Abstract

Cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) provide increasingly common models for infectious disease research. Several geographically distinct populations of these macaques from Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius are available for pathogenesis studies. Though host genetics may profoundly impact results of such studies, similarities and differences between populations are often overlooked. In this study we identified 47 full-length MHC class I nucleotide sequences in 16 cynomolgus macaques of Filipino origin. The majority of MHC class I sequences characterized (39 of 47) were unique to this regional population. However, we discovered eight sequences with perfect identity and six sequences with close similarity to previously defined MHC class I sequences from other macaque populations. We identified two ancestral MHC haplotypes that appear to be shared between Filipino and Mauritian cynomolgus macaques, notably a Mafa-B haplotype that has previously been shown to protect Mauritian cynomolgus macaques against challenge with a simian/human immunodeficiency virus, SHIV89.6P. We also identified a Filipino cynomolgus macaque MHC class I sequence for which the predicted protein sequence differs from Mamu-B*17 by a single amino acid. This is important because Mamu-B*17 is strongly associated with protection against simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) challenge in Indian rhesus macaques. These findings have implications for the evolutionary history of Filipino cynomolgus macaques as well as for the use of this model in SIV/SHIV research protocols.

Keywords: MHC, Filipino, Macaca fascicularis, SIV

Introduction

Nonhuman primates are excellent models for studying human disease because they are immunologically similar to humans and susceptible to many of the same pathogens (Bontrop 2001). Cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) are a common model for pathogenesis studies and are more readily available than Indian rhesus macaques, whose exportation from India was banned in 1978 (Southwick and Siddiqi 1994). Cynomolgus macaques have previously been used in studies of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), Ebola virus, and dengue virus (Capuano et al. 2003; Koraka et al. 2007; Walsh et al. 1996; Warfield et al. 2007). They are also widely used in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) pathogenesis and vaccine studies and may provide a useful and accurate model for studying coinfections of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Mtb (Pawar et al. 2008; Wiseman et al. 2007). Native, regional populations of cynomolgus macaques are found throughout continental Southeast Asia as well as on various islands including Indochina, the Philippines, and Malaysia. A recent geographically isolated population of cynomolgus macaques also live on the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius (Smith et al. 2007).

For infectious disease researchers using the cynomolgus macaque model, the 5 Mb major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region of the genome is of particular interest. The MHC is the most polymorphic region of the genome and this variation modulates progression of certain infectious diseases as well as rejection of transplanted organs (Bontrop and Watkins 2005; Goulder and Watkins 2008; Menninger et al. 2002; Otting et al. 2007; Wiseman and O’Connor 2007). Importantly, only a small subset of cynomolgus macaque MHC class I cDNA transcripts identified to date appear to be shared between the regional populations (Krebs et al. 2005; Pendley et al. 2008). It is therefore important to thoroughly analyze the MHC genetics of each regional cynomolgus macaque population. To our knowledge, no previous studies have focused on MHC class I cDNA sequence characterization in cynomolgus macaques from the Philippines, despite experimental protocols that use this population (Capuano et al. 2003; Koraka et al. 2007; Walsh et al. 1996; Warfield et al. 2007). Determining full-length Filipino cynomolgus macaque MHC class I cDNAs will enhance the utility of this model in pathogenesis studies.

Characterizing MHC class I transcripts in cynomolgus macaques may also provide insight into the origins of the exotic, invasive Mauritian population. Previous studies have analyzed protein polymorphisms, mitochondrial and Y chromosome DNA sequences, and autosomal microsatellite similarities. Based on these studies, Mauritian cynomolgus macaques are thought to have arisen from a founding population of Indonesian or a mixture of Indonesian and continental cynomolgus macaques (Blancher et al. 2008; Bonhomme et al. 2007, 2008; Kawamoto et al. 2008; Kondo et al. 1993; Lawler et al. 1995; Smith et al. 2007; Tosi and Coke 2007). Mauritian macaques share a subset of MHC class I sequences with the Indonesian population and class II DRB sequences with the Filipino population (Blancher et al. 2006; Pendley et al. 2008). Therefore, we hypothesized that some of the MHC class I alleles heretofore considered ‘unique’ to Mauritian macaques are in fact shared with Filipino macaques. However, since previous studies showed overall low-level sharing of MHC class I sequences in various regional populations of cynomolgus and rhesus macaques, we hypothesized that the majority of MHC class I cDNAs identified would be unique to Filipino cynomolgus macaques (Karl et al. 2008; Krebs et al. 2005; Otting et al. 2007; Pendley et al. 2008).

Methods & Materials

Animals

Whole blood samples from five cynomolgus macaques (PP01-PP05), originally from the Philippine island of Mindanao, were acquired from Primate Products Inc., Miami, Florida. Whole blood specimens from sixteen additional cynomolgus macaques (PC01-PC16), originally imported from Simian Conservation Breeding and Research Center (SICONBREC) Inc. on the island of Luzon in the Philippines, were obtained from the New Iberia Research Center (NIRC), University of Louisiana at Lafayette. It is unknown whether these 21 macaques were related to each other, as breeding records were not available.

RNA/DNA isolation, microsatellite analysis, cDNA synthesis, and cloning of MHC class I sequences

RNA and DNA were isolated from all 21 animals using the MagNAPure LC Instrument (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Using genomic DNA, microsatellite analysis of the MHC region was performed for all 21 animals as previously described (Karl et al. 2008; Wiseman et al. 2007). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized and PCR amplification (25–30 cycles) of MHC class I products was performed as previously described (Karl et al. 2008; Pendley et al. 2008). PCR product size distribution was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis; the 1.2 kb PCR product was excised and purified using Qiagen’s MinElute PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Sixteen of the 21 animals were selected for cloning and sequencing based largely on differences in microsatellite profiles.

