Abstract

The prognosis of children with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is very poor. Radiotherapy remains the standard treatment for these patients, but the median survival time is only 9 months. Currently, the use of concurrent radiotherapy with temozolomide (TMZ) has become the standard care for adult patients with malignant gliomas. We therefore investigated this approach in 12 children diagnosed with DIPG. The treatment protocol consisted of concurrent radiotherapy at a dose of 55.8–59.4 Gy at the tumor site with TMZ (75 mg/m2/ day) for 6 weeks followed by TMZ (200 mg/m2/day) for 5 days with cis-retinoic acid (100 mg/m2/day) for 21 days with a 28-day cycle after concurrent radiotherapy. Ten of the 12 patients had a clinical response after the completion of concurrent radiotherapy. Seven patients had a partial response, four had stable disease, and one had progressive disease. At the time of the report, 9 of the 12 patients had died of tumor progression, one patient was alive with tumor progression, and two patients were alive with continuous partial response and clinical improvement. The median time to progression was 10.2 ± 3.0 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.2–16.1 months). One-year progression-free survival was 41.7% ± 14.2%. The median survival time was 13.5 ± 3.6 months (95% CI, 6.4–20.5 months). One-year overall survival was 58% ± 14.2%. The patients who had a partial response after completion of concurrent radiotherapy had a longer survival time (p = 0.036) than did the other patients (those with stable or progressive disease). We conclude that the regimen of concurrent radiotherapy and TMZ should be considered for further investigation in a larger series of patients.

Keywords: children, cis-retinoic acid, concurrent radiotherapy, diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma, temozolomide

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) accounts for 80% of pediatric brainstem tumors and approximately 10% of all pediatric brain tumors,1 with peak incidence between 5 and 8 years of age. Owing to the tumor location, the diagnosis of DIPG depends on clinical signs and symptoms and characteristic MRI findings.1 The prognosis of children with newly diagnosed DIPG is very poor. Conventionally fractionated local radiotherapy remains the standard care, leading to transient clinical improvement in a substantial percentage of patients. To date, the role of chemotherapy in the treatment of children with DIPG is not well defined.

Various treatment modalities have been studied, such as preradiation chemotherapy followed by conventional radiotherapy,2,3 preradiation chemotherapy followed by hyperfractionated radiotherapy,4,5 hyperfractionated radiotherapy alone,6,7 concurrent chemotherapy with radiotherapy,2,8–12 conventional radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy,13,14 and conventional high-dose chemotherapy with stem cell rescue.15 However, survival remains poor.

Temozolomide (TMZ), an oral alkylating agent, can efficiently cross the blood-brain barrier16 and has been shown to lengthen progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with high-grade glioma. Several reports have found that TMZ given concurrently with radiotherapy resulted in better survival for patients with high-grade gliomas.17–19 cis-Retinoic acid (cis-RA), a synthetic analogue of vitamin A, can also inhibit the growth of glioma cells by decreasing affinity for binding between the epidermal growth factor and the epidermal growth factor receptor, inhibiting the expression of tenacin-C, and increasing p55 tumor necrotic factor alpha receptors.20–23 The combination of TMZ and cis-RA was shown to be effective in recurrent or progressive malignant gliomas24 and in newly diagnosed supratentorial glioblastomas.25 However, this approach has never been evaluated in the treatment of DIPG. In an effort to improve the dismal DIPG outcomes, we initiated the current series.

Patients and Methods

Eligibility

Previously untreated patients ⩽18 years of age with DIPG newly diagnosed by clinical presentation and MRI were studied. No pathological confirmation was performed. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University.

Treatment

After informed consent, patients received local field conventional radiotherapy at a dose of 55.8–59.4 Gy in 31–33 fractions within 6–6.5 weeks. During radiotherapy, all patients received TMZ (75 mg/m2/day) orally for 6 weeks. Two weeks after the completion of concurrent radiotherapy with TMZ, patients received TMZ (200 mg/m2/day for 5 days) and cis-RA (100 mg/m2/ day for 21 days) orally in 28-day cycles. The combination of TMZ and cis-RA after concurrent radiotherapy was continued until tumor progression was observed on MRI. The MRI studies were reevaluated at 2 weeks after the completion of concurrent radiotherapy with TMZ and at 3-month intervals or as indicated by clinical neurological examination. Complete blood counts and blood chemistry series were performed before and during each cycle of chemotherapy.

