Abstract

Chaperone-mediated autophagy controls the degradation of selective cytosolic proteins and may protect neurons against degeneration. In a neuronal cell line, we found that chaperone-mediated autophagy regulated the activity of myocyte enhancer factor 2D (MEF2D), a transcription factor required for neuronal survival. MEF2D was observed to continuously shuttle to the cytoplasm, interact with the chaperone Hsc70, and undergo degradation. Inhibition of chaperone-mediated autophagy caused accumulation of inactive MEF2D in the cytoplasm. MEF2D levels were increased in the brains of α-synuclein transgenic mice and patients with Parkinson’s disease. Wild-type α-synuclein and a Parkinson’s disease–associated mutant disrupted the MEF2D-Hsc70 binding and led to neuronal death. Thus, chaperone-mediated autophagy modulates the neuronal survival machinery, and dysregulation of this pathway is associated with Parkinson’s disease.

In neurodegenerative diseases, certain populations of adult neurons are gradually lost because of toxic stress. The four myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) transcription factors, MEF2A to MEF2D, have been shown to play an important role in the survival of several types of neurons, and a genetic polymorphism of the MEF2A gene has been linked to the risk of late onset of Alzheimer’s disease (1–3). In cellular models, inhibition of MEF2s contributes to neuronal death. Enhancing MEF2 activity protects neurons from death in vitro and in the substantia nigra pars compacta in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease (PD) (4). Neurotoxic insults cause MEF2 degradation in part by a caspase-dependent mechanism (5), but how MEF2 is regulated under basal conditions without overt toxicity is unknown. Autophagy refers to the degradation of intracellular components by lysosomes. Relative to macro- and microautophagy, chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) selectively degrades cytosolic proteins (6). This process involves binding of heat shock protein Hsc70 to substrate proteins via a KFERQ-like motif and their subsequent targeting to lysosomes via the lysosomal membrane receptor Lamp2a. Dysregulation of autophagy plays a role in neurodegeneration (7–9). However, the direct mechanism by which CMA modulates neuronal survival or death is unclear.

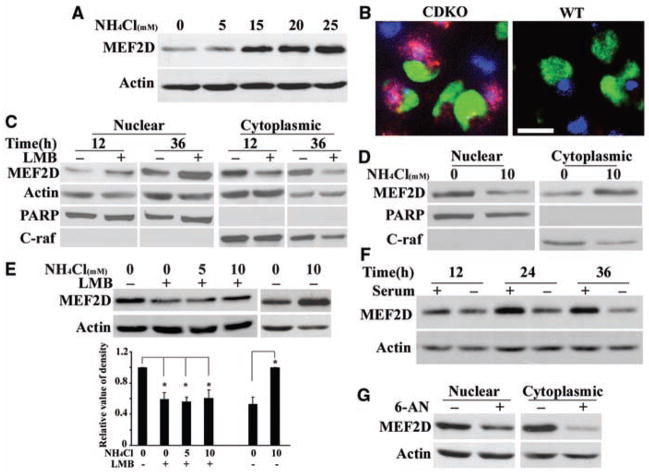

Because the level of MEF2 protein is critical to neuronal survival (5), we investigated the role of autophagy in the degradation of MEF2D protein by blocking lysosomal proteolysis with ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) in a mouse midbrain dopaminergic progenitor cell line, SN4741 (10). NH4Cl caused a dose-dependent increase in the level of MEF2D (Fig. 1A). Exposing primary cortical and cerebellar granule neurons to NH4Cl also resulted in accumulation of MEF2D (fig. S1). In mice lacking the lysosomal hydrolase cathepsin D (11), MEF2D levels were increased in the substantia nigra and cortex (Fig. 1B and fig. S1). Thus, the lysosomal system controls MEF2D levels in neurons. The SN4741 neuronal cell line is useful for studying the neuronal stress response (12) and so was used as the primary model for the rest of the study.

Fig. 1.

Degradation of MEF2D by an autophagy pathway. (A) Inhibition of MEF2D degradation by blocking autophagy. NH4Cl causes MEF2D accumulation in SN4741 cells. (B) Increased MEF2D immunoreactivity in substantia nigra in brains of cathepsin D–deficient (CDKO) versus wild-type (WT) mice. Green, tyrosine hydroxylase; red, MEF2D; blue, 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Translocation of MEF2D to the cytoplasm. LMB (50 ng/ml) caused accumulation of MEF2D in the nucleus (n = 4 independent experiments). (D) Increased cytoplasmic MEF2D induced by NH4Cl accompanies the reduction of nuclear MEF2D (n = 3). (E) Reduction of NH4Cl-induced accumulation of MEF2D in the cytoplasm by LMB (n = 3, *P < 0.05). (F) Degradation of cytoplasmic MEF2D by serum deprivation (n = 3). (G) Effect of CMA on MEF2D degradation. Levels of cytoplasmic MEF2D from SN4741 cells treated with 6-AN (5 mM, 24 hours) were determined by immunoblotting (n = 4).

