Abstract

This study examined the development of aggressive and oppositional behavior among alcoholic and nonalcoholic families using latent growth modeling. The sample consisted of 226 families assessed at 18, 24, 36, and 48 months of child age. Results indicated that children in families with nonalcoholic parents had the lowest levels of aggressive behavior at all time points compared to children with one or more alcoholic parents. Children in families with two alcoholic parents did not exhibit normative decreases in aggressive behavior from 3 to 4 years of age compared to nonalcoholic families. However, this association was no longer significant once a cumulative family risk score was added to the model. Children in families with high cumulative risk scores, reflective of high parental depression, antisocial behavior, negative affect during play, difficult child temperament, marital conflict, fathers’ education, and hours spent in child care, had higher levels of aggression at 18 months than children in low risk families. These associations were moderated by child gender. Boys had higher levels of aggressive behavior at all ages than girls, regardless of group status. Cumulative risk was predictive of higher levels of initial aggressive behavior in both girls and boys. However, boys with two alcoholic parents had significantly less of a decline in aggression from 36 to 48 months compared to boys in the nonalcoholic group.

Keywords: children of alcoholics, aggression, child behavior, child development

Years of research have shown that having an alcoholic parent places children at risk for a multitude of behavioral and socioemotional problems (Carbonneau et al., 1998; Clark et al., 1997; Johnson, Leonard, & Jacob, 1989; Leonard et al., 2000, Puttler, Zucker, Fitzgerald, & Bingham, 1998). The threat to boys is particularly strong, as sons of alcoholic parents have markedly greater chances of developing conduct disorder, engaging in delinquency, and abusing substances (Loukas, Zucker, Fitzgerald, & Krull, 2003; Tarter, Kirisci, & Clark, 1997; Carbonneau et al., 1998; Zucker, Fitzgerald, & Moses, 1995). One of the strongest markers for later maladaptation is early externalizing problems (White, Moffitt, Earls, Robing, & Silva, 1990). The association between externalizing behavior and later alcohol abuse is in fact so strong that Wong, Zucker, Puttler, and Fitzgerald (1999) used it as a proxy indicator of alcohol use in a sample of 6 to 8 year old children too young to yet engage in substance use because it “captures the antisocial deviancy construct that has been so strongly and consistently linked to adolescent alcohol use, as well as adult alcoholic outcomes” (p. 729). The present study will examine the development of aggression from the toddler to the preschool period in children of alcoholic parents. It is important to note that this study examines aggression as it is defined by Achenbach in his Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000). It includes physical aggression, as well as noncompliance and defiance, all of which have been linked to later conduct disorders.

Tremblay (2000), in a review of a century’s work on the study of aggression, observed that physical aggression begins as soon as children possess the motor abilities to lash out. The period of the “terrible twos” is also a time of defiance and oppositional behavior. As toddlers develop increasing self-control and verbal skills, physical aggression and oppositional behavior tend to decrease (Campbell, 1995; Loukas et al., 2003). Accordingly, a normative trajectory has been identified wherein aggression and oppositional behavior increases until children are 2–3 years of age and then declines (Campbell, 1995; Cummings, Iannotti, & Zahn-Waxler, 1989; Nagin & Tremblay, 1999; Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby, & Nagin, 2003; Spieker, Larson, Lewis, Keller, & Gilchrist, 1999; Tremblay et al., 1996). However, there is a small group of children who are persistently aggressive or defiant and are at a particularly high risk of developing later psychopathology (Campbell, 1995; Moffitt, Caspi, Dickson, Silva, & Stanton, 1996; Nagin & Tremblay, 1999). Further highlighting the critical nature of the early years, several longitudinal studies have found that there is no evidence for the onset of physical aggression after 6 years of age (for a review see Broidy et al., 2003). Thus, early identification of aggressive and oppositional behavior, particularly in children of alcoholic parents, is an important area of study for descriptive purposes and to guide prevention efforts. The association between alcohol and problem behaviors may have its roots in early self-regulation difficulties. Around 2 years of age toddlers begin to develop inhibitory control abilities that are reflective of their temperaments and parental socialization (Emde, Biringen, Clyman, & Oppenheim, 1991; Kopp, 1982; Rothbart, 1989). It has been hypothesized that children of alcoholic parents are at greater risk for temperamental difficulties (Tarter, 1988) manifested as negative affect (Eisenberg et al., 1993, 2003; Kochanska, Tjebkes, & Forman, 1998; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001), high activity level, and attention problems (Barkley, 1997; Rothbart et al., 2001) which can adversely affect the development of such self-regulatory capabilities. As such, the capacity for internalization of rules and behavioral control in these children may be impaired leading to later conduct problems. Indeed, high activity level and negative affect have been associated with the development of problem behaviors among children of alcoholic parents (Wong et al., 1999) and with later substance use (Dawes, Tarter, & Kirisci, 1997; Tarter et al., 1999; Wills, DuHamel, & Vaccaro, 1995). Illustrating this trajectory, 3 to 5-year-old children with emotional and attentional control difficulties were shown to be at greater risk of externalizing behavior problems in later childhood and early adolescence, aggression at age 18, and alcohol dependence at age 21 (Caspi, Moffit, Newman, & Silva, 1996; Caspi & Silva, 1995). In our own studies we have noted the association between child characteristics, such as negative affect and activity level at 2 years and effortful control at 2 and 3 years of age for boys (Eiden, Edwards, & Leonard, 2004). Thus, children of alcoholic parents are at increased risk of behavioral regulation difficulties that may prevent the expected normative decline in aggressive behavior.

However, it is important to note that such individual risk factors are nested within a high-risk environment (Loukas et al., 2003; Zucker, Wong, Puttler, & Fitzgerald, 2002) and there is considerable heterogeneity in terms of child outcome. Zucker (1991) highlights the necessity of examining familial, psychological, and biological factors to produce a complete picture of the transactional influences on risk and resiliency in the development of alcoholism. The utility of such cumulative risk effects have been confirmed in numerous studies (Eiden, Edwards, & Leonard, 2002; Loukas, Fitzgerald, Zucker, & von Eye, 2001; Wong et al., 1999). In the current study, there are a number of variables that may influence the development of aggression, both in isolation and in interaction with one another. In addition to having an increased risk of child regulatory difficulties, alcoholic families have been characterized as being high in parental depression, antisocial behavior, and marital conflict, all of which have been shown to have direct and indirect effects (via parenting) on the development of child externalizing behaviors (Edwards, Leonard, & Eiden, 2001; Eiden, Chavez, & Leonard, 1999; Eiden et al., 2002; Loukas et al., 2003; Puttler et al., 1998). Parent–child interactions in these families are often marked by heightened parental negative affect (Eiden et al., 1999; Eiden, Leonard, Hoyle, & Chavez, 2004), a dimension of parenting that has been consistently associated with the development of externalizing behavior problems (Conger et al., 2002; Kim & Brody, 2003). In summary, all of these risk factors are not only associated with each other and with alcohol problems, but are also likely to have significant effects on developmental trajectories of children’s aggressive behavior.

There is a large literature linking risk factors associated with alcoholism with the development of children’s behavior problems. For instance, Jacob and Johnson (2001) reported significant effects of parents’ depression on both parent–child interaction patterns as well as higher rates of child behavior problems. Further, mothers of children referred for clinical levels of externalizing problems have been found to have higher levels of maternal depression (Richman, 1979; Griest, Forehand, Wessl, & McMahon, 1980), and maternal depression has been associated with higher levels of behavior problems among boys in nonclinic samples (Gross, Conrad, Fogg, Willis, & Garvey, 1995). In a study of the correlates of parents’ depression, Lyons-Ruth and colleagues noted that depressed mothers and fathers are more likely to be frustrated, aggravated, and use negative discipline (Lyons-Ruth, Wolfe, Lyubchik, & Steingard, 2002), parenting behaviors that have significant implications for the development of behavior problems.

