Abstract

Bitterness is a distinctive taste sensation, but central coding for this quality remains enigmatic. Although some receptor cells and peripheral fibers are selectively responsive to bitter ligands, central bitter responses are most typical in broadly tuned neurons. Recently we reported more specifically tuned bitter-best cells (B-best) in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NST). Most had glossopharyngeal receptive fields and few projected to the parabrachial nucleus (PBN), suggesting a role in reflexes. To determine their potential contribution to other functions, the present study investigated whether B-best neurons occur further centrally. Responses from 90 PBN neurons were recorded from anesthetized rats. Stimulation with four bitter tastants (quinine, denatonium, propylthiouracil, cycloheximide) and sweet, umami, salty, and sour ligands revealed a substantial proportion of B-best cells (22%). Receptive fields for B-best NST neurons were overwhelmingly foliate in origin, but in PBN, about half received foliate and nasoincisor duct input. Despite convergence, most B-best PBN neurons were as selectively tuned as their medullary counterparts and response profiles were reliable. Regardless of intensity, cycloheximide did not activate broadly tuned acid/sodium (AN) neurons but did elicit robust responses in B-best cells. However, stronger quinine activated AN neurons and concentrated electrolytes stimulated B-best cells, suggesting that B-best neurons might contribute to higher-order functions such as taste quality coding but work in conjunction with other cell types to unambiguously signal bitter-tasting ligands. In this ensemble, B-best neurons would help discriminate sour from bitter stimuli, whereas AN neurons might be more important in differentiating ionic from nonionic bitter stimuli.

INTRODUCTION

Bitter-tasting chemicals comprise a large group of diverse ligands with a distinctive, highly aversive, and inherently avoided quality. Sensitivity to these compounds is generally agreed to have evolved as a protective mechanism because many toxic compounds are bitter, although the reverse relationship is less consistent (Garcia and Hankins 1975; Glendinning 1994, 2007; Grill and Norgren 1978; Spielman et al. 1992; Steiner 1979). The scheme used by the CNS to encode bitterness remains enigmatic due to the mismatch between the potent and specific behavioral effects of bitter ligands and neurophysiological responses to these stimuli, which often appear less robust or selective compared with those elicited by sweet, salty, or sour tastants (see Spector and Travers 2005 for review). Recently, a family of G-protein-coupled taste receptors (T2Rs) that bind bitter compounds has been characterized (Adler et al. 2000), allowing determination of their specificities, expression patterns and signaling pathways (see Behrens et al. 2004; Caicedo and Roper 2001; Mueller et al. 2005; Sugita and Shiba 2005). Taste receptor cells that express T2Rs appear highly specific, i.e., they do not express GPCRs for ligands associated with other qualities. Evidence from alterations of T2R receptors or their downstream components, PLCβ2 and TRPM5, demonstrate a major role for T2Rs in bitter taste (Chandrashekar et al. 2000; Damak et al. 2006; Mueller et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2003). However, recent physiological and behavioral data using PLCβ2- and TRPM5-deficient mice suggest that some bitter tastants exert additional effects independent of this pathway (Damak et al. 2003; Dotson et al. 2005; Hacker et al. 2008). This T2R-independent mechanism appears to share some characteristics with salt and acid transduction, as do the bitter stimuli capable of using it. These stimuli have been termed “ionic” while less easily dissociable bitter stimuli thought to be limited to T2Rs are referred to as “nonionic” (Frank et al. 2004).

T2Rs are most strongly expressed in the circumvallate and foliate papillae, which are supplied by the glossopharyngeal nerve, but are weakly evident in the chorda tympani-nerve-innervated fungiform papillae (Adler et al. 2000; Behrens et al. 2004, 2007). This is consistent with the more robust, specific responsiveness of glossopharyngeal nerve fibers to bitter tastants when compared with chorda tympani fibers (Danilova and Hellekant 2003; Frank 1991). Likewise, we recently reported a novel population of more specifically tuned bitter-best cells (B-best) in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NST) that receive input from the foliate papillae (Geran and Travers 2006). Although many previous studies have demonstrated that bitter tastants also activate NST neurons maximally sensitive to acids and salts (e. g., Di Lorenzo 2000; Giza and Scott 1991; Ogawa and Hayama 1984; reviewed in Spector and Travers 2005), such sensitivity is most prevalent with ionic bitters (Lemon and Smith 2005) in neurons with chorda tympani nerve receptive fields (Geran and Travers 2006) and therefore unlikely to be entirely dependent on T2Rs.

The relatively specific responses of B-best, foliate-responsive NST neurons to both ionic and nonionic bitter tastants imply that such cells play a key role in coding bitterness, perhaps even comprising a sparse code/labeled-line for conveying this quality. However, because most of the B-best cells could not be antidromically activated from the parabrachial nucleus (PBN) (Geran and Travers 2006), it is possible that such neurons mainly contact local medullary circuits, consistent with studies implicating the glossopharyngeal nerve in reflex function (Grill et al. 1992; Spector and Travers 2005; Travers et al. 1987). Furthermore, the response characteristics of these B-best neurons have not been thoroughly characterized. Recent reports have highlighted the inherent variability in gustatory response profiles (Chen and Di Lorenzo 2008; Di Lorenzo and Victor 2003; Roussin et al. 2008), making it possible that B-best neurons would not be as obvious nor as reliable on repeated testing. Furthermore, our previous work used only single concentrations of each stimulus, raising the critical question of how B-best tuning curves are affected by intensity. The current study adapted techniques that allowed identification of B-best NST cells to recording from the PBN to determine whether bitter-responsive neurons with similar selectivity could be observed at a higher level of the ascending taste pathway. In addition, the specificity of bitter-responsive neurons was challenged for reliability across repeated trials and with a wider range of stimulus intensities.

METHODS

Subjects

Data were collected from 79 adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan) weighing 250–500 g. All procedures were performed in accordance with the Institutional Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee (ILACUC) at the Ohio State University.

Surgery

Animals were deeply anesthetized with thiobutabarbital sodium (100 mg/kg) and maintained at this level using supplemental doses of sodium pentobarbital (0.5–1.5 mg). Body temperature was kept at ∼37°C using a heating pad and telethermometer, and the superior laryngeal and hypoglossal nerves were transected bilaterally to limit oromotor reflexes during testing. The trachea was dissected posterior to the larynx, and a length of polyethylene tubing inserted to aid respiration. A suture was placed anterior to the foliate papillae so that the folds containing taste buds could be stretched open manually, improving access to this region (see Frank 1991; Halsell et al. 1993).

A hole was drilled just anterior and lateral to lambda, and a microelectrode (0.2–1.0 MΩ, Frederick Haer) was inserted 0.2 mm rostral and 1.8 mm lateral to lambda. The electrode was driven at a 20° angle (tip pointed posteriorly) for ∼6–7 mm while observing multiunit neural responses with an oscilloscope and audio monitor. Tracks were made in this general vicinity until the gustatory PBN was located electrophysiologically. This area was identified by applying the search mixture to the oral cavity and observing a noticeable increase in activity over a distance of ∼0.5 mm in the axis. The dorsoventral electrode was then replaced with one with a higher impedance (2–4 MΩ, WPI) to record from single units. Once isolated, a series of taste solutions were tested, receptive field was defined, and a small electrolytic lesion was made to mark the area on completion of testing. At the conclusion of the experiment, each animal was perfused and the brain extracted and stored in phosphate buffered 20% sucrose -formalin. Brains were cut on a freezing microtome in two series of 52-μm sections and alternately stained with Weil and cresyl violet. Sections were inspected using a light microscope (Nikon E600) and digital photomicrographs taken of sections containing lesions and/or electrode tracks (Nikon DXM 1200, Act II software). The locations of the lesions were plotted using a series of standard sections depicting PBN borders and subnuclei (see Halsell and Travers 1997).

Data collection and analysis

As in our previous work, the search mixture consisted of one representative of each of the five putative taste qualities (“sour,” 10 mM HCl; “salty,” 100 mM NaCl; “bitter,” 3 mM quinine HCl; “sweet,” 20 mM Na saccharin; and “umami,” 30 mM monopotassium glutamate +3 mM inosine monophosphate) (Geran and Travers 2006). Once a unit was isolated, the mixture and the other 12 test stimuli (see following text) were delivered at a rate of ∼2 ml/s via a pressurized flow system controlled by Spike 2 software and hardware (Cambridge Electronic Design). Each test sequence was as follows; no stimulation, distilled water, and taste stimulus, for 10 s each, a 20-s distilled water rinse, and another 10 s without stimulation. Each phase of the test sequence began as the previous one ended so that the flow was continuous. The intertrial interval period was ∼1 min. Test stimuli included two representatives of four putative taste qualities, plus four representatives for bitterness. These were salty, 100 mM NaCl and 100 mM sodium gluconate; sweet, 300 mM sucrose and 300 mM glycine; sour, 10 mM HCl and 30 mM citric acid; umami, 30 mM monosodium glutamate (MSG) + 3 mM inosine monophosphate (IMP) and 30 mM monopotassium glutatmate (MPG) + 3 mM IMP; and bitter, 3 mM quinine HCl, 10 mM denatonium benzoate, 7 mM propylthiouracil (PROP), and 10 μM cycloheximide. When possible, each stimulus was tested twice to determine response reliability. Receptive fields were also assessed as in the previous paper (Geran and Travers 2006) by stroking a brush dipped in the search mixture across each of four main receptor subpopulations, the anterior tongue and nasoincisor ducts located in the anterior oral cavity and the foliate papillae and soft palate located in the posterior oral cavity. The circumvallate papilla was not tested because our previous experience suggested that this method of stimulation is inadequate for activating taste receptors in this region. A receptor subpopulation was considered to elicit a response if the search mixture application elicited a clear audible and visual increase in firing rate compared with stimulation using a brush dipped in distilled water. For most analyses, receptive field classifications were simplified by dividing neurons into those that responded to anterior mouth stimulation, posterior mouth stimulation, or both. A concentration series was also tested when time permitted. Stimuli were chosen with a focus on ascertaining how breadth of tuning of bitter-best (B-best) and AN neurons changed across a range of salty, sour, and bitter stimuli since other studies have reported neurons robustly responsive to all three qualities (Di Lorenzo 2000; Giza and Scott 1991; Lemon and Smith 2005; Ogawa and Hayama 1984). Thus three concentrations of four stimuli (3, 10, and 30 mM quinine; 3, 10, and 30 mM HCl; 10, 100, and 300 mM NaCl, and 3, 10, and 30 μM cycloheximide), were used. The middle concentration was equivalent to the test series concentrations with the exception of quinine where the test concentration was lowest due to its relatively weak effectiveness compared with other stimuli. The other concentrations were one-third the strength and three times the strength of the test stimulus (or 3 times and 10 times the test stimulus for quinine).

