Abstract

Although both endocrine and the exocrine pancreas display a significant capacity for tissue regeneration and renewal, the existence of progenitor cells in the adult pancreas remains uncertain. Using a model of cerulein-mediated injury and repair, we demonstrate that mature exocrine cells, defined by expression of an Elastase1 promoter, actively contribute to regenerating pancreatic epithelium through formation of metaplastic ductal intermediates. Acinar cell regeneration is associated with activation of Hedgehog (Hh) signaling, as assessed by up-regulated expression of multiple pathway components, as well as activation of a Ptch-lacZ reporter allele. Using both pharmacologic and genetic techniques, we also show that the ability of mature exocrine cells to accomplish pancreatic regeneration is impaired by blockade of Hh signaling. Specifically, attenuated regeneration in the absence of an intact Hh pathway is characterized by persistence of metaplastic epithelium expressing markers of pancreatic progenitor cells, suggesting an inhibition of redifferentiation into mature exocrine cells. Given the known role of Hh signaling in exocrine pancreatic cancer, these findings may provide a mechanistic link between injury-induced activation of pancreatic progenitors and subsequent pancreatic neoplasia.

In mature mammalian tissues, the ability to regenerate following injury implies the presence of cells with progenitor function. In contrast to a model in which tissue regeneration is accomplished through activation and expansion of a rare, dedicated progenitor cell, recent studies have called attention to the ability of differentiated pancreatic cell types to act as facultative progenitor cells, similar to the role defined for differentiated hepatocytes in the context of liver regeneration.1,2 For example, following partial pancreatectomy, it appears that existing insulin-producing cells serve as the source of new β-cells during endocrine regeneration.3 Similarly, it has been suggested that mature acinar cells also retain a facultative progenitor capacity, suggested by their ability to dedifferentiate following exocrine pancreatic injury in vivo4,5 and by their ability to generate dedifferentiated nestin-expressing cells in vitro.6 However, the signaling pathways guiding this progenitor behavior have not been well characterized.

Recent studies investigating mechanisms of exocrine pancreatic regeneration have relied heavily on the induction of epithelial injury by administration of cerulein, a decapeptide analogue of the pancreatic secretagogue cholecystokinin.4,7 Cerulein-induced epithelial injury is recognized to be a fully reversible process, despite the fact that the insult can lead to an almost complete loss of identifiable acinar cells. Acinar cell mass is fully restored within 1 week following cerulein administration, as the result of a potent regenerative response. Jensen et al4 have shown that, in the setting of cerulein-mediated injury, surviving acinar cells repress the terminal exocrine gene program and induce transcripts typically observed in the developing pancreas. More recent lineage tracing studies by Desai et al have confirmed that mature acinar cells are responsible for exocrine regeneration in models of pancreatic injury,5 whereas Strobel et al have excluded a participation by endocrine cells in this process following cerulein pancreatitis.8 Although these series of elegant reports have established a facultative progenitor function for mature acinar cells (“acini beget acini”) and have excluded the possibility of “transdifferentiation promiscuity” in the process of exocrine regeneration, the seminal signaling pathways contributing to this phenomenon remain largely unexplored.

In addition to its well-established role in directing the patterning of embryonic tissues,9 the Hedgehog (Hh) pathway has been implicated in the maintenance of stem or progenitor cell number in a growing list of adult tissues.10–15 Mature tissue homeostasis at these sites appears to be a consequence of Hh-mediated stem or progenitor cell self-renewal within the organ-specific stem cell niche. In addition to this observed role in “baseline” states, more recent work suggests that the Hh pathway also plays a critical role in regenerative responses to tissue injury. For example, Hh pathway activity is required for androgen-triggered regeneration of prostate epithelium in male mouse castrates,14 as well as in the course of pulmonary epithelial regeneration in a napthalene-induced model of acute pulmonary injury.15 Based on observations that inhibition of Hh signaling is associated with diminished tissue repair, these studies have suggested that up-regulated Hh signaling is a prerequisite for the stem/progenitor cell expansion that occurs in response to injury.

The aim of the current study was to determine the role of Hh signaling in the process of exocrine regeneration following cerulein-induced pancreatitis. Recent empiric studies in archived human specimens of chronic pancreatitis have demonstrated aberrant expression of Hh components,16,17 but these studies have not explored the functional implications of Hh blockade in the setting of exocrine injury. Confirming previous observations, we demonstrate by using lineage tracing experiments that pancreatic regeneration is mediated by mature acinar cells through the formation of transient metaplastic epithelium, expressing markers of pancreatic progenitor cells (nestin, Pdx1). Furthermore, exocrine injury and regeneration is characterized by early and profound up-regulation of Hh components. Importantly, we find that either pharmacologic or genetic interruption of the Hh pathway leads to impaired regeneration of the injured exocrine compartment, reinforcing a critical role for this pathway in pancreatic epithelial repair. Unexpectedly, we demonstrate that blockade of Hh signaling has minimal impact on the ability of acinar cells to generate metaplastic intermediates in response to injury; rather, absence of Hh signaling leads to a “redifferentiation arrest,” in which the metaplastic intermediates continue to express markers of pancreatic progenitor cells, and fail to reactivate an exocrine differentiation program. These findings demonstrate a unique role for the Hh-signaling pathway in the regulation of facultative pancreatic progenitor cells and suggest that, in addition to the established influence of Hh signaling on dedicated progenitor cell number, this pathway may also have novel tissue-specific effects on facultative progenitor cell function.