The few studies of antisocial fathers have noted the importance of fathers’ antisocial behavior in predicting children’s conduct problems, especially if these antisocial fathers reside in the home (e.g., Jaffee, Moffit, Caspi, & Taylor, 2003; Puttler et al., 1998) found that children of antisocial alcoholics had significantly more behavior problems than children of both nonantisocial alcoholics and controls, suggesting that parental antisociality exacerbates children’s risk of maladaptive behavioral outcomes. Similarly, antisocial parents have also been found to expose their children to more aggressive and conflictual marital interactions (Patterson & Capaldi, 1991). Such marital conflict has in turn been associated with the development of disruptive behavior problems (Loukas et al., 2003). Although there is some debate over the role of alcohol in causing marital aggression, the literature linking alcoholism to marital aggression clearly demonstrates that alcoholism is associated with increased interparental conflict and violence (Leonard & Quigley, 1999; Murphy & O’Farrell, 1996; Quigley & Leonard, 2000). Further, marital conflict has been found to have independent associations with maladjustment in young children, even after accounting for parenting (Buehler & Gerard, 2002; Frosch & Mangelsdorf, 2001). The data regarding the association between parental conflict or aggression and child behavior problems suggest that families with high levels of conflict have children with higher rates of behavior problems (O’Brien & Bahadur, 1998; O’Keefe, 1994).

While research on children of alcoholic parents has generally focused on early school age and adolescent children, infants and toddlers of alcoholic parents have also been shown to experience more negative parenting (Eiden et al., 1999, 2002). Moreover, several studies have noted the strong and consistent association between harsh or negative parenting and the development of behavior problems. For instance, parents’ negative affect dimensions such as anger, hostility, and harsh discipline have all been associated consistently with higher levels of externalizing behavior problems such as conduct disorder (e.g., Belsky, Woodworth, & Crnic, 1996; Campbell, Pierce, Moore, Marakovitz, & Newby, 1996; Kochanska, 1997). In a seminal paper, Patterson (1982) noted that a spiraling chain of exchanges between parent and child with increasing levels of negative affect leads to a coercive cycle that promotes the development of children’s aggressive behavior.

Gender differences in the development of aggression are widely accepted. Although no consistent differences have been found in the toddler period (Keenan & Shaw, 1997), boys become increasingly physically aggressive in comparison to girls in the preschool period (Achenbach, Edelbrock, & Howell, 1987; Campbell, 1995; Zahn-Waxler, Iannotti, Cummings, & Denham, 1990). Additional studies have demonstrated gender differences in the type of aggression displayed by children in middle childhood, with boys engaging in confrontational, physical forms of aggression and girls engaging in relational or indirect aggression (see Crick & Zahn-Waxler, 2003; Lagerspetz, Björkqvist, & Peltonen, 1988). Few studies have examined gender differences in earlier developmental trajectories (see Côté, Tremblay, Zoccolillo, & Vitaro, 2002 for an exception) and chronic aggression is difficult to study in girls, as its prevalence is so low in comparison to boys (see Broidy et al., 2003 for a review). Particularly little is known about trajectories of aggression among daughters of alcoholic parents, although sons of alcoholic parents have been found in previous studies to display a higher level of aggressive behavior from 3 to 12 years of age compared to sons of nonalcoholics (e.g., Loukas et al., 2001, 2003). Our sample is unique in that it allows us to examine trajectories of aggression in very young children of both genders in normative, father alcoholic, and two parent alcoholic families, areas previously unexamined in the literature among such a cohort.

The current study examined the role of gender in predicting trajectories of aggressive behavior and the impact of parental alcoholism and other risk factors on aggression trajectories for boys and girls. Several hypotheses were explored in the present study. First, we examined if there are individual differences in the developmental trajectory of aggressive behavior from 18 to 48 months. Second, we expected that the overall developmental trajectory from 18 to 48 months would be nonlinear, peaking at 3 years of age and then declining thereafter. Third, we hypothesized that children from families with at least one alcoholic parent would have higher levels of aggressive behavior at 18 months (time 1), would display an increasing rate of change in aggressive behavior from 18 to 36 months, and would not evidence the same level of decline from 36 to 48 months of age relative to children without an alcoholic parent. Children with two alcoholic parents were expected to have a higher rate of increase in aggressive behavior and a lower decline. We further hypothesized that cumulative family risk would also be associated with higher initial levels of aggressive behavior and failure to evidence normative declines from three to 4 years of age. Finally, we hypothesized that the impact of parental alcoholism and cumulative risk on the developmental trajectory of aggressive behavior would vary by child gender. We expected that parental alcoholism and family risk would be associated with a higher rate of increase in aggressive behavior and less of a normative decline for boys. Given the paucity of research on girls of alcoholic parents, we did not have any specific hypothesis about the role of parental alcoholism on aggression among girls, but explored the association between alcoholism, associated cumulative risk, and the developmental trajectory of aggressive behavior among girls.

METHOD

Participants

The participants were 226 families with 12 month old infants (110 girls and 116 boys) who volunteered for an ongoing longitudinal study of parenting and infant development. Families were classified as being in one of two major groups: the nonalcoholic group consisting of parents with no or few current alcohol problems (n = 102), and the father alcoholic group (n = 124). Within the father alcoholic group, 92 mothers were light drinking or abstaining and 32 mothers were heavy drinking or had current alcohol problems. As would be expected of longitudinal studies involving multiple family members, there were incomplete data for some participants at one or more of the four assessments. All of the 226 families provided complete data at the 12 and 18 month visits; 222 families provided data at the 24 month visit; 205 families provided data at the 36 month visit; and 182 families provided data at the 48 month visit.

Ninety-four percent of the mothers in the study were Caucasian, about 4% were African-American, and 2% were Hispanic or Native-American. Similarly, 90% of fathers were Caucasian, 7% were African-American, and 3% were Hispanic or Native-American. The majority of the mothers had a posthigh school education such as an associate or vocational degree (31%) or were college graduates (27%). Very few were not high school graduates (2%). The educational level of the fathers was similar, with 33% receiving a college degree and 18% receiving some posthigh school education. Only 5% had not graduated from high school. All of the mothers were residing with the father of the infant in the study. Most of the parents were married to each other (88%), about 11% had never been married, and 1% had previously been married. Mothers’ ages ranged from 19 to 41 (M = 30.7, SD = 4.46) and fathers’ ages ranged from 21 to 58 (M = 32.95, SD = 5.94). About 62% of the mothers and 92% of the fathers were working outside the home at the time of the 12 month assessment, with very similar percentages working at the 18 month assessment (66% of mothers and 92% of fathers).

Procedures

The names and addresses of these families were obtained from New York State birth records for Erie County. These birth records were preselected to exclude families with premature (gestational age of 35 weeks or lower), or low birth weight infants (birth weight of less than 2,500 grams), maternal age of less than 19 or greater than 40 at the time of the infant’s birth, plural births (e.g., twins), and infants with congenital anomalies, palsies, or drug withdrawal symptoms. Introductory letters were sent to a large number of families (n = 9,457) who met these basic eligibility criteria. Each letter included a form that all families were asked to complete and return. Approximately 25% of these families completed the form and, of these, 2,285 replies (96%) indicated an interest in the study. Respondents were compared to the overall population with respect to information collected on the birth records. These analyses indicated a slight tendency for infants of responders to have higher Apgar scores (M = 8.97 vs. 8.94 on a scale ranging from 1 to 10), higher birth weight (M = 3,516 vs. 3,460 grams), and a higher number of prenatal visits (M = 10.50 vs. 10.31). Responders were also more likely to be Caucasian (88% of total births vs. 91% of responders), have higher educational levels, and have a female infant. These differences were significant given the very large sample size, even though the size of the differences was generally small (Cohen’s d < .22 in all analyses).

