Abstract

Background and objectives: Mean arterial pressure has been used in clinical trials in nephrology to randomly assign and treat patients, yet the pulsatile component of BP is recognized to influence outcomes in older people. I examined the unique contributions of systolic (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) on the risk for ESRD and death in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: A single-center, prospective cohort study was conducted of 218 veterans with CKD (22% black, 4% women, mean age 68 yr, clinic BP 154.1 ± 25.1/85.2 ± 13.9 mmHg, 48% with diabetes).

Results: During follow-up of up to 7 yr, 63 patients had ESRD and 102 patients died. Compared with those with controlled SBP (<130 mmHg), patients with moderate control (130 to 149 mmHg) had hazard ratio of 3.87 and those with poor control hazard ratio of 9.09 for ESRD. DBP had no direct ability to predict ESRD. For all-cause mortality, a J-shaped relationship was seen for SBP and an inverse relationship was seen for DBP. Considered jointly in the Cox model, a higher SBP and lower DBP improved the prediction of all-cause mortality compared with either BP component alone. The presence of J curve was especially pronounced in patients with advanced CKD, absence of clinical proteinuria, or age >65 yr.

Conclusions: In older patients with CKD, SBP predicts ESRD and a higher SBP and lower DBP predicts all-cause mortality. Lower BP of <110/70 mmHg is a marker of higher mortality in older individuals with advanced CKD.

Emerging evidence suggests that arterial stiffness is an important risk factor for mortality, especially in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) (1). Increasing arterial stiffness induces a reflected pulse wave that augments the pulse in systole and results in an elevated pulse pressure, the most common clinical manifestation of increased arterial stiffness (2). An elevated systolic BP (SBP) and lower diastolic BP (DBP) reflects arterial aging (3). The mean arterial pressure reflects the steady-state component of BP, whereas the pulsatile component is better reflected by the pulse pressure. Although the concept of mean arterial pressure and pulse pressure is achieving recognition in nephrology clinical practice (4,5), two landmark trials in nephrology randomly assigned patients on the basis of two levels of mean arterial pressure (6,7). The unique contribution of SBP and DBP in predicting hard outcomes in patients with established CKD is unclear.

Whereas some studies find a direct link between SBP and hard outcomes (4,5) others find an inverse relationship between SBP and outcomes (8). Whether consideration of DBP improves the prediction of mortality or ESRD in patients with CKD remains poorly studied. Consideration of both components of BP (systolic and diastolic) together may allow determination of the prognostic importance with respect to each other.

The purpose of this study was to clarify the relationship of SBP and DBP on hard outcomes in patients with CKD. Specifically, I evaluated the hazards of ESRD and death in patients with CKD to address the question of whether incorporation of DBP can improve the assessment of outcomes when treating systolic hypertension. On discovering a higher mortality at lower BP (J curve), I further explored the factors associated with the J curve.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

The cohort was assembled prospectively from the renal and a general medicine clinic at the Indianapolis Veterans Affairs Hospital between October 17, 2000, and May 29, 2002, and has been previously described (9). Consecutive patients were enrolled when they were ≥18 yr of age with an estimated GFR (eGFR) <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 by the abbreviated four-component Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula. When GFR was between 60 and 90 ml/min per 1.73 m2, I required urine albumin/urine creatinine ratio to be >30 mg/g to diagnose CKD (10). Patients were excluded for body mass index >40 kg/m2, acute renal failure, receiving renal replacement therapy, atrial fibrillation, or change in their antihypertensive regimens within 2 wk of study enrollment. The institutional review board of Indiana University and the Research and Development Committee of the Richard L Roudebush Veterans Affairs Medical Center approved this study, and all patients gave their written informed consent.

Exposure Assessment

Standardized clinic BP were obtained by one nurse trained in BP measurement using an oscillometric monitor (Omron 412C; Omron Healthcare, Bannockburn, IL) (11). For each patient, the average BP from each arm obtained in triplicate was calculated. The higher of the two averages was defined as the patient's BP. Clinic BP recordings were averaged over two visits using the arm that recorded the higher BP. BP measurements were not collected after these initial measurements.