Materials and Methods

Induction of Experimental Pancreatitis

Either C57BL/6J wild-type mice (Charles River Laboratory, Wilmington, MA) or heterozygous Ptch1-LacZ reporter mice18 were used for cerulein injection, with or without concurrent cyclopamine treatment. To genetically abrogate the Hh pathway, 2 different Cre drivers were used for pancreas-specific depletion of Smoothened (Smo), a prerequisite for Hh signal transduction. First, Pdx1-Cre/Smoflox/flox mice were created by crossing Pdx1-Cre mice19 with C57BL/6J Smoflox/flox mice.11 Pdx1-Cre/Smo+/flox offspring were then backcrossed with Smoflox/flox mice to generate Pdx1-Cre/Smoflox/flox mice. Similarly, tamoxifen-inducible elastase (Ela)-Cre-ERT2 mice20 were used for generating Ela-Cre-ERT2/Smoflox/flox mice; administration of tamoxifen results in Cre activation under Elastase1 regulatory elements, leading to recombination in the mature exocrine (acinar) compartment. Heterozygous Pdx1-Cre/Smoflox/+ and Ela-CreERT2/Smoflox/+ were used as controls. Exocrine injury was induced by 8 daytime doses (50 μg/kg, intraperitoneally) of cerulein (MP Biomedicals, Aurora, OH) in 0.2 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 1 hour apart over 2 consecutive days. The final day of cerulein injection was defined as d0. Each experimental group contained 5 PBS-injected control mice and 15 transgenic mice (15 Ptch1-lacZ reporter mice, 15 tamoxifen induced Ela-CreERT2/Smoflox/flox mice, and 15 Pdx1-Cre/Smoflox/flox mice, respectively) receiving cerulein. Age-matched transgenic mice were used as control. Please refer to Supplementary Methods for additional details on tamoxifen induction and optimization of cyclopamine dosing in vivo (see Supplementary Methods online at www.gastrojournal.org).

Immunolabeling and Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

For immunolabeling, tissues were stained as previously described.21 Concentrations and source of primary antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table 1 (see Supplementary Table 1 online at www.gastrojournal.org). Fluorescence confocal microscopy was performed with a confocal laser scanning microscope (410LSM, Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) using 40× (NA 1.2) C-apochromat or 100× (NA 1.4) objectives. Quantification of injury severity was assessed by quantifying immunofluorescence image intensity profiles across replicate 2-dimensional (2D) optical sections following staining for amylase and DAPI. Tissue from Ptch1-LacZ reporter mice was processed for X-gal staining as described.11 One-step multiplex Taq-Man real-time PCR was performed using an ABI 7700 Sequence Detector System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Expression of Shh, Ihh, Ptch, Gli1, Smo, and was evaluated with PGK as internal control. Relative gene expression was determined based on corresponding threshold cycle (Ct) values, as previously described.22 Levels in treated mice (cerulein alone or cerulein + cyclopamine) were presented as a ratio to levels detected in untreated mice. The data reported represent means ± SE from multiple determinations obtained from 3 or more separate experiments. Statistical significance was assumed for P < .05.

Results

Exocrine Pancreatic Injury Is Associated With Proliferative Regeneration and Expansion of Nestin-Expressing Epithelial Population

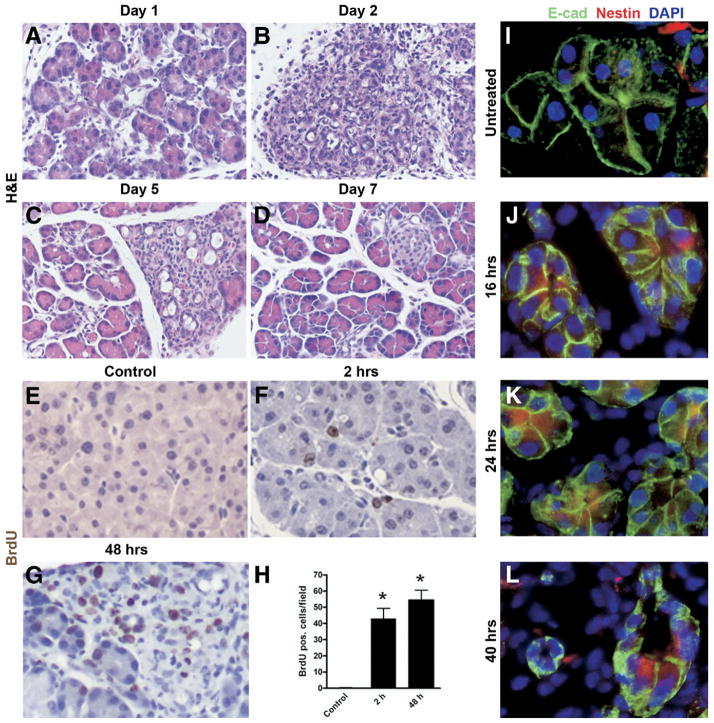

After a 2-day protocol of cerulein injections as previously described,4 all treated animals developed severe exocrine pancreatic injury, with near complete loss of acinar cells on day 2 following cerulein injection and near complete recovery by day 7 (Figure 1A–D). As previously described, the process of regeneration involved the transient expansion of metaplastic epithelium, followed by restoration of acinar cell mass. Although transient, this metaplastic epithelium appears similar to what has been previously described as type 1 tubular complexes (TC1) when observed in the setting of chronic pancreatitis.8 Lineage tracing and morphometric studies with “tagging” of acinar cells in Ela-CerERT;Z/AP mice are detailed in Supplementary Figures 1 and 2, respectively (see Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 online at www.gastrojournal.org). The acinar derivation of the transient metaplastic epithelium was confirmed by the lineage tracing studies. Regenerating epithelium was found to be highly proliferative, with a greater than 50-fold increase in rate of BrdU incorporation observed on day 2 following cerulein injection (Figure 1E–H). To clarify further the nature of this proliferating epithelium, we performed immunofluorescent staining for nestin, an intermediate filament known to be expressed in exocrine progenitor cells in developing mouse pancreas, as well as following acinar cell dedifferentiation in vitro.6,21 We observed early and widespread up-regulation of nestin in E-cadherin-expressing epithelial cell compartment following cerulein injury, including within metaplastic ductal lesions (Figure 1J–L). In contrast, nestin expression in uninjured pancreas was restricted exclusively to E-cadherin-negative mesenchymal elements (Figure 1I), as described.21

Figure 1.

