Abstract

It has been suggested that the motor system may circumvent the difficulty of controlling many degrees of freedom in the musculoskeletal apparatus by generating motor outputs through a combination of discrete muscle synergies. How a discretely organized motor system compensates for diverse perturbations has remained elusive. Here, we investigate whether motor responses observed after an inertial-load perturbation can be generated by altering the recruitment of synergies normally used for constructing unperturbed movements. Electromyographic (EMG, 13 muscles) data were collected from the bullfrog hindlimb during natural behaviors before, during, and after the same limb was loaded by a weight attached to the calf. Kinematic analysis reveals the absence of aftereffect on load removal, suggesting that load-related EMG changes were results of immediate motor pattern adjustments. We then extracted synergies from EMGs using the nonnegative matrix factorization algorithm and developed a procedure for assessing the extent of synergy sharing across different loading conditions. Most synergies extracted were found to be activated in all loaded and unloaded conditions. However, for certain synergies, the amplitude, duration, and/or onset time of their activation bursts were up- or down-modulated during loading. Behavioral parameterizations reveal that load-related modulation of synergy activations depended on the behavioral variety (e.g., kick direction and amplitude) and the movement phase performed. Our results suggest that muscle synergies are robust across different dynamic conditions and immediate motor adjustments can be accomplished by modulating synergy activations. An appendix describes the novel procedure we developed, useful for discovering shared and specific features from multiple data sets.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, there has been much enthusiasm in the movement control community in the idea that organizing the motor system into modules could be a way for the CNS to circumvent the difficulty of controlling the many degrees of freedom in the musculoskeletal apparatus (Bernstein 1967). As reviewed in Flash and Hochner (2005), a motor module, sometimes called a motor primitive (Bizzi et al. 1991), can be conceptualized at different levels of the motor system hierarchy: the behavioral, the kinematic, the muscular, down to the neural levels. At the muscular level, recent studies have provided evidence suggesting that a module can be represented as a muscle synergy, defined by various authors as a time-invariant activation profile across many muscles, activated by a time-varying activation coefficient (d'Avella and Bizzi 2005; Hart and Giszter 2004; Saltiel et al. 2001; Ting and Macpherson 2005; Torres-Oviedo and Ting 2007; Tresch et al. 1999, 2006). We and others have previously argued that a linear combination of a small number of synergies is responsible for the generation of muscle patterns underlying natural behaviors (Cappellini et al. 2006; Cheung et al. 2005; d'Avella 2000) and hypothesized that each synergy can be regarded as a low-level feedforward controller (d'Avella et al. 2006) producing joint torques that can be related to global biomechanical (Torres-Oviedo et al. 2006) or kinematic (Cajigas-González 2003; d'Avella et al. 2003) variables.

Whether a motor control scheme comprising a small number of functionally relevant synergies is compatible with the bewildering capacity of the motor system to compensate for diverse, and often unpredictable, perturbations over different timescales has remained an intriguing question. Although the intrinsic viscoelastic properties of the musculoskeletal apparatus likely contribute to instantaneous perturbation compensation (Bizzi et al. 1992), neural activations elicited by sensory afferents no doubt play a critical role in generating compensatory responses (reviewed in Rossignol et al. 2006). Muscle activations associated with immediate perturbation compensation can conceivably be generated by modulating the activation pattern of the very same set of synergies used for constructing normal behaviors. Alternatively, compensatory responses might result from built-in corrective muscle synergies, accessible by sensory afferents but not normally used for movement construction before perturbation, similar in concept to the corrective force-field primitives observed in the frog (Kargo and Giszter 2000). A third possibility is that corrective muscle patterns are generated solely by modulating the activations of individual muscles through segmental and long-loop reflex pathways rather than by modulating activations of preorganized muscle synergies. This possibility would imply that either the networks organizing the synergies are not susceptible to sensory influences (and thus any corrective pattern can result only from reflexive adjustments of individual muscles) or any sensory modulation of synergy activations plays no role in perturbation compensation. Finally, there remains a possibility that motor outputs are not constructed by any preorganized muscle synergies specified by distinct neuronal networks and thus any apparent “muscle synergy” is just the result of a muscle coactivation pattern assembled, under certain high-level control policies, by the motor system for a specific task performed under a specific dynamic environment. In this case, compensatory responses observed after perturbations would have to be either generated just by existing reflex pathways or coordinated in accordance with other control principles. It remains unclear as to which of the above possibilities can best explain the motor patterns elicited on limb perturbation for immediate corrective responses.

We have previously shown that many muscle synergies observed in frog locomotor behaviors persist even after deafferentation, suggesting that many synergies underlying natural motor behaviors might be centrally organized motor primitives (Cheung et al. 2005). More recently, d'Avella et al. (2006) demonstrated that in fast reaching movements of humans, muscle synergies observed in the electromyographic activities (EMGs) of an unloaded arm can explain a large fraction of the variation present in the EMGs collected from the same arm loaded by an endpoint weight. Both of these cited studies point to the possibility that synergies for natural motor behaviors are structures that are robust across different dynamic conditions. An even more recent study by Perreault et al. (2008) reports that in a human multijoint postural maintenance task, reflexive muscle activities for limb stabilization can be decomposed into several coordinative muscle profiles that remain the same across both stiff and compliant environments. This suggests that stabilizing EMGs for different perturbation types may be generated by sensory modulation of a set of fixed coordinative structures. Motivated by the above-cited studies, we here explicitly test the hypothesis that, during natural motor behaviors, compensatory muscle patterns observed on limb perturbations can be generated by modulating the activation pattern of the very same set of synergies underlying movements before perturbation. This hypothesis predicts that muscle synergies are structures that are robust across motor behaviors executed in different perturbation conditions and that EMG changes associated with limb perturbations can be explained as alterations in the recruitment profile of a set of invariant synergies. In light of our previous observation that the activation amplitude and duration of many frog synergies were altered specifically during limb flexion after deafferentation (Cheung et al. 2005), we expect that changes in the activations of the synergies after perturbation delivery would be the most pronounced during the flexion phases of the behaviors examined.

In our experiments, we tested the aforementioned hypothesis by perturbing the hindlimb of the frog during four natural behaviors, including kicking, jumping, stepping, and swimming. Electromyographic data from 13 hindlimb muscles of the perturbed limb were collected before, during, and after the frog limb was perturbed by an inertial load, delivered by a weight attached to the calf. To analyze the synergies of the different loading conditions, we developed a novel procedure based on the nonnegative matrix factorization method (Lee and Seung 1999), capable of simultaneously discovering synergies shared by all unloaded and loaded EMGs, as well as synergies specific to one or multiple loading conditions. To analyze the activation patterns of the synergies, we parameterized the kicking and jumping behaviors so that the synergy activations of unloaded and loaded episodes belonging to similar behavioral varieties were compared. Our results support that sensory modulation of the activations of centrally organized synergies, invariant across loading conditions, can be a mechanism underlying motor response adjustments for immediate load compensation during natural motor behaviors.

METHODS

Implantation of EMG electrodes

Before experimentation, all procedures were examined and approved by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Committee on Animal Care. Four adult bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana, ∼240–340 g), named P, Q, R, and S, were studied. Before surgery for electrode implantation, the frog was anesthetized with ice and with tricaine (ethyl 3-aminobenzoate methanesulfonate, 100 mg/kg; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) injected into the left iliac sac. Bipolar EMG electrodes were implanted into 13 right-hindlimb muscles (Cheung et al. 2005; d'Avella et al. 2003) falling into five functional groups (nomenclature: Ecker 1971):

) Group I: Hip extensors/knee flexors, including adductor magnus (AD), semimembranosus (SM), rectus internus major (RI), and semitendinosus (ST). While AD is a hip extensor, SM, RI, and ST are both hip extensors and knee flexors.

) Group II: Knee extensors/hip flexors, including vastus internus (VI), vastus externus (VE), and rectus femoris anticus (RA).

) Group III: Major flexors in the thigh, including iliopsoas (IP), biceps (or iliofibularis) (BI), and sartorius (SA). All three muscles are hip flexors; BI and SA also have knee flexor action.

) Group IV: Ankle flexors/knee extensors, including tibialis anticus (TA) and peroneus (PE).

) Group V: Ankle extensor/knee flexor, consisting of gastrocnemius (GA) only.

The EMG wires were routed subcutaneously to the frog's back and attached through crimped pins to a connector insulated by wax and epoxy. A custom-made plastic platform, adhering to the inner surface of the back skin through Nexaband glue (Veterinary Products Laboratories, Phoenix, AZ), stabilized the connector. The frog was allowed ≥1 day for recovery from surgery.

Experimental procedure

Patterns of EMG during unrestrained terrestrial behaviors (frogs P, Q, and R) including kicking (i.e., ballistic unilateral limb extension followed by flexion without body displacement), jumping, and stepping, as well as swimming behaviors (frog S), were acquired during four to five within-day experimental sessions spread over 5–8 days. In each session, two to eight trials of data collection, each lasting about 10 min, were performed. Between trials, the frog was rested for ≥15 min to prevent muscle fatigue and exhaustion. During the terrestrial trials, positions of the acetabulum, knee, and ankle on the dorsal limb surface were marked by Wite-Out correction fluid (Milford, CT) to facilitate kinematics extraction (see Recording kinematics in the following text). During the swimming trials, additional insulation of the connector against water was provided by removable light-bodied Permlastic (Kerr USA, Romulus, MI). All movements were videotaped by a digital videocamera (Sony DCR-HC46, 29.97 frames/s), although kinematics were extracted from the video only for kicks and jumps.

Effects of inertial loading on the EMGs were studied by attaching a weight to the frog's right calf. The weight (20.1–40.2 g), made of malleable lead, was adhered to a double-layer vinyl strap by Elastikon tape (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ). In the loaded trials, the weight was attached to the anterior (frogs Q, R, and S) or posterior half (frog P) of the right calf by wrapping the strap around the calf and securing the strap's position by industrial-strength Velcro. The load was positioned carefully so that it did not physically obstruct the motion of any joint.

To ensure that any EMG changes associated with loading were repeatable and reversible, in three frogs (Q, R, and S) the same load was applied and then taken off several times. In frogs Q and R, the same weight (frog Q, 63% of hindlimb weight; frog R, 56%) was applied three times, in sessions 2, 3, and 4, respectively, during terrestrial behaviors. In frog S, the weight (85%) was applied two times, in sessions 2 and 3, respectively, during aquatic behaviors. In each of these sessions, data were collected before, during, and after load application. For frog P only, two different loads were tried: a lighter load (37%) was applied first over sessions 2 and 3 and, then, a heavier load (74%) over sessions 4 and 5. The experimental schedules of the four frogs are summarized in Fig. 1A.