Outcome Assessment

ESRD and all-cause mortality were analyzed as individual outcomes because previous research suggested that these competing outcomes may share different pathophysiologic pathways (12). Each patient's electronic medical record was manually examined for notation of dialysis. When dialysis was not initiated, then the most recent eGFR measurement was calculated. Certain patients refused dialysis even though they had reached ESRD. When patients were asked to initiate dialysis by the nephrologist and eGFR was <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2, the patient was labeled as having ESRD. When the eGFR measurements were <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and the patient was not seen within 6 mo and the patient was alive, the Renal Network was contacted to ascertain whether the patient had initiated dialysis.

The ascertainment of death was established using the computerized VA electronic medical record system. The last date of visit to any VA facility was used to determine the last date of follow-up. For patients who were not seen at a VA facility in the previous 6 mo, the social security death index was checked for mortality.

Statistical Analysis

The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure recommends the level of control of BP in patients with CKD as <130/80 mmHg. I defined BP between 130/80 and 149/89 mmHg as modest control and BP >150/90 mmHg as poor control analogous to stage 1 and stage 2 hypertension of the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure categories. Follow-up for each study participant was calculated from the date of baseline examination until the date of death, development of ESRD, or the follow-up interview. Cumulative incidence of ESRD or death was calculated by the degree of BP control using the Kaplan-Meier method using the Nelson Aalen estimator. Differences across categories were assessed using the log-rank test.

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to determine the significance and strength of association of factors associated with ESRD and mortal outcomes. Models were adjusted for age; race (black versus nonblack); diabetes; log urine albumin creatinine ratio; eGFR; and a history of cardiac disease, including myocardial infarction, use of nitrates, history of angina, or coronary revascularization (13). Proportional hazards assumption was checked using Schoenfeld residuals and by evaluating the statistical significance of the interaction of the log of time with linear predictor in the Cox model.

To explore further the association of BP with ESRD and death, I determined the hazard ratios (HR) for ESRD and death for each category of SBP and DBP. Analyses of BP as predefined categories were performed with each BP component included in the Cox regression model separately or simultaneously (SBP and DBP). Models when nested were compared using the likelihood ratio test.

Finally, I evaluated the nonlinear relationship of time and BP using restricted cubic splines (14). Specifically, I placed 5 knots at 0.050, 0.275, 0.500, 0.725, and 0.950 quantiles of the x variable (SBP or DBP) and then tested the covariates for linearity. I also interacted these covariates with risk factors such as older age (>65 yr), advanced CKD (stage 4 or 5), clinical proteinuria (>1 g/g creatinine), or a combination of older age or advanced CKD to explore the provenance of J curve that emerged for mortality in these individuals.

Significance was set at for a two-sided P < 0.05. All analyses were performed using Stata 10.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study participants are presented according to degree of SBP control in Table 1. Patients were older men, mostly white, and 95% were treated with antihypertensive medications, averaging three medications per patient. Increasing level of poor SBP control was associated with higher DBP and pulse and mean arterial pressure. Poor control was associated with the cause of CKD; those with poor control more often had diabetes as the cause of their kidney disease. Poor control was also associated with greater proteinuria and greater exposure to antihypertensive drugs as reported previously (15).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population by level of SBP controla

| Clinical Characteristic | Overall | SBP Category (mmHg)

|

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controlled (<130) | Moderate Control (130 to 149) | Poor Control (≥150) | |||

| n | 218 | 38 | 63 | 117 | |

| SBP (mean [SD]) | 152.1 (23.4) | 118 (9.7) | 140.8 (5.7) | 169.3 (15.1) | <0.001 |

| DBP (mean [SD]) | 81.9 (13.4) | 69.6 (9.8) | 77.7 (11.1) | 88.1 (12.0) | <0.001 |

| Pulse pressure (mean [SD]) | 70.2 (19.7) | 48.3 (9.9) | 63.0 (11.2) | 81.2 (18.0) | <0.001 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mean [SD]) | 105.3 (14.7) | 85.8 (8.6) | 98.8 (8.1) | 115.1 (10.0) | <0.001 |

| Age (yr; mean [SD]) | 68.4 (11.0) | 65.7 (12.0) | 67.9 (10.4) | 69.5 (10.9) | 0.170 |

| Men (n [%]) | 209 (96) | 34 (89) | 60 (95) | 115 (98) | 0.060 |

| Race (n [%]) | 0.140 | ||||

| white | 169 (78) | 35 (92) | 44 (70) | 90 (77) | |

| black | 47 (22) | 3 (8) | 18 (29) | 26 (22) | |

| other | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| Weight (kg) | 93.1 (21.3) | 94.4 (27.2) | 97.1 (22.5) | 90.5 (18.0) | 0.120 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2; mean [SD]) | 30.4 (6.2) | 30.2 (7.1) | 31.1 (6.7) | 30.1 (5.6) | >0.200 |