Responses to individual stimuli were quantified as the number of spikes in the 10-s stimulation period minus those during the preceding 10-s water stimulation period. A significant response was defined as one where the net number of spikes was ≥10 (i.e., 1 per second) and also more than or equal to the SD for water responses across all trials (Geran and Travers 2006; Nishijo et al. 1991). When stimuli were tested more than once, the mean was used for analysis. Mean spontaneous and water response rates across trials were also calculated for each neuron. Statistics were performed using Systat 12 (SPSS), including ANOVAs, t-test, and Pearson's correlations. Significance was set at P ≤ 0.05 for each. Data are presented as means ± SE. Similarities between response profiles were defined as the Pearson correlation coefficient across the 12 test stimuli, and neurons subsequently divided into groups using hierarchical cluster analysis with an average amalgamation schedule. To examine relationships in the population responses to different stimuli, across-neuron correlations were performed and graphically depicted using multidimensional scaling. Entropy (H) values across the five taste qualities were calculated for individual neurons as described in the previous paper (Geran and Travers 2006). Entropies for bitter stimuli were also calculated for B-best units to determine whether these cells responded to all four bitters tested or to only a subset. A constant (i.e., K value) of 1.66 was used for this measure. For those neurons tested twice (n = 35), the reliability of the relative responsiveness of a given neuron to the 12 stimuli was quantified using Pearson's r for responses across the first and second trials. In addition, to assess the reliability of firing rates, we calculated the coefficient of variation (CV) for significant responses for each neuron and derived the average CV value for that cell. The time course of each significant taste response was also analyzed (n = 325). For this analysis, onset and offset latencies and time to peak response were calculated from poststimulus time histograms with a bin size of 0.5 s. Onset latency was defined as the first bin following the application of the taste solution where the firing rate exceeded the preceding water baseline by 2.5 SD units. Time to peak was the bin where the response was highest (or midpoint of the peak if it extended over more than one bin). Offset latency was measured as the first bin where the response returned to baseline.

RESULTS

General characteristics

Gustatory responses were recorded from 90 PBN neurons. With one exception (1 stimulus omitted in a single case), all 12 tastants were tested for each cell and the receptive field assessed for most (n = 78). Across all 90 neurons, the mean spontaneous rate was 3.8 ± 0.4 spike/s, a significant increase over that in NST (2.1 ± 0.3 spike/s, P < 0.001 (Geran and Travers 2006). The average response for the best stimulus across cells was significantly higher in PBN than NST (27.3 ± 2.4 vs. 15.7 + 1.4 spike/s, t-test, P < 0.001). However, the overall entropy for PBN cells was 0.57 ± 0.03, not significantly different from the medulla (mean = 0.59 ± 0.02, P > 0.39). A majority of cells (n = 44, 56.4%) had receptive fields restricted to the anterior oral cavity (anterior tongue and/or nasoincisor ducts). However, a substantial number had receptive fields restricted to the posterior mouth (foliate papillae and/or soft palate; n = 14, 17.9%). The remaining neurons responded to both anterior and posterior stimulation (n = 20; 25.6%), usually the foliate papillae and nasoincisor ducts. Notably, the percentage of neurons exhibiting both anterior and posterior receptive fields (RFs) was nearly 10 times as great as in NST (3/118, 2.5%, P < 0.001, χ2). The proportion of neurons with some portion of their RF located posteriorly was also greater in PBN than NST (P < 0.03, χ2).

Cell types: are there bitter-selective neurons in PBN?

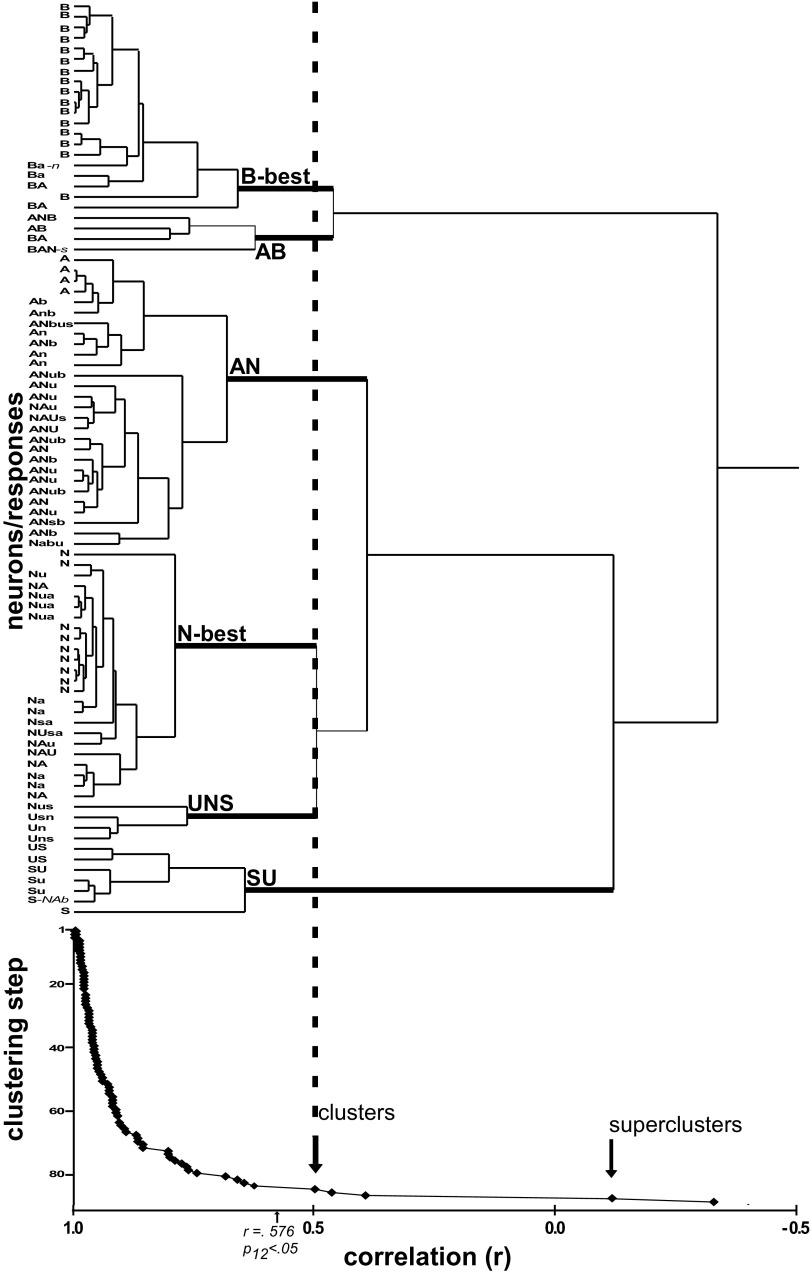

The responses of 90 neurons were subjected to hierarchical cluster analysis using similarities between chemosensitive profiles defined by Pearson correlations across responses to the 12 test stimuli. Initial analysis identified three individual cells (3.3% of the population) that appeared to be outliers because they were amalgamated only at a correlation below that indicating statistical significance (r = +0.58, n = 12 stimuli). For clarity, these cells were removed and the clustering process repeated. The resulting scree plot and cluster tree revealed three large groups: one optimally responsive to bitters or bitters and acids, a second to electrolytes, and a third most responsive to sucrose and amino acids (Fig. 1). These “superclusters” were distinct but contained very heterogeneous cells. For example, the electrolyte supercluster amalgamated at r = +0.398. However, when clusters were defined based on the next breakpoint, six more homogeneous groups, each amalgamated at statistically significant correlations, could be identified. Figure 2 shows mean response profiles for these six groups.

FIG. 1.

Cluster tree (top) and scree plot (bottom) for 87 parabrachial nucleus (PBN) neurons. The arrows (scree plot) indicate 2 major breakpoints in the clustering process, corresponding to the division of the population into 3 “superclusters” then further into clusters (also denoted by a dashed line extending to the cluster tree): the 6 clusters included bitter-best (B-best), acid/bitter (AB), acid/salt (AN), salt-best (N-best), umami/salt/sweet (UNS), and sweet/umami (SU). The taste qualities that elicited a significant response ≥25% of the maximum response are listed for each neuron; capital letters denote a response ≥50% of the maximum. With the exception of umami, a quality is listed if any stimulus of that quality elicited a response, but for umami, both monosodium glutamate (MSG) and monopotassium glutatmate (MPG) responses were required because most N-best cells responded to MSG but not MPG, implying that the sodium ion was the effective stimulus. A = sour [HCl or citric acid], B = bitter [quinine, cycloheximide, PROP, denatonium, or quinine], N = salty (NaCl or sodium gluconate), S = sweet (sucrose or glycine), U = umami (MSG and MPG).

