Abstract

Aim

Reductions in substance use were examined in response to an intensive intervention with people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (PLH).

Design, setting and participants

A randomized controlled trial was conducted with 936 PLH who had recently engaged in unprotected sexual risk acts recruited from four US cities: Milwaukee, San Francisco, New York and Los Angeles. Substance use was assessed as the number of days of use of 19 substances recently (over the last 90 days), evaluated at 5-month intervals over 25 months.

Intervention

A 15-session case management intervention was delivered to PLH in the intervention condition; the control condition received usual care.

Measurements

An intention-to-treat analysis was conducted examining reductions on multiple indices of recent substance use calculated as the number of days of use.

Findings

Reductions in recent substance use were significantly greater for intervention PLH compared to control PLH: alcohol and/or marijuana use, any substance use, hard drug use and a weighted index adjusting for seriousness of the drug. While the intervention-related reductions in substance use were larger among women than men, men also reduced their use. Compared to controls, gay and heterosexual men in the intervention reduced significantly their use of alcohol and marijuana, any substance, stimulants and the drug severity-weighted frequency of use index. Gay men also reduced their hard drug use significantly in the intervention compared to the control condition.

Conclusions

A case management intervention model, delivered individually, is likely to result in significant and sustained reductions in substance use among PLH.

Keywords: HIV, intervention studies, randomized controlled trial, substance abuse, unprotected sex

INTRODUCTION

Substance use is a key means of transmitting human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), both directly through sharing needles during injection drug use [1,2] and indirectly by disinhibiting risky sexual behavior [3–8]. One-third to half of people living with HIV (PLH) are likely to continue their transmission behaviors after learning their serostatus [4,8]. With the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) new initiative to prevent HIV transmission from PLH, reducing substance use is a key prevention strategy.

Globally, PLH face three challenges: reducing risky sexual acts and transmission, caring for their own health and maintaining positive mental health [9,10]. When the previous challenges are not met, substance use is related significantly to each of the resulting negative outcomes: unprotected sexual risk acts, non-adherence to health regimens and depression [11–15]. The Healthy Living Program was designed to reduce sexual risk acts. However, the project team also recognized that reducing and eliminating sexual risk required concomitant reductions in substance use. Substance use is a major trigger and disinhibitor of unprotected sex, as well as a barrier to implementing healthy daily routines and improving quality of life. The intervention program for sexual risk included a more comprehensive approach to implementing prevention.

Previous research has demonstrated repeatedly that cognitive–behavioral (CB) interventions are a good strategy for reducing use among substance abusers, which has been reported for adults [8,16], adolescents [17,18], stimulant users [19] and women [20]. We have demonstrated previously that attending a three-module CB intervention, delivered in a small group [10,11] or one-to-one format [21,22], reduced both substance use and sexual risk acts among young PLH. The current study, the Healthy Living Project, was adapted from the previous study of young PLH delivered in a one-to-one format in a three-module, CB intervention [21,22] and delivered to adult PLH. The advantage of a one-to-one intervention format is that it allowed case managers to tailor the intervention content to address the specific substances and the individual’s habitual patterns and triggers for using alcohol and drugs, as well as the links of substance use with sexual risk acts. For example, individuals abusing alcohol and those injecting drugs could attend the same Healthy Living Program. Furthermore, the one-to-one format made the intervention more accessible to the PLH by accommodating an individual’s schedule flexibly. The one-to-one format also reduced potential attendance barriers related to the stigma of attending a group session and thus being identified as being HIV+.

Similar to the earlier interventions [10,11,21,22], PLH were recruited from four metropolitan US cities and assessed repeatedly over 25 months. The Healthy Living Project consisted of three modules of five intervention sessions each: coping with stressors with a positive mental state, reducing transmission of HIV and improving health behaviors [23]. The intervention resulted in significant reductions in sexual risk behaviors over 25 months [24]. This paper examines changes in substance use in response to the intervention.

Because most PLH in the United States are polysubstance users [25], it was expected that the intervention would result in a harm reduction model. The great diversity in the specific drugs used and the frequency of use led us to examine multiple indices of drug use to determine intervention effects for multiple substances.