Cerulein-induced exocrine pancreatic injury is characterized by proliferative regeneration and expansion of nestin-expressing cells. Panels A–D: Histologic progression of cerulein-induced pancreatic epithelial injury and regeneration. Images represent representative H&E-stained sections of mouse pancreatic tissue harvested on indicated day following final injection of cerulein. The peak of exocrine injury is observed at around day 2 (panel B), with gradual abatement and onset of regeneration by day 5 (panel C), and near complete restitution by day 7 (panel D). Panels E–H: Exocrine regeneration is accompanied by robust proliferation assessed by BrDU incorporation. Compared with control pancreata, over 50-fold higher BrDU incorporation is observed at day 2 in the exocrine compartment (panel H). Panels I–L: Expansion of nestin-expressing, E-cadherin-positive epithelial cells following cerulein-mediated injury. In untreated pancreas (I), nestin expression is confined to occasional E-cadherin-negative mesenchymal cells. By 16 hours (J), multiple E-cadherin-positive cells (red) stain for nestin (green), consistent with nestin up-regulation in the residual epithelial compartment. Nestin expression is observed in the metaplastic ductal intermediates seen at 40 hours (L).

Hh Pathway Is Activated During Acute Exocrine Pancreatic Injury and Regeneration

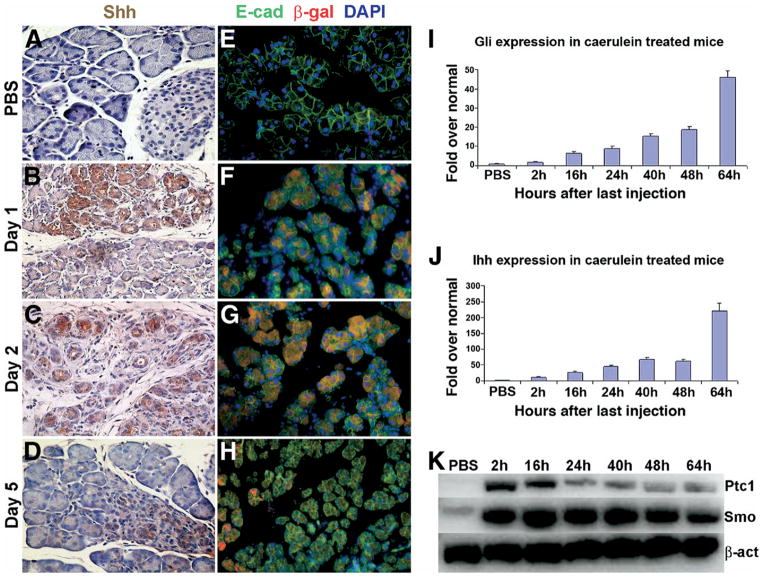

Immunohistochemical staining for Shh revealed no detectable expression in the ductal, acinar, or islet compartments of uninjured pancreas (Figure 2A). In contrast, Shh was widely expressed following cerulein-induced injury, with expression noted in residual acinar cells as well as in regenerating metaplastic epithelium. Enhanced expression of Shh began as early as day 1 postinjection, was persistent at day 2, but abated significantly by day 5 (Figure 2B–D). In concert with completed regeneration of the exocrine pancreas, no Shh expression was observed at day 7, similar to the lack of Shh expression observed in control mice (data not shown). Cerulein-administration in heterozygous Ptch1-LacZ reporter mice also permitted us to monitor the spatiotemporal distribution of cells responding to up-regulated Shh ligand. In control mice, immunofluorescent staining for β-galactosidase activity confirmed absence of detectable expression in the E-cadherin-expressing epithelial compartment (Figure 2E). In contrast, marked β-galactosidase expression was identified in regenerating exocrine pancreas, paralleling the course of cerulein injury and recovery during days 2 through 5 (Figure 2F–H). Additional characterization of Hh pathway activity following cerulein injury was performed using semiquantitative as well as quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis to assess expression of Hh ligand (Ihh), Hh receptor (Smo), and Hh-regulated genes (Ptch1 and Gli1) because reliable antibodies for these components are not readily available. These studies confirmed up-regulation of multiple Hh pathway components in the course of pancreatic injury and regeneration (Figure 2I–K).

Figure 2.

Cerulein-induced exocrine pancreatic injury is characterized by transient activation of the Hh-signaling pathway. Panels A–D: Immunohistochemical staining demonstrates injury-associated up-regulation of Shh expression with subsequent down-regulation following regeneration. Panels E–H: Temporal evolution of Hh pathway activation during cerulein-mediated injury and regeneration, as assessed by X-gal staining of pancreatic tissue harvested from Ptc-lacZ reporter mice. No exocrine expression of Shh ligand or evidence of Hh pathway activation is seen in PBS-treated pancreata (panels A and E). Shh ligand expression and Hh pathway activation are observed at days 1 and 2 (panels B and C and F and G, respectively), with abatement by day 5 (panels D and H, respectively). Panels I and J: Quantitative real-time PCR on RNA obtained from cerulein-treated mice demonstrates profound up-regulation of the Hh transcriptional target Gli1 (panel I), as well as a second Hh ligand, Indian Hh (panel J), in the injured pancreata. When normalized to the corresponding transcript levels in PBS-treated mouse pancreata, up-regulation of Hh pathway components begins as early as 2 hours, reaching peak levels between 48 and 64 hours following final cerulein injection. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean for each measurement. X-axis: hours after last cerulein injection; y-axis: relative fold expression normalized to PBS-treated mice. Panel K: Semiquantitative RT-PCR assay confirms similar up-regulation expression of Smo and Ptch1 within 2 hours following final dose of cerulein (time of harvest after last cerulein injection is indicated above each lane; β-actin is used as loading control).