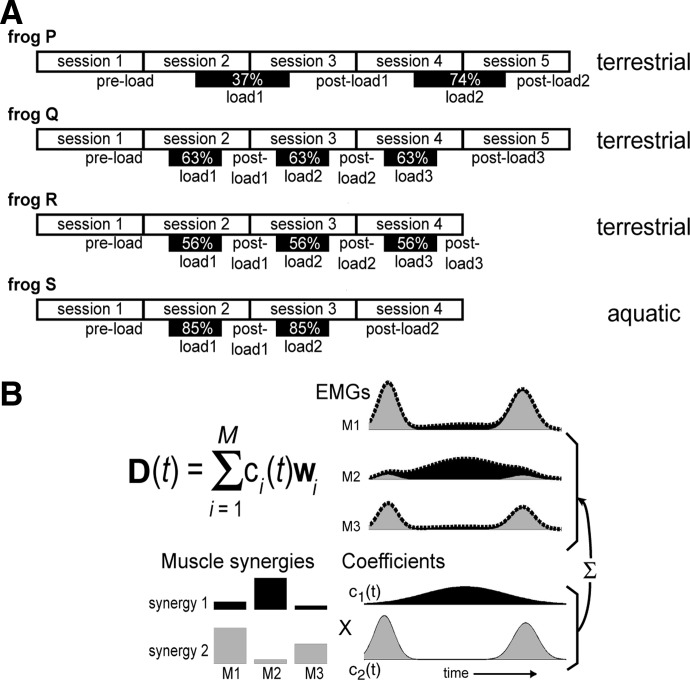

FIG. 1.

Experimental procedure and the muscle synergy model used in this study. A: the experimental schedules of the 4 frogs (P, Q, R, and S) studied herein. Electromyographic data of 13 muscles during terrestrial behaviors (kicking, jumping, and stepping) were collected from 3 frogs (P, Q, and R) and those during aquatic behaviors (in-phase and out-of-phase swimming), from one frog (S). In selected trials, an inertial load was applied to the frog hindlimb by attaching a weight to the frog's calf. The black boxes in the figure indicate the within-day sessions in which each frog was exposed to the load. The number in each box refers to the weight of the load applied, expressed as a percentage of the hindlimb's weight. Abbreviations: load1, the first block of loaded trials; load2, the second block of loaded trials; load3, the third block of loaded trials. B: the muscle synergy model. In this example, the waveforms of 3 muscles (M1, M2, and M3) are explained as a linear combination of 2 synergies (synergy 1 and synergy 2), each represented as a static activation balance profile across the 3 muscles, and activated by a time-varying activation coefficient. The model can be formally stated by the equation shown in the figure, where D(t) is the electromyographic (EMG) data of all muscles at time t, wi is the synergy vector for the ith synergy, ci(t) is the coefficient for the ith synergy at time t, and M is the total number of synergies composing the data set. For more details, see methods, Data analysis: the muscle synergy model.

After data collection, each frog was killed by an overdose injection of tricaine (800 mg/kg). Positions of the EMG electrodes were verified by dissection, after which the right hindlimb was detached from the body by sharp scissors and then weighed.

Recording kinematics and characterizing behavioral varieties

Kinematics of kicking (frogs P, Q, and R) and jumping (frog R) were extracted from the recorded video images. Video episodes were captured from mini-DV videotapes and digitized as avi files using Adobe Premiere 6.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). Each frame in the video files was deinterlaced into its upper and lower fields using a custom software written in Matlab (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). Positions of the body axis, acetabulum, knee, and ankle were marked manually onto individual video fields using a custom graphical user interface (GUI). Assuming a planar motion of the frog hindlimb, time sequences of the hip and knee joint angles (29.97 × 2 = 59.64 Hz) were computed from the marker positions extracted from the video fields. The hip angle is defined to be the angle between the body axis and the femur, and the knee angle, that between the femur and tibiofibula (Fig. 2A).

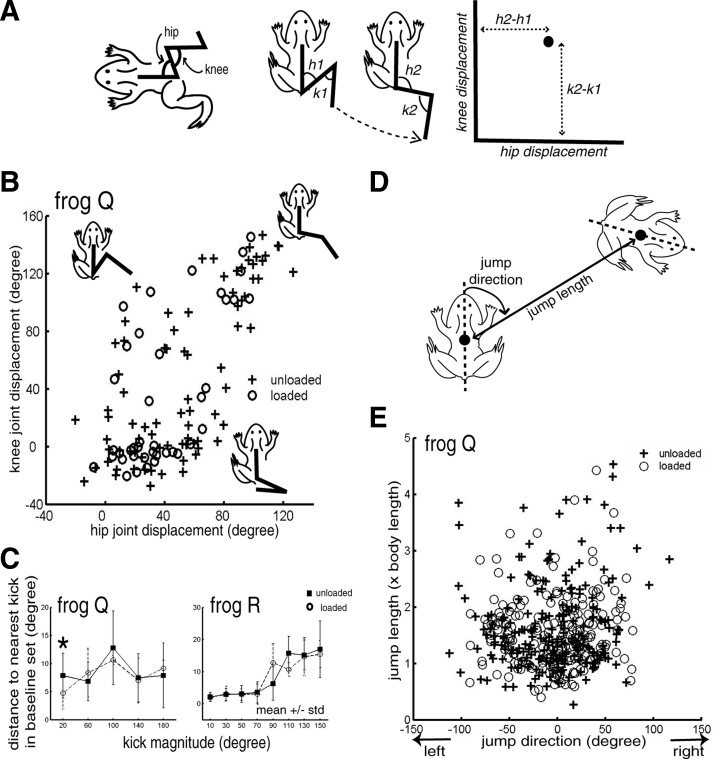

FIG. 2.

Characterizing varieties of kicks and jumps. A: as shown in the leftmost frog diagram, the hip angle is defined as the angle between the body axis and femur; the knee angle is defined as the angle between femur and tibiofibula. The rest of the frog diagrams in this panel illustrate the kick displacement vector, defined as the joint-angle difference between the initial ankle position (h1 and k1) and the kick's maximally extended position (h2 and k2). The hip and knee joint-angle displacements define the x- and y-axes of the kick behavioral space, respectively. B: the extents of distribution of kick varieties in the kick behavioral space before and after inertial loading. As can be seen here, the extents of distribution of unloaded (+) and loaded (○) kick varieties almost completely overlap each other. The 3 frog cartoons shown in the figure indicate where lateral kicks (top left), caudal–lateral kicks (top right), and caudal kicks (bottom) lie in the kick behavioral space. C: the distribution extents of the unloaded and loaded kicks were quantified by first defining a baseline set of kicks (for definition, see methods, Trajectory analysis) and then calculating the Euclidean distance between each kick and its closest baseline neighbor in the behavioral space. After binning the kicks by kick magnitude (defined as the magnitude of the kick displacement vector), we plotted the distances for the loaded (○) and unloaded (▪) kicks (mean ± SD). For all bins (except the first bin of frog Q, marked by *), the unloaded and loaded distances are not significantly different from each other (P > 0.05). This suggests that the differences between the loaded and baseline kicks are not more than the differences among the unloaded kicks. D: jump length is defined as the distance of the line connecting the initial and final midpoint positions of the frog. Jump direction is defined as the angle between the initial body axis and the line connecting the frog's initial and final midpoint positions. Positive angles are assigned to rightward jumps and negative angles, to leftward jumps. E: distribution extents of jump varieties before (+) and after (○) inertial loading. The jump behavioral space is represented by both jump length (y-axis, expressed as a multiple of the body length) and jump direction (x-axis). The 2 distributions almost completely overlap each other in extent.

To facilitate subsequent comparisons of unloaded and loaded EMGs from episodes with similar behavioral attributes (see Behavioral parameterizations in coefficient comparisons in the following text), each kick or jump was further characterized by two behavioral parameters, defining the episode at a fixed point in a two-dimensional behavioral space. For kicks, this space is represented by the kick displacement vector, defined by the hip displacement angle (h2–h1 in Fig. 2A) and the knee displacement angle (k2–k1) from the initial limb position to the maximally extended position (in joint space) during the kick. These two displacement angles of the vector define the x- and y-axes of the kick behavioral space, respectively (Fig. 2B), and the magnitude of the displacement vector defines the kick magnitude. The jump behavioral space is represented by the jump length (y-axis) and jump direction (x-axis) (Fig. 2E). Jump length is defined as the distance between the initial and final midpoint positions of the frog (Fig. 2D). Jump direction is defined as the angle between the initial body axis and the line connecting the initial and final midpoint positions of the frog (Fig. 2D); a positive angle was assigned to a rightward jump and a negative angle, to a leftward jump.

Trajectory analysis

For kicks of three frogs (P, Q, and R) and jumps of one frog (R), we examined the progress and degree of trajectory compensation to the added load by quantifying the difference between the loaded and unloaded trajectories in joint space. We sought to compare trajectories of loaded and unloaded episodes located at similar positions in the behavioral space, so that any trajectory differences are likely to reflect deviations caused by the load rather than natural differences between the trajectories of different behavioral varieties. To this end, for each behavior and each frog, we first defined a baseline set of unloaded episodes against which all episodes were compared. This baseline set was composed of all unloaded episodes collected before the first loaded epoch (preload), as well as all postperturbation episodes excepting those collected from the first trial of those epochs (containing roughly 30 episodes of different behaviors), whose EMGs might potentially reflect “aftereffects” of motor learning. Then, for every loaded and unloaded episode (including every episode in the baseline set), the five episodes in the baseline set lying closest to that episode in the behavioral space were identified; the distances between the trajectory of the episode in question and those of its neighboring baseline episodes (distance to be defined in the following text) were calculated and then averaged. The degree of trajectory compensation can then be examined by comparing the distances for the loaded episodes with those for the unloaded episodes. Distance between trajectories was quantified by the figural distance measure described in Conditt et al. (1997). This measure captures differences in trajectory shapes, but contains no information on speed or higher-order differences. All trajectories were represented in joint space defined by the hip and knee angles, with the space origin denoting the initial joint angles. For kicks, we also calculated the figural distances for the extension and flexion phases separately and then averaged them for each kick so that any phase-dependent trajectory differences can be captured by this distance measure.