Radiological Evaluation

The outline of tumor demonstrated by hyperintensity in T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images was manually traced by a trackball-driven cursor on consecutive axial images, and the tumor volume was calculated by software in a standard 1.5-T MR scanner equipped with a superconductive magnet (model NVi/ CVi, software version 9.1; General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA) and a 3-T MR scanner (Achieva, software version 11; Philips, Best, Netherlands). The tumor volume was evaluated by MRI prior to concurrent radiotherapy, after the completion of concurrent radiotherapy, and at 3-month intervals or as indicated by clinical neurological examination. A complete response (CR) was defined as a disappearance of the lesion. A partial response (PR) was defined as a ⩾50% reduction of tumor volume. Progressive disease (PD) was defined as an increase of tumor volume by.25%. Other responses were classified as stable disease (SD).

Proton spectroscopy was performed as an additional diagnostic and response evaluation tool. The analyzed metabolites were N-acetylaspartate (NAA), cholinecontaining compounds (Cho), and creatine and phosphocreatine (Cr). NAA is found in normal neurons and is reduced in brain tumor cells. Cho reflects membrane synthesis and degradation. Cr, which is relatively constant and reflects energy metabolism, was used as a reference to normalize signal intensity of other metabolites. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) was used to identify tumor grading. High-grade gliomas tend to have a high Cho/Cr ratio and low NAA/Cr ratio. MRS was also used to evaluate the response to treatment.

Toxicity

The toxicities from chemotherapy were monitored and graded based on the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0.26

Statistical Analysis

Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier.27 Standard error estimates were calculated using the method described by Peto et al.28 PFS reflected the interval between diagnosis and clinical and/or radiological tumor progression or death. OS was defined as the interval between diagnosis and death.

Results

Twelve patients (three males, nine females) were enrolled. The median age (interquartile range) at presentation was 4.2 (2.2) years (Table 1). The median duration (interquartile range) of the initial symptoms until the first visit was 1.5 (4.2) months.

Table 1.

Characteristics and findings for the 12 pediatric patients with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma

| Age at Diagnosis

(Years) |

Imaging Response after RT

(% Reduction) |

MRS

Cho/Cr Ratio |

MRS

NAA/Cr Ratio |

Time to Progression

(Months) |

Follow-up Time

(Months) |

Current Status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Sex | Before RT | After RT | Before RT | After RT | |||||

| 1 | M | 3.5 | 79.0 (PR) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | — | 42.33 | A/W |

| 2 | F | 5.1 | 76.0 (PR) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 10.6 | 11.5 | DOD |

| 3 | F | 5.5 | 9.0 (SD) | 3:1 | 2.2:1 | 0.5:1 | 0.5:1 | 6.0 | 7.9 | DOD |

| 4 | M | 3.2 | PD | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3.7 | 13.5 | DOD |

| 5 | F | 4.0 | 63.0 (PR) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 10.2 | 15.7 | DOD |

| 6 | F | 4.3 | 88.0 (PR) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 17.3 | 27.5 | A/P |

| 7 | F | 3.6 | 68.0 (PR) | 3:1 | 1.6:1 | 1.7:1 | 0.9:1 | 12.4 | 16.2 | DOD |

| 8 | F | 5.8 | 49.0 (SD) | 2.25:1 | 2:1 | 0.7:1 | 0.7:1 | 7.1 | 7.1 | DOD |

| 9 | F | 4.0 | 82.0 (PR) | 3:1 | 1.6:1 | 1:1 | 1:1 | 6.9 | 11.1 | DOD |

| 10 | M | 2.8 | 69.4 (PR) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | — | 18.7 | A/W |

| 11 | F | 9.1 | 46.2 (SD) | 1.7:1 | 1.7:1 | 0.8:1 | 0.8:1 | 11.2 | 16.7 | DOD |

| 12 | F | 8.0 | 13.4 (SD) | 2.8:1 | 2.5:1 | 0.5:1 | 0.5:1 | 5.0 | 6.9 | DOD |

Abbreviations: RT, radiotherapy; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; Cho, choline; Cr, creatine; NAA, N-acetylaspartate; M, male; PR, partial response; N/A, not applicable; A/W, alive and well; F, female; DOD, died of disease; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; A/P, alive with progression.