Cyclopamine Abrogates Cerulein-Induced Up-Regulation of Hh Signaling

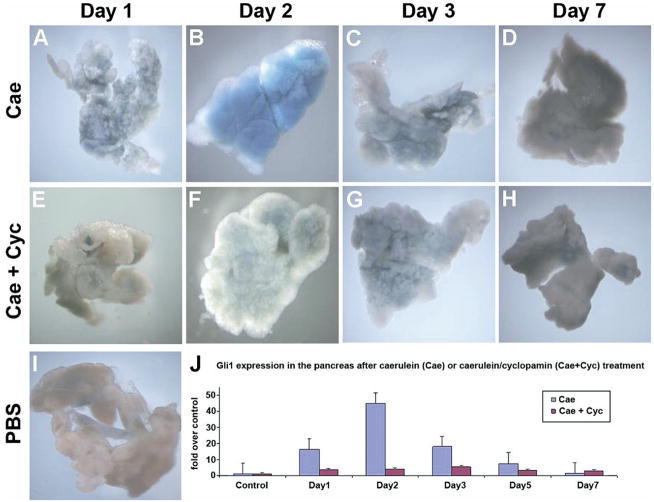

Given the transcriptional and immunohistochemical evidence suggesting widespread activation of Hh signaling following pancreatic exocrine injury (Figure 2), we next explored the effects of perturbation of this pathway in the setting of injury. Cyclopamine, a steroidal alkaloid, inhibits Hh signaling through direct interaction with smoothened.23 Cerulein treatment of adult Ptch1-LacZ reporter mice leads to dramatic, transient up-regulation of Hh signaling on day 2, which returns to baseline by day 7 (Figure 3A–D). In contrast, no up-regulation is observed in mice treated concurrently with cerulein and cyclopamine (Figure 3E–H). Quantitative real-time PCR for the Hh target Gli1 demonstrated significant up-regulation in mice treated with cerulein only, whereas, in cerulein plus cyclopamine treated mice, this up-regulation was minimal (Figure 3J). Real-time PCR for another Hh target gene, Ptch, mirrored the pattern observed with Gli1 (see Supplementary Figure 3A online at www.gastrojournal.org). In contrast, whereas expression of Hh ligand transcripts (Shh and Ihh) was up-regulated in response to cerulein injury at day 2, cyclopamine failed to abate ligand transcript levels, consistent with the actions of this small molecule inhibitor at the level of smoothened (see Supplementary Figure 3B and C online at www.gastrojournal.org). These experiments confirmed our ability to achieve effective pharmacologic blockade of Hh signaling during pancreatic injury in vivo.

Figure 3.

Cyclopamine abrogates cerulein-induced up-regulation of the Hh-signaling pathway. Ptc1-LacZ reporter mice were treated with cerulein alone (Cae) or with cerulein plus cyclopamine (Cae + Cyc), and histochemical staining for β-galactosidase was performed on whole mounts of harvested pancreata. Widespread but transient up-regulation of β-galactosidase is seen in cerulein-treated mice (panels A–D), consistent with activation of the Hh-signaling pathway. β-galactosidase over expression begins on day 1 (panel A), peaks at day 2 (panel B), and is progressively down-regulated on days 3 and 7 (panels C and D), coinciding with exocrine regeneration. In contrast, pancreatic tissue from mice receiving cerulein plus cyclopamine (panels E–H) shows minimal activation of β-galactosidase activity compared with baseline expression observed in PBS-treated mice (panel I). Further documentation of the diminished Hh response associated with cyclopamine treatment was obtained using quantitative real-time PCR for Gli1 transcripts (panel J), using pancreata harvested after cerulein treatment alone (Cae, blue bars) or cerulein plus cyclopamine treatment (Cae + Cyc, brown bars). X-axis indicates day following final cerulein injection, and y-axis indicates relative fold expression of Gli1 compared with PBS-treated control mice. Values represent mean ± SEM.

Pharmacologic Blockade of Hh Signaling Impairs Epithelial Regeneration Following Cerulein-Mediated Pancreatic Injury

We compared pancreatic tissue from mice treated with cerulein only versus mice treated with cerulein and cyclopamine to determine whether blockade of Hh signals affects the severity of injury, the effectiveness of regeneration, or both. We detected no demonstrable differences in the extent of exocrine injury in the cyclopamine-treated and untreated groups, as assessed on day 2 (see and compare Supplementary Figure 4A with Figure 1B online at www.gastrojournal.org). In contrast, there was significant impairment of pancreatic regeneration in cyclopamine-treated mice, with a marked reduction of differentiated acinar cells persisting even at day 7 (see Supplementary Figure 4Conline at www.gastrojournal.org), a time point at which Hh-competent pancreatic tissue demonstrated near complete regeneration. To confirm further that day 7 phenotype caused by cyclopamine pretreatment was due to impaired regeneration, rather than more severe initial injury, we quantified cross-sectional areas of amylase expression in cerulein-treated versus cerulein plus cyclopamine-treated mice (see Supplementary Figure 4D–G online at www.gastrojournal.org). Using confocal microscopy, we compared the expression of DAPI and amylase on days 2 and 7 in cerulein-injured pancreatic tissue from mice treated with and without cyclopamine and generated fluorescence intensity profiles across replicate 2D optical sections. We found no quantitative difference between cerulein versus cerulein plus cyclopamine-treated mice in the loss of amylase expression on day 2 (see Figure 5M) but did observe a dramatic difference in amylase expression on day 7, reflecting impaired regeneration in the setting of Hh pathway inhibition (see Supplementary Figure 4D–G online at www.gastrojournal.org, and see Figure 5N).