Lysosomes regulate substrate proteins in the cytoplasmic compartment (6), but MEF2D has been reported only in the neuronal nucleus (6). Our findings suggested translocation of MEF2D to the cytoplasm for direct modulation by autophagy. To test this idea, we fractionated SN4741 cells and found a fraction of MEF2D present in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1C) under normal conditions. Leptomycin B (LMB), a specific inhibitor of receptor CRM-1–dependent nuclear export, reduced the level of cytoplasmic MEF2D while concomitantly increasing nuclear MEF2D (Fig. 1C). Inhibition of lysosomal function consistently reduced nuclear MEF2D but caused its concurrent accumulation in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1D). LMB attenuated the NH4Cl-induced accumulation of MEF2D in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1E), which suggests that MEF2D is constantly exported to the cytoplasm under basal conditions for lysosomal degradation. To study the degradation of MEF2D by autophagy, we activated CMA by serum removal (13, 14), which led to a marked reduction in MEF2D levels and metabolically labeled MEF2D (Fig. 1F and fig. S2A). No change was detected in the levels of mef2d transcript after serum withdrawal (fig. S2B). Similarly, when CMA was stimulated with 6-aminonicotinamide (6-AN) (15), MEF2D levels were reduced (Fig. 1G). In contrast, the macroautophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine had only a small effect on MEF2D levels (fig. S3) (16). Thus, our results support CMA as the major mode of autophagy that controls MEF2D degradation.