EMG preprocessing and normalization

Electromyographic signals were amplified (gain of 10,000), band-passed filtered (10–1,000 Hz) through differential AC amplifiers (Model 1700, A-M Systems, Carlsborg, WA), and digitized (1,000 Hz). Using custom Matlab software, the continuous EMG trace of each trial was manually parsed into episodes, subsequently categorized into different behaviors according to their corresponding video records. Each episode contained a single kick or jump or, in the cases of stepping and swimming, one or several consecutive movement cycles. The parsed data were high-pass filtered (window-based finite impulse response [FIR] filter; 50th-order; cutoff of 50 Hz) to remove motion artifacts, rectified, low-passed filtered (FIR; 50th-order; 20 Hz) to remove noise, and integrated over 10-ms intervals to capture envelopes of EMG activity.

After integration, for every behavior, the variance of each muscle in the EMG data set was normalized to one, so that results of the muscle synergy extraction algorithm used in subsequent analyses will not be biased into describing only the high-variance muscles (Torres-Oviedo et al. 2006).

Data analysis: the muscle synergy model

In this study, we set out to investigate whether any systematic EMG changes associated with inertial loading can be characterized as changes in the recruitment pattern of invariant muscle synergies or, alternatively, as changes in the muscular compositions of all or selected muscle synergies. Following our earlier studies (Cheung et al. 2005; Tresch et al. 1999, 2006), we modeled the EMGs collected under the unloaded or loaded conditions as a linear combination of a set of muscle synergies, each represented as a time-invariant activation balance profile across the 13 recorded muscles, and activated by a time-dependent activation coefficient (see also Hart and Giszter 2004; Torres-Oviedo et al. 2006). In this model, it is possible for each muscle to belong to more than one synergy and thus the EMG of any single muscle might be attributed to simultaneous or sequential activations of several muscle synergies. The example in Fig. 1B illustrates this formulation. In the figure, the two bar graphs depict the activation balance profiles of two muscle synergies (synergy 1, black bars; synergy 2, gray bars) activated by two time-varying waveforms, c1(t) and c2(t). The EMGs of three muscles, M1, M2, and M3 (dotted lines), are explained by the combination of synergies 1 and 2, both of which have activation components across all three muscles. The waveform of M2, for instance, is initially contributed by both synergies, followed by synergy 1 (black), and then both synergies again. This definition of muscle synergy thus differs from those in which each muscle belongs to only one synergy at any time point (Krouchev et al. 2006).

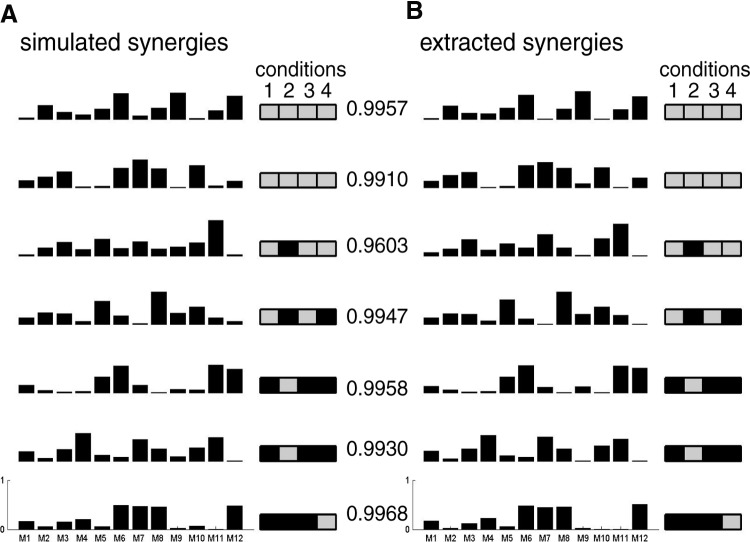

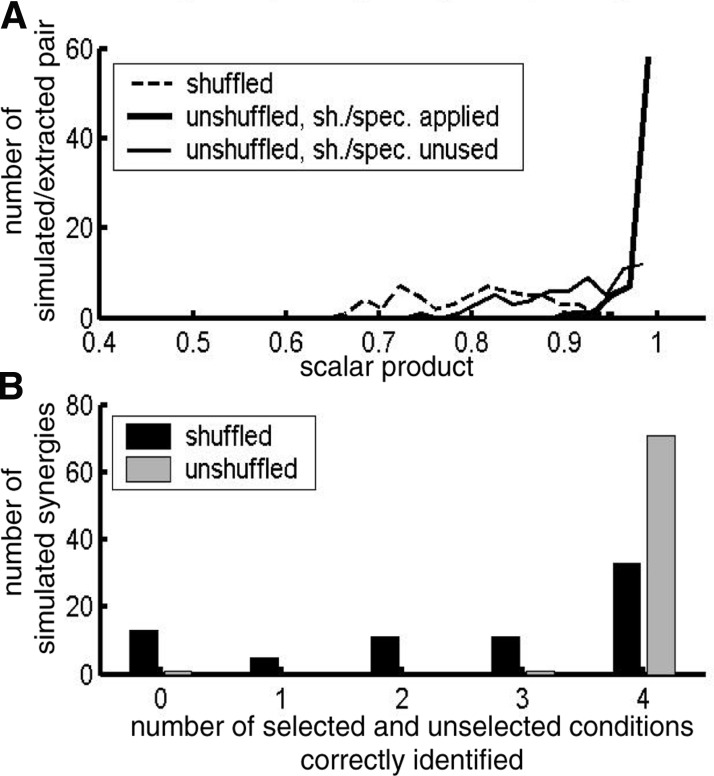

The EMGs of each frog and behavior analyzed here include data collected from different loading conditions: for instance, for frog P, there were five conditions, including preload, load1, postload1, load2, and postload2 (Fig. 1A). The goals of the present data analyses are 1) to objectively identify the synergies and their activation coefficients from the unloaded and loaded EMGs, 2) to assess the extent to which the identified muscle synergies were preserved across the different loading conditions, and 3) for the synergies remaining invariant across loading conditions, to compare the synergy activation patterns observed in the unloaded conditions with those observed in the loaded conditions. We achieved the first two goals by using a novel adaptation of the nonnegative matrix factorization (NMF) algorithm (Lee and Seung 1999, 2001) to extract muscle synergies from the pooled unloaded and loaded EMGs. The NMF algorithm requires the number of synergies extracted from the EMGs to be specified a priori. In the following text, we first describe how we determined the numbers of synergies embedded within the EMGs of the different conditions. We then outline how the NMF algorithm was manipulated in this study for assessing which of the synergies extracted were invariant across which conditions. Finally we describe the statistical methods we used for comparing synergy coefficients of the unloaded and loaded conditions.

Determining data dimensionalities

To initialize the NMF algorithm, it is necessary to determine the number of synergies underlying the EMGs collected from each of the preload, load, and postload conditions. In previous studies (Cheung et al. 2005; d'Avella et al. 2003; Tresch et al. 2006), this number was chosen by plotting the R2 or log-likelihood of EMG reconstruction against the number of synergies extracted; the number of synergies at the point on the curve with maximum curvature is then presumed to be the “correct” number of synergies. Although this ad hoc procedure has been shown to be very robust in simulated data composed of synergies with equal amounts of variance contribution (Tresch et al. 2006), its application in experimental data sets collected from natural behaviors has remained difficult because the R2 curves obtained often do not show unambiguously a point with abrupt slope change (e.g., see Cheung et al. 2005; their Figs. 3A and 7A).

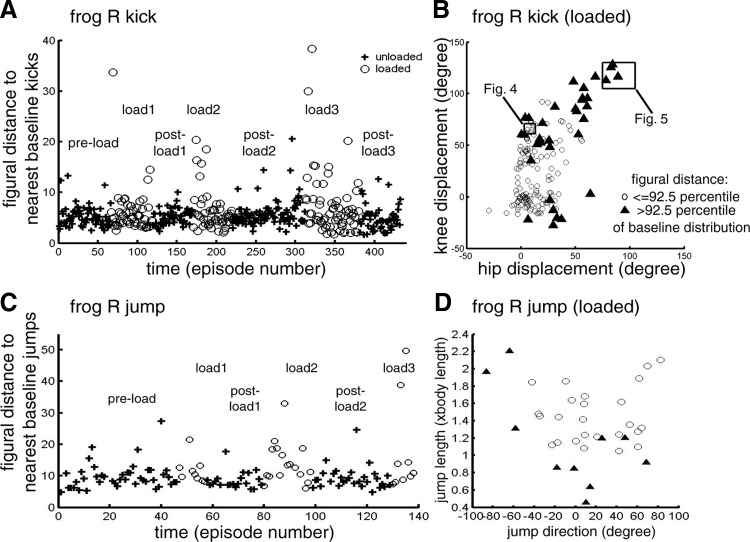

FIG. 3.

The inertial load's effect on kick and jump trajectories. A and C: for each kick (A) and jump (C) episode, the average distance between the episode's joint-space trajectory (with space origin denoting the initial limb position) and those of the 5 baseline neighbors closest to that episode in the behavioral space was calculated. Trajectory distance was quantified by the figural distance measure introduced by Conditt et al. (1997). Plots of this distance against time (represented as chronologically ordered episode number) show that for both kicks (A) and jumps (C), there was no increase in figural distance in the beginning of the postload epochs, suggesting that EMG changes associated with loading represent immediate motor pattern adjustments rather than motor learning. B and D: in the loaded epochs (load1, load2, and load3), there were several episodes with notably higher figural distances (as shown in A and C). Shown here are positions of the loaded kicks (B) and loaded jumps (D) in their respective behavioral spaces; those with figural distances above the 92.5 percentile of the baseline distribution of figural distance are marked by ▴ and the rest, by ○. In B, we see that most of the marked episodes are caudal–lateral kicks of larger magnitudes. In D, we see that the marked episodes include both shorter rightward jumps and longer leftward jumps. These plots suggest that in selected regions of the behavioral space, there were load-related trajectory changes due either to incomplete compensation to the inertial load or to compensatory EMG changes that caused trajectory deviations. In B, the 2 boxes indicate the behavioral-space regions from which the kick examples shown in Figs. 4 and 5 are taken.