| Smoking (n [%]) | >0.200 | ||||

| current | 43 (20) | 8 (22) | 22 (59) | 7 (19) | |

| former | 137 (63) | 22 (59) | 43 (68) | 72 (62) | |

| never | 37 (17) | 7 (19) | 11 (17) | 19 (16) | |

| Diabetes (n [%]) | 105 (48) | 13 (34) | 25 (40) | 67 (57) | 0.010 |

| Coronary artery disease (n [%]) | 93 (43) | 17 (45) | 27 (43) | 49 (42) | >0.200 |

| Cerebrovascular disease (n [%]) | 35 (16) | 4 (11) | 7 (11) | 24 (21) | 0.160 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (n [%]) | 49 (22) | 13 (34) | 11 (17) | 25 (21) | 0.140 |

| Cause of CKD (n [%]) | <0.010 | ||||

| diabetes | 69 (32) | 6 (16) | 16 (25) | 47 (40) | |

| hypertension | 75 (34) | 13 (34) | 22 (35) | 40 (34) | |

| glomerulonephritis | 16 (7) | 6 (16) | 4 (6) | 6 (5) | |

| obstruction | 12 (5) | 3 (8) | 7 (11) | 2 (2) | |

| other | 36 (17) | 6 (16) | 10 (16) | 20 (17) | |

| unknown | 10 (5) | 4 (11) | 4 (6) | 2 (2) | |

| Not receiving medications (n [%]) | 10 (5) | 5 (13) | 1 (2) | 4 (3) | |

| Average no. of antihypertensive drugs | 2.9 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.4) | 3.0 (1.4) | 3.1 (1.4) | 0.020 |

| ACEI (n [%]) | 116 (53) | 21 (55) | 36 (57) | 59 (50) | >0.200 |

| ARB (n [%]) | 42 (19) | 4 (11) | 8 (13) | 30 (26) | 0.040 |

| ACEI or ARB (n [%]) | 148 (68) | 24 (63) | 40 (63) | 84 (72) | >0.200 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl; mean [SD]) | 3.8 (0.4) | 3.7 (0.3) | 3.8 (0.4) | 3.7 (0.4) | >0.200 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl; mean [SD]) | 12.9 (1.9) | 13.5 (1.8) | 12.9 (1.8) | 12.7 (1.9) | 0.080 |

| Urine protein/creatinine (g/g; median [IQR]) | 0.32 (0.09 to 1.63) | 0.12 (0.08 to 0.35) | 0.11 (0.07 to 0.56) | 0.77 (0.20 to 2.37) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2; mean [SD]) | 38.0 (18.4) | 40.7 (21.0) | 40.4 (18.0) | 35.9 (17.6) | 0.180 |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; CKD, chronic kidney disease; DBP, diastolic BP; eGFR, estimated GFR; IQR, interquartile range; SBP, systolic BP.

During a cumulative follow-up of 1009 yr, 102 patients died (crude mortality rate 101.1/1000 patient-years). Cumulative incidence of mortality during 7 yr was 68.7% (95% confidence interval [CI] 55.5 to 84.9). During a cumulative follow-up of 879 yr, 63 patients had ESRD (crude ESRD rate 71.6/1000 person-years), yielding a cumulative incidence rate of 44.2% (95% CI 34 to 57.6%) during 7 yr.

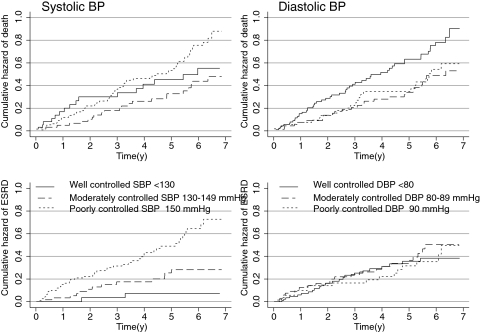

Table 2 shows the number of events, crude mortality rate, and cumulative hazard rates by the level of BP control. The cumulative incidence of mortality at 7 yr of follow-up was 55.3% in the controlled group, compared with 86% in poorly controlled group (P = 0.06 log-rank test; Figure 1). When patients were divided on the basis of DBP control, the cumulative mortality risk was poorest at 86.4% in the controlled group, compared with 59.3% in poorly controlled group (P = 0.09 log-rank test; Figure 1). Thus, the SBP and DBP measurements seemed to convey different prognostic signals for all-cause mortality, although BP control category as a single component was not statistically robust in predicting outcomes.

