Abstract

Membranes of adjacent cells form intercellular junctional complexes to mechanically anchor neighbour cells (anchoring junctions), to seal the paracellular space and to prevent diffusion of integral proteins within the plasma membrane (tight junctions) and to allow cell-to-cell diffusion of small ions and molecules (gap junctions). These different types of specialised plasma membrane microdomains, sharing common adaptor molecules, particularly zonula occludens proteins, frequently present intermingled relationships where the different proteins co-assemble into macromolecular complexes and their expressions are co-ordinately regulated. Proteins forming gap junction channels (connexins, particularly) and proteins fulfilling cell attachment or forming tight junction strands mutually influence expression and functions of one another.

Keywords: Gap junction, Tight junction, Apical junction, Adherens junction, Connexin, ZO-1

1. Introduction

In various tissues, e.g. in different types of epithelia, membranes in contact form intercellular junctional complexes comprising tight junctions, adherens junctions, and gap junctions. These different membrane specialisations fulfill different roles, tight junctions serving the major functional purpose of providing a “barrier” and a “fence” within the membrane by regulating paracellular permeability and maintaining cell polarity, anchoring junctions couple cytoskeletal elements to the plasma membrane at cell–cell contacts, providing mechanical integrity to tissues, whereas gap junctions allow the passage of small molecular weight solutes directly between neighbouring cells. The three types of junctions frequently intermingle with each other, sharing common proteins, termed adaptors, particularly zonula occludens (ZOs, ZO-1 being the most common), that are able to recruit other regulatory and structural proteins to the sites of intercellular junctional complexes. Adaptors are indeed composed of conserved protein binding domains, which allow them to link a variety of structural or signalling proteins to form multi-protein complexes to the same site and to tether transmembrane proteins belonging to anchoring, tight or gap junctions to the underlying cytoskeleton (which also plays important roles in bridging different protein complexes of the different intercellular junctions). The release or incorporation of these adaptors by one of the types of junctions plausibly interferes with the junction complexity and the stability of other junctions. Moreover, these adaptors per se can be substrates and/or activators of kinases or phosphatases. These close relationships allow the different types of junctions to mutually influence via these extensive networks. Moreover, protein–protein interactions may also activate signal transduction pathways (e.g. G-protein cascades, see Section 6.1) influencing the behaviour of other membrane junctions.

2. Methodological approaches for detection of protein partners

The determination of protein–protein interactions is no easy matter, with an abundance of potentially false positive detections with several methodologies, leading to the need to seek after protein partners using many different approaches. The most traditional methods are “directed” studies, with the strategy to identify potential protein partners on the basis of previous studies or preliminary functional or structural data. Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy is used to investigate co-localization of junctional proteins with protein partners, to examine if their similar subcellular localization makes possible a physical interaction between two proteins. Co-immunoprecipitation assays allow substantiation of their interaction. These approaches require identifying the potential partners and the availability of high affinity specific antibodies to them. In co-immunoprecipitation studies, cells or tissues are lysed in non-denaturing buffers; then using junctional protein antibodies, the complexes are pulled down from solution and run on denaturing gels to disaggregate the complexes. Proteins are electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, which are probed for the potential binding partner by means of specific antibodies. This traditional identification method is low throughput but relatively high stringency. To confirm that a binding partner pulled down with co-immunoprecipitation is a possible partner, and not an artefact of cell lysis condition, the reverse pull down should also be done where the identified protein is pulled down with its specific antibody and the complex is probed for the protein of interest. An additional stringent control is the use of cells or tissues in which the protein of interest is absent, such as transgenic null mice.

Several “non-directed” approaches with high throughput screens are also used, such as employing purified protein portions of junctional proteins (such as their N- or C-terminus domain) as “bait” for protein partners. The expressed domain of interest is incubated with cell or tissue lysates, and then directly pulled down and the complexes of protein run out on a denaturing SDS gel. The 2-D or 3-D gel is then either western blotted and proteins identified using specific antibodies, or stained to highlight the presence of a band of protein which is excised, allowing identification of individual proteins by means of HPLC or MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Another methodology is to use antibody arrays to examine groups of potential protein partners. In this procedure, antibodies to a wide variety of potential partners of junctional protein are immobilized on nitrocellulose membranes in clusters of related proteins and incubated with cell or tissue lysates, and protein complexes are captured by specific antibodies. The presence of junctional proteins within these complexes is then probed using HRP-tagged connexin specific antibodies. These methods allow simultaneous probing of a large number of potential partners; moreover, if arrays are prepared by a commercial entity, the risk of investigator bias is partially prevented. More directed searches can be done, if the arrays are made “in house” with antibodies against particular proteins being immobilized on nitrocellulose. If these antibodies are chosen due to either functional or structural relationship to a given protein, the arrays have the potential to yield entire pathways which involve Cx–protein interactions. Among in vitro approaches developed to compare binding affinities of identified protein partners of Cxs, the surface plasmon resonance measures the change in refractive index of a solvent near a surface (typically a gold film) that occurs during complex formation or dissociation.

The barrier function of tight junctions can be estimated by either the transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) measurement or the estimation of the paracellular flux, for example of 14C-inulin, 14C-mannitol or BODIPY-sphingomyelin or with fluorescent cell impermeant molecules such as FITC-dextran, whereas the cell-to-cell coupling through gap junctions can be assessed in dual voltage-clamp conditions (gap junctional conductance) or by intercellular diffusion of intracellularly injected or scrape-loaded fluorescent dye.

3. Gap junction proteins

All gap junction channels have a similar overall structure but, unlike most other membrane channels, different gene families encode the channel-forming proteins in different animal phyla. Gap junction structure and functions were for a long time mainly investigated in vertebrates, where they were believed to be solely formed by connexins (Cxs). Then, in C. elegans (a nematode) and Drosophila (an arthropod), which have no Cx genes, gap junctions were found to be encoded by another gene family, the innexins (Inxs, invertebrate analogues of Cxs), which have no sequence homology to Cxs [1]. The list of animal phyla with identified members of the Inx family progressively extended to platyhelminthes, annelida, coelenterata and mollusca (see [2] for review). Sequences with low, but detectable, similarity to Inxs were then identified in vertebrate chordates, leading some authors to suggest that the protein family be re-named pannexins (from the Greek “pan”, all, entire, and nexus, connection), abbreviated Panxs [3]. Using statistical, topological and conserved sequence motif analyses, Yen and Saier [4] recently proposed that Inxs and Panxs would belong to a single superfamily. White et al. [5] showed that Cx genes were not restricted to vertebrate animals but were also present in invertebrate chordates (e.g. in tunicates, ascidians and appendicularians).

Cxs, Inxs and Panxs share with claudins and occludins, two essential tight junctional components, similar topologies, with 4 α-helical transmembrane segments (TMSs); all proteins exhibit well-conserved extracellular cysteinyl residues that either are known to or potentially can form disulfide bridges. Yen and Saier [4] used a multiple alignment of the protein sequences of the different families of gap junction proteins to derive average hydropathy and similarity plots as well as phylogenetic trees. The data obtained led to several evolutionary, structural and functional suggestions, in particular (i) the most conserved regions of the proteins of the different families are the 4 TMSs (although the extracellular loops between TMSs 1 and 2, and TMSs 3 and 4 are also usually well conserved). (ii) The phylogenetic trees revealed sets of orthologues except for Inxs, where phylogeny primarily reflects organismal source (possibly on account of the lack of relevant invertebrate genome sequence data. (iii) Conserved cysteinyl residues in Cxs and Inxs pointed to a similar extracellular structure involved in the docking of hemi-channels to form intercellular channels. (iv) In claudins and occludins, these residues might play a similar role in homomeric interactions. The lack of sequence or motif similarity between the different protein families indicates that, if they did evolve from a common ancestral gene, they have diverged considerably to fulfill separate, different functions.

When their full-length amino acid sequences are compared, Inxs display relatively low overall identity to either Panxs or Cxs; however, there is greater identity or similarity between Inxs and Panxs when only the first halves of the molecules (the first two TMSs and their extracellular linker (EC1)) are compared (a pair of cysteinyl residues in EC1 is for example absolutely conserved in all Inxs and Panxs but the latter do not possess the YY(X)W(Z) motif in TM2 regarded as a signature sequence of innexins, see [2]. Invertebrate Cxs share 25–40% sequence identity with human Cxs [5]. Twenty and twenty-one members of the Cx gene family are likely to be expressed in the mouse and human genome, respectively (19 of which can be grouped into sequence-orthologous pairs) and orthologues are increasingly characterised in other vertebrates; in invertebrate chordates, a comparable number (e.g. seventeen connexin-like sequences in a basal marine chordate, the tunicate Ciona intestinalis) have been found. The Inx family appears large since well over 50 sequences have already been reported (as for example 25 in C. elegans) but functional studies of cell–cell communication have only been performed for some of them (see [2]). In contrast, only 3 Panx genes have been described in mouse and human and, up to now, both the presence of Panxs in ultrastructurally defined gap junctions as well as the in vivo existence of Panx-built canonical intercellular channels remain to be shown. In vitro Panx1, alone and in combination with Panx2, however induced the formation of intercellular channels in paired Xenopus oocytes [6]. Given the fact that the N-terminal halves of the gap junction proteins are better conserved than the C-terminal halves, Yen and Saier [4] suggested that the former segments might share an essential, universal function while the latter segments could have diverged for more specialised functions.

