Abstract

Background and objectives: Novel individualized quality-of-life (IQOL) measures permit patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) to nominate unique areas of their lives that contribute to their well-being. This study assessed for differences in domains nominated by patients with CKD. We also examined the strength of association between (1) multidimensional health-related quality-of-life measures and IQOL and (2) psychosocial factors and IQOL.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: We performed a cross-sectional study of 151 patients who were undergoing peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis or had stages 4 through 5 CKD. Patients completed the Schedule for the Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life–Direct Weighting (SEIQOL-DW), an instrument that assesses IQOL on the basis of patient-identified domains. Patients also completed health-related quality-of-life and psychosocial health measures.

Results: Patients with CKD nominated many domains on the SEIQOL-DW, but family and health were the most common for all groups. Kidney disease was listed more frequently by peritoneal dialysis compared with hemodialysis patients or patients with CKD (31 versus 14 versus 5%, respectively). There were no significant differences in SEIQOL-DW scores between subgroups. SEIQOL-DW scores correlated with mental well-being and inversely correlated with chronic stress and depression.

Conclusions: Patients with advanced CKD demonstrate compromised quality-of-life scores comparable to dialysis patients. IQOL measures provide unique information that may help guide interventions that are better tailored to address patients’ concerns about their well-being. These findings also suggest that renal clinics should have staff available to address psychosocial aspects of patient well-being.

Assessment of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) has evolved with treatment advances so that the expectation of patient outcomes has grown from simple survival to achieving a sense of well-being (1). HRQOL has been assessed in CKD using multidimensional measures that capture information about function and well-being across predefined domains that are thought to be relevant to an overall assessment of HRQOL (2). Hence, HRQOL reflects the welfare of a patient on the basis of aspects of functional status (including physical, mental, and social factors) and a relative balance of expectations and experiences in the face of changing health; however, there may be a disconnect between measured HRQOL and patient perceived QOL (3), and proxies often fare poorly when trying to assess HRQOL (4,5). The potential sources of this disconnect may reflect cultural differences, coping mechanisms, and individual values (5,6).

Although HRQOL questionnaires may include inquiries into multiple dimensions such as pain, functional status, and mood, by design, these generic HRQOL measures ignore domains that are uniquely important to each patient. These neglected domains can be crucial to understanding the overall sense of well-being of a patient with CKD (7). By neglecting these factors, HRQOL questionnaires fail to capture patients’ individual values, which play an influential role in determining domains that are important to overall QOL (8,9). A more individualized assessment of QOL would allow patients to select domains that they view as particularly pertinent to their own well-being. For example, the Schedule for the Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life (SEIQOL) is an established instrument that seeks to assess QOL on the basis of domains that the patient deems important (8,10,11). This measure has been applied to a variety of chronic disease states such as HIV (8), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (9), and cancer (12,13). Previous work that used the SEIQOL in the hemodialysis (HD) population was limited to a single study of 48 patients that examined domains that were nominated as contributing to QOL, level of function in each of those domains, and the interrelation between SEIQOL score and psychosocial factors such as perceived control, social support, and hostility (14). The SEIQOL addresses the potential drawback of HRQOL instruments that limit factors that compose the well-being of patients. Such individualized QOL (IQOL) measures are consistent with the Institute of Medicine's goals of patient-centered care (15).

For better understanding of the relationship between dialysis and IQOL in patients with CKD, this report examines the association of SEIQOL scores with either HD or peritoneal dialysis (PD) or non–dialysis-dependent advanced CKD. To this aim, we also explore differences in domains nominated by these distinct populations when using an individualized assessment tool. Second, among patients with CKD, we assess the strength of association between scores on multidimensional HRQOL measures and IQOL. Third, we investigate the relationship between psychosocial factors and IQOL in populations with CKD.

Materials and Methods

Study Setting and Design

The study sample was composed of patients with stages 4 through 5 CKD, patients who were undergoing PD, and patients who were undergoing thrice-weekly in-center HD in Western Pennsylvania. Patients were approached to be in a study of kidney disease, sleep, mood, cognition, and QOL at the time of their routine CKD clinic visit, dialysis clinic visit, or initial evaluation visit at a kidney transplantation clinic. The study was performed between March 2004 and November 2007. Participants were excluded for the following reasons: Age <18 yr or >90 yr, severe comorbid illness, or an unsafe home environment. This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh institutional review board, and all participants provided informed consent.

A total of 267 patients were screened for study participation. Of these, 19 either met exclusion criteria or declined consent and 97 did not complete the QOL assessment (20 because of failing health, 67 because of time constraints or loss of interest, three for unsafe home environment, and seven because of death). The 151 remaining HD, PD, and CKD participants are included in this report.