Table 2.

Event and cumulative incidence rates for individual end points of ESRD or mortality in patients with CKDa

| Parameter | Exposed (n) | Events (n [%]) | Follow-up (person-years) | Crude Event Rate (/1000 person-years) | Cumulative Incidence Rate (%) | HR | 95% CI | P (Model) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| End point of ESRD | ||||||||

| SBP (mmHg) | ||||||||

| <130 | 38 | 2 (5) | 167.6 | 11.9 | 7.20 | 1.00 | <0.001 | |

| 130 to 149 | 63 | 13 (21) | 283.6 | 45.8 | 27.70 | 3.87 | 0.87 to 17.20 | |

| ≥150 | 117 | 48 (41) | 428.2 | 112.1 | 71.40 | 9.09 | 2.21 to 37.50 | |

| DBP (mmHg) | ||||||||

| <80 | 70 | 24 (34) | 363.9 | 66.0 | 37.10 | 1.00 | >0.200 | |

| 80 to 89 | 46 | 23 (50) | 383.1 | 60.0 | 50.60 | 1.29 | 0.72 to 2.30 | |

| ≥90 | 39 | 16 (41) | 232.4 | 68.8 | 49.70 | 1.09 | 0.58 to 2.07 | |

| End point of all-cause mortality | ||||||||

| SBP (mmHg) | ||||||||

| <130 | 38 | 16 (42) | 169.5 | 94.4 | 55.30 | 1.00 | 0.050 | |

| 130 to 149 | 63 | 22 (35) | 319.8 | 68.8 | 46.90 | 0.72 | 0.38 to 1.38 | |

| ≥150 | 117 | 64 (55) | 519.6 | 123.2 | 86.00 | 1.29 | 0.74 to 2.23 | |

| DBP (mmHg) | ||||||||

| <80 | 70 | 52 (74) | 402.1 | 129.3 | 86.40 | 1.00 | 0.090 | |

| 80 to 89 | 46 | 27 (59) | 344.1 | 78.5 | 52.30 | 0.62 | 0.39 to 0.99 | |

| ≥90 | 39 | 23 (59) | 262.7 | 87.6 | 59.30 | 0.69 | 0.42 to 1.13 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Figure 1.

Cumulative hazard of death and ESRD in patients with three different levels of systolic (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) control. Lower baseline SBP was associated with a higher mortality compared with moderately controlled BP. Mortality was highest for the lowest DBP. Higher SBP was associated with greater risk for ESRD, but this was not the case for DBP.

The cumulative incidence of ESRD at 7 yr of follow-up was 7.2% in the controlled group, 27.7% in the moderately controlled group, and 71.4% in poorly controlled group (P < 0.001, log rank test; Figure 1). When patients were divided by DBP control, the cumulative incidence of ESRD was similar between groups. Table 3 shows the HR and their 95% CI for the SBP and DBP in models of ESRD and all-cause mortality when each of these components is considered singly. The joint model reflects one in which the effects of SBP and DBP are considered together. It is evident that when SBP and DBP were entered in the same model to predict all-cause mortality, the model fit improved compared with the single covariate model; however, in case of ESRD outcome, most information for ESRD outcome was contained in the SBP component, and further refinement in prediction was not achieved when DBP was considered simultaneously.

Table 3.

HR for ESRD or death associated with the component of BP

| Parameter | Single-Component Model

|

Joint-Component Model

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP

|

DBP

|

SBP

|

DBP

|

|||||||

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | Model Fit Compared with Single-Component Model | HR | 95% CI | Model Fit Compared with Single-Component Model | |

| ESRD Outcome | χ2 = 3.4, P = 0.1800 | χ2 = 25.3, P < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| BP controlled | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| moderate control | 3.87 | 0.87 to 17.20 | 1.29 | 0.72 to 2.30 | 4.27 | 0.96 to 18.90 | 0.73 | 0.40 to 1.30 | ||

| poor control | 9.09 | 2.21 to 37.50 | 1.09 | 0.58 to 2.07 | 12.05 | 2.83 to 51.30 | 0.53 | 0.27 to 1.05 | ||

| All-cause mortality outcome | χ2 = 12.5, P = 0.0020 | χ2 = 13.7, P = 0.0010 | ||||||||

| BP controlled | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| moderate control | 0.72 | 0.38 to 1.38 | 0.62 | 0.39 to 0.99 | 0.82 | 0.43 to 1.56 | 0.45 | 0.27 to 0.74 | ||

| poor control | 1.29 | 0.74 to 2.23 | 0.69 | 0.42 to 1.13 | 2.04 | 1.12 to 3.72 | 0.45 | 0.26 to 0.77 | ||