A major difference between pannexins and both innexins and connexins is the presence of glycosylation sites in the pannexin extracellular loops [7]. Presumably, such glycosylation not only plays a role in trafficking of Panx1 to the membrane, but also this glycosylation poses a steric barrier to formation of pannexon linkage across extracellular space. Thus, the role of pannexin channels is most likely to involve exchange from extracellular space, rather than between cells (see [8–11]).

4. Protein–protein interactions

4.1. Interactions of connexins with adhesion junction components

Adherens junctions (AJs) mediate adhesion between neighbouring cells by linking the actin cytoskeleton of one cell to that of the next cell via transmembrane adhesion molecules and their associated protein complexes. The core of these junctions consists of two basic adhesive units, the interactions among transmembrane glycoproteins of the classical cadherin superfamily and the catenin family members (including p120-catenin, β-catenin, and α-catenin) and the nectin/afadin complexes (for review, see [12]). Their formation, as that of gap junctions, requires close membrane–membrane apposition, and durable interactions between AJ and gap junction (GJ) components have been summarized in Table 1. Cadherins comprise an important family of transmembrane glycoproteins that mediate calcium-dependent cell–cell adhesion and are linked to the actin cytoskeleton via catenins. In NIH3T3 cells, Cx43, N-cadherin and different N-cadherin-associated proteins were found colocalized and coimmunoprecipitated, suggesting that Cx43 and N-cadherin are coassembled in a multiprotein complex containing various N-cadherin-associated proteins [13]. However, no evidence was found in the latter study for direct binding between N-cadherin and the C-terminal part of Cx43, suggesting that weak protein–protein interactions might exist between them, or that interactions occur with the short N-terminus or intracellular loop domains of Cx43 or via a protein partner acting as an anchoring bridge. Catenins, which anchor cadherins to the actin cytoskeleton, were found co-localized and coimmunoprecipitated with Cx43 in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes [14,15]. In the latter study, β-catenin was suggested to associate with α-catenin, ZO-1 and Cx43 during gap junction development. In contrast, Cx45 and β-catenin do not have a direct association to each other in mouse heart [16].

Table 1.

Reported interactions of gap junction proteins with anchoring junction components

| AJ protein | Cx | Main approachesa | Cell typesb | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-catenin | Cx43 | cl ci | Neonatal rat cardiomyocyte, N2A cells | [14] |

| β-catenin | cl ci | NIH 3T3 cells | [13] | |

| p120 | cl ci | NIH 3T3 cells | [13] | |

| N-cadherin | cl ci | NIH 3T3 cells | [13] |

cl: colocalization; ci: co-immunoprecipitation.

In roman characters, cells where Cx were endogenously expressed; in italics, cells where Cx were exogenously expressed, surexpressed or mutated.

4.2. Interactions of connexins with tight junction components

Tight junctions (TJs), the most apical organelle of the apical junctional complex, primarily involved in the regulation of paracellular permeability and membrane polarity, are built from about 40 different proteins, including members from multigenic families. These proteins include three main transmembrane proteins (claudins, occludin, and junctional adhesion molecules, JAMs), as well as cytoplasmic proteins fulfilling roles in scaffolding, cytoskeletal attachment, cell polarity, signalling, etc. (see [17–20]). Up to now, connexin interaction with JAMs has not yet been reported, but several interactions of the other TJ components have been observed, summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reported interactions of gap junction proteins with tight junction components

| TJ protein | Via its | Cx | Cx motif | Main approachesa | Cell typesb | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZO-1 | PDZ-2 | Cx30 | cl ci at | Mouse brain and spinal cord | [95] | |

| PDZ-2 | Cx31.9 | The most C-terminal residues | cl ci | HEK 293 cells | [38] | |

| Cx32 | cl ci | Cultured rat hepatocytes | [22] | |||

| PDZ-1 | Cx35 | Last 15 a.a. of C-terminus | cl ci at | Goldfish hindbrain | [45] | |

| PDZ-1 | Cx36 | Four C-terminal residues (SAYV) | cl ci em at | Mouse brain, HeLa cells | [43] | |

| PDZ-1 | A 14-residue C-terminal fragment | cl ci at | HeLa cells, βTC-3, mouse pancreas and adrenal gland cells | [44] | ||

| cl ci | PC12 cells | [118] | ||||

| Cx40 | cl ci | Porcine vascular endothelial cells | [24] | |||

| PDZs | Cx43 | C-terminal 5 residues | cl ci at | HEK 293 cells, rat cardiomyocytes | [55] | |

| PDZ-2 | Extreme C-terminal | cl ci dh | COS-7, Rat-1, mink lung epithelial cells | [56] | ||

| PDZ-2 | C-terminal 5 residues | cl ci em | Rat adult ventricular myocytes | [119] | ||

| cl ci | 42GPA9 cells, rat testis lysates | [120] | ||||

| PDZ-2 | C-terminal | ci at | C57B16 mouse cortical astrocytes | [121] | ||

| PDZ-2 | Last 19 C-terminal residues | nmr | [35] | |||

| PDZ-2 | C-terminal (residues at the -3 position) | cl ci dh | MDCK cells | [37] | ||

| PDZ-2 | cl ci at | Mouse brain and spinal cord | [95] | |||

| PDZ-2 | C-terminal (amino acids 374–382) | cl at | HeLa cells, rat cardiomyocytes | [52] | ||

| cl ci | Porcine vascular endothelial cells | [24] | ||||

| PDZ-2 | cl ci | NRK and HEK293 cells | [98] | |||

| cl ci | Newborn rat ventricular myocytes | [53] | ||||

| Cx43, Cx45 | cl ci at | ROS 17/2.8 cells | [48,122] | |||

| PDZs | Cx45 | Four C-terminal residues (SVWI) | cl ci dh | MDCK cells | [39] | |

| PDZs | 12 most C-terminal residues | cl ci at | ROS 17/2.8 cells | [57,123] | ||

| PDZ-2 | cl ci em at | HeLa cells | [29] | |||

| PDZ-2 | Cx46, Cx50 | Most C-terminal residues | cl ci | Mouse lens | [40] | |

| PDZ-2 | Most C-terminal residues | cl ci em at | Mouse lens | [42] | ||

| PDZ-2 | Cx47 | cl ci em at | Mouse brain, HeLa cells | [41] | ||

| ZO-2 | Cx43 | C-terminal end | at | NRK cells | [124] | |

| PDZ-2 | Cx43 | C-terminal end | cl ci at | NRK, HEK 293T cells, heart tissues | [125] | |

| ZO-3 | PDZs | Cx45 | C-terminal 4 residues | cl ci dh | MDCK cells | [39] |

| Occludin | Cx26 | at | Human intestinal cell line T84 | [23] | ||

| Cx40, Cx43 | cl ci | Porcine vascular endothelial cells | [24] | |||

| Cx32 | cl ci | CHST8 cells | [21] | |||

| cl ci | Cultured rat hepatocytes | [22] | ||||

| Claudin-1 | Cx32 | cl ci | Cultured rat hepatocytes | [22] | ||

| Claudin-5 | Cx40, Cx43 | cl ci | Porcine vascular endothelial cells | [24] |

bt: biochemical techniques (cell-free assays, chimeras, truncated connexins, mimetic peptides, oligomerization assays, chemical cross-linking tests, etc); cl: colocalization; ci: co-immunoprecipitation; dh: double hybrid; em: electron microscopy immuno labelling: at: affinity techniques (pull-down, affinity binding assays, surface plasmon resonance); nmr: nuclear magnetic resonance.

In roman characters, cells where Cxs were endogenously expressed; in italics, cells where Cxs were exogenously expressed, surexpressed or mutated.