These purified cDNA PCR products were ligated into the pCR®-Blunt II-TOPO® vector using the Invitrogen Zero Blunt TOPO PCR Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Ligations and transformations were performed as previously described, selecting 48 class IA locus and 96 class IB locus colonies for a total of 144 per animal (Karl et al. 2008; Pendley et al. 2008). DNA was isolated using the 5 PRIME Perfectprep Plasmid 96 Vac Direct Bind Kit (5 PRIME, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). DNA concentrations were determined by absorbance using a Nanodrop 1000 or Nanodrop 8000 (NanoDrop®, Wilmington, DE, USA). Restriction digests of plasmid DNA were performed for the first five animals (PP01-PP05) using EcoRI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) to determine which clones contained full-length MHC class I inserts. Restriction digests were discontinued after the first five animals showed excellent cloning efficiency (97%–100%).

Sequencing of MHC class I transcripts

For animals PP01-PP05, PC06, PC09, and PC12, sequencing was performed as previously described (Karl et al. 2008, Pendley et al. 2008). Clones were sequenced in the forward and reverse directions using five primers: T7, M13, 5’Refstrand_v2, 5’Transmembrane, and 3’Refstrand (Pendley et al. 2008). Sequencing products were purified and sequenced on the ABI 3730 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and analyzed using CodonCode Aligner (CodonCode Corp, Dedham, MA, USA) and Lasergene (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA) software. For each animal, 144 MHC class I clones were sequenced across the entire 1.2 kb MHC class I product.

For animals PC03, PC04, PC07, PC08, PC10, PC14, PC15 and PC16, a second approach was used to screen for novel sequences. 144 clones per animal containing full-length MHC class I inserts were initially sequenced unidirectionally through the most polymorphic region (~300 bp spanning exons 2 and 3 of MHC class I transcripts) using the primer 5′Refstrand (Karl et al. 2008). These sequences were analyzed for identity to each other. When three or more clones identical within the region screened were observed, a QIAGEN BR3000 robot (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) was used to isolate 3–5 representative clones from each identical group. Full-length sequencing was performed on these representative clones (10–34 per animal) using the same five primers and sequencing conditions as previously described. To avoid PCR error and ensure authenticity, MHC class I sequences were submitted to GenBank (accession numbers EU392103-EU392142 and EU606040-EU606045) and to the IMGT/MHC Non-human Primate Immuno Polymorphism Database-MHC (IPD-MHC) and NHP Nomenclature Committee only when three or more identical clones were observed (Robinson et al. 2003).

Amplification, cloning and sequencing of exons 2 through 4 in select animals

For three of the animals analyzed (PP02, PC09, and PC12), sequencing of clones containing the full-length MHC class I inserts failed to detect a Mafa-A1 allele predicted by microsatellite analysis to be shared by all three animals with PP03. This was likely due to a mismatch between Mafa-A1*5202 and the 5′MHC_UTR primer used for PCR amplification of the full-length MHC class I products, which resulted in more robust amplification of the other Mafa-A1 alleles present in these animals. To verify the presence of Mafa-A1*5202 in these three animals, we amplified a 596 base pair cDNA PCR product containing exons 2 through 4. Reactions were performed using high-fidelity Phusion™ Master Mix (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and 3.2 µM primers 5′MHC_DCG (5′-GGAGGGKCCRGAGTATTGGGA) and 3′MHC_DCG_A (5′-TCCAGAAGGCACCACCACAGCC). The following thermocycling conditions were used on an MJ Research Tetrad Thermocycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA): initial denaturation at 98°C for 3 min; 25 cycles of 98°C for 5 sec, 60°C for 1 sec, 72°C for 20 sec; and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were cloned using the same protocols as for the full-length MHC class I PCR products. Single pass sequencing of 96–192 clones from each animal with the T7 primer was sufficient for sequencing the entire amplicon.

Phylogenetic analysis

For phylogenetic analysis, we aligned the MHC class I cDNAs discovered in this study and selected MHC class I cDNAs from other populations of cynomolgus macaques, using MEGA 4 software and the CLUSTAL X program (Thompson et al. 1994). We reconstructed the phylogenetic relationships among these sequences using the Neighbor-Joining method based on the maximum composite likelihood distance (Saitou and Nei 1987; Tamura et al. 2007). We used bootstrapping to assess the reliability of clustering patterns; 1000 bootstrap pseudo-samples were used (Felsenstein 1985).

Results & Discussion

Summary of identified MHC class I cDNAs

Forty-seven Mafa-A and -B cDNAs were identified by full-length cloning and sequencing of the MHC class IA and IB loci in 16 Filipino cynomolgus macaques: 12 Mafa-A sequences, 29 Mafa-B sequences, and six Mafa-I sequences (Table 1). Eight MHC class I cDNAs identified in this study were previously reported in other regional populations of cynomolgus macaques and three MHC class I sequences described here are identical to cDNAs previously identified in Macaca mulatta or Macaca nemestrina. Thirty-nine MHC class I cDNAs identified in these Filipino cynomolgus macaques are novel.

Table 1. Filipino cynomolgus macaque MHC class I cDNAs.