A clinical response after the completion of concurrent radiotherapy, confirmed by neurological examination with a pediatric neurologist, was observed in 10 of the 12 patients. The imaging response after the completion of concurrent radiotherapy was evaluated in all patients: seven patients had PR, four had SD, and one had PD. The median (interquartile range) reduction of tumor volume was 65.5% (56.7%) for all patients.

We used MRS to determine the Cho/Cr and NAA/ Cr ratios at the center of the tumors before and after the completion of concurrent radiotherapy in only six patients. The results showed that the Cho/Cr ratio was high (.2:1 in five of the six patients), indicating a malignant tumor spectrum before concurrent radiotherapy and then markedly reduced, corresponding to severe neuronal loss after the completion of concurrent radiotherapy in all six patients except patient 11. The significantly decreased Cho/Cr ratio after the completion of concurrent radiotherapy indicated a favorable response. The NAA/Cr ratio did not change in most of these evaluated patients, however, due to permanent neuronal damage prior to concurrent therapy.

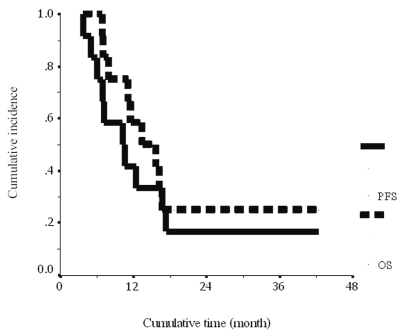

At the time of the report, nine patients had died of disease progression, one patient had disease progression, and two patients had a continuous PR with clinical improvement. The median follow-up time was 14.5 months. The median time to progression was 10.2 ± 3.0 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.2–16.1 months). The 1-year PFS was 41.7% ± 14.2% (Fig. 1). The median survival time was 13.5 ± 3.6 months (95% CI, 6.4–20.5 months). The 1-year OS was 58% ± 14.2% (Fig. 1). Interestingly, one patient (patient 1) was still alive at 42 months, with a continuous PR and clinical improvement.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative progression-free survival (solid line) and overall survival (dashed line) for the 12 pediatric patients with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma.

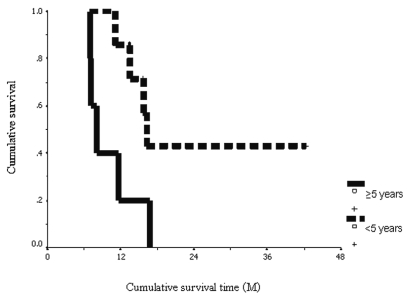

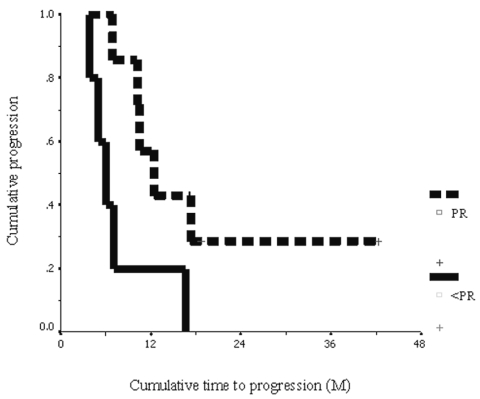

Prognostic markers including age at diagnosis, sex, and imaging response after concurrent radiotherapy were studied. The subgroup of patients whose age at diagnosis was younger than 5 years (n = 7) had a significant longer median OS time than did those patients older than 5 years (n = 5) (16.2 ± 0.7 months compared with 7.9 ± 0.9 months, p = 0.036). The 1-year OS in the subgroup of patients whose age at diagnosis was younger than 5 years was 85.7% ± 13.2% compared with 20% ± 17.9% for those older than 5 years (Fig. 2). We also found that patients who had PR (⩾50% reduction of tumor volume) (n = 7) after the completion of concurrent radiotherapy had a significant longer median time to progression than did the others (SD plus PD) (12.4 ± 2.4 months compared with 6.0 ± 1.1 months, p = 0.036). The 1-year PFS rate in the subgroup of patients who had a PR after the completion of concurrent radiotherapy was 57.1% ± 18.7% compared with 20% ± 17.9% for the other patients (SD plus PD) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Cumulative overall survival: patients,5 years of age (dashed line) and ⩾5 years of age (solid line), in months (M).