In light of this difficulty, we implemented another method, based on estimating the R2 confidence interval (CI), to ensure both consistency in choosing the number of synergies across loading conditions and adequate description of the data at the chosen number. For each loading condition, including preload, load1, postload1, load2, postload2, and so forth, we first extracted 1 to 10 synergies using NMF without pooling data from different conditions. After convergence of the algorithm, the 95% CI of the EMG reconstruction R2 was estimated by bootstrapping, a commonly used statistical procedure for empirically obtaining information about the uncertainty of a parameter. In our bootstrapping, the data set of each condition was resampled 300 to 1,000 times with replacement of EMG episodes (i.e., the same EMG episode may appear multiple times in the resampled data set). As in standard bootstrapping methods, the resampled data set contained the same number of EMG episodes as the original data set. After each resampling, the R2 was recalculated. Because each resampling was done with episode replacement, the set of 300–1,000 bootstrapped R2 values would follow a certain distribution, allowing estimation of the uncertainty of the actual R2 value. After sorting this set of R2 values in ascending order, the lower and upper bounds of the 95% CI were then estimated to be the 2.5 and 97.5 percentiles of the R2 distribution, respectively.

Following R2–CI estimation, we selected the numbers of synergies for each condition by first finding an appropriate number for the EMGs of the preload condition and, then, using the preload R2–CI at its chosen number of synergies as a reference R2 interval against which the numbers for the other load and postload conditions were chosen. The preload number of synergies was estimated to be the minimum number at which the extraction repetition yielding the highest R2 has a corresponding CI–upper bound >90%. Such a criterion seems reasonable to us, given that in previous studies (Cheung et al. 2005; d'Avella 2000) most of the R2 curves were obtained using the NMF plateau to a straight line at about 90%. For the other load and postload conditions, the number of synergies was chosen to be the minimum number at which at least one extraction repetition yields an R2 whose CI overlaps with at least half of the preload R2–CI. This criterion guarantees that the EMG data from all conditions are described equally well at their chosen numbers of synergies.

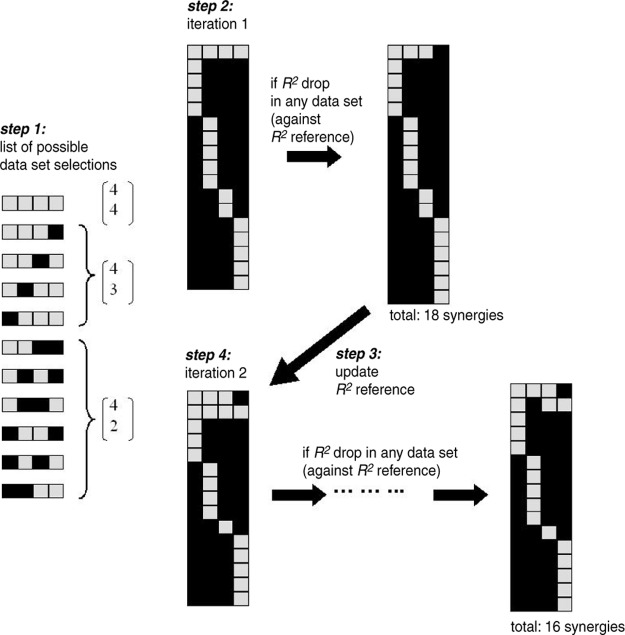

Extracting shared and specific synergies across multiple conditions

In the procedure for selecting numbers of synergies outlined earlier, we extracted muscle synergies from each loading condition separately to estimate data dimensionalities. An obvious way to assess whether there are synergies that remain invariant across loading conditions is to examine these synergies extracted separately from each condition and then to determine their similarity. However, interpreting results obtained from this approach is difficult. As we have pointed out previously (Cheung et al. 2005), the subspace in the muscle space embedding the EMGs may be represented by many equivalent sets of synergies whose nonnegative activations span different regions of the subspace. It follows that any difference between synergies of different conditions could just be a consequence of the limited data variability within each condition available to the algorithm, thus resulting in different synergy sets spanning different regions of the same subspace, rather than a reflection of differences in the EMG subspace. This difficulty in synergy extraction is conceptually similar to the problem in standard regression analysis that two different samples drawn from the same population might yield different estimates for the same parameter because each sample contains only limited data variance for consistent parameter estimation.

An obvious alternative to separate extractions is to extract synergies from the data set pooling together EMGs of all conditions. However, this approach presupposes that the different conditions share the same set of synergies, which is precisely what we attempt to test. Moreover, in such an approach, no prior information on potential differences in data dimensionalities between conditions is provided to the algorithm and, consequently, the extracted synergies and their corresponding coefficients might describe some conditions better than the other. Interpreting the extraction results then becomes difficult.

To overcome these problems, we developed an NMF-based procedure that uses all available data to maximize the data variability available to the algorithm during extraction, but at the same time allows the possibility for any condition-specific synergies to be extracted. Such a possibility has been explored in our previous study (Cheung et al. 2005), in which we outline a procedure for comparing data from two conditions. Here, we generalize our original formulation so that synergies shared by more than two conditions as well as synergies specific to one or several conditions can be simultaneously extracted from an arbitrary number of data sets.

The procedure we developed is described in the appendix. Briefly, parallel extractions of shared and specific synergies were achieved by exploiting NMF's multiplicative update rules, as a consequence of which any synergy forced to be inactivated (i.e., having zero coefficient) over a condition at the algorithm's initial iteration remains inactivated over that condition throughout all subsequent iterations. Our procedure systematically finds, for each synergy, an activation selection across conditions, guaranteeing that the EMGs of the different conditions are described at similarly high R2 values. Taking the EMG data of all conditions and their respective data dimensionalities as inputs, the procedure returns 1) a set of synergies, 2) the time-varying coefficients for the synergies, and 3) for each synergy, a condition selection indicating in which conditions the synergy is activated (e.g., a condition selection for a fixed synergy active in all conditions would include all unloaded and loaded conditions; a selection for a synergy activated only after inertial loading would include just load1, load2, and load3).

When analyzing EMGs, to guarantee that the extraction was not biased toward a particular condition containing more data samples than the other, in all extractions the number of EMG episodes used for each condition was chosen such that the numbers of data samples across conditions were approximately the same. Each extraction was repeated 20 times, each time with random initial conditions (uniformly distributed between 0 and 1) and random subsets of EMG episodes. Convergence was defined as having 20 consecutive iterations with a change of R2 <0.01%. The extraction repetition with the highest overall R2 was selected for further coefficient analyses. The magnitude of every synergy vector was normalized to unit Euclidean norm and their coefficients were multiplied by the synergy's original magnitude, so that all coefficients subsequently analyzed represent activations of unit vectors.

Detecting activation bursts of synergy coefficients

For kick and jump synergies found to be shared by multiple loaded or unloaded conditions, we analyzed whether loading changed their patterns of activation by comparing the coefficient time traces for the unloaded EMGs with those for the loaded EMGs. Specifically, we compared the peak amplitude, duration, and onset time of the activation coefficient bursts of each shared synergy across conditions. We focused on analyzing coefficients of kicks and jumps because we were able to extract sufficient kicking and jumping kinematics for the behavioral parameterizations involved in our comparison (see following text).

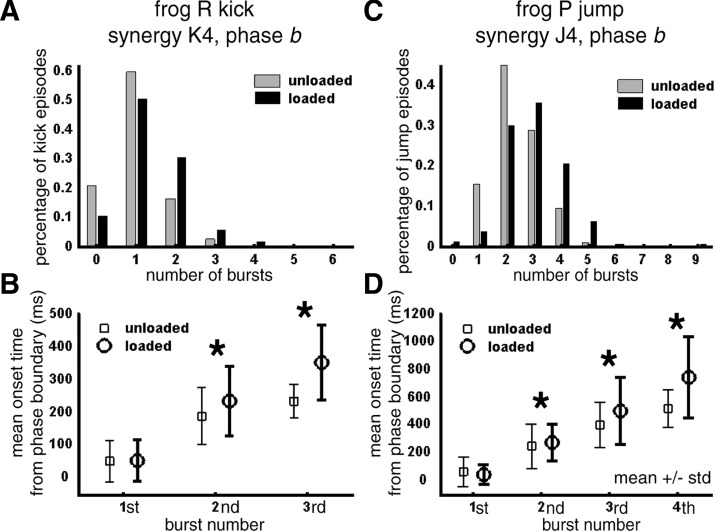

Before comparison, we first divided each kick or jump episode into two segments (phases a and b), corresponding to the extension and flexion phases, respectively; this parsing was accomplished by marking the offset time of the extensor bursts using a custom Matlab GUI. Within each phase, the onset and offset times of the activation coefficient bursts were automatically detected by a thresholding procedure. First, for each experimental session and for each muscle synergy all coefficient time points with amplitude exceeding 5% of the maximum coefficient amplitude observed in that synergy during that session were isolated. Any continuous segment of isolated data points was considered to be an activation burst. Then, to prevent any sustained coefficient activity from being fragmented into many short bursts, we further merged any two bursts within the same phase into one if the time gap between their activations was <20 ms. After the merging step, any bursts with duration <40 ms were filtered out and excluded from further analysis. We have found that this burst-detection procedure isolated burst onset and offset times similar to those marked manually by a Matlab GUI (see Fig. 8A for an example of a coefficient time trace comprising five bursts with their onset and offset times isolated by our burst-detection method). The automatic procedure, however, ensures that the times were marked objectively and consistently.

The number of bursts detected in either phase varies across episodes; to keep our statistical analysis tractable, in our duration and magnitude comparisons for each phase, we compared the total burst duration (i.e., in Fig. 8A, d1 + d2 for phase a; d3 + d4 + d5 for phase b) and the maximum burst peak magnitude (in Fig. 8A, p2 for phase a; p4 for phase b) across the unloaded and loaded conditions. The number of bursts and burst onset times were analyzed separately (see following text).

Behavioral parameterizations in coefficient comparisons

As in our trajectory analysis, in our coefficient comparison for each phase, we sought to compare loaded and unloaded episodes at similar positions in the behavioral space, so that any differences in coefficient amplitude and/or duration between them are likely to reflect activation changes for loading compensation rather than those for producing different behavioral varieties. To this end, the coefficient amplitude and duration of every loaded and unloaded episode were compared against those of the five baseline episodes closest to the episode in question in the behavioral space (see Trajectory analysis for definition of baseline set). Thus for each synergy and in each phase, we calculated the average difference, in coefficient burst duration and amplitude, between each episode and its neighboring baseline episodes. The effect of loading on synergy recruitment can then be assessed by comparing the average difference values of the loaded episodes with those of the baseline episodes. For instance, if, for either duration or peak amplitude, both the difference values of the loaded episodes and those of the baseline episodes cluster around zero, the coefficient of that synergy is not modulated by loading. If, on the other hand, the duration difference values of the loaded episodes lie above the distribution of the baseline duration difference values, the duration of that synergy is prolonged by loading. A test of statistical significance (α = 0.05) was performed on the difference values for each loaded episode. The null hypothesis that the loaded value is the same as the mean baseline value was rejected if the loaded value was >97.5 or <2.5 percentile of the baseline distribution.