Table 4 shows the multivariate adjusted HR of the joint model compared with the single-component model. In the case of ESRD outcome, the addition of DBP did not add to the prediction of outcomes, but in the case of all-cause mortality, there was some evidence of improvement in model fit. The fall in HR from 2.04 to 0.61 for all-cause mortality in the poorly controlled hypertension group was the most intriguing finding. This suggests that certain risk factors may be conferring high mortality but may be associated with low SBP. To explore this further, I analyzed the nonlinear relationships of BP and mortality.

Table 4.

Adjusted HR for ESRD or death: Joint modela

| Outcome | SBP

|

DBP

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | Model Fit Compared with Single-Component Model | HR | 95% CI | Model Fit Compared with Single-Component Model | |

| ESRD (multivariate adjusted) | χ2 = 3.2, P = 0.20 | χ2 = 8.2, P < 0.02 | ||||

| BP controlled | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| moderate control | 3.840 | 0.820 to 17.800 | 0.640 | 0.330 to 1.250 | ||

| poor control | 6.370 | 1.360 to 30.000 | 0.500 | 0.230 to 1.090 | ||

| All-cause mortality (multivariate adjusted) | χ2 = 4.1, P = 0.13 | χ2 = 6.0, P = 0.05 | ||||

| BP controlled | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| moderate control | 0.430 | 0.220 to 0.840 | 0.600 | 0.360 to 0.998 | ||

| poor control | 0.610 | 0.310 to 1.180 | 0.810 | 0.460 to 1.410 | ||

Adjusted for age, eGFR, race, diabetes, coronary artery disease, and log protein/creatinine ratio.

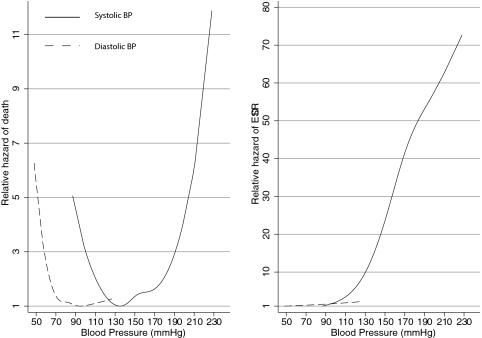

Figure 2 shows the nonlinear relationship of SBP and DBP with ESRD and all-cause mortality. Mortality increased when BP reduced to <110/70 mmHg and also when SBP increased >180 mmHg. A monotonic relationship between baseline SBP and DBP and ESRD was observed.

Figure 2.

A J-shaped relationship was seen between SBP or DBP and all-cause mortality. SBP was a much stronger predictor of ESRD compared with DBP.

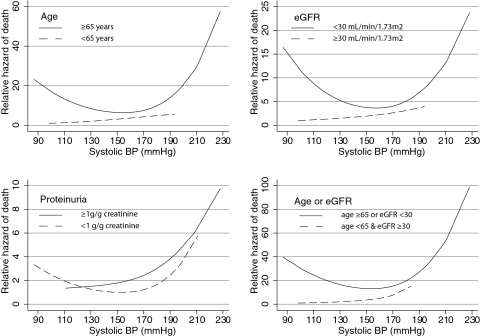

I next analyzed the relationship of certain high-risk characteristics such as older age (>65 yr), lower eGFR (<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2), overt proteinuria (>1 g/g creatinine), and a combination of older age or lower eGFR and their interactions with SBP on the hazard of mortality. The J-shaped relationship was most evident for the group of patients who had low eGFR and exhibited higher mortality with decreasing SBP (Figure 3). Those with proteinuria benefited from aggressive BP lowering, but a J shape was evident for those with proteinuria of <1 g/g creatinine. Older people as well as those older or those with more advanced CKD also showed a more pronounced J curve.

Figure 3.