The 47 MHC class I cDNAs identified in the 16 animal cohort of Filipino cynomolgus macaques and their GenBank accession numbers are listed. Each class I sequence is associated with the Filipino cynomolgus macaque(s) in which it was identified. For cDNAs that are identical to previously described sequences, the sequence name and accession number as well as species and regional population of origin are also listed.

| Allele | Accession # | Animal ID | Identical To | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mafa-A1*0401 | EU392107 | PP02, PP04, PC03, PC07, PC16 | ||

| Mafa-A1*0802 | EU392108 | PP04, PC06, PC12, PC14 | ||

| Mafa-A1*0803 | EU392109 | PP04 | ||

| Mafa-A1*5202 | EU392105 | PP03 |

Mafa-A1*5202 Mamu-A1*5201 |

(AM943361 - ICM) (1) (AM295917 - ChRM) (2) |

| Mafa-A1*8902 | EU392104 | PP01 | ||

| Mafa-A1*8903 | EU392110 | PP05, PC14, PC15 | Mafa-A1*8903 | (AM943360 - ICM) (1) |

| Mafa-A1*8904 | EU606040 | PC03 | ||

| Mafa-A1*8905 | EU606041 | PC10 | ||

| Mafa-A1*9301 | EU392103 | PP01, PC08, PC09 | ||

| Mafa-A1*9401 | EU392111 | PC04, PC07, PC08, PC15 | ||

| Mafa-A3*1303 | EU392112 | PC03, PC10 | ||

| Mafa-A4*0104 | EU392106 | PP02, PP03 | ||

| Mafa-B*0703 | EU392132 | PC04 | ||

| Mafa-B*2703a | EU392127 | PP05, PC03, PC04, PC07, PC10, PC14, PC16 | Mafa-B*2703 | (AM943363 - ICM) (1) |

| Mafa-B*3602 | EU392128 | PP02, PP05, PC06 | ||

| Mafa-B*400101 | AY958137 | PC03, PC08, PC14, PC16 |

Mafa-B*400101 Mamu-B*0703 |

(AY958137 - ICCM) (3) (AJ556876 - InRM) (4) (EF580149 - ChRM) (5) |

| Mafa-B*400102 | EU392135 | PC02, PC03, PC08 | ||

| Mafa-B*4002 | EU392120 | PP02 | ||

| Mafa-B*4403 | EU392126 | PP05, PC03, PC04, PC07, PC10, PC14, PC16 | Mafa-B*4403 | (EU203725 - ICM) (6) |

| Mafa-B*490101 | EU392113 | PP03, PC06, PC09, PC12, PC15 | Mafa-B*490101 | (AY958148 - MCM) (3) |

| Mafa-B*5702 | EU392129 | PP04 | ||

| Mafa-B*5901 | EU392117 | PP01 | Mafa-B*5901 | (EU203723 - ICM) (6) |

| Mafa-B*6402 | EU392130 | PC04 | ||

| Mafa-B*6502 | EU392118 | PP03, PC06, PC09, PC12, PC15 | ||

| Mafa-B*6802 | EU392114 | PP01 | ||

| Mafa-B*740102 | EU392115 | PP01 | ||

| Mafa-B*7702 | EU392138 | PC03, PC10 | ||

| Mafa-B*8001 | EU392116 | PP01 | ||

| Mafa-B*8101 | EU392119 | PP02, PP04, PP05, PC06, PC10, PC12 | ||

| Mafa-B*8201 | EU392121 | PP02, PP04, PP05, PC06, PC10, PC12 | ||

| Mafa-B*8301 | EU392122 | PP02, PC03, PC08, PC14, PC16 | ||

| Mafa-B*8401 | EU392123 | PP02, PP04, PP05, PC06, PC10 | ||

| Mafa-B*8501 | EU392124 | PP04 | ||

| Mafa-B*8502 | EU606043 | PC16 | ||

| Mafa-B*860101 | EU392131 | PC04 | ||

| Mafa-B*860102 | EU392125 | PP04 | ||

| Mafa-B*8701 | EU392133 | PC07, PC15 | ||

| Mafa-B*8801 | EU392134 | PC07, PC15 | ||

| Mafa-B*8901 | EU392136 | PC08, PC14 | ||

| Mafa-B*9001 | EU392137 | PC03, PC08, PC10, PC16 | ||

| Mafa-B*9201 | EU606042 | PC08 | ||

| Mafa-I*010102 | EU392139 | PP02, PP05, PC10 | ||

| Mafa-I*0111 | EU392142 | PP03, PC09, PC12, PC15 |

Mafa-I*100201 Mane-I*0101 |

(DQ979885 - MCM) (7) (AY204739 - PTM) (8) |

| Mafa-I*0112 | EU392140 | PC03, PC08, PC10, PC14, PC16 | ||

| Mafa-I*011202 | EU606044 | PC07 | ||

| Mafa-I*0113 | EU392141 | PC03, PC08, PC14 | ||

| Mafa-I*0114 | EU606045 | PC10 | ||

Cynomolgus macaque abbreviations – ICM = Indonesian, MCM = Mauritian, ICCM = Indochinese; rhesus macaque abbreviations – InRM = Indian, ChRM = Chinese; pigtailed macaque abbreviation – PTM. References for previously identified MHC class I cDNAs are: (1) (Mee et al., unpublished sequence retrieved from GenBank), (2) (Otting et al. 2007), (3) (Krebs et al. 2005), (4) (Otting et al. 2005), (5) (Karl et al. 2008), (6) (Pendley et al. 2008), (7) (Wiseman et al. 2007), (8) (Lafont et al. 2003)

Mafa-B*2703 may be a pseudogene, as it lacks both of the initiating methionines typical of MHC class I cDNAs.

Sharing of MHC class I cDNAs among Filipino cynomolgus macaques

Of the Mafa-A and -B cDNAs identified in this study, more than half were identified in multiple animals (Table 1). Although the 16 animals are from two different sources, there is extensive sequence sharing between these two presumably independent cohorts. This high degree of sequence sharing among these Filipino animals is in contrast to findings in a similar sampling of Indonesian cynomolgus macaques, in which only seven of 48 described MHC class I cDNAs were shared among animals (Pendley et al. 2008).