Occludin was found to interact with Cx32 in immortalized mouse hepatocytes [21] and cultured rat hepatocytes [22]. Nusrat et al. [23], using a bait interaction system, reported that Cx26 interacted with a coiled-coil domain of occludin. This suggests that Cx26 retains the ability to interact with occludin in some cell systems, although in other cultured systems this interaction may not be physiological. Claudin-1 was found co-localized with Cx32, occludin and ZO-1 at cell borders of primary cultured rat hepatocytes, and binding of Cx32 to the tight-junction proteins was demonstrated by coimmunoprecipitation [22]. Both occludin and claudin-5 (and ZO-1, see below) were shown to colocalize and to coprecipitate with Cx40 and Cx43 in porcine blood-brain barrier endothelial cells [24].

In the different junctional complexes, adaptor proteins, which possess a modular organization with several protein–protein interaction domains, usually bind to the cytoplasmic C-terminal tail of transmembrane proteins and connect them to the actin cytoskeleton directly or indirectly by recruiting other proteins. Zonula occludens (ZO) proteins, in addition to the characteristic modules of the MAGUK protein family (PDZ, SH3 and GUK domains), have a distinctive C-terminus comprising acidic- and proline-rich regions, and splicing domains. ZO-1, a 220 kDa peripheral membrane protein, tethers transmembrane proteins either directly (e.g. occludin, claudins and JAMs) or via their adapter proteins (α-catenin or afadin for example) to the actin cytoskeleton (for recent reviews, see for example [18,19,25,26]. The growing number of connexins that can associate with ZO proteins, summarized in Table 2 (see also [27]), indicates that the latter may play a more general role in organizing gap junctions and/or in recruiting signalling molecules that regulate intercellular communication. Up to now, all Cxs that have been shown to interact with ZO-1 belong to the alpha connexin isotypes, leading to the speculation that other connexin isotypes (betas, gammas, etc) may have alternate scaffolding partners.

Coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor (CAR) is a transmembrane TJ protein associated with ZO-1 [28], well conserved in vertebrates but its function remains poorly understood. CAR is, in the postnatal heart, predominantly localized at the intercalated disc and also present in the atrioventricular (AV) node. CAR interacts with Cx45 and they form a complex with ZO-1 and β-catenin [16].

5. Possible structural domains of connexins involved in interactions with partner proteins of Apical Junctions

ZO proteins are at the centre of a network of protein interactions, linked to the actin cytoskeleton via their C-termini whereas their N-termini interact with the C-terminal regions of different transmembrane junctional proteins (claudins, occludin, JAM and connexins) via different docking modules. The first N-terminal PDZ domain of ZO-1, ZO-2 and ZO-3 directly binds to the C-termini of claudins, the third PDZ domain of ZO-1 interacts in vitro with JAM-1 whereas the GUK region of ZO-1 is responsible for occludin interaction (see [18]). ZO-1 also directly interacts with α-catenin and afadin (see [25]). Except Cx35 and -36, which appear to interact with PDZ1 of ZO-1, connexins mainly interact with PDZ2 of ZO-1 and, to a lesser extent, ZO-2; up to now, only Cx45 has been found to interact with ZO-3 (see Table 2). Cx36 and Cx45 binding to different ZO-1 PDZ domains (respectively PDZ1 and PDZ2, see Table 2). Li et al. [29] suggested that ZO-1 might simultaneously interact with Cx36 and Cx45 in a tripartite manner, thereby tethering the two Cxs within gap junctions. As ZO-1 can target to the periphery of Cx43 junctional plaque independently of PDZ2-mediated interactions, Hunter and Gourdie [30] put forward a targeting sequence that would initially involve ZO-1 bound to junctional complexes (possibly N-cadherin-based) adjacent to GJs, followed by a transfer of ZO-1 and its direct engagement with Cx43 at GJ edges.

The C-terminus region of Cxs(adomain of 156aminoacids in Cx43 for example) is not required for the formation of functional channels but is critical for GJICmodulation. Itpresents several potentialphosphorylation sites for different protein kinases, and modifications in the phosphorylation status of tyrosine, serine, or threonine residues have been reported to affect, in one way or another, GJIC (see for example [31–33]).

Different cytoplasmic domains of connexins appear involved in interactions with partner proteins and may mutually influence one another. The interaction between the extreme C-end of Cx43 for example with ZO-1 via the second, but not the firs t, PDZ domain (seeTable 2) seems influenced by c-Src [34], see also [35]. Cx43/v-Src associations are mediated by interactionsbetween theSH3domain of v-Src and a proline-rich region of Cx43 and by the SH2 domain of v-Src and tyrosine 265 of Cx43 [36], and it has been suggested that such interaction might induce a structural change in the C terminal region of Cx43, thereby hindering the interaction between Cx43 and the ZO-1 PDZ-2 domain [34]. Jin et al. [37] suggested that Cx43 interaction with this domain might take place through a typical Class II PDZ binding domain. NMR titration experiments determined that the ZO-1 PDZ-2 domain affected the last 19 amino acid residues (a.a.) of the C-terminus of Cx43 [35].

Jin et al. [37] emphasized the fact that, in contrast to Cx32, Cx31.9, Cx43, Cx46 and Cx50 exhibit similar ZO-1-PDZ2-binding motifs (D-L-X-I) in their C-terminus. Cx31.9 [38], Cx45 [39], Cx46 [40], Cx47 [41] and Cx50 [42] interact with ZO-1 via their C-terminus whereas Cx36 [43,44] and Cx35 [45] bind PDZ-1 of ZO-1; Cx35 and Cx36 indeed, in contrast with the first connexin group, contain the C-terminus a.a. YV, the binding motif domain present in the C-terminus of most of the claudins and reported to be responsible for their interaction with the PDZ-1 domain of ZO-1, ZO-2 and ZO-3 [46]. A domain of 14 C-terminal a.a. (and particularly the last 4 ones, SAYV) of the Cx35 and Cx36 sequences appear required for their interaction with the PDZ-1 domain of ZO-1 since a 14 a.a. peptide corresponding to this region showed binding capacity to the PDZ-1 domain of ZO-1 and behaved in vitro as a competitive inhibitor of Cx36/ZO-1 [44] or Cx35/ZO-1 [45] interaction whereas a 10 a.a., with the same sequence except lacking the 4 a.a. forming the PDZ binding motif did not [45]. Sequence analysis and immunocytochemical data suggested that Cx36 might directly interact with ZO-2 at mouse retinal gap junctions; however, an indirect association, via a partner protein (e.g. ZO-1) remained possible [47]. As ZO-1 was able to bind to a truncated Cx45 protein lacking the canonical PDZ binding domain present at the C-tail, Laing et al. [48] suggested that Cx45 may have a large and complex binding site for ZO-l, comprising the residues between a.a. 357 and the Cx45 C-terminus, an alternative possibility being the existence of 2 distinct binding sites, one involving the C-tail and the second the amino acids proximal to amino acid 360. The authors however did not exclude either the possibility of an artefactual ZO-1/Cx45 binding or of an indirect interaction (e.g. an association of Cx45 with Cx43 bound to ZO-1). An indirect interaction was also proposed for the formation of CAR/Cx45 protein complex [16]. The cytoplasmic domains of both proteins possess PDZ-binding motifs able to link PDZ-domain-containing proteins such as ZO-1. The four C-terminal residues (SVWI) of Cx45 and the PDZ-binding domain (ITVV) of CAR appear required for this interaction [16].

Several other apical junction proteins such as cadherins, the major transmembrane protein of AJs, are indirectly linked to ZOs through protein linkages, for example via α-catenin, which establishes linkages between the cadherin/β-catenin complex and the actin cytoskeleton via adapter proteins (e.g. ZOs) (for recent review, see [12]). α-catenin appears to interact with the SH3-hinge-GUK region of ZO-1 as well as with ZO-2 with the N-terminus of ZO-2 (see [26]). In vitro, ZO-1 and ZO-3 bind F-actin via their proline rich C-termini but ZO-2 would not directly interact with actin (see [26]).

6. Physiological importance of protein–protein interactions in intercellular junction functions

6.1. Reciprocal influence of GJs and AJs in their respective formations

A number of studies have indicated that formation of gap junctions and of anchoring junctions are intimately linked: Meyer et al. [49] observed in Novikoff cells that antibodies directed against either extracellular domain of Cx43 or N-cadherin prevented both gap junction and adherens junction formation. The clustering of cell surface proteins is routinely assumed to be due to relatively static interactions with scaffolding proteins that in turn are attached to cytoskeletal components.