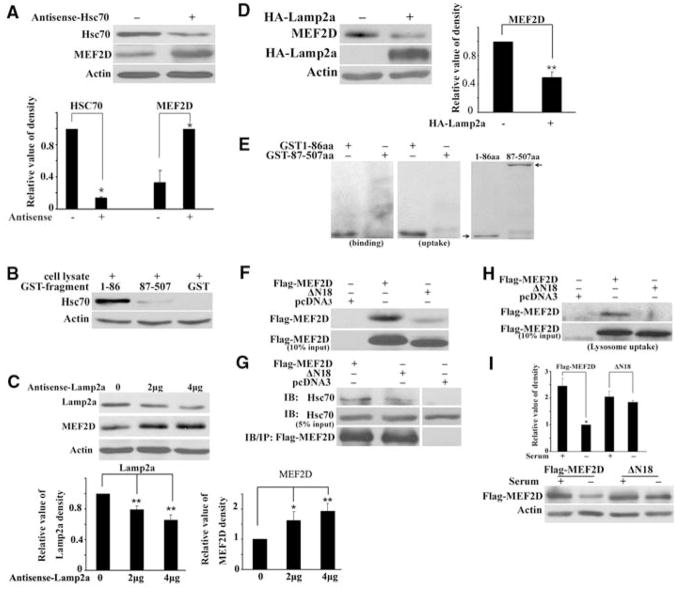

The CMA pathway involves two key regulators, Hsc70 and Lamp2a. Reducing the level of Hsc70 by overexpression of antisense RNA in SN4741 cells increased MEF2D levels (Fig. 2A). To probe the interaction between MEF2D and Hsc70, we incubated N- and C-terminal fragments of purified GST-MEF2D (glutathione S-transferase fused to MEF2D) with cellular lysates and then performed immunoblotting to detect bound Hsc70. Hsc70 interacted with GST-MEF2D (amino acid residues 1 to 86; MEF2D 1-86), but not with the C terminus (residues 87 to 507) of MEF2D or with GST alone (Fig. 2B). Reducing Lamp2a protein by overexpression of antisense RNA also increased MEF2D levels (Fig. 2C). Conversely, overexpression of Lamp2a markedly reduced MEF2D levels (Fig. 2D). To show that lysosomes directly regulate MEF2D, we performed lysosomal binding and uptake assays. Purified lysosomes isolated from rat liver (13) readily took up purified CMA substrate ribonuclease A (fig. S4), confirming the integrity of our lysosomal preparations. GST-MEF2D fragments were incubated with lysosomes and detected by anti-GST immunoblotting. MEF2D 1-86 readily bound to lysosomes (Fig. 2E). For uptake studies, we incubated lysosomes and substrates in the presence of hydrolase inhibitors, digested proteins outside of lysosomes with proteinase K, and showed that MEF2D 1-86 was present inside lysosomes (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Interactions of MEF2D with key CMA regulators. (A) Effect of reducing Hsc70 on MEF2D. The level of cytoplasmic MEF2D in SN4741 cells was determined after transfection of control plasmid or plasmid encoding antisense Hsc70 (36 hours) (n = 3, *P < 0.05). (B) Interaction of N-terminal MEF2D with Hsc70. GST pull-down assay was carried out by incubating GST or GST-MEF2D fragments with cell lysates. Bound Hsc70 was detected by immunoblotting. (C) Effect of reducing Lamp2a on MEF2D. The experiments were carried out as described in (A) with plasmid encoding antisense Lamp2a (n = 4; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). (D) Effect of increasing Lamp2a on MEF2D. The experiment was carried out as described in (C) with plasmid encoding Lamp2a (n = 3, **P < 0.01). HA, hemagglutinin. (E) Lysosomal binding and uptake of MEF2D. The presence of purified GST-MEF2D fusion proteins was determined after incubation with purified lysosomes by anti-GST immunoblotting (right panel shows the positions of GST-MEF2D proteins by Coomassie stain; n = 4). (F and G) Effect of deleting the N-terminal 18 amino acid residues on MEF2D binding to Hsc70. Wild-type and mutated (ΔN18) MEF2D expressed in HEK293 cells was detected by GST-Hsc70 pull-down assay (n = 3) (F) or by coimmunoprecipitation (G). (H) Uptake of MEF2DΔN18 by lysosomes. The assay was carried out as described in (E) with the use of lysates containing overexpressed MEF2D. (I) Degradation of MEF2DΔN18 by serum deprivation. SN4741 cells transfected with indicated plasmids were assayed as described in Fig. 1F (n = 3, *P < 0.05).

Hsc70 interacts with a conserved KFERQ-like motif in substrate proteins (17). Analysis of the N terminus of MEF2D revealed the presence of several imperfect CMA recognition sequences (fig. S5). We tested whether they may serve as Hsc70 interacting sequences by incubating purified GST-Hsc70 with cellular lysates containing overexpressed Flag-MEF2D. Mutation of these motifs individually did not disrupt the binding between MEF2D and GST-Hsc70, as exemplified by mutant QR10-11 (fig. S5). Deletion of the 18 amino acids expanding several overlapping motifs (Flag-MEF2DΔN18) abolished its binding to GST-Hsc70 (Fig. 2F) or to endogenous Hsc70 (Fig. 2G). Moreover, MEF2DΔN18 was poorly taken up by lysosomes (Fig. 2H), and its level was not significantly reduced by serum deprivation (Fig. 2I). Thus, multiple motifs at the MEF2D N terminus mediate its interaction with Hsc70 and degradation by CMA.