Parents who indicated an interest in the study were screened by telephone with regard to sociodemographics and further eligibility criteria. Initial inclusion criteria required that both parents were cohabiting since the infant’s birth, the target infant was the youngest child in the family and did not have any major medical problems, the mother was not pregnant at the time of recruitment, there were no mother–infant separations of over a week’s time, and the biological parents were the primary caregivers. These criteria were important to control because each of these has the potential to markedly alter parent–infant interactions. Additional inclusion criteria were utilized to minimize the possibility that any observed infant behaviors could be the result of prenatal exposure to drugs or heavy alcohol use. These additional criteria were that there could be no maternal drug use during pregnancy or the past year except for mild marijuana use (no more than twice during pregnancy), the mother’s average daily ethanol consumption was .50 ounces or less and she did not engage in binge drinking (5 or more drinks per occasion) during pregnancy. During the phone screen, mothers were administered the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria for alcoholism with regard to their partners’ drinking (RDC; Andreason, Rice, Endicott, Reich, & Coryell, 1986) and fathers and mothers were screened with regard to their alcohol use, problems, and treatment.

Families meeting the basic inclusion criteria were provisionally assigned to one of three groups (nonalcoholic, father alcoholic, both alcoholic) on the basis of parental phone screens, with final group status assigned on the basis of both the phone screen and questionnaires administered after the family began the study. Mothers in the nonalcoholic group scored below 3 on an alcohol screening measure (TWEAK; Chan, Welte, & Russell, 1993), were not heavy drinking (average daily ethanol consumption <1.00 ounces), did not acknowledge binge drinking, and did not meet DSM-IV criteria for abuse or dependence. Fathers in the nonalcoholic group did not meet RDC criteria for alcoholism according to maternal report, did not acknowledge having a problem with alcohol, had never been in treatment, and had alcohol related problems (e.g., work, family, legal) in fewer than two areas in the past year and three areas in their lifetime (according to responses on a screening interview based on the University of Michigan Composite Diagnostic Index, UM-CIDI; Anthony, Warner, & Kessler, 1994). A family could be classified in the father alcoholic group if the mothers met nonalcoholic status and the father met any one of the following three criteria: (1) the father met RDC criteria for alcoholism according to maternal report; (2) he acknowledged having a problem with alcohol or having been in treatment for alcoholism, was currently drinking, and had at least one alcohol-related problem in the past year; or (3) he indicated having alcohol-related problems in three or more areas in the past year or met DSM-IV criteria for abuse or dependence in the past year. A family was assigned to the both alcoholic group if the father met the above alcoholism criteria and the mother acknowledged alcohol-related problems (TWEAK score of three or higher or met DSM-IV diagnosis for abuse or dependence) or was heavy drinking (average daily ethanol consumption of 1.00 ounces or higher, and/or binge drinking more than two times a month). All of the women in this group met DSM-IV criteria for abuse or dependence.

It should be noted that women who reported drinking moderate to heavy amounts of alcohol during pregnancy (see criteria above) were excluded from the study in order to control for potential fetal alcohol effects. Because we had a large pool of families potentially eligible for the nonalcoholic group, nonalcoholic families were matched to alcoholic families with respect to race/ethnicity, maternal education, child gender, parity, and marital status.

To date, families were assessed at six different ages (12, 18, 24, 36, and 48 months and upon entry into kindergarten). At each age, parents were sent a packet of questionnaires, one for each parent. Both parents were asked to complete the questionnaires independently and return them in sealed envelopes. This paper focuses on the 18, 24, 36, and 48 month questionnaire assessments (data collection was not yet complete for the kindergarten assessments).

Measures

Parental Alcohol Group Status

Although parental alcohol abuse and dependence problems were partially assessed from the screening interview, self-report versions with more detailed questions were used to enhance the alcohol data and check for consistent reporting. The UM-CIDI interview (Anthony et al., 1994; Kessler et al., 1994) was used to assess alcohol abuse and dependence. Several questions were reworded to inquire as to “how many times” a problem had been experienced, as opposed to whether it happened “very often.” DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence diagnoses for current alcohol problems (in the past year) were used to assign final diagnostic group status. For abuse criteria, recurrent alcohol problems were described as those occurring at least 3–5 times in the past year or 1–2 times in three or more problem areas. As described above, families were placed in one of three groups on the basis of phone screen and questionnaire data: (1) the nonalcoholic group; (2) the father alcoholic group; and (3) the both parents alcoholic group.

Infant Temperament

Mother and father reports of infant temperament were obtained with the Infant Characteristics Questionnaire (ICQ; Bates, Freeland, & Lounsbury, 1979). The ICQ is a widely used parent report measure, which requires the parents to rate a number of their children’s behaviors on a seven-point scale ranging from never to always. The scale yields four factors: Fussy-Difficult, Unadaptable, Dull, and Unpredictable (Bates et al., 1979) as well as a total score. The total score was used for the purposes of these analyses. The scale has high internal consistency and strong test–retest reliability (Bates et al., 1979). Internal consistency in the present study was .87 for mothers and .85 for fathers.

Parents’ Depression

Parents’ depression was assessed with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Inventory (CESD; Radloff, 1977), a scale designed to measure depressive symptoms in community populations. The CESD is a widely used, self-report, four-point Likert type measure. Parents were asked to report how often they experienced 20 depressive symptoms (e.g., poor appetite, feeling sad, inability to concentrate) during the past week with responses including rarely or none, some or a little of the time (1–2 days), occasionally or a moderate amount of time (3–4 days), or most or all of the time (5–7 days). The scale has high internal consistency (Radloff, 1977), and strong test–retest reliability (Boyd, Weissman, Thompson, & Myers, 1982; Ensel, 1982). Internal consistency in the present study was .89 for mothers and .85 for fathers.

Antisocial Behavior

A modified version of the Antisocial Behavior Checklist (ASB; Zucker & Noll, 1980) was used in this study. Because of concerns about causing family conflict as a result of parents reading each others responses, items related to sexual antisociality and those with low population base rates (Zucker, 1995, personal communication) were dropped. This resulted in a 28-item measure of both lifetime and current antisocial behavior. Parents were asked to rate their frequency of participation in a variety of aggressive and antisocial activities along a four-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (often). The measure has been found to discriminate among groups with major histories of antisocial behavior (e.g., prison inmates, individuals with minor offenses in district court, and university students, Zucker & Noll, 1980), and between alcoholic and nonalcoholic adult males (Fitzgerald, Jones, Maguin, Zucker, & Noll, 1991). Parents’ scores on this measure were also associated with maternal reports of child behavior problems among preschool children of alcoholic parents (Jansen, Fitzgerald, Ham, & Zucker, 1995). The original measure has adequate test–retest reliability (.91 over 4 weeks) and internal consistency (coefficient alpha = .93). The internal consistency of the 28-item measure in the current sample was quite high for both parents (alpha = .90 for fathers and .80 for mothers).

Family Conflict

Mother and father reports of physical aggression were obtained from a modified version of the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus, 1979). The items focusing on moderate (e.g., push, grab, or shove) to severe (e.g., hit with a fist) physical aggression, but not the very severe items (e.g., burnt or scalded, use of weapons) were used in this study. Parents were asked to report on the frequency of their own and their partner’s aggression toward each other on a seven-item scale. Internal consistency on this scale was .87 for mothers and .88 for fathers in the current sample.