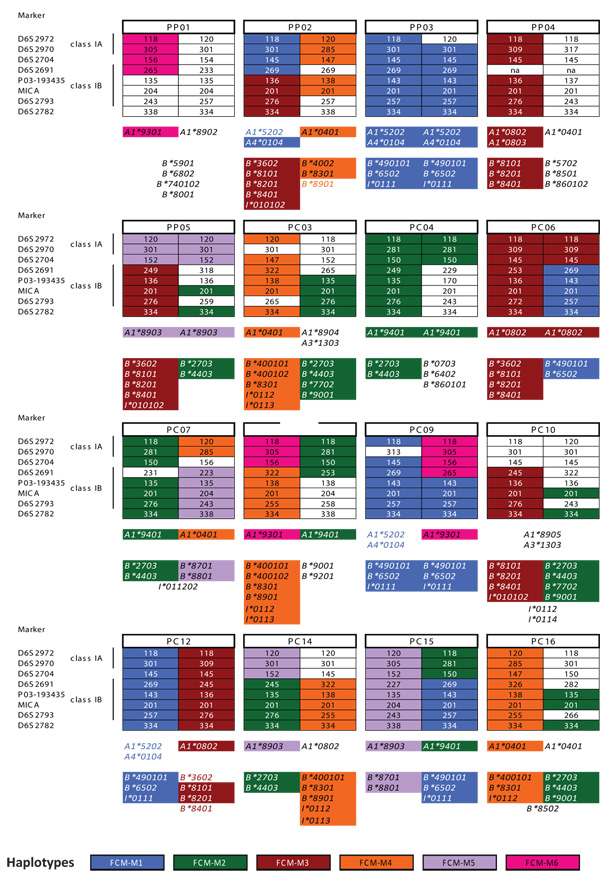

To examine whether this high degree of sequence sharing corresponded to haplotype sharing, we evaluated genomic DNA using microsatellite markers spanning the entire MHC region (Karl et al. 2008; Wiseman et al. 2007). Using microsatellite markers and cDNA sequences, we inferred six haplotypes within the MHC class I region (Figure 1). The entire repertoire of cDNAs predicted to associate with each of the six microsatellite haplotypes was not always observed in every animal. This is likely due to differences in transcription levels between major and minor class I cDNAs; minor cDNAs in nonhuman primates are expressed at lower levels than major CDNAs and are thus less likely to be observed in a limited sampling (Otting et al. 2005, 2007).

Figure 1. Shared microsatellite haplotypes and cDNAs for 16 Filipino cynomolgus macaques.

The microsatellite haplotype profiles are shown along with the cDNAs identified in each of the 16 animals analyzed by cloning and sequencing. Each of the two columns under the animal name represents an inferred microsatellite haplotype. Six shared microsatellite haplotypes, FCM-M1 through FCM-M6, are highlighted to indicate any cDNAs inferred to be associated with those haplotypes. Any cDNAs detected via sequencing of the 596 base pair amplicon in animals PP02, PC09, and PC12 have text color-coded to correspond to the associated haplotype. Some sequences could not be inferred to belong specifically to one haplotype; in those cases the sequence names are not color-coded and are listed between both haplotypes.

The two most common haplotypes in this cohort are FCM-M1 and FCM-M2; the Mafa-A region of these two haplotypes were each identified in 5 of the 32 chromosomes examined (two haplotypes per animal for 16 animals) and the Mafa-B region of FCM-M1 and FCM-M2 were each found in 7 chromosomes. Animal PP03 is homozygous for FCM-M1 throughout the MHC class I region while PC09 is homozygous for the same haplotype in only the Mafa-B region. Overall, 25 of the 32 haplotypes (78%) observed in the Mafa-A region of our cohort of Filipino cynomolgus macaques can be attributed to six common shared haplotypes. In the Mafa-B region, an inferred MHC haplotype could not be derived for the FCM-M6. However, the five remaining haplotypes, FCM-M1 through FCM-M5, account for 84% (27 of 32 haplotypes) of the Mafa-B region diversity. This cohort of cynomolgus macaques correlates to previous observations that this regional population has decreased genetic diversity, supporting the hypothesis that it may have arisen from a small founding population (Blancher et al. 2008; Sano et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2007).