6.1.1. Importance of scaffolding proteins

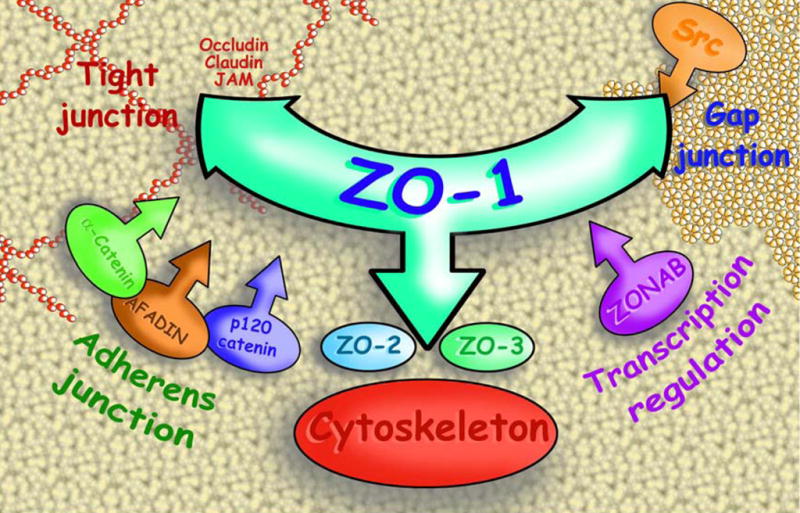

Cytoplasmic scaffold proteins appear to play key roles in the assembly of membrane specialised areas (e.g. cellular junctions, channel or receptor clusters, etc), organizing membrane proteins into specialised membrane domains (Fig. 1). Cytoskeletal-based perimeter fences were for example seen to selectively corral a membrane-protein sub-population of potassium channels (Kv2.1 channels) to generate stable 1–3 μ2 clusters [50]. These authors noticed that despite the stability of these microdomains, the channels retained within the cluster perimeter were surprisingly mobile, showing that the clustering did not result from a static scaffolding-based structure. Connexin channels clustered in gap junctional plaques share these characteristics, where ZO-1 is preferentially localized at the periphery of the plaques [51–53], suggesting that a ZO-1-actin perimeter fence could selectively corral gap junction channels. G protein signalling cascades have emerged as one of the primary cellular mechanisms for controlling membrane channels, and RhoA was recently seen to dynamically modulate the permeability of Cx43-made channels presumably via its pivotal role in regulating the actin cytoskeleton since its stabilization by phalloidin markedly reduced the consequences of RhoA activation or inactivation. The last ones were accompanied by alterations in the Cx43/ZO-1 interactions [53].

Fig. 1.

Artistic overview of the importance of adaptors (particularly ZO-1), which play pivotal roles in the protein–protein interactions between gap junction and apical junction components and actin cytoskeleton.

As ZO-1 interacts with both occludin and different Cxs, for example Cx32, chimeras were created by combining C-terminal end of occludin with transmembrane portions of Cx32, and such chimeras were able to localize with ZO-1-containing cell contacts, suggesting an important role for cytoplasmic proteins in the targeting of these chimeras to the appropriate membrane subdomain [54].

ZO-1 was suggested to provide a docking that temporarily secures the different connexins in gap junction plaques at the cell–cell boundary [55–57]. The overexpression of the N-terminal domain of ZO-1, which lacked the ability to localize at cell–cell interfaces, disrupted the transport of Cx43-FLAG to the target site [55]. The level of incorporation of Cx43 lacking the ZO-1 binding domain into the cell surface was however reduced by about 30–40% compared to wild-type Cx43 in cardiac myocytes [34] and also markedly reduced in mice fibroblasts whereas significant levels of truncated Cx43 were observed within the cell cytoplasm [58]. These observations show that the Cx43–ZO-1 interaction is important although not indispensable for the formation of functional Cx43 channels. The reduction of Cx43–ZO-1 interaction significantly increased the size of Cx43 plaques [52,59] with, in the latter study, a concomitant reduction in their overall number.

6.1.2. GJ formation depends on the assembly of anchoring junctions

The assembly of adherens junction proteins (particularly of N-cadherin, α-catenin and β-catenin) was observed at cell contacts before Cx43 formed gap junctions [60,61] and seems to be a prerequisite for subsequent GJ formation [61]. The latter authors suggested that cell-to-cell contact sites made by cadherin–catenin complexes as well as tight junctional strands may then act as foci for gap junction formation. The influence of cadherins in gap junction formation however might be context or cell-type dependent, the expression of exogenous cadherin investigated for example in mouse L and rat Morris hepatoma cells inhibited GJIC in the first case but enhanced it in the second [62]. In cardiomyocytes of new-born rat, intracellular applications of β-catenin, α-catenin or ZO-1 perturbed the formation of the catenin–ZO-1–Cx43 complex and inhibited the Cx43 transport to the plasma membrane and the assembly of gap junction plaques [15]. Normal cardiac functions depends on the proper organization of the different junctional complexes to mediate mechanical and electrical coupling between individual myocytes, and varied defects in intercalated disc proteins are linked to different cardiac arrhythmias in human and animal models (for review, see [63]).

In a α-catenin-deficient prostate cancer cell line, the forced expression of α-catenin not only triggered the trafficking and assembly of Cx32 and −43 into gap junctions but also recruited ZO-1 to the cell surface [64]. Antibody-mediated disruptions of cadherin-containing cell adhesion contacts altered GJIC; for example, antibodies directed against N-cadherin prevented gap junction formation in embryonic chick neuroectoderm [65] or lens [66] cells, whereas antibodies to E-cadherin interrupted GJIC between cultured terato-carcinoma PCC3 cells [67]. Both deletion of the N-cadherin gene in mouse [68] and transfection of dominant negative N-cadherin cDNA into adult rat cardiomyocytes [60] disrupted cardiac gap junctions. Given that N-cadherin and catenins are assembled into cadherin–catenin complexes in the endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi compartments, prior to localization at the plasma membrane [69], this raises the possibility that Cx43 is assembled as part of a multi-protein complex that may coordinately regulate adherens and gap junction assembly [13].

In corneal epithelial cells, the presence of E-cadherin was not a prerequisite for the assembly of Cx43 gap junctions [70] whereas in mouse epithelial cells stable transfection of E-cadherin cDNA increased GJIC [71]. Adherens junctions formed by E-cadherin were suggested to trigger actin cable formation, allowing the transport of both Cx26 and Cx43 to the plasma membrane of murine skin papilloma cells [72]. In rat cardiomyocytes, intracellular application of antisera against α- or β-catenin prevented Cx43 targeting to the plasma membrane and the formation of GJ plaques, suggesting that binding of catenins to ZO-1 would be required for Cx43 transport to the plasma membrane during the assembly of gap junctions [15]. In the mouse early embryo, cell contact asymmetry, required for TJ biogenesis, appeared to provoke a spontaneous decrease in GJIC [73].

The assembly of adherens junctions was found to trigger a dramatic decrease in RhoA activity and a stimulation of Rac1 and Cdc42 activity [74,75] suggesting that, in cardiac myocytes, the localization of Cx43 was determined through the Rac1 pathway downstream of N-cadherin. In rat cardiac myocytes for example, RhoA activity dynamically modulates the permeability of Cx43-made channels since RhoA activation markedly enhanced the cell-to-cell diffusion of a fluorescent dye whereas opposite effects was observed after specific RhoA inhibition [53]. Rho GTPase being known to be downstream signal transducers of cadherins [76], cadherins could influence GJIC via this pathway.

6.1.3. AJ formation depends on the assembly of GJs

Chung et al. [77] observed, in cultured Sertoli cells, that a transient induction of Cx33 coincided with an induction of N-cadherin expression. After blockage of the connexin functions using a Cx31 and Cx33 pan-connexin peptide, an induction and dys-localization of N-cadherin were observed [78]. In mouse hepatocytes derived from Cx32-deficient mice, the expression of exogenous Cx32 induced the formation and functions of TJ whereas the expression of Cx26, Cx43 or C-tail truncated Cx32 had no effect [79]. An up-regulation of membrane-associated guanylate kinase with inverted orientation-1 (MAGI-1, a TJ protein) caused by Cx32 protein expression and/or Cx32-mediated GJIC was observed by Murata et al. [80], and these authors suggested that MAGI-1 might act as a scaffold protein for both adherens and tight junctions. During early embryo development, the initiation of GJIC coincides with the initiation of TJ membrane assembly at compaction but however Eckert and Fleming [81] did not find evidence supporting the notion that GJIC may be involved in regulating de novo TJ biogenesis at this stage.