Parent–Infant Interactions

Mothers and fathers were asked to interact with their children as they normally would at home for 10 min in a room filled with toys at 18 months of child age. The free-play interactions were followed by 8 min of structured play. During structured play, parents were given four sets of problem-solving tasks. They were asked to help their infants complete these tasks one at a time and then move on to the next task. Mother–child and father–child interactions were conducted separately. These interactions were coded using a collection of global five-point rating scales developed by Clark, Musick, Scott, and Klehr (1980), with higher scores indicating more positive behavior. These items have been found to be applicable for children ranging in age from 2 months to 5 years (Clark et al., 1980; Clark, 1999). Two composite scales of maternal and paternal negative affect were derived from these items (see Eiden et al., 1999; Eiden, Leonard et al., 2004 for further details). These composite scales included items such as parents’ angry/hostile tone of voice, angry/hostile mood, and disapproval or criticism of the child. The internal consistency of this scale at 18 months was quite high (Cronbach’s alpha = .87 for mothers and .85 for fathers). Higher scores on parental negative affect scales indicated lower negative affect.

Two sets of coders rated the free-play interactions and structured play interactions. Coders who rated mother–child interactions did not rate the father–child interactions. All coders were trained on the Clark scales by the second author and were unaware of group membership and all other data. Interrater reliability was calculated for 17% of the sample (n = 38) and was high for all six subscales, ranging from Intraclass correlation coefficients of .81 to .92.

Cumulative Risk Score

In order to create a cumulative risk score and assign equal weight to each risk factor, composite scores were created for all the risk factors. These included fathers’ education, number of hours in child care per week, difficult infant temperament, fathers’ depression, mothers’ depression, fathers’ antisocial behavior, mothers’ antisocial behavior, fathers’ aggression toward mother, mothers’ aggression toward father, fathers’ negative affect during play, and mothers’ negative affect during play. All variables were measured at 18 months of child age. Similar to previous studies (Eiden et al., 2002; Sameroff, Seifer, Baldwin, & Baldwin, 1993), scores in the upper or lower quartile (depending upon the scale) were used as the cutoff for risk, with the exception of fathers’ education with clear criteria for risk (less than high school education—5% of the sample). Families reporting the use of more than 30 hours a week of child care were assigned to the risk category (28% of the sample). For infant temperament, scores above 113 for mothers (26% of the sample) and above 115 for fathers (28% of the sample) were assigned to the risk category. For fathers’ depression, total depression scale scores above 9 were assigned to the risk category (27% of the sample). For mothers’ depression, total depression scale scores above 10 were assigned to the risk category (27% of the sample). For fathers’ antisocial behavior, scores above 44 were assigned to the risk category (26% of the sample). For mothers’ antisocial behavior, scores above 39 were assigned to the risk category (25% of the sample). For parents’ aggression toward each other (composite score computed by taking the sum of moderate and severe aggression as reported by both parents), scores above 2 for mother to father aggression and scores above a 1 for father to mother aggression were assigned to the risk category (30% of the sample for fathers’ aggression and 27% of the sample for mothers’ aggression). For fathers’ negative affect during play, scores below 4.1 were assigned to the risk category (26% of the sample). For mothers’ negative affect during play, scores below 4.2 were assigned to the risk category (28% of the sample). The total risk score was computed by counting the total number of risk categories, with a possible range of scores between 0 and 12. The range of scores in this study was 1–12 (see Table I).

Table I.

Means and Standard Deviations of Child Aggression and Family Risk

| 18 month aggression | 24 month aggression | 36 month aggression | 48 month aggression | Family risk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonalcoholic | .45 (.26) | .52 (.22) | .54a (.24) | .40ab (.20) | 3.15ab (1.74) |

| Father alcoholic | .52 (.26) | .56 (.27) | .60 (.29) | .59a (.24) | 4.39a (2.04) |

| Both alcoholic | .50 (.26) | .57 (.31) | .64a (.35) | .63b (.25) | 4.94b (2.53) |

Note. Means with different superscripts were significantly different (p < .05).

Child Aggression

Parent reports of child aggression at 18, 24, 36, and 48 months were assessed using the Aggression subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1992; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000). The CBCL is a widely used measure of children’s behavioral/emotional problems with well-established psychometric properties. It consists of items rated on a three-point response scale ranging from 0 “not true” to 2 “very true,” with some open-ended items designed to elicit detailed information about a particular problem behavior. Higher scores indicate more toddler behavior problems. There are two versions of the CBCL, one for children ages 18 months to 3 years, and the other for children 4–18 years of age. Both versions contain items that measure externalizing and internalizing behaviors, but the content of some items vary in order to capture age related changes in the expression of these behavior. The aggression subscale contains items relating to physical aggression, noncompliance, and oppositional behavior. For the purpose of this study, a mean aggression score was calculated at each age for both mothers and fathers. A composite rating of child aggression was then created by calculating the mean of mothers’ and fathers’ item scores (0–2) at each age. The association of mothers’ and fathers’ scores ranged from .34 to .42 (see Table I).

Missing Data

As would be expected of longitudinal studies involving multiple family members, there were incomplete data for some participants at one or more of the four assessment points included in this study. Of the families missing at 24 months, 50% were in the nonalcoholic group, 25% were in the father alcoholic group, and 25% were in the both alcoholic group. Of those missing at 36 months, 29% were in the nonalcoholic group, 38% were in the father alcoholic group, and 33% were in the both alcoholic group. Of those missing at 48 months, 43% were in the nonalcoholic group, 34% were in the father alcoholic group, and 23% were in the both alcoholic group. Although families with missing data at 36 and 48 months were more likely to be in the alcoholic groups, there were no differences between families with missing data and those with complete data on cumulative family risk or on the outcome variables (aggression). There were also no differences on the continuous measures of alcohol problems or alcohol use.

Although it is clear that the data were not missing completely at random (MCAR) at 36 and 48 months because a higher proportion of alcoholic families had missing data at these time points, we assumed that data were missing at random (MAR). Little and Rubin (1989) defined data as MAR when cases with incomplete data differed from cases with complete data, but the pattern of missingness could be predicted from other variables in the data base. They specifically cited longitudinal data where the potential cause for missingness (e.g., low self-esteem in a study about self-esteem) has been measured at earlier time points as meeting criteria for MAR. Discussions of missing data have also noted that the assumption for MAR can never be definitively assessed. However, given that no differences were found between alcoholic and nonalcoholic families on child aggression, the assumption of MAR seemed tenable for these data. In order to take advantage of all data provided by all participants, we used full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to estimate parameters in our models (Arbuckle, 1996). This missing data approach includes all cases in the analysis, even those with missing data. When data are missing at random, FIML produces good estimates of population parameters. Even if the data are not missing at random, FIML is thought to produce more accurate estimates of population parameters than if listwise deletion was used.

RESULTS

Prior to growth modeling analyses, the associations of demographic predictors with aggression were examined. Pearson correlations were computed between the number of hours in spent in child care, parental education, parental age, family income variables and children’s aggressive behavior score at each age. Only the number of hours in child care was significantly and positively associated with child aggression at 18 and 48 months of age (r = .14, .17, respectively). Next, we examined associations of these same variables with alcohol group status using ANOVA. Results indicated that there were significant group differences on the number of hours spent in child care and fathers’ education, (F(2, 226) = 3.40, p < .05; F(2, 226) = 4.31, p < .05, respectively). Families with two alcoholic parents had children that spent more time in child care than nonalcoholic families. Fathers in the alcohol groups tended to have lower levels of education than fathers in the nonalcoholic group. For these reasons, fathers’ education and the number of hours spent in child care were added to the cumulative risk score as described above.