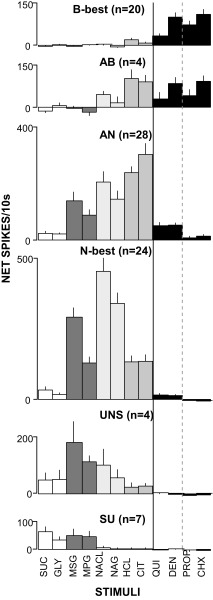

FIG. 2.

Mean net responses (±SE) across taste stimuli for each of the 6 clusters. A solid line, separates the bitter and nonbitter stimuli; a dashed line, ionic vs. nonionic bitter tastants. Sweet: sucrose (suc) and glycine (GLY). Umami: MSG and MPG. Salty: NaCl and Na gluconate (NAG). Sour: HCl and citric acid (CIT). Bitter: quinine (QUI), denatonium (DEN), propylthiouracil (PROP), and cycloheximide (CHX).

Similar to NST, one group (“B-best” neurons) exhibited a high degree of selectivity for bitter tastants at the test concentrations. The average breadth of tuning (H) for these neurons was only 0.245 ± 0.043, lower than any other group, although this difference only approached significance (P < 0.08, ANOVA). On average, B-best neurons responded 5.7 times better to cycloheximide, nominally the most effective bitter stimulus, than to HCl, the most effective nonbitter stimulus. The specificity suggested by the average data were readily apparent for individual cells; 16/20 B-best neurons responded at least four times more vigorously to one or more bitter tastants than to any other quality; in fact 10 of these cells responded significantly only to bitter stimuli. Thus the selectivity of PBN B-best neurons for bitter versus other tastants was similar to NST, [H = 0.33 ± 0.18 (NST) vs. 0.25 ± 0.19 (PBN), P > 0.23, t-test]. There was, however, a tendency for B-best neurons to be more broadly responsive across bitter stimuli. Bitter entropy was nominally, although not significantly, higher in PBN (0.87 ± 0.03 vs. 0.75 ± 0.05, respectively, P = 0.051, t-test). Further, in NST a small number of neurons exhibited selective responses to denatonium but such neurons were not observed in PBN. On the other hand, even though the four bitter tastants were matched for behavioral effectiveness, quinine elicited smaller responses than the other bitters, just as in NST (quinine mean = 33.5 vs. 98.9 to 109.3 for other bitters, Ps < 0.001, t-test).

It was also important to examine whether other neuron types exhibited minimal bitter responsiveness, as found in the medulla. Indeed, three groups, including cells optimally responsive to sucrose and glutamate (SU), sodium (N-best), and a small set of cells (UNS) with intermediate characteristics, had miniscule average responses to any bitter stimulus. However, neurons optimally responsive to salts and acids (AN) did exhibit some responsiveness to bitter tastants, mainly the ionic bitter stimuli, quinine and denatonium. Although the entropy measure suggested that AN PBN neurons were no more broadly tuned across all qualities than their medullary counterparts (P > 0.09, t-test), average profiles suggested a somewhat higher bitter:sour ratio in PBN. For example, in NST, the quinine: citric acid ratio was 0.03; in the PBN, it rose to 0.17 (P < 0.005). Despite this increase in sideband responsiveness to ionic bitter stimuli, responses to the nonionic bitter tastants remained negligible in the AN group. The cluster analysis, however, identified another group of neurons (AB) with characteristics intermediate between the B and AN clusters. This AB group contained many fewer cells than either the AN or B groups but responded nearly equivalently to citric acid, HCl, denatonium, and cycloheximide. In sum, segregation of bitter sensitivity is maintained in PBN in most of the population but there is evidence for a subset of cells that integrates the bitter and sour qualities.

Additional features distinguish B-best neurons

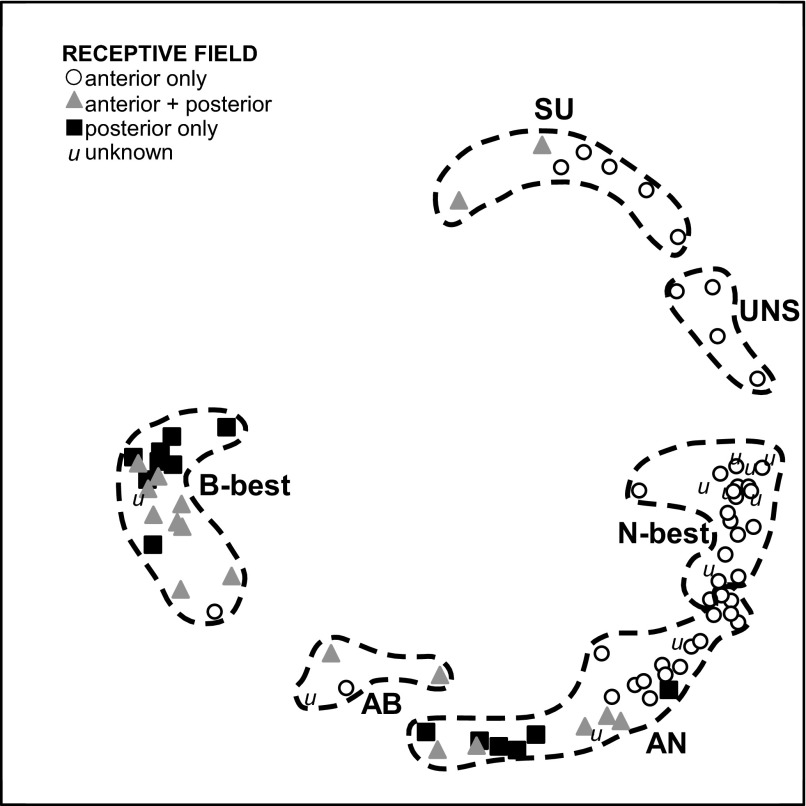

Distinctions between groups based on gustatory sensitivity were reinforced by differences in RF, spontaneous rate, responses to water, and time course. Figure 3 is a multidimensional scaling plot of the 87 clustered neurons with shaded symbols coding for different RFs. The six chemosensitive groups are denoted by dotted lines. There was a strong relationship between chemosensitive group and RF (χ2 P < 0.001). The SU and UNS neurons usually had RFs restricted to the anterior oral cavity and were separated in the multidimensional scaling space from other cell types. In addition, although N-best and AN neurons formed a virtual continuum, each N-best neuron only had input from the anterior mouth, usually the anterior tongue, but nearly half of the AN neurons had mixed or exclusively posterior RFs. Interestingly, those with mixed or posterior RFs were located closer to the AB and B-best neurons than those with purely anterior RFs, implying a systematic variation in chemosensitivity. Indeed, AN neurons with mixed or posterior RFs responded more specifically to acid than those with purely anterior RFs as reflected in average citric acid: NaCl ratios of 4.9 versus 1.2 for the two groups (P = 0.01, t-test). The B-best neurons were the most clearly segregated group in the multidimensional scaling space and all but one had a RF that included some portion of the posterior oral cavity. In contrast to the NST where the vast majority of B-best cells had RFs restricted to the posterior mouth, just over half of the PBN B-best neurons received input from both the anterior and posterior oral cavity, usually the foliates and nasoincisor ducts. An example of foliate/nasoincisor duct convergence is shown in Fig. 4.

FIG. 3.

Multidimensional scaling of individual neurons coded according to receptive field (RF), with clusters delineated by dotted lines. Note that B, AN, and, to a lesser extent, the SU and AB clusters contain neurons with posterior or mixed RFs while the N-best and UNS groups are exclusively anterior.

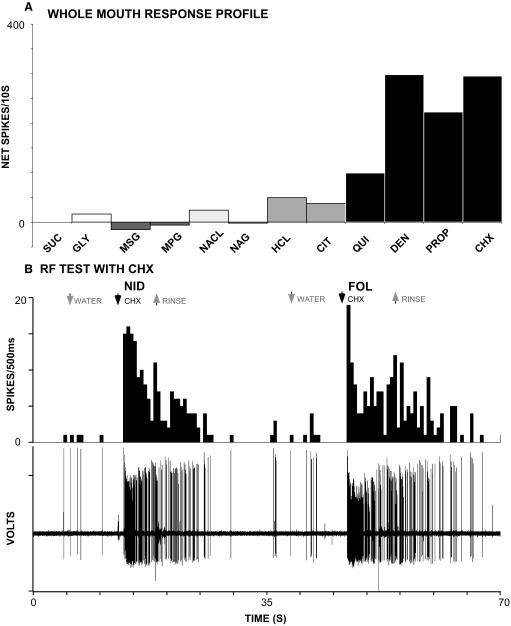

FIG. 4.

Responses of a B-best neuron that received input from both the anterior and posterior oral cavity. A: response profile obtained using whole-mouth stimulation. This neuron responded quite specifically to bitter stimuli, most vigorously to CHX and DEN. B: poststimulus histograms and single-unit records demonstrating that robust responses to the nonionic bitter tastant, CHX, were elicited when either the nasoincisor ducts (NID) or foliate papillae (FOL) were stimulated. No responses were observed when the anterior tongue or soft palate were tested, either with CHX or the taste mixture (not shown). Stimulus abbreviations as in Fig. 2.