6.2. Reciprocal influence of GJs and AJs in their respective functions

6.2.1. Connexin expression affects barrier and fence functions of tight junctions

Connexin expressions (particularly the ones of Cx26 and Cx32) influence the structure and/or functions of different TJs, as summarized in Table 3. Transfection of Cx32 into immortalized mouse hepatocytes derived from Cx32-deficient mice was associated with the induction of TJ strands and of the integral proteins occludin, claudin-1, and ZO-1, strengthening the TJ functionality [79]. The 18α-glycyrrhetinic acid (AGA)-induced disruption of GJIC between Cx26-transfected Caco-2 cells resulted in an increase in paracellular permeability of the cell monolayer, suggesting that reduced paracellular permeability in the Cx26 transfectants, via claudin-4 up-regulation, was mainly due to enhanced GJIC [82]. In Calu-3 cells, the expression of claudin-14 was significantly increased in Cx26 transfectants compared to parental cells, and in some cells, Cx26 was co-localized with claudin-14. However, in this cell type, GJIC uncouplers (AGA or oleamide) did not affect the changes induced by Cx26 transfection, suggesting that Cx26 expression, but not the mediated intercellular communication, may regulate tight junction barrier and fence functions [83,84]. In different brain and lung endothelial cell types, the same GJIC uncouplers also inhibited the barrier function of tight junctions, findings suggesting that Cx40- and/or Cx43-based GJs might be required to maintain the endothelial barrier function without altering the expression and localization of the tight-junction components analyzed (namely occludin, claudin-5, ZO-1, JAM-A,-B or -C [24]).

Table 3.

Reported effects of the expression of connexins on the structure and/or functions of tight junctions

| Connexin | Action | TJ protein | Effects on |

Cell types | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein expression | Barrier functiona | Ouabain effectsb | |||||

| Cx26 | Expression | Claudin-4 |

|

|

Caco-2 cells | [83] | |

| Expression | Claudin-14 |

|

P | Calu-3 cells | [84] | ||

| P | [85] | ||||||

| Cx32 | Expression | Occludin, Claudin-1, Claudin-2, MAGI-1 |

|

|

Cx32-deficient hepatocytes | [20] | |

| Expression | Occludin, Claudin-1, Claudin-2, MAGI-1 |

|

|

Cx32-deficient hepatocytes | [21] | ||

| Expression | Occludin, Claudin-1, ZO-1 |

|

|

Cx32-deficient hepatocytes | [80,85] | ||

| Expression | Occludin, Claudin-1 |

|

Cx32-deficient hepatocytes (CHST8 and Cx32KOH) | [126] | |||

| Expression | Occludin, Claudin-1, Claudin-2, MAGI-1 |

|

|

Cx32-deficient hepatocytes | [81] | ||

An increase in the barrier function of tight junctions corresponds to either an increase in transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) or a lowered paracellular flux of a solute.

P: protect disruption of barrier and fence functions of TJs by the Na+/K+-ATPase inhibitor ouabain.

A pan-connexin peptide corresponding to the extracellular binding domain of testis Cxs (Cx31 and Cx33), able to impede the formation of functional intercellular channels, caused a disintegration of occludin-associated protein complexes [78]. The fact that the level of N-cadherin at the basal seminiferous epithelium remained relatively unaffected suggested that these connexins are immediate and preferential regulators of occludin-based TJ instead of N-cadherin-based AJ at the sites of blood-testis barrier see [85]. In contrast, in a 42GPA9 Sertoli cell line assay, lindane (gamma-hexachlorocyclohexane, a lipid-soluble pesticide that exerts carcinogenic and reprotoxic effects) abolished GJIC and dislocated GJ plaques of Cx43 without modification of occludin localization [86].

In interleukin-1β-treated primary human astrocytes, upregulation of claudin-1 was accompanied with down regulation of Cx43 and occludin, suggesting a reciprocal relationship between GJ and TJ proteins [87]. When human nasal epithelial (HNE) cells are cocultured with primary human nasal fibroblasts in a non-contact system, a differentiation of HNE cells occurred, accompanied by a down-regulation of Cx26 and an upregulation of Cx30.3 and Cx31, together with the development of extensive GJIC. This switch in connexin expression was accompanied by an increase in claudin-1, claudin-4, occludin and ZO-2 expression [88]. Mice lacking either Cx37 or Cx40, the predominant gap junction proteins present in vascular endothelium, are viable and exhibit phenotypes that are largely non-blood vessel related but animals lacking both Cx37 and Cx40 display severe vascular abnormalities, with localized hemorrhages in skin, testis, gastrointestinal tissues, and lungs, and die perinatally [89]. These studies suggest that the expression of these connexins plays a major role in establishing and maintaining the paracellular permeability barrier. Rapid mobilization of leucocytes through endothelial and epithelial barriers, a key in immune system reactivity, is a complex multistep process, which includes leucocyte tethering, rolling, tight adhesion and extravasation (see for example [90]). Once activated, leucocytes migrate to the junctional region; their extravasation or diapedesis via paracellular transmigration requires rapid opening and closing of intercellular junctions, essential to maintain the integrity of the epithelial barrier. These processes are regulated by adhesion molecules such as PECAM-1 (platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1), CD99, VE-cadherin (vascular endothelial cadherin) and JAMs (see [90]). The establishment of GJIC between activated leucocytes and endothelial cells, allowing a heterocellular communication, would be critical for the adhesion and extravasation of leucocytes [91]. Heterocellular GJIC between breast tumor cells and endothelial cells was also shown to up-regulate diapedesis of tumor cells [92].

6.2.2. Connexin expression affects other functions of apical junction components

The armadillo repeat protein β-catenin is recognized as a component of functional adherens junctions and an intermediate in the “canonical Wnt signalling pathway”, activating the transcription of crucial target genes responsible for cellular proliferation and differentiation. The expression of the mammary Cxs and their association with α, and β-catenins and ZO-2 proteins to form functional GJs was for example found to be crucial for mammary epithelial cell differentiation as monitored by β-casein expression since protein complex in heterocellular cultures would indeed recruit β-catenin and inhibit its entry to the nucleus favouring a differentiated phenotype (see [93]).

The transcription factor ZO-1-associated Nucleic Acid Binding protein (ZONAB), the canine homologue of mouse Y-box transcription factor 3 (MsY3) and of human DbpA (an E2F target gene found overexpressed in different carcinomas), is known to associate with SH3 domains of ZO-1. The binding of ZONAB to ZO-1 results in its membrane sequestration at intercellular junction level (see [94]) and hence the inhibition of its transcriptional activity. As MsY3 co-localizes with oligodendrocytic Cx47 and Cx32 as well as with astrocytic Cx43 [95]) and with Cx36 in mouse retina [47]), such sequestration of ZONAB would inhibit its transcriptional activity.

6.2.3. Apical junctions affect GJIC

Nectins first form cell–cell adhesions, which then induce, via the activation of small GTPases (Rap1, Cdc42 and Rac), a reorganization of the underlying actin cytoskeleton, which then recruits cadherins to the nectin-based cell–cell adhesion sites. Moreover, during or after the formation of AJs, nectins recruit, first, JAM and then claudin and occludin to the apical side of AJs in cooperation with cadherin, which results in the formation of TJs (see [96]).

In tumorigenic mouse sarcoma cells (S180), which do not express the Ca2+-dependent liver cell adhesion molecule (L-CAM), fluorescent dye microinjected into cells virtually did not spread to adjacent cells, but after cells were transfected with cDNA for L-CAM, an extensive cell-to-cell dye diffusion was observed [97]. In chick neuroectoderm, Keane et al. [65] noticed that the differentiating cells formed discrete fields of expression, where fields of junctional communication correlated with fields of Neural-CAM (N-CAM) expression. The fact that in primary human astrocytes, GJ and TJ proteins seem inversely regulated by interleukin-1β suggests that, in pathological conditions, increases of this proinflammatory cytokine might alter astrocyte-to-astrocyte connectivity [87].

The extent of GJIC is a direct measurement of the number and functionality of GJ channels, influenced by a number of factors as transcriptional control, post-transcriptional modifications (e.g. phosphorylation) and rapid degradation of Cxs by both the proteasomal and lysosomal systems. In NRK and HEK293 cells, proteasome inhibition resulted in a reduction of Cx43–ZO-1 association and an accumulation of Cx43 forming large GJ plaques at plasma membranes, and Girao and Pereira [98] hypothesized that proteasome inhibition could prevent Cx43–ZO-1 interaction by preventing degradation of a putative Cx43-interacting protein. In rabbit lens epithelial cells, ZO-1 down-regulation resulted in loss of dye transfer activity without altering the total amount of Cx43 protein in the cells, as if aggregated Cx43 gap junction channels were not able to transfer dye without ZO-1 located in the specific “ring” arrangement around the plaque [99].