The underlying risk factors such as age, severity of renal failure, or proteinuria modified the relationship between SBP and mortality. The J-shaped relationship was seen in older individuals but not in the younger patients. It was seen in those with more advanced renal failure. Those with overt proteinuria demonstrated no association of increase in death rates at lower clinic SBP. In contrast to younger patients with less severe renal failure, patients with more severe renal failure or those who were older had the most escalation in death risk at lower SBP.

Discussion

It is now well established that systolic hypertension is associated with an increased rate of progression of kidney disease (16–18). This study confirms that baseline SBP is a stronger predictor than DBP in predicting ESRD. Adding DBP to SBP provided no additional information with respect to ESRD outcomes. These data gathered in older veterans support a patient-level meta-analysis that suggests that SBP be controlled to between 110 and 129 mmHg to reduce the risk for kidney disease progression (19). These results are also similar to that reported by Bakris et al. (4), who studied the relative importance of simultaneous consideration of SBP and DBP on the outcome of ESRD in patients who participated in the Reduction in endpoints in NIDDM with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan (RENAAL) Study. They found that 10-mmHg increases in SBP increased the risk for ESRD 17%, but this relationship was not seen for DBP. A direct and graded relationship was also reported between baseline and achieved BP during follow-up in patients who participated in the Irbesartan Diabetic Nephropathy Trial (IDNT), and baseline SBP (in contrast to DBP) was prognostically informative of renal end point of doubling of serum creatinine or ESRD (5).

By itself, neither SBP nor DBP was sufficient to discriminate the mortal prognosis in patients with CKD; however, when considered together, a higher SBP and lower DBP can better inform the risk for future mortality in older men with CKD. These data are also consistent with previous reports of mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy by Bakris et al. (4). Although they did not report mortality outcomes, the composite outcome of ESRD and death was increased 17% with a 10-mmHg increase in SBP and fell 11% with a 10-mmHg increase in DBP. The latter suggests that DBP can inform the risk for future mortality. The finding that low, not high, DBP in older individuals with CKD increases the likelihood of mortality is also consistent with other reports. For example, in people older than 60 yr increases in SBP but reduction in DBP elevates the risk for future coronary heart disease (20). SBP and pulse pressure confer a greater risk for the occurrence of heart failure compared with diastolic BP (21). Low DBP also has a greater influence on all-cause mortality in community-based studies (22). Similar data have emerged in hemodialysis patients, in whom the joint consideration of SBP and DBP show directionally opposite influences on the likelihood of total mortality (23–25). Whereas the pathophysiologic reason underlying this relationship is obscure, a low DBP may be a marker of poor overall health (26) and increased arterial stiffness (3) and may be associated with compromised coronary circulation. These data extend national guidelines that call for SBP as the major criterion for diagnosis, staging, and therapeutic management of hypertension, particularly in middle-aged and older Americans to the population of patients with CKD (27,28).

Perhaps the most intriguing finding of this study is that different levels of SBP and DBP have disparate effects on mortality and ESRD in patients with CKD. Whereas a lower SBP and DBP is related to better ESRD outcomes, a J-shaped relationship is seen with all-cause mortality. BP of <110 mmHg systolic and <70 mmHg diastolic were associated with increased all-cause mortality. SBP >170 mmHg was associated with greater mortality, but in those with such high SBP, lower DBP (and therefore a wide pulse pressure) was further associated with increased mortality. These finding are concordant to that reported by Pohl et al. (5), who found that SBP <120 mmHg was associated with a mortality rate much higher than that seen with SBP between 131 and 140 mmHg and were comparable to that seen with SBP >180 mmHg among patients who participated in the IDNT study.

This study extends the previous reports of a J curve by discovering potential risk factors that may be associated with worse outcomes. Specifically, those with more advanced age, lower eGFR, or a combination of these factors had worse outcomes. Patients with significant proteinuria seemed to show no J curve. These data begin to explain the observations of Kovesdy et al. (8), who found a reverse association of BP and mortality after multivariate adjustments in veterans with CKD. It is likely that similar mechanisms may have been operative in their study.

