhD, RD3; Kerrin Brelje, MPH, RD; Carolyne Campbell; Jeanne Carls, MEd; Tara Carmean-Mihm, BA; Emily Finch, MA; Anna Fox, MA; Elizabeth Hoelscher, MPH, RD, CHES; La Donna James; Vicki A. Maddy, BS, RD; Therese Ockenden, RN; Birgitta I. Rice, MS, RPh CHES; Tricia Skarphol, BS; Ann D. Tucker, BA; Mary Susan Voeller, BA; Cara Walcheck, BS, RD

St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital Center Xavier Pi-Sunyer, MD1; Jennifer Patricio, MS2; Stanley Heshka, PhD3; Carmen Pal, MD3; Lynn Allen, MD; Diane Hirsch, RNC, MS, CDE; Mary Anne Holowaty, MS, CN

University of Pennsylvania Thomas A. Wadden, PhD1; Barbara J. Maschak-Carey, MSN, CDE2; Stanley Schwartz, MD3; Gary D. Foster, PhD3; Robert I. Berkowitz, MD3; Henry Glick, PhD3; Shiriki K. Kumanyika, PhD, RD, MPH3; Johanna Brock; Helen Chomentowski; Vicki Clark; Canice Crerand, PhD; Renee Davenport; Andrea Diamond, MS, RD; Anthony Fabricatore, PhD; Louise Hesson, MSN; Stephanie Krauthamer-Ewing, MPH; Robert Kuehnel, PhD; Patricia Lipschutz, MSN; Monica Mullen, MS, RD; Leslie Womble, PhD, MS; Nayyar Iqbal, MD

University of Pittsburgh David E. Kelley, MD1; Jacqueline Wesche-Thobaben, RN, BSN, CDE2; Lewis Kuller, MD, DrPH3; Andrea Kriska, PhD3; Janet Bonk, RN, MPH; Rebecca Danchenko, BS; Daniel Edmundowicz, MD3; Mary L. Klem, PhD, MLIS3; Monica E. Yamamoto, DrPH, RD, FADA 3; Barb Elnyczky, MA; George A. Grove, MS; Pat Harper, MS, RD, LDN; Janet Krulia, RN, BSN, CDE; Juliet Mancino, MS, RD, CDE, LDN; Anne Mathews, MS, RD, LDN; Tracey Y. Murray, BS; Joan R. Ritchea; Jennifer Rush, MPH; Karen Vujevich, RN-BC, MSN, CRNP; Donna Wolf, MS

The Miriam Hospital/Brown Medical School Rena R. Wing, PhD1; Renee Bright, MS2; Vincent Pera, MD3; John Jakicic, PhD3; Deborah Tate, PhD3; Amy Gorin, PhD3; Kara Gallagher, PhD3; Amy Bach, PhD; Barbara Bancroft, RN, MS; Anna Bertorelli, MBA, RD; Richard Carey, BS; Tatum Charron, BS; Heather Chenot, MS; Kimberley Chula-Maguire, MS; Pamela Coward, MS, RD; Lisa Cronkite, BS; Julie Currin, MD; Maureen Daly, RN; Caitlin Egan, MS; Erica Ferguson, BS, RD; Linda Foss, MPH; Jennifer Gauvin, BS; Don Kieffer, PhD; Lauren Lessard, BS; Deborah Maier, MS; JP Massaro, BS; Tammy Monk, MS; Rob Nicholson, PhD; Erin Patterson, BS; Suzanne Phelan, PhD; Hollie Raynor, PhD, RD; Douglas Raynor, PhD; Natalie Robinson, MS, RD; Deborah Robles; Jane Tavares, BS

The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Steven M. Haffner, MD1; Maria G. Montez, RN, MSHP, CDE2; Carlos Lorenzo, MD3

University of Washington / VA Puget Sound Health Care System Steven Kahn MB, ChB1; Brenda Montgomery, RN, MS, CDE2; Robert Knopp, MD3; Edward Lipkin, MD3; Matthew L. Maciejewski, PhD3; Dace Trence, MD3; Terry Barrett, BS; Joli Bartell, BA; Diane Greenberg, PhD; Anne Murillo, BS; Betty Ann Richmond, MEd; April Thomas, MPH, RD

Southwestern American Indian Center, Phoenix, Arizona and Shiprock, New Mexico William C. Knowler, MD, DrPH1; Paula Bolin, RN, MC2; Tina Killean, BS2; Jonathan Krakoff, MD3; Jeffrey M. Curtis, MD, MPH3; Justin Glass, MD3; Sara Michaels, MD3; Peter H. Bennett, MB, FRCP3; Tina Morgan3; Shandiin Begay, MPH; Bernadita Fallis RN, RHIT, CCS; Jeanette Hermes, MS,RD; Diane F. Hollowbreast; Ruby Johnson; Cathy Manus LPN; Maria Meacham, BSN, RN, CDE; Julie Nelson, RD; Carol Percy, RN; Patricia Poorthunder; Sandra Sangster; Nancy Scurlock, MSN, ANP-C, CDE; Leigh A. Shovestull, RD, CDE; Janelia Smiley; Katie Toledo, MS, LPC; Christina Tomchee, BA; Darryl Tonemah, PhD