7. Physiological consequences of reciprocal GJs/AJs influences on cell functions

Interconnection of individual cardiac cells through gap junction channels plays a pivotal role for the velocity and the safety of impulse propagation in cardiac tissues. Most of the intercellular channels are packed at the ends of cardiac myocytes in intercalated discs, where gap junction plaques are intertwined with adherens junctions, desmosomes and CARs. CAR expression is essential for early cardiac development (CAR-null mice die in utero with cardiac defects (see [100]) and it remains robustly expressed in adults [101]. CAR presence is essential to maintain normal AV conduction [16,102]. In the latter study, authors suggested that, given the difference in morphology between AV-nodal cells and myocardial cells, CAR and ZO-1 protein complex is required to localize Cx 45 to the cell–cell junction of AV-nodal tissue but that they are not required for localization of Cx40 and −43 in the intercalated disc. Coxsackieviruses and adenoviruses are the pathogens most commonly associated with inflammatory heart disease; the fact that these viruses have evolved independently to interact with a receptor normally inaccessible from the epithelial surface is not unprecedented: JAMs were also identified as receptors for mammalian reoviruses [103].

In the gap junction remodeling observed after human heart failure, ZO-1 (specifically localized at the intercalated discs) was up-regulated in parallel with the reduced expression of Cx43, and these changes were accompanied by an increase in the proportion of Cx43 interacting with ZO-1 [104].

In adherens junctions (see [12]), transmembrane proteins (particularly N-cadherins) link actin cytoskeletons via intracellular linker proteins (e.g, plakoglobin, γ-catenin, β-catenin, and α-actinin) whereas desmosome transmembrane molecules (desmocollins and desmogleins, members of the cadherin family) are linked to the intermediate filaments (mainly desmin in cardiac myocytes) by desmoplakin and the armadillo proteins plakoglobin and plakophilin (see [105]). Adherens junctions appears to nucleate GJs, and disruption of mechanical coupling has been suggested to lead, via the loss of GJIC, to different cardiomyopathies [106,107]. Mutations in genes encoding different desmosomal proteins (plakoglobin, desmoplakin, plakophilin 2 and desmoglein 2) have for example been identified in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (see [108] for references). Cardiac-specific deletion of N-cadherin led to alteration in Cx40 and Cx43, disassembly of the intercalated disc structure and conduction slowing and arrhythmogenesis in adult mice [109,110]. As ectopic expression of cadherins is associated with changes in tumor cell behaviour and pathology, Ferreira-Cornwell et al. [111] examined the effect of expression of either E-cadherin or N-cadherin in the heart of transgenic mice. Misexpression of E-cadherin led to cardiomyopathy, with earlier onset and increased mortality compared with N-cadherin mice, with a dramatic decrease in Cx43. Silencing of plakophilin 2 expression with siRNA resulted in cardiomyocytes of new-born rat in a drastic loss of Cx43 gap junction plaques, a significant redistribution of Cx43 and a decrease in intercellular dye coupling [112]. Structural and functional links via tight and gap junction were suggested to be temporarily established between heterologous cell types, for example between axon and regenerating Schwann cells, during mammalian peripheral nerve regeneration [113].

The exact mechanisms mediating these sorts of molecular crosstalk remain to be identified but have important consequences to the synchronization of different cellular events; it was for example observed that Cx43 or N-cadherin knockdown similarly inhibited cell motility of NIH3T3 cells [13]. N-cadherin and Cx43 were proposed to modulate neural crest cell motility by engaging in a dynamic crosstalk with the cell’s locomotory apparatus through p120-catenin signalling [114].

Interactions of gap junction proteins with proteins of other membrane junctions appear to have been conserved through evolution, between connexins and cadherins in vertebrates, between innexins and core proteins of adherens and septate junctions (the latter providing some of the functions ascribed to tight junctions in vertebrate tissues, see [115]). In the latter study, such interaction was suggested to play an essential role in epithelial morphogenesis.

8. Conclusions

Cell–cell-interactions play key roles in the regulation of tissue integrity, the generation of barriers between different tissues and body compartments. Intercellular junctional complexes are composed of the tight junctions or zonula occludens, the adherens junctions or zonula adherens, and desmosomes or macula adherens, whereas gap junctions provide for intercellular communication. There is an intimate spatial relationship between the different types of junctions. These different junctions, sharing common adaptor molecules, particularly ZO-1, frequently present intermingled relationships, the proteins coassemble into macromolecular complexes and their expressions are coordinately regulated.

A close membrane–membrane apposition is required for gap junction formation and maintenance. The structural alterations that are seen in cardiomyocytes from failing hearts reflect the importance of intercalated discs in the heart, where they are involved in both mechanical force transmission and intercellular communication, explaining the fact that in radical acute disease (such as sepsis), both these junctional types are disrupted (see [116,117]). In the heart, defects in cell–cell adhesion, or the presence of discontinuities between adhesion junctions and the cytoskeleton may, as recently emphasized by Saffitz [107], destabilize GJs, reducing electrical coupling and contributing to the high incidence of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death observed in these cardiomyopathies. In conclusion, gap junctions are not only structurally but also functionally associated with anchoring and tight junction structures.