Latent growth modeling was used to examine study hypotheses. Unlike other methods of examining change across time, latent growth models allow for examination of individual differences in developmental trajectories. As stated by Duncan, Duncan, Strycker, Li, and Alpert (1999), another critical attribute of the latent growth model is the ability to examine predictors of individual differences in order to understand which variables predict the rate of change (see also Curran & Bollen, 2001). Individual differences in change are expressed as variances of growth factors. When variances are estimated, these growth factors are commonly referred to as random effects. The means of the growth factors represent the average growth trajectory for the sample, and they are referred to as fixed effects. If the variances of the growth factors are 0, then this suggests that there are no significant individual differences in growth. A strength of LGCs is that they produce model fit indices, which provide information for evaluating how well the specified form of the growth trajectory fits the data. Good fitting models are thought to have a Comparative Fit Index (CFI) greater than .95, and a Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) less than .06 (Hu & Bentler, 1995). All analyses were conducted using M-Plus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2001).

The first goal was to replicate the developmental trajectory for aggressive behavior reported in previous studies, with a nonlinear growth curve. To this end, we initially estimated an unconditional latent growth model for child aggressive behavior. Latent growth curves are defined by latent intercept and slope factors. In our models, the intercept factor was parameterized such that it represented levels of aggression at age 18 months. The slope factor(s) represent(s) the effect of time and describe the shape of the growth curve. The unconditional growth model was estimated in a series of steps.

In the first model, we estimated the intercept only and this model fit the data poorly (see Table II). In the next, model a linear slope factor was added, which significantly improved the model fit based on the significant decrement in the model χ2; however, this model did not provide an adequate fit to the data. Accordingly, we added a quadratric slope factor, but this model produced negative variance estimates, suggesting that the model was poorly specified and may have included too many parameters. Therefore, we estimated two additional models. One model included a fixed linear slope (variance of the linear slope factor set to 0) and random quadratic slope (variance of the quadratic slope factor freely estimated) and the other included a random linear slope (variance of the linear slope factor freely estimated) and a fixed quadratic slope (variance of the quadratic slope factor set to 0). These models represent different ways of expressing individual differences in growth. The quadratic model with fixed linear slope provided the best fit to the data (see Table II), and this model was retained for subsequent analyses. There was significant variability in both the intercept (t = 8.91, p < .001) and quadratic (t = 3.34, p < .01) slope factors, suggesting individual variability in aggression at age 18 months and significant individual variability in the quadratic component of change. There was a significant negative association between the intercept and the quadratic slope factors (r = −.41), indicating that children with higher aggressive behavior at 18 months had a significantly lower decline in aggression from 36 to 48 months. Aggressive behavior increased from 18 to 36 months, peaked at 36 months, and declined from 36 to 48 months for the sample as a whole.

Table II.

Nested Models for Aggression Trajectory

| χ2 | df | p | CFI | RMSEA | χ2Δ | df Δ | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 91.56 | 3 | .00 | .79 | .36 | |||

| Model 2 | 85.68 | 2 | .00 | .80 | .43 | 5.88 | 1 | <.001 |

| Model 3 | 10.67 | 4 | .03 | .98 | .09 | 75.01 | 2 | <.001 |

| Model 4 | 5.21 | 4 | .27 | 1.0 | .04 | 80.47 | 2 | <.001 |

Note. Model 1: random intercept only; Model 2: random intercept and random linear slope; Model 3: linear model (fixed quadratic slope and random linear slope); Model 4: quadratic model (fixed linear slope and random quadratic slope). Change in Model 4 χ2 is relative to Model 2.

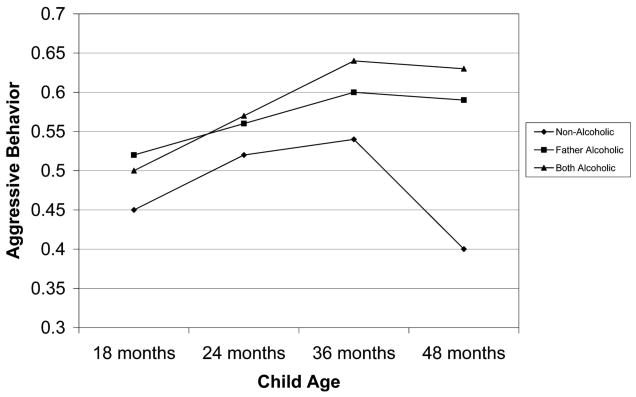

Next, we examined the effects of covariates. We hypothesized that children would vary in their growth trajectories as a function of their parents’ alcohol group status. In order to test this hypothesis, the intercept and quadratic growth factors were regressed on two dummy coded predictors: father alcoholic only (0 = nonalcoholic or both alcoholic, 1: father alcoholic only) and two alcoholic parents (0: nonalcoholic and father alcoholic only, 1: both alcoholic). This conditional growth model (quadratic model with a fixed linear slope) fit the data well (χ2 = 5.71, p = .46, CFI = 1.0, RMSEA = .00). The dummy coded variable of fathers’ alcohol group status was not significantly associated with the intercept or quadratic growth. However, the dummy coded variable of two alcoholic parents was negatively associated with the quadratic slope (β = −.45, t = −2.48, p < .05). Children with two alcoholic parents showed less decline in aggression from 36 to 48 months compared to the children in the nonalcoholic group (see Fig. 1). It is worth noting however, that children with nonalcoholic parents had the lowest levels of aggressive behavior at all time points.

Fig. 1.

Model implied growth trajectory for aggression.

The next step was to add the cumulative risk score to the model. We hypothesized that aggression growth trajectories would vary as a function of additional risk factors commonly nested within alcoholic families. In order to test this hypothesis, the intercept and quadratic growth factors were regressed on two dummy coded alcohol predictors, as well as a continuous measure of cumulative risk. This conditional growth model (quadratic model with a fixed linear slope) fit the data well (χ2 = 5.04, p = .66, CFI = 1.0, RMSEA = .00). The risk variable was significantly associated with the intercept (β = .53, t = −7.22, p < .001), but not with the quadratic growth (β = −.37, t = −1.64). However, the dummy coded alcohol variables were not associated with the intercept or quadratic slope. Children with higher levels of risk had significantly higher levels of aggressive behavior at 18 months compared with children in lower risk families.

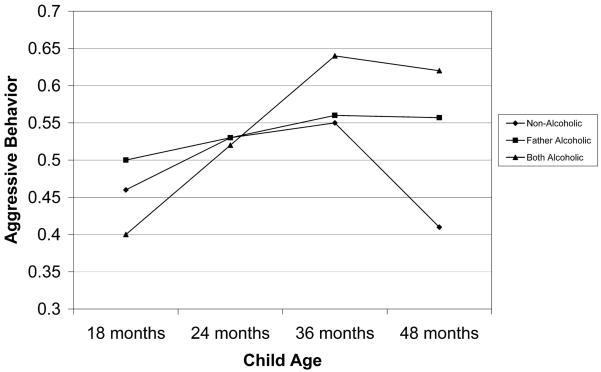

We also hypothesized that the relationship between parents’ alcoholism, risk, and child aggressive behavior would be different for boys and girls. In order to examine this hypothesis, we used the cumulative risk variable and the two dummy coded alcohol group variables as covariates predicting intercept and slope quadratic factor of aggression for boys and girls separately. The quadratic model with a fixed linear slope fit the data well for both boys and girls (see Table III). Results indicated that for boys, risk was significantly associated with the intercept (β = .50, t = 4.85, p < .001), but not the quadratic slope (β = −.37, t = −1.15). Having two alcoholic parents was significantly associated with the quadratic slope factor (β = −.74, t = −2.18, p < .05), but not with the intercept factor (β = −.17, t = −1.60). Boys with higher levels of family risk had higher initial aggressive behavior than boys with lower levels of risk. Boys with two alcoholic parents had significantly less of a decline in aggression from 36 to 48 months compared to boys in the nonalcoholic group (see Fig. 2). For girls, cumulative risk was significantly associated with the intercept (β = .54, t = 5.21, p < .001), but not the quadratic factor (β = −.44, t = 1.15). The dummy coded alcohol variables were not associated with the intercept or quadratic factors. Results indicated that girls with high levels of familial risk had significantly higher levels of aggressive behavior at 18 months than girls with lower levels of risk. There was also a significant negative association between the intercept and the quadratic slope factor (r = −.37) indicating that girls with high levels of aggressive behavior at 18 months of age had a lower rate of decrease over time.