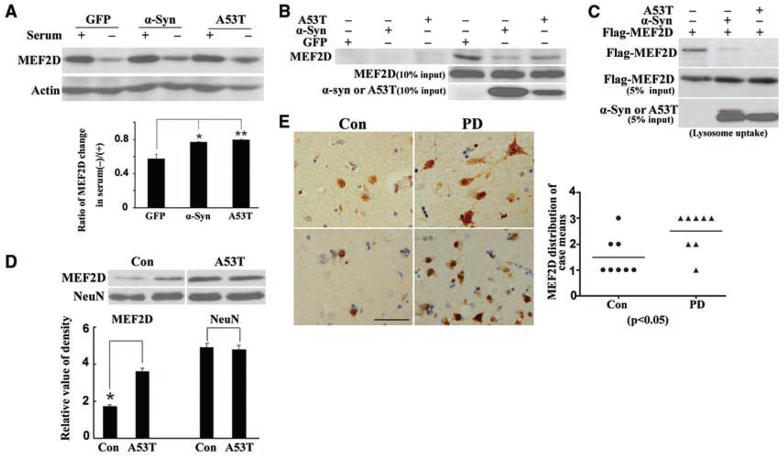

We determined the effect of α-synuclein, itself a CMA substrate and PD risk factor (18, 19), on MEF2D in SN4741 cells. Both wild-type and disease-causing mutant α-synuclein (Ala53 → Thr, A53T) attenuated degradation of MEF2D that had been induced by serum deprivation and 6-NA (Fig. 3A and fig. S6A). Furthermore, overexpression of wild-type α-synuclein or the A53T mutant reduced the interaction of endogenous MEF2D and GST-Hsc70 in a pull-down assay (Fig. 3B) and the binding of Flag-MEF2D to endogenous Hsc70 in coprecipitation experiments (fig. S6B). Increasing the level of wild-type or A53T α-synuclein inhibited the uptake of MEF2D by lysosomes (Fig. 3C). Moreover, cytoplasmic MEF2D levels in the cortex of A53T α-synuclein transgenic mice (20) were significantly higher than in wild-type control mice (Fig. 3D). MEF2D levels were significantly higher in the brains of PD patients than in controls (Fig. 3E) with a substantial portion of MEF2D in neuronal cytoplasm, correlating with high levels of α-synuclein in the brains of PD patients (fig. S7).

Fig. 3.

Effect of α-synuclein on CMA-mediated degradation of MEF2D. (A) Inhibition of CMA-mediated degradation of MEF2D by α-synuclein. SN4741 cells transfected with indicated plasmids were assayed as described in Fig. 2I (n = 4; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). (B) Inhibition of binding of endogenous MEF2D to GST-Hsc70 by α-synuclein. The experiments were carried out as described in Fig. 2F after expression of α-synuclein in SN4741 cells (n = 3). (C) Inhibition of lysosomal uptake of MEF2D by α-synuclein. Lysates of HEK293 cells transfected with indicated plasmids were tested in lysosomal uptake assay as described in Fig. 2E (n = 3). (D) MEF2D levels in the cortex of A53T α-synuclein transgenic mice (A53T) were compared to that of wild-type nontransgenic mice (Con) (n = 3, *P < 0.05). (E) MEF2D levels determined by immunohistochemistry in striatum of control (Con) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients (scale bar, 50 μm). Graph depicts the relative levels of staining in cases tested.

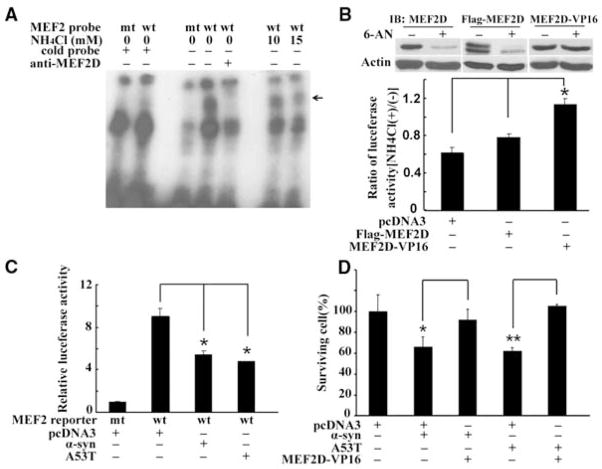

To assess whether the accumulated MEF2D is functional, we determined MEF2D DNA binding activity by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). For this study, we treated cells with NH4Cl, confirmed the increase of MEF2D (fig. S8A), and incubated lysates with a labeled MEF2 DNA probe. MEF2D in the control cell lysates bound specifically to the DNA probe. The accumulated MEF2D in NH4Cl-treated samples or resulting from a reduction of Hsc70 bound to the DNA probe at a far lower rate than did controls (Fig. 4A and fig. S8B). Phosphatase treatment did not affect MEF2D DNA binding (fig. S8, B and C) (21). NH4Cl markedly reduced MEF2-dependent reporter activity in SN4741 cells (fig. S9). To test whether maintaining MEF2D in the nucleus might preserve its function, we showed that the nuclear level of MEF2D-VP16, a fusion protein lacking the putative nuclear export signals at the C terminus of MEF2D (22), was not significantly altered by 6-AN (Fig. 4B). NH4Cl repressed endogenous MEF2D- or Flag-MEF2D–dependent but not MEF2D-VP16–induced reporter activity (Fig. 4B). MEF2D-VP16–attenuated NH4Cl induced death of SN4741 cells (fig. S9). Similar to NH4Cl, α-synuclein also inhibited MEF2D function (Fig. 4C) and caused a 40% loss in neuronal viability (Fig. 4D). Coexpression of MEF2D-VP16 protected the cells against α-synuclein toxicity.

Fig. 4.