METHOD

Study participants

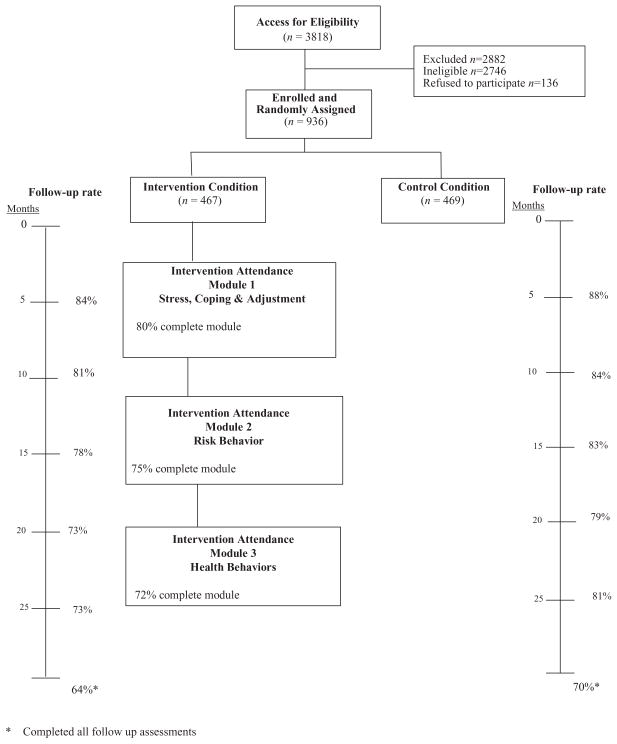

Figure 1 outlines the recruitment and flow of participants throughout the trial. A total of 3818 PLH were recruited from community agencies, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) service organizations and medical clinics in four cities (San Francisco, Los Angeles, NewYork City and Milwaukee) from April 2000 to January 2002. Recruitment strategies included advertisements as well as clinic- and site-based recruitment activities. Participants were required to be at least 18 years of age, speak English or Spanish, provide written informed consent, provide written medical documentation of their HIV-positive serostatus and not be involved currently in another behavioral intervention study related to HIV. In addition, participants were excluded if interviewers observed manifestations of neuropsychological impairment or psychosis, such as severe incoherence or obvious inability to comprehend interview questions. Eligibility for inclusion required that participants engage in at least one unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse act in the previous 3 months with HIV-negative or status unknown partners or with any casual sexual partners other than those in primary relationships.

Figure 1.

The flow of participants through each stage of the study

To determine eligibility, a 2-hour baseline interview was conducted. If the PLH reported at least one unprotected vaginal or anal sexual act recently (i.e. in the last 3 months), they were eligible for recruitment [21]. A total of 28.1% (n = 1072) were eligible. At the completion of this computerized baseline interview, the computer program determined eligible PLH and the interviewers then invited those eligible to participate in the intervention trial. Among the 1072 eligible PLH, 936 (87%) agreed to participate and were enrolled and randomized to the intervention (n = 467) or the control condition (n = 469). All randomized participants were included in this analysis. Among the eligible participants, 36% were from Los Angeles (n = 333), 26% were from New York City (n = 245), 29% were from San Francisco (n = 271) and 9% from Milwaukee (n = 87).

Procedure

All procedures and forms were reviewed and approved by the sites’ Institutional Review Boards, including a $50 incentive and $10 child care cost reimbursement per assessment. A highly trained assessment team (diverse in ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation) conducted interviews using laptop computers to record responses. To enhance veracity of self-reports of sensitive behaviors and attitudes, sensitive questions (i.e. sexual and substance use behavior) were delivered via audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) [26,27]. Quality assurance ratings for 20% of all interviews indicated satisfactory (≥ 90%) adherence to assessment protocols.

Participants were assessed at the baseline interview, as well as 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25 months later. Follow-up was high: 64% of intervention participants and 70% of controls completed all six follow-up assessments. Among the participants randomized to the intervention condition, follow-up rates were 83.7%, 81.2%, 77.5%, 73.4% and 73% in sequential follow-up interviews. Among participants in the control condition, the rates were 88.3%, 83.6%, 82.7%, 79.3% and 80.8% at the follow-up assessments. Follow-up was lower among the intervention than control group at 15 months (78% versus 83%; P = 0.03) and at 25 months (77% versus 81%; P = 0.01).

The mean age of the participants was 39.8 years (range 19–67); 55% were under the age of 40 years and 37% were between the ages of 30–40 years. Most participants were male (79%), of whom 72% were men who have sex with men (MSM). Participants’ age, gender and sexual orientation were similar across conditions.

About one-third of participants were white (32%), 45% were African American, 15% were Hispanic and 8% were of other ethnicities. Compared to the control condition, the intervention group had more African Americans (49% versus 40%) and fewer Latino/Hispanics (13% versus 17%; P = 0.033 for overall ethnicity differences).

Most PLH had not attended college (81%). About one-third were employed (36%), 43% had been convicted of a crime and 20% were uninsured. Participants had learned about their HIV status about 10 years previously; 69% received antiretroviral therapy and their mean CD4 was 425; 15% reported HIV-1 RNA of undetectable levels. There were no statistically significant differences between participants in the intervention and the control condition on these variables.

Depression, assessed on the Beck Depression Inventory [28,29], was similar across conditions [mean = 13.4, standard deviation (SD) = 9.1]. Quality of life indices measured on the Short Form 36 (SF-36) [30] were similar across conditions for the overall measure and for each subscale.

Participants reported a median of three sex partners in the past 3 months; 33% reported more than five partners. The number of recent unprotected sex acts (i.e. in the past 3 months) varied significantly across conditions at baseline, with more risk acts in the intervention condition compared to the control condition (mean of 21 versus 13, P = 0.009).