Measures of QOL, HRQOL, Mood, Stress, and Coping

All assessments took place in patients’ homes via interview or self-administered questionnaires. The Schedule of Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life–Direct Weighting (SEIQOL-DW) is a patient-centered measure of QOL that is administered as a semistructured interview (11). The SEIQOL-DW uses a three-stage approach to IQOL assessment that produces a single score between 0 and 100. Respondents (1) nominate the life areas or factors that are important to their QOL, (2) rate their current level of function in each of those areas (on a scale from 1 to 100, with higher ratings indicating better function), and (3) rate the relative importance of each of these areas (with the total summing to 100). The grouping of nominated SEIQOL factors into larger domains was performed by two investigators who independently coded responses and came to a consensus with conflicts resolved by a third investigator. This process was repeated with the grouping of the factors into larger, broad categories. The SEIQOL-DW interview includes a single-item general QOL visual analog scale (GLOBAL-QOL) that rates overall health. SEIQOL-DW calculated scores (IQOL scores), and GLOBAL-QOL scores both range from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating a better well-being.

Patients also completed the following questionnaires: Short Form-36 (SF-36), Dialysis Symptom Index, Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), Perceived Stress Scale 4 (PSS-4), Brief Cope, and Impact of Events Scale. The SF-36 questionnaire has been used extensively in studies of HRQOL in ESRD, the general population, and kidney transplantation (16–18). The SF-36 contains eight subscales (physical function, role limitations–physical, bodily pain, vitality, general health perceptions, role limitations–emotional, social function, and mental health) and two component summary scores (physical component summary and mental component summary) (19). In the general population, the mean for each summary scale is 50 points with an SD of 10 points. Higher scores indicate a better HRQOL (20).

The Dialysis Symptom Index (21) is a 30-item questionnaire that assesses the presence and severity of physical and emotional symptoms during a 1-wk period in patients who are dependent on dialysis. Scores range from 0 to 150, and higher scores indicate a higher symptom/severity burden.

The Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) (22) is the nine-item depression module of the PHQ. Scores range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating an increased severity of depressive symptoms. The PSS-4 quantifies subjective distress associated with ongoing stressful events or circumstances (23). This four-item questionnaire focuses on subjective ambient stress during the previous month. Scores on the PSS-4 range from 0 to 16; higher scores reflect greater amounts of perceived stress.

The Brief COPE is a 28-item self-report questionnaire that quantifies coping style in response to a self-identified stressor and is applicable to a variety of clinical populations (24). Previous factor analysis of the Brief COPE revealed five higher order subscales (25). These factors were active planning, seeking support, avoidant coping, acceptance, and self-blame. Higher subscale scores indicate greater use of the respective coping technique. The avoidant coping variable was dichotomized (67th percentile and greater versus the remainder of the distribution) to identify a group that exhibited the greatest avoidant coping behavior.

The Impact of Events Scale is a 15-item questionnaire that measures current subjective distress related to a specific event (26). The questions assess for intrusive and avoidance symptoms. A summative total subjective distress score (ranging from 0 to 75) is produced; higher scores indicate greater perceived distress.

Statistical Analyses

Differences between CKD groups were tested using two-sample t test or ANOVA for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Correlations of coping styles, IQOL, and HRQOL measures were examined using Pearson correlation coefficients and Spearman correlation coefficients when appropriate. Furthermore, we constructed a multiple linear regression model to identify factors that were independently associated with the SEIQOL-DW–calculated score (IQOL score) or the visual analogue scale GLOBAL-QOL score. Model selection was based on variables that were found to have a relationship (P < 0.10) in bivariate analysis and major demographic factors and dialysis treatment group. Backward selection examined the parameter estimates after every iteration to derive a parsimonious model. Analyses were performed using SAS 8.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 displays the study sample's characteristics. HD patients were older than their PD counterparts. PD patients were more likely to be black and have a lower body mass index than patients with CKD, and approximately 30% had diabetes. Baseline mean hemoglobin level did not differ between the subgroups. Baseline mean creatinine and estimated GFR (calculated by the four-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease [MDRD] Study equation) in the subgroup with stages 4 through 5 CKD was 4.2 mg/dl (SD 1.5 mg/dl) and 16.9 ml/min (SD 5.6 ml/min), respectively (data not shown; serum creatinine in mg/dl may be converted to μmol/L by multiplying by 88.4; GFR in ml/min may be converted to ml/s by multiplying by 0.01667). Patients who were excluded from the study were similar in age and race to the study participants; however, a greater proportion of study participants were men (66 versus 51%; P = 0.009).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study sample in ESRD and CKD samplesa

| Characteristic | HD(n = 70) | PD(n = 16) | CKD 4 to 5(n = 65) | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr, mean [SD]) | 55.1 (14.4) | 44.6 (15.4) | 51.8 (14.5) | 0.03 |