Spontaneous rates and responsiveness to the pretastant water flow also varied among groups (Table 1, Ps < 0.001 ANOVA). B-best had the slowest average spontaneous rates (6.5/10s) and N-best had the fastest (64.5/10s), a 10-fold difference. Post hoc LSD tests specified differences for B-best and SU neurons relative to the N-best and AN cells and for UNS neurons compared with N-best cells (P's < 0.05). Variations in neural activity during the prestimulus water period generally mirrored differences in spontaneous rate. In addition, B-best cells doubled their firing rates in response to water application (P < 0.05, t-test), whereas N-best cells exhibited a small but highly significant decrement in response to water (P < 0.001, t-test).

TABLE 1.

Spontaneous rates and water responses*

| GROUP | SPONTANEOUS | WATER |

|---|---|---|

| SU | 9.5 ± 6.11 | 10.4 ± 6.11 |

| UNS | 23.3 ± 9.29 | 20.1 ± 7.80 |

| N-best | 64.8 ± 9.28 | 55.5 ± 8.56 |

| AN | 48.1 ± 8.37 | 50.8 ± 7.55 |

| AB | 41.8 ± 15.44 | 71.0 ± 27.86 |

| B-best | 6.5 ± 3.26 | 14.0 ± 5.92 |

SU, sweet/umami; UNS, umami/salt/sweet; N-best, salt best; AN, acid/salt; AB, acid/bitter; B-best, bitter best.

spikes/10 s.

The onset latencies of taste responses also differed significantly across neuron types (P < 0.001, ANOVA). B-best neurons had longer latencies than any other cell type except the AB group. SU and AB neurons had longer latencies than the N-best and AN neurons (P < 0.02 for each, Tukey's). Times to peak showed similar tendencies (P < 0.001, ANOVA). B-best neurons achieved their maximum firing rate most slowly, whereas N and AN neuron responses peaked most rapidly (range for all cells = 2.4–5.8 s, P < .001; B-best > AN, N, UNS; AN < B-best, SU, N-best < B-best, AB, SU; P < 0.02 for each, Tukeys). Latency and time to peak also were significantly different as a function of RF (P's <.001, ANOVAs) with anterior < mixed < posterior for both measures (P's <.01, Tukeys). Offset latencies did not vary for chemosensitive neuron type or RF.

Challenge to bitter selectivity

RELIABILITY.

To assess whether B-best neurons were identifiable across repeated testing, 35 cells were tested twice with all 12 stimuli, including 1 SU, 6 N-best, 16 AN, and 12 B-best neurons. Neurons were more active during the second trial, as evident in small but significant increases for mean spontaneous rate (32.2 vs. 39.7, paired t-test P < 0.001), as well as water (37.9 vs. 44.8, P < 0.004) and mixture responses (197.1–241.3, P < 0.001) on the second trial. Nevertheless, normalized response profiles for individual cells (Fig. 5) suggest considerable reliability for relative responsiveness across repeated testing. Responses correlated highly across trials (mean r = 0.93 ± 0.01), with over 90% exhibiting r-values exceeding +0.85. On the other hand, the mean CV across trials was 0.29 ± 0.03, implying more variability in absolute firing rates. Consistent with previous studies (Di Lorenzo and Victor 2003; Roussin et al. 2008), neurons with higher firing rates were more stable. There was a positive correlation between the r value across trials and the maximal firing rate (r = +0.43, P = 0.01) and a negative correlation between firing rate and the CV (r = −0.60, P < 0.001). Indeed, as expected based on their lower firing rates (see Fig. 2), B-best neurons did exhibit greater variability, including significantly lower across-trial correlations and higher CVs than N-best or AN neurons (P < 0.005 ANOVAs, Ps < 0.05 LSD for both r's and CVs). This difference was most pronounced for the CV, a measure that reflects absolute firing rates (B-best = 0.43 ± 0.07, AN = 0.22 ± 0.33, N-best = 0.2 ± 0.04) but less evident for correlations, which are more dependent on relative response profiles (B-best = +0.87 ± 0.03, AN = 0.95 ± 0.01, n = 0.99 ± 0.004). Indeed, despite this greater across-trial variability, the distinctiveness of B-best neurons was unambiguous across replications. Separate cluster analyses indicated that neurons were grouped very similarly on trials 1 and 2, including 11/12 B-best neurons which segregated identically. Consistent with the stability of the cluster solution, the best-quality for a given neuron only switched on three occasions (9%); one neuron in the B-best cluster responded better to HCl on the first trial and cycloheximide on the second, and two very broadly tuned AN neurons switched between the salty and sour qualities (starred cells in Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Proportional responses for cells that were tested twice. Neurons in different rows are from different clusters. Replications for a given cell are separated from other cells by a larger space. Responses to qualities are color-coded (blue: bitters, yellow: salts, orange: acids, pink: sweeteners, purple: glutamates). Lines separate responses to the 4 bitter stimuli and 2 representatives of each of the other qualities. Note the similarity in the amount of the total response devoted to each taste quality across trials. Three cells (marked with asterisks) changed best stimulus category from 1 trial to the next. The single SU unit is outlined in purple to distinguish it from the N-best units.

CONCENTRATION.

Twenty-six cells including 7 B-best, 12 AN, 3 N-best, and 4 SU neurons were tested with 3-fold higher and lower concentrations of NaCl, HCl, and cycloheximide and 3- and 10-fold higher concentrations of quinine. These concentrations captured a dynamic behavioral (Chan et al. 2004; Coldwell and Tordoff 1996; Geran and Travers 2006; Scott and Giza 1987) as well as neurophysiological range for each stimulus with the latter evident in the positive relationships between stimulus intensity and firing rate in Fig. 6. To determine the extent to which B-best cells could unambiguously signal the presence of bitter-tasting ligands, it was critical to determine how their selectivity changed over a range of stimulus intensities. A repeated-measures ANOVA for B-best cells demonstrated main effects for stimulus (P < 0.005), concentration (P < 0.001) and an interaction (P = 0.01). The most concentrated bitter stimuli produced larger responses than any salt or acid concentration (Fig. 6, Table 2, top). In addition, even the most intense NaCl and HCl failed to produce responses that exceeded those elicited by the bitter stimuli. On the other hand, in certain instances, bitter and nonbitter tastants could elicit comparable responses. For example, 0.3 M NaCl provoked responses that rivaled those elicited by 3 or 10 mM quinine and even the weakest NaCl or HCl were as effective as 3 μM cycloheximide.

FIG. 6.

Mean concentration-response functions for each cluster. The test concentration (marked with an arrow) refers to that used during the 12-stimulus test session (i.e., 100 mM NaCl, 10 μM HCl, 3 mM QUI, and 10 μM CHX). Note that responses to the 4 stimuli do not change across concentration for the SU units or for CHX in any cell type other than B-best. Likewise, N-best units showed only a minimal increase in responding to high concentrations of HCl and quinine. The remaining cluster types and stimuli showed some degree of overlap, indicating that B-best units were not entirely specific for bitter stimuli across concentrations. Stimulus abbreviations as in Fig. 2.

TABLE 2.

Paired comparisons, concentration series

| Stimulus | 3 mM Q | 10 mM Q | 30 mM Q | 3 μM CHX | 10 μm CHX | 30 μm CHX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-best neurons | ||||||

| 30 mM N | Q | Q | Q | — | CHX | CHX |

| 100 mM N | Q | Q | Q | — | CHX | CHX |

| 300 mM N | — | — | Q | — | CHX | CHX |

| 3 mM H | Q | Q | Q | — | CHX | CHX |

| 1 mM H | Q | Q | Q | — | CHX | CHX |

| 30 mM H | — | — | Q | — | — | CHX |

| AN neurons | ||||||

| 30 mM N | — | Q | Q | N | N | — |

| 100 mM N | N | N | — | N | N | N |

| 300 mM N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 3 mM H | H | — | Q | H | H | H |

| 1 mM H | H | H | — | H | H | H |

| 30 mM H | H | H | H | H | H | H |

Results of paired t-tests between different concentrations of NaCl (N), HCl (H), quinine (Q), and cycloheximide (CHX) for B-best (top) and AN neurons (bottom). Letters indicate the stimulus that elicited a significantly larger response (P ≤ .05); dashes (—) denote no significant difference between the two stimuli.

Similar to B-best neurons, AN cells were less selectively tuned to salt and acid when challenged with more concentrated quinine (Fig. 6, Table 2, bottom). A repeated-measures ANOVA demonstrated main effects for stimulus (P < 0.001), concentration (P < 0.001) and an interaction (P < 0.001). When presented at the test concentration (3 mM), quinine elicited smaller responses than any level of HCl and all but the weakest NaCl. However, raising the quinine concentration to 10 mM yielded a significantly larger response than 30 mM NaCl. Tripling the quinine concentration again produced responses that were larger or comparable to all but the most intense nonbitter stimuli. In contrast, cycloheximide produced a much different result. At the highest concentration, 30 μM, cycloheximide remained less effective than any level of HCl and all but the weakest NaCl. Furthermore, the strongest cycloheximide was significantly, albeit slightly, less effective than even the weakest quinine, further emphasizing the differential effectiveness of these two bitter stimuli for AN neurons.

Smaller numbers of N-best and SU neurons were tested with the concentration series, precluding statistical analysis. Even so, it was readily apparent that these cells were minimally sensitive to both bitter tastants even at higher concentrations. Indeed the N-best neurons retained considerable specificity for NaCl relative to HCl even when the acid concentration was tripled. Similarly, SU neurons remained weakly responsive to both salt and acid at the highest concentrations tested.