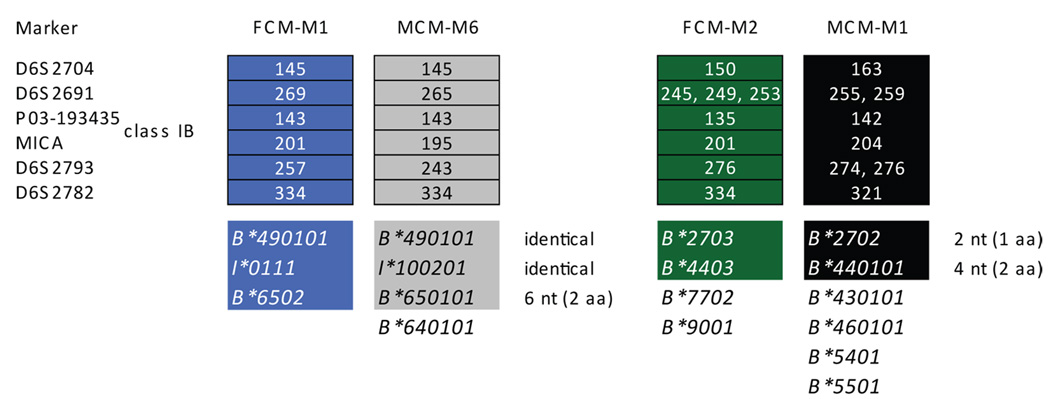

MHC class I cDNA comparisons with other regional cynomolgus macaque populations

We identified two MHC class I cDNA sequences in the Filipino cynomolgus macaques that are identical to sequences previously identified in Mauritian cynomolgus macaques (Figure 2). Mafa-B*490101 and Mafa-I*0111 (previously Mafa-I*100201) on the FCM-M1 haplotype in Filipino cynomolgus macaques are both found on the M6 haplotype of Mauritian cynomolgus macaques (Wiseman et al. 2007). Additionally, a third cDNA sequence associated with the FCM-M1 Mafa-B haplotype, Mafa-B*6502, differs by only six nucleotides (two amino acids) from Mafa-B*650101, which is also present on the MCM-M6 haplotype. Likewise, two Mafa-B sequences from the FCM-M2 haplotype are highly similar (at least 99.5% nucleotide identical) to two of the six sequences present on the MCM-M1 haplotype (Florese et al. 2008; Wiseman et al. 2007). It is likely that these two haplotypes are derived from common ancestors of both Filipino and Mauritian cynomolgus macaques.

Figure 2. Ancestral Mafa-B MHC haplotypes shared between Filipino and Mauritian cynomolgus macaques.

Two common microsatellite haplotypes identified in the Filipino cynomolgus macaque cohort carry Mafa-B sequences that are nucleotide identical or highly similar to sequences associated with previously identified Mauritian cynomolgus macaque MHC haplotypes (Wiseman et al. 2007). These cDNAs are highlighted to correspond with their associated microsatellite haplotypes, and number of nucleotide (nt) and amino acid (aa) differences are indicated after each pair of related cDNAs. Unhighlighted sequences are not detected in animals from both regional populations. FCM = Filipino cynomolgus macaque, MCM = Mauritian cynomolgus macaque.

MHC class I cDNA sequence sharing was also observed between the Filipino and Indonesian cynomolgus macaque regional populations. Two Mafa-A sequences (Mafa-A1*5202 and Mafa-A1*8903) and three Mafa-B sequences (Mafa-B*2703, Mafa-B*4403, and Mafa-B*5901) were shared between the two populations (Table 1). In addition to these five identical sequences, three highly similar cDNAs were identified in each geographically distinct population. Mafa-B*740102 in the Filipino population varies from the Indonesian sequence Mafa-B*7401 by a single synonymous base substitution (Pendley et al. 2008). The Filipino sequence Mafa-B*5702 is identical throughout the peptide binding region to the Indonesian sequence Mafa-B*5701 (one nucleotide/one amino acid different overall) (Pendley et al. 2008). Lastly, the Filipino sequence Mafa-B*6802 differs from the Indonesian sequence Mafa-B*6801 by six nucleotides, resulting in two amino acid changes (Pendley et al. 2008).

As shown in Table 1, only one Mafa-B sequence, Mafa-B*400101, was identical in both the Filipino and Indochinese regional populations. However, three MHC class I sequences in the Filipino cynomolgus macaque regional population are also nucleotide identical to sequences identified in other species of macaques. A similarly low frequency of shared MHC class I sequences between species has been observed previously among cynomolgus, rhesus, and pigtail macaques (Otting et al. 2007; Pendley et al. 2008).

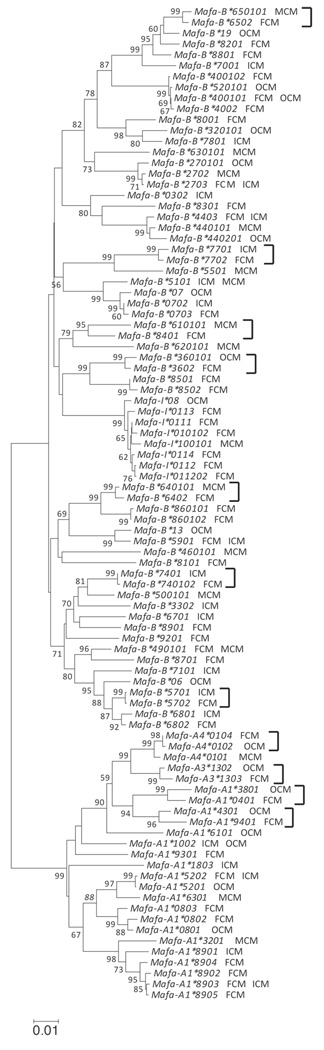

Phylogenetic relationships among cynomolgus macaque MHC class I cDNAs

Characterizing the MHC class I cDNA transcripts from Filipino cynomolgus macaques enables better definition of the relationship among sequences from different populations. We examined the phylogenetic relationships between the MHC class I cDNAs discovered in this study and selected MHC class I cDNAs from other populations of cynomolgus macaques based on nucleotide sequence similarity, as shown in Figure 3 (Krebs et al. 2005; Otting et al. 2007; Pendley et al. 2008; Uda et al. 2004, 2005; Wiseman et al. 2007). The phylogenetic tree showed that Filipino sequences were intermingled with those from Indonesia, Mauritius, and elsewhere (Figure 3). There was no evidence of any geographically specific clade of Mafa-A, Mafa-B, or Mafa-I sequences. Every group of three or more sequences that received significant (95% or better) bootstrap support included sequences from at least two geographic regions.

Figure 3. Phylogenetic relationship between MHC class I sequences identified in Filipino, Indonesian, Mauritian, and other regional populations of cynomolgus macaques.

The MHC class I nucleotide sequences identified in Filipino cynomolgus macaques were analyzed, along with closely related MHC class I cDNAs in Mauritian and Indonesian cynomolgus macaques, as well as other regional populations. MHC class I cDNAs discovered in Filipino cynomolgus macaques are denoted with FCM while cDNAs identified in Indonesian and Mauritian cynomolgus macaques are denoted with ICM and MCM, respectively. MHC class I cDNAs identified in other populations of macaques (continental and those of unknown origin) are denoted with OCM. It should be noted that several Mafa sequences have been recently renamed by the NHP Nomenclature Committee. Correspondence between the new and original sequence names can be found at the IPD-MHC website (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ipd). Bootstrapping analysis was performed and numeric values are displayed for values greater than or equal to 50. Sister pairs consisting of one Filipino sequence and one sequence from elsewhere and receiving 95% or better bootstrap support are designated by brackets.