Substance use

Participants reported the frequency of recent use (i.e. over the last 90 days) for each of the following substances: alcohol, barbiturates, cocaine/crack, gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB), hallucinogens, heroin, inhalants, ketamine, marijuana, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), methadone, opiates, sedatives, speedball, steroids and stimulants (i.e. methamphetamine/amphetamine). For each substance, the frequency of recent use was reported as ‘never’ (scored as a ‘0’), ‘less than once a month’ (1), ‘once a month’ (3), ‘two to three times a month’ (7), ‘once a week’ (12), ‘two to three times a week’ (30), ‘four to six times a week’ (60), ‘once a day’ (90) or ‘more than once a day’ (120 selected as a conservative estimate of use). Because there were diverse patterns of use and polydrug use was common, we utilized multiple indices of substance use as our primary outcome. Five summary measures were calculated as the primary outcomes of substance use: (i) the sum of days on which alcohol and/or marijuana use was reported; (ii) the sum of days on which drugs other than marijuana (and alcohol) were used; (iii) the sum of days for which any substance use was reported; (iv) the sum of days for which any hard drug use was reported (heroin, cocaine, crack, speedball, MDMA); and (v) the sum of days in which any substance use was reported with the days weighted by substance severity [31] (0 for none; 1 for alcohol; 2 for marijuana; 3 for barbiturates, methadone, inhalants, sedatives and steroid; and 4 for cocaine, crack, GHB, hallucinogen, heroin, ketamine, speedball, MDMA, opiates and stimulants). Because of interest in epidemics of specific substances, we also examined the frequency of use of each substance as the total number of days of reported use recently (i.e. over the 3-month period) as secondary outcomes.

Similar to other samples, most PLH used alcohol and marijuana [32]. At the baseline, substance use appeared well balanced between the two conditions in terms of the percentage of participants who used and the number of days of individual substance use. There were no statistically significant differences at baseline between conditions on any substance assessed.

Randomization

Participants who met the eligibility criteria and agreed to participate were assigned to either the intervention or control condition according to a pre-determined sequence of simple random treatment assignment, which was accessed through a secure website on a computer server housed at the Los Angeles study site. The project staff at each site accessed the website using a unique log-on ID and password.

Intervention

The Healthy Living Project intervention is comprised of three modules, each consisting of five 90-minute individual counseling sessions [23]. A prevention case management approach was used for the implementation of the intervention [33] that entails screening, assessment, developing a plan to address deficits, monitoring progress over time and problem-solving challenges to implement safer sex practices consistently. A standard structure was used for each session: examining successes and problems that emerged in the previous week regarding coping with one’s HIV status, initiating assessment and problem solving in a new domain (e.g. identifying triggers to reduce substance use), practising implementation skills and setting a goal for the next week. Because this was a personalized intervention, the problem-solving activities were tailored during each session to the specific life context of the PLH and the stressors and challenges s/he experienced.

The challenges faced by PLH were addressed in three separate modules. Module 1 (coping) addresses ways to cope with internal affective states and problem situations in health behaviors, accessing health services and negotiating challenging interpersonal situations. Module 1 was completed by 80.3% of PLH, with a mean of 4.2 sessions. Module 2 (act safe) focuses on reducing transmission risk behaviors; 74.7% completed all module 2 sessions with a mean of 3.8 sessions. The relationship between substance use and sexual risk was addressed consistently in this module. Module 3 (stay healthy) focuses on maintaining optimal health care behaviors, including adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART), improving quality of life and achieving a meaningful life; 72.0% completed all sessions, with a mean of 3.6 sessions.

Sessions were typically audio-taped and rated on an ongoing basis for quality assurance. Adherence to session protocols by intervention facilitators was 95% for module 1, 86% for module 2 and 85% for module 3. There was less variability by module for competence in conducting specific session elements, with 97% of module 1 sessions and 96% each of module 2 and module 3 sessions rated as satisfactory.

Participants in the control condition were invited to the intervention following their 25-month follow-up interview.

Statistical analysis

Using an intention-to-treat analysis, we compared substance use reported between individuals in the intervention and control conditions using a generalized linear mixed-effects model (GLMM), assuming an underlying Poisson distribution for the substance use measures. Substance use was modeled for each participant as the linear slope over time assessed in weeks between the baseline and the 25-month follow-up time. The model included intervention status as a binary variable (0 for control, 1 for enhanced intervention) and an intervention condition × time interaction to allow for varying trajectories between the two conditions over time. Individual participant intercepts were treated as a normally distributed random effect. To test for differences in the measures of substance use between the intervention and control conditions over the baseline to 25-month interval, we evaluated the statistical significance of the intervention × time interaction using the t-test. We tested gender and sexual orientation as moderators of the intervention by adding two indicator variables to the models for being a MSM man or heterosexual man; women were the reference group. We also added two-way indicator × time interactions and three-way indicator × time by intervention status interactions to the models. Moderating effects were indicated by statistically significant three-way interactions. We plotted estimated mean substance use counts at each time-point, incorporating covariate and random-effect estimates similar to Duan’s method [34].