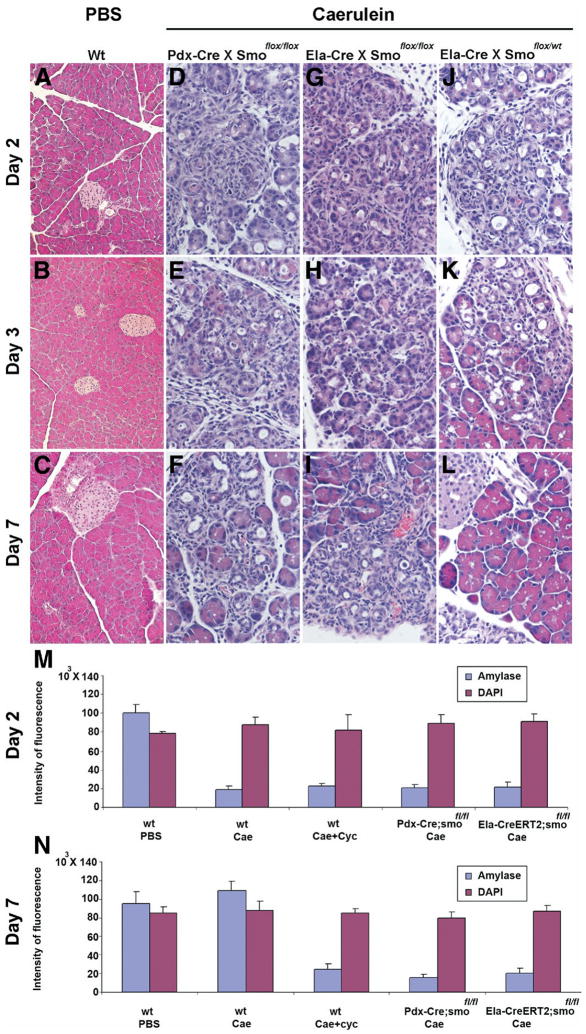

Figure 5.

Genetic interruption of Hh signaling results in impaired tissue regeneration following cerulein injury. Panels A–L: Representative H&E-stained sections of mouse pancreas on days 2, 3, and 7 following injection of either PBS or cerulein. Pancreatic tissue was harvested from either wild-type (Wt) (panels A–C), Pdx1-Cre; Smoothenedfl/fl (panels D–F), Elastase1-CreERT2;Smoothenedfl/fl (panels G–I), or Elastase1-CreERT2;Smoothenedfl/wt (panels J–L) mice. In panels A–C, PBS-treated wild-type mice demonstrate no tissue response. Analogously, tamoxifen-induced Ela-CreERT2;Smoothenedlox/wt heterozygous mice (panels J–L), which retain Smoothened function, demonstrate a tissue regeneration response that is identical to wild-type mice treated with cerulein (see Figure 1), with a peak of injury on day 2, and near complete regeneration by day 7. In contrast, interruption of Hh signaling either throughout the epithelial compartment (Pdx1-Cre;Smoothenedfl/fl mice), or exclusively in acinar cells (Elastase1-CreERT2;Smoothenedfl/fl mice), resulted in an impaired regenerative response identical to that observed following cyclopamine treatment. Panels M and N: Quantification of initial injury and subsequent regeneration, using 2D fluorescent intensity profiles as demonstrated in Supplementary Figure 3 (see Supplementary Figure 3 online at www.gastrojournal.org. (M) Similar reductions in amylase staining are observed in each group on day 2, indicating similar severity of initial cerulein-mediated injury in each group. (N) Failure to regenerate amylase-expressing cells on day 7 in the setting of either pharmacologic or genetic blockade of Hh signaling. Either systemic blockade of Hh signaling by cyclopamine or deletion of Smoothened either throughout pancreatic epithelium or specifically in acinar cells results in failure to regenerate exocrine cell mass.

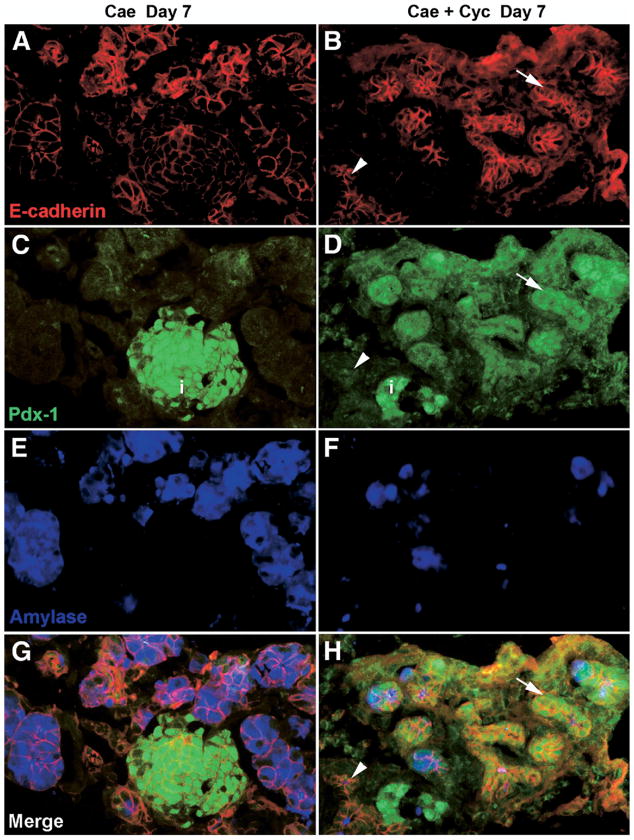

The impaired exocrine regeneration was accompanied by abnormal persistence of extraislet Pdx1-expression,6,24 implying the ongoing presence of metaplastic epithelium with a progenitor-like phenotype, even at day 7 postcerulein injury (Figure 4). As previously reported,4 the Pdx1-expressing metaplastic lesions were amylase negative and E-cadherin positive, confirming their epithelial nature; their acinar derivation was suggested by the occasional presence of amylase, E-cadherin, and Pdx1 coexpressing acinar structures within the field of injury. These data suggest that, whereas Hh signaling does not influence the initial severity of injury, and is not required for the formation of metaplastic lesions, Hh pathway activity is required for subsequent “redifferentiation” events required for effective regeneration of acinar cell mass.