Likewise, in the phylogenetic tree, we identified 11 “sister pairs” consisting of one sequence found only in the Filipino population and another from a population outside the Philippines; each of these pairs received significant (95% or better) bootstrap support (Figure 3). In three of these pairs the other sequence was from Indonesia; in three pairs the other sequence was from Mauritius; in five pairs the other sequence was from continental or unknown origin. Finally, in the Filipino- and Indonesian-origin animals that expressed the subset of identical or highly similar class I sequences, there was also no apparent microsatellite haplotype sharing (data not shown).

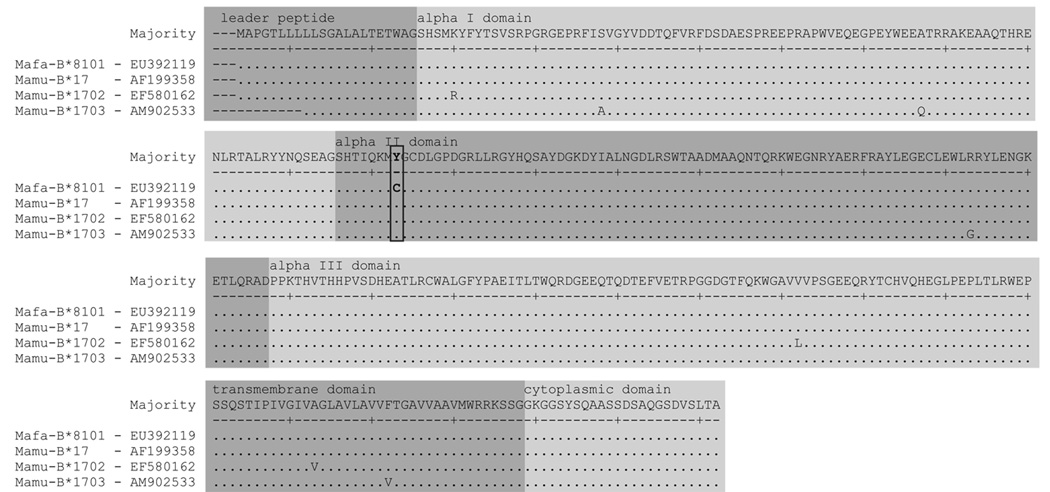

Filipino macaque MHC class I sequence sharing with Indian rhesus macaques

Interestingly, a comparison of the predicted protein products of Mafa-B*8101 (associated with FCM-M3) and Mamu-B*17 from Indian rhesus macaques shows that these two transcripts differ throughout the entire coding region by only a single amino acid substitution in the alpha II domain, a tyrosine substitution (C99Y). Figure 4 shows the alignments of these apparent orthologs, along with two Mamu-B*17 variants identified in Chinese rhesus macaques. This observation is of particular interest because Mamu-B*17 is associated with long-term non-progression in SIV (Yant et al. 2006).

Figure 4. Alignment of predicted protein products of Mafa-B*8101 and Mamu-B*17 family members.

Alignments of Mafa-B*8101 and Mamu-B*17, along with two additional Mamu-B*17 variants identified in the Chinese rhesus regional population, Mamu-B*1702 and Mamu-B*1703 (Karl et al. 2008; Otting et al. 2008). Given the alpha I and alpha II domain similarity between these apparent orthologs, they may be able to present a similar set of peptides.

Evolutionary implications

Following the arrival and subsequent divergence of the genus Macaca in Southeast Asia approximately 2 million years ago, the fascicularis species has dispersed throughout the region (Abegg and Thierry 2002). This expansion is believed to coincide with the glaciation events during the late Pleistocene epoch, when lowering sea levels exposed the Sunda Shelf making land bridges between continental Asia and islands of present-day Indonesia (Voris 2000). It is during this time that M. fascicularis likely migrated into Borneo, Sumatra, and Java from the Asian mainland. It has been hypothesized that M. fascicularis reached the Philippines via sea rafting from Borneo, as the Philippine islands were never connected to the Sunda Shelf (Abegg and Thierry 2002; Voris 2000).

Filipino cynomolgus macaques share identical or highly similar MHC class I cDNA sequences with Indonesian and Mauritian cynomolgus macaques that are likely derived from ancestral transcripts. This may indicate that the Filipino and Mauritian populations arose from the same founding populations of Indonesian macaques, as proposed by previous studies (Blancher et al. 2008; Bonhomme et al. 2007; Kawamoto et al. 2008; Kondo et al. 1993; Lawler et al. 1995; Smith et al. 2007; Tosi and Coke 2007). The identification of two ancestral haplotypes in the Filipino and Mauritian regional populations also supports a common ancestry between these insular regional populations.

Implications for SIV research

In this study we identified an MHC class I sequence that varies from Mamu-B*17 by a single amino acid in the alpha II domain. Previous studies indicate that Mamu-B*17 expression correlates with decreased viremia in Indian rhesus macaques challenged with SIVmac239 (Yant et al. 2006). MHC class I proteins with nearly identical alpha I and alpha II domain sequences may present similar sets of peptides since class I molecules interact with peptides through these sequences motifs. It is possible then that Filipino cynomolgus macaques that express Mafa-B*8101 may exhibit superior SIVmac239 control. Additionally, molecular reagents used to study Mamu-B*17-restricted CD8 T cell responses in Indian rhesus macaques may also be effective in evaluating SIV-specific CD8 T cell responses in Mafa-B*8101-positive Filipino cynomolgus macaques.