Proc NLMIXED [35] was used to obtain the maximum likelihood estimates of the generalized linear mixed-effects models, with one exception. PROC GLIMMIX was used to obtain pseudo-likelihood estimates on the weighted drug frequency when testing moderation effects.

RESULTS

Frequency of recent substance use and abuse

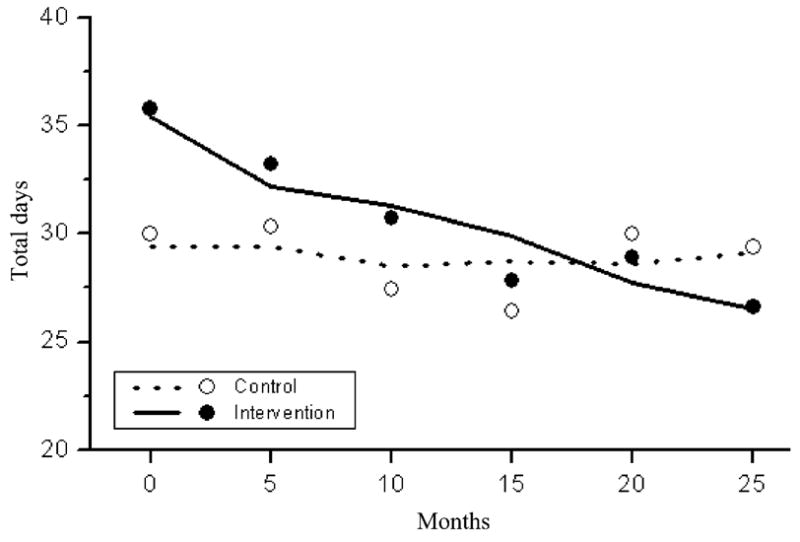

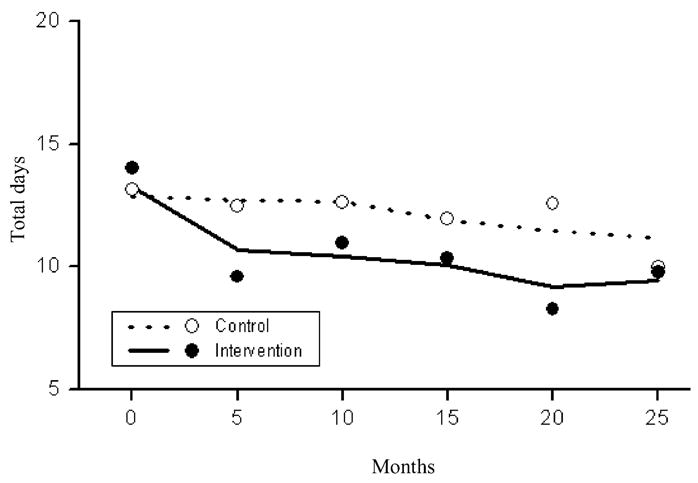

Figure 2 shows the results of the mixed model analysis charting the expected and actual changes over time for each intervention condition on the total number of days of alcohol and/or marijuana use. The fit of the model appears to be good. While use was similar across conditions at recruitment, there were significant differences based on intervention condition over time (t = −15.4, df = 935, P <0.0001), with a reduction in alcohol/marijuana use over time in the intervention condition, but little change over time in the control condition.

Figure 2.

Estimated (lines) and raw (dots) mean counts of the total number of days using marijuana or alcohol in the last 90 days

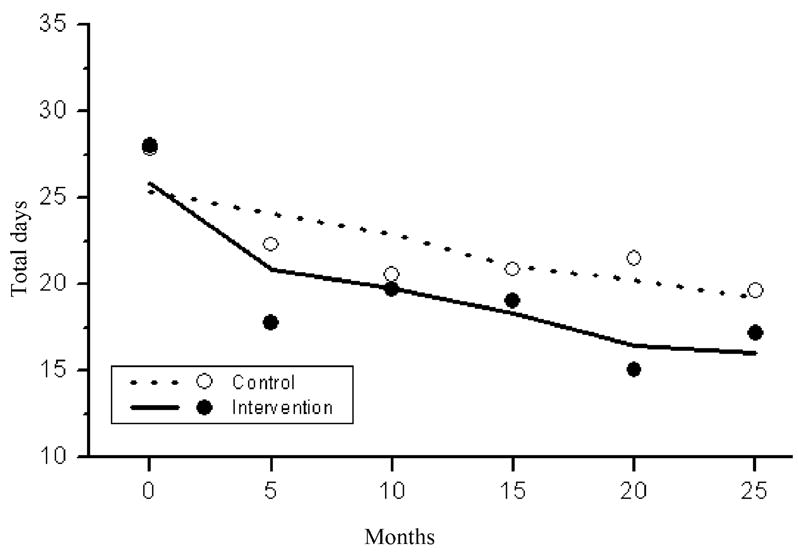

Figure 3 shows that there was a significantly greater reduction over time in use of substances other than marijuana or alcohol in the intervention compared to control condition (t = −8.4, df = 935, P <0.0001). Control PLH had statistically significant reductions in their recent drug use over time; however, the reductions were greater (and statistically significant) in the intervention condition.