Figure 4.

Persistence of extraislet Pdx1 expressing metaplastic intermediates in cerulein pancreatitis in the setting of pharmacologic blockade of Hh signaling at day 7 postcerulein injury. Pdx1 expression in the pancreata of mice with retained Hh activity is restricted to the islet cells. In contrast, in the setting of Hh blockade (Cae + Cyc), persistent metaplastic intermediates (E-cadherin positive, amylase negative) are seen that label with nuclear Pdx1 (green channel). Acinar derivation of the metaplastic intermediates is suggested by the occasional presence of amylase, E-cadherin, and Pdx1 coexpressing acinar structures within the field of injury. Specificity of Pdx1 labeling in the epithelial compartment is confirmed by the presence of both Pdx1-expressing (arrow) and Pdx1-negative (arrowhead) structures within the same field.

Genetic Abrogation of Hh Signaling in the Exocrine Pancreas Is Also Associated With Impaired Regeneration

To confirm that the impaired regeneration induced by cyclopamine was Hh-specific, and also to determine the specific cell type in which Hh signaling was required, we pursued 2 additional genetic strategies for Hh pathway inhibition. Both strategies were based on the established finding that smoothened is the key signal transducer for Hh and, therefore, that loss of smoothened function results in abrogation of Hh activity.23 Using Cre driver mice to ablate a floxed smoothened allele either throughout the entire pancreatic epithelium (Pdx1-Cre) or specifically in adult acinar cells (Ela-CreERT2), we evaluated the effect of genetic interruption of Hh signaling on pancreatic regeneration following cerulein injury. In the Pdx1-Cre;Smoflox/flox mice, Cre-mediated loss of Smoothened occurs through the developing pancreatic epithelium such that multiple epithelial lineages (acinar, ductal, and islet) are deficient in Hh signaling. Unexpectedly, the pancreata of Pdx1-Cre;Smoflox/flox mice were unremarkable at birth and remained so in young adult mice throughout the duration of study (6–8 weeks; data not shown), implying that epithelial cell-specific loss of Hh signaling may be dispensable for normal pancreatic development. In fact, the only discernible phenotype in these pancreata was revealed following cerulein injury, as described below. Similarly, the pancreata of tamoxifen-induced Ela-CreERT2;Smoflox/flox mice were unremarkable in the absence of cerulein-mediated injury. In contrast, mice undergoing either multilineage or acinar cell-specific Cre-mediated deletion of smoothened demonstrated an impaired regenerative response to exocrine injury, identical to that observed following treatment with cyclopamine (Figure 5D–F and 5G–I). As a comparison, Ela-CreERT2;Smoflox/wt mice, which retain a functional smoothened allele, demonstrated a tissue regeneration response identical to wild-type cerulein-treated mice, with the peak of injury on day 2 and a return to baseline by day 7 (Figure 5J–L). These morphologic observations were borne out by quantitative image analysis (Figure 5M and N), wherein comparable loss of amylase expression was observed at day 2 in all 4 treatment groups (cerulein only, cerulein plus cyclopamine, cerulein on a Pdx1-Cre; Smoflox/flox background, and cerulein on a tamoxifen-induced Ela-CreERT2;Smoflox/flox background), confirming no differences in the intensity of initial injury. In contrast, by day 7, exocrine regeneration returned to baseline levels in the cerulein-treated wild-type mice, whereas the mice with either pharmacologic or genetic abrogation of Hh signaling continued to demonstrate a profound loss of differentiated exocrine cells.

Discussion

Similar to prior reports,5,8 our study suggests that differentiated Elastase-expressing cells are a source of regenerating pancreatic epithelium in adult mouse pancreas and further demonstrate that an intact Hh pathway is required for these cells to effectively regenerate acinar cell mass. In contrast to other tissues in which Hh is felt to be responsible for establishing progenitor identity and regulating progenitor cell numbers,10,11,18,25,26 the role of Hh signaling following cerulein-mediated injury appears to be limited to regulation of progenitor cell function, specifically the ability of dedifferentiated acinar cells to contribute to tissue renewal. This role is exemplified by the fact that, even in the face of either pharmacologic or genetic Hh blockade, acinar cells remain fully able to proliferate in response to injury (see Supplementary Figure 5 online at www.gastrojournal.org). However, in the absence of Hh signaling, these metaplastic intermediates, which express markers of pancreatic progenitor cells, exhibit an inability to redifferentiate, impairing the process of tissue repair. Although these data suggest that differentiated exocrine cells represent the primary source of regenerating exocrine epithelium following cerulein injury, they certainly do not exclude the presence of a dedicated progenitor pool that might be activated by other forms of injury.

The ability of differentiated cell types to act as effective progenitor cells has been well established in a variety of settings, including liver and β-cell regeneration in mammals1,3 and tail, limb, and corneal regeneration in amphibians.27–29 In many of these settings, differentiated cell types undergo at least some component of dedifferentiation and cell cycle reentry, followed by proliferative expansion of resulting progenitor cells and subsequent regeneration of differentiated cell types. In this manner, differentiated cells act as “facultative” or “situational” progenitors. The role of Hh signaling in modulating the dedifferentiation, proliferation, and redifferentiation of facultative progenitors has been studied in detail in the context of amphibian tail regeneration.27 Following tail amputation in axolotl salamanders, skin and muscle cells adjacent to the point of amputation undergo dedifferentiation to generate a wound blastema. Dedifferentiated blastema cells subsequently proliferate and then redifferentiate to form cartilage, muscle, and dermis. During this process, blastema cells display evidence of Hh pathway activation as assessed by Patched1 expression. When this Hh signal is blocked by cyclopamine, dedifferentiated blastema cells are able to form but exhibit reduced proliferation and fail to redifferentiate into muscle or cartilage.28 Similarly, studies of newt lens regeneration, in which adjacent pigmented epithelial cells dedifferentiate and proliferate to form a new lens vesicle, suggest that Hh is required for both the proliferation of dedifferentiated progenitors and their subsequent redifferentiation to form lens fibers.29