The FCM-M1 ancestral haplotype that is shared between the Filipino and Mauritian cynomolgus macaque regional populations could also have implications for the use of Filipino cynomolgus macaques in SIV research. The similar Mauritian MCM-M6 class IB haplotype is significantly associated with low chronic phase viral loads following SHIV89.6P challenge (Florese et al. 2008); however, the full MCM-M6 haplotype only occurs at a frequency of 5%, and the class IB region of this haplotype occurs at a frequency of 8% (Wiseman et al. 2007; unpublished data). In contrast, the frequency of the FCM-M1 class IB haplotype in this Filipino cynomolgus macaque cohort is 22% (seven of the 32 characterized haplotypes). While this frequency may be skewed by potential relatedness of the animals studied, the presence of the FCM-M1 Mafa-B haplotype in nearly one third of our cohort (5 of 16 animals) suggests that it may be relatively common. Therefore, obtaining significant numbers of FCM-M1 Filipino cynomolgus macaques may be easier than obtaining MCM-M6 Mauritian macaques for SIV/SHIV research. However, further study is needed to determine if FCM-M1-positive macaques are able to control SHIV and/or SIV infections.

This study characterized 47 full-length MHC class I sequences in Filipino cynomolgus macaques, 39 of which are previously unreported. Our findings support the hypothesis that the regional population of Filipino cynomolgus macaques was founded by macaques that dispersed from Indonesia. Additionally, the identification of two ancestral haplotypes in the Filipino and Mauritian regional populations supports a common ancestry for these macaques. Finally, the sequence similarities between Mafa-B*8101 in Filipino cynomolgus macaques and Mamu-B*17 in Indian rhesus macaques, as well as the similarities between the Filipino and Mauritian cynomolgus macaques, show potential for Filipino cynomolgus macaques as an effective alternative to study the genetics of natural SIV/SHIV protection.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Natasja de Groot, Nel Otting, and the IMGT Non-human Primate Nomenclature Committee for naming the Mafa-A and Mafa-B sequences. We thank Claire O’Leary for editorial assistance and other members of the O’Connor laboratory for helpful discussions. This work was supported by 1 R24 RR021745-01A1. This publication was also made possible in part by grant number P51 RR000167 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), to the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison. This research was conducted in part at a facility constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program grant numbers RR15459-01 and RR020141-01. Partial support was provided by NIH grant GM43940 to A.L.H. This publication’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCRR or NIH.

References

- Abegg C, Thierry B. Macaque evolution and dispersal in insular south-east Asia. Biol J Linnean Soc. 2002;75:555–576. [Google Scholar]