Figure 3.

Estimated (lines) and raw (dots) mean counts of the total number of days using drugs other than marijuana (and alcohol) in the last 90 days

The plot in Fig. 4 shows a significantly greater reduction in the number of days of use of any substance in the intervention condition compared to the control condition over time (t = −16.6, df = 935, P <0.0001).

Figure 4.

Estimated (lines) and raw (dots) mean counts of the total number of days using any substance (alcohol or any drug) in the last 90 days

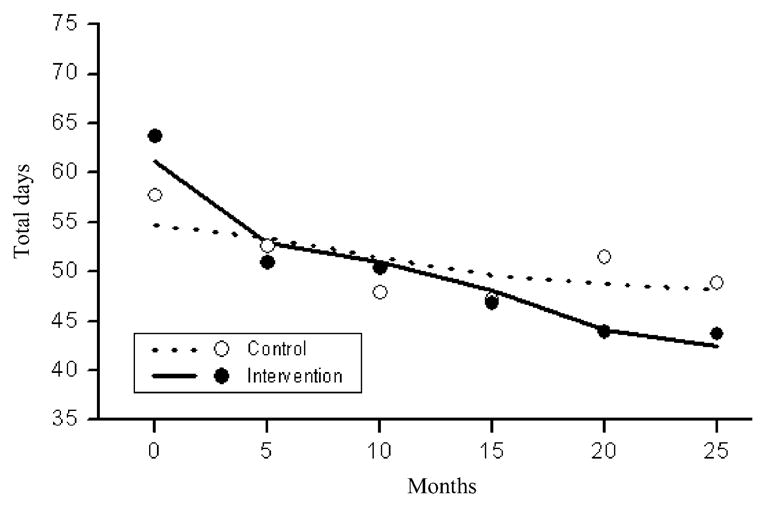

Figure 5 shows a significantly greater reduction in the number of recent days of hard drug use (i.e. heroin, cocaine, crack, speedball, MDMA) for PLH in the intervention condition compared to the control condition over time (t = −7.1, df = 935, P <0.0001).

Figure 5.

Estimated (lines) and raw (dots) mean counts of the total number of days using hard drugs in the last 90 days

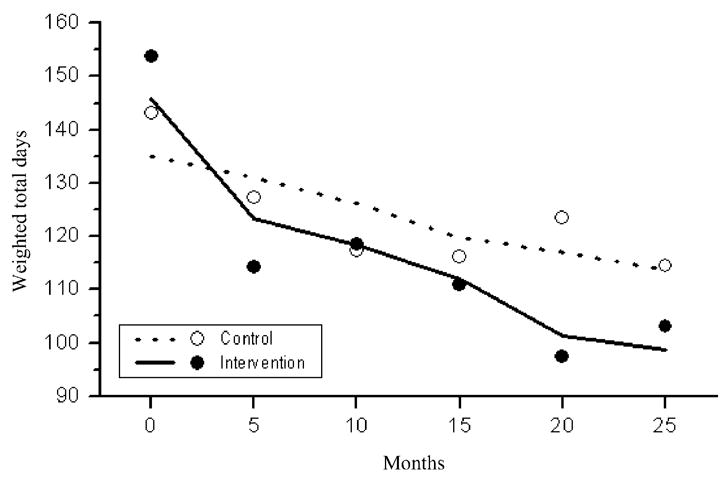

Figure 6 shows that there were significantly greater reductions in the severity weighted substance use frequency index in the intervention compared to control condition over time (t = −23.2, df = 935, P <0.0001).

Figure 6.

Estimated (lines) and raw (dots) weighted means based on calculating the frequency of substance use by the seriousness of substance, over the 90 days

Compared to PLH in the control condition, intervention PLH showed greater reductions in the number of days of substance use for each of the following: alcohol, marijuana, methadone, inhalants, MDMA, stimulants (i.e. methamphetamine/amphetamine), sedatives, barbiturates and steroids. However, no statistically significant intervention effect differences were found for heroin, opiates, cocaine, crack, ketamine, GHB or hallucinogen.