Impairment of MEF2 function and neuronal survival after blockade of CMA. (A) Inhibition of MEF2D DNA binding activity by NH4Cl. MEF2D DNA binding activity in SN4741 cells was assessed by EMSA after NH4Cl treatment (arrow indicates the specific MEF2D-probe complex). (B) Effect of enhanced nuclear MEF2D on NH4Cl-mediated inhibition. Levels of endogenous and transfected MEF2D in the nucleus (top panel) and MEF2 reporter activities (lower graph) in SN4741 cells were determined after 6-AN or NH4Cl treatment, respectively (n = 3, *P < 0.05). (C) Inhibition of MEF2 transactivation activity by α-synuclein. MEF2 reporter gene expression was measured after 36 hours of overexpression of wild-type or A53T α-synuclein in SN4741 cells (n = 4, *P < 0.05). (D) Effect of increasing nuclear MEF2D function on α-synuclein–induced neuronal death. The viability of SN4741 cells was determined by WST assay after overexpression of indicated proteins (mean ± SEM, n = 4; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

Our studies link CMA directly to the nuclear survival machinery. Because only α-synuclein mutants block substrate uptake in CMA (18), it has been unclear why an increase in the level of wild-type α-synuclein causes PD (23). Our findings that α-synuclein disrupts CMA-mediated degradation of MEF2D at a step prior to substrate uptake explain the toxic effects of both wild-type and mutant α-synuclein. Expression of Hsc70 suppresses α-synuclein toxicity in a Drosophila model of PD (24), consistent with our finding that maintenance of MEF2 function attenuates α-synuclein–induced neuronal death. Blocking CMA is accompanied by a clear decline of MEF2 function. Because the accumulated MEF2D binds poorly to DNA, the finding that the accumulated MEF2D binds poorly to DNA suggests important mechanisms in addition to nuclear export for the control of MEF2 activity. MEF2s play diverse roles in non-neuronal systems under physiological and pathological conditions (25). Our findings raise the possibility that degradation of MEF2s by CMA may function in other processes.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/323/5910/124/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S9

References

References and Notes

- 1.Mao Z, Bonni A, Xia F, Nadal-Vicens M, Greenberg ME. Science. 1999;286:785. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gong X, et al. Neuron. 2003;38:33. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez P, et al. Neurosci Lett. 2007;411:47. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith PD, et al. J Neurosci. 2006;26:440. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2875-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang X, et al. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4823. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1331-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dice JF. Autophagy. 2007;3:295. doi: 10.4161/auto.4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nixon RA. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:528. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubinsztein DC. Nature. 2006;443:780. doi: 10.1038/nature05291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bandhyopadhyay U, Cuervo AM. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42:120. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Son JH, et al. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00010.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saftig P, et al. EMBO J. 1995;14:3599. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chun HS, et al. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1010. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuervo AM, Knecht E, Terlecky SR, Dice JF. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:C1200. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.5.C1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massey A, Kiffin R, Cuervo AM. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2420. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finn PF, Mesires NT, Vine M, Dice JF. Autophagy. 2005;1:141. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.3.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seglen PO, Gordon PB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:1889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Majeski AE, Dice JF. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2435. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuervo AM, Stefanis L, Fredenburg R, Lansbury PT, Sulzer D. Science. 2004;305:1292. doi: 10.1126/science.1101738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Webb JL, Ravikumar B, Atkins J, Skepper JN, Rubinsztein DC. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300227200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin LJ, et al. J Neurosci. 2006;26:41. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mao Z, Wiedmann M. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.31102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bogerd HP, Fridell RA, Benson RE, Hua J, Cullen BR. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4207. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singleton AB, et al. Science. 2003;302:841. doi: 10.1126/science.1090278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Auluck PK, Chan HYE, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY, Bonini NM. Science. 2002;295:865. doi: 10.1126/science.1067389. published online 20 December 2001 (10.1126/science.1067389) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Czubryt MP, Olson EN. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2004;59:105. doi: 10.1210/rp.59.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.We thank H. Rees and D. Cooper at Emory Neuroscience NINDS Core Facility (NS055077) and UAB Neuroscience Core Facility (NS47466 and NS57098) for assistance in imaging and immunohistochemistry analysis, and J. Blum and A. M. Cuervo for Hsc70 and Lamp2a constructs. Supported by NIH grants NS048254 (Z.M.), AG023695 (Z.M.), and NS038065 (M.L.) and by Emory and UAB Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center pilot grants (Z.M. and J.J.S.) and the Robert Woodruff Health Sciences Center Fund (Z.M.).