- Blancher A, Tisseyre P, Dutaur M, Apoil PA, Maurer C, Quesniaux V, Raulf F, Bigaud M, Abbal M. Study of cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) MhcDRB (Mafa-DRB) polymorphism in two populations. Immunogenetics. 2006;58:269–282. doi: 10.1007/s00251-006-0102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blancher A, Bonhomme M, Crouau-Roy B, Terao K, Kitano T, Saitou N. Mitochondrial DNA sequence phylogeny of 4 populations of the widely distributed cynomolgus macaque (Macaca fascicularis fascicularis) J Hered. 2008;99:254–264. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esn003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonhomme M, Blancher A, Jalil MF, Crouau-Roy B. Factors shaping genetic variation in the MHC of natural non-human primate populations. Tissue Antigens. 2007;70:398–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2007.00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonhomme M, Blancher A, Cuartero S, Chikhi L, Crouau-Roy B. Origin and number of founders in an introduced insular primate: estimation from nuclear genetic data. Mol Ecol. 2008;17:1009–1019. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontrop RE. Non-human primates: essential partners in biomedical research. Immunol Rev. 2001;183:5–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1830101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontrop RE, Watkins DI. MHC polymorphism: AIDS susceptibility in non-human primates. Trends Immunology. 2005;26:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capuano SV, Croix DA, Pawar S, Zinovik A, Myers A, Lin PL, Bissel S, Fuhrman C, Klein E, Flynn JL. Experimental Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of cynomolgus macaques closely resembles the various manifestations of human M. tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5831–5844. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5831-5844.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florese RH, Wiseman RW, Venzon D, Karl JA, Demberg T, Larsen K, Flanary L, Kalyanaraman VS, Pal R, Titti F, Patterson LJ, Heath MJ, O’Connor DH, Cafaro A, Ensoli B, Robert-Guroff M. Comparative study of Tat vaccine regimens in Mauritian cynomolgus and Indian rhesus macaques: influence of Mauritian MHC haplotypes on susceptibility/resistance to SHIV89.6P infection. Vaccine. 2008;26:3312–3321. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.03.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulder PJ, Watkins DI. Impact of MHC class I diversity on immune control of immunodeficiency virus replication. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:619–630. doi: 10.1038/nri2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl JA, Wiseman RW, Campbell KJ, Blasky AJ, Hughes AL, Ferguson B, Read DS, O'Connor DH. Identification of MHC class I sequences in Chinese-origin rhesus macaques. Immunogenetics. 2008;60:37–46. doi: 10.1007/s00251-007-0267-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto Y, Kawamoto S, Matsubayashi K, Nozawa K, Watanabe T, Stanley MA, Perwitasari-Farajallah D. Genetic diversity of longtail macaques (Macaca fascicularis) on the island of Mauritius: an assessment of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms. J Med Primatol. 2008;37:45–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2007.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo M, Kawamoto Y, Nozawa K, Matsubayashi K, Watanabe T, Griffiths O, Stanley M. Population genetics of crab-eating macaques (Macaca fascicularis) on the island of Mauritius. Am J Primatol. 1993;29:167–182. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350290303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koraka P, Benton S, van Amerongen G, Stittelaar KJ, Osterhaus A. Characterization of humoral and cellular immune responses in cynomolgus macaques upon primary and subsequent heterologous infections with dengue viruses. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:940–946. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs KC, Jin Z, Rudersdorf R, Hughes AL, O'Connor DH. Unusually high frequency MHC class I alleles in Mauritian origin cynomolgus macaques. J Immunol. 2005;175:5230–5239. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafont BA, Buckler-White A, Plishka R, Buckler C, Martin MA. Characterization of pig-tailed macaque classical MHC class I genes: implications for MHC evolution and antigen presentation in macaques. J Immunol. 2003;171:875–885. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler SH, Sussman RW, Taylor LL. Mitochondrial DNA of the Mauritian macaques (Macaca fascicularis): an example of the founder effect. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1995;96:133–141. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330960203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menninger K, Wieczorek G, Riesen S, Kunkler A, Audet M, Blancher A, Schuurman HJ, Quesniaux V, Bigaud M. The origin of cynomolgus monkey affects the outcome of kidney allografts under neoral immunosuppression. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:2887–2888. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(02)03547-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otting N, Heijmans CM, Noort RC, de Groot NG, Doxiadis GG, van Rood JJ, Watkins DI, Bontrop RE. Unparalleled complexity of the MHC class I region in rhesus macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:1626–1631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409084102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otting N, de Vos-Rouweler AJ, Heijmans CM, de Groot NG, Doxiadis GG, Bontrop RE. MHC class I A region diversity and polymorphism in macaque species. Immunogenetics. 2007;59:367–375. doi: 10.1007/s00251-007-0201-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otting N, Heijmans C, van der Wiel M, de Groot N, Doxiadis GG, Bontrop RE. A snapshot of the Mamu-B genes and their allelic repertoire in rhesus macaques of Chinese origin. Immunogenetics. 2008;60:507–514. doi: 10.1007/s00251-008-0311-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawar SN, Mattila JT, Sturgeon TJ, Lin PL, Narayan O, Montelaro RC, Flynn JL. Comparison of the effects of pathogenic simian human immunodeficiency virus strains SHIV-89.6P and SHIV-KU2 in cynomolgus macaques. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24:643–654. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendley CJ, Becker EA, Karl JA, Blasky AJ, Wiseman RW, Hughes AL, O'Connor SL, O'Connor DH. MHC class I characterization of Indonesian cynomolgus macaques. Immunogenetics. 2008;60:339–351. doi: 10.1007/s00251-008-0292-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J, Waller MJ, Parham P, de Groot N, Bontrop R, Kennedy LJ, Stoehr P, Marsh SG. IMGT/HLA and IMGT/MHC: sequence databases for the study of the major histocompatibility complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:311–314. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano K, Shiina T, Kohara S, Yanagiya K, Hosomichi K, Shimizu S, Anzai T, Watanabe A, Ogasawara K, Torii R, Kulski JK, Inoko H. Novel cynomolgus macaque MHC-DPB1 polymorphisms in three South-East Asian populations. Tissue Antigens. 2006;67:297–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2006.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DG, McDonough JW, George DA. Mitochondrial DNA variation within and among regional populations of longtail macaques (Macaca fascicularis) in relation to other species of the fascicularis group of macaques. Am J Primatol. 2007;69:182–198. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwick CH, Siddiqi MF. Population status of nonhuman primates in Asia, with emphasis on rhesus macaques in India. Am J Primatology. 1994;34:51–59. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350340110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosi AJ, Coke CS. Comparative phylogenetics offer new insights into the biogeographic history of Macaca fascicularis and the origin of the Mauritian macaques. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2007;42:498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uda A, Tanabayashi K, Yamada YK, Akari H, Lee YJ, Mukai R, Terao K, Yamada A. Detection of 14 alleles derived from the MHC class I A locus in cynomolgus monkeys. Immunogenetics. 2004;56:155–163. doi: 10.1007/s00251-004-0683-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uda A, Tanabayashi K, Fujita O, Hotta A, Terao K, Yamada A. Identification of the MHC class I B locus in cynomolgus monkeys. Immunogenetics. 2005;57:189–197. doi: 10.1007/s00251-005-0782-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voris HK. Maps of Pleistocene sea levels in Southeast Asia: shorelines, river systems and time durations. J Biogeogr. 2000;27:1153–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh GP, Tan EV, dela Cruz EC, Abalos RM, Villahermosa LG, Young LJ, Cellona RV, Nazareno JB, Horwitz MA. The Philippine cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) provides a new nonhuman primate model of tuberculosis that resembles human disease. Nat Med. 1996;2:430–436. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warfield KL, Swenson DL, Olinger GG, Kalina WV, Aman MJ, Bavari S. Ebola virus-like particle-based vaccine protects nonhuman primates against lethal Ebola virus challenge. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:S430–S437. doi: 10.1086/520583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman RW, Wojcechowskyj JA, Greene JM, Blasky AJ, Gopon T, Soma T, Friedrich TC, O'Connor SL, O'Connor DH. Simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 infection of major histocompatibility complex-identical cynomolgus macaques from Mauritius. J Virol. 2007;81:349–361. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01841-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman RW, O’Connor DH. Major histocompatibility complex-defined macaques in transplantation research. Transplant Rev. 2007;21:17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yant LJ, Friedrich TC, Johnson RC, May GE, Maness NJ, Enz AM, Lifson JD, O’Connor DH, Carrington M, Watkins DI. The high-frequency major histocompatibility complex class I allele Mamu-B*17 is associated with control of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 replication. J Virol. 2006;80:5074–5077. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.5074-5077.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]