Table III.

Nested Models for Boys’ and Girls’ Aggression Trajectories with Alcohol Group as a Predictor

| χ2 | df | p | CFI | RMSEA | χ2 Δ | df Δ | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 65.53 | 17 | .00 | .79 | .16 | |||

| Model 2 | 53.15 | 11 | .00 | .82 | .18 | 12.38 | 6 | ns |

| Model 3 | 10.17 | 7 | .18 | .99 | .06 | 42.98 | 4 | <.001 |

| Model 4 | 9.36 | 7 | .28 | .99 | .05 | 43.79 | 4 | <.001 |

| Girls | ||||||||

| Model 1 | 100.10 | 17 | .00 | .68 | .21 | |||

| Model 2 | 78.79 | 11 | .00 | .74 | .24 | 21.31 | 6 | <.01 |

| Model 3 | 9.05 | 7/ | .25 | .99 | .05 | 69.74 | 4 | <.001 |

| Model 4 | 8.06 | 7 | .33 | 1.0 | .04 | 70.73 | 4 | <.001 |

Note. Model 1: random intercept only; Model 2: random intercept and random linear slope; Model 3: linear model (fixed quadratic slope and random linear slope); Model 4: quadratic model (fixed linear slope and random quadratic slope). Change in Model 4 χ2 is relative to Model 2.

Fig. 2.

Model implied growth trajectory for boys’ aggression.

Finally, exploratory analyses were conducted to examine the number of children in the clinical range by alcohol group status and child age. For purposes of research, Achenbach (1992) recommends the use of 67 as a cutpoint for the base of the clinical range, as T-scores of 67 have been shown to discriminate between referred and nonreferred aggressive children (Achenbach, 1992). Results indicated that at 18 months, 4% of children in the nonalcoholic group were in the clinical range on the aggression subscale, compared to 3% in the father alcoholic group and none in the both alcoholic group. At 24 months, there was a shift, with .01% of the nonalcoholic group in the clinical range, compared to 5.5% of the father alcoholic group, and 6.5% of the both alcoholic group. At 36 months, the percentages were 3% of the nonalcoholic group, 12% of the father alcoholic group, and 8% of the both alcoholic group. At 48 months, 5.4% of the non-alcoholic group were in the clinical range, compared to 22% of the father alcoholic group, and 18% of the both alcoholic group.

DISCUSSION

As a whole, children in the present study followed normative aggressive behavior trajectories, with aggressive behavior increasing until 3 years of age and then decreasing from three to 4 years of age. This trend reflects the typical development of self-regulatory behaviors during this period. However, when group differences were examined, children in families with nonalcoholic parents had the lowest levels of aggressive behavior at all time points compared to children with one or more alcoholic parents (see Fig. 1). Further, children with two alcoholic parents did not evidence a normative decrease in aggressive behavior from 36 to 48 months of age as compared to nonalcoholic families. However, when cumulative risk was added to the model, neither it nor parent alcoholism predicted quadratic slope, perhaps because of shared variance of these variables. Risk did, however, predict initial levels of child aggressive behavior. The effects of alcoholism and familial risk were moderated by child gender differences. As expected and consistent with previous literature, boys had higher levels of aggressive behavior at all ages than girls, regardless of group status. Cumulative risk was predictive of higher levels of aggressive behavior in both boys and girls at 18 months of age. However, boys with two alcoholic parents had significantly less decline in aggression from 36 to 48 months of age compared to the boys in the nonalcoholic group.

Findings emphasize the nested nature of risk characteristics as described by transactional theories of development (Rutter, 1987; Sameroff et al., 1993; Seifer, 1995; Zeanah, Boris, & Larrieu, 1997). While the characteristics studied may individually predict the development of aggressive behavior, transactional theorists highlight the importance of studying aggregations of risk, providing an opportunity to examine the overall context of development with regard to parent, child, and family characteristics. This is an approach particularly well suited to the study of alcoholic families who often differ substantially in risk structure (Zucker et al., 1995).

Few studies have specifically examined developmental trajectories in aggressive and oppositional behavior among girls from the toddler to the preschool period. However, in the present study, the pattern of aggressive behavior trajectories for girls with high levels of family risk is similar to those obtained by other studies in later childhood (see Broidy et al., 2003). In general, across multiple data sets, girls’ aggression trajectories were noted to exhibit patterns of stability or a slow decline in middle childhood, instead of increasing patterns of aggressive behavior across time, with a small portion of girls exhibiting higher rates of aggressive behavior at Time 1 and remaining stable at that higher level across time. Our results suggest that the girls in high risk families may be exhibiting that pattern, with higher rates of aggression at the initial time point that then remains stable. More research in this area is clearly needed.

Gender results in the current study are reflective of the considerable literature on the particular vulnerability of boys to the effects of having alcoholic parents (Carbonneau et al., 1998; Loukas et al., 2003; Tarter et al., 1997; Zucker et al., 1995). Whereas family risk predicted initial levels of aggression at 18 months of age, having two alcoholic parents accounted for the lack of a normative decrease in aggressive behavior at 3 years of age. This result is consistent with the work of Loukas et al. (2003) who found that paternal alcoholism was associated with higher levels of disruptive behavior problems, above and beyond family conflict and child temperamental characteristics. The literature on children of alcoholic parents suggests that one pathway to maladjustment among these children is through the associations between early behavioral undercontrol to externalizing behavior problems to conduct disorder to delinquency (Tarter & Vanyukov, 1994; Zucker, 1991), a pattern seen primarily in boys. In a previous study, we found that 3-year-old sons with alcoholic fathers had lower levels of inhibitory control compared to sons of nonalcoholic fathers (Eiden, Edwards et al., 2004). Thus, it is possible that the boys of alcoholic parents in the present study have failed to develop the self-regulatory abilities expected of preschoolers, as evidenced by their high levels of aggressive and oppositional behavior.