| Men (n [%]) | 64.3 (45) | 43.8 (7) | 73.9 (48) | 0.07 |

| Black (n [%]) | 37.1 (26) | 50.0 (8) | 20.0 (13) | 0.05 |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean [SD]) | 27.3 (5.2) | 25.0 (6.2) | 28.7 (5.5) | 0.05 |

| Diabetes (n [%]) | 37.1 (26) | 12.5 (2) | 26.1 (17) | 0.20 |

| Cardiovascular disease (n [%]) | 34.3 (24) | 25.0 (4) | 24.6 (16) | 0.80 |

| Karnofsky score (n [%])c | 23.5 (16) | 15.4 (2) | 9.1 (5) | 0.08 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl; mean [SD])d | 11.9 (1.6) | 11.1 (0.8) | 11.8 (1.3) | 0.30 |

BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HD, hemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

χ2 or ANOVA was used as appropriate.

Proportion of patients with score <80% (signifying an inability to perform normal activities).

Hemoglobin in g/dl can be converted to g/L by multiplying by 10.

Demographics and SEIQOL Score

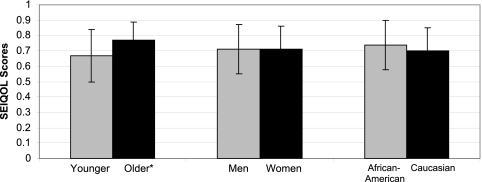

There were no significant differences between CKD groups with regard to SEIQOL scores, HRQOL scores, or psychosocial measures as shown in Table 2. Stratifying by the median age of 53 yr, older age was associated with a significantly higher calculated SEIQOL score, as shown in Figure 1. There was no significant unadjusted association between either race or gender and SEIQOL-DW–calculated IQOL scores (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Quality of life and psychosocial measures in ESRD and CKD samplesa

| Parameter | HD(n = 70) | PD(n = 16) | CKD 4 to 5(n = 65) | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated IQOL SEIQOL Scorec | 0.69 (0.16) | 0.68 (0.18) | 0.74 (0.15) | 0.2 |

| Visual Analog Scale GLOBAL SEIQOL Scorec | 0.63 (0.22) | 0.55 (0.24) | 0.66 (0.18) | 0.2 |

| SF-36 Mental Health Composited | 45.00 (7.30) | 44.10 (6.50) | 43.90 (7.50) | 0.7 |

| SF-36 Physical Health Composited | 40.50 (6.10) | 39.40 (6.10) | 40.30 (6.90) | 0.8 |

| Perceived Stress Scalee | 5.80 (3.40) | 5.60 (3.60) | 5.60 (2.80) | 0.9 |

| Impact of Events Scalef | 21.00 (16.50) | 32.90 (15.00) | 26.10 (18.00) | 0.1 |

| Dialysis Symptom Indexg,h | 21.50 (15.50) | 22.90 (15.00) | 18.30 (13.60) | 0.3 |

| Active coping | 2.41 (0.91) | 2.46 (0.92) | 2.48 (0.87) | 0.9 |

| High support coping | 2.26 (0.76) | 2.26 (0.62) | 2.21 (0.73) | 0.9 |

| Avoidant copingi | 1.20 (0.33) | 1.29 (0.39) | 1.21 (0.28) | 0.7 |

| Acceptance coping | 2.13 (0.69) | 2.21 (0.63) | 2.20 (0.57) | 0.8 |

| Blame copingi | 1.52 (0.92) | 1.31 (0.66) | 1.53 (0.65) | 0.4 |

| Patient Health Questionnaire depression gradeh,j | 4.62 (3.81) | 4.94 (3.99) | 5.46 (4.60) | 0.5 |

SEIQOL, Schedule for the Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life; SF-36, Short Form-36.

χ2 or ANOVA was used as appropriate.

Scores range from 0 to 1; higher scores indicate a better quality of life.

In the general population, the mean for each summary scale is 50 with an SD of 10 points; higher scores indicate a better health-related quality of life.

Scores range from 0 to 56; higher scores reflect greater amounts of perceived stress.

Scores range from 0 to 75; higher scores reflect greater distress to an event that occurred in the past 6 mo.

Scores range from 0 to 150; higher scores indicate a higher symptom/severity burden.

Square root transformation.

Log transformation.

Scores range from 0 to 27; higher scores indicate increased severity of depressive symptoms.

Figure 1.

Associations between Schedule for the Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life (SEIQOL) scores and demographic variables. *P < 0.001.

SEIQOL Domains

The frequency of IQOL factors that were nominated by patients is shown in Table 3. The patient subgroups identified a similar range of domains, including family, health, work/school, financial, leisure, spiritual, and interpersonal concerns, as major contributing factors to their well-being. Although family was the most common QOL domain nominated by patients in all subgroups, it was marginally more frequent in patients with CKD compared with their dialysis counterparts. Kidney health and disease was identified more frequently as a major area of importance for QOL by PD patients than by HD patients or patients with CKD. Mobility tended to be a more frequently nominated factor for HD patients and patients with CKD than for PD patients, although this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Table 3.