The impact of moderator variables: gender and sexual orientation

Because of the interest in methamphetamine use we examined reductions among MSM specifically, a subgroup that has been identified as having high rates of methamphetamine use [15]. Intervention effects on each of the five main substance use outcome indices differed between women, MSM and heterosexual men (F = 89.67 to 509.93, df = 2935, each P <0.0001). Average decreases in the number of days using in the intervention group compared to the control group were greater for women compared to MSM (t = −11.28 to −19.21, df = 935, all P <0.0001 for the first four substance indices; t = 31.8, df = 935, P <0.0001 for weighted drug frequency) and for heterosexual men compared to MSM (t = −8.07 to −13.04, df = 935, all P <0.0001 for the first four substance indices; t = 21.18, df = 935, P <0.0001 for weighted drug frequency).

Among men, there were statistically significant reductions in four of the five summary substance use indices and stimulants. Both MSM and heterosexual men reduced significantly their overall substance use, alcohol and marijuana use, methamphetamine/stimulant use and the weighted drug index. Reductions in these drugs were similar for both MSM and heterosexual men except for the weighted drug index (t935 = 3.87, P <0.0001). Neither MSM nor heterosexual men reported statistically significant reductions on the index of drug use that excluded marijuana (and alcohol). Hard drug use was reduced significantly among MSM (t935 = −2.02, P <0.04), with significantly greater reductions than among heterosexual men (t935 = 3.69, P = 0.0002). Intervention effects for the number of days using stimulants differed between heterosexual and MSM (t = −11.37, df = 935, P <0.0001). While both MSM and heterosexual men decreased their use of stimulants significantly, there were significantly greater decreases in the number of days using stimulants reported by the heterosexual men in the intervention condition compared to the heterosexual men in the control condition (t = −11.98, df = 935, P <0.0001) than a similar comparison with the MSM (t = −2.21, df = 935, P = 0.03). Women also decreased stimulant use for significantly more days than MSM (F = 78.9; df = 2035, P <0.0001).

DISCUSSION

Being a PLH creates predictable challenges for adults: staying healthy, stopping sexual transmission acts and coping with HIV-related stressors such as stigma, discrimination and making serostatus disclosures [36]. The Healthy Living Project was designed to reduce transmission acts, recognizing that changes in sexual behaviors require more comprehensive changes within a person’s life. If the PLH’s motivations for self-preservation and quality of life are not activated, it is unlikely that the PLH will reduce his or her transmission acts altruistically with HIV-negative partners [18]. Previously, we have demonstrated that this comprehensive prevention approach, delivered over three modules, results in decreases in sexual transmission acts, particularly to HIV-negative partners or partners of unknown serostatus [10,11,21,22,24]. These analyses demonstrate that the comprehensive approach also benefits the PLH by substantially and significantly reducing their substance use. Relative to the control condition, the Healthy Living Program reduced effectively PLH’s substance use for alcohol, marijuana and hard drugs. The reductions were sustained for at least 25 months.

It is noteworthy that the intervention does not focus specifically on substance use. The first five-session module of the intervention, for example, focuses on helping participants learn to cope with stressors associated with being HIV-positive and expanding their social support network. This module includes detailed training in coping skills, using an adaptation of Chesney & Folkman’s Coping Effectiveness Training [37]. We hypothesized that general stress management and problem-solving training would, in turn, help PLH to make more mindful decisions about their sexual behavior. Increased coping skills may also impact substance use, as well as sexual risk. Also, the intervention was designed to be flexible in order to tailor it to the needs of the individual PLH. Thus, PLH who identified substance use as a problem in their lives were encouraged to apply problem-solving techniques to reduce use.

The intervention reduced hard drug use (i.e. heroin, cocaine, crack, speedball, MDMA), as well as alcohol and marijuana use. When examined as individual substances (as opposed to a ‘hard drug’ category), there were significant reductions in methamphetamine/stimulant use, key drugs that reinforce sexual risk behaviors [38]. In particular, methamphetamine use among MSM has been linked to rising HIV incidence in West Coast AIDS epicenters within the United States [39]. This is one of the first studies to demonstrate reductions in stimulant use in response to a psychosocial intervention.

We did not find statistically significant intervention effects for some of the drugs classed as ‘more serious’ on our weighted index: crack, cocaine, heroin, opiates and hallucinogens. Because fewer PLH utilize hard drugs (e.g. only 8% used hard drugs daily), while almost all PLH reported either alcohol or drug use, it may be harder to detect an intervention effect. However, PLH with comorbid opiate and cocaine dependency are likely to require specialized treatment to reduce or discontinue using. Our intervention, focusing on coping effectiveness and healthy relationships, created opportunities for referrals for such treatment and may help set the stage for more successful outcomes among hard drug users.