It is important to note that over time the percentage of children in the clinically significant range of aggressive behavior increased in both alcohol groups. Children demonstrating a pattern of externalizing behavior with early onset and high continuity throughout childhood may be particularly at risk for later maladaptation (Patterson, Capaldi, & Bank, 1991). While these children generally start with milder forms of aggressive and noncompliant behavior, their conduct problems may become more serious over time (McMahon, 1994) and may lead to adolescent antisocial behavior. Continued study of these trajectories over time will be important. There are some limitations to the present study. First, although observational measures of parenting are included in the cumulative risk score, the measure of children’s aggression was based on parent reports as were measures of parents’ alcohol problems. However, it should be noted that the self-report information on alcohol problems was corroborated by the spouse in the initial screening interview. Further, it has been found that parent report on childhood behavior predicts later objective outcomes in children and thus may be viewed as a valid means of assessment (Stanger, MacDonald, McConaughy, Achenbach, 1996). Second, deriving our sample from birth records has important advantages over newspaper or clinic-based samples, but it should be noted that there are also limitations. The response rate to our open letter of recruitment to all families with infants between 10 and 12 months of age was slightly above 25%. This raises the possibility that respondents to our recruitment may have been a biased group. Our comparison of respondents with the entire population of birth records suggested that the bias was small with respect to the variables that we could examine (see Eiden et al., 1999). However, there could have been more significant biases in variables that we could not assess. Further, it should be noted that the sample was largely homogenous, consisting of predominantly White, educated, two-parent, dual earner families, and thus the results may be somewhat conservative; the ability to generalize these results to other groups is, therefore, unclear. However, the results with regard to children’s aggression are particularly salient given that this is a generally well functioning, community sample. Third, given the nature of the design, the role of maternal alcohol problems cannot be examined independent from fathers’ alcohol problems. Further, because only a small proportion of the mothers in our sample experienced alcohol problems, our ability to fully examine the role of maternal alcohol problems was limited. However, it is important to note that in the majority of families with alcohol problems, maternal alcohol problems exist in the context of paternal alcohol problems. In other words, women with alcohol problems are more likely to have partners with alcohol problems than vice versa (see Roberts & Leonard, 1997 for further discussion). Future studies including samples of mothers with and without alcoholic partners may be able to better answer the question of the role of maternal alcohol problems in the development of aggression. Finally, the cutoffs used to create the composite risk indices are sample specific and, while consistent with methods used in other studies (e.g., Sameroff et al., 1993), may not generalize beyond this study. This is partly because many of the measures used to create the risk indices do not have clear clinical cut-offs (e.g., temperament, parental negative affect, etc.).

The need for further research on aggression in the early years is clear. As articulated by Broidy et al. (2003), “because the available data indicate that physical aggression increases dramatically during the second year after birth, the search for the mutual influences of the disruptive behavior will need to start with the first year of life” (p. 236). It has been shown that children are at, or close to, their highest levels of disruptive behavior when they enter kindergarten (Broidy et al., 2003). As early as preschool, moderate to severe behavior problems have been shown to be resistant to change and predictive of later dysfunction (Campbell, 1995). However, although Nagin and Tremblay (1999) found that aggressive and oppositional male adolescents were aggressive and oppositional boys, only 1 in 8 of such children maintained these externalizing behaviors into adolescence. In other words, while early acting out behaviors were always present in these adolescents, they did not ensure later maladaptation. In fact, the majority of aggressive and oppositional boys simply outgrew these behaviors between kindergarten and 15 years of age. Considerable heterogeneity exists in outcomes among children of alcoholic parents as well (Johnson & Jacob, 1995). Results emphasize the importance of focusing on multiple predictors of child risk in these families. Future studies are needed to explore what child and family factors serve to exacerbate or maintain child aggressivity in the preschool years and what factors may serve to protect against such a trajectory.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank parents and infants who participated in this study and the research staff who were responsible for conducting numerous assessments with these families. This study was made possible by grants from NIAAA (#1RO1 AA 10042-01A1) and NIDA (1K21DA00231-01A1).

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist/2–3 and 1992 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for ASEBA preschool forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C, Howell C. Empirically based assessment of the behavioral/emotional problems of 2- and 3-year-old children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1987;15:629–650. doi: 10.1007/BF00917246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreason NC, Rice J, Endicott J, Reich T, Coryell W. The family history approach to diagnosis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:421–429. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800050019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony JC, Warner LA, Kessler RC. Comparative epidemiology of dependence on tobacco, alcohol, controlled substances, and inhalants: Basic findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1994;2:244–268. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. ADHD and the nature of self-control. Worcester, MA: University of Massachusetts Medical Center; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Freeland CAB, Lounsbury ML. Measurement of infant difficultness. Child Development. 1979;50:794–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Woodworth S, Crnic K. Trouble in the second year: Three questions about family interaction. Child Development. 1996;67:556–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd JH, Weissman MM, Thompson WD, Myers JK. Screening for depression in a community sample: Understanding the discrepancies between depression syndrome and diagnostic scales. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1982;39:1195–1200. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290100059010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broidy LM, Nagin DS, Tremblay RE, Bates JE, Brame B, Dodge KA, et al. Developmental trajectories of childhood disruptive behaviors and adolescent delinquency: A six-site, cross-national study. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:222–245. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, Gerard JM. Marital conflict, ineffective parenting, and children’s and adolescents’ maladjustment. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2002;64:78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB. Behavior problems in preschool children: A review of recent research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1995;36:113–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Pierce EW, Moore G, Marakovitz S, Newby K. Boys’ externalizing problems at elementary school age: Pathways from early behavior problems, maternal control, and family stress. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:701–719. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonneau R, Tremblay RE, Vitaro F, Dobkin PL, Saucier JF, Pihl RO. Paternal alcoholism, paternal absence and the development of problem behaviors in boys from age six to twelve years. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:387–398. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Newman DL, Silva PA. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders: Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:1033–1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110071009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Silva PA. Temperamental qualities at age three predict personality traits in young adulthood: Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Child Development. 1995;66:486–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan AWK, Welte JW, Russell M. Screening for heavy drinking/alcoholism by the TWEAK test. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1993;17:463. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. The Parent–Child Early Relational Assessment: A factorial validity study. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1999;59:821–846. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Moss HB, Kirisci L, Mezzich AC, Miles R, Ott P. Psychopathology in preadolescent sons of fathers with substance use disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:495–502. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Musick J, Scott F, Klehr K. The mothers’ project rating scales of mother–child interaction. 1980 Unpublished document. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(2):179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté S, Tremblay RE, Nagin DS, Zoccolillo M, Vitaro F. Childhood behavioral profiles leading to adolescent conduct disorder: Risk trajectories for boys and girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:1086–1094. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Zahn-Waxler C. The development of psychopathology in females and males: Current progress and future challenges. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:719–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Iannotti RJ, Zahn-Waxler C. Aggression between peers in early childhood: Individual continuity and developmental change. Child Development. 1989;60:887–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb03521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bollen KA. The best of both worlds: Combining autoregressive and latent curve models. In: Collins LM, Sayer AG, editors. New methods for the analysis of change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes MA, Tarter RE, Kirisci L. Behavioral self-regulation: Correlates and 2 year follow-ups for boys at risk for substance abuse. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;45:165–176. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01359-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Strycker LA, Li F, Alpert A. An introduction to latent variable growth curve modeling. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards EP, Leonard KE, Eiden RD. Temperament and behavioral problems among infants in alcoholic families. Journal of Infant Mental Health. 2001;22:374–392. doi: 10.1002/imhj.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Chavez F, Leonard KE. Parent–infant interactions in alcoholic and control families. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:745–762. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Edwards EP, Leonard KE. Mother–infant and father–infant attachment among alcoholic families. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:253–378. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402002043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Edwards EP, Leonard KE. Pathways to effortful control among children of alcoholic and non-alcoholic fathers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65 doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Leonard KE, Hoyle RH, Chavez F. A transactional model of parent–infant interactions in alcoholic families. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:350–361. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Bernzweig J, Karbon M, Poulin R, Hanish L. The relations of emotionality and regulation to preschoolers’ social skills and sociometric status. Child Development. 1993;64:1418–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Zhou Q, Losoya SH, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Murphy BC, et al. The relations of parenting, effortful control, and ego control to children’s emotional expressivity. Child Development. 2003;74:875–895. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emde RN, Biringen Z, Clyman RB, Oppenheim D. The moral self of infancy: Affective core and procedural knowledge. Developmental Review. 1991;11:251–270. [Google Scholar]