SEIQOL-DW quality-of-life factors endorsed by patients

| Parameter | Total Nominating Domain (% [n]; n = 151) | Nominated (% [n])

|

Test Statistic (χ2 or Fisher Exact Test) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD(n = 70) | PD(n = 16) | CKD 4 to 5(n = 65) | |||

| Family | 90.7 (137) | 87.1 (61) | 81.3 (13) | 96.9 (63) | 5.7a |

| Health | 69.5 (105) | 72.9 (51) | 62.5 (10) | 67.7 (44) | 0.8 |

| Work/school | 34.4 (52) | 25.7 (18) | 37.5 (6) | 43.1 (28) | 4.6 |

| Financial | 33.7 (51) | 38.6 (27) | 43.8 (7) | 26.2 (17) | 3.1 |

| Leisure | 31.7 (48) | 27.1 (19) | 31.3 (5) | 36.9 (24) | 1.5 |

| Spiritual | 27.8 (42) | 30.0 (21) | 37.5 (6) | 23.1 (15) | 1.6 |

| Interpersonal | 25.8 (39) | 20.0 (14) | 37.5 (6) | 29.2 (19) | 2.5 |

| Nonfamily social | 22.5 (34) | 20.0 (14) | 12.5 (2) | 27.7 (18) | 2.2 |

| Home/living situation | 17.2 (26) | 15.7 (11) | 25 (4) | 16.9 (11) | 0.8 |

| Kidney health/disease | 11.9 (18) | 14.3 (10) | 31.3 (5) | 4.6 (3) | 9.4b |

| Mobility | 11.3 (17) | 17.1 (12) | 0 | 7.7 (5) | 5.3c |

| Comfort/happiness | 9.3 (14) | 10.0 (7) | 6.3 (1) | 9.2 (6) | 0.2 |

| Self-fulfillment | 8.6 (13) | 10.0 (7) | 12.5 (2) | 6.2 (4) | 1.0 |

| Being alive | 7.9 (12) | 10.0 (7) | 6.3 (1) | 6.2 (4) | 0.8 |

| Pet | 7.9 (12) | 7.1 (5) | 0 | 10.8 (7) | 2.2 |

| Peace/world situation | 5.3 (8) | 7.1 (5) | 6.3 (1) | 3.1 (2) | 1.1 |

| Helping others | 4.6 (7) | 4.3 (3) | 0 | 6.2 (4) | 1.1 |

| Self-sufficiency/independence | 3.3 (5) | 2.9 (2) | 0 | 4.6 (3) | 0.9 |

| Other | 6.0 (9) | 8.6 (6) | 0 | 4.6 (3) | 2.1 |

P = 0.06.

P = 0.01.

P = 0.08.

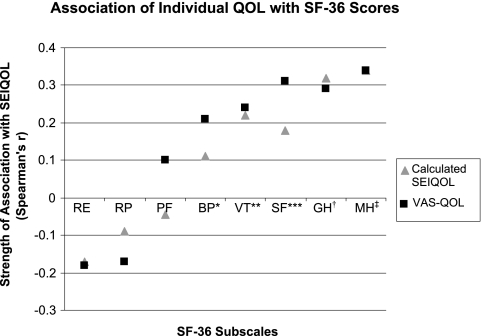

Correlation of HRQOL and IQOL

The correlation between SEIQOL scores and SF-36 subscales is displayed in Figure 2. The mental health, vitality, and general health subscales correlated with the SEIQOL-DW–calculated IQOL score and single-item GLOBAL-QOL score. These correlations indicate a significant association between SEIQOL scores and subscales of the SF-36 that assess emotional and mental well-being and psychosocial factors. In addition, the mental health composite score (MCS) of the SF-36 correlated with both the SEIQOL-DW–calculated IQOL score and GLOBAL-QOL score, revealing that when emotional and mental well-being were higher, IQOL and single-item GLOBAL-QOL scores were also higher.

Figure 2.

SEIQOL Association with Short Form-36 (SF-36) subscales. VAS-QOL, Visual Analog Scale Quality of Life; RE, role limitations–emotional; RP, role limitations–physical; PF, physical function; BP, bodily pain; VT, vitality; SF, social function; GH, general health; MH, mental health. *VAS-QOL P = 0.01; **VAS-QOL P = 0.004 and calculated SEIQOL P = 0.01; ***VAS-QOL P < 0.001 and calculated SEIQOL P = 0.03; †VAS-QOL and calculated SEIQOL P < 0.001; ‡VAS-QOL and calculated SEIQOL P < 0.001.