University of Southern California Anne Peters, MD1; Valerie Ruelas, MSW, LCSW2; Siran Ghazarian Sengardi, MD2; Kathryn Graves, MPH, RD, CDE; Kati Konersman, MA, RD, CDE; Sara Serafin-Dokhan

Coordinating Center

Wake Forest University Mark A. Espeland, PhD1; Judy L. Bahnson, BA2; Lynne Wagenknecht, DrPH3; David Reboussin, PhD3; W. Jack Rejeski, PhD3; Alain Bertoni, MD, MPH3; Wei Lang, PhD3; Gary Miller, PhD3; David Lefkowitz, MD3; Patrick S. Reynolds, MD3; Paul Ribisl, PhD3; Mara Vitolins, DrPH3; Michael Booth, MBA2; Kathy M. Dotson, BA2; Amelia Hodges, BA2; Carrie C. Williams, BS2; Jerry M. Barnes, MA; Patricia A. Feeney, MS; Jason Griffin, BS; Lea Harvin, BS; William Herman, MD, MPH; Patricia Hogan, MS; Sarah Jaramillo, MS; Mark King, BS; Kathy Lane, BS; Rebecca Neiberg, MS; Andrea Ruggiero, MS; Christian Speas, BS; Michael P. Walkup, MS; Karen Wall, AAS; Michelle Ward; Delia S. West, PhD; Terri Windham

Central Resources Centers

DXA Reading Center, University of California at San Francisco Michael Nevitt, PhD1; Susan Ewing, MS; Cynthia Hayashi; Jason Maeda, MPH; Lisa Palermo, MS, MA; Michaela Rahorst; Ann Schwartz, PhD; John Shepherd, PhD

Central Laboratory, Northwest Lipid Research Laboratories Santica M. Marcovina, PhD, ScD1; Greg Strylewicz, MS

ECG Reading Center, EPICARE, Wake Forest University School of Medicine RonaldJ. Prineas, MD, PhD1; Teresa Alexander; Lisa Billings; Charles Campbell, AAS, BS; Sharon Hall; Susan Hensley; Yabing Li, MD; Zhu-Ming Zhang, MD

Diet Assessment Center, University of South Carolina, Arnold School of Public Health, Center for Research in Nutrition and Health Disparities Elizabeth J Mayer-Davis, PhD1; Robert Moran, PhD

Hall-Foushee Communications, Inc Richard Foushee, PhD; Nancy J. Hall, MA

Federal Sponsors

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: Barbara Harrison, MS; Van S. Hubbard, MD PhD; Susan Z. Yanovski, MD

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Lawton S. Cooper, MD, MPH; Jeffrey Cutler, MD, MPH; Eva Obarzanek, PhD, MPH, RD

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Edward W. Gregg, PhD; David F. Williamson, PhD; Ping Zhang, PhD

Funding and Support

This study is supported by the Department of Health and Human Services through the following cooperative agreements from the National Institutes of Health: DK57136, DK57149, DK56990, DK57177, DK57171, DK57151, DK57182, DK57131, DK57002, DK57078, DK57154, DK57178, DK57219, DK57008, DK57135, and DK56992. The following federal agencies have contributed support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Nursing Research; National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities; Office of Research on Women’s Health; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Additional support was received from The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Bayview General Clinical Research Center (M01RR02719); the Massachusetts General Hospital Mallinckrodt General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01066); the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center General Clinical Research Center (M01RR00051) and Clinical Nutrition Research Unit (P30 DK48520); the University of Tennessee at Memphis General Clinical Research Center (M01RR0021140); the University of Pittsburgh General Clinical Research Center (M01RR000056 44) and NIH grant (DK 046204); and the University of Washington / VA Puget Sound Health Care System Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs; Frederic C. Bartter General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01346)

The following organizations have committed to make major contributions to Look AHEAD: Federal Express; Health Management Resources; Johnson & Johnson, LifeScan Inc.; Optifast-Novartis Nutrition; Roche Pharmaceuticals; Ross Product Division of Abbott Laboratories; and Slim-Fast Foods Company.

Footnotes

Principal Investigator

Program Coordinator

Co-Investigator

All other Look AHEAD staffs are listed alphabetically by site.