Contribution of B-best and AN neurons to coding bitterness

Across-neuron correlations between each stimulus pair were calculated and relationships among tastants depicted using multidimensional scaling. We compared the impact of B-best versus AN neurons in coding bitterness by scrutinizing the multidimensional scaling space when the entire population of PBN neurons was included in the analysis and without each of these groups (Fig. 7; Table 3). With all PBN neurons, the bitter stimuli, except quinine, comprised a distinct cluster segregated from the other stimuli. As in our previous NST study (Geran and Travers 2006), however, 3 mM quinine was midway between the other bitters and the acids. Indeed, at higher concentrations, quinine was much more closely allied with the acids, For example, 30 mM quinine correlated +0.68 to +0.86 with the acids, but only +0.12 to +0.46 with the nonquinine bitters. Like quinine, the other ionic stimulus, denatonium, was closer to the acids than the nonionic bitter stimuli, but overall most closely allied with the nonquinine bitters.

FIG. 7.

Across-neuron correlations between stimuli, including the concentration series, depicted in multidimensional scaling plots. The different panels calculated across-neuron correlations using different populations of neurons. A: all neurons; B: all except the B-best cells. C: all neurons except the AN cells (bottom). Differences in concentration are illustrated by the size of the circle (small, lower than the test concentration; middle, test concentration; large, higher than the test concentration). Stimulus qualities are represented by different colors (pink, sweet; purple, umami; yellow, salt; orange, sour; blue, bitter; light blue, QUI). Note that similar qualities cluster together when all cells are included in the analysis (top). QUI is represented as more similar to acids than bitters. When the B-best units are removed (middle), the bitter stimuli spread apart more. When the AN units are removed (bottom), the bitters including QUI, form a more cohesive group. Stimulus abbreviations as in Fig. 2.

TABLE 3.

Average changes in correlations without B-best or AN neurons

| No B-best | No AN | |

|---|---|---|

| Sour | −0.03 | −0.10 |

| Sour-QUI | +0.11 | −0.28 |

| Sour-bitter (not QUI) | +0.38 | +0.03 |

| QUI | +0.01 | +0.04 |

| QUI & other bitters | +0.01 | +0.33 |

| Non-QUI bitters | −0.41 | 0.05 |

QUI, quinine.

Although both B-best and AN neurons responded to bitter tastants, the absence of one or the other group had distinct effects on the interstimulus correlations and resulting multidimensional scaling solution. When B-best neurons were removed, most of the nonquinine bitters remained segregated from the other tastants. However, on average, the correlation among them dropped by 0.41 (Table 3), causing these stimuli to become more dispersed in the multidimensional scaling plot (Fig. 7). For example, the correlation between the test concentration of cycloheximide (10 μM) and denatonium dropped from +0.79 to +0.52. In fact, the weakest cycloheximide (3 μM) entirely lost its alliance with the other bitter chemicals. Quinine remained close to the acids, but the positions of quinine and the acids shifted in the multidimensional scaling plot, reflecting the fact that the other bitter stimuli were more highly correlated with acids in the absence of B-best neurons. In fact, on average, the correlation between the nonquinine bitters and acids rose by 0.38, although these two classes of ligands were still weakly correlated. In contrast, when AN neurons were removed, the nonquinine bitters retained their high intercorrelations. Furthermore, quinine became more correlated with the other bitters and less correlated with the acids producing a clearer segregation between sour and bitter chemicals.

Histology

There was no clear evidence of chemotopy or orotopy in the PBN (Fig. 8). Neurons from each cluster and RF were found in the waist region of the nucleus. This region was defined as the ventrolateral and centromedial subnuclei as well as the cell bridges in the brachium between these areas (see Fulwiler and Saper 1984; Norgren and Leonard 1973). Cells from each cluster, with the exception of SU, were also found in the lateral half of the nucleus including the external lateral and external medial subnuclei (see Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Approximate locations of 52 recorded parabrachial units collapsed onto 3 representative sections (A-C, rostral–caudal). Cells are coded according to both cluster (pink, SU; blue, B-best; yellow, N-best; red, AB; purple, UNS; orange, AN) and receptive field (circle, anterior; diamond, mixed; square, posterior; outline, unknown).

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that a population of taste-responsive neurons in the PBN has relatively narrow tuning to bitter ligands when a range of qualitatively distinct stimuli is presented at moderate concentrations. Moreover, there is dissociation between ionic and nonionic bitter tastants. Similar B-best neurons were found previously in NST and hypothesized to contribute to taste quality and/or palatability coding in addition to oral reflex function (Geran and Travers 2006). The existence of analogous neurons in the pons lends support to this hypothesis and suggests B-best cells might exist at even higher levels of the neuraxis. Despite convergence between the medulla and pons, PBN B-best neurons were as specifically tuned as in NST and remained so across repeated trials. Systematic testing of multiple concentrations, however, showed that pontine B-best neurons also responded to more intense salt and acid stimuli, tempering their specificity. Although this indicates that these cells are unlikely to comprise a labeled-line for bitterness, the data also demonstrate that B-best neurons play a dominant role in coding this quality. Furthermore, B-best neurons make up the vast majority of cells responsive to nonionic bitter tastants, like cycloheximide.

PBN versus NST comparison: general aspects

Compared with our previous NST study (Geran and Travers 2006), spontaneous and stimulus response rates were significantly higher in the pons. This is in agreement with several earlier reports comparing the two nuclei (Di Lorenzo and Monroe 1997; Nakamura and Norgren 1991; Nishijo and Norgren 1991; Van Buskirk and Smith 1981) but see (Perrotto and Scott 1976). The amplification of firing rates at the second-order relay has been interpreted as indicative of convergence from NST to PBN (Van Buskirk and Smith 1981). Indeed the proportion of PBN neurons receiving input from receptor subpopulations in both the anterior and posterior oral cavity showed a 10-fold increase relative to NST. A previous report provided similar evidence for RF convergence, but it was not as dramatic (Halsell and Travers 1997) possibly because the earlier study only included quinine as the representative bitter stimulus; i.e., many B-best anterior-posterior neurons in the present study responded much better to bitter tastants other than quinine. Despite this convergence, the entropy values (i.e., breadth of tuning) across the five putative taste qualities did not increase significantly compared with NST. Instead, with an intriguing exception, relative response profiles, particularly with regard to bitter responsiveness, remained similar.

Neuron types and specificity of bitter responsiveness

A hierarchical cluster analysis suggested six neuron groups. Three groups responded primarily to preferred tastants: those optimally responsive to sodium (N-best) or sweet and umami stimuli (SU, UNS) and exhibited negligible responses to all four bitter chemicals. In contrast, neurons broadly tuned to sodium and acid (AN) also had small responses to the ionic bitters: quinine and denatonium (see Fig. 2). The comparative lack of bitter responsiveness among these neuron clusters strongly resembled their counterparts in NST (Geran and Travers 2006). The responsiveness of AN cells to ionic bitters is also in agreement with many previous reports of quinine activation in similar cells in the periphery and brain stem (e.g., Di Lorenzo 2000; Frank et al. 1983; Giza and Scott 1991; Ogawa and Hayama 1984; Ogawa et al. 1973; reviewed in Spector and Travers (2005) as well as a recent NST study that used an extensive array of ionic bitter stimuli (Lemon and Smith 2005). In contrast to NST, however, there was a small group of “AB” PBN neurons that responded more equivalently to acids and bitter tastants than AN neurons. These cells appear to represent another instance of convergence because bitter responsiveness included the nonionic bitter stimuli, especially cycloheximide, a tastant highly specific for medullary bitter-best neurons (Geran and Travers 2006). Nevertheless these broadly tuned sour/bitter cells were greatly outnumbered by PBN bitter-selective neurons as found in NST (Geran and Travers 2006). These data extend previous evidence of a neural pathway maximally responsive to stimuli described as bitter. For instance, receptors for bitter tastants appear segregated in a subset of Type II taste bud cells (Zhang et al. 2003) that respond best to bitters (Tomchik et al. 2007; Yoshida et al. 2006) and may be directly innervated by gustatory fibers, although convergence onto Type III cells also occurs (Tomchik et al. 2007). Bitter specificity can also be seen in IXth nerve gustatory fibers (Frank 1991; Hellekant et al. 1997; Ninomiya 1998; Yoshida et al. 2006) and neurons of the NST (Geran and Travers 2006) and PBN. In fact, a larger proportion of cells were B-best in PBN than in the medulla. Although the relative responsiveness of these neurons to bitter versus other qualities was comparable to NST, B-best PBN neurons responded more equivalently across bitter stimuli. Furthermore, only one bitter-selective cluster was evident in PBN, but there were two groups in NST: one selective for denatonium and one more broadly tuned to bitter tastants. These data suggest yet another type of integration in PBN; i.e., within the bitter quality. It should be noted, however, that the denatonium-specific NST cluster was quite small (n = 3), and it is possible that such units exist in PBN but were not identified. In the NST, bitter-responsive units were more difficult to locate and/or less responsive to quinine in the mixture, so denatonium was applied periodically as a search stimulus. In PBN, cells were more responsive to quinine, and denatonium was seldom used alone.