Psychosocial Factors and SEIQOL Scores

The association between IQOL and psychosocial measures is shown in Table 4. The SEIQOL-DW–calculated IQOL score exhibited a negative correlation with the avoidant coping subscale, the total perceived stress score, and the PHQ depression score. This indicates that avoidant coping mechanisms, increasing stress, and worsening depressive symptoms all were associated with lower SEIQOL scores. It is interesting that the SEIQOL-DW–calculated IQOL score and GLOBAL-QOL score demonstrated very similar patterns of correlation with the psychosocial measures tested.

Table 4.

Strength of relationships between SEIQOL and psychosocial factorsa

| Parameter | SEIQOL-DW–Calculated IQOL | VAS GLOBAL-QOL |

|---|---|---|

| PSS-4 | r = −0.30 | r = −0.48 |

| P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | |

| Impact of Events | r = −0.15 | r = −0.23 |

| P = 0.100 | P = 0.020 | |

| Active coping | r = −0.07 | r = −0.09 |

| P = 0.400 | P = 0.300 | |

| High support coping | r = 0.10 | r = 0.02 |

| P = 0.300 | P = 0.800 | |

| Avoidant copingb | r = −0.19 | r = −0.36 |

| P = 0.020 | P < 0.001 | |

| Acceptance coping | r = 0.01 | r = 0.04 |

| P = 0.90 | P = 0.600 | |

| Blame copingb | r = −0.15 | r = −0.10 |

| P = 0.100 | P = 0.200 | |

| PHQ depression gradec | r = −0.22 | r = −0.31 |

| P = 0.010 | P < 0.001 | |

| Dialysis Symptoms Indexc | r = −0.04 | r = −0.20 |

| P = 0.600 | P = 0.020 |

Data are Pearson correlation coefficient and P value (except as noted). PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PSS-4, Perceived Stress Scale 4; VAS GLOBAL-QOL, Visual Analog Scale Global Quality of Life.

Log transformation; Spearman correlation coefficient and P value.

Square root transformation.

Independent Associations with SEIQOL Scores

In our multiple linear regression model, age, race, renal replacement therapy modality, and PHQ depression score were independently associated with SEIQOL-DW–calculated IQOL scores, as shown in Table 5. Increasing age, black race, non-HD status, and lower PHQ depression score (indicating lower depressive symptom burden) independently correlated with higher calculated IQOL scores. Increasing age, lower avoidant coping scores (indicating less use of avoidant coping strategies), and lower PSS scores (indicating lower levels of perceived stress) correlated with higher GLOBAL-QOL scores.

Table 5.

Factors independently associated with IQOLa

| Parameter | SEIQOL-DW–Calculated IQOL | SEIQOL-VAS GLOBAL-QOL |

|---|---|---|

| Age | β1 = 0.003 (0.001) | β1 = 0.002 (0.001) |

| P = 0.002 | P = 0.050 | |

| Race | β1 = 0.060 (0.030) | β1 = −0.030 (0.040) |

| P = 0.070 | P = 0.400 | |

| Renal replacement therapy modalityb | β1 = −0.060 (0.030) | β1 = −0.010 (0.040) |

| P = 0.040 | P = 0.700 | |

| PHQ depression scorec | β1 = −0.030 (0.010) | β1 = −0.020 (0.020) |

| P = 0.050 | P = 0.200 | |

| Avoidant coping | β1 = −0.050 (0.030) | β1 = −0.100 (0.040) |

| P = 0.200 | P = 0.020 | |

| PSS-4 | β1 = −0.002 (0.005) | β1 = −0.020 (0.006) |

| P = 0.600 | P < 0.001 |

Data are linear regression standardized β1 value (SE) and P value.

HD versus non-HD.

Square root transformation.

Discussion

This study identified 11 separate domains that each were endorsed by >10% of our study sample. This highlights the diversity of factors that contribute to QOL in CKD but are not typically assessed by generic HRQOL instruments. Our findings show that family and health are consistent factors in determining IQOL in our sample. Importantly, decrements in IQOL and other health-related measures extend to non–dialysis-dependent patients with CKD. Older individuals reported better IQOL, and both age and race were independently associated with calculated SEIQOL scores in multivariate analysis. SEIQOL scores exhibited a moderate correlation with several generic HRQOL and health-related measures. Generally, these were assessments of psychological well-being and social functioning.

The average SEIQOL score (calculated IQOL) in this sample was profoundly impaired, ranging from 68 to 74 in the three subgroups. This is comparable to mean scores in patient cohorts of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (27), stroke survivors (10), metastatic cancer (6), malignant cord compression (12), and hematologic malignancies (28). These findings emphasize that patients with advanced CKD or ESRD perceive a severely compromised QOL. When coupled with the growing prevalence of CKD (29), these data underscore the need for interventions to have a positive impact on multiple domains that influence QOL in the CKD population. Further studies are needed to determine whether providers should place a greater emphasis on assessing and strengthening the social support networks and resources that are available to patients in CKD and dialysis clinics to maintain or improve well-being despite worsening disease status.