REFERENCES

- 1.The Look AHEAD Research Group. Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes): design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Cont Clin Trials. 2003;24:610–628. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Look AHEAD Research Group. Baseline characteristics of the randomized cohort from the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) Research Study. Diabetes Vasc Dis Res. 2006;3:202–215. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2006.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Look AHEAD Research Group. The Look AHEAD study: A description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity. 2006;14:737–752. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borg GA. Perceived exertion. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1974;2:131–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American College of Sports Medicine. Guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Philadelphia, PA: Williams and Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. NEJM. 2003;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): Description of the lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2165–2171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wing RR, Hamman RF, Bray GA, et al. the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Achieving weight and activity goals among Diabetes Prevention Program lifestyle participants. Obes Res. 2004;12:1426–1434. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NIH. NHLBI Clinical Guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. The Evidence Report. Obes Res. 1998;6:51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Look AHEAD Research Group. Manual of Operations. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Look AHEAD: Action for Health in Diabetes. Available at www.niddk.nih.gov/patient/SHOW/Look AHEAD.

- 11.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes. Diab Care. 2005;28:S4–S36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gregg EW, Cadwell BL, Cheng YJ, et al. Trends in the prevalence and ratio of diagnosed to undiagnosed diabetes according to obesity levels in the US. Diab Care. 2004;27:2806–2812. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, et al. the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Espeland MA, et al. Sodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of hypertension in older persons. A randomized controlled trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly (TONE) JAMA. 1998;279:839–846. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.11.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trials of Hypertension Prevention Collaborative Research Group. Trials of Hypertension Prevention. Phase II: Effects of weight loss and sodium reduction intervention on blood pressure and hypertension incidence in overweight people with high-normal blood pressure. Arch Int Med. 1997;157:657–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolf AM, Conaway MR, Crowther JQ, et al. Translating lifestyle intervention to practice in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Improving control with activity and nutrition (ICAN) study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1570–1576. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.7.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uusitupa MI. Early lifestyle intervention in patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance. Ann Med. 1996;28:445–449. doi: 10.3109/07853899608999106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guare JC, Wing RR, Grant A. Comparison of obese NIDDM and nondiabetic women: short- and long-term weight loss. Obes Res. 1995;3:329–335. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Looker HC, Knowler WC, Hanson RL. Changes in body mass index and weight before and after the development of type 2 diabetes. Diab Care. 2001;24:1917–1922. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.11.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeffrey RW, Wing RR, Thorson C, et al. Strengthening behavioral interventions for weight loss: a randomized trial of food provision and monetary incentives. J Consult Clin Psych. 1993;61:1038–1045. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeffery RW, Wing RR, Sherwood NE, Tate DF. Physical activity and weight loss: does prescribing higher physical activity goals improve outcome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:684–689. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.4.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ditschuneit HH, Flechtner-Mors M, Johnson TD, Adler G. Metabolic and weight-loss effects of a long-term dietary intervention in obese patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:198–204. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jakicic JM, Winters C, Lang W, Wing RR. Effects of intermittent exercise and use of home exercise equipment on adherence, weight loss, and fitness in overweight women. A randomized trial. JAMA. 1999;282:1554–1560. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heymsfield SB, van Mierlo CA, van der Knapp HC, et al. Weight management using a meal replacement strategy: meta- and pooling analysis from six studies. Int J Obes. 2003;27:537–549. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams KV, Mullen ML, Kelley DE, Wing RR. The effect of short periods of caloric restriction on weight loss and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Diab Care. 1998;21:2–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wing RR. Behavioral treatment of obesity: its application to type II diabetes. Diab Care. 1993;16:193–199. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker KZ, Piers LS, Putt RS, Jones JA, O’Dea K. Effects of regular walking on cardiovascular risk factors and body composition in normoglycemic women and women with type 2 diabetes. Diab Care. 1999;22:555–561. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodpaster BH, Katsiaras A, Kelley DE. Enhanced fat oxidation through physical activity is associated with improvements in insulin sensitivity in obesity. Diabetes. 2003;52:2191–2197. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.9.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jakicic JM, Marcus BH, Gallagher KI, Napolitano M, Lang W. Effect of exercise duration and intensity on weight loss in overweight, sedentary women. A randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1323–1330. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.10.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donnelly JE, Hill JO, Jacobsen DJ, et al. Effects of a 16-month randomized controlled exercise trial on body weight and composition in young, overweight men and women. Arch Int Med. 2003;163:1343–1350. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.11.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevens J, Cai J, Evenson KR, Thomas R. Fitness and fatness as predictors of mortality from all causes and from cardiovascular disease in men and women in the lipid research clinics study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;56:832–841. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee CD, Blair SN, Jackson AS. Cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, and all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:373–380. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei M, Gibbons LW, Kmpert JB, Nichaman MZ, Blair SN. Low cardiorespiratory fitness and physical inactivity as predictors of mortality in men with type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:605–611. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-8-200004180-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]