Similar to NST, most B-best neurons had RFs that included the posterior oral cavity, usually the foliate papillae. In fact, just a single B-best, nasoincisor duct-responsive neuron had a RF restricted to the anterior mouth. This was in contrast to most N-best, SU, and UNS PBN neurons, which specifically responded to stimulation of the anterior mouth (anterior tongue and/or nasoincisor ducts). On the other hand, whereas 78% of B-best NST neurons were posterior-only, over half of the B-best PBN neurons also responded to nasoincisor duct stimulation. It is unclear why palatal responses to bitter stimuli were observed infrequently in NST, but it seems possible that such responses were perithreshold and/or sparser in the medulla and more readily observed in PBN due to convergence. This nasoincisor duct input to B-best neurons was also somewhat unexpected because the greater superficial petrosal nerve, which innervates the palate, is highly responsive to sugars but not quinine (Nejad 1986; Sollars and Hill 2005). In agreement with the small bitter responses in the greater superficial petrosal nerve, in situ hybridization suggests that T2R receptors are minimally expressed in the soft palate (Adler et al. 2000; Hoon et al. 1999) although no comparable information is available for the nasoincisor ducts. In light of the bitter-nasoincisor duct responses in the present study, it would be very interesting to examine T2R expression in this receptor subpopulation.

Bitter specificity: reliability, changes with concentration, and coding

Recent reports have stressed the inherent variability of central taste neurons, suggesting the possibility that bitter-selectivity would be less apparent with repeated testing (Chen and Di Lorenzo 2008; Di Lorenzo and Victor 2003, 2007; Roussin et al. 2008). The average CV (0.29) for the 35 neurons tested twice did suggest notable variability in absolute firing rate from one trial to the next. This variability is comparable to that observed by Di Lorenzo and colleagues in NST (CV = 0.31–0.32) (Chen and Di Lorenzo 2008; Di Lorenzo and Victor 2003) and identifies important constraints on the degree to which within-neuron changes in firing rate are able to convey information. On the other hand, relative firing rates remained quite stable (mean r = +0.93, see Fig. 5) with only three neurons (9%) switching best quality from one trial to the next. Two of these neurons were in the broadly tuned AN group and stayed in the same group across trials, but one cell switched from the B-best to the AN cluster. Nevertheless the remaining 11 B-best neurons maintained cluster membership across two trials as did the other 32 neurons assessed. These results are similar to an earlier study in the hamster PBN that reported comparable stability with two to three stimulus replications (Travers and Smith 1984). In the NST, however, Di Lorenzo and colleagues (Chen and Di Lorenzo 2008; Di Lorenzo and Victor 2003) reported that a much larger proportion of neurons (37–39%) changed best-stimulus categories across trials. In those studies, more replications were accomplished. and most of the switches involved broadly tuned neurons. Thus it is possible that greater variability would have emerged in the present study, particularly for AN neurons, with more extensive testing. Alternatively, PBN neurons may have more stable relative response profiles than NST cells due to convergence and higher firing rates. In any case, the unique selectivity of B-best PBN neurons for bitter tastants was reliable at least across a limited time span.

On the other hand, raising stimulus intensity altered the picture of bitter-selectivity. Regardless of concentration, neither quinine- nor cycloheximide-activated neurons preferentially responsive to sugar, glutamate (SU or UNS groups), or sodium (N-best). However, broadly tuned AN cells were quite responsive to quinine at concentrations greater than 3 mM. Likewise, B-best cells responded as well to the highest concentrations of NaCl and HCl as to 3 mM quinine or the weakest cycloheximide. Nevertheless, it was striking that cycloheximide responses were limited to B-best cells over a 10-fold increase in concentration. This suggests overlap among the ionic stimuli (i.e., salt, acid and quinine), whereas the nonionic tastant, cycloheximide, is selective for B-best (and AB) units. Although it will be important to test even more varied bitter ligands and a greater range of intensities in future studies, the clear differences between quinine and cycloheximide support previous neurophysiological and behavioral data suggesting at least two classes of bitter stimuli (see Dotson et al. 2005; Frank et al. 2004; Hacker et al. 2008; Lemon and Smith 2005). Presumably, the cyclohexmide-responsive groups receive input from T2R-expressing taste receptor cells, but the broadly tuned ionic-responsive group (AN) may not. The responsiveness of B-best neurons to high salt and acid concentrations suggests that these units receive input through T2R-independent mechanisms as well as through T2R-dependent ones or perhaps that T2Rs can be activated at high salt or acid concentrations.

The concentration data clearly demonstrate that the specificity of B-best neurons is not absolute. Activation of B-best neurons by higher concentrations of salt and acids suggests that these electrolytes elicit some bitterness or that activity in these neurons fails to provide an unambiguous message signaling bitter tastants. Conditioned taste aversion generalization gradients in rodents (Nowlis et al. 1980) and human psychophysical studies do suggest (Hettinger et al. 1999) a degree of sour-bitter confusion. Likewise, a recent study in rats (Grobe and Spector 2008) used a novel behavioral test that employed taste quality as a discriminative cue and noted some confusion between citric acid and quinine. Nevertheless for the most part these stimuli were clearly discriminable. Furthermore, the possibility of a bitter side taste for NaCl seems rather remote. Indeed neither the conditioned taste aversion (Nowlis et al. 1980) nor the discriminative task provide evidence for generalization between quinine and sodium even with NaCl concentrations as high as 1 M (Grobe and Spector 2008). More work is necessary to rigorously describe the psychophysical properties of salts, acids, and bitter stimuli across a range of stimulus intensities. Nevertheless, the weight of the current evidence suggests that the central mechanism for coding bitterness resembles that for coding other taste qualities—i.e., an ensemble that compares activity across differently tuned neurons is necessary to unambiguously signal a given class of stimuli independent of intensity. Just as importantly, however, the data in the present study emphasize specialized roles for different groups of neurons.

Multidimensional scaling of across-neuron correlations revealed a clear clustering for three of the four bitter tastants, although quinine was located between the acid and bitter groups (see Fig. 7). When B-best neurons were removed, the nonquinine bitters became less cohesive and more allied with the acids. Conversely, without the more broadly tuned AN units, quinine became more closely associated with the other bitters and more segregated from the acids. These results suggest that B-best neurons are important for coding similarity among bitter stimuli and distinguishing bitters from other tastants, especially acids. Previous workers have likewise emphasized the fact that neurons optimally responsive to a given taste quality play a dominant role in the ensemble code for that quality (e.g., Giza and Scott 1991; Smith et al. 1983; St John and Smith 2000). What was not so obvious in previous studies was that there are central neurons with the requisite bitter-selectivity and across- bitter responsiveness to accomplish this task (Di Lorenzo 2000; Giza and Scott 1991; Lemon and Smith 2005; Ogawa and Hayama 1984; but see Cho et al. 2002; Scott et al. 1998). The role of AN neurons in coding bitterness is less clear but provocative. Without these neurons, the most salient change in the multidimensional scaling space is that quinine becomes more segregated from the acids and allied with the other bitter stimuli. From this perspective, AN neurons add noise to the bitter message. Alternatively, these cells may contribute to distinguishing among bitter tastants. The extent of heterogeneity within the bitter quality is still debated (Caicedo and Roper 2001; Dahl et al. 1997; Delwiche et al. 2001; Frank et al. 2004; Hettinger et al. 2007; Spector and Kopka 2002), but the present results suggest that a differential activation of varied neuron types could comprise a neural basis for discriminating different bitter tastants from one another.

The preceding considerations are based on a classical analysis of taste quality coding (Erickson 1974), which quantifies the neural representation of a stimulus as the relative response magnitude across neurons with magnitude defined as summed firing rates. Such an analysis provides considerable insight but undoubtedly represents an oversimplification of coding strategies as well as the functions performed by central gustatory neurons. For example, recent studies suggest that the fine temporal structure of the spike train can contribute information for quality coding, particularly in the case of broadly tuned neurons (Di Lorenzo and Victor 2003). We could not analyze fine temporal structure since such an analysis requires many repeated trials. Nevertheless the differences in gross time course that we observed is suggestive that time course could complement rate coding in PBN. In addition, although our analysis made the tacit assumption that all PBN neurons are coding for taste quality, this may not be true (Spector and Travers 2005). Projections from the PBN target the thalamus, limbic structures, and the medullary reticular formation and each of these regions have distinctive functions. It will be important to define the targets of neurons with known response profiles to better delineate those that project in the thalamocortical pathway and thus are more likely to contribute to quality coding.

RFs and taste functions

We demonstrated that neurons with relatively selective tuning for bitterness were located in PBN, a gustatory relay with direct forebrain projections. Thus despite the fact that most B-best neurons had at least part of their RF on the posterior tongue, such neurons have the potential to play more than a reflexive role in taste functions. This does not imply that posterior-responsive PBN neurons do not contribute to gustatory reflexes. Similar to NST, the PBN projects to the region of the medullary reticular formation required for orchestrating taste-elicited licking and gaping (Karimnamazi and Travers 1998; Morganti et al. 2007). Indeed when the waist area of PBN was lesioned in decerebrate rats, quinine-induced gaping was greatly attenuated (Matsuo et al. 2001). A further complication is that projections from PBN bifurcate to reach limbic structures and the gustatory thalamus (Norgren and Leonard 1973). These two major pathways are usually considered to underlie motivational versus discriminative behaviors and it is unclear to what degree individual PBN neurons contribute to either or both projections (Norgren 1974, 1976; Norgren and Leonard 1973; Ogawa et al. 1987; Voshart and van der Kooy 1981). Indeed studies in awake, behaving animals provide some evidence for at least a subpopulation of narrowly tuned bitter-best neurons in both limbic structures and the cortex (Roitman et al. 2005; Scott et al. 1998; Taha and Fields 2005). Nevertheless, although peripheral nerve lesions suggest that hedonically driven tasks depend on both cranial nerves, discriminative tasks appear to rely much more heavily on input from the VIIth nerve than the IXth (Spector 2003). Thus it is somewhat puzzling that the multidimensional scaling analyses suggest a critical role for B-best neurons in coding for bitterness, but at the same time, nearly all of these cells have IXth nerve input. Perhaps the convergence of VIIth and IXth nerve signals in some B-best cells provides a hint for resolving this apparent discrepancy.