Consistent with Tovbin's findings in HD patients, the most frequently nominated SEIQOL domains in our study were family, health, work/school, finances, and leisure (14). These findings differ from previous reports of older adults (aged >75 yr) with good health status and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (30) in that health, finances, and work/school cues appear much more frequently in our study, emphasizing the potential differences and effects of disease in these patient groups. In contrast to other studies in which health is an infrequently nominated domain by the chronically ill and more frequently nominated by healthy individuals (31,32), health seems to be an important contributor to IQOL in patients with CKD and dialysis patients; however, it is noteworthy that approximately one third of patients with significant renal dysfunction did not nominate health as a QOL domain.

Patient-identified domains were similar in the HD, PD, and stages 4 through 5 CKD subgroups; however, PD patients were more likely to identify kidney health and disease as a QOL factor. We hypothesize that the emphasis placed on residual renal function for technique survival in PD may have contributed to these differences. In addition, patients with stages 4 through 5 CKD may have considered their renal function as a key determinant of their general health and consequently failed to identify it separately. Perhaps surprising, PD patients were somewhat (but not statistically reliably) less likely to identify mobility as a QOL determinant. Many of the PD patients in this study enjoyed excellent mobility and functional status, and this may have contributed to their less frequent identification of mobility as a QOL determinant. In addition, despite the presence of an active, local PD program, we cannot be certain that patients were provided with a choice of dialysis modality. This lack of choice may have offset the usual tendency of patients who highly value mobility and independence to choose PD.

Similar to previous work, depression and avoidant coping strategies were independently associated with calculated IQOL scores in our population (14). In addition, the generic HRQOL scales that best correlated with SEIQOL scores (calculated IQOL) were the mental health, general health, and social function domains of the SF-36, and this is consistent with previous studies (10,32). These results suggest important connections in patients with chronic or life-threatening illnesses between IQOL and psychosocial issues and coping mechanisms (9,13,33,34). The causal direction of these effects remains to be delineated. Further work is needed to determine whether treatment of depressive or stress-related symptoms may improve patients’ IQOL scores or, alternatively, whether intervention strategies that are designed to improve IQOL may mediate improvements in depressive and stress-related symptoms. The moderate association with some but not all nonindividualized QOL instruments supports the position that IQOL instruments may add useful information not gathered with conventional measures. Further research is needed to investigate whether this additional information may be important in helping health care providers appropriately target interventions to improve QOL in the CKD population and achieve a patient-centered approach to care as advocated by the Institute of Medicine (15).

Understanding the individual factors that contribute to a patient's well-being may provide health care workers with an opportunity to engage in advance care planning, an approach to addressing end-of-life care through open communication between patients and their families and the health care team (35). In this setting, IQOL assessments could help physicians focus on anticipated patient health states and qualities of living while discussing goals of care that are consistent with the patient's values and wishes. Ultimately, this may help patients achieve better control over their health care and strengthen relationships within their family (36).

Our findings demonstrated an independent association between higher IQOL scores and black race as well as older age. Black race correlated with higher SEIQOL scores, consistent with previous findings in the HD population using HRQOL instruments (37,38). Patients above the median age of our study population (53 yr) had significantly higher GLOBAL-QOL and calculated IQOL scores. Younger patients may experience a larger gap between their expected and actual QOL and may therefore score lower on QOL assessments than older patients, whose experiences are more aligned with their expectations (39). These findings are consistent with the longitudinal HRQOL data in the Hemodialysis (HEMO) Study, and the North Thames Study findings (40–42) suggest that targeting future interventions at younger patients with CKD may have a larger impact on improving HRQOL. Providers should be alert to this disparity in QOL found among younger patients. Interventions aimed at preserving residual renal function (43), monitoring HRQOL (44), treatment of anemia (45), physical therapy and rehabilitation (46), measurement of symptoms, and application of palliative care principles (47) may preserve QOL among patients who undergo HD.

The findings of this report should be interpreted in light of several limitations. These include the cross-sectional design and a relatively small sample size, although it represents the largest SEIQOL study of patients with CKD to date. It would be useful to follow the SEIQOL longitudinally in the CKD population to assess changes in IQOL scores and the domains endorsed. The work of Sprangers and Schwarz (48,49) and others (6,50) suggest that, over time, those with a chronic illness may shift their expectations in life, and we anticipate that this shift would be captured by the domains elicited by the SEIQOL-DW. The use of both IQOL and HRQOL instruments caused a significant respondent burden and may have decreased the enrollment of less functional patients; however, this burden was addressed in part by performing the assessments in patients’ homes, which may have diminished participant burden. Patients with severe comorbid illnesses were also excluded from the study.