Fig. 3.

Cumulative progression-free survival: patients with a partial response (⩾50% reduction of tumor volume by MRI) after the completion of concurrent radiotherapy and temozolomide (dashed line) and patients with response less than partial response (<50%) (solid line), in months (M).

Two patients developed grade 3 and 4 myelotoxicity. Patient 2 had two episodes of thrombocytopenia and required platelet transfusions. Patient 5 had five episodes of neutropenia; however, this patient required antibiotic treatment for only one episode of fever associated with neutropenia. Nausea and vomiting developed in all patients and resolved over the treatment course. Maculopapular rash developed in one patient and resolved spontaneously without treatment.

Discussion

Radiation remains the standard treatment of choice for DIPG, and, to date, chemotherapy has not shown any increased benefit.6,29 However, only a few studies have assessed the role of chemotherapy, whereas most prospective studies have investigated alternative radiation options such as hyperfractionation,1,4,6,7,9,11,29,30 rather than combinations with chemotherapy.1–3,5,8,10,12–15,31,32 Studies have concluded that standard conventional radiotherapy is as efficient as alternative radiation techniques. Overall, the outlook remains poor, and nearly all children eventually die of their disease, with most studies showing median survival times of less than 1 year.1

Various chemotherapeutic agents investigated as single neoadjuvant agents (carboplatin2 or irinotecan14) or as a combination of several neoadjuvant agents (carboplatin, etoposide, and vincristine or cisplatinum, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, and vincristine3) offered no significant improvements compared with previous findings.1 Similarly, other approaches, using chemotherapeutic agents such as etanidazole,9 topotecan,10 and carboplatin as radiosensitizers,5 or high-dose chemotherapy administration with a preparative regimen consisting of bulsulfan and thiotepa15 followed by stem cell support, have also been investigated, again without any improvements in progression or survival time.

TMZ generated great excitement as the first drug commercially released in the last two decades to show significant activity against a subset of high-grade gliomas in adults. Despite the initial positive responses observed among children with high-grade gliomas treated in phase I trials, Broniscer et al.14 showed that administration of TMZ after radiotherapy, as an adjuvant therapy, does not change the poor outcome of children with newly diagnosed DIPG. Their results corroborate the findings of a recent phase II multi-institutional trial that reported a disappointing response to TMZ in children with recurrent gliomas.33 Stupp et al.17 reported promising survival rates in adult patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme treated with concomitant radiation plus TMZ followed by adjuvant TMZ, while Jaeckle et al.24 have reported TMZ and cis-RA being active in recurrent and progressive malignant gliomas. Consequently, we decided to evaluate the efficacy of concurrent radiotherapy with TMZ, followed by adjuvant TMZ combined with cis-RA, in our patients with DIPG.

In studies of the outcomes of DIPG treatment with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, the median times to progression ranged from 5 to 8.8 months, while the OS values ranged from 7 to 16 months, suggesting that survival rates differed with different treatment strategies.2–15 If we include only studies for which clinical and radiological eligibility criteria were specified, the median OS ranged from 8 to 11 months.1 Our current study found a 1-year PFS of 41.7% ± 14.2% with a median time to progression of 10.2 ± 3.0 months (95% CI, 4.2–16.1 months); the 1-year OS was 58% ± 14.2% with a median survival time of 13.5 ± 3.6 months (95% CI, 6.4–20.5 months). Our study seemed to achieve longer median times of progression and survival rates compared with previous studies.1

Interestingly, the seven of 12 patients who had PR after the completion of concurrent radiotherapy with TMZ had longer progression time and survival time compared with the patients with a lesser response. Moreover, only patients 1 and 10, who are still alive and well without evidence of progression of their disease, were younger than 5 years and had a reduction in tumor volume of.50% after concurrent radiotherapy with TMZ. We suggest that concurrent radiotherapy with TMZ may play a role in improving outcomes in this group of patients.

Six of the 12 patients in our study had MRS studies performed before and after the completion of concurrent radiotherapy with TMZ, and we observed a decline in Cho/Cr ratios in most of the evaluated patients after completion of concurrent radiotherapy. Moreover, patients 7 and 9, with the most dramatic reduction in the Cho/Cr ratio, had PR after the completion of concurrent radiotherapy, whereas the other four patients, who had a lesser reduction (or no reduction) in the Cho/Cr ratio, had SD. We suggest that both MRI and MRS studies may predict the response and outcome of treatment in this patient group.