Quinine: a not-so-representative bitter stimulus?

In the PBN, as in NST, quinine was the least effective bitter stimulus. In B-best neurons, 3 mM quinine elicited a response only about 1/3 as large as that elicited by 10 μM cycloheximide. This was true in spite of the comparable and strong behavioral effects of these stimuli in awake animals (Geran and Travers 2006, 2008). At these concentrations, both stimuli elicit a similar number of gapes and reduce appetitive licking to ∼20% of control values in water-deprived animals. Likewise, the efficacy of 3 mM quinine was much less than 10 mM denatonium in the neurophysiological preparation despite its comparable behavioral effectiveness (Geran and Travers 2006, 2008; Spector and Kopka 2002). One possible explanation for the weak quinine response is the recent demonstration that this compound actively inhibits the TRPM5 channel, a critical downstream target of bitter transduction in taste bud cells (Talavera et al. 2008). This inhibition occurs at micromolar concentrations in isolated human embryonic kidney cells expressing TRPM5 but at concentrations similar to those employed in the present study in the intact animal. Interestingly, denatonium does not inhibit the TRPM5 channel. Because TRPM5 channels are the final common path for neurotransmission in T2R-expressing cells (Zhang et al. 2003), quinine may actually inhibit a subset of the taste receptor cells it activates; i.e., those with the most specific bitter responses. This explanation, however, does not resolve the disparity between the behavioral and neural data. We speculate that this discrepancy is due to the much larger stimulus flow rates and volumes in the neurophysiological experiments that may cause more self-inhibition than the smaller amounts typical in behavioral testing. Regardless of the underlying reason, the present observations regarding the relative efficacy of quinine and other bitter tastants urge caution in over-generalizing neurophysiological results obtained using quinine as a representative bitter stimulus.

In contrast, cycloheximide was nominally the most effective bitter stimulus for B-best neurons, just as in NST (Geran and Travers 2006). The potency of this stimulus for rodent neurons with posterior tongue RFs agrees well with Ca2+ imaging studies of the foliate (Caicedo and Roper 2001) and circumvallate (Tomchik et al. 2007) papillae in mice, where cycloheximide activated a larger proportion of taste bud cells than any other bitter stimulus. Cycloheximide utilizes a T2R (rT2R9 in rats; mT2R5 mouse), which is a member of a clade of five genes found in rodents but not humans or even rabbits (Hettinger et al. 2007). It has been postulated that this specialized sensitivity to cycloheximide and related compounds evolved because cycloheximide is a toxin produced by ground-dwelling bacteria, a niche also exploited by rodents (Hettinger et al. 2007). Thus while it is an excellent point that cycloheximide is “no ordinary bitter stimulus” (Hettinger et al. 2007), it appears to be an ecologically relevant one useful for illuminating bitter coding mechanisms in these widely used animal models.

Conclusions

Overall, these data indicate that bitter-selective neurons in NST project substantially to neurons in the PBN with similar bitter-selective, but more homogeneous, neural profiles, suggesting that such bitter-best units might also be found at higher levels of the gustatory system. Furthermore, the finding that most B-best units received input from RFs innervated by both the facial and glossopharyngeal nerves lends credence to the hypothesis that these cells are responsible for more than reflexive gaping. In addition to this relatively selective population of bitter-responsive neurons, however, there is also evidence that bitter-best NST cells converge with acid-sensitive neurons onto a smaller subset of “AB” PBN cells with equivalent responses to acids and bitter stimuli (both ionic and nonionic). It will be interesting to further contrast these two groups of bitter-responsive cells to determine if they are functionally distinct.

GRANTS

This work was funded by National Institute of Deafness and Other Communcations Disorders Grants R01-DC-726315 to S. P Travers and R03-DC-008678 to L. C. Geran.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Joseph Travers and N. Kinzeler for helpful comments on the manuscript as well as K. Herman, J.-E. Yoo, D. Sharp, and P. Pamla-Gutter for technical assistance.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- Adler et al. 2000.Adler E, Hoon MA, Mueller KL, Chandrashekar J, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. A novel family of mammalian taste receptors. Cell 100: 693–702, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens et al. 2004.Behrens M, Brockhoff A, Kuhn C, Bufe B, Winnig M, Meyerhof W. The human taste receptor hTAS2R14 responds to a variety of different bitter compounds. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 319: 479–485, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens et al. 2007.Behrens M, Foerster S, Staehler F, Raguse JD, Meyerhof W. Gustatory expression pattern of the human TAS2R bitter receptor gene family reveals a heterogenous population of bitter responsive taste receptor cells. J Neurosci 27: 12630–12640, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caicedo and Roper 2001.Caicedo A, Roper SD. Taste receptor cells that discriminate between bitter stimuli. Science 291: 1557–1560, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan et al. 2004.Chan CY, Yoo JE, Travers SP. Diverse bitter stimuli elicit highly similar patterns of Fos-like immunoreactivity in the nucleus of the solitary tract. Chem Senses 29: 573–581, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrashekar et al. 2000.Chandrashekar J, Mueller KL, Hoon MA, Adler E, Feng L, Guo W, Zuker CS, Ryba NJ. T2Rs function as bitter taste receptors. Cell 100: 703–711, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen and Di Lorenzo 2008.Chen JY, Di Lorenzo PM. Responses to binary taste mixtures in the nucleus of the solitary tract: neural coding with firing rate. J Neurophysiol 99: 2144–2157, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho et al. 2002.Cho YK, Li CS, Smith DV. Gustatory projections from the nucleus of the solitary tract to the parabrachial nuclei in the hamster. Chem Senses 27: 81–90, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coldwell and Tordoff 1996.Coldwell SE, Tordoff MG. Immediate acceptance of minerals and HCl by calcium-deprived rats: brief exposure tests. Am J Physiol 271: R11–17, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl et al. 1997.Dahl M, Erickson RP, Simon SA. Neural responses to bitter compounds in rats. Brain Res 756: 22–34, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damak et al. 2006.Damak S, Rong M, Yasumatsu K, Kokrashvili Z, Perez CA, Shigemura N, Yoshida R, Mosinger BJ, Glendinning JI, Ninomiya Y, Margolskee RF. Trpm5 null mice respond to bitter, sweet, and umami compounds. Chem Senses 31: 253–264, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damak et al. 2003.Damak S, Rong M, Yasumatsu K, Kokrashvili Z, Varadarajan V, Zou S, Jiang P, Ninomiya Y, Margolskee RF. Detection of sweet and umami taste in the absence of taste receptor T1r3. Science 301: 850–853, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilova and Hellekant 2003.Danilova V, Hellekant G. Comparison of the responses of the chorda tympani and glossopharyngeal nerves to taste stimuli in C57BL/6J mice. BMC Neurosci 4: 5, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delwiche et al. 2001.Delwiche JF, Buletic Z, Breslin PA. Covariation in individuals' sensitivities to bitter compounds: evidence supporting multiple receptor/transduction mechanisms. Percept Psychophys 63: 761–776, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo 2000.Di Lorenzo PM The neural code for taste in the brain stem: response profiles. Physiol Behav 69: 87–96, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo and Monroe 1997.Di Lorenzo PM, Monroe S. Transfer of information about taste from the nucleus of the solitary tract to the parabrachial nucleus of the pons. Brain Res 763: 167–181, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo and Victor 2003.Di Lorenzo PM, Victor JD. Taste response variability and temporal coding in the nucleus of the solitary tract of the rat. J Neurophysiol 90: 1418–1431, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo and Victor 2007.Di Lorenzo PM, Victor JD. Neural coding mechanisms for flow rate in taste-responsive cells in the nucleus of the solitary tract of the rat. J Neurophysiol 97: 1857–1861, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotson et al. 2005.Dotson CD, Roper SD, Spector AC. PLCbeta2-independent behavioral avoidance of prototypical bitter-tasting ligands. Chem Senses 30: 593–600, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson 1974.Erickson RP Parallel population neural coding in feature extraction. In: The Neurosciences, edited by Schmitt FO, Worden FG. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1974, p. 155–169.

- Frank 1991.Frank ME Taste-responsive neurons of the glossopharyngeal nerve of the rat. J Neurophysiol 65: 1452–1463, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank et al. 2004.Frank ME, Bouverat BP, MacKinnon BI, Hettinger TP. The distinctiveness of ionic and nonionic bitter stimuli. Physiol Behav 80: 421–431, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank et al. 1983.Frank ME, Contreras RJ, Hettinger TP. Nerve fibers sensitive to ionic taste stimuli in chorda tympani of the rat. J Neurophysiol 50: 941–960, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulwiler and Saper 1984.Fulwiler CE, Saper CB. Subnuclear organization of the efferent connections of the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. Brain Res 319: 229–259, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia and Hankins 1975.Garcia J, Hankins WG. The evolution of bitter and the acquisition of toxiphobia. In: Olfaction and Taste V, edited by Denton DA, Coghlan JP. New York: Academic, 1975, p. 39–45.

- Geran and Travers 2006.Geran LC, Travers SP. Single neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract respond selectively to bitter taste stimuli. J Neurophysiol 96: 2513–2527, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geran and Travers 2008.Geran LC, Travers SP. Glossopharyngeal nerve transection does not impair unconditioned avoidance of all bitters equally. 25th International Symposium on Olfaction and Taste, San Francisco CA 2008.