Conclusions

IQOL measures allow for an appreciation of the diverse factors that affect a patient's sense of well-being and may help guide interventions that are better tailored to improve patients’ unique QOL issues than do generic HRQOL instruments. The IQOL of patients with CKD is reduced, and the severity of impairment was comparable in the stages 4 through 5 CKD and dialysis populations. IQOL may also help providers better appreciate factors that motivate their patients, with subsequent opportunities to discuss goals of care and approaches to improve care in the eyes of their patients. Further research is needed to explore whether IQOL assessments can be used effectively to guide patient interventions. These interventions should focus on addressing psychosocial aspects of well-being, including strengthening social support networks and the development of nondetrimental patient coping strategies. Future studies should also focus on further delineating the relationship among IQOL, depression, and coping mechanisms.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Fresenius National Kidney Foundation Young Investigator Grant, Paul Teschan Research Grant, National Institutes of Health grants DK66006 and DK77785 (M.U.), and Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Institutional Research Training Grant T32-DK061296 (K.A.).

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Unruh M: Health related quality of life in patients with chronic kidney disease. Int Urol Nephrol 37: 367–378, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guyatt G, Feeny D, Patrick D: Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med 118: 622–629, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimmel PL: Just whose quality of life is it anyway? Controversies and consistencies in measurements of quality of life. Kidney Int 57: S113–S120, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moinpour CM, Lyons B, Schmidt SP, Chansky K, Patchell RA: Substituting proxy ratings for patient ratings in cancer clinical trials: An analysis based on a Southwest Oncology Group trial in patients with brain metastases. Qual Life Res 9: 219–231, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sprangers MA, Aaronson NK: The role of health care providers and significant others in evaluating the quality of life of patients with chronic disease: A review. J Clin Epidemiol 45: 743–760, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharpe L, Butow P, Smith C, McConnell D, Clarke S: Changes in quality of life in patients with advanced cancer: Evidence of response shift and response restriction. J Psychosom Res 58: 497–504, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joyce CR, Hickey A, McGee HM, O'Boyle CA: A theory-based method for the evaluation of individual quality of life: The SEIQoL. Qual Life Res 12: 275–280, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hickey AM, Bury G, O'Boyle CA, Bradley F, O'Kelly FD, Shannon W: A new short form individual quality of life measure (SEIQoL-DW): Application in a cohort of individuals with HIV/AIDS. BMJ 313: 29–33, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neudert C, Wasner M, Borasio GD: Patients’ assessment of quality of life instruments: A randomised study of SIP, SF-36 and SEIQoL-DW in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 191: 103–109, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LeVasseur SA, Green S, Talman P: The SEIQoL-DW is a valid method for measuring individual quality of life in stroke survivors attending a secondary prevention clinic. Qual Life Res 14: 779–788, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Boyle CA, Browne J, Hickey A, McGee HM, Joyce CR: Schedule for the Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life (SEIQoL): A Direct Weighting Procedure for Quality of Life Domains (SEIQoL-DW). Administration Manual, Dublin, Department of Psychology, Royal College of Surgeons, 1995

- 12.Levack P, Graham J, Kidd J: Listen to the patient: Quality of life of patients with recently diagnosed malignant cord compression in relation to their disability. Palliat Med 18: 594–601, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waldron D, O'Boyle CA, Kearney M, Moriarty M, Carney D: Quality-of-life measurement in advanced cancer: Assessing the individual. J Clin Oncol 17: 3603–3611, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tovbin D, Gidron Y, Jean T, Granovsky R, Schnieder A: Relative importance and interrelations between psychosocial factors and individualized quality of life of hemodialysis patients. Qual Life Res 12: 709–717, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 2001

- 16.Singer MA, Hopman WM, MacKenzie TA: Physical functioning and mental health in patients with chronic medical conditions. Qual Life Res 8: 687–691, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merkus MP, Jager KJ, Dekker FW, de Haan RJ, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT: Physical symptoms and quality of life in patients on chronic dialysis: Results of the Netherlands Cooperative Study on Adequacy of Dialysis (NECOSAD). Nephrol Dial Transplant 14: 1163–1170, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franke GH, Reimer J, Kohnle M, Luetkes P, Maehner N, Heemann U: Quality of life in end-stage renal disease patients after successful kidney transplantation: Development of the ESRD symptom checklist—Transplantation module. Nephron 83: 31–39, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30: 473–483, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M, Gandek B: SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide, Boston, Health Institute, New England Medical Center, 1993