In contrast, the current results suggest that in mammalian pancreas, Hh signaling may play a more limited role in regulating progenitor-like cells, with a dominant effect on “redifferentiation” of metaplastic intermediates that arise from acini. This limited influence may reflect reliance on other signaling pathways known to mediate acinar cell dedifferentiation and proliferation, including the epidermal growth factor and Notch pathways. The epidermal growth factor receptor ligand transforming growth factor α is up-regulated following various forms of pancreatic injury, including cerulein-mediated pancreatitis,30,31 and previous studies have demonstrated the ability of transforming growth factor α to induce acinar cell dedifferentiation and generation of nestin-expressing progenitor cells.6,24 Notch pathway activation is capable of inducing similar dedifferentiation events and appears to mediate the effects of epidermal growth factor signaling during acinar cell dedifferentiation.32 Given the previously reported activation of Notch signaling following cerulein-mediated pancreatic injury,4 this epidermal growth factor-Notch axis would appear to play a dominant role in the initial response to pancreatic epithelial injury.

Of note, we did not detect any contribution of acinar cell-derived progenitor cells to islet or ductal lineages (see Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 online at www.gastrojournal.org). Although this may reflect the fact that islet and ductal elements are largely unaffected by cerulein administration, additional studies involving direct islet injury have similarly failed to identify in vivo “transdifferentiation” of acinar cells to nonacinar cell fates,5 contrasting with results reported when acinar cells are cultured in vitro.33 In conjunction with recent studies by Strobel et al confirming the lack of transdifferentiation of mature islet cells into acinar lineages in vivo,8 one can postulate that “transdifferentiation promiscuity” of mature compartments in the pancreas is, for the part, fairly limited. In other words, while one cannot exclude transdifferentiation events from certain kinds of injury, at least in the setting of cerulein pancreatitis, “acini beget acini.” In the current study, genetic labeling of acinar cells confirmed their dedifferentiation to generate transient metaplastic epithelium but failed to demonstrate any contribution to mature ductal epithelium. Many studies, including our own,34 have previously referred to this process of acinar cell dedifferentiation as “acinar-to-ductal metaplasia,”35 reflecting the fact that metaplastic epithelium exhibits a duct-like cross-sectional morphology, and often stains positive for cytokeratins typically expressed in ductal epithelium. However, this metaplastic epithelium also exhibits expression of other genes not normally expressed in pancreatic ductal epithelium, including Pdx1 and Hes1, reflecting the dedifferentiated nature of these cells.24,32 In the current study, we have therefore avoided the term “acinar-to-ductal metaplasia” and favor the simple term “transient metaplastic intermediates” to refer to the transient lesions generated following cerulein injury.

In addition to providing new information regarding the biology of acinar cell-derived progenitor cells, the current study also provides potential insight regarding mechanisms of pancreatic tumorigenesis. Prior studies have demonstrated that Hh pathway activation represents a characteristic feature of pancreatic cancer.13,36,37 In addition to being required for exocrine pancreatic cancer growth, Hh signaling seems to promote a non-pancreatic gastrointestinal pattern of cellular differentiation.22 Additional recent studies have demonstrated that forced Hh pathway activation in adult pancreas induces the formation of undifferentiated pancreatic carcinoma and that Hh also cooperates with oncogenic KRAS to induce pancreatic cancer precursors.38 Based on the fact that patients with chronic pancreatitis carry a 16-fold increased risk for pancreatic cancer,39 our observation of profound Hh activation following exocrine pancreatic injury may provide a mechanistic link between chronic pancreatic injury and subsequent neoplasia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants CA113669 and DK072532 and the Sol Goldman Pancreatic Cancer Research Center (to A.M.); NIH grants DK61215 and DK56211 and the Paul Neumann Professorship in Pancreatic Cancer Research (to S.D.L.); a fellowship grant within the Postdoctoral Program of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD; to G.F.); the Barbara S. Goodman Pancreatic Cancer Career Development Award of the Israel Cancer Research Fund (to Y.D.); and, for mouse husbandry costs, by funds from a Mouse Models of Human Cancer Consortium grant to Robert J. Coffey at Vanderbilt University (U01CA084239).

The authors thank Charles Murtaugh and Ariel Ruiz i Altaba for helpful discussions.