In conclusion, our patients seemed to achieve more favorable response rates after the completion of concurrent radiotherapy with TMZ compared with previous published reports,1 in which radiotherapy alone or concurrent radiotherapy with other various chemotherapeutic agents was given. In our study of 12 patients, seven (58%) had PR, four had SD, and one had PD. Because of the favorable response rates after the completion of concurrent radiotherapy with TMZ along with the tendency toward longer OS and minimal toxicities and the small number of recruited patients in our study, we suggest that this concurrent radiotherapy regimen and TMZ should be considered for further investigation in a larger series of patients rather than as a novel treatment strategy that should be adopted by all. Furthermore, because long-term outcomes were still not too favorable in the study by Broniscer et al.14 or in our current study, both of which used the same TMZ dose after radiotherapy (200 mg/m2/day for 5 days per cycle), we suggest that a combination of a protracted course of TMZ and other biological agents after concurrent radiotherapy be evaluated as the next research step in improving survival.

Targeted therapy for brain tumors is currently being widely studied. To improve the outcome for this group of patients, novel strategies for the treatment of this tumor, including the use of small molecule inhibitors and novel drug delivery methods, continue to be investigated.1 To identify additional molecules and cellular pathways that can be targeted by these novel strategies, it will be important to better understand the mechanisms associated with the genesis of this neoplasm. The acquisition of tumor tissue specimens for molecular analysis during treatment (when a biopsy is clinically indicated), and particularly at autopsy, will make it possible for investigators to better address these issues.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Kostas Papadopoulos for editing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hargrave D, Bartels U, Bouffet E. Diffuse brainstem glioma in children: critical review of clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:241–248. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70615-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doz F, Neuenschwander S, Bouffet E, et al. Carboplatin before and during radiation therapy for the treatment of malignant brain stem tumours: a study by the Societe Francaise d’Oncologie Pediatrique. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:815–819. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jennings MT, Sposto R, Boyett JM, et al. Preradiation chemotherapy in primary high-risk brainstem tumors: phase II study CCG-9941 of the Children’s Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3431–3437. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.04.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kretschmar CS, Tarbell NJ, Barnes PD, Krischer JP, Burger PC, Kun L. Pre-irradiation chemotherapy and hyperfractionated radiation therapy 66 Gy for children with brain stem tumors: a phase II study of the Pediatric Oncology Group, Protocol 8833. Cancer. 1993;72:1404–1413. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930815)72:4<1404::aid-cncr2820720441>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen J, Siffert J, Donahue B, et al. A phase I/II study of carboplatin combined with hyperfractionated radiotherapy for brainstem gliomas. Cancer. 1999;86:1064–1069. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990915)86:6<1064::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandell LR, Kadota R, Freeman C, et al. There is no role for hyperfractionated radiotherapy in the management of children with newly diagnosed diffuse intrinsic brainstem tumors: results of a Pediatric Oncology Group phase III trial comparing conventional vs. hyperfractionated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:959–964. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00501-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman CR, Krischer J, Sanford RA, et al. Hyperfractionated radiation therapy in brain stem tumors: results of treatment at the 7020 cGy dose level of Pediatric Oncology Group study #8495. Cancer. 1991;68:474–481. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910801)68:3<474::aid-cncr2820680305>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanghavi SN, Needle MN, Krailo MD, Geyer JR, Ater J, Mehta MP. A phase I study of topotecan as a radiosensitizer for brainstem glioma of childhood: first report of the Children’s Cancer Group-0952. Neuro-oncol. 2003;5:8–13. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/5.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcus KJ, Dutton SC, Barnes P, et al. A phase I trial of etanidazole and hyperfractionated radiotherapy in children with diffuse brainstem glioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:1182–1185. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04391-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernier-Chastagner V, Grill J, Doz F, et al. Topotecan as a radiosensitizer in the treatment of children with malignant diffuse brainstem gliomas: results of a French Society of Paediatric Oncology Phase II Study. Cancer. 2005;104:2792–2797. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walter AW, Gajjar A, Ochs JS, et al. Carboplatin and etoposide with hyperfractionated radiotherapy in children with newly diagnosed diffuse pontine gliomas: a phase I/II study. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1998;30:28–33. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199801)30:1<28::aid-mpo9>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolff JE, Westphal S, Molenkamp G, et al. Treatment of paediatric pontine glioma with oral trophosphamide and etoposide. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:945–949. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenkin RD, Boesel C, Ertel I, et al. Brain-stem tumors in childhood: a prospective randomized trial of irradiation with and without adjuvant CCNU, VCR, and prednisone. A report of the Children’s Cancer Study Group. J Neurosurg. 1987;66:227–233. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.66.2.0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broniscer A, Iacono L, Chintagumpala M, et al. Role of temozolomide after radiotherapy for newly diagnosed diffuse brainstem glioma in children: results of a multiinstitutional study (SJHG-98) Cancer. 2005;103:133–139. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouffet E, Raquin M, Doz F, et al. Radiotherapy followed by high dose busulfan and thiotepa: a prospective assessment of high dose chemotherapy in children with diffuse pontine gliomas. Cancer. 2000;88:685–692. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000201)88:3<685::aid-cncr27>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel M, McCully C, Godwin K, Balis FM. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics of intravenous temozolomide in non-human primates. J Neurooncol. 2003;61:203–207. doi: 10.1023/a:1022592913323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stupp R, Dietrich PY, Ostermann Kraljevic S, et al. Promising survival for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme treated with concomitant radiation plus temozolomide followed by adjuvant temozolomide. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1375–1382. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wedge SR, Porteous JK, Glaser MG, Marcus K, Newlands ES. In vitro evaluation of temozolomide combined with X-irradiation. Anticancer Drugs. 1997;8:92–97. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199701000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Rijn J, Heimans JJ, van den Berg J, van der Valk P, Slotman BJ. Survival of human glioma cells treated with various combination of temozolomide and X-rays. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:779–784. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costa SL, Paillaud E, Fages C, et al. Effects of a novel synthetic retinoid on malignant glioma in vitro: inhibition of cell proliferation, induction of apoptosis and differentiation. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:520–530. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouterfa H, Picht T, Kess D, et al. Retinoids inhibit human glioma cell proliferation and migration in primary cell cultures but not in established cell lines. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:419–430. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200002000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benkoussa M, Brand C, Delmotte MH, Formstecher P, Lefebvre P. Retinoic acid receptors inhibit AP1 activation by regulating extracellular signal-regulated kinase and CBP recruitment to an AP1-responsive promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4522–4534. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4522-4534.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gundimeda U, Hara SK, Anderson WB, Gopalakrishna R. Retinoids inhibit the oxidative modification of protein kinase C induced by oxidant tumor promoters. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;300:526–530. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaeckle KA, Hess KR, Yung WK, et al. Phase II evaluation of temozolomide and 13-cis-retinoic acid for the treatment of recurrent and progressive malignant glioma: a North American Brain Tumor Consortium study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2305–2311. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butowski N, Prados MD, Lamborn KR, et al. A phase II study of concurrent temozolomide and cis-retinoic acid with radiation for adult patients with newly diagnosed supratentorial glioblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:1454–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Cancer Institute. [(accessed June 19, 2007)];Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0 (CTCAE) 2006 August 9; Available at http://ctep.cancer.gov/forms/CTCAEv3.pdf.

- 27.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient: (I) Introduction and design. Br J Cancer. 1976;34:585–612. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1976.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hibi T, Shitara N, Genka S, et al. Radiotherapy for pediatric brain stem glioma: radiation dose, response, and survival. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:643–651. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199210000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edwards MS, Wara WM, Urtasun RC, et al. Hyperfractionated radiation therapy for brain-stem glioma: a phase I–II trial. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:691–700. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.70.5.0691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bottom KS, Ashley DM, Friedman HS, Longee DC. Evaluation of preradiotherapy cyclophosphamide in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme: Writing Committee for The Brain Tumor Center at Duke. J Neurooncol. 2000;46:151–156. doi: 10.1023/a:1006258026274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carrie C, Negrier S, Gomez F, et al. Diffuse medulla oblongata and pontine gliomas in childhood: a review of 37 cases. Bull Cancer. 2004;91:E167–E183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lashford LS, Thiesse P, Jouvet A, et al. Temozolomide in malignant gliomas of childhood: a United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group and French Society for Pediatric Oncology Intergroup Study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4684–4691. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]