It is noteworthy that there were statistically significant differences in intervention effects based on gender and sexual orientation: women demonstrated the greatest reductions in substance use. MSM and heterosexual men also demonstrated reductions in substance use, but the reductions were not as great as among women. In particular, the reductions in stimulant use in the intervention condition were greater among heterosexual men than MSM. However, there were statistically significant reductions in hard drug use among MSM that were not observed among heterosexual men, and there is little relapse over time. These results are in contrast to the EXPLORE intervention study with seronegative MSM [40], suggesting that being seropositive is a strong motivator that enhances responsiveness to interventions

This study has several limitations. First, PLH self-reported their substance use. However, similar to other research [25], reporting biases were minimized by using audio computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) for the substance use reports. Furthermore, the validity of self-reports in prior studies among young PLH were high for all substances except cocaine use and crack [21]. Secondly, the interventions consisted of multiple components delivered in three modules. We can make no definitive claims about the effects of specific intervention elements on substance use. However, when the components of the comprehensive approach were combined, significant reductions in substance use occurred. Finally, although our sample was large and diverse, it was not recruited to be a representative sample. Our sample is, however, very similar to the socio-demographic profile of PLH in the United States reported to the CDC.

The Healthy Living intervention results in significant reductions in substance use, and was shown previously to produce significant reductions in sexual transmission risk acts [24]. Reductions in substance use may be a secondary benefit of this intervention but also may contribute directly to reductions in transmission risk.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by cooperative agreements between the United States National Institute of Mental Health and the University of California, Los Angeles (U10MH057615); New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University (U10MH057636); the Medical College of Wisconsin (U10MH057631); and the University of California, San Francisco (U10MH057616).

Footnotes

THE NIMH HEALTHY LIVING TRIAL GROUP

Research Steering Committee (site principal investigators and NIMH staff collaborators): Margaret A. Chesney1, Anke A. Ehrhardt2, Jeffrey A. Kelly3, Willo Pequegnat4, Mary Jane Rotheram-Borus5.

Collaborating Scientists, Co-Principal Investigators, and Investigators: Abdelmonem A. Afifi5, Eric G. Benotsch3, Michael J. Brondino3, Sheryl L. Catz3, Edwin D. Charlebois1, W. Scott Comulada5, William G. Cumberland5, Don C. Des Jarlais6, Naihua Duan5, Theresa M. Exner2, Rise B. Goldstein5, Cheryl Gore-Felton3, A. Elizabeth Hirky2, Mallory O. Johnson1, Robert M. Kertzner2, Sheri B. Kirshenbaum2, Lauren E. Kittel2, Robert Klitzman2, Martha Lee5, Bruce Levin 2, Marguerita Lightfoot5, Stephen F. Morin1, Steven D. Pinkerton3, Robert H. Remien2, Fen Rhodes5, Juwon Song5, Wayne T. Steward1, Susan Tross2, Lance S. Wein-hardt3, Robert Weiss5, Hannah Wolfe7, Rachel Wolfe7, F. Lennie Wong5.

Data Management and Analytical Support: Philip Batterham5, W. Scott Comulada5, Tyson Rogers5, Yu Zhao5.

Site Project Coordinators: Jackie Correale2, Kristin Hackl3, Daniel Hong5, Karen Huchting5, Joanne D. Mickalian1, Margaret Peterson3.

University of California, San Francisco1, New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University, New York2, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee3, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Maryland4, University of California, Los Angeles5, Beth Israel Medical Center, New York6 and St Luke’s–Roosevelt Medical Center, New York7.