Comparing coefficient burst onset times

For phase b (flexion phase), we examined whether loading affected the timing of synergy activation by comparing the coefficient burst onset times of the loaded episodes with those of the unloaded episodes. All burst onset times were specified as the time elapsed since the phase boundary. The unloaded and loaded onset times for each order of phase b burst were compared separately; thus for the first burst, only the episodes containing one or more bursts in phase b were included in the comparison; for the second burst, only those with two or more bursts were included, and so on. Statistical hypotheses on whether the loaded and unloaded means were the same were assessed by the Kruskal–Wallis test (α = 0.05).

RESULTS

Herein, we study how increasing limb inertia affects motor coordination by recording EMGs from 13 right hindlimb muscles before and after wrapping a weight around the calf. Both terrestrial behaviors (frogs P, Q, and R) and aquatic behaviors (frog S) were examined. Numbers of behavioral episodes included in our analyses are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Number of episodes collected from each behavior in each loading condition

| Frog | Behavior | Preload | Load1 | Postload1 | Load2 | Postload2 | Load3 | Postload3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | Kick | 31 | 22 | 13 | 24 | 12 | — | — |

| Jump | 105 | 118 | 48 | 114 | 34 | — | — | |

| Step | 24 (29) | 30 (43) | 17 (29) | 38 (58) | 16 (22) | — | — | |

| Q | Kick | 22 | 22 | 16 | 13 | 21 | 6 | 21 |

| Jump | 79 | 89 | 30 | 61 | 49 | 45 | 59 | |

| Step | 47 (70) | 30 (48) | 14 (30) | 20 (35) | 23 (37) | 17 (25) | 19 (31) | |

| R | Kick | 66 | 53 | 51 | 49 | 93 | 68 | 53 |

| Jump | 46 | 11 | 22 | 19 | 31 | 9 | — | |

| Step | 22 (33) | 29 (44) | 34 (47) | 25 (37) | 38 (44) | — | — | |

| S | Swim | 59 (302) | 23 (111) | 49 (315) | 34 (182) | 33 (210) | — | — |

For kicking and jumping, each episode contains only one instance of the behavior. For stepping and swimming, each episode contains one or multiple consecutive movement cycles. Numbers in parentheses refer to numbers of cycles observed in the different epochs.

Behavioral varieties before and after inertial loading

We first examined how the added inertial load might change the frog's behavioral repertoire. In many previous perturbation studies, the subject was trained to perform specific motor tasks prior to perturbation delivery (e.g., see Mussa-Ivaldi and Bizzi 2000). By means of training or explicit instructions, the subject's intent of executing a fixed task or trajectory was kept constant throughout the experiment; the degree of motor compensation was then characterized as the extent to which the same trajectory was realized under the perturbed condition. Here, we study natural motor behaviors of the frog, which is not very susceptible to motor task training due to its low overall spontaneous motor activity (Thompson and Boice 1975). Because our frogs were untrained, we could only compare the loaded and unloaded trajectories and EMGs of those episodes similar in their behavioral varieties (e.g., episodes with similar kick amplitudes and directions), assuming that such a similarity also reflects similarity in the frog's motor behavioral goal. To this end, we characterized the distributions of behavioral varieties before and after loading to see whether they intersect sufficiently to allow meaningful comparisons of loaded and unloaded data. Among the four behaviors studied, we focused on comparing the behavioral distributions of kicking and jumping before and after loading because the stepping and swimming kinematics were not available to us at the moment of our analyses.

Kick varieties were characterized by the hip and knee displacement angles from the initial limb position to the maximally extended position during the kick (Fig. 2A). In all frogs, the inertial load did not significantly alter the varieties displayed. For instance, for frog Q (Fig. 2B), distribution of kick varieties for the loaded kicks (○) is very similar in extent to that for the unloaded kicks (+). We further quantified this similarity by calculating the Euclidean distance of each unloaded and loaded kick to its nearest unloaded baseline neighbor in the behavioral space. For all frogs and for all kick magnitudes (except one magnitude bin in frog Q) the mean distance to the nearest baseline kick for the unloaded kicks is not statistically different from that for the loaded kicks (Kruskal–Wallis, P > 0.05; Fig. 2C; frog P not shown). For the one bin showing a significant difference (frog Q, kick magnitude = 0–40°; P < 0.05), the mean distance to baseline for the loaded kicks is even smaller than the mean for the unloaded (Fig. 2C) kicks. These results suggest that the overall differences in kick displacement angles between the loaded and baseline kicks are not larger than those among the unloaded kicks, implying that the unloaded and loaded kick varieties had very similar extents of distribution.

Likewise, the unloaded and loaded jump varieties also had very similar extents of distribution in the jump behavioral space, defined by the jump direction (x-axis) and length (y-axis) (Fig. 2D). As shown in Fig. 2E, the behavioral distribution for unloaded jumps (○) almost completely overlaps that for loaded jumps (+). For all three frogs, the mean distances to the nearest baseline jump of all the unloaded and loaded conditions are not significantly different from each other (P > 0.05).

The preceding analysis confirms that for kicks and jumps, the distributions of behavioral varieties before and after loading intersect nontrivially, allowing subsequent comparisons of loaded and unloaded trajectories and EMGs for revealing deviations caused by the inertial load.

Trajectories before and after inertial loading

Having established that the inertial load did not change the distributions of jump and kick varieties, we proceeded to examine the progress and degree of trajectory compensation by quantifying the similarity between the unloaded and loaded joint-space trajectories. Quantification was accomplished by calculating the average figural distance (Conditt et al. 1997) between the trajectory of every episode and those of its neighboring baseline episodes in the behavioral space. This distance reflects the shape difference between trajectories belonging to similar varieties.

It is apparent in plots of the figural distance against time (kick of frog R, Fig. 3A; jump of frog R, Fig. 3C) that the distributions of figural distance for the unloaded (+) and loaded (○) episodes substantially overlap with each other, indicating that the differences between most loaded trajectories and their unloaded neighbors are no larger than the differences among baseline trajectories. This suggests that for most kicks and jumps, the frog was able to compensate for the load to effect similar trajectories. Importantly, there was no increase in figural distance in the beginning of all postload epochs, implying that the trajectories exhibited on load removal were not much different from the baseline trajectories. The absence of aftereffect suggests that any changes in EMGs or synergy coefficient activations associated with loading (described in the following text) were likely results of immediate adjustment of motor outputs mediated by altered sensory signals rather than consequences of motor learning.

In Fig. 3, A and C, there are a few loaded episodes with notably larger figural distances (e.g., several in load3 of Fig. 3A and two in load3 of Fig. 3C), representing loaded trajectories different from their unloaded neighbors. In Fig. 3, B and D, the loaded kicks and jumps with figural distances >92.5 percentile of the baseline distribution of figural distances are marked by ▴. For kicks (Fig. 3B), most marked episodes are caudal or caudal–lateral kicks of larger magnitudes; for jumps (Fig. 3D), the marked episodes include both longer leftward jumps and shorter rightward jumps. Thus in selected regions of the behavioral space, there were trajectory changes induced by the added inertial load.

Below we illustrate how load-related trajectory changes are dependent on the behavioral variety performed. Figures 4 and 5 show loaded and unloaded kick trajectories taken respectively from two different regions in the kick behavioral space (Fig. 4: lateral kicks; Fig. 5: caudal–lateral kicks), represented as either joint angles (middle row) or ankle trajectories (bottom row; extension: solid line; flexion: dotted line). We see in the joint-angle plots of Fig. 4 that after loading, during the kick's return phase the knee flexed with a slower speed than before load attachment, consistent with observations of decreased limb velocity on inertial loading reported in previous studies (Gottlieb 1996; Happee 1993; Khan et al. 1999). However, for their ankle trajectories, the preload (Fig. 4A) and postload (Fig. 4, F–I) trajectories were very similar in shape to those of kicks recorded both early (Fig. 4B) and late (Fig. 4, C–E) during the loaded epoch, agreeing with the figural-distance analysis shown earlier (Fig. 3B). For the caudal–lateral kicks shown in Fig. 5, however, the loaded and unloaded ankle trajectories were noticeably different. Although the unloaded ankle trajectories (Fig. 5, A, E, and F) all rotated in the counterclockwise direction with the extension trajectory medial to the flexion trajectory, the loaded kicks (Fig. 5, B–D) showed the reverse clockwise pattern, with the ankle moving more laterally during extension than during flexion. The joint-angle plots further reveal that this alteration was due to a slower hip extension after loading. In the three loaded kicks, during extension the hip angle (dotted line) increased with a smaller slope than the knee angle (solid line), but in the unloaded episodes this slope difference between the two joints was not as obvious. In two of the loaded episodes (Fig. 5, B and C), the hip even continued to extend further as the knee started to flex. Thus for this kick variety the inertial load induced trajectory changes, which may be regarded as either incomplete load compensation or compensatory trajectory adjustment after perturbation (Krakauer 2007).