Abbreviation used in this paper

- Hh

Hedgehog

Footnotes

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.011.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no competing financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Alison MR, Poulsom R, Forbes SJ. Update on hepatic stem cells. Liver. 2001;21:367–373. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2001.210601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blau HM, Brazelton TR, Weimann JM. The evolving concept of a stem cell: entity or function? Cell. 2001;105:829–841. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00409-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dor Y, Brown J, Martinez OI, et al. Adult pancreatic β-cells are formed by self-duplication rather than stem-cell differentiation. Nature. 2004;429:41–46. doi: 10.1038/nature02520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jensen JN, Cameron E, Garay MV, et al. Recapitulation of elements of embryonic development in adult mouse pancreatic regeneration. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:728–741. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desai BM, Oliver-Krasinski J, De Leon DD, et al. Preexisting pancreatic acinar cells contribute to acinar cell, but not islet β-cell, regeneration. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:971–977. doi: 10.1172/JCI29988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Means AL, Meszoely IM, Suzuki K, et al. Pancreatic epithelial plasticity mediated by acinar cell transdifferentiation and generation of nestin-positive intermediates. Development. 2005;132:3767–3776. doi: 10.1242/dev.01925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adler G, Hupp T, Kern HF. Course and spontaneous regression of acute pancreatitis in the rat. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1979;382:31–47. doi: 10.1007/BF01102739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strobel O, Dor Y, Stirman A, et al. Beta cell transdifferentiation does not contribute to preneoplastic/metaplastic ductal lesions of the pancreas by genetic lineage tracing in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4419–4424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605248104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Apelqvist A, Ahlgren U, Edlund H. Sonic Hedgehog directs specialised mesoderm differentiation in the intestine and pancreas. Curr Biol. 1997;7:801–804. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00340-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Kalderon D. Hedgehog acts as a somatic stem cell factor in the Drosophila ovary. Nature. 2001;410:599–604. doi: 10.1038/35069099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machold R, Hayashi S, Rutlin M, et al. Sonic hedgehog is required for progenitor cell maintenance in telencephalic stem cell niches. Neuron. 2003;39:937–950. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00561-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beachy PA, Karhadkar SS, Berman DM. Tissue repair and stem cell renewal in carcinogenesis. Nature. 2004;432:324–331. doi: 10.1038/nature03100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berman DM, Karhadkar SS, Maitra A, et al. Widespread requirement for Hedgehog ligand stimulation in growth of digestive tract tumours. Nature. 2003;425:846–851. doi: 10.1038/nature01972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karhadkar SS, Bova GS, Abdallah N, et al. Hedgehog signalling in prostate regeneration, neoplasia and metastasis. Nature. 2004;431:707–712. doi: 10.1038/nature02962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watkins DN, Berman DM, Burkholder SG, et al. Hedgehog signalling within airway epithelial progenitors and in small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2003;422:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature01493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kayed H, Kleeff J, Keleg S, et al. Distribution of Indian Hedgehog and its receptors patched and smoothened in human chronic pancreatitis. J Endocrinol. 2003;178:467–478. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1780467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakashima H, Nakamura M, Yamaguchi H, et al. Nuclear factor-κB contributes to Hedgehog signaling pathway activation through sonic Hedgehog induction in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7041–7049. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodrich LV, Milenkovic L, Higgins KM, et al. Altered neural cell fates and medulloblastoma in mouse patched mutants. Science. 1997;277:1109–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hingorani SR, Petricoin EF, Maitra A, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:437–450. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanger BZ, Stiles B, Lauwers GY, et al. Pten constrains centroacinar cell expansion and malignant transformation in the pancreas. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esni F, Stoffers DA, Takeuchi T, et al. Origin of exocrine pancreatic cells from nestin-positive precursors in developing mouse pancreas. Mech Dev. 2004;121:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prasad NB, Biankin AV, Fukushima N, et al. Gene expression profiles in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia reflect the effects of Hedgehog signaling on pancreatic ductal epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1619–1626. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen JK, Taipale J, Cooper MK, et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling by direct binding of cyclopamine to Smoothened. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2743–2748. doi: 10.1101/gad.1025302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song SY, Gannon M, Washington MK, et al. Expansion of Pdx1-expressing pancreatic epithelium and islet neogenesis in transgenic mice overexpressing transforming growth factor α. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1416–1426. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70292-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramalho-Santos M, Melton DA, McMahon AP. Hedgehog signals regulate multiple aspects of gastrointestinal development. Development. 2000;127:2763–2772. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.12.2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forbes AJ, Lin H, Ingham PW, et al. Hedgehog is required for the proliferation and specification of ovarian somatic cells prior to egg chamber formation in Drosophila. Development. 1996;122:1125–1135. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.4.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Echeverri K, Tanaka EM. Ectoderm to mesoderm lineage switching during axolotl tail regeneration. Science. 2002;298:1993–1996. doi: 10.1126/science.1077804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schnapp E, Kragl M, Rubin L, et al. Hedgehog signaling controls dorsoventral patterning, blastema cell proliferation and cartilage induction during axolotl tail regeneration. Development. 2005;132:3243–3253. doi: 10.1242/dev.01906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsonis PA, Vergara MN, Spence JR, et al. A novel role of the Hedgehog pathway in lens regeneration. Dev Biol. 2004;267:450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang RN, Rehfeld JF, Nielsen FC, et al. Expression of gastrin and transforming growth factor-α during duct to islet cell differentiation in the pancreas of duct-ligated adult rats. Diabetologia. 1997;40:887–893. doi: 10.1007/s001250050764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menke A, Yamaguchi H, Giehl K, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor and fibroblast growth factor 2 are overexpressed after cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1999;18:28–33. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyamoto Y, Maitra A, Ghosh B, et al. Notch mediates TGF-α-induced changes in epithelial differentiation during pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:565–576. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minami K, Okuno M, Miyawaki K, et al. Lineage tracing and characterization of insulin-secreting cells generated from adult pancreatic acinar cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15116–15121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507567102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crawford HC, Scoggins CR, Washington MK, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-7 is expressed by pancreatic cancer precursors and regulates acinar-to-ductal metaplasia in exocrine pancreas. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1437–1444. doi: 10.1172/JCI15051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hruban RH, Adsay NV, Albores-Saavedra J, et al. Pathology of genetically engineered mouse models of pancreatic exocrine cancer: consensus report and recommendations. Cancer Res. 2006;66:95–106. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thayer SP, di Magliano MP, Heiser PW, et al. Hedgehog is an early and late mediator of pancreatic cancer tumorigenesis. Nature. 2003;425:851–856. doi: 10.1038/nature02009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feldmann G, Dhara S, Fendrich V, et al. Blockade of Hedgehog signaling inhibits pancreatic cancer invasion and metastases: a new paradigm for combination therapy in solid cancers. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2187–2196. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morton JP, Mongeau ME, Klimstra DS, et al. Sonic Hedgehog acts at multiple stages during pancreatic tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5103–5108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701158104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P. Epidemiology and risk factors for pancreatic cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.