References

- 1.CDC. Trends in HIV-related risk behaviors among high school students—United States 1991–2005. MMWR. 2006;55:851–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehta SH, Galai N, Astemborski J, Celentano DD, Strathdee SA, Vlahov D, et al. HIV incidence among injection drug users in Baltimore, Maryland (1988–2004) J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:368–72. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243050.27580.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halkitis PN, Shrem MT, Martin FW. Sexual behavior patterns of methamphetamine-using gay and bisexual men. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40:703–19. doi: 10.1081/ja-200055393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crepaz N, Marks G. Towards an understanding of sexual risk behavior in people living with HIV: a review of social, psychological, and medical findings. AIDS. 2002;16:135–49. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200201250-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drumright LN, Little SJ, Strathdee SA, Slymen DJ, Araneta MR, Malcarne VL, et al. Unprotected anal intercourse and substance use among men who have sex with men with recent HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:344–50. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000230530.02212.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayaki J, Anderson B, Stein M. Sexual risk behaviors among substance users: relationship to impulsivity. Psychol Addict Behav. 2006;20:328–32. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins PY, Holman AR, Freeman MC, Patel V. What is the relevance of mental health to HIV/AIDS care and treatment programs in developing countries? A systematic review. AIDS. 2006;20:1571–82. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000238402.70379.d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Semaan S, Des Jarlais DC, Sogolow E, Johnson WD, Hedges LV, Ramirez GS, et al. Meta-analysis of the effect of HIV prevention interventions on the sex behaviors of drug users in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30:S73–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson B, Carey MP, Chaudoir SR, Reid AE, Johnson B, Carey MP, et al. Sexual risk reduction for persons living with HIV: research synthesis of randomized controlled trials, 1993–2004. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:642–50. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000194495.15309.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lee MB, Murphy DA, Futterman D, Duan N, Birnbaum JM, et al. Efficacy of a preventive intervention for youth living with HIV. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:400–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Murphy DA, Wight RG, Lee MB, Lightfoot M, Swendeman D, et al. Improving the quality of life among young people living with HIV. Eval Program Plan. 2001;24:227–37. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook RL, Sereika SM, Hunt SC, Woodward WC, Erlen JA, Conigliaro J. Problem drinking and medication adherence among persons with HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:83–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Treisman G, Fishman M, Schwartz J, Hutton H, Lyketsos C. Mood disorders in HIV infection. Depress Anxiety. 1998;7:178–87. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1998)7:4<178::aid-da6>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwiatkowski CF, Booth RE. HIV seropositive drug users and unprotected sex. AIDS Behav. 1998;2:151–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shoptaw S, Peck J, Reback CJ, Rotheram-Fuller E. Psychiatric and substance dependence comorbidities, sexually transmitted diseases, and risk behaviors among methamphetamine-dependent gay and bisexual men seeking outpatient drug abuse treatment. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35:161–8. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10400511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cophenhaver M, Johnson BT, Lee I-C, Harman JJ, Carey MP the SHARP Research Group. Behavioral HIV risk reduction among people who inject drugs: meta-analytic evidence of efficacy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31:163–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Koopman C, Haignere C, Davies M. Reducing HIV sexual risk behaviors among runaway adolescents. JAMA. 1991;266:1237–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Miller S. Secondary prevention for youths living with HIV. AIDS Care. 1998;10:17–34. doi: 10.1080/713612347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rawson RA, McCann MJ, Flammino F, Shoptaw S, Miotto K, Reiber C, et al. A comparison of contingency management and cognitive–behavioral approaches for stimulant-dependent individuals. Addiction. 2006;101:267–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen LR, Hien DA. Treatment outcomes for women with substance abuse and PTSD who have experienced complex trauma. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:100–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Comulada WS, Weiss RE, Cumberland W, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Reductions in drug use among young people living with HIV. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33:493–501. doi: 10.1080/00952990701301921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Comulada WS, Weiss RE, Lee M, Lightfoot M. Prevention for substance-using HIV-positive young people: telephone and in-person delivery. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37:S68–77. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000140604.57478.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gore-Felton C, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Weinhardt LS, Kelly JA, Lightfoot M, Kirshenbaum SB, et al. The Healthy Living Project: an individually tailored, multidimensional intervention for HIV-infected persons. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17:21–39. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.2.21.58691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Healthy Living Project Team. Effects of a behavioral intervention to reduce risk of transmission among people living with HIV: the Healthy Living Project randomized controlled study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:213–21. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802c0cae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sohler NL, Wong MD, Cunningham WE, Cabral H, Drainoni M-L, Cunningham CO. Type and pattern of illicit drug use and access to health care services for HIV-infected people. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2007;21:S-68–76. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–73. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gribble JN, Miller HG, Rogers SM, Turner CF. Interview mode and measurement of sexual behaviors: methodological issues. J Sex Res. 1999;36:16–24. doi: 10.1080/00224499909551963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck AT. Depression: Causes and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF 36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A User’s Manual. Boston MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kandel DB. Stages in adolescent involvement in drug use. Science. 1975;190:912–14. doi: 10.1126/science.1188374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Luna GC, Marotta T, Kelly H. Going nowhere fast: methamphetamine use and HIV infection. In: Battjes R, Sloboda Z, Grace WC, editors. The Context of HIV Risk among Drug Users and Their Sexual Partners, Monograph Series no. 143. Washington, DC: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1994. pp. 155–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CRCS Implementation Manual. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control; 2006. [accessed 23 October 2007]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/prev_prog/CRCS/resources/CRCS_Manual/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duan N. Smearing estimate: a nonparametric retransformation method. J Am Stat Assoc. 1983;78:605–10. [Google Scholar]

- 35.SAS. SAS/STAT® User’s Guide, version 9.1. 8. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lightfoot M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Milburn NG, Swendeman D. Prevention for HIV-seropositive persons: successive approximation toward a new identity. Behav Modif. 2005;29:227–55. doi: 10.1177/0145445504272599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chesney MA, Folkman S. Psychological impact of HIV disease and implications for intervention. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1994;17:163–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shoptaw S, Reback CJ, Peck JA, Yang X, Rotheram-Fuller E, Larkins S, et al. Behavioral treatment approaches for methamphetamine dependence and HIV-related sexual risk behaviors among urban gay and bisexual men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;78:125–34. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shoptaw S, Reback CJ. Associations between methamphetamine use and HIV among men who have sex with men: a model for guiding public policy. J Urban Health. 2006;83:1151–7. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9119-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koblin B, Chesney M, Coates T. EXPLORE Study Team: effects of a behavioural intervention to reduce acquisition of HIV infection among men who have sex with men: the EXPLORE randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2004;364:41–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16588-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]