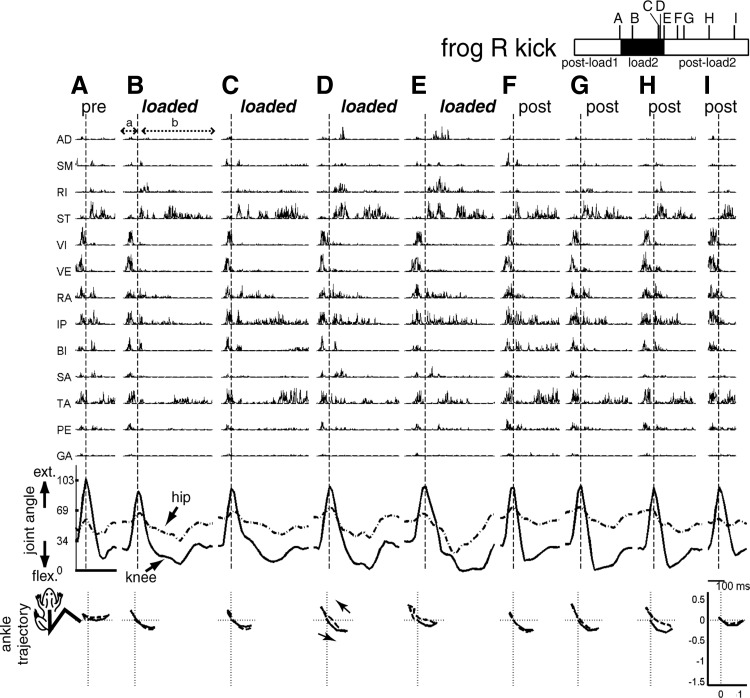

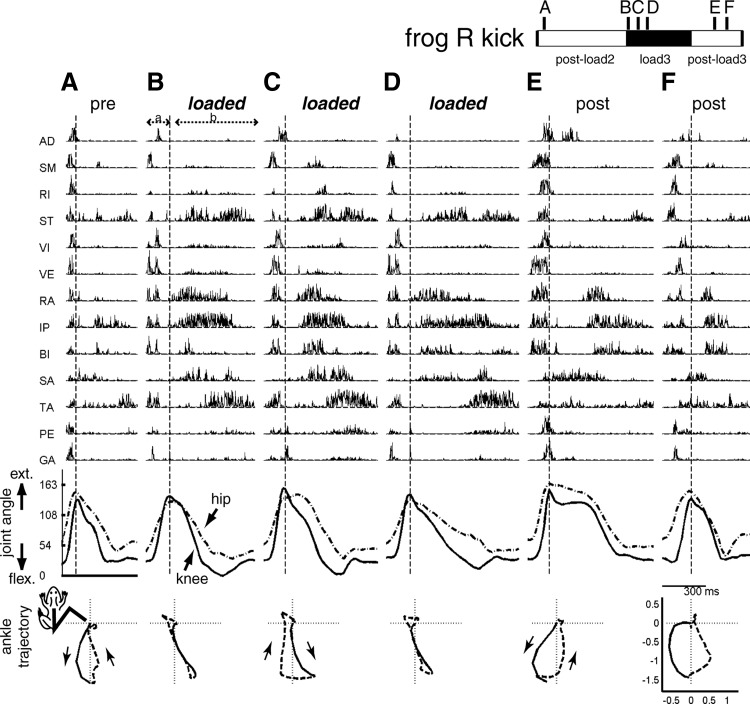

FIG. 4.

Examples of EMG and kinematic data of lateral kicks collected before, during, and after inertial loading. Shown here are 9 kicks with similar kick displacement vectors (their locations in the kick behavioral space shown in Fig. 3B) taken from preload (A), loaded (B–E), and postload (F–I) trials of the postload1, load2, and postload2 epochs of frog R, respectively. The temporal locations of these nine kicks within those epochs are indicated in the bar shown in the figure's top right corner. Each kick is divided into 2 phases, a and b, roughly corresponding to the extension and flexion phases, respectively. Phase boundary is indicated in each episode by a vertical dotted line. EMG data shown here (1,000 Hz) were high-pass filtered (finite impulse response filter, 50th order, cutoff of 50 Hz), to remove motion artifacts, and then rectified. Kinematic data shown here (59.64 Hz) were extracted from deinterlaced videoimages. Joint extension is indicated by an increasing angle (hip angle, dotted line; knee angle, solid line) and joint flexion is indicated by a decreasing angle. The EMG and kinematic data were synchronized by a digital counter. Here, the depicted EMG data are time shifted to the right by 62 ms to account for electromechanical delay. Figures in the bottom row display the ankle trajectory of each kick. In each of those bottom row figures, the origin denotes the initial ankle position; trajectory of phase a is shown in solid line and trajectory of phase b, in dotted line. Both the femur and tibiofibula are depicted as straight lines with lengths of 1. For more descriptions of these EMGs and kinematic data, see results (Trajectories before and after inertial loading and EMG changes after inertial loading).

FIG. 5.

Examples of EMG and kinematic data of caudal–lateral kicks collected before, during, and after inertial loading. Shown here are six kicks with similar kick displacement vectors (their locations in the kick behavioral space shown in Fig. 3B) taken from preload (A), loaded (B–D), and postload (E–F) trials of the postload2, load3, and postload3 epochs of frog R, respectively. The temporal locations of these 6 kicks within those epochs are indicated in the bar shown in the figure's top right corner. Specifications of the EMGs and kinematic data shown here are the same as those described in the legend to Fig. 4. Notice that the ankle trajectories of the unloaded kicks (A, E, F) rotate in the anticlockwise direction, whereas those of the loaded kicks (B–D) rotate in the clockwise direction. For more descriptions of these EMGs and kinematic data, see results (Trajectories before and after inertial loading and EMG changes after inertial loading).

EMG changes after inertial loading

Before comparing synergies of the different loading conditions systematically, it is instructive to inspect the loaded and unloaded EMGs of the kick episodes shown in Figs. 4 and 5. The EMG of each kick was divided into two phases, labeled a and b, corresponding to the extension and flexion phases, respectively. In Fig. 4, we notice that phase a EMGs of the loaded kicks are very similar to those of the unloaded kicks, all characterized by short bursts of VI, VE, RA, IP, and TA. However, the same cannot be said for phase b. In the loaded phase b the durations of the ST, RA, and IP bursts are much longer than those in the unloaded episodes. Also, while in the phase b of all kicks two bursts of ST activity are present, in the loaded kicks the activation onset of the two bursts are separated further apart from each other than in the pre- and postload kicks. In the last two loaded kicks (Fig. 4, D and E), there are also prominent phase b activities of AD and RI not present in all other kicks in the figure. As described in the previous section, the loaded and unloaded endpoint trajectories of these kicks were quite similar in shape. The load-related EMG alterations noted here were thus likely changes induced for maintaining the same trajectory under the perturbed condition. The similarity of the pre- and postload examples also points to the reversibility of the EMG changes on load removal, further supporting that the altered muscle activation pattern in the loaded kicks was related to execution of compensatory motor strategies.

With respect to the caudal–lateral kicks shown in Fig. 5, noticeable phase a changes after loading include decreases in the RI and ST burst amplitude, seen in Fig. 5, B–D. Since both of these muscles have hip extensor action, their decreases in amplitude here may be responsible for the slower hip extension of the loaded caudal–lateral kick described in the previous section. However, as in Fig. 4, the most dramatic EMG alteration after inertial loading occurs in phase b. In the loaded examples, we see increases in the burst duration and amplitude of ST, RA, IP, SA, and TA. Despite these prominent changes, the groupings of the muscles active in phase b seem to remain the same in both the loaded and unloaded examples in the figure: the phase b bursts of RA, IP, and BI are always followed by the bursts of TA and ST. This observation points to the possibility that there exist muscle groupings, or synergies, remaining invariant across loading conditions. In the following text, we evaluate this proposition systematically by adapting the nonnegative matrix factorization (NMF) algorithm (described in the appendix) to analyze our muscle data, using it both as an objective means for identifying synergies from the EMGs and for indicating whether any extracted synergy was activated across the different preload, load, and postload conditions.

Determining dimensionalities of EMG data sets

As the first step of our NMF analyses, we determined the dimensionality of the EMGs of each unloaded and loaded condition by finding the number of NMF synergies explaining the data set of each condition with an R2 of about 90% (assuming similar noise magnitudes across data of all conditions). For frogs P and S, there were five conditions, including preload, load1, postload1, load2, and postload2. For frogs Q and R, there were seven conditions, including the five listed earlier plus load3 and postload3 (Fig. 1A).

The data sets of both the unloaded and loaded behaviors possess similar dimensionalities. In this analysis, in some behaviors (e.g., kicks of frog Q), we pooled together the data of more than one condition (but always under the same loading status) because the number of behavioral episodes in each of those conditions was too small to yield meaningful results. For all frogs and behaviors, linearly combining five to eight synergies is sufficient to describe the EMGs (13 muscles) of all conditions with R2 of about 90% (Table 2). Also, for all behaviors examined (except jumps of frog Q), the numbers of synergies across conditions differ at most by only one (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Numbers of synergies underlying the EMGs collected from different loading conditions

| Frog | Behavior | R2-CI, % | Cond 1 | Cond 2 | Cond 3 | Cond 4 | Cond 5 | Cond 6 | Cond 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | Kick | 89.9/94.7 | Pre | L1 | L2 | Post1+2 | |||

| 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | ||||||

| Jump | 90.6/92.5 | Pre | L1 | L2 | Post1+2 | ||||

| 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | ||||||

| Step | 89.2/93.3 | Pre | L1 | L2 | Post1+2 | ||||

| 7 | 8 | 7 | 8 | ||||||

| Q | Kick | 88.9/92.5 | Pre | L1+2+3 | Post1+2+3 | ||||

| 6 | 7 | 7 | |||||||

| Jump | 90.7/93.0 | Pre | L1 | Post1 | L2 | Post2 | L3 | Post3 | |

| 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7 | |||

| Step | 91.1/93.6 | Pre | L1 | Post1 | L2 | Post2 | L3 | Post3 | |

| 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 8 | |||

| R | Kick | 88.4/92.5 | Pre | L1 | Post1 | L2 | Post2 | L3 | Post3 |

| 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |||

| Jump | 90.4/92.8 | Pre | L1 | Post1 | L2+3 | Post2 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | |||||

| Step | 88.9/91.2 | Pre | L1 | Post1 | L2 | Post2 | |||

| 7 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |||||

| S | Swim | 91.4/92.9 | Pre | L1 | Post1 | L2 | Post2 | ||

| 7 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 7 |

CI, confidence interval; Cond, condition; Pre, preload trials; L1, first block of loaded trials; Post1, postload1 trials; L2, second block of loaded trials; and so forth.

When compared with the numbers of synergies published in our previous studies of frog behaviors, the numbers of synergies found here, ranging from five to eight (Table 2), are greater than the previously reported numbers by one to two (d'Avella and Bizzi 2005: five synergies with R2 of ∼90%; Cheung et al. 2005: four to six with ∼90%; d'Avella 2000: five to eight synergies but with ∼95%). This is probably because in this study we normalized the EMG variance of each muscle before synergy extraction, a step not performed in the aforementioned studies. Variance normalization seems reasonable to us because it ensures that the compositions of the extracted synergies are not biased toward high-variance muscles. The numbers of synergies selected here, nevertheless, are still compatible with those found in the EMGs of spinalized frogs elicited by N-methyl-d-aspartate iontophoresis (Saltiel et al. 2001, in which seven synergies are used to reconstruct EMGs of 12 muscles with R2 of 91%).

Muscle synergies invariant across loaded and unloaded conditions

Having selected the number of synergies for each condition, we proceeded to identify the muscular compositions of the synergies using our new NMF-based synergy extraction procedure. Our procedure requires the EMGs and the number of synergies of each condition as inputs, and returns 1) the synergies, 2) the synergies' activation coefficients, and 3) for each synergy, a condition selection indicating in which loading condition(s) the synergy is activated (i.e., the subset of conditions in which the synergy contributes to data reconstruction).