This study has several strengths and limitations. Mortality and ESRD were ascertained not just via a computerized database query but also by searching each patient's record for the onset of ESRD. BP was prospectively obtained over two visits by a research nurse, and the average of these BP was used. I used the arm with the higher BP for subsequent measurements because interarm BP differences can influence mortality outcomes (29). Furthermore, information on proteinuria, GFR, and coronary artery disease, important risk factors for mortality and ESRD outcomes, was prospectively collected, and patients had long-term follow up for up to 7 yr after inception of the cohort. There are several limitations of our data. First, this study is limited to predominantly male veterans and may not apply to younger people and women. In younger people with CKD, high DBP is likely to be more damaging (30). Although the sample size was small, a large number of events provided adequate power to perform these analyses. Second, I did not collect follow-up BP, medication, and proteinuria information and thus cannot comment on the time dependence of the outcomes on these risk factors; however, other studies inform that lowering SBP to the 120- to 130-mmHg range is associated with better renal outcomes (4,5).

Broad goals of treatment of patients with CKD are to prolong the time to dialysis, prevent cardiovascular disease, and extend life. BP control is the mainstay of stalling progression of CKD, but its impact on reducing cardiovascular events in patients with CKD has not been observed in randomized trials (6,31,32). Given that BP may have disparate effects on ESRD and mortality outcomes, aggressive lowering of BP, especially in older patients or those with advanced CKD, may be deleterious. In fact, lowering SBP to <110 mmHg has been associated with worsening of progression of CKD (19). ESRD and mortality are often analyzed as a composite outcome in clinical trials, which may miss the opportunity to discover disparate pathways that may mediate these outcomes. Establishing risk factors that accelerate progression of renal disease and distinguishing them from those that increase mortality would be an important research goal so that we may refine recommendations on preparation for ESRD versus more aggressive control of cardiovascular disease on the basis of these risk factors. Finding the optimal BP targets can be determined only in randomized trials, but lowering BP to <110/70 mmHg in older people with CKD should be avoided, especially when they have advanced CKD and absence of clinical proteinuria. Targeting a mean arterial pressure without attention to SBP and DBP components should be abandoned altogether in older individuals.