- 21.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, Rotondi AJ, Fine MJ, Levenson DJ, Switzer GE: Development of a symptom assessment instrument for chronic hemodialysis patients: The Dialysis Symptom Index. J Pain Symptom Manage 27: 226–240, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB: Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA 282: 1737–1744, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R: A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 24: 385–396, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carver CS: You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: Consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med 4: 92–100, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myaskovsky L, Dew MA, Switzer GE, Hall M, Kormos RL, Goycoolea JM, DiMartini AF, Manzetti JD, McCurry KR: Avoidant coping with health problems is related to poorer quality of life among lung transplant candidates. Prog Transplant 13: 183–192, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W: Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 41: 209–218, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neudert C, Wasner M, Borasio GD: Individual quality of life is not correlated with health-related quality of life or physical function in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Palliat Med 7: 551–557, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montgomery C, Pocock M, Titley K, Lloyd K: Predicting psychological distress in patients with leukaemia and lymphoma. J Psychosom Res 54: 289–292, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Levey AS: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 298: 2038–2047, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lhussier M, Watson B, Reed J, Clarke CL: The SEIQoL and functional status: How do they relate? Scand J Caring Sci 19: 403–409, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGee HM, O'Boyle CA, Hickey A, O'Malley K, Joyce CR: Assessing the quality of life of the individual: The SEIQoL with a healthy and a gastroenterology unit population. Psychol Med 21: 749–759, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Boyle CA, McGee H, Hickey A, O'Malley K, Joyce CR: Individual quality of life in patients undergoing hip replacement. Lancet 339: 1088–1091, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kagawa-Singer M: Redefining health: Living with cancer. Soc Sci Med 37: 295–304, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robbins RA, Simmons Z, Bremer BA, Walsh SM, Fischer S: Quality of life in ALS is maintained as physical function declines. Neurology 56: 442–444, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lynn J, Goldstein NE: Advance care planning for fatal chronic illness: Avoiding commonplace errors and unwarranted suffering. Ann Intern Med 138: 812–818, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holley JL: Advance care planning in elderly chronic dialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol 35: 565–568, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unruh M, Miskulin D, Yan G, Hays RD, Benz R, Kusek JW, Meyer KB: Racial differences in health-related quality of life among hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 65: 1482–1491, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lopes A, Brag-Gresham J, Satayathum S, McCullough K, Pifer T, Goodkin D, Mapes D, Young E, Wolfe R, Held P, Port F: Health-related quality of life and outcomes among hemodialysis patients of different ethnicities in the United States: The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am J Kidney Dis 41: 605–615, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ortega F, Rebollo P: Health related quality of life (HRQOL) in the elderly on renal replacement therapy. J Nephrol 15: 220–224, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Unruh ML, Newman AB, Larive B, Amanda Dew M, Miskulin DC, Greene T, Beddhu S, Rocco MV, Kusek JW, Meyer KB: The influence of age on changes in health-related quality of life over three years in a cohort undergoing hemodialysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 56: 1608–1617, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lamping DL, Constantinovici N, Roderick P, Normand C, Henderson L, Harris S, Brown E, Gruen R, Victor C: Clinical outcomes, quality of life, and costs in the North Thames Dialysis Study of elderly people on dialysis: A prospective cohort study. Lancet 256: 1543–1550, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grun RP, Constantinovici N, Normand C, Lamping DL, North Thames Dialysis Study Group: Costs of dialysis for elderly people in the UK. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 2122–2127, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Termorshuizen F, Korevaar JC, Dekker FW, van Manen JG, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT: The relative importance of residual renal function compared with peritoneal clearance for patient survival and quality of life: an analysis of the Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis (NECOSAD)-2. Am J Kidney Dis 41: 1293–1302, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Unruh ML, Weisbord SD, Kimmel PL: Health-related quality of life in nephrology research and clinical practice. Semin Dial 18: 82–90, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beusterien KM, Nissenson AR, Port FK, Kelly M, Steinwald B, Ware JE Jr: The effects of recombinant human erythropoietin on functional health and well-being in chronic dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 763–773, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tawney KW, Tawney PJ, Hladik G, Hogan SL, Falk RJ, Weaver C, Moore DT, Lee MY: The life readiness program: A physical rehabilitation program for patients on hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 36: 581–591, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, Fine MJ, Levenson DJ, Peterson RA, Switzer GE: Prevalence, severity, and importance of physical and emotional symptoms in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2487–2494, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sprangers MA, Schwartz CE: Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: A theoretical model. Soc Sci Med 48: 1507–1515, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwartz CE, Sprangers MA: Methodological approaches for assessing response shift in longitudinal health-related quality-of-life research. Soc Sci Med 48: 1531–1548, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wehler M, Geise A, Hadzionerovic D, Aljukic E, Reulbach U, Hahn EG, Strauss R: Health-related quality of life of patients with multiple organ dysfunction: Individual changes and comparison with normative population. Crit Care Med 31: 1094–1101, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]