- Giza and Scott 1991.Giza BK, Scott TR. The effect of amiloride on taste-evoked activity in the nucleus tractus solitarius of the rat. Brain Res 550: 247–256, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glendinning 1994.Glendinning JI Is the bitter rejection response always adaptive? Physiol Behav 56: 1217–1227, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glendinning 2007.Glendinning JI How do predators cope with chemically defended foods? Biol Bull 213: 252–266, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill and Norgren 1978.Grill HJ, Norgren R. The taste reactivity test. I. Mimetic responses to gustatory stimuli in neurologically normal rats. Brain Res 143: 263–279, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill et al. 1992.Grill HJ, Schwartz GJ, Travers JB. The contribution of gustatory nerve input to oral motor behavior and intake-based preference. I. Effects of chorda tympani or glossopharyngeal nerve section in the rat. Brain Res 573: 95–104, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobe and Spector 2008.Grobe CL, Spector AC. Constructing quality profiles for taste compounds in rats: a novel paradigm. Physiol Behav 95: 413–424, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker et al. 2008.Hacker K, Laskowski A, Feng L, Restrepo D, Medler K. Evidence for two populations of bitter responsive taste cells in mice. J Neurophysiol 99: 1503–1514, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halsell and Travers 1997.Halsell CB, Travers SP. Anterior and posterior oral cavity responsive neurons are differentially distributed among parabrachial subnuclei in rat. J Neurophysiol 78: 920–938, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halsell et al. 1993.Halsell CB, Travers JB, Travers SP. Gustatory and tactile stimulation of the posterior tongue activate overlapping but distinctive regions within the nucleus of the solitary tract. Brain Res 632: 161–173, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellekant et al. 1997.Hellekant G, Danilova V, Ninomiya Y. Primate sense of taste: behavioral and single chorda tympani and glossopharyngeal nerve fiber recordings in the rhesus monkey, Macaca mulatta. J Neurophysiol 77: 978–993, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettinger et al. 2007.Hettinger TP, Formaker BK, Frank ME. Cycloheximide: no ordinary bitter stimulus. Behav Brain Res 180: 4–17, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettinger et al. 1999.Hettinger TP, Gent JF, Marks LE, Frank ME. A confusion matrix for the study of taste perception. Percept Psychophys 61: 1510–1521, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoon et al. 1999.Hoon MA, Adler E, Lindemeier J, Battey JF, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. Putative mammalian taste receptors: a class of taste-specific GPCRs with distinct topographic selectivity. Cell 96: 541–551, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimnamazi and Travers 1998.Karimnamazi H, Travers JB. Differential projections from gustatory responsive regions of the parabrachial nucleus to the medulla and forebrain. Brain Res 813: 283–302, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon and Smith 2005.Lemon CH, Smith DV. Neural representation of bitter taste in the nucleus of the solitary tract. J Neurophysiol 2005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matsuo et al. 2001.Matsuo R, Yamauchi Y, Kobashi M, Funahashi M, Mitoh Y, Adachi A. Role of parabrachial nucleus in submandibular salivary secretion induced by bitter taste stimulation in rats. Auton Neurosci 88: 61–73, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morganti et al. 2007.Morganti JM, Odegard AK, King MS. The number and location of Fos-like immunoreactive neurons in the central gustatory system following electrical stimulation of the parabrachial nucleus in conscious rats. Chem Senses 32: 543–555, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller et al. 2005.Mueller KL, Hoon MA, Erlenbach I, Chandrashekar J, Zuker CS, Ryba NJ. The receptors and coding logic for bitter taste. Nature 434: 225–229, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura and Norgren 1991.Nakamura K, Norgren R. Gustatory responses of neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract of behaving rats. J Neurophysiol 66: 1232–1248, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nejad 1986.Nejad M The neural activities of the greater superficial petrosal rat in response to chemical stimulation of the palate. Chem Senses 11: 283–293, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ninomiya 1998.Ninomiya Y Reinnervation of cross-regenerated gustatory nerve fibers into amiloride-sensitive and amiloride-insensitive taste receptor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 5347–5350, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishijo and Norgren 1991.Nishijo H, Norgren R. Parabrachial gustatory neural activity during licking by rats. J Neurophysiol 66: 974–985, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishijo et al. 1991.Nishijo H, Ono T, Norgren R. Parabrachial gustatory neural responses to monosodium glutamate ingested by awake rats. Physiol Behav 49: 965–971, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgren 1974.Norgren R Gustatory afferents to ventral forebrain. Brain Res 81: 285–295, 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgren 1976.Norgren R Taste pathways to hypothalamus and amygdala. J Comp Neurol 166: 17–30, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgren and Leonard 1973.Norgren R, Leonard CM. Ascending central gustatory pathways. J Comp Neurol 150: 217–237, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowlis et al. 1980.Nowlis GH, Frank ME, Pfaffmann C. Specificity of acquired aversions to taste qualities in hamsters and rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol 94: 932–942, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa and Hayama 1984.Ogawa H, Hayama T. Receptive fields of solitario-parabrachial relay neurons responsive to natural stimulation of the oral cavity in rats. Exp Brain Res 54: 359–366, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa et al. 1987.Ogawa H, Hayama T, Ito S. Response properties of the parabrachio-thalamic taste and mechanoreceptive neurons in rats. Exp Brain Res 68: 449–457, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa et al. 1973.Ogawa H, Sato M, Yamashita S. Variability in impulse discharges in rat chorda tympani fibers in response to repeated gustatory stimulations. Physiol Behav 11: 469–479, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotto and Scott 1976.Perrotto RS, Scott TR. Gustatory neural coding in the pons. Brain Res 110: 283–300, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roitman et al. 2005.Roitman MF, Wheeler RA, Carelli RM. Nucleus accumbens neurons are innately tuned for rewarding and aversive taste stimuli, encode their predictors, and are linked to motor output. Neuron 45: 587–597, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussin et al. 2008.Roussin AT, Victor JD, Chen JY, Di Lorenzo PM. Variability in responses and temporal coding of tastants of similar quality in the nucleus of the solitary tract of the rat. J Neurophysiol 99: 644–655, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott and Giza 1987.Scott TR, Giza BK. A measure of taste intensity discrimination in the rat through conditioned taste aversions. Physiol Behav 41: 315–320, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott et al. 1998.Scott TR, Giza BK, Yan J. Electrophysiological responses to bitter stimuli in primate cortex. Ann NY Acad Sci 855: 498–501, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith et al. 1983.Smith DV, Van Buskirk RL, Travers JB, Bieber SL. Coding of taste stimuli by hamster brain stem neurons. J Neurophysiol 50: 541–558, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollars and Hill 2005.Sollars SI, Hill DL. In vivo recordings from rat geniculate ganglia: taste response properties of individual greater superficial petrosal and chorda tympani neurons. J Physiol 564: 877–893, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector 2003.Spector A The functional organization of the peripheral gustatory system: lessons from behavior. Prog Psychobiol Physiol Psychol 18: 101–161, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Spector and Kopka 2002.Spector AC, Kopka SL. Rats fail to discriminate quinine from denatonium: implications for the neural coding of bitter-tasting compounds. J Neurosci 22: 1937–1941, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector and Travers 2005.Spector AC, Travers SP. The representation of taste quality in the mammalian nervous system. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev 4: 143–191, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielman et al. 1992.Spielman AI, Huque T, Whitney G, Brand JG. The diversity of bitter taste signal transduction mechanisms. In: Sensory Transduction, edited by Corey DP, Roper SD. New York: The Rockefeller University Press, 1992, p. 307–324. [PubMed]

- St John and Smith 2000.St John SJ, Smith DV. Neural representation of salts in the rat solitary nucleus: brain stem correlates of taste discrimination. J Neurophysiol 84: 628–638, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner 1979.Steiner JE Human facial expressions in response to taste and smell stimulation. Adv Child Dev Behav 13: 257–295, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita and Shiba 2005.Sugita M, Shiba Y. Genetic tracing shows segregation of taste neuronal circuitries for bitter and sweet. Science 309: 781–785, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taha and Fields 2005.Taha SA, Fields HL. Encoding of palatability and appetitive behaviors by distinct neuronal populations in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci 25: 1193–1202, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talavera et al. 2008.Talavera K, Yasumatsu K, Yoshida R, Margolskee RF, Voets T, Ninomiya Y, Nilius B. The taste transduction channel TRPM5 is a locus for bitter-sweet taste interactions. Faseb J 22: 1343–1355, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomchik et al. 2007.Tomchik SM, Berg S, Kim JW, Chaudhari N, Roper SD. Breadth of tuning and taste coding in mammalian taste buds. J Neurosci 27: 10840–10848, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers et al. 1987.Travers JB, Grill HJ, Norgren R. The effects of glossopharyngeal and chorda tympani nerve cuts on the ingestion and rejection of sapid stimuli: an electromyographic analysis in the rat. Behav Brain Res 25: 233–246, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers and Smith 1984.Travers SP, Smith DV. Responsiveness of neurons in the hamster parabrachial nuclei to taste mixtures. J Gen Physiol 84: 221–250, 1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Buskirk and Smith 1981.Van Buskirk RL, Smith DV. Taste sensitivity of hamster parabrachial pontine neurons. J Neurophysiol 45: 144–171, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voshart and van der Kooy 1981.Voshart K, van der Kooy D. The organization of the efferent projections of the parabrachial nucleus of the forebrain in the rat: a retrograde fluorescent double-labeling study. Brain Res 212: 271–286, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]