Abbreviations

- 42GPA9

Sertoli cell line

- Caco-2

human colonic adenocarcinoma cells

- Calu-3

human airway epithelial cell line

- CHST8 cells

immortalized mouse hepatocytes

- COS7

monkey African green kidney cells

- HEK293 cells

human embryonic kidney 293 cells

- MDCK

epithelial Madin–Darby canine kidney cells

- Neuro2A

mouse neuroblastoma cells

- NIH 3T3

mouse fibroblasts

- NRK

rat kidney cells

- PC-12

a neuron-like cell line originally cloned from rat phaeochromocytoma cells

- ROS 17/2.8

osteosarcoma cell line

References

- 1.Phelan P, Bacon JP, Davies JA, Stebbings LA, Todman MG, Avery L, Baines RA, Barnes TM, Ford C, Hekimi S, Lee R, Shaw JE, Starich TA, Curtin KD, Sun YA, Wyman RJ. Innexins: a family of invertebrate gap-junction proteins. Trends Genet. 1998;14:348–349. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01547-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phelan P. Innexins: members of an evolutionarily conserved family of gap-junction proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1711:225–245. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panchin Y, Kelmanson I, Matz M, Lukyanov K, Usman N, Lukyanov S. A ubiquitous family of putative gap junction molecules. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R479–R480. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00576-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yen MR, Saier MH., Jr Gap junctional proteins of animals: the innexin/pannexin superfamily. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2007;94:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White TW, Wang H, Mui R, Litteral J, Brink PR. Cloning and functional expression of invertebrate connexins from Halocynthia pyriformis. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruzzone R, Hormuzdi SG, Barbe MT, Herb A, Monyer H. Pannexins, a family of gap junction proteins expressed in brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13644–13649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2233464100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boassa D, Ambrosi C, Qiu F, Dahl G, Gaietta G, Sosinsky G. Pannexin1 channels contain a glycosylation site that targets the hexamer to the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:31733–31743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702422200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Locovei S, Bao L, Dahl G. Pannexin 1 in erythrocytes: function without a gap. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7655–7659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601037103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Locovei S, Scemes E, Qiu F, Spray DC, Dahl G. Pannexin1 is part of the pore forming unit of the P2X(7) receptor death complex. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:483–488. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pelegrin P, Surprenant A. Pannexin-1 mediates large pore formation and interleukin-1beta release by the ATP-gated P2X7 receptor. EMBO J. 2006;25:5071–5082. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spray DC, Ye ZC, Ransom BR. Functional connexin “hemichannels”: a critical appraisal. Glia. 2006;54:758– 773. doi: 10.1002/glia.20429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niessen CM, Gottardi CJ. Molecular components of the adherens junction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:562–571. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei CJ, Francis R, Xu X, Lo CW. Connexin43 associated with an N-cadherin-containing multiprotein complex is required for gap junction formation in NIH3T3 cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19925–19936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412921200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ai Z, Fischer A, Spray DC, Brown AM, Fishman GL. Wnt-1 regulation of connexin43 in cardiac myocytes. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:161–171. doi: 10.1172/JCI7798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu JC, Tsai RY, Chung TH. Role of catenins in the development of gap junctions in rat cardiomyocytes. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:823–835. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim BK, Xiong D, Dorner A, Youn TJ, Yung A, Liu TI, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Wright AT, Evans SM, Chen J, Peterson KL, McCulloch AD, Yajima T, Knowlton KU. Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) mediates atrioventricular-node function and connexin 45 localization in the murine heart. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2758–2770. doi: 10.1172/JCI34777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiba H, Osanai M, Murata M, Kojima T, Sawada N. Transmembrane proteins of tight junctions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:588–600. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guillemot L, Paschoud S, Pulimeno P, Foglia A, Citi S. The cytoplasmic plaque of tight junctions: a scaffolding and signalling center. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:601–613. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paris L, Tonutti L, Vannini C, Bazzoni G. Structural organization of the tight junctions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:646–659. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krause G, Winkler L, Mueller SL, Haseloff RF, Piontek J, Blasig IE. Structural organization of the tight junctions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:631–645. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kojima T, Sawada N, Chiba H, Kokai Y, Yamamoto M, Urban M, Lee GH, Hertzberg EL, Mochizuki Y, Spray DC. Induction of tight junctions in human connexin 32 (hCx32)-transfected mouse hepatocytes: connexin 32 interacts with occludin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;266:222– 229. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kojima T, Kokai Y, Chiba H, Yamamoto M, Mochizuki Y, Sawada N. Cx32 but not Cx26 is associated with tight junctions in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. Exp Cell Res. 2001;263:193–201. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nusrat A, Chen JA, Foley CS, Liang TW, Tom J, Cromwell M, Quan C, Mrsny RJ. The coiled-coil domain of occludin can act to organize structural and functional elements of the epithelial tight junction. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29816–29822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002450200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagasawa K, Chiba H, Fujita H, Kojima T, Saito T, Endo T, Sawada N. Possible involvement of gap junctions in the barrier function of tight junctions of brain and lung endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:123–132. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyoshi J, Takai Y. Structural and functional associations of apical junctions with cytoskeleton. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:670–691. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartsock A, Nelson WJ. Adherens and tight junctions: structure, function and connections to the actin cytoskeleton. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:660–669. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hervé JC, Bourmeyster N, Sarrouilhe D, Duffy HS. Gap junctional complexes: from partners to functions. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2007;94:29–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen CJ, Shieh JT, Pickles RJ, Okegawa T, Hsieh JT, Bergelson JM. The coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor is a transmembrane component of the tight junction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:15191–15196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261452898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X, Kamasawa N, Ciolofan C, Olson CO, Lu S, Davidson KG, Yasumura T, Shigemoto R, Rash JE, Nagy JI. Connexin45-containing neuronal gap junctions in rodent retina also contain connexin36 in both apposing hemiplaques, forming bihomotypic gap junctions, with scaffolding contributed by zonula occludens-1. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9769–9789. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2137-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hunter AW, Gourdie RG. The second PDZ domain of zonula occludens-1 is dispensable for targeting to connexin 43 gap junctions. Cell Commun Adhes. 2008;15:55–63. doi: 10.1080/15419060802014370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laird DW. Connexin phosphorylation as a regulatory event linked to gap junction internalization and degradation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1711:172–182. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solan JL, Lampe PD. Connexin phosphorylation as a regulatory event linked to gap junction channel assembly. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1711:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moreno AP, Lau AF. Gap junction channel gating modulated through protein phosphorylation. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2007;94:107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toyofuku T, Akamatsu Y, Zhang H, Kuzuya T, Tada M, Hori M. c-Src regulates the interaction between connexin-43 and ZO-1 in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2001;19:1780, 1788 276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005826200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sorgen PL, Duffy HS, Sahoo P, Coombs W, Delmar M, Spray DC. Structural changes in the carboxyl terminus of the gap junction protein connexin43 indicates signaling between binding domains for c-Src and zonula occludens-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54695–54701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanemitsu MY, Loo LW, Simon S, Lau AF, Eckhart W. Tyrosine phosphorylation of connexin 43 by v-Src is mediated by SH2 and SH3 domain interactions. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22824–22831. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin C, Martyn KD, Kurata WE, Warn-Cramer BJ, Lau AF. Connexin43 PDZ2 binding domain mutants create functional gap junctions and exhibit altered phosphorylation. Cell Commun Adhes. 2004;11:67–87. doi: 10.1080/15419060490951781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nielsen PA, Beahm DL, Giepmans BN, Baruch A, Hall JE, Kumar NM. Molecular cloning, functional expression, and tissue distribution of a novel human gap junction-forming protein, connexin-31.9. Interaction with zona occludens protein-1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38272–38283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205348200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kausalya PJ, Reichert M, Hunziker W. Connexin45 directly binds to ZO-1 and localizes to the tight junction region in epithelial MDCK cells. FEBS Lett. 2001;505:92–96. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02786-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nielsen PA, Baruch A, Giepmans BN, Kumar NM. Characterization of the associationof connexinsandZO-1inthelens. CellCommun Adhes. 2001;8:213–217. doi: 10.3109/15419060109080726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li X, Ionescu AV, Lynn BD, Lu S, Kamasawa N, Morita M, Davidson KG, Yasumura T, Rash JE, Nagy JI. Connexin47, connexin29 and connexin32 co-expression in oligodendrocytes and Cx47 association with zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) in mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2004;126:611–630. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nielsen PA, Baruch A, Shestopalov VI, Giepmans BN, Dunia I, Benedetti EL, Kumar NM. Lens connexins alpha3Cx46 and alpha8Cx50 interact with zonula occludens protein-1 (ZO-1) Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:2470–2481. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X, Olson C, Lu S, Kamasawa N, Yasumura T, Rash JE, Nagy JI. Neuronal connexin36 association with zonula occludens-1 protein (ZO-1) in mouse brain and interaction with the first PDZ domain of ZO-1. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:2132–2146. doi: 10.1111/j.l460-9568.2004.03283.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li X, Olson C, Lu S, Nagy JI. Association of connexin36 with zonula occludens-1 in HeLa cells, betaTC-3 cells, pancreas, and adrenal gland. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;122:485–498. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0718-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Flores CE, Li X, Bennett MV, Nagy JI, Pereda AE. Interaction between connexin35 and zonula occludens-1 and its potential role in the regulation of electrical synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12545–12550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804793105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Itoh M, Furuse M, Morita K, Kubota K, Saitou M, Tsukita S. Direct binding of three tight junction-associated MAGUKs, ZO-1, ZO-2, and ZO-3, with the COOH termini of claudins. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1351–1363. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.6.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ciolofan C, Li XB, Olson C, Kamasawa N, Gebhardt BR, Yasumura T, Morita M, Rash JE, Nagy JI. Association of connexin36 and zonula occludens-1 with zonula occludens-2 and the transcription factor zonula occludens-1-associated nucleic acid-binding protein at neuronal gap junctions in rodent retina. Neuroscience. 2006;140:433–451. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laing JG, Koval M, Steinberg TH. Association with ZO-1 correlates with plasma membrane partitioning in truncated connexin45 mutants. J Membr Biol. 2005;207:45–53. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0803-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meyer RA, Laird DW, Revel JP, Johnson RG. Inhibition of gap junction and adherens junction assembly by connexin and A-CAM antibodies. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:179–189. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tamkun MM, O’Connell KM, Rolig AS. A cytoskeletal-based perimeter fence selectively corrals a sub-population of cell surface Kv2.1 channels. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2413–2423. doi: 10.1242/jcs.007351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu C, Barker RJ, Hunter AW, Zhang Y, Jourdan J, Gourdie RG. Quantitative analysis of ZO-1 colocalization with Cx43 gap junction plaques in cultures of rat neonatal cardiomyocytes. Microsc Microanal. 2005;11:244–248. doi: 10.1017/S143192760505049X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hunter AW, Barker RJ, Zhu C, Gourdie RG. Zonula occludens-1 alters connexin43 gap junction size and organization by influencing channel accretion. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:5686–5698. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Derangeon M, Bourmeyster N, Plaisance I, Pinet-Charvet C, Chen Q, Duthe F, Popoff MR, Sarrouilhe D, Hervé JC. RhoA GTPase and F-actin dynamically regulate the permeability of Cx43-made channels in rat cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30754–30765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801556200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mitic LL, Schneeberger EE, Fanning AS, Anderson JM. Connexin–occludin chimeras containing the ZO-binding domain of occludin localize at MDCK tight junctions and NRK cell contacts. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:683–693. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.3.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Toyofuku T, Yabuki M, Otsu K, Kuzuya T, Hori M, Tada M. Direct association of the gap junction protein connexin-43 with ZO-1 in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12725–12731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Giepmans BN, Moolenaar WH. The gap junction protein connexin43 interacts with the second PDZ domain of the zona occludens-1 protein. Curr Biol. 1998;8:931–934. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laing JG, Manley-Markowski RN, Koval M, Civitelli R, Steinberg TH. Connexin45 interacts with zonula occludens-1 and connexin43 in osteoblastic cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23051–23055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100303200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.TenBroek EM, Lampe PD, Solan JL, Reynhout JK, Johnson RG. Ser364 of connexin43 and the upregulation of gap junction assembly by cAMP. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:1307–1318. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200102017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maass K, Shibayama J, Chase SE, Willecke K, Delmar M. C-terminal truncation of connexin43 changes number, size, and localization of cardiac gap junction plaques. Circ Res. 2007;101:1283–1291. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.162818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hertig CM, Eppenberger-Eberhardt M, Koch S, Eppenberger HM. N-cadherin in adult rat cardiomyocytes in culture. I. Functional role of N-cadherin and impairment of cell–cell contact by a truncated N-cadherin mutant. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1–10. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kostin S, Hein S, Bauer EP, Schaper J. Spatiotemporal development and distribution of intercellular junctions in adult rat cardiomyocytes in culture. Circ Res. 1999;85:154–167. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Y, Rose B. An inhibition of gap-junctional communication by cadherins. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:301–309. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li J, Patel VV, Radice GL. Dysregulation of cell adhesion proteins and cardiac arrhythmogenesis. Clin Med Res. 2006;4:42–52. doi: 10.3121/cmr.4.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Govindarajan R, Zhao S, Song XH, Guo RJ, Wheelock M, Johnson KR, Mehta PP. Impaired trafficking of connexins in androgen-independent human prostate cancer cell lines and its mitigation by alpha-catenin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50087–50097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Keane RW, Mehta PP, Rose B, Honig LS, Loewenstein WR, Rutishauser U. Neural differentiation, NCAM-mediated adhesion, and gap junctional communication in neuroectoderm. A study in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:1307–1319. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.4.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frenzel EM, Johnson RG. Gap junction formation between cultured embryonic lens cells is inhibited by antibody to N-cadherin. Dev Biol. 1996;179:1–16. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kanno Y, Sasaki Y, Shiba Y, Yoshida-Noro C, Takeichi M. Monoclonal antibody ECCD-1 inhibits intercellular communication in teratocarcinoma PCC3 cells. Exp Cell Res. 1984;152:270–274. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(84)90253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Luo Y, Radice GL. Cadherin-mediated adhesion is essential for myofibril continuity across the plasma membrane but not for assembly of the contractile apparatus. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1471–1479. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wahl JK, III, Kim YJ, Cullen JM, Johnson KR, Wheelock MJ. N-cadherin–catenin complexes form prior to cleavage of the proregion and transport to the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17269–17276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211452200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Anderson SC, Stone C, Tkach L, SundarRaj N. Rho and Rho-kinase (ROCK) signaling in adherens and gap junction assembly in corneal epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:978–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jongen WM, Fitzgerald DJ, Asamoto M, Piccoli C, Slaga TJ, Gros D, Takeichi M, Yamasaki H. Regulation of connexin 43-mediated gap junctional intercellular communication by Ca2+in mouse epidermal cells is controlled by E-cadherin. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:545–555. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.3.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hernandez-Blazquez FJ, Joazeiro PP, Omori Y, Yamasaki H. Control of intracellular movement of connexins by E-cadherin in murine skin papilloma cells. Exp Cell Res. 2001;270:235–247. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eckert JJ, McCallum A, Mears A, Rumsby MG, Cameron IT, Fleming TP. Relative contribution of cell contact pattern, specific PKC isoforms and gap junctional communication in tight junction assembly in the mouse early embryo. Dev Biol. 2005;288:234–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Noren NK, Niessen CM, Gumbiner BM, Burridge K. Cadherin engagement regulates Rho family GTPases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33305–33308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Matsuda T, Fujio Y, Nariai T, Ito T, Yamane M, Takatani T, Takahashi K, Azuma J. N-cadherin signals through Rac1 determine the localization of connexin 43 in cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wheelock MJ, Johnson KR. Cadherin-mediated cellular signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:509– 514. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chung SS, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Study on the formation of specialized inter-Sertoli cell junctions in vitro. J Cell Physiol. 1999;181:258–272. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199911)181:2<258::AID-JCP8>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee NP, Leung KW, Wo JY, Tam PC, Yeung WS, Luk JM. Blockage of testicular connexins induced apoptosis in rat seminiferous epithelium. Apoptosis. 2006;11:1215–1229. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-6981-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kojima T, Spray DC, Kokai Y, Chiba H, Mochizuki Y, Sawada N. Cx32 formation and/or Cx32-mediated intercellular communication induces expression and function of tight junctions in hepatocytic cell line. Exp Cell Res. 2002;276:40–51. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Murata M, Kojima T, Yamamoto T, Go M, Takano K, Chiba H, Tokino T, Sawada N. Tight junction protein MAGI-1 is up-regulated by transfection with connexin 32 in an immortalized mouse hepatic cell line: cDNA microarray analysis. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;319:341–347. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-1017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Eckert JJ, Fleming TP. Tight junction biogenesis during early development. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:717–728. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Morita H, Katsuno T, Hoshimoto A, Hirano N, Saito Y, Suzuki Y. Connexin 26-mediated gap junctional intercellular communication suppresses paracellular permeability of human intestinal epithelial cell monolayers. Exp Cell Res. 2004;298:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Go M, Kojima T, Takano K, Murata M, Koizumi J, Kurose M, Kamekura R, Osanai M, Chiba H, Spray DC, Himi T, Sawada N. Connexin 26 expression prevents down-regulation of barrier and fence functions of tight junctions by Na+/K+-ATPase inhibitor ouabain in human airway epithelial cell line Calu-3. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:3847–3856. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kojima T, Murata M, Go M, Spray DC, Sawada N. Connexins induce and maintain tight junctions in epithelial cells. J Membr Biol. 2007;217:13–19. doi: 10.1007/s00232-007-9021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee NP, Yeung WS, Luk JM. Junction interaction in the seminiferous epithelium: regulatory roles of connexin-based gap junction. Front Biosci. 2007;12:1552–1562. doi: 10.2741/2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Defamie N, Mograbi B, Roger C, Cronier L, Malassine A, Brucker-Davis F, Fenichel P, Segretain D, Pointis G. Disruption of gap junctional intercellular communication by lindane is associated with aberrant localization of connexin43 and zonula occludens-1 in 42GPA9 Sertoli cells. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1537–1542. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.9.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Duffy HS, John GR, Lee SC, Brosnan CF, Spray DC. Reciprocal regulation of the junctional proteins claudin-1 and connexin43 by interleukin-1beta in primary human fetal astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1–6. RC114. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-j0004.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Koizumi JI, Kojima T, Kamekura R, Kurose M, Harimaya A, Murata M, Osanai M, Chiba H, Himi T, Sawada N. Changes of gap and tight junctions during differentiation of human nasal epithelial cells using primary human nasal epithelial cells and primary human nasal fibroblast cells in a noncontact coculture system. J Membr Biol. 2007;218:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00232-007-9029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Simon AM, McWhorter AR. Vascular abnormalities in mice lacking the endothelial gap junction proteins connexin37 and connexin40. Dev Biol. 2002;251:206–220. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Garrido-Urbani S, Bradfield PF, Lee BP, Imhof BA. Vascular and epithelial junctions: a barrier for leucocyte migration. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36:203–211. doi: 10.1042/BST0360203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Véliz LP, González FG, Duling BR, Sáez JC, Boric MP. Functional role of gap junctions in cytokine-induced leukocyte adhesion to endothelium in vivo. Am J Physiol. 2008;295:H1056–H1066. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00266.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pollmann MA, Shao Q, Laird DW, Sandig M. Connexin 43 mediated gap junctional communication enhances breast tumor cell diapedesis in culture. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R522–R534. doi: 10.1186/bcr1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Talhouk RS, Mroue R, Mokalled M, Abi-Mosleh L, Nehme R, Ismail A, Khalil A, Zaatari M, El-Sabban ME. Heterocellular interaction enhances recruitment of alpha and beta-catenins and ZO-2 into functional gap-junction complexes and induces gap junction-dependant differentiation of mammary epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:3275–3291. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Matter K, Balda MS. Signalling to and from tight junctions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:225–236. doi: 10.1038/nrm1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Penes MC, Li X, Nagy JI. Expression of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) and the transcription factor ZO-1-associated nucleic acid-binding protein (ZONAB)-MsY3 in glial cells and colocalization at oligodendrocyte and astrocyte gap junctions in mouse brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:404–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ooshio T, Fujita N, Yamada A, Sato T, Kitagawa Y, Okamoto R, Nakata S, Miki A, Irie K, Takai Y. Cooperative roles of Par-3 and afadin in the formation of adherens and tight junctions. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2352–2365. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mege RM, Matsuzaki F, Gallin WJ, Goldberg JI, Cunningham BA, Edelman GM. Construction of epithelioid sheets by transfection of mouse sarcoma cells with cDNAs for chicken cell adhesion molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:7274–7278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.19.7274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Girao H, Pereira P. The proteasome regulates the interaction between Cx43 and ZO-1. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:719–728. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]