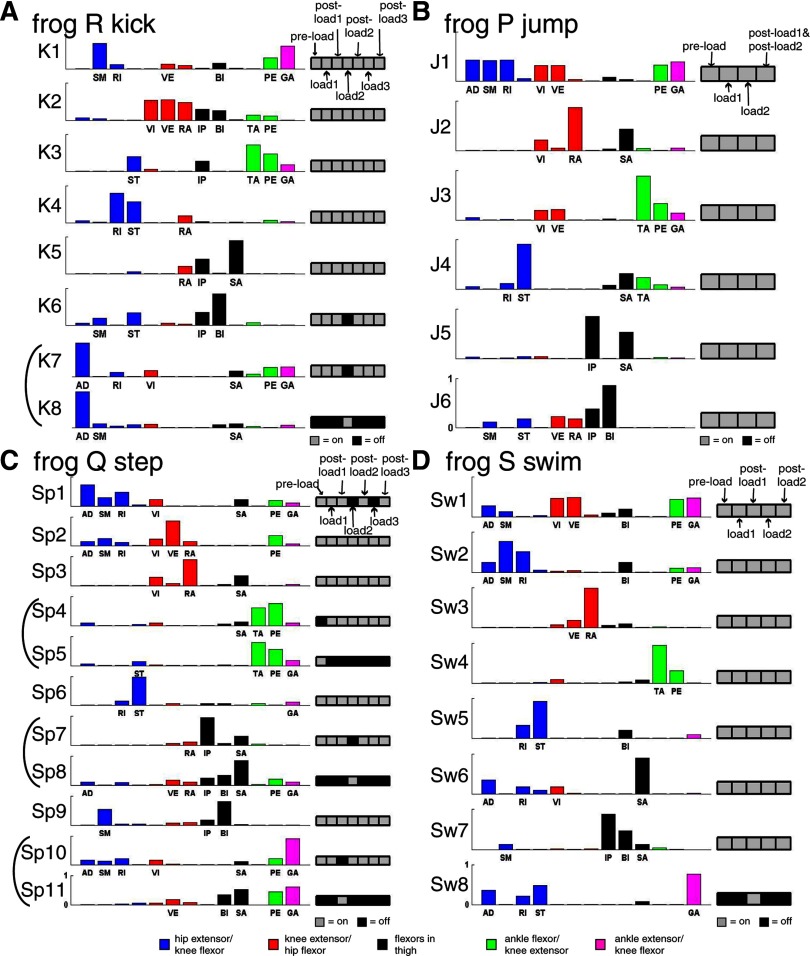

Figure 6 shows results of our extractions for four different behaviors of four different frogs. Each muscle synergy, whose vector magnitude was normalized to unity, is represented as a bar graph depicting the activation balance profile across all 13 recorded muscles. Those bars with component magnitude >0.1 are labeled by their corresponding muscle names, and the moment arm signs of the muscles are denoted by the bar colors (blue: hip extensor/knee flexor; red: knee extensor/hip flexor; black: flexor in the thigh; green: ankle flexor/knee extensor; magenta: ankle extensor/knee flexor). To the right of each synergy is a row of boxes, corresponding to the different loading conditions analyzed (as labeled in the first box row of each panel) and denoting the condition selection of that synergy found by our procedure. Those boxes corresponding to the conditions in which the synergy was found to be activated are colored gray and to those found to be inactivated, colored black. For example, synergy Sp1 (Fig. 6C) was found to be activated in preload, load1, postload1, postload2, and postload3, but inactivated in load2 and load3.

FIG. 6.

Muscle synergies underlying the EMGs of kicking (A), jumping (B), stepping (C), and swimming (D) extracted by our NMF-based procedure. Each muscle synergy shown here, with vector magnitude normalized to unity, is represented as a bar graph across the 13 recorded muscles. The colors of the bars indicate the moment arm signs of the muscles (blue: hip extensor and/or knee flexor; red: knee extensor and hip flexor; black: major flexors in the thigh; green: ankle flexor and knee extensor; magenta: ankle extensor and knee flexor). Bars with component magnitudes >0.1 are labeled by their corresponding abbreviated muscle names (see methods, Implantation of EMG electrodes, for full names of the muscles). To the right of each synergy vector is a row of boxes for depicting a selection of loading conditions in which the synergy was found to be activated by the algorithm. Each box corresponds to a particular loading condition (as labeled in the topmost row in each figure panel). Those boxes corresponding to the conditions in which the synergy was found to be activated are colored gray and those boxes corresponding to the conditions in which the synergy was found to be inactivated are colored black. In A (kick) and C (step), similar pairs of synergies with complementary condition selections (i.e., their selections, when combined, span all conditions) are grouped together by a bracket. As can be seen, most synergies shown in the figure either have selections spanning all conditions or belong to a complementary group. These results suggest strongly that many muscle synergies were invariant across different unloaded and loaded conditions.

In all behaviors examined, most synergies were found by our algorithm to be shared between the unloaded and loaded EMGs. It is evident in Fig. 6 that most of the synergies for kicking (Fig. 6A), jumping (Fig. 6B), and swimming (Fig. 6D) were identified to be activated in all unloaded and loaded conditions (kick: 5/8 synergies; jump: 6/6; swim: 7/8). For stepping (Fig. 6C), only 4 of 11 synergies were activated in all conditions; however, in this synergy set there are three pairs of similar synergies (Sp4/5, Sp7/8, and Sp10/11) whose condition selections are complementary—that is, their selections, when combined, comprise all conditions. One such pair was also found in the synergy set for kicking (Fig. 6A). In Fig. 6, these pairs are grouped together by brackets. We verified that for each behavior, the scalar-product similarity between the synergies within the complementary pairs is higher than that between pairs of all other synergies not belonging to any complementary pair (Kruskal–Wallis, P < 0.05). If we regard each complementary pair as belonging to the same synergy, we see that among the 33 synergies shown in Fig. 6, only 3 synergies have incomplete condition selections (K6 for kick, Sp1 for step, Sw8 for swim). Considering all behaviors of all frogs together, in none of the data sets was more than one synergy with incomplete condition selection extracted (Table 3). This observation of the synergies' robustness across different loading conditions is consistent with our intuitions derived from our visual inspection of the raw EMG data (Figs. 4 and 5) described earlier.

TABLE 3.

Numbers of synergies with complete and incomplete condition selections extracted from the pooled EMGs using our novel NMF-based procedure

| Frog | Behavior | Number of Synergies Complete Cond. Selections | Number of Complementary Synergy Pairs or Groups | Number of Synergies Incomplete Cond. Selections | Remarks for Synergies With Incomplete Cond. Selections |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | Kick | 4 | 2 | 0 | |

| Jump | 6 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Step | 7 | 0 | 1 | Inact.: pre, L2 | |

| Q | Kick | 6 | 0 | 1 | Inact.: pre |

| Jump | 3 | 2 | 1 | Act.: L1, post1, post3 | |

| Step | 4 | 3 | 1 | Inact.: L2, L3 | |

| R | Kick | 5 | 1 | 1 | Inact.: L2 |

| Jump | 5 | 0 | 1 | Act.: L1, L2+3 | |

| Step | 7 | 0 | 1 | Act.: L1 | |

| S | Swim | 7 | 0 | 1 | Act.: post1 |

Cond., condition; Act., activated; Inact., inactivated.

As shown in Fig. 6C, the synergies within each complementary pair are composed of similar muscles and it is possible that they indicate how the balance profile of a synergy is altered across conditions. Alternatively, it is possible that the altered synergy within each pair results from condition-specific noises or general fluctuation of EMG amplitudes across days.

In Fig. 6, there are also three synergies with incomplete data set selections not grouped within a complementary pair. Synergy Sp1, absent in load2 and load3, could represent a synergy inactivated by the load. Synergy K6 is absent only in load2; this is consistent with a later observation (see following text) that both the amplitude and duration of its activation coefficient burst decreased in the other loaded conditions (Table 4). Synergy Sw8 is active only in postload1, but the small data variance explained by it (3.56%) suggests that it probably captures mostly noise or EMGs attributable to condition-specific behavioral variability.

TABLE 4.

Modulation of synergy activations after inertial loading

| Frog/Behavior | Syn. | Muscles | Phase a | Phase b | Phase b Mean Number of Bursts |

Phase b Mean Burst Onset From Phase Boundary, ms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unloaded | Loaded | Ord. | Unloaded | Loaded | |||||

| R/Kick | K1 | SM, RI, VE, BI, PE, GA | |||||||

| K2 | VI, VE, RA, IP, BI, TA, PE | Dur ▴ La, CLa | 0.71 | 0.96 ▴ | |||||

| K3 | ST, IP, TA, PE, GA | 1st | 14 | 36 ▵ | |||||

| 2nd | 358 | 254 ▿ | |||||||

| K4 | RI, ST, RA | Peak ▵ large C, CLa | Peak ▵ La | 1.02 | 1.40 ▴ | 2nd | 189 | 235 ▴ | |

| 3rd | 234 | 351 ▴ | |||||||

| Peak ▿ large, CLa | |||||||||

| K5 | RA, IP, SA | Dur ▵ La | Dur ▴ La, CLa | 1st | 12 | 18 ▵ | |||

| K6 | SM, ST, IP, BI | Peak ▾ La, CLa | 1.25 | 0.86 ▾ | |||||

| Dur ▾ La | |||||||||

| K7/K8# | AD, SA | 0.45 | 0.64 ▵ | 1st | 56 | 113 ▴ | |||

| 2nd | 171 | 270 ▵ | |||||||

| P/Jump | J1 | AD, SM, RI, VI, VE, PE, GA | |||||||

| J2 | VI, RA, SA, | Dur ▴ Rt-Sh, Lt-Me | 1.46 | 2.31 ▴ | |||||

| J3 | VI, VE, TA, PE, GA | 1st | 54 | 101 ▴ | |||||

| 2nd | 222 | 297 ▴ | |||||||

| 4th | 449 | 547 ▵ | |||||||

| J4 | RI, ST, SA, TA | Peak ▵ Rt-Sh, Lt-Me | 2.36 | 3.00 ▴ | 2nd | 250 | 276 ▴ | ||

| 3rd | 404 | 502 ▴ | |||||||

| Dur ▴ Rt-Sh-Me, Lt-Sh-Me | 4th | 519 | 742 ▴ | ||||||

| J5 | IP, SA | Peak ▵ Rt-Sh, Lt-Sh | 1.77 | 2.00 ▵ | |||||

| J6 | SM, ST, VE, RA, IP, BI | 1.78 | 2.07 ▴ | 2nd | 302 | 335 ▵ | |||

| Q/Jump | J1# | AD, SM, RI, VI VE, PE, GA | Dur ▵ Rt-Sh-Me, Lt-Sh-Me | 1st | 144 | 70 ▾ | |||