Disclosures

None.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Safar ME, Blacher J, Pannier B, Guerin AP, Marchais SJ, Guyonvarc'h PM, London GM: Central pulse pressure and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension 39: 735–738, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Rourke MF: Wave travel and reflection in the arterial system. J Hypertens 17[Suppl 5]: S45–S47, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal R: Antihypertensive agents and arterial stiffness: Relevance to reducing cardiovascular risk in the chronic kidney disease patient. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 16: 409–415, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakris GL, Weir MR, Shanifar S, Zhang Z, Douglas J, van Dijk DJ, Brenner BM: Effects of blood pressure level on progression of diabetic nephropathy: Results from the RENAAL study. Arch Intern Med 163: 1555–1565, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pohl MA, Blumenthal S, Cordonnier DJ, De AF, DeFerrari G, Eisner G, Esmatjes E, Gilbert RE, Hunsicker LG, de Faria JB, Mangili R, Moore J Jr, Reisin E, Ritz E, Schernthaner G, Spitalewitz S, Tindall H, Rodby RA, Lewis EJ: Independent and additive impact of blood pressure control and angiotensin II receptor blockade on renal outcomes in the irbesartan diabetic nephropathy trial: Clinical implications and limitations. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 3027–3037, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agodoa LY, Appel L, Bakris GL, Beck G, Bourgoignie J, Briggs JP, Charleston J, Cheek D, Cleveland W, Douglas JG, Douglas M, Dowie D, Faulkner M, Gabriel A, Gassman J, Greene T, Hall Y, Hebert L, Hiremath L, Jamerson K, Johnson CJ, Kopple J, Kusek J, Lash J, Lea J, Lewis JB, Lipkowitz M, Massry S, Middleton J, Miller ER III, Norris K, O'Connor D, Ojo A, Phillips RA, Pogue V, Rahman M, Randall OS, Rostand S, Schulman G, Smith W, Thornley-Brown D, Tisher CC, Toto RD, Wright JT Jr, Xu S: Effect of ramipril vs amlodipine on renal outcomes in hypertensive nephrosclerosis: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 285: 2719–2728, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klahr S, Levey AS, Beck GJ, Caggiula AW, Hunsicker L, Kusek JW, Striker G: The effects of dietary protein restriction and blood-pressure control on the progression of chronic renal disease. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med 330: 877–884, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kovesdy CP, Trivedi BK, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Anderson JE: Association of low blood pressure with increased mortality in patients with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 1257–1262, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen MJ, Khawandi W, Agarwal R: Home blood pressure monitoring in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 45: 994–1001, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manjunath G, Sarnak MJ, Levey AS: Prediction equations to estimate glomerular filtration rate: An update. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 10: 785–792, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN, Jones DW, Kurtz T, Sheps SG, Roccella EJ: Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1—Blood pressure measurement in humans: A statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension 45: 142–161, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agarwal R, Bunaye Z, Bekele DM, Light RP: Competing risk factor analysis of end-stage renal disease and mortality in chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol 28: 569–575, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keane WF, Brenner BM, de Zeeuw D, Grunfeld JP, McGill J, Mitch WE, Ribeiro AB, Shahinfar S, Simpson RL, Snapinn SM, Toto R: The risk of developing end-stage renal disease in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy: The RENAAL study. Kidney Int 63: 1499–1507, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Pollock BG: Regression models in clinical studies: Determining relationships between predictors and response. J Natl Cancer Inst 80: 1198–1202, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agarwal R, Andersen MJ: Correlates of systolic hypertension in patients with chronic kidney disease. Hypertension 46: 514–520, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klag MJ, Whelton PK, Randall BL, Neaton JD, Brancati FL, Ford CE, Shulman NB, Stamler J: Blood pressure and end-stage renal disease in men. N Engl J Med 334: 13–18, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young JH, Klag MJ, Muntner P, Whyte JL, Pahor M, Coresh J: Blood pressure and decline in kidney function: findings from the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 2776–2782, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaeffner ES, Kurth T, Bowman TS, Gelber RP, Gaziano JM: Blood pressure measures and risk of chronic kidney disease in men. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 1246–1251, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jafar TH, Stark PC, Schmid CH, Landa M, Maschio G, de Jong PE, de Zeeuw D, Shahinfar S, Toto R, Levey AS: Progression of chronic kidney disease: The role of blood pressure control, proteinuria, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition: a patient-level meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 139: 244–252, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franklin SS, Larson MG, Khan SA, Wong ND, Leip EP, Kannel WB, Levy D: Does the relation of blood pressure to coronary heart disease risk change with aging? The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 103: 1245–1249, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haider AW, Larson MG, Franklin SS, Levy D: Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and pulse pressure as predictors of risk for congestive heart failure in the Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med 138: 10–16, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kikuya M, Ohkubo T, Asayama K, Metoki H, Obara T, Saito S, Hashimoto J, Totsune K, Hoshi H, Satoh H, Imai Y: Ambulatory blood pressure and 10-year risk of cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality: The Ohasama study. Hypertension 45: 240–245, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tozawa M, Iseki K, Iseki C, Takishita S: Pulse pressure and risk of total mortality and cardiovascular events in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Kidney Int 61: 717–726, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klassen PS, Lowrie EG, Reddan DN, DeLong ER, Coladonato JA, Szczech LA, Lazarus JM, Owen WF Jr: Association between pulse pressure and mortality in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. JAMA 287: 1548–1555, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foley RN, Herzog CA, Collins AJ: Blood pressure and long-term mortality in United States hemodialysis patients: USRDS Waves 3 and 4 Study. Kidney Int 62: 1784–1790, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boutitie F, Gueyffier F, Pocock S, Fagard R, Boissel JP: J-shaped relationship between blood pressure and mortality in hypertensive patients: New insights from a meta-analysis of individual-patient data. Ann Intern Med 136: 438–448, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Izzo JL Jr, Levy D, Black HR: Clinical Advisory Statement: Importance of systolic blood pressure in older Americans. Hypertension 35: 1021–1024, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr, Roccella EJ: The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA 289: 2560–2572, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agarwal R, Bunaye Z, Bekele DM: Prognostic significance of between-arm blood pressure differences. Hypertension 51: 657–662, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis JB, Berl T, Bain RP, Rohde RD, Lewis EJ: Effect of intensive blood pressure control on the course of type 1 diabetic nephropathy. Collaborative Study Group. Am J Kidney Dis 34: 809–817, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berl T, Hunsicker LG, Lewis JB, Pfeffer MA, Porush JG, Rouleau JL, Drury PL, Esmatjes E, Hricik D, Parikh CR, Raz I, Vanhille P, Wiegmann TB, Wolfe BM, Locatelli F, Goldhaber SZ, Lewis EJ: Cardiovascular outcomes in the Irbesartan Diabetic Nephropathy Trial of patients with type 2 diabetes and overt nephropathy. Ann Intern Med 138: 542–549, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Snapinn SM, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S: Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 345: 861–869, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]