- Ensel WM. The role of age in the relationship of gender and marital status to depression. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1982;170:536–543. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198209000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald HE, Jones MA, Maguin E, Zucker RA, Noll RB. Assessing parental antisocial behavior in alcoholic and nonalcoholic families. 1991. Unpublished Work. [Google Scholar]

- Frosch CA, Mangelsdorf SC. Marital behavior, parenting behavior, and multiple reports of preschoolers’ behavior problems: Mediation or moderation? Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:502–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griest DL, Forehand R, Wells KC, McMahon RJ. An examination of differences between nonclinic and behavior-problem clinic-referred children and their mothers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1980;89:497–500. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.89.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Conrad B, Fogg L, Willis L, Garvey C. A longitudinal study of maternal depression and preschool children’s mental health. Nursing Research. 1995;44:96–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Evaluating model fit. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. pp. 76–99. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Johnson SL. Sequential interactions in the parent–child communications of depressed fathers and depressed mothers. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:38–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Moffit TE, Caspi A, Taylor A. Life with (or without) father: The benefits of living with two biological parents depend on the father’s antisocial behavior. Child Development. 2003;74:109–126. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen RE, Fitzgerald HE, Ham HP, Zucker RA. Pathways into risk: Temperament and behavior problems in three-to-five year-old sons of alcoholics. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research. 1995;19:501–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Jacob T. Psychosocial functioning in children of alcoholic fathers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1995;9:101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S, Leonard KE, Jacob T. Drinking, drinking styles, and drug use in children of alcoholics, depressives, and controls. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:427–431. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Shaw D. Developmental and social influences on young girls’ early problem behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:95–113. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12 month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim IJ, Ge X, Brody GH, Conger RD, Gibbons FX, Simons RL. Parenting behaviors and the occurrence and co-occurrence of depressive symptoms and conduct problems among African American children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17(4):571–583. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Mutually responsive orientation between mothers and their young children: Implications for early socialization. Child Development. 1997;68:94–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Tjebkes TL, Forman DR. Children’s emerging regulation of conduct: Restraint, compliance, and internalization from infancy to the second year. Child Development. 1998;69:1378–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB. Antecedents of self-regulation: A developmental perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:199–214. [Google Scholar]

- Lagerspetz KM, Björkqvist K, Peltonen T. Is indirect aggression typical of females: Gender differences in aggressiveness in 11- to 12-year-old children. Aggressive Behavior. 1988;14:403–414. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Eiden RD, Wong MM, Zucker RA, Puttler LI, Fitzgerald HE, et al. Developmental perspectives on risk and vulnerability in alcoholic families. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:238–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Quigley BM. Drinking and marital aggression in newlyweds: An event-based analysis of drinking and the occurrence of husband marital aggression. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:537–545. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little R, Rubin D. The analysis of social science data with missing values. Sociological Methods and Research. 1989;18:292–326. [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA, von Eye A. Parental alcoholism and co-occurring antisocial behavior: Prospective relationships to externalizing behavior problems in their young sons. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:693–697. doi: 10.1023/a:1005281011838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A, Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE, Krull JL. Developmental trajectories of disruptive behavior problems among sons of alcoholics: Effects of parent psychopathology, family conflict, and child undercontrol. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:119–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons-Ruth K, Lyubchik A, Wolfe R, Bronfman E. Parental depression and child attachment: Hostile and helpless profiles of parent and child behavior among families at risk. In: Goodman SH, Gotlib IH, editors. Children of depressed parents: Mechanisms of risk and implications for treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 89–202. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon R. Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of externalizing problems in children: The role of longitudinal data. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:901–917. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.5.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Dickson N, Silva P, Stanton W. Childhood-onset versus adolescent-onset antisocial conduct problems in ales: Natural history from ages 3 to 18 years. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:399–424. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, O’Farrell TJ. Marital violence among alcoholics. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1996;5:183–186. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 2. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS, Tremblay R. Trajectories of boys’ physical aggression, opposition, and hyperactivity on the path to physically violent and non-violent juvenile delinquency. Child Development. 1999;70:1181–1196. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien MJ, Bahadur MA. Marital aggression, mother’s problem-solving behavior with children, and children’s emotional and behavioral problems. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1998;17:249–272. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe M. Adjustment of children from maritally violent homes. Family and Society. 1994;75:403–415. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. A social learning approach: Vol. 3. Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Capaldi DM. Antisocial parents: Unskilled and vulnerable. In: Cowan PA, Hetherington EM, editors. Family Transitions. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 195–217. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Capaldi D, Bank L. An early starter model for predicting delinquency. In: Pepler DJ, Rubin KH, editors. The development and treatment of childhood aggression. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 139–168. [Google Scholar]

- Puttler LI, Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE, Bingham CR. Behavioral outcomes among children of alcoholics during the early and middle childhood years: Familial subtype variations. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:1962–1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley BM, Leonard KE. Alcohol and the continuation of early marital aggression. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:1003–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Richman N. Behaviour problems in pre-school children: Family and social factors. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1979;131:523–527. doi: 10.1192/bjp.131.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LJ, Leonard KE. Gender differences and similarities in the alcohol and marriage relationship. In: Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, editors. Gender and alcohol: Individual and social perspectives. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies; 1997. pp. 289–311. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK. Biological processes in temperament. In: Kohnstamm GA, Bates JA, Rothbart MK, editors. Temperament in childhood. New York: Wiley; 1989. pp. 77–110. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, Fisher P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The children’s behavior questionnaire. Child Development. 2001;72:1394–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987;147:598–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, Baldwin A, Baldwin C. Stability of intelligence from preschool to adolescence: The influence of social and family risk factors. Child Development. 1993;64:80–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifer R. Perils and pitfalls of high-risk research. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:420–424. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby EM, Nagin DS. Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spieker SJ, Larson NC, Lewis SM, Keller RE, Gilchrist L. Developmental trajectories of disruptive behavior problems in preschool children of adolescent mothers. Child Development. 1999;70:443–458. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanger C, MacDonald VV, McConaughy SS, Achenbach TM. Predictors of cross-informant syndromes among children and youths referred for mental health services. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1996;24:597–614. doi: 10.1007/BF01670102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intra family conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE. Are there inherited behavioral traits that predispose to substance abuse? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:189–196. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Clark DB. Alcohol use disorder among adolescents: Impact of paternal alcoholism on drinking behavior, drinking motivation, and consequences. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1997;21:171–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1997.tb03745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Vanyukov M. Alcoholism: A developmental disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:1096–1107. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.6.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Vanyukov M, Giancola P, Dawes M, Blackson T, Mezzich A, et al. Etiology of early age onset substance use disorder: A maturational perspective. Developmental Psychopathology. 1999;11:657–683. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay RE. The development of aggressive behavior during childhood: What have we learned in the past century? International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2000;24:129–141. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay RE, Boulerice B, Harden PW, McDuff P, Pérusse D, Pihl RO, et al. Human Resources Development Canada and Statistics Canada. Growing up in Canada: National longitudinal survey of children and youth. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 1996. Do children in Canada become more aggressive as they approach adolescence? pp. 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- White JL, Moffitt TE, Earls F, Robins L, Silva PA. How early can we tell? Criminology. 1990;28:507–533. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, DuHamel K, Vaccaro D. Activity and mood temperament as predictors of adolescent substance use: Test of a self-regulation mediational model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:901–916. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.5.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]