| J2 | VI, RA, IP, BI SA, GA | 2nd | 175 | 231 ▴ | |||||

| 3rd | 324 | 419 ▵ | |||||||

| J3# | AD, TA, PE | 1.30 | 1.51 ▴ | ||||||

| 2nd | 283 | 301 ▵ | |||||||

| J4 | ST, IP, SA, TA | 1st | 26 | 39 ▴ | |||||

| 2nd | 199 | 209 ▴ | |||||||

| 3rd | 453 | 358 ▾ | |||||||

| J6 | SM, VE, RA IP, BI | ||||||||

Columns 1–3: For frog R kick and frog P jump, the synergy labels (Syn.) shown in this table match those listed in Fig. 6. The muscles listed refer to those with synergy activation component magnitude >0.1 (bold font, >0.5). Groups of similar synergies with complementary selections (#) were compared together as one synergy. For these synergies, coefficient amplitude comparison across loading conditions was omitted because the different muscle balance profiles of the synergies within each group are expected to scale their coefficients differently. Columns 4 and 5: In our coefficient analysis, we compared coefficient amplitude and duration from unloaded and loaded episodes at similar locations in the behavioral space. As explained in results (Modulation of synergy activations after loading in selected regions of behavioral space), we first calculated the difference in peak amplitude or duration between each loaded episode and its unloaded baseline neighbors; we then plotted the difference values in behavioral space to see whether modulation was a function of the behavioral variety performed (Fig. 8, B–F). We summarize whether the peak amplitude (Peak) or duration (Dur) of each synergy during each phase was observed to be up-modulated (▴ and ▵) or down-modulated (▾ and ▿). The modulated regions of the behavioral space are indicated below the triangles. Filled triangles (▴ and ▾): number of loaded episodes above/below baseline (i.e., >97.5 or <2.5 percentile of the distribution from baseline episodes) greater than the number of unloaded episodes above/below baseline by 10% of the total number of loaded episodes. Empty triangles (▵ and ▿): number of loaded episodes above/below baseline greater than the number of unloaded episodes above/below baseline by 5% of the total number of loaded episodes. Columns 6 and 7: In our comparisons of the number of phase b bursts and burst onset times, statistical significnce of the difference between the unloaded and loaded means was assessed by the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test (▵ and ▿, P < 0.05; ▴ and ▾, P < 0.01). In column 7, all burst onset times are specified as the time elapsed between phase boundary and the actual onset time. Each order of burst (Ord.) was compared separately. Upward triangles (▴ and ▵), loaded > unloaded; downward triangles (▾ and ▿), loaded < unloaded. Abbreviations: C, caudal kicks; La, lateral kicks; CLa, caudal–lateral kicks; Rt, rightward jumps; Lt, leftward jumps; Sh, jumps with short jump lengths; Me, jumps with medium jump lengths.

Examples of EMG reconstructions using the extracted synergies and coefficients

The main finding of the previous section—that most synergies extracted were invariant across conditions—anticipate that the EMG changes described previously can be attributed largely to changes in the activation pattern of invariant synergies. We demonstrate this by first examining how the recruitment time course of each synergy contributes to EMG reconstruction in specific examples. In Fig. 7A, selected kick episodes shown in Figs. 4 and 5 are reconstructed using the extracted synergies and their activation coefficients. The original EMG data, filtered and integrated, are shown in thick black lines; they are superimposed onto the reconstruction, decomposed into different colors with each color denoting the contribution of a single synergy in the reconstruction, and matching the color of the synergy's coefficient time course shown below the reconstruction. The labeling of synergies in Fig. 7 (K1 to K8, etc.) also matches that used in Fig. 6. We see in Fig. 7, A1–A3 that the phase a bursts of knee extensors, similar across all three episodes, are explained in each episode as a burst of a single synergy, K2 (magenta). In phase b, the prolonged ST and RA bursts in the loaded example are explained by an increase in the duration of K4 (gray) and the prolonged IP burst, of K5 (green). Similarly, in Fig. 7, A4–A6, decreases in amplitude of the RI and ST bursts in phase a after loading are explained by the decreased activation of a single synergy, K4. In phase b, the prolongation of RA, IP, and SA was attributed by NMF to an increase in the activation duration of K2 and K5; the duration increases of the ST and TA bursts, on the other hand, are explained by changes in K3 and K4. In Fig. 7B we also show reconstruction examples of three jump episodes (frog P) with similar jump directions (−42.9, −41.6, and −37.5°) and jump lengths (1.49×, 1.66×, and 1.62× body length) collected before, during, and after inertial loading, respectively. As in the kick examples, the phase b EMG changes in muscles ST, RA, IP, and SA are accounted for by increases in amplitude and/or duration of synergies J2 (red), J4 (green), and J5 (magenta). These observations show very clearly how complex load-related EMG changes can be described more simply as alterations in the activations of a few synergies and how changes in a single muscle may involve activation changes of more than one synergy (e.g., ST during phase b in Fig. 7, A4–A6).

FIG. 7.

Reconstructing EMGs of kicking (A), jumping (B), and swimming (C) episodes using the extracted muscle synergies and their corresponding activation coefficients. In A, the kick episodes shown are the same as some of the kick examples shown previously in Figs. 4 and 5 (their corresponding figure labels shown in parentheses). The original EMG data (filtered, rectified, and integrated) are shown in thick black lines. Superimposed onto the EMG data are the reconstructed EMGs, decomposed into different colors denoting the contributions of the different synergies to the reconstruction, and matching the colors of the coefficient time traces shown below the reconstruction. The labels of the synergies (K1–K8, J1–J6, and Sw1–Sw7) also match those shown in Fig. 6. As described in results (Examples of EMG reconstructions), the plots here suggest that EMG changes associated with loading can be explained as altered activations of invariant muscle synergies.

Even though we have not focused herein on comparing loaded and unloaded synergy coefficients for cyclic behaviors (i.e., stepping and swimming cycles), for the sake of completeness we show in Fig. 7C an EMG reconstruction example for a swim episode (frog S) comprising five consecutive swimming cycles, demarcated by dotted vertical lines in the figure. In this episode the weight was attached to the calf during the first three cycles, but it accidentally came off during the fourth (marked by a vertical arrow in the figure). Thus both the latter half of the fourth cycle and the fifth cycle were unloaded. We see that on weight detachment, the duration and/or amplitude of RA, IP, BI, SA, and TA all diminished. In the reconstruction, these changes are explained by the shortened bursts of Sw3 (yellow) and Sw6 (green), as well as diminished activation of Sw7 (gray). This immediate change in EMGs on unloading further supports our earlier conclusion that the synergy coefficient modifications we see here likely reflect an immediate adjustment of motor outputs mediated by altered sensory signals.

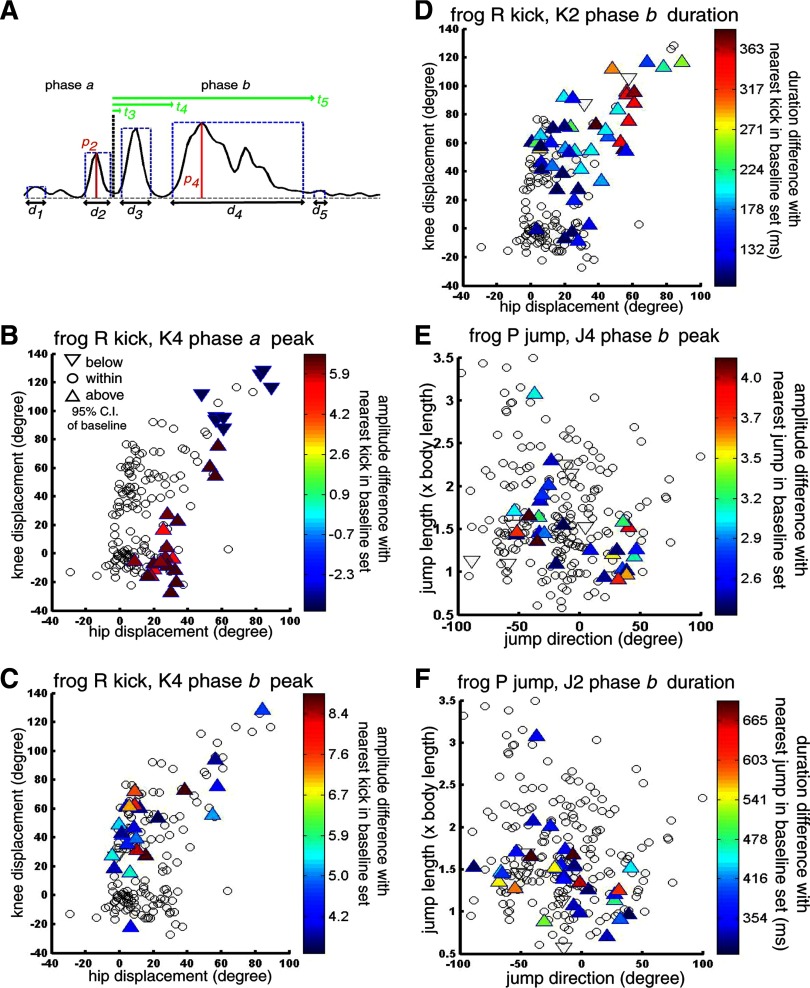

Modulation of synergy activations after loading in selected regions of behavioral space

How loading altered synergy recruitment is demonstrated in the previous section by examining specific EMG examples. To understand how the degree of synergy modulation may be a function of the behavioral variety performed, we proceeded to perform statistics comparing, at the population level, the magnitude and duration of synergy activation of the unloaded and loaded conditions. We focus on comparing the unloaded and loaded EMGs of three of our data sets—kicks of frog R (n = 433), jumps of frog P (n = 419), and jumps of frog Q (n = 412)—because these data sets possess a large enough number of samples to yield meaningful statistical results.

To ensure that any result indicating a difference in coefficient amplitude or duration between the unloaded and loaded behaviors reflects EMG changes for loading compensation rather than those for effecting different behavioral varieties, we sought to compare loaded and unloaded episodes at similar positions in the behavioral space. For every loaded and unloaded episode we calculated the average difference in total duration or peak amplitude between that episode and the five baseline episodes nearest to it in the behavioral space. This way, any loading modulation of duration or amplitude is reflected by different distributions of the